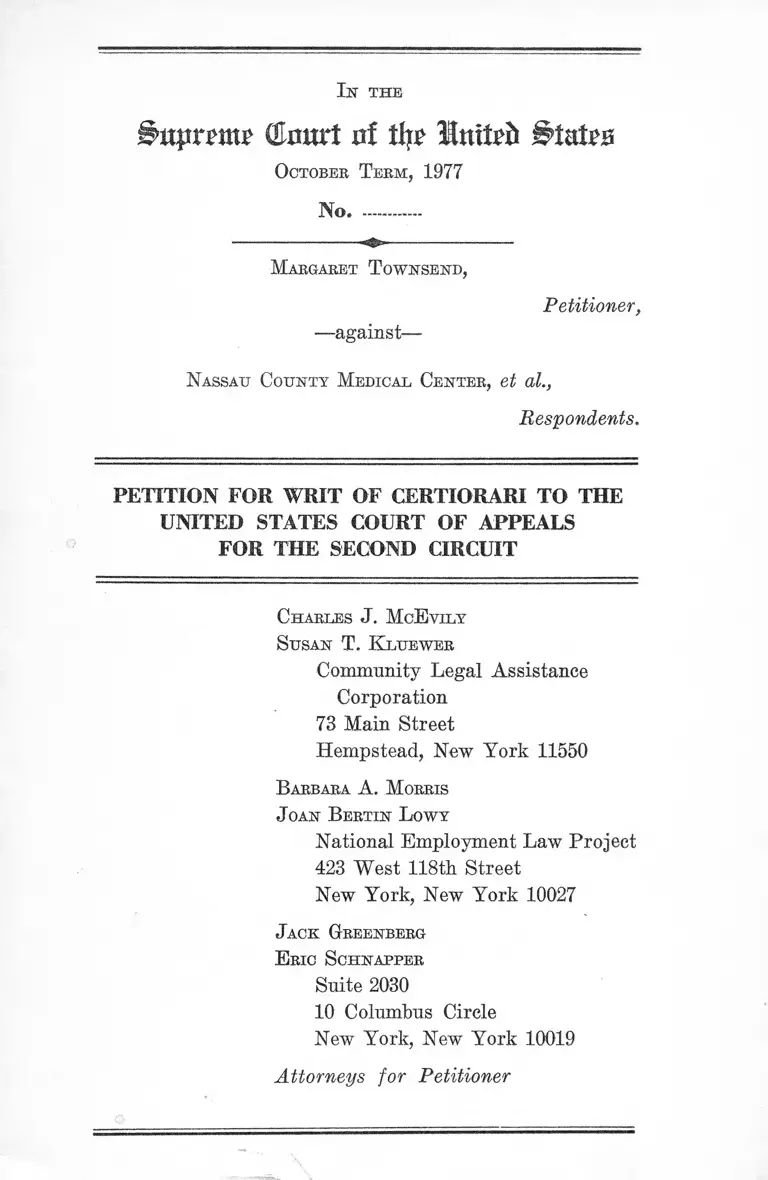

Townsend v. Nassau County Medical Center Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Townsend v. Nassau County Medical Center Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1977. a68b985f-c69a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/1fe1f810-d4d8-443b-ac6e-374796460d6c/townsend-v-nassau-county-medical-center-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Ik the

Qkuri n! % Intlpfr States

October T erm, 1977

No...... .

Margaret T ownsend,

Petitioner,

—against—

Nassau County Medical Center, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Charles J. McE vily

Susan T. K luewer

Community Legal Assistance

Corporation

73 Main Street

Hempstead, New York 11550

Barbara A. Morris

J oan Bertin Lowy

National Employment Law Project

423 West 118tli Street

New York, New York 10027

Jack Greenberg

E ric Schnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Table of Cases ...................................................................... ii

Opinions B elow .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................... ............................................. 2

Questions Presented ............................. -........................... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ........................................ 3

Statement of the Case ........................................... 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ ..............................-....... 8

Conclusion ............................... - ............................................

A p p e n d ix —

Opinion of the District Court, December S, 1975 .. la

Order of the Court of Appeals, June 21,1976 ........ 19a

Judgment of the District Court, September 27,

1976 ........................................................................... 21a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals, June 30, 1977 .... 23a

Order of the Court of Appeals, August 24,1977 .... 35a

11

PAGE

Table op Cases

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ..6,11,

12.13

Boyd v. Ozark Airlines, Inc., 15 EPD ft 7863 (8th Cir.

1977) ................................................................................. 9

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1954) .....5,13

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 97 S. Ct. 2720 (June 30,1977) ..2,4, 8,

9,10,11,12,13,14

Gaston County v. U.8., 395 U.S. 289 (1968) ............... 5

Green v. Missouri Pacific Railroad Co., 523 F. 2d 1290

(8th Cir. 1975) ................................................................... 9

Gregory v. Litton Systems, 472 F. 2d 631 (9th Cir.

1972) ................................... 9

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .....6,9,11,

12.13

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber, 491 F. 2d 1364,

1371 (5th Cir. 1974) ........................................................ 9

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F. 2d 906,

918 (5th Cir. 1973) ........................................................ 9

In the

(tart of tfjr Imtrfi States

October T erm, 1977

No........... .

Margaret T ownsend,

Petitioner,

—against—

Nassau County Medical Center, et al.,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

The petitioner, Margaret Townsend, respectfully prays

that a writ of certiorari issue to review the judgment and

opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Second Circuit entered in this proceeding on June 30, 1977.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the district court, which is not reported,

is set out in the appendix, pp. la-18a. The order of the

court of appeals vacating the district court judgment and

remanding for reconsideration, which is not reported, is

set out in the appendix, pp. 19a-20a. The judgment of the

district court confirming its original judgment, which is

not reported, is set out in the appendix, pp. 21a-22a. The

2

opinion of the court of appeals, which is reported at 558

F.2d 117, is set out in the appendix, pp. 23a-34a. The or

der of the court of appeals denying rehearing, which is not

yet reported, is set out in the appendix, pp. 35a-36a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Second

Circuit was entered on June 30, 1977. A timely petition

for rehearing was denied on August 24, 1977 and this peti

tion for Certiorari was filed within ninety days of that

date. Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1254 (1).

Questions Presented

1. Was the June 30, 1977, decision of the Court of Ap

peals, holding that evidence that a job requirement ex

cluded 94% of the black adult population was irrelevant to

Title VII, clearly erroneous and in conflict with the deci

sion of this Court on June 27, 1977, upholding such evi

dence as sufficient to demonstrate discriminatory effect

under Title VII, Dothard v. Rawlinson, 97 S. Ct. 2720 (June

27, 1977)?

2. Did the respondents act arbitrarily and capriciously,

in violation of due process of law, or contrary to equal

protection of the law wThen they dismissed petitioner from

a job which she had concededly performed with complete

competence for 8 years solely because she could not meet

a newly implemented requirement that any person holding

her job must have a Bachelor of Science degree!

3

Statutory Provision Involved

Section 703 of Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e (2) as amended, provides:

“ (a) It shall be an unlawful employment practice for

an employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate

against any individual with respect to his

compensation, terms, conditions, or privileges

of employment, because of such individual's

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees

or applicants for employment in any way

which would deprive or tend to deprive any

individual of employment opportunities or

otherwise adversely affect his status as an

employee, because of such individual’s race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

Statement of the Case

Petitioner is a 44-year old black woman who was fired by

respondents1 after eight years of exemplary job perform

ance because she did not possess a college degree, an

eligibility requirement imposed some years after she began

1 The respondents are Nassau County Medical Center; Doctor

Donald H. Eisenberg, Superintendent; Nassau County Civil Serv

ice Commission; Gabrial Kahn, Chairman; Edward Witanowski,

Edward A. Simmons, Adele Leonard, Executive Director of Nas

sau County Civil Service Commission. Petitioner’s claim against

the state defendants was dismissed before trial.

4

her employment. Petitioner commenced this suit alleging

that respondents had discriminated against her on the basis

of race in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 2000e, et s&q., as amended. Petitioner claimed, and the

United States District Court found, that the requirement

of formal college education had an unjustifiable racially

disproportionate impact forbidden by Title VII. The Court

of Appeals for the Second Circuit reversed the district

court judgment on the grounds that petitioner failed to

make out a prima facie case, notwithstanding unchallenged

statistical proof that three times fewer blacks than whites

in the area population could satisfy the challenged require

ment. Such a holding is so directly in conflict with this

Court’s recent decision in Dothard v. Rawlinson, 97 S. Ct.

2720 (June 30, 1977), decided just three days before the

court of appeals rendered its decision here, that summary

reversal, or remand for reconsideration in light of Dothard,

is warranted.2

Petitioner has been employed in the blood bank of Nassau

County Medical Center since 1965. Her competence to per

form the duties of Medical Technologist I is unquestioned:

she is rated among the top employees in the blood bank

and from 1967 served as assistant to the Supervisor. In

1970, she was appointed Acting Supervisor of the entire

laboratory and served in that capacity for six months.

Thereafter, petitioner trained and then served as assistant

to the newly-appointed permanent supervisor until 1973,

Petitioner promptly brought Dothard to the attention of the

■ >.. art of appeals in a timely petition for rehearing, but the peti-

■: u was denied without comment.

5

when she was fired for w’ant of formal education.3 Before

she was fired, petitioner trained new employees in the

blood bank to perform the duties of a Medical Technologist

I. These new employees, all of whom are white, now earn

more than petitioner because they have had the required

formal education.

Petitioner was officially given the title and pay of a Medi

cal Technologist I in 1967 as a result of a Civil Service

reclassification. As a result of the same reclassification,

respondents imposed the requirement that all candidates

for permanent appointment as Medical Technologists I

possess a college degree or equivalent academic certifica

tion,4 and that they take and pass the Civil Service Exami

nation.5

3 The record reveals that petitioner received an inferior educa

tion in segregated Florida and South Carolina Schools. See Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1954) ; Gaston Co, v. U.S.,

395 U.S. 289 (1969). “ Her high school was apparently so poor

that it was abandoned when integration was required . . . ” p. 2a.

4 Certification by the American Society for Clinical Pathologists

(ASCP), is an alternative prerequisite. To obtain such certifica

tion, however, one must have a specified amount of laboratory

training and have a college degree. Petitioner, although not a

member of ASCP, trained students who would later get ASCP

certification and permanent Medical Technologist I positions. Peti

tioner is certified by the International Association of Laboratory

Technologists as a Registered Medical Technologist (RMT).

5 An issue not presented in this case is respondents’ use of a

written examination, in addition to the college degree requirement,

for qualification as a permanent Medical Technologist I. _ The

examination tested not only knowledge of blood banking techniques

relevant to the job at issue, but skills used in ten other labora

tories involving very different methods and lab equipment: hema

tology, histology, virology, chemistry, serology, bacteriology, immu-

nohemotology, electrophoresis, microbiology, and parisitology. This

Court has already held “a test may be used in jobs other than

those for which it has been professionally validated only if there

are ‘no significant differences’ between the studied and unstudied

6

An examination for permanent classification was given

in April, 1973, but respondents denied petitioner permis

sion to take the examination because she did not fulfill the

formal academic requirements. In December, 1973, peti

tioner was fired as a result of the promulgation of a Medi

cal Technologist I eligibles list based on the April, 1973

examination. Three months later she was rehired, and

given the same duties, but at a lower-paying Laboratory

Technician II classification. Before she was fired, peti

tioner was the only black Medical Technologist I in the

blood bank, which has approximately fifteen workers; at

the time of trial, there were no black Medical Technol

ogists I.8

Guided by the approach in Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971), the district court, using local and state

census statistics introduced by petitioner, found that the

college requirement operated to exclude blacks from em

ployment at a rate three times greater than whites, and

held that petitioner had made out a prima facie case under

Title VII. The district court also concluded respondents

produced no evidence that the challenged degree require

jobs.” Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 432 (1975).

Pursuant to a “grandfather” provision, petitioner was able to take

the examination only onee. She did not pass, but was continued

for two more years. If she had had a college degree, she would

be permitted to take the examination repeatedly without being

either fired or demoted. Thus, it is the degree which bars peti

tioner’s path. Inasmuch as petitioner was not fired because she

has not passed the examination, its validity, while not conceded,

is not yet ripe for determination.

0 The only other black in the blood bank is Frank Appelwaithe,

a male with not one but two college degrees. Mr. Appelwaithe

was hired as permanent supervisor in 1970 to fill the vacancy left

by George Davis, a white who had no college degree. Mr. Appel

waithe is a Medical Technologist III.

7

ment was related in any way to petitioner’s ability to per

form the job.7

The district court found that in denying petitioner per

mission to take the 1973 examination because she was not

“properly” educated,8 and thereafter demoting her to a

lower paying position, respondents violated Title V I I ; the

court ordered petitioner reinstated as a provisional Medi

cal Technologist I, enjoined respondents from disqualify

ing petitioner from taking future civil service examina

tions because she does not have a college degree, and

awarded back pay and attorneys fees.

On June 30, 1977,9 the court of appeals reversed the

judgment with directions to dismiss the complaint on the

7 Nor can respondents now argue that the degree requirement

is job related. In a memorandum to respondent Medical Center

dated August 8, 1977, respondent Civil Service Commission ob-

stensibly abolished the college degree requirement in recognition

of the “criticism that the Bachelor’s Degree in Science did not

provide adequate nor [sicj appropriate laboratory training.” In

reality, however, since AS CP certification is still required and is

currently granted only to individuals with college degrees, the

degree requirement remains in effect. See note 4, supra.

8 On-the-job training rather than formal education is what is

essential to successful work in the blood bank. One witness, who

had a college degree and ASCP certification, testified that she

learned everything she knew about blood banking from petitioner.

Although the Medical Technologist I title is used throughout the

Medical Center, the evidence established that once a person is

trained in a particular laboratory, he is not thereafter transferred.

Job specifications for Medical Technologist I do not require ex

perience, while those for Medical Technologist II require two years

experience in the field of specialization, indicating that vertical

rather than horizontal movement within the Medical Center is

what is contemplated.

9 Upon respondents’ initial appeal, the Second Circuit, on June

21, 1976, vacated the district court judgment for the plaintiff and

remanded for reconsideration in light of Washington v. Davis, 426

U.S. 229 (1976). On remand, the district court confirmed its

original judgment, and respondents again appealed.

8

ground that petitioner failed to establish a prima facie

case. The court of appeals held that evidence demonstrat

ing that the college degree requirement excluded almost

three times as many blacks as whites in the adult popula

tion, was not sufficient to establish adverse racial impact.

Petitioner filed a motion for rehearing in light of Dothard

v. Rawlinson, 97 S. Ct. 2720 (June 27, 1977). The petition

was denied without opinion.

Reasons for Granting the Writ

The court of appeals held that unrebutted census sta

tistics showing that a job requirement disqualifies a dis

proportionate number of minorities in the adult popula

tion are insufficient to establish a prima facie case of dis

criminatory impact under Title VII. The Second Circuit

ruled, at the urging of respondents,10 that plaintiff had

failed to make out a prima facie case because “ statistical

evidence concerning only the general population is [not]

sufficient to demonstrate that a job prerequisite ‘operates

to exclude’ minorities.” p. 29a. This is precisely the argu

ment rejected by this Court in Dothard v. Rawlinson, 97

S. Ct. 2720 (June 30, 1977).

The appellants argue that a showing of dispropor

tionate impact on women based on generalized national

statistics should not suffice to establish a prima facie

case. . . . There is no requirement, however, that a

statistical showing of disproportionate impact must

10 See, e.g., Brief for Nassau County Defendants-Appellants, No.

76-7522, pp. 6-7.

9

always be based on analysis of the characteristics of

actual applicants.

97 S. Ct. at 2727. In Dothard, this Court upheld the use

of census data to prove the discriminatory impact of the

defendant’s height-weight job requirement. 97 S. Ct, at

2727, n. 12. In Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 430,

n. 6 (1971), this Court expressly relied on census data

showing the disproportionate impact of Duke Power’s high

school degree requirement on adults in North Carolina.

Because Dothard was decided only three days before the

panel decision in the instant case, however, the court of

appeals could not as a practical matter have been aware

of it when its decision was written. Under these circum

stances, it would clearly be appropriate to summarily re

verse the decision below or to vacate and remand for recon

sideration in light of Dothard.

The decision of the Second Circuit holding irrelevant

evidence that a job requirement precludes a dispropor

tionate segment of the black adult population is squarely

in conflict with the decisions of the three other circuits.

See United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F. 2d 906,

918 (5th Cir. 1973); Johnson v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber,

491 F. 2d 1364, 1371 (5th Cir. 1974); Green v. Missouri

Pacific Railroad Co., 523 F. 2d 1290, 1293-95, rehearing

den. 523 F. 2d 1299 (8th Cir. 1975); Boyd v. Ozark Air

lines, Inc., 15 EPD 7863, pp. 6283, 6285, n. 1 (8th Cir.

1977); Gregory v. Litton Systems, 472 F. 2d 631 (9th Cir.

1972), aff’g 316 F. Supp. 401, 403 (C.D. Cal. 1970). In

addition, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion, conforming to this Court’s decision in Griggs, has

consistently held that the disparate impact of a job re

10

quirement can be measured by its effect on the general

population.11 Thus either the Commission will have to fol

low a different substantive rule in the Second Circuit than

it applies in the rest of the country or its probable cause

findings in cases arising in New York, Vermont and Con

necticut will often be in direct conflict with federal law in

that circuit.

The Second Circuit appears to have ruled that a job re

quirement has a discriminatory effect only if “ virtually

no blacks were in fact able to satisfy the challenged job

qualification and obtain employment with the defendant.”

p. 29a, n. 6. If the Second Circuit’s standard considers

only evidence of the qualifying rate among actual job ap

plicants, it is precisely the standard rejected by Dothard.

It is also impossible to understand how this standard could

result in judgment for defendant in this case, since no black

applicant for the position petitioner held, Medical Technol

ogist I at the blood bank, has ever satisfied the degree re

11 E.E.O.C. Opinions Nos. 77-9, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide

If 6564; 75-199, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide If 6555; 75-115, 2

CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6533; 75-103, 2 CCH Emp. Prac

tices Guide ff 6529; 75-047, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6441,

p. 4176; 74-92, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide 6424; 74-90 2 CCH

Emp. Practices Guide 6423; 74-89, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide

If 6418; 74-83, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide 6414; 74-53, 2 CCH

Emp. Practices Guide ff 6410; 74-41, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide

ff 6408, p. 4093; 74-34, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6407, p.

4089; 73-0499, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6402, p. 4079,

74-25, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6400, pp. 4071-72; 74-27

2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6396; 74-08, 2 CCH Emp. Prac

tices Guide ff 6390; 74-02, 2 CCH Emp. Practices Guide ff 6386

p. 4078; 72-0947, CCH E.E.O.C. Decisions (1973) ff 6357; 72-1497

CCH E.E.O.C. Decisions (1973) ff 6352; 72-1460, CCH E.E.O C

Decisions (1973) ff 6341; 72-1395, CCH E.E.O.C. Decisions (1973)

ff6339, p. 4617, n. 2; 7200427 CCH E.E.O.C. Decisions (1973),

ff 6312, 72-0284, CCH E.E.O.C. Decisions (1973) ff 6304; 71-2682

CCH E.E.O.C. Decisions (1973) ff 6288.

11

quirement, and no black held that position at time of trial,12

If this suggested standard means that plaintiff must prove

that “ virtually no” blacks in the area population could meet

the requirement, it finds no support in Griggs, Dothard, or

Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). The

proportion of blacks (5.9% )13 able to meet the medical

center’s job requirement was substantially lower than the

proportion of women able to meet the height-weight re

quirement in Dothard (41%) or the proportion of blacks

able to meet the high school degree requirement in Griggs

(12% ).14 Title VII is concerned, not with the size of the

minority qualifying rate, but with the disparity between

the proportion of minorities and non-minorities able to

qualify. In this case 16.9% of the whites, but only 5.9%

of the blacks, could meet the degree requirement ;15 16 the white

rate was 2.9 times as high as the black rate. In Griggs,

the white and black rates were 34% and 12%, a ratio of

only 2.8. See 401 U.S. at 430, n. 6. In Dothard, 99% of the

men but only 59% of the women could meet the height-

weight requirement, a ratio of 1.7. Thus the disparity in

the proportion of minorities able to meet the job require

ment in this case is even greater than the disparity in

Griggs or Dothard.

This case is of particular importance because it reflects

the reluctance of the Second Circuit to apply to white collar

jobs in New York the construction of Title VII established

by this Court in cases arising in Alabama18 and North

12 Joint Appendix, pp. 277-278A.

13 Joint Appendix, p. 368A.

14 See Dothard v. Rawlinson, 97 S. Ct. 2720, 2727, n. 12.

15 Joint Appendix, p. 368A.

16 Dothard v. Rawlinson, 97 S. Ct. 2720 (June 30, 1977).

12

Carolina.17 That reluctance seems to arise in part from a

misplaced reverence for higher education.18 The court of

appeals was unduly concerned at the prospect of requiring

employers to justify a college degree requirement, p. 30a,

despite the fact that such a requirement precludes hiring

94.1% of all adult blacks, and even though Griggs usually

requires such a justification for a high school degree re

quirement which precludes hiring only 57.5% of all adult

blacks.19 The opinion below also reflects an inappropriate

deference to Title VII defenses involving “ advanced scien

tific method,” “ the fields of scientific knowledge,” and “ tech

nology” pp. 30a-31a; but federal judges are as capable of

evaluating the job-relatedness in these fields as the job

relatedness of the requirements for the operation of coal-

fired electric power plants,20 or sophisticated multi-million

dollar paper processing machinery,21 or of a maximum-

security prison,22 and Title VII recognizes no exemption for

such positions. Certiorari should be granted to make clear

that Title VII requires the elimination for all jobs in all

parts of the country, not merely blue collar jobs in regions

17 Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975); Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

18 As this Court has noted, “History is filled with examples of

men and women who rendered highly effective performance with

out conventional badges of accomplishments in terms of certificates,

diplomas or degrees. Diplomas and tests are useful servants, but

Congress has mandated the common sense proposition that they

are not to become masters of reality.” Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. at 433.

19 Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1976, p. 123.

20 Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. at 426-7.

21 Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. at 427.

22 Dothard v. Bawlinson, 97 S. Ct. at 2730.

13

with a history of deliberate discrimination, “ of artificial,

arbitrary and unnecessary barriers to employment when

the barriers operate invidiously to discriminate on the basis

of racial or other impermissible classification.” Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. at 431.

The particular facts of this case present circumstances

of compelling injustice. In Griggs, Albermarle, and Dot-

hard, the employer at least asserted a claim, ultimately

rejected by the courts, that the plaintiff’s inability to meet

the disputed job requirement proved that he or she "was

incapable of performing the job. In this case, petitioner

has in fact been doing the job for 12 years; the court of

appeals noted that she had done “ a satisfactory job,” p. 33a,

and respondents candidly conceded “ [tjhere is no doubt that

appellee performs her work in the blood bank laboratory

in a competent manner. She is highly regarded by the

supervisor of the blood bank . . . ” 23 Petitioner reached

her position as a Medical Technologist I only after over

coming the special disadvantage of a segregated and in

ferior public school education prior to Brown v. Board of

Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1954). To dismiss petitioner un

der these circumstances was as manifestly violative of the

Fourteenth Amendment as dismissing her because she had

brown eyes or was born under the wrong sign of the zodiac.

28 Brief for Nassau County Defendants-Appellants, No. 76-7522,

p. 3.

14

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, a Writ of Certiorari should issue

to review the judgment and opinion of the Second Circuit.

The decision of the Second Circuit should be summarily

reversed; in the alternative, the judgment of the Second

Circuit should be vacated and the case remanded for re

consideration in light of Dothard v. Rawlinson.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles J. McE vily

Susan T. K luewer

Community Legal Assistance

Corporation

73 Main Street

Hempstead, New York 11550

Barbara A. Morris

J oan Bertin L owy

National Employment Law Project

423 West 118th Street

New York, New York 10027

Jack Greenberg

E ric Schnapper

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioner

On the Petition:

Jerry Casel,

Leie R ubinstein,

Legal Interns

A P P E N D I X

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

73 C 294

Margaret Townsend,

Plaintiff,

-against-

Nassau County Medical Center,

Dr. Donald H. Eisenberg, Superintendent,

et al,

Defendants.

MEMORANDUM AND ORDER

WEINSTEIN, D.J.

Plaintiff, a black female, has been

employed in the blood bank of the Nassau

County Medical Center, satisfactorily

doing the work of a Medical Technologist

I, since 1965. She brings this suit for

reinstatement in that civil service classi

fication. The defendant Nassau County

Civil Service Commission has demoted her

to a lower paying classification because

she lacks a college degree or equivalent

academic prerequisites, an eligibility

requirement imposed some years after she

began her employment. Her claim is that

the qualification has an unjustifiable

2a

racially discriminatory impact invalid

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seg.

Plaintiff's case is typical of that

of many blacks. She attended school in a

segregated Florida system. Her high school

was apparently so poor that it was aban

doned when integration was required and

its records are not even available. The

movement of many educationally deprived

blacks from the South to this district

created enormous and expensive burdens

for our municipalities. Where, as in

this case, a product of that discrimina

tory educational system has overcome her

disadvantage by work experience, Title

VII requires her actual job skills to be

recognized.

Facts

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

On June 22, 1965, plaintiff was

provisionally appointed to the position of

Laboratory Technician at the Nassau County

Medical Center. On January 6, 1967 she

was provisionally appointed to the position

of Senior Laboratory Technician.

Nassau County reclassified all its

civil service positions effective July 7,

1967 pursuant to a job survey conducted by

the firm of Cresap, McCormack and Paget.

As a result, based on the work she had been

doing, plaintiff was provisionally placed

in a new, competitive position, Medical

Technologist. She held this position until

December, 1973.

During that period plaintiff also

satisfactorily served in several adminis

trative capacities. She was the assistant

to supervisor George Davis, responsible for

3a

the laboratory when Mr. Davis was not there.

She also was responsible for teaching

students blood-banking techniques, since

she was one of the few people who had this

expertise. Some of her former students

are presently employed by Nassau County

doing the same work she does, but receiv

ing much higher salaries because they have

a college degree and have taken and passed

the necessary civil service examinations.

When Mr. Davis left the Medical

Center, plaintiff was appointed Acting

Supervisor. In addition to her technical

duties, she was responsible for all the

administrative functions of the supervisor,

e.g., payroll, supplies, work schedules,

and meetings. After approximately one

year, a permanent supervisor was appointed.

Plaintiff became his assistant.

In December, 1971, plaintiff was

permitted to take the examination required

for permanent classification as a Medical

Technologist I. Although she did not pass

that examination, she was continued provi

sionally in the position of Medical Tech

nologist I because the eligible list pro

mulgated as a result of the 1971 examina

tion did not contain a sufficient number

of names to fill all vacancies.

A second examination for Medical

Technologist I was held in April, 1973.

The plaintiff's application to take this

examination was rejected by the Nassau

County Civil Service Commission because she

did not have the formal educational quali

fications. Plaintiff was discharged in

December of 1973 as a result of the promul

gation of a Medical Technologist I eligible

list based upon the 1973 examination.

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

4a

Three months later she was rehired by the

blood bank, again given the duties of a

Medical Technologist I, but given the low

er paying classification of Laboratory

Technician II.

Although plaintiff's formal educa

tion was limited, her qualifications for

her work in the blood bank have never been

questioned. She began her training in

November 1962 at the Hollywood Memorial

Hospital in Florida where she studied for

one year. She has now had more than ten

years experience in blood banking at the

Nassau County Medical Center. The testi

mony was clear that her activities covered

the entire range of blood bank technology

including typing of patients and donors,

cross matching of patients, preparation of

blood, covering in the donor room, taking

blood, freezing blood, and all related

clerical duties. She has routinely decided

whether donors could safely give blood,

and she has performed microscopic compari

sons of blood samples. As already noted,

for a period of five months, she served as

Acting Supervisor for the entire blood

bank, and she has trained many of the

people who now work above her. Linda Schwaid,

a permanent Medical Technologist I, for

example, testified that plaintiff taught her

everything she now knows about bloodbanking.

Frank Appelwaithe, the present Supervisor,

testified that he would rate the plaintiff

among the top members of the department.

It is clear that there is no meaning

ful specialization of labor within the blood

bank. The witnesses agreed that the press

of the work requires each member to be

familiar with and to perform all functions.

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

5a

Thus, except for assuming added teaching

and supervising duties, the plaintiff is

presently doing as a Laboratory Technician

II exactly what she had done and would do

as a Medical Technologist I.

There is no evidence of bad faith

in the defendants' reclassification of

civil service jobs. The testimony of

Albert Fontana, one of the personnel

specialists involved in the reclassifica

tion survey at the Medical Center, estab

lished that a systematic effort was made

to correlate job title with job content.

It is apparent, however, that, notwith

standing the defendants' good intentions,

an outstanding black employee has been

frozen out of a position for which she has

demonstrated eminent qualifications.

Law

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

The statutory basis for plaintiff's

attack on job qualifications is Section

703 of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 providing:

" (a) It shall be an

unlawful employment

practice for an

employer —

(1) to fail or refuse

to hire or to dis

charge any individual,

or otherwise to dis

criminate against any

individual with respect

to his compensation,

terms, conditions, or

6a

privileges of employ

ment, because of such

individual's race,

color, religion, sex,

or national origin?

or

(2) to limit, segregate,

or classify his employ

ees or applicants for

employment in any way

which would deprive or

tend to deprive any

individual of employ

ment opportunities or

otherwise adversely

affect his status as

an employee, because

of such individual's

race, color, religion,

sex, or national origin."

42 U.S.C. § 2000-e.

Interpreting this statute in Griggs

v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 91 S . Ct.

849 T1971), the Supreme Court held that

requirements which operate to disqualify

blacks in disproportionate numbers violate

the Act unless they can be shown to be

related to successful job performance.

Considering the validity of a high school

diploma and general aptitude tests as job

qualifications, the Court wrote:

"Congress has now...

required that the posture

and condition of the job

seekers be taken into

account....The Act pro

scribes not only overt

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

7a

discrimination but also

practices that are fair

in form but discrimina

tory- in operation. The

touchstone is business

necessity. If an employ

ment practice which oper

ates to exclude Negroes

cannot be shown to be re

lated to job performance,

the practice is prohibited."

401 U.S. at 431, 91 S.Ct. at 853.

The Court rejected the view that

an employer's intent is conclusive in

determining whether a prima facie case of

job discrimination has been established:

"...good intent or absence

of discriminatory inten .

does not redeem employment

procedures or testing

mechanisms that operate

as 'built-in headwinds'

for minority groups and

are unrelated to measuring

job capability.... Congress

directed the thrust of the

Act to the consequences of

employment practices, not

simply the motivation. More

than that, Congress has

placed on the employer the

burden of showing that any

given requirement must have

a manifest relationship to

the employment in question."

401 U.S. at 432, 91 S.Ct. 854 (Emphasis

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

8a

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

in original.).

Under Griggs the plaintiff carries

the initial burden of showing that a job

qualification has a racially dispropor

tionate impact. Once this prima facie

case is made out, the burden shifts to the

employer to prove "a manifest relation

ship to the employment in question." In

Albermarle v. Moody,___U.S.___,____, 95 S.

Ct. 2362, 2375 (1975), the Court strength

ened the position of the complaining party

by ruling that he or she will prevail on

a demonstration that alternative, non-

discriminatory means exist which would

accurately test the qualifications of

employees. See, The Supreme Court, 1974

Term 89 Harv. L. Rev. 47, 228-229, n. 27

(1975). Cf. Boston Chapter NAACP, Inc, v.

Beecher, 504 F. 2d 1017, 1019 (1st Cir.

1974);Vulcan Society v. Civil Service

Commission, 490 F. 2d 387, 392 (2d Cir.

1973) .

A. Prima Facie Discrimination

In support of her prima facie case,

plaintiff offered data compiled by the

Bureau of the Census for 1970. This statis

tical evidence demonstrates the extent to

which a college degree requirement dis

criminates against blacks in New York State

and Nassau County. In New York State 12.7%

whites as compared to 4.2% blacks (males

and females) age 25 years and older have

completed 4 years of college or more. In

Nassau County, 34.5% whites as compared to

12.4% blacks, age 25 years and older,

have a college degree. These statistics

are broken down to reveal sex differences

9a

as well as racial distinctions. The total

population of white males in Nassau County-

age 25 years and older is 370,219. 84,728

white males have four years of college or

more. By contrast only 986 of a total

population of 13,032 black males in Nassau

County have achieved that level in educa

tion. The total population of white fe

males in Nassau County age 25 years and

older is 423,529. 50,036 white females

have four or more years of college. But

only 916 of 19,025 black females have

achieved an equal educational status.

The group with the lowest percentage of

members holding a college degree in Nassau

County is black females; only 4.7% of them

have college degrees.

Statistical evidence of educational

disparity in an appropriate geographical

area is sufficient to establish the dis

proportionate racial impact of a degree

requirement for Title VII purposes. In

Griggs, North Carolina census statistics

alone were relied upon by the Court for

the proposition that a high school diploma

requirement was racially discriminatory.

401 U.S. 424, 431, fn. 6, 91 S. Ct. 849,

853. Statistics on the completion of

high school in the South and the Atlanta

area were relied upon in United States v.

Georgia Power Company, 474 F.2d 906, 918

(5th Cir. 1973) as sufficient evidence of

discriminatory impact. See also, Johnson

v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. Synthetic

Rubber Plant, 491 F. 2d 1361, 1371 (5th

Cir. 1974) (census data on educational

achievement of blacks and whites in Texas

and Houston area).

In the present case, state and

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

10a

county statistics demonstrate an approxi

mately three times higher proportion of

white as compared to black females who

have attended four or more years of col

lege. These statistics establish a prima

facie case that a degree requirement has

a disproportionate impact on blacks.

Comparable evidence as to the racial

impact of the Medical Technologist I exam

ination has not been presented. Because

plaintiff was not dismissed for failure to

pass that examination, it is not now before

the court. Nothing said in this memoran

dum should be construed as touching on the

validity of the examination under Title

VII or any other theory since no evidence

was adduced on this issue.

B * Failure to Show Job-Related

Justification

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

The Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission has approved three methods of

validation to establish the requisite rela

tionship between a qualification and job

performance. EEOC Guidelines, 29 C.F.R.

1607. The Supreme Court in Albermarle,

supra, stated that these guidelines are

entitled to great deference.

"The EEOC has issued 'Guide

lines' for employers seeking

to determine, through pro

fessional validation studies,

whether their employment

tests are job related. 29

CFR Part 1607 (1974). These

Guidelines draw upon and make

reference to professional

11a

standards of test valida

tion established by the

American Psychological

Association. The EEOC

Guidelines are not administra

tive 'regulations' promul

gated pursuant to formal

procedures established by the

Congress. But, as this Court

has heretofore noted, they

do constitute '[t]he admin

istrative interpretation of

the Act by the enforcing

agency', and consequently

they are 'entitled to great

deference.' Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., supra, 401 U.S.,

at 433-434, 91 S. Ct., at 854.

See also Espinoza v. Fara

Mfg. Co., 414 U.S. 86, 94,

94 S.Ct. 334, 339, 33 L.Ed.

2d 287. The message of these

Guidelines is the same as

that of the Griggs case --

that discriminatory tests are

impermissible unless shown,

by professionally acceptable

methods, to be 'predictive

of or significantly correlated

with important elements of

work behavior which comprise

or are relevant to the job

or jobs for which candidates

are being evaluated.'

29 CFR § 1607.4 (c) ."

U .S. at___, 95 S.Ct. at 2378 (footnotes

omitted).

Section 1607.2 of the Guidelines

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

12a

provides that an educational requirement

is to be treated as a test for purposes

of determining its validity. Section

1607.5(a) discusses criterion, content,

and construct validation, the three tech

niques which have been recognized by the

EEOC:

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

" (a) For the purpose of

satisfying the requirements of

this; part, empirical evidence

must be based on studies em

ploying generally accepted

procedures for determining

criterion related validity

such as those described in

'Standards for Education

and Psychological Tests and

Manuals' published by American

Psychological Association....

Evidence of content or con

struct validity as defined

in that publication, may also

be appropriate where cri

terion validity is not feasible.

However, evidence for content

or construct validity should

be accompanied by sufficient

information from job analysis

to demonstrate the relevance

of the content (in the case

of job knowledge or proficiency

tests) or the construct (in

the case of trait measures).

Evidence of content validity

alone may be acceptable for

well developed tests that

consist of suitable samples of

the essential knowledge,

13a

skills or behaviors

composing the job in

question- The types of

knowledge, skills or be

havior contemplated here

do not include those which

can be acquired in the

brief orientation to the

job."

Criterion related validation -- the

preferred method — would require a show

ing that those who possess a degree per

form better in the blood bank in terms of

identifiable criteria, than those who do

not. See Vulcan Society v . Civil Service

Commission, 360 F. Supp. 1265, 1273 (S.D.

N.Y.), affirmed in part and remanded with

respect to issues not decided on the merits,

490 F. 2d 387 (2d Cir. 1973). No credible

evidence has been submitted to support

this proposition in this case. Mrs.

Townsend, without a degree, is considered

by her supervisor and others to be one of

the outstanding members of the blood bank

staff.

The second method, content validation,

would entail proof that the aptitudes,

skills, and training necessary to obtain

a degree are equivalent to the skills and

training required for successful perfor

mance in the blood bank. See Vulcan Society

v. Civil Service Commission, 360 F. Supp

1265 at 1274. Construct validation would

necessitate proof that the requirements for

a degree accurately test for the general

mental and psychological traits which are

needed in the blood bank. See Vulcan

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

14a

Society v. Civil Service Commission, 490

F. 2d 287 at 395.' “

The evidence submitted in this case

does not support the proposition that an

acceptable college program relates to the

practical demands of the blood bank. As

noted, Linda Schwaid, a Medical Technolo

gist I, testified that she obtained all

her training from the plaintiff. More

over, under the Guidelines, content and

construct validation may be used only upon

a showing that criterion validation is

not feasible. 29 C.F.R. § 1607.5(a) (1974)

see also, The Supreme Court, 1974 Term 89

Harv. L. Rev. 47, 233 (1975). No such

showing has been made here.

Defendants did not produce any

credible testimonial or documentary evi

dence to demonstrate the validity of

either the college degree or certification

requirements for the position of Medical

Technologist I pursuant to any of the

accepted methods of validation. Witness

Fontana indicated that no consideration

was given to validating the degree quali

fication during the preparation of the

Cresap survey. According to the testimony,

the development of class specifications

for each job at the Medical Center was

based on responses to questionnaires dis

tributed to employees and supervisors.

The criteria relied on by the supervisors

in making their recommendations is not

known. See Albermarle Paper Company v.

Moody, U.S.___,___ , 95 S.Ct. 2362, 2379

(1975) (employer's validation study for

aptitude tests fatally undermined by reli

ance on supervisorial rankings based on

vague standards). The only other evidence

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

15a

introduced to justify the inclusion of the

college degree in the Medical Technologist

I specifications showed that New York City

requires a degree for a similar position

and two federal bulletins recommend college

education for medical technologists. This

evidence is not sufficient to establish

the validity of the degree requirement for

the position of Medical Technologist I at

the Nassau County Medical Center for this

case in light of plaintiff's proven quali

fications .

The court does not rule on the val

idity of the degree requirement except in

the special circumstances of the case be

fore it. Mr. Appelwaithe the supervisor

did suggest that a college degree might

be useful. In addition, Ms. Schwaid testi

fied that her undergraduate education was

helpful in enabling her to read the litera

ture in the field. Although no direct evi

dence was presented on this point, a degree

or its equivalent might guarantee that new

applicants possess the skills and learning

needed for successful training in the blood

bank. This question would have to be

explored in any future litigation. But,

in any event, under Title VII an inherently

discriminatory safeguard cannot be applied

woodenly to deny job status to a current

employee who has achieved all applicable

learning and skills through practical

experience.

This reasoning is understood by the

District of Columbia Circuit's decision in

Berger v. Board of Psychologist Examiners,

___F .2d___,No. 74-1047, 44 L.W. 2235 (D.C.

Cir. Oct. 28, 1975), partially striking

down a federal statute prescribing minimum

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

16a

educational requirements for all psycho

logists practicing in the District of

Columbia. The Court held that the Fifth

Amendment Due Process Clause guarantees

current practitioners an alternative means

of demonstrating his or her professional

qualifications as against a conclusive

statutory presumption of incompetence. The

Court's language reflects an appreciation

of the value of practical experience. It

wrote:

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

"Possession of a graduate

degree in psychology does not

signify the absorption of

a corpus of knowledge as

does a medical, engineering,

or law degree; rather it is

simply a convenient line

for legislatures to draw,

on the brave assumption

that whatever is taught in

the varied graduate curricula

of university psychology

departments must make one a

competent psychologist, or at

least competent enough to be

allowed to take a licensing

examination. While it may

not be irrational to assume

that this academic background

should in the future be a

requisite to the practice of

psychology, it is of question

able rationality to insist that

current practitioners, who

may have studied and practiced

at a time when graduate courses

in psychology were even less

17a

meaningful, are conclu

sively incapable of meeting

today's new standards

because they did not take

those courses."

Slip Op. at 226.

The Court carefully distinguished

the rights of current practitioners from

those of future applicants.

"Here the irrebuttable

presumption of professional

incompetence absent a

graduate degree is not

invalid with respect to

future psychologists, but

only with respect to current

practitioners who have no

meaningful grandfather

rights ....The inequity of

the statute is that it fails

to account for those compe

tent psychologists who

embarked upon their profes

sion when no degree was re

quired and who thus are

denied a fair opportunity

to come within the statute's

licensing requirements at

this point."

Slip Op. at 228.

If the right of a current, qualified

practitioner to maintain his or her employ

ment cannot be extinguished by statute,

it follows, a fortiori, that such a result

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

18a

may not be accomplished by regulations

which conflict with statutory policies

against racial discrimination.

Conclusion

Opinion of District Court dated December 8, 1975

Plaintiff must be reclassified as

a provisional Medical Technologist I,

retroactive to December 31, 1973, the date

of her dismissal. Pursuant to 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(k), plaintiff is entitled to

back pay in the amount she would have

earned as a Medical Technologist I less

what she actually earned during this

period. In addition, plaintiff is entitled

to take any future Civil Service examina

tions for permanent classification as a

Medical Technologist I. Plaintiff is

also entitled to attorney's fees. 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(k); Albemarle Paper Company v.

Moody, U.S. , , 95 S. Ct. 23~62, 2370

(1975) .

Unless the parties stipulate with

respect to back pay and fees, counsel for

plaintiff shall submit an affidavit on

the issue within ten days. Within twenty

days defendants may either answer by

affidavit or demand a hearing. Within

thirty days, the parties shall submit a

joint order or individual orders consistent

with the court's determination. Agreement

on the form of an order shall not constitute

acquiescence in its validity or waiver of

the right to appeal.

So ORDERED.

Dated: Brooklyn, New York

December 8, 1975.

U.S.D.J.

19a

Order of Court of Appeals dated June 21, 1976

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE

SECOND CIRCUIT

At a stated Term of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit,

held at the United States Courthouse in

the City of New York, on the 21st day of

June one thousand nine hundred and seventy-

six

Present:

HONORABLE HENRY J. FRIENDLY

HONORABLE WILFRED FEINBERG

HONORABLE ELLSWORTH A. VAN

GRAAFEILAND

Circuit Judges,

MARGARET TOWNSEND,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

-against-

NASSAU COUNTY MEDICAL CENTER, et al,

Defendants-Appellants.

No. 76-7003

20a

Appeal from the United States

District Court for the Eastern District

of New York

This cause came on to be heard on

the transcript of record from the United

States District Court for the Eastern

District of New York, and was argued by

counsel.

ON CONSIDERATION WHEREOF, it is

now hereby ordered, adjudged, and decreed

that the judgment of said District Court

be and it hereby is vacated and the case

is remanded for reconsideration in the

light of Washington v. Davis, 44 U.S.L.W.

4789 (U.S. June 7, 1976), particularly

Part III thereof.

Order of Court of Appeals dated June 21, 1976

/s/_________________

HENRY J. FRIENDLY

/s/_________________

WILFRED FEINBERG

/s/____________ ________________

ELLSWORTH A. VAN GRAAFEILAND

U . S . C . J J .

21a

Judgment of District Court dated September 27, 1976

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

75 C 294

MARGARET TOWNSEND,

Plaintiff,

-against-

NASSAU COUNTY MEDICAL CENTER,

DR. DONALD H. EISENBERG, Superintendent,

et al,

Defendant.

JUDGMENT

This matter having been remanded by

the Court of Appeals for the Second Cir

cuit by Order dated the 21st day of June,

1976 for reconsideration, and the matter

having been set down for oral argument

before this Court on the 24th day of Sep

tember, 1976, the plaintiff having been

represented by McEVILY, GRADESS & KLUEWER,

by SUSAN KLUEWER and DONNA CLEAR, Legal

Intern, Community Legal Assistance Corpora

tion, and the defendants having been repre

sented by JAMES M. CATTERSON, JR., County

Attorney of Nassau County by JAMES N.

22a

Judgment of District Court dated September 27, 1976

GALLAGHER, Deputy County Attorney, it is

hereby

ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND DECREED that

the original judgment in favor of plain

tiff dated the 26th day of February, 1976

and heretofor entered on the 27th day of

February, 1976 is in all respects con

firmed for the reasons stated orally at

the hearing. (JBW)

Dated: Brooklyn, New York

September 27, 1976

/a/ JACK B. WEINSTEIN

United States District

Court Judge

23a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 20, 1977

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the Second Circuit

No. 827— September Term, 1976.

(Argued April 1, 1977 Decided June 30, 1977.)

Docket No. 76-7522

Margaret T ownsend,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

—against—

Nassau County Medical Center; Doctor D onald H. E is-

enberg, Superintendent, Nassau County Civil Service

Commission ; Gabriel K ohn, Chairman ; E dward S.

W itanowski, E dward A. Simmons, A dele Leonard, E x

ecutive Director of Nassau County Civil Service Com

mission; New Y ork State Department of Civil Ser

vice; E sra H. P osten, President of the New Y ork State

Civil Service Commission and head of the New York

State Civil Service Department,

Defendants-Appellants.

B e f o r e :

L umbard, Mansfield and Gurfein,

Circuit Judges.

Appeal from a judgment and order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of New York (Wein

stein, J.) that defendants had violated Title Y II of the

24a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 30, 1977

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq., and

ordering that plaintiff employee he reinstated with back

pay.

Reversed.

M a t t h e w A. T ed o n e , Deputy County Attorney,

Mineola, N.Y. (Natale C. Tedone, Senior

Deputy County Attorney, William S. Nor-

den, Deputy County Attorney, and William

Gitelman, County Attorney of Nassau

County, Mineola, N.Y., of counsel), for De-

fendants-Appellants.

S u san K lajewer, Community Legal Assistance

Corp., Hempstead, N.Y. (McEvily & Klue

wer, Hempstead, N.Y., of counsel), for

Plaintiff-Appellee.

Gtu rfein , Circuit Judge:

This individual Title VII action1 is before us the second

time.2

Appellee Margaret Townsend, a black female, began

work on June 22, 1965 as a blood bank technician, at the

Nassau County Medical Center, a county facility subject

to the New York Civil Service Law. When Mrs. Townsend

was appointed provisionally as a “ Senior Laboratory

Technician,” that position required graduation from high

1 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

2 On June 21, 1976, this court by order vacated a judgment for the

plaintiff entered in the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of New York after a trial before the Hon. Jack B. Weinstein.

We remanded the case "for reconsideration in the light of W ashington

v. Davis [426 U.S. 229 (1976)], particularly Part III thereof.” On

remand, Judge Weinstein confirmed his original order and the judg

ment for the plaintiff described below. The defendants now seek re

view of both judgments.

25a

school, completion of an approved two-year course in med

ical technology, and two years experience as a technician

in a medical laboratory or a satisfactory equivalent of a

combination of training and experience. As a result of a

survey conducted for the County by the firm of Cresap,

McCormick and Paget, the County adopted a reclassifica

tion of all County positions subject to Civil Service

effective July 7, 1967. Under the reclassification, Mrs.

Townsend’s job was designated “ Medical Technologist I”

and new prerequisites for appointment to a permanent

position were established. It became necessary to pass a

competitive examination which could be taken only by

those holding either a bachelor of science degree or a

certification by the American Society of Clinical Pathol

ogists ( “ASCP” ).3 The County mitigated these new re

quirements, however, with a “grandfather clause” provid

ing that incumbents who had served at least one year prior

to July 7, 1967, in positions whose prerequisites were af

fected by the reclassification adopted by the County Civil

Service Commission, would be permitted once to take the

examination for his new title, regardless of the announced

training and experience requirements, “but that for ’ en

suing examinations it would be necessary for him as well

as all other candidates to meet the qualification require

ments of the test announcements.” 4

Appellee Townsend was accordingly permitted to take

the examination given in 1971, although she had neither

a college degree nor ASCP certification. Unfortunately,

she failed to pass the examination. Another person in the

same blood bank, also without the requisite academic

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 30, 1977

3 One of the requirements for ASOP certification was a B.S. degree.

4 Specifically, incumbents would be permitted to take the first examina

tion administered a fter the promulgation' of the "grandfather clause”

on December 9, 1968.

26ci

qualification, passed it. Mrs. Townsend was, nevertheless,

permitted to continue as a Medical Technologist I in a

provisional status because the list of eligibles resulting

from the 1971 examination was insufficient to fill all

positions.

A second examination for Medical Technologist I was

administered in April, 1973. In accordance with the limited

“grandfather clause,” Mrs. Townsend’s application to take

the examination was rejected by the Nassau County Civil

Service Commission, because she lacked the formal edu

cational qualifications. As a result of the promulgation

of a Medical Technologist I eligible list based upon the

1973 examination, Mrs. Townsend was discharged in De

cember of 1973. Three white incumbents were similarly

discharged. See note 8, infra. Three months later appellee

was rehired by the blood bank and given the duties of a

Medical Technologist I. However, she was placed in the

lower paying classification of a Laboratory Technician II.

In short, Mrs. Townsend was, as the litigants and the

District Court recognized, in effect demoted to a lower

paying classification because she lacks the formal academic

prerequisites to take future examinations which were im

posed some years after she began her employment, and

because she failed the “grace” examination.

Mrs. Townsend then brought suit for reinstatement with

back pay, alleging that the requirement of either a B.S.

degree or ASCP certification violates Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 F.S.C. § 2000e et seq. The

essence of her Title VII theory is that the requirement of

a B.S. degree or an ASCP certification has a dispropor

tionate racial impact since far fewer blacks than whites

in the general population have college degrees; and that

the requirement violates Title VII because it is insuffi

ciently job-related.

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 30, 1977

27 a

After a trial without a jury, the District Court held that

appellee had established a prima facie case of discrimina

tion and that appellants had not met their burden of

justifying the academic prerequisites as job-related in

their application to Mrs. Townsend. A distinction was

perceived, however, between the rights of a person holding

a job and a person seeking a job in the first instance. The

District Court expressly disclaimed any intention to ad

judicate generally whether these academic requirements

were sufficiently job-related to be valid. Rather, it held

that Title VII mandates that an employer must recognize

the actual demonstrated job skills of a minority employee

whether those skills are acquired through practical ex

perience or through formal training. The court ruled that

the educational requirements could not be applied so as

to exclude a black employee “ from a position for which she

has demonstrated eminent qualifications.”

In finding that the academic prerequisites were “ inher

ently discriminatory”—i.e., in finding a prima facie case

of discrimination—Judge Weinstein recognized that the

defendants had acted in good faith and with good inten

tions. Nevertheless, he observed that a job requirement

violates Title VII if it has a racially disproportionate im

pact. Griggs v. Duke Poiver Co., 401 TJ.S. 424 (1971).

Noting that, in the general populations of Nassau County

and New York State, proportionately far more whites

have college degrees than do blacks— and especially female

blacks—Judge Weinstein concluded that this statistical

evidence of educational disparity was itself enough to

establish the disproportionate racial impact of a degree

requirement.

Having concluded that “ a college degree requirement

discriminates against blacks in New York State and Nas

sau County,” Judge Weinstein next considered whether

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 30, 1977

28a

appellants had shown that this requirement was job-related.

See Griggs, supra; Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 (1975). He found no evidence indicating that

persons with college degrees perform better as medical

technologists than those who do not. The District Court

concluded that since the plaintiff bad demonstrated her

actual job qualifications by on-the-job performance, a col

lege degree could not be required as a prerequisite to em

ployment in her case. The court limited its ruling on the

validity of the degree requirement, however, to “ the special

circumstances of the case before us.” In short, the ruling

of the District Court amounted to an ad hoc determination

that Mrs. Townsend, by virtue of her demonstrable skill

in the hlood bank, was entitled to take another examination,

and to retain her provisional status, without any time lim

itation, despite the existence of an unfilled eligible list.

The District Court, accordingly, ordered that: (1) plain

tiff Townsend be reclassified as a provisional Medical

Technologist I retroactive to December 31, 1973; (2) plain

tiff be awarded back-pav for 1974 and 1975; and (3) plain

tiff not be disqualified from taking future civil service

examinations for permanent classification as Medical

Technologist I by reason of her not having a college de

gree or certification by AS CP. The court made no provi

sion for how long the plaintiff could remain in provisional

status without passing an examination.

Mrs. Townsend can gain redress in the federal court

only if she has suffered discrimination—-either intentional

or “objective”—-because of her race or sex, or upon the

ground that substantive due process protects incumbent

job-holders from standards for permanent qualification

created only after years of satisfactory service on the joh.

We agree with the Nassau County defendants that ap

pellee did not prove a prima facie case of racial discrimi

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 30, 1977

29a

nation against herself under Title VII and that she was

not denied any “ substantive due process” right.

As far as the prima facie case of discrimination is con

cerned, appellee adduced no evidence whatsoever of inten

tional discrimination, past or present, either by the County

or by the Medical Center. It is well-established, however,

that a prima facie case may be made through evidence that

an employment test or qualification has as a consequence

“ an exclusionary effect on minority applicants.” McDon

nell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 803 n.14 (1973).

See Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 252 (1976). Even

as far as adverse racial impact is concerned, however, the

only evidence offered by appellee were 1970 census statis

tics showing that in Nassau County college degrees are

held by only 12.4% of blacks age 25 years or over, as op

posed to 34.5% of whites, and by only 4.7% of black fe

males, as opposed to 11.8% of white females.5 There were

no statistics for the B.S. degree in particular.

Neither Griggs, supra, nor Johnson v. Goodyear Tire &

Rubber Co., 491 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir. 1974), or United States

v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir. 1973), relied

upon by appellee, support the proposition that statistical

evidence concerning only the general population is suf

ficient to demonstrate that a job prerequisite “ operates to

exclude” minorities. In all of these cases plaintiffs estab

lished that virtually no blacks were in fact able to satisfy

the challenged job qualification and obtain employment

with the defendant.6

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 30, 1977

5 Similar statistics eoneerning the population of New York State as

a whole were also submitted into evidence.

6 It is true that in Griggs, as well as Georgia Pow er, and Goodyear

Tire Sr R ubber Co., the courts noted that the educational requirements

at issue were satisfied only by a disproportionately low number of

blacks. See 401 U.S. at 430 n.6; 491 F.2d at 1371; 474 F.2d at 918.

But these statistics eoneerning the general population were relevant,

30a

I f we were to hold that a bare census statistic concern

ing the number of blacks in the general population who

have college degrees could establish a prima facie case of

discrimination, every employer with a college degree re

quirement would have the burden of justifying the degree

requirement as job-related. See Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). The burden of showing job-

relatedness cast upon the employer does not arise until

due discriminatory effect has been shown. General Electric

Co. v. Gilbert,:------ U .S .------ , 97 S. Ct. 401, 408-09, 45

U.S.L.W. 4031 at 4034 n.14 (Dec. 7, 1976). “ This burden

arises, of course, only after the complaining party or class

has made out a prima facie case of discrimination.” Albe

marle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425 (1975). We

do not believe that a statistic relating only to the general

population, and not to the employment practices of the par

ticular defendant, should be sufficient to raise such a pre

sumption against a college degree requirement. The

requirement of a college degree, particularly in the sciences,

seems to be in the modern day of advanced scientific

method, a neutral reqirirement for the protection of the

public. No doubt such a requirement could serve as a pre

text for racial or sex discrimination, but this consequence

should not be assumed. There will be time, if a showing of

racial impact is made, for the comparison of the require

ment of a degree in medicine, law, engineering or other

professions with such a requirement for a laboratory

technologist who is required by her Civil Service Title to

be skillful in clinical chemistry, microbiology, blood-bank

ing, serology, and hematology in more than one laboratory.

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 20, 1977

not to establish the prima laeie case of discrimination which had al

ready been made, bnt to demonstrate that the racially disparate impact

on defendant emnloyer’s workforce which was otherwise established,

was due to the challenged ;job requirement, and not to some other prac

tice of the employer or other cause.

31a

The relative function of the academic prerequisites to job

relatedness varies inversely with the risk to the health and

safety of the public who depend upon the technology. See

Spurlock v. United Airlines, Inc., 475 F.2d 216 (10th Cir.

1972) (college degree for flight officer held job-related);

Hodgson v. Greyhound Lines. Inc., 499 F.2d 859, 862 (7th

Cir. 1974); 29 C.F.R. 1607.5(c) (2) ( i i i ) : “ . . . a relatively

low relationship may prove useful when the [economic and

human] risks are relatively high.” The issue will be

whether a B.S. degree is substantially related to job per

formance. Cf. Griggs, supra, 401 U.8. at 431. But the fields

of scientific knowledge are too disparate, and cover too

many disciplines, for the mere existence of general college

degree statistics in the general population, without more,

to sustain a presumption of racial discrimination.

In refusing to adjudicate whether the college degree re

quirement discriminated against i lacks in general, includ

ing potential future applicants, the District Court itself

recognized that the adoption of a college degree require

ment cannot, merely because of the general racial composi

tion of college graduates, be considered discriminatory.

Judge Weinstein noted that Though no direct evidence

was presented on this point, a degree or its equivalent might

guarantee that new applicants possess the skills and learn

ing needed for successful training in the blood bank. This

question would have to be expired in any future

litigation.” 7

It was precisely because the District Court was unwilling

to hold that the requirement of a E,S. degree, neutral on

its face, makes out a per se violation, that the District

Court had to award relief to Mrs. Townsend on an ad hoc

basis.

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 20, 1977

7 The District Court credited the testimony of Mr. Applewhaite, the

supervisor, "that a college degree might be useful.”

32a

Unfortunately, we see no legal ground for such ad hoc

relief. Surely, if we restrict our consideration to Mrs.

Townsend individually, no inference of racial discrimina

tion against her alone is possible, cf. McDonnell Douglas

v. Green, supra. When the new job qualifications were

promulgated she was “grandfathered” into one examina

tion despite her acknowledged lack of the threshold pre

requisite academic standing. Although she failed this

examination, there is no claim—nor was evidence adduced

—that the examination violated Title VII. Indeed, at least

one incumbent afforded the opportunity to take the “grand

father” exam, passed it. And of the four incumbents who,

like Mrs. Townsend, were demoted for failure to satisfy

the new job requirements, three were white.8 In short,

the newly promulgated prerequisites, neutral on their face,

were applied to each employee at the blood bank in a uni

form and racially neutral manner.