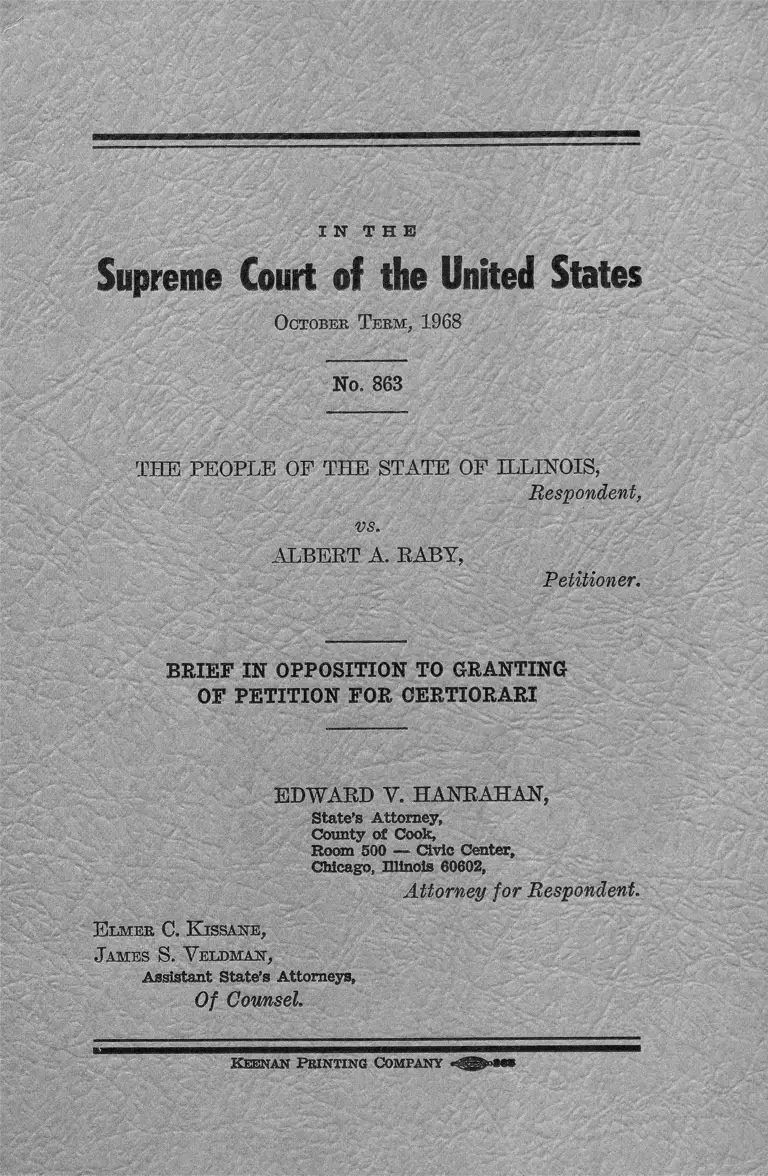

People of Illinois v. Raby Brief in Opposition to Granting of Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. People of Illinois v. Raby Brief in Opposition to Granting of Petition for Certiorari, 1968. 10da0bbc-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1fc53594-92d2-44db-9858-dc00d2a3a786/people-of-illinois-v-raby-brief-in-opposition-to-granting-of-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Supreme Court of the United States

October T eem , 1968

I N T H E

No. 863

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS,

Respondent,

vs.

.ALBERT A. RABY,

Petitioner.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO GRANTING

OF PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

EDWARD V. HANRAHAN,

State’s Attorney,

County of Cook,

Room 500 — Civic Center,

Chicago, Illinois 60602,

Attorney for Respondent.

E im e r C. K issane,

J ames S. V eudman,

Assistant State’s Attorneys,

Of Gownsel.

Keenan P rinting Company

I N D E X

PAGE

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions...................... 1-3

Reasons Why The Writ Should Not Be Granted;

The Statutes In Question Were Properly Interpreted 3-4

Petitioner’s Conduct Not Protected Under Umbrella

of First Amendment R igh ts................................... 4-7

Clarity and Scope of the Illinois S tatutes............ 7-9

Sufficiency of the Complaints................................... 10-12

Amendment To The List Of Prosecution Witnesses 12-13

Instructions To The J u r y .......................................... 14

Conclusion....................................................................... 15

C itation- op A uthorities

Cases

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 (1952)................ 8

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U.S. 296 (1940) ............... 6

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1965) ......................... 5

Feiner v. New York, 340 U.S. 315 (1951) .................... 6

In Re. Bacon, 240 Cal. App. 2d 34 (1966) .................... 9

Kovacs v. Cooper, 336 U.S. 77 (1949)........................... 6

Landry v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 938 (N.D. 111. 1968) .. .9,14

People v. Crayton, 284 N.Y.S. 2d 672 (1967) .............. 9

People v. Rabv, 40 111. 2d 392, 240 N.E. 2d 595 (1968)

3-5, 7-8, 11, 13

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965) ......................... 13

Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U.S. 395 (1953) .......... 5-6

Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147 (1939) ........................ 6

Smith v. United States, 360 U.S. 1 (1959) ................... 10

United States v. Debrow, 346 U.S. 374 (1953) ............. 10

United States v. Jones, 365 P. 2d 675 (2nd Circuit,

1966) ......................... 8

United States v. Kahn, 381 F. 2d 824 (7th Circuit,

1967) , Certiorari Denied, 389 U.S. 1015............... 10

United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) ............. 5

United States v. Woodward, 376 F. 2d 136 (7th Cir

cuit, 1967) ................................................................... 9

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1946) ................ 8

S tatutory P rovisions

Illinois Revised Statutes, 1967, Ch. 38, Sec. 26-l(a)(l) 4,7

Illinois Revised Statutes, 1967, Ch. 38, Sec. 31-1 . . . . 4,8

M iscellaneous

Kazmin, “Residential Picketing And The First Amend

ment, 61 N. W. U. L. Rev. 177, 208 (1966) ......... 6

11 .

I N T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

Octobee T eem , 1968

No. 863

THE PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF ILLINOIS,

Respondent,

vs.

ALBERT A. RABY,

Petitioner.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO GRANTING

OF PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

STATUTES CONSTRUED

111. Rev. Stat. Ch. 38, Sec. 26-1

Sec.

26-1. Elements of the Offense.

26-1. § 26-1. (Elements of the Offense.) (a) A

person commits disorderly conduct when he know

ingly:

(1) Hoes any act in such unreasonable manner as

to alarm or disturb another and to provoke a breach of

the peace; or

2

(2) With intent to annoy another, makes a tele

phone call, whether or not conversation thereby ensues;

or

(3) Transmits in any manner to the fire depart

ment of any city, town, village or fire protection dis

trict a false alarm of fire, knowing at the time of sneh

transmission that there is no reasonable ground for

believing that such fire exists; or

(4) Transmits in any manner to another a false

alarm to the effect that a bomb or other explosive of

any nature is concealed in such place that its ex

plosion would endanger human life, knowing at the

time of such transmission that there is no reasonable

ground for believing that such bomb or explosive is

concealed in such place; or

(5) Transmit in any manner to any peace officer,

public officer or public employee a report to the effect

that an offense has been committed, knowing at the

time of such transmission that there is no reasonable

ground for believing that such an offense has been

committed; or

(6) Enters upon the property of another and for

a lewd or unlawful purpose deliberately looks into a

dwelling on the property through any window or other

opening in it.

(b) Penalty.

A person convicted of a violation of subsection 26-

1(a) (1) or (a) (2) shall be fined not to exceed $500.

A. person convicted of a violation of subsection 26-

1(a) (4), (a) (5) or (a) (6) shall be fined not to

exceed $500 or imprisoned in a penal institution other

than the penitentiary not to exceed 6 months, or both.

A person convicted of a violation of subsection 26-1 (a)

(3) shall be fined not to exceed $500 or imprisoned in

a penal institution other than the penitentiary not to

exceed 6 months, or both, or shall be imprisoned in

the penitentiary not to exceed 18 months. As amended

3

by act approved June 29, 1967. L.1967, p.----- , H. JB.

No. 633.

111. Rev. Stat. Clx. 38, Sec. 31-1

31-1. § 31-1. Resisting or Obstructing a Peace

Officer.]. A person who knowingly resists or obstructs

the performance by one known to the person to be

a peace officer of any authorized act within his official

capacity shall be fined not to exceed $500 or im

prisoned in a penal institution other than the peniten

tiary not to exceed one year, or both.

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD NOT BE

GRANTED.

I .

THE REQUESTED WRIT OF CERTIORARI SHOULD

NOT ISSUE SINCE THE ILLINOIS SUPREME

COURT HAS PROPERLY DETERMINED THAT THE

ILLINOIS DISORDERLY CONDUCT AND RESIST

ING A PEACE OFFICE STATUTES ARE CONSTI

TUTIONALLY APPLICABLE TO THE PETITIONER,

AND SINCE THE CONDUCT INDULGED IN BY HIM

IS NOT SUCH AS TO COME UNDER THE UM

BRELLA OF FIRST AMENDMENT PROTECTION.

The petitioner has requested that this Honorable Court

issue a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of the

State of Illinois to review that Court’s decision in the

case of People of the State of Illinois v. Albert A. Rahy,

40 111. 2d 392, 240 NE 2d 595 (set forth in the Appendix

to the Petition for Certiorari). The only questions raised

by the instant petitioner which even seem to be of true

constitutional scope are those dealing with the applica

tion to him of the Illinois Criminal Code provisions dealing

4

with. Resisting a Peace Officer and Disorderly Conduct.

111. Rev. Stats., ch. 38 §26-l(a)(l), and III. Rev. Stats.,

ch. 38, §31-1. However, a reading of the well reasoned

opinion of Mr. Justice Walter Y. Schaefer, of the Illinois

Supreme Court shows that that Court properly determined

all of the issues presented to it and that there is nothing

here which would warrant the issuance of the Writ of

Certiorari which the petitioner has requested. United

States Supreme Court Rule 19.1 specifically states that the

granting of such a writ is not a matter of right but rather

an exercise of the soundest judicial discretion. It is readily

apparent from an examination of the opinion of the Su

preme Court of Illinois that that Court has not decided

any issue not many times previously determined by this

Honorable Court, and that there is nothing in the opinion

which might in any sense be in possible conflict with the

past pronouncements of either this Court or of any of the

United States District Courts.

Furthermore, it must be noted at the outset that the

type of conduct indulged in by the instant petitioner is

not such as falls under the umbrella of protection offered

by the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the United

States Constitution so that all of his claims of constitu

tional deprivation are completely without foundation.

A.

THE CONDUCT OP THE PETITIONER

The facts in the instant case were not in dispute and

showed that on the evening of June 28, 1965, during the

height of the “rush hour” traffic situation in the City of

Chicago, the petitioner and a number of companions sat

or laid down in the downtown intersection of La Salle

and Randolph Streets (40 111. 2d 392, 394). They com

pletely blocked the passage of traffic through this inter

section and after some 20 minutes the police demanded

they get up and be on their way. The petitioner, among

others, refused to leave, “went limp”, and had to be car

ried from the intersection by members of the Chicago

Police Department (see Appendix to Petition For Cer

tiorari, p.l-a). In its opinion the Illinois Supreme Court

specifically found that this conduct was prescribed by the

Illinois statutes in question and that it was not conduct

protected under the provisions of the First and Fourteenth

Amendments (Appendix to Petition for Certiorari, p.5-a)

In so holding, Mr. Justice Schaefer cited the opinion of this

Honorable Court in Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536, 544

(1965). Therein, while the holding of the Louisiana Su

preme Court was reversed because the statute there in

question was found to be overly broad, this Court also

noted that the protection offered by the First Amend

ment to the United States Constitution did not extend

itself to such modes of expression as blocking the passage

of traffic along the public streets.

The statement of Mr. Justice Schaefer, speaking for the

Court is neither novel nor in any sense conflicting with

previous pronouncements of this Honorable Court. Quite

the contrary. The First Amendment protections cannot be

applied to all modes of expression indiscriminately by the

simple process of labeling all of the petitioner’s conduct

as “free speech” or free expression. United States v.

O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968). As Your Honors pointed

out in Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U.S. 395, (1953), at

p. 405:

“The principles of the First Amendment are not to

be treated as a promise that everyone with opinions

or beliefs to express may gather around him at any

public place and at any time a group for discussion

or instruction. It is a non sequitur to say that First

Amendment rights may not be regulated because they

hold a preferred position in the hierarchy of the Con

stitutional guarantees of the incidents of freedom.

This Court has never so held and indeed has in

dicated the contrary. . .”

And the Court went on to say, at page 408:

“There is no basis for saying that freedom and

order are not compatible. That would be a decision

of desperation. Regulation and suppression are not

the same, either in purpose or result and courts of

justice can tell the difference.”

We submit that “telling the difference” is exactly what

the Supreme Court of Illinois has done in the instant

case. Tour Honors have many times held that one of the

reasons proper for police intervention in breaking up a

group of persons is the clear danger that the result of the

group’s actions will be the interference with the passage

of traffic upon the public thorofares. Feiner v. New York,

340 U.S. 315, 320 (1951); Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310

U.S. 296, 308 (1940). This Court recognizes the strong-

legitimate interest of the authorities in maintaining order

upon the public streets. Kovaes v. Cooper, 336 U.S. 77, 82

(1949); Schneider v. State, 308 U.S. 147, 160 (1939). As

one legal writer has put it:

“. . . The Constitutional status of a grievance does

not give First Amendment protection to every form

utalizied to air it. Sitting down in Times Square or

at the intersection of State and Madison, however

lofty the objectives of the demonstrators may be, can

not be supported by Constitutional privilege.” (Kamin,

Residential Picketing And the First Amendment, 61

N.W. U.L. Rev. 177, 208 (1966)).

7

Therefore, as was found by Mr. Justice Schaefer, and

his collegues, the conduct of the petitioner was not such

as to come within the protection of the First Amendment

to the United States Constitution. We therefore submit

that his claims of Constitutional deprivation are without

meaning and that he shows here no reason for the grant

ing of the writ which he requests.

B.

NEITHER ILLINOIS STATUTE IS OVERLY BROAD

NOR VAGUE.

There is no validity to the claims of the petitioner that

the Illinois Statutory provisions dealing with Disorderly

Conduct and Resisting a Peace Officer are overly broad or

too vague to inform him in advance of whether or not his

contemplated conduct might be prescribed by law. Both

contentions were specifically rejected by the Illinois Su

preme Court in their opinion.

As to the Disorderly Conduct Provision (111. Rev. Stah,

ch. 38, §26-1 (a)), Mr. Justice Schaefer pointed out that the

petitioner’s arguments overlook the clear meaning of the

words used in the provision. He continued (Petition for

Certiorari, pp. 2a-3a, 40 111. 2d 392, 395-396):

. . That conduct must be engaged in “knowingly”

and in “such unreasonable manner” as to provoke a

breach of the peace. The word “knowingly” describes

a conscious and deliberate “quality which negatives ac

cident or mistake. “Unreasonable” is not a term which

is impermissibly vague. As used in the Fourth

Amendment it furnishes the governing standard by

which the legality of police instructions upon privacy

are measured. (Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1, 20 L.Ed.

2d 889.) As used in this statute it removes the pos

sibility that a defendant’s conduct may be measured

by the effect upon those who are inordinately timorous

or belligerent. The well recognized common-law term

“breach of the peace” appears in §6 of Art. I of the

Constitution of the United States.”

As Justice Schaefer also pointed out, words of the statute

must be given their usual and customary meanings and

resort to all of the possible dictionary definitions of a

term is not proper since by so doing one could render

meaningless almost any penal statute. After all, almost all

words vary in meaning as does the context in which they

are used. Such a holding is also in complete conformity

with the past pronouncements of the United States Su

preme Court and other Federal Courts of review. The

words of a statute are to be given their normal and cus

tomary meanings and are not to be viewed by courts of

review from the point of grammarians or lexicographers.

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U.S. 250 (1952). The suf

ficiency of the words of a statute to limit its scope and to

inform the accused of the conduct prohibited must be de

termined in view of the interpretation given the statute

by the courts of the state in which it is enforced. Winters

v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948); United States v. Jones,

365 F. 2d 675 (2d. Cir.-1966).

What has been said above applies with equal force to

the other statute here in question, 111. Rev. Stats., ch. 38,

§31-1, dealing' with resisting a peace officer. As the

opinion of the Illinois Supreme Court points out, this

statute specifically provides for some active resistance of

a person known to be a peace officer and further requires

that that officer must be acting in his official capacity at

the time of the resistance (40 111. 2d 392, 398-399; Petition

for Certiorari, pp. 6a-7a). This certainly is not overly

broad and it certainly does inform the potential actor of

9

what conduct is prohibited by the provision. In fact,

the validity of both the Illinois Disturbing the Peace and

Resisting a Peace Officer statutes have been upheld in the

Federal Courts. United States v. Woodward, 376 F. 2d

136 (7th Cir.-1967); Landry v. Daley, 280 F. Supp. 938

(N.D. 111. 1968). The statutes here in question were speci

fically found to be neither too vague nor too broad in

scope. In fact, in both of these federal decisions, the con

duct which was held to constitute resisting of a peace

officer was precisely that of the instant petitioner, “going-

limp”. The act of “going limp” has been held to constitute

resisting of a police officer in a number of jurisdictions;

Cf. In Re Bacon, 240 Cal. App. 2d 34 (1966); People v.

Crayton, 284 N.Y.S. 2d 672 (Supreme Court of New York,

1967). In short, there is simply no doubt that the con

duct of the petitioner was properly found to be that

covered by the Resisting a Peace Officer statute and that

any person would know that such conduct was prohibited.

Furthermore, there is no question that the deliberate block

ing of a busy intersection during the “rush hour” con

stituted an act of Disturbing the Peace and that it was

not conduct protected by the First Amendment.

Therefore, the People of the State of Illinois submit that

no reason has been shown by the petitioner for the granting

of the Petition for Certiorari.

10

I I .

THE REMAINING POINTS RAISED BY THE PETI

TIONER ARE MERELY PROCEDURAL AND IN NO

WAY SUPPLY GROUNDS FOR THE ISSUANCE OF

THE REQUESTED PETITION.

The remainder of the petition deals with a number of

procedural points, none of which provide Your Honors

with any reason for the issuance of a Petition for Cer

tiorari to the Illinois Supreme Court.

A.

THE COMPLAINTS RETURNED AGAINST

PETITIONER.

The complaints against the petitioner were phrased in

the language of the appropriate statutes and informed the

accused of the offenses charged and of the conduct for

which he was being held responsible. This was sufficient

to make both complaints proper. (Petition for Certiorari,

pp. 7a-9-a, 40 111. 2d 392, 399-401). The test of an in

dictment is not whether it could have been made more

definite and certain but whether it sets forth the elements

of the offense, enables the accused to know what he will

be required to defend against, and is specific enough to

prevent the accused from once again being placed in

jeopardy upon the same charges. United States v. Hebrew,

346 U.S. 374, 376 (1963); United States v. Kahn, 381 F.

2d 824 (7th Cir.-1967); Cert. Denied 389 U.S. 1015. In

dictments are read for their clear meaning and convic

tions will not be reversed because of minor deficiencies.

Smith v. United States, 360 U.S. 1, 9 (1959). A reading

of the indictments here in question clearly shows that they

were sufficient to properly state the offense charged.

11

Furthermore, the petitioner is hardly in a position to

complain about the amendment of the complaint which

charged him with Resisting a Peace Officer (Petition for

Certiorari, pp. 13-14). This contention is completely dis

posed of by the opinion of Mr. Justice Schaefer in the in

stant case, which shows that the amendment of this com

plaint was in accordance with the petitioner’s own wishes.

The Illinois Supreme Court states (Petition for Certiorari,

pp. 8a-9a, 40 III 2d 392, 400-401):

The complaint for resisting arrest originally in

cluded an additional allegation: that, when placed un

der arrest, the defendant “refused to voluntarily ac

company [the] arresting officer, and had to be physi

cally carried away and while being carried, did kick,

squirm, struggle in an effort to escape the custody of

said officer.” This allegation Avas stricken after the

defendant complained that its inclusion left him in

doubt as to whether he Avas being charged under

section 7—7 or section 31—1 of the Criminal Code.

The complaint specified only the latter section. Never

theless, to prevent possible confusion, the State asked

and was granted permission to strike the second al

legation. The defendant xioav argues that it -was re-

versible error to alloAV this amendment. The argu

ment is Avithout merit. Section III—5 of the Code of

Criminal Procedure provides: “An indictment, infor

mation or complaint which charges the commission of

an offense # * * may be amended on motion by the

State’s Attorney or defendant at any time because of

formal defects, including: * * * (d) The presence of

any unnecessary allegation. 111. Rev. Stat., .1967, eh.

38,' fl I I-fi.

It is quite plain that the amendment to the complaint now-

complained of occurred at the instance of the petitioner

himself. It is equally clear that no harm or prejudice

could possibly have resulted to him for the action of the

trial judge in allowing the amendment, and that the amend

12

ment was proper under the provisions of Illinois criminal

procedure. We do not believe that more need be said

upon this question than was said by Mr. Justice Schaefer

in the above quotation.

B.

THE AMENDED LIST OF WITNESSES.

The petitioner also contends that his right to fair trial

was abridged by the allowance of the People’s request

to file an amended list of witnesses at the opening of the

trial (Petition for Certiorari, pp. 14-15). When the

amended list of witnesses was submitted, the petitioner

objected but he did not ask for a continuance when the

trial judge accepted the offer of the amended list by the

People (Petition for Certiorari, pp. 9a-10-a). Now the

petitioner makes a vague assertion that he was somehow

prejudiced by the fact that he did not have the names

of these witnesses earlier. Yet he has in no way indicated

the manner of this prejudice to himself. This fact was

noted by Mr. Justice Schaefer in the Illinois Supreme

Court’s opinion in the instant case. There it was noted

that the purpose of requiring a list of witnesses is to pre

vent surprise and to guard against false testimony, and

that allowing the amendment of such a list is a matter

within the sound discretion of the trial judge (40 111. 2d

392, 401-402; Petition for Certiorari, p. 10a). The Court

then concluded:

“In this case the defendant has at no time sug

gested that if he had been afforded an opportunity to

prepare for the testimony of the unlisted witnesses he

would have been able to produce rebuttal witnesses

or to otherwise impeach the credibility of the unlisted

witnesses. (See, People v. O’Hara, 332 111. 436, 442,

466.) Moreover, he himself testified to substantially

the same facts. He has thus failed to make any

showing that it was prejudicial to permit the un

listed witnesses to testify, or that their testimony in

any way surprised him.”

Under these circumstances no reversible error or viola

tion of the constitutional rights of the petitioner could

have resulted.

The petitioner attempts to analogize his position con

cerning the unlisted witnesses to that of the defendant in

Pointer v. Texas, 380 U.S. 400 (1965), but the analogy is

a false one. In Pointer v. Texas, the defendants were con

victed of robbery largely on the basis of testimony

elicited from a witness during the course of a preliminary

hearing at which the defendants were not represented by

counsel. This damaging witness was not available to the

prosecution at the time of the trial. His testimony was

received by the trial court by way of a transcript of the

preliminary hearing, thus completely depriving the de

fendants of the right to confrontation and cross-examina

tion. This is far different from the instant factual situa

tion, as are the holdings in the other cases cited by the

petitioner in his argument concerning the witness list.

Once again, there is nothing to be found here but an

allegation that the petitioner was in some way deprived

of his constitutional rights and that in some way the de

cision of the Supreme Court of Illinois is erroneous. But

there is no substantiation of any of these allegations and

nothing here which would suggest that he is entitled to

the issuance of the Writ of Certiorari.

14

C.

THE INSTRUCTION TO THE JURY.

Finally, the petitioner alleges that the jury was not

properly instructed. However, it will he noted that he

himself is forced to admit that the jury was given in

structions as to both offenses which set out the elements

of the crimes in the language of the respective applicable

statutes (Petition for Certiorari, pp. 15-16). He seems

once again to contend that since the statutes are uncon-

situtional, these instructions did not properly inform the

jury. The propriety of the statutory provisions has already

been discussed here at some length. Suffice it to say

here that the statutes were proper and that the instruc

tions given in their language informed the jury of the

law applicable to the petitioner’s conduct.

The petitioner complains of the instruction which told

the jury:

“The court instructs the jury, as a matter of law,

that resisting a peace officer in the performance of his

duty may be passive as well as active. To interfere

and obstruct does not require active resistance and

force.”

As has been earlier pointed out, passive resistance such

as “going limp”—as the petitioner did here—has been

held to be resisting a peace officer. See, Landry v. Daley,

280 F. Supp. 938 (N.D. 111., (1968)). Such an instruction

was a perfectly proper statement of the law and as such

the jury was entitled to hear it. The giving of this or the

other instructions concerning the nature of the two charged

offenses was anything but error.

15

CONCLUSION

For the above and foregoing reasons, the People of the

State of Illinois most respectfully submit to this Honorable

Court that the request of Albert A. Raby for the issuance

of a Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Illinois

in the instant case be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

E dward V. I Iaxuaiian.

S ta te ’s A tto rney ,

C ounty of Cook,

R oom 500 — Civic C enter,

Chicago, Illinois 60602,

Attorney for Respondent.

E lmer C. K issake,

J ames S. V eldman,

A ssis ta n t S ta te ’s A tto rneys,

Of Counsel.

-

&

-

;

f

i:I

"

„ ' - ’