Motion to Vacate Suspension of and Reinstate Order Pending Certiorari with Exhibits

Public Court Documents

September 30, 1968

82 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Alexander v. Holmes Hardbacks. Motion to Vacate Suspension of and Reinstate Order Pending Certiorari with Exhibits, 1968. 4d06c249-cf67-f011-bec2-6045bdd81421. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2189e4d5-ac65-4218-b763-2cc115c444eb/motion-to-vacate-suspension-of-and-reinstate-order-pending-certiorari-with-exhibits. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

A

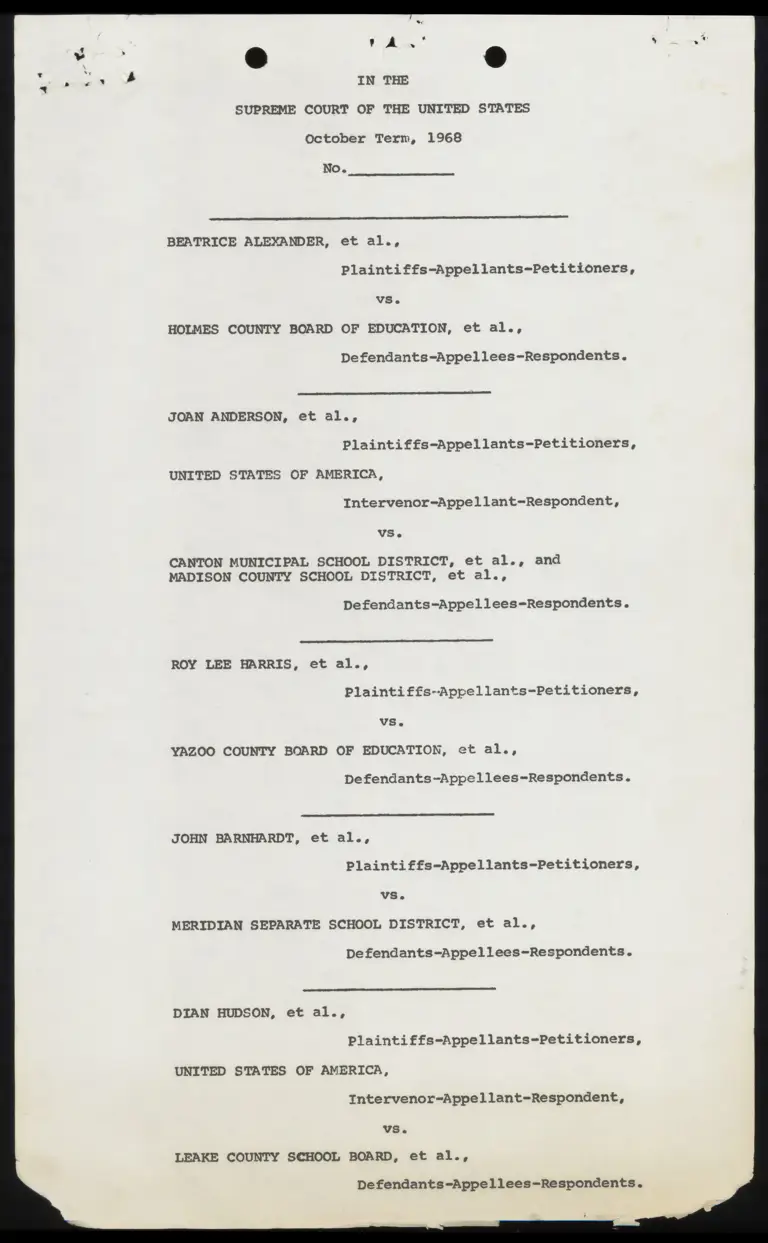

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1968

No.

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants~Petitioners,

vs.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants~Appellees-Respondents.

JOAN ANDERSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants~-Petitioners,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Intervenor-Appellant-Respondent,

vs.

CANTON MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al., and

MADISON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

ROY LEE HARRIS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

VS.

YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees~Respondents.

JOHN BARNHARDT, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

vs.

MERIDIAN SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees~Respondents.

DIAN HUDSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants-Petitioners,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Intervenor-Appellant-Respondent,

vs.

LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

[3

—~ Y

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants~-Petitioners,

VS.

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defendants~-Appellees-Respondents.

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants~Petitioners,

VS.

ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT and

QUITMAN CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Defendants-Appellees~Respondents.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant-Respondent,

CEORGE MAGEE, JR.,

Intervenor-Petitioner,

VS.

NORTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL

DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants~Appellees-Respondents,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant-Respondent,

GEORGE WILLIAMS, et al.,

Intervenors-Petitioners,

vs.

WILKINSON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees-Respondents.

MOTION TO VACATE SUSPENSION OF, AND TO REINSTATE

PENDING CERTIORARI, AN ORDER OF THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT ORDERING

IMPLEMENTATION OF SCHOOL DESEGREGATION PLANS AT

THE COMMENCEMENT OF THE 1969-1970 SCHOOL YEAR

TO: The Honorable Hugo L, Black, Circuit Justice

For The Fifth Circuit.

Petitioners, Beatrice Alexander et al., pray that an order

be entered, pending consideration of a timely petition for a

writ of certiorari: (1) vacating an order of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit entered August 28, 1969

which amended a previous order of that Court of July 3, 1969

(as amended July 25, 1969) by staying the provisions of said

order requiring the formulation and implementation of plans

of school desegregation commencing with the beginning of the

1969-70 school year; and (2) reinstating the order of July 3

(as amended July 25) providing for immediate implementation

of said plans of desegregation for the public schools of

respondent Mississippi counties. In support thereof, petitioners

show the following:

I

STATEMENT

These cases involve the desegregation of the public schools

of fourteen districts in Mississippi. The cases were all filed

originally in the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi. In seven of the cases involving

twelve districts, suits were initiated by Negro plaintiffs.

In two of the cases, Negro plaintiffs intervened August 25,

1969 in suits originally instituted by the United States.

In all of the cases, the district court, prior to the

decision of this Court in Green v. New Kent County Board of

Education, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), approved freedom of choice

desegregation plans. After the decision in Green, plaintiffs

filed motions in the district court for additional relief,

seeking the formulation and implementation of desegregation

plans other than freedom of choice, on the grounds that the

- 3 -

existing plans were not adequate to convert the dual school

systems in these districts to unitary rete The district

court denied these motions and refused to require the defendant

- school boards to formulate and implement plans promising

“realistically to work now." Green, supra, at 439 (emphasis

in original). Consequently, the Negro plaintiffs appealed

the cases instituted by them to the United States Court of

Appeals, as did the United States in the two cases in which

Negro petitioners later intervened. At or about the same

time, the United States, plaintiff in eleven other cases

(involving a number of school districts, to which cases Negro

plaintiffs were not parties) also appealed to the Fifth

Circuit from the refusal of the district court to enter

orders consistent with this Court's decision in Creen. The

cases appealed both by private plaintiffs and the United

States were all consolidated by the Court of Appeals,

On July 3, 19692, after the cases were briefed and argued,

the Fifth Circuit entered an order reversing the decision of

the district court in all the cases, ordering the district

court to require the school boards to seek the assistance of

the Office of Education of the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare in formulating new school desegregation plans for

each district and requiring the filing and implementation of

the plans in accordance with a timetable suggested by the

United States. (A copy of the July 2 order of the Fifth Circuit

is attached as Exhibit 1). The timetable approved by the

Court of Appeals provided for the submission of plans by

August 11, 1969, and their implementation at the commencement

1l/ All of the respondent school districts were appellees

in Adams v. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968).

of the 1969-70 school year in each of the districts. Subse-

quently, on July 25, 1969, the Court of Appeals amended its

order with respect to the date for implementation of these

plans providing in the amended order that the plans would go

into effect by September 1, 1969. (A copy of the amended

order is attached hereto as Exhibit 2).

Subsequent to the order of ie Court of Appeals, the

district court, in obedience to the mandate, required the

school boards in the twenty-five consolidated cases to seek

the assistance of the Office of Education of the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare in formulating the plans.

The plans were filed in accordance with the Court's timetable

on August A On August 19, little more than a week after

the filing of the plans, Robert Finch, the Secretary of Health,

Education and Welfare, wrote a letter addressed to each of

the judges of the district court and to the Chief Judge of

the Fifth Circuit, the Honorable John R. Brown, requesting

delay in the implementation of the plans at the commencement

of the school year, and asking for the opportunity to file

new plans by December 1, 1969. A formal motion by the United

States to this effect was made in the Court of Appeals on

August 21, 1969, asserting as its basis, Secretary Finch's

letter, a copy of which was attached to the motion. (The

motion of the United States with the letter of Secretary Finch

attached is appended hereto as Exhibit 3). The Secretary's

letter, and the subsequent motion, was the first indication

that the United States was now repudiating the timetable

which it had urged upon the Court of Appeals and the desegre-

gation plans prepared by it which, when filed, had been

represented to the court as acceptable both with respect to

substance and timing.

2/ Copies of the H.E.W. plans for the twelve districts involved

in the suits initially brought by Negro plaintiffs are submitted

herewith as appendices to these moving papers.

August 22, 1969, counsel for the Negro plaintiffs in

the seven cases initiated by them filed an opposition to the

government's motion, asserting that if the motion were granted,

the constitutional rights of black children in Mississippi

would be further delayed; and further, that the delay would

result from the long-standing pattern of resistance to the

consitutional rights of Negro citizens in Mississippi which

this Court held in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) would

not be permitted to act as a bar to the realization of the

right of Negro children to an integrated education. (A copy

of this opposition is attached hereto as Exhibit 4).

By oral direction of the Court of Appeals, a hearing

was held before the district court in Jackson, Mississippi

on August 25, 1969 on the motion of the United States. At

the hearing, the United States was arrayed with all the

defendant school boards in the cases against the interests

of the Negro plaintiffs, who were insisting on the vindication

of their long-delayed constitutional right to equality of

educational A Consequently, at the hearing the

private plaintiffs (1) moved to realign the parties in the

suits initiated by them to make the United States party-

defendant with the school officials and (2) moved to intervene

in two additional cases which had been initiated by the

United States and to realign the parties in those cases.

The intervention was granted by the district court in the

two cases, but the motion to realign the parties to make

the United States defendant was denied.

At the hearing, the United States presented testimony

of two witnesses employed by the Office of Education of

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, who testified

3/ some of the school boards formally joined in the motion

of the United States. See Exhibit 5 hereto.

that the integration plans submitted by them were educationally

sound. However, both witnesses testified, implementation

should be delayed because there were administrative difficulties,

generally stated, in implementing the plans' provisions =-

difficulties which by their own admission the school boards

had not attempted to solve in the fifteen years since Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). In opposition,

private plaintiffs presented the testimony of an expert witness

who stated, after reviewing the plans submitted, that there

were not in his opinion any educational reasons to delay

their implementation; and further, that the reasons given by

the government's witnesses were generalities not related to

a single specific situation in any of the school districts

involved. Also introduced at the hearing was a letter from

Dr. Gregory Anrig, Director of the Equal Educational Opportuni-

ties Division, Office of Education, United States Department

of Health, Education and Welfare =~ the person responsible

for final review and submission of the plans to the court =-

who wrote to the district court that in his judgment the plans

were unobjectionable, both educationally and from the stand-

4/

point of timing.

5/

The record of the hearing was immediately transmitted to

the Court of Appeals pursuant to that Court's oral direction

to the district court. The district court, in transmitting

the record to the Court of Appeals, recommended that the

delay requested by the United States be granted. (A copy of

the district court's recommendation of decision is attached

hereto as Exhibit 7). On August 28, the panel of the Court

of Appeals which had entered the July 3 order (Chief Judge

Brown, Judges Thornberry and Morgan) entered an order granting

the government's request for delay in implementation of the

plan by amending their previous orders. (A copy of this order

4/ A copy of the letter transmitting the plans to the district

court is submitted herewith as an appendix to these motion papers.

5/ The transcript of the hearing is submitted herewith as an

Appendix to these motions papers.

“low

3 ® ®

hb)

is attached hereto as Exhibit 8).

II

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE MOTION

A,

The Authority Of This Court, Or A Single

Justice Of The Court, To Grant The Requested

Relief Is Conferred By 28 U.S.C. § 1651la.

Petitioners seek an order vacating what is in effect a

stay by the Court of Appeals of its previously entered order.

An order comparable to that which petitioners here seek was

entered by this Court in Lucy v. Adams, 350 U.S. 1 (1955).

The Lucy case involved the application of Negro petitioners

for injunctive relief to obtain admission to the then all-

white University of Alabama. The district judge granted

relief and then suspended his order. The Court of Appeals

refused to vacate the stay of the District Court injunction.

On motion in this Court, an order was entered vacating the

stay and reinstating the injunction ordering the University

to admit petitioners. Thus, the Lucy case is a direct precedent

for the relief requested here. The Court clearly has power

to grant the requested relief under the all-writs statute,

28 U.S.C. § 1651.

The power of a single Justice to grant such relief is

equally clear. Similar relief was granted by Mr. Justice

Black in an order entered on August 30, 1968 in Boomer v.

Beaufort County Board of Education. (Unreported). In

Johnson v. Stevenson, 335 U.S. 801 (1948), a single Justice

of this Court granted a stay of a District Court injunction

pending an appeal in the Court of Appeals. The Court subse-

quently approved the action of Mr. Justice Black acting as

a single Justice, by refusing to modify his order, Johnson v.

Stevenson, supra. For a discussion of the Court's power to

grant stays pending an appeal in the Court of Appeals, see

Stern & Gressman, Supreme Court Practice (3rd Ed. 1962),

- 8 -

: ® a

J

Pp. 418-420, 431-433; Robertson & Kirkham, Jurisdiction of

the Supreme Court of the United States (1951), pp. 900-902;

see also, Rule 51 of the Rules of this Court.

B.

The Delay In School Desegregation

Granted By The Court Of Appeals In

These Cases Is Unijustifiable.

When these cases were appealed and consolidated on appeal

with similar appeals by the United States, the Court of Appeals,

in recognition of the fact that "{[tlhe time for mere ‘deliberate

speed’ ha[d] run out" Griffin v. County School Board, 377 U.S.

218, 234 (1964) expedited its consideration of the appeals.

Its opinion-order of July 3rd stated its reasons:

"The Court on the motion to summarily reverse

or alternatively to expedite submission of

the case filed by the Government and the

private plaintiffs concluded that fundamental

constitutional rights of many persons would

be jeopardized, if not lost, if this Court

routinely calendared this case for briefing

and argument in the regular course. Before

we could ever hear it, the opening of the

school year September 1969-1970 would have

gone by. With this and the total absence of

any new issue even resembling a constitutional

issue in this much litigated field, we therefore

concluded that the appeals should be expedited.”

(Emphasis added.)

In addition to expediting the appeals, the Court also required

the parties to submit in advance of oral argument proposed

opinion-orders so that it could arrive at a decision quickly

after oral Eg As the Court noted in its August 28th

opinion-order, all parties were fully heard and given the

opportunity to present any arguments they had to justify delay

7/

in implementation of new school plans. After entertaining

6/ "As questions of time present such urgency as we approach

the beginning of the new school year September 1969-70, the

court requested in advance of argument that the parties submit

proposed opinion=-orders modeled after some of our recent school

desegregation cases." July 3 opinion-order, p. 1l.

7/ "On the argument, the Court heard from some 18 counsel

over a period of the entire day." August 28 opinion=~order,

Pe. ®

the arguments of the parties, including the United States,

and reviewing the pre-filed proposed opinion-orders, the

Court issued its opinion-order the very next day after the

arguments concluded.

In its opinion, the Court was firm in not countenancing

any arguments for delay in the implementation of the new

school plans that it required to be prepared beyond the opening

of the 1969-70 school year. Its firmness in this regard was

in response to a record which demonstrated the woeful inadequacy

of the freedom of choice plans operating in the school

Alstuigtel as well as the inadequacy of the arguments urged

by the defendant school boards for retention of these in-

adequate plans, e.g., polarization of Negroes and whites,

exodus of white students from the school system (July 3 opinion=-

order, pp. 7-8). This latter argument was properly characterized

as "but a repetition of contentions long since rejected in

Cooper v. Aaron.”

Since the July 3 opinion-order, there have been neither

new facts of record nor any new arguments justifying in any

way the Court's retreat from its order of that date. Indeed,

in the period between the date of that order and the receipt

of Secretary Finch's letter, plans for desegregation of the

school districts, agreed by all the educators who reviewed

them to be sound, were presented by the United States to the

district court in accordance with a timetable for their pre-

sentation and implementation proposed and urged by the United

States! Nothing occurred during this period to make that

8/ Attached to the Court's opinion-order were footnotes

showing the almost total absence of any measurable integration

both with respect to pupil and faculty assignment. See also

the detailed summary of statistics in each district prepared

by the United States for the oral argument at the request of

the Fifth Circuit, submitted herewith as an appendix to these

motion papers.

“ 10 =

1

timetable unacceptable save what has perennially marked the

frustration of school desegregation over the years: (1) the

absolute refusal of the school officials to prepare for the

implementation of plans that would actually accomplish de-

segregation of the public schools and (2) the hardening of

community attitudes in resistance to any effective integration

plans. But as the Court of Appeals itself noted in its

July 3 opinion~-order, these things are "the total absence of

any new issue even resembling a constitutional issue in

this much litigated field" and are only repetitive "of contentions

long since rejected in Cooper v. Aaron." As this Court said

in Green v. School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430,

last year, "it is relevant [here as in that case] that this

first step did not come until some 11 years after Brown I was

decided and 10 years after Brown II directed the making of

a 'prompt and reasonable start'", 391 U.S. at 438. As this

Court in Green continued "[t]his deliberate perpetuation of

the unconstitutional dual system can only have compounded the

harm of such a system. Such delays are no longer tolerable..."

Ibid.

Nor did the August 25 hearing ordered by the Court of

Appeals in response to the motion of the United States for

delay produce any acceptable reasons justifying the delay.

The testimony was to the effect that there were some things

that it was desirable to do before implementing the H.E.VW.

proposed plans. But not only was there contrary testimony

that these steps were not sufficient to justify delay in

implementation of the plans; there was also the total absence

of any evidence that these school officials, who had made

no effort to prepare either their school systems or their

communities for the implementation of any plan amounting to

more than token integration, would now do so. Thus the Court

% ® @®

of Appeals, without stating any reasons for its actions other

than the Government's request, assented to delay of effective

school integration plans without any evidence that the delay

would bring about the desired results. Clearly in light of

Green, there could no longer be any acceptable reason for

postponing the full realization of the constitutional rights

of the black children of Mississippi in their attendance in

school districts such as those before this Court, districts

in which the only "reasons" for delay are the failures of

the school administrators themselves and the feared reaction

of the community. If these reasons are in fact acceptable,

if these reasons fifteen years after Brown I can serve to

justify delay in the implementation of desegregation plans,

then desegregation of schools will never be accomplished and

the decision in Brown will remain a mockery.

«13 «

“ 7

> ® rR A

1

C.

The Delay in Desegregation Occasioned

By The August 28 Order Will Cause

Petitioners Irrevarable Harm And In

The Circumstances Of The Cases It

Would Be Equitable To Grant A Stay

Injunction Pending Certiorari

It is respectfully submitted that the balance of equities

favors the petitioners and the reinstatement of the original court

order pending certiorari. At stake in the litigation is the

constitutional right of Negro schoolchildren in Mississippi as

declared by this Court more than 15 years ago in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483; 349 U.S. 294 (1954-55). This Court has

on numerous occasions since the Brown decision considered applica-

tions for stays to delay compliance with the Brown decision.

Consistently, the Court and the individual Justices of the Court

have rejected efforts to delay compliance with Brown bv southern

school districts and universities by invoking the discretionary

powers of the courts to issue stays. See, e.g., Lucy v. Adams,

350 U.S. 1 (1955); County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia

v. Hamm, 4 Race Rel. L. Rep. 14 (1959) (Order of Mr. Chief Justice

Warren); United States v. Louisiana, 264 U.S. 500 (1960): Ennis Vv.

Evans, 364 U.S. 802 (1950); Houston Independent School District v.

Ross, 364 U.S. 803 (196C); Orleans Parish School Board v. Bush, 364

U.S. 803 (1960); Danner .v. Holmes, 364 U.S. 9229 (1960), refusing to

reinstate a stay dissolved by Chief Judge Tuttle of the Fifth

Circuit in Holmes v. Danner, 5 Race Rel. L. Rep. 1091 (1961):

Board of Education v. Tavlor, 82 S. Ct. 1C (1961) (opinion by Mr.

Justice Brennan in chambers); Meredith v. Fair, 9 L. Ed. 2d 43, 83

S. Ct. 10 (1962) (opinion of Mr. Justice Black in chambers); Board

of School Commissioners v. Davis, 11 L. Ed. 24 26, 84 S. Ct. 10

(1963) (opinion of Mr. Justice Black in chambers); Wallace v. Lee,

387 U.S. 916 (1967): Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 386

U.S. 1004 (1967). This Court has recently reiterated that delays

in implementing the constitutional right to a desegregated public

school education are "no longer tolerable." Green v. County School

Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968); see also Watson v. Citv of Memphis, 373

A

1 .

U.S. 526, 529 (1963); Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103

(1965); Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965); Griffin v. County

School Board, 377 U.S. 218, 234 (1964); Goss v. Board of

Education, 373 U.S. 683, 689 (1963). In an unreported order

in Boomer v. The Beaufort County Board of Education (August

30, 1968), Mr. Justice Black vacated stay orders in two cases

issued by a panel of the Fourth Circuit, and reinstated in-

junctions requiring prompt school desegregation. In the Boomer

order Mr. Justice Black said that the Green decision "requires

that the desegregation of schools be completely carried out

at the earliest possible moment." The effect of the August

28 order is to postpone any effective desegregation plan in

the school systems for another year. The experience of the

school systems with the freedom of choice plan demonstrates

that no substantial reorganization of the system can possibly

be expected while the free choice plan is continued in effect

for another year. Accordingly, the grant of a delay denies

the petitioners' constitutional rights to desegregated public

education and thus does them irreparable harm. Chief Judge

Tuttle of the Fifth Circuit wrote in Holmes v. Danner, 5 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 1091 (January 9, 1961) that:

The denial of a constitutional rights, for

whatever reason, cannot be said to be wanting

in serious damage merely because the damage

cannot be measured by money. Irreparable

injury results in the denial of a constitutional

right, largely because it cannot be measured

by any known scale of value. I do not believe

that the courts can deny relief when asked to

prevent a continued denial of constitutional

rights merely on the ground that the grant

of relief will produce difficult or unpopular

results,

In United States v. Board of Education of City of Bessemer,

396 F.2d 44, 49 (5th Cir. 1968), the Court said:

Unfortunately, the clock has run. It still

ticks. The past with its demonstrated perform-

ance (or lack of it) cannot be eradicated. The

question then is: What is now to be done =-

done (a) to achieve as soon as possible those

things which ought to have been accomplished

up to this time and (b) to finish the job?

- 14

: a | ®

1

The opinion below states no ground for continuing the

segregation pattern sought to be remedied by the original

order for another school year. Accordingly, it is respectfully

submitted that the order of the Fifth Circuit of July 3, 1969

(as amended July 25, 1969), requiring desegregation of these

Mississippi school districts should be reinstated pending

disposition of a timely petition for certiorari to review

the action of the Court of Appeals in issuing its August 28

order.

Respectfully submitted,

pra . :

4 / 4 - > - 4 - Zz v

{ 4 bo; FIL 7 C ; Ponca HLT

So Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. Amaker

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Melvyn R. Leventhal

Reuben Anderson

Fred L. Banks, Jr.

538% No. Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi

Attorneys for Petitioners

w'i5 -

JAR THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

DT TEU a

Nos, 28030 & 28042

a

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

{Civil Action do, 2075(3))

a

BUFORD A. LEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

Vv.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

- Defendant-Appellant,

Vo.

MILTON EVANS,

Third Party

' Defendant-Appellee.

(Civil Action No. 2034 (1))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

SE Plaintiff-Appellant,

v. .

KEMPER COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1373(Z))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

NORTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 3807(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appecllant,

Ve

NATCHEZ SPECIAL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

y Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1120(W))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

MARION COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al., i

Defendants-Appellees. ;

(Civil Action lo, 21781))

JOAN ANDERSON, et al.,

- ° ~

Pl a: iit a lg: Anne antec

CA bl Ce COD Lays ded Cats C0

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

. 2laintiff-Intervenor-Appellant,

Ve

THE CANTON MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

and THE MADISON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3700(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Y,

SOUTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL, DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action Yo. 3984 (J))

BEATRICE ALL. {ANDER, et al.

Plaintiffs- Appellants,

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Defencanie ~-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3779(J))

ROY LEE HARRIS, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

V.

THE YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

| Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 1209(W))

JOHN BARNHARDT, et al.

Plaintiffe-Appellants,

Ve.

MERIDIAN' SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al,

: Defendants- Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 1300(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Yeo

i

NESHOBA COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1396(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

ve.

NOXUBEE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants - Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1372(E))

A A A Stn. int mete +

UNITED STATES OF AMER LCA,

Plaintiff-Ap; sellant,

V.

LAUDERDALE COUNTY SCHOOL BISTRICY, eb al, ,

Defendants Appaliecs,

(Civil Action No. 1367 (E))

——

DIAN HUDSON, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Intervenor- Appellant,

V.

. LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al,,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 3382 3).

UNITED STATES OF AME RICA,

Plaintiff- Appellant,

yg

COLUMBIA MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL, et al.,

Defendants- -Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2199 (H))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve.

AMITE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

Defendants- ADDAllced.

(Civil Action No. 3983 (J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

COVINGTON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ef al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2148(H))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Vv e

LAWRENCE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 2216 ())

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR., et:al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

x7

v e

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

: Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1096 (W))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve.

WILKINSON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 1160(W))

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, et al.

Plaintiffs- -Appellants,

Ve

THE ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT

gn QUITMAN CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Defendants-Appelleecs.

{Civil Action No, 1302(E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v.

LINCOLN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.

Defendants-Appellees.

[

’

{Civil Action No, 4294(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

V ® :

PHILADELPHIA MUNICIPAL SEPARATE or Ny

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 1368(E))

UNITED STATES OFF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

FRANKLIN COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

; Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 4256(J))

Appeals from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi :

(July 3, 1969)

Before BROWN, Chief Judge, THORNBERRY and MORGAN, Circuit Judges.

L

4

PER CURIAM:

As questions of time present such urgency as we

approach the beginning of the new school year September

1969-70, the court requested in advance of argument that

the parties submit proposed opinion-orders modeled after

some of our recent school desegregation cases. We have

drawn freely upon these proposed opinion-orders.

These are twenty-five school desegregation cases

in a consolidated appeal from an en banc decision of

the UU. 8. District Court for the Southern District of

yi

Mississippi. These cases present a common issue:

whether the District Court erred in approving the con-

tinued use by these school districts of freedom of

choice plans as a method for the disestablishment of

the dual school systems.

The plaintiffs' position is that the District

Court erred in failing to apply the principles anncunc

- -~

K .

in recent decisions of the Supreme Court and of this

Court. a AT

> Hoh,

These same school districts, along with others,

were before this Court last vear in Adans Vv. Mathews,

403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir., 1968). The cases were there

remanded with instructions that the district courts

(1) whether the school board's Xigting

plan of desegregation is adequate "to

convert [the dual systen] to a unitary

system in which racial discrimination

would be elininated root and branch" and"

(2) whether the proposed changes will

result in a desegregation olan that

"promises realistically to work now."

oe

~

ind

z

“3

pe

A .

¢

’

403 F.2d at 188. In determining whether freedom of choice

- would be acceptable, the following standar O

= \

4 NN

Ss wore to be

applied:

If in a school distvict thers are

still all-Hegro schools or only a

small fraction of Negroes enrolled in

whlie schools, or no substantial

integration of faculties and school

activities then, as a matter of law,

the existing plan fails to neet

constitutional standards as estab-

lished in Green.

en a ree ea

In all pertinent respects, the facts in these cases

are similar. No white students has ever attended any

traditionally Negro school in any of the school districts.

Every district thus continues to operate and maintain its

all-Negro schools, The record conpels the conclusion tha

to eliminate the dual character of these schools alterna-

tive methods of desegregation must be employed which

would include such methods as zoning and pairing.

Not only has there been no cross-over of white

students to Negro schools, but only a snall fraction of

Negro students have enrolled in the white schools. The

highest percentage is in the Enterprise Consolidated

School District, which has. 16 percent of its Negro

students enrolled in white schools~-—-a degree of desegre-

gation held to be inadequate in Green v. County School

Board, 331 U. 8. 430 (1968). The statistics in t

remaining distr.cts range from a high of 10.6 percent

in Porrest County to a low of 0.0 percent in Neshoba

,. .

and Lincoln Counties. For the most part school activi-

ties also continue to be segregated, Although Negroes

attending predominantly white schools do participate on

teams of such schools in athletic contests, in none of

the districts do white and all-Negro schools compete in

¢

s

athletics,

: »

These facts indicate that these cases fall squarely

within the decisions of the Supreme Court in Green and

its companion cases and the decisions of this Court.

See United

Ea

States v. Greenwood Municipal Senarate School (

nr a rn re 4 at te —————— ——— ——————

Distvrict, 4056 ¥,.24 1086 45th Cly. 19469); Henry v. Clarhksg-

dale Municipal Separate School District, No. 23,255(5¢th

Ss —— a —— a Cr—a. re St et a Ar —— — ————

Cir., March 6, 1969); United States v. Indianola Municipal

Crrmaradn Separate SC

Br arn rn et th ee + Some — ——

1969); Anthony v. Marshall County Board of Education,

oh

0 Py

0 oy

No. 26,432 {5th Cir.; April 15, 1969); Hall v. S

Parish.School Board, No. 26,450 {5th Civ., May 28,1569);

— —— —— ————-- —

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County,

a

No. 26,886 (5th Cir., June 3, 1969); United States v.,

Jefferson County Board of Education, No. 27,444 (5th

rn cn tr amen. To

.

Cir., June 26, 1969); United States v. Choctaw County

Board of Education, 5 Cir. 1969, F.28 (Fo. 27, 297,

July 1, 1969); United States v. The Board of Education

of Baldwin County, 5 Cir, 15690, F. 24 (No. 27,281;

July 1, 1969); United States v. The Board of Education of

the City of Bessemer, 5 Cir. 1969, F.2d

(Nos. 26,582; 26,583; 26,584, July 1, 1969). The proper

3

4

7

conclusion to be drawn from these facts is clear from

the mandate of Adams v. Mathews, supra: "as a matter of

law, the existing plan fails to meet constitutional

standards as established in Green,"

3a

[§

r We hold that these school districts will no

Tonner be able to rely on freedom of choice as the

method for disestablishing their dual school SyS—

tems.

This may mean that the tasks for the courts

will become more difficult. The District Court

itself has stated that it "does not possess any of

the training or skill or experience or facilities

to operate any kind of schools; and unhesitatingly

admits to its utter incompetence to exercise or

exert any helpful power or authority in that area.”

And this Court has observed that judges "are not

educators or school administrators." United States

v. Jefferson County Board of Education, supra at

a a — >

855. Accordingly, we deem it appropriate for the

Court to require these school boards to enlist the

assistance of experts in education as well as

desegregation; and to require the school boards to

cooperate with them in the disestablishment of their

dual school systems.

¢

FJ

With respect to faculty desegregation, little

2/

progress has been made. Although Natchez-Municipal

Separate District has a level of 19.2% and Lawrence

County a level of 10.6%, seven school districts have

less than one full-time teacher per school assigned

across racial lines. In the remaining systems, fewer

than 10 percent of the full-time faculties teach an

schools in which hel race is in the minority. Paculties

must be integrated. United States v. Montgomery County

Board of Education, No. 798, at 8 (Sup.Ct., June 2, 1969).

Minimum standards should be established for making

substantial progress toward this goal in 1969 and finish-

ing the job by 1970. United States v. Board of Education

of the City of Bessemer, 5 Cir., 1968, 396 F.2d 44 ,

J

Choctaw County, supra; Baldwin County, supra.

a i :

{

’

authorities from influencing the exercise of choice

by students or parents. We find this completely

unsupported. This record affords no basis for any

expectation of any substantial change were the provision

modified.

Based upon similar testimony, the School Districts

urged a related contention that the uncontradicted

statistics showing only slight integration are not a

reliable indicator of the commands of Green. This

argument rests on the assertion that quite apart from

a prior dual race school system, there would be concen-'

tration of Negroes or white persons from what was described

as "polarization." To bolster this, they pointed to

school statistics in non-southern communities. Statistics

are not, of course, the whole answer, but nothing is as

pHs, m— v

emphatic as zero, and in the face of slight numbers and

low percentages of Negroes attending white schools, and

no whites attending Negro schools, we find this argument

unimpressive.

In the same vein is the contention similarly based

on surveys and opinion testimony of educators that on

stated percentages (e.g., 20%, 30%, 70%, etc.), integration

of Negroes (either from influx of Negroes into white

schools or whites into Negro schools), there will be an

Ld

’

exodus of white students up to the point of almost 100%

Negro schools. This, like community response or hostility

or scholastic achievement disparities, is but a repetition

of contentions long since rejected in Cooper v. Aaron,

1958, 358 U.S. 1, B.08. LeEd, Cy Stell wv. rom —

Savannan-Chatham County Bd. o

F.2d 55, 61; and United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of

Bd.,, 5 Cir., 1959, F.248 [No. 27444, June 26, 1969].

¢

if

The order of the District Court in each case

is reversed and the cases are remanded to the

District Court with tle following direction:

l. These cases shall receive the highest

priority.

2. The District Court shall forthwith request

that educators from the Office of Education of the

united States Department of H=alth, Education and

Welfare collaborate with the defendant school boards

in the preparation of plans to disestablish the dual

school systems in question, The disestablishment

plans shall be. directed to student and faculty

assignment, school bus routes if transportation is

provided, all facilities, all athletic and other

tion activities. The District Court shall further

require the school boards to make available to the

Office of Education or its designees all requested

information relating to the operation of the school

.

systems.

3. The board, in conjunction with the Office

Of Education, shall develop and present to the District

Court before August 11, 1969, L an acceptable plan of

‘desegregation.

4. If ths Office of Education and a school

board agree upon a plan of desegregation, it shall

be presented to the District Court on or before

¢

>

August 11,1969. The court shall approve such plan

for implementation commencing with the 1969 school

year, unless within seven days after submission to

the court any party filee any objection or propos~d

amendment thereto alleging that the plan, ‘or any

part thereof, does not conform to constitutions

standards.

5. If no agreement is reached, the Office

of Education shall present its proposal to the

District Court on or before August 11,1969. The

Court shall approve such plan for implem=ntation

commencing with the 1969 school year, unless

within seven days a party makes proper showing

that the plan or any part thereof does not conform

tO congtitutional standards.

6. For plans to which objections are made

or amendments. suggested, or which in any event

the District Court will not approve without a hear-

ing, the District Court shall. hold hearings within

>

five days after the time for filing objections and

proposed. amendments has expired. In no event later

than August 21, 1969.

7. The plans shall .be completed, approved,

and ordered for implementation by the District

Court no later than August 25, 1969. Such a plan

shall be implemented commencing with the beginning

of the 1969-1970 school year.

-10~-

¢

2

8. ‘Because of the urgency of [ormulating

and approving plans to be implemented for the 1969Y-

70 school term it is ordered as follows: The

mandate of this Court shall issue immediately and

will not be stayed pending petitions for rehearing

Or certiorari. This Court will not’ extend the

time for filing petitions for rehearing or briefs

in support of or in opposition thereto. Any

appeals from orders or decrees of the District

Court on remand shall be expedited, The record

on any appeal shall be lodged with this court and

appellants' brief filed, all within ten days of

the date of the order or decree of the district

court from which the appeal is taken, Appellee's

| ol

Le brief shall

court will determine the time and place for oral

argument if allowed, The court will determine

the time for briefing and for oral argument if Oo oo

allowed, No consideration will be given to the

RE

>

fact of interrupting the school year 'in the event g y

further relief is indicated.

REVERSED AND REMANDED WITH DIRECTIONS

«ll

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Vv.

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL,

Nos.

Y/

Plaintiff-Appeliant,

Defendants-—-Appellees.

28030 and 28042

FOOTNOTES

Illustrative are the following tables,

he

in each district and the enrollment by race:

District

Amite

Canton

Columbia

Covington

Forrest

Franklin

Hinds

Kemper

Lauderdale

lawrence

leake

Lincoln .

Madison

Marion

Meridian

Natchez-Adams

Neshoba

North Pike

Noxubee

Philadelphia

Sharkey-Issaquena

Anguilla-Line

South Pike

Wilkinson

Total

RACIAL CHARACTER

Number

of Schools

nN

R

W

W

A

R

N

N

O

U

T

O

O

N

T

U

U

T

A

W

W

D

I

d

e

n

pt

pd

13.

corrected

racial character

to the latest

available data furnished and checked by counsel, in the cases in which

the Government is a party showing of the schools

All- All- Predominantly

Negro White White

2 1 2

3 . 2

1 - 3

3 Yih 3

1 2 6

3 _ 2

10 1 11

2 1 2

Y 2 2

2 3 2

3 3. 1

2 3 -

4 - 4

1 2 2

8 - 11

7 8

1 —- 1

1 2 1

3 - 3

3 l 1

4 - 1

2 1

2 oS

2 2

Contd - Footnotes

2/ The latest corrected figures —

District

Amite

Canton

Columbia

Covington

Forrest

Franklin

Hinds

Kemper

Lauderdale

lavrence

leake

Lincoln

Madison

Marion

Meridian

Natchez-Adams

Neshoba

North Pike

Noxuhee

Philadelphis

Sharkey-Issaquena

Anguilla-~Line

South Pike

Wilkinson

Full & part

time teachers

Full time desegre-

gating teachers

Negro White

95 66

120 81

43 71

64 103

43 122

44 45

295 281.9

68 45

82 131

S50 81

87 90

38 74

147 66

48 96

180 317

484

35 86

26 30

138 61

25 46

71 31

78 52.8

97 39

-14-

see Note

Negro

1 supra) are:

White

A)

O

N

O

O

C

H

O

O

O

U

N

O

O

O

O

W

O

M

N

M

W

A

W

U

L

M

I

W

O

fo

d

D

W

O

R

N

W

W

R

A

O

O

Se

d

N

W

O

O

O

H

N

W

O

I

R

O

O

Part time desegre-

gating teachers

Negro White

0 0

1 S

0 4

1 S

1 2

1 1

0 3

0 0

0 ;

0 1

0 0

0 1

0 0

4 10

40 53

0 2

1 2

C O

0 2

0 0

0 0

0 2

0 0

XH BT RX

IN HE UNITED STATES COURT Or APPEALS

POR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Nos, 28030 & 28042

tetas See SS a aes ——

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-A ppellant, L

Ve

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ef al...

Defendants- Appa) one.

(Civil Action Jo, 2075 (3))

tee tee eats rath. sient vrata ts

BUFORD A, LEE, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

Ve

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

De efendant- Appellant,

Vv,

MILTON EVANS,

Third Party

‘ Defendant-App ellee,

(Civil Action No, 2034 (1))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

. Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve.

KEMPER COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et 81.5

Defendants- App pallncs,

(Civil Action No. 1373 ¢E))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Vv.

NORTH PIKE COUNTY CONSOLIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICTE, ot al.

Defendants-Appellees.

{Civil Action No. 3807(J))

URITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Vie .

NATCHEZ SPECIAL MUNICIPAL SEPARATE |

SCHOOL, YJ ~ et al.,

J;

Defend lants -Appellees.

{Civil Action No. 11200%))

UNITED STATES OF /

)

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

MARTON COUNT UNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Defendants-

(Civil Action

et al. 3

Appellees.

“NY

ry. 2178 (H))

JOAN ANDERSON, et 22.

Plain {ty ffs-A PLY pel 1:

UNITED STATES TES OF AMERICA

Plaintiff-Intervenor-Appellant

nts,

Vv.

THE CANTON MUNICIPAL SCHOOL DISTRI

and THE MADISON COUNTY

CP, ef al., :

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No. 3700(3))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

: SOUTH PIKE COUNTY CONSO LIDATED

SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al.,

Defendants-~Appellees.

{Civil Action lo, 984 (J))

3

HOLMES COUNTY

THE

Bran or Sr te MA Set ee ain

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et

PlLaintif{fs-Appecll

Vv.

.

'

(Civil Action No. 37

Bee i se A Geet A i

al.

79(3))

ROY LEE HARRIS, ‘et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Ve.

YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUC!

Defendants-Ap

A

{Civil Action No,

~ PUN

JOHN BARNHARDT, et

VI LON

pelle

209 (W))

al.

ants,

BOARD OF EDUCATION, é&t al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

et al, ,

es.

Pratntitie-Anallante,

Ve

MERIDIAN’ SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Defendants- -4ppel lees.

{Civil Action No, 1300 (£))

[SES SS —

UNITED STATES OF AMERI CA b

et al.

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ve

NESHOBA COUNTY SCHOOL DIST

Defendants-A

RICT.,

ppelle e

(Civil Action No. 1396(E))

po a

UNITED STATES OF AMER 21CA,

al. t

So

Plai ntice - Appellant,

vi

NOXUBEE COUNTY SCHOOL DIST

Defendants-

RICT, et al.,

Appellee

{Civil Action No. 1372(E))

Pd

— eo

De

UNITED STATES oF A Ca

a “f-Appel i, ant

V.

LAUDERDALE COUNTY SCHOO] Li DISTRICT. el a) - 9 )

Defendants-Appe) lees,

(Civil Action No, 13674(F))

DIAN HUDS ON, ef al.

Plaintiffs. Appellants,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Inter venor-Appe llant,

Vv,

LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et Bhs

le De any ot

(Civil Action No, 3382(J))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

3 Plaintiff-Appe ll ant,

Ve

COLUMBIA MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL, et AL : Defendants- Appellees

(Civil Action No. 2199(@))

aaa

.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appe ellant,

Ve

AMITE COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, ‘et al;.

: Defenda ants SAPDALICES,

«(Civil Action No, 3983 (J))

Ctra em at sr mmr

URITED STATES OFF AMERIC ol

COVIRGTO!

Plaintiff-Appellant

Y.

COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al., \

Defendants-Appellees.

{Civil Action No. 214801)

LAWRENC

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR., el al.,

DE a

UNITED STATES OF AMERI A,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

Ye.

1 COUNTY Sr tyranny, et al.

efendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 2216 (H))

+e ~ Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Vv.

LSSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, etal.

4% Defendants-Appellees,

(Civil Action No. 1096 (W))

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant, Pl nt,

Ve

WILKINSON COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT, at al.,

Defendants-Appellees

(Civil Action No. 1160 (W))

a

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

A]

ve

THE ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT

DATED SCHOOL DISTRICT, and QUITMAN CONSOLIDAJ

Defendants-Appellees.

ction No, 1302(F)) (Civil Ac

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

v,

|

LINCOLN COUNTY SCHOOL, DISTRICT ef 2)

Defendants. Appellees

-e 3

4

(Civil Action No, 4294 (J))

a SL

UNLTED STATES OF AMERICA, |

Plaintiff-Appellant

Vv,

PHILADELPHIA 1 URS CIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL, DISTRICT, et i

Vl De fendants-Appellees.

(Civil Action No, 1368(E))

EEN rp ye a Qrp A FAI OY 1H ANETY R UNITED wLAILS OF AME! iC A

: a Plaintiff Apel lant,

Te. Ys * Se : : % 5 :

FRANKLIN COUNTY SCHOOL, DESI et al...

Defendants-Ap Pellees, »P

(Civil Action No. 4256 (J3))

I —hnIw

~—y— ——

Appeals from the United States District Court for the.

Southern District of Miss sissippi

(July 25, 1969) H

MODIFICATION OF ORDER

J

Before BROWN, Chief Judge, THORNBERRY and MOR GAN, Circuit Judges.

TD

PE Ly CUKI

The opinion published in the above styled case

1969 is hereby modified by renumbering former paragraph

number 7 and striking from such order y On pages 17 and 1

paragraphs 5, 6 and 7 in their entirety, and inserting i

thereof new paragraphs 5 and 6 which shall read as follo

5. If no agreement is reached, the Office of Educ:

shall present its proposal for a plan for the

district to the district court on or before Aug

11, 1969, The parties shall have ten (10) days

the date such a propos

1Tict court to file ob

ments thereto, The di

hearing on the propose

ot

suggested amendments

which conforms to

re

wa than ten (10) day

xx pired.,

A plan for the school

C g implementation by the

a n

beginning of the 1969-

court shall enter Findings

Law regarding the efficacy

5

8 approve

cons

aay PR EOL Ne . 3.1. a. 5 ed plan is filed with the

Sant nares YP? S110 ao ART IA JECLLIONE OF suggested ane

widened ade mii dt mln Tl ten? SLiYice Cour Baal nGild a

A Tan and t%7 OIL eer de 3 Ah a plan ang any oonjections

o

d

C

sha

39 ~

to immediately d

itutional

ereto, and shall enter

for

4

t court

11 be t [> effe

0 school year,

.]

F . h

Fact d an ® bb

y

b

y

~

of any plan

dey vv zl ew yr ed

stanuaxra

~

4

no 1

ctive

a

ce

2

.rict shall bes entered

ater %

for th

The

Conclusi

which is

NM Tre

Wad

plan

no later

iling objec-

for

han

e

ons

district

of

»

°

rd

>

5

poe

F

a

n

|

4

od

|

[i

ry

|

—

N

J

Vd

Ws

c.

3

~~

3

pa

r=

|

Pon

W

/

~

A

ki

o

p

Gud

sn

~

oJ )

PAN

“os

Cid

pot

~t

oy!

A

TA

y

VV.

ha

i

apm]

~~

JE

—

e

2Y

.

—

¢

-

¥

p

e

[Rel

To

:

¢

-

o

5)

fi

wed

°

3

.

prc

pi

rd

pod

7

r

N

<

a

d

pa—_4

g

5

¢

BS -

Sed

-

1;

C

~

——

WW

(0

hdl

—~

os

Sd

fro

—

N

o

w

t

i

aN

»

pet

at

"

;

i

~t 0)

49)

'

on

>.

»

-

3

©

oO

dud

5

y

prs

i

\

Vi

LJ

IS

a

>

;

ai

p

g

i

N

Ud

o

n

a

d

ore

G

i

~

N

2

J

5)

(®)

od

J

St

o

t

.

e

l

w

h

\

»%

ot

£

£5

4]

fod

-

($5)

}

¢

J,

ba)

2

(A

L

a

n

~~

si

O

=

:

(®)

~

pried

® : i

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Nos, 28030 and 28042

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Pinintiff-Apnel lang

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et ‘al,

Defendants-Appellees

(AND CONSOLIDATED CASES)

Appeals fromthe United States District Court

For the Southern District of Mississippi

MOTION IN THE COURT OF APPEALS

The United States moves this Court for an order

ahending its order of July 3, 1969 and subsequent amendments

thereto in accordance with the proposed amendment order

attached hereto.

This motion is based upon the following considera-

tions:

By letter dated August 19, 1969 ( a copy of which

is attached) to Honorable William Harold Cox, Chief Judge,

United States District Court for the Southern District

of Mississippi, Secretary Robert H. Finch of the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare requested to be permitted *

additional time during which experts of the Office of

Education may go into each school district in these cases

and develop meaningful studies in depth and recommend

terminal desegregation plans to be submitted to the Court

not later than December 1, 1969, Since Secretary Finch

3 is in the best possible position to judge the need and

capacities in the Office of Education, we respectfully

request that this motion be granted. We have filed

a

[] ¥ «

LJ

simultaneously with this motion a motion in the district

court for an order granting leave to file this motion

in this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

‘JERRIS LEONAR

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

Washington, D.C. 20530

Ia

[

August 19, 1969

Honorable Willi 3 am larold Cox

United Sta T

1 "

istrict Judge c

t

A

(

D

+

p

o

o

H

ear Judge Cox:

In accordance with an order of the United States Court of \ppeals

for the Fifth Circuit experts from the Office of Parrubion in the

on rie na Welfa e have

These terminal plans were developed, reviewed with the school

districts, and filed with the United States District Court for

the Southern District of Mississippi on August 11, 1969, as required by the Order of the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit. These terminal plans were developed under great stress in approximately three weeks; they are to be ordered for implementation

on August 25, 1069, and ordered to be implemented commencing with the beginning of the 1969-70 school year. The schools involved are to be opened for school during a period which begins two days before

August 25, 19569, and 311 are to be cpen ior school not later than

September 11, 1959,

On Ai y of iash gh

and filed by th C

Sets o re

in my capacity as

and Welfare and as the

the wltimate responsibil

Nation.

®

harged with

4 5 y

abinet officer of our government

0) e of our

3

1 t

ity for the education of the peop. g

l

£7

In this same capacity, and bearing in mind the great trust reposed in me, together with the ultimate responsibility for the education of the people of our nation, I am grave y concerned that the time allowed for the development of these terminal plans has been much too short for

educators of the Office of Education to develop os plans which

e

du

wv lement b} YT be i

-

carn

ncounte i

e UL be

4

ae O

»

alue e

\J

re

L Ww

“3

i}

0

onal 3

-~ 4.

ca’ Iu 8c

* ~

11aebl a av only

involved y=)

YR -

3 va

1] -ibd,

QQ

a

-t

~

~

~

e

d

S

o

D

.

H

T

™ } @! O

{

aR i ! JIC Lb

f3

oy A

lda LANA

~

»f ic tx

-

dis

3 %r i vy

Laan

oe

iol

3

po The id

Cor

3

42

O =

811, dr.

Hh : “a Cty

WL W Ss ~~ Ri iY

Cad. aie Da

= ’ Ll

3 ® 1

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 28030 and 23042

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-Appellant

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, et al.

Defendants-Appellees

(AND CONSOLIDATED CASES)

Appeals from the United States District Court

For the Southern District of Mississippi

AMENDED ORDER

The order of this Court dated July 3, 1969, 2s

amended by Order entered July 25, 1969, is hereby

further amended as follows:

PArdgraphs 3,4,5,6, and 7 are deleted and the

following paragraphs will substitute therefor:

3. The Boxzd, in conjunction with the Office

of Education, shall develop and present to

the District Court on or before December ie

1969, an acceptable plan of desegregation.

4. " 1f the Office of Education and a school board

agree upon a plan of desegregation, it shall

be presented to the District Court on or before

December 1, 1969. The Court shall approve

such plan unless within 15 days after submission

to the Court any party files any objection or

proposed amendment thereto alleging that the

plan, or any part thereof does not conform

to Constitutional standards.

3. 1f no agreement is reached, the Office of

Education shall present its proposal for a

r

!

H

|

i

August

[ |

: : ®

plan for the school district to. the

District Court on or before December },: 1960

The parties sholl have 13 days from the date such

8 proposed plan is filed with the District

Court to file objections or suggested amendments

thereto. The District Court shall hold a

hearing on the proposed plan and any objections

and suggested amendments thereto, and shall

promptly approve a plan which shdl conform

to Constitutional standards. The District

Court shall enter Findings of Fact and

or Conclusions of Law regarding the efficacy of

any plan which is approved or ordered to

disestablish the dual school sytem in question.

Jurisdiction shall be retained until it is

clear that. disestablishment has been achieved.

, 1969.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NOS. 28030 & 28042

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Appellant,

Vv.

HINDS COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et Bl.;

Appellees,

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, et al.,

Appellants,

VY.

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellees.

OPPOSITION TO MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO

WITHDRAW PLANS FILED BY THE DEPARTMENT

OF HEALTH, EDUCATION AND WELFARE

Private plaintiffs-appellants are advised by newspaper report

that the United States has filed or will shortly file with this

1969 in the

CQeiicsa: Motion to permit the plans filed August 11,

United States District Court for the Southern District of

Mississippi by the Office of Education, United States Department

of Health, Education and Welfare to be withdrawn; and further

seeking amendment of this court's mandate to allow the Office of

Education until December 1, 1969 to file new recommended plans of

desegregation in accordance with this court's opinion herein.

Since time is of the essence and although private plaintiffs-appellants

have never been served with any papers, we would respectfully oppose

any such relief, and would show this court:

1. The plans filed by the Office of Education in the

District Court on August 11, 1969 would, if implemented, result in

a constitutional unitary school system in each of the appellee

districts for 1969-70.

2. The plans filed by HEW were drawn only by educators, in

accordance with this court's expressed concern at the argument of

this case.

3. Private plaintiffs-appellants understand from newspaper

reports that the Honorable Robert Finch, Secretary of the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare, has approached this Court on an

ex parte basis seeking permission to withdraw HEW plans on the

grounds that, inter alia, he did not see the plans prior to their

filing.

4. The effect of permitting withdrawal of the HEW plans

already filed in the district court and allowing further time for

the filing of new plans will be to further delay realization of the AX :

Can rational rights of Negro children in Mississippi. Both private

plaintiffs-appellants and appellees have already responded to the

HEW plans and the issue of their constitutional sufficiency is now

presented to the district court for determination.

~Brr-rACcording to private plaintiffs-appellants' information

and belief, Mr. Finch seeks to withdraw the HEW plans on the

grounds that implementation of unitary systems in September 1969

will be disruptive because of longstanding patterns of resistance

to the constitutional rights of Negro citizens in Mississippi.

This is clearly the meaning of his statement that Mississippi is

unprepared because it has had only token desegregation of its

schools for so long a period. Were this court to permit further

delay on the basis of the Secretary's representations, it would be

acting completely contrary to the Fourteenth ..mendment and to

CoopeYy v. Aaron, 358 U,.8. 1 (1958).

6. Educators from the Office of Education have concluded that

. there is no educational or nonracial reason for postponing the

unitary system in appellee school districts. Mr. Finch's

intervention at this late date, 10 days after HEW's plans were filed,

is based on no legal or factual consideration cognizable by the

Constitution of the United States.

7. Should this court conclude, contrary to our position, that

there is some constitutionally acceptable reason for delaying full

student integration beyond 1969-70, we strongly urge that the court

nevertheless direct the district court that the other provisions of

the HEW plan such, for example as are concerned with Faculty

ET N55 bah PES

Las Eeihli

desegregation, desegregation of extracurricular activities,

including athletic competition between predominantly-white and all-

black schools, transportation, etc., be placed into effect

immediately in accordance with the original mandate of this court.

Respectfully submitted,

ah ) 7 oh :

/ 7.7 ;

/ 7 al

j #3 A ME LT fe nd / / ; /. A

Lif Pe 7 { £7 / i / ( er Sl 2 7 Sy

MELVYN R. LEVENTHAL

FRED IL. BANKS, JR.

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

538% North Farish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing Opposition

to Motion for Permission to Withdraw Plans Filed by the Department

of Health, Education and Welfare has been served upon each of the

following attorneys, by depositing true copies of same in the United

States mail, air mail, postage prepaid.

Hon. Robert E. Hauberg Hon. Robert C. Cannada

United States Attorney Ps O. Drawer 1250

Po. 0,:B0% 131 Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Hon. John M. Putnam

P.-0. Boxy 2075

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Hon. Howard 1L,. Patterson, Jr.

P. O. Boy 808 :

Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39401

Hon. L. P. Spinks

DeKalb, Mississippi 39238

Hon. R. Brent Forman

P. O. Box 1377

Natchez, Mississippi 39120

Hon. Philip Singley

203-04 Newsom Building

Columbia, Mississippi 39429

Hon. W. 5S. Cain

133 South Union Street

Canton, Mississippi 39046.

Hon. Robert S. Resves

P. OO. Box S98

McComb, Mississippi 39648

Hon. William B. Compton

P.O. Box 845 : :

Meridian, Mississippi 39301

Hon. Herman Alford

424 Center Avenue

Philadelphia, Mississippi 39350

Hon. Ernest L. Brown

Macon, Mississippi 39341

Hon. Maurice Dantin

P. O00. Box 604

Columbia, Mississippi 39429

Hon. William D. Adams

P. O..Box 521

Collins, Mississippi 39428

Hon, Cary C. Bass, Jr.

P. OO. Box 626

Monticello, Mississippi 39654

Hon. M. M. Roberts

P:-0O. :BO% 870

Hattiesburg, Mississippi 39401

Hon. Thomas H. Watkins

P. OC. Box 650

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Hon. ‘John Gordon Roach

P.O. Box'506

McComb, Mississippi 39648

Hon. Richard D. Foxworth

216 Newsom Building

Columbia, Mississippi 39429

Hon. Robert Goza

Caton, Mississippi 39046

Hon. Joe R. Fancher

P. OO. Box 245

Canton, Mississippi 39046

Hon. Thad Leggett, III

P. OO. Box /

Magnolia, Mississippi 39652

Hon. Robert B. Deen, Jr.

P. OO. Box 883

Meridian, Mississippi 39301

Hon. Laurel CG. Weir

P. O.. Box 150

Philadelphia, Mississippi 39350

Hon. Harold W. Davidson

Carthage, Mississippi 39051

Hon. J. D. Gordon

Liberty, Mississippi 39645

Hon. John K. Keyes

Collins, Mississippi 39428

Hon. A. F. Summer

Attorney General

New Capitol Building

Jackson, Mississippi 39205

Hon. Charles Clark

Cox, Dunn & Clari,

Attorneys at Law

Deposit Guaranty National Bank

Building ~- Suite 1741

Jackson, Mississippi 39201

Hon. J. Wesley Miller

401 Pine Street

Rolling Fork, Mississippi 39159

Hon. Henry WwW, Hobbs, Jr.

P. OO. BOX 356

Brookhaven, Mississippi 39601

Hon. Calvin R. Xing

106 Mulberry Street

Durant, Mississippi

Bon. Thomas RB. Campbell, Jr.

P. 0. Box 35

Yazoo City, Mississippi YO

Hon. John C. Satterfield

P. O. Box 466

Yazoo City, Mississippi

Hon. Robert E. Covington

Jeff Carter Building

Quitman, Mississippi

Hon. David D. Gregory

Attorney

Department of Justice

D.C.

U.S.

Washington, 20530

“Hon. Herman C. Glazier

506 Walnut Street

Rolling Fork, Mississippi 39159

Hon. Richard T. Watson

Woodville, Mississippi 39669

Hon. Charles H. Herring

Meadville, Mississippi 39653

Hon. G. Milton Case

114 West Center Street

Canton, Mississippi

Bon. Walter R. Byridgforth

P. O. Box 48

Yazoo City, Mississippi

Hon. J. E. Smith

111 South Pearl

Carthage, Missis

+ Stre

Sippil

Hon, Tally D. Riddell

P. OO. Box 199

Quitman, Mississippi

; I ®

1

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

YOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NUMBERS 28030 and 28042

BEATRICE ALEXANDER, ET AL | PLAT NTIFFS~-APPELLANTS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 3779(J)

HOLMES COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL DEFENDANT-APPELLEES

ROY LEE HARRIS, ET AL PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 1209 (W)

YAZOO COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

YAZOO CITY MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL DISTRICT

HOLLY BLUFF LINE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT DEFENDANT~APPELLEES

DIAN HUDSON, ET AL PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS x

U.S.A. PLAINTIFF~INTERVENOR~-

APPELLANTS

VS. CIVIL, ACTION NO. 3382 (J)

LEAKE COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL : DEFENDANT-APPELLEES

JEREMIAH BLACKWELL, JR., ET AL PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 1096 (W)

ISSAQUENA COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION, ET AL DEFENDANT S-APPELLEES

CHARLES KILLINGSWORTH, ET AL PLAINTIFF-APPELLANTS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. 1302(%)

THE ENTERPRISE CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT

AND QUITMAN COLSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT DEFENDANT S~-APPELLEES

N

To. - * ' .

; » ®

’ »

MOTION BY THE DEFENDANTS IN THE ABOVE STYLED CONSOLIDATED

CASES JOINING IN THE MOTION THEREIN FILED BY THE ATTORNEY

GENERAL OF THE UNITED STATES IN BEHALF OF SECRETARY

ROBERT H. FINCH OF THE DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION

AND WELFARE AND THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Now come all of the defendants in the above styled consolidated

cases and join in the Torin filed therein by the Attorney General of

the United States entitled "UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PLAINTIFF-

APPELLANT HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL, DEFENDANTS-APPELLEES (AND

CONSOLIDATED CASES) -- MOTION IN THE COURT OF APPEALS" filed in this

Court on or about August 21, 1969, and show to the court the following:

l. This motion is filed in the United States Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit by permission of the United States District Court

for the Southern District of Mississippi granted on open court and made

of record therein.

2. That the said motion thus filed in this Court on or about

August 21, 1969, was filed in the consolidated proceedings numbered

upon the docket of this Court as "Nos. 28030 and 28042", particularly

referring to the first listed case of the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA VS.

HINDS COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD, ET AL and particularly being filed not only

applicable to said case but applicable to it "AND CONSOLIDATED CASES".

3. That there were appealed to this Court and assigned the

above docket numbers twenty-five school desegregation cases involving

a total of thirty-three soho) districts. That the said twenty-five

consolidated cases included those listed above in which this Motion of

Joinder is filed.

4. That in the opinion and mandate of the Court of Appeals

dated July 3, 1969, the following findings were made:

These are twenty-five school desegregation cases

in a consolidated appeal from an en banc decision

of the U. S. District Court for the Southern

District of Mississippi . . + &

LJ «

] p :

’

The order of the District Court in each case is

reversed and the cases are remanded to the

District Court with the following direction:

l. These cases shall receive the highest priority.

2. . The District Court shall forthwith reguest that