LDF Article on Westinghouse

Press Release

January 1, 1980 - January 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. LDF Article on Westinghouse, 1980. 6cc05605-ef92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/215e8a6c-e1c8-4664-aa96-3f1e4c42a176/ldf-article-on-westinghouse. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

Willie Foster

"They can show you a hundred thousand differ-

ent ways where you don't want the job or you

can't do the job. They can't show you one way

where you can."

Willie Foster, like Walter Culbreath, was the would-

be victim of a technique geared to make blacks fail

when they accepted new, better work at Westing-

house. Like Mr. Culbreath, Mr. Foster's own intelli-

gence and talents saw him through the difficult time

when he was given the job of coil winder, and then

left to sink or swim on his own, without the training

or help normally given by fellow employees.

"I have been working for Westinghouse since March

16, 1959. One of the reasons that I'm here (at a meet-

ing of the Neighborhood Advisory Council) is be-

cause during the past twenty years that I worked

there I have seen a lot of discrimination in jobs and

wages. They give the jobs to certain peoples. And

some of these jobs you apply for, you got too much

education, or you don't have enough education.

And some they just don't want you to have. The

foreman may dislike you and give you a runaround.

They can show you a hundred thousand different

ways where you don't want the job or you can't do

the job. They can't show you one way where you

can. And in my opinion, right up to this day, this

situation still exists and I would like to see it

stopped. That's my reason for being here.

"I started out as a sweeper, which was the only

way a black man could get a job in the plant at that

time. Well, I'm a coil winder, a class 7 coil winder at

the present, but when I started working there, I

couldn't wind no coil. I didn't never have no train-

ing, but I had worked in the section and I knew

enough about winding coils that I was able to make

it. When I went to coil winding, the man came and

showed me how to turn the machine on. He turned

the machine on and walked off, and I ain't seen him

since. I didn't have any training."

You have read just a few of many statements made

at a recent meeting of the Neighborhood Advisory

Council. For 40 years, LDF has been helping people

like these in legal struggles to affirm, establish and

advance civil rights.

LDF has won many major victories to secure

equal educational opportunities, voting rights, fair

housing and equal employment opportunity. The

case in Athens, Georgia, is one of many in which we

are presently involved, not just in the South, but in

any part of the nation where blacks are oppressed by

racial discrimination.

Only the support of concerned men and women

across the country makes LDF's extensive court

battles possible. Please join us in this important

work, work which affects the lives and well-being of

so many, by sending LDF as generous a contribu-

tion as you can today.

When victims of discrimination

turn to LDF for help, LDF

turns to you.

Please send your tax-deductible gift to:

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

P.O. Box No. 13,064

New York, N.Y. 10049

(Office address: l0 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030,

New York, N.Y. 10019)

JANUARY I98O

Supported by voluntary contributions, THE NAACP LEGAL

DEFENSE FUND selects only those job-bias cases which can im-

prove the lot ofsubstantial numbers of black workers. It is hoped

that these key cases, numbering in the hundreds, can serve as the

fulcrum on which wages and working conditions are raised for

black workers generally.

In settling l8 cases between October of I978 and July of 1979,

LDF secured more than $5,000,000 in back pay for thousands of

black workers. Such settlements encourage revised personnel

practices throughout industry and thus move black workers a step

closer to parity with white workers. Fair employment policies are,

however, still far off as the decade of the 1980s opens.

"My niece was told that she had a job as

a Westinghouse secretary. But when she\

went to Westinghouse and they fourid

out she was black, they told her they had

filled the job."

Robert Gilham,

West inghouse emp lo ree,

Athens, Georgia

,

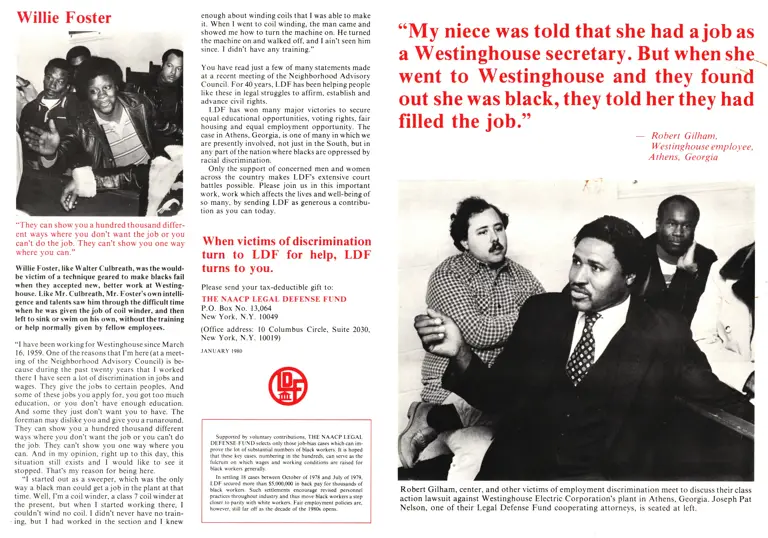

Robert Gilham, center, and other victims of employment discrimination meet to discuss their class

action lawsuit against Westinghouse Electric Corporation's plant in Athens, Georgia. Joseph Pat

Nelson, one of their Legal Defense Fund cooperating attorneys, is seated at left.

Racial Discrimination at Westinghouse

In 1958 x'hen the huge Westinghouse plant opened in Athens, Georgia, onl.t'.janitorial .jobs v'ere

oyailable to blocks. While some intprovements have been mode sinc'e that time, emplo_t'ment dis-

t'rintination remains an e-\trentel.t' serious problem .for blacks u'orking or seeking .jobs there.

The Legal Defense Fund and LDF cooperating attorneys Joseph Pat Nelson, David Russell

Sweat, and Kenneth Dious are in the midst of a massive class action lawsuit against the Westing-

house Electric Corporation's plant in Athens, Georgia. The plant produces overhead electrical

transformers - those big cylindrical objects at the top of every third or fourth telephone pole.

Westinghouse is charged with widespread and long-standing discrimination against blacks in hiring,

firing, testing, training, job assignment, promotion, and discipline. Here are the stories of some of

those who have suffered because of that discrimination.

highest ranking black employees at the plant, but he

will not be satisfied until all blacks are treated

equally by Westinghouse. He is vice-president of

the Neighborhood Advisory Council, an organiza-

tion of members of the class suing Westinghouse.

"l started working at Westinghouse April 21, 1958

as a sweeper. I worked in the maintenance depart-

ment and I was cleaning rest rooms for 7 months. In

November 1958, I went to the coil winding depart-

ment and held the job of storeroom attendant.

"Everything went fine until I applied for a job as

coil winder in 1961. All our winders were white men,

and everybody was angry at me. I had to go to the

employment office and take another test. I done

good on that test, and the supervisor told me that I

had passed all the qualifications for becoming a coil

winder. So I got this job and no one would help me

do anything. I had to do it all on my own. That was

a rough job because you didn't have anyone to ex-

plain anything to you. If it was something you didn't

know, you had to try and figure it out for yourself.

"Then the trouble started. I would take a break

and if I was running high voltage wire, which was

running at a fast speed, I'd come back and some-

body would have put the machine in reverse. At that

time I was winding six coils, and when this thing

goes backwards, all this wire unravels, and I had to

straighten out all that mess.

"They would also take a pair of needlenose pliers

and crimp the high voltage wires just enough so that

when I put tension on it, it would break. And some-

times they put goo on my stooland all over my tools

so I'd get allthis mess on my hands. That's one of the

hardest situations in my life, to stand there and you

look up and everybody is looking at you. You know

you want to knock hell out of somebody, but you

don't know who to hit.

"l'd stand there, and I caught myself a lot of times

crying, wondering sometimes where those tears

come from, just out of the blue, you know. And then

I'd get off in the afternoon and go out and find a flat

on my car. You had to change tires with it 90 some-

thing degrees out in the parking lot.

"But I didn't give up. I kept on going. I was one of

the guys who helped integrate the water fountain

out there, and it's a funny feeling to drink water out

ofa fountain, and you stand up and there's about 20

or 25 whitc guys staring at you.

"Today, I'm a winding technician, labor grade 9

right now. I have more time and experience in the

coil winding department than any other technician

there. We have six technicians. The other five are

white, but the same guy that used to walk around

and call me S.O.B. for using the fountain, he's my

supervisor. The discrimination when I worked there

in 1958 is still here right now."

Members of the Neighborhood Advisory

Council meet ever.l, three weeks at St. Mary's

Baptist Church in Athens, Georgia, to discuss

their emplo),ment discrimination suit against

Westinghouse. With help from the Legal

Defense Fund, their case goes to trialin Federal

District Court later this year.

Major D. Callaway

"l want to be given a chance. Who's to say I

couldn't have done better if they,'d given me a

chance?"

Major D. Callaway was one of the leaders among

the black employees who got together in May 1969.

Together they filed a complaint against Westing-

house with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, which seven years later found that

there was reasonable cause to believe that the

charges of employment discrimination were true.

Mr. Callaway quit Westinghouse later in 1969 after

being denied several promotions because he "lacked

drive." He later opened his own business and now

runs a successful transmission shop. He remains an

active participant in the suit.

"The reason I started this thing was because of dis-

crimination. Blacks had one restroom there, and

that's a very large plant. I was pushing one of these

big trash boxes and something got in my eye. I was

right next to a rest room when it happened, but it

didn't say 'Colored.' I went in there anyway'cause

otherwise I would have had to walk across the plant

to the'Colored' rest room to see what it was. When I

got out, there was a bunch of white men standing

around who started hassling me for going in there.

"I was mechanically inclined from the start, and I

felt I was qualified for one of the higher positions

out there. But ifyou ever spoke up or requested any-

thing, they marked you down as a troublemaker. It

was very difficult. You walk out there, somebody

scratched your car, poked holes in your tires, try to

run you off the road, all kinds of stuff. It was just

like going into hell. It just came to the point I almost

got a divorce. I'd come home, wasn't making but

560, $65 a week. Couldn't hardly live.

"l'd rather be dead than go through that again. I

want better working conditions, and I want to be

given a chance. Who's to say I couldn't have done

better if they'd given me a chance?"

Walter M. Culbreath, Sr.

"l caught myself a lot of times crying, wonder-

ing sometimes where those tears come from.

just out of the blue. you know."

Walter M. Culbreath, Sr., has worked for Westing-

house for nearly 22 years. Today he is one of the

,a\

s*\