USA v Smith Brief of Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 15, 1998

73 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. USA v Smith Brief of Appellants, 1998. fddbadcd-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/205c157e-4adb-4f24-b25f-2b2b51e36cae/usa-v-smith-brief-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

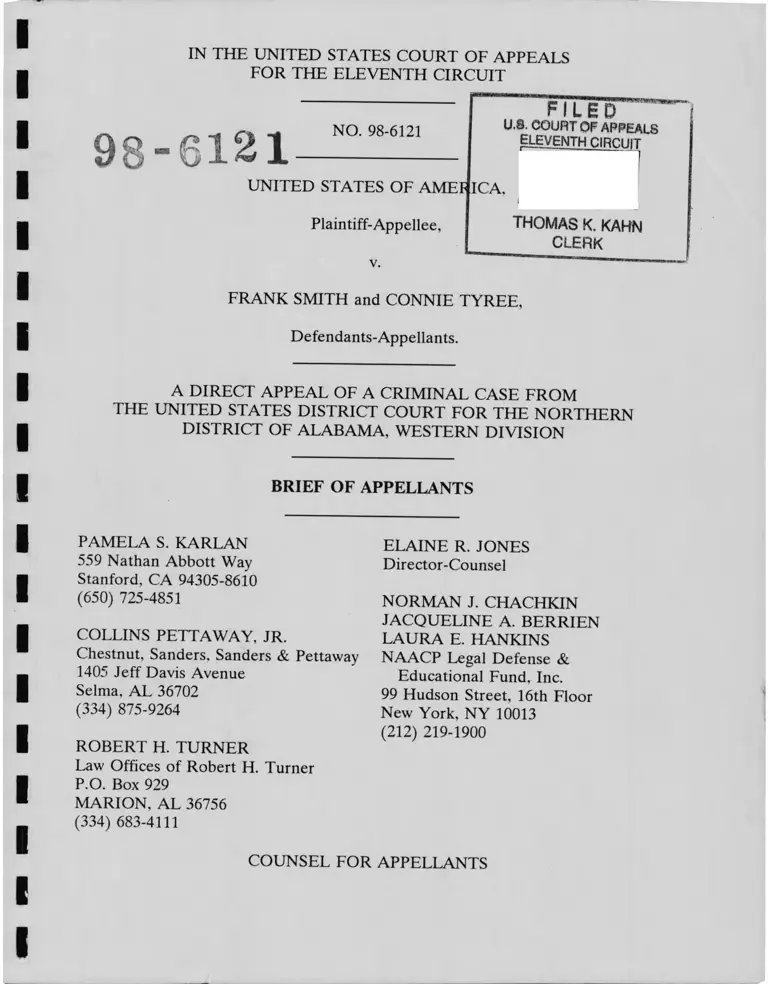

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

9 8 - 6 1 2 1

NO. 98-6121

UNITED STATES OF AMEF ICA,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

filed

U.8. COURT OF APPEALS

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

THOMAS K. KAHN

CLERK

v.

FRANK SMITH and CONNIE TYREE,

Defendants-Appellants.

A DIRECT APPEAL OF A CRIMINAL CASE FROM

THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN

DISTRICT OF ALABAMA, WESTERN DIVISION

BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

PAMELA S. KARLAN

559 Nathan Abbott Way

Stanford, CA 94305-8610

(650) 725-4851

COLLINS PETTAWAY, JR.

Chestnut, Sanders, Sanders & Pettaway

1405 Jeff Davis Avenue

Selma, AL 36702

(334) 875-9264

ROBERT H. TURNER

Law Offices of Robert H. Turner

P.O. Box 929

MARION, AL 36756

(334) 683-4111

ELAINE R. JONES

Director-Counsel

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JACQUELINE A. BERRIEN

LAURA E. HANKINS

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

COUNSEL FOR APPELLANTS

NO. 98-6121 UNITED STATES v. SMITH & TYREE

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel of record hereby certifies that the following

persons have an interest in the outcome of this case:

1. Patrick Samuel Arrington (counsel at the selective prosecution

hearing for appellant Smith)

2. Jacqueline A. Berrien (appellate counsel for appellants)

3. Shelton Braggs (alleged victim)

4. Gregory M. Biggs (Special Assistant United States Attorney; trial

counsel for appellee)

5. Willie C. Carter, Jr. (alleged victim)

6. Cassandra Lee Carter (alleged victim)

7. Norman J. Chachkin (appellate counsel for appellants)

8. Chestnut, Sanders, Sanders & Pettaway, P.C. (pretrial, trial, and

appellate counsel for appellant Tyree)

9. Eddie T. Gilmore (alleged victim)

10. Laura E. Hankins (appellate counsel for appellants)

11. Angela Hill (alleged victim)

12. Michael Hunter (alleged victim)

13. Elaine R. Jones (appellate counsel for appellants)

Cl-of 3

l

NO. 98-6121 UNITED STATES v. SMITH & TYREE

14. Pamela S. Karlan (appellate counsel for appellants)

15. Law Offices of Robert H. Turner (pretrial, trial, and appellate

counsel for appellant Smith)

16. J. Patton Meadows (Assistant United States Attorney; trial coun

sel for appellee)

17. NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (appellate coun

sel for appellants)

18. Office of the United States Attorney for the Northern District of

Alabama (counsel for appellee)

19. Collins Pettaway, Jr. (pretrial, trial, and appellate counsel for

appellant Tyree)

20. Sam Powell (alleged victim)

21. Caryl Privett (United States Attorney; counsel at the selective

prosecution hearing for appellee)

22. The Honorable T. Michael Putnam (magistrate judge; presided

over the selective prosecution hearing)

23. The Honorable C. Lynwood Smith, Jr. (trial judge)

24. Frank Smith (defendant-appellant)

C2-of 3

li

NO. 98-6121 UNITED STATES v. SMITH & TYREE

25.

26.

27.

Robert H. Turner (pretrial, trial, and appellate counsel for appel

lant Smith)

Connie Tyree (defendant-appellant)

Marvin W. Wiggins (counsel at the selective prosecution hearing

for appellant Tyree)

C3-of 3

in

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Appellants ask for oral argument in this matter. This case presents

several complex legal and factual claims regarding an election-related prosecu

tion in Greene County, Alabama. This case presents a substantial claim of

selective prosecution (which was the subject of an extensive evidentiary hear-

ing), as well as legal questions of first impression regarding the proper con

struction of a relatively little-used criminal statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1973i, its rela

tionship to state law, and the application of the sentencing guidelines to con

victions under section 1973i. Appellants believe that this Court’s understand

ing would be greatly assisted by oral argument.

IV

CERTIFICATE OF TYPE SIZE AND STYLE

Pursuant to this Court’s Rule 28-2(d), counsel for appellants state that

the size and style of type used in this brief is WordPerfect Dutch Roman

(scalable) 14 point.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Certificate of Interested Persons ...................................................................... j

Statement Regarding Oral A rgum ent............................................................. jv

Certificate of Type Size and Style ................................................................... v

Table of C on ten ts........................................................................................... ^

Table of C ita tions.......................................................................................... ^

Statement of Jurisdiction ................................................................................. xy

Statement of the Is su e s ................................................................................ 1

Statement of the C a se ............................................................................. 2

Course of the Proceedings .................................................................... 3

Statement of F a c ts .................................................................................... 4

1. The decision to prosecute Frank Smith and Connie Tyree 6

2. Racial bias in the selection of the j u r y ............................. 11

3. The evidence at t r i a l ............................................................ 12

Standard of Review ............................................................................. 20

Summary of the Argument ........................................................................... 23

A rgum ent.............................................................................................. 25

I. The Indictment in this Case Should Be Dismissed

Because the Government Engaged in Racially and

Politically Selective Prosecution ........................................................ 25

Page

vi

Table of Contents {continued)

A. The Magistrate Judge Used the Wrong Legal

Standard for Determining Whether Similarly

Situated Individuals Had Not Been Prosecuted ................... 26

B. The Magistrate Judge Made Several Legal

Errors in Assessing the Evidence of

Discriminatory Purpose ............................................................ 28

C. The Government’s Behavior at Trial Provides

Additional Compelling Evidence of its

Discriminatory In te n t................................................................. 31

II. There Was Insufficient Evidence to Convict Appellant

Tyree on Counts 12 and 1 3 ................................................................. 32

III. Appellants’ Sentences Violated the Sentencing Guidelines .......... 34

A. The District Court Chose the Wrong Base Offense

Level ................................................................... 34

B. The District Court Erred in Enhancing

Appellant Tyree’s Sentence for Abuse of T r u s t ................... 36

C. The District Court Erred in Enhancing Appellant

Smith’s Sentence for Obstruction of Ju s tice ........................... 40

Page

Argument (continued)

vii

Table of Contents (continued)

D. The District Court Erred in Enhancing Appellants’

Sentences Because of Their Roles in the O ffenses.................41

IV. Appellants Were Improperly Convicted on

Multiplicitous C o u n ts ........................................................................... 43

V. Appellants Were Prejudiced by the Improper

Admission and Use of Evidence Regarding Other

Absentee Ballots .................................................................................. 45

VI. The District Court’s Charge Regarding "Proxy Voting"

Permitted the Jury to Convict Appellants Without Finding

Lack of Consent Beyond a Reasonable D o u b t ............................... 49

VII. Appellant Tyree Was Denied Her Constitutional Right

To Present Witnesses in Her D e fe n se .............................................. 51

A. The Government Substantially Interfered With

Burnette Hutton’s Decision Whether to Testify

on Appellants’ Behalf ............................................................... 51

B. Under the Circumstances, the District Court

Abused Its Discretion in Excluding Hutton’s

Prior Testim ony............................................................ .............. 53

Page

Argument (continued)

viii

Table of Contents {continued)

C onclusion..................................................................................................... 54

Certificate of Service............................................................ following page 55

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases’.

Anderson v. United States, 417 U.S. 211 (1974) ......................................... 35

Batson v. Kentucky, 476 U.S. 79 (1986)..................................................... 2, 3

Bonner v. City o f Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir. 1981)

(en banc) ....................................................................................................

Cooter & Gell v. Hartmarx Corp., 496 U.S. 384 (1 9 9 0 )............................. 48

Hadnott v. Amos, 394 U.S. 358 (1969) .......................................................... 5

Hardy v. Wallace, 603 F. Supp. 174 (N.D. Ala. 1985)

(three-judge court) . .............................................................................. 5

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973) .................................. 32

Parr v. Woodmen o f the World Life Ins. Co., 791 F.2d

888 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 6 )............................................................................. 30

Swam v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 (1965).......................................................... 2

Smith v. Meese, 821 F.2d 1484 (11th Cir. 1 9 8 7 ).................................... 46-47

Page

IX

Taylor v. Cox, 710 So. 2d 406 (Ala. 1 9 9 8 )................................................... 50

United States v. Alpert, 28 F.3d 1104 (11th Cir. 1994) . . . .......................... 40

* United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456 (1996)...................... 25, 27, 28, 29

*United States v. Barakat, 130 F.3d 1448 (11th Cir. 1997) ............ 21, 38, 39

United States v. Benny, 786 F.2d 1410 (9th Cir.), cert.

denied, 479 U.S. 1017 (1986)............................................................... 21

United States v. Blackwell, 694 F.2d 1325 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 8 2 ) ............ .. 52, 53

-4,

United States v. Blum, 62 F.3d 63 (2d Cir. 1995) ....................................... 22

United States v. Bowman, 636 F.2d 1003 (5th Cir. 1981)............................ 35

United States v. Deeb, 13 F.3d 1532 (11th Cir. 1994),

cert, denied, 513 U.S. 1146 (1995) ..................................................... 23

United States v. Dunnigan, 507 U.S. 87 (1993) ............................................ 40

* United States v. Garrison, 133 F.3d 831 (11th Cir. 1998)............... 21, 37, 38

United States v. Goodwin, 625 F.2d 693 (5th Cir. 1980) ........................... 52

* United States v. Gordon, 817 F.2d 1538 (11th Cir. 1987),

cert, dismissed, 487 U.S. 1265 (1988) . . . . 2, 5, 20, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29

United States v. Grubbs, 829 F.2d 18 (8th Cir. 1987) ............................. 43n

Table of Citations (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

x

Table of Citations (continued)

United States v. Guerrero, 650 F.2d 728 (5th Cir. 1981) ........................... 48

United States v. Hammond, 598 F.2d 1008 (5th Cir. 1979) ...................... 51

United States v. Henricksen, 564 F.2d 197 (5th Cir. 19 7 7 )................. 22, 52

United States v. Hubert, 138 F.3d 912 (11th Cir. 1998) ............................. 40

United States v. Jones, 52 F.3d 924 (11th Cir.), cert.

denied, 516 U.S. 902 (1995)................................................................. 20

United States v. Langford, 946 F.2d 798 (11th Cir. 1991),

cert, denied, 503 U.S. 960 (1992) ............................................ 44, 45, 46

United States v. Lumley, 135 F.3d 758 (11th Cir. 1998)...................... 21, 22

United States v. Quinn, 123 F.3d 1415 (11th Cir. 1997),

cert, denied, 118 S. Ct. 1203 (1998) ................................................ 20n

United States v. Schlei, 122 F.3d 944 (11th Cir. 1997),

cert, denied, 118 S. Ct. 1523 (1998) ................................................... 22

United States v. Sirang, 70 F.3d 588 (11th Cir. 1995) ........................

United States v. Tapia, 59 F.3d 1137 (11th Cir.), cert.

denied, 516 U.S. 1001 (1995)............................................................... 21

Page

Cases (continued):

xi

Table of Citations (continued)

United States v. Tokars, 95 F.3d 1520 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 6 )......................... 21, 22

United States v. Veltmann, 6 F.3d 1483 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 3 )........................... 48

Washington v. Texas, 388 U.S. 14 (1967)..................................................... 51

*Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598 (1985).................................... 25, 28, 30

Webb v. Texas, 409 U.S. 95 (1972) ............................................................... 52

Statutes

15 U.S.C. § 78j (1994)..................................................................................... 44

15 U.S.C. § 78ff (1994) .................................................................................. 44

18 U.S.C. § 371 (1994) .................................................................................... 3

18 U.S.C. § 1341 (1994) ................................................................................ 44

28 U.S.C. § 1291 (1994) ................................................................................ xv

42 U.S.C. § 1973i (1994) ........................................................ iv, 23, 24, 45, 50

42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c) (1 9 9 4 ).............................................. 3, 21, 35, 43, 44, 45

42 U.S.C. § 1973i(e) (19 9 4 )......................................................................... 3? 35

42 U.S.C. § 1973/(c)(l) (1994 )...................................................................... 45

Ala. Code § 17-10-7 ......................................................................................... 9

Ala. Code § 17-10-9 ....................................................................................... 13

Page

Cases (continued):

Xll

Table of Citations (continued)

Other Materials

Fed. R. App. P. 4 ....................................................................................... .. xv

Fed. R. Evid. 804(b)(1)........................................................................... 19, 53

1997 County and City Extra: Annual Metro, City, and

County Data Book (George E. Hall and Deirdre A.

Gacquin eds. 1997)........................................................................... 5n, 9

Kenneth J. Melilli, Batson in Practice: What We Have

Learned About Batson and Peremptory Challenges,

71 Notre Dame L. Rev. 447 (1996) ................................................... 31

Nomination o f Jefferson B. Sessions, III, to be U.S

District Judge for the Southern District o f Alabama'.

Hearings Before the Sen. Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1986)......................................................................................... 7

Michael J. Raphael & Edwards J. Ungvarsky, Excuses,

Excuses: Neutral Explanations Under Batson v.

Kentucky, 27 U. Mich. J.L. Ref. 229 (1 9 9 3 )............................... 31-32

Joshua E. Swift, Note, Batson’s Invidious Legacy:

Discriminatory Juror Exclusion and the "Intuitive"

Peremptory Challenge, 78 Cornell L. Rev. 336 (1993) ................... 32

Page

xiii

Table of Citations (continued)

Page

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual (1997) . . . . 4, 35, 39, 42

Other Materials (continued):

(*) Denotes cases primary relied upon

xiv

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This Court has jurisdiction over this appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291

and Fed. R. App. P. 4. This case involves the direct appeal of criminal

convictions in the United States District Court for the Northern District of

Alabama.

xv

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

1. Whether the government engaged in selective prosecution.

2. Whether there was insufficient evidence to convict appellant Tyree

on Counts 12 and 13.

3. Whether the district court imposed an illegal sentence because it:

(a) chose the wrong Base Offense Level;

(b) improperly enhanced appellant Tyree’s offense level for

abuse of a position of trust;

(c) improperly enhanced appellant Smith’s offense level for

obstruction of justice; and

-4.

(d) improperly enhanced both appellants’ offense levels for their

roles in the offenses.

4. Whether appellants were convicted on multiplicitous counts.

5. Whether appellants suffered unfair prejudice from the introduction

of evidence regarding entirely legal, constitutionally protected conduct.

6. Whether the district court’s instructions to the jury regarding

so-called "proxy" voting permitted the jury to convict appellants without

concluding, beyond a reasonable doubt, that appellants had cast other voters’

ballots without those voters’ permission.

7. Whether appellant Tyree was denied her right under the Fifth and

Sixth Amendment to present witnesses in her defense.

1

STATEMENT OF THE CASK

This case marks a disturbing reappearance of the discriminatory

prosecution of black voting rights activists in Greene County, Alabama. Ten

years ago, this Court found that the government’s prosecutorial decisions in

a similar case suggested a "pattern" of "specifically targeting those counties

where blacks since 1980 had come to control some part of the county

government" and prosecuting only individuals who "were members of the black

majority faction." United States v. Gordon, 817 F.2d 1538, 1540 (11th Cir.

1987), cert, dismissed, 487 U.S. 1265 (1988). The government’s racial

selectivity did not stop at the courthouse door. This Court further noted "a

4.

recurrent pattern of exclusions of black venirepersons" in the government’s

voting fraud prosecutions in Alabama, id. at 1541, that mandated not only a

hearing regarding the then-newly announced rule of Batson v. Kentucky, 476

U.S. 79 (1986), but also a hearing into whether, under "the seminal case of

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202 [(1965)]," id., the U.S. Attorney’s Office was

engaging in the pervasive and systematic exclusion of black citizens.1

The government seems to have learned nothing from its disgraceful

conduct in the 1980’s. Once again, it has targeted black political activists,

1 On remand, the government ultimately dismissed all remaining charges

against Mr. Gordon.

2

launched a massive investigation that produced a set of doubtful and unfounded

charges, pressured witnesses, and violated the central equal protection

command of Batson v. Kentucky. Once again, this Court should intervene to

rein in a prosecution effort that threatens more injury to the basic values of

American democracy than anything the appellants are alleged to have done.

Course of Proceedings

On January 30, 1997, appellants Frank Smith and Connie Tyree were

charged in a thirteen-count indictment with a set of allegations arising out of

the November 8, 1994, general election in Greene County. R l-1. Count 1 of

the indictment charged both appellants with a conspiracy in violation of 18

U.S.C. § 371; count 2 charged both appellants with voting more than once in

violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(e); and counts 3-13 charged one or both

appellants with providing false information for the purpose of establishing

eligibility to vote in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c).

Appellants moved to dismiss the indictment on grounds of selective

prosecution. On the basis of their threshold showing of racial or political

selectivity, Rl-46, Magistrate Judge T. Michael Putnam conducted a five-day

evidentiary hearing. See R10-R14. Ultimately, his report and

recommendation suggested that appellants’ motion be denied, R2-88-29, and

the district court adopted that conclusion, R2-95.

Judge C. Lynwood Smith, Jr., presided over appellants’ jury trial, which

3

lasted from September 8 to September 15,1997. Appellant Smith was convicted

on all seven counts with which he had been charged and appellant Tyree was

convicted on all eleven counts with which she had been charged. See R20-

1348-50. Over appellants’ objection that they had initially been informed prior

to trial that the Base Level for their offenses would be 6, see R22-3-4, the

court concluded that the appropriate Base Level was 12. See id. at 11; U.S.

Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual § 2H2.1(a)(2) (1997). The court

enhanced that Base Level by 6 additional levels for each appellant, yielding

an Offense Level of 18. See R22-12. The court then sentenced each defen

dant to 33 months of imprisonment (the maximum permissible under the

Guideline Imprisonment Range), two years of supervised release, forty hours

of community service, and the required $50.00 per count assessment fee. See

id. at 17-18. Over the United States’ objection, Magistrate Judge Putnam

granted appellants’ motion for release pending appeal, R3-134, and they

remain free on bond.

Statement of Facts

Greene County, Alabama, is one of the most heavily African-American

jurisdictions in the United States. Its population is somewhere between 80

and 92 percent black.2 Like many counties in the Alabama Black Belt,

According to the 1990 Census, Greene County’s population was 80.9

4

Greene has been the site of fiercely waged, racially polarized political contests

since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which began the process

of enfranchising its black citizens. See, e.g., R2-88-3; RIO-65; R13-823. The

pre-existing white political power structure has resisted the black majority’s

pursuit of political power in a variety of ways. See R10-66-68; see also, e.g,

Hadnott v. Amos, 394 U.S. 358, 362-63 (1969) (local probate judge kept

qualified black candidates off the general election ballot through

discriminatory application of unprecleared state election laws); Hardy v.

Wallace, 603 F. Supp. 174, 176-77 (N.D. Ala. 1985) (three-judge court) (soon-

to-be-displaced white state legislators obtained "unprecedented" legislation to

strip soon-to-be-elected black legislators of their appointment power over the

Racing Commission, the county’s largest source of revenue and employment).

Today, the rival blocs might be described as, on one side, a "black majority

faction," Gordon, 817 F.2d at 1540, affiliated with the Alabama New South

Coalition, and, on the other, an ostensibly nonpartisan and biracial group, the

percent black. See 1997 County and City Extra: Annual Metro, City, and County

Data Book 24 (George E. Hall and Deirdre A. Gacquin eds. 1997) (Table B.

States and Counties - Land Area and Population). In his opinion on

appellants’ selective prosecution claim, the Magistrate Judge indicated that

Greene County now "has a 92% African-American population." R2-88-2.

5

political opponents of the black majority faction and backed by most of the

remaining white power structure within the County.

Absentee voting plays a distinctive and critical role in Greene County’s

electoral politics. As the Magistrate Judge found:

Because of the history of violence and intimidation associated with

efforts by African-Americans to exercise their vote, many African-

Americans continued to be uncomfortable going to the polls to

vote, and felt more comfortable voting an absentee ballot in the

privacy of their homes. Due to the unique racial history of voting

in Greene County and perhaps others, absentee voting became a

widespread practice evidenced by a significantly higher rate of

absentee voting in Greene County compared to counties with

predominantly white populations.

R2-88-3. In 1994, 1,429 of the roughly 3,800 votes cast in Greene County

were cast absentee. Id. at 3-4. Fewer than 40 of these were cast by white

voters. Id. at 4.

The 1994 general election for the Greene County Commission was hotly

contested. It pitted candidates supported by the black majority - including

appellant Frank Smith ~ against candidates whose support came from the

Citizens for a Better Greene County. See R10-74-75. Appellant Connie Tyree

was one of Smith’s supporters.

1. The decision to prosecute Frank Smith and Connie Tyree: The

investigation that led to this prosecution began even before the 1994 election,

when politicians in the anti-New South faction contacted the FBI and the U.S.

Citizens for a Better Greene County ("CBGC"), see RIO-70-72, founded by

6

Attorney’s Office to complain about possible voting irregularities. R2-88-8.

Members of the black majority faction also complained, after the election,

about violations committed by their opponents. See, e.g. R14-1004,1006,1012,

1020, 1023-24, 1028, 1034-37; RIO-237; Rll-376; Rll-412. Until October

1995, however, the investigation was essentially "dormant," in part because the

United States District Court for the Southern District of Alabama had

impounded all absentee ballots throughout the state in connection with an

unrelated election dispute. See R2-88-8.

The investigation was revived in the fall of 1995 at the instigation of the

Alabama Attorney General’s Office, which contacted the FBI to ask whether

it was looking into allegations concerning Greene County. Alabama’s

Attorney General at the time was Jefferson Sessions, a white Republican.

RIO-37. In the 1980s, as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of Alabama,

Sessions had been responsible for the unsuccessful prosecutions of black

voting rights activists in Perry County, Alabama; disapproval of his tactics in

that case - which had included bringing a series of charges on which the

government ultimately introduced no evidence, and pressuring elderly black

voters - contributed to the Senate Judiciary Committee’s refusal to confirm

him to a seat on the federal bench. See generally Nomination o f Jefferson B.

Sessions, III, to be U.S District Judge for the Southern District o f Alabama:

Hearings Before the Sen. Judiciary Comm., 99th Cong., 2d Sess. (1986); id. at

7

338 (petition from various black elected officials in Greene County opposing

Sessions’ nomination). As Alabama Attorney General after 1994, Sessions

pursued state-court voting rights prosecutions in two other majority-black

counties, R 10-38, cases which were quite similar to the allegations involved in

Greene County, R12-503-06.3 His office had no investigations of voting rights

improprieties in any majority-white counties, R10-40-42; nor was it

investigating any white activists.

The most readily apparent distinction between the cases Attorney

General Sessions decided to bring in state court and the Greene County case

involves the local forums. In Wilcox and Hale Counties, where the state filed

-4.

indictments in state court, the circuit court judges and local district attorneys

were white;4 in Greene County, by contrast, both the circuit court judge and

3 As might have been expected, given the history of questionable voting-

rights prosecutions in the Alabama Black Belt, mistrust and personality con

flicts between local black elected officials and white state officials hampered

investigation and prosecution. See R2-88-16-17.

And even in Wilcox County, the Attorney General’s Office essentially

bypassed local law enforcement personnel, who were black, in favor of using

their own staff. See R 13-925 (state investigators did not contact the Wilcox

County Sheriff although that is their standard operating procedure).

8

the local prosecutor were black. See R10-40-42. Bringing a prosecution

involving Greene County in federal court had one other clearly foreseeable

consequence: dramatically changing the racial composition of the jury pool.

There are 31 counties in the Northern District of Alabama. 28 U.S.C. § 81(a)

(1994). Greene is the smallest and by far the most heavily African-American

county within the Northern District. In contrast to Greene County, 22 of the

other 30 counties in the Northern District are more than 80 percent white,

and 12 are more than 90 percent white. See 1997 County and City Extra:

Annual Metro, City, and County Data Book at 24, 38. Thus, rather than pre

senting its case to an overwhelmingly black jury in a county where the jurors

were likely to be familiar with the nature of Greene County politics and high

levels of absentee voting, federal prosecution insured an overwhelmingly white

jury pool from counties with a very different structure of absentee voting, a

pool whose members were likely to be unfamiliar with, and suspicious of,

customary Greene County politics.

Under Alabama law, absentee ballots must be witnessed by two

individuals, see Ala. Code § 17-10-7. The federal and state investigators

decided to focus on the approximately 800 absentee ballots that had been

witnessed by persons who had witnessed more than fifteen ballots. Among

those who had witnessed a substantial number of ballots were appellant Tyree,

who had witnessed 166, R2-88-6, and several members of the opposing

9

political camp, including Rosie Carpenter, who witnessed approximately 100,

R14-990, and Lenora Burks and Annie Thomas, id. at 991.

In a sweep reminiscent of the 1980s investigation, agents from the FBI,

the Alabama Bureau of Investigation, and the Attorney General’s Office

fanned out across Greene County to question voters about their ballots. At

times, they melded that investigation with an investigation into recent,

apparently racially motivated, church burnings. While the decision to combine

the investigations might have been made essentially to save manpower and

resources, R2-88-12, its effect was to sow confusion and disquiet within the

black community. R11-252.

At the selective prosecution hearing in this case, substantial lay and

expert testimony was presented, and the Magistrate Judge found, that "a

number of other people, aside from the defendants, may have been involved

in obtaining forged or fraudulent signatures on absentee ballots." R2-88-13.

A number of witnesses testified that they had contacted the FBI or the

Alabama authorities with complaints about violations committed by activists

in the anti-New South Coalition bloc. See, e.g., R10-94-110; R10-140-42; R10-

204, 213-24; Rll-409; Rll-423-26.

The testimony also established that investigators had not followed up on

indications of voting violations committed by a number of white individuals or

black anti-New South Coalition partisans. See, e.g. R14-1004, 1006, 1012,

10

1020, 1023-24, 1028, 1034-37; RIO-237; Rll-376; Rll-412. The evidence

further suggested that, to the extent the FBI did investigate allegations

brought by New South Coalition members, it did so after the filing of the

selective prosecution motion in this case, see Rll-426, suggesting that the

investigation was conducted for the purpose of rebutting the motion.

Throughout the selective prosecution hearing, the government sought

to explain away the existing focus of its probe by insisting that its investigation

was "ongoing." See, e.g., id. at 362, 415; R13-808, 817; R14-975, 976, 1058.

The government’s massive investigative effort yielded an indictment in

which appellants were alleged to have acted illegally with respect to seven of

the 1,429 absentee ballots cast in the 1994 general election. At trial, Assistant

U S. Attorney Meadows acknowledged, with regard to the other absentee

ballots that appellants may have witnessed, that "I honestly can’t prove any

thing illegally about these," R15-206; "I can’t prove that they’re improper," id.

at 207. Nonetheless, over appellants’ objection, see id. at 174-75, Meadows

elicited lengthy testimony regarding the other ballots Tyree had witnessed, see

id. at 176-205; R17-594-645. As Meadows’s closing argument shows, see R20-

1199-1200, the introduction of that evidence could only be understood as an

attempt to suggest massive criminal activity on the basis of uncharged - even

constitutionally protected -- conduct.

2. Racial bias in the selection of the jury: The juiy in this case was

11

selected from a pool drawn from the entire Northern District of Alabama,

which, as we have already seen, had the foreseeable consequence of producing

an overwhelmingly white venire.

Faced with claims regarding racial discrimination in the parties’ use of

their peremptory strikes, the district court found that appellants’ decisions

were "racially neutral." 1SR-16. By contrast, it found that the United States

had used its peremptory strikes in a racially discriminatory manner. The

United States used three of its six peremptory strikes to remove African

Americans. Assistant U.S. Attorney J. Patton Meadows explained that he had

struck two female black venirepersons because they had family members who

lived in Greene County. See id. at 14-15. With regard to a third black

venireperson struck by the government, Anthony Gray, Meadows claimed that

Gray had not been paying attention during voir dire.

The district court observed that the two women’s connections with

Greene County seemed "tenuous," although it ultimately accepted the

government’s explanation. Id. at 16. But the district court rejected Meadows’s

proffered justification as to Anthony Gray, finding that the government’s

claims were "not consistent" with its observations. Id. It therefore ordered

that Anthony Gray be seated on appellants’ jury.

3. The evidence at trial. Absentee voting in Alabama is a two-step

process, involving first an application and then a ballot. An eligible voter can

12

file an application with the county Circuit Clerk, R15-117, containing his

name, various other information and an address to which he wishes to have

the ballot sent, id. at 118. (The address need not be his voting address.) The

clerk then checks the voting rolls to make sure the person requesting the

ballot is properly registered to vote and sends him an absentee ballot packet.

id. at 134. The packet contains a ballot, a plain envelope (commonly referred

to as a "secrecy" envelope) and an outer envelope (commonly called an

"affidavit" envelope). See Ala. Code § 17-10-9. The affidavit requires the

voter’s name, place of residence, voting precinct, date of birth, and reason for

voting absentee, as well as his signature or mark. The affidavit must either be

notarized or witnessed by two witnesses. See id.

The government’s case centered on seven absentee ballots, see R15-147-

48, which it contended that either one or both of the appellants were

responsible for casting without the consent of the nominal voter. The key

evidence, in addition to live testimony from some of the voters and two expert

witnesses, consisted of the absentee applications and affidavits connected with

each of the seven voters.

It was undisputed that one or both of the appellants were involved with

each ballot, as a witness or in filling out "administrative" information such as

the voter’s name, address, or polling place. (It is perfectly legal for someone

other than the voter to fill out this "administrative" information; the Circuit

13

Clerk testified that on occasion, the staff in her office would insert the

necessary information. See R15-225.) As to some, but not all, of the

applications or affidavits, appellants also provided the voter’s signature. Table

1 summarizes the evidence, taken in the light most favorable to the government.

Voter Signature on Ballot

Application

Signature on Voter

Affidavit

Angela

Hill

No testimony regarding who

signed the ballot application.

Tyree signed the voter

affidavit. R17-708.

Eddie

Gilmore

Neither Smith nor Tyree

signed the ballot application.

See R17-719/1)

Tyree signed the voter

affidavit. R17-707.

Sam

Powell

Tyree "probably" signed the

ballot application. R17-715.

Neither Smith nor Tyree

signed the voter affida

vit/2)

Shelton

Braggs

Neither Smith nor Tyree

signed the ballot application.

R17-756.

Tyree signed the voter

affidavit. R17-707.

Willie

Carter

Smith signed the ballot appli

cation. R17-709.

Not able to determine who

signed the voter affidavit.

R17-719/3)

Cassandra

Carter

Smith signed the ballot appli

cation. R17-709.

Not able to determine who

signed the voter affidavit.

R17-719/4)

Michael

Hunter

Neither Smith nor Tyree

signed the ballot application.

R17-724/5)

Neither Smith nor Tyree

signed the voter affidavit.

R17-724.

Table l 5 [footnotes on next page]

14

The pivotal issue in this case was the question of the seven voters’

consent. See R20-1285, 1290. The government called six of the alleged "victim

voters" as witnesses. The government did not call the seventh voter -- Shelton

Braggs, whose vote was the subject of Counts 12 and 13 of the indictment. 5

5 Notes to Table 1:

The government failed to obtain any handwriting exemplars from

Gilmore; appellants’ expert, on the basis of his exemplar, concluded that

Gilmore had probably written his own signature. See R19-1025.

Burnette Hutton, Sam Powell’s daughter - signed the affidavit.

R17-737.

On cross-examination, the government’s expert looked at addition

al exemplars of Carter’s signature provided by Carter and testified that the

signature looked similar to some known Carter signatures. R17-764.

The signature could have been written by the same person who

signed the Willie C. Carter affidavit, see R17-763, which appellants’ expert

testified it was "highly probable" Willie C. Carter had in fact signed, R19-1015.

The government failed to obtain exemplars from Hunter or from

his brother. See R17-760.

15

Each of the six alleged victim voters who testified provided some

evidence from which the jury might have concluded that the voter did not

consent to cast an absentee ballot in the 1994 general election. But the

government was forced to rely on several voters’ grand jury testimony because,

on the stand, the voters indicated that they had consented to the casting of

their votes. See, e.g., R16-472 (voter Michael Hunter testified at trial that his

brother had signed his ballot with his consent; the government introduced his

testimony before the grand jury to prove lack of consent); R17-567 (voter

Willie C. Carter testified at trial that he had given appellant Smith permission

to submit an absentee application; the government introduced his testimony

before the grand jury to prove lack of consent).

The government presented no evidence with regard to Shelton Braggs’s

consent. The government had no known examples of Braggs’s handwriting,

see id. at 757, and its expert witness testified that Tyree had not signed

Braggs’s absentee ballot application, id. at 756. The only evidence in the

record regarding Braggs was that he was a registered voter in Greene County

who spent most of his time out of state and that, during the summer of 1994,

#he had been Tyree’s boyfriend and had been living with her, R18-879-80.

On the counts relating to Sam Powell, appellant Tyree was prevented

from presenting evidence regarding his consent by the district court’s exclusion

of a key witness’s testimony. There was undisputed testimony by the

16

government’s own expert witness that Burnette Hutton, Powell’s daughter, had

signed Powell’s voter affidavit. R17-737. Hutton appeared as a defense

witness at the selective prosecution hearing. Before she was permitted to

testify, however, the government asked the court to advise her of her Fifth

Amendment right to remain silent and to appoint counsel for her. R11-288.

After discussion with the magistrate judge, Hutton indicated her willingness

to testify. She testified that she had assisted her father, who was illiterate and

whose business affairs she handled, with his absentee ballot in 1994 by signing

for him. Id. at 294. She also testified that she had told FBI agents who had

interviewed her that she had signed her father’s ballot with his consent. See

id. at 300. After a somewhat frustrating cross-examination, the government

abruptly demanded that Hutton provide handwriting exemplars while on the

witness stand, id. at 327. The clear import of this demand, particularly in light

of the government’s earlier representations, was to threaten Hutton with

prosecution for sticking to her story. Certainly, the magistrate judge

understood that to be the message, since he interrupted the hearing and

renewed his "suggestion]" that he appoint counsel for her. Id. at 333.

Ultimately, Hutton agreed. Magistrate Judge Putnam recessed the hearing

and appointed Rick L. Burgess, Esq., to represent her.

That afternoon, during a discussion among counsel for Hutton,

appellants, and the government, Meadows became incensed, id. at 355 ("THE

17

COURT: Calm down. All right. Go ahead, Pat."), and claimed that Hutton’s

testimony was "all a lie." Id. at 337. He insisted that Hutton had never told

him that she had signed her father’s affidavit. See, e.g., id. at 342, 343, 355

("I’m here to tell you that is a point blank lie.").

In light of the government’s threat to open a perjury investigation and

her newly appointed attorney’s sense that she had not intelligently waived her

rights, the magistrate judge announced that "I’m not going to make her get on

the stand now," id. at 345. In response, U.S. Attorney Privett responded:

Judge, we certainly understand that. And basically the last thing,

I think, that we had was the handwriting, wasn’t it Pat? [J. Patton

Meadows].

MR. MEADOWS: The handwriting. And I wanted to mark those

affidavits so that they could be identified that those are the affida

vits that we were talking about, and the application. I haven’t had

a chance to do that yet.

Id. at 346, 347 (emphasis added). The magistrate judge refused to require her

to testify as to the affidavit:

I’m not going to make her do that. It seems to me that that goes

more to helping establish the perjury charge, because ultimately

what that would be is that would be the basis for saying, this is the

affidavit you claim to have signed for your father. Here the hand

writing on this affidavit does not match your actual handwriting

exemplars, therefore it must be a peijuiy.

Id. at 349. He did, however, order Hutton to provide handwriting exemplars.

Ultimately, the government’s own expert witness concluded that "the Sam

Powell voter signature on the affidavit, compared to the known handwriting

18

of Burnette Hutton writing the name Sam Powell, again is very good

agreement." R17-737.

At trial, Sam Powell testified in a somewhat confused fashion. He was

unsure of the year in which he was bom, compare R 16-440 with R 16-442; and

his age, compare R16-437 with R16-443. He testified that he did not

remember giving Hutton permission to fill out his ballot, see R16-438-39, but

he also testified that his daughter had never done anything for him in handling

his affairs that he had not told her to do, see id. at 448.

When appellants called Hutton to testify, the government represented

that it had an "open" case file in its office regarding Hutton’s peijury. R18-

855. Since it could hardly now claim that she had lied about whether she had

signed her father’s affidavit, it now represented that it was considering a

perjury prosecution on the question whether Hutton had indeed told AUSA

Meadows this when he had interviewed her. R18-862. In light of this

apparent vendetta, Hutton, provided with a second court-appointed lawyer,

quite sensibly declined to testify. R19-978.

Since Hutton was therefore unavailable, appellants sought to introduce

her testimony from the selective prosecution hearing under Fed. R. Evid.

804(b)(1). They wished to introduce solely that part of her testimony in which

she said she had signed Powell’s affidavit with his consent. The government

objected on the grounds that it had not had a full opportunity to cross

19

examine her. R19-975. The district court agreed and excluded Hutton’s

entire testimony. R19-1056.

Standard of Review

Appellants’ claim o f selective prosecution: This Court has not expressly

identified the standard of review for claims of selective prosecution once, as

here, defendants have shown their entitlement to an evidentiary hearing.6 It

has suggested in dicta that the appropriate standard is de novo. See United

States v. Jones, 52 F.3d 924 (11th Cir.) ("[T]he record is sufficient for us to

determine that Jones’s selective prosecution defense is clearly without merit.

No additional facts need be developed, and any district court decision of the

4.

issue would be reviewed de novo by this Court anyway."), cert, denied, 516 U.S.

902 (1995). The most comparable case within this Circuit, United States v.

Gordon, 817 F.2d 1538, 1540-41 (11th Cir. 1987), cert, dismissed, 487 U.S. 1265

(1988), appears to have treated the question whether particular evidence is

6 The case law employing the more deferential abuse of discretion

standard quite clearly concerns only the question whether defendants are

entitled to an evidentiary hearing, see, e.g., United States v. Quinn, 123 F.3d

1415, 1425-26 (11th Cir. 1997), cert, denied, 118 S. Ct. 1203 (1998), and has no

bearing on whether the evidence adduced at the hearing is sufficient to

establish the defense.

20

sufficient to establish invidiousness as a legal one subject to de novo review.

Other courts of appeals reviewing claims of selective prosecution have applied

the clearly erroneous standard to questions of historical fact and

discriminatory purpose, see, e.g., United States v. Benny, 786 F.2d 1410, 1418

(9th Cir.), cert, denied, 479 U.S. 1017 (1986).

Appellant Tyree’s claim o f insufficient evidence to support a conviction on

Counts 12 and 13\ The standard of review is "de novo, viewing the evidence

in the light most favorable to the government and drawing all reasonable

inferences and credibility choices in favor of the jury’s verdict." United States

v. Lumley, 135 F.3d 758, 759 (11th Cir. 1998).

Appellants’ claims regarding their sentences: The standard of review for

the district court’s interpretation and application of the guidelines is de novo,

see United States v. Barakat, 130 F.3d 1448, 1452 (11th Cir. 1997); United States

v. Tokars, 95 F.3d 1520, 1531 (11th Cir. 1996), as is the standard of review

regarding whether Tyree’s conduct justifies an abuse-of-trust enhancement, see

United States v. Garrison, 133 F.3d 831, 837 (11th Cir. 1998). A sentencing

court’s determination regarding a defendant’s role in the offense is reviewed

for clear error. See United States v. Tapia, 59 F.3d 1137, 1143 (11th Cir.), cert,

denied, 516 U.S. 1001 (1995).

Appellants’ claims regarding the district court’s interpretation o f 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973i(c): These are questions of law and the standard of review is de novo.

21

See, e.g., United States v. Lumley, 135 F.3d at 759-60; United States v. Sirang,

70 F.3d 588, 595 (11th Cir. 1995) (applying "essentially de novo" review to

claims of multiplicity).

Appellants’ claim regarding the introduction o f evidence involving other

ballots witnessed by Tyree: A trial court’s evidentiary rulings are reviewed

under an abuse of discretion standard. See Tokars, 95 F.3d at 1530.

Appellant Tyree’s claims regarding her inability to introduce the testimony

of Burnette Hutton: The standard of review for a claim that the prosecutor or

court has substantially interfered with a defense witness’ decision to testify is

an open question. While an abuse of discretion standard is used in reviewing

evidentiary decisions challenged on compulsory process grounds, see, e.g.,

United States v. Blum, 62 F.3d 63, 67 (2d Cir. 1995), the decisions of this Court

concerning the underlying claim of "substantial government interference with

a defense witness’ free and unhampered choice to testify," see, e.g., United

States v. Schlei, 122 F.3d 944, 991-93 (11th Cir. 1997), cert, denied, 118 S. Ct.

1523; United States v. Henricksen, 564 F.2d 197, 198 (5th Cir. 1977),7 quite

clearly employed a less deferential standard. The standard of review on the

7 In Bonner v. City o f Prichard, 661 F.2d 1206, 1207 (11th Cir. 1981) (en

banc), this Court adopted as binding precedent all decisions of the Fifth

Circuit handed down prior to October 1, 1981.

22

question whether the district court ought to have admitted Hutton’s prior

testimony from the selective prosecution hearing is abuse of discretion. See

United States v. Deeb, 13 F.3d 1532, 1534 (11th Cir. 1994), cert, denied, 513

U.S. 1146 (1995).

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

This appeal is complicated only because the government’s invidious

behavior manifested itself in so many violations of appellants’ rights and

because the court below so pervasively misunderstood both the substantive law

regarding 42 U.S.C. § 1973i and the legal standard for assessing a claim of

selective prosecution.

These prosecutions were unconstitutionally initiated and improperly

maintained. Instead of applying the "ordinary equal protection standards" that

the Supreme Court has held govern claims of selective prosecution, the Magis

trate Judge invented a legal standard under which no selective prosecution

claim can ever succeed: one that ignored its own findings of fact about what

the government had already done on the hypothesis that at some time in the

future the government might cure its existing, constitutionally defective charg

ing pattern. The Magistrate Judge compounded this flagrant legal error with

a series of other erroneous legal rulings regarding appellants’ burden of proof

and the relevant comparison set for assessing a claim of political selectivity.

The government then proceeded to a trial rife with constitutional and

23

legal error. The indictment’s multiplicitous counts disregarded the allowable

unit of prosecution under 42 U.S.C. § 1973i, and denied appellants’ rights

under both the double jeopardy and due process clauses of the Fifth Amend

ment. The government’s behavior in jury selection, as the district court found,

constituted prohibited racial discrimination. The government threatened one

prospective defense witness to dissuade her from testifying and the district

court compounded the Sixth Amendment violation by refusing, in abuse of its

evidentiary discretion, to admit the witness’s prior testimony. The government

then introduced irrelevant evidence involving absentee ballots as to which it

conceded no illegality or impropriety could be shown in a grossly prejudicial

attempt to insinuate that appellants’ First Amendment-protected activity was

somehow evidence of criminality. And it proceeded on two counts against

appellant Tyree despite having literally no evidence regarding an essential

element of the offense: the nonconsent of the allegedly affected voter.

The district court’s misinterpretations of section 1973i infected both its

charging and its sentencing decisions. Its charge to the jury permitted the jury

to convict appellants without finding, beyond a reasonable doubt, that

appellants had knowingly and willfully cast other voters’ ballots without those

voters’ actual consent; under the court’s charge, the jury was permitted to

disregard evidence of consent-in-fact in favor of a theory under which, as a

matter of law, even a voter’s explicit assent was insufficient. The sentences it

24

meted out reflected an egregious misreading of the clear text of the relevant

sentencing guideline and were impermissibly enhanced in ways prohibited both

by the relevant guidelines and by prior decisions of this Court.

Such a catalog of prosecutorial misbehavior and induced legal error

would be scarcely plausible were it not for the background of this case. As

this Court knows only too well, the sorry history of this proceeding

recapitulates the pattern of prosecutorial abuse found a decade ago. Its

recurrence is both disheartening and outrageous.

ARGUMENT

I. The Indictment in this Case Should Be Dismissed Because the Govern-

ment Engaged in Racially and Politically Selective Prosecution

To support a claim of selective prosecution, a defendant must establish

two things: first, "that he has been singled out for prosecution while others

similarly situated have not generally been proceeded against for the type of

conduct with which he has been charged," United States v. Gordon, 817 F.2d

1538, 1539 (11th Cir. 1987) (what Magistrate Judge Putnam called the

selectivity prong, R2-88-21) and second, that the decision to prosecute "was

based upon an impermissible factor such as race" or political affiliation,

Gordon, 817 F.2d at 1539 (what Magistrate Judge Putnam called the

motivation" prong, R2-88-21). See United States v. Armstrong, 517 U.S. 456,

465 (1996); Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598, 608-09 (1985).

25

In this case, there was an extensive evidentiary hearing on appellants’

claim of racially and politically selective prosecution. The Magistrate Judge

found, as a matter of fact, that persons other than the defendants "have

engaged in fraudulent absentee-ballot voting activities, including forging

voters’ signatures and altering ballots." R2-88-24-25. See also id. at 13-16. In

particular, he found "evidence of potentially illegal activity by Rosie Carpenter,

who clearly is a member of and associated with Citizens for a Better Greene

County," id. at 27 n.5, a "rival political organization," id. at 27, which opposes

the "black majority faction," Gordon, 817 F.2d at 1540, to which both

appellants belong. Nonetheless, Magistrate Judge Putnam held that appellants

4 .

had failed to show either selectivity or discriminatory motivation. R2-88-24.

A. The Magistrate Judge Used the Wrong Legal Standard for Determining

Whether Similarly Situated Individuals Had Not Been Prosecuted

The linchpin of Magistrate Judge Putnam’s conclusion with regard to the

"selectivity" prong was his belief that

the defendant is required to show by clear and convincing evi

dence that a prosecutorial decision was made to prosecute him or

her and not to prosecute other persons similarly situated to the

defendant. It is not enough to show simply that the defendant has

been prosecuted and that some other person like him as not yet

been prosecuted.... [Sjome are prosecuted presently, and others

will be prosecuted in the future.... [I]t is the burden of the defen

dants to show that, in fact, no other prosecutions are planned and

that they alone have been singled out for prosecution.

R2-88-21, 22, 25 (underlining in original).

26

The standard applied by the Magistrate Judge contains two critical legal

errors. First, under the "ordinary equal protection standards" that the

Supreme Court has directed be used in selective prosecution cases, Armstrong,

517 U.S. at 465, defendants are not required to prove a discriminatory effect

by clear and convincing evidence; they need meet their burden by only a

preponderance.

The Magistrate Judge’s second error is even more serious. Essentially

he held that defendants can never satisfy the similarly situated requirement as

long as it is possible that the government may prosecute similarly situated

individuals in the future. The Magistrate Judge cited no legal authority for this

novel proposition, and indeed there is none. In Armstrong, the Supreme Court

phrased the appropriate comparison retrospectively: "the claimant must show

that similarly situated individuals of a different race were not prosecuted." 517

U.S. at 465 (emphases added). Similarly, in Gordon, this Court found that the

defendant would establish a discriminatory effect if he could show that the

government "chose to prosecute him and other black political leaders in

Alabama’s majority-black ‘Black Belt’ counties for voting fraud, while not

prosecuting county residents who were members of a rival white-dominated

political party and committing similar election offenses." 817 F.2d at 1540

(emphases added).

The standard the Magistrate Judge proposed would completely gut the

27

law of selective prosecution: until the statute of limitations expires, it is always

possible for the government to prosecute other individuals. There is simply

no way - short of an express concession by the prosecutor that he will pursue

no other cases, a concession which no prosecutor would ever provide — for a

defendant to prove that no future prosecutions will be forthcoming and to

meet the standard for selectivity imposed by the Magistrate Judge in this case.

Had he applied the standard identified by the Supreme Court in Armstrong

and this Court in Gordon, he would have concluded that appellants had met

their burden of showing that "others similarly situated generally had not been

prosecuted for conduct similar to" theirs, Wayte, 470 U.S. at 605.

B. The Magistrate Judge Made Several Legal Errors in Assessing the

Evidence of Discriminatory Purpose

Yet another series of legal errors infected the Magistrate Judge’s

conclusion that appellants had failed to establish that the government acted

with a discriminatory motive.

First, again in defiance of the Supreme Court’s directive that courts

draw on "ordinary equal protection standards" in reviewing claims of selective

prosecution, Armstrong, 517 U.S. at 465, the Magistrate Judge held that appel

lants were required to make their showing "by clear and convincing evidence,"

R2-88-22, rather than by a preponderance of the evidence. That the Supreme

Court has observed that evidence of discrimination must be "clear" in order

28

to overcome the presumption of prosecutorial good faith, Armstrong, 517 U.S.

at 464, is simply not the same thing as requiring defendants to meet a higher

burden of proof on the discrete question of discriminatory purpose.

Second, in contradiction to the clear import of this Court’s decision in

Gordon, the Magistrate Judge held that race could not be "a motivating factor"

in the decision to prosecute appellants because "[a]ll of the other [similarly

situated] people identified by the defendants are themselves African-

American, like the defendants." R2-88-26. In fact, despite the fact that

Greene County is overwhelmingly black, appellants did present testimony of

voting-rights violations committed during the 1994 election season by white

persons. See, e.g. RIO-97 (Patsy Rankins); id. at 99 (Betty Banks). But in any

event, the Magistrate Judge was simply wrong as a matter of law in concluding

that there could be no racially discriminatory purpose, under the circumstances

of this case, if some or all of the similarly situated individuals were also black.

The claim here, as in Gordon, was that the government chose to prosecute

members of the black majority faction, while not prosecuting "members of a

rival white-dominated political party." 817 F.2d at 1540. A decision to

prosecute made on the basis of the races of the people with whom a

defendant associates is a decision "based upon an unjustifiable standard such

as race, religion, or other arbitrary classification, including the exercise of

protected statutoiy and constitutional rights," such as freedom of association.

29

Wayte, 470 U.S. at 608 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted); cf

Parr v. Woodmen o f the World Life Ins. Co., 791 F.2d 888, 892 (11th Cir. 1986)

(holding that an applicant for employment has been discriminated against "on

the basis of his race" within the meaning of Title VII if he is denied a job on

the basis of the race of someone he associates with). It clearly must violate

the equal protection clause for a prosecutor to pursue cases against defendants

who are members of a virtually all-black political faction while not pursuing

cases against individuals, whatever their race, who are members of a biracial

or majority-white faction.

Third, the Magistrate Judge committed legal error with regard to appel

lants’ claim of politically selective prosecution. He correctly recognized that

a prosecutor violates the equal protection clause when he chooses his targets

based on their political affiliation, R2-88-23 n. 4; see also Wayte, 470 U.S. at

608, and he correctly found that both appellants were members of an identifi

able political faction, see R2-88-27. But he then concluded that the fact that

some similarly situated individuals were members of neither appellants’ faction

nor the opposing faction somehow rebutted appellants’ allegation that they had

been singled out. This conclusion reflected a fundamental misunderstanding

of the basis for a claim of selective political prosecution: the relevant question

is whether members of an identifiable political group have been singled out

for prosecution while non-members o f that group have not. Under the

30

Magistrate Judge’s logic, a Democratic prosecutor who prosecuted only

Republicans for speeding, while not charging similarly situated Democrats

would be able to rebut the inference of a discriminatory political motive by

pointing out that he also had not prosecuted any independents or non-voters.

That cannot be the law. So, too, the fact that the government in this case

prosecuted neither associates of Citizens for a Better Greene County nor

unaffiliated voters, while it may be evidence tending to rebut appellants’ claim

of politically selective prosecution, does not pretermit that claim altogether.

Finally, the Magistrate Judge completely ignored the larger context in

which appellants’ claim arose. As AUSA Meadows’ remarks during voir dire

show, the decision to bring this case in federal court can be explained, at least

in part, by the desire to avoid a Greene County (i.e., overwhelmingly black)

jury.

C. The Government’s Behavior at Trial Provides Additional Compelling

Evidence of its Discriminatory Intent

This Court is surely well aware that findings of Batson violations are

relatively rare. Both trial courts and appellate courts tend to accept

prosecutors’ explanations based on a venireperson’s demeanor. See generally

Kenneth J. Melilli, Batson in Practice: What We Have Learned About Batson

and Peremptory Challenges, 71 Notre Dame L. Rev. 447 (1996); Michael J.

Raphael & Edwards J. Ungvarsky, Excuses, Excuses: Neutral Explanations

31

Under Batson v. Kentucky, 27 U. Mich. J.L. Ref. 229 (1993); Joshua E. Swift,

Note, Batson’s Invidious Legacy: Discriminatory Juror Exclusion and the

"Intuitive" Peremptory Challenge, 78 Cornell L. Rev. 336 (1993).

Nonetheless, in this case, the trial court rejected the government’s expla

nation for one of its three strikes of a black venireperson as pretextual. And

it found the prosecutor’s other two strikes, which were arguably infected by

racial considerations since they involved striking jurors because of their con

nection with overwhelmingly black Greene County, to be "tenuous." The fact

that the prosecutor was discriminating on the basis of race in jury selection

provides powerful corroborative evidence of appellants’ claim that racial con-

siderations also infected his charging decision. Cf Keyes v. School District No.

I, 413 U.S. 189, 208 (1973) (holding that a finding of intentional racial dis

crimination "in a meaningful portion of a school system ... creates a presump

tion that other segregated schooling within the system is not adventitious").

So, too, here: the government’s subsequent actions in violating the equal

protection clause overcome the normal presumption of prosecutorial fairness.

II. There Was Insufficient Evidence to Convict Appellant T>ree on Counts

12 and 13

Counts 12 and 13 charged appellant Tyree with knowingly or willfully

giving false information as to Shelton Braggs’s eligibility to vote. Count 12

involved Braggs’s application for an absentee ballot. Count 13 involved

32

Braggs absentee ballot affidavit. Even taking all the evidence in the record

in the light most favorable to the government, these counts cannot stand.

As the district court recognized, Counts 12 and 13 required the

government to prove, beyond a reasonable doubt, that Braggs had neither

filed the application or affidavit himself nor had consented to their being filed

on his behalf, and that Tyree nonetheless knowingly and willfully provided

false information for the purpose of casting his ballot.

The government, however, did not call Shelton Braggs as a witness at

trial. Nor did it call any other witness on the question of his consent. Thus,

there was literally no evidence in the record regarding whether Braggs’s

application and affidavit were filed at his direction. With respect to Braggs’s

application, in fact, the undisputed testimony of the government’s own expert

witness was that Tyree wrote various "administrative" information but that she

did not sign the application. See R17-712-13, 719, 756. The government

possessed no known examples of Braggs’s handwriting. Id. at 757. All the

evidence in the record was entirely consistent with a finding that Braggs

himself had signed his application for an absentee ballot. The jury had no

basis for concluding that anyone other than Braggs signed the application, let

alone evidence from which it could conclude beyond a reasonable doubt that

Tyree or someone acting in concert with her had done so.

With regard to Braggs’ ballot affidavit, there was expert testimony that

33

Tyree signed for Braggs. Id. at 707. But again there was literally no evidence

that she signed without his consent. The only evidence in the record regarding

Braggs was that during the summer of 1994, he had been Tyree’s boyfriend

and had been living with her, R18-879-80. That evidence is equally consistent

with the hypothesis that Braggs directed Tyree to fill out his ballot, or acqui

esced in her doing so as with the hypothesis that she did so without his con

sent. Under these circumstances, Tyree’s conviction on Counts 12 and 13

should be reversed, with directions to the district court to dismiss the counts.

III. Appellants’ Sentences Violated the Sentencing Guidelines

A. The District Court Chose the Wrong Base Offense Level

Over appellants’ objections, and in reliance on the revised Presentence

Investigation Reports, R3-122 and R3-125, the district court held that the

appropriate Base Offense Level for appellants’ offenses was 12. See R22-11.

That conclusion squarely violates the express language of the relevant

Guideline which provides that appellants’ conduct constitutes a Base Offense

Level of 6.

Section 2H2.1(a) provides, in pertinent part, that the Base Offense Level

for "Obstructing an Election or Registration" is

(2) 12, if the obstruction occurred by forgery, fraud, theft, brib

ery, deceit, or other means, except as provided in (3) below,

or

34

(3) 6, if the defendant (A) solicited, demanded, accepted, or

agreed to accept anything of value to vote, refrain from

voting, vote for or against a particular candidate, or register

to vote, (B) gave false information to establish eligibility to

vote, or (C) voted more than once in a federal election.

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Guidelines Manual § 2H2.1 (1997) (emphasis

added). The district court acted as if § 2H2.1(a)(3) simply did not exist, and

completely ignored the exceptions clause of § 2H2.1 (a)(2).

The substantive offenses of which appellants were convicted were (1)

providing false information to establish eligibility to vote, 42 U.S.C. § 1973i(c)

(Counts 3-13), and (2) voting more than once in a federal election, 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973i(e) (Count 2). The conspiracy in which they were alleged to have been

engaged was a conspiracy to commit those two substantive offenses. See R20-

1330. The language of the Guidelines that provides for a base offense level

of 6 tracks exactly the statutes under which appellants were convicted. The

Sentencing Guidelines clearly provide that the particular forms of fraud or

deceit of which appellants were convicted warrant a base level of 6. Other

forms of forgery, fraud, or deceit -- such as casting fictitious votes on voting

machines and then destroying poll slips to conceal the fraud, see Anderson v.

United States, 417 U.S. 211, 214-15 (1974) or paying voters to vote for partic

ular candidates, see, e.g, United States v. Bowman, 636 F.2d 1003, 1006-07 (5th

35

Cir. 1981)8 - justify the higher Base Offense Level. Nothing in the record

would support a claim that appellants engaged in any criminal activities not

covered by § 2H2.1 (a)(3) and neither the government, the presentence

investigation report, nor the district court identified any such activity. Indeed,

the Presentence Investigation Report explains that appellants’ conduct "clearly

falljs] within § 2H2.1 (a)(2) because the obstruction to the election in those

counts involved forgery and deceit." R3-125-7. But the forgery and deceit

involved lay precisely in the fact that appellants gave false information to

establish voter eligibility. Providing false information and voting more than

once inherently involve fraud and deceit; they will also often involve forgery.

To permit district courts to use the presence of forgery, fraud, or deceit in

false statement and voting-more-than-once cases will essentially write

§ 2H2.1 (a)(3) out of the Guidelines altogether.

B. The District Court Erred in Enhancing Appellant Tyree's Sentence for

Abuse of Trust

The district court enhanced appellant Tyree’s sentence two levels for

abuse of trust because she held the position of Deputy Registrar. The

8 The voter himself, however, would be subject to Base Level 6 for "ac

cepting] or agreeing] to accept anything of value to vote." Guidelines §

2H2.1(a)(3).

36

Presentence Report claimed therefore that she "used her position of public

trust in a manner that significantly facilitated the commission of the offense

in that she fraudulently registered Sam Powell and others to vote in Greene

County, Alabama, without their knowledge or permission." R3-125-8.9

This Court has quite firmly held that an abuse of trust enhancement is

appropriate only if the defendant was both (1) "in a position of trust with

respect to the victim of the crime" and (2) "the position of trust ... contributed

in some significant way to facilitating the commission or concealment of the

offense," United States v. Garrison, 133 F.3d 831, 837 (11th Cir. 1998) (internal

quotation marks and citations omitted).

M.

In this case, appellant Tyree meets neither of the necessary criteria.

First, the mere fact that Tyree was a Deputy Registrar does not mean she was

in a position of trust. As Garrison noted,

Because there is a component of misplaced trust inherent in the

concept of fraud, a sentencing court must be careful not to be

overly broad in imposing the enhancement for abuse of a position

of trust or the sentence of virtually every defendant who occupied

any position of trust with anyone, victim or otherwise[,] would

receive a section 3B1.3 enhancement.

Garrison, 133 F.3d at 838 (internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

There was absolutely no evidence in the record to support the

Presentence Report’s assertion that Tyree improperly registered any voter

other than Powell.

37

The district court s finding that "the position of Deputy Registrar in Greene

County, Alabama is a position of public trust," R3-125-7, was mistaken. Deputy

Registrars in Greene County are not government employees, nor are they paid

for their work. Several of them were simply volunteers who were interested

in assisting in registration. R16-299. Moreover, as this Court has explained,

§ 3B1.3 contemplates that the defendant’s position be "characterized by

professional or managerial discretion (i.e., substantial discretionary judgment

that is ordinarily given considerable deference)," Garrison, 133 F.3d at 838

(quoting from the application note accompanying § 3B1.3). There was no

evidence in this record to support a finding that Deputy Registrars had any

4

discretionary authority or managerial authority whatsoever.

Even if this Court were to conclude that the position of Deputy Regis

trar is one of public trust, there is nothing in this record to support the neces

sary finding that Tyree occupied any position of trust with respect to any victim

of her conduct. Simply being a public employee or official at the time of an

offense does not make "society," see R3-125-5-6, the victim for purposes of

abuse-of-trust enhancement. See United States v. Barakat, 130 F.3d 1448,1454-

55 (11th Cir. 1997) (setting aside the enhancement in a tax evasion case in

volving kickbacks received by the head of a local public housing authority).

As to the second prong of the Garrison test, if "anyone" could commit

the offense of conviction, then enhancement is inappropriate regardless of the

38

defendant’s position vis-a-vis the victim. See Barakat, 130 F.3d at 1455. In

this case, it is plain that Tyree’s position as a Deputy Registrar made no actual

contribution to her ability to commit or conceal the offense. Even if Tyree

fraudulently registered Sam Powell — and she was neither charged with nor