Blakeney v. Fairfax County School Board Appellants' Appendix

Public Court Documents

March 3, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Blakeney v. Fairfax County School Board Appellants' Appendix, 1964. 953199f2-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/217b183b-ad94-4c0f-bc15-b10faf6b17b1/blakeney-v-fairfax-county-school-board-appellants-appendix. Accessed February 15, 2026.

Copied!

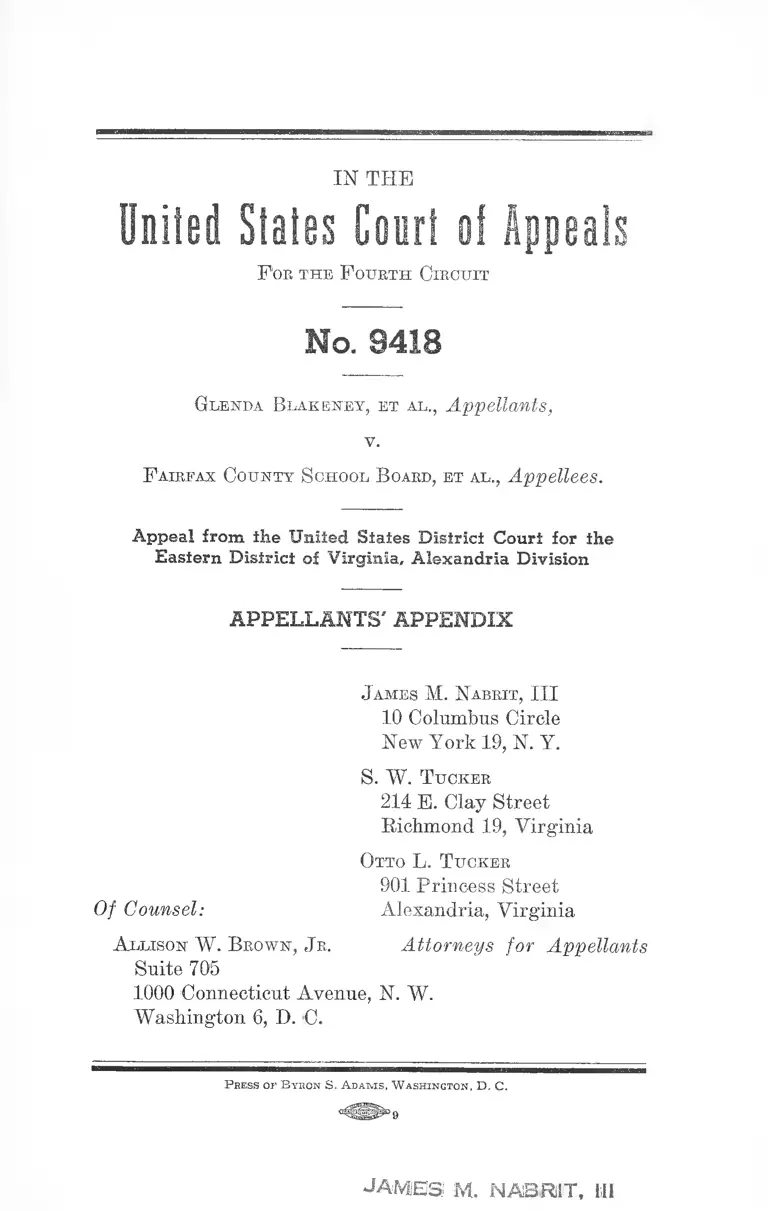

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

F oe the F ourth Circuit

Mo. 9418

Glenda Blakeney, et al., Appellants,

v.

F airfax County School B oard, et al., Appellees.

A ppeal from the U nited S tales D istrict Court for the

E astern D istrict of V irginia, A lexandria Division

APPELLANTS' APPENDIX

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

S. W. T ucker

214 E. Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Of Counsel: Alexandria, Virginia

Allison W. Brown, J r. Attorneys for Appellants

Suite 705

1000 Connecticut Avenue, N. W.

Washington 6, D. C.

P ress or B yro n S. A d a m s , W a sh in g to n , D. C.

J A M E S M . NAlBRilT, 111

INDEX

Page

Relevant docket en tries................................................. 4

Findings of fact and conclusions of law, September 22,

1960 ........................................................................ 4

Decree of the District Court, November 1,1960 ........... 12

Motion for new trial, November 10,1960 ...................... 14

Motion to intervene, June 14, 1963 .............................. 15

Motion in intervention for further interlocutory and

permanent injunctive relief, June 14,1963 ............... 17

Motion for further interlocutory and permanent injunc

tive relief, June 21,1963 ................ ........................ 24

Motion to dismiss motion to intervene, July 3,1963 ---- 34

Motion to dismiss, July 12,1963 .................................... 36

Excerpts from transcript of proceedings, September

12, 1963 .................................................................. 37

Testimony of George H. Pope—-

D irect............................................................... 37

Cross ............................................................... 46

Re-direct ......................................................... 46

Testimony of Eugene L. Newman—

D irect............................................................... 48

Testimony of George IJ. Pope (recalled)—

D irect............................................................... 50

Argument by counsel............................................. 53

Memorandum opinion, March 3, 1964 ............................ 59

Order of the District Court, March 3, 1964 ................... 64

APPELLANTS' APPENDIX

Relevant Docket Entries

Civil Action No. 1967

9-22-60—Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law entered

and filed.

11-1-60—Report of Fairfax County School Board to Court

filed.

11-1-60—Decree entered ordering ‘ ‘ that this action be, and

it is hereby, stricken from the docket.”

11-1-60—J. S. Closing.

11-10-60—Motion for New Trial on part of the issues

received and filed.

11-10-60—Memorandum of Points and Authorities received

and filed.

2-16-61—Notice of Motion for further interlocutory & per

manent injunctive relief received and filed.

2-16-61—Motion for Further Interlocutory & Permanent

Injunctive Relief received and filed.

2-16-61—Affidavit in Support of above received and filed.

2-16-61—Plaintiffs’ Memorandum of Points and Author

ities in support of above received and filed.

2-20-61—Notice received and filed.

4-4-61—Plaintiffs’ Motion for Leave to Withdraw Motion

for Further Interlocutory and Permanent Injunctive

Relief received and filed.

4-4-61—Order granting leave to withdraw the pending

motion for further interlocutory and permanent in

junctive relief entered and filed.

1963

June 14—Motion to intervene as parties plaintiff filed by

Plaintiff.

June 14—Points and authorities in support of Motion for

Intervention filed.

2

June 14—Motion in intervention for further interlocutory

and permanent injunctive relief filed.

June 21—Motion for further interlocutory and permanent

injunctive relied—filed.

June 21—Memorandum of points and authorities in

support of motion for further interlocutory and per

manent injunctive relief—filed.

July 3, ’63—Motion to Dismiss—Motion to Intervene.

Filed.

7-12-63—Pre-Trial—on all motions and merits 9-12-63.

7- 12-63—Motion to dismiss filed by defts.

8- 15-63—Motion to add defendants and amend the plead

ings—filed.

8-15-63—Memorandum of points and authorities in support

of motion to add defendants and amend the pleadings—

filed.

Sept. 12—See Entry 3067.

Mar. 9—Notice of Appeal—filed. $5.00 paid.

Mar. 9—Appeal Bond in the amount of two-hundred and

fifty executed and filed.

Mar. 12—Designation of Contents of Becord on Appeal—

filed.

Civil Action No. 3067

1963

Sept. 12—Motion to intervene as parties plaintiff—filed.

Sept. 12—Memorandum of points and authorities in

support of motion for intervention—filed.

Sept. 12—Motion for further interlocutory and permanent

injunctive relief—filed.

Sept. 12—Plaintiffs’ memorandum of points and author

ities in support of motion for further interlocutory

and permanent injunctive relief—filed.

Sept. 12—Motion to dismiss motion to intervene—filed by

defts.

3

Sept. 12—Motion to dismiss—filed by deft.

Sept. 12—Motion to add defendants and amend pleadings

—filed by plfs.

Sept. 12—Memorandum of points and authorities in sup

port of motion to add defendants and amend the

pleadings—filed.

Sept. 12—Trial Proceedings: This cause came on this day

to be heard on all pending motions, merits and

evidence. (1) Motion to add defendants, & amend the

pleadings. Motion by petitioners to withdraw. Peti

tioners motion to withdraw motion No. 1 granted.

(2) Motion to intervene as parties plaintiff filed

June 14, 1963 came on to be heard. Arguments of

counsel heard. Motion to intervene granted. Evidence

fully heard. Arguments of counsel to the Court heard.

Counsel for defendant announced to the Court that it

would consent to adopting the pleadings as filed

June 14, 1963 and thereafter as a new suit and to be

given a new civil number. The pleadings as filed in

this case shall be adopted as of June 14, 1963 in the

new case. Motion to withdraw prayer for counsel fee.

Motion granted. Court takes this matter under con

sideration.

Mar. 2—Memorandum Opinion entered and filed. Copies

sent to counsel.

Mar. 2—Order entered and filed dismissing the intervening

petition, treated as an original complaint, etc. Copies

sent as directed.

Mar. 9—Notice of Appeal filed—$5.00 paid.

Mar. 9—Appeal Bond in the amount of two-hundred and

fifty dollars executed and filed.

Mar. 12—Designation of Contents of Record on Appeal—

filed.

Mar. 17—Testimony of George H. Pope and Eugene L.

Newman—dated September 12, 1964. Filed.

4

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

AT ALEXANDRIA

Civil 1967

L awrence E dward Blackwell, et al.

v.

F airfax County School B oard, et al.

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law

Thirty-one Negro pupils applied for admission in the

present session to certain of the pnblie schools in Fairfax

County, Virginia, formerly attended only by white

students. The School Board approved five of the applica

tions, one has not been acted upon, and twenty-five were

refused. In this suit these twenty-five applicants ask the

Court to enjoin this refusal by the Board, as based on race

or color, and, so, offensive to the Federal constitution.

That race was the sole reason for declining the applica

tions of fifteen (Nos. 1, 2, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24,

25, 26, 27 and 28) of them is candidly declared by the Board

in its official statement of its action. However, the

differentiation for race was only temporary and was

justified, it explained, as the effect of the first stage of a

plan for the eventual removal of segregation in all the

schools. None of the fifteen came within the scope of this

first step. Additional grounds, such as scholarship and

residence disqualification, barred the other ten applicants.

I. The plan directs the lifting of segregation as a factor

of exclusion in the first and second grades for the session

1960-61, and thereafter in the next higher grades, at the

rate of one grade for each subsequent school year, until

all elementary and secondary grades are removed from

the rule of segregation. All of the 15-group are beyond

the second grade.

Their challenge of this plan is directed at the time

required for its effectuation. Assailing it as laggard, they

point out that the plan would not accomplish the complete

annulment of segregation — its purported aim — for ten

more years. As a consequence, they complain, no Negro

child now in the third or a more advanced grade would

ever be freed of the segregation exclusion. For such a

child the result is to enforce the old practice for many

years to come. This, they also conclude, proves the plan

unacceptable in the law as failing the test of all deliberate

speed.

In justification of the plan, the school authorities testify

to a necessity for gradualness in the conversion to open

schools from a school system distinguishing pupils by race

or color. They observe that Fairfax is still predominantly

a rural county, the people are not accustomed to un

segregated schools, and a sudden change in this usage

would result in an undue and undesirable abrasion of the

feelings of the people. This, they fear, might result in

such popular revulsion to an alteration in the policy of

segregation as to be a substantial obstacle to its entire

removal. These possibilities can be avoided, or at least

minimized, they believe, only by a moderately progressive

transition. They suggest it commence with the school

beginners—to introduce them early to an unsegregated

classroom so in later years they may more readily accept

the presence in their schools of students of another race

or color. Here the Superintendent and Board members

emphasize that children of this age enter the schools with

out prejudgment of the question and would quickly adapt

to the new arrangement. Such a resolution of the problem,

in the witnesses’ judgment, could not be as smoothly

attained in the older-age grades.

6

The good faith of both sides in their differences cannot

be donbted. Each cites judicial precedent. A somewhat

similar plan was approved for Nashville, Tennessee by the

United States Court of Appeals, Sixth Circuit, in Kelley

v. Board of Education, 270 F. 2d 209 (June 17, 1959), cert,

den. 361 U.S. 924. There the white students were 17,000

in number, and the Negroes 10,000, or about 37% of the

total school population. On the other hand, petitioners

rely on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third

Circuit, in its opinions of July 19 and August 29, 1960

in Evans et al. v. Ennis et al., involving the public schools

of Delaware. The number of Negro school children in that

State were 6,813.

But these decisions in truth are not diametrically

opposed. They have a common doctrine—that resolution

of these controversies cannot be reached by the application

of any universal principle, but rather the answer depends

upon local conditions, such as the number of the students,

the structure of the school system, the character of the

community and like personal and objective features. 'While

the Delaware decision is perhaps nearer, the facts in the

two cited cases are so far from comparable with those

present here that, save to declare a general guide of deter

mination, the opinions are not instantly helpful.

In Fairfax County in June, 1960, there were 53,823

pupils (including 272 not precisely graded) in the twelve

grades of the public schools—51,803 White and 2,020 Negro.

With some increase in the total, this ratio between the

races in the school population seemingly will continue for

the current term. The entire school population, say 54,000,

is spread among 94 school buildings. Among these are

six schools exclusively for Negro children—five elementary,

covering grades 1 to 6, and one secondary school caring

for grades 7 through 12.

In the first grade last session there were 307 Negroes

and 5,384 Whites, and in the second grade 228 and 5,596

7

Whites. This numerical relationship extended through the

third, fourth and fifth grades. From the sixth to the

twelfth, inclusive, the ratio is far lower, running about

1 to 30 until the final year when it diminishes to 1 to 40.

These figures disclose that the entire Negro school

attendance in Fairfax is not comparatively large, indeed,

less than 4% of the aggregate.

The proportion of White and Negro pupils in the specific

grades and schools now sought by the petitioners, even

if all of them were admitted as requested, would be as

follows:

Grade White Negro

1 5,384 4

2 5,596 3

3 5,463 5

4 5,146 6

5 5,013 2

6 4,969 2

7 4,986 3

8 4,112 2

9 3,300 1

10 3,001 1

11 2,620 1

12 1,979 1

The four Negroes entering 1st grade would be divided

equally between two schools, Belvedere and Flint Hill; the

three entering the 2nd grade would be divided among

three schools, Celar Lane, Flint Hill and Belvedere; the

five entering the 3rd grade would be divided among Flint

Hill, Cedar Lane and Belvedere; the six entering the 4th

grade would be divided: 2 in Cedar Lane, 1 in Hollin Hall,

1 in Devonshire, and 2 in Belvedere; the two entering the

5th grade would be in Hollin Hall and Devonshire; the two

entering the 6th grade would be in Belvedere and Devon

shire; the three entering the 7th grade would be in Flint

Hill, Parklawn and Lanier; the two entering the 8th grade

would be in Bryant; the one entering the 9th grade would

be in Groveton High School; the one entering the 10th grade

would be in James Madison High School; the one enter

ing the 11th grade would be in James Madison; and the

one entering the 12th grade would be in James Madison.

So that if all of the present applicants were received

into the white schools, only 10 of the 88 “ white” schools

would be affected. None of these would have more than

8 Negro students among the entire student body, the dis

persal being as follows: Belvedere 8, Flint Hill 5; Cedar

Lane 4; Devonshire 4; Hollin Hall 2; Parklawn 1 ; Lanier

1; Bryant 2; Groveton 1 ; and James Madison 3. In the

high schools there would be but 4 Negro students, and

these in three different schools, with no more than 1 in a

single class.

In these circumstances the allowance of the instant

applications would not, and could not, give ground for

public friction. The present conditions do not indicate

a need now to project the bar of the applicants into the

next ten years. Nor does the evidence immediately reveal

any such foreseeable disruption of the teaching staff or

strain on the physical facilities as warrant the delay.

That they are not in the first or second grade is the only

objection interposed to these fifteen students. In every

other way, concededly, they are qualified, and hence they

must be allowed to matriculate now in the schools they

seek.

II. As to the children turned down on additional grounds,

we notice first Nos. 6 and 7. In the amended complaint

they named Flint Hill as their desired school, specifying

the 10th and 11th grades. This request was disallowed

because Flint Hill does not offer those grades. The

evidence shows that originally their applications had been

for James Madison High School. Further amendment of

the complaint will be permitted so as to show Nos. 6 and

9

7 request James Madison. As the Board has not had the

opportunity to pass upon their transfer to James Madison,

the defendants in their answer to the amended complaint

will be directed to state their position as to pupils 6 and

7. At the same time the defendants should report their

action upon the prayer to enter Bryant of the intervenor,

No. 31, who came into the suit on September 8, 1960, too

late for consideration by the Board.

No. 3 also asked to go to Bryant School, 7th grade.

She has been assigned to Luther Jackson School which is

an all-Negro school having grades 7 to 12, inclusive, and

serving as the only high school in the county for Negroes.

This pupil lives within a city block of the school she

seeks, while the assigned school is, by road, more than

13 miles away. The ground of her rejection is “ Because

of academic record it is believed that applicant’s educa

tional needs can best be served in Luther Jackson School” .

For the last session she had a B average, her attendance

was good and her conduct satisfactory.

Pupils Nos. 10, 11 and 13 seek the 3rd and 4th grades in

Cedar Lane. Their assignment is to Louise Archer School.

Cedar Lane is within 1500 feet of their homes, while even

in an air-line Archer is more than 2 miles away. No. 10

failed and was retained one year in each of grades 2 and

3, but last year her scholastic record was better. No. 11

has a somewhat similar record, but has missed considerable

time each year. No. 13 has a comparable record

scholastically, also with substantial absences charged to

her. Both 10 and 11 have been rejected on academic

deficiencies similar to those ascribed supra to No. 3.

No. 13 was excluded on this ground and also on her

behavior record, as well as for want of emotional stability

and social adaptability.

All of these criteria may be valid in apt instances. The

court is not now ruling upon their validity. The point is

10

that they must be applied to both races equally before they

can be used to exclude either a White or Negro student.

Under the practice followed in respect to White children,

the residences of 3, 10, 11 and 13 entitle them to admission

to the schools they now request, but their assignments

have omitted consideration of this factor. Except for

their erroneous school zone assignment, it seems that they

would not have been confronted with the examination, for

it does not appear that White pupils with these same in

adequacies have been declined admittance to Bryant or

Cedar Lane. Consequently, as was likewise held in the

Arlington case decided in this court on September 16,

1960, these tests cannot be held to bar No. 3 from Bryant

and 10, 11 and 13 from Cedar Lane.

Students 8, 9 and 14 reside in the attendance area of

Louise Archer School. They desire to enter Flint Hill

School. They have been unsuccessful because Flint Hill

is overcrowded, while Louise Archer has no congestion.

Moreover, No. 14 lives closer to Louise Archer, and 8 and

9 are not much farther by road from Louise Archer than

from Flint Hill. Incidentally, Nos. 9 and 14 are within the

grades in which the rule of segregation no longer prevails

under the Board’s plan. There is nothing intimating un

fair treatment of these applicants and the action of the

Board has adequate support in the proof.

No. 5 is in the last year of high school at Luther Jackson.

His i*esidence is near James Madison High School and he

desires to be admitted there. Because of the imminence

of his graduation, the school authorities urgently advise

against the transfer. In this they refer to the weakness

of his academic record and note he was sent to the school

psychologist in 1959 for study of his apathy and loss of

interest. A marginal student, they fear a change from a

school familiar with his capacity, his potentialities, his

strength and his weaknesses might cause him to fail of

graduation. This counsel has been given him in the best

11

of faith. It is an entirely unselfish judgment. The court

cannot say that the determination of the School Board is

not without acceptable, as wTell as meritorious, support in

the evidence. There is here no showing that White students

in the same situation would not be retained in the school

of prior attendance. No consideration whatsoever of race

appears in this decision. In so nicely balanced a question,

the court should not permit the judgment of the pupil to

be substituted for that of the school authorities.

The ultimate conclusion of the court is to admit to the

schools respectively requested 19 of the applicants, that is :

Rayfield Barber, Jr. to G-roveton High;

Doris Jeannette Barber to Bryant;

Doris E. Hunter to Cedar Lane;

Bernice Lee to Parklawn;

Solomon Lee to Belvedere;

Reginald Lyles to Hollin Hall;

Ronald Lyles to Hollin Hall;

Carolyn M. Smith to Lanier;

Pierce Smith to Devonshire;

Mary Ellen Smith to Devonshire;

Sharon Smith to Devonshire;

Brenda Summers to Belvedere;

Carlton T. Summers to Belvedere;

Autra Wheeler to Belvedere;

Karen Wheeler to Belvedere;

Linda Monette Barber to Bryant;

Ethel Marie Brooks to Cedar Lane;

Phoebe Ann Brooks to Cedar Lane; and

William Maurice Brooks to Cedar Lane

The remaining 7 applications are not granted. A general

injunction is not called for in this case, because the School

Board and the Superintendent readily recognize their

obligation to avoid discrimination for race or color and

have demonstrated a purpose to adhere to this duty.

12

Let petitioner’s attorneys present an order in accordance

herewith, first submitting it to the opposing attorneys for

consideration as to form.

(Sgd.) Albert V. Bryan

United States District Judge

September 22nd, 1960.

Decree

This cause came on to be heard on the 8th and 11th

days of September, 1960, upon the papers formerly read;

upon the Amended Complaint; upon the Answer to the

Amended Complaint and Exhibits attached thereto; upon

the Motion of Barbara Ann Jackson, infant, and Alfred

Jackson, her father and next friend, to Intervene, to which

motion the defendants consented; upon the Complaint in

Intervention; upon the Motion for leave to correct the

Amended Complaint, to which the defendants consented;

and upon consideration of the evidence and arguments of

counsel for all parties, for the reasons set forth in the

Findings of Facts and Conclusions of Law filed September

22, 1960, it is

Ordered:

1. That the Motion for Intervention of Barbara Ann

Jackson, et al, be granted.

2. That the Motion to Correct the Amended Bill of Com

plaint be granted.

3. That the defendants, their successors in office, agents

and employees be and each of them is hereby restrained

and enjoined from refusing to admit the following plain

tiffs to, or enroll or educate them in, the said schools to

which they have made application, this is :

33

Bayfield Barber, Jr. to Groveton High;

Doris Jeannette Barber to Bryant;

Doris E. Hunter to Cedar Lane;

Bernice Lee to Parklawn;

Solomon Lee to Belvedere;

Beginald Lyles to IJollin Hall;

Ronald Lyles to Hollin Hall;

Carolyn. M. Smith to Lanier;

Pierce Smith to Devonshire;

Mary Ellen Smith to Devonshire;

Sharon Smith to Devonshire;

Brenda Summers to Belvedere;

Carlton T. Summers to Belvedere;

Autra Wheeler to Belvedere;

Karen Wheeler to Belvedere;

Linda Monette Barber to Bryant;

Ethel Marie Brooks to Cedar Lane;

Phoebe Ann Brooks to Cedar Lane; and

William Maurice Brooks to Cedar Lane

4. That the action of the defendants in refusing to admit,

enroll and educate the plaintiffs, Cheryl R. Bigelow in

James Madison High School; Lawrence E. Blackwell,

Donna Blackwell and Warren Carter in Flint Hill School,

be and the same is hereby sustained and the prayers to

the Amended Complaint are denied as to them and their

parents.

5. It appearing that the remaining plaintiffs have been

assigned by the Virginia Pupil Placement Board to the

schools to which they sought admission and have been

admitted and enrolled therein, their cases are now moot

and no action is required by this Court on their prayers

in the Amended Complaint.

6. That the remaining prayers of the Amended Com

plaint be and the same are hereby denied.

14

All matters in issue having been disposed of, and it ap

pearing that all plaintiffs who are entitled to admission into

the schools to which they applied have been admitted and

enrolled in such schools, including those described in para

graph 3 of this Order who were admitted, immediately

after receipt of copies of the Findings of Fact and Con

clusions of Law dated September 22, 1960; it is, therefore,

further

Ordered th a t this action be, and it is hereby, stricken

from the docket.

/s / Albert V. B ryan

United States District Judge

November 1st, 1960.

[Filed 11/10/1960]

Motion for New Trial on Pari of the Issues Pursuant to

Rule 59, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

Plaintiffs, by their attorneys, move the Court to set aside

that portion of the judgment entered in this cause on

November 1, 1960, which ordered the case dismissed and

stricken from the docket, on the ground that this portion

of the judgment is contrary to law, in that the Court is

required by controlling precedents to retain jurisdiction

of the cause until a complete transition from a racially

segregated school system to a racially non-discriminatory

system has been effected. In view of the facts plainly

appearing in this case that the discriminatory system has

not been completely eliminated, and that there has been no

change of the policy of making initial assignments on a

racially segregated basis, and considering that the Court

decided not to issue either a general order prohibiting

discrimination or an order prohibiting the defendants’

policy of making racially segregated initial assignments,

15

it is submitted that the Court should modify its order to

provide that jurisdiction of the cause be retained.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

F rank D. Reeves

473 Florida Ave., N. W.

Washington 1, D. C.

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

[Filed 6/14/63]

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

ALEXANDRIA DIVISION

Civil Action No. 1967

L awrence E dward Blackwell, et al., Plaintiffs,

v.

F airfax County School Board, et al., Defendants,

Glenda Blakeney, infant, by Evelyn Blakeney, her

mother and next friend,

Rte 1, Box 23E,

Alexandria, Virginia,

16

Queen E ster Cox, infant, by Midred Cox, her mother and

next friend,

Bte 1, Box 504,

Alexandria, Virginia,

Calvin Charles J ackson, infant, by Ada Jackson, his

mother and next friend,

P.O. Box 135,

Herndon, Virginia,

B oland W ilson Smith , J r., and Derrick Norman Smith ,

infants, by Boland W. Smith, their father and next

friend,

516 Shreve Street,

Falls Chnrch, Virginia; and

E velyn Blakeney, Mildred Cox, Ada J ackson, and

B oland W. Smith ,

Applicants for Intervention.

Motion to Intervene as Parties Plaintiff

The above-named applicants respectfully move the Court

that they be permitted to intervene as parties plaintiff in

this action and to file their complaint in intervention, upon

the following grounds:

1. The applicants for intervention are members of the

class on behalf of which this action was brought.

2. The applicants have a substantial interest in the

subject matter of the action.

3. They are, and will be bound by, and benefit from, any

judgment, decree or order entered, or to be entered, in this

action.

4. Their motion for further relief and the action in which

they seek to intervene has questions of law and fact in

common.

5. Their intervention will not to any extent delay or

prejudice the further adjudication of the rights of the

17

original parties or other members of the class on behalf of

which this action was brought.

W herefore, applicants pray that this motion and such

other relief as may be determined by this Court in accord

ance with the proposed motion in intervention for further

interlocutory and injunctive relief filed herewith be

granted.

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

S. W. Tucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Applicants

Of Counsel:

Allison W. B rown, J r.

Suite 705

1000 Connecticut Avenue

Washington 6, I), C.

Motion in Intervention for Further Interlocutory and

Permanent Injunctive Relief

The above-named intervenors respectfully move the

Court to grant them further necessary and proper relief

as prayed herein, and as grounds for said motion state:

1. (a) That, as Negroes, they are members of the class

on behalf of which this action was brought to obtain

injunctive relief against the defendants County School

Board of Fairfax County, Virginia, et al., to prohibit the

18

system of racial segregation in the public schools of Fair

fax County, Virginia.

(b) That this cause came on for trial on September 8

and 11, 1960, and thereafter the Court entered its Findings

of Fact and Conclusions of Law on September 22, 1960,

and an order in accordance therewith on November 1, 1960.

(c) That the order of the Court entered on November 1,

1960, provided, among other things, that the cause be dis

missed and struck from the docket. Thereafter, plaintiffs

filed a timely motion pursuant to Rule 59, Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, seeking a rehearing on part of the

issues and modification of the order of November 1, 1960,

to provide that jurisdiction of the cause be retained by

the Court.

(d) That while plaintiffs’ motion for rehearing on part

of the issues and modification of the order was pending,

the Court received for filing in this cause a motion by

plaintiffs for further interlocutory and permanent in

junctive relief by which motion the plaintiffs requested

that the Court restrain the defendants from enforcing in

public schools under their supervision and control any

policy or regulation requiring racial segregation in inter

scholastic sports and other school activities. As a result

of subsequent recision by the defendants of the dis

criminatory policy complained of, the plaintiffs thereafter

moved to withdraw their motion for further injunctive

relief. The plaintiffs’ motion to withdraw was granted

by order of the Court dated April 14, 1961.

2. That notwithstanding the holding and admonitions in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 and 349 U.S.

294, and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, and other controlling

authorities, and notwithstanding the defendants’ obliga

tion, noted by this Court in the Findings of Fact and Con-

19

elusions of Law dated September 22, 1960, “ to avoid

discrimination for race or color,” the defendants, as a

matter of policy, practice, custom or usage, continue to

maintain and operate a bi-racial school system in which

certain schools are designated for Negro children only

and certain schools are designated for white children. As

a matter of routine every child entering the Fairfax County

school system for the first time, if Negro, is initially

assigned to, and placed in, a school designated for Negro

children, and every white child is initially assigned to,

and placed in a school designated for white children.

3. That as a result of the circumstances described in

paragraph 2 hereof, the pattern of segregated education

in Fairfax County continues unaffected except in those

instances in which individual Negroes have sought and

obtained admission to a school designated for white

children.

4. That on or before April 5, 1963, applications were

made to the defendants that the infant intervenors be

transferred from certain schools which none but Negroes

attended, and that they be admitted to, and enrolled in, the

schools to which they would be assigned if it were not

for the fact that they are Negroes. It was thereafter

made known to the parent or guardian of each infant

intervenor that said intervenor’s application had been

denied. An appeal from said determination was there

after made on behalf of each infant intervenor to the

defendant School Board and the Board conducted hearing

at which each intervenor was represented by legal counsel.

Notwithstanding the presentation by counsel of various

arguments supporting the requested transfers, it was

thereafter made known to the parent or guardian of each

infant intervenor that said intervenor’s appeal had been

denied.

20

5. That the schools to which the infant intervenors seek

assignment, and to which they would, as a matter of

routine, be assigned if they were white are as follows:

Glenda Blakeney

Queen Ester Cox

Stratford Landing Elementary

School

Stratford Landing Elementary

School

Calvin Charles Jackson Herndon Elementary School

Roland Wilson Smith, Jr. Pine Spring Elementary School

Herrick Norman Smith Pine Spring Elementary School

6. That the refusal of the defendants to permit the

infant intervenors to be admitted to, and enrolled in, the

schools designated in paragraph 5 hereof is arbitrary,

capricious and discriminatory, the purpose of the defend

ants in limiting transfers of Negro children to schools

which white children attend being to maintain a school or

schools which none but Negroes attend and in which none

but Negroes teach.

7. That but for the deliberate purpose of the defendants

to avoid performance of their duty as mentioned in para

graph 2 hereof, the intervenors would have no need to

apply for attendance at the schools specified. But for

the fact that they are Negroes, the intervenors would have

been assigned as a matter of routine to the schools which

they seek to attend.

8. That for reasons stated in paragraph 2 through 7

hereof, and for reasons apparent upon the face of the

Virginia Statute pertaining to Local Enrollment or Place

ment of Pupils (Sections 22-232.18 through 22-232.31 of

the Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended), the said statute

does not provide an adequate remedy for the relief the

intervenors seek.

21

9. That the refusal of the defendants to grant the

requested assignments, viewed in the light of the refusal

of the defendants to bring about the elimination of racial

segregation in the public school system of Fairfax County

constitutes a denial to the intervenors, and others similarly

situated and affected, of due process of law and the equal

protection of the laws secured by the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution, as well as the rights secured by

Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981.

10. That the intervenors, and others similarly situated

and affected, are suffering irreparable injury and are

threatened with irreparable injury in the future by reason

of the policy, practice, custom, usage and actions herein

complained of. They have no plain, adequate or complete

remedy to redress the wrongs and illegal acts herein com

plained of, other than by this Court’s granting injunctive

relief. Any other remedy to which the intervenors and

others similarly situated could be remitted would be

attended by such uncertainties and delays as would deny

substantial relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits, and

would cause further irreparable injury and occasion

damage, vexation and inconveniences.

W herefore, intervenors respectfully pray that the Court

enter an interlocutory and permanent injunction:

(a) Restraining and enjoining the defendants, and each

of them, their successors in office, and their agents and

employees, from refusing to admit, enroll and educate

forthwith the infant intervenors, and other children

similarly situated, in the designated schools for which they

have applied, or may apply, or in such other schools under

the jurisdiction and control of the defendants for which

said children are otherwise qualified and eligible for

admission, enrollment and education, on the basis of the

same standards and criteria applied in determining the

22

admission of all children in said schools, excluding any

and all consideration of their race or color.

(b) Restraining and enjoining the defendants from

making initial assignments of Negro children to schools

which none hut Negroes attend.

Intervenors pray that this Court allow them their costs

herein and reasonable attorneys’ fees, and grant such

other and further relief as may he just and equitable in

the premises.

/ s / .........................................

Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

S. W. Tucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Intervenors

Of Counsel:

Allison W. Brown, J r.

Suite 705

1000 Connecticut Avenue

Washington 6, D. C.

23

Affidavit

State of Virginia, ) .

City of Alexandria. 3

Otto L. Tucker, being duly sworn according to law, de

poses and says as follows:

1. That he, in association with others, is attorney for the

intervenors in the above-entitled cause.

2. That he is informed and believes that all of the allega

tions of fact set forth in the motion in intervention for fur

ther interlocutory and permanent relief herein are true.

/ s / Otto L. T ucker

Subscribed and sworn to before me

this day of 1963.

M ......................................................

Notary Public

24

[Filed 6/21/63]

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

ALEXANDRIA DIVISION

Civil Action No. 1967

L awrence E dward Blackwell, P hyllis R osetta Black-

well, and Donna Blackwell, infants, by Lillian S.

Blackwell, their mother and next friend,

R.F.D. #2, Box 77, Vienna, Virginia,

R ayfield Barber, J r., Doris J eanette Barber, and L inda

Monette Barber, infants, by Beatrice S. Barber, their

mother and next friend,

610 Emmitt Drive, Alexandria, Virginia,

Bernice Lee and Solomon L ee, infants, by Constance Lee,

their mother and next friend,

4202 First Street, Alexandria, Virginia,

R eginald W. L yles and Ronald L. L yles, infants, by Major

W. Lyles, their father and next friend,

423 E. Boulevard Drive, Alexandria, Virginia,

Mary E llen Smith , P ierce A. Smith , and Sharon Smith ,

infants, by William P. Smith, their father and next

friend,

1553 Lee Highway, Falls Church, Virginia

A utra W heeler, and K aren A. W heeler, infants, by Ethel

Wheeler, their mother and next friend,

Route 4, Box 604, Annandale, Virginia,

W arren Brent Carter, infant, by Wyndell W. Carter, his

father and next friend,

356 Lawyer Road, Box 151, Vienna, Virginia,

E thel Marie Brooks, W illiam Maurice Brooks, and

P hoebe Ann Brooks, infants, by Ethel Brooks, their

mother and next friend,

Route 5, Box 301, Vienna, Virginia,

25

Doris E. H unter, infant, by Evelyn Hunter, her mother

and next friend,

Rte 5, Box 301, Vienna, Virginia,

Brenda E. Summers and Carlton T. Summers, infants, by

Lillian J. Summers, their mother and next friend,

Rte 4, Box 595A, Annandale, Virginia,

Barbara Ann J ackson, infant, by Alfred Jackson, her

father and next friend,

872B Quander Road, Alexandria, Virginia; and

L illian S. Blackwell, Beatrice S. B arber, Constance L ee,

Major W. L yles, W illiam P. Smith , E thel W heeler,

W yndell W. Carter, E thel Brooks, E velyn H unter,

L illian J. Summers and Alfred J ackson,

Plaintiffs,

v.

F airfax County School Board, a body corporate, Fairfax,

Virginia, and

E arl C. F underburk, Division Superintendent, Fairfax

County Public Schools, Fairfax, Virginia,

Defendants.

Motion for Further Interlocutory and

Permanent Injunctive Relief

The above-named plaintiffs respectfully move the Court

to grant them and others of the class they represent fur

ther necessary and proper relief as prayed herein, and as

grounds for said motion state:

1. (a) That they are among the group of Negro plain

tiffs in this class action which they brought on behalf of

themselves and others similarly situated to obtain injunc

tive relief against the defendants County School Board of

Fairfax County, Virginia, et al., to prohibit the system of

2 6

racial segregation in the public schools of Fairfax County,

Virginia.

(b) That the cause came on for trial on September 8 and

11, 1960, and thereafter the Court entered its Findings of

Fact and Conclusions of Law on September 22, 1960, and

an order in accordance therewith on November 1, 1960.

(c) That the order of the Court entered on November 1,

1960, provided, among other things that the cause be dis

missed and struck from the docket. Thereafter, plaintiffs

filed a timely motion pursuant to Rule 59, of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, seeking a rehearing on part of

the issues and modification of the order of November 1,

1960, to provide that jurisdiction of the cause be retained

by the Court.

(d) That while plaintiffs’ motion for rehearing on part

of the issues and modification of the order was pending,

the Court received for filing in this cause a motion by plain

tiffs for further interlocutory and permanent injunctive

relief by which motion the plaintiffs requested that the

Court restrain the defendants from enforcing in public

schools under their supervision and control any policy or

regulation requiring racial segregation in interscholastic

sports or other school activities. As a result of subsequent

rescision by the defendants of the discriminatory policy

complained of, the plaintiffs thereafter moved to withdraw

their motion for further injunctive relief. The plaintiffs’

motion to withdraw was granted by order of the Court

dated April 14, 1961.

2. That notwithstanding the holding and admonitions in

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 and 349 U.S.

294, and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, and other controlling

authorities, and notwithstanding the defendants’ obliga

tion, noted by this Court in its Findings of Fact and Con

clusions of Law dated September 22, 1960, “ to avoid dis

crimination for race or color,” the defendants, as a matter

27

of policy, practice, custom or usage, continue to maintain

and operate a bi-racial school system in which certain

schools are designated for Negro children only and are

staffed by Negro principals, teachers and administrative

personnel, and certain schools are designated for white

children and are staffed by white principals, teachers and

administrative personnel. A dual set of school zone lines

is also maintained. These lines are based solely upon race

and color. One set of lines relates to the attendance areas

for the Negro schools; these lines overlap the lines bound

ing attendance areas for the white schools.

3. That the pattern of segregated education in Fairfax

County continues unaffected except in those instances in

which individual Negroes have sought and obtained admis

sion to a school designated for white students.

4. That as a matter of routine, every white child enter

ing the Fairfax County school system for the first time is

initially assigned to, and placed in, a school designated for

white children. Every white child, upon promotion from

the highest grade in elementary school, is routinely as

signed to an intermediate school designated for white

children, and upon graduation from intermediate school

every white child is routinely assigned to a high school

designated as one for the education of white children.

5. That as a matter of routine, every Negro child enter

ing the Fairfax County school system for the first time is

initially assigned to, and placed in, a school which none but

Negroes attend, and upon promotion from the highest

grade in elementary school, such Negro child is routinely

assigned to the Luther Jackson school, an all-Negro com

bined intermediate and high school located in Fairfax

County which is operated by, and under the supervision

and control of, the defendants.

6. That to avoid the racially discriminatory result of the

practice described in the two paragraphs next preceding,

28

a Negro child’s parent, guardian or other person having

custody of the child is required to make application for

transfer of the child from the school which none but Ne

groes attend to a school specifically named. Such assign

ment application must be made on a specially prepared

form which can only be obtained upon specific request at

the administrative offices of the defendant School Board,

Fairfax, Virginia. This special application form, a copy

of which is attached hereto as Exhibit “ A”, requires in

formation to be supplied concerning Negro children, such

as the reason why the specific assignment is sought, the

child’s aptitudes, its handicaps or disabilities, as well as

other matters. Since such information is not required

from white children assigned to the same school to which

the Negro child seeks assignment, the application form is

in itself inherently discriminatory.

(b) That the application to transfer a Negro child out

of an all-Negro school must be filed at a particular time of

the year—the deadline, except in the case of new residents

in the County and certain others, being April 5 preceding

the school year to which the placement requested is to be

applicable. Neither this unnecessarily early deadline nor

the procedure for transferring out of Negro schools has

been specially publicized by the defendants. Each year

there are Negro families that apply, after the April 5 dead

line, to transfer their children out of the all-Negro schools,

but the defendants, as a matter of course, deny such ap

plications.

(c) That in each of the three years that the foregoing

transfer procedure has been in effect in Fairfax County,

certain of the applications on behalf of Negro children to

transfer from all-Negro schools have been initially turned

down, with the result that the parent, guardian or other

person having custody of such child, who seeks reversal of

such initial determination, has been required to pursue an

appeal procedure as set forth in Section 22-232.21, Code of

Virginia of 1950, as amended. The nature of this appeal

29

procedure is such, that the Negro families pursuing this

remedy have in virtually every instance felt the need to

engage the services of legal counsel to represent their in

terests before the defendant School Board.

7. That the assignment and transfer procedures de

scribed in paragraph 6 and its subparagraphs do not sat

isfy the Due Process and Equal Protection requirements

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, for by

reason of the existing segregation pattern it is Negro

children, primarily, who seek transfers and they are thus

subjected to administrative burdens and inconveniences

not experienced by white children.

8. That the plaintiffs and members of their class are

injured by the defendants ’ policy, practice, custom or usage

of assigning principals, teachers and administrative per

sonnel on the basis of the race or color of the person as

signed, and that such policy, practice, custom or usage

violates the right of plaintiffs and members of their class,

arising under the Due Process and Equal Protection clauses

of the Constitution, with respect to the public school system

of which they are a part to have that system operated on

a non-racial basis.

9. That the defendants ’ policy, practice, custom or usage

of continuing to operate a bi-racial school system consti

tutes a denial to the plaintiffs and members of their class

of due process of law and the equal protection of the laws

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution,

as well as the rights secured by Title 42, United States

Code, Section 1981.

10. That the plaintiffs and members of their class are

suffering irreparable injury and are threatened with ir

reparable injury in the future by reason of the policy,

practice, custom, usage and actions herein complained of.

They have no plain, adequate or complete remedy to re

dress the wrongs and illegal acts herein complained of,

other than by this Court’s granting injunctive relief. Any

30

other remedy to which the plaintiffs and members of their

class could he remitted would he attended by such uncer

tainties and delays as would deny substantial relief, would

involve a multiplicity of suits, and would cause further

irreparable injury and occasion damage, vexation and in

conveniences.

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray that this Court

enter an interlocutory and permanent injunction:

(a) Restraining and enjoining the defendants, and each

of them, their successors in office, and their agents and em

ployees (1 ) from any and all action that regulates or af

fects, on the basis of race or color, the initial assignment,

the placement, the transfer, the admission, the enrollment

or the education of any child to and in any public school

under the defendants’ supervision and control; (2) from

using any separate racial attendance area maps or zones

or their equivalent in determining the placement of chil

dren in schools; (3) from requiring any applicants for

transfer from Negro to white schools to submit to any

futile, burdensome, or discriminatory administrative pro

cedures in order to obtain such transfers, including (but

not limited to) the use of any criteria or standards for de

termining such requests which are not generally and uni

formly used in assigning all pupils, as well as the require

ment of administrative hearings or other procedures not

uniformly applied in assigning pupils; (4) from employing

or assigning principals, teachers or other school personnel

on the basis of the race or color of the person employed or

assigned, or on the basis of the race or color of the pupils

attending the school to which such person is assigned.

(b) Restraining and enjoining the defendants, and each

of them, their successors in office, and their agents and em

ployees, from operating a hi-racial school system.

Plaintiffs pray that this Court allow them their costs

herein and reasonable attorneys’ fees, and grant such other

31

and further relief as may be just and equitable in the

premises.

/ s / Otto L. T ucker

901 Princess Street

Alexandria, Virginia

Of Counsel:

S. W. T ucker

214 East Clay Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

J ames E. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, N. Y.

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

Aluisox W. Browx, J r.

Suite 705

1000 Connecticut Avenue

Washington 6, D. C.

Affidavit

State of Virginia, } .

City of Alexandria. )

Otto L. Tucker, being duly sworn according to law, de

poses and says as follows:

1. That he, in association with others, is attorney for the

plaintiffs in the above-entitled cause.

2. That he is informed and believes that all of the allega

tions of fact set forth in the motion for further inter

locutory and permanent relief herein are true.

/ s / Otto L. Tucker

Subscribed and sworn to before me

this 21st day June 1963.

N ........................................

Notary Public

32

Exhibit "A"

PUPIL PLACEMENT APPLICATION

I, the undersigned as .........................................................

(Insert relation, such as parent, legal guardian, etc.)

of the child named below, request that the child named in

this application be placed in the ....................grade of the

....................... School, ............................... County, City,

or Town for th e .................................. school session.

Pull Name of Child: ...........................................................

First Middle Last

Address: ...............................................................................

(Street or R.F.D. Number)

Post office .............................................................................

S e x :.........Race: ...........Year and Date of Birth* : ...........

Place of Birth: ....................................................................

Total number of years child has attended school (including

present year): ......................................................................

Name and address of school attended by child previous

year: .................................................................... ...............

...................................................... Grade: .........................

Name and address of school child is attending this year:

...................................................... Grade: .........................

Physical or mental handicaps or disabilities: .....................

Reason(s) for this request:................................................

Particular aptitudes:

Name and location of school or schools in Virginia in which

other children for whom I am legally responsible are en

rolled : .................................................................................

33

The foregoing is certified on oath or affirmation to he

true and complete.

Signed: .......................................................

(Name of Parent, Guardian or Custodian)

Street or P.O. A ddress..............................

City, Town, and S ta te ................................

Date: ..............................

*A birth certificate or photostatic copy thereof shall be

attached to this application if the pupil:

(1) Has moved to Virginia from another state,

(2) has moved from another county or City within the

State,

(3) has not previously been enrolled in any school

(those entering first grade).

INFORMATION REQUESTED BY THE

LOCAL SCHOOL BOARD

Principal’s Recommendation. (Optional at the discretion

of the local school board)

In my judgement, the transfer and/or placement o f .........

.................................. to (in) the .....................................

(name of child)

School would be ..................................... in his (her) best

Would not b e ................................

educational interest.

Date: .....................

Name of School . . .

Signed:

Principal

School Address

34

Action taken by the school board or its agent and reason(s)

therefor

(Date on which official placement is made)

School Board of

(County or City)

By:

Motion io Dismiss Motion to Intervene

Without admitting the right of the applicants to inter

vene in this cause, the defendant, Fairfax County School

Board, moves the Court to dismiss the motion to intervene

filed by Glenda Blakeney, et al, on the following grounds:

That at a meeting of the Fairfax County School Board

held on July 1, 1963, a resolution was adopted rescinding

the action of the Board previously taken with respect to the

applications of Glenda Blackeney, et al, and at the same

time granting the applications of the following named

children to attend the schools indicated:

Glenda Blakeney—Stratford Landing Elementary School

Queen Esther Cox—Stratford Landing Elementary

School

Calvin Charles Jackson—Herndon Elementary School

Roland Wilson Smith, Jr.-—Pine Spring Elementary

School

Derrick Norman Smith—Pine Spring Elementary School

A copy of said resolution is hereto attached and prayed

to be read as a part hereof.

J ames K eith

Attorney for Defendant

200 South Payne Street

Fairfax, Virginia

35

OFFICE OF

FAIRFAX COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD

400 Jones Street

FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA

E. C. FUNDERBURK, DIVISION SUPERINTENDENT

W. CLEMENT JACOBS, CLERK

July 2, 1963

Mr. James Keith

Pickett, Keith & Mackall

200 South Payne Street

Fairfax, Virginia

Dear Mr. Keith:

Following is action of the Fairfax County School Board

at its meeting of July 1, 1963, with respect to pupil

placements:

“ Mr. Clark moved that the Board publicly reaffirm its

action of June 24, 1963, by which it rescinded its May 20

denial of placement appeals on behalf of five negro students,

on advice of its attorney that the School Board was in an

indefensible position in the suit filed by the appellants in

protest of original assignments, thereby permitting attend

ance of these five applicants at schools as follows, in lieu

of previous assignments to negro schools:

Glenda Blakeney—Stratford Landing Elem.

Queen Ester Cox— Stratford Landing Elem.

Roland Wilson Smith, Jr.—Pine Spring Elem.

Derrick Norman Smith—Pine Spring Elem.

Calvin Charles Jackson—Herndon Elem.

“ Mrs. Lahr seconded the motion and it carried by vote of

three in favor (Mrs. Gertwagen, Mr. Clark and Mrs. Lahr)

and two against (Messrs. Hoofnagle and Futch), the Chair

man abstaining from voting.”

X hereby certify that the foregoing is a true and accurate

excerpt from the minutes of a meeting of the Fairfax

36

County School Board on July 1, 1963, in its Administration

Building.

W. Clement J acobs

W. Clement Jacobs, Clerk, County

School Board of Fairfax County,

st Virginia

Motion to Dismiss

The defendants move the Court as follows:

1) To dismiss the motion for further interlocutory and

permanent injunctive relief filed by the attorneys for the

plaintiffs on July 21, 1963, because there has been entered

in this cause a final order or decree which ordered that

“ this action be . . . stricken from the docket,” which order

or decree was entered on November 1,1960, and which order

has not been amended in any form or fashion by the Court.

2) To dismiss said motion on the ground that this Court

is without jurisdiction to hear the same because a final

order was entered in this cause on November 1, 1960.

3) To dismiss said motion because it constitutes an

amendment of plaintiffs ’ pleadings and is not done by leave

of Court as required by Rule 15.

4) To dismiss said motion because it undertakes to raise

issues already raised in the former proceedings in this cause

and already decided by the order or decree of November

1, 1960.

J ames K eith

James Keith

Attorney for Defendants

200 South Payne Street

Fairfax, Virginia

37

Excerpts from Transcript of Proceedings

2 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

ALEXANDRIA DIVISION

Civil Action No. 3067

Glenda Blakeney, infant, et al., Plaintiff,

v.

F airfax County School Board, et al., Defendants.

Before United States District Judge

H on. Oren R. Lewis

September 12, 1963

Appearances:

Otto L. Tucker, E sq.

S. W. Tucker, E sq., and

Allison W. Brown, J r., E sq.,

For the Plaintiff.

J ames K eith , E sq.,

For the Defendants.

3 George H. Pope

called as a witness in behalf of the plaintiff, and having

first been duly sworn, was examined and testified as fol

lows :

Direct Examination

By Mr. S. W. Tucker:

Q. Will you state your name and official position? A. I

am George H. Pope. I am Associate Superintendent of

the schools in Fairfax County.

* * * * * * * * * *

5 Q. Will you tell us how many schools remain in

Fairfax County, speaking about public schools in

the school system— A. Yes, sir.

Q. —identifying them by name, if you can, which are

peculiar in that none but negroes attend those schools and

none but negroes may teach in those schools, in other

words, what I am trying to find out is how many and

what are the negro schools in Fairfax County. A. Oh,

there are presently 7 schools attended entirely by pupils

of the colored race.

Q. And, I believe, one of those is the Luther Jackson

School? A. That is true.

Q. That is a combination school, running all grades from

1 through 12? A. No, sir. That is a combination junior

and senior high school, with two classes for retarded chil

dren assigned there. They do not run the gamut of

6 grades 1 through 12.

Q. And the other six schools that you mentioned

in this category are elementary schools, then? A. That is

true.

Q. I want to ask you, with reference to the Luther

Jackson Junior and Senior High School, if you may call it

that—■ A. Officially, it is an Intermediate and Senior High

School. We use the word, intermediate school, rather than

a junior high school, for grades 7 and 8.

7 Q. All right. So that, as far as the County

Schools are concerned, the only elementary schools which

feed the Jackson Intermediate and Senior School are these

six schools which we have identified as being peculiar in

that none but negroses attend or teach there? A. That has

been the case up to this point.

Q. Now, as to the children who attend these seven

schools which we are identifying now as negro schools,

do they ride in separate school buses from other children

in the county? A. Well, if your—

Q. What I want to know is whether these children who

attend these all negro schools ride special buses that serve

those schools only, or whether they ride buses with other

children in the county. A. In the regular term, they ride

39

buses that serve those schools only because that is the

way we assign all of our buses, to specific schools.

Q. All right. So that it results, then, that these

8 six elementary schools and the Luther Jackson Inter

mediate and Senior School and the buses that serve

those schools are used and operated by negroes? A. They

are attended—

Q. Excuse me. A. —by negro pupils.

Q. Exclusively? A. They are staffed by negro staffs.

Q. Now, can you tell us, approximately, how many chil

dren attend those seven schools? A. If you bear with me

just a moment, sir.

Q. If you have had the figures for the schools separate,

we would probably rather have it that way. A. 2101 of

them. 2101 pupils attending those schools.

Q. Approximately how many pupils do you have in the

entire school system? A. 80,558. Of the number that I

gave you of 2101, that does not include all negro pupils in

the county. Maybe your question was, attending those

seven schools?

Q. That is correct. A. I have 428 more.

Q. There are 428 negro children attending schools with

white children? A. Yes, sir.

# * # # # * * # * *

9 Q. Now, with reference to your school system,

generally, and I am speaking now with reference to

white children, what is your system by which a child knows

where he attends school? A. Well, we have general attend

ance areas, not too well defined, in our county because of

our tremendous growth, recognizing that we have over

7600 more pupils now than we had when the schools closed

last June, so, in that situation, it is impossible to define for

one and for all time school attendance areas because they

shift even from, certainly from year to year and some

times from month to month because of opening of new sub

divisions and relocation of people and new persons moving

into areas where before there were no residents of school

40

age. So we have a general consensus, general understand

ing, of the service area of each of our schools consistent

with the capacity of each of the schools. And it doesn’t,

necessarily, mean that it always serves all pupils nearest

to it because we have one school, say, of 25 class rooms

and another of 10. Obviously, the 25 class room school can

reach farther out from it with its service area than can the

small one.

Q. So, even though the lines may shift from time to time,

at any given time, it is possible to define a geo-

10 graphic area and relate that area to each of your

elementary schools? A. For practical purposes, that

is true.

Q. The same thing would be true with reference to your

intermediate schools? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And the same thing would be true with reference to

your senior high schools? A. Yes, sir. I think, at that

point, there is probably a little more information than just

yes or no—

Q. All right. A. -—because I think it is related, if you

please, to a statement that I just made, for practical pur

poses this is true. These are not completely and totally

and perfectly binding. We do have a great deal of latitude

on the part of individuals within the framework of law

to move from one school to another, as they have done,

even with these 428 colored pupils I referred to a moment

ago.

Q. But, as a general rule, with the exceptions that you

have mentioned allowed for, a white child’s school attend

ance is determined by the location of his home? A. Yes,

sir.

Q. All right. Now, as to these six elementary schools

that we have identified as negro schools, do they have

attendance areas? A. In part, with particular ref-

11 erence where there are concentrations of pupils

around a school. There are a few of these six ele

mentary schools that we have described as serving all

colored pupils that exist right in a community that is pre-

41

dominantly negro community. That particular community

has not been zoned into any other type of school.

Q. But, that particular community, so far as the land

area is concerned, would be contained within one of the

areas for the white schools, would it not? A. No. That is

what I just said. Where there is this defined negro com

munity with a school existing in it, we have not zoned that

in. I don’t think, anywhere, would you find that that has

been zoned into one of the white elementary communities

that you were describing earlier.

Q. In other words, if we had an elementary school map

showing the zones of each school, you are saying that the

negro community would be isolated from the zones for the

white elementary schools? A. I said that part of it right

around the school, recognizing that there are negro pupils

who live outside of those communities, and they are not

zoned on any map that I know anything about into the

school community of that particular school.

Q. All right. Now, as to those negro pupils who live

outside of those specific communities, are they, initially,

assigned to the school serving the zone in which they

12 live, and I mean by that the school which white

children attend which serves the zone in which they

live? A. Are initially assigned?

Q. Initially assigned to that school or initially assigned

to the nearest negro school. A. The initial assignment you

are referring to, the first time they come to school, two

things can happen there. It depends altogether where they

seek admission or where they come to register for a school.

Now, I am talking about initial assignment, rather than

transfers. Now, we have just—I was going to say dozens—

I wouldn’t be sure that that would be just right, but numer

ous instances where colored pupils, negro pupils living

in an area that is served predominantly by white schools

have gone directly to white schools to register and attend

there now without ever having been in a negro school, with

out ever having been placed in a negro school to apply out.

Q. "Well, under your regulations—

42

The Court: Just a minute. So I have it perfectly correct,

a colored eligible student living in Fairfax County in an

area which would be within, what we will say, at least

tentative physical boundaries for white school A, as it is

called, and he goes to school for the first time, do I under

stand that if he, through his parents, of course, goes to

the school nearest his home, which happens to be a

13 white school, and he applies for admission, that he

is admitted without question?

The Witness: He is admitted there if that is his desire

in terms now with the assignment law that we are follow

ing in Virginia at the moment. That is true.

The Court: What do you mean, “ within terms of the

assignment law ’ ’ that you are applying, so I understand it ?

The Witness: We are operating under a local assign

ment law at the moment in Fairfax County, as opposed to

the—

The Court: Pupil Placement Law?

The Witness: Pupil Placement Law.

28 Q. Let’s take a child in the 3rd or 4th grade,

a negro child, who is attending one of these negro

schools. The child’s mother wants the child to attend the

school where his white neighbor attends. A. The school

that is near him?

Q. Whichever one his white next-door neighbor attends.

A. Talking about Point No. 2?

29 Q. Point No. 2, yes, sir. I want to know what

are the criteria for that transfer? A. He would

automatically go into it on his request, unless he was going

into a program of special education for retarded which

doesn’t exist there. You said, normal.

31 Q. Am I understanding, from what you are saying

now, that these rules, apparently, promulgated by the

32 School Board on March 19, 1963, resulted from the

applications of these interveners? A. And others

43

like—Simply because it was brought before the Board.

All of these applications brought before the Board two

questions. One was, and this is a transfer business rather

than initial assignment; they were requesting transfer in

some instances to a desegregated school farther from their

homes, their place of residence, and that was taken care of

in Item 2—I am sorry—requesting desegregation, request

ing assignment to desegregated schools farther from their

place of residence. That was taken care of in Item No.

3. Others requested assignment to desegregated schools

closer to place of residence than the school they had been

attending. That is taken care of in Item 2 of this plan.

# # # # # # # # # *

37 Q. That is that the negro child is in the negro

school, he is fed into Luther Jackson? A. Unless

he requests—

Q. Unless he requests? A. —differently. If he lets it

be known that he wants to do something different, then he

comes under No. 2, you see.

Q. And he is fed into Luther Jackson regardless as to

what part of the county he lives in? A. Unless he ex

presses a desire differently, and then it comes under No. 2.

Q. But with every white child who goes to the intermedi

ate or senior high school, he goes according to the zone in

which he lives? A. Yes, sir, generally.

# # # # # * * # # *

40 The Court: Mr. Tucker, let’s see if we can get

at it specifically.

If I am a colored child and I moved into Fairfax this

September, I went to school for the first time and I

lived in what we will call a comingled section, that is not a

solid colored community adjacent to an elementary school,

and I wanted to go to school, could I enroll at the school

nearest me if it was desegregated, as distinguished from

the colored, and did I go in automatically this year?

The Witness: The answer is yes, sir,—

44

The Court: All right.

The Witness: —because our Point No. 2—

The Court: If I am in school and had been in elementary

school for four years, already been there for four years,

and I lived next door to this boy who just came in and en

rolled in this integrated school in a comingled district, as

I call it, and I want to go to that school, can I go and

register and just go in, or do I have to be transferred?

The Witness: You will have to be transferred because

the state law, the Pupil Placement Law under which we

operate, calls for a transfer and sets forth—

41 The Court: But the transfer is automatic?

The Witness: Well, there are certain legal stip

ulations in the law.

The Court: Other than the standard procedure of filing

an application?

The Witness: Yes. If he meets all the other require

ments, Point No. 2—

The Court: Then becomes automatic. All right.

The Witness: Point No. 2 applies there.

By Mr. Tucker:

Q. Let me see how automatic this transfer is. I suppose

I have to have a form to make the application on ? A. That

is the easiest way. The Pupil Placement Law we operate

under says on forms supplied by the State Board of Edu

cation or approved by the State Board of Education.

Q. How do I get the form? A. It can be obtained from

our system.

Q. I have to come to the School Board’s office to get it?

A. You don’t have to come. You can telephone. You

can mail, or you can come, whichever.

Q. The only place I can get such a form is at the School

Board office? A. Basically, yes, sir.

Q. When I fill out the form, what information is