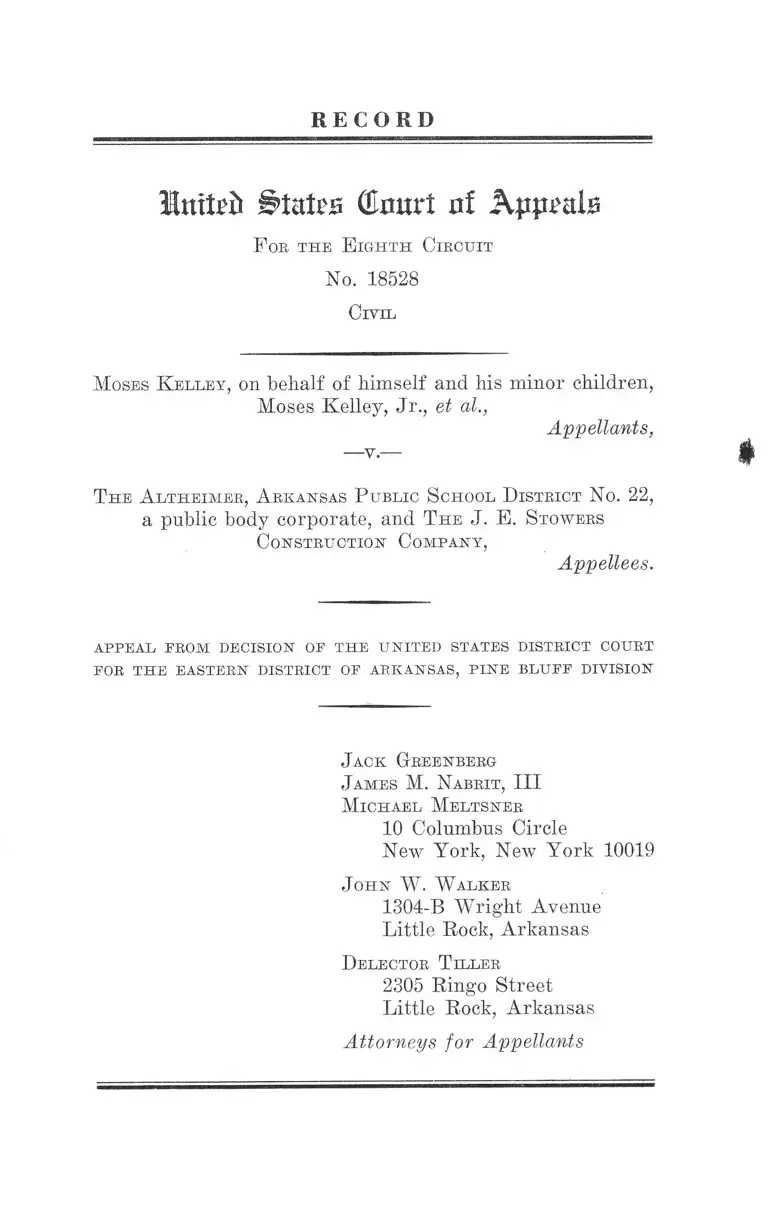

Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22 Record on Appeal

Public Court Documents

February 15, 1966 - July 5, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. The Altheimer, Arkansas Public School District No. 22 Record on Appeal, 1966. 759002bc-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/210054f5-c213-4879-bc5e-110574a2d72a/kelley-v-the-altheimer-arkansas-public-school-district-no-22-record-on-appeal. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

R E C O R D

Intiwi States (Court of Appralo

F or t h e E ig h t h C ir c u it

No. 18528

C iv il

M oses K e l l e y , on b e h a l f o f h im s e lf a n d h is m in o r c h ild re n ,

Moses Kelley, Jr., et al.,

Appellants,

- V - t

T h e A l t h e im e r , A rk a n sa s P u blic S ch o o l D is t r ic t N o. 22,

a public body corporate, and T h e J. E. S tow ers

C o n st r u c t io n C o m pa n y ,

Appellees.

A P P E A L ERO M D E C IS IO N O F T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E E A S T E R N D IS T R IC T OF A R K A N SA S, P IN E B L U F F D IV IS IO N

J ack G reen b er g

J am es M. N a b b it , III

M ic h a e l M e l t s n e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n AY. W a lk er

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas

D electo r T il l e r

2305 Ringo Street

Little Rock, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries ............................................... 1

Complaint (Piled Feb. 15, 1966) .................................... 3

Motion for Preliminary Injunction .............................. 9

Motion to Intervene as Plaintiffs ............. ..................... 10

Answer of Altheimer School District No. 22 ........... 12

Separate Answer of J. E. Stowers Construction Com

pany .............................................................................. 14

Plaintiffs’ Answers to Interrogatories by Defendant

Altheimer School District No. 22................................ 16

Preliminary Pre-Trial O rder......................................... 19

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s Response

to Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions ..................... 22

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s Response

to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories ............... 27

Deposition of Dr. Myron Lieberman...................... 36

Plaintiffs’ Educational Expert Witness (April

30, 1966)

Stipulation ............................................................... 36

Direct Examination ................................................. 37

Cross Examination ................................................. 67

Redirect Examination ......... 99

Reporter’s Certification ........................................ 103

PAGE

Transcript of Hearing (March 31, 1966) ......... ........ 104

Testimony of Fred Martin, Jr., Principal of the

Martin Schools ....................................... 105

Testimony of James D. Walker, Superintendent

of Schools ........ 118

Reporter’s Certification .......................... 226

Memorandum Opinion of J. Smith Henley, D.J. (June

3, 1966) .......... 227

Judgment (June 3, 1966) ............................................... 249

ii

I s THE

United States Siateirt (to rt

E a s t e r s D ist r ic t of A rk a n sa s

P i s e B l u e r D iv is io n

Civil Action No. PB-66-C-10

M oses K e l l e y , on behalf of himself and his minor children,

Moses Kelley, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs,

T h e A l t h e im e r , A rk a n sa s P u b l ic S ch o o l D ist r ic t No. 22,

a public body corporate, and T h e J. E. S tow ers

C o n str u c tio n C o m pa n y ,

Defendants.

Relevant D ocket Entries

2-15-1966—Complaint filed.

2- 17-1966—Motion for Preliminary Injunction filed.

3- 4—1966—Answer filed by Altheimer School District.

3- 4-1966—Interrogatories by Defendant Altheimer Public

School District filed, directed to all plaintiffs.

3- 5-1966—Separate Answer of J. E. Stowers Construction

Company filed.

3- 5-1966—Statement in Opposition to Motion for Prelim

inary Injunction filed by Stowers Const. Co.

3- 7-1966—Memorandum in Support of Motion for Prelim

inary Injunction filed.

3- 8-1966—Letter Preliminary Pre-Trial Order filed.

2

Relevant Docket Entries

3-10-1966—Requests for Admissions filed by plaintiffs.

3-10-1966—Interrogatories filed by plaintiffs, directed to

School District.

3-10-1966—Anwers to Interrogatories filed by plaintiffs.

3-22-1966—Response to Interrogatories Propounded to de

fendant Altheimer School District filed.

3-22-1966—Response to Request for Admissions filed by

Altheimer School District.

3-31-1966—Court Trial begun at 10:00 a.m., before Hen

ley, J. All testimony and arguments completed

at 6:20 p.m. Permission granted to plaintiffs’

counsel to intervene for other persons. Case

submitted.

5- 3-1966—Motion to Intervene filed.

5- 25-1966—Deposition of Dr. Myron Lieberman filed.

6- 3-1966—Memorandum Opinion by Henley, J. filed.

6- 3-1966—Judgment filed dismissing complaint.

7- 5-1966—Notice of Appeal filed by plaintiffs. Copies to

counsel for defendants by clerk.

3

Complaint

(Filed Feb. 15, 1966)

I

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

Title 28 U.S.C. §1343 (3) (4), this being a suit in equity

authorized by law, Title 42 U.S.C. §1983, to be commenced

by any citizen of the United States or other person thereof

to redress the deprivation under color of law of rights,

privileges and immunities secured by the Constitution and

laws of the United States. The rights, privileges and im

munities herein sought to be redressed are those secured

by the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses of the

Constitution of the United States.

II

This is a proceeding for a preliminary and a permanent

injunction enjoining defendant Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22 and defendant J. E. Stowers Con

struction Company from continuing plans to construct,

and from constructing, separate public elementary schools

for white and Negro elementary students. This is also

a proceeding for a temporary and permanent injunction

enjoining defendant Altheimer School District from con

tinuing the policy, practice, custom and usage of assigning

pupils, faculty and administrative staff on a racially dis

criminatory basis and from otherwise continuing any

policy or practice of racial discrimination in the opera

tion of the Altheimer school system.

III

The plaintiffs in this case are Negro citizens of the

United States and of the State of Arkansas who reside

4

in Altheimer, Arkansas. Adult plaintiffs are property-

owners and taxpayers in the community of Altheimer, Ar

kansas. Adult plaintiffs bring this action on behalf of

themselves, the minor plaintiffs whose names are set out

below who attend and are eligible to attend public schools

in defendant school district, and on behalf of all other

persons similarly situated.

The plaintiffs are: (1) adult Moses Kelley and his

minor children, Moses Kelley, Jr.—Age 10, grade 4; Katie

Bell Kelley—Age 9, grade 3; and Lillian Kelley who will

be age 5 when she enters grade 1 in September, 1966;

(2) adult Cardell Hannah and his minor grand child,

Sheila B. Hannah, age 9, grade 4; (3) adult Climmie Rig

gins and his minor children, Lois Jean Riggins—age 10,

grade 4; Deborah Ann Riggins—age 9, grade 3, Howard

Edward Riggins—age 6, grade 1; (4) adult Theodore

Wyatt and his charge, James Etta Austin—age 12, grade 6;

and (5) adult Floyd Thomas.

IV

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 is a public

body corporate which owns, operates and otherwise main

tains that Altheimer Public School System. James Walker

is Superintendent of School of defendant school district.

Defendant J. E. Stowers Construction Company is a

privately owned building construction company which was

organized, is operating under, and is subject to, the

laws of the State of Arkansas.

V

Defendant School District has historically operated a

racially segregated system of public schools for Negro

Complaint

5

and white pupils in every respect including pupil and

teacher assignments. Historically and presently, the schools

operated by defendant school district for Negro pupils

have been substantially inferior in all respects to the

schools operated by defendant school district for white

pupils.

VI

In 1965, defendant began a program of pupil desegrega

tion using the “freedom of choice” approach. Under this

plan, a few Negro pupils now attend the formerly all-white

schools. The other approximately nine hundred Negro

pupils in the district attend the all-Negro Martin Ele

mentary and high school. Said Martin school has neither

white pupils staff.

Complaint

VII

Although defendant Altheimer School District No. 22

has committed itself to the Department of Health, Educa

tion and Welfare to ending racial segregation, defendants

district has planned and is about to have defendant J. E.

Stowers Construction Company construct new school facil

ities which will perpetuate racial segregation. Specifically,

defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 plans to replace

the present inadequate and inferior Negro elementary

school with a new, air-conditioned “Negro” school to be

located on the site of the present predominantly Negro

elementary school.

VIII

Plaintiffs allege on information and belief that the de

fendant Altheimer School District No. 22 has entered

6

into a contract for the construction of the two elementary

schools with the defendant J. E. Stowers Construction

Company located at 501 North University Street in Little

Rock, Arkansas. Pursuant to the terms of said contract,

defendant school district will construct two schools to

replace the Martin (all-Negro) and Altheimer (predomi

nantly white) schools. The buildings will consist of a total

of twenty-four classrooms, two offices and restroom facil

ities and will be located within six blocks of each other.

Defendant J. E. Stowers Construction Company has con

tracted to construct said facilities at a total cost of $257,331

and has committed itself to complete said facilities by the

beginning of the 1966-67 school term.

IX

Plaintiffs further allege on information and belief that

the defendant school district’s plans for teacher desegre

gation are too vague, too indefinite and too uncertain to

afford minor plaintiffs the relief of teacher desegregation

to which they are now entitled under relevant case law.

X

Plaintiffs allege on information and belief that the “free

dom of choice” pupil assignment system now in use by

defendant district is incapable of desegregating defendant

district; and is also incapable of affording plaintiffs and

other members of plaintiffs class the relief to which they

are now entitled. Minor plaintiffs and members of their

class have been denied and are being deprived of rights

secured to them by the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution solely because of their race

or color. Plaintiffs have no plain, adequate or complete

Complaint

7

remedy at law to redress these wrongs and this suit for

injunctive relief is the only means of securing adequate

relief. Plaintiffs stand to suffer irreparable injury from

defendants unless defendants are enjoined by this Court

from continuing the practices herein complained about.

Wherefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that this court

advance this cause on the docket, order a speedy hearing

of the cause according to law and equity and, after such

hearing, enter a preliminary and permanent injunction

enjoining:

(1) defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 and

defendant J. E. Stowers Construction Company from pro

ceeding further toward construction of separate elementary

school facilities for Negro pupils and for white pupils;

(2) defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 from

disbursing any funds or other property to defendant J. E.

Stowers Construction Company for the purpose of school

construction so long as defendant school district persists

with it’s present construction plans;

(3) defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 from

approving budgets, making funds available, approving em

ployment contracts and construction programs, and other

policies, curricula and programs designed to perpetuate,

maintain or support a racially discriminatory school sys

tem;

(4) defendant Altheimer School District 22 from paying

Negro teachers lower salaries than the salaries paid to

white teachers;

(5) defendant Altheimer School District No. 22 from

continuing its present “freedom of choice” pupil desegrega

Complaint

8

tion policy; and from any and all other policies or prac

tices established on the basis of the race or color of either

the teachers or pupils in defendant district.

Plaintiffs further pray that this Court allow them their

costs herein, reasonable attorney’s fees and such other,

additional or alternative, relief as may appear to the Court

to be equitable and just.

Complaint

9

(Filed Feb. 17, 1966)

Plaintiffs in the above styled cause move the Court for a

preliminary injunction enjoining defendant Altheimer Pub-

lice School District No. 22 and defendant J. E. Stowers

Construction Company from proceeding- further toward

construction of separate school facilities for white and

Negro pupils in Altheimer, Arkansas.

Wherefore, upon the complaint filed in this cause on

February 16, 1966, plaintiffs move this court for a prelimi

nary injunction as prayed for in said Complaint and on

the grounds therein set forth.

Motion for a Preliminary Injunction

10

(Filed May 3, 1966)

Pursuant to an oral motion by undersigned counsel at

the trial of this cause come now the parties whose names

are set out below and respectfully move the court to permit

them to intervene in the above styled action. For cause,

the parties praying to intervene show the court that they

are Neg*ro parents and their children who reside in the

Altheimer School District; That minor intervenors attend

and are eligible to attend the Altheimer Public Schools;

that the complaints made by plaintiffs in this cause are

identical with the complaints of the intervenors; and that

the relief prayed for herein as set forth in plaintiff’s com

plaint is also identical.

The intervenors in this cause are as follows:

Earlie Armstrong, on behalf of himself and his minor

children Deborah Ann Armstrong, Rickey Armstrong,

and Jackie Lynn Armstrong; Allen Freeman, on behalf

of himself and his minor children Allen Freeman, Jr.,

and Melvin Freeman; Joe Armstrong, on behalf of

himself and his minor children Branda Armstrong and

Darlene Bishop;

Columbus Manning, on behalf of himself and his minor

child Dargame Bingham; Mrs. Jewell Dillard, on behalf

of herself and her minor children Jereline Dillard and

Sandra Kay Dillard; Roosevelt Reams, on behalf of

himself and his minor children Roosevelt Reams, Jr.,

Eddie Lee Reams, Andrew Lee Reams, Amelia Reams,

and Beatrice Reams ;

John H. Russell, on behalf of himself and his minor

child Harold Russell; Arlee Jones, on behalf of him

self and his minor children Ernest Lee Jones and

Motion to Intervene as Plaintiffs

11

Vernita Jones; Mrs. Naomi Jynes, on behalf of herself

and her minor children Charles Akins, Alphonso Phil-

mon, Rosa M. Philmon, and Johnny L. Jynes; Amos

Jones, on behalf of himself and his minor child James

Hudson;

George Britter, on behalf of himself and his minor chil

dren Ruble Lee Britter, Joyce Lee Britter, George Brit

ter, Jr., and Caloyn Ann Britter; Mrs. Marie Colemon,

on behalf of herself and her minor children Shirley

Colemon, Ella Colemon, Lula Colemon, and Lawrence

Colemon; C. Daniel, on behalf of himself and his minor

children M. Daniel, C. Daniel, Jr., Robert Lee Daniel,

and H. Daniel;

Mrs. Mary Crater, on her behalf and her minor child

Josephine Crater; Miss Betty Davis on her behalf and

her minor children Stanly Davis and Reginald Davis;

and Thomas Price on behalf of himself and his minor

children Charles Price, Eurania Price, and Juanita

Price.

WHEREFORE, intervenors respectfully pray that this court

permit them to adopt and adapt the original complaint in

this cause as their own and for such relief as is prayed for

therein.

Motion to Intervene as Plaintiffs

12

(Filed March 4, 1966)

Comes the defendant, Altheimer, Arkansas, School Dis

trict No. 22, and for its separate answer to the complaint

of the plaintiffs herein states:

1. That it admits the allegations set forth in Paragraph

IV of the plaintiffs’ complaint and it admits that portion

of Paragraph V of the complaint which alleges that the

defendant School District has, prior to the school year be

ginning in September of 1965, operated a racially segre

gated system of public schools for Negro and white pupils

and so much of Paragraph VI as alleges that the defendant

School District adopted a policy of desegregation of the

schools of the District using the “freedom of choice” method

and the plan for doing so has been approved by the Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare pursuant to the

authority and responsibility vested in that Department by

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U. S. C. Sec. 1971 et seq.).

2. Further answering, the defendant School District

states that prior to the commencement of this suit by the

plaintiffs it entered into a contract with J. E. Stowers Con

struction Company for the construction of two new ele

mentary school buildings for a total contract price of Two

Hundred Fifty-seven Thousand Three Hundred Thirty-one

Dollars ($257,331.00). Public notice of the intention and

plans for the construction of these buildings has been given

throughout the School District for many months and were

specifically outlined as the basis for an increased millage

levy and bond issue which was submitted for approval by

the patrons of the District on September 28, 1965, at the

annual school election. Until the filing of this suit, no notice

Answer of Altheimer School District No. 22

13

was given to the defendant School District of any objection

on the part of any patron or pupil in the District to the

proposed construction, and by reason of the failure of these

plaintiffs to act upon notice and knowledge available to

them so as to prevent the District from becoming obligated,

as it now is, for the construction of these buildings, they are

now estopped to raise objection thereto.

3. Except to the extent hereinabove specifically admitted,

the defendant School District denies each and every mate

rial allegation set forth and contained in the complaint of

the plaintiffs.

4. The defendant School District asserts that the plain

tiffs have failed to state a claim against this defendant

upon which the relief sought in Parts 1, 2 and 5 of the

prayer to the said complaint could be granted.

Wherefore, the defendant, Altheimer, Arkansas, School

District No. 22, prays:

1. That it be dismissed from this action with its costs

with all other legal and proper relief; and,

2, That so much of the plaintiffs’ complaint as seeks the

relief sought in Parts 1, 2 and 5 of the prayer thereto be

dismissed for failing to state a claim against this defend

ant upon which relief can be granted.

Answer of Altheimer School District No. 22

14

Separate Answer o f the

J. E. Stowers Construction Company

(Filed March 5, 1966)

For its separate answer to the Complaint, The J. E.

Stowers Construction Company states:

1.

That the jurisdictional allegations of paragraph I and

II of the Complaint require no answer, hut to the extent

that they imply that plaintiffs have been denied any con

stitutional rights by this defendant, they are denied.

2.

This defendant has no knowledge of the identity, citizen

ship, or capacity to represent others, of the plaintiffs, and

therefore the allegations of paragraph III are denied.

3.

The allegations of paragraph IV of the Complaint are

admitted except that the correct trade style of this defend

ant is J. E. Stowers, General Contractor.

4.

This defendant has no knowledge of the matters alleged

in paragraphs V, VI, IX and X of the Complaint, and

therefore denies those allegations.

5.

It is admitted that this defendant entered into a con

tract with the School District for the construction of two

elementary classroom buildings, and that construction of

15

Separate Answer of the

J. B. Stowers Construction Company

these buildings is now in progress. All other allegations

of paragraph YII and VIII of the Complaint are denied.

W h e r e f o r e , this defendant prays t h a t the cause of action

be dismissed as to it, that it have judgment for its costs

herein expended, and for such other or different relief as to

the Court may appear just.

16

(Filed March 10, 1966)

Come the plaintiffs and for their Answers to the Inter

rogatories served on them March 3, 1966, state:

1. State in what specific respects any school operated by

the defendant School District was “substantially in

ferior” to other schools operated by the District.

Answer: Historically the Negro elementary school sys

tem located in Altheimer, Arkansas, has been sub

stantially inferior to the white elementary school

located in Altheimer, Arkansas as follows:

(a) New school buses would be used to transport

white children, and the old buses that had been

used to transport white children would then be

used to transport Negro children.

(b) Prior to 1955, the Negro children had no hot

lunch program at all, and when it was inau

gurated in 1955 the old equipment that had

been used for the benefit of the white children,

who had had a hot lunch program for years was

installed in Negro schools for the benefit of

Negro children; while new equipment was in

stalled in the white school.

(c) Because of the consolidation of all Negro wing

schools by 1955, the Negro teachers had an ex

cessive pupil load (Here we are referring to the

entire student body because there was not a

sharp division between elementary and high

schools in that the principals were respnsible

for both the elementary and the high school)

Plaintiffs’ Answers to Interrogatories by Defendant

Altheimer School District No. 22

17

i.e., sometimes 19, 20, and never more than 21

Negro teachers to pupils with an enrollment of

1000 and with average daily attendance 890 to

900 during peak seasons; while 8 to 10 white

teachers taught pupils with a total enrollment

of around 375 with average daily attendance of

approximately 300.

(d) Prior to 1955 the Negro school had no rating

at all during which time the white school was

rated between “C” to “A”. At the present time,

according to our best information Negro school

has an “A” rating and the white school has a

“NCA” rating.

2. State in what specific particulars the construction of

new elementary school classrooms by the defendant

School District will perpetuate racial segregation.

Answer: The construction of new elementary school

classrooms by the defendant School District will not

within itself perpetuate racial segregation.

3. State in what specifics the defendant School District’s

plans for teacher desegregation should be modified to

comply with the relevant Case Law.

Answer: Plaintiffs do not have sufficient information to

say that defendant has any plan for desegregation of

teachers and cannot therefore say how the plan should

be modified. However, plaintiffs state on information

and belief that the present faculty and staff is segre

gated, and that defendant has no plans for reassign

ing teachers in such manner as to insure that white

Plaintiffs’ Answers to Interrogatories by Defendant

Altheimer School District No. 22

18

and Negro teachers will teach at each school in the

district during the school year 1966-67.

4. State whether or not any minor children of school age

residing within the District and in your care or cus

tody have been denied the access to any school in the

District.

Answer: Plaintiffs have insufficient knowledge or infor

mation to respond to interrogatory No. 4.

5. If you are the parent or guardian of minor children

of school age, state whether or not you were given

personal and direct notice by letter from the School

District brought to you by your child or children that

you would express a choice of the school to be attended

by your child or children during the 1965-66 school

year without restriction on the basis of race, color or

previous school attendance.

Answer: Plaintiff’s counsel are prepared to stipulate

that plaintiff’s received notice.

6. If you are the parent or guardian of a school age

child within the District, state whether or not you

were given the opportunity to express a choice of the

school to be attended by your child in the District in

writing or otherwise, and if so, whether or not you

exercised the option granted to you so to do.

Statement: Plaintiff’s counsel have not had an opportu

nity to canvass all of the plaintiffs in this regard but

shall do so as soon as time permits and will forward

their answer promptly.

Plaintiffs’ Answers to Interrogatories by Defendant

Altheimer School District No. 22

19

Prelim inary Pre-Trial Order

(Filed Mar. 8, 1966)

Gentlemen:

This suit in equity is now partially at issue and this

letter will serve the purpose of at least a preliminary pre

trial order; your prompt attention hereto will be appre

ciated.

1. The J. E. Stowers Construction Co. has not yet filed

any pleading in the case, but I assume that in general it

will take the same position as does the defendant school

district, that is to say, that the construction company will

deny that plaintiffs are entitled to any relief as far as the

construction of the two elementary schools are concerned.

Now, I notice that the Marshal’s return on the summons

issued for the construction company reflects that service

was had on J. E. Stowers who is described as the “owner”

of the construction company. If the construction company

is not a corporation, the suit should probably be against

Mr. Stowers doing business as The J. E. Stowers Con

struction Co. I do not know that this is too important,

but I am mentioning it.

2. On February 17 plaintiffs moved for a preliminary

injunction but have not sought to obtain a hearing on that

motion. On March 4 the school district filed its answer to

the complaint. Assuming without suggesting that plaintiffs

might be entitled to a preliminary injunction, I doubt that

they would be inclined to furnish the substantial security

which might be required as a condition to such an injunc

tion. I think that the practical way to approach the problem

is to hold a rather speedy trial on the merits, and I am

20

Preliminary Pre-Trial Order

wondering if counsel can be ready by the week of March 28,

1966. Please advise me in that connection.

3. The ease has a three-fold aspect: (a) Plaintiffs seek

to enjoin the construction of the two school buildings

referred to in the pleadings, (b) Plaintiffs attack the dis

trict’s “freedom of choice” plan of desegregation, (c) Plain

tiffs seek to bring an end to alleged racial discrimination

as to staff and faculty and to alleged discriminatory salary

schedules.

As to the buildings and as to the “freedom of choice”

plan, the defendants say that the complaint fails to state

a claim upon which relief can be granted. Without in

timating any viewT as to whether or to what extent, if any,

this Court has jurisdiction to enjoin public school con

struction on the theory which plaintiffs seem to advance,

the Court will consider the question on the merits, and will

consider that the district denies that the challenged con

struction was designed to perpetuate racial segregation

and denies that it will perpetuate invidious racial dis

crimination.

As to the freedom of choice plan, counsel on both sides

are aware that such plans have been approved by this

Court, by other federal courts in Arkansas, and by the

Court of Appeals for this Circuit. If the district’s plan

has been approved by the Office of Education, as the dis

trict says that it has, the Court doubts that it would be

disposed to depart from its previous rulings.

4. Counsel for the district is now directed to file forth

with a copy of its plan. The parties should be able to

stipulate as to whether the plan has been approved by the

Office of Education. If there is any dispute about that,

the district should be prepared to make proof.

21

Preliminary Pre-Trial Order

5. Counsel on both sides are directed to endeavor to

stipulate as to salary differentials, if any, between white

teachers and Negro teachers.

6. The Court observes that the district has propounded

interrogatories to adult plaintiffs. Answers will be due

about March 20, but it may be that plaintiffs can expedite

the answers. Any other discovery should be initiated and

prosecuted with diligence to completion.

Please acknowledge receipt of this letter; any comments

you may have to make hereon at this time will be welcome.

Very truly yours,

J. S m it h H e n l e y ,

J. Smith Henley,

United States District Judge.

22

(Filed Mar 22, 1966)

Now comes the defendant, The Altheimer, Arkansas

Public School District No. 22 of Jefferson Comity, and in

Answer to the plaintiffs’ request for admissions heretofore

on the 10th day of March, 1966, served in the above styled

cause states:

Request No. 1. The Court has jurisdiction over the

subject matter in controversy under Title 28 U.S.C.

§1343 (3) (4) and Title 42 U.S.C. §1983.

Response: This defendant admits the truth of request

for admission numbered 1.

Request No. 2. Plaintiffs are entitled to prosecute

this action on behalf of themselves and other members

of their class.

Response: The defendant admits that all of the plain

tiffs are proper parties plaintiff with the exception of

the plaintiff, Floyd Thomas, who is not a resident of

the defendant school district. This defendant admits

that the plaintiffs are proper parties to bring’ this

action on behalf of themselves and other members of

their class with the exception noted.

Request No. 3. Presently, the schools attended solely

by Negro pupils are rated (A) or below by the State

Department of Education.

Response: This defendant admits that the schools at

tended solely by Negro pupils and operated by it are

rated “A” by the State Department of Education.

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions

Request No. 4. Presently, the schools attended pre

dominantly by white pupils are rated by the North

Central Association of Schools and Colleges.

Response: This defendant admits that the High School

attended predominantly by white pupils is rated by the

North Central Association of Secondary Schools and

Colleges, but this Association does not rate elementary

schools. Altheimer High School was accredited by the

North Central Association of Secondary Schools and

Colleges in 1964. Martin High School is in the second

year of an accreditation study, and this defendant

believes and expects that it will be accredited by this

Association when the new school buildings which are

in dispute in this action are completed.

Request No. 5. North Central Association rating of

a school indicates superior facilities, programs, equip

ment, etc. to those of schools rated (A) or below by

the Arkansas State Department of Education.

Response: This defendant admits that as a general

rule accreditation of a high school by the North Cen

tral Association of Secondary Schools and Colleges

indicates the school possesses facilities, programs,

equipment, faculties, etc. which are superior to those

of schools rated “A” or below by the Arkansas State

Department of Education. However, this defendant

believes that there are numerous schools in the State

of Arkansas which have been accredited by this Asso

ciation which possess facilities, programs, equipment,

faculty and other school attributes of a quality gener

ally lower than that possessed by the Martin High

School.

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions

24

Request No. 6. Requiring or permitting pupils to at

tend the present all Negro school means that pupils

assigned thereto will he deprived of equal protection

of the laws.

Response: This defendant denies request for admis

sion numbered 6.

Request No. 7. Taking into account the current en

rollment in the predominantly white schools, the pres

ent school facilities now being used primarily by white

pupils are inadequate to accommodate several hundred

additional Negro pupils.

Response: This defendant admits that the predomi

nantly white schools operated by this District are in

adequate to accommodate several hundred additional

students of any race.

Request No. 8. Taking into account the present school

facilities, and removing the factor of race, “freedom

of choice” is an administratively impractical approach

to making school assignments in defendant district.

Response: In response to request for admission num

bered 8, this defendant admits that “freedom of choice”

is not in some circumstances an ideal administrative

approach to school assignments, but it is not “im

practical”.

Request No. 9. Defendant district plans the proposed

new facilities as replacements for the present elemen

tary school facilities.

Response: In response to request for admission num

bered 9, this defendant admits that to some extent the

proposed new buildings are to replace the existing ele

mentary school rooms, but they are also to provide

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions

25

additional space for additional programs planned by

the District and to accommodate increases in enroll

ment.

Request No. 10. The replacement facility for the Mar

tin (Negro) School will consist of approximately

eighteen (18) classrooms.

Response: This defendant denies request for admis

sion numbered 10 and states that the new construction

at the Martin School site will consist of sixteen class

rooms.

Request No. 11. The replacement facility for the

Altheimer (predominantly white) School will consist

of six (6) classrooms.

Response: This defendant denies request for admis

sion numbered 11, but states that the new construction

at the Altheimer School site will consist of eight class

rooms and related facilities.

Request No. 12. Under defendant’s “freedom of

choice” desegregation plan, less than twenty-five (25)

Negro pupils of approximately nine hundred (900) in

defendant district chose to attend the formerly all-

white schools.

Response: This defendant admits request for admis

sion numbered 12.

Request No. 13. Defendant district has not formulated

specific plans to reassign teachers on a basis which will

insure, during the 1966-67 school term, integrated fa

cilities at all the schools operated by the district.

Response: To the extent that request for admission

numbered 13 implies that the defendant School Dis

trict has purposefully formulated specific plans to re-

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions

26

assign teachers on the basis of their race so as to be

teaching in schools which may consist predominantly

of students of another race on a broad scale the re

quest for admission is admitted. As indicated in the

response of this defendant to the interrogatories pro

pounded to it, plans have been made for the use of

white teachers in the predominantly Negro schools

and Negro teachers in predominantly white classes.

Request No. 14. Defendant district has a dual salary

schedule whereby Negro teachers are paid, on the aver

age, lower salaries than white teachers.

Response: This defendant does not feel that it can

honestly respond to request for admission numbered

14 for the reason that average salaries do not provide

a suitable guide or standard in determining whether

disparities in salaries between teachers exist solely on

the basis of the race of the teacher. To the extent that

the request for admission numbered 14 would im p ly

that there is a disparity in salaries paid to Negro

teachers solely because of their race, it is denied. There

are numerous Negro teachers whose salaries exceed

those of numerous white teachers, and, in turn, there

are numerous white teachers whose salaries exceed

those of numerous Negro teachers. In each instance,

the disparities in salaries between and within each

race are based upon the qualifications of the Negro

teachers without regard to their race.

T h e A l t h e im e b , A rkansas P u b l ic S chool

D ist r ic t N o . 22 of J effe r so n C o u n ty

B y / s / J am es B. W a lk er

Superintendent

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Request for Admissions

27

(Filed Mar. 22, 1966)

Comes the defendant, The Altheimer, Arkansas Public

School District No. 22 of Jefferson County, by its Super

intendent, James B. Walker, who, having been duly sworn,

in response to the interrogatories served upon this defen

dant in the above styled cause makes the following answers

and responses thereto:

Interrogatory No. 1. State whether the defendants

have entered into contract whereby defendant J. E.

Stowers, doing business as the J. E. Stowers Con

struction Company, will construct two elementary

schools for defendant district. Also, attach a copy

of such contract to your response to this interrogatory

along with a copy, blueprint or other document which

sets forth the details of the planned school construc

tion.

Answer: This defendant has contracted with the de

fendant, J. E. Stowers doing business as The J. E.

Stowers Construction Company, for the construction

of two school buildings for the defendant District.

A copy of the blueprints reflecting the size, style and

type of construction of these buildings is attached

with the copy of these answers which will be served

upon Mr. John W. Walker, as one of the plaintiffs’

attorneys. Because of the size and expense of duplica

tion, this defendant desires to avoid further repetition

of service of this document.

Interrogatory No. 2. State for each school—sepa

rated into high school and elementary school divisions

—now operated by defendant district the following:

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

28

a. the number of pupils by race

b. the number of teachers by race

c. the pupil-teacher ratio

d. the average daily attendance

e. the number of pupils who are “bussed” to and

from school

f. the per capita expenditure on each pupil

g. the number of overcrowded classrooms

Answer: The response of this defendant to Inter

rogatory No. 2 is submitted in tabular form as follows:

M aktix S chools

Elementary High School

a. Negro 541 Negro 454

b. Negro 19 White 1 Negro 18 White 2

c. 1 to 27 1 to 25

d. 492 411

e. 335 305

f. The average per pupil expenditure at all schools

operated by the defendant District is $240.00 per

pupil based upon average daily attendance. The

District does not attempt to maintain accurate

records of average expenditures divided by schools.

g. 5 2

This overcrowding is based upon average daily

attendance at the end of the six months of the

1965-1966 school year and uses a classroom total

of 35 as the maximum acceptable student load per

classroom.

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

29

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

A l t h e im e r S chools

Elementary High School

a. Negro 2 White 198 Negro 4 White 209

b. White 8 White 12

c. 1 to 25 1 to 18

d. 184 210

e. 120 140

f. The average per pupil expenditure at all schools

operated by the defendant District is $240.00 per

pupil based upon average daily attendance. The

District does not attempt to maintain accurate

records of average expenditures divided by schools.

g. 4 6

This overcrowding is based upon average daily

attendance at the end of the six months of the

1965-1966 school year and uses a classroom total

of 35 as the maximum acceptable student load per

classroom.

Interrogatory No. 3. Set out for each high school a

listing of the available course offerings.

Answer: The following courses of instruction are

open to students of both schools in the grades indi

cated :

Seventh Grade

English, Arithmetic, Science, Geography, Physical

Education, Reading Clinic or Remedial English.

Eighth Grade

English, Arithmetic, Science, History, Physical Edu

cation, Reading Clinic or Remedial English.

30

Ninth Grade

English-Literature, Algebra 1, Civics-Arkansas His

tory, Home Economics, Vocational Agriculture, Physi

cal Education, Reading Clinic or Remedial English.

Tenth Grade

English-Literature, Geometry, General Math, Biology,

Home Economics, Vocational Agriculture, Reading

Clinic or Remedial English, Physical Education.

Eleventh Grade

English-Literature, Algebra 2, Business Math, Chem

istry, Home Economics, American History, Vocational

Agriculture, Physical Education, Reading Clinic or

Remedial English.

Twelfth Grade

English-Literature, Senior Math, Bookkeeping, Short

hand, Office Practice, Problems of Democracy, Reading

Clinic or Remedial English, Physical Education.

Physiology is offered primarily as an Eleventh Grade

subject to students at Martin School but is not available

at Altheimer High School. Martin schools have three years

of General Science while Altheimer has only two years of

General Science and offers two years of Biology instead

of the one year of Biology offered at the Martin schools.

Physical Geography is offered at Martin schools but is not

offered in Altheimer school. French is available as an

elective in the Altheimer school but not in the Martin

school. Four years of Home Economics and Vocational

Agriculture are offered to students of Martin school and

only three years of these subjects are available to students

at Altheimer school.

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

31

Interrogatory No. 4. Set out for each high school the

available extracurricular activities.

Answer: The following extracurricular activities are

available at Martin schools:

Inter-school Basketball, Baseball, Track, Tumbling,

Intra-school Volleyball, Softball, Table Tennis, Horse

shoes, Shuffleboard, Badminton, Kiekball, Touch Foot

ball and Basketball.

The following clubs are active at Martin School:

Future Farmers of America, Future Homemakers of

America, The Student Council, National Honor So

ciety, Library Club, Science Club, Math Club, Choir,

Camera Club, Commercial Club, School Newspaper,

“M” Club (for athletes), 4-H.

The following extracurricular activities are available

at Altheimer High School:

Future Farmers of America, Future Homemakers of

America, Library Club, French Club, Student Council,

Annual Staff, School Newspaper, Inter-school Basket

ball and Baseball, Intra-school athletics similar to those

at Martin School except that there is no equipment

for tumbling at Altheimer School.

Interrogatory No. 5. Set forth the number of parents

and/or pupils who failed to exercise any choice what

ever, on forms provided by the district prior to the

beginning of the 1965-66 school term.

Answer: Every student in school or known to be a

prospective student for the 1965 fall term was pro-

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

32

vided a School Choice Form for their parents and

they were instructed that it was necessary for their

parents to execute this on behalf of their child and

return it to the school during the spring pre-registra

tion in 1965. Every student then in school or known

to be a prospective student for the 1965 fall term had

such a School Choice Form executed for him or her.

There are some students who have transferred into

the District since that time for whom no School Choice

Forms were executed. Their exact number is not

known and could not be obtained without great ex

pense and difficulty. Among these are the minor chil

dren of the plaintiff, Moses Kelley, who were enrolled

on August 30, 1965, at the school to which they

presented themselves and indicated was their choice

for attendance.

Interrogatory No. 6. State the criteria by which

pupils who failed to make a school choice on forms

provided by the district were assigned.

Answer: It was the uniform policy of the District

and all school principals were so instructed that no

child would be enrolled for whom a School Choice

Form had not been prepared. It now appears to the

District that a small number of pupils were registered

in one or more of the schools of the District when

they presented themselves at a particular school for

enrollment.

Interrogatory No. 7. State how the district’s school

construction program will eliminate the pre-existing

dual school structure.

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

33

Ansiver: The present construction program of the

District is not intended, one way or the other, to have

any bearing on the racial constituency of the schools

involved. The construction of the buildings indicated

is solely motivated by the District’s desire to provide

the necessary classrooms to meet increased program

and pupil loads and to utilize, as fully as possible, the

necessary supporting facilities which are presently

available such as cafeterias, offices and gymnasiums.

Interrogatory No. 8. Set out in detail the district’s

plans for faculty desegregation next fall if those plans

are different from the plan submitted to the United

States Office of Education in 1965. Also, attach a copy

of such desegregation plan to your response to this

interrogatory.

Answer: No formal amendments have been made to

the plan for desegregation of the schools operated

by this District as previously submitted to the Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare. However,

in addition to continuing the desegregated programs

referred to in the plan of the District as heretofore

filed, the District now plans to fully integrate its pro

gram of Vocational Agriculture and two instructors,

one a Negro and the other white, will each teach mixed

classes in that subject at a common location.

Interrogatory No. 9. State whether the district has

applied for and received school funds under Title 1

of Public Law 89-10. If so, attach a copy of such plan

to your response to this interrogatory.

Answer: The District has applied for and has received

school funds under Title 1 of Public Law 89-10. and

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

34

a copy of the plan for utilization of such funds and a

request therefor is hereto attached.

[Attachment omitted]

Interrogatory No. 10. Set out copies of the notice

given, the dates of same, the mode of publication, and

the plans presented to the public prior to the bond

election held on September 28, 1965. If copies of the

information herein sought are unavailable, set out

fully in narrative form the requested information.

Answer: The plan to construct elementary school

additions to both the Martin school plant and the

Altheimer school plant was discussed in P.T.A. Meet

ings in both schools on at least one occasion prior to

the school election on September 28, 1965. During

the month of September, 1965, a mimeographed notice

was sent with each school child to the parents urging

them to vote in the school election. The required

legal notices of the election, indicating the increased

millage sought and the general purposes therefor,

were published in the Pine Bluff Commercial as re

quired by law and copies of the same together with

the proof of publication thereof are hereto attached.

There was wide discussion and general knowledge of

the plan prior to the school election on September 28,

1965. The Pine Bluff Commercial, which is the news

paper having general circulation in this area, carried

stories of the plans for construction of these two

elementary school buildings in the July 22nd edition

on the front page, in the September 26, 1965, edition

in a story beginning on page 1 and continued on

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

35

page 2, in a story on page 3 of that paper on Sep

tember 27, in a story on September 29 on the front

page indicating the results of the school election and

referring to an additional article on page 29 of that

edition in which details of the school plans were set

forth. In addition, on page 15 of the October 29th

edition of the Pine Bluff Commercial an article in

dicating the sale of bonds by the District was men

tioned referring to the school construction and on

February 11, 1966, in an article appearing on page 6

there was a story indicating that contracts had been

award to the lowest bidder for the construction of the

two buildings in question.

[Attachment omitted]

T h e A l t h e im e r , A rkansas P ublic S chool

D istrict No. 22 oe J efferson County

By , / s / J ames B. W alker

Superintendent

Defendant Altheimer School District No. 22’s

Response to Plaintiffs’ Interrogatories

36

A ppearan ces :

Hon. J o h n W alker ,

1304 B Wright Avenue,

Little Bock, Arkansas

H on . H erschel H. F riday, of

S m it h , W illia m s , F riday & B ow en ,

Boyle Building,

Little Rock, Arkansas

H o n . E. H arley C ox, of

C olem an , B amsay, Gantt & Cox,

Simmons National Bank Building,

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

The deposition of the witness in the entitled and num

bered cause, was taken before me, Jacqueline J. LaBat,

Notary Public, in and for Pulaski County, Arkansas, in

the building of the Altheimer High School, Altheimer,

Arkansas, beginning at the hour of 10:50 a.m., Saturday,

April 30, 1966, on behalf of the plaintiffs in the styled

cause, in accordance with the Federal Rules of Civil pro

cedure.

T h e r e u po n , th e fo llow ing p ro ceed in g s w ere h ad , to -w it :

S t i p u l a t i o n

It is stipulated and agreed by and between counsel for the

respective parties that the deposition of the witness may

be taken at this time and place, by agreement of counsel;

that all formalities as to the taking of said deposition is

waived, including presentation, reading and subscription

by the witness, notice of filing, etc., that all objections as

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

37

to relevancy, materiality and competency are expressly

reserved and may be raised if and when said deposition,

or any part thereof, is offered at the trial of the cause,

and pursuant to the authority of the Court to introduce the

testimony of additional witness on behalf of the plaintiffs

which would be considered in connection with other evi

dence submitted at the trial of the issues in this cause in

the presence of the Court.

Further stipulation that the defendants reserve the right

to introduce rebuttal evidence at a later time, and it is

further stipulated that the plaintiffs may give testimony

subject to any later objections.

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Tahen at Instance of Plaintiffs

Dr. M yrow L iebermaw , called as a witness, after being

duly sworn first by the undersigned Notary Public, in an

swer to questions propounded, made the following state

ments, to-wit:

Direct Examination by Mr. Walker:

Q. Would you state your name, your address and your

occupation, please ? A. My name is Dr. Myron Lieberman.

My address is 271 Doyle Avenue, Providence, Rhode Is

land, 02906. My occupation is Director of Education Re

search and Development at Rhode Island College and Pro

fessor of Education at Rhode Island College in Providence,

Rhode Island.

Q. Dr. Lieberman, where did you do your educational

work? A. Are you speaking of my preparation?

Q. Yes, sir. A. I have a Bachelor’s degree in law and

social science from the University of Minnesota and a

Master’s and Ph.D. degree from the University of Illinois.

Q. Would you tell us what your major field of studies

was at the University of Illinois? A. Well, my major

field of study at the University of Illinois was education.

My doctor was in field of philosophy and in the field of ed

ucation. Most of my work was in that aspect of education,

which is now called the Social Foundation of Education,

which as the subject matter is an analysis and with factors

like race and religion and the tax structure and other cul

tural and social factors that affect public education.

Q. Would you tell us what educational programs were

included in your field of study, like courses and the like?

A. Well, the courses that were included were courses en

titled Social Foundation, courses relating to theories of

instruction, courses dealing with the role of pressure

groups that affect-—that affect education, courses relating

to personnel, and structure of education, courses relating

to the tax structure and its affect on schools. In other

words, by and large the course structure dealt with the

major factors in shape and forms of public education.

Q. Have you ever taught in your field of study? A. Yes,

I have been teaching in this area which, as I say, included,

for example, in fact race and religion and education, and

in education since receiving my doctoral degree at the

University of Illinois. As a matter of fact, I was teaching

in this area even while I was working for my doctoral de

gree, so the past twelve years this has been one of the

major—my major, or professional, areas.

Q. Now, would you describe the responsibilities that you

have at Rhode Island College? A. Well, of course, I do

have—I do have some teaching responsibilities. My posi

tion as Director of Educational Research and Development

requires me to work with the faculty of the entire college

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

39

in the preparation and submission of research and develop

ment proposals affecting the college. For example, if a

faculty member wishes the college to hold an NDEA insti

tute or if he wishes to conduct a research program which

requires assistance either from public, city or private foun

dations, then he would come to me and I would help him

locate sources of donations and I would help him draft the

proposal. I might help him find experts in this field who

would work with him on it. In other words, this is a staff

position which is designed to help other people in the col

lege pursue research and development interests.

Q. I see. Would you name some of the professional or

ganizations in your field in which you hold membership!

A. Well, I belong—I’m a life member of the National Ed

ucational Association. I belong to the state—the State

Educational Association, the American Educational Re

search Association, the Philosophy of Education Society,

and the American Association, Association of Colleges for

teacher education, American Association and the American

Association for the Advancement of Science. These are

some of the major professional associations, organizations,

to which I belong.

Q. Have you ever written articles for any professional

organization in your field of study! A. Well, I ’ve writ

ten—Yes, I ’ve written about, I would guess—-Oh, I don’t

know, well over fifty articles on various aspects of educa

tion. They’re not all—not all of them are of course in

volved race relations or kinds of problems that we’re deal

ing with here. Some of them do. I ’ve also authored two

books. I am the coauthor of another which is coming out

in July on School Personnel Administration, and then have

attributed to, or co-author of three other books, all of

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

40

which have some bearing upon the subject matter of this

proceedings.

Q. Have you ever served in an editorial position for the

journal of any of those organizations? A. Well, I was at

one time editorial consultant for the Nation Magazine.

This is not a professional magazine. I t’s a magazine for

general cultural and intellectual interests, although I was

the education consultant. I ’ve also served as a special edi

tor of an issue of some professional journals. For exam

ple, education. I ’m currently serving as the editor of a

special issue of the Phi Delta Kappan which is the honorary

fraternity in the field of education.

Q. I see. Now, Dr. Lieberman, are you familiar with

the contract between the Altheimer School District and the

J. E. Stowers Construction Company? A. Well, I would

say that I ’m familiar with it. It would mean would I un

derstand to be the main—main objective, the main purpose

of the contract.

Q. I see. And are you familiar with the proposed build

ing plans of the Altheimer School District? A. Well, as

I—as I understand the main element, and I couldn’t—For

example, there are many details concerning this construc

tion plan that I am not familiar with, but as I understand

the heart of the construction proposal, it is to construct

sixteen elementary classrooms in what is now called the

Martin School Complex, or the Martin—Martin Schools, and

eight elementary school—there are eight classrooms in the

Altheimer plans.

Q. I see. Are you familiar with—Have you had an op

portunity to view the facilities of both complexes? A.

Yes. I visited—I spent—I spent a day, I believe it was

Friday, April 1st, and visited both complexes and talked

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

41

to Superintendent Walker and to Mr. Martin and to a

number of other teachers and administrators in the school

district.

(At this time there is a discussion between counsel and

the deposition is resumed.)

Q. Dr. Lieberman, I show you a copy of the per capita

cost for each pupil in the Altheimer schools as certified by

the Altheimer School District certified public accountant

and ask you whether you are familiar with that. A. Yes,

I am. I have seen this—this statement.

Q. I also show you, Dr. Lieberman, a copy of the data

concerning the cost of local school districts, plaintiff’s ex

hibit one, which sets out teachers’ salaries for the school

district and ask you if you are familiar with it. A. Yes, I

have seen this.

Q. I also show you plaintiff’s exhibit four which is a dis

tribution of expenditure and per pupil cost of the Altheimer

School District for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1965,

and ask you if you are familiar with it. A. Yes, I have—

I have looked at this statement.

Q. Now, Dr. Lieberman, would you tell us what your

understanding of the facilities of the Altheimer District

are, generally speaking? A. Well, basically, as I under

stand the system as it operates now, there is a—there are

two—two school complexes, each are from grades one

through twelve. One of these is labeled the Altheimer

Complex, or Altheimer Schools, and the other complex is

Martin Schools. Each complex runs from grades one

through twelve. The Martin schools enroll negro pupils,

the Altheimer schools enroll approximately four hundred

white pupils and six or seven negro pupils.

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

42

Q. I see. Are you familiar with the physical facilities of

the two school complexes? A. Well, I visited—yes, I—I

visited, I spent one day in visiting and discussing the

physical facilities. Of course, I spent more time in some

than I did in others and I am more familiar with some

aspects and facilities than I am of others, but I developed—

what I would regard as a fairly clear picture of the physical

setup of the school districts.

Q. All right. Have you had an opportunity to study

the exhibits in front of you and make any conclusions about

the comparitive adequacies of the two school complexes?

A. Well, it—it is obvious, from an analysis, not only of

the—the figures that are included in these exhibits, but

from an analysis of the system itself, that there is an

appalling discrepancy of any equality in the per pupil

cost per white and negro pupils in the school system. It is

true, for instance, that there are certain elements in these

figures that cannot be assessed precisely down to the last

penny, but these particular points where it is impossible

to fix a precise amount do not in any way, shape or manner

invalidate the conclusion that the school district, that there

is as I said earlier, a really appalling differential in the

expenditures for negro than there is for white pupils.

Q. Now, Dr. Lieberman, would you look at the exhibits—

A. Yes.

Q. —and be more specific? A. Well, take, for instance,

the situation at the secondary school level. Now, the—the

average, the teacher-pupil ratio in the secondary school

levels, as I recall, is twenty five to one, at the Martin school,

and eighteen to one at the Altheimer secondary school,

and this is—in other words, the teachers at the Altheimer

school—teachers at the Martin school, secondary school,

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieherman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

43

carried what amounted to a 33% heavier per pupil load

on the average than they did at the Altheimer school.

Now, teachers’ salaries generally run to anywhere from

sixty to eighty percent of the total cost of operating the

school system as they do with the figures here which seem

to be in that range, so obviously if the school system is

spending, if the system is spending a great deal more for

teachers for one group of pupils than for another, this is

of course a very important inequality.

In addition to the fact, and of course I want to emphasize

I am only telling about one aspect of the figures, and in

addition to the fact there is this very heavy differential in

the teacher-pupil ratio. The teachers in the Martin Com

plex are, with very few exceptions, paid less than the

teachers in the Altheimer Complex. When you add that,

when you add to the difference in class teacher-pupil ratio

the difference in the salaries that are paid and then you add

the fact that the physical facilities in Altheimer complex

on the whole are superior to those in the—in the Martin

complex, you can then understand that even though there

may be some controversy over details, there is a—there is

an enormous difference. I believe the—I would estimate

that, and I think the figures bear this out, that the school

system is spending a certain secondary level twice as much

for instructional cost for white pupil than it is for negro

pupil.

Q. All right. Are there any other things that—any other

items set forth here in the documents before you which

cause you to conclude that negro pupils, or pupils at the

Martin school, are not being given equal treatment as the

pupils at the—with pupils at the Altheimer school? A.

Well, the things that I examined and studied, I would say

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Liebermcm,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

44

it would be difficult to find one aspect—Well, let me change

that. They are, on the whole, I would say, that the students

at the Martin school are attending school under a serious

disadvantage. The things that I mention, like teacher-pupil

ratio and the physical facilities are important, but to go

on, for example, the gymnasium facilities seem to be far

superior at the Altheimer school than they are at the

Martin school. There’s a much better auditorium. There

are much better facilities for the spectators, it is a bigger

installation, the library facilities. There’s a serious dis

crepancy—serious in equality in the library facilities. For

example, when I visited the library at the Martin—Martin

school the library was very crowded. There is no separate

study area. The study area was completely in the same

area that is surrounded by books.

Now, most experts in school libraries advocate that there

be a study area that is separated—separate from the

library reading area. Now, there is such an area available

at the Altheimer complex next to the library, but at the

Martin schools this is not available. So that these are—

these are some of the items that would lead me to—I mean

lead me to the. conclusion that there is really a specific in

equality of educational opportunity in the two complexes.

Q. Do you have an opinion as to the educational signifi

cance of the type of teacher per pupil expenditures in the

two schools'? A. Well, few—yes. For instance, just take

a matter of necessity for improving construction in the field

of English instruction. Now, there are—May I refer here

to—

Q. Certainly. A. If I may refer here, for example, to

what is probably the most important study of secondary

education that has been made in this country. The study of

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

45

the American High School, by Dr. James Bryant Conant,

and then a discussion of English instruction. He says for

the best instructions themes all should be corrected by the

regular teacher who in turn shall discuss them with the

students. Obviously, an adequate instruction in English

composition requires the teachers not be overloaded.

Well now, if you have one teacher who is, let’s say,

dealing with twenty five or thirty students and you have

another teacher who is dealing with fifteen or twenty, this

is a tremendous overload in dealing with the students as

an individual. One teacher had many more themes to

read, she would have many more pupils to talk to and as

a result of this, she would have less time for each individual

pupil. Now, again, I ’m only referring to this as an example

to run through the entire instruction on the program. If

there is a serious discrepancy as there is here in the aver

age, in the teacher-pupil ratio, that means that each teacher

to the extent that this is true, has less time to devote to

the individual student to discuss with him what his diffi

culties are and help him as an individual. There is no

doubt that this runs all the way through the educational

program.

Q. Do you have an opinion as to whether white pupils

in the—in Altheimer are getting good education for the

investments that the school is giving? A. Well, I—I very

definitely feel that the white pupils in the Altheimer

School System are being drastically shortchanged in the

education that is being offered to them. Let me illustrate

this.

Again, it’s only one illustration of many that could be

provided. Here the school system is operating two libraries

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Tahen at Instance of Plaintiffs

46

one through twelve grades five blocks apart. Now, what

books are going to go in each library? Are you going—The

system either has to buy duplicate copies of the same book

if it would just provide the books that are needed. Every

time you buy duplicate copies of a book where one will do

this means that you have less money to buy additional

books that would be useful to students who might need the

additional book.

Take the matter of personnel. It would be very helpful,

for example, if the elementary student had an elementary

librarian. It would be very helpful if secondary students

had a librarian who was a specialist in the needs of the

secondary pupils. Now, most schools of education, for

example, provide courses in children’s literature. One rea

son being that this is—this is a field that is in itself. On

the other hand, if you have two libraries each of which

covers grades one through twelve, you have a librarian at

each one, what then is the situation? If the librarian there

is an elementary librarian then the secondary pupils suffer

because the librarian isn’t adequate for that purpose. If

the librarian is a secondary for the secondary program the

elementary children suffer because it could have been a

librarian who is a specialist in children’s literature.

Now, as you look at the range of subjects that are offered

and the range of extra-curricular activities, first of all

there is a very considerable amount of duplication in both

the subjects and in the activities. Then there are some sub

jects and facilities that are offered at one complex but not

at the other. For example, just to cite this in terms of

some of the extra-curricular activities, as I understand from

the board’s interrogatories that were answered by the

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

47

board, there is no—there is no National Honor Society at

the Altheimer complex.

Q. Did yon say the Altheimer complex? A. That’s right.

Q. You mean the Martin complex? A. Well, we can

check the interrogatories. On page three of the interroga

tories it says “the following clubs are active at the Martin

school”, in the second line, that is National Honor Society.

Now, I don’t see any National Honor Society in the

Altheimer school. Now—

Q. Go ahead. A. Any—Again, it is just an illustration

that any—any high school, any school board would want to

otter this kind of thing and make it available for its stu

dents so let me—let me emphasize it in this way: In the

Study of the American High School” Dr. Conant made

the following comment: For example, on page thirty seven

this is headed: “Elimination of the small high school top

priority.” And he goes on to say on page thirty seven “I

am convinced small high schools can be statisfactory only

that are—absorb its expense” and he goes on to explain

why this is the case to provide adequate teachers for spe

cialized subjects. It is extremely expensive to maintain an

interest in academic subjects among a small number, it

is not always easy. While academic programs are not

likely to be offered when the academically ones in a school

are so few in number, the situation in regards to non-

academic elective programs in a small high school is even

•worse.

The capital outlay for equipment as well as the salary

of the special vocational instructors adds up to such a

large figure in terms of the few enrolled as to make the

educational programs prohibitively expensive in schools

Deposition of the Witness, Dr. Myron Lieberman,

Taken at Instance of Plaintiffs

48

when the graduating classes have less than one hundred.”

Then he goes on to say that “I should like to record this

in italics, 1 should like to record at this point my conviction

that in many states the number would—one problem is the

elimination of the small high school by district reorganiza

tion.”

Now, in other words, he is assuming in writing that no

school district that was capable in itself of eliminating a

small high school would not do so. It never occurred to him

in writing this that you would maintain two high schools—

two high schools, which even combined, were less than the

number needed to operate a high school efficiently from an

educational standpoint, even if you combined them. I be

lieve that the—the combined numbers would probably bring

the—it would be just at the margin of the minimum number

that you need, and I think it would be less than the mini

mum that you need to operate a secondary school efficiently

but in this particular case the school board presented with

an opportunity to at least reduce this almost incredible