Motion to Dismiss Appeal

Public Court Documents

January 24, 1972

92 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Motion to Dismiss Appeal, 1972. d81b5180-52e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2002ef50-85a8-424b-87fa-74787ddf863f/motion-to-dismiss-appeal. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

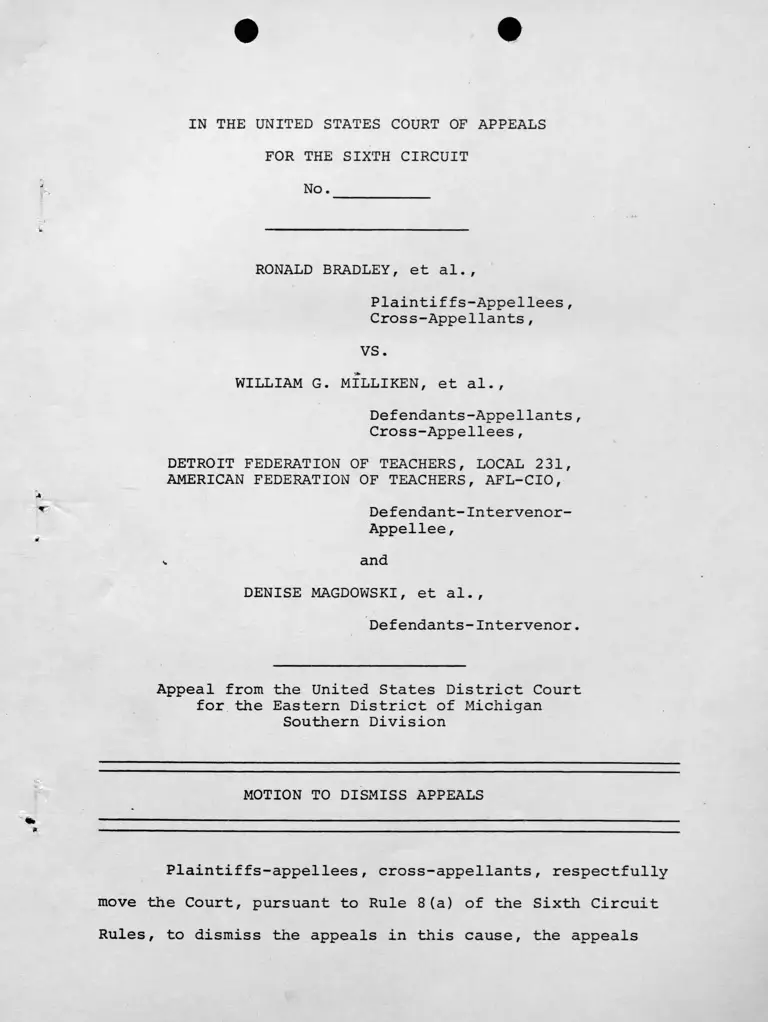

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

Cross-Appellants,

VS.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants,

Cross-Appellees,

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231,

AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-Intervenor-

Appellee,

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-Intervenor.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Michigan

Southern Division

MOTION TO DISMISS APPEALS

Plaintiffs-appellees, cross-appellants, respectfully

move the Court, pursuant to Rule 8(a) of the Sixth Circuit

Rules, to dismiss the appeals in this cause, the appeals

• •

being not within the jurisdiction of the Court at this

juncture of this litigation.

As grounds for this motion, plaintiffs would show

the following:

BACKGROUND

Procedural History of the Litigation

Plaintiffs commenced this litigation on August 18,

1970, against the Board of Education of the City of

Detroit, its members and superintendent of schools, the

Governor, Attorney General, State Board of Education and

State Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State

of Michigan. Plaintiffs challenged, on constitutional

grounds, a legislative enactment of the State of Michigan

which interferred with the implementation of a voluntary

plan of partial high school pupil desegregation which had

been adopted by the Detroit Board of Education. Plaintiffs

further alleged the existence of a racially identifiable

pattern of faculty and student assignments in the Detroit

Public Schools which pattern was the result of official

policies and practices of the defendants and their predecessors

in office.

At the conclusion of a hearing held upon plaintiffs'

application for preliminary injunctive relief the district

court denied all relief on the grounds that the existence

of racial segregation had not yet been established. The

court further dismissed the action as to the State defendants.

On appeal, this Court declared the challenged Michigan statute

to be unconstitutional and reinstated the State defendants

2

as parties. 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970).

Upon remand, plaintiffs moved in the district court

for an order requiring immediate implementation of the volun

tary plan of partial desegregation which had been impeded by

the unconstitutional State statute. After receiving

additional plans preferred by defendants and conducting

a hearing thereon, the district court entered an order

approving an alternate plan which plaintiffs opposed

as being constitutionally insufficient. Plaintiffs again

appealed, but this Court Refused to reach the merits

of the appeal and remanded the case to the district court

with instructions that the entire case be tried on its

merits forthwith. 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971).

After a lengthy trial the district court, on

September 27, 1971, entered its "Ruling on Issue of Segre

gation." (Attached hereto as Appendix A). The court

concluded that the public schools in Detroit are "segregated

on a racial basis" (App. A at 15) and that both state and

local defendants "have committed acts which have been causal

factors in the segregated condition...." (App. A at 25).i/

The court and the parties then turned to the problem

of relief. Plaintiffs sought (and seek) conversion of the

— These findings and conclusions pertain to the pattern

of pupil assignments only, as the court declined to find the pre

sent pattern of faculty assignments to be unconstitutional

(as alleged by plaintiffs). (App. A at 18-24).

3

Detroit school system from a racially segregated to a

racially unitary one. The intervening parent defendants.?/

h3.d filed, at the conclusion of the trial, a motion to add

as parties defendant numerous suburban school districts "on

the principal premise or ground that effective relief

cannot be achieved or ordered in their [other districts']

absence. -?/ (App. A at 34) . The court, however, deferred

decision on the content and extent of the remedy until the

completion of further proceedings. (App. A at 34-35).

On October 4, 19 71>>- the district court conducted in open court

a"pre-trial conference [the transcript of which is attached

hereto as Appendix B] on the matter of relief." (App. A at 35). At the

conclusion of the conference the court directed both the

Detroit Board defendants and the State defendants to submit

proposed plans of pupil desegregation on specified dates.

(App. "B at 26-27) . These directions were subsequently

incorporated into an order filed on November 5, 1971

(Appendix C, attached hereto). It is from this order that

1/prior to the trial on the merits the district

court permitted the Detroit Federation of Teachers and a

group of white parents to intervene as parties defendant.

3/The parent-intervenors had intervened for the

purpose of defending the "neighborhood school concept,"

but had lost all hope of success by trial's end. (See

statement of attorney for parent-intervenors, App. B at 15).

4

both the Detroit Board defendants (Annendix D) and the

State defendants (Appendix E) noticed anneals on December 3,

1971. Although nlaintiffs have, from the outset, questioned

the "appealability" of the district court's order, we filed

a nrotective notice of anneal (Annendix F) on December 11,

1971, challenging the court's failure to require further

faculty desegregation.!./

The Substance of the Order Appealed From

At the pre-trial conference of October 4, 1971, the

district court directed the Detroit Board defendants (1) to

submit within 30 days a progress report on and an evaluation

of the Magnet School Plan (under which the Board if presently

operating), and (2) to submit within 60 days a nlan for the

desegregation of the Detroit public schools. (App. B at 26-27).

Further, the court directed the State defendants to submit

within 120 days a metropolitan plan of desegregation. (App B

at 2 1)

After these directions were delivered, the following

occurred:

THE COURT: ....The time table is

understood, is it?

MR. BUSHNELL: Yes, sir.

MR. LUCAS: Yes.

THE COURT: I am not going to— unless you

gentlemen want— to prepare an order, I am not

going to prepare a formal order.

4/— Should the Court determine, in accordance with this

motion, that defendants' anneals should be dismissed, then

nlaintiffs request that their protective cross-appeal also

be dismissed.

5

MR. BUSHNELL: I don't believe it is

necessary, your Honor. We understand the

timetable.

THE COURT: Anybody disagree with that?

[No response]

(App. B at 29). The State defendants subsequently insisted

on a formal order (see Appendix G), however, which was

entered on November 5, 1971 (Ad d . C).

In accordance with the court's direction the Detroit

Board defendants filed, on November 3, 1Q71, a report on the

Magnet School Program, and on December 3, 1971, they submitted

♦ # two alternative Droposed plans for desegregation of Detroit

schools—^ and a statement setting forth the Board's preference

for metrooolitan desegregation.

The plan required to be submitted by the State defen

dants is due to be filed within two weeks.

REASONS WHY THE APPEALS SHOULD BE DISMISSED

It was permissible for State defendants to insist

upon a formal order, desoite their previous waiver, for

"It!he filing of an opinion by the District Court does

not constitute the entry of an order, judgment or decree

from which an anpeal can be taken." Robinson v. Shelby

County Board of Educ., No. 71-1825 (6th Cir., order of

Nov. 8, 1971) (attached hereto as Appendix H). But it is

npt .eyepy qpder.that may be appealed, for this Court only

\ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \ \

r — - r -n * i' ■».

•^/plaintiffs promptly filed objections to the Detroit

Board's proposed plans and are presently preparing their

own alternatives for submission to the district court.

- 6 -

has jurisdiction of appeals from "final decisions" (28

U.S.C.A. §1291) and certain classes of "interlocutory"

orders (28 U.S.C.A. §1292(a)).£/

Clearly the order appealed from is not a "final

decision" within the meaning of 28 U.S.C.A. §1291.

It [the order] constituted only a

determination that plaintiffs were

entitled to relief, the nature and

extent of which would be the subject

of subsequent judicial consideration

by [the district court]. What remain[s]

to be done [is] far more than those

ministerial- duties the pendency of which

is not fatal to finality and consequent

appealability....

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 288 F.2d 600,

602 (2d Cir. 1961).

The only possible source for this Court's juris

diction over the instant appeals is 28 U.S.C.A. §1292(a) (1).

TaylCr, supra, 288 F.2d at 603 . And for the reasons set

forth in Judge Friendly's opinion in Taylor, we submit that

the Court is without jurisdiction to hear the instant

appeals.

§1292 (a)(1), in pertinent part, gives this Court

jurisdiction of appeals from interlocutory orders "granting,

continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving injunctions....

—^Certain "certified" orders "not otherwise appealable"

may, with the permission of the court of appeals, be appealed

pursuant to the provisions of 28 U.S.C.A. §1292(b). In the

instant case the necessary certificate has not been entered by

the district court, nor has such certification been requested.

7

The issue here is whether or not the district court has

entered an "order granting an injunction." We believe

that no such order has been entered in this case.

The order appealed from does but one thing: it

directs defendants to submit a report and plans for deseg

regation, and it permits other parties to file objections

and alternate plans. The order does not even require the

taking of preparatory steps for subsequent implementation

of a plan of desegregation. At the pre-trial conference of

4

October 4, 1971, Judge Roth made it clear that he "had no

preconceived notion about what the Board of Education should

do in the way of desegregating its schools nor the outlines

of a proposed metropolitan plan. The options are completely

open." (App. B at 27).

To be sure, the... [order] used the word

"ordered" with respect to the filing of

a plan, just as courts often "order" or

"direct" parties to file briefs, findings

and other papers. Normally this does not

mean that the court will hold in contempt

a party that does not do this.... [But] even

if the order was intended to carry contempt

sanctions ... a command that relates merely

to the taking of a step in a judicial pro

ceeding is not generally regarded as a

mandatory injunction, even when its effect

on the outcome is far greater than here.

For ... not every order containing words

of command is a mandatory injunction within

[§1292(a) (1)].

Taylor, supra, 288 F.2d at 604. Nor may defendants contend

that they will suffer irreparable injury by complying with

the order.

8

[W]hile we understand defendants' dislike

of presenting a plan of desegregation and

attending hearings thereon that would be

unnecessary if the finding of liability

were ultimately to be annulled, and also

the possibly unwarranted expectations this

course may create, this is scarcely injury

at all in the legal sense and surely not

an irreparable one.

Id. at 603.

To allow defendants' appeals at this juncture will

surely result in (1) protracted piecemeal appellate litigation,

depriving the Court of the opportunity for fully informed

consideration of the important issues to be presented, and/or

(2) appellate litigation which may be unnecessary as to all

oor some of the present parties appellant and all or some of

the issues to be presently raised.

[T]o permit a hearing on relief to go

forward in the District Court at the

very time we are entertaining an appeal,

with the likelihood, if not indeed the

certainty, of a second appeal when a

final decree is entered by the District

Court, would not be conducive to the

informed appellate deliberation and the

conclusion of this controversy with speed

consistent with order, which the Supreme

Court has directed and ought to be the

objective of all concerned. In contrast,

prompt dismissal of the appeal as pre

mature should permit an early conclusion

of the proceedings in the District Court

and result in a decree from which defendants

have a clear right of appeal, and as to

which they may then seek a stay pending

appeal if so advised. We — and the Supreme

Court, if the case should go there — can

then consider the decision of the District

Court, not in pieces but as a whole, not as

an abstract declaration inviting the contest

of one theory against another, but in the

concrete.

9

Taylor, supra, 288 F.2d at 605. The Taylor court refers,

critically, to an unreported order of this Court denying

a motion to dismiss in an early appeal in Mapp v. Board of

Educ. of Chattanooga. The Court's criticism is based,

in part, on the developments in Mapp after the motion to

dismiss the appeal was denied (288 F.2d at 605):

Moreover, the subsequent proceedings

in the Mapp case, where the District

Court has already rejected the plan

directed to be filed and required the

submission of a new one, with a second

appeal taken from that order although

the first appeal has not yet been heard,

indicate to us the unwisdom of following

that decision even if we deemed ourselves

free to do so.

A situation similar to that in Mapp occurred in

Robinson v. Shelby County Board of Educ., Nos. 20,123

20,124 (6th Cir., order of June 25, 1970) (attached hereto

as Appendix I), where the school board had appealed from

a decision requiring the submission of new plans. While

the appeals were pending, however, the new plans were received

by the district court and a new order was entered from which

a new appeal had been taken. This Court dismissed the pending

appeals as being moot. (App. I at 3).

In the instant case the Detroit Board defendants

have already submitted plans in accordance with the order,

and the State defendants will submit their plans within two

weeks. Thus, long before briefs are filed in this appeal,

10

the order from which defendants appeal will have, "by its

9 /terms, expired." Robinson, supra, App. I at 3.—7

WHEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs

respectfully pray that, after the time allowed for responses

to this motion has elapsed, the Court enter an order dismissing

the appeals herein.

OF COUNSEL:

J. HAROLD FLANNERY

PAUL R. DIMONO

ROBERT PRESSMAN

Center for Law & Education

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Respectfully submitted,

RATNER, SUGARMON & LUCAS

By LOUIS R. LUCAS

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

NATHANIEL R. JONES

General Counsel, N.A.A.C.P.

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. WINTHER McCROOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellees, Cross-Appellants

2/The State defendants have attempted to meet this

problem by stating in their Notice of Appeal (App. E)

that they appeal "from the order entered herein on November

5, 1971, which incorporates the findings of fact and con

clusions of law___" Saying it doesn't make it so, however,

and even if it did the order is clearly not a "final" judg

ment; State defendants can only challenge what the order

requires them to do, which will shortly be mooted (putting

aside the question as to the appealability of the order in

the first instance).

11

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing motion

has been served upon counsel of record by United States mail,

postage pre-paid, addressed as follows:

George T. Roumell, Jr., Esq.

Riley and Roumell

7th Floor, Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Eugene Krasicky, Esq.

Assistant Attorney General

Seven Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Theodore Sachs, Esq.

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Alexander B. Ritchie

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

This day of January, 1972.

William E. Caldwell

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

PI ai nti ffs

vs.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL #231, AMERICAN FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, ^

Defendant-Intervenor

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al . ,

Defendants-Intervenor

RULING ON ISSUE OF SEGREGATION

This action was commenced August 18, 1970, by

plaintiffs, the Detroit Branch of the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People* and individual

parents and students, on behalf of a class later defined

by order of the Court dated February 16, 1971, to include

“all school children of the City of Detroit and all

Detroit resident parents who have children of school age."

*The standing of the NAACP as a proper party plaintiff

was not contested by the original defendants and the Court

expresses no opinion on the matter

CIVIL ACTION NO

35 257

APPENDIX A

Defendants are the Board of Education of the City

of Detroit, its members and its former superintendent

of schools, Dr, Norman A. Drachler, the Governor,

Attorney General, State Board of Education and

State Superintendent of Public Instruction of the

State of Michigan, In their complaint, plaintiffs

attacked a statute of the State of Michigan known

as Act A8 of the 1970 Legislature on the ground

that it put the State of Michigan in the position

of unconstitutionally interfering with the execu-

tion and operation of a' voluntary plan of partial

high school desegregation (known as the April 7>

1970 Plan) which had been adopted by the Detroit

Board of Education to be effective beginning with

the fall 1970 semester. Plaintiffs also alleged

that the Detroit Public School System was and is

segregated on the basis of race as a result of

the official policies and actions of the defendants

and their predecessors in office.

Additional parties have intervened in the

litigation since it was commenced. The Detroit

Federation of Teachers (DFT) which represents a

majority of Detroit Public school teachers in

collective bargaining negotiations with the defendant

Board of Education, has intervened as a defendant, and

a group of parents has intervened as defendants.

Initially the matter was tried on plaintiffs1

motion for preliminary injunction to restrain the en

forcement of Act 48 so as to permit the April 7>

Plan to be implemented. On that issue, this Court

ruled that plaintiffs were not entitled to a pre

liminary injunction since there had been no proof

that Detroit has a segregated school system. The

Court of Appeals found that the "implementation of

the April 7» Plan was thwarted by State action in

the form of the Act of~*the Legislature of Michigan,"

(433 F.2d 897, 902), and that such action could not

be interposed to delay, obstruct or nullify steps *

lawfully taken for the purpose of protecting rights

guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The plaintiffs then sought to have this

Court direct the defendant Detroit Board to implement

the April 7, Plan by the start of the second semester

(February, 1971) in order to remedy the deprivation

of constitutional rights wrought by the unconstitu

tional statute. In response to an order of the

Court, defendant Board suggested two other plans,

along with the April 7, Plan, and noted priorities,

with top priority assigned to the so-called "Magnet

Plan." The Court acceded to the wishes of the Board

and approved the Magnet Plan. Again, plaintiffs

appealed but the appellate court refused to pass on

the merits of the plan. Instead, the case was re

manded with instructions to proceed immediately to a

- 3 -

trial on the merits of plaintiffs' substantive al

legations about the Detroit School System.

1+38. F2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971 ).

Trial, limited to the issue of segregation,

began April 6, 1971 and concluded on July 22, 1971,

consuming 41 trial days, interspersed by several

brief recesses necessitated by other demands upon

the time of Court and counsel. Plaintiffs intro

duced substantial evidence in support of their

contentions, including .expert and factual testimony,

demonstrative exhibits and school board documents.

‘At the close of plaintiffs1 case, in chief, the

Court ruled that they had presented a prima facie

case of state imposed segregation in the Detroit

Public Schools accordingly, the Court enjoined

(with certain exceptions) all further school con

struction in Detroit pending the outcome of the

1i ti gation.

The State defendants urged motions to dismiss

as to them. These were denied by the Court.

At the close of proofs intervening parent

defendants (Denise Magdowski, et al ) filed a motion

to join, as parties, 85 contiguous "suburban" school

.districts - all within the so-called Larger Detroit

Metropolitan area. This motion was taken under

advisement pending the determination of the issue

of segregation.

It should be noted that, in accordance

with earlier rulings of the Court, proofs submitted

- 4 -

• •

at previous hearings in the cause, were to be and

are considered as part of the proofs of the hearing

on the merits.

In considering the present racial complexion

of the City of Detroit and its public school system

we must first look to the past and view in perspective

what has happened in the last half century. In 1920,

Detroit was a predominantly white city - 91% - and

its population younger than in more recent times.

By tf?e year I960 the largest segment of the city's

white population was in the age range of 35 to 50

years, while its black population was younger and

of childbearing age. The population of 0-15 years

of age constituted 30% of the total population of

which 60% were white and 40% were black. In 1970

the white population was principally aging— 45 years—

while the black population was younger and of child

bearing age. Childbearing blacks equaled or exceeded

the total white population. As older white families

without children of school age leave the city they

are replaced by younger black families with school

age children, resulting in a doubling of enrollment

in the local neighborhood school and a complete

change in student population from white to black. As

black inner city residents move out of the core city

they "leap-frog" the residential areas nearest their

former homes and move to areas recently occupied by

whi tes.

- 5 -

m population of the City (^Detroit reached

its highest point in 1950 and has been declining by

approximately 169,500 per decade since then. In 1950,

the city population constituted 61% of the total popu

lation of the standard metropolitan area and in 1970

it was but 36% of the metropolitan area population. The

suburban population has increased by 1,978,000 since

1940. There has been a steady out-migration of the

Detroit population since 1940. Detroit today is

principally a conglomerate of poor black and white

plus the aged. Of the aged, 80% are white.

->

If the population trends evidenced in the

federal decennial census for the years 1940 through

o

1970 continue, the total black population in the City

of Detroit in 1980 will be approximately 840,000, or

53.6% of the total. The total population of the city

in 1970 is 1,511,000 and, if past trends continue, will be

1,338,000 in 1980. In school year 1960-61, there were

285,512 students in the Detroit Public Schools of which

130,765 were black. In school year 1966-67, there were

297,035 students, of which 168,299 were black. In

school year 1970-71 there were 289,743 students of which

184,194 were black. The percentage of black students in

the Detroit Public Schools in 1975-76 will be 72.0%,

in 1980-81 will be 80.7% and in 1992 it will be virtually

100% if the present trends continue. In I960, the nonwhite

population, ages 0 years to 19 years, was as follows:

- 6 -

0 - 4 years 42%

5*- 9 years 36%

10 - 14 year s 28%

15 - 19 year s 18%

1 n 1970 the nonwhi te popula tion, ages 0

was as follows:

0 - 4 years 48%

5 - 9 years 50%

10 - 14 year s 50%

15 - 19 year:s 40%

The black population <3 S a percentage of

tion in the City of Detroit was:

(a) 1900 1.4%

(b) 1910 1. 2 %

<c) 1920 4.1%

(d) 1930 7.7%

(e) 1940 9.2%

(f) 1950 16.2%

(g) I960 28 .9%

(h) 1970 43 .9%

The black population as a percentage of total student

population of the Detroit Public Schools was as follows:

(a) 1961 45.8%

(b) 1963 51.3%

(c) 1964 53.0%

(d) 1965 54.8%

(e). 1966 56.7%

(f) 1967 58.2%

(g) 1968 59.4%

- 7 -

(h) 1969 61.5%

(1) 1970 63.8%

For the years indicated the housing characteristics

in the City of Detroit were as follows:

(a) I960 total supply of housing units

was 553,000

(b) 1970 total supply of housing units

was 530,770

The percentage decline in the white students in

the Detroit Public Schools during the period 1961-1970

(53.6% in I960; 34.8% in 1970) has been greater than

the percentage decline-in the white population in

the City of Detroit during the same period (70.8% in

I960; 55.21% in 1970), and correlatively, the percentage

increase in black students in the Detroit Public

Schools during the nine-year period 1961-1970 (45.8%

in 1961; 63.8% in 1970) has been greater than the

percentage increase in the black population of the

City of Detroit during the ten-year period 1960-1970

(28.9% in I960; 43.9% in 1970). In 1961 there were

eight schools in the system without white pupils and

73 schools with no Negro pupils. In 1970 there were

30 schools with no white pupils and 11 schools with

no Negro pupils, and increase in the number of schools

without white pupils of 22 and a decrease in the number

of schools without Negro pupils of 62 in this ten-year

period. Between 1968 and 1970 Detroit experienced the

largest increase in percentage of black students in the

- 8 -

student population of any major northern school dis

trict, The percentage increase in Detroit was k , 7 %

as contrasted with —

New York 2.0%

Los Angeles 1.5%

Chi cago 1.9%

Phi 1adelphi a 1.7%

Cleveland 1.7%

Mi 1waukee 2.6%

St. Louis 2.6%

Columbus 1 A %

Indianapoli s 2.6%

Denver 1.1%

Boston 3.2%

San Francisco 1.5%

Seattle 2 . k %

In I960, there were 266 schools in the

Detroit School System. In 1970, there were 319 schools

in the Detroit School System.

In the Western, Northwestern, Northern,

Murray, Northeastern, Kettering, King and Southeastern

high school service areas, the following conditions

exist at a level significantly higher than the city

average:

(a) Poverty in children

(b) Family income below poverty level

- 9 -

(d) Number of households headed by females

(e) Infant mortality rate

(f) Surviving infants with neurological

defects

(g) Tuberculosis cases per 1,000 population

(h) High pupil turnover in schools

The City of Detroit is a Community generally

divided by racial lines. Residential segregation

within the city and throughout the larger metropolitan

area is substantial, pervasive and of long standing.

Black citizens are located in separate and distinct

areas within the city and are not generally to be

o

found in the suburbs. While the racially unrestricted

choice of black persons and economic factors may have

played some part in the development of this pattern of

residential segregation, it is, in the main, the re

sult of past and present practices and customs of

racial discrimination, both public and private, which

have and do restrict the housing opportunities of

black people. On the record there can be no other

finding.

Governmental actions and inaction at all

levels, federal, state and local, have combined, with

those of private organizations, such as loaning insti

tutions and real estate associations and brokerage

firms, to establish and to maintain the pattern of

residential segregation throughout the Detroit metro

- 10 -

politan area. It is no answer to say that restricted

practices grew gradually (as the black population in

the area increased between 1920 and 1970), or that

since 19^8 racial restrictions on the ownership of

real property have been removed. The policies pur

sued by both government and private persons and agencies

have a continuing and present effect upon the com

plexion of the community - as we know, the choice of a

residence is a relatively infrequent affair. For

many years FHA and VA openly advised and advocated the

maintenance of "harmonious" neighborhoods, i_.e.,

racially and economically harmonious. The conditions

created continue. While it would be unfair to charge

the present defendants with what other governmental

officers or agencies have done, it can be said that

the actions or the failure to act by the responsible

school authorities, both city and state, were linked to

that of these other governmental units. When we speak

of governmental action we should not view the different

agencies as a collection of unrelated units. Perhaps

the most that can be said is that all of them, including

the school authorities, are, in part, responsible for the

segregated condition which exists. And we note that

just as there is an interaction between residential

•patterns and the racial composition of the schools, so

there is a corresponding effect on the residential pattern

- 11

by the racr composition of the schoo •

Turning now to the specific and pertinent (for

our purposes) history of the Detroit school system so

far as it involves both the local school authorities

and the state school authorities, we find the following:

During the decade beginning in 1950, the

Board created and maintained optional attendance zones

in neighborhoods undergoing racial transition and

between high school attendance areas of opposite pre

dominant racial compositions. In 1959 there were

eight basic optional attendance areas affecting 21

schools. Optional attendance areas provided pupils

living within certain elementary areas a choice of

attendance at one of two high schools. In addition

there was at least one optional area either created or

existing in I960 between two junior high schools of

opposite predominant racial components. All of the

high school optional areas, except two, were in neigh

borhoods undergoing racial transition (from white to

black) during the 1950’s. The two exceptions were:

(1) the option between Southwestern (61.6% black in

I960) and Western (15.3% black); (2) the option be

tween Denby (0% black) and Southeastern (30.9% black).

With the exception of the Denby-Southeastern option

(just noted) all of the options were between high

schools of opposite predominant racial compositions.

The Southwestern-Western and Denby-Southeastern op

tional areas are all white on the 1950, I960 and

1970 census maps. Both Southwestern and South

eastern, however, had substantial white pupil popu

lations, and the option allowed whites to escape

integration. The natural, probable, forseeable and

actual effect of these optional zones was to allow

white youngsters to escape identifiably "black"

schools. There had also been an optional zone

(eliminated between 1956 and 1959) created in "an

attempt . . . to separate Jews and Gentiles within

the system," the effect of which was that Jewish

youngsters went to Mumford High School and Gentile

youngsters went to Cooley. Although many of these

optional areas had served their purpose by I960

due to the fact that most of the areas had become

predominantly black, one optional area (Southwestern-

Western affecting Wilson Junior High graduates) con

tinued until the present school year (and will con

tinue to effect 11th and 12th grade white youngsters

who elected to escape from predominantly black South

western to predominantly white Western high schools).

Mr. Henrickson, the Board's general fact witness, who

was employed in 1959 to, inter alia, eliminate optional

areas, noted in 1967 that: "In operation, Western

- 13 -

appears to be still the school to which white students

escape from predominantly Negro surrounding schools,"

The effect of eliminating this optional area (which

affected only 10th graders for the 1970-71 school

year) was to decrease Southwestern from 86.7% black

in 1969 to 7^.3% black in 1970.

The Board, in the operation of its transpor

tation to relieve overcorwding policy, has admittedly

bused black pupils past or away from closer white

schools with available space to black schools. This4 ' .*»

practice has continued in several instances in recent

years despite the Board's avowed policy, adopted in

1967, to utilize transportation to increase integration.

With one exception (necessitated by the burning

of a white school), defendant Board has never bused

white children to predominantly black schools. The

Board has not bused white pupils to black schools

despite the enormous amount of space available in

inner-city schools. There were 22,961 vacant seats

in schools 90% or more black.

The Board has created and latered attendance

zones, maintained and altered grade structures and

created and altered feeder school patterns in a manner

which has had the natural, probable and actual effect

of continuing black and white pupils in racially

segregated schools. The Board admits at least one in

stance where it purposefully and intentionally built

- -

and maintained a school and its attendance zone to

contain black students. Throughout the last decade

(and presently) school attendance zones of opposite

racial compositions have been separated by North-

South boundary lines, despite the Board's awareness

(since at least 1962) that drawing boundary lines

in an East-West direction would result in significant

integration. The natural and actual effect of these

acts and failures to act has been the creation and

perpetuation of school segregation. There has never «

been4a feeder pattern or zoning change which placed

a predominantly white residential area into a pre

dominantly black school zone or feeder pattern.

Every school which was 90% or more black in I960,

and which is still in use today, remains 90% or more

black. Whereas 65.8% of Detroit's black students

attended 90% or more black schools in I960, 7^.9% of

the black students attended 90% or more black schools

during the 1970-71 school year.

The public schools operated by defendant Board

are thus segregated on a racial basis. This racial

segregation is in part the result of the discriminatory

acts and omissions of defendant Board.

In 1966 the defendant State Board of Education

and Michigan Civil Rights Commission issued a Joint

Policy Statement on Equality of Educational Opportunity,

requiring that

- 15 -

"Local school boards must consider the

factor of racial balance along with other

educational considerations in making de

cisions about selection of new school sites,

expansion of present facilities . . . .

Each of these situations presents an

opportunity for integration."

Defendant State Board's "School Plant Planning Hand

book" requires that

"Care in site location must be taken if a

serious transportation problem exists or

if housing patterns in an area would re

sult in a school largely segregated on

racial, ethnic, or socioeconomic lines."

The defendant City Board has paid little heed to these

statements and guidelines. The State defendants have

similarly failed to take any action to effectuate

these policies. Exhibit NN reflects construction

(new or additional) at 14 schools which opened for

use in 1970-71; of these 14 schools, 11 opened over

90% black and one opened less than 10% black. School

construction costing $9,222,000 is opening at North

western High School which is 99.9% black, and new

construction opens at Brooks Junior High, which is

1.5% black, at a cost of $2,500,000. The construction

at Brooks Junior High plays a dual segregatory role;

not only is the construction segregated, it will re

sult in a feeder pattern change which will remove the

last majority white school from the already almost all

black MacKenzie High School attendance area.

- 16 -

Since 1959, the Board has constructed at

least 13 small primary schools with capacities of

from 300 to 400 pupils. This practice negates

opportunities to integrate, "contains" the black

population and perpetuates and compounds school

segregation.

The State and its agencies, in addition to

their general responsibility for and supervision of

public education, have acted directly to control

and maintain the pattern of segregation in the Detroit

*•

schools. The State refused, until this session of

the legislature, to provide authorization or funds

o

for the transportation of pupils within Detroit,

regardless of their poverty or distance from the

school to which they were assigned, while providing

in manyneighboring, mostly white, suburban districts

the full range of state supported transportation.

This and other financial limitations, such as those

on bonding and the working of the state aid formula

whereby suburban districts were able to make far larger

per pupil expenditures despite less tax effort, have

created and perpetuated systematic educational in

equal ities.

The State, exercising what Michigan courts

have held to be is "plenary power" which includes

power "to use a statutory scheme, to create, alter

reorganize or even dissolve a school district, despite

- 17 -

any desire of the school district, Its board, or

the Inhabitants thereof,*1 acted to reorganize the

school district of the City of Detroit.

The State acted through Act 48 to Impede,

delay and minimize racial integration in Detroit

schools. The first sentence of Sec. 12 of the Act

was directly related to the April 7, 1970 desegregation

plan. The remainder of the section sought to pre

scribe for each school in the eight districts criterion

of "free choice1* (open enrollment) and "neighborhood

schools" ("nearest school priority acceptance"),

which had as their purpose and effect the maintenance

of segregation.

In view of our findings of fact already noted

we think it unnecessary to parse in detail the activities

of the local board and the state authorities in the

area of school construction and the furnishing of

school facilities. It is our conclusion that these

activities were in keeping, generally, with the dis

criminatory practices which advanced or perpetuated

racial segregation in these schools.

It would be unfair for us not to recognize the

many fine steps the Board has taken to advance the

cause of quality education for all in terms of racial

integration and human relations. The most obvious of

these is in the field of faculty integration.

Plaintiffs urge the Court to consider allegedly

discriminatory practices of the Board with respect to

- 18 -

the hiring, assignment and transfer of teachers and

school administrators during a period reaching back

more than 15 years. The short answer to that must

be that black teachers and school administrative

personnel were not readily available in that period.

The Board and the intervening defendant union have

followed a most advanced and exemplary course in

adopting and carrying out what is called the "balanced

staff concept" which seeks to balance faculties in

each school with respect to race, sex and experience,

with primary emphasis on'race. More particularly, we

find:

1. With the exception of affirmative policies

designed to achieve racial balance in instructional

staff, no teacher in the Detroit Public Schools is

hired, promoted or assigned to any school by reason

of his race.

2. In 1956, the Detroit Board of Education

adopted the rules and regulations of the Fair Employment

Practices Act as its hiring and promotion policy and

has adhered to this policy to date.

3. The Board has actively and affirmatively

sought out and hired minority employees, particularly

teachers and administrators, during the past decade.

4. Between I960 and 1970, the Detroit Board

of Education has increased black representation among

its teachers from 23.3% to 42.1%, and among its

- 19 -

administrators from 4.5% to 37.8%.

5. Detroit has a higher proportion of black

administrators than any other city in the country.

6. Detroit ranked second to Cleveland in

1968 among the 20 largest northern city school dis

tricts in the percentage of blacks among the teaching

faculty and in 1970 surpassed Cleveland by several

percentage points.

7. The Detroit Board of Education currently

employs black teachers in a greater percentage than

•>*>

the percentage of adult black persons in the City of

Detroi t.

8. Since' 1967, more blacks than whites

have been placed in high administrative posts with the

Detroit Board of Education.

9. The allegation that the Board assigns

black teachers to black schools is not supported by

the record.

10. Teacher transfers are not granted in the

Detroit Public Schools unless they conform with the

balanced staff concept.

11. Between I960 and 1970, the Detroit Board

of Education reduced the percentage of schools without

black faculty from 36.3% to 1.2%, and of the four

schools currently without black faculty, three are

specialized trade schools where minority faculty

cannot easily be secured.

12. In 1968, of the 20 largest northern city

school districts, Detroit ranked fourth in the percentage

- 20 -

of schools m ing one or more black tea^^rs and third

in the percentage of schools having three or more

black teachers.

13. In 1970, the Board held open 240 positions

in schools with less than 25% black, rejecting white

applicants for these positions until qualified black

applicants could be found and assigned.

14. In recent years, the Board has come under

pressure from large segments of the black community to

assign male black administrators to predominantly black

schools to serve as male role models for students, but

*>

such assignments have been made only where consistent

with the balanced staff concept.

15. The numbers and percentages of black teachers

in Detroit increased from 2,275 and 21.6%, respectively,

in February, 1961; to 5fl06 and 41.6% respectively, in

October, 1970.

16. The number of schools by percent black of

staffs changed from October, 1963 to October, 1970 as

follows:

Number of schools without black teachers— de

creased from 41 to 4.

Number of schools with more than 0%, but less

than 10% black teachers— decreased from 58 to 8.

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers— decreased from 99 to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers—

increased from 72 to 124.

17. The number of schools by percent black of staffs

changed from October, 1969 to October, 1970, as follows:

Number of schools without black teachers— decreased

from 6 to 4.

- 21-

l

N er of schools with more t 0% but

10% black teachers-decreased from 41 to

1 ess

8.

than

Total number of schools with less than 10% black

teachers-decreased from 47 to 12.

Number of schools with 50% or more black teachers-

increased from 120 to 124

18. The total number of transfers necessary to

achieve a faculty racial quota in each school corresponding

to the system-wide ratio, and ignoring all other elements is,

as of 1970, 1,826.

19. If account is taken of other elements neces

sary to assure quality integrated education, including quali

fications to teach the subject area and grade level, balance

of experience, and balance of sex, and further account is

taken of the uneven distribution of black teachers by sub-_

ject taught and sex, the total number of transfers which

would be necessary to achieve a faculty racial quota in each

school corresponding to the system-wide ratio, if attainable

at all, would be infinitely greater.

20. Balancing of staff by qualifications for sub

ject and grade level, then by race, experience and sex, is

educationally desireable and important.

21. It is important for students to have a success

ful role model, especially black students in certain schools,

and at certain grade levels.

22. A quota of racial balance for faculty in each

school which is equivalent to the systenr>-wide ratio"and with

out more is educationally undesirable and arbitrary.

23. A severe teacher shortage in the 1950's and

1960's impeded integration-of-faculty opportunities.

- 22 -

24. Disadvantageous teaching conditions in

Detroit in the 1960's — salaries, pupil mobility

and transiency, class size, building conditions,

distance from teacher residence, shortage of teacher

substitutes, etc. — made teacher recruitment

and placement difficult.

25. The Board did not segregate faculty by

race, but rather attempted to fill vacancies with

certified and qualified teachers who would take offered

assignments.

26. Teacher seniority in the Detroit system,

although measured by system-wide service, has been

o

applied consistently to protect againstinvo]untary

transfers and "bumping" in given schools.

27. Involuntary transfers of teachers have

occurred only because of unsatisfactory ratings or be

cause of decrease of teacher services in a school, and

then only in accordance with balanced staff concept.

28. There is no evidence in the record that

Detroit teacher seniority rights had other than

equitable purpose or effect.

29. Substantial racial integration of staff

can be achieved, without disruption of seniority and

stable teaching relationships, by application of the

balanced staff concept to naturally occurring vacancies

and increases and reductions of teacher services.

30. The Detroit Board of Education has entered

into successive collective bargaining contracts with

- 23 -

the Detroit Federation of Teachers, which contracts

have included provisions promoting integration of

staff and students.

The Detroit School Board has, in many other

instances and in many other respects, undertaken to

lessen the impact of the forces of segregation and

attempted to advance the cause of integration. Per

haps the most obvious one was the adoption of the

April 7, Plan. Among other things, it has denied

the use of its facilities to groups which practice

racial discrimination; it does not permit the use of

its facilities for discriminatory apprentice training

o

programs; it has opposed state legislation which

would have the effect of segregating the district; it

has worked to place black students in craft positions

in industry and the building trades; it has brought

aboClt a substantial increase in the percentage of black

students in manufacturing and construction trade

apprenticeship classes; it became the first public

agency in Michigan to adopt and implement a policy re

quiring affirmative act of contractors with which it

deals to insure equal employment opportunities in their

work forces; it has been a leader in pioneering the

use of multiethnic instructional material, and in so

doing has had an impact on publishers specializing in

- 2k -

producing school texts and instructional materials; and

it has taken other noteworthy pioneering steps to ad

vance relations between the white and black races.

In conclusion, however, we find that both the

State of Michigan and the Detroit Board of Education

have committed acts which have been causal factors in

the segregated condition of the public schools of the

City of Detroit. As we assay the principles essential

to a finding of de jure segregation, as outlined in

rulings of the United States Supreme Court, they

*are:

1. The State, through its officers and agencies,

and usually, the school administration, must have taken

some action or actions with a purpose of segregation.

2. This action or these actions must have

created or aggravated segregation in the schools in

s

question.

3. A current condition of segregation exists.

We find these tests to have been met in this case. We

recognize that causation in the case before us is both

several and comparative. The principal causes un

deniably have been population movement and housing

patterns, but state and local governmental actions,

including school board actions, have played a substantial

role in promoting segregation. It is, the Court believes,

unfortunate that we cannot deal with public school

segregation on a no fault basis, for if racial segrega

tion in our public schools is an evil, then it should

- 25 -

make no difference whether we classify it de jure or

de facto. Our objective, logically, it seems to us,

should be to remedy a condition which we believe

needs correction. In the most realistic sense, if

fault or blame must be found it is that of the com

munity as a whole, including, of course, the black

components. We need not minimize the effect of the

actions of federal, state and local governmental

officers and agencies, and the actions of loaning

institutions and real estate firms, in the establish-

ment and maintenance of segregated residential patterns

which lead to school segregation - to observe that

o

blacks, like ethnic groups in the past, have tended to

separate from the larger group and associate together.

The ghetto is at once both a place of confinement and

a refuge. There is enough blame for everyone to

shar̂ e.

- 26 -

CONCLUSIONS OF L A W ®

1. This Court has jurisdiction of the par-

ties and the subject matter of this action under 28

U.S.C. 1331(a), 1343(3) and (4), 2201 and 2202; 43

U.S.C. 1983, 1988, and 2000d.

2. In considering the evidence and in apply

ing legal standards it is not necessary that the Court

find that the policies and practices, which it has found

to be discriminatory, have as their motivating forces any

evil*intent or motive. Keyes v. Sch. Dist. #1. Denver.

383 F. Supp. 279. Motive, ill will and bad faith have

long ago been rejected as a requirement to invoke the

protection of the Fourteenth Amendment against racial dis

crimination. Sims v. Georgia. 389 U.S. 404,407-8.

3. School districts are accountable for the

natural probable and foreseeable consequences of their

policies and practices, and where racially identifiable

schools are the result of such policies, the school auth

orities bear the burden of showing that such policies are

based on educationally required, non-racial considerations.

Keyes u Sch. Dist.. supra, and Davis v. Sch. Dist of

Pontiac. 309 F. Supp. 734, and 443 F. 2d 573

4. In determining whether a constitutional vio

lation has occurred, proof that a pattern of racially se-

- 27-

gregated schools has existed for a considerable period of

time amounts to a showing of racia] classification by the

state and its agencies, which must be justified by clear

and convincing evidence. State of Alabama v. U.S., 304

F. 2d 583.

5. The Board's practice of shaping school atten

dance zones on north—south rather than an east—west ori

entation, with the result that zone boundaries conformed

to racial residential dividing lines, violated the Four-* ■*

teenth Amendment. Northcross v. Bd. of Ed. Memphis, 333

F. 2d 661.

6. Pupil racial segregation in the Detroit Public

School system and the residential racial segregation result

ing primarily from public and private racial discrimination

are interdependent phenomena. The affirmative obligation of

the defendant Board has been and is to adopt and implement

pupil assignment practices and policies that compensate for

and avoid incorporation into the school system and effects

of residential racial segregation. The Board's building

upon housing segregation violates the Fourteenth Amendment.

See, Davis v. Sch. Dist. of Pontiac, Supra, and authorities

there noted.

7 . The Board's policy of selective optional atten-

-28-

dance zones, to the extent that it facilitated the sepa

ration of pupils on the basis of race, was in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Hobson v. Hansen. 269 F.

Supp. 401, aff1d sub nom., Smuck v. Hobson, k O S F. 2d

175.

8. The practice of the Board of transporting

black students from overcrowded black schools to other

identifiably black schools, while passing closer identi-

fiably white schools, which could have accepted these pu

pils, amounted to an act of segregation by the school auth

orities. Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Ed., 311 F. Supp.

501.

9. The manner in which the Board formulated and

modified attendance zones for elementary schools had the

natural and predictable effect of perpetuating racial se

gregation of students. Such conduct is an act of de jure

discrimination in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

U.S. v. School District 151 , 286 F. Supp. 786; Brewer v.

Citv of Norfolk. 397 F. 2d 37.

10. A school board may not, consistent with the

Fourteenth Amendment, maintain segregated elementary schools

**or "permit educational choices to be influenced by community

sentiment or the wishes of a majority of voters. Cooper v.

- 29-

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 12-13, 15-16.

"A citizen’s constitutional rights can hardly

be infringed simply because a majority of the

people choose that it be.” Lucas v. A4th Gen»1

Assembly of Colorado, 377 U.S. 713, 736-737.

11. Under the Constitution of the United States

and the constitution and laws of the State of Michigan, the

responsibility for providing educational opportunity to all

children on constitutional terms is ultimately that of the

state. Turner v. Warren*County Board of Education, 313 F.

Supp. 380; Art. VIII, §§ 1 and 2, Mich. Constitution;

Dasiewicz v. Bd. of Ed. of the City of Detroit, 3 N.°W. 2d

71.

12. That a state’s form of government may dele

gate the power of daily administration of public schools to

officials with less than state-wide jurisdiction does not dis

pel the obligation of those who have broader control to use

the authority they have consistently with the constitution.

In such instances the constitutional obligation toward the

individual school children is a shared one. Bradley v. Sch.

Bd., City of Richmond, 51 F.R.D. 139, 1A-3.

13. Leadership and general supervision over all

public education is vested in the State Board of Education.

Art. VIII, § 3, Mich. Constitution of 1963. The duties of

- 30 -

the State Board and superintendent include, but are not

limited to specifying the number of hours necessary to

constitute a school day; approval until 1962 of school

sites, approval of school construction plans; accredi

tation of schools, approval of loans based on state aid

funds; review of suspensions and explusions of indivi

dual students for misconduct [Op. Atty. Gen., July 7,

1970* No. 4705]; authority over transportation routes

and disbursement of transportation funds; teacher cert

ification and the like M.S.A. 15. 1023(1). State law

provides review procedures from actions of local or in-

/

termediate districts (See M.S.A. 15.3442), with auth

ority in the State Board to ratify, reject, amend or modify

the actions of these inferior state agencies. See M.S.A.

15.3467; 15.1919(61); 15.1919(68b); 15.2299(1); 15.1961;

* L15*3402; Bridqehampton School District No. Fractional of

Carsonville, Mich, v. Supt. of Public Instruction, 323

Mich 615. In general, the state superintendent is given

the duty "[t]o do all things necessary to promote the

welfare of the public schools and public educational in

structions and provide proper educational facilities for

.the youth of the state." M.S.A. 15*3252. See also M.S.A.

15.2299(57), providing in certain instances for reor

ganization of school districts.

- 31-

\ k . State officials, including all of the de

fendants, are charged under the Michigan constitution

with the duty of providing pupils an education without

discrimination with respect to race. Art. VIII, § 2,

Mich. Constitution of 1963. Art. I, § 2, of the consti

tution provides:

"No person shall be denied the equal protection

of the laws; nor shall any person be denied

the enjoyment of his civil or political rights

or be discriminated against in the exercise

thereof because of religion, race, color or

national origin. The legislature shall im

plement this section by appropriate legisla

tion,"

15. The State Department of Education has recently

established an Equal Educational Opportunities section hav

ing responsibility to identify racially imbalanced school

v

districts and develop desegregation plans. M.S.A. 15*3355

provides that no school or department shall be kept for any

person or persons on account of race or color.

16. The state further provides special funds to

local districts for compensatory education which are admin

istered on a per school basis under direct review of the

State Board. All other state aid is subject to fiscal re

view arid accounting by the state. M.S.A. 15»1919^ See

also M.S.A. 1919(68b), providing for special supplements

to merged districts " for the purpose of bringing about

- 32-

uniformity of educational opportunity for all pupils of

the district." The general consolidation law for M.S.A.

15-3401 authorizes annexation for even noncontigous

school districts upon approval of the superintendent of

public instruction and electors, as provided by law. Op.

Atty. Gen., Feb. 5, 1964, No. 4193* Consolidation with

respect to so-called "first class" districts, i.e.,

Detroit, is generally treated as an annexation with the

first class district beifig the surviving entity. The law

provides procedures covering all necessary considerations.

M.S.A. 15-3184, 15.3186.

17. Where a pattern of violation of constitutional

rights is established the affirmative obligation under the

Fourteenth Amendment is imposed on not only individual school

districts, but upon the State defendants in this case. Cooper

v. Aaron, 358, U.S. 1: Griffin v. County School Board

of Prince Edward County. 337 U.S. 218; U.S. v. State of

Georgia, Civ. No. 12972 (N.D. Ga., December 17> 1970),

rev1d on other grounds, 428 F. 2d 377; Godwin v. Johnston

County Board of Education, 301 F. Supp. 1337; Lee v._ Macon

County Board of Education, 267 F. Supp. 458 (M.D. Ala.),

aff1d sub nom., Wallace v. U.S., 389 U.S. 215; Franklin v.

Quitman County Board of Education, 288 F. Supp. 509;

- 33 -

Smith v. North Carolina State Board of Education, No.l5>

072 (4th Cir., June 14, 1971).

The foregoing constitutes our findings of fact

and conclusions of law on the issue of segregation in the

public schools of the City of Detroit.

Having found a de jure segregated public school

system in operation in the City of Detroit, our first step,

in 'considering what judicial remedial steps must be taken,

is the consideration of intervening parent defendants' mo

tion to add as parties defendant a great number of Michigan

school districts located out county in Wayne County, and in

Macomb and Oakland Counties, on the principal premise or

ground that effective relief cannot be achieved or ordered

in their absence. Plaintiffs have opposed the motion to

join the additional school districts, arguing that the pre

sence of the State defendants is sufficient and all that

is required, even if, in shaping a remedy, the affairs of

these other districts will be affected.

In considering the motion to add the listed school

districts we pause to note that the proposed action has to

do with relief. Having determined that the circumstances of

the case require judicial intervention and equitable relief,

it would be improper for us to act on this motion until

the other parties to the the action have had an opportunity

to submit their proposals for desegregation. Accordingly,

we shall not rule on the motion to add parties at this

time. Considered as a plan for desegregation the motion is

lacking in specifity and is framed in the broadest general

terms. The moving party may wish to amend its proposal and

resubmit it as a comprehensive plan of desegregation.

In order that the further proceedings in this

cause may be conducted on a reasonable time schedule, and

because the views of counsel respecting further proceed-

o

ings cannot but be of assistance to them and to the Court,

this cause will be set down for pre-trial conference on the

matter of relief. The conference will be held in our Court

room in the City of Detroit at ten o'clock in the morning,

October A, 1971*

DATED: September 27, 1971.

Stephen J. Roth

United States District Judge

- 35-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

)RONALD BRADLEY and RICHARD BRADLEY

et al.# )

Plaintiffs, )

v ) No. 35257

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, Governor of )

the Stats of Michigan, et al.,

Defendants,

>DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION )

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO, et al.,

)

Intervening Defendants.

>

Proceedings had in the above-cmtitled matter

before Honorable Stephen J. Roth, United States District Judge,

at Detroit, Michigan on Monday, October 4, 1971.

APPEARANCES s

LOUIS R. LUCAS, Esq.

WILLIAM E. CALDWELL, Esq.

(Ra tiier, Sugar son & Lucas,

525 Commerce Title Building,

Memphis, Tennessee)

2. WINTHER KcCROOM, Esq.

PAUL R. DIHOND, Esq.,

Appearing on behalf of Plaintiffs.

FRANK J . KELLEY, Attorney General,

EUGENE KRASICKY, Asst. Attorney General,

(525 W. Ottawa Street, Lein sing, Michigan)

Appearing on behalf of Defendant Hilliken

APPENDIX P

APPEARANCES a (Continued)

HILLER, CANFIELD, PADDOCK £ STONE,

GEORGE B. BUSHNELL, JR. , Esq.

CARL H. von EHDE, Esq.

GREGORY L. CURTRER, Esq.,

BHKETT E. EAGAN, JR., Esq.

(2500 Detroit Bank & Trust Building,

Detroit, Michigan)

Appearing on behalf of Detroit Board of

Education.

ROTE'S, MARS TOM, KAZEY, SAC US k O'CONNELL,

«UNN & FREID, P.C.,

THEODORE SACHS, Esq.,

(10DC Farmer Street, Detroit, Michigan)

Appearing on behalf of Intervenors Detroit

Federal of Teachers.

FENTON, KEBEHIANDER, TRACY, DODGE g HARRIS,

ALEXANDER B. RITCHIE, Esq.

{2555 Guardian Building, Detroit, Michigan)

Appearing on behalf of Interveners

D. Magdovski, et al.,

Donald E. Miller

Cout Reporter

265 Federal Building

Detroit, Michigan, 43226

3

Detroit, Michigan

Monday, Ocfcober 4, 1971

10:00 o»clock, A. H*

Killiken.

this morning?

THE CLERK: Case No. 35257. Bradley versus

THE COURT: Are all the parties represented

HR. LUCAS: Yes.

THE COURT: I take it they are.

o

As I indicated at the close of my opinion

recently rendered, I thought it would be advisable for me to

get together with counsel on this occasion so that we might

chart our course from here on in these proceedings.

The Court has made its determination of things

as they are, or as it found things in the public school system

of the City of Detroit. Our concern now— -to take a thought

from Aristotle— is of things as they might be, or ought to be.

Before ordering the local and state school

authorities to present desegregation plans, the Court thought

it best to call this conference so that it might have the bene

fit of your views with respect to a timetable for further

proceedings, and so that you sight have the benefit of some of

the thoughts of the Court.

As the Court indicated during the course of

the taking of proofs, it entertains serious reservations about

a plan of integration, which encompasses no more than the

public schools of the City of Detroit. It appears to us that

perhaps only a plan which embraces all or some of the greater

Detroit metropolitan area can hope to succeed in giving our

children the kind of education they are entitled to constitu

tionally* And wo note here that the metropolitan area is like

a giant jig-saw puzzle, with the school districts cut into

irregular pieces, but with the picture quite plainly that of

racial segregation.

We need not recite the many serious problems

such a plan entails; suffice it to say that a plan of such

dimensions can hardly be conceived in a day, to say nothing

of the time it will require for implementaiton• A large

metropolitan area such as we have in our case can not be made

the subject of instant integration. We must bear in mind that

the task we are called upon to perform is a social one, which

society has been unable to accomplish* In reality, our courts

are called upon, in these school cases, to attain a social goal

through the educational system, by using law as a lever.

If a metropolitan plan is our best answer to

the problem, its formulation and implementation with require

both time and patience* As Senior Circuit Judge 0 * Sullivan

said in the Knoxville, Tennessee school case:

5

•Thehope, or dream, that one day we

will have become a people without motivations

born of our differing racial beginnings will

have a better chance of fulfillment if patience

accompanies our endeavors. *

I would sum up our endeavors in developing

a metropolitan plan as an embarkation on an uncharted course

in strange waters in an effort to rescue disadvantaged children*

•*»

It behooves us to take proper soundings and proceed with care*

To use the vernacular "Plight on!* but steady as we go.

My comments respecting a metropolitan plan

should not be understood to mean that there should be any

pause in Detroit Board * s efforts to affirmatively desegregate

its schools. The Court envisions no real conflict between

early desegregation or integration of its schools and the

possible adoption later of a metropolitan plan.

Earlier in this case the Court acceded to

the wish of the Board to adopt the so-called Magnet Plan. We

do not presently have before us enough information or evidence

on the question of its worth car value in terms of experience.

In this respect the Court wishes to be better informed.

If that plan is not delivering on its promise

to provide an improved integrated quality education it should

be abandoned, and the Board should consider putting before

6

the Court an tiD-dated April 7 Plan, or such other plan as, in

its judgment, will most effectively accomplish desegregation

in its schools. If the Magnet Plan is proving itself then the

Board might well consider whether features of the April 7 Plan,

for example, the change to an east-west, rather than north-south

orientation of attendance zones, can be incorporated in it in

the interest of advancing integration.

Hhat we have said are all generalities. They

have to do with possible courses of action. My remarks,

however, are not intended as a limitation on the Board or on

the state authorities in discharging their duties to move a3

rapidly as possible toward the goal of desegregation.

I want to make it plain I have no preconceived

notions about the solutions or remedies which will be required

here. Of course, the primary and basic and fundamental

responsibility is that of the school authorities. As Chief

Justice Burger said in the recent case of Davis v Board of

School Commissioners:

*-- school authorities should sake

every effort to achieve the greatest possible

degree of actual desegregation, taking into

account the practicalities of the situation.3*

Because these cases arise under different

local conditions and involve a variety of local problems their

7

remedies likewise will require attention to the specific case.

It is for that reason that the Court has repeatedly said,

the Supreme Court, that each case mu3t be judged by itself in

its own jvaculiar facts.

As early as Brown II the court had this to say?

“Full implementation of these

constitutional principles may require solution of

varied local school problems, School authorities

have the primary responsibility for elucidating,

assessing, and solving these problems; courts

will have to consider whether the action of

school authorities constitutes good faith

implementation of the governing constitutional

principles.

*In fashioning and effectuating

the decrees, the courts will be guided by equitable

principles...... At stake is tha personal interest

of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis•

Z might say in that regard, as you lawyers

know the Supreme Court took a little over a year to implement

Brown I and Brown II. So they themselves, with better minds

than mine and to the number of nine, had difficulty in resolving

the problems that those four cases presented,

I would like to hear from counsel with respect

to a timetable for the formulation and presentation of a plan

of desegregationt first by the Board of the City of Detroit

and then by the state officials.

Hr. Bushnc11.

MR. BUSEiSELL* If the Court please, the

Court * s comments this morning, of course, have come without

forewarning, though perhaps there has been foreshadowing•

hs a4 consequence I find it somewhat difficult on behalf of

defendant Board to respond specifically to the Court*s inquiry.

I would suggest, however, as your Honor has already suggested,

the problems inherent in implementing the Court’s findings are

extraordinarily complex in a district with the racial makeup

of the Detroit district and of the educational inequities that

are present in such horrendous quantity in the Detroit district.

At one and the same time, as I understand the

Court’s last comments there is direction to the Detroit Board

to consider not only continued integration of its own system

but also to consider some program or suggested pi*** to the

Court whereby the district is either enlarged or parts or all

of other districts are included in the implementation of the

plan.

I respectfully suggest that it would be naive

to e ̂ >ect that wo can have any such plan in either respect for

implementation before the end of this current school year.

9

I assure the Court on behalf of the Detroit Board of Education

we shall continue our program of active integration of the

school district of Detroit. Some parts of that program may

perhaps be enhanced between now and the end of the current

semester for implementation February 1.

I, frankly, do not know and I will have to

consult with the Board and with staff, I think we should be

expected to report back to your Honor within a reasonable time

as to what may or may not be accomplished February 1, intra-

district. I think further that we should be reasonably

expected to report back to your Honor on an arbitrary date X

pick and I ask not to be hold to this, by either the Court or

the public here represented through the media, shortly after

the first of the year as to plans for implementation for the

school year beginning September, 1972.

As the Court knows after almost four months

of trial the lag time in between staffing, planning and imple

mentation is not insignificant and the store complex the problem

or the execution of the problem becomes the more necessity there

be that it be well thought out, well executed and above all

that the community be informed at every step of the way.