Brown v. Board of Education Brief of John Ben Shepperd, Attorney General of Texas, Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Brief of John Ben Shepperd, Attorney General of Texas, Amicus Curiae, 1954. bf3ae9db-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21a88766-7b72-4d0b-bf11-ee720c5da669/brown-v-board-of-education-brief-of-john-ben-shepperd-attorney-general-of-texas-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

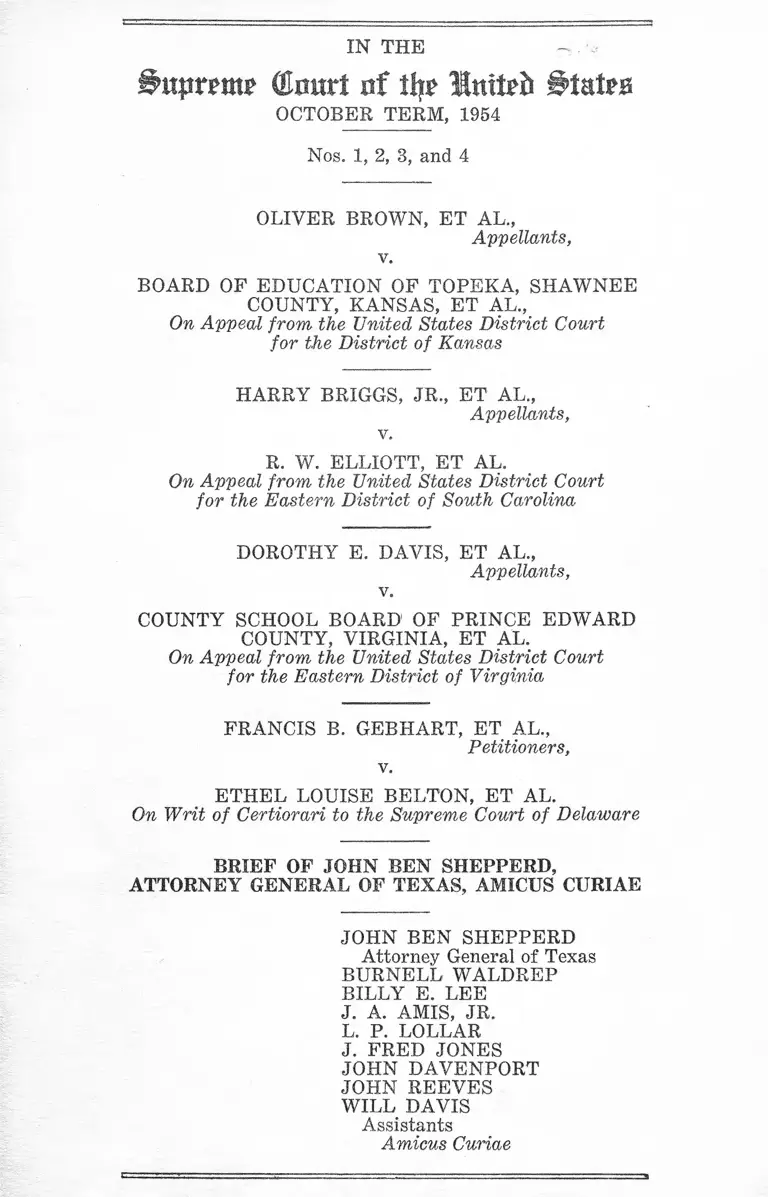

IN THE

€msrl nf tfa States

OCTOBER TERM, 1954

Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4

OLIVER BROWN, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.,

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Kansas

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

R. W. ELLIOTT, ET AL.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of South Carolina

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

v.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware

BRIEF OF JOHN BEN SHEPPERD,

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TEXAS, AMICUS CURIAE

JOHN BEN SHEPPERD

Attorney General of Texas

BURNELL WALDREP

BILLY E. LEE

J. A. AMIS, JR.

L. P. LOLLAR

J. FRED JONES

JOHN DAVENPORT

JOHN REEVES

WILL DAVIS

Assistants

Amicus Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTSl

Page

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT-___________________ 2

Variance of Degree in Which Different Areas

Would be Affected_____________________________ 6

Texas Public School System______________________ 9

QUESTION FOUR________________________________ 12

Argument_______________________________________ 12

QUESTION FIVE_________________________________ 24

Argument ______________________________________ 25

CONCLUSION ____________________________________ 28

APPENDICES

APPENDIX I

Map showing concentration o f Negro population

by counties as shown by the 1950 Federal census.

APPENDIX II

Map showing the number and percentage of

Negro scholastics in each county as shown by the

1954-1955 scholastic census.

APPENDIX III

Map showing the concentration of Negro scholas

tics in general areas, as shown by the 1954-1955

scholastic census.

APPENDIX IV

Questionnaire and evaluated answers relating to

views of public school administrators on the prob

lems involved in integration.

APPENDIX V

Alphabetical listing of counties, showing relation

ship of Negro to white scholastics as based on

the 1954-1955 scholastic census.

i.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Addison v. Holly Hill Co., 322 U.S. 607 (1944)_____ 27

Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern Rail

way Company, 341 U.S. 341 (1951)---------------------- 22

Barbier v. Connolly, 113 U.S. 27 (1885)----------------- 23

Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624 (1942) 26

Burford v. Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315 (1943)_______ 22

Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education,

175 U.S. 528 (1899)_____________________________ 3

Far Eastern Conference, United States Lines Co.,

States Marine Corporation, et al. v. United States

and Federal Maritime Board, 342 U.S. 570 (1952) 22

Georgia v. Tennessee Copper Co., 240 U.S. 650 (1916) 21

Hatcher v. State, 125 Tex. 84, 81 S.W. 2d 499 (1935) 14

International Salt Company v. United States, 332

U.S. 392 (1947)_________________________________ 27

Love v. City of Dallas, 120 Tex. 351, 40 S.W. 2d 20l

(1931) _________________________________________ 14

Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586

(1940) _________________________________________ 26

New Jersey v. City of New York, 283 U.S. 473 (1931) 21

Northern Securities Company v. United States, 193

U.S. 197 (1904) _________________________________ 21

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896)____________ 3

Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman Company,

312 U.S. 496 (1941)_____________________________ 21

Southwestern Broadcasting Company v. Oil Center

Broadcasting Company, 210 S.W. 2d 230 (Tex. Civ.

App,, 1947, error ref. N .R.E.)_____________________ 13

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1 (1911) 21

United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221 U.S. 106

(1911) _________________________________________ 20

ii.

A uthorities

Page

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542 (1876) ___ 5

United States v. Paramount Pictures, 334 U.S. 131

(1948) --------------------------------------------------------------- 22

University Interscholastic League v. Midwestern Uni

versity, ___Tex_____, 255 S.W. 2d 177 (1953)_____ 13

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTION:

Texas Constitution (Vernon 1948) Art. VII, Sec. 1__ 25

Texas Constitution (Vernon 1948) Art. VII, Sec. 7__ 2

Texas Civil Statutes (Vernon 1948) Articles 2745,

2749, 2775, 2780._________________________________ 13

Texas Civil Statutes (Vernon 1948) Articles 2750a,

2781 ____________________________________________ 14

Texas Civil Statutes (Vernon 1948) Article 2784e__ 13

Texas Civil Statutes (Vernon 1948) Article 2786__ 13

Texas Civil Statutes (Vernon Supp. 1950) Article

2922-11 et seq ._____________________________ 9

MISCELLANEOUS:

Texas Poll, September 12, 1954______________________ 16

Texas State Board of Education Resolution, July 5,

1954 ___________________________________________ 19

The Dallas Morning News, June 9, 1954_____________ 14

U. S. News and World Report, August 27, 1954_____ 10

iii.

IN THE

ffruprm? (Cmirt nf thr Inttrii States

OCTOBER TERM, 1954

Nos. 1, 2, 3, and 4

OLIVER BROWN, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA, SHAWNEE

COUNTY, KANSAS, ET AL.,

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of Kansas

HARRY BRIGGS, JR., ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

R. W. ELLIOTT, ET AL.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of South Carolina

DOROTHY E. DAVIS, ET AL.,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF PRINCE EDWARD

COUNTY, VIRGINIA, ET AL.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia

FRANCIS B. GEBHART, ET AL.,

Petitioners,

v.

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON, ET AL.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Delaware

BRIEF OF JOHN BEN SHEPPERD,

ATTORNEY GENERAL OF TEXAS, AMICUS CURIAE

■2-

TO THE HONORABLE SUPREME COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES:

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

John Ben Shepperd, Attorney General of Texas,

pursuant to request for leave to appear amicus curiae

and file a brief, submits this amicus curiae brief to

the Court upon the condition that such appearance

will not have the effect of making the State of Texas

or any of its officers or agencies parties to this litiga

tion.

In compiling data for this brief a sincere effort

has been made to obtain a correct cross section of

views of educators, legislators and others with knowl

edge of the subject matter under consideration. Sur

veys have been made, public opinion has been sam

pled, and composite views of groups best acquainted

with the segregation problem have been obtained.

The Texas Education Agency has been most helpful

in furnishing pertinent materials which have been

used in this brief. We will attempt to present the

true Texas picture as reflected from this research.

The public school system in Texas from its incep

tion has been operated and maintained on a segre

gated basis, and has existed for more than eighty

years under the authority of Section 7 of Article VII

of the Texas Constitution (1876)1 and statutes en

acted pursuant thereto. This constitutional and stat

utory authority creating separate but equal facilities

1 Section 7 of Article VII o f the Texas Constitution pro

vides : “ Separate schools shall be provided for the white and

colored children, and impartial provision shall be made for

both.”

in the public school system of Texas was the direct

and continuing result of the expressed will of the

people of Texas. This Honorable Court in many of

its decisions has held that the states may provide

education at their own expense for the white and

Negro students in separate schools so long as equal

facilities and advantages are offered both groups.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896), and related

cases. Stability and harmony in the law, particularly

in the constitutional law, is a primary requirement

in an effective and efficient government. When the

courts have announced, for the guidance and govern

ment of individuals and the public, certain con

trolling principles of law, they should not be changed,

because the law by which men are governed should be

fixed, definite and known, particularly when millions

of dollars have been spent in reliance thereon. At

tending a public free school is a privilege extended

by the state. It is not a right of a citizen of the United

States. Gumming v. Richmond County Board of Edu

cation, 175 U.S. 528, 545 (1899). So long as the

privileges extended to all groups are equal no one

is deprived of the equal protection of the law. The

decisions of this Honorable Court have recognized

that, where necessity exists, the teaching of white

and Negro students in separate classrooms is a rea

sonable exercise of the state’s police power. To pre

serve the public peace, harmony and the general wel

fare, the people of Texas in their Constitution, and

the Legislature by statutes have declared that such

a necessity exists in Texas. There is no discrimina

tion on the part of the State of Texas in administer

ing its public school system, only separation of the

4-

races. It is the belief of the people of this State that

discrimination against the individual can best be

eliminated by segregation of the races in the educa

tional system. It is the evil of discrimination and not

segregation per se that is condemned by the United

States Constitution.

Section 7 of Article VII of the Texas Constitution

and related statutes provide that the State shall fur

nish equal education to its Negro and white students.

The State of Texas has been operating under the as

sumption that the power of states so to classify and

the reasonableness of the classification had been

settled as a matter of law since 1896 and was not

violative of the equal protection clause of the Four

teenth Amendment.

{However, if the occasion arises whereby we are

compelled to abolish segregation in Texas, it should

be by a gradual adjustment in view of the complexi

ties of ‘ the problem.f Such complexities include the

unwillingness of tEe Texas people immediately to

abide by the decision, the varying degrees in which

different areas of the State of Texas would be af

fected, and the result such a decision would have on

the State’s public school system which has been main

tained on a segregated basis for generations.

Legal action which bears upon the folkways of

nearly one-fourth of the nation’s population cannot

be effective unless the affected group is largely will

ing to abide by it. No individual can be forced against

his will to accept, associate, or cohabit with another

not of his own choosing. The Fourteenth Amendment

to the United States Constitution prohibits only

“State action” which is discriminatory because of

race, creed or color, not the prejudices or discrimina

tion evidenced by individuals toward their fellow

man. United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542

(1876). And while it has been determined that equal

but separate facilities maintained in the public free

school systems of the states involved in this litiga

tion is “ State action” in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, still this Court should consider that

such a decision also affects the individual rights,

mores and beliefs of the Southern people. To insure

that the people of the South accept the decision and

make moral decisions of their own commensurate

with the end of bettering the Negro race, some way

must be found to protect the constitutional rights

of the minority without ignoring the will of the ma

jority. The underlying thought implicit in the Court’s

decision in these cases is that a feeling of inferiority

is generated in the Negro child, resulting not from

actual attendance in a segregated school, but from

the legal requirement under which the Negro child

is forced to attend separate schools. From the stand

point of principle, there is no real difference between

compulsory segregation and compulsory integration.

Compulsion can only arouse resentment, individual

discrimination, and, as experience has demonstrated

in other states, violence. The objectives reached by

the War between the States left a scar of bitterness

and resentment that is visible even now in some parts

of the South. Such, we hope, will not be the result of

this Court’s May 17th decision.

Variance of Degree in Which Different Areas

Would Be Affected

In order that this Honorable Court have the full

assistance of all parties and amici curiae in formu

lating decrees, these cases were restored to the docket

for the presentation of further argument upon the

following questions:

“4. Assuming it is decided that segregation

in public schools violates the Fourteenth Amend

ment

(a) would a decree necessarily follow pro

viding that, within the limits set by normal

geographic school districting, Negro children

should forthwith be admitted to schools of their

choice, or

(b) may this Court, in the exercise of its

equity powers, permit an effective gradual ad

justment to be brought about from existing seg

regated systems to a system not based on color

distinctions?

5. On the assumption on which questions 4

(a) and (b) are based, and assuming further

that this Court will exercise its equity powers

to the end described in question 4 (b ),

(a) should this Court formulate detailed de

crees in these cases;

(b) if so, what specific issues should the de

crees reach;

(c) should this Court appoint a special mas

ter to hear evidence with a view to recommend

ing specific terms for such decrees;

(d) should this Court remand to the courts

of first instance with directions to frame de

crees in these cases, and if so, what general di

rections should the decrees of this Court include

and what procedures should the courts of first

instance follow in arriving at the specific terms

of more detailed decrees?”

The following factual information is submitted

which we believe to be pertinent insofar as the State

of Texas is concerned.

The State of Texas has a total population of seven

million, seven hundred eleven thousand, one hundred

ninety-four (7,711,194), of whom nine hundred

seventy-seven thousand, four hundred fifty-eight

(977,458), or 12.7%, are colored.2 The concentration

of the Negro population is shown by counties on the

map designated “Appendix I.” There are one million,

seven hundred eighty-six thousand, nine hundred

eighteen (1,786,918) persons of scholastic age enum

erated in the scholastic census for the 1954-1955

school year, of whom two hundred thirty thousand,

five hundred forty-six (230,546), or 13%, are col

ored. The concentration of the Negro scholastic popu

lation is shown by counties on the map designated

“Appendix II.” Texas has two hundred fifty-four

(254) counties. There are located in the northeastern

forty-five counties of this State 50% of the colored

scholastics of Texas, and in four of these counties the

Negro scholastics comprise a majority of the coun

ty’s scholastics. In the forty-three counties adjacent

to and immediately west of the northeastern block of

counties above referred to, another 40% of the col

ored scholastics reside. Thus, in Texas today ap

2 This population is based on the 1950 Federal Census.

proximately 90% of the total Negro scholastics are

located in the eighty-eight counties comprising the

northeastern quadrant of the State. Forty-one Texas

counties do not list a single Negro scholastic. There

fore the remaining 10% of the colored scholastics of

Texas are scattered throughout the remaining one

hundred and twenty-five counties. A map evidencing

this factual information is attached and designated

“ Appendix III” , to which particular reference is

made. A study of this map reveals that the segrega

tion problem in Texas is not state-wide, but is of

serious import and of vital concern to our local school

districts.

Of the two hundred and thirteen Texas counties

listing Negro scholastics, one hundred forty-six coun

ties offer a complete Negro high school, twenty-one

counties offer some Negro high school, but not twelve

grades, and thirty-six counties offer only Negro

elementary school. Ten counties operate no school for

Negroes; however, these counties have ten or fewer

Negro scholastics. Negro scholastics in counties not

having a complete twelve grades are transported at

State expense to other schools. Texas in 1953-54 had

a total of one thousand, nine hundred fifty-three

(1,953) active school districts, two hundred ninety-

two (292) of which offered a full twelve grade school

for both white and Negro. One hundred twenty-five

(125) districts maintained a Negro school but did

not have a white school. A total of nine hundred fifty-

six (956) districts provided Negro schools. The dis

tricts that did not maintain a school for Negroes

were primarily in areas that did not contain Negro

scholastics.

— 9—

Texas Public School System

Pursuant to the constitutional authority, the Texas

public school system is administered under what is

commonly called “ The Minimum Foundation School

Program.” 3 Under this very effective program, edu

cation of the Texas school child is provided on an

equal but separate basis, with millions of dollars be

ing spent each year. Under the Minimum Foundation

Program, as administered by Texas’ twenty-one-

member elective State Board of Education, all pos

sible control and responsibility are left to local school

administrators and local school boards to provide

school programs to meet the needs of the children

in their communities. As the name implies, the Mini

mum Foundation Program guarantees to every

school-age child in Texas, regardless o f race, creed,

color, economic status or place of residence, at least

a minimum of a full nine months of schooling each

year, thereby spreading the State’s financial re

sources available for public education as equally as

possible among all the people. The Program has been

in effect for five years, and during that time the aver

age daily attendance of school-age children actually

attending school has risen from 73.77% in 1948-49

to 80.85% during 1953-54. 79.31% of the Negro

school-age children were in average daily attendance

in 1953-54.

The Minimum Foundation Program provides a

system of financing which guarantees to local school

districts that State funds will be available to pay the

Art. 2922-11, et seq., Tex. Civ. Stat. (Vernon’s, 1948).

- 1 0 -

cost of a minimum school program when local funds

are insufficient.

A number of the Texas school districts do not need

a supplemental appropriation from the Legislature.

A majority of the Texas schools have surplus money

derived from local taxation with which to enrich the

local school program beyond the minimum program

prescribed by the State. Expenditures from surplus

funds provide adult and kindergarten classes for

students not included in the scholastic census age

brackets, classes for exceptional children, supple

mental expenditures on salaries, maintenance and

capital costs, and any other authorized school costs.

The State funds are provided in proportionate equal

ity to all school districts, for the benefit of all scholas

tics, irrespective of race, creed or color. If a school

program superior to the minimum requirements is

desired in any district, it may be paid for by the

taxes voted, levied and collected from the taxpayers

of the district.

As a result of the Minimum Foundation Program,

teachers’ and school administrators’ salaries have

risen from twenty-ninth in the nation to sixteenth.

97.1% of the Texas teachers now have college de

grees. Only the State of Arizona exceeds this mark.

There are approximately eight thousand, five hun

dred (8,500) Negro teachers and school administra

tors in Texas. This number is nearly equal to the

total number of Negro educators in the thirty-one

Northern and Western States which practice non

segregation. According to the U. S. News and World

Report, August 27, 1954, only one out of every

seventy-three teachers in those thirty-one states

— 11— -

maintaining an integrated system is a Negro, while

in Texas, one out of every five is a Negro. These posi

tions are believed to be the most secure and best paid

employment the Negro has today. The effect of this

decision upon the teaching profession is speculative,

and any decree which would disrupt the stability and

security of teachers should be avoided.4

Under the Minimum Foundation Program, the

public school system of Texas has greatly raised its

standards, teachers have been benefited by salary in

creases and retirement plans, and every school-age

child in Texas, without regard to his race, creed or

color, has been offered the opportunity of education.

The State has not discriminated in its appropria

tions, such being provided equally to all races and

persons, with the privilege and authority in each

local district to go further if it is so desired. But the

program does provide for separate schools, segregat

ing the races and contemplating an equalization of

facilities for all scholastics. Integration would re

quire alteration of the Minimum Foundation Pro

gram.

The establishment of an integrated system is not

a problem which would apply equally to West or

South Texas, where there is only a small percentage

of the Negro population, and to Northeast Texas,

where the concentration of the Negro population is

the heaviest. No equitable general decree could ever

be formulated for the entire State of Texas. Specific

decrees could be made only after a particular school

4 Texas at the present time has no tenure statute for

teachers in the public free schools. Employment is through

the local school boards.

12—

district was before this Court and the facts relevant

to that district were presented. It would be impos

sible to get enough facts before the Court in one

isolated case upon which the Court could enter a

general decree which would apply equally to all parts

of this State or to all the states practicing segrega

tion. Since we do not know the various fact situa

tions as they exist in these cases, we are in no posi

tion to advise the Court as to the type of decree that

should be entered.

QUESTION FOUR

4. Assuming it is decided that segregation in

public schools violates the Fourteenth Amendment

(a) Would a decree necessarily follow

providing that, within the limits set by

normal geographic school districting, Negro

children should forthwith be admitted to

schools of their choice, or

(b) May this Court, in the exercise of its

equity powers, permit an effective gradual

adjustment to be brought about from exist

ing segregated systems to a system not

based on color distinctions?

Argument

This Court has recognized the complexities in

volved in the formulation of a decree in these cases

because problems of different characteristics are pre

sented. Evidently all states were invited to appear

— 13—

because each should have an opportunity to demon

strate the obstacles to adjustment in compliance with

any decision that might be rendered in the future

affecting the individual states.

It is respectfully submitted that this Court is au

thorized to permit an effective gradual adjustment

toward integration and, unquestionably, if the oc

casion arises, the administration of this program in

Texas must be left to the local school districts. The

education system in Texas is predicated upon a num

ber of local, self-governing school districts, with full

authority to administer the school system. The basic

and historic concept of public free schools is based

upon the democratic and salutary principle of local

self-government. The schools in Texas are operated,

maintained and controlled by local school boards

elected by the people of the individual school district.5 6

Operational and maintenance costs are provided by

local taxation voted by the taxpayers of the district6

and supplemented by the Legislature under the Mini

mum Foundation Program.7 Capital expenditures

are made through bond issues voted by the taxpayers

of the district.8 All personnel of the school, with the

exception of the elected officials, are employed by local

5 Southwestern Broadcasting Company v. Oil Center

Broadcasting Company, 210 S.W. 2d 230 (Tex. Civ. App.,

1947, error ref. N.R.E.) ; University Interscholastic League

v. Midwestern University, ___ Tex. ___, 255 S.W. 2d 177

(1953) ; Arts. 2745, 2749, 2775 et seq., and 2780, Tex. Civ.

Stat. (Vernon’s, 1948).

6 Art. 2784e, Tex. Civ. Stat. (Vernon’s, 1948).

7 See discussion of the Texas Public School System in this

brief.

8 Art. 2784e and Art. 2786, Tex. Civ. Stat. (Vernon’s,

1948).

- — 14- —

officials and work under such officials’ supervision.9

It is thus seen that the schools in Texas constitute

almost a complete local autonomy controlled by the

taxpayers of the individual school districts and their

locally elected school board. In fact, the courts of

Texas have repeatedly held that these school districts

are local public corporations of the same general

character as municipal corporations.10 Any decree of

the Court that might affect Texas must leave this

administration in the local school districts unham

pered. The problems with which we are confronted

can best be resolved at the local level in this manner.

As a basic premise for showing the need for a tran

sition period, the following is typical of the feeling

of Texas citizens and school administrators on the

vital subject now before this Court.

In an article appearing in The Dallas Morning

News on June 9, 1954, Dr. J. W. Edgar, Texas Com

missioner of Education, stated:

“ Texas has 2,000 problems as a result of the

Supreme Court’s decision. We have 2,000 school

districts, and they vary from totally white to

totally Negro.

“ The final decree by the Court ought to per

mit continued management of local districts by

local boards. Schools must be run on a commun

ity basis. They can’t be run successfully from

Washington or even from Austin (Texas).

“ Experience in separating children on a lan

guage basis has proved to us that where the re

9 Art. 2750a and Art. 2781, Tex. Civ. Stat. (Vernon’s,

1948).

10 Hatcher v. State, 125 Tex. 84, 81 S.W. 2d 499 (1935) ;

Love v. City of Dallas, 120 Tex. 351, 40 S.W. 2d 20 (1931).

15—

sponsibility is put upon the local community,

they work honestly to resolve differences.

“Anything which schools do effectively must

be done with local support. We don’t care to tell

others how to run their schools, but we certainly

believe that our 2,000 problems can be resolved

best if the Supreme Court leaves control in local

districts.”

In a statement made to the Texas Commission on

Higher Education, Dr. R. O’Hara Lanier, Negro

president of Texas Southern University, stated:

“ In spite of the U. S. Supreme Court’s anti

segregation ruling, Negro schools will be needed

more than ever in the future. It would be a nar

row position for the state to get rid of Negro

schools for if the Negroes are given equal fa

cilities there is nothing to worry about from seg

regation.

“ For many years to come there will be shown

a great desire and preference on the part of the

Negro student to attend an institution equal in

every respect, where there will exist many op

portunities for development for qualities of

leadership and where full participation in every

phase of college life will be assured.

“ Because of human behavior and social back

grounds and patterns long existent, the large

majority of such students will come to us (the

Negro schools) because they prefer to do so.

_ “ Such students very likely will prefer to con

tinue to study with homogeneous groups and

will feel strongly that more sympathetic atten

tion will be given to them in our institutions

than in some other schools.”

Dr. E. B. Evans, Negro president of Prairie View

A. & M. College, expressed similar views to the Com

mission.

— 16—

(_The latest state-wide survey of the Texas Poll11

on September 12, 1954, indicates:

“ 1. 71% of the Texas people are definitely op

posed to the Supreme Court’s decision. The

breakdown on the decision is like this:

Approve Disapprove Undecided

Negroes 60% 33% 7%

Latins 49% 37% 14%

Other Whites 15% 80% 5%

Entire Public 23% 71% 6%

“ 2. What should be done about the problem?

7 % favor putting the Court’s ruling into effect

immediately, and another 23% believe plans

should be made to bring the races together in

the schools within the next few years. A ma

jority of 65% goes on record in favor of con

tinued segregation notwithstanding the Court’s

decision. The breakdown on this problem is:

Go Pew Keep Un

Now Years Apart decided

Negroes 27% 40% 26% 7%

Latins 20% 37% 33% 10%

Other Whites 3% 19% 74% 4%

Entire Public 7% 23% 65% 5%

In the entire public, Negroes account for about

12% of the population; Latins, about 11%; and

other whites, about 77%.”

In a recent questionnaire forwarded by the At

torney General of Texas to approximately one hun- 11

11A long-established Texas organization operated by Joe

Belden who periodically and systematically conducts a scien

tific sampling, or polling, and reporting thereon, of public

opinion in Texas on current events.

— 17—

dred fifty-two Texas school administrative officials,

seventy-seven reported that 85% or more students

would continue attending the same school if they

had free choice. Of this number, fourteen answers

were from Negro administrators. Only three an

swered that students in their districts would prefer

attending integrated schools, and all three reports

were from Negro administrators. The questions pro

pounded and the answers received by the Attorney

General are compiled in a report which is attached as

“Appendix IV.”j

Many plans have been advanced to alter the public

school system of Texas as a result of the May 17th

decision. Some go so far as to suggest the complete

abolition of the free public school system, while

others advocate turning the State schools into pri

vate schools. The decision of the United States Su

preme Court is to the effect that segregation in public

schools maintained by compulsion of law is uncon

stitutional as being in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Many suggest that it does not neces

sarily follow that integration of the white race with

the colored race in the field of education is compelled

by the Constitution. If, under the Fourteenth Amend

ment, all citizens are entitled to equal protection of

the law, which was the premise for the Supreme

Court’s decision, then integration can no more be

compelled than can segregation. Provision for do

mestic tranquility in the exercise of the police pow

ers of the State premised the original laws requiring

segregation. To maintain public peace, good order

and the domestic tranquility, these same police pow

■18—

ers of the State could be exercised, calling for another

and different provision relating to public education.

Realizing this, and that the need for compulsion no

longer exists, another plan suggests that the section

of the law which provides for compulsory education

should be repealed and the laws providing that the

State furnish free education to all should be left

undisturbed. Then the present laws should be

amended to allow the parent or guardian of the child

desiring to take advantage of free education to ex

press his own desires and preferences as to the type

of school the child should attend. The parent or

guardian could select a school in which the majority

of the other pupils are of the same race as the child,

or he could select a school in which the other pupils

are of both races, thereby providing equality of op

portunity and freedom of individual choice.

This change would remove the unconstitutional

“ compulsion” of segregation, and at the same time

the State would be in a position of honoring the in

dividual preferences of its people.

Another plan advanced is that of allowing volun

tary transfers between school districts, and it is

based upon the same principle as the foregoing.

In complying with the mandatory duties placed

upon the Legislature of the State of Texas by the

Constitution of the State of Texas, the Legislature

has by general law established, supported and main

tained a segregated public free school system. These

laws of the State of Texas are not before the Court

in these causes, and the State Board of Education has

ruled that the schools of Texas should continue to

be operated in the same manner until otherwise di

— 19—

rected.12 Since the end of World War II, Texas, to

gether with many of our states, has been confronted

with the enormous task of providing adequate school

housing for a shifting and rapidly increasing popu

lation. In areas predominantly populated by white

students schools have been built to house these stu

dents. In areas predominantly populated by colored

students schools have also been built to house them.

Utilization of all present school housing to the fullest

extent in this State will be an absolute necessity.

Texas is also confronted with the difficult problem

of providing adequate facilities for the anticipated

increase in its scholastics in the interim between now

and 1960. Statistics reveal that at the close of the

1958-1959 school year, eight hundred forty-nine mil

lion, three hundred forty-four thousand, nine hun

dred twenty-two dollars ($849,344,922) will be

needed over and above the present needs to care for

the increase in population and replacement costs on

existing facilities. Of this amount, only three hun

dred ninety-four million, eight hundred fifty-eight

thousand, fifty-two dollars ($394,858,052) can be

anticipated from local funds, leaving a balance of

four hundred fifty million, four hundred eighty-six

12 On July 5, 1954, the State Board of Education passed

the following resolution: “ Since the recent United States

Supreme Court’s decisions on segregation in public schools

are not final, the State Board of Education of Texas is of

the unanimous opinion that it is obligated to adhere to and

comply with all of our present state laws and policies provid

ing for segregation in our public school system and to con

tinue to follow these present laws and policies until such

time as they may be changed by a duly constituted authority

of this State. If in the future, the Texas laws should be

changed then each local district should have sufficient time

to work the problem out. . . .”

- 2 0 -

thousand, eight hundred seventy dollars ($450,486,-

870) which must be derived from another source to

care for the needs of the school children for the school

year of 1960. The school system is presently over

crowded with certain school-age groups being sep

arated into morning and afternoon classes to offset

this condition. It can readily be seen that if Texas

attempted an immediate integration, the perplexi

ties confronted in accomplishing the same would be

overwhelmingly multiplied. Additional facilities are

needed and will have to be supplied by local bond

issues. It is highly speculative as to whether such

bond issues would be voted to house an integrated

school system which an overwhelming majority of

the people oppose. The election calls for freedom of

choice and no mandamus action could be maintained

to force an affirmative vote. At this time it would be

highly impracticable to eliminate any of the present

school housing, and great consideration must be given

to the natural and presently existing boundary lines

which, of course, is the prime consideration for the

Legislature or the local school board.

A gradual transition to an integrated public school

system is not a denial of relief or of the constitu

tional rights enunciated by the Court. The Court has

previously permitted a transition period in analogous

situations, particularly in the antitrust and nuisance

cases. In United States v. American Tobacco Co., 221

U.S. 106 (1911), the Supreme Court determined that

the defendant had violated the Sherman Anti-Trust

Act. Recognizing the need for adjustment to its de

cree, the Court, in order to avoid and mitigate any

possible injury to the interest of the general public,

■21

remanded the case to the lower court to hear the par

ties and to ascertain and determine a plan for dis

solution of the combination. To accomplish this end,

the Court allowed sufficient time (eight months) to

carry out its decree. In Georgia v. Tennessee Copper

Co., 240 U.S. 650 (1916), the Court entered a final

decree in a case in which the State of Georgia had

sued the Tennessee Copper Company to restrain the

discharge of irritating gases into Georgia. The case

had involved three lawsuits and covered a span of

nine years in which the Court allowed considerable

time and discretion to devise ways and means of

subduing and preventing the escape of the noxious

fumes. In Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pullman

Company, 312 U.S. 496 (1941), the Pullman Com

pany brought suit in the Federal Court against the

Railroad Commission of Texas attacking a regula

tion of the Commission as being in violation of the

Federal Constitution and unauthorized by the Texas

statutes. The Court remanded the case to the lower

court, with directions to retain the bill pending a

determination of proceedings, to be brought within

a reasonable time in the state court to determine a

definite construction of the state statute.13

The use of administrative discretion and its limits

has been spelled out often by the Court in the areas

of administrative agencies. The Court has empha

sized consistently that supervision and discretion

should lie with the administrative agencies in con

ducting their functions as economic and political gov

13 See also: New Jersey v. City o f New York, 283 U.S. 473

(1931) ; Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1

(1911) ; Northern Securities Company v. United States, 193

U.S. 197 (1904).

— 22—

erning boards.14 Such emphasis is closely related also

to the administrative discretion which exists in

school boards. In United States v. Paramount Pic

tures, 334 U.S. 131 (1948), Mr. Justice Douglas re

viewed a decree in an injunction suit by the United

States under the Sherman Act to eliminate or qualify

certain business practices in the motion picture in

dustry. A provision in the decree that films be li

censed on a competitive bidding basis was eliminated

by the Supreme Court as not likely to bring about the

desired end and as involving too much judicial super

vision to make it effective. This elimination was held

to require reconsideration by the district court of

its prohibition of the expansion of theatre holdings

by distributors and provisions for divesting exist

ing holdings.

The Court at page 163 stated:

“ It would involve the judiciary in the admin

istration of intricate and detailed rules govern

ing priority, period of clearance, length of run,

competitive areas, reasonable return and the

like. The system would be apt to require as close

a supervision as a continuous receivership, un

less the defendants were to be entrusted with

vast discretion. The judiciary is unsuited to

affairs of business management; and control

through the power of contempt is crude and

14 See Alabama Public Service Commission v. Southern

Railway Company, 341 U.S. 341 (1951) ; Burford v.

Sun Oil Co., 319 U.S. 315 (1943) ; and Far Eastern Con

ference, United States Lines Co., States Marine Corpora

tion, et al. v. United States and Federal Maritime Board,

342 U.S. 570 (1952).

— 23—

clumsy and lacking in the flexibility necessary

to make continuous and detailed supervision ef

fective.”

The implications in the Court’s opposition to ju

dicial administration of intricate and detailed rules

in the economic field apply with greater force to the

social relationship and problems created by these

cases in the field of public education. Furthermore,

the amount of capital involved in the Paramount

case is minute when compared with the wealth in

vested in the public school systems of the South.

The Court, in Barbier v. Connolly, 113 U.S. 27

(1885), speaking of the Fourteenth Amendment,

stated at page 31:

“ But neither the amendment— broad and

comprehensive as it is— nor any other amend

ment, was designed to interfere with the power

of the State, sometimes termed its police powTer,

to prescribe regulations to promote the health,

peace, morals, education and good order of the

people. . . .” (Emphasis supplied.)

A tremendous portion of the wealth of these states

has been invested in capital expenditures for their

public schools. The only practical method of estab

lishing an integrated system calls for a period of

implementation in our present dual system. This

Court in the exercise of its equity powers has ample

authority to permit the parties to adjust gradually

from their existing segregated systems to an inte

grated one. The instant cases affect millions of indi

viduals and the entire public in some seventeen states.

By reason of the great number of people affected by

— 2 4 —

the decree and by reason of the vast amount of

money invested in capital expenditures, and because

of the necessity to make use of all present buildings

in the operation of an efficient system of public edu

cation, this Court should permit the states to adjust

their dual systems gradually into an integrated sys

tem. It is, therefore, respectfully submitted that this

Honorable Court has sufficient authority to permit

a gradual adjustment to an integrated school system

with sufficient time given for local school officials

to accomplish this purpose by the exercise of their

administrative authority.

QUESTION FIVE

5. On the assumption on which Questions 4 (a)

and (b) are based, and assuming further that this

Court will exercise its equity powers to the end de

scribed in Question 4 (b),

(a) Should this Court formulate detailed

decrees in these cases;

(b) If so, what specific issues should the

decrees reach;

(c) Should this Court appoint a special

Master to hear evidence with a view to

recommending specific terms for such de

crees ;

(d) Should this Court remand to the

courts of first instance with directions to

frame decrees in these cases, and if so, what

general directions should the decrees of this

- 2 5 -

Court include and what procedures should

the courts of first instance follow in arriving

at the specific terms of more detailed de

crees?

Argument

The information contained in the introductory

statements and in Appendix III clearly demonstrates

that the problem of establishing a public school sys

tem not based on race is a localized problem in

Texas, not a state-wide problem. This is further evi

denced in Appendix V, which is a compilation of

scholastic population by counties. It is not a problem

in which the remedy voluntarily adopted in West

Texas or South Texas would be equally applicable

and effective in Northeast Texas. For that reason

no equitable general decree could be formulated

which would be appropriate for every part of the

State of Texas. Specific decrees would have to be

provided for each case, based on the facts and con

ditions then presented to the Court which are shown

to exist in the locality involved in a proper case.

Section 1 of Article VII of the Constitution of

Texas imposes the duty on the Legislature to estab

lish, support and maintain our system of public free

schools.15 This Court announced on May 17, 1954,

that segregation in public education is a denial of the

15 Section 1 of Article VII of the Constitution of Texas

provides: “ A general diffusion of knowledge being essential

to the preservation of the liberties and rights of the people,

it shall be the duty of the Legislature of the State to estab

lish and make suitable provision for the support and main

tenance of an efficient system of public free schools.”

- 2 6 -

equal protection of the laws. Since that time the

Texas Legislature has not met in session, and it is

not known at this time what action the Legislature

will take, if any.

In Minersville School District v. Gobitis, 310 U.S.

586 (1940), this Court stated that it did not want to

become the school board for the entire country. At

page 598 the Court stated:

“ But the courtroom is not the arena for de

bating issues of educational policy. It is not our

province to choose among competing considera

tions in the subtle process of securing effective

loyalty to the traditional ideals of democracy,

while respecting at the same time individual

idiosyncrasies among a people so diversified in

social origins and religious alliances. So to hold

would in effect make us the school board for the

country. That authority has not been given to

this Court, nor should we assume it.” (Emphasis

supplied.)

Keeping the control of public education close to the

local people is perhaps the strongest tradition in

American education. One of the predominant char

acteristics of American education is the variation in

local policies and procedures in terms of unique local

conditions. The Texas Legislature has the right and

duty to maintain public safety and good order. This

Court, in the Gobitis case,16 * 18 supra, recognized its

16 That portion of the Gobitis case dealing with the valid

ity of a statute requiring a compulsory flag salute was over

ruled in Board of Education v. Barnette, 319 U.S 624

(1942).

- 2 7 -

limitations and the authority of the state legisla

tures when it said at page 597:

“ The precise issue, then, for us to decide is

whether the legislatures of the various states

and the authorities in a thousand counties and

school districts of this country are barred from

determining the appropriateness of various

means to evoke that unifying sentiment without

which there can ultimately be no liberties, civil

or religious. To stigmatize legislative judgment

in providing for this universal gesture of re

spect for the symbol of our national life in the

setting of the common school as a lawless inroad

on that freedom of conscience which the Con

stitution protects, would amount to no less than

the pronouncement of pedagogical and psycho

logical dogma in a field where courts possess no

marked and certainly no controlling compe

t e n c e . (Emphasis supplied.)

Other decrees have been held in abeyance until an

appropriate action could be taken by the proper

agency. See Addison v. Holly Hill Co., 322 U.S. 607

(1944), and Railroad Commission of Texas v. Pull

man Company, 312 U.S. 496 (1940).

This Court has the authority to remand these cases

to the courts of first instance, instructing them to

enter decrees implementing the principles enunciated

in the Court’s opinion of May 17, 1954. See Inter- ,

national Salt Company v. United States, 332 U.S.

392 (1947). If this decision stands, then on remand

the courts of first instance would be familiar with

local conditions and could provide a continuing su

pervision over the program of non-discrimination.

— 28—

They could recognize and adjust the equities between

the parties, bringing individual rights into equality

without unduly hindering the public 'school program.

CONCLUSION

Since our position before the Court is that of

amicus curiae only and not that of a party, ordinarily

we would not assume to state specifically the scope

of the decrees to be entered by the Court in these

cases. If the Court attempted to formulate a general

decree applicable to all school districts and States, it

would be prejudging a multitude of cases not before

the Court. However, in entering appropriate decrees

the Court should consider the following suggestions

which are respectfully submitted at the request of

the Court:

(1) In formulating a decree or decrees, the Court

should recognize the long established traditions and

usages which have prevailed in those States main

taining a segregated school system, such as Texas,

under the separate but equal doctrine as predicated

upon the principles announced in Plessy v. Ferguson,

supra. These traditions and usages should not be

suddenly and abruptly destroyed. A period of orderly

transition will insure that a decree will meet with

no more than passive resistance by the public.

(2) In formulating a decree or decrees, this Court

must preserve the democratic and salutary principle

of local self government inherent in our public school

systems. Any decree or decrees entered by the Court

should protect this principle. In this manner the de

crees could appropriately be implemented by the local

■ 2 9 -

school authorities as a legislative and administrative

matter.

(3) The Court, in formulating a decree or de

crees, should preserve the right of free selection and

choice by the patrons of public schools in selecting

the school which will be patronized.

Respectfully submitted,

JOHN BEN SHEPPERD

Attorney General of Texas

BURNELL WALDREP

BILLY E. LEE

J. A. AMIS, JR.

L. P. LOLLAR

J. FRED JONES

JOHN DAVENPORT

JOHN REEVES

WILL DAVIS

Assistants

Amicus Curiae

APPENDICES

TOTAL POPULATION

TOTAL 1950 NON-WHITES

977,458

Source.- Reports o f U .S , Bureau of the Census, 1950

PERCENT OF NON-WHITE POPULATION, 1950

LEGEND

50% and over

Less than 1 %

40% -49%

30% -39%

20% -29%

10% -19%

5% -9 %

1 % -4%

None

1954-55 SCHOLASTIC

(Children between 6-17 inclusive as of September 1, 1954, Residence as of February 1, 1 954)

DALLAM SHERM AN HANSFORD O C H ILT R EE LIPSCO M B

iZ - O O O

. 7 9 ° °

o

h a r t l e y MOORE. HUTCHINSON R O B E R T S

1

HEM PHILL 1

o

° 1 ,6 9 !

o

° ° ° J

\ OLDHAM P O T T E R C A R S O N G R A Y W H EELER 1

i

I O I O 9 1 S O 6 ,

* 4 , o

. .

2 .7 3 . 0 1

1

! D EA F S M IT H R A N D A LL ARM STRONG D O N L E Y jCOLLINGS WORTh!

7 ° o 7 S

' « i

.3 o O . 6 . 4

L 9:2 J

1 1 1 j j

Number of Negro Children

in County and Percent of Negro

Children of all Scholastic

Census Enumerations

Source: Official Scholastic Census Rolls

and Reports for 1954-55 on file in

the Texas Education Agency.

! 6.1 j

■ ■ ... j H

BA 1LEV j LAMB H A LE ! F L O Y D M O T L E Y | C O T T L E 1

60 1 403 4 5"6 1 6 6 6 6 1 3 6 j "

! 2 . 9

L . „

1

! 77

S .7 6 8 4 . 4

!

i " 8 1

j C O C H R A N j! H O CKLEY LU BBO CK C R O S B Y d i c k e n s j K IN G |

| 6 9 j 2 9 1 2001 2 3 6 6 4 i - 2

L r _

5 .0 - 9 . S 4 4 i t e

9 .3 iw iLBARuCR p

X - - \ 3 8 2 j WICHiTA

‘o,-D i 9.9

; VO A K U M | T E R R Y

j ' i 8'

| .. j 2.J-I_ _.l______

L Y N N j 6 A R Z A

I i 4-5“

4 .4 - i J . l

K E M t jSTONE WALL j HASKELL

1 1 61

TMROCHMORrONj YOUNG-

O j 2<-

o 1 .7

1 M ONTAGUE j ' i f I O R A V S O N

I O j C O W L

1 ° ! 'Z p ar_

| W IL L j DCNTON 1 COLLIN

j | 5 - . Y i K > M

I U i 7 .3 I ' I . B

_________ 1-

G A IN E S

4 6

1.6

d a w s o n

2 2 4

T . 7

B O R D E N

o

o

5 C U R R Y

9 S

2.1

I F IS H E R .

i i » 3

1 6 . 0

A n d r e w s M ARTIN HOWARD M ITCHELL j N O L A N

3 0 7 8 - a a r f 9 2 i i~ 7 o

1 .6 6 . 3 4 . 2 0 .9 i 4 . 0

" U hAk ILFORO ! STEPH ENS i « L O PlNTOj

, . — J I 1 KV_

| TARRANT I D A L L A S ,

I i n 9 4 - 3 i KAUFMAN | i f *

WINKLER

♦ 9

2.0

! ECTO R

_ J________________

! M IDLAN D GLASSCOCK s t e r l i n g ] C O K E I R U N N E L S j

| 5 *62 ! 8 9 7 - 2 j o ] 1 0 6 j

! 4 . 2

J________

| 8 . 9 1 .9

- 6 j . ~ i

, . o ;

____ ___.____ ---------------------------------1-------- \ HOOD |

CALLAHAN j EASTLAND | LRATH \ *• I 3 9 7

0 \ »* J « W '. l JO-"

J

CRANE. J UPTOfN

6 6 j 7 4

i 6 ,2 I

_jTOM GREEN L -

IRION

I x X -7------------^COM ANCHE \ - BO SQ U E

B R O W N . o V y \ f 0 3

i • « \ ° / V \

i 2-7 rXCX X~o S; «MtLL6 \ O . X \ <,v-/ o \ S * ? \f ^6o

2 8 .9 /

.e n d e r s o m

1,2.80

Z f 9

' a n o e r ^ n

Z + 7 S 77S

v 3 } r j r e

J 2 .S

T or log i J

T / PANOLA .

( J & 0 9 I

3 6 .7 j

I9 6 0

28.8

SHtLBV

X C u«> \

1 ,7 4 9

31.1

X

j MENARD j

- 12

O \ X \ ' ,X " \ . V " LEON

" > \ ” X ,7 < > \ \ ’ / > 1 5 1 0

, — ̂ *• * * x ♦«

a 3 0 \ . / 8ELL \ a e ' 7

I U -l—-Y v - \

I w lAn o

i ^i •*

\ .

HOUSTON

t w o

/

> ANGELINA

/sA B IN E v

• r i e

9 96

MASON

_4 10

^ L E ’ i

o L — -----------------------------1— l^ O

| G i l l e s p i e j Bl a n c o / t r a v i s

9 8 2

X 7 S 9

/ X j - Z X

HAR«'t>‘

I f 91

22. 9

j E D W A R D S i H E R R i

j • r~S 'Z _

i ^ - 4 ^ v x y (|J# _ oar

B E X A R GUADALUPE » GONZALES f 2 0 6 / 4 . \ *9 ^ 3

^ a » 4 - / LAVACA x

l3 > */ / f 6 l \ ■'" Sv V V

^ . / t r in it y

/ 6 5 - 8 /

.• 3 0 . t / P O L K \ fV l

38 92i^~y^ NTV'/ 11,2 ' 7f>5*. ^ -^ W A L K E R ] V \ 2 f9

H 9 9 \ y t 0«.MEs\ 1865- j 9e7\ '

2J,« /yin ios /C6?V. r1,1 |r».2 i __\ / \ 4-3,0 \ 7-----l o»H ---LT.OO.N

. ^ C b u O l E L O ^ \28. i s j ' C' ’-FCo l V \ 7 0 ,

/ < , I I 9 4 I \ \ 1 ^ . 6 ,/ V U E £ \ \ ; __ \ \ H o o a n G e

/ v 776 - /'---------\ 2 4 .8 \ 15-91 ----' Y l * " 9

\ 2,2.9 i

S __________ i . , /1 . 2 4 7

V W l«>S

V X / , , , 2 * L y y BEND ^

j ( ^ l v ^ t o n ,“t>7* 1 ^

ft,

i s / S j : ;

j \ X 2 J 4 X \ 7 3 6 .7 / FAYETTE \ * “ T h T t / 4 6 . 3 \

h i r 11 v x * 1 A n /| *» / COMAL ^ X 6 8 6 <“<, ‘ ’

* h j -

E/ ! K- 8,4 / ---- ------------ / 5,A „\ A \

2 4 7

APPENDIX II

\ ZAVALLA i " F R iO

i 2 6 1 2 3

i . e

j

i -

. 8

1-----------1 D IM M IT 1 L A S A L l E

13 i o

i i

- 4

o

X A / vr-

■ ATA9COE.A \ / X ( ' * V

I \ ✓ X \ . V / VICTORIA

I 6 6 V * 1 *

| 1 ,2 X 3 , 7 / o o u e d L

I5TZ3

t o , /

/ 7 ‘ 7 4 0 X

rV.Z'.L._^

i_____________I L_ __

2A PATA 1-JlM HOOG i B R O O K S j KENNEDY

9 i - i ? i °

O i <7 j .1 j o

j-------- L.7----j

j " T i i_____ j

° / O J.

f X r WILLALV

" * 8 4 2 1 K ft

'A j CAMERON 5

43 COUNTIES 45 COUNTIES

50 % of Negro Populotion

116,107 Negroes

381,244 Whites

23% of Population, Negro

High Percent: Marion County, 59.5

Low Percent Brazoria County, 10.1

Counties over 50 %

RANDALL

■HARDEMAia—

County over 50%HALE

J L L A Y

{**33 o a v l R fINTfcCiOCj"

c o o j r l

K N O X '

0C1.TA

HUNT

TARRANT

;a<j f m a n .

BORDEN i YAf-« ZANOT

in f, jO w H - jO N .

CALLAHANM ARTIN

X'JjAVARHO

WARD

IR IO N

y$« tN tT V

LAMPASAS.

RODERTSOH;

:l a n o

jAN JACtHtO

ORANGE

m NFT!

. M a t a g o r d a

jMCHUllEN l OAK

D U VAL

KEN NEDY,J iM HOGGZAP ATA

2 5 4 C O U N T I E S

13 % of Population Ages 6-17 inclusive is Negro

230,546 Negroes, 1,556,372 Whites — 1,786,913 Total Population

HANSFORD - OCHILTREE t LIPSCOMB

moore jyuTCHiyse?rj.

^^^4^47QJMegrge«rir^rirzrz

' -i554-,±9 :̂WMtes::-_-_r--rin

W H EELER —- | — --------------

■ Yr “ltu:

~_i~-Z~szs~-̂ zs~^zs~— 40% of Negro Population

.C ap ntigsiTTffi^ ^ 92,969 Negroes

520,920 Whites

TThere are-m a r e Negroes, % - 15% of Population, Negro

T32,539,in HarrS County -̂- - High Percent: Freestone

County, 51.1

Low Percent: Burleson

County, 2.7

88 COUNTIES

90% of Total Negro Population, age 6-17 inclusive

209,076 Negroes

902,173 W hites

19% of Population, age 6-17 is N egro

- |—MftfcL---jemtORCS-^szszzzrzsz^

: BflILEV 1 U H B ____

--------_jJO M --G R E

TV

_ X _ m A so.£L-

--------[ --CUWATRO?-------I TTF-R-n.---- | ____

APPEN DIX II!

DATA

from

OFFICIAL SCHOLASTIC CENSUS REPORTS

for school year 1954-55 on file in the Texas

Education Agency. Enumeration includes chil

dren ages 6-17 inclusive as of September 1,

1954. Residence is as of February 1, 1954.

Possible errors due to duplicate enumera

tions: 4.6% .

- 3 1 -

APPENDIX IV

Educators’ Views on Integration

On July 30, 1954, the Attorney General of Texas

directed a questionnaire to one hundred and fifty-

two Texas school administrative officials. One hun

dred two questionnaires were mailed to white ad

ministrators and fifty questionnaires were mailed to

Negro administrators. Twelve of the questionnaires

were directed to county superintendents, fifty were

directed to school principals and ninety were directed

to district superintendents. Responses were received

in eighty-two instances, eighteen of which were from

Negro educators.

The questionnaire and evaluated responses are:

“ We are in the process of compiling data to deter

mine the feasibility of filing an amicus curiae brief

in the United States Supreme Court relative to the

recent segregation decisions which affects our pub

lic school system. Our school system operates under

legislative authorization, and the Legislature will

not convene in Regular Session until January to con

sider the problem arising by reason of the Supreme

Court decision. Consequently, if any brief is filed, it

should contain a cross-section of the views of educa

tors and the public generally in Texas in an effort to

see what impact the decision has made on our public

school system and customs.

“ By reason of your long familiarity with the field

of education throughout the State we would like to

have an expression of your views on the following

questions:

- 3 2 -

“ 1. In the event of legislative or Supreme Court

direction, what, in your opinion, would be a reason

able minimum period of time for working out an in

tegrated system in your district?”

In evaluating responses, a period of five years was

arbitrarily set as a division. Thirty-six replied that

a period of five years or less would be sufficient.

Forty-two replied that a longer time than five years

was necessary. Nineteen answers volunteered replies

favoring a twelve year plan of integration (begin

ning with the first grade and adding a new grade

each year). Ten of the Negro replies favored a five

year or less program, while five thought a longer

program was necessary. Two Negroes volunteered

that they favored the twelve year plan.

“ 2. Do you consider the local problem more acute

than the problem on a state-wide basis?”

Thirty-nine answered that the local problem was

not more acute, as compared to forty-one replies that

the local problem was more acute. The Negro replies

were eleven affirmative, seven negative.

“ 3. Do you think that the established precedent

of separate schools would seriously handicap the op

eration of integrated schools in your area?”

Sixteen responses did not believe the operation of

integrated schools would be handicapped by the pre

cedent of separate schools, but sixty-four did believe

a handicap would exist. Eleven Negroes replied there

would be no handicap, and seven replied there would

be difficulty with an integrated system.

— 33—

“ 4. (a) In the event of an integrated system,

could all school buildings be utilized ?”

Forty-eight responses believed all present school

buildings could be used in an integrated program.

Thirty-three thought that there would be a loss of

use in an integrated system. Ten Negroes replied

that all buildings could be used and seven thought

that all buildings could not be used in an integrated

system.

“ 4. (b) To what extent are present school build

ings situated so that natural zones could be estab

lished that would continue to serve substantially the

same student body in attendance at the same schools

as under present operations?”

Forty replies stated that natural boundaries sep

arated the two races and the schools for each race.

Thirty-eight responded that no natural boundaries

existed in their locality. Of the Negro educators,

eleven replied that natural boundaries existed, while

five answered that natural boundaries did not exist

in their locality.

“ 4. (c) If any existing buildings would be un

usable in an integrated program, estimate the pres

ent value of such buildings.”

Forty answered that there would be no loss of

buildings in operating an integrated school system.

Thirty-eight answered that there would be some loss

within their district. Of the Negro educators nine re

plied there would be no loss, while six answered that

there would be some loss.

“ 5. How will an integrated public school system

affect the school teachers in your area?”

Fifteen responded that there would be no affect

on school teachers in their districts. Fifty-six an

swers believed the Negro teachers would be adversely

affected by an integrated school program. Some re

plies thought white teachers in their districts would

refuse to teach in an integrated school. The Negro

replies seeing no affect within their districts num

bered seven, while three feared an adverse affect.

“ 6. If the patrons of your district, both negro

and white, were given free choice, what per cent

would send their children to the same school now at

tended?”

Seventy-seven replied that 85% or more would

continue attending the same school if they had free

choice. Of this number fourteen answers were from

Negro administrators. Only three answered that stu

dents in their districts would prefer attending inte

grated schools, and all three replies were by Negro

administrators.

APPENDIX Y

W hites on Negroes on

County

1954-1055

Scholastic

Census

1954-1955

Scholastic

Census

% o f

Negroes

1 . Anderson 4,127 2,473 34.5

2. Andrews 1,885 30 1.6

3. Angelina 6,645 1,398 17.4

4. Aransas 1,154 14 1.2

5. Archer 1,541 0 ___

6. Armstrong 381 0

7. Atascosa 5,266 66 1.2

8. Austin 1,977 789 28.5

9. Bailey 1,994 60 2.9

10. Bandera 725 0 ___

11. Bastrop 2551 1,477 36.7

12. Baylor 1,297 60 4.4

13. Bee 4,831 134 2.7

14. Bell 11,788 1,760 13.0

15. Bexar 109,453 5,997 5.2

16. Blanco 806 22 2.7

17. Borden 176 0 ___

18. Bosque 2,263 103 4.3

19. Bowie 10,895 3,805 25.9

20. Brazoria 13,514 1,523 10.1

21. Brazos 5,437 2,132 28.17

22. Brewster 1,460 9 .6

23. Briscoe 688 64 8.5

24. Brooks 2,336 3 .1

25. Brown 4,994 140 2.7

26. Burleson 1,791 1,063 37.6

27. Burnet 1,794 34 1.9

28. Caldwell 3,743 686 15.5

29. Calhoun 2,933 151 4.9

— 36—

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

30. Callahan

Census

1,690

Census

0

31. Cameron 34,957 117

32. Camp 1,153 822

33. Carson 1,613 0

34. Cass 4,018 2,400

35. Castro 1,458 11

36. Chambers 1,649 447

37. Cherokee 4,905 1,980

38. Childress 1,649 113

39. Clay 1,861 14

40. Cochran 1,503 69

41. Coke 826 0

42. Coleman 2,761 94

43. Collin 7,950 1,062

44. Collingsworth 1,692 172

45. Colorado 2,827 1,134

46. Comal 3,916 83

47. Comanche 2,408 0

48. Concho 940 2

49. Cooke 4,783 186

50. Coryell 3,518 179

51. Cottle 919 36

52. Crane 994 66

53. Crockett 893 12

54. Crosby 2,168 236

55. Culberson 606 0

56. Dallam 1,638 12

57. Dallas 119,280 18,943

58. Dawson 3,695 224

59. Deaf Smith 2,456 7

60. Delta 1,416 219

% o f

Negroes

.3

41.6

37.4

.7

21.3

28.8

6.1

.7

4.4

3.3

11.8

9.2

28.6

2.1

.2

3.7

4.8

3.8

6.2

1.3

9.8

.7

13.7

5.7

.3

13.4

— 37-

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

% ot

Negroes

61. Denton

Census

7,220

Census

567 7.3

62. De Witt 4,901 798 14.0

63. Dickens 1,380 64 4.4

64. Dimmit 3,505 13 .4

65. Donley 1,087 75 6.4

66. Dnval 4,533 0

67. Eastland 4,110 64 1.5

68. Ector 12,923 562 4.2

69. Edwards 541 1 .2

70. Ellis 6,570 2,875 30.4

71. El Paso 45,775 719 1.6

72. Erath 2,927 20 .7

73. Falls 3,191 1,978 38.3

74. Fannin 4,900 708 12.6

75. Fayette 3,492 982 21.9

76. Fisher 1,777 113 6.0

77. Floyd 2,291 166 6.8

78. Foard 742 90 10.8

79. Fort Bend 6,304 1,803 22.2

80. Franklin 783 126 13.9

81. Freestone 1,675 1,749 51.1

82. Frio 2,785 23 .8

83. Gaines 2,796 46 1.6

84. Galveston 21,504 5,036 19.0

85. Garza 1,397 45 3.1

86. Gillespie 2,137 0

87. Glasscock 255 5 1.9

88. Goliad 1,302 151 10.4

89. Gonzales 3,357 960 22.2

90. Gray 5,727 159 2.7

91. Grayson 12,366 1,303 9.5

■38-

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

% ot

Negroes

92. Gregg

Census

10,895

Census

3,739 25.5

83. Grimes 1,911 1,563 45.0

94. Guadalupe 5,228 814 13.5

95. Hale 7,618 456 5.7

96. Hall 1,770 228 11.4

97. Hamilton 1,790 0

98. Hansford 989 0

99. Hardeman 1,769 181 9.3

100. Hardin 4,268 791 15.6

101. Harris 156,638 32,559 17.2

102. Harrison 5,059 6,042 54.4

103. Hartley 233 0

104. Haskell 2,892 161 5.3

105. Hays 4,332 234 5.12

106. Hemphill 803 0

107. Henderson 3,657 1,280 25.9

108. Hidalgo 4,511 84 .2

109. Hill 4,792 1,308 21.4

110. Hockley 5,391 281 5.0

111. Hood 1,054 18 1.2

112. Hopkins 3,595 666 15.6

113. Houston 2,511 2,110 45.7

114. Howard 6,423 285 4.2

115. Hudspeth 868 0 ___

116. Hunt 6,188 1,436 18.8

117. Hutchinson 7,511 116 1.5

118. Irion 355 0

119. Jack 1,534 23 1.5

120. Jackson 3,221 418 11.5

121. Jasper 3,834 1,540 28.7

122. Jeff Davis 415 0

—39

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

% of

Negroes

123. Jefferson

Census

34,353

Census

11,297 24.7

124. Jim Hogg 1,340 0 —

125. Jim Wells 7,757 55 .7

126. Johnson 6,595 397 5.7

127. Jones 4,137 325 7.3

128. Karnes 3,724 143 3.7

129. Kaufman 4,288 2,222 34.1

130. Kendall 1,311 11 .8

131. Kenedy 142 0 —

132. Kent 236 6 2.5

133. Kerr 2,602 104 3.8

134. Kimble 868 0

135. King 169 12 6.6

136. Kinney 471 60 11.3

137. Kleberg 5,443 172 3.1

138. Knox 2,069 157 7.0

139. Lamar 6,644 1,692 20.3

140. Lamb 4,855 403 7.7

141. Lampasas 1,852 30 1 .6

142. La Salle 2,800 0

143. Lavaca 3,484 561 13.9

144. Lee 1,582 776 32.9

145. Leon 1,517 1,310 46.3

146. Liberty 5,368 1,591 22.9

147. Limestone 2,822 1,654 36.9

148. Lipscomb 725 0

149. Liveoak 2,334 4 .8

150. Llano 904 2 .2

151. Loving 20 0

152. Lubbock 22,164 2,001 8.3

153. Lynn 2,240 104 4.4

_ _ 4 0 —

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

% o f

Negroes

154. Madison

Census

978

Census

622 38.9

155. Marion 896 1,314 59.5

156. Martin 1,160 78 6.3

157. Mason 893 10 1.1

158. Matagorda 4,537 1,149 20.2

159. Maverick 3,430 0

160. McCulloch 2,184 84 3.7

161. McLennan 21,888 5,260 19.4

162. McMullen 200 0

163. Medina 4,730 31 .6

164. Menard 685 12 1.7

165. Midland 9,143 897 8.9

166. Milam 4,249 1,199 22.0

167. Mills 1,024 0

168. Mitchell 2,570 192 6.9

169. Montague 3,515 0

170. Montgomery 4,680 1,541 24.8

171. Moore 3,562 0

172. Morris 1,816 1,018 35.9

173. Motley 633 66 9.4

174. Nacogdoches 4,218 3,278 36.0

175. Navarro 6,076 2,475 28.9

176. Newton 1,604 996 38.3

177. Nolan 4,083 170 4.0

178. Nueces 45,914 1,748 3.7

179. Ochiltree 1,114 0

180. Oldham 653 0

181. Orange 10,179 1,209 10.6

182. Palo Pinto 3,694 125 3.3

183. Panola 2,542 1,809 41.6

184. Parker 4,768 89 1.8

— 41—

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

% o f

Negroes

185. Parmer

Census

1,867

Census

27 1.4

186. Peeos 2,699 35 1.3

187. Polk 2,568 1,112 30.2

188. Potter 19,370 1,010 4.9

189. Presidio 1,536 0

190. Rains 729 114 13.5

191. Randall 1,316 0

192. Reagan 780 41 5.0

193. Real 480 0

194. Red River 3,155 1,173 27.1

195. Reeves 3,842 133 3.3

196. Refugio 2,522 275 9.8

197. Roberts 197 0

198. Robertson 2,439 2,141 46.7

199. Rockwall 938 539 36.5

200. Runnels 3,437 106 3.0

201. Rusk 5,439 3,154 36.7

202. Sabine 1,336 518 27.9

203. San Augustine 1,222 844 40.8

204. San Jacinto 666 967 59.2

205. San Patricio 12,143 190 1.5

206. San Saba 1,599 9 .6

207. Schleicher 654 40 5.8

208. Scurry 4,236 93 2.1

209. Shackelford 840 16 1.9

210. Shelby 3,623 1,622 30.9

211. Sherman 574 0 ___

212. Smith 11,385 5,558 32.8

213. Somervell 493 0

214. Starr 5,053 0

215. Stephens 1,646 60 3.5

— 42—

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on

1954-1955

Scholastic

216. Sterling

Census

308

Census

2

217. Stonewall 681 36

218. Sutton 895 15

219. Swisher 2,318 47

220. Tarrant 74,977 8,904

221. Taylor 13,248 594

222. Terrell 656 0

223. Terry 3,122 81

224. Throckmorton 634 0

225. Titus 3,207 733

226. Tom Green 11,538 621

227. Travis 27,111 4,761

228. Trinity 1,524 658

229. Tyler 2,121 705

230. Upshur 2,965 1,533

231. Upton 1,598 74

232. Uvalde 4,307 44

233. Val Verde 4,440 80

234. Van Zandt 4,086 451

235. Victoria 8,502 733

236. Walker 1,786 1,865

237. Waller 1,367 1,178

238. Ward 2,870 39

239. Washington 2,333 1,778

240. Webb 16,089 5

241. Wharton 7,504 2,087

242. Wheeler 2,104 66

243. Wichita 17,203 1,219

244. Wilbarger 3,490 382

245. Willacy 5,490 21

246. Williamson 6,851 1,357

% o f

Negroes

.6

5.0

1.6

2.0

10.6

4.3

2.5

18.6

5.1

14.9

30.1

24.9

34.1

4.4

1.0

1.8

9.9

7.9

51.1

46.29

1.3

45.2

.1

21.8

3.0

6.6

9.9

.4

16.5

•— 43—

County

W hites on

1954-1955

Scholastic

Negroes on