Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief of Defendants in Error

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1947

61 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief of Defendants in Error, 1947. f6131c91-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2174bb84-5f99-4d63-973d-c7156783c9cd/sipuel-v-board-of-regents-of-uok-brief-of-defendants-in-error. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

V V W w rw W W W w v v w v w w w

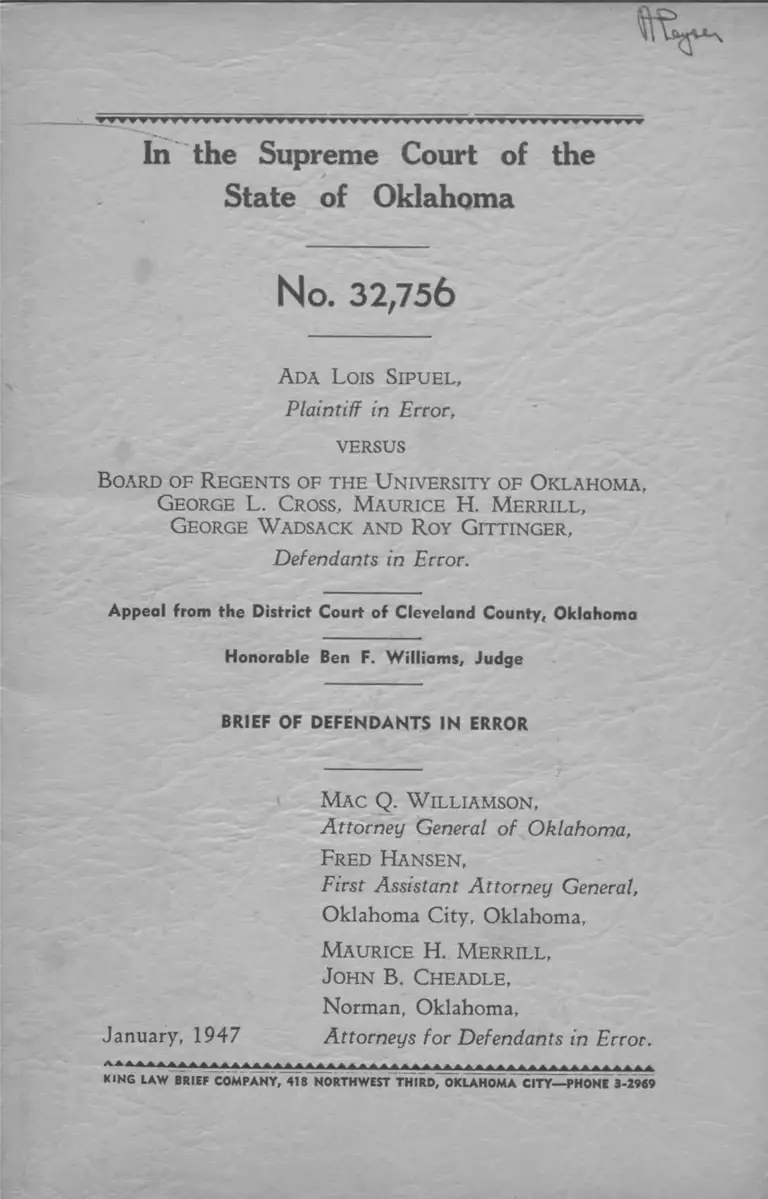

In the Supreme Court of the

State of Oklahoma

No. 32,756

A da Lois Sipuel ,

Plaintiff in Error,

VERSUS

Board of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma,

George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George W adsack and Roy Gittinger,

Defendants in Error.

Appeal from the District Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma

Honorable Ben F. Williams, Judge

BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS IN ERROR

Mac Q. W illiamson,

Attorney General of Oklahoma,

Fred Hansen ,

First Assistant Attorney General,

Oklahoma City, Oklahoma,

Maurice H. Merrill,

John B. Cheadle,

Norman, Oklahoma,

January, 1947 Attorneys for Defendants in Error.

KING LAW BRIEF COMPANY, 418 NORTHWEST THIRD, OKLAHOMA CITY— PHONE 3-2969

I N D E X

Statement of the Case __________________________ 1

Petition ___________________________ 2

Alternative Writ of Mandamus___________________ 6

Answer ______________________________________ 7

Agreed Statement of Facts_______________________ 13

Journal Entry ________________________________ 16

Motion for New Trial and Order Overruling the

Same _____________________________________ 17

Petition in E rro r____________ ,________________ 17

Argument ____________________________________ 17

Constitutional Provisions _______________________ 19

Authority:—

Board of Education of City of Guthrie v. Excise

Board of Logan County et al., 86 Okla, 24,

206 Pac. 5 1 7 _____________________________ 20

Section 1, Article 5, Constitution of Oklahoma—. 20

Section 3, Article 5, Constitution of Oklahoma— 20

Statutory Provisions ___________________________ 20

Authority:—

70 O.S. 1941, Section 455____________________ 21

The Real Issue _______________________________ 21

Propositions _________________________________ 22

PROPOSITION 1

Mandamus will not lie to require defendants:

(a) To violate the public policy of the State as

evidenced by the foregoing constitutional and

statutory provisions, or

PAGE

(b) To in effect maintain and operate the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma in

violation of 70 O.S. 1941, Section 455 (same

being a criminal statute of this State that has

never been held unconstitutional by an Ap

pellate Court thereof and which carries the

presumption of constitutionality), thereby

subjecting themselves to criminal prosecution,

by directing defendants to admit plaintiff, a colored

person, as a pupil in said school, same being at

tended only by white persons. ________________ 23

Authority:—

State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1939),

305 U.S. 337, 83 L. ed. 208 _______________ 23

70 O.S. 1941, Sections 1591, 1592 and 1593___ 24

Right to Writ of Mandamus __________________ 25

Authority:—

Payne, County Treasurer et al. v. Smith, Judge,

107 Okla. 165, 231 Pac. 469 ______________ 25

Stone v. Miracle, Dist. Judge, 196 Okla. 42,

162 Pac. (2d) 534 ______________________ 25

State ex rel. Westbrook v. Oklahoma Public

Welfare Comm, et al., 196 Okla. 586,

167 Pac. (2d) 71 ________________________ 26

12 O.S. 1941, Section 1451 _________________ 25

Pertinent Oklahoma Cases_____________________ 27

Authority:—

Huddleston v. Dwyer (C.C.A. 10),

145 Fed. (2d) 311 ______________________ 29

State ex rel. v. Boyett, 183 Okla. 49

80 Pac. (2d) 201 __________________ _____ 29

State ex rel. Decker v. Stanfield, 34 Okla. 524,

126 Pac. 239 ____________________________ 27

Witt et al. v. Wentz et al., 142 Okla. 128,

286 Pac. 798 ________________________ 28

Chapter 80, S. L. 1910-1911 ________________ 27

Section 6, Article 2, Constitution of Oklahoma__ 27

II

PAGE

I l l

PAGE

Pertinent Cases from Other States_______________ 29

Authority: —

Comley v. Boyle (Conn.). 162 Atl. 26 _______ 31

Mueller Furnace Co. v. Crockett (Utah),

227 Pac. 270 ___________________________ 30

Sharpless v. Buckles (Kan.), 70 Pac. 886 ______ 29

State v. Police Jury of Vernon Parish (La.),

3 So. (2d) 186 __________________________ 32

State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (Mo.),

113 S.W. (2d) 783 _____________________ 33

State ex rel. Hunter v. Winterrowd (Ind),

92 N.E. 650 ____________________________ 30

State ex rel. Michael v. Witham et al. (Tenn.),

165 S.W. (2d) 368 _____________________ 33

Whigham v. State (Ohio), 177 N.E. 229_____ 31

34 Amer. Jur., Page 866, Section 76__________ 33

70 O.S. 1941, Section 455 ______________ 32,'33

70 O.S. 1941, Section 456 _______________ 33

70 O.S. 1941, Section 457 _______________ 33

Conclusion as to Proposition 1 _________________ 34

PROPOSITION 2

Mandamus will not lie to require defendants to vio

late the public policy and criminal statutes of Okla

homa by directing defendants to admit plaintiff,

a colored person, to the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma, same being attended only

by white persons, especially since plaintiff has not

applied to the State Regents for Higher Education

for them, under authority of Article 13-A of the

Constitution of Oklahoma, to prescribe a school

of law as a part of the standards of higher educa

tion of Langston University, and as one of the

functions and courses of study thereof, said Uni

versity being a State institution of higher education

attended only by colored persons. _____________ 35

Authority:—

Article 21, Constitution of Oklahoma------------- 38

70 O.S. 1941, Section 1451 -------------------------- 36

70 O.S. 1941, Sections 1451 to 1509 (As amended

in 1945) _______________ 35

Section 1 of Article 13-A, Constitution of Okla

homa (Adopted March 11, 1941)---------------- 35

Section 2 of Article 13-A, Constitution of Okla

homa (Adopted March 11, 1941)---------------- 36

Section 3 of Article 13-A, Constitution of Okla

homa (Adopted March 11, 1941)--------------- 36

Duty of State Regents for Higher Education--------- 39

Authority:—

State ex rel. Bluford v. Canada (Mo.),

153 S.W.(2d) 12 ______________________ 39

Section 1, Article 1, Constitution of Oklahoma— 39

Section 1, Article 15, Constitution of Oklahoma.... 40

Plaintiff Failed to Make Due Demand---------------- 40

Authority:—

Bluford v. Canada (U.S. D.C. W.D. Mo.),

(1940), 32 Fed. Supp. 707 _______________ 44

State ex rel. Michael v. Witham et al. (Tenn.),

165 S.W. (2d) 378 ____________________ 44, 48

State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337, 83 L. ed. 208 ______________ 41

State of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (Mo.),

131 S.W. (2d) 2 1 7 ______________________ 42

Necessity of Law School for Negroes___________ 45

Authority:—

Bluford v. Canada, 32 Fed. Supp. 707------------- 47

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78, 86, 72 L. ed. 172,

177 ____________________________________ 50

State ex rel. Bluford v. Canada (Mo.),

153 S.W. (2d) 12 _______________

IT

PAGE

46, 47

PAGE

State ex rel. Michael v. Witham (Tenn),

165 S.W.(2d) 378 ______________________ 48

Knowledge of Pendency of This Suit____________ 50

Authority:—

Bluford v. Canada, 32 Fed. Supp. 707 at 710___50, 51

State ex rel. Bluford v. Canada (Mo.),

153 S.W. (2d) 12 ______________________ 50

State ex rel. Witham v. Michael (Tenn.),

165 S.W. (2d) 378 ______________________ 50

Availability of Funds _________________________ 52

Authority:—

State ex rel. Michael v. Witham (Tenn),

165 S.W. (2d) 378 ______________________ 53

Conclusion as to Proposition 2__________________ 54

In the Supreme Court of the

State of Oklahoma

No. 32,756

Ada Lois Sipuel ,

Plaintiff in Error,

VERSUS

Board of Regents of the U niversity of Oklahoma,

George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George W adsack and Roy Gittinger,

Defendants in Error.

Appeal from the District Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma

Honorable Ben F. Williams, Judge

BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS IN ERROR

STATEM ENT OF THE CASE

For convenience and sake of clarity the parties to this

appeal will be hereinafter referred to as they appeared in

the trial court, that is, the plaintiff in error, Ada Lois

A

Sipuel, as plaintiff, and the defendants in error, Board of

Regents of the University of Oklahoma et al., as de

fendants.

o Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

The statement of the case which appears on Pages

1 to 4 of plaintiff’s brief under the heading “Statement

of Case” and “Statement of Facts” is substantially correct,

but since the same does not set forth or abstract the plead

ings and the material orders of the trial court, defendant,

for the information of this Court will hereinafter quote

or abstract said pleadings and orders in proper sequence.

Petition

The petition in this case was filed by plaintiff in the

District Court of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, on the

6th day of April, 1946. Said petition (C.-M. 4-11),

omitting its caption, signatures and verification, is as fol

lows:

“Now comes the plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, and for

her cause of action against the defendants and each

of them alleges and states:

“ 1. That she is a resident and citizen of the United

States and of the State of Oklahoma, County of

Grady, and city of Chickasha. She desires to study

law in the School of Law of the University of Okla

homa, which is supported and maintained by the tax

payers of the State of Oklahoma, for the purpose of

preparing herself to practice law in the State of Okla

homa and for public service therein and has been arbi

trarily refused admission.

“2. That on January 14, 1946, plaintiff duly ap

plied for admission to the first year class of the school

of law of the University of Oklahoma. She then pos

sessed and still possesses all the scholastic, moral and

other lawful qualifications prescribed by the Con

stitution and statutes of the State of Oklahoma, by

the Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma

and by all duly authorized officers and agents of the

said University and the school of law for admission

Brief of D efendants in Error 3

into the first year class of the school of law of the said

University. She was then and still is ready and willing

to pay all lawful uniform fees and charges and to

conform to all lawful uniform rules and regulations

established by lawful authority for admission to said

class. Plaintiff’s application was arbitrarily and il

legally rejected pursuant to a policy, custom or usage

of denying to qualified Negro applicants the equal

protection of the laws solely on the ground of her

race and color.

“3. That the school of law of the University of

Oklahoma is the only law school in the state main

tained by the state and under its control and is the

only law school in Oklahoma that plaintiff is quali

fied to attend. Plaintiff desires that she be admitted

in the first year class of the school of law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma at the next regular registration

period for admission to such class or at the first regu

lar registration period after this cause has been heard

and determined and upon her paying the requisite

uniform fees and conforming to the lawful uniform

rules and regulations for admission to such classes.

“4. That the defendant Board of Regents of the

University of Oklahoma is an administrative agency

of the State and exercises overall authority with ref

erence to the regulation of instruction and admission

of students in the University, a corporation organized

as a part of the educational system of the State and

maintained by appropriations from the public funds

of the State raised by taxation from the citizens and

taxpayers of the State of Oklahoma. The defendant,

George L. Cross, is the duly appointed, qualified and

acting President of the said University and as such

is subject to the authority of the Board of Regents

as an immediate agent governing and controlling the

several colleges and schools of the said University.

The defendant, Maurice H. Merrill, is the Dean of the

school of law of the said University whose duties

comprise the government of the said law school in

cluding the admission and acceptance of applicants

eligible to enroll as students therein, including your

4

plaintiff. The defendant, Roy Gittinger, is the Dean

of admissions of the said University and the defendant

George Wadsack is the Registrar thereof, both possess

ing authority to pass upon the eligibility of applicants

who seek to enroll as students therein, including your

plaintiff. All of the personal defendants come under

the authority, supervision, control and act pursuant

to the orders and policies established by the defendant

Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma.

All defendants herein are being sued in their official

capacity.

“5. That the school of law specializes in law and

procedure which regulates the courts of justice and

government in Oklahoma and there is no other law

school maintained by the public funds of the state

where plaintiff can study Oklahoma law and pro

cedure to the same extent and on an equal level of

scholarship and intensity as in the school of law of

the University of Oklahoma. The arbitrary and il

legal refusal of defendants Board of Regents, George L.

Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy

Gittinger, to admit plaintiff to the first year of the

said law school solely on the ground of race and color

inflicts upon your plaintiff an irreparable injury and

will place her at a distinct disadvantage at the bar

of Oklahoma and in the public service of the afore

said state with persons who have had the benefit of

the unique preparation in Oklahoma law and pro

cedure offered to white qualified applicants in the law

school of the University of Oklahoma.

“6. That the requirements for admission to the

first year class of the school of law are as follows:

applicants must be at least eighteen (18) years of

age and must have graduated from an accredited high

school and completed two full years of academic col

lege work. In addition applicants must have main

tained at least one grade point for each semester car

ried in college or two grade points during the last

college year of not less than thirty semester hours.

Plaintiff is over eighteen (18) years of age, has com

pleted the full college course at Langston University,

Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.________

Brief of D efendants in Error 5

a college maintained and operated by the State of

Oklahoma for the higher education of its Negro citi

zens. Plaintiff maintained one grade point for each

semester point carried and graduated from the above

named college with honors. She is of good moral

character and has in all particulars met the qualifica

tions necessary for admittance to the school of law of

the University of Oklahoma which fact defendants

have admitted. She is ready, willing and able to pay

all lawful charges and tuition requisite to admission

to the first year of the school of law and she is other

wise ready, willing and able to comply with all law

ful rules and regulations requisite for admission there

in.

“7. On January 14, 1946, plaintiff applied for

admission to the school of law of the University of

Oklahoma and complied with all the rules and regu

lations entitling her to admission by filing with the

proper officials of the University an official transcript

of her scholastic record. Said transcript was duly

examined and inspected by the President, Dean of the

School of Law and Dean of Admissions and Registrar

of the University; defendants aforementioned, and

found to be an official transcript as aforesaid entitling

her to admission to the school of law of the Univer

sity. Plaintiff was denied admission to the school of

law solely on the ground of race and color in violation

of the Constitution and laws of the United States and

of the State of Oklahoma.

“8. Defendants have established and are main

taining a policy, custom and usage of denying to

qualified Negro applicants the equal protection of the

laws by refusing to admit them into the law school

of the University of Oklahoma solely because of race

and color and have continued the policy of refusing

to admit qualified Negro applicants into the said school

while at the same time admitting white applicants

with less qualifications than Negro applicants solely

on account of race and color.

“9. The defendants, George L. Cross, Maurice H.

Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy Gittinger refuse

G Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

to act upon plaintiff’s application and although ad

mitting that plaintiff possesses all the qualifications

necessary for admission to the first year in the school

of law, refused her admission on the ground that the

defendant Board of Regents had established a policy

that Negro qualified applicants were not eligible for

admission in the law school of the University of Okla

homa solely because of race and color. Plaintiff ap

pealed directly to the Board of Regents for admission

to the first year class of the law school of said Univer

sity and such board has so far refused to act in the

premises.

“ 10. Plaintiff further shows that she has no

speedy, adequate remedy at law and that unless a Writ

of Mandamus is issued she will be denied the right and

privilege of pursuing the course of instruction in the

school of law as hereinbefore set out.

“WHEREFORE, plaintiff being otherwise remediless,

prays this Honorable Court to issue a Writ of Manda

mus requiring and compelling said defendants to com

ply with their statutory duty in the premises and

admit the plaintiff in the school of law of the said

University of Oklahoma and have such other and fur

ther relief as may be just and proper.”

Alternative Writ of Mandamus

Thereafter, and on the 9th day of April, 1946, the

District Court of Cleveland County issued its alternative

writ of mandamus (C.-M. 11-18), but since the allega-

gations of Paragraphs 1 to 10 thereof are identical with

Paragraphs 1 to 10 of Plaintiff’s petition (heretofore

quoted), and since the only difference between said peti

tion and alternative writ is that at the conclusion of said

writ the order of the trial court is set forth instead of the

prayer of said petition, defendant, for sake of brevity, is

quoting herein only said order of said writ (C.-M. 16-17),

as follows:

Brief of D efendants in Error 7

“T herefore, the Court being fully advised in the

premises finds that an Alternative Writ of Mandamus

should be issued herein.

“It Is T herefore Ordered, Considered and

ADJUDGED that all of the said defendants, Board of

Regents of the University of Oklahoma, George L.

Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, and George Wadsack, each

and all of them, are hereby commanded that immedi

ately after receipt of this writ, you admit into the

School of Law of the said University of Oklahoma,

the said plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, or that you and

each and all of you, the said defendants, appear be

fore this court at 10:00 o’clock A.M., on the 26th

day of April, 1946, to show cause for your refusal

so to do and that you then and there return this writ

together with all proceedings thereof.’’

Answer

Thereafter, and on the 14th day of May, 1946, de

fendants filed their answer (C.-M. 24-32) to the petition

of plaintiff and to said alternative writ of mandamus.

Said answer, omitting its caption, signatures and verifi

cation, is as follows:

“Comes now the above-named defendants, and each

of them, and in answer to the petition of plaintiff

and the alternative writ of mandamus issued herein,

allege and state:

“ 1. That the material allegations of fact set forth

in plaintiff’s petition and in said alternative writ of

mandamus are not sufficient to constitute a cause of

action in favor of plaintiff and against defendants,

or either of them.

“2. That defendants, and each of them, deny

the material allegations of fact set forth in Paragraphs

1 to 10, inclusive, plaintiff’s petition and in said al

ternative writ of mandamus (said paragraphs being

identical in said petition and writ both as to number

and phraseology), except such allegations as are here

inafter alleged or admitted.

“3. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 1 of said petition and writ,

except the allegation that plaintiff was ‘arbitrarily re

fused admission to the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma.

“4. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 2 of said petition and writ,

except the allegation that plaintiff possessed all ‘other

lawful qualifications’ for admission to the first year

class of the School of Law of the University of Okla

homa, and the allegation that plaintiff's application

for admission to said class was ‘arbitrarily and illegally

rejected.’

“5. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 3 of said petition and writ,

except the allegation which implies that plaintiff is

‘qualified to attend’ the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma.

“6. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 4 of said petition and writ.

“ 7. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 5 of said petition and writ,

except the allegation which implies that the refusal

of defendants to admit plaintiff to the first year class of

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma was

an ‘arbitrary and illegal refusal.’

“8. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 6 of said petition and writ,

except the allegation that plaintiff has ‘in all particu

lars met the qualifications necessary for admittance to

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma

which fact defendants have admitted,’ and in this con

nection allege that while plaintiff is ‘scholastically

qualified for admission to the Law School of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma’ (which fact has been admitted

by defendant), she does not have the qualifications

necessary for admittance at said school for the reason

that under the constitutional and statutory provisions

of this State, hereinafter cited and reviewed (Para

graphs 14 to 21 hereof), only white persons are eli

gible for admission to said school.

8 _______ Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.________

Brief of D efendants in Error <)

“9. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 7 of said petition and

writ, but deny the conclusion of law therein that the

refusal of defendants to admit plaintiff to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma on the ground

of race and color was ‘in violation of the Constitution

and laws of the United States and of the State of

Oklahoma.’

“ 10. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 8 of said petition and writ,

but deny the conclusion of law therein that the ‘policy,

custom and usage’ of defendants in refusing to admit

negro applicants, otherwise qualified, to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma, while con

tinuing to admit white applicants, otherwise qualified,

is a denial to said negro applicants of ‘the equal pro

tection of the laws.’

“ 11. Defendants admit the material allegations of

fact set forth in Paragraph 9 of said petition and writ,

except the allegation which implies that the defend

ants, George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill, George

Wadsack and Roy Gittinger, have admitted that plain

tiff ‘possesses all the qualifications necessary for ad

mission to the first year in the school of law’ of the

University of Oklahoma, and the allegation which

implies that plaintiff was denied admission by de

fendants to said school solely ‘on the ground that the

defendant, Board of Regents, had established a policy

that negro qualified applicants were not eligible for

admission in the law school of the University of

Oklahoma solely because of race and color,’ and in

this connection allege that plaintiff was denied admis

sion by said defendants to said school not only by

virtue of said policy, but by reason of the constitu

tional and statutory provisions of the State of Okla

homa, hereinafter cited and reviewed (Paragraphs 14

to 21 hereof).

“ 12. Defendants deny the conclusions of law set

forth in Paragraph 10 of said petition and writ.

“ 13. Defendants, and each of them, allege and

admit that the plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, a colored

10 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

or negro citizen and resident of the United States of

America and the State of Oklahoma, duly and timely

applied on January 14, 1946, for admission to the

first year class of the School of Law of the Univer

sity of Oklahoma for the semester beginning Janu

ary 15, 1946, and that she then possessed and still

possesses all the scholastic and moral qualifications

required for such admission by the constitution and

statutes of this State and by the Board of Regents of the

University of Oklahoma, but deny that she was then

possessed and still possesses all ‘other qualifications’

required by said constitution, statutes and board, for

the reason that under the public policy of this State

announced in the constitutional and statutory pro

visions hereinafter cited and reviewed (Paragraphs

14 to 21 hereof), colored persons are not eligible for

admission to a State school established for white per

sons, such as the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma.

“ 14. That Section 3, Article 13 of the Constitu

tion of Oklahoma provides, in part, that:

“ ‘Separate Schools for white and colored chil

dren with like accommodation shall be provided

by the Legislature and impartially maintained.’

“ 15. That 70 O. S. 1941 § 363 provides in part

that:

“ ‘All teachers of the negro race shall attend

separate institutions from those for teachers of

the white race, *

“ 16. That 70 O. S. 1941 § 455 makes it a mis

demeanor, punishable by a fine of not less than $100.-

00 nor more than $500.00, for

“ '* * any person, corporation or association of

persons to maintain or operate any college, school

or institution of this State where persons of both

white and colored races are received as pupils for

instruction, * *’

and provides that each day same is so maintained or

operated ‘shall be deeded a separate offense.’

Brief of D efendants in Error 11

“ 17. That 70 O. S. 1941 § 456 makes it a mis

demeanor, punishable by a fine of not less than $10.00

nor more than $50.00, for any instructor to teach

“ ‘* * in any school, college or institution where

members of the white race and colored race are

received and enrolled as pupils for instruction, * *’

and provides that each day such an instructor shall

continue to so teach ‘shall be considered a separate

offense.’

“ 18. That 70 O. S. 1941 § 457 makes it a mis

demeanor, punishable by a fine of not less than $5.00

nor more than $20.00, for

“ * any white person to attend any school,

college or institution, where colored persons are

received as pupils for instruction, * *’

and provides that each day such a person so attends

‘shall be deemed a distinct and separate offense.’

“ 19. That 70 O.S. 1941 § § 1591, 1592 and

1593, in effect, provide that if a colored or negro resi

dent of the State of Oklahoma who is morally and

educationally qualified to take a course of instruction

in a subject taught only in a State institution of higher

learning established for white persons, the State will

furnish him like educational facilities in comparable

schools of other States wherein said subject is taught

and in which said colored or negro resident is eligible

to attend.

“20. That the material part of Senate Bill No.

9 of the Twentieth Oklahoma Legislature (same be

ing the general departmental appropriation bill for the

fiscal years ending June 30, 1946 and June 30, 1947),

which was enacted to finance the provisions of 70

O.S. 1941 § § 1591, 1592 and 1593, supra, is as

follows:

1 2 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

‘STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION

Fiscal Year Fiscal Year

ending ending

June 30, 1946 June 30, 1947

‘For payment of Tui

tion Fees and trans

portation for certain

persons attending in

stitutions outside the

State of Oklahoma as

provided by law. ___$15,000.00 $15,000.00.’

“21. That 70 O. S. 1941 § § 1451 to 1509, as

amended in 1945, established a State institution of

higher learning now known as ‘Langston University’

for ‘male and female colored persons’ only, which in

stitution, however, does not have a school of law.

“22. That the constitutional and statutory pro

visions of Oklahoma, heretofore cited and reviewed

(Paragraphs 14 to 21 hereof), have been uniformly

construed by defendants and their predecessors as pro

hibiting the admission of persons of the colored or

negro race to the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma, and pursuant to such interpretation it

has been their administrative practice to admit only

white persons, otherwise qualified, to said school.

“23. That petitioner has not applied, nor in her

petition and/or alternative writ of mandamus alleged

that she has applied, to the Board of Regents of Higher

Education of this State for it, under authority of Ar

ticle 13a of the Constitution of Oklahoma, to pre

scribe a school of law similar to the school of law of

the University of Oklahoma as a part of the standards

of higher education of Langston University, and as

one of the courses of study thereof, so that she will

be able as a negro citizen of the United States and

the State of Oklahoma to attend said school without

violating the public policy of said State as evidenced

by the constitutional and statutory provisions of Okla

homa heretofore cited and reviewed (Paragraphs 14

to 21 hereof).

Brief of D efendants in Error 13

“24. That by reason of the foregoing constitu

tional and statutory provisions and administrative

interpretation and practice, it cannot properly be said

that ‘the law specifically enjoins’ upon defendants,

or either thereof (within the meaning of 12 O. S.

1941 § § 1451 to 1462, inclusive, relating to ‘Man

damus’), the duty of admitting plaintiff to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma.

“WHEREFORE, premises considered, defendants, and

each of them, respectfully ask the court to decline to

issue the writ of mandamus prayed for in this cause,

that plaintiff take nothing by her petition, and that

defendants recover their cost herein expended.’’

Agreed Statement of Facts

The case came on for hearing (C.-M. 34-37) before

the Honorable Ben T. Williams, District Judge, on the

9th day of July, 1946, at which time plaintiff introduced

in evidence as “Plaintiff’s Exhibit 1” an “Agreed State

ment of Facts” (C.-M. 38-42). Said statement, omitting

its caption and signatures, is as follows:

“That the Plaintiff is a resident and citizen of the

United States and of the State of Oklahoma, County

of Grady and City of Chickasha, that she desires to

study law in the School of Law in the University of

Oklahoma for the purpose of preparing herself to

practice law in the State of Oklahoma.

“2. That the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma is the only Law School in the State main

tained by the State and under its control.

“3. That the Board of Regents of the University

of Oklahoma is an administrative agency of the State

and exercising overall authority with reference to the

regulation of instruction and admission of students

in the University: that the University is a part of the

educational system of the State and is maintained by

appropriations from the public funds of the State

u Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

raised by taxation from the citizens and taxpayers

of the State of Oklahoma; that the School of Law

of Oklahoma University specializes in law and pro

cedure which regulates the Court of Justice and Gov

ernment of Oklahoma; that there is no other law

school maintained by the public funds of the State

where the plaintiff can study Oklahoma law and pro

cedure to the same extent and on an equal level of

scholarship and intensity as in the School of Law of

the University of Oklahoma; that the plaintiff will

be placed at a distinct disadvantage at the bar of

Oklahoma and in the public service of the aforesaid

State with persons who have had the benefit of the

unique preparation in Oklahoma law and procedure

offered to white qualified applicants in the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma, unless she is

permitted to attend the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma.

“4. That the plaintiff has completed the full col

lege course at Langston University, a college main

tained and operated by the State of Oklahoma for

the higher education of its Negro citizens.

“5. That the plaintiff duly and timely applied

for admission to the first year class of the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma on January 14,

1946, for the semester beginning January 15, 1946

and that she then possessed and still possesses all the

scholastic and moral qualifications required for such

admission.

“6. That on January 14, 1946, when plaintiff

applied for admission to the said school of law, she

complied with all of the rules and regulations en

titling her to admission by filing with the proper

officials of the University, an official transcript of her

scholastic record; that said transcript was duly ex

amined and inspected by the President, Dean of Ad

missions and Registrar of the University and was

found to be an official transcript, as aforesaid, en

titling her to admission to the School of Law of the

said University.

Brief of D efendants in Error 15

“7. That under the public policy of the State of

Oklahoma, as evidenced by the constitutional and

statutory provisions referred to in defendants' answer

herein, plaintiff was denied admission to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma solely because

of her race and color.

“8. That the plaintiff at the time she applied for

admission to the said law school of the University

of Oklahoma was and is now ready and willing to

pay all of the lawful charges, fees and tuitions re

quired by the rules and regulations of the said Uni

versity.

“9. That plaintiff has not applied to the Board

of Regents of Higher Education of the State of Okla

homa for it, under authority of Article 13-A of the

Constitution of Oklahoma, to prescribe a School of

Law similar to the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma as a part of the standards of higher

education of Langston University, and as one of the

courses of study thereof.”

Thereafter, and at said hearing, plaintiff introduced

as “Plaintiff’s Exhibit 2” an additional stipulation (C.-M.

43), same being as follows:

“It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between

counsel for plaintiff and defendants that the court

may consider the following as an admitted fact:

“That after the filing of this cause the Board of

Regents of Higher Education, having knowledge there

of, met and considered the questions involved therein:

that it had no unallocated funds in its hands or under

its control at that time with which to open up and

operate a law school and has since made no allocation

for that purpose; that in order to open up and operate

a law school for negroes in this State, it will be nec

essary for the board to either withdraw existing allo

cations, procure moneys, if the law permits, from

the Governor’s contingent fund, or make an applica

tion to the next Oklahoma Legislature for funds suffi

cient to not only support the present institutions of

16 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

higher education but to open up and operate said

law school; and that the Board has never included

in the budget which it submits to the Legislature an

item covering the opening up and operation of a law

school in the State for negroes and has never been re

quested to do so.”

Journal Entry

Thereafter, and on the 6th day of August, 1946,

the ‘‘Journal Entry” in said case (C.-M. 52-54), approved

by counsel for both plaintiff and defendants, was duly

filed in the trial court. Said Journal Entry, omitting its

caption, signature and approvals, is as follows:

‘‘This cause coming on to be heard on this the 9th

day of July, 1946, pursuant to regular assignment for

trial, the said plaintiff being present by her attorney,

Amos T. Hall, and the said defendants by their attor

neys, Fred Hansen, First Assistant Attorney General,

and Maurice H. Merrill; and both parties announcing

ready for trial and a jury being waived in open court,

the court proceeded to hear the evidence in said case

and the argument of counsel, said evidence being pre

sented in the form of a signed ‘Agreed Statement of

Facts’ and a supplemental agreed statement of facts.

‘‘And the court, being fully advised, on considera

tion finds that the allegations of plaintiff’s petition

are not supported by the evidence and the law, and

the judgment is, therefore, rendered for the defendants,

and it is adjudged that the defendants go hence with

out day and that they recover their costs from the

plaintiff; to which findings and judgment plaintiff

then and there excepted, and thereupon gave notice

in open court of her intention to appeal to the Supreme

Court of the State of Oklahoma, and asked that such

intentions be noted upon the minutes, dockets and

journals of the Court and it is so ordered and done,

and plaintiff praying an appeal is granted an exten

sion of 15 days in addition to the time allowed by

Statute to make and serve case-made, defendants to

Brief of D efendants in Error 17

have 3 days thereafter to suggest amendments there

to, same to be settled and signed upon 3 days notice

in writing by either party.”

Motion for New Trial and Order Overruling the Same

Thereafter, and on the 11th day of July, 1946, a

motion for a new trial (C.-M. 46-47) was duly filed by

plaintiff, which motion was on the 24th day of July,

1946 overruled by order of the trial court (C.-M. 47-

48), at which time plaintiff gave notice in open court of

her intention to appeal to this Court.

Petition in Error

The appeal in this case was duly lodged in this Court

on the 17th day of August, 1946, the petition in error

alleging:

“ 1. Error of the court in denying the petition of

the plaintiff for a writ of mandamus.

“2. Errors of law occurring at the trial which

were accepted to by the plaintiff.”

ARGUMENT

There is but one real issue involved in this case and

that is whether or not the trial court erred in declining to

issue a writ of mandamus, as prayed for by plaintiff, to

require the defendants, Board of Regents of the Univer

sity of Oklahoma, George L. Cross, Maurice H. Merrill,

George Wadsack and Roy Gittinger, to admit the plain

tiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, to the School of Law of the Uni

versity of Oklahoma.

In this connection it will be noted that plaintiff, as

a basis for this action in mandamus, alleged in her peti

1 8 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

tion that although she was duly qualified to attend the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma when she

on January 14, 1946, “duly applied for admission to

the first year class’’ of said school, she was by defendants

“* * arbitrarily refused admission” (Para. 1 of pltf’s,

pet.),

and

“* * arbitrarily and illegally rejected” (Para. 2 of

pltf’s. pet.),

solely because of her race and color, and that said refusal

or rejection was

“* * arbitrary and illegal” (Para. 5 of pltf’s. pet.).

It will also be noted that while said charge of ar

bitrary and illegal action on the part of defendants was

specifically denied thereby (Paragraphs 3, 4 and 7 of de

fendants’ answer), they admitted in Paragraph 13 of said

answer that plaintiff

“* * duly and timely applied on January 14, 1946

for admission to the first year class of the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma for the semester

beginning January 15, 1946, and that she then pos

sessed and still possesses all the scholastic and moral

qualifications required for such admission by the con

stitution and statutes of this State and by the Board

of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, * *”

but denied in said paragraph that plaintiff was legally

qualified to attend said school

“* * for the reason that under the public policy of

this State announced in the constitutional and statu

tory provisions hereinafter cited and reviewed (Para

graphs 14 to 21 of said answer), colored persons are

not eligible for admission to a State school established

for white persons, such as the School of Law of the

University of Oklahoma.”

Brief of D efendants in Error 19

It will be further noted that the reason given by de

fendants, as aforesaid, for rejecting plaintiff’s said appli

cation of January 14, 1946, is in harmony with the seventh

numbered paragraph of the “Agreed Statement of Facts”

herein (Page 15 of this brief), same being as follows:

“That under the public policy of the State of Okla

homa, as evidenced by the constitutional and statutory

provisions referred to in defendants’ answer herein,

plaintiff was denied admission to the School of Law

of the University of Oklahoma solely because of her

race and color.”

It is, therefore, clear that if this Court finds that when

plaintiff applied on January 14, 1946, for admission to

the first year class of the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma for the semester beginning January 15, 1946,

her application was arbitrarily and illegally refused or re

jected by defendants, the writ of mandamus prayed for by

plaintiff should be issued.

It is likewise clear that if by reason of the constitu

tional and statutory public policy of Oklahoma as to seg

regation of the white and negro races in educational in

stitutions of the state, defendants did not act arbitrarily

and illegally in refusing or rejecting said application, the

writ of mandamus prayed for by plaintiff should not be

issued.

Constitutional Provisions

The constitutional provisions referred to in said sev

enth numbered paragraph of the “Agreed Statement of

Facts” herein (Page 15 of this brief), are set forth as Sec

tions 1 and 3, Article 5 of the Constitution of this State,

as follows:

20

“ 1. The Legislature shall establish and maintain

a system of free public schools wherein all the chil

dren of the State may be educated.

“3. Separate schools for white and colored chil-

ren with like accommodation shall be provided by the

Legislature and impartially maintained. The term

'colored children,’ as used in this section, shall be con

strued to mean children of African descent. The term

‘white children’ shall include all other children.”

Said sections were treated as valid by this Court in

Board of Education of City of Guthrie V. Excise Board

of Logan County et al., 86 Okla. 24, 206 Pac. 517, the

first paragraph of the syllabus of said case being as follows:

‘‘Under Sections 1 and 3 of Article 13 of the Con

stitution of Oklahoma, it is the duty of the Legis

lature to provide for the maintenance of a system of

free public schools wherein all of the children of the

state may be educated, and to provide for separate

schools for white and colored children with like

accommodations, and impartially maintain such

schools.”

While the above constitutional provisions may not

be directly applicable to state institutions of higher learn

ing, such as the University of Oklahoma, they at least

reveal a public policy which is in harmony with the statu

tory provisions hereinafter cited which are directly appli

cable to state institutions of higher learning, including

the University of Oklahoma.

Statutory Provisions

The statutory provisions referred to in the seventh

numbered paragraph, supra, of the ‘‘Agreed Statement of

Facts” herein (Page 15 of this brief), are set forth as Para

graphs 15 to 21 of defendants’ answer (Pages 10-12 of

Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

Brief of D efendants in Error 21

this brief). Said statutory provisions, for sake of brevity,

are not quoted here, but the Court’s attention is respect

fully invited thereto.

However, as the statutory provisions chiefly relied

upon by defendants are set forth in Paragraph 16, supra,

said paragraph is quoted herein, as follows:

“70 O. S. 1941 § 455 makes it a misdemeanor pun

ishable by a fine of not less than $100.00 nor more

than $500.00, for

* any person, corporation or association of

persons to maintain or operate any college, school

or institution of this State where persons of both

white and colored races are received as pupils for

instruction,’

and provides that each day same is so maintained or

operated ‘shall be deemed a separate offense.’ ”

The Real Issue

The real and only issue involved in this case is set

forth in the first paragraph (Page 17 of this brief) of our

“Argument” herein, same being as follows:

“There is but one real issue involved in this case and

that is whether or not the trial court erred in declining

to issue a writ of mandamus, as prayed for by plain

tiff, to require the defendants, Board of Regents of

the University of Oklahoma, George L. Cross, Maurice

H. Merrill, George Wadsack and Roy Gittinger, to

admit the plaintiff, Ada Lois Sipuel, to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma.”

In discussing the above issue defendants deem it ad

visable to present their argument under two propositions,

same being as follows:

22 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

1.

Mandamus will not lie to require defendants:

(a) to violate the public policy of the State as evi

denced by the foregoing constitutional and statu

tory provisions, or

(b) to in effect maintain and operate the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma in violation

of 70 O. S. 1941 § 455 (same being a criminal

statute of this State that has never been held

unconstitutional by an appellate court thereof

and which carries the presumption of constitu

tionality), thereby subjecting themselves to crim

inal prosecution,

by directing defendants to admit plaintiff, a colored

person, as a pupil in said school, same being attended

only by white persons.

2.

Mandamus will not lie to require defendants to

violate the public policy and criminal statutes of Okla

homa by directing defendants to admit plaintiff, a

colored person, to the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma, same being attended only by white per

sons, especially since plaintiff has not applied to the

State Board of Regents for Higher Education, under

authority of Article 13-A of the Constitution of

Oklahoma, to prescribe a school of law as a part of

the standards of higher education of Langston Uni

versity, and as one of the functions and courses of

study thereof, said university being a State institution

of higher education attended only by colored persons.

Brief of D efendants in Error 23

PROPOSITION 1

Mandamus will not lie to require defendants:

(a) To violate the public policy of the State as evidenced

by the foregoing constitutional and statutory provisions,

or

(b) To in effect maintain and operate the School of Law

of the University of Oklahoma in violation of 70 O. S.

1941, § 455 (same being a criminal statute of this

State that has never been held unconstitutional by an

Appellate Court thereof and which carries the presump

tion of constitutionality), thereby subjecting themselves

to criminal prosecution,

by directing defendants to admit plaintiff, a colored person,

as a pupil in said school, same being attended only by white

persons.

Before discussing the above proposition defendants

desire to call attention to Pages 4 to 19 of plaintiff’s brief,

where, under the heading

“The refusal to admit plaintiff in error to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma constitutes a

denial of rights secured under the Fourteenth Amend

ment,”

argument is set forth in Subheads A to E to the effect

that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States is violated by State constitutional and statu

tory provisions unless the same permits colored persons to

attend schools attended by white persons, and that this

is true even though separate schools for the colored are

equal in every respect to those for the white.

Defendants deem it unnecessary to answer said argu

ment other than to call attention to the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States in the case of State

of Missouri ex rel. Gaines V. Canada (decided January 3,

1939), 305 U.S. 337, 83 L.ed. 208, which is the case

24: Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

chiefly relied upon by plaintiff here. In this connection

we quote the following language therefrom:

“* * the state court has fully recognized the obligation

of the State to provide negroes with advantages for

higher education substantially equal to the advantages

afforded to white students. The State has sought to

fulfill that obligation by furnishing equal facilities in

separate schools, a method the validity of which has

been sustained by our decisions. Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U.S. 537, 544, 41 L. ed. 256, 258, 16 S. Ct.

1138; McCabe V. Atchison, T . & S. F. R. Co., 235

U.S. 151, 160, 59 L. ed. 169, 173, 35 S. Ct 69;

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U.S. 78, 86, 72 L. ed. 172,

176, 177, 48 S. Ct. 91.”

However, under Subhead E of said heading, plain

tiff properly argues that under the decision of the United

States Supreme Court in the Gaines case, supra, it is the

duty of a State having laws providing for segregation of

the colored and white races in its schools to provide sub

stantially equal educational facilities for both colored and

white students, and that such facilities are not furnished

under State laws, such as are set forth in 70 O. S. 1941

§ § 1591, 1592 and 1593, which, as stated in Paragraph 9

of defendants’ answer brief herein (Page 9 of this brief),

“* * in effect, provide that if a colored or negro resi

dent of the State of Oklahoma who is morally and

educationally qualified to take a course of instruction

in a subject taught only in a State institution of higher

learning established for white persons, the State will

furnish him like educational facilities in comparable

schools of other States wherein said subject is taught

and in which said colored or negro resident is eligible

to attend.”

Brief of D efendants in Error 25

Right to Writ of Mandamus

In relation to the right of issuance of a writ of

mandamus in this State, attention is called to 12 O. S.

1941, § 1451, same being as follows:

“The writ of mandamus may be issued by the Su

preme Court or the district court, or any justice or

judge thereof, during term, or at chambers, to any in

ferior tribunal, corporation, board or person, to com

pel the performance of any act which the law specially

enjoins as a duty, resulting from an office, trust or

station; but though it may require an inferior tribunal

to exercise its judgment or proceed to the discharge

of any of its functions, it cannot control judicial dis

cretion.”

This Court, in construing the right to the issuance

of a writ of mandamus under the above section, held in

the second paragraph of the syllabus of Payne, County

Treasurer et al. V. Smith, Judge, 107 Okla. 165, 231

Pac. 469, as follows:

“To sustain a petition for mandamus petitioner

must show a legal right to have the act done sought

by the writ, and also that it is plain legal duty of the

defendant to perform the act.”

In the case of Stone V. Miracle, Dist. Judge, 196

Okla. 42, 162 Pac. (2d) 534, the syllabus is as follows:

“Mandamus is a writ awarded to correct an abuse

of power or an unlawful exercise thereof by an in

ferior court, officer, tribunal or board by which a liti

gant is denied a clear legal right, especially where the

remedy by appeal is inadequate or would result in

inexcusable delay in the enforcement of a clear legal

right.”

2G Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

In the recent case of State ex rel. Westbrook V. Okla

homa Public Welfare Comm, et al, 196 Okla. 586, 167

Pac. (2d) 71, this Court held in the second paragraph of

the syllabus, as follows:

“Where the state has created a board and vested in

it power to make final decisions on issues of fact and

does not provide for an appeal to a court for a ju

dicial review of the correctness of the finding, the dis

cretion of that board, based upon the evidence taken

by it, will not, in the absence of arbitrary or capricious

action, be controlled by the courts of Oklahoma by

writs of mandamus

The principles of law announced in the above cases

are in harmony with the general rule which appears in

34 Am. Jur., Page 867, § 78, as follows:

“The office of mandamus is to compel the perform

ance of a specific and positive duty imposed by law,

and the writ will not be granted unless it appears that

there has been a plain breach or dereliction of duty

on the part of the respondent.’’

In the case at bar plaintiff evidently recognizes the

principles of law announced in the above decisions and

general rule, since in the second numbered paragraph of

her petition (Page 2 of this brief) she alleges that her

application

“was arbitrarily and illegally rejected”

by defendants.

Said allegation was denied by defendants in the fourth

numbered paragraph of their answer (Page 8 of this brief),

wherein it is stated:

“Defendants admit the material allegations of fact

set forth in Paragraph 2 of said petition * * except

* * the allegation that plaintiff’s application for ad-

27

mission to said class was ‘arbitrarily and illegally re

jected.’ ”

The essential question, therefore, involved in this

case is whether or not defendants on January 14, 1946.

“arbitrarily and illegally rejected’’ the application of plain

tiff for admission to the School of Law of the University

of Oklahoma.

________Brief of D efendants in Error

Pertinent' Oklahoma Cases

Proposition 1 of this brief is supported by the case

of State ex rel. Decker V. Stanfield, 34 Okla. 524, 126

Pac. 239, wherein this Court held that while under the

provisions of Section 6, Article 2 of our State Constitution

a person accused of crime has the right “to a speedy trial”

etc., such fact did not mean that he could enforce said con

stitutional right if the enforcement thereof would require

expenses to be incurred in violation of “Chapter 80, Sess.

Laws 1910-11.” In this connection attention is called to

the second paragraph of the syllabus of said case, same

being as follows:

“When the court expense fund has been exhausted,

mandamus will not issue to compel the district judge

to impanel a jury or incur expenses payable out of

that fund, as Chapter 80, Sess. Laws 1910-11, pro

hibits any officer from incurring, authorizing, or ap

proving a charge against an exhausted fund.”

In the body of the opinion, at Page 528, it is stated:

“It is argued, however, that Section 6 of Article Z

of the Constitution, which provides that ‘the courts

of justice of the state shall be open to every person,

and speedy and certain remedy afforded for every

wrong and for every injury to person, property, or

reputation, and right and justice shall be administered

28 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

without sale, denial, delay, or prejudice, ‘requires that

this provision of the state (Chapter 80, Sess. Laws

1910-11) be submerged in the necessity of granting

to persons accused of crime the right to a speedy trial.

We do not think so. We think this section of the

Constitution must be enforced, but that it must be en

forced in accordance with the law. We do not think

it means that, regardless of the statute, regardless of

the fiscal arrangements of the state, and regardless of

the interests of the taxpayers, courts shall proceed in

violation of the law. The courts, being charged with

the duty of administering the law, should be most

astute not to violate it.”

In the case of W itt et at. V. Wentz et al., 142 Okla.

128, 286 Pac. 798, this Court held that mandamus will

not issue to require an executive officer to perform a duty

(such as is involved here) which requires him to exercise

“* * his judgment and discretion in the construction

of the law or in determining the existence and effect

of the facts.”

In this connection we quote the pertinent part of

the first paragraph of the syllabus of said case, as follows:

‘‘A writ of mandamus * * may not lawfully issue

to command or control the executive officer in the

discharge of those of his duties which involve the exer

cise of his judgment and discretion in the construction

of the law or in determining the existence and effect

of the facts.”

It should be here noted that for defendants to have

approved plaintiff's instant application would have in ef

fect required them to construe the foregoing constitutional

and statutory provisions of this State as being violative

of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States.

Brief of D efendants in Error 29

In the recent case of State ex rel. V. Boyett, 183 Okla.

49, 80 Pac. (2d) 201, the sixth paragraph of the syllabus

is as follows:

“In awarding or denying writs of mandamus,

courts exercise judicial discretion and are governed by

what seems necessary and proper to be done, in the

particular instance, for the attainment of justice, and

in the exercise of such discretion may, in view of the

serious public consequences attendant upon the issu

ance of the writ, refuse the same in a proper case,

though the petitioner would otherwise have a clear

legal right for which mandamus is an appropriate rem

edy.”

In the case of Huddleston V. Dwyer, 145 Fed. (2d)

311, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals, in a case appealed

from the United States District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Oklahoma, held in the eleventh paragraph of the

syllabus, as follows:

“Mandamus cannot be used as a means to compel

county or municipal officers to do that which they

are not authorized to do by the laws of the State.”

r p ♦ ( * 4 - ‘

Pertinent Cases from Other States:

In the case of Sharpless V. Buckles (Kan.), 70 Pac.

886 (referred to on Pages 19 and 20 of plaintiff’s brief),

the second paragraph of the syllabus is as follows:

“The duty of a county canvassing board is minis

terial only. If the election returns made to the county

clerk are genuine and regular, the board has no other

duty to perform than to make the footings and de

clare the result. Mandamus will not lie to require a

county canvassing board to recanvass returns and ex

clude from the county certain votes because cast and

returned under a law that is claimed to be unconstitu

tional. since the determination of such question is not

a duty imposed upon the board, nor within its power.”

30 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

In the case of State ex rel. Hunter V. Winterrowd

(Ind.). 92 N.E. 650 (referred to on Pages 19 and 21 of

plaintiff’s brief), the second paragraph of the syllabus is

as follows:

“The writ of mandamus, under Indiana Statutes,

only issues to compel the performance of an act which

the law enjoins, or of a duty resulting from an office,

trust, or station, in which cases it will issue as a mat

ter of right, in absence of other adequate remedy, if

petitioner shows a clear legal right to the thing de

manded and a duty by respondent to do such thing:

the function of the writ not being to compel disobedi

ence to a law or statute, or litigate its validity.”

In the body of the opinion of said case appears the

following language:

“In the citation of authorities, counsel fail to dis

tinguish between cases in which the respondent asserts

the unconstitutionality of a statute in excuse of non

performance of its requirements, and those in which

the relator seeks to compel performance of an act which

the law prohibits. This court has permitted respon

dents in mandamus proceedings to raise constitutional

questions, although it does not well accord with pub

lic policy to allow ministerial officers to obstruct the

administration of law, by refusing to execute such

statutes as they may deem invalid, and many courts

decline to tolerate such practice. It is quite a different

thing to hold that such an officer must at his peril

disobey the specific commands of a law duly enacted

and promulgated, at the behest of any one who may

be of the opinion .that such law is unconstitutional.

The proper function of mandamus is to enforce obedi

ence of law, and not disobedience, or even to litigate

its validity.”

In the case of Mueller Furnace Co. V. Crockett

(Utah), 227 Pac. 270, the fourth paragraph of the sylla

bus is as follows:

Brief of D efendants in Error 31

“Application for writ commanding secretary of state

to accept and file copy of articles of incorporation,

by-laws, and amendments, and acceptance of pro

visions of Constitution as provided in Comp. Laws

1917, § 945, as amended by Sess. Laws 1923, c. 66,

without payment of fees required by Section 2511,

on ground that latter section is unconstitutional, must

be denied, because it does not appear to be plain duty

of defendant to file papers, in view of Sections 7391,

7392.” .

In the body of the opinion of the above case many

decisions are cited in support of the rule that a person

seeking a writ of mandamus cannot prevail, if to do so

would require the Court to hold a statute, relied upon by

the officer sought to be mandamused, to be unconstitu

tional.

In the case of Whigham V. State (Ohio), 177 N.E.

229, the first and second paragraphs of the syllabus are as

follows:

“ 1. Marshal, seeking mandamus compelling vil

lage officials to pay $3,000 salary under former ordi

nance, could not raise constitutionality of later ordi

nance fixing salary at $10 yearly (Gen. Code, §

12283).

“2. Respecting propriety of mandamus, attacking

constitutionality of ordinance, city officials cannot be

expected to determine validity of ordinances, their

duty being to comply therewith until ordinances are

invalidated.”

In the case of Comley V. Boyle (Conn.), 162 Atl. 26,

the tenth paragraph of the syllabus is as follows:

‘‘On application for mandamus to obtain building

permit, court properly refused to consider constitution

ality of ordinance (17 Sp. Acts 1915, P. 564, § 132

et seq.; P. 565, § 140).

32 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

“Court in such case properly refused to consider

constitutionality of the ordinance, whether such con

clusion be based upon the trial court’s valid exercise

of its discretion in refusing the building permit or

upon the broader ground that it was not the province

of that court to pass upon the question.”

In the case of State V. Police Jury of Vernon Parish

(La.), 3 So. (2d) 186, the third paragraph of the syllabus

is as follows:

“Where statute undertook to divide a parish ward

and an election was held in the new ward at which

it was determined that no licenses for the sale of in

toxicating liquors, wines, and beer should be issued,

mandamus will not tie to compel police jury to issue

license at suit of former licensee on theory that both

statute and election were void.”

While we realize there are certain cases holding that

a person seeking a writ of mandamus can properly challenge

the constitutionality of a state statute relied upon by the

defendant officer, we have been unable to find a single case

applying said rule to a criminal statute of the state that

had never been held unconstitutional by an appellate court

thereof and which hence carried the presumption of con

stitutionality by mandamusing said officer to do an act

which would require him to either directly or indirectly

violate said criminal statute and subject himself to prose

cution by reason thereof.

In this connection it will be noted that in the case

of Missouri ex rel. Gaines V. Canada, supra, the Supreme

Court of the United States did not consider a criminal

statute such as is set forth in 70 O.S. 1941, § 455. In

fact, no criminal statute of Missouri was even mentioned

Brief of D efendants in Error 33

in said case, and the only such statute referred to by the

Missouri court in its decision [113 S.W. (2d) 783] which

was reversed by the United States Supreme Court in the

Gaines case, supra, is quoted in the Missouri decision, as

follows:

“Section 9216, R. S. 1929 (Mo. St.Ann. § 9216,

P. 7087) provides: ‘Separate free schools shall be es

tablished for the education of children of African de

scent; and it shall hereinafter be unlawful for any

colored child to attend any white school, or for any

white child to attend a colored school.’ ”

The above Missouri statute is similar to 70 O. S.

1941, § 457 (abstracted on Page 11 of this brief), but

apparently Missouri does not have a criminal statute such

as is set forth in 70 O. S. 1941, § 455, supra, or in 70

O.S. 1941, § 456 (abstracted on Page 11 of this brief).

In the case of State ex rel. Michael V. Witham et al.

(Tenn. 1942), 165 S.W. (2d) 368, the State’s demurrer

was in part predicated upon the ground

“that the relators were seeking by mandamus to com

pel defendants to violate the criminal statutes of Ten

nessee, viz., Code, Sections 11395-11397, which make

it a misdemeanor for any school, college, or other place

of learning, or any teacher or professor thereof, to

permit white persons and colored persons to attend

the same school or classes.”

The above Tennessee statutes, unlike said Missouri

statute, are similar to 70 O.S. 1941, § § 455 and 456,

but the Tennessee case was decided on other issues in favor

of the State, and hence said statutes were not further re

ferred to therein. Said ground of said demurrer, however,

is supported by the general rule set forth in 34 Am. Jur.,

Page 866, Section 76, as follows:

34 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

“Much less will the writ be awarded to coerce the

performance of acts which are forbidden by statute

or law, or are contrary to public policy, or tend to aid

in an unlawful purpose or transaction.’’

Conclusion As To Proposition 1

Inasmuch as under the principles of law announced

in cases heretofore cited, and since we have been unable to

find a single case, as aforesaid, applying the rule (laid

down in some cases but denied in others) that a person

seeking mandamus can challenge the constitutionality of a

state statute relied upon by the defendant

“* * to a criminal statute of this state that had never

been held unconstitutional by an appellate court there

of and which hence carried the presumption of con

stitutionality by mandamusing said officer to do an

act which would require him to violate said criminal

statute and subject himself to prosecution by reason

thereof” ,

it would appear that the writ of mandamus prayed for

herein should be denied.

The rule above stated is especially applicable in Okla

homa, since a decision of this Court as to the constitu

tionality of a criminal statute of this State is not binding

on our Criminal Court of Appeals in a criminal action

based on said statute, which action is properly appealed

to said court.

Brief of D efendants in Error 35

PROPOSITION 2

Mandamus will not lie to require defendants to

violate the public policy and criminal statutes of Okla

homa by directing defendants to admit plaintiff, a

colored person, to the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma, same being attended only by white persons,

especially since plaintiff has not applied to the State

Regents for Higher Education for them, under authority

of Article 13-A of the Constitution of Oklahoma, to pre

scribe a school of law as a part of the standards of higher

education of Langston University, and as one of the

functions and courses of study thereof, said University

being a State institution of higher education attended

only by colored persons.

The constitutional and statutory provisions of this

State which establish its public policy of segregation of

the white and negro races in educational institutions of

Oklahoma are cited and abstracted in Paragraphs 14 to

21 of defendants’ answer brief herein (pp. 10-12 of this

brief), which public policy is tacitly admitted in Para

graph 7 of the “Agreed Statement of Facts” (Page 15 of

this brief). Certain of said provisions are also cited and dis

cussed in Proposition 1 hereof. Therefore, for sake of

brevity, said constitutional and statutory provisions (other

than certain provisions of 70 O. S. 1941, § § 1451 to

1509, as amended in 1945) will not be quoted here.

However, in connection with the instant proposition,

attention is called to Section 1, the material part of Section

2, and Section 3 of Article 13-A of the Constitution of

the State of Oklahoma (adopted by the people on March

11, 1941), same being as follows:

Ҥ 1. All institutions of higher education sup

ported wholly or in part by direct legislative appro

36 Sipuel v. Board of Regents et al.

priations shall be integral parts of a unified system to

be known as ‘The Oklahoma State System of Higher

Education.’

Ҥ 2. There is hereby established the Oklahoma

State Regents for Higher Education, consisting of nine

(9) members, whose qualifications may be prescribed

by law. * * *

“The Regents shall constitute a co-ordinating board

of control for all State institutions described in Sec

tion 1 hereof, with the following specific powers:

(1) it shall prescribe standards of higher education

applicable to each institution. (2) it shall determine

the functions and courses of study in each of the in

stitutions to conform to the standards prescribed; (3)

it shall grant degrees and other forms of academic

recognition for completion of the prescribed courses

in all of such institutions; (4) it shall recommend to

the State Legislature the budget allocations to each

institution, * *

Ҥ 3. The appropriations made by the Legisla

ture for all such institutions shall be made in con

solidated form without reference to any particular in

stitution and the Board of Regents herein created shall

allocate to each institution according to its needs and

functions.”

Attention is also called to 70 O. S. 1941, § § 1451 to

1509, as amended in 1945, supra, relating to Langston

University, which prior to 1941 was called “The Colored

Agricultural and Normal University.” The material part

of Section 1451, is as follows:

“* *. The exclusive purpose of such school shall be

the instruction of both male and female colored per

sons in the art of teaching, and the various branches

which pertain to a common school education; and in

such higher education as may be deemed advisable by

such board *

Brief of D efendants in Error 37

The Board above referred to, since April 10, 1945,

has been the “Board of Regents for Oklahoma Agricul

tural and Mechanical Colleges.”

It will thus be seen that prior to March 11, 1941

(the date Article 13-A was adopted by the people), the

governing board of Langston University had authority,

if it deemed it “advisable” and sufficient funds were avail

able, to open up a school of law as a part of said university,

said school to be located either at Langston or elsewhere

in this State.

It will also be seen that after March 11, 1941, the

State Regents for Higher Education not only had author

ity under Article 13-A, as stated in Paragraph 23 of de

fendants’ answer (Page 12 of this brief) to

“prescribe a school of law similar to the school of