Shipp v TN Department of Employment Security Respondents in Opposition

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1978

10 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shipp v TN Department of Employment Security Respondents in Opposition, 1978. c081603c-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2181d95a-a930-41a1-a14c-9a5c04911d87/shipp-v-tn-department-of-employment-security-respondents-in-opposition. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

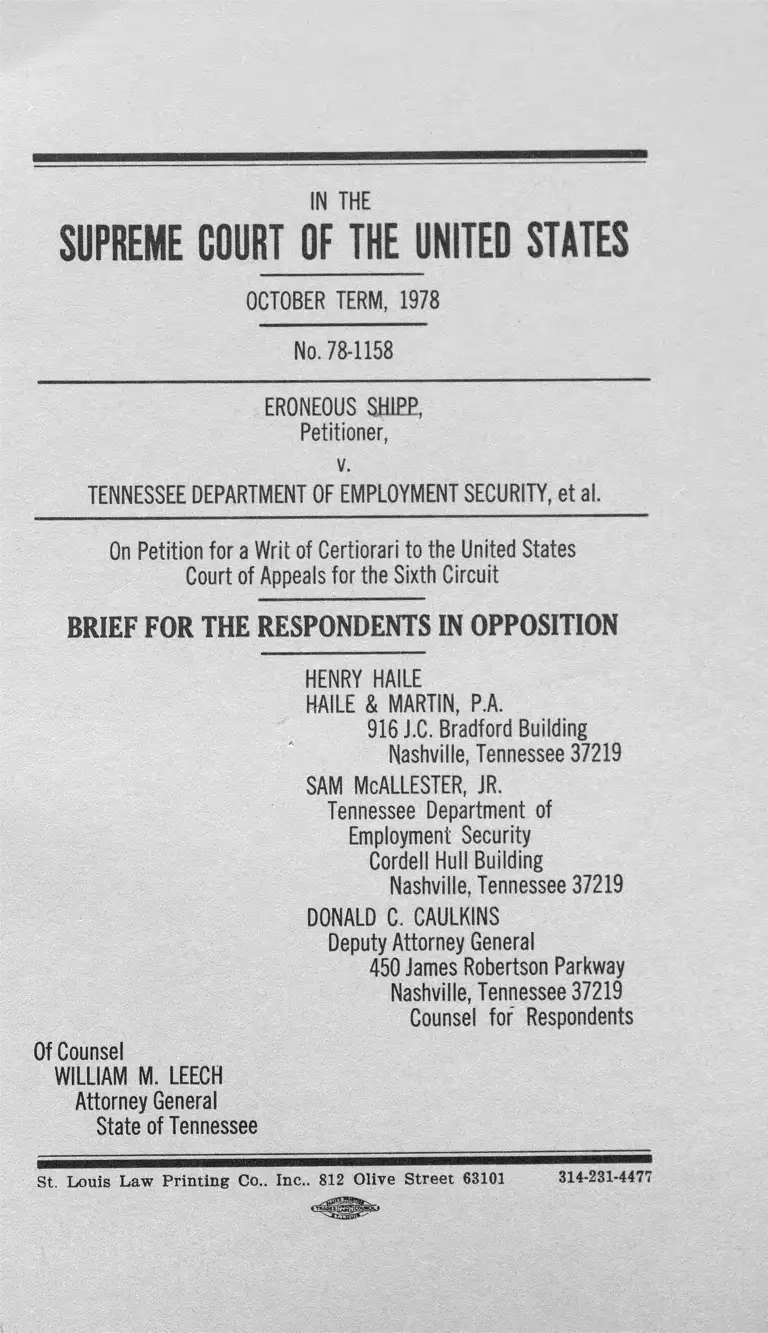

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-1158

ERONEOUS SHIPP,

Petitioner,

v.

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et al.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

Of Counsel

WILLIAM M. LEECH

HENRY HAILE

HAILE & MARTIN, P.A.

916 J.C. Bradford Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

SAM McALLESTER, JR.

Tennessee Department of

Employment Security

Cordell Hull Building

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

DONALD C. CAULKINS

Deputy Attorney General

450 James Robertson Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee 37219

Counsel for Respondents

Attorney General

State of Tennessee

St. Louis Law Printing Co.. Inc.. 812 Olive Street 63101 314-231-4477

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Opinions B e lo w ......................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................................... 1

Question Presented .................................................................. 2

Statement.................................................................................... 2

Argument ...................................................... 5

Conclusion............................................................. 7

Table of Cases

Department of Banking v. Pink, 317 U.S. 264 .................. 1

East Texas Motor Freight v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395. .5, 6, 7

Foreman v. United States, 361 U.S. 4 1 6 ........................... 1

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company, 424 U.S. 747 6

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792 ......... 6

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 ......................... 6

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1978

No. 78-1158

ERONEOUS SHIPP,

Petitioner,

v.

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et a!.

On Petition for a W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION

OPINIONS BELOW

The court of appeals’ opinion — F.2d — 17 F.E.P. cases

1430 (Aug. 7, 1978) is in petitioner’s Appendix pp. 37(a)-

54(a). The opinions of the district court on December 20, 1974

and Sept. 25, 1975 are not officially reported but are found

in the petitioner’s Appendix, pp. la-8a and 9a-36a.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals was entered on Au

gust 7, 1978. A petition to rehear was filed on Aug. 18, 1978

and overruled on October 26, 1978. The petition for a writ of

— 2 —

certiorari was filed on January 24, 1979 and is therefore out

of time under Rule 22(2) of the rules of this Court. But see

Department of Banking v. Pink, 317 U.S. 264, 266 (1942);

Foreman v. United States, 361 U.S. 416 (1960). The jurisdic

tion of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The three questions presented by the petition in this case

are not fairly raised in the record in the opinion of the court

of appeals. The true question presented is whether this case,

which was never certified as a class action— or even asked to

be certified as a class action— may be properly maintained as

a class action and whether the plaintiff is a proper representa

tive of a never-defined and never-certified class of persons

alleging that they were discriminated against by the Memphis

area office of the Tennessee Department of Employment Se

curity.

STATEMENT

After a bifurcated bench trial in the United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee in Memphis on

March 20-22, 1974 and April 23, 1975, a lengthy opinion and

judgment in favor of the defendants was entered on September

25, 1975. The court held that the plaintiff, Eroneous Shipp,

had not been subjected to any discrimination based on race in

the decision of the Memphis Area Office of the Tennessee De

partment of Employment Security not to refer him for a job

at a local industrial plant and that the defendants had not

engaged in a pattern or practice of racial discrimination which

would entitle a class of persons purportedly represented by

named Plaintiff Shipp to any relief. The Court of Appeals

affirmed, Pet. App. 37a-54a.

— 3 —

1. On March 7, 1969, the plaintiff, Eroneous Shipp, a black

man, responded to an advertisement placed by the Memphis

Area Office of the Tennessee Department of Security on black-

oriented Memphis radio station, WLOK, announcing a job

opening for an assistant traffic manager. Shipp, a school teacher,

called the Memphis area office, inquired about the job and

described his qualifications. He received a discouraging an

swer but, undismayed, picked up an application and on the

following Monday appeared at the local office, clipboard in

hand. He demanded to be referred to the job, and took notes

on everything that was said. The interviewer advised him that

he was not qualified and refused to refer him. When he insisted

that she call the employer anyway, she did, and only then

learned that the job had been filled from another source. Plain

tiff then angrily accused the interviewer of not referring him

because of his race, confronted her superiors, and then retired

to his lodgings to draft a statement based on his notes of the

experience. After re-writing the statement several times, Shipp

presented his report to the NAACP and then filed a timely

complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion. After the EEOC investigation was completed and within

30 days after receiving notice of his right to sue, plaintiff filed

this civil action, alleging that the original defendant, Memphis

Area Office of the Tennessee Department of Employment Se

curity, discriminated against Negro job applicants by classify

ing and referring them exclusively to badly-paid, menial, un

skilled or demeaning jobs without regard to actual abilities,

experience and interest of those applicants.

2. No Rule 23 certification of the class was ever made or

even requested. The petition states at Page 5 that “ at a pre-trial

conference on March 8, 1974 plaintiff expressly sought a more

formal ruling on the propriety of the class action.” Ths state

ment is not supported by the record. Another statement (on the

same page) that the court took no formal action because “coun

sel for TDES stipulated that the March 8, 1974 conference of

— 4

the case was a proper class action” is not supportable either.

Nevertheless, it is beyond dispute that the District Court con

sidered what it repeatedly called the “class action” aspects of

this case,” (see, e.g., Pet. App. 10a) at great length, and held

that no pattern or practice of discrimination on the basis of race

for the Memphis Area Office could be demonstrated. Experts

for both sides agreed that no such pattern was shown by the

computerized data presented, including detailed records of over

52,000 referrals by the Memphis Area Office. Disparities in

the wage levels of TDES referrals by race (TDES referrals are

almost 70 per cent black) were explained by Dr. Joseph Ullman,

plaintiffs’ expert, as resulting from the differences in education

and experience levels of white and black applicants. Sophisti

cated control methods employed by the plaintiff’s expert to

eliminate natural disparity arising from these differences were

successful. The defendants’ expert, Temple University Depart

ment of Statistics chairman, Dr. Bernard Siskin, was able to

demonstrate that the Memphis Area Office (which both sides

agreed was specifically organized to aid the disadvantaged)

could actually be said to be affirmatively discriminating in

favor of black who were, on the average, referred to better

paying, higher-skilled jobs than whites with similar education

and job experience.

3. The court of appeals held that the district court’s finding

that the plaintiff had not been discriminated against was not

clearly erroneous. Pet. App. 49a-50a. The court of appeals

further held that plaintiff was not eligible to represent a class of

persons who were allegedly injured by discrimination because of

the district court’s finding that he was not injured himself and

and the fact that this finding preceded certification. The Court

of appeals specifically stated “plaintiff never motioned the Court

for class certification, nor did the District Court certify the class

suu sponte.” The court of appeals added that, since Shipp had

never been a TDES employee or even an applicant, his bid to

represent a class of TDES employees failed to meet the typicality

requirement of Rule 23(a)(3). Pet. App. 52a.

— 5 —

ARGUMENT

1. The petition would have considerably more appeal if it

correctly reflected the content of the record and the holding of

the court of appeals. For example, it is clear that the district

court did not “erroneously fail to certify the class action,” but

that the plaintiff failed to request such a certification. And the

pretended “stipulation” during the pretrial conference, where the

plaintiff “expressly sought a more formal ruling on the propriety

of the class action” is not supported by the record, to put it

mildly. Petitioner’s statement that the Sixth Circuit held that

“ the District Judge, despite two requests by plaintiff’s counsel

[neither of which are in the record], erroneously failed to decide

whether the case should be formally certified as a class action”

(Pet. 9) does not fairly reflect Judge Keith’s holding for the

unanimous Court. What Judge Keith did say was that Shipp

was not a proper class representative because (a) his individual

claim was held to be without merit before certification and (b)

his claim was not typical because of his failure to be a member

of the class— or one part of the class— he sought to represent—

namely TDES’ employees and applicants for employment. In

deed, except for the petitioner’s attempts to supplement the rec

ord with non-existent requests for certification and “stipulations”

this case is identical to the procedural situation in East Texas

Motor Freight v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395 (1977).

2. Petitioner’s second reason for granting the writ alleges

that the court of appeals’ decision holds that an individual claim

of discrimination can be rejected without deciding whether

there is a pattern of practice of discrimination. The court of

appeals held no such thing. Indeed, the District Court made

two rulings that Shipp’s individual claim was without merit.

The first ruling was made only after the Judge had heard all

the evidence on Shipp’s individual claim and all of the plaintiffs

evidence, statistical and otherwise, on the pattern and practice

— 6 —

allegations. It is true that the plaintiff asked the Trial Judge

to reconsider the ruling on the individual claim. He did so and,

after hearing the defendants’ pattern and practice evidence, re

affirmed his initial holding. The procedure employed was en

tirely consistent with the holdings of this Court in McDonnell

Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792, 804-805 (1973); Team

sters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 357-62 (1977); and

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Company, 424 U.S. 747,

772-773 (1976).

Whatever merit here is to petitioner’s implied argument that

the Trial Judge erred in deciding the plaintiff’s individual claim

without making an actual finding on the existence of a pattern

or practice of discrimination (even though he had already heard

the plaintiff’s entire case) was certainly remedied by his recon

sideration and reaffirmation of his holding after hearing the

defendants’ expert.

We agree that even in the case where a trial judge denies

certification— properly or improperly— the individual plaintiff

would be entitled to discover and introduce evidence of a general

practice of discrimination in support of his own claim. The

court of appeals did not hold to the contrary. There is nothing

in the petitioner’s argument on this issue which deserves plenary

review of this Court.

3. Petitioner’s third argument that certiorari should be granted

to clarify what form of Order is required to constitute a class

certification under Rule 23 is similarly contrived. Whatever

form of order is required, it is clear that some kind of order is

required. Since the plaintiff never even sought an order and

since the district court entered none at all, there is no reason

to grant certiorari on this issue, since it is entirely unnecessary

to the decision of this case after East Texas Motor Freight v.

Rodriguez, supra.

— 7 —

CONCLUSION

This case is no different from East Texas Motor Freight v.

Rodriguez. The petition for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

HAILE & MARTIN, P.A.

HENRY HAILE