Local 638... Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers' International Association, v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Respondents' Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

July 19, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Local 638... Local 28 of the Sheet Metal Workers' International Association, v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Respondents' Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1985. 70ae3e67-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/20107c66-7bfc-4f82-bf0b-f4fad262ac6d/local-638-local-28-of-the-sheet-metal-workers-international-association-v-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-respondents-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

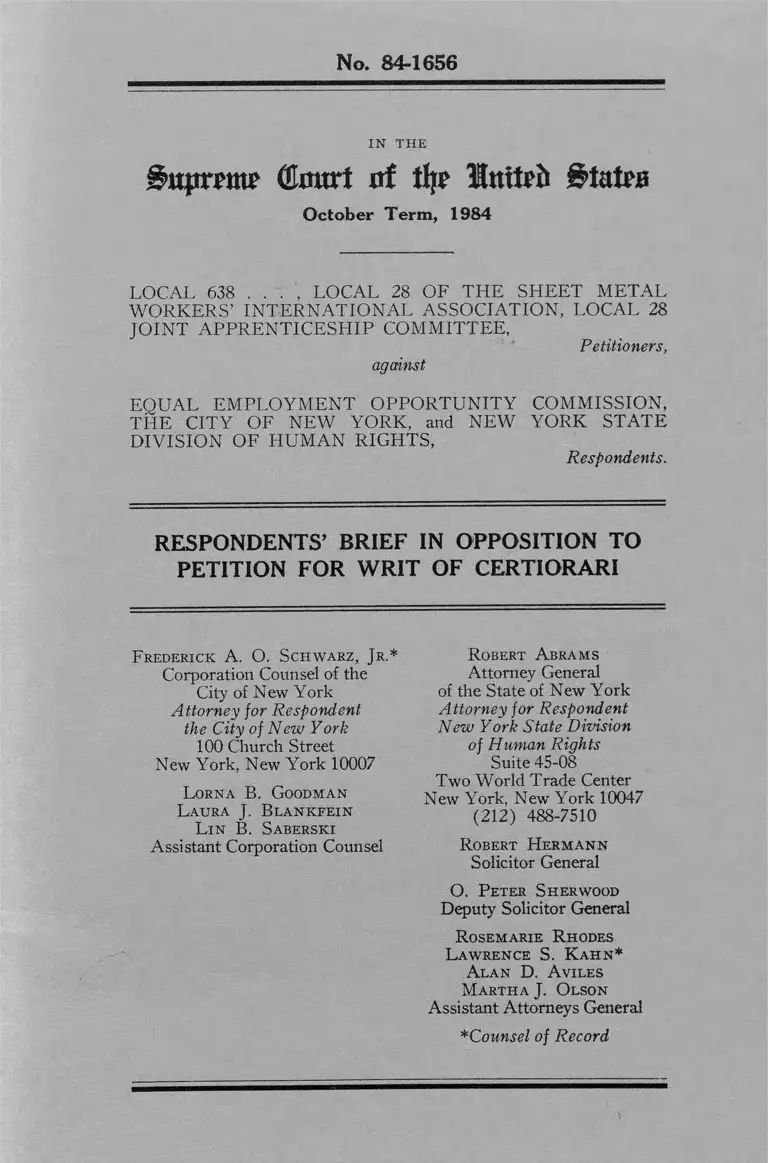

No. 84-1656

I N T H E

(Emtrt of % Inttri* §tatra

October Term, 1984

LO CAL 638 LO CAL 28 OF TH E SHEET M E TAL

W O R K E R S’ IN TE R N A TIO N A L ASSO C IA TIO N , LO CAL 28

JOIN T A PPRE N TIC E SH IP COM M ITTEE,

Petitioners,

against

EQ U AL E M PLO Y M E N T O PPO R TU N ITY COM M ISSION,

TH E CITY OF N EW Y O R K , and N EW Y O R K STA TE

D IV ISIO N OF H U M AN RIGH TS,

Respondents.

RESPONDENTS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI

F rederick A. O. Schwarz, Jr.*

Corporation Counsel of the

City of New York

Attorney for Respondent

the City of New York

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

Lorna B. Goodman

Laura J. Blankfein

L in B. Saberski

Assistant Corporation Counsel

O. Peter Sherwood

Deputy Solicitor General

R osemarie R hodes

L awrence S. K ah n*

A lan D. A viles

Martha J. O lson

Assistant Attorneys General

*Counsel of Record

R obert A brams

Attorney General

of the State of New York

Attorney for Respondent

New York State Division

of Human Rights

Suite 45-08

Two World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

(212) 488-7510

R obert H ermann

Solicitor General

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S

P A G E

Table of Authorities .......................................................... 11

Preliminary Statement .................................................... 1

A. Litigation History Prior to the Contempt

Proceedings ........................................................ 2

B. The Contempt Proceedings ............................ 5

C. The Fund Order ................................................ 9

I). AAAPO .............................................................. 9

E. The Appeal to the Second Circuit....................... 10

Argument

I. The Petition Is Untimely As To Virtually All

Of The Questions Presented ............................... 12

II. The Contempt Remedy Affirmed Below Is

Firmly Rooted In Well-Settled Principles Of

Contempt L a w ......................................................... 16

III. The Petition Should Be Denied Because The

Court Below Correctly Concluded That This

Court’s Holding In Firefighters v. Stotts Was

Not Controlling And Because This Case

Provides An Inappropriate Vehicle For Eval

uating Race-Conscious Remedies Under Title

V II ............................................................................ 20

IV. The Remedial Orders At Issue, Narrowly

Tailored To Further The Compelling Interest

In Eradicating Proven Systemic Discrimina

tion, Fully Comport With The Governing

Principles Of Equal Protection 26 •

• oqConclusion .................... ....................................................

TABLE O F A U T H O R IT IE S

Cases:

PAGE

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) ... 25

Association Against Discrimination in Employment,

Inc. v. City of Bridgeport, 647 F.2d 256 (2d Cir.

1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 988 (1982).................. 23

Boeing Co. v. Van G-emert, 444 U.S. 472 (1980) .......... 14

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F.2d

1017 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910

(1975) ......................................................................... 23

Chisolm v. United States Postal Service, 665 F.2d 482

(4th Cir. 1981) ............................................................ 23

Deveraux v. Geary, 596 F. Supp. 1481 (D. Mass.

1984), aff’d ,------ F .2d -------- (1st Cir. 1985) (No.

84-2004) ....................................................................... 21

Diaz v. American Telephone & Telegraph, 752 F.2d

1356 (9th Cir. 1985).................................................... 22

Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, ------ U.S.

------ , 104 S. Ct. 2576 (1984) .................... 20, 21, 22, 23, 24

Florida Steel Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 648 F.2d 233 (5th

Cir. 1981) .................................................................... 15

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976) 25

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) .................. 26, 27

Gary W. v. State of Louisiana, 601 F.2d 240 (5th Cir.

1979) ........................................................................... 15

Gompers v. Buck’s Stove & Range Co., 221 U.S. 418

(19H) ..........................................................................16,19

Halderman v. Pennhurst State School & Hospital, 673

F.2d 628 (3rd Cir. 1982) (en banc), cert, denied,

------ U .S .------- -, 104 S. Ct. 1315 (1984) 15

I l l

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S.

299 (1977) ................................................................... 12,13

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678 (1978) ............................ 16, 24

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ...................................... 25

James v. Stockliam Valves & Fittings Co., 559 F.2d

310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034

(1978) ......................................................................... 23

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 748 F.2d 1308 (9th

Cir. 1984) ................................................................... 22

Kromnick v. School District, 739 F.2d 894 (3d Cir.

1984), cert, denied,------ U .S .------- , 105 S. Ct. 782

(1985) ......................................................................... 23

Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56 (1948) ................................ 15

McComb v. Jacksonville Paper Co., 336 U.S. 187

(1949) ....................................................................16,19,24

McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39 (1971) 27

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ................................................................... 25

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 544 F.2d 837 (5th Cir.),

cert, dismissed, 434 U.S. 801 (1977) ...................... 14

National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Board of

Regents,------ U .S.------- , 104 S. Ct. 2948 (1984) .....12,19

PAGE

New York State Association for Retarded Children v.

Carey, 706 F.2d 956 (2d Cir. 1982), cert, denied,

104 S. Ct. 277 (1983) ............................................... 14

Oriel v. Russell, 278 U.S. 358 (1929) 15

Palmer v. District Board of Trustees, 748 F.2d 595

(11th Cir. 1984) ......................................................... 22

PAGE

Parker v. Illinois, 333 U.S. 571 (1948) ............................ 12,13

Pasadena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427

U.S. 424 (1976) ................................................. ........ 14

Penfield Co. v. Securities & Exchange Commission,

330 U.S. 585 (1947) .................................................... 18

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438

U.S. 265 (1978) ......' .................................................. 25,26

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) ............................ 12,19

Ruiz v. Estelle, 679 F.2d 1115 (5th Cir. 1982), cert.

denied, 460 U.S. 1042 (1983) .................................... 14,15

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966) ..... 27

State Commission For Human Rights v. Farrell, 52

Mise. 2d 936 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.), aff’d, 27 A.D.2d

327 (1st Dept.), aff’d, 19 N.Y.2d 974 (1967) ......... 2

State Commission For Human Rights v. Farrell, 47

Misc. 2d 799 (Sup. Ct. N.Y) Co. 1965) .................... 2

State Commission For Human Rights v. Farrell, 47

Misc. 2d 244 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1965) .................... 2

State Commission For Human Rights v. Farrell, 43

Misc. 2d 958 (Sup. Ct. N .Y . Co. 1964) .................... 2

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ....................................................... 26,27

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C. Cir. 1982) .... 23

Turner v. Orr, 759 F.2d 817 (11th Cir. 1985) .............. 22

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

(1977) ' .......................... 26

United States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354 (7th

Cir. 1981) ................................................................... 23

United States v. International Brotherhood of Elec

trical Workers, Local 38, 428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970) ............................ 23

United States v. International Union of Elevator Con

structors, Local 5, 538 F.2d 1012 (3d Cir. 1976) 23

V

PAGE

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544

(9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971) ........... 23

United States v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 625 F.

2d 918 (10th Cir. 1979) ............................................ 23

United States v. Montgomery County Board of Edu

cation, 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ........................................ 27

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354

(8th Cir. 1973) ........................................................... 23

United States v. United Mine Workers of America,

330 U.S. 258 (1947) .................................................. 16

Van A ken v. Young, 750 F,2d 43 (6th Cir. 1984) ........ 22

Vanguards of Cleveland v. City of Cleveland, 753 F.

2d 479 (6th Cir. 1985) ................................................ 22

Wirtz v. Local 153, Glass Bottle Blowers Association,

389 U.S. 463 (1968) ..................................................

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 746 F.2d

1152 (6th Cir. 1984), cert, granted, 105 S. Ct. 2015

(1985) (No. 1340, 1984 Term) ................................

Statutes:

Title V II of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000c ct seq........................................................... passim

Section 706(g) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) .....21, 24

Section 703(h) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h) . .. 21

28 U.S.C. § 2101 ................................................................. 12,13

14

23

Rules:

Sup. Ct. R. 17.1 ............................................................. 16

Sup. Ct. R. 20 .................................................................12,13

No. 844656

IN T H E

Ĵ upmttP (£mu! ni tty Imtpft ^tatm

October Term, 1984

Local 638 . . . , Local 28 of the Sheet M etal W orkers’ I nter

national A ssociation, L ocal 28 Joint A pprenticeship Com

mittee,

Petitioners,

against

Equal E mployment O pportunity Commission, T he City of

New Y ork, and New Y ork State D ivision of H uman R ights,

Respondents.

RESPONDENTS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Preliminary Statement

Petitioners are before this Court having been found

guilty of a long and ignominious history of intentional

racial discrimination and of repeated defiance of judicially

supervised efforts to effect compliance with local, state and

federal fair employment laws. For over twenty years, in

more than twenty-five orders or opinions, the state and

federal courts have sought to force these petitioners into

2

compliance with established law.* See, e.g., Pet. 2, n.2;

A-i-ii.** The Second Circuit now has rejected, for the third

time, petitioners’ efforts to evade compliance with federal

court orders entered to redress their discriminatory prac

tices, and has affirmed the lower court ’s judgments holding

defendants in contempt of these remedial orders. Under

the guise of appealing the contempt judgments, petitioners

come to this Court principally to obtain review of the under

lying remedial court orders, for which the time to seek

review has long since expired. Because this petition is

untimely as to virtually all of the rulings being challenged

and because the rulings below are plainly correct, the

petition should be denied.

A. Litigation History Prior to the Contempt Proceedings

In 1971, the United States Department of Justice, pur

suant to Title VII of the Civil Bights Act o f 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq., filed suit against petitioners to enjoin a

pattern and practice of discrimination against black and

Spanish surnamed individuals (“ non-whites” ) who sought

* Petitioners were first found to have intentionally discriminated

against minorities in 1964, in a proceeding brought under the New

York Human Rights Law. State Comm’n For Human Rights v.

Farrell, 43 Misc. 2d 958 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1964). A-411. There

after, the trial judge repeatedly castigated Local 28 for foot-dragging

in its integration efforts and found it necessary to issue several orders

enforcing the original judgment. State Comm’n For Human Rights

v. Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d 244 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co. 1965) ; State Comm’n

For Human Rights v. Farrell, 47 Misc. 2d 799 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.

1965) ; State Comm’n For Human Rights v. Farrell, 52 Misc. 2d 936

(Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.), aff’d, 27 A.D.2d 327 (1st Dept.), aff’d, 19

N.Y.2d 974 (1967). Local 28 continued to resist court orders follow

ing commencement in 1971 of the federal action. See, e.g., A-220,

** References to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari are cited as

“ Pet. -------” . References to the Appendix to the Petition are cited

as “ A --------- ” . References to the Respondents’ Brief in Opposition

to the Petition for Writ of Certiorari are cited as “ Opp. -------” .

3

membership in Local 28 and training and job opportunities

in the sheet metal trade in New York City. Following a

trial in 1975, the district court found that petitioners had

intentionally discriminated against non-whites by admin

istering discriminatory entrance examinations; excluding

persons who lacked a high school diploma; offering cram

courses to the sons and nephews of union members but not

to minority applicants; refusing to accept blowpipe sheet

metal workers for membership because most such workers

were non-white; consistently discriminating in favor of

white applicants seeking to transfer into Local 28 from

sister locals; refusing to administer journeyman examina

tions out of a fear that minority candidates would do well,

and instead issuing work permits to non-members on a

discriminatory basis; and failing to organize non-union

sheet metal shops owned by or employing non-whites.

A-330-50.*

Based upon these findings, the court entered an Order

and Judgment ( “ O&J” ) that enjoined petitioners from

all future violations of Title V II and ordered petitioners to

achieve, by July 1, 1981, a remedial end-goal of 29% non

white membership in Local 28. A-305, 354. This goal was

based on the relevant non-white labor pool in New York

City. A-300, 305, 353-54. The court also ordered petitioners

to eliminate the diploma requirement for the apprenticeship

program, to offer non-discriminatory entrance exams for

journeymen and apprentices, and to allow transfers and

issue temporary work permits on a. non-discriminatory

* The court further noted that, during the pendency of both the

state and federal proceedings, Local 28 and the JAC had repeatedly

flouted the state court’s mandate to “ create ‘a truly non-discrimma-

tory union,’ ” and had obeyed the federal court’s interim orders only

under threat of contempt citations. A-352.

4

basis. A-354-56, 308-10, 303. Petitioners were required

to engage in extensive recruitment and publicity campaigns

in minority neighborhoods in order to dispel Local 28’s

reputation for discrimination and to ensure a broad appli

cant pool for these tests and transfers, A-355, 312, and

to maintain records regarding applications, requests for

transfer, inquiries about permit slips and hiring. A-355,

310-11. The court appointed an Administrator to super

vise compliance with the court’s decree. A-355, 305-07.

On appeal, the Second Circuit affirmed, noting that there

was ample evidence that petitioners “ consistently and egre-

giously violated Title V II.” A-212. Indeed, petitioners

“ [did] not even make a serious effort to contest the finding

of Title VII violations ” in this initial appeal. A-215. The

court upheld the 29% goal as a temporary remedy, dis

tinguishing it from ‘ ‘ a quota used to bump incumbents or

hinder promotion of present members of the work force.”

A-221, 222. It also upheld the requirement that entrance

examinations be validated and ruled that the testing sched

ules and recruitment requirements imposed by the district

court were appropriate exercises of the district court’s

discretion. A-222. The court modified the relief by elimi

nating any provision that “ might be interpreted to permit

white-minority ratios for the apprenticeship program after

the adoption of valid, job-related entrance tests.” A-225.

It concluded that the appointment of an administrator with

broad powers was “ clearly appropriate,” given petitioners’

failure to change their membership practices pursuant to

the earlier New York court orders and the district court’s

rulings in this case. A-220.

Petitioners did not seek review in this Court from the

Second Circuit’s judgment, which finally determined all

issues in the action.

On January 19, 1977, following the Second Circuit’s

affirmance, the district court issued a revised affirmative

action program and order (“ RAAPO” ). A-182. Among

other things, RAAPO granted petitioners an additional

year in which to meet the 29% membership goal. The court

ordered petitioners to insure that regular and substantial

progress was made every year in admitting non-whites.

Additional modifications were made to insure that, during

a time of widespread unemployment in the industry, ap

prentices shared equitably in available employment oppor

tunities in the industry. A-183-84. The court therefore

ordered the JAC to take all reasonable steps to insure that

apprentices receive adequate employment opportunities and

to indenture two classes of apprentices each year, the size

of each class to be determined by the JAC, subject to review

by the Administrator. A-192-93.

Petitioners appealed six provisions of RAAPO, includ

ing the apprenticeship indenture requirement and the 29%

goal, but the Second Circuit affirmed. A-160, 165-66. Once

again neither Local 28 nor the JAC sought certiorari from

this Court.

B. The Contempt Proceedings

In 1982, it became clear to the respondents that Local 28

would not achieve the 29% goal by the July 1, 1982 date

required under the O&J. Because this result was a conse

quence of Local 28’s failure to comply with several sub-

6

staixtive provisions of the O&J and RAAPO, respondents

moved for an order holding petitioners in contempt. Peti

tioners cross-moved for an order terminating the O&J and

RAAPO.

Following a hearing, the district court found that peti

tioners had “ impeded the entry of non-whites into Local 28

in contravention of the prior orders of this court. ’ ’ A-149,

150.# Judge Werker held petitioners in contempt for vio

lating the O&J and RAAPO by a) underutilizing the ap

prentice program to the detriment of non-whites; b) failing

to undertake, as required by RAAPO, a general publicity

campaign intended to dispel petitioners’ reputation for dis

crimination ; c) failing to maintain and submit records and

reports; d) issuing work permits without prior authoriza

tion of the Administrator; and e) entering into an agree

ment amending their collective bargaining contract by

adding a provision that discriminates against Local 28’s

non-white members by protecting members aged fifty-two

or over during periods of unemployment (the “ older work

ers’ provision” ). The cumulative effect of these contemp

tuous acts, the district court ruled, was that petitioners

failed even to approach the 29% goal.* ** A-155-56.

* Petitioners’ assertion, at Pet. 7, that they had achieved a non

white membership in Local 28 of 14.9% by April 1977, was rejected

by both the district court and the Second Circuit. A-9. Petitioners’

own April 1982 census showed its non-white membership to be only

10.8%. Similarly, petitioners’ statement that 45% of their apprentice

classes are made up of non-whites, Pet. 7, is misleading in that only

since January 1981 have petitioners indentured apprenticeship classes

consisting of 45% non-whites. A-37.

** Although Local 28’s total non-white journeymen and appren

tice membership was then only 10.8%, more than 18 percentage points

below the ultimate goal petitioners had been ordered to reach by July

1, 1982, the district court did not base its finding of contempt upon

petitioners’ failure to reach the goal. A-155.

7

The primary basis for the contempt holding was the dis

trict court’s finding that petitioners had deliberately under

utilized the apprenticeship program in order to limit non

white membership and employment opportunities. This

finding rested on evidence that petitioners trained substan

tially fewer apprentices after entry of the O&J than prior

to its issuance. The court found that the underutilization

of the apprenticeship program was not the result of a down

turn in the economy. To the contrary, the average number

of hours and weeks worked per year by its journeymen

members steadily increased from 1975 to 1981. A-16, 151.

In fact, by 1981, employment opportunities so exceeded the

available supply of Local 28 journeymen that Local 28 was

compelled to issue an extraordinary number of work per

mits to non-member sheet metal workers, most of whom

were white. A-16. Thus, the court concluded that during

the years after entry of the O&J, Local 28 deliberately

shifted employment opportunities from apprentices to its

predominantly white, incumbent journeymen.* The extent

of that shift was demonstrated by the increase in the ratio

of journeymen to apprentices from 7:1 before the O&J was

entered to 18:1 by 1981, well above the industry standard

of 4:1. A-16.

The court’s finding that petitioners were also in con

tempt for issuing permits without the Administrator’s ap

proval was based upon evidence that Local 28 issued thir

teen unauthorized permits between March and June 1981.

Of the thirteen unauthorized permit men, only one was non

white. These contemptuous acts were particularly signifi

* Petitioners erroneously assert, at Pet. 7, that the Administrator

approved the size of each of more than 60 classes of apprentices. What

petitioners mistakenly refer to are the reports ultimately submitted

to the Administrator informing him of the number of apprentices in

the JAC program. A-42 n.3.

8

cant given the district court’s earlier finding, after trial,

that Local 28 had used the permit system to restrict the size

of its membership with the illegal effect of denying non

whites access to employment opportunities in the sheet

metal industry. A-345-46.

Petitioners were also held in contempt for violating the

provisions of the O&J and RAAPO requiring Local 28 and

the JAC to devise and implement a written plan for an ef

fective general publicity campaign designed to dispel their

reputation for discrimination in non-white communities. A-

152-53. It was undisputed that the general publicity plan

required by the O&J and RAAPO was never formulated,

much less implemented. Finally, petitioners were held in

contempt for failing, since 1976, to comply with the report

ing requirements of the O&J and RAAPO and with the Ad

ministrator’s request for information relevant to the im

plementation of RAAPO. A-154-55.

The district court denied petitioners’ cross-motion to

terminate the O&J and RAAPO, finding that its purposes

had not been achieved and that it had not caused petitioners

unexpected or undue hardship. A-157.

On April 11,1983, the City brought a proceeding against

Local 28 and the JAC for additional violations of the O&J

and RAAPO. After a hearing, the Administrator found

that Local 28 and the JAC had again acted contemptu

ously by failing to provide data required by the O&J and

RAAPO, failing to send copies of the O&J and RAAPO to

all new contractors in the manner ordered by the Adminis

trator, and failing to provide accurate reports of hours

worked by apprentices. A-127, 128-38.

The district court adopted the Administrator’s findings

and again held Local 28 and the JAC in contempt. A-125.

9

C. The Fund Order

To remedy petitioners ’ past noncompliance, the district

court imposed a fine of $150,000 for the first series of con

temptuous acts and additional fines of $.02 per hour for

each journeyman and apprentice hour worked for the sec

ond series of contemptuous acts. A-113, 114. These fines

were to be placed in an interest-bearing Local 28 Employ

ment, Training, Education and Recruitment Fund (the

“ Fund” ) to be used, among other things, to : provide finan

cial assistance to contractors otherwise unable to meet a

4.T joumeyman-to-apprentice ratio, provide incentive or

matching funds to attract additional funding from govern

mental or private job training programs, establish a tu

torial program for non-white first year apprentices, and

create summer or part-time sheet metal jobs for minority

youths who have had vocational training. A-116-18. The

Fund will “ remain in existence until the [new non-white

membership] goal set forth in the Amended Affirmative

Action Program and Order (“ AAAPO ” ) . . . is achieved

and until the Court determines that it is no longer neces

sary. ’ ’ A-114.

D. AAAPO

Because the remedial purposes of RAAPO had not been

achieved, the district court, on November 4, 1983, entered

AAAPO to replace RAAPO. A-53, 111. AAAPO modified

RAAPO in a number of respects. It modified the non-white

membership goal from 29% to 29.23% to reflect Local 28’s

expanded jurisdiction (due to merger of several unions into

Local 28) and a population change in the relevant labor

pool. A-54, 122-23. It extended the deadline for meeting

the goal until August 31, 1987. A-55. It also required that

10

one non-white applicant be indentured into the apprentice

ship program for each white applicant indentured and that,

unless waived by plaintiffs, the JACs assign each Local 28

contractor one apprentice for every four journeymen.

A-57.

E. The Appeal to the Second Circuit

Local 28 and the JAC appealed to the Second Circuit

from the district court’s contempt orders, its Fund order

and its order adopting AAAPO. They did not appeal from

the denial of their cross motion to terminate the O&J and

RAAPO.

The Second Circuit affirmed all of the district court’s

findings of contempt against Local 28 and the JAC, except

the finding based on the older workers’ provision. It also

affirmed the contempt remedies and establishment of the

Fund.

With respect to the first contempt proceeding, the Sec

ond Circuit held that the evidence “ solidly supports Judge

Werker’s conclusion that defendants underutilized the ap

prenticeship program . . . .” A-17. The court concluded,

“ [p] articularly in light of the determined resistance by

Local 28 to all efforts to integrate its membership, . . . the

combination of violations found by Judge Werker . . .

amply demonstrates the union’s foot-dragging egregious

noncompliance . . . and adequately supports his findings of

civil contempt against both Local 28 and the JAC.” A-24.

With respect to the second contempt proceeding, the

court held that the district court’s determination was sup

ported by “ clear and convincing evidence which showed

11

that defendants had not been reasonably diligent in at

tempting to comply with the orders of the court and the

Administrator.” A-22.

The court concluded that the establishment of the Fund

was an appropriate contempt remedy. The district court

had aimed the relief at the apprenticeship program, where

it would be most effective, and the Fund would compensate

those who had suffered the most from defendants’ contemp

tuous conduct. A-26.

The court affirmed AAAPO with two modifications: it

set aside the requirement that one non-white apprentice be

indentured for every white, concluding that the ratio was

unnecessary in order to assure progi’ess toward the goal,

and it modified AAAPO to permit the use of validated se

lection procedures before the 29.23% membership goal is

reached.

Finally, the court reaffirmed the 29.23% membership

goal, finding that it met the circuit’s two-pronged test for

the validity of a temporary, race-conscious affirmative ac

tion remedy. First, as the court had twice before recog

nized, the remedy was designed to correct a long, contin

uing and egregious pattern of race discrimination. Second,

the remedy “ will not unnecessarily trammel the rights of

any readily ascertainable group of non-minority individ

uals.” A-32.

It is from this judgment of the Second Circuit that peti

tioners seek review.

12

A R G U M E N T

I .

The Petition Is Untimely As To Virtually All Of

The Questions Presented.

Petitioners’ application for certiorari is untimely as to

almost all of the rulings for which review is sought. First,

petitioners seek to challenge the district court’s original

findings of intentional race discrimination, which were

made in 1975 and affirmed on appeal in 1976. A-211-15.

Petitioners declined to seek certiorari after the Second Cir

cuit’s affirmance. This Court’s rules, Sup. Ct. R. 20, and

28 U.S.C. § 2101, require that certiorari be sought no later

than ninety days after entry of the judgment to he re

viewed. Petitioners’ challenge to these findings of inten

tional race discrimination thus comes more than eight years

too late. See Parker v. Illinois, 333 U.S. 571, 576 (1948).*

* Petitioners claim no new facts or changed circumstances that

might make appropriate a belated review of the findings of liabil

ity. Their argument that Hazelwood School Dist. v. United States,

433 U.S. 299 (1977), requires a redetermination was made and right

fully rejected by the Second Circuit in 1977 in an opinion from which

the petitioners also did not seek review. Moreover, the findings of

discrimination were consistent with Hazelwood. Petitioners’ liability

was based not on statistics alone but primarily on a series of inten

tionally discriminatory practices against minorities. Opp. 2. See

also A-333 n.12.

Furthermore, certiorari is inappropriate because petitioners seek

to relitigate factual findings concurred in by both the district and ap

pellate courts. This Court has often stated that it is reluctant to dis

turb findings of fact concurred in by two lower courts. E.g., Rogers

v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 623 (1982) ; see Nat’l Collegiate Athletic

Ass’n v. Bd. of Regents,-------U .S .--------, 104 S. Ct. 2948, 2959 n,15

(1984).

13

Petitioners’ challenges to the powers of the Administra

tor and to the 29% goal are likewise untimely.* The 1975

O&J created the office of Administrator, giving it super

visory powers over petitioners’ implementation of the

court’s order. The O&J also established the 29% goal. In

1976, the Second Circuit affirmed both the appointment of

the Administrator and the 29% goal. A-220. As noted

above, petitioners did not seek certiorari from the Second

Circuit’s judgment.

Following entry of RAAPQ in 1977, petitioners ap

pealed a provision granting certain oversight powers to the

Administrator, A-165, and again challenged the goal, claim

ing that it constituted a quota forbidden by Title VII and

the Constitution, and that it was improperly calculated

under Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433 U.S.

299 (1977). The Second Circuit upheld the Administra

tor’s powers, A-165-66, and reaffirmed the goal. A-167-68.

Again, petitioners did not seek certiorari. Because peti

tioners’ challenge to the Administrator’s powers and to the

29%> goal seeks review of the Second Circuit’s 1976 and

1977 judgments, their challenge is untimely under 28 U.S.C.

2101 and Sup. Ct. R. 20. See Parker v. Illinois, 333 U.S.

at 576.

Petitioners renewed their twice failed challenges to the

powers of the Administrator and the 29% goal in 1982 when

they sought to terminate the O&J and RAAPO. A-loO-57.

The district court denied this motion, stating that “ [t]he

* The adjustment made to the goal in August 1983 by the district

court, A-119, and affirmed by the Second Circuit, A-33, was so minor

that a challenge to the 29.23 % goal is in reality a challenge to the

underlying 29% goal itself. As the district court noted, “ [t]he new

goal of 29.23% essentially is the same as the goal set in 1975.” A-123.

14

purposes of RAAPO have not been achieved and it has not

caused the defendants any unexpected or undue hardship.”

A-157. Petitioners did not, simply by moving to terminate

the goal, revive their right to seek review of the court’s

earlier judgments. Moreover, because no appeal was

taken from the district court’s order denying their motion,

A-12, the issues raised therein, such as the alleged imprac-

ticality of the goal, cannot be brought before this Court.

As this Court has stated, “ the judgment . . . was final and

appealable. Since [it was not appealed] we cannot now

consider whether the judgment was in error.” Boeing Co.

v. Van Gemert, 444 U.S. 472, 480 n.5 (1980); accord Pasa

dena City Board of Education v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424,

432 (1976) (refusing’ to consider, on certiorari from denial

of a motion to modify or terminate certain provisions of a

1970 decree, the validity of the district court’s original

judgment since it had not been appealed).*

* Petitioners’ argument that the appointment of an administrator

interferes with Local 28’s right of self-government must likewise fail

for the simple reason that the principle of union self-governance has

never been allowed to override requirements imposed by the labor laws

or any other law. See Wirts v. Local 153, Glass Bottle Blowers

Ass’n, 389 U.S. 463, 471 (1968) (the freedom allowed unions to

conduct their own elections is reserved for those elections which

conform to the democratic principles written into 29 U.S.C. § 401) ;

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., 544 F.2d 837, 858 (5th Cir.), cert, dis

missed, 434 U.S. 801 (1977) (collectively bargained agreements may

be overridden if they violate Title V II ) . In any event, the powers

granted the Administrator did not interfere in any way with Local

28’s self-governance. Local 28 retains complete autonomy regarding

its own elections and the collective bargaining process. To the extent

the Administrator monitors admission to union membership or em

ployment, such monitoring is fully justified by Local 28’s intransi

gence in refusing to obey previous court orders. Courts have often

upheld the appointments of administrators or special masters to over

see the implementation of judgments in complex cases where the

defendants have failed to comply with court orders requiring changes

in existing practices and conditions. See New York State Ass’n for

Retarded Children v. Carey, 706 F.2d 956, 962-63 (2d Cir. 1982),

cert, denied, 104 S. Ct. 277 (1983) ; Ruiz v. Estelle, 679 F.2d 1115,

(footnote continued on next page)

15

Contrary to petitioners’ argument, at Pet. 12 n.7, “ a

contempt proceeding does not open to reconsideration the

legal or factual basis of the order alleged to have been dis

obeyed and thus become a retrial of the original contro

versy.” Maggio v. Zeitz, 333 U.S. 56, 69 (1948); accord

Oriel v. Bussell, 278 U.S. 358 (1929); Halderman v. Perm-

hurst State School & Hospital, 673 F.2d 628, 637 (3d Cir.

1982) (en banc), cert, denied, 104 S. Ct. 1315 (1984); Flor

ida Steel Corp. v. N.L.R.B., 648 F.2d 233, 238 n.10 (5th Cir.

1981).* As the Third Circuit stated,

There are strong policy reasons for limiting review,

even in post-final judgment contempt proceedings, to

matters which do not invalidate the underlying order.

If a civil contemnor could raise on appeal any substan

tive defense to the underlying order by disobeying it,

the time limits specified in [the Federal rules] would

easily be set to naught [ , ] . . . presenting] the pros

pect of perpetual relitigation, and thus destroy[ing]

the finality of judgments of both appellate and trial

courts.

Halderman v. Pennhurst State School & Hospital, 673 F.2d

at 637.

1160-63 (5th Cir. 1982), cert, denied, 460 U.S. 1042 (1983) ; Gary

W. v. State of Louisiana, 601 F.2d 240, 244-45 ( 5th Cir. 1979).

Here, Local 28’s record of foot-dragging and non-compliance dates

back almost twenty years, see ante at 1-2. The powers granted the

Administrator here do not exceed those granted administrators ap

pointed in other complex civil rights cases. See, e.g., Ruiz v. Estelle,

679 F.2d at 1160-63. The Administrator’s term has been extended

simply because of Local 28’s refusal to comply with the lower courts’

orders in this case.

* The cases cited by petitioners at Pet. 12 n.7 are inapposite, as

each of those cases dealt with contempt orders imposed for violation

of a temporary restraining order, a preliminary injunction or a dis

covery order, and not for contempt stemming from a violation of a

final judgment imposed several years earlier.

16

In the present case, petitioners’ arguments were long

ago rejected by two judgments of the Second Circuit. Pe

titioners should not be allowed to relitigate these same

claims before this Court at this late date under the guise

of appealing the contempt judgment.

I I .

The Contempt Remedy Affirmed Below Is Firmly

Rooted In Well-Settled Principles Of Contempt Law.

Petitioners urge that certiorari be granted “ to restate

the principles of civil contempt.” Pet. 17. They fail, how

ever, to ground their petition on any of the traditional cri

teria that govern review on certiorari. See Sup. Ct. R. 17.1.

Petitioners’ claim is simply that in this case the lower

courts misapplied established law. Yet, as the record dem

onstrates, the decisions of the courts below were plainly

correct. A-25-26.

This Court has long held that a finding of civil contempt

allows the imposition of remedial sanctions “ for either or

both of two purposes: to coerce the defendant into com

pliance with the court’s order, and to compensate the com

plainant for losses sustained.” United States v. United

Mine Workers of America, 330 U.S. 258, 303-4 (1947); see

Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678, 691 (1978); McCornb v. Jack

sonville Payer Co., 336 U.S. 187, 191 (1949); Gompers v.

Bucks Stove & Range Co., 221 U.S. 418, 443-44 (1911).

The compensatory nexus between the injury inflicted by

the defendants’ contumacious conduct and the remedies

imposed is manifest. The district court concluded, and the

17

Court of Appeals agreed, that petitioners’ contumacious

conduct “ impeded the entry of non-whites into Local 28 in

contravention of the [district court’s] prior orders” and

‘ ‘ that the collective effect of these violations has been to

thwart the achievement of the 29% goal of non-white mem

bership in Local 28 established by the court in 1975.”

A-26,150,155. Undeniably, this obstruction of the remedial

relief previously ordered by the district court—particu

larly the deliberate underutilization of the apprentice pro

gram by Local 28 and the JAO—injured the class of non

whites interested in becoming Local 28 sheet metal workers

who are the intended beneficiaries of the O&J and RAAPO.

By deliberately shifting employment opportunies to jour

neymen, virtually all of whom were white, rather than train

ing new apprentices on a non-discriminatory basis, peti

tioners ensured that they would achieve only minimal

progress in increasing the proportion of minorities in their

membership. Although those thus denied the intended

remedial benefit of the district court’s orders may not all

have been individually identifiable, the injury inflicted is

real and substantial: but for petitioners’ contemptuous

conduct, there would have been more non-white apprentices

and further progress toward attainment of the 29% re

medial goal.

The Fund order directs that the compensatory contempt

fines assessed against petitioners be used to attract addi

tional qualified non-whites into the apprentice program and

to assist them in completing the program by establishing

counseling and tutorial services, by providing financial as

sistance to any non-white apprentice unemployed or ex

periencing financial hardship during the first apprentice

term, and by funding part-time and summer jobs for non

18

white youths in vocational programs in the sheet metal or

allied trades. Further, to expand the training and employ

ment opportunities for apprentices, especially minority ap

prentices, part of the fines are to be used as incentive or

matching funds to attract governmental or private job

training programs, and to provide financial assistance to

employers who otherwise cannot afford to hire an addi

tional apprentice to meet the 4 :1 ratio required by A A APO.

A-113-18. Thus, as the Court of Appeals correctly held,

the Fund is ‘ ‘ specifically intended to compensate those who

had suffered most from [petitioners’ ] contemptuous con

duct,” and it does so “ by improving the route [non-whites]

most frequently travel in seeking union membership.”

A-26.

Moreover, because the Fund order requires petitioners

to make additional periodic payments into the Fund until

they have fully complied with the O&J and A A APO by

eradicating the effects of their persistent and intentional

exclusion of non-whites, the Fund order serves a coercive

function as well. Under the terms of RAAPO, full compli

ance should have been achieved by July 1, 1982. Yet, in

April 1982, after 7 years under remedial court orders, only

10.8% of petitioners’ members were non-white. In a classic

exercise of coercive contempt powers, the Fund order gives

the petitioners an opportunity to purge themselves of con

tempt and to recover excess monies from the Fund upon

achieving, however belatedly, full compliance with the O&J

and AAAPO. See Penfield Co. v. Securities & Exchange

Commission, 330 U.S. 585, 590 (1947).

Petitioners insist that this Court conduct a highly indi

vidualized factual analysis to determine whether, as they

19

assert, there is an imperfect match between petitioners’

contumacious acts and the Fund designed to compensate

for those acts. Such fact-specific assertions, addressed to

a voluminous factual record that was carefully considered

by the Court of Appeals, do not warrant this Court’s re

view. See National Collegiate Athletic Association v.

Board of Regents,------U .S.------- , 104 S. Ct. 2948, 2959 n.15

(1984); Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 623 (1982). In any

event, this Court recognized long ago that a perfect match

between the injury inflicted and the compensatory contempt

remedy fashioned is not always possible, and thus is not an

essential ingredient of such a remedy. See Gompers v.

Bucks Stove & Range Co., 221 IT.S. 418, 444 (1911) (noting

that a compensatory civil contempt fine must be “ measured

in some degree” by the injury caused by the disobedient

act). By assisting non-whites’ entry into and completion

of the apprentice program and by expanding training and

employment opportunities for non-white apprentices, the

Fund order will accelerate the integration of Local 28,

remedying to a large degree the injuries inflicted by peti

tioners’ obstruction of the prior remedial orders.

Petitioners’ argument, that even narrowly fashioned

remedial contempt sanctions are unavailable to redress

clear injury solely because the injured victims are not in

dividually identifiable, would, if accepted, as this Court has

remarked in a different but related context, “ operate to

prevent accountability for persistent contumacy. Mc-

Cornb v. Jacksonville Paper Co., 336 TT.S. 187, 192 (1949).

Such an inflexible bar would enable a union or employer to

violate with impunity a judgment enjoining discriminatory

practices, provided that in continuing to pursue discrim

inatory practices, the defendant ensured that individual

2 0

victims could not be identified (i.e., by continuing a dis

criminatory reputation, thereby deterring minority appli

cations, or by failing to retain applications). Surely, as

the Court of Appeals implicitly recognized, “ the force and

vitality of judicial decrees derive from more robust sanc

tions.” Id. at 191.

H I .

The Petition Should Be Denied Because The Court

Below Correctly Concluded That This Court’s Holding

In Firefighters v. Stotts Was Not Controlling And Be

cause This Case Provides An Inappropriate Vehicle For

Evaluating Race-Conscious Remedies Under Title VII.

Petitioners argue that certiorari should be granted be

cause the court below, and other lower courts, have failed

to follow what petitioners characterize as this Court’s

holding in Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts, ——

U .S .------ , 104 S. Ct. 2576 (1984). In the alternative, peti

tioners argue that, if Stotts does not preclude race-con

scious remedies under the facts presented, the Court should

grant certiorari to determine whether race-conscious rem

edies that benefit unidentifiable victims can ever be

awarded in a Title V II case. Not only do petitioners mis-

characterize Stotts, they ignore this Court’s previous hold

ings and the unanimous conclusion of the courts of appeals

that affirmative race-conscious remedies can be appropriate

and necessary means of eliminating employment discrim

ination. Moreover, petitioners overlook the unique facts of

this case, their untimeliness in challenging the 29% hiring

goal, and the complicating factor of the district court’s con

tempt powers pursuant to which the Fund was established.

21

Petitioners contend that Stotts held that section 706(g)

of Title Y II prohibits all race-conscious remedies except

those designed to compensate identifiable victims of dis

crimination. To the contrary, Stotts held only that “ the

District Court exceeded its powers in entering an injunction

requiring white employees to be laid off, when the otherwise

applicable seniority system would have called for the layoff

of black employees with less seniority.” 104 S. Ct. at 2585

(footnotes omitted). The Court concluded that section

703(h) of Title VII bars a court from overriding a borwi fide

seniority plan by granting retroactive seniority to individ

uals never identified as victims of discrimination. Id. at

2589.

This Court did not hold in Stotts that affirmative, pros

pective race-conscious remedies, imposed after a finding of

past intentional race discrimination, are prohibited.* The

discussion in Stotts was limited to the range of permissible

make-whole remedies and did not address the propriety of

prospective remedies which are not “ make-whole” in na

ture. Thus, in noting that its holding under section 703(h)

was supported by section 706(g), the Court stated that the

policy behind section 706(g) “ is to provide make-whole re

lief only to those who have been actual victims of illegal dis

crimination. ” Id. at 2589 (emphasis supplied). In its de

scription of the Congressional debates regarding section

706(g), the Court again repeatedly refers to the issue of

“ make-whole” relief. Id, at 2589-90 and n.15. At no point

did the Court hold that a district court was barred by that

section from fashioning prospective, race-conscious relief,

* This Court did not even suggest that the interim hiring and pro

motion goals in Stotts, which benefitted individuals not identified as

victims of discrimination, were unlawful. See JJeveraux v. Geary, 596

F. Supp. 1481, 1486 (D. Mass. 1984), afi’d, ------ F .2 d -------(1st

Cir. 1985) (No. 84-2004).

2 2

which, does not override a seniority system, in order to

remedy the effects of proven, past discrimination.

The Second Circuit therefore correctly distinguished the

instant case from Stotts on three grounds. First, the relief

awarded by the district court does not conflict with a senior

ity plan.* A-30. Second, the 29% goal and the Fund order

are prospective remedies designed to overcome past dis

crimination, unlike an award of retroactive seniority, which

by its nature is a “ make-whole” remedy. A-30. Third,

the district court’s remedies were based upon findings of

past intentional discrimination. A-31.

The Second Circuit’s conclusion that Stotts does not bar

prospective, race-conscious relief that does not override a

bona fide seniority system comports with that of every

other circuit court considering the appropriateness of race-

conscious remedies subsequent to the Stotts decision.**

* As the Court of Appeals noted nearly eight years ago in this lit

igation, seniority-based work allocation has never been a practice in

the sheet metal industry. A -166.

** Turner v. Orr, 759 F.2d 817 (11th Cir. 1985) (affirming

order that enforced consent decree provisions requiring good faith

efforts toward attainment of minority hiring and promotion goals) ;

Vanguards of Cleveland v. City of Cleveland, 753 F.2d 479 (6th Cir.

1985) (consent decree entered after a finding of race discrimination,

providing that promotions in the city fire department be made from

a list of qualified candidates on a one minority to one non-minority

basis for a limited amount of time, is appropriate where existing

seniority system was preserved) ; Diaz v. American Telephone & Tel

egraph, 752 F.2d 1356, 1360 n.5 (9th Cir. 1985) (Stotts does not

undermine the group-rights goals of Title V II ) ; Van Aken v. Young,

750 F.2d 43 (6th Cir. 1984) (upholding voluntary affirmative hiring

plan for Detroit fire department) ; Johnson v. Transp. Agency, 748

F.2d 1308 (9th Cir. 1984) (upholding a voluntary affirmative action

plan containing goals for women, minorities and handicapped per

sons) ; Palmer v. Dist. Bd. of Trustees, 748 F.2d 595 (11th Cir.

1984) (rejecting reverse discrimination claim challenging hiring made

pursuant to an affirmative action plan adopted after a finding of past

(footnote continued on next page)

23

Moreover, Justice White’s opinion in Stotts does not in

dicate disapproval of the unanimous view of the Courts of

Appeals that, in appropriate circumstances, interim goals,

such as the 29% goal at issue here, may he ordered as an

essential means to dismantle segregation in employment

caused by past discrimination.*

Petitioners’ alternative argument, that if the validity of

race-conscious remedies in cases not involving seniority

plans was not decided in Stotts, certiorari should be

granted to resolve that issue, is likewise flawed. Even if

that issue were an unresolved one, we submit that this case

is an inappropriate vehicle for deciding it. First, as dis

cussed in Point I, ante, petitioners’ challenge to the 29%

minority hiring goal is simply untimely. Second, the Fund

was developed as a sanction for petitioners’ contumacious

discrimination) ; Wygant v. Jackson Bd. oj Educ., 746 F.2d 1152

(6th Cir. 1984), cert, granted, 105 S. Ct. 2015 (1985) (No. 1340,

1984 Term) (upholding collective bargaining agreement requiring

that, in event of layoffs, percentage of minority teachers laid off would

not be greater than current percentage of minority personnel em

ployed) ; Kromnick v. School Dist., 739 F.2d 894 (3d Cir. 1984),

cert, denied, 105 S.Ct. 782 (1985) (upholding teacher reassignment

system that required each school to employ between 75% and 125%

of the existing proportion of black teachers employed city-wide).

* See, e.g., Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257, 294 (D.C. Cir.

1982) ; Boston Chapter, N AACP, Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017

(1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975) ; Ass’n Against

Discrimination in Employment, Inc. v. City of Bridgeport, 647 F.2d

256 (2d Cir. 1981), cert, denied, 455 U.S. 988 (1982); United

States v. Int’l Union of Elevator Constructors, Local 5, 538 F.2d

1012 (3d Cir. 1976) ; Chisolm v. United States Postal Serv., 665

F.2d 482 (4th Cir. 1981); James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings

Co.. 559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1034

(1978) ; United States v. Int’l Bhd. of Electrical Workers, Local 38,

428 F.2d 144 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 400 U.S. 943 (1970) ; United

States v. City of Chicago, 663 F.2d 1354 (7th Cir. 1981) ; United-

States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 (8th Cir. 1973) ; United

States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971) ; United States v. Lee Way Motor Freight,

Inc.’, 625 F.2d 918 (10th Cir. 1979).

24

conduct, and not as part of the relief granted pursuant to

the judgment in the underlying Title VII case. Whatever

questions remain open after Stotts should not be decided in

the context of a trial court’s exercise of its contempt

powers, as a district court’s power to impose contempt

sanctions rests not on the underlying statute but, upon the

court’s equitable power to enforce its own decrees. Mc-

Comb v. Jacksonville Paper Co., 336 U.S. 187, 193 (1949)

(“ the measure of the court’s power in civil contempt pro

ceedings is determined by the requirements of full remedial

relief” ). Belief that may not be available in an underlying

action may thus be proper as a remedy for contempt of a

judgment in that action. Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. at 690-

92. Third, certiorari is inappropriate because, as is re

flected by the absence of any split in the circuits, ante at

23, the Second Circuit was correct in holding that prospec

tive race-conscious remedies, designed to overcome the

effects of past discrimination, are permissible under sec

tion 706(g).

Section 706(g) recognizes the dual goals of Title VII by

providing for both make-whole relief and affirmative relief.

The last sentence of section 706(g) forbids courts from or

dering the “ hiring, reinstatement, or promotion of an in

dividual as an employee . . . if such individual was . . . re

fused employment or advancement . .. for any reason other

than discrimination.” 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) (emphasis

added). It has no bearing on affirmative race-conscious

remedies, which are governed by the first sentence of sec

tion 706(g), authorizing a court to “ order such affirmative

action as may be appropriate . . . . ” Id. Bather, it merely

precludes a court from ordering that a particular individ

ual be hired, promoted or reinstated if an employer pre

25

viously refused to do so for non-discriminatory reasons.

Affirmative remedies, in contrast, do not require the hiring,

promotion or reinstatement of any particular individual,

and do not create a right to a particular job on behalf of a

particular individual. Rather, they are designed to over

come and eradicate systemic discrimination.*

Title VII remedies cannot be “ colorblind,” Regents of

the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 353

(1978) (Brennan, White, Marshall and Blackmun, J.J.), if

they are “ to eliminate those discriminatory practices and

devices which have fostered racially stratified job environ

ments to the disadvantage of minority citizens.” McDon

nell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800 (1973).

Where, as here, a persistent pattern and practice of unlaw

ful discrimination is proven, race-conscious relief must be

available not only to make whole the identified victims of

discrimination, but also to eradicate the continuing effects

of past discrimination. See International Brotherhood of

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 364-65 (1977);

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 764,

771 (1976); Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

421 (1975).

* This Court has recognized that such relief will often benefit un

identified victims of an employer’s pattern and practice of discrimina

tion. In f l Blid. of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 330 n.4,

361 n.47 (1977) (partial consent decree required that vacancies be

filled temporarily on a one-to-one minority/white ratio).

26

The Remedial Orders At Issue, Narrowly Tailored

To Further The Compelling Interest In Eradicating

Proven Systemic Discrimination, Fully Comport With

The Governing Principles Of Equal Protection.

Echoing the same arguments offered in support of their

erroneous Title VII analysis, petitioners assert that race-

conscious elements of AAAPO and the Fund order deny

equal protection of the law to whites because “ the non

whites benefitting from the program are not identifiable

victims of past discrimination, and the whites discriminated

against by the program are not persons who practiced dis

crimination.” Pet. 14. Yet this Court long ago recog

nized that judicial remedies must often be race-conscious to

redress meaningfully proven systemic discrimination, and

that such remedies, even if non-victim specific, pass consti

tutional muster. See, e.g., Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 28 (1971).

Where, as here, long-standing and pervasive discrim

ination has been established, race-conscious governmental

action, if remedial and properly tailored, is constitution

ally permissible even though it benefits unidentified mem

bers of the group suffering the discrimination. Fullilove

v. Klutsnick, 448 U.S. 448, 482-83 (1980) (Burger, C.J.,

White and Powell, J .J .) ; id. at 517-19 (Brennan, Marshall

and Blackmun, J.J., concurring in the judgment); Regents

of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. at 307

(Powell, J . ) ; id. at 355-79 (Brennan, White, Marshall and

Blackmun, J .J .) ; United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430

U.S. 144, 159-62 (1977) (White, Brennan, Stevens and

IV.

27

Blackmun, J .J .) ; id. at 179-80 (Stewart and Powell, J.J.,

concurring); McDaniel v. Barresi, 402 U.S. 39, 41 (1971);

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402

U.S. at 18-21; United States v. Montgomery County Board

of Education, 395 U.S. 225 (1969); South Carolina v. Katz-

enbach, 383 U.S. 301, 308 (1966). Moreover, a narrowly

tailored, race-conscious remedy is permissible even if it

results in a “ sharing of the burden by innocent parties.”

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. at 484 (Burger, C.J., White

and Powell, J .J .) ; id. at 518 (Brennan, Marshall and Black

mun, J.J., concurring in the judgment).

As modified by the Second Circuit, AAAPO does not

require indenture of any specific ratio of non-white appren

tices. Accordingly, the burden to be shared by whites is

the m inimum required to redress the historic exclusion of

minorities from Local 28’s ranks. No incumbent union

member or readily identifiable applicant will be displaced

by AAAPO. Similarly, the Fund order is properly fash

ioned to provide compensatory services to the class of non

whites injured by petitioners’ contemptuous conduct and

does not impose any burden on white union members or ap

plicants. Moreover, some provisions of the Fund order,

particularly those which provide for financial assistance to

employers that cannot otherwise meet the 1 :4 apprentice to

journeymen requirement of AAAPO, and for incentive or

matching funds to attract additional funding from govern

mental or private job training programs, are race-neutral

and operate to the benefit of whites and non-white appren

tices alike.

The Second Circuit’s rejection of petitioners’ constitu

tional challenge to AAAPO and the Fund is thus consistent

28

with the governing principles formulated by this Court.

There is no conflict among the circuits. No review on these

bases is warranted.

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, respondents respectfully

pray that the petition for certiorari be denied.

Dated: July 19,1985

New York, New York

Respectfully submitted,

Frederick A. O. Schwarz, Jr.

Corporation Counsel of the

City of New York

Attorney for Respondent

the City of New York

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

Lorna B. Goodman

L aura J. Blankfein

L in B. Saberski

Assistant Corporation Counsel

Robert A brams

Attorney General

of the State of New York

Attorney for Respondent

New York State Division

of Human Rights

Suite 45-08

Two World Trade Center

New York, New York 10047

(212) 488-7510

Robert H ermann

Solicitor General

O. Peter Sherwood

Deputy Solicitor General

Rosemarie R hodes

L awrence S. K a h n *

A lan D. A viles

M artha J. O lson

Assistant Attorneys General

*Counsel of Record

" ^ ^ > 3 0 7 B a r P r e s s , Inc., 132 Lafayette St., N e w York 10013 - 966-3906

(2981)