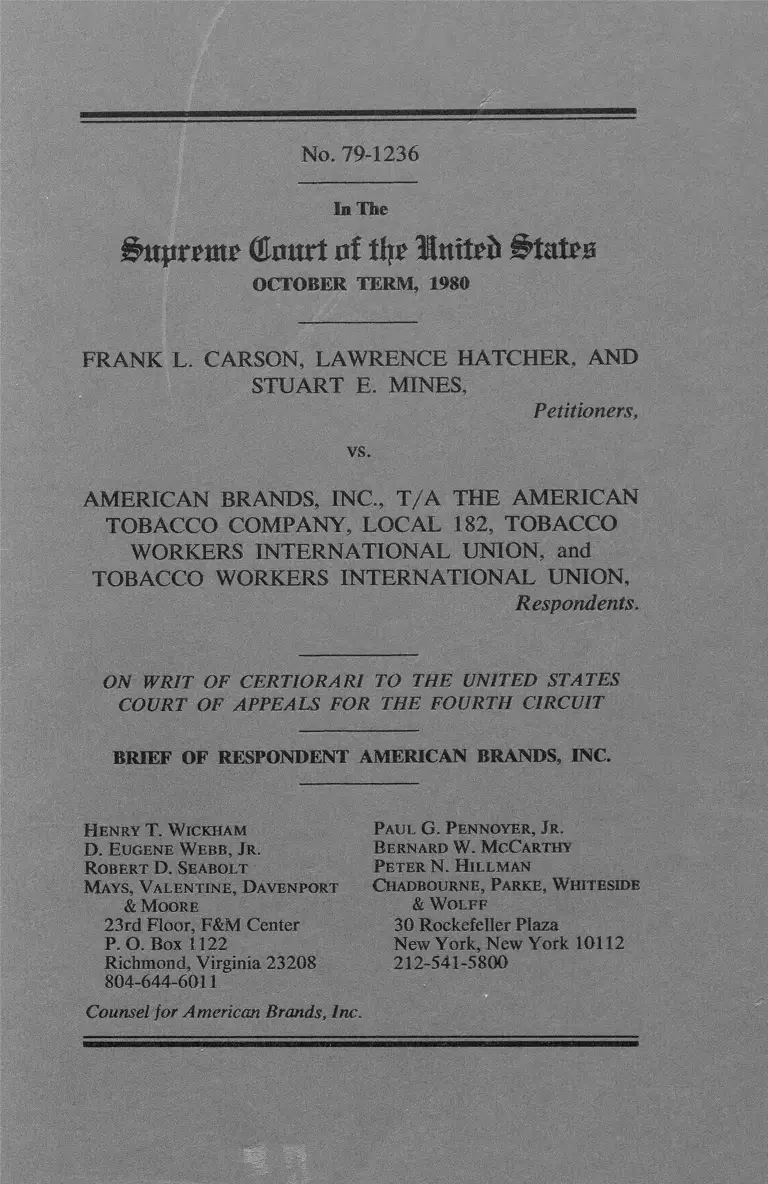

Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Brief of Respondent American Brands, Inc.

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carson v. American Brands, Inc. Brief of Respondent American Brands, Inc., 1980. 58ae0d0d-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/201c0b72-9f0e-429d-ace9-ceb6ffe45626/carson-v-american-brands-inc-brief-of-respondent-american-brands-inc. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

No. 79-1236

In The

Cfourt nf tfy? United i^tata

OCTOBER TERM, 1980

FRANK L. CARSON, LAWRENCE HATCHER, AND

STUART E. MINES,

Petitioners,

vs.

AMERICAN BRANDS, INC., T /A THE AMERICAN

TOBACCO COMPANY, LOCAL 182, TOBACCO

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, and

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION,

Respondents.

ON W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT AMERICAN BRANDS, INC.

Henry T. Wickham

D. Eugene Webb, Jr.

Robert D. Seabolt

Mays, Valentine, Davenport

& Moore

23rd Floor, F&M Center

P. O. Box 1122

Richmond, Virginia 23208

804-644-6011

Counsel for American Brands, Inc.

Paul G. Pennoyer, Jr.

Bernard W. McCarthy

Peter N. H illman

Chadbqurne, Parke, Whiteside

& Wolff

30 Rockefeller Plaza

New York, New York 10112

212-541-5800

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the District Court’s order refusing to enter

a proposed consent decree is an appealable interlocutory

order under either 28 U.S.C. § 1291 or § 1292(a)(1).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED ............................................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES...... .. ................................................ iii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT .................................................... 5

ARGU M EN T.................................................................................... 8

I. The District Court’s Order Refusing Entry of a Proposed

Consent Decree Is Not Appealable Under the Judicially

Created Collateral Order Exception to 28 U.S.C. § 1291 . . 8

A. The order did not conclusively determine the disputed

question................................................................ 10

B. The order did not resolve an important issue completely

separate from the m erits ....................... 12

C. The order is not effectively unreviewable............. 18

D. The Ninth Circuit’s reasoning in Norman v. McKee is

not persuasive..................................................................... 23

II. The District Court’s Order Refusing Entry of the Consent

Decree Is Not Appealable Under the Congressionally

Created Exception to the Finality Rule, 28 U.S.C. § 1292

(a )(1 ) ...................................................................................... 26

A. As a narrow exception to the final judgment rule, sec

tion 1292(a)(1) should be strictly construed............... 26

B. The rejection of the tendered consent decree did not

cause irreparable consequences which can be alleviated

only through allowance of interlocutory appeal . ........... 28

1. The order could be reviewed both prior to and

after final judgment ......................................... - .......... 28

u

Page

Page

2. The order did not affect or pass on the legal

sufficiency of any claims for injunctive relief. . . . . . .

3. The Fifth Circuit City of Alexandria case was

wrongly decided............................................................

C. The burden on the judicial system from allowing

interlocutory appeals from orders rejecting consent

decrees outweighs any consequences of postponing

judicial review ...................................................................

CONCLUSION 42

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Page

Adickes v. S. H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1 9 7 0 ) ................... 9

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1 9 7 4 ) ............. 16

Autera v. Robinson, 419 F.2d 1197 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) ............... 17

Axinn & Sons Lumber Co. v. Long Island Rail Road Co.,

No. 79-3082 slip op. (2d Cir., August 11, 1980) ........... 20

Baltimore Contractors, Inc. v. Bodinger, 348 U.S. 176

(1955) ......................................................................... 26 ,27,33,41

Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 446 F. Supp. 780 (E.D. Va.

1 9 7 ']') ......................................................................................passim

Carson V. American Brands, Inc., 606 F.2d 420 (4th Cir.

1979), cert, granted, — U.S. — , 100 S.Ct. 1643 (1980) . .passim

City of Morgantown, W. Va. v. Royal Insurance Co., 337 U.S.

254 (1949) ................... ................................................... .27, 35

Cobbledick v. United States, 309 U.S. 323 (1940) ................... 9

iii

Page

Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp.,

337 U.S. 541 (1949) ......................................... .......... 9, 11, 14, 32

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, 437 U.S. 463 (1 9 7 8 ) ...........passim

Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Railway Co., 406 F.2d 399

(5th Cir. 1969) ........................................................................... 16

Dickinson v. Petroleum Conversion Corp., 338 U.S. 507

(1950) ........................................................................................... 22

Risen v. Carlisle & Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156 (1974)................. 8, 11

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Community

Organization, 420 U.S. 50 (1 9 7 5 ) ............................................. 17

Flinn v. FMC Corp., 528 F.2d 1169 (4th Cir. 1975), cert.

denied, 424 U.S. 967 (1976) ............................................... 14,34

Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., 437 U.S. 478

(1978) ....................................................................................... passim

General Electric Co. v. Marvel Rare Metals Co., 287 U.S. 430

(1932) ....................................................................................... 31,36

In re General Motors Corp. Engine Interchange Litigation, 594

F.2d 1106 (7th Cir. 1979) ....................... 25

In re International House of Pancakes Franchise Litigation, 487

F.2d 303 (8th Cir. 1973) .......................................................... 14

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1 9 7 7 ) ............................. 5 ,38

Mercantile National Bank v. Langdeau, 371 U.S. 555 (1963). . 14

Myers v. Gilman Paper Corp., 544 F.2d 837 (5th Cir.), cert,

denied sub nom., Local 741 International Brotherhood of

Electrical Workers v. Myers, 434 U.S. 801 (1977)................. 37

Norman v. McKee, 431 F.2d 769 (9th Cir. 1970), cert, denied,

401 U.S. 912 (1971) ..................................................23, 24, 25, 26

IV

Page

Peter Pan Fabrics, Inc. v. Dixon Textile Corp., 280 F.2d 800

(2d Cir. 1960) ............................................. 40

Rodgers v. US. Steel Corp., 541 F.2d 365 (3d Cir. 1976). . .20, 30

Ruiz v. Estelle, 609 F.2d 118 (5th Cir. 1980) ........................20, 30

Russell v. American Tobacco Co., 528 F.2d 357 (4th Cir.

1975) ...................................... 5

Sampson V. Murray, 416 U.S. 61 (1974) ..................................... 28

Sagers v. Yellow Freight Systems, Inc., 529 F.2d 721 (5th Cir.

1976) ......................................................................... 38

Seigal v. Merrick, 590 F.2d 35 (2d Cir.

1978) ........................................ 3 ,1 0 ,14 ,23 ,25 ,29

Shelley v. Kraemer, 344 U.S. 1 (1947) ......................................... 14

Speed Shore Corp. v. Denda, 605 F.2d 469 (9th Cir. 1979) . . . . 17

Stateside Machinery Co. V. Alperin, 526 F.2d 480 (3d Cir.

1975) ............................................................................................. 38

Switzerland Cheese Association, Inc. v. E. Horne’s Market, Inc.,

385 U.S. 23 (1966) ............................................... ............ .. .27, 35

Tacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973)......................................... 9

United Founders Life Insurance Co. V. Consumers National Life

Insurance Co., 447 F.2d 647 (7th Cir. 1971)............................. 14

United States v. City of Alexandria, 614 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir.

1980) ................. . . . . . . . . . 2 7 , 3 6

United States v. T.l.M.E.-D.C., 517 F.2d 299 (5th Cir. 1975),

vacated and remanded on other grounds sub nom., Inter

national Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1 9 7 7 ) ........................................................................... 38

United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC v. Weber, 443

U.S. 193 (1979) ........................................ passim

Virginia Petroleum Jobbers Association v. Federal Power

Commission, 259 F.2d 921 (D.C. Cir. 1958)............................. 28

v

Page

W. J. Perryman & Co. v. Penn Mutual Fire Insurance Co., 324

F.2d 791 (5th Cir. 1963) ............................................... .. 17

West Virginia v. Chas. Pfizer & Co., 440 F.2d 1079 (2d Cir.),

cert, denied sub. nom., Cotter Drugs, Inc. v. Chas. Pfizer &

Co., 404 U.S. 871 (1971) . ........................................................ 14

Williams v. First National Bank, 216 U.S. 582 (1910)............... 17

Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ..........................................................................passim

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1) ........................................................ .. .passim

28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) .......................................................... .. 20, 26, 30

28 U.S.C. § 1651 .................................................................... .. 20

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ................................................. ........................... 2

Title VII, Civil Rights Act

of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq. ............... ....................................................... passim

Rules

Fed. R. Civ. P. 23 (e) ......................................................14, 15, 28, 29

Fed.R .A pp.P . 21(a) ..................................................................... 20

Fed. R. App. P. 41 ........................................................ 4

Treatise

16 C. Wright, A. Miller, E. Cooper & E. Gressman,

Federal Practice and Procedure, § 3924 (1977) ..................... 38

VI

No. 79-1236

In The

&upr?tn? (Emtrt of tljp Imtefc States

OCTOBER TERM, 1980

FRANK L. CARSON, LAWRENCE HATCHER, AND

STUART E. MINES,

Petitioners,

vs.

AMERICAN BRANDS, INC., T /A THE AMERICAN

TOBACCO COMPANY, LOCAL 182, TOBACCO

WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION, and

TOBACCO WORKERS INTERNATIONAL UNION,

Respondents,

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT AMERICAN BRANDS, INC.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Petitioners Frank L. Carson, Lawrence Hatcher and

Stuart E. Mines filed this action against respondents Ameri

can Brands, Inc. t'/a The American Tobacco Company

(“American”), Local 182, Tobacco Workers International

Union, and Tobacco Workers International Union on Oc

tober 24, 1975, in the United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Virginia, Richmond Division. Petitioners

brought the suit on behalf of themselves and an alleged

2

class consisting of “all black persons who have sought

employment and who are employed or might in the future

be employed by the Company's [American’s] Richmond

Leaf Department. . . They alleged violations by respon

dents of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended, 42U.S.C. § 2Q00e etseq. (“Title VII”) and of 42

U.S.C. § 1981 (J.A. la-12a). In their respective answers,

respondents denied any violation of the cited statutes (J.A.

13a-23a).

On January 27, 1976, at a pre-trial conference, an order

was entered by the District Court allowing time for dis

covery and setting the case for trial to begin on May 2,

1977. By letter dated March 25, 1977, counsel for peti

tioners informed the Court that the parties would present

a consent decree at the final pre-trial conference on April

1, 1977, and that they wished to discuss the entry of the

proposed decree at that conference.

During the course of the April 1 conference, the Court

expressed concern about the effect of the proposed decree

on individuals other than the parties before the Court and

questioned whether certain provisions of the tendered decree

might be violative of tire law. The District Court noted that

the parties were jointly seeking entry of the decree and to

that extent were no longer in an adversary posture, and re

quested that the parties submit memoranda in support of

entry.

After receiving the requested memoranda, the Court,

by order dated June 1, 1977, declined to enter the tendered

decree. Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 446 F. Supp. 780

(E.D. Va. 1977). On June 24, 1977, petitioners filed a

notice of appeal from the order to the Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit (J.A. 57a-58a).

By order dated October 12, 1977, the Court of Appeals

established a briefing schedule. However, on January 10,

3

1978, before briefs were due, respondents informed the

clerk of the Court of Appeals that they had no position on

the merits of the appeal and that the appeal was not an

adversary proceeding as required by Article III of the United

States Constitution. Respondents stated that under these

circumstances, they would not submit briefs unless so

ordered by the Court (J.A. 59a-60a).

Petitioners then filed a motion in the Court of Appeals for

summary reversal of the District Court’s order, and the

Court of Appeals ordered respondents to brief a position

in opposition to the motion for summary reversal. The

brief was submitted and the Court of Appeals denied peti

tioners’ motion by order entered on January 31, 1978, an

order which was rescinded on February 8, 1978. On March

27, 1978, the Court of Appeals again denied the motion

for summary reversal and directed the clerk to invite re

spondents to file a brief addressing the merits of the appeal

(J.A. 62a-64a).

A panel of the Court of Appeals heard oral argument

on October 3, 1978. While the matter was under advise

ment, the clerk informed the parties by letter dated January

25, 1979, of the panel’s concern as to whether it had

jurisdiction to entertain the appeal in light of a recent

opinion, Seigal v. Merrick, 590 F.2d 35 (2d Cir. 1978),

and requested that counsel file supplemental memoranda ad

dressing this concern by February 9 (J.A. 65a-66a). After

the filing of the requested memoranda, the Court of Appeals,

sua sponte, agreed to en banc consideration of the case with

out oral argument on June 5, 1979.

On September 14, 1979, the Court of Appeals, three

judges dissenting, dismissed the appeal holding that the

District Court’s refusal to enter the proposed consent decree

was not an appealable order under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)

4

(1). Carson v. American Brands, Inc., 606 F.2d 420, 425

(4th Cir. 1979). The mandate of the Court of Appeals is

sued on October 5, 1979, in accordance with Fed. R. App.

P. 41. Petitioners made no attempt to obtain a stay of the

mandate.

After informing petitioners’ counsel by letter that respon

dents no longer consented to the entry of the proposed de

cree, the respondents, by motion filed with the District

Court on October 10, 1979, requested the Court to hold

a pre-trial conference for the purpose of establishing a new

trial date. In the motion, respondents stated that they no

longer consented to the entry of the proposed decree (J.A.

67a-68a). Petitioners filed no response to this motion, nor

did they at any time lodge an objection to respondents’ with

drawal of consent with either the Court or counsel.1

By notice dated November 2, 1979, the parties were ad

vised that the case had again been placed on the docket for

trial (J.A. 69a-70a), and at a pre-trial conference on No

vember 15, 1979, the District Court set the case for trial

to begin on February 4, 1980. Petitioners made no objec

tion.

Two weeks after the conference at which the case was set

for trial, respondents were served with petitioners’ applica

tion for an extension of time in which to file a petition for

writ of certiorari. On December 5, 1979, petitioners moved

1 Respondents suggested in their Brief in Opposition to Petition for

Writ of Certiorari that there was no “case or controversy” within

the meaning of Article III of the United States Constitution and that

the issue on this appeal should be considered moot in view of re

spondents’ withdrawal of consent to the proposed decree, which oc

curred without objection by petitioners when the case was back before

the District Court for the first time in 28 months, there having been

no stay of the mandate (Resp. Br. in Opp. at 4-10). Certiorari

having been granted, American will brief here only the merits of the

issue on appeal.

5

the District Court for a stay of all further proceedings pend

ing disposition of their petition. The District Court granted

this request by order dated December 17, 1979.

This Court granted the petition for writ of certiorari

on June 16, 1980, and expressly limited the appeal to the

question of whether an order refusing to enter a proposed

consent decree is an appealable order under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1291 or § 1292(a)(1).2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The finality requirement of 28 U.S.C. § 1291 represents a

legislative judgment that a succession of separate appeals

from interlocutory orders would have a debilitating effect on

judicial administration. The District Court’s order rejecting

a proposed consent decree does not come within the small

class of exceptions to the final judgment rule established by

the judicially-created “collateral order” doctrine.

2 Petitioners’ Statement of the Case (Pet. Br. at 5-21) contains few

citations to the joint appendix or record in the case to support their

factual allegations, particularly with respect to the description of em

ployment practices and policies at American’s Richmond Leaf Plant.

Petitioners’ description of such practices and policies is largely in

accurate, but those practices and policies are not relevant to the

limited issue of appealability before this Court.

American is compelled to comment on petitioners’ referring the

Court to Russell v. American Tobacco Co., 528 F.2d 357 (4th Cir.

1975), for a description of “the operation of the American Tobacco

Company” (Pet. Br. at 8 n .l) . The Russell case has no relevance

here whatsoever. First, the merits of American’s operations are not

at issue on this appeal. Second, even if the merits were at issue, the

Russell case concerns an entirely different facility, in a different state,

and thus the facts stated in Russell (not part of the record in this

case) are irrelevant. Moreover, the Russell action is presently pend

ing in the Middle District of North Carolina on reconsideration in

light of International Bhd. of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S.

324 (1977), and other recent Supreme Court cases.

6

The District Court’s order does not satisfy any element

of this Court’s three-part collateral order test. Coopers &

Lybrand v. Livesay, 437 U.S. 463 (1978). First, the order

did not conclusively determine any disputed question.

Even assuming that there is a general right to settle litiga

tion, nothing in the District Court’s order precluded settle

ment at another time by the tendered decree or some alter

native consent decree.

Second, the District Court’s order did not resolve an

important issue completely separate from the merits. Pe

titioners contend that the important collateral issue is

the right to settle a Title ¥11 class action under Weber

( United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-CLC v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979)). The Weber opinion, how

ever, was delivered two years after the District Court’s order,

was not considered by the courts below, and is encompassed

within the questions denied review by the Court in this case.

Even assuming that Weber is applicable to settlement

of litigation, the District Court’s order in this case of

necessity involved considerations that were enmeshed in

the factual and legal issues comprising petitioners’ claims,

and so no “collateral” rights were injured by the District

Court’s order. Furthermore, the importance of the right

to settle Title VII actions is no different from the right to

settle any other litigation, and there is no reason for creating

a special exception to the final judgment rule for Title VII

cases.

Third, the District Court’s order is effectively reviewable,

both before and after possible trial, and therefore fails

to satisfy the final prong of the collateral order test. The

same or alternative consent decree proposals could be pre

sented by the parties for the District Court’s consideration at

any stage of the litigation. If none are accepted and the

7

parties go to trial, any party could advocate on appeal there

from the settlement alternative most favorable to its position.

In situations where actual final determinations are made to

the detriment of legitimate rights, immediate appellate re

view is available through certification or mandamus. In sum,

no irreparable harm would flow from a decision holding

the collateral order doctrine inapplicable and postponing

appellate review until final judgment.

n.

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1), the statutory exception to the

rule of finality held by the Court of Appeals below to be

inapplicable to the District Court’s order rejecting a pro

posed consent decree, has always received a narrow inter

pretation by this Court. Postponing appellate review in this

case presents no serious, irreparable consequences such as

would warrant expansion of § 1292(a) (1).

After rejection of the tendered decree, petitioners re

mained fully able to obtain injunctive relief through alter

native settlement proposals, a motion for injunctive relief, an

award of injunctive relief following trial, or through im

position of such relief on appeal. Nothing in the opinions

of the courts below foreclosed any of these opportunities

to seek and obtain injunctive relief. The District Court’s

order thus produced no irreparable effect because it could be

reviewed both prior to and after final judgment. Gardner v.

Westinghou.se Broadcasting Co., 437 U.S. 478 (1978).

Denial of entry caused no serious or irreparable harm

for the further reason that it did not dispose of any claims

for injunctive relief. The District Court may have expressed

an opinion concerning the lawfulness of the tendered decree,

but it did not pass on the legal sufficiency of petitioners’

8

claims for injunctive relief in any other form and under any

other factual circumstances.

The narrow interpretation accorded § 1292(a)(1) by

this Court has often followed from weighing the conse

quences of postponing appeal against the vital judicial in

terests militating against piecemeal review. The result urged

here by petitioners would create the potential for multiple

and unnecessary appeals, injecting appellate courts indis

criminately into the trial process. The consequences of

postponing appeal of an order rejecting a consent decree, on

the other hand, are minimal and remediable both prior to

and after final judgment.

ARGUMENT

I.

The District Court’s Order Refusing Entry Of A Proposed Consent

Decree Is Not Appealable Under The Judicially Created

“Collateral Order” Exception To 28 U.S.C. § 1291

The finality requirement of 28 U.S.C. § 1291s embodies a

long-standing legislative judgment that “ ‘[Restricting appel

late review to ‘final decisions’ prevents the debilitating effect

on judicial administration caused by piecemeal appeal dis

position of what is, in practical consequence, but a single

controversy.’ ” Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, 437 U.S.

463, 471 (1978), quoting from Eisen v. Carlisle & Jacque-

lin, 417 U.S. 156, 170 (1974). The policy of finality serves

to avoid the “obstruction to just claims that would come

from permitting the harassment and cost of a succession of

separate appeals from the various rulings to which a litiga- 3

3 28 U.S.C. § 1291 permits appellate review only from “final de

cisions of the district courts of the United States,” except where a

direct review may be had in the Supreme Court.

9

tion may give rise.” Cobbledick v. United States, 309 U.S.

323,325 (1940).

No one here contends that the District Court’s order

refusing to enter a proposed consent decree was a “final

decision” within the literal dictates of § 1291. Appealability

of an order refusing entry, therefore, lies only if the order

comes within an appropriate exception to the final judgment

rule.

Petitioners now contend that appealability of the District

Court’s order under § 1291 may be premised on the col

lateral order doctrine of Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial

Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541 (1949).4 This Court recently

articulated a strict test for application of the doctrine when

it held in Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. at

4 There is some confusion as to whether petitioners’ “collateral

order” theory of appealability was properly presented to the Court

of Appeals. At one point in the appeal, petitioners explicitly denied

that the collateral order doctrine was an issue in the case. In petition

ers’ Supplemental Memorandum to the Fourth Circuit Court of Ap

peals, filed February 9, 1979, they stated (at 2):

Because this case does not invoke the “collateral order doctrine”

of Cohen [v. Beneficial Indus. Loan Corp., 337 U.S. 541

(1949)], Seigal [v. Merrick, 590 F.2d 35 (2d Cir. 1978)] is

inapplicable.

Petitioners maintain in their brief to this Court (Pet. Br. at 20 n.

9), however, that they intended the Court of Appeals to consider this

theory as an alternative to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1). The opinion of

the Court of Appeals does not address the collateral order issue, and

it is clear from the statement of the issue before the Court of Appeals

that it was not considering § 1291 (606 F.2d at 421):

Plaintiffs seek an interlocutory appeal under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1292(a)(1) of the district court’s refusal to enter a consent

decree agreed to by the named parties in a Title VII class action.

Should this Court decide that the collateral order doctrine was not

properly submitted to the Court of Appeals, it should not now con

sider this issue. Tacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973); Adickes

v. S. H. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970).

10

468, that a trial court’s denial of class certification is not

appealable as a collateral order:

To come within the “small class” of decisions ex

cepted from the final-judgment rule by Cohen, the

order must conclusively determine the disputed ques

tion, resolve an important issue completely separate

from the merits of the action, and be effectively un-

reviewable on appeal from a final judgment. (Footnote

and citations omitted.)5

Application of the Coopers & Lybrand test to this case

demonstrates that no prong of the three-part conjunctive test

can be met with respect to the order refusing to enter the

proposed consent decree.

A. The Order Did Not Conclusively Determine

The Disputed Question

The District Court’s order does not satisfy this Court’s re

quirement that the order “must conclusively determine the

disputed question.. . . ” Id. Petitioners claim that the “dis

puted question” is the “right to reach a lawful settlement of

a Title VII employment discrimination case pursuant to the

guidelines set forth by this Court in Weber. . . ” 6 (Pet.

Br. at 30).

Even assuming the existence of such a right, the plain

fact is that there was nothing in the District Court’s opin

ion which precluded the possibility of settlement. This was

5 The articulation of this test has prompted the Second Circuit to

observe that the Coopers & Lybrand decision evidences that “'[t]he

Supreme Court has recently given an even firmer direction. . to

that Circuit’s “disinclination to erode the finality doctrine by indi

rection.” Seigal v. Merrick, 590 F.2d 35, 37 (2d Cir. 1978).

6 “Weber” refers to United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO-

CLC v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979).

11

clearly recognized by the Court of Appeals when it ob

served (606 F.2d at 424):

Under the Flinn [v. FMC Corp., 528 F.2d 1169 (4th

Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 424 U.S. 967 (1976)] analy

sis, the named parties may present a proposed decree

to the district court in any form and at any stage in the

proceedings. If one decree is refused another may be

proposed. At any time the district court can reconsider

its refusal to enter a decree. See Cohen v. Beneficial

Industrial Loan Corporation, 337 U.S. at 547, 69 S.Ct.

1221.

When a district court objects to the terms of a de

cree, alternative provisions can be presented, and per

haps a disapproved decree may be entered with further

development of the record.

Accordingly, in contrast to an order of a trial court deny

ing to a party the right to security for reasonable expenses

that might otherwise be unrecoverable, Cohen v. Bene

ficial Industrial Loan Corp., supra, or one that purports to

make final disposition of a claimed right to notice costs

that might otherwise be irretrievable, Eisen v. Carlisle &

Jacquelin, supra, the District Court’s order in this case was

inherently tentative and incomplete. A decision to allow

immediate appellate review of such an inconclusive order

(Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. at 476):

thrusts appellate courts indiscriminately into the trial

process and thus defeats one vital purpose of the final-

judgment rule—“that of maintaining the appropriate

relationship between the respective courts. . . . This

goal, in the absence of most compelling reasons to the

contrary, is very much worth preserving.” [Citing

Parkinson v. April Industries, Inc., 520 F.2d 650, 654

(2d Cir. 1975)]

This admonition is applicable here notwithstanding peti

tioners’ weak claim that the “tenor of the district court’s

12

opinion below tended to indicate that a final determination

had been made,” (Pet. Br. at 41; emphasis added.) Peti

tioners’ speculation about the District Court having made a

“final determination” of their alleged right to settle, a right

premised on a case which had not been decided at the time

of the District Court’s decision and which is, in any event,

of questionable applicability,7 cannot serve as a workable

test for appealability, nor does it present a compelling

reason for thrusting an appellate court into the trial process.

The courts of appeals should not have to examine whether

a district court’s refusal to enter a proposed consent decree

conclusively determined the disputed question by having to

assess something as nebulous as the “tenor” of its opinion.

The right to reach a settlement in this case having re

mained open to petitioners in many forms, including re

questing reconsideration by the District Court of the ten

dered decree, there was no “conclusive determination of the

disputed question.” Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, supra,

437 U.S. at 468.

B. The Order Did Not Resolve An Important Issue

Completely Separate From The Merits

Nor can this order satisfy the second prong of the col

lateral order test of “resolv[ing] an important issue com

pletely separate from the merits of the action. . . .” Coopers

& Lybrand v. Livesay, id. Here again, that “issue,” as

framed by petitioners, is their alleged right to settle “pur

suant to the guidelines set forth by this Court in Weber”

(Pet. Br. at 30). They claim that such a “right” is “separate

and anterior to the merits of the claims in the Title VII ac

tion” (id.) and “not enmeshed in the issues of a Title VII

suit” (id. at 32).

7 See discussion infra, at 13-14.

13

It is first noted that the existence of the “right” to settle

pursuant to the tendered decree, as now articulated by pe

titioners, is an issue encompassed within the “abuse of dis

cretion” questions expressly excluded from the grant of cer

tiorari in this case.8 Such a “right” is not a part of the nar

row procedural question as to which certiorari was granted,

particularly when the issue was not briefed or argued in

the courts below. As the majority in the Court of Appeals

properly observed (606 F.2d at 424):

Such argument is vital when appellate courts must

authoritatively opine about important unsettled legal

issues of the highest social concern in the amorphous

context of reviewing a trial court’s exercise of discre

tion.

This observation is even more pertinent in reviewing such

an issue in the context of a narrow procedural question.

Further, there is no such thing as a Weber right to settle

in a litigation context. Weber did not involve settlement by

parties in litigation. The limited crafts training affirmative

action plan agreed to in Weber by the employer and the

8 The questions presented in the petition and excluded by this

Court’s order issuing the writ of certiorari were the following:

2. Whether the federal district court below erred in holding

that the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States and Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, prohibit federal courts from judicially ap

proving, in the absence of discrimination by defendants against

plaintiffs and other class members, proposed consent decrees

providing for remedial use of race-conscious affirmative action

program in accordance with requirements set forth in United

Steelworkers of America, AFL-ClO-CLC v. W eber,------ U.S.

------ 61 L. Ed. 2d 480 (1979)?

3. Whether the district court below applied proper criteria,

or otherwise abused its discretion, under Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure 23(e) in refusing to approve a proposed settlement

by the parties of a Title VII class action?

14

union in a collective bargaining setting did not involve

judicial intervention in any form, either under Fed.R.Civ.P.

23 (e) or through imposition of a remedy following trial. The

constitutionality of such judicial intervention was not at

issue. Cf., Shelley v. Kraemer, 344 U.S. 1 (1947).

In any event, whether Weber is or is not involved, a right

to settle in a Title VII action is not “completely separate

from the merits of the action” (emphasis added) as required

by the Coopers & Lybrand test. Fed.R.Civ.P. 23(e) and the

appellate abuse of discretion test for review of trial court

approval or rejection of consent decrees require that a dis

trict court make a preliminary assessment of the merits of

the positions of the parties in considering a proposed con

sent decree. See, e.g., Seigal v. Merrick, supra, 590 F.2d at

38; Flinn v. FMC Corp., 528 F.2d 1169 (4th Cir. 1975),

cert, denied, 424 U.S. 967 (1976).9 Unlike the situation

posed in Mercantile National Bank v. Langdeau, 371 U.S.

555 (1963), wherein the trial court’s order determined the

ancillary but vital issue of proper forum, or that presented

by Cohen v. Beneficial Industrial Loan Corp., supra, where

in the trial court ruled on the collateral but critical ques

tion of whether a shareholder was required to post security

for costs, the District Court’s order in this case of necessity

involved considerations that were “enmeshed in the factual

and legal issues comprising the plaintiff’s cause of action.”

Mercantile National Bank v. Langdeau, supra, 371 U.S. at

558.

Such involvement with the factual and legal issues com

9 See also West Virginia v. Chas. Pfizer & Co., 440 F.2d 1079,

1085 (2d Cir.), cert, denied sub. nom., Cotter Drugs, Inc. v. Chas.

Pfizer & Co., 404 U.S. 871 (1971); In re International House of

Pancakes Franchise Litigation, 487 F.2d 303, 304 (8th Cir. 1973);

United Founders Life Ins. Co. v. Consumers Nat’l Life Ins. Co., 447

F.2d 647, 655 (7th Cir. 1971).

15

prising petitioners’ cause of action would in all likeli

hood have been even greater had the Weber issue been

presented to the District Court. Petitioners’ reliance on

the language in Weber indicating that because the plan

there was voluntary, the Court was “not concerned with

what Title VII requires or with what a court might order

to remedy a past proved violation of the Act,” (Pet. Br. at

32), is inappropriate to a matter in litigation, especially

where a court must meet its Rule 23(e) responsibilities.

The petitioners and all of the Amici also argue that the

right to settle a Title VII action is such an “important issue”

that to deny appealability of an order refusing entry of a

consent decree in a Title VII action will undercut the policy

of Title VII favoring voluntary conciliation and settlement.

Although that argument has some surface appeal, it does

not withstand examination.

Title VII does favor conciliation and the avoidance of

litigation,10 but as this Court has recognized, that policy,

10 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (1976) contains the only language in

Title VII with respect to conciliation, and that applies only to the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Section 2000e-5(b)

provides:

* * * ❖

If the Commission determines after such investigation that there

is reasonable cause to believe that the charge is true, the Com

mission shall endeavor to eliminate any such alleged unlawful

employment practice by informal methods of conference, con

ciliation, and persuasion. (Emphasis added.)

Section 2000e-5 (f) (1) provides:

If within thirty days after a charge is filed with the Commis

sion or within thirty days after expiration of any period of

reference under subsection (c) or (d) of this section, the Com

mission has been unable to secure from the respondent a con

ciliation agreement acceptable to the Commission, the Commis

sion may bring a civil action against any respondent not a gov

ernment, governmental agency, or political subdivision named in

the charge. . . .

16

to the extent it is expressed in the Act itself, is applicable

only to the agency proceedings level (Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974)):

Cooperation and voluntary compliance were selected

as the preferred means for achieving this goal. To this

end, Congress created the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Commission and established a procedure

whereby existing state and local equal employment op

portunity agencies, as well as the Commission, would

have an opportunity to settle disputes through con

ference, conciliation, and persuasion before the ag

grieved party was permitted to file a lawsuit. (Emphasis

added.)

Even the dicta from Dent v. St. Louis-San Francisco Rail

way Co., 406 F.2d 399 (5th Cir. 1969), cited by petitioners

for the proposition that “efforts should be made to resolve

these employment rights by conciliation both before and

after court action” (Pet. Br. at 35), was premised on a

specific provision of Title VII applicable only to the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission and not to Title VII

litigation generally.* 11

Accordingly, to the extent there is a policy promoting

settlement of Title VII cases once they are in litigation, it

(Cont. from preceding page)

* * ❖

Upon request, the court may, in its discretion, stay further

proceedings for not more than sixty days pending the termina

tion of State or local proceedings described in subsections (c)

or (d) of this section or further efforts of the Commission to

obtain voluntary compliance. (Emphasis added.)

11 Dent v. St. Louis— San Francisco Ry., supra, 406 F.2d at 402:

Section 706(e) further provides:

Upon request, the court may, in its discretion, stay further

proceedings for not more than sixty days pending. . .the efforts

of the Commission to obtain voluntary compliance. (Emphasis

added.)

17

is no different from the general judicial policy favoring

settlement in any litigation. See, e.g., Williams v. First

National Bank, 216 U.S. 582, 595 (1910) (“Compromises

of disputed claims are favored by the courts. . . .” ); Speed

Shore Corp. v. Denda, 605 F.2d 469, 473 (9th Cir. 1979)

(“It is well recognized that settlement agreements are ju

dicially favored as a matter of sound public policy”);

Autera v. Robinson, 419 F.2d 1197, 1199 (D.C. Cir.

1969) (“Voluntary settlement of civil controversies is in

high judicial favor”) ; W. J. Perryman & Co. v. Penn Mutual

Fire Insurance Co., 324 F.2d 791, 793 (5th Cir. 1963)

(“The law favors and encourages compromises”). The im

portance of a right to settle in Title VII actions is thus the

same as in any other litigation and there is no reason for

carving out a special exception to the final-judgment rule

for settlement agreements in Title VII cases, just as this

Court has held that there is no reason for carving out a

limited exception to the exclusive bargaining principle under

the National Labor Relations Act to accommodate the pub

lic policy purposes of Title VII in the curing of discrimina

tion. Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Com

munity Organization, 420 U.S. 50 (1975).

This Court has also observed in an analogous context

relative to special rules in class actions that (Coopers & Ly-

brand v. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. at 470):

Those rules do not, however, contain any unique

provisions governing appeals. The appealability of any

order entered in a class action is determined by the

same standards that govern appealability in other types

of litigation.

This reasoning is every bit as applicable here, there being no

unique provisions covering appeals in Title VII cases.

Directly apropos, also, is this Court’s observation (id.):

18

Respondents, on the other hand, argue that the class

action serves a vital public interest and, therefore,

special rules of appellate review are necessary to ensure

that district judges are subject to adequate supervision

and control. Such policy arguments, though proper for

legislative consideration, are irrelevant to the issue we

must decide.

For all these reasons, the order in the case now before

this Court cannot meet the second prong of the collateral

order test of “resolv[ing] an important issue completely

separate from the merits of the action. . . .” Coopers &

Lybrand v. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. at 468.

C. The Order Is Not Effectively Unreviewable

The third prong of the collateral order doctrine is that

the order “be effectively unreviewable on appeal from a

final judgment.” Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay, supra, 437

U.S. at 468.

As the Court of Appeals indicated, after final judgment

either party to the proposed consent decree may ask for re

view of the District Court’s order denying entry of the de

cree, or, for that matter, of several alternative decrees. The

parties could then argue (606 F.2d at 424):

the importance of the law and facts as they appeared

when the decree was proposed. Where alternative

or revised decrees have been presented, the parties

could advocate on appeal the alternative most favorable

to their positions in light of the law and facts appearing

when it was presented.

The availability of such final judgment review takes the

denial of entry of a proposed decree out of the rubric of

the third prong of the collateral order test.

19

Petitioners, in addressing this aspect of the collateral

order rule, state that the test is that “the order must be one

whose review cannot be postponed until final judgment

because delayed review will cause irreparable harm by

causing the rights conferred to be irretrievably lost” (Pet.

Br. at 29). In their very short treatment of this third prong

of the test (Pet. Br. at 43), however, they simply refer to

“the reasons previously mentioned [in petitioners’ brief] . . .

with respect to why the district court’s order in this case was

a final determination of petitioners’ collateral rights [and]

. .. caused petitioners’ irreparable injury.” Id. Those rea

sons are three in number, and none of them constitute the

claimed irreparable harm justifying immediate appellate

review.

Petitioners’ first reason is “[t]he right to reach a lawful

settlement . . . pursuant to the guidelines set forth by this

Court in Weber . . .” (Pet. Br. at 30). As is discussed,

supra, at 13-14, there is no such right. Its possible existence

is not a part of the narrow issue as to which certiorari was

granted. Even if there were such a right, there was nothing

in the District Court’s order which precluded the right to set

tle, including reconsideration of the proposed consent de

cree, as facts were further developed or as changes in the law

occurred after the order was entered.

The second reason advanced is the alleged “tenor of the

district court’s opinion below [which] tended to indicate

that a final determination had been made” with respect to

the so-called Weber right to settle (Pet. Br. at 41; emphasis

added). This reason has been treated, supra, at 10-12. It is

simply too speculative to support a claim of irreparable-

harm. Indeed, this reason does not comport with reality be

cause the opinion of the District Court is dated June 1,

1977, more than two years before this Court announced

20

the Weber decision on June 27, 1979. Given this fact, it is

hard to see how petitioners can seriously maintain that the

district judge made a “final determination” as to their

alleged Weber right to settle.

Assuming, arguendo, that the District Court’s order was

a final determination as claimed by petitioners, immediate

remedies were available which negate any claim of irrep

arable harm in having to await post-judgment review.

Where a district court clearly abuses its discretion in re

jecting a proposed consent decree, a writ of mandamus

under 28 U.S.C. § 1651 (1976) and Fed.R.App.P. 21 (a)

provides interlocutory review. See Axim & Sons Lumber

Co. v. Long Island Rail Road Co., No. 79-3082 slip

op. (2d Cir., August 11, 1980); Rodgers v. U. S. Steel

Corp., 541 F.2d 365, 372 (3d Cir. 1976). Another means

of obtaining prompt review exists under the Interlocutory

Appeals Act of 1958, 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b), which permits

interlocutory review of a controlling and unsettled question

of law where “an immediate appeal from the order may

materially advance the ultimate termination of the litiga

tion, . . .” 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) (1976).12 See, e.g., Ruiz v.

Estelle, 609 F.2d 118, 119 (5th Cir. 1980). 12

12 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b) provides:

When a district judge, in making in a civil action an order

not otherwise appealable under this section, shall be of the

opinion that such order involves a controlling question of law

as to which there is substantial ground for difference of opinion

and that an immediate appeal from the order may materially

advance the ultimate termination of the litigation, he shall so

state in writing in such order. The Court of Appeals may there

upon, in its discretion, permit an appeal to be taken from such

order, if application is made to it within ten days after the entry

of the order: Provided, however, That application for an ap

peal hereunder shall not stay proceedings in the district court

unless the district judge or the Court of Appeals or a judge

thereof shall so order.

21

The final reason stated by petitioners in support of their

claim of irreparable harm is that “there would be no way in

which the parties, despite whatever might be done upon re

view of final judgment, could retrieve the advantages which

a settlement would have brought” (Pet. Br. at 42). It is

unclear what petitioners mean by “advantages,” but what

ever is intended, this reason does not rise to the level of

irreparable harm as claimed by petitioners and, in fact, when

analyzed, shows why there should be no exception to the

finality rule for an order denying entry of a consent decree.

“Advantages” may mean the injunctive relief which was

contemplated by the decree. If so, and the District Court

did abuse its discretion in declining to enter the order, that

advantage would be retrievable on post-judgment review.

On the other hand, if “advantages” means the loss of the

opportunity to avoid the time and expense of further liti

gation, the facts of this case show that allowing immediate

appeal from an order denying entry of a consent decree

does not assure preservation of that advantage. Had the

matter remained with the District Court, it could have been

tried as early as June 1977. The parties’ time and expense

would be considerably less than has been incurred through

the appellate procedure. This is also true had the matter

been tried at the second trial date, February 4, 1980, fol

lowing remand from the Court of Appeals. As it is, what

ever decision is made on the procedural issue before this

Court, resolution of the matter is still a long way off and

at much greater expenditure of time and money than if the

case had gone to trial or been resolved otherwise at a

much earlier date.

These observations are particularly significant here

where the theory now advocated by petitioners—a Weber

right to settle—only arose during the course of the appellate

22

process. This highlights the danger that allowing immediate

appeals from refusals to enter consent decrees will stimulate

parties to take appeals, in the hope that future developments

in the law will help their cause. Such tactics will clog appel

late calendars, delay resolution of cases, and force appellate

courts to “authoritatively opine about important unsettled

legal issues of the highest social concern” (Carson v. Amer

ican Brands, Inc., supra, 606 F.2d at 424) without de

velopment of proper factual records and argument. These

results would bring to realization the concern of this Court

in Coopers & Lybrand V. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. at 476,

that allowing immediate appeal from non-final orders

“thrusts appellate courts indiscriminately into the trial proc

ess” and “defeats one vital purpose of the final judgment

rule,” that is, preserving the dichotomy of trial and appellate

functions established for the respective courts and critical to

the smooth operation of any judicial system.

In sum, the order here is effectively reviewable on ap

peal. There is no irreparable harm in postponing appellate

review until after final judgment. To the extent there is

any doubt about the effectiveness of post-judgment review,

it must be resolved against appealability in this case when

examined in the light of the important competing interests

of weighing “the inconvenience and costs of piecemeal re

view on the one hand and the danger of denying justice by

delay on the other.” Dickinson v. Petroleum Conversion

Corp., 338 U.S. 507, 511 (1950).

Accordingly, the District Court’s order refusing entry of

the proposed consent decree meets none of the prongs of the

test for applicability of the collateral order doctrine. To

allow an interlocutory appeal here would strip § 1291 of all

significance. The Court of Appeals was correct in deter

mining (606 F.2d at 424):

23

We think this Title VII interlocutory appeal should

be dismissed. Our review of this pretrial order has

halted the litigation for over two years pending review

of the district court’s exercise of discretion. Given this

disruption and the difficult burden on appeal of demon

strating an abuse of discretion, plaintiffs have identified

no consequence requiring appellate review before final

judgment. We perceive none. Instead, we think our

review is best left to follow final judgment.

D. The Reasoning Of The Ninth Circuit In

Norman v. McKee Is Not Persuasive

Petitioners and the Amici urge that the Ninth Circuit’s

opinion in Norman v. McKee, 431 F.2d 769 (1970), cert,

denied, 401 U.S. 912 (1971), is in conflict with the decision

of the Court of Appeals below and with Seigal v. Merrick,

590 F.2d 35 (2d Or. 1978), and they argue that Norman

states the better rale, i.e., that orders refusing settlements of

class action cases are appealable collateral orders.13 Norman

is not persuasive here for a number of reasons.

First of all, the Norman case was decided in 1970, some

eight years before this Court’s decision in Coopers & Ly

brand v. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. 463, and the Ninth

Circuit did not have the benefit of this Court’s further ex

planation of the collateral order doctrine as set forth in that

case. The Second Circuit’s decision in Seigal was thus better

reasoned than Norman because it considered the Coopers &

Lybrand decision.

Secondly, this Court’s focus in Coopers & Lybrand was

on the subjective economic factors which had evolved in

13 As noted, supra, n.4, the Court of Appeals below did not pass

upon the applicability of the collateral order doctrine to the District

Court’s June 1, 1977 order refusing entry of the tendered consent

decree.

24

the courts below for determining under the “death knell”

doctrine when a refusal to certify a class action was or was

not appealable. The concern was that “[ujnder the ‘death

knell’ doctrine, appealability turns on the court’s perception

of [the economic] impact in the individual case.” Coopers &

Lybrand v. Livesay, supra, 437 U.S. at 470-71. The Court

observed (id. at 473):

A threshold inquiry of this kind may, it is true, iden

tify some orders that would truly end the litigation prior

to final judgment; allowing an immediate appeal from

those orders may enhance the quality of justice af

forded a few litigants. But this incremental benefit is

outweighed by the impact of such an individualized

jurisdictional inquiry on the judicial system’s overall

capacity to administer justice.

Norman turned on just such an economic, “individualized

jurisdictional inquiry.” Having noted that “stockholder de

rivative suits and class actions generally present complex

questions and involve large numbers of exhibits and wit

nesses,” the Norman court then concluded (431 F.2d at

779):

The present case is a good example. The trial would

be lengthy and expensive. In this situation, therefore,

we think that the cost and delay of the piecemeal re

view, as balancing factors, are diminished in impor

tance. . ..

Based on such economic factors, the Norman court ruled

in favor of immediate appeal from an order denying entry

of a consent decree. Had the matter in Norman not involved

a “lengthy and expensive” trial, the result could well have

been different. Such an individualized, economic approach

25

to appealability runs contrary to the Coopers & Lybrand

analysis.14

The decision in Norman has also been properly criticized

for its failure to recognize that judicial review of a pro

posed settlement is not devoid of some examination of the

underlying cause of action, In re General Motors Corp.

Engine Interchange Litigation, 594 F.2d 1106, 1119 (7th

Cir. 1979).15 As the Court of Appeals below stated, quot

ing Seigal v. Merrick, supra, 590 F.2d at 37 (Carson v.

American Brands, Inc., 606 F.2d at 423):

[A]n order disapproving a settlement. . .is based, in

part, upon an assessment of the merit of the positions

of the respective parties, and permits the parties to

proceed with the litigation or to propose a different

settlement.

14 The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit focused on this

length of trial-cost factor analysis in explaining, in part, why they

“must differ with our friends on the Ninth Circuit,” by observing

(Seigal v. Merrick, 590 F.2d at 39):

In Norman v. McKee, the court emphasized that a trial would

be expensive and lengthy and that, hence, the cost and delay of

piece-meal review, as balancing factors, were diminished in im

portance.

15 This decision allowed an appeal from a district court order

approving a settlement and turned on facts peculiar to that case.

Further, the Seventh Circuit correctly recognized the distinction

between an approval of a settlement and a disapproval for purposes

of appealability under the collateral order doctrine (id. at 1119, n.

15):

In the case at bar, the trial court’s approval of the subclass

settlement does not lead directly to final judgment. But unlike

a disapproval of a settlement, the trial court’s order looks

toward neither a renewal of settlement negotiations nor a trial

on the merits. Thus, the danger of appellate court interference

with proceedings before the trial court is small in comparison

with the danger of denying justice by delay. (Emphasis added.)

For these reasons, the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Norman

is unpersuasive here.

II.

The District Court’s Order Refusing Entry Of The Consent Decree

Is Not Appealable Under The Congressionally Created

Exception To The Finality Sale, 28 U.S.C. § 1292 (a)(1)

A. As A Narrow Exception To The Final Judgment Rule,

Section 1292(a)(1) Should Be Strictly Construed

When the pressure for appealability of certain interlocu

tory orders “rises to a point that influences Congress, legis

lative remedies are enacted.” Baltimore Contractors, Inc.

v. Bodinger, 348 U.S. 176, 181 (1955). These legislative

remedies, such as the device of certification under § 1292

(b), explored, supra, at 20, create exceptions to the “long-

established policy against piecemeal appeals, which this

Court is not authorized to enlarge or extend.” Gardner v.

Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., 437 U.S. 478, 480 (1978).

The Court of Appeals dismissed this appeal on the

ground that the District Court’s order was not appealable

under one of these legislative remedies, 28 U.S.C. § 1292

(a)(1) , which allows appeal from “[ijnterlocutory orders

. . . granting, continuing, modifying, refusing or dissolving

injunctions, or refusing to dissolve or modify injunc

tions. . . . ”

Petitioners and Amici contend, however, that the order

rejecting the consent decree is appealable under this statu

tory exception because some terms of the decree involved

injunctive-type relief, bringing the order within the literal

“refusing . . . injunctions” language of § 1292(a) (1). Even

if this were so, however, a literal interpretation of an order

as one “refusing” an “injunction” simply because it involves

27

injunctive relief only begins the inquiry into appealability

under § 1292(a) (1). As the Court of Appeals below prop

erly observed, “[a] mere labelling of relief is not sufficient.”

606 F.2d at 422 (citing City of Morgantown, W. Va. v.

Royal Insurance Co., 337 U.S. 254, 258 (1949)).

Rather than apply a literal approach to § 1292(a)(1)

that could make immediately appealable any pre-trial order

involving claims for injunctive relief, this Court has cau

tioned that the statute should be approached “somewhat

gingerly lest a floodgate be opened that brings into the

exception many pre-trial orders.” Switzerland Cheese Asso

ciation v. E. Horne’s Market, Inc., 385 U.S. 23, 24 (1966).

Thus, its scope is “a narrow one . . . keyed to the ‘need to

permit litigants to effectually challenge interlocutory orders

of serious, perhaps irreparable, consequence’.” Gardner v.

Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., supra, 437 U.S. at 480,

quoting from Baltimore Contractors, Inc. v. Bodinger,

supra, 348 U.S. at 181.

The decision of the Court of Appeals below was the first

which analyzed the issue of appealability of an order deny

ing a consent decree under § 1292(a)(1), and in holding

such an order to be outside the statute, the Court of Ap

peals was cognizant of this Court’s cautious approach to

expanding appealability. While this matter was pending on

petition for writ of certiorari, however, the Court of Ap

peals for the Fifth Circuit seems to have reached a contrary

result. United States v. City of Alexandria, 614 F,2d 1358,

1361 n.5 (5th Cir. 1980). Analysis demonstrates that no

“serious, perhaps irreparable, consequence[s]” flow from

postponing review of the District Court’s order in this case

and that the better view was that followed by the Court of

Appeals below, not that of the Fifth Circuit.18 16

16 The Fifth Circuit’s opinion in City of Alexandria is treated,

infra, at 36-39.

28

B. The Rejection Of The Tendered Decree Did Not Cause

Irreparable Consequences Which Can Be Alleviated

Only Through Allowance Of Interlocutory Appeal

In Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., supra,

this Court held that an order denying class certification

under Rule 23 was not appealable under § 1292(a)(1),

even though the practical effect of the order was to tenta

tively refuse a portion of the injunctive relief sought in the

complaint. The order in Gardner did not have the direct or

irreparable effect necessary for § 1292(a) (1) appealability

because (437 U.S. at 480-81):

[i]t could be reviewed both prior to and after final

judgment; it did not affect the merits of petitioner’s

own claim; and it did not pass on the legal sufficiency

of any claims for injunctive relief. (Footnote omitted.)

The District Court’s order refusing entry of the proposed

consent decree was precisely of the same effect as the order

denying class certification in Gardner, and is therefore also

not appealable under § 1292(a) (1).

1. The Order Could Be Reviewed Both Prior To And

After Final Judgment

The District Court’s rejection of the tendered consent

decree did not affect petitioners’ ability to obtain injunctive

relief at a later stage in the proceedings. As the Court of

Appeals for the District of Columbia has stated, in

a case cited with approval by this Court in Sampson v.

Murray, 416 U.S. 61, 90 (1974), “[t]he possibility that

adequate . . . corrective relief will be available at a later

date . . . weighs heavily against a claim of Irreparable

harm.” Virginia Petroleum Jobbers Association v. Federal

Power Commission, 259 F.2d 921, 925 (D.C. Cir. 1958).

In this case, petitioners remained fully able to obtain in

29

junctive relief at any of three later stages—prior to trial, at

trial or through a post-judgment appeal.

The most immediate means of obtaining injunctive relief

short of trial would have been an alternative consent decree.

The District Court’s order simply rejected the particular

consent decree which was tendered. The parties could have

tendered another consent decree, either admitting different

facts or awarding different relief, which may well have

been approved by the District Court. As the Court of Ap

peals for the Second Circuit has noted, “the denial of one

compromise does not necessarily mean that a ‘sweetened’

compromise may not be approved.” Seigal v. Merrick, supra,

590F.2d at 39.

The contention that the “tenor” of the District Court’s

opinion (Pet. Br. at 41) “effectively deniefd] petitioners and

respondents alike the opportunity to settle their dispute vol

untarily” (Br. of U.S. at 10) is unavailing. As the Court of

Appeals observed, the parties could have presented the same

or alternative proposals at any stage in the proceedings

(606 F.2d at 424):

When a district court objects to the terms of a de

cree, alternative provisions can be presented, and per

haps a disapproved decree may be entered with further

development of the record. If the district court refuses

a decree because it is presented too early in the litiga

tion, it may be later approved, perhaps following a

decisive vote by class members. Whatever the district

court’s reasons for refusing a decree, appeals of right

from those refusals would encourage an endless string

of appeals and destroy the district court’s supervision

of the action as contemplated by Fed.R.Civ.Proc.

23(e).

Thus, petitioners’ assumption that all possibility of set

tlement was foreclosed is mere speculation. Even assuming,

30

however, that the parties were unable to negotiate an al

ternative settlement, there remained other means of obtain

ing injunctive relief short of trial and post-judgment review.

If the trial court clearly abused its discretion, a writ of

mandamus would provide immediate review. Rodgers v.

U.S. Steel Corp., 541 F.2d 365, 372 (3d Cir. 1976). If one

or more of the parties believed that the District Court’s de

termination involved controlling and unsettled questions of

law, resolution of which might materially advance the litiga

tion, a request for certification under 28 U.S.C. § 1292(b)

could have been made. Ruiz v. Estelle, 609 F.2d 118, 119

(5th Cir. 1980). Petitioners attempted neither mandamus

nor § 1292(b) certification. However, accepting as true the

alleged errors of the District Court set forth by petitioners,

either mandamus or § 1292(b) could have provided effec

tive avenues of relief.

Further, although petitioners contend that the District

Court’s rejection of the decree “precluded a subsequent mo

tion” by them for “a preliminary injunction granting all,

or part, of the relief specified in the proposed consent de

cree,” (Pet. Br. at 64), nothing in the District Court’s opin

ion precluded any such application. Had petitioners made

application for preliminary injunctive relief, the District

Court would necessarily have undertaken de novo con

sideration of the grounds alleged in support. The stipulations

that had been of special concern to the District Court

when it reviewed the proposed decree17 would have merited

no consideration in the Court’s assessment of “the existence

of a substantial likelihood that [petitioners] will ultimately

17 For example, the District Court noted in rejecting the decree

that it was particularly concerned with respondents’ express denial

of unlawful conduct and petitioners’ failure to deny respondents’

assertion (see 446 F.Supp. at 788-89) and with the decree’s addi

tional stipulation that “the Court finds . . . that there are no dis

criminatory hiring practices at [Leaf]” (id. at 783).

31

prevail on the merits” (Pet. Br. at 64-65). Since nothing

foreclosed petitioners from applying for injunctive relief

and establishing any facts necessary for such relief, the

District Court’s order did not once and for all deny peti

tioners “the protection of the injunction prayed . . .” Gen

eral Electric Co. v. Marvel Rare Metals Co., 287 U.S. 430,

433 (1932). Rather, “[h]ere, injunctive relief was not fi

nally denied; it was merely not granted at this stage in the

proceedings.” Carson v. American Brands, Inc., supra. 606

F.2d at 423.

The combination of District Court reconsideration of the

proposed order, consideration of an application for a pre

liminary injunction or of another settlement proposal, the

opportunities noted above for expedited interlocutory re

view, and effective appellate review after final judgment

renders unsupportable any claim herein of “irreparable in

jury.” It is not necessary to open the floodgates by judicial

expansion of § 1292(a)(1). Like the denial of class cer

tification in Gardner, the District Court’s initial rejection of

a consent decree produces no “ ‘irreparable’ effect” because

its order “could be reviewed both prior to and after final

judgment.” Gardner v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co.,

supra, 437 U.S. at 478.

2. The Order Did Not Affect Or Pass On The Legal

Sufficiency Of Any Claims For Injunctive Relief

Nor can it be established that the District Court’s order

caused a direct or irreparable effect by “affectfing] the

merits” of petitioners’ claims for injunctive relief and “pass-

ting] on the legal sufficiency” of any such claims. Gardner

v. Westinghouse Broadcasting Co., supra, 437 U.S. at 481.

In an effort to show the necessary “serious, perhaps ir

reparable” effect, petitioners, as they submit under their

collateral order argument, again maintain that the District

32

Court’s order “concerns [their] right under Title VII as

well as the parties’ right to institute an affirmative action

plan” in conformance with the Weber decision (Pet. Br. at

66-67 n.21), and that “the order of the district court was

based entirely upon its misapprehension of applicable legal

principles.” (Id. at 71).ls

18 Petitioners’ argument of irreparable injury by denial of a

“Weber-type” right in support of their claim of appealability under

§ 1292(a)(1) seriously undermines their alternative position that

the District Court’s order was a “collateral order” under Cohen v.

Beneficial Indus. Loan Corp., supra, and its progeny. Petitioners

must meet the almost impossible task of establishing that one court

order “passfed] on the legal sufficiency of [their] claims” (Gardner,

supra) (§ 1292(a)(1)) and was at the same time “separate and

independent” of their claims (collateral order) (§ 1291). They

attempt to reconcile these “apparently inconsistent positions” by

stating that the two appealability positions “involve different rights,”

(Pet. Br. at 66-67 n.21):

With respect to the appealability of the order below as a

collateral order, the right affected is the parties’ right to settle

the case, prior to trial, in accordance with standards set forth

in Weber, supra. This right is, of course, separate and inde

pendent of the right sued upon pursuant to Title VII.

On the other hand, the right affected with respect to the

refusal of an injunction concerns petitioner’s [sic] right under

Title VII as well as the parties’ right to institute an affirmative

action plan. The former, of course, is exactly the right sued

upon and therefore an order adversely affecting it touches on the

merits of the action. (Emphasis in original.)

This attempt at reconciliation fails. Since the proposed consent de

cree was rejected in part because of the District Court’s preliminary

determination that the petitioners’ claims would not support the pro

posed relief under Title VII, it is obvious that the decision was in

extricably linked to the merits of the main claims. Hence the order

rejecting the consent decree cannot, in this case, be “separate and

independent” of the Title VII claim for purposes of establishing

appealability under the collateral order doctrine.

It stands to reason that a single court order cannot simultaneously

be “collateral to” the claim, as required by the collateral order doc

trine, while at the same time “affect[ing] the merits” of petitioners’

claims and “passing] on the legal sufficiency of any claims for in

junctive relief,” as required for appealability under § 1292(a)(1).

33

These claims cannot withstand scrutiny for several rea

sons. First, as noted in the collateral order section, supra,

at 10-15, whether a right exists under Weber to “institute

an affirmative action plan” by way of settlement of a Title

VII action is an issue simply not briefed, argued or ad

dressed by the courts below, nor yet addressed by this Court,

and indeed is encompassed within the “abuse of discretion”

questions specifically denied review in this case.

Second, whatever such Weber “settlement rights” may ul

timately be discerned, they most certainly did not exist in

June 1977 when the District Court made Its determination.

Had petitioners desired reconsideration of this order in light

of Weber, they were free to so move when the case returned

to the District Court. Yet they made no attempt to obtain

reconsideration despite the plain invitation of the Court of

Appeals to do so.

Third, assuming that such a “right to settle” a Title VII

case pursuant to Weber came into existence after the District

Court’s decision, petitioners would have this Court enlarge

the narrow final judgment statutory exception to encompass

immediate appeal and review in circumstances where no

clear mistake of law was made by the District Court but

subsequent changes in the law become the issue on appeal.

Such an expansion could open the floodgates to appeal based

on predicted or anticipated rights and render nugatory the

strict showing of “serious, perhaps irreparable” injury re

quired by § 1292(a)(1).

Accordingly, the applicability of Weber to petitioners’

(Cont. from preceding page)

Gardner, supra, 437 U.S. at 480-81 (footnote omitted). Such schizo

phrenic characterization of a single court order further illuminates

the wisdom of this Court’s policy of narrowly interpreting the general

rule of finality and letting “[t]he choices fall in the legislative do

main.” Baltimore Contractors v. Bodinger, supra, 348 U.S. at 181-82.

34

claim of irreparable injury for purposes of establishing ap

pealability is dubious. Petitioners, however, further contend

that denial of interlocutory appeal poses “the danger of

serious h am ” (Pet. Br. at 72) since the District Court’s

order “as a practical matter, denied injunctive relief to

petitioners on the ground that their claim was legally in

sufficient,” (id. at 73), and “settle[d], or tentatively de

cide! d], the merits of petitioners’ claims on the merits” (id.