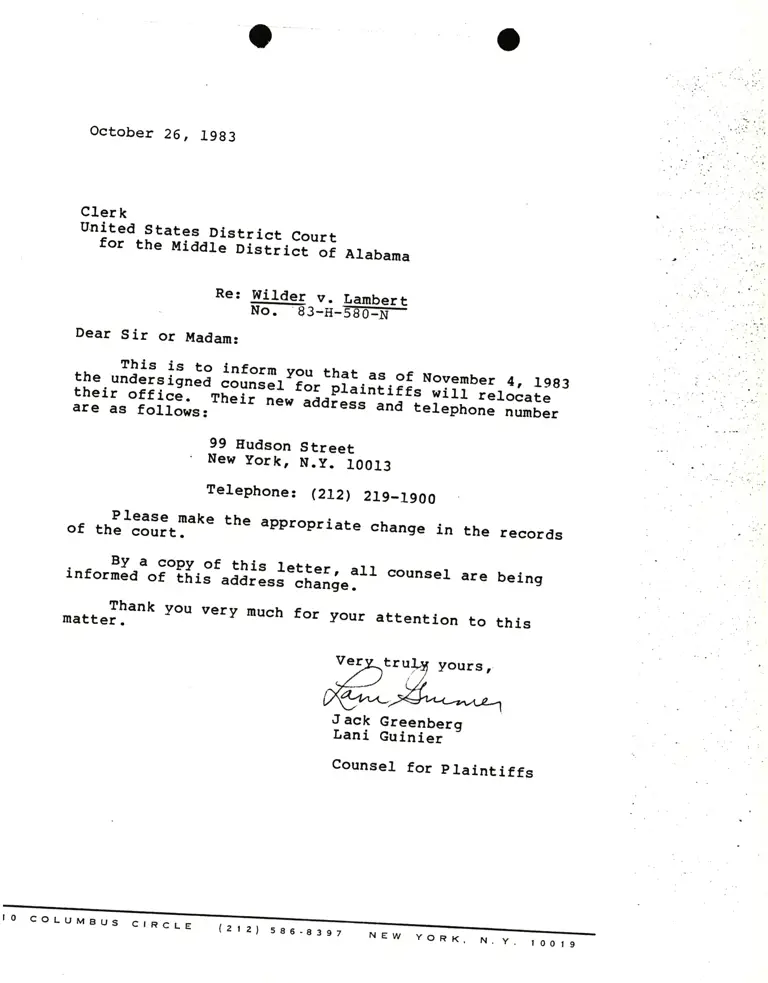

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Clerk (Middle District of Alabama District Court) Re: Wilder v. Lambert

Public Court Documents

October 26, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Clerk (Middle District of Alabama District Court) Re: Wilder v. Lambert, 1983. 699e7af8-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/20925bed-d069-4c01-9d78-d03b28803175/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-clerk-middle-district-of-alabama-district-court-re-wilder-v-lambert. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

October 26, I9g3

CIer k

United States-District Courtfor rhe Middt;-;i;ir-rfi*or Atabama

Re: Wilder v. LambertNo. B3_H-E-90-il.

Dear Sir or Madam:

This is to inform you that as of November 4r l9g3the undersioned-""ri".r'ior

_prai'trii" wirr rerocate:l: r:" "f:ii:j;

-r[Ii, -ii,.aaai

";;..;;

-

; er ephone n umber

99 Errdson Street. New yorkr N.y. -ioofg

Telephone: eL2) 219_1900

of .nlt33ii.T"*" the appropriare chanse in rhe reeords

By a copy.of this letterr all count'nformed or Erris .aa-rl""-=Ih.ng". ""1 are being

,"aa.Ilank you very much for your attention to this

g".f Greenberg

Lani Gulnler

Counsel for plaintiffs

IO COLUMBUS CIRCLE lzrzl 586-8397 NEW YoRK, N. Y. rootg