Memo from Chambers to Lee; Correspondence between Chambers and Wilensky

Correspondence

August 5, 1991 - August 14, 1991

4 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Matthews v. Kizer Hardbacks. Memo from Chambers to Lee; Correspondence between Chambers and Wilensky, 1991. 22f088c2-5c40-f011-b4cb-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21a9e85e-54ab-4ac7-af97-92c59f016b63/memo-from-chambers-to-lee-correspondence-between-chambers-and-wilensky. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

A A NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

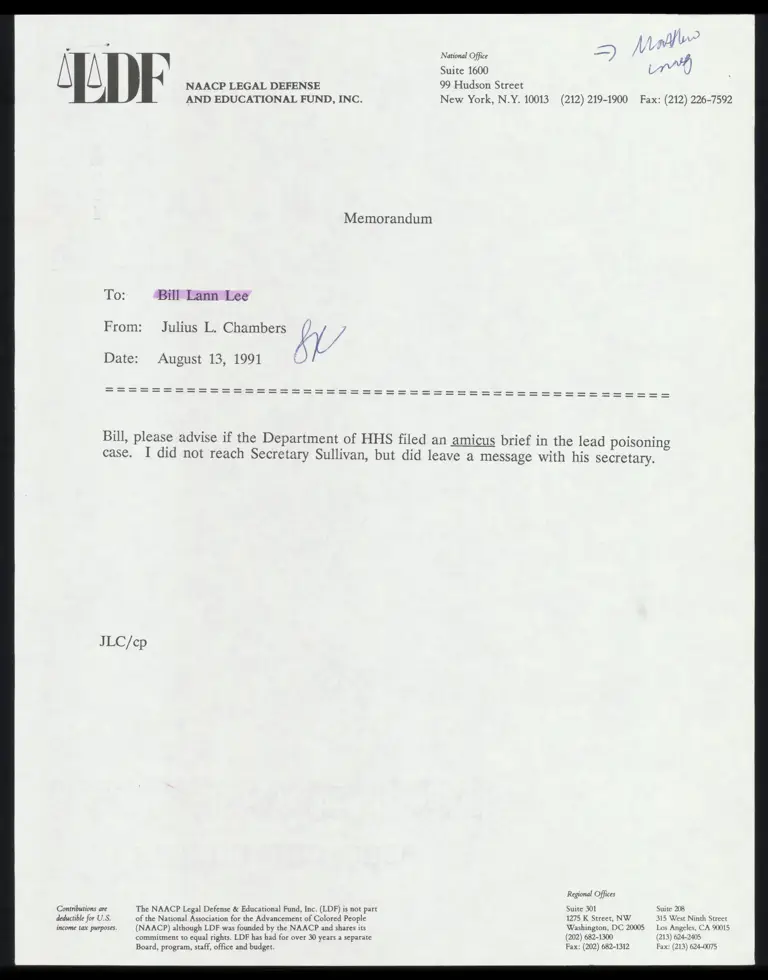

Memorandum

To: Bill Lann Lee

From: Julius L. Chambers H J

Date: August 13, 1991

National Office

Suite 1600

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

——— J

/

I]

pry Viv, iL

ad

/ Y

fyi -

al | v

Ny J

(212) 219-1900 Fax: (212) 226-7592

Bill, please advise if the Department of HHS filed an amicus brief in the lead poisoning

case. I did not reach Secretary Sullivan, but did leave a message with his secretary.

JLC/cp

Contributions are The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part

deductible for U.S. of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

income tax purposes. (NAACP) although LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its

commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 30 years a separate

Board, program, staff, office and budget.

Regional Offices

Suite 301

1275 K Street, NW

Washington, DC 20005

(202) 682-1300

Fax: (202) 682-1312

Suite 208

315 West Ninth Street

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 624-2405

Fax: (213) 624-0075

rpms

aaa

a aan

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

National Office

Suite 1600

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

August 13, 1991

Dr. Gail R. Wilensky

Administrator

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

Health Care Financing Administration

Washington, D.C. 20201

Dear Dr. Wilensky:

(212) 219-1900 Fax: (212) 226-7592

Thank you for your letter of August 5 and for advising that the Department is planning

to file a brief in connection with our California Department of Health Services

proceeding.

JLC/cp

cc: Bill Lann Lee

Contributions are The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part

Sincerely,

pi A

Julius L. Chambers

Pifector-Counsel

Regional Offices

Suite 301 Suite 208

%,

,

EA

of

W

E

L

T

h

¢

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Health Care Finascing Administration

The Administrator

Washington, D.C. 20201

AG 5 199]

Ag »

Julius LeVonne Chambers, Esquire

Director Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, New York 10013

Dear Mr. Chambers:

I am responding to your letter to Secretary Sullivan concerning the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s civil action against the California Department of

Health Services for its alleged failure, under the Medicaid Early and Periodic

Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) program, to administer blood

lead tests to screen for lead poisoning in young children.

I am aware that the Federal court in which your action is pending has

asked this Department to file an amicus curiae brief concerning Federal policy

under the Medicaid EPSDT program. This Department does intend to file

such a brief, subject to Department of Justice approval.

I hope this is responsive to your inquiry and I appreciate your interest in

this subject.

Sincerely,

AOU

Gail R. Wilensky, Ph.

Administrator