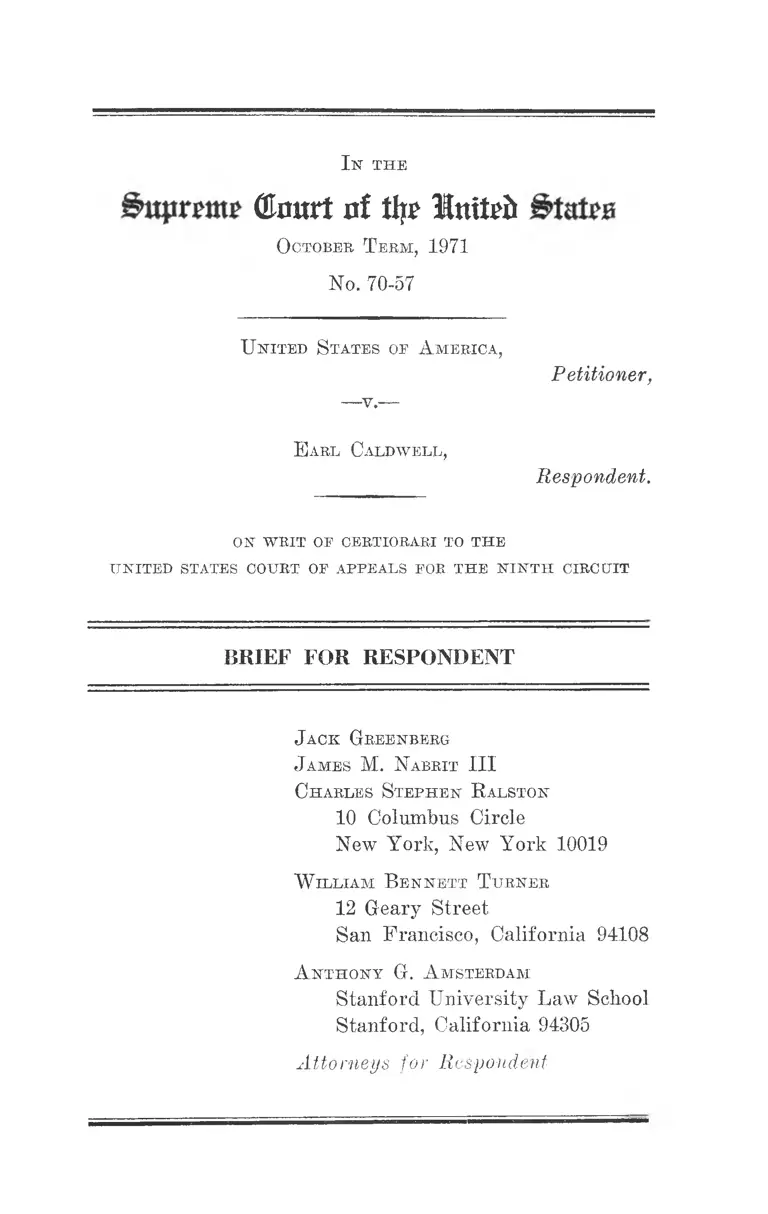

United States v. Caldwell Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Caldwell Brief for Respondent, 1971. 276f5c51-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2079f379-eb93-4147-a45b-cc61cf592352/united-states-v-caldwell-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 05, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

Olflurt at % IniteJi

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 70-57

U nited S tates o r A merica ,

— v̂.—

E arl Caldw ell,

Petitioner,

Respondent.

ON W R IT OE C ER TIO R A R I TO T H E

U N IT E D STA TES CO U RT OE A P P E A L S EO E T H E N I N T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

J ack Greenberg

J ambs M. N abrit III

C harles S t e p h e n R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

W illia m B e n n e t t T urner

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

A n th o n y G. A msterdam

Stanford University Law School

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Respondent

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................................... 2

Constitutional Statutory Provisions and Regulations

Involved ...................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ...................................................... 2

Statement of the Case .................................................... 4

A. History of proceedings below .......................... 4

B. Facts relevant to the constitutional issues

presented ........................................................... 15

1. The First Amendment Issue ....................... 15

2. The Fourth Amendment Issue..................... 41

Summary of Argument .................................................. 43

Argument .................................................................. 45

I. Introduction: The Government’s Brief ...... 45

II. Upon the Issues and Facts Presented, The

Court of Appeals Properly Refused to En

force This Grand Jury Subpoena as Oppres

sive .................................................................. 61

11

PAGE

III. The Government May Not Persist in Com

pelling Mr. Caldwell’s Attendance Before the

Grand Jury in Disregard of Its Own Guide

lines ................................................................ 66

IV. The First Amendment Forbids Compulsion

of Mr. Caldwell’s Appearance Before the

Grand Jury on This Eecord ........................ 70

V. Mr. Caldwell Has Standing to Contest the

Subpoena on the Ground That It Was Based

Upon Violations of His Fourth Amendment

Rights ............................................................... 94

C onclusion ....................................................................................... 97

A ppen dices :

Appendix A: Statutory Provisions .................. la

Appendix B : United States Department of Jus

tice, Memorandum No. 692, Guide

lines for Subpoenas to the News

Media .............................................. lb

Appendix C: Excerpts from the Government’s

Brief in the Court of Appeals

Below .............................................. Ic

Ill

PAGE

T able op A u tho eities

Cases:

Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S. 165 (1969) ,...8, 41, 42,

94, 95, 96

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1964) _________ _ 91

Application of Certain Chinese Family Benevolent and

District Associations, 19 P.R.D. 94 (N.D. Cal. 1956) 78

Application of laconi, 120 F.Supp. 589 (D.Mass.

1954) ..... .................................................................,..63, 64

Ashton V . Kentucky, 384 U.S. 195 (1966) ..................... 82

Associated Press v. KVOS, 80 P.2d 575 (9th Cir. 1935),

rev’d on other grounds, 299 U.S. 269 (1936) .......... 72

Associated Press v. United States, 326 U.S. 1 (1945) 73

Baggett V. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964) ........................ . 69

Bantam Books, Inc. v. Sullivan, 372 U.S. 58 (1963) .... 91

Barenblatt v. United States, 360 U.S. 109 (1959) ....77,80

Bates v. City of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960) ....79, 81, 91

Beckley Newspapers Corp. v. Hanks, 389 U.S. 81 (1967) 72

Blair v. United States, 250 U.S. 273 (1919) ..............63, 76

Branzhurg v. Hayes, O.T. 1970 No. 70-85 .............. 49, 50, 61

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia ex rel.

Virginia State Bar, 377 U.S. 1 (1964) ..................... 72

Brown v. Walker, 161 U.S. 591 (1896) ..... 76

Bruner v. United States, 343 U.S. 112 (1952) .............. 96

Carter v. United States, 417 F.2d 384 (9th Cir. 1969) 41

Continental Oil Co. v. United States, 330 F.2d 347 (9th

Cir. 1964) ................................ ........................ .......... 78

Costello V. United States, 350 U.S. 359 (1956) .............. 64

IV

PA G E

Cramp v. Board of Public Instruction, 368 U.S. 278

(1961)... .................................. ....................................... 82

Dandridge v. Williams, 397 U.S. 471 (1970) ..............59, 94

DeGregory v. Attorney General of New Hampshire,

383 U.S. 825 (1966) ................................... 77, 80, 81, 83, 86

DeJonge v. Oregon, 299 U.S. 358 (1937) .....................72, 73

Dennis v. United States, 384 U.S. 855 (1966) ............. 77

Dombrowski v. Plister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965) ................ . 82

Elfbrandt v. Bussell, 384 U.S. 11 (1966) ..................... 84

Ex parte Collett, 337 U.S. 55 (1949) ..................... ....... 96

Garland v. Torre, 259 F.2d 545 (2d Cir. 1958) ....78, 79, 85, 86

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U.S. 157 (1961) ..................... 82

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U.S. 780 (1966), aff’g 342 F.2d

336 (5th Cir. 1965), rehearing denied, 343 E.2d 909

(5th Cir. 1965) ........................................... ............ . 96

Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee,

372 U.S. 539 (1963) ............. 72,78,80,81,82,83,84,86

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965) ....... ...... 73

Grosjean v. American Press Co., 297 U.S. 233 (1936) ....71,

72, 73

Hair v. United States, 289 F.2d 894 (D.C.Cir. 1961) .... 95

Hale V. Henkel, 201 U.S. 43 (1906) ............................64, 78

Hoadley v. San Francisco, 94 U.S. 4 (1876) ................. 96

In re Dionisio, 442 F.2d 276 (7th Cir. 1971) .................. 78

In re Grand Jury Subpoena Duces Tecum, 203 F.Supp.

575 (S.D.N.Y. 1961) ...... .................... ....................... 83

In re National Window Glass Workers, 287 Fed. 219

(N.D. Ohio 1922) ...................................... ...............35,63

V

PAGE

Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee v. McGrath, 341

U.S. 123 (1951) ......................................................... 91

Jordan v. Hutcheson, 323 F.2d 597 (4th Cir. 1963) ...... 83

Katz V. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967) ................. 95

Lament v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301 (1965) ....71, 73

Liveright v. Joint Committee, 279 P.Supp. 205 (M.D.

Tenn. 1968) ............... ......................................... 78,82,83

Louisiana ex rel. Gremillion v. N.A.A.C.P., 366 U.S. 293

(1961) .................................................................. 81,84,91

McGrain v. Daugherty, 273 U.S. 135 (1927) ................. 77

Martin v. City of Struthers, 319 U.S. 141 (1943) ...... 73

Matter of Pappas, O.T. 1971, Ko. 70-94 ........... ......49, 50, 61

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105 (1943) .......... 72

N.A.A.C.P. V . Alabama ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S. 288

(1964) ......................................................................... 85

N.A.A.C.P. V . Alabama ex rel. Patterson, 357 U.S. 449

(1958) ....................................................... 55,72,79,82,91

N.A.A.C.P. V . Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ....72,77,81,82

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931) ........................ 72

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) ....71,

73, 75

Noto V . United States, 367 U.S. 290 (1961) ... ................ 39

People V. Dohrn, Circuit Court of Cook County, Crim

inal Division, Indictment No. 69-3808 (May 20, 1970) 87

Providence Journal Co. v. McCoy, 94 F.Supp. 186

(D.R.I. 1950), aff’d on other grounds, 190 F.2d 760

(1st Cir. 1951) ............ 72

VI

PAGE

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. F.C.C., 395 U.S. 367

(1969) ................... ....... .............................................. 74

School District of Abington Township v. Schempp,

374 U.S. 203 (1963) ................................................. 94

Scull V. Virginia ex rel. Committee on Law Reform and

Racial Activities, 359 U.S. 344 (1959) ..................... 83

Service v. Dulles, 354 U.S. 363 (1957) .................... . 68

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) -.72,78,84,86,91

Silverman v. United States, 365 U.S. 505 (1961) .......... 95

Silverthorne Lumber Co. v. United States, 251 U.S. 385

(1920) .................................................... .............. . 95

Smith V. California, 361 U.S. 147 (1959) ..............73, 75,82

Stanley v. Georgia, 394 U.S. 557 (1969) ............ ......... 73

State V. Buchanan, 436 P.2d 729 (Ore. 1968) .............. 79

Stromberg v. California, 283 U.S. 359 (1931) .......... . 73

Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234 (1957) ....77, 80, 83

Talley v. California, 362 U.S. 60 (1960) ................. 72, 80, 91

Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949) ................. 73

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1940) .................. 73

Thorpe v. Housing Authority of the City of Durham,

393 U.S. 268 (1969) ...................................................... 68

Time, Inc. v. Hill, 385 U.S. 374 (1967) .....................73,75

United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Ass’n, 389

U.S. 217 (1967) .... ............................ ............ ..... .....72, 86

United States v. Bryan, 339 U.S. 323 (1950) ..........63, 76

United States v. Dardi, 330 F.2d 316 (2d Cir. 1964) .... 35

United States v. Judson, 322 F.2d 460 (9th Cir. 1963) .... 78

United States v. Levinson, 405 F.2d 971 (6th Cir.

1968) ........... ............................................................... 95

United States v. Rumely, 345 U.S. 41 (1953) _____77,80

V ll

PAGE

United States v. Wolfson, 405 F.2d 779 (2d Cir.

1968) ................................................ 95

United States ex rel. Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347

U.S. 260 (1954) ......................................................... 68

Uphans v. Wyman, 360 U.S. 72 (1959) ........................ 80

Vitarelli v. Seaton, 359 U.S. 535 (1959) ................... . 68

Watkins v. United States, 354 U.S. 178 (1957) .-.77,80,82

Watts V . United States, 394 U.S. 705 (1969) .............. 35

Wong Sun v. United States, 371 U.S. 471 (1963) 95

Wood V . Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962) ....................... 77

Yates V . United States, 354 U.S. 298 (1957) ................. 39

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions:

United States Constitution, First Amendment ...... passim

United States Constitution, Fourtli Amendment ..41, 42, 44,

94, 95, 96

18 U.S.C. § 231 .................................................. 2, 32, 33, 39

18 U.S.C. § 232 ............................................................. 2

18 U.S.C. § 871 ................................................... 2, 32, 33, 39

18 U.S.C. § 1341 ................................................. 2, 32, 33, 39

18 U.S.C. § 1751 ........................................ 2, 32,43, 39

18 U.S.C. § 2101 ................................................. 2, 32, 33, 39

18 U.S.C. § 2385 ............................................................. 39

18 U.S.C. § 3504 ............... .............................................2, 96

Fed. Eule Crim. Pro. 17 .............................................. 63

V l l l

PAGE

79

Other Authorities:

Annot. 7 A.L.R. 3d 591 (1966) ................................

Beaver, The Newsman’s Code, The Claim of Privilege

and Everyman’s Right to Evidence, 47 Obe . L. R ev.

243 (1968) ................................................................ 70

The Black Panther, November 22, 1969 ........ 33, 34, 36, 40

The Black Panther, December 27, 1969 ........ .33,34,36,40

The Black Panther, January 3, 1970 ..............33, 34, 36, 40

Comment, Constitutional Protection for the Newsman’s

Worh Product, 6 H abv. C ivil R ig h ts-C ivil L iberties

L. R ev. 119 (1970) .....................................................

Comment, The Newsman’s Privilege: Government In

vestigations, Criminal Prosecutions and Private Liti

gation, 58 Calie . L. R ev. 1198 (1970) .....................

Comment, The Newsman’s Privilege: Protection of

Confidential Associations and Private Communica

tions, 4 J. Law Reform 85 (1970) ............................

Department of Justice Memorandum No. 692, “Guide

lines for Subpoenas to the News Media,” Septem

ber 2, 1970 ............................................ 2,12, 43, 48, 58, 59,

60, 66, 67, 68, 69

Goldstein (Abraham S.), Newsmen and Their Confi

dential Sources, The New Republic, March 21, 1970 70

Guest & Stanzler, The Constitutional Argument for

Newsmen Concealing Their Sources, 64 Nw. IT. L.

R ev. 18 (1969) ............................................................ 70

70

70

70

IX

PAGE

Newsweek, February 23, 1970 ....................................... 30

The New York Times, Sunday, June 15, 1969 ............. 36

The New York Times, Sunday, July 20, 1969 ............. 36

The New York Times, Tuesday, July 22, 1969 ..... ...... 36

The New York Times, Sunday, July 27, 1969 .............. 36

The New York Times, Sunday, December 14,1969 ..35, 36, 38

The New York Times, Sunday, February 1, 1970 ...... 27

The New York Times, Tuesday, February 3, 1970 ..... 27

The New York Times, Wednesday, February 4, 1970 .... 27

The New York Times, Thursday, February 5, 1970 27

The New York Times, Friday, February 6, 1970 27

Note, Reporters and Their Sources: The Constitu

tional Right to a Confidential Relationship, 80 Y ale

L. J. 317 (1970) ........................................................... 70

The Quill, June, 1970 ......................... ....................... . 27

Recent Case, 82 H arv. L. R ev. 1384 (1969)..................... 79

Time Magazine, April 6, 1970 ............... ....................... 30

I n t h e

Olflitrt flf

October T e em , 1971

No. 70-57

U nited S tates oe A merica,

Petitioner,

— v̂.—

E arl Caldw ell,

Respondent.

ON W R IT O P CERTIO RA RI TO T H E

U N IT E D STATES COU RT O P A P P E A L S PO R T H E N I N T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

Opinions Below

The opinions of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Ninth Circuit reversing respondent’s commitment for

contempt of court are reported suh nom. Caldwell v. United

States, 434 F.2d 1081 (9th Cir. 1970), and appear in the

Appendix at A. 114-130. The District Court wrote no

opinion when it held respondent in contempt for his refusal

to appear before a federal grand jury; its contempt judg

ment and commitment appear at A. 111-113. The District

Court did write an opinion at an earlier stage of the pro

ceedings, denying respondent’s motion to quash the grand

jury subpoena but granting him a protective order against

questioning that would violate confidential communications.

This opinion and order of the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California are reported suh

nom. Application of Caldwell, 311 F. Supp. 358 (N.D. Cal.

1970), and are set forth at A. 91-97.

Jurisdiction

This Court’s jurisdiction rests upon 28 U.S.C. § 1254 (1).

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

November 16, 1970. A petition for certiorari was filed on

December 16, 1970, and granted on May 3, 1971.

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions and Regulations Involved

This case involves the First Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States, which provides in relevant part:

“Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the free

dom of speech, or of the press . . . .”

The case also involves 18 U.S.C. §§231-232, 871, 1341,

1751, 2101-2102, 3504, which are set forth in Appendix A

to this brief [hereafter cited as App. A. pp. la -lla m/m].

It involves Department of Justice Memorandum No. 692,

“Guidelines for Subpoenas to the News Media,” promul

gated on September 2, 1970, which is set forth in Appendix

B to this brief [hereafter cited as App. B, pp. lb-3b infra].

Questions Presented

Respondent, a New York Times reporter, was subpoenaed

to testify before a federal grand jury investigating the

Black Panthers. The District Court denied his motion to

quash the subpoena, but granted him a protective order

forbidding interrogation by the grand jury that would in

vade confidences made to him by Black Panther news

sources. He was subsequently held in contempt of court for

refusing to appear before the grand jury. In this context,

the questions presented are:

I. Did the Court of Appeals err in holding that respon

dent was not required to appear before the grand jury,

where (1) the Government did not challenge the District

Court’s protective order, and (2) the record shows that

respondent has no information to give the grand jury other

than information which is covered by the protective order

or available to the grand jury in the pages of the New York

Times %

II. Did the Court of Appeals err in holding that the

First Amendment forbade the compulsion of respondent’s

appearance before a federal grand jury on this record,

which shows (1) that his appearance in secret grand jury

proceedings will destroy his unique confidential relation

ships with Black Panther news sources; (2) that the Gov

ernment failed to point to any information concerning the

Panthers that respondent might possess, which is material

to any legitimate inquiry by the grand jury; and (3) that

the Government refused even to identify the information

sought from respondent or the general subject of the

grand jury’s investigation in any fashion which would per

mit the courts below to determine the relevance of, or the

grand jury’s need for, respondent’s testimony?

III. May the Government properly persist in compelling

respondent’s appearance before a federal grand jury in

disregard of its Guidelines for Sulpoenas to the News Media

which were promulgated following the issuance of the sub

poena to respondent, but prior to the Court of Appeals

decision in his favor?

IV. Is respondent’s contempt commitment for refusal

to obey a grand jury subpoena infirm upon the alternative

ground that the District Court erred in denying his “stand

ing” to contend that the subpoena was the product of illegal

electronic surveillance by the Government upon his private

interviews with Black Panther sources?

Statement o f the Case

A. H istory o f proceedings below d

Bespondent Earl Caldwell is a black reporter for the

New York Times, specializing in the coverage of dissident

and militant groups. (A. 17-18, 114.) He was assigned to

the San Francisco office of the Times because the Times’

white reporters had been unable to maintain rapport with

members of the Black Panther Party in the Bay Area

(A. 17, 34), and “[a]s a result . . . , it became virtually im

possible for [them] . . . to gather the kind of information

necessary to report adequately on the activities, attitudes

and directions of the Black Panther Party.” (A 34)

Mr. Caldwell had developed “relationships and trusts

in several years of covering the activities of [militant]

groups, and . . . was the only newspaperman within The

New York Times organization to have developed this rela-

' Throughout this brief, citations in the form '■‘A .

0 the printed Appendix. Occasional references are also made to

the Clerk’s Record m the District Court (which is in two sepl

rately paginated volumes) and to the reporter’s transcrints of

nearings m the District Court on April 3, 1970 and June 4 .1 1970

(wluch are also in two separately paginated volumes). The’form

1 the fo?m“ ‘Il\''°^™®>^ the Clerk’s Record (paginatediob) tJie torm 11 R. ----- refers to volume 2 of the Clerk’s

Record (paginated 1-289) ; the form “I Tr. ----- ” refers to the

transcript of ̂ the hearing of April 3 (paginated 1-78) ; the form

tionsMp.” (A. 17.) Even with this unique background, it

required several months of associations with Panther Party

members before Mr. Caldwell gained their complete confi

dence. (A. 17-18.) “ [A]s they realized [he] . . . could be

trusted and that [his] . . . sole purpose was to collect . . .

information and present it objectively in the newspaper and

that [he] . . . had no other motive, [he] . . . found that not

only were the party leaders available for in-depth inter

views but also the rank and file members were cooperative

in aiding [him] . . . in the newspaper stories that [he] . . .

wanted to do.” (A. 17; see A. 122 n. 8.) Through these care

fully nurtured relationships of trust, Mr. Caldwell obtained

unusual insights concerning the Panthers’ political views

and activities which enabled him to write a number of

extraordinarily illuminating stories for the Times and there

by to contribute markedly to national public understanding

of the Panthers.^

On February 2, 1970,® Mr. Caldwell was served with a

subpoena ordering him to appear and testify before the

federal grand jury in San Francisco, and to bring with him :

“Notes and tape recordings of interviews covering the

period from January 1, 1969, to date, reflecting state

ments made for publication by officers and spokesmen

̂ (A. 117, 122 n. 8.) The record contains copies of sixteen

articles concerning the Black Panthers published by Mr. Caldwell

under his byline in the New York Times during 1969. (II R. 237-

256.) We hope that the Court will read particularly those of

June 14 (A. 83-86), July 27 (A. 87-89), and December 14 (A.

11-16), which exemplify the remarkable contribution that Mr.

Caldwell has been able to make to public understanding of the Pan

thers by virtue of the confidential relationships that are threatened

with destruction if he is compelled to appear before the grand jury.

® (A. 19.) Between December 23, 1969, and January 12, 1970,

P.B.I. agents had six times attempted to interview Mr. Caldwell,

but he had consistently declined to make himself available to talk

to them or to respond to their inquiries after him. (A. 79.)

6

for the Black Panther Party concerning the aims and

purposes of said organization and the activities of said

organization, its officers, staff, personnel, and members,

including specifically but not limited to interviews

given by David Hilliard and Raymond ‘Masai’ Hewitt.”

(A. 20.)

On March 16, he was served with a second subpoena,^ issu

ing from the same grand jury. Unlike the February 2

subpoena, the one served on March 16 was a subpoena ad

'* The record clarifies the background of the second subpoena,

as follows:

The first, February 2 subpoena was originally returnable Feb

ruary 4. (A. 20.) Subsequently, the grand jury was adjourned

beyond February 4, and Mr. Caldwell was directed instead to

appear pursuant to that subpoena on February 11. Still later, by

agreement of counsel, the return date was postponed to Feb

ruary 18. (A. 35.)

On February 9, counsel for Mr. Caldwell phoned Government

counsel and informed him that the following day, February 10,

Mr. Caldwell and The New York Times Company would move to

quash the subpoena. Government counsel agreed to a further,

indefinite continuation of its return date in order to permit the

Government to study the motions papers before they were filed

(A. 35.)

On February 10, the motions papers were mailed to Govern

ment counsel. During the following days, counsel for Mr. Caldwell

and for The New York Times Company had several inconclusive

phone conversations with Government counsel. Finally, on Friday,

March 13, Government counsel informed counsel for Mr. Caldwell

that the Government had decided upon its position and a course

of action. The February 2 subpoena would be further continued,

while the Government would cause Mr. Caldwell to be served with

a second grand jury subpoena—this one having no duces tecum

directive—returnable March 25. (A. 35-36.)

Counsel for Mr. Caldwell accordingly made him available for

service of the second subpoena as soon as the Government could

issue it: that is, on Monday, March 16. (A. 36.)

(See also the Chronology, attached as Appendix A to the docu

ment styled Reply to Government’s Opposition, I R. 32-34, for a

detailed recitation of these events.)

testificandum in the usual undelimited form,® with no duces

tecum clause. (A. 21.)

On March 17, 1970, Mr. Caldwell and The Neiv York

Times Company moved the United States District Court

for the Northern District of California to quash both sub

poenas, on the grounds that:

“1. Compelling Mr. Caldwell’s appearance before

the grand jury will cause grave, widespread and ir

reparable injury to freedoms of the press, of speech

and of association; and this Court should not permit a

use of its process that so jeopardizes vital constitu

tional interests in the absence of an overriding gov

ernmental interest—not shown here—in securing Mr.

Caldwell’s testimony before the grand jury;

® The subpoena requires Mr. Caldwell to appear and testify,

but does not identify the sub.iect matter of his expected testimony.

In an affidavit, counsel for Mr. Caldwell recited the failure of his

efforts to elicit from Government counsel the scope of the planned

interrogation of Mr. Caldwell under the similarly undelimited ad

testificandum clause of the earlier, February 2 subpoena:

“On Wednesday. February 4, 1.970, . . . T met with [coun

sel for The New York Times Company and with Government

counsel including Victor C. Woerheide, Esq.] . . . to inquire

of government counsel concerning the subject and scope of

the grand jury investigation pursuant to which the [Feb

ruary 2] subpoena had issued, and concerning the sorts of

information that the grand jury wanted from Mr. Caldwell.

“Mr. Woerheide informed me that a Federal grand jury

has ‘broad investigative powers,’ and that he was unable to

‘limit the inquiry of the grand jury in advance.’ I indicated

that, nevertheless, it was important to me to know what was

the subject of the jury’s inquiry, in order to determine

whether information sought from Mr. Caldwell was in any

way relevant to it. Mr. Woerheide replied that the subject

of a grand jury’s investigation was ‘no concern of a witness’ ;

and that he could not define it further than to say that if I

‘read the newspaper accounts of the Black Panthers, I should

know what the grand jury was concerned with.’ ” (A. 9.1

(See also A. 118.)

8

“2. The subpoenas, in their undelimited breadth,

intrude upon confidential associations necessary for

the effective exercise of First Amendment rights and

therefore protected by that Amendment against gov

ernmental abridgement; and

“3. The subpoenas are very probably based upon

information obtained by the Government through

methods of electronic surveillance that violated movant

Caldwell’s Fourth Amendment rights.” ® (A. 4.)

The motion was heard upon affidavits and documentary

exhibits by the Honorable Alfonso J. Zirpoli on April 3,

1970.'' At the hearing, the Government withdrew the Feb

ruary 2 subpoena (A. 91 n. I Tr. 5-8), thus removing it

from contention between the parties and rendering it rele

vant only (as Judge Zirpoli put it) “insofar as it may shed

light on the testimony that the Government hoped to elicit”

from Mr. Caldwell (I. Tr. 7-8; see A. 91 n. *). Following

the hearing. Judge Zirpoli denied the motion to quash the

subpoena of March 16, but did hold that Mr. Caldwell was

entitled to a protective order delimiting the scope of his

interrogation by the grand jury because:

“When the exercise of the grand jury power of testi

monial compulsion so necessary to the effective func

tioning of the court may impinge upon or repress First

Amendment rights of freedom of speech, press and

association, which centuries of experience have found

* In connection with this third point, the motion papers re

quested expressly that the District Court “conduct the sort of

inquiry into the fact, circumstances, and products of electronic

surveillance envisaged by Alderman v. United States, 394 U.S.

165 (1969).” (II R. 31-32.)

The portions of this evidentiary record relevant to the issues

now before this Court are described in detail in the following

subsection, pp. 15-42 infra.

9

to be indispensable to the survival of a free society,

such power shall not be exercised in a manner likely

to do so until there has been a clear showing of a com

pelling and overriding national interest that cannot be

served by alternative means.

“Accordingly, it is the order of the Court that Earl

Caldwell shall respond to the subpoena and appear be

fore the grand jury when directed to do so, but that he

need not reveal confidential associations that impinge

upon the etfective exercise of his First Amendment

right to gather news for dissemination to the public

through the press or other recognized media until such

time as a compelling and overriding national interest

which cannot be alternatively served has been estab

lished to the satisfaction of the Court.

“The contention of movants that the subpoenas ‘are

very probably based upon information obtained by the

Government through electronic surveillance’ is, upon

the facts before the Court, one that movants do not at

this posture of the grand jury investigation have stand

ing to raise and to the degree that movants seek to

quash the subpoena on this ground, the same is denied.”

(A. 93.)

This ruling was embodied in a memorandum opinion filed

April 6 (A. 91-93) and an order filed April 8 (A. 94-97).*

* The order makes the several factual findings, based upon the

record, that are set out at pp. 17-41 infra of this brief. By reason

of those findings, it orders:

“ (1) That if and when Earl Caldwell is directed to appear

before the grand jury pursuant to the subpoena of March 16,

1970, he shall not be required to reveal confidential associa

tions, sources or information received, developed or main

tained by him as a professional journalist in the course of

his efforts to gather news for dissemination to the public

through the press or other news media;

“ (2) That specifically without limiting paragraph (1), Mr.

Caldwell shall not be required to answer questions concerning

10

Apparently believing tbat both parts of the ruling—requir

ing Mr. Caldwell to appear before the grand jury, and giv

ing him a protective order——were appealable and raised

substantial constitutional questions,^ Judge Zirpoli stayed

the effective date of his decision pending appeal. (A. 96-97.)

On April 17, Mr. Caldwell filed a notice of appeal to the

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. On April 30, the

Government moved to dismiss that appeal upon the ground

that Judge Zirpoli’s order was interlocutory and unappeal

able, and that the appeal was frivolous and would cause an

undue interruption of the grand jury inquiry. On May 12,

statements made to him or information given to him by mem

bers of the Black Panther Party unless such statements or

information were given to him for publication or public dis

closure” (A. 96),

provided, however, that:

“the Court will_ entertain a motion for modification of this

order at any time upon a showing by the Government of a

compelling and overriding national interest in requiring Mr.

Caldwell’s testimony which cannot be served by any alter

native means . . (A. 96).

Otherwise, the motion to quash the subpoena of March 16 is de

nied. (A. 96.)

"See I Tr. 5:

“ [Th e Co urt :] . . . The ease is one of first impression and

the interests at stake are of significant magnitude, for their

resolution may well be determinative of the scope of the

journalist’s privilege as it relates to highly sensitive areas of

freedom of speech, press and association not heretofore fully

explored and decided by the Supreme Court of the United

States. Whatever affects the rights of the parties to this litiga

tion affects all.

“Hence, the Court assumes that any Order it enters in this

ease will be appealed, and that such Order should, therefore,

all probability, be stayed to await an authoritative deter-

mmation by the Court of Appeals of [sic: “or”] the Supreme

Court of the United States.”

11

the Court of Appeals dismissed the appeal without opinion.

{Application of Caldivell, 9th Cir., No. 25802, unreported

order of May 12, 1970.)

At the end of the first week in May, the term of the grand

jury that had issued the March 16 subpoena expired, and a

new g-rand jury was sworn. Accordingly, the Government

caused the new grand jury to issue a new subpoena ad

testificandum for Mr. Caldwell. (See I R. 33.) At the in

stance of counsel for Mr. Caldwell, on May 19 the District

Court conferred with the attorneys for all parties, to dis

cuss procedures for making the April 8 order applicable to

the new subpoena and for preserving Mr. Caldwell’s right

to appellate review of his constitutional contentions follow

ing the entry of an indisputably final order—i.e., one ad

judging him in contempt. Following that conference, coun

sel for Mr. Caldwell accepted service of the new subpoena

on May 22. (See I B. 26, 33-34.) On May 26, Mr. Caldwell

and The New- York Times Company moved to quash the

May 22 subpoena upon the same grounds earlier urged

against the March 16 subpoena (A. 98), and also moved

that the record of all prior proceedings be made a part of

the record for purposes of the motion to quash (I B. 3).

On June 4, Judge Zirpoli granted the motion to incorpo

rate the record of prior proceedings (A. 102-103), denied

the motion to quash the May 22 subpoena (A. 105), and

issued a protective order governing the May 22 subpoena

that was substantially identical to his order of April 8 (ex

cept that it expressly ordered Mr. Caldwell to appear before

the grand jury, and it omitted any provision for a stay pend

ing appeal) (A. 104-105).

The same day, Mr. Caldwmll declined to appear before

the grand jury. His counsel so represented to the District

Court; and the District Court ordered Mr. Caldwell to show

cause the following morning why he should not be held in

12

contempt. (II Tr. 5-6, 9-15; A. 106-107.) On June 5, Mr.

Caldwell appeared in the District Court, repeated Ms re

fusal to appear before the grand jury (A. 110), repeated

his constitutional objections to his compelled appearance

before the grand jury (A. 10'8-109), and—following the

court’s overruling of those objections {ihid.)—was held in

contempt (A. 111-113). He immediately filed a notice of

appeal (I R. 47), and the District Court stayed its contempt

order pending appeal (I R. 49).

On September 2, 1970, the Department of Justice issued

its Memorandum No. 692, “Guidelines for Subpoenas to the

News Media” (App. B, pp. lb-3b infra). Government coun

sel called these guidelines to the attention of the Court of

Appeals during oral argument of the appeal on September

9, 1970, and thereafter filed a copy with the Court of Ap

peals.̂ ® The Government did not, however, attempt to ex

plain the applicability of the guidelines to the Caldwell

case; it mentioned them, apparently, merely as a means of

persuading the Court of Appeals that the constitutional

protection sought by Mr. Caldwell was unnecessary. The

Government’s basic position in the Court of Appeals was

that, under no circumstances, did the First Amendment

protect a newspaper reporter from the obligation to appear

and testify when subpoenaed by a federal grand jury. The

grand jury

“ . . . is . . . not required to have a factual basis for com

mencing an investigation and can pursue rumors which

further investigation may prove groundless. . . . It

therefore, is not required and has not been required to

The guidelines had first been announced in a speech by the

Attorney General of the United States before the House of Dele

gates of the American Bar Association in St. Louis on August 10,

1970; and it was in the form of the press release of this speech

that they were furnished by the Government to the Court of Ap

peals.

13

make any preliminary showing before calling any per

son as a witness and accordingly need not show any

reason for any testimony or evidence. Only the grand

jury can properly decide what may be useful to its

investigation.”

Accordingly, even where First Amendment interests were

jeopardized by the compulsion of testimony under a grand

jury subpoena, the federal courts were not entitled to in

quire into the grand jury’s need for the testimony, nor to

weigh that need against the harm to First Amendment free

doms involved in its compulsion.^ ̂ This was particularly

true in Mr. Caldwell’s case because “the district court in a

protective order has already given [Mr. Caldwmll] . . . as

surances that he does not have to disclose either confidential

information or confidential sources of information.”

Thus, while noting its disagreement with Judge Zirpoli’s

protective order,“ the Government declined to challenge

the validity of that order upon this appeal, but rather urged

that because of the protection afforded by the order, Mr.

Caldwell needed no other judicial relief against his com

pelled appearance before the grand jury.̂ ®

The Court of Appeals disagreed. It concluded, with the

District Court, that “First Amendment freedoms are here

in jeopardy” (A. 118), and that their preservation required

the District Court’s protection in the form of the order it

Brief for the United States in the Court of Appeals, pp. 11-12.

The relevant portions of that brief are reproduced in Appendix G

to this brief [hereafter cited as App. C, pp. le-12c infra], wherein

the passage just quoted appears at App. C, p. 5c infra.

1̂ Id. at 13-19; App. C, pp. 6c-12c infra.

1® Id. at 14; App. C, p. 7c infra.

11 Id. at 7-8; App. C, pp. lc-2e infra.

1® See also id. at 15-16; App. C, pp. 8c-10c infra.

14

had made, prohibiting grand jury interrogation of Mr.

Caldwell that wonld invade his confidences as a newsman,

in the absence of a showing by the Government of a “com

pelling or overriding* national interest” in pursuing such

interrogation (A. 121).̂ ® But it further found that “the

privilege not to answer certain questions does not, by itself,

adequately protect the First Amendment freedoms at stake

in this area” (A. 124), because “['t]he secrecy that surrounds

Grand Jury testimony necessarily introduces uncertainty

in the minds of those who fear a betrayal of their confi

dences” (A. 123).

“The question, then, is whether the injury to First

Amendment liberties which mere attendance threatens

can be justified by the demonstrated need of the Gov

ernment for appellant’s testimony as to those subjects

not already protected by the privilege.

“Appellant asserted in affidavit that there is nothing

to which he could testify (beyond that which he has al

ready made public and for which, therefore, his appear

ance is unnecessary) that is not protected by the

District Court’s order. If this is true—and the Govern

ment apparently has not believed it necessary to dispute

it—appellant’s response to the subpoena would be a

barren performance—one of no benefit to the Grand

Jury. To destroy appellant’s capacity as news gatherer

for such a return hardly makes sense. Since the cost

to the public of excusing his attendance is so slight, it

may be said that there is here no public interest of real

* Asterisks will be used in this brief to indicate words that are

incorrectly printed in the Appendix. The brief will reproduce

such words as they appear in the original document.

The foundation for these conclusions, and for the conclusions

of the Court of Appeals next described in the text, is set forth in

detail in the following subsection, pp. 15-41 infra.

15

substance in competition with the First Amendment

freedoms that are jeopardized.

“If any competing public interest is ever to arise in

a case such as this (where First Amendment liberties

are threatened by mere appearance at a Grand Jury

investigation) it will be on an occasion in which the

witness, armed with his privilege, can stUl serve a use

ful purpose before the Grand Jury. Considering the

scope of the privilege embodied in the protective order,

these occasions would seem to be unusual. It is not

asking too much of the Government to show that such

an occasion is presented here.

“In light of these considerations we hold that where

it has been shown that the public’s First Amendment

right to be informed would be jeopardized by requiring

a journalist to submit to secret Grand Jury interroga

tion, the Government must respond by demonstrating

a compelling need for the witness’ presence before judi

cial process properly can issue to require attendance.”

(A. 125).

Finding no such demonstration on this record, the Court

of Appeals held that “the judgment of contempt and the

order directing ['Mr. Caldwell’s] attendance before the

Grand Jury [must] be vacated.” (A. 127.) It accordingly

found no need to reach the additional question whether the

District Court had erred in enforcing a grand jury sub

poena, in the circumstances of this case, while refusing to

inquire whether the subpoena was based upon unconstitu

tional electronic surveillance of Mr. Caldwell’s interviews

with Black Panther news sources. (A. 126-127.)

B. Facts relevant to the constitutional issues presented.

1. T h e F irst A m e n d m e n t Issue

To an extent never previously shown, this record docu

ments the devastating effect that the compulsion of news-

16

men’s testimony lias upon freedom of the press.” The Court

of Appeals found that: “The fact that the subpoenas would

have a ‘chilling etfeet’ on First Amendment freedoms was

impressively asserted in affidavits of newsmen of recog’-

nized stature,* to a considerable extent based upon recited

experience.” (A. 116-117.) Those affidavits—by Walter

Cronkite, J. Anthony Lukas, Eric Sevareid, Mike Wallace,

among others—made the basic points: that confidential

communications to newsmen are indispensable to their

gathering, analysis and dissemination of the news; that

when newsmen are subpoenaed to appear and testify con-

” For reasons made plain by the course of proceedings described

in the preceding subsection, this record was developed in connec

tion with the subpoena of March 16. However, it applies with

equal force to the subsequent subpoena of May 22 that underlies

the contempt adjudication now under review. This is so because;

(1) Mr. Caldwell’s motion to quash the May 22 subpoena alleged

that that subpoena was issued on the same basis and with the same

purpose as the subpoena of March 16. (A. 98.) (2) The Govern

ment’s opposition to the motion admitted th a t; “The matter under

investigation now is the same matter that was under investigation

as of April 8, 1970. The testimony to be elicited from him [Mr.

Caldwell] now is the same testimony which was being sought on

April 8, 1970. All the pertinent facts relating to the matter then

in issue had been brought to the attention of this Court at the

time it entered its order on April 8, 1970 [relative to the March 16

subpoena].” (A. 100.) (3) On June 4, 1970, Judge Zirpoli ex

pressly ordered: “That the entire record of proceedings hereto

fore had [in connection with the March 16 subpoena] . . . , including

all subpoenas issued, motions made, affidavits, exhibits, documents,

briefs and other papers filed, proceedings had, rulings made, and

the Opinion and Order of the Court entered [on April 6 and

April 8, respectively] . . . is made a part of the record upon which

the Court will hear and determine movants’ Motion to Quash

Grand Jury Subpoena Served May 22, 1970.” (A. 102-103.)

(4) Judge Zirpoli’s order upon the motion to quash the May 22

subpoena was explicitly based on “the entire record of proceedings

previously had . . . relative to the March 16 subpoena.” (A. 104.)

(5) In replying to the order to show cause why he should not be

held in contempt for failure to respond to the May 22 subpoena

counsel for Mr. Caldwell explicitly relied upon the same record of

prior proceedings. (A. 108.) (6) Judge Zirpoli’s order adjudging

Mr. Caldwell in contempt again explicitly relied upon the same

record of prior proceedings. (A. 111.)

17

cerning information obtained by them in their professional

capacities, their confidential news sources are terrified of

disclosure and consequently shut up; that the mere appear

ance of a newsman in secret grand jury proceedings, where

what he has told cannot be known, destroys his credibility,

ruptures his confidential associations, and thereby irrepara

bly damages his ability to function professionally; and that

the resulting loss of confidence spreads rapidly and widely

to other newsmen, thus critically impairing the news

gathering capacities of the media and impoverishing the

fund of public information and understanding. Correspon

dents long experienced in dealings with militant and dissi

dent political groups averred that these elfects are particu

larly severe in the ease of such groups, naturally distrust

ful as they are, and fearful of government repression. In

addition, the affidavits detailed numerous specific episodes

in which compelled testimony by journalists had had the

immediate and drastic etfect of silencing their sources:

the very issuance of the subpoenas to Earl Caldwell that are

presently in issue frustrated newsmen’s interviews with

previously willing confidants concerning black militant af

fairs in several areas of the country, and entirely aborted

a proposed ABC documentary on the Black Panthers.

In his decision of April 8 according Mr. Caldwell a pro

tective order. Judge Zirpoli made express findings of fact

based upon these affidavits. After a painstaking review of

the entire record, the Court of Appeals affirmed Judge Zir-

poli’s major factual findings. We next recite those findings,

cite the convincing support that the record gives them, and

add explanatory factual details that the record also un-

controvertibly establishes.

Judge Zirpoli found, preliminarily:

“(1) That the testimony of Earl Caldwell sought to

be compelled by the subpoena . . . will relate to activi

ties of members of the Black Panther Party;”

18

and:

“(2) That Mr. Caldwell’s knowledge of those activi

ties derived in substantial part from statements and

information given to him, as a professional journalist,

by members of the Black Panther Party, vdthin the

scope of a relationship of trust and confidence.” (A. 95;

see also A. 104.)

These two points were accepted by the Court of Appeals^*

and are plainly correct.^^

The Court of Appeals recited that Mr. Caldwell “has become

a specialist in the reporting of news concerning the Black Panther

Party” and that “ [t]he Grand Jury is engaged in a general in

vestigation of the Black Panthers and the possibility that they

are engaged in criminal activities contrary to federal law.” (A.

114.) It approved the following statement of Mr. Caldwell’s

“history [as] . . . related in his moving papers:

“Earl Caldwell has been covering the Panthers almost since

the Party’s beginnings. Initially received hesitatingly and

with caution, he has gradually won the confidence and trust

of Party leaders and rank-and-file members. As a result,

Panthers will now discuss Party views and activities freely

with Mr. Caldwell. * * * Their confidences have enabled him

to write informed and balanced stories concerning the Black

Panther Party which are unavailable to most other newsmen.”

(A. 117; see also A. 122 n. 8.)

The Court of Appeals accordingly characterized Mr. Caldwell as a

“reporter who . . . uniquely enjoys the trust and confidence of his

sensitive news source” (A. 126), and it noted that the Government

has not disputed Mr. Caldwell’s sworn assertion that “there is

nothing to which he could testify (beyond that which he has al

ready made public and for which, therefore, his appearance is un

necessary) that is not protected by the District Court’s order” (A.

125)—i.e., nothing that did not derive from “confidential associa

tions, sources or information received, developed or maintained by

him as a professional journalist in the course of his elforts to gather

news for dissemination to the public through the press or other

news media” (A. 96).

“ That the subject of the grand jury inquiry is the activities of

the Black Panthers appears (1) from the duces tecum rider to the

first, February 2 subpoena served on Mr. Caldwell (A. 20; see pp.

19

Judge Zirpoli further found:

“ (3) That confidential relationships of this sort are

commonly developed and maintained by professional

journalists, and are indispensable to their work of

gathering, analyzing and publishing the news.” (A. 95;

see also A. 104.)^“

Indeed, the record establishes that newsmen in every

medium, covering every aspect of the news-domestic and

foreign affairs, the operations of government from the

police station to the White House, the activities of political

militants, presidential candidates, the F.B.I. and the Penta-

5-6 supra) ; and (2) from the first and last paragraphs of the Gov

ernment’s Memorandum in Opposition to Motion to Quash Grand

Jury Subpoenas, and the affidavits of Government attorneys Fran

cis L. Williamson, Esq., and Victor C. Woerheide, Esq., attached

thereto (A. 62-73).

Mr. Caldwell’s affidavit establishes that his only knowledge of

the Black Panthers comes through the confidential relationships

that he has established and maintained with them in his capacity

as a professional journalist. (A. 17-19.) It describes the develop

ment and nature of those relationships in detail. {Ibid.; see also

pp. 4-5 su-pra.)

“The Black Panther Party’s method of operation with re

gard to members of the press is significantly different from

that of other organizations. For instance, press credentials are

not recognized as being of any significance. In addition, in

terviews are not normally designated as being ‘backgrounders’

or ‘off the record’ or ‘for publication’ or ‘on the record.’ Be

cause no substantive interviews are given until a relationship

of trust and confidence is developed between the Black Pan

ther Party members and a reporter, statements are rarely made

to such reporters on an expressed ‘on’ or ‘off’ the record basis.

Instead, an understanding is developed over a period of time

between the Black Panther Party members and the reporter

as to matters which the Black Panther Party wishes to dis

close for publications and those matters which are given in

confidence.” (A. 18, quoted by the Court of Appeals at A 122

n. 8.)

The Court of Appeals added:

20

gon—depend critically upon such confidential relationships.

(A. 41-42, 52-53, 54, 55-58, 59-60, 61.) The relationships

are subtle, involving the growth of trust and understanding

between a newsman and his news sources. (A. 18-19, 39-40,

41-42.)^ ̂ Walter Cronkite thus describes the function of

the information communicated with these relationships:

“In doing my work, I (and those who assist me)

depend constantly on information, ideas, leads and

opinions received in confidence. Such material is es

sential in digging out newsworthy facts and, equally

important, in assessing the importance and analyzing

the significance of public events. Without such ma-

“ . . . The very concept of a free press requires that the news

media be accorded a measure of autonomy; that they should be

free to pursue their own investigations to their own ends with

out fear of governmental interference, and that they should be

able to protect their investigative processes. To convert news

gatherers into Department of Justice investigators is to in

vade the autonomy of the press by imposing a governmental

function upon them. To do so where the result is to diminish

their future capacity as news gatherers is destructive of their

public function.” (A. 120.)

The Court of Appeals quoted the following description of these

sorts of relationships from one newsman’s afSdavit (A. 41-42) :

“ . . . [0]n every story there is a much subtler and much more

important form of communication at work between a reporter

and his sources. It is built up over a period of time working

with and writing about an organization, a person, or a group

of persons. The reporter and the source each develops a feel

ing for what the other will do. The reporter senses how far

he can go in writing before the source will stop communicat

ing with him. The source, on the other hand, senses how much

he can talk and act freely before he has to close off his pres

ence and his information from the reporter. It is often

through such subtle communication that the best and truest

stories are written and printed in The Times, or any other

newspaper.” (A. 122 n. 8.)

Mr. Caldwell’s own description of his confidential relationships

with Black Panther sources is set forth in note 19, supra.

21

terials, I would be able to do little more than broadcast

press releases and public statements.” (A. 52.)

(See also A. 55-57, 59, 61.)

These sorts of confidential relationships are particularly

important to reporters in the black community.^^ “Because

of the cohesiveness of the black activist community a re

porter’s credibility is peculiarly important. . . . To cover

black activist groups effectively it is necessary for a re

porter to establish their confidence in him so that one per

son will tell another, ‘I know him. I can vouch for him.’ ”

(A. 22.) (See also A. 24-25.) Especially in dealings with

militant groups, the relationships are indispensable.'® “Be

cause the Panthers and other dissident groups feel op

pressed by established institutions, they will not speak with

newspapermen until a relationship of complete trust and

confidence has been developed.” (A. 17.) “The only possible

way to overcome [militants’] . . . reluctance ['to confide in

reporters] is to build up—often slowly and meticulously—

a personal relationship with radicals and dissidents who

trust you.” (A. 39.)

Judge Zirpoli found:

“(4) That compelled disclosure of information re

ceived by a journalist within the scope of such confiden

tial relationships jeopardizes those relationships and

thereby impairs the journalist’s ability to gather, an

alyze and publish the news.” (A. 95; see also A. 104.)

" In recent years, black activists have come increasingly to dis

trust, and to cease to relate to, white newsmen. (A. 34, 41.)

Like blacks, militants generally have become increasingly dis

trustful of reporters in recent years. (A. 18-19, 39.) In part, this

distrust appears to have been occasioned by disclosures that P.B.I.

agents and other law enforcement officials have posed as reporters

(A. 19, 22.) F

22

The Court of Appeals agreed that “['t]he affidavits con

tained in this record required [that] . . . conclusion.”

(A. 118.)̂ ̂ As John Kifner put it:

The following affidavits are examples. (See also pp. 24-30

infra.) In each ease, the newsman’s conclusions are supported by

specific episodes drawn from his considerable journalistic experi

ence ; and his entire affidavit should be read, although only its ulti

mate conclusions are set forth here:

Walter Cronkite (A. 53) ;

unable to obtain much of the material

that is indispensable to my work if it were believed that people

could not talk to me confidentially. I certainly could not work

effectively if I had to say to each person with whom I talk that

any information he gave me might be used against him.

“ . . . On the basis of the foregoing and my experience as a

news correspondent, it is my opinion that compelling news

correspondents to testify before grand juries with respect to

matters learned in the course of their work would largely de

stroy their utility as gatherers and analysts of news.”

Eric Sevareid (A. 54) :

“ . . . Many people feel free to discuss sensitive matters with

me in the knowledge that I can use it with no necessity of

attributing it to anyone. This relationship has always been

particularly the case for columnists or commentators.

“ . . . Should a widespread impression develop that my

information or notes on these conversations is subject to claim

by government investigators, this traditional relationship es

sential to my kind of work, would be most seriously jeopar

dized. I would be less well informed, myself, and of less use

to the general public as an interpretor or analyst of public

affairs.”

Mike Wallace (A. 55, 57-58):

“In my experience in investigative news gathering the abil

ity to establish and maintain the confidence of people who may

be willing to suggest leads and divulge facts and background

information to me has been essential. If such people believed

that I might, voluntarily or involuntarily, betray their trust

by disclosing my sources or their private communications to

me, my usefulness as a reporter would be seriously diminished.

“ [After reciting instances:] In each of the foregoing in

stances, I was able to do my work because people felt assured

23

“Based upon my experience as a news reporter, it is

clear to me that when reporters covering dissenting

forces in society are forced to testify about them, their

neutrality is compromised and all confidence in them is

lost. Before a person will talk openly to a reporter, he

must believe that the reporter will respect what is told

that their confidences would be respected. If I were now forced

to reveal such confidential information, I could never again

count on the cooperation of those people or anyone else in

developing similar material in the future. In my opinion the

public would be the loser in the long run.”

Ban Bather (A. 60) :

“ . . . The fear that confidential discussions may be divulged,

as a result of grand jury subpoenas or otherwise, would curtail

a reporter’s ability to discover and analyze the news. This is

not mere speculation on my part. In recent weeks, a long-time

friend and news source, who has dealt in confidence with me

for more than a dozen years, has declined to do so. He has,

on many occasions in the past, been responsible for truths,

otherwise unobtainable, appearing in my reporting on civil

rights, government and politics. This decent, honest citizen,

who cares deeply about his country, has now told me that he

fears that pressure from the Government, enforced by the

courts, may lead to violations of confidence, and he is there

fore unwnlling to continue to communicate with me on the

basis of trust which formerly existed between us. This inci

dent is representative of the loss that reporters and those who

depend upon them for truth will suffer if reporters can be

forced to disclose confidential communications and private

sources. The very possibility of such forced disclosure is, in

my experience, sufficient to foreclose important channels of

communication.”

Marvin Kalh (A. 61) :

“ . . . I f my sources were to learn that their private talks

with me could become public, or could be subjected to outside

scrutiny by court order, they would stop talking to me, and

the job of diplomatic reporting could not be done.”

Martin Arnold (A. 42) ;

“ . . . If it becomes known that a reporter is willing to tell

a Government agency what he has heard or learned or saw,

his usefulness will be destroyed because news sources will no

longer speak to him.”

24

in confidence. The threat that the reporter my have to

disclose such confidences has a chilling effect on his

relationships with news sources and, in my opinion,

could eventually destroy any possibility of a free flow

of information.” (A. 27.)

Newsmen having specialized experience with black mili

tant groups affirm that relationships with such groups par

ticularly, would he destroyed if a reporter appeared under

subpoena to testify before a government agency investi

gating them.^ ̂ The Court of Appeals concluded that:

“The affidavits on file cast considerable light on the

process of gathering news about militant organizations.

It is apparent that the relationship which an effective

privilege in this area must protect is a very tenuous

and unstable one. . . . The relationship depends upon

a trust and confidence that is constantly subject to re

examination and that depends in turn on actual knowl

edge of how news and information imparted have been

handled and on continuing reassurance that the han

dling has been discreet.” (A. 122-123.)̂ ®

Finally, Judge Zirpoli found:

“(5) Specifically, that in the absence of a protective

order by this Court delimiting the scope of interroga-

A. 24-25, 31, 37-38. See, e.g., the affidavit (A. 22-23) quoted

by the Court of Appeals (A. 123 n. 8) :

“From my experience, I am certain that a black reporter

called upon to testify about black activist groups will lose his

credibility in the black community generally. His testifying

will also make it more difficult for other reporters to cover that

community. The net result, therefore, will be to diminish seri

ously the meaningful news available about an important seg

ment of our population.”

26 See A. 24-25, 26-27, 32-33, 39-40, 41-42.

25

tion of Earl Caldwell by the grand jury, his appear

ance and examination before the jury will severely im

pair and damage his confidential relationships with

members of the Black Panther Party and other mili

tants, and thereby severely impair and damage his

ability to gather, analyze and publish news concerning

them; and that it will also damage and impair the

abilities of other reporters for The New York Times

Company and others to gather, analyze and publish

news concerning them.” (A. 95; see also A. 104-105.)”

And the Court of Appeals found that these same harms

would follow Mr. Caldwell’s grand jury appearance even

under shelter of the District Court’s protective order, be

cause the assurance of confidence required by a reporter in

order to maintain the trust of militant news sources

“ . . . disappears when the reporter is called to testify

behind closed doors. The secrecy that surrounds Grand

Jury testimony necessarily introduces uncertainty in

the minds of those who fear a betrayal of their confi

dences. These uncertainties are compounded by the

subtle nature of the journalist-informer relation. The

demarcation between what is confidential and what is

for publication is not sharply drawn and often depends

upon the particular context or timing of the use of the

” Following its study of the entire record, the Court of Appeals

took the same view, as quoted from Mr. Caldwell’s papers:

'Tf Mr. Caldwell were to disclose Black Panther eojsfidences

to governmental officials, the grand jury, or any other person,

he would thereby destroy the relationship of trust wliieh he

presently enjoys with the Panthers and other militant groups.

They would refuse to speak to him; they would become even

more reluctant than they are now to speak to any newsmen ,-

and the news media would thereby be vitally hampered in

their ability to cover the views and activities of the militants ”

(A. 117.)

26

information. Militant groups might very understand

ably fear that, under the pressure of examination be

fore a Grand Jury, the witness may fail to protect their

confidences with quite the same sure judgment he in

vokes in the normal course of his professional work.”

(A. 123.)

These conclusions, also, are fully sustained by the record.

Mr. Caldwell’s sworn, categorical assertion that his com

pelled appearance before a federal grand jury investigating

the Black Panthers would completely destroy his confiden

tial association with the Panthers and with other militant

groups^®—that, “if I am forced to appear in secret grand

jury proceedings, my appearance alone would be interpre

ted by the Black Panthers and other dissident groups as a

possible disclosure of confidences and trusts and would

. . . destroy my effectiveness as a newspaperman” — ŵas

seconded by other experienced journalists. (A. 22-23, 37-38.)

Thomas Johnson, another black New' Yorh Times reporter

with eleven years of journalistic experience, gave this

opinion:

“Based on my own experiences, being black and

knowing the black community, I can say with certainty

that any appearance by a black journalist behind closed

doors, such as the appearance that Earl Caldwell . . ,

has been subpoenaed to make before a Grand Jury,

would severly ['sic] damage his credibility in the black

community. . . .” (A. 25.)

Trust or distrust of particular reporters is widely conveyed

from one militant group to another. (See A. 22.) “ [Sjuspicion and

distrust travels rapidly in the Movement. Violate one man’s con

fidence and sources start drying up all over the place.” (A. 40.)

(A. 19.) Quoted by the Court of Appeals at A. 122-123 n.8.

21

The destruction of Mr. Caldweirs credibility would taint

other JVew York Times reporters as well,®" and would dis

able the Times from gathering “information required to

report on the Black Panther Party and dissident groups

effectively.” (A. 34.)

These are not at all conjectural fears. This record is re

plete with concrete and specific descriptions of the actual

reactions of confidential news sources to the recent rash of

federal subpoenas issued to reporters in connection with

investigations of militant political groups." Citing specif

ically their fear of subpoenas, previously willing informants

concerning militant matters have been reluctant or entirely

unwilling to be interviewed by newsmen. (A. 44-45, 49-50;

see also A. 60.) Following the service of the February 2

subpoena upon Earl Caldwell, Newsweek’s Massachusetts

Bureau Chief was unable to secure the cooperation of a

formerly useful source of black militant information in an

interview. (A. 46-47.) The Times criminal justice corres-

The case of New York Times Reporter Anthony Ripley dra

matically demonstrates the spreading effect of distrust of reporters

by militants following one reporter’s compelled testimony. On -Tune

3, 1969, Mr. Ripley was subpoenaed to testify before the House

Internal Security Committee because of news stories that he wrote

about the 1968 S.D.S. national convention. The result was not only

total destruction of Mr. Ripley’s own relationships with militants,

and of his ability to cover militant activities (A. 32-33), but severe

impairment of the ability of other Times reporters to relate to or

cover the S.D.S. (A. 24, 26-27, 41-42), and exclusion of the entire

“establishment press” from the 1969 S.D.S. convention (A. 26-27).

" The federal subpoenas were the subject of a press release by

Attorney General John Mitchell on February 5, 1970, reprinted in

The New York Times, Friday, February 6, 1970, p. 40, col. 4. They

are discussed in New York Times articles of Sunday, February 1,

1970, p. 24, col. 1 Tuesday, February 3, 1970, p. 20, col. 6; Wednes

day, February 4, 1970, p. 1, col. 1; Thursday, February 5, 1970,

p. 1, col. 2; Friday, February 6, 1970, p. 1, col. 7. And see the

resolution of the Board of Directors of Sigma Delta Chi, adopted

at the annual Spring meeting of the journalists’ association, April

24-25, 1970, reported in The Quill, June, 1970, p. 38.

28

pondent in New York City found tkat kis news sources

were unwilling to discuss sensitive matters in connection

witk kis attempts to cover Black Pantker activities in

Brooklyn and otker stories. (A. 43.) In Los Angeles, a

Newsweek correspondent wko kad tkeretofore kad good

relations witk tke local Pantker office was refused an

interview unless and until ke was cleared by tke Pantker

Party Headquarters in Berkeley. He was finally cleared

after giving Newsweek’s and kis own assurances tkat tkey

kad and would resist Government attempts to secure inter

view materials by subpoena; but by the time this clearance

came through, the news source that he wanted to interview

had left Los Angeles, and the correspondent was unable to

contact him. (A. 30-31.) In San Francisco, an ABC tele

vision team dispatched to the West Coast to do a docu

mentary on the Panthers was refused cooperation first by

the Black Panther Party and subsequently by the Oakland

Black Caucus in the absence of assurances that ABC would

fight Government subpoenas of out-takes®* “to the highest

court possible.” (A. 28.) As a result, the proposed docu

mentary was aborted. (A. 28-29, 37.) In each of these in

stances, the refusal of news sources to cooperate was ex

pressly based upon fears generated by the Caldwell and

related subpoenas.

Newsmen uniformly agree that, if they were compelled to

testify under such subpoenas, the effect would be gravely to

impair their ability to cover militant political views and

activities. (A. 22-23, 27; see also A. 57-58, 60.) “Already,

there are relatively few reporters who are trusted suf

ficiently by radicals to report their activities. If these

reporters are discredited one after another, the public’s

right to know will be drastically infringed.” (A. 40.)

“Out-takes” are films shot in the course of producing a tele

vision show but not actually shown as part of the televised show.

(A. 28.)

29

“ As a result of the type of probing that the

Government is currently undertaking, it is becoming

increasingly difficult for reporters to gather any in

formation whatsoever about the activities of the various

so-called radical black and white organizations and,

therefore, readers of The Times and other publications

are not getting all the information required by them

to make their own judgments on what is going on on

various aspects of American life.” (A. 42.)

Walter Cronkite summed the matter up more broadly,® ̂with

characteristic precision:

“On the basis of . . . my experience as a news corres

pondent, it is my opinion that compelling news cor

respondents to testify before grand juries with respect

to matters learned in the course of their Avork would

largely destroy their utility as gatherers and analysts

of news. Furthermore, once it is established and be

lieved that news correspondents are to be utilized in

grand jury investigations, they will be of precious little

value to such investigations because they will no longer

The destructive impact of subpoenaing reporters is not lim

ited to their ability to cover militant political matters, although it

is peculiarly intense in that area. Indeed, as one newsman’s affi

davit makes plain, a more insidious danger is that compulsory

process issued in the course of governmental inAmstigations will re

press sources of information within government concerning goÂ-

ernmental abuses and wrongdoing:

“Particularly disturbing to me has been a marked increase,

recently, in the reticence of my confidential sources in govern

ment itself. These sources, some of whom have in the past

been instrumental in exposing instances of governmental abuse

or corruption, now tell me that, because of the increasingly

widespread use of subpoenas to obtain names and other confi

dential information from reporters, they are fearful of re

prisals and loss of jobs if they are identified by their superiors

as sources of information for newsmen.” (A. 45.)

(See also A. 43.)

30

have access to information that grand juries might

want.” (A. 53.)

Nothing was presented by the Government in the District

Court to disparage this substantial showing that Mr. Cald-

well’s compelled appearance before the grand jury would

have gravely damaging consequences on the p r e s s . T h e

The Government made three factual submissions in this re

gard :

First, it showed that Mr. Caldwell had persistently declined to

talk to F.B.I. agents prior to the service of the first grand jury

subpoena upon him. (A. 79; see note 3, supra.) The point ap

pears to be that if Mr. Caldwell had consented to an F.B.I. inter

view, he might not have been subpoenaed. But a private F.B.I.

interview would have had the same destructive effects upon Mr.

Caldwell’s confidential associations with black militants as a secret

grand jury appearance (see, for example A. 48-49), and, indeed,

would have opened him to the considerable dangers of being sus

pected as an F.B.I. spy (see note 23,, supra).