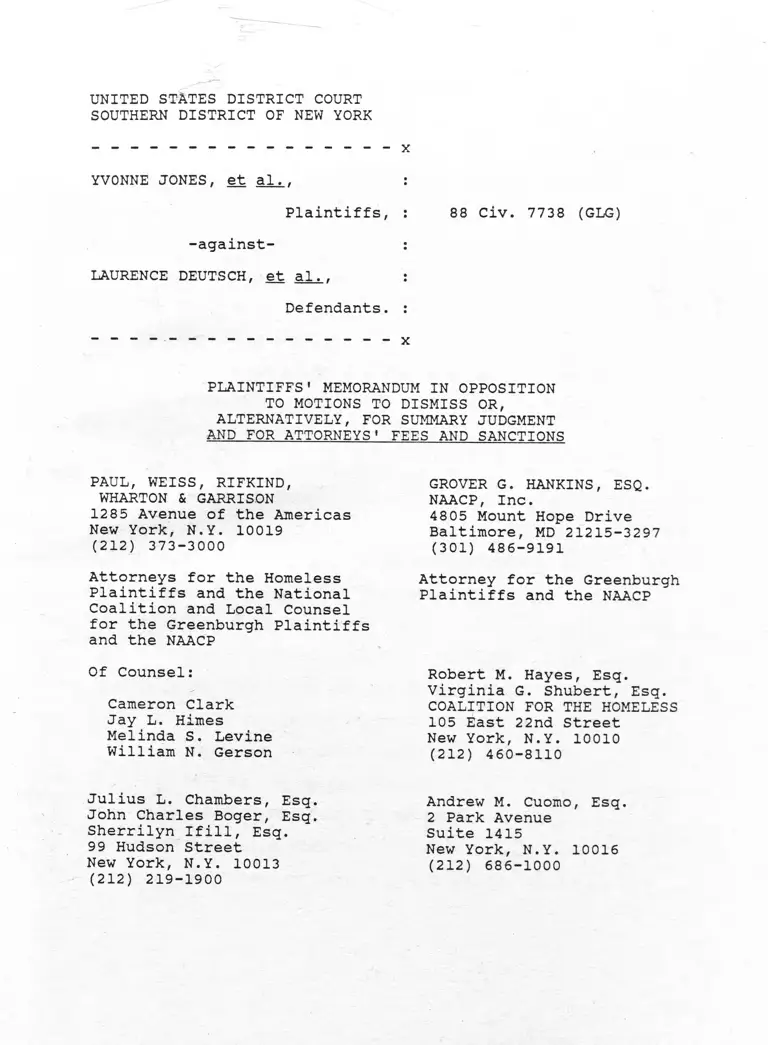

Jones v. Deutsch Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Motions to Dismiss or, Alternatively, for Summary Judgement and for Attorneys' Fees and Sanctions

Public Court Documents

January 26, 1989

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Deutsch Plaintiffs' Memorandum in Opposition to Motions to Dismiss or, Alternatively, for Summary Judgement and for Attorneys' Fees and Sanctions, 1989. 18edd17e-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21b5bf99-4c68-46f6-bd9c-e4c97ac18c9c/jones-v-deutsch-plaintiffs-memorandum-in-opposition-to-motions-to-dismiss-or-alternatively-for-summary-judgement-and-for-attorneys-fees-and-sanctions. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

X

YVONNE JONES, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

-against-

LAURENCE DEUTSCH, et al. ,

Defendants.

x

88 Civ. 7738 (GLG)

PLAINTIFFS' MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION

TO MOTIONS TO DISMISS OR,

ALTERNATIVELY, FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

AND FOR ATTORNEYS' FEES AND SANCTIONS

PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND,

WHARTON & GARRISON

1285 Avenue of the Americas

New York, N.Y. 10019

(212) 373-3000

Attorneys for the Homeless

Plaintiffs and the National

Coalition and Local Counsel

for the Greenburgh Plaintiffs

and the NAACP

Of Counsel:

Cameron Clark

Jay L. Himes

Melinda S. Levine

William N. Gerson

Julius L. Chambers, Esq.

John Charles Boger, Esq.

Sherrilyn Ifill, Esq.

99 Hudson Street

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

GROVER G. HANKINS, ESQ.

NAACP, Inc.

4805 Mount Hope Drive

Baltimore, MD 21215-3297

(301) 485-9191

Attorney for the Greenburgh

Plaintiffs and the NAACP

Robert M. Hayes, Esq.

Virginia G. Shubert, Esq.

COALITION FOR THE HOMELESS

105 East 22nd Street

New York, N.Y. 10010

(212) 460-8110

Andrew M. Cuomo, Esq.

2 Park Avenue

Suite 1415

New York, N.Y. 10016

(212) 686-1000

Table of Contents

Page

Table of Abbreviations.................................. iii

Preliminary Statement .............................. . i

Statement of Facts ...................................... 4

The Parties ........................................ 4

The West HELP Shelter ............................. 6

The Conspiracy Forms .............................. 7

The Proposed Village .............................. 7

Supervisor Veteran's Decision .................... 9

Plaintiffs* Complaint ............................. 11

The Pending Motions ............................... 13

Argument ................................................. 14

I A CLAIM FOR DECLARATORY RELIEF IS STATED.......... 15

II SECESSION IS NOT CONSTITUTIONALLY PROTECTED

UNDER THE FIRST AMENDMENT ........ 17

A. The Secessionist Plan is Actionable.... . 18

B. The Conspiracy Provisions of § 1985(3)

Reach the Moving Defendants' Conduct ....... 21

C. The First Amendment Cases That Defendants

Rely On Are Inapplicable .................... 2 8

III THERE IS A JUSTICIABLE CONTROVERSY ............... 32

IV PLAINTIFFS HAVE STANDING TO SUE .................. 3 7

A. The Threat of Injury Is Sufficient .......... 37

(i)

Page

B. The Greenburgh Plaintiffs ................... 41

C. The Homeless Plaintiffs ..................... 43

D. The Organizational Plaintiffs ......... 45

E. Warth v. Seldin Is Inapplicable ............. 48

V A CLAIM IS PLEADED AGAINST DEFENDANT KAUFMAN ..... 49

Conclusion ............................... ............... 53

(ii)

Table of Abbreviations

Complaint Complaint, filed

November 1, 1988.

Papers in Support of Motions

Def. Mem. Memorandum on Behalf of

Defendants Deutsch, Tone,

Goldrich, and Coalition of

United Peoples, Inc. in Support

of Motion to Dismiss, and for

an Award of Sanctions and

Reasonable Attorney's Fees,

dated December 12, 1988.

Kauf. Mem. Memorandum on Behalf of

Defendant Colin Edwin

Kaufman in Support of

Cross-Motion, Joining in

Motion of Co-defendants to

Dismiss, for Reasonable

Attorneys' Fees and for an

Award or Sanctions and

Additionally Moving for

Summary Judgment, dated

December 19, 1988.

Kauf. Aff. Affidavit of Colin Edwin

Kaufman, sworn to December 19,

1988.

Papers in Opposition to Motions

Dixon Aff. Affidavit of Melvin Dixon,

sworn to January 24, 1989.

Himes Aff. Affidavit of Jay L. Himes,

sworn to January 25, 1989.

Hombs Decl. Declaration of Mary Ellen

Hombs, dated January 25, 1989.

Jones Aff. Affidavit of Yvonne Jones,

sworn to January 24, 1989.

Jordan Decl. Declaration of Anita Jordan

dated January 25, 1989.

Myers Decl. Declaration of Thomas Myers,

dated January 25, 1989.

(iii)

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK

X

YVONNE JONES, et al., :

Plaintiffs, : 88 Civ. 7738 (GLG)

-against- :

LAURENCE DEUTSCH, et al.. :

Defendants. :

x

PLAINTIFFS' MEMORANDUM IN OPPOSITION

TO MOTIONS TO DISMISS OR,

ALTERNATIVELY, FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

AND FOR ATTORNEYS' FEES AND SANCTIONS

Defendants Deutsch, Tone, Goldrich and Coalition of

United Peoples, Inc. ("COUP") have moved to dismiss the

complaint pursuant to Rule 12(b)(6). Defendant Kaufman has

filed a separate cross-motion to dismiss or, alternatively,

for summary judgment under Rule 56. All movants also seek an

award of attorneys' fees and sanctions under Rule 11 and

42 U.S.C. § 1988. Both motions should be denied in all

respects.

Preliminary Statement

This case arises out of a proposal by the County of

Westchester and the Town of Greenburgh to build housing for

homeless families with children. These families are

overwhelmingly members of racial minorities. Community

2

resistance to the proposal includes an effort, led by the

Moving Defendants, to assume control of the development site

by incorporating a new village. As defendant Deutsch — a

leading proponent of the new village — has said: "We'll

secede and take a nice piece of the tax base with us."

Before the secession could proceed, however, state

law required that the Supervisor of the Town of Greenburgh,

defendant Anthony Veteran, consider the matter. After

studying the proposed village map and holding a hearing,

Mr. Veteran concluded:

In the entire 30 years during which I have held elective

office I have never seen such a blatant and calculated

attempt to discriminate. The boundaries repeatedly

deviate from a natural course solely to exclude individual

properties where blacks live.

For this and other reasons, Mr. Veteran rejected the

attempt to secede. The Moving Defendants' co-secessionists

are trying to overturn that decision in an Article 78 pro

ceeding.

This federal action challenges the secessionist

movement directly — as a conspiracy to violate the civil

rights of plaintiffs, community blacks and homeless persons,

and two corresponding organizations, the National Association

for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc./White Plains-

Greenburgh Branch and the National Coalition for the

Homeless.

3

Defendants Deutsch, Tone, Goldrich, Kaufman and

COUP (the "Moving Defendants") seek dismissal. Their primary

argument is that they have an absolute privilege under the

First Amendment to try to form a racially discriminatory

village as a means to scuttle a government effort to extend

equal protection of the laws to the homeless. The Constitution,

however, confers no such privilege.

Secession is action — not speech -- and it is not

protected by the First Amendment. The collective effort to

create a segregated enclave of local government is unlawful,

pure and simple. So too is the collective effort to form a

village for the purpose of blocking a government effort to

discharge constitutional and statutory obligations to the

homeless. This court may grant appropriate relief here —

just as other federal courts have enjoined secessionist plans

in the past, and just as other federal courts have enjoined

voter ballot measures which, if approved, would be

unconstitutional.

The Moving Defendants' other grounds for dismissal

are equally devoid of merit. They contend that there is no

justiciable controversy because the new village is not yet

formed. This argument is wide of the mark: the scheme to

form the village is actionable.

The Moving Defendants further argue that plaintiffs

lack standing to sue. That contention also fails.

4

Plaintiffs are directly affected by the secessionist

movement. They clearly have standing.

Thus, the motions to dismiss or (as to defendant

Kaufman) for summary judgment should be denied. Since the

basic motions fail, the applications for attorneys' fees and

sanctions dissolve.

Statement of Facts

We describe below the parties to this lawsuit and

the background facts from which it arises, as pleaded in the

complaint. Then, we will summarize the civil rights conspiracy

claims alleged, and the motions to dismiss.

The Parties

The 20 plaintiffs consist of homeless persons,

black homeowner/residents of the Town of Greenburgh, the

National Coalition for the Homeless, and the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Inc./White

Plains-Greenburgh Branch (the "National Coalition" and

"NAACP," respectively).

Plaintiffs Jordan, Ramos, T. Myers, L. Myers and

their children (the "Homeless Plaintiffs") are three

Westchester County homeless families — the type of persons

who would be eligible for placement in the housing facilities

that the Moving Defendants are seeking to block. (Complaint

It 5a-c, 14-17.) Plaintiffs Y. Jones, 0. Jones, Bacon,

5

Hodges, Wilson and Dixon (the "Greenburgh Plaintiffs") are

black Greenburgh community homeowners. All the Greenburgh

Plaintiffs reside in the vicinity of, but outside, the

proposed Mayfair Knollwood boundaries, except for Mr. Dixon.

He resides inside the proposed village. (Id. %% 5d-i.)

The National Coalition is a not-for-profit

corporation whose primary purpose is to advocate responsible

solutions to end homelessness. The National Coalition

provides direct assistance to homeless people in the form of

informational services, rent subsidies, food and legal

counsel. (Id. % 5k.)

The NAACP is of course well known. It is a non

profit membership organization that represents the interests

of approximately 500,000 members in 1,800 branches throughout

the country. The NAACP has worked through the courts since

1909 to establish and protect the civil rights of minority

citizens. It sues here through its White Plains/Greenburgh

branch. (Id. f 5j .)

The Moving Defendants are four individuals and a

New York not-for-profit corporation, COUP, formed by

defendant Deutsch and others to stop the homeless housing

development. Defendants Deutsch, Kaufman, Goldrich, and Tone

reside within the boundaries of the proposed village, near

the housing site. (Id̂ . 6, 7.)

6

The sixth defendant is Anthony Veteran, the

Supervisor of the Town of Greenburgh. As will become clear

below, Mr. Veteran is a party for the purposes of declaratory

relief. (Id. 8, 31-38, 60-63.) Plaintiffs do not contend

that he has conspired to violate their civil rights.

The West HELP Shelter

Westchester County is teeming with homeless

families. Many currently are quartered at great public

expense in often squalid motel rooms. Typically, a single

room houses a parent and a number of children. The vast

majority of the County's homeless are members of racial

minorities. fid. 2, 13, 14, 20.)

In January 1988, the Town of Greenburgh proposed to

build housing for 108 homeless families with children on land

within the Town owned by Westchester County. The proposed

developer is West H.E.L.P., Inc. ("West HELP"), a not-for-

profit corporation that constructs housing for the homeless.

The intent of the West HELP development is to provide safe,

convenient and humane emergency (or "transitional") shelter

for homeless families with children. It is part of a joint

County/West HELP proposal to establish a number of such

facilities. (Ids. fl 15-17.)

7

The Conspiracy Forms

Announcement of the West HELP shelter in late 1987

galvanized neighborhood resistance. In February 1988,

defendant Deutsch and others formed COUP, whose purpose is to

stop the project. Around the same time, Deutsch publicly

announced that he and other Town residents intended to

accomplish that objective by incorporating a new village —

later named "Mayfair Knollwood" — pursuant to the New York

Village Law. fid, ff 21-22.)

Deutsch and his co-conspirators propose to use the

new governmental unit of Mayfair Knollwood to block the West

HELP development. As Deutsch has said:

We'll go ahead with secession and take a nice piece of

taxable property with us.

The "secession" plan is racially motivated. Deutsch stated

in opposing the West HELP development:

You're taking a piece of a ghetto and dumping it

somewhere else to get another ghetto started.

(IcL. 1 23.)

Thereafter, the Moving Defendants prepared and

circulated a petition to incorporate Mayfair Knollwood.

(ld,_ 24-25.) The secessionist scheme was underway.

The Proposed Village

The map of Mayfair Knollwood is ugly indeed. The

boundary of the proposed village is irregular and

8

ungeometric; it has more than 30 sides. The proposed village

would exclude all the black and multi-racial housing sur

rounding it. The tortured shape of the village can be

explained only by the purpose of its creators — to exclude

racial minorities. fid. ̂ 26 and Ex. 1.)

Within the proposed village is the West HELP

development site — so that the newly formed government will

be able to seize control and try to halt construction. The

proposed village also includes a disproportionate amount of

the Town's tax base and recreational facilities. Moreover,

the boundary extends outward to include all the undeveloped

land that borders the excluded surrounding minority

neighborhoods — thus assuring the power to create a buffer

zone against possible encroachment from excluded communities

through control of land use. fid. 27-28.)

In September 1988, after hundreds of residents had

signed the incorporation petition, the secessionists pre

sented it to Supervisor Veteran. Under State law, Mr. Veteran

then had the responsibility of calling a hearing, receiving

objections and rendering a decision on whether the incorpora

tion procedure could move ahead. A favorable decision would

clear the way for a vote by the Mayfair Knollwood residents

on whether to secede. fid, 30-32; N.Y. Village L. § 2-212

(McKinney 1973).) Because of the proposed village's compo

sition — resulting, of course, from its gerrymandered

9

borders — the outcome of such a vote was a foregone

conclusion. Thus, defendant Deutsch triumphantly announced:

The incorporation is a fact. . . . The town may delay

us, but it won't stop us. There is nothing that the

town or county could do which could divert us from the

incorporation. (Complaint f 30.)

. . 1/Supervisor Veteran's Decision-7

Town Supervisor Veteran held the required hearing.

On December 6, 1988, he filed his decision rejecting the

incorporation petition on several grounds. (Himes Aff.,

Ex. A.) One ground was race discrimination. Mr. Veteran

found that the Mayfair Knollwood boundaries "were

gerrymandered in a manner to exclude black persons from the

proposed village." (Id. at 2.) We repeat Mr. Veteran's

dramatic words:

In the entire 30 years during which I have held elective

office I have never seen such a blatant and calculated

attempt to discriminate. The boundaries repeatedly

deviate from a natural course solely to exclude

individual properties where blacks live. Within the

boundaries of the proposed village there is not a single

unit of multi-family housing, housing which historically

has been more accessible to minority groups because of

its lower cost. (Id. at 2-3.)

1/ The Veteran decision post-dates the filing of

plaintiffs' complaint. The Moving Defendants have

submitted it on this motion, however, and plaintiffs are

cross-moving for leave to file an amended and

supplemental complaint containing updating allegations

concerning the decision.

10

Recognizing that "[t]he procedures for the

formation of a new village cannot be used to accomplish an

unlawful end," Mr. Veteran concluded that his obligation was

"to defend the constitution and to reject the

petition. . . . " fid, at 4.)

Mr. Veteran also rejected the petition because "the

new village was proposed for the sole purpose of preventing

the construction of transitional housing for homeless

families near the neighborhood of Mayfair Knollwood." fId.)

Again, Mr. Veteran concluded that his duty to defend the

constitution dictated that he reject the petition because

"its purpose is to deny homeless persons needed services, to

exclude homeless persons, and to racially discriminate

2 /against homeless persons who are predominantly black."~y

fid, at 7.)

The Moving Defendants' co-secessionists filed suit

in state court in December 1988 in an effort to overturn the

Veteran decision. (Himes Aff., Ex. B.) Town Supervisor

Veteran, joined by plaintiffs here and others, removed the

V Mr. Veteran found also that the petition breached the

Village Law in several respects and rejected it on those

grounds as well.

11

suit to this Court, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§ 1441(b) and

1443 (2) .

Plaintiffs* Complaint

Plaintiffs filed their complaint on November 1,

1988. Four counts are alleged. Three are grounded in

42 U.S.C. § 1985 (1982), the civil rights conspiracy statute.

The fourth count seeks a declaratory judgment.

The three conspiracy counts are based on the

following statutes, which establish the substantive rights

that the Moving Defendants conspired to abridge:

Count I:__Voting Rights Conspiracy: Both federal

and state law prohibit denying or abridging the right to vote

on account of race. U.S. Const, amend. XV? N.Y. Const,

art. I, §§ l and 11; 42 U.S.C. § 1973 (1982); N.Y. Civil

Rights L. §§ 40-c(l) & (2) (McKinney Supp. 1988).

Count II: Housing Rights Conspiracy; Both federal

and state law prohibit discrimination in housing on account

of race. U.S. Const, amend. XIV; N.Y. Const, art. I, § n

and art. XVII, § 1; 42 U.S.C. §3604 (1982)? N.Y. Civil Rights

L. § 40-c(1) & (2) and N.Y. Exec. L. § 291(2) (McKinney

1982) .

Count III: Shelter Rights Conspiracy: Both

federal and state law guarantee safe and lawful emergency

shelter. U.S. Const, amend. XIV; N.Y. Const, art. I, § 11

12

and art. XVII, § 1; 42 U.S.C.A. §§ 601 and 602 (West 1983 &

Supp. 1988)

As to each of these three counts, plaintiffs allege

that the Moving Defendants' conduct constitutes a conspiracy

in violation of both the "deprivation" and the "preventing or

hindering" provisions of 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3). In pertinent

part, § 1985(3) provides that:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory

conspire . . . for the purpose of depriving, either

directly or indirectly, any person or class of persons

of the equal protection of the laws, or of equal

privileges and immunities under the laws; or for the

purpose of preventing or hindering the constituted

authorities of any state or territory from giving or

securing to all persons within such State or Territory

the equal protection of the laws . . ., in any case or

conspiracy set forth in this section, if one or more

persons engaged therein do, or cause to be done, any act

in furtherance of such conspiracy, whereby another is

injured in his person or property, or deprived of having

and exercising any right or privilege of a citizen of

the United States, the party so injured or deprived may

have an action for the recovery of damages . . . .

Briefly, the Moving Defendants' acts give rise to a

claim because: (1) they deny plaintiffs the enjoyment of the

rights set forth, a violation of the "deprivation" clause;

and (2) they impede the County and Town's efforts to

discharge their corresponding obligations to plaintiffs, a

1/ The complaint inadvertently refers to 42 U.S.C. §§ 301

et sea. That reference is incorrect. It is corrected

in the proposed amended and supplemental complaint.

13

violation of the "preventing or hindering" clause. (Com

plaint <ff 51-53.)

The class-based focus required for a § 1985(3)

claim is present in two respects. First, the voting rights

branch of the conspiracy impairs the rights of the Greenburgh

Plaintiffs, black community residents. Second, the housing

and shelter rights branches of the conspiracy impair the

rights of the Homeless Plaintiffs, two of whom are black and

thus typical of the County's homeless population, which

consists overwhelmingly of racial minorities. (Id. f 20.)

On each of the conspiracy counts, plaintiffs seek

judgment enjoining the conspiracy, and awarding damages,

attorneys' fees and costs. (Id. pp. 22-23.)

Count IV pleads a claim for declaratory relief.

Plaintiffs seek a determination that, in discharge of his

oath of office, defendant Veteran had the right and

obligation to reject the Mayfair Knollwood petition. (Id.

H 31-38, 61-63.)

The Pending Motions

Defendants Deutsch, Tone, Goldrich and COUP served

a motion to dismiss in mid-December 1988. Defendant Kaufman

joined the motion and also moved for summary judgment, based

on a letter that he wrote to a local legislator in January

1988. (Kaufman Aff., Ex. A.)

14

The Moving Defendants do not argue that the

complaint fails to plead the necessary elements of a

§ 1985(3) claim. Instead, they assert that the statute

should not be applied to their conduct because, they say, the

First Amendment offers absolute immunity. They also claim

that there is no case or controversy and that plaintiffs lack

standing to sue. Defendant Kaufman adds an argument that his

participation in the conspiracy has not been shown.

Finally, the Moving Defendants have thrown in a

motion for attorneys' fees and Rule 11 sanctions — an

increasingly common ancillary application whenever a motion

to dismiss is made.

Argument

There is no basis for granting dismissal because

claims are pleaded against all the Moving Defendants. We

show first that a claim for declaratory relief is stated.

Then, we address the § 1985(3) conspiracy claims. We will

demonstrate that there is no merit to the Moving Defendants'

First Amendment, justiciability and standing arguments.

Last, we address the separate argument by defendant Kaufman;

as will be seen, his participation in the conspiracy is

adequately alleged and issues of fact preclude summary

judgment.

15

A CLAIM FOR DECLARATORY

RELIEF IS STATED

The Moving Defendants apparently think that they

can wish away the declaratory claim in the complaint by

ignoring it in their moving papers. The claim will not go

away; the Moving Defendants' invocation of the Village Law to

form a segregated government unit and, now, Town Supervisor

Veteran's decision rejecting their action raise an actual

controversy suitable for resolution by declaratory judgment.

Plaintiffs seek a determination that Supervisor

Veteran had the right and obligation to consider the

constitutional and statutory issues presented by the proposal

to incorporate Mayfair Knollwood. By virtue of his oath of

office to support and defend the federal and state

constitutions, Mr. Veteran was precluded from rendering a

favorable decision when presented with an unlawful

incorporation petition. Thus, plaintiffs maintain, he acted

properly in rejecting the petition. Supervisor Veteran

obeyed the law. Cf. Brewer v. Hoxie School District No. 46,

238 F .2d 91 (8th Cir. 1956) (school district and its

officials had duty to insure desegregation in the face of

community opposition); Matter of Fossella v. Dinkins,

66 N .Y .2d 162, 485 N.E.2d 1017, 495 N.Y.S.2d 352 (1985)

(ballot measure removed because it violated state law).

I

16

The Moving Defendants take a different view. They

insist that the literal language of § 2-206 of the New York

Village Law constrained Mr. Veteran. That law does not, in

its express terms, identify constitutional and statutory

prohibitions and obligations as grounds for rejecting an

incorporation petition. See N.Y. Village L. §§ 2-206 and

2-208 (McKinney 1973 & Supp. 1988). In consequence, on the

Moving Defendants' theory, Mr. Veteran was obligated to blind

himself to the unlawful petition submitted to him. By fail

ing to do so — by acting in accordance with his oath of

office — Mr. Veteran, so the argument goes, acted improp

erly. (Complaint % 36; Himes Aff., Ex. B 44-46, 52-54.)

This is a classic declaratory judgment situation.

The issue presented is what the law permitted or required

Supervisor Veteran to do. The case easily satisfies the

standards for a declaratory judgment claim that the Supreme

Court established long ago;

The controversy must be definite and concrete, touching

the legal relations of parties having adverse legal

interests . . . . It must be a real and substantial

controversy admitting of specific relief through a

decree of conclusive character, as distinguished from an

opinion advising what the law would be on a hypothetical

state of facts . . . . [A] negations that irreparable

injury is threatened are not required. Aetna Life Ins.

Co. v. Haworth. 300 U.S. 227, 240-41 (1937) (citations

omitted).

The controversy at bar is "definite and concrete,"

"real and substantial." Plaintiffs seek a determination of

17

Mr. Veteran's right and obligation to reject the petition

that defendant Deutsch and others presented to him in

September 1988. Whether Mr. Veteran acted properly raises no

First Amendment issue, and no question of justiciability or

standing.

The Mayfair Knollwood proponents' own Article 78

proceeding to upset Mr. Veteran's decision demonstrates that

a claim is pleaded here. In that case, the secessionists

seek to disable Mr. Veteran from taking constitutional (or

statutory) constraints into account. (See Himes Aff., Ex. B,

!1 44-46, 52-54.)

The claim in the Article 78 proceeding and the one

here are two sides of the same coin. Thus, the Moving Defen

dants hardly can be heard to argue that plaintiffs have

failed to state a claim for declaratory relief.-^

II

SECESSION IS NOT CONSTITUTIONALLY PROTECTED

_____ UNDER THE FIRST AMENDMENT______________

The Moving Defendants argue that their conduct is

absolutely privileged under the First Amendment. (Def.

1/ The declaratory judgment claim has an independent

federal question jurisdictional basis under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1331 because Article VI, els. 2 and 3 of the United

States Constitution obligate Supervisor Veteran to

support and defend the constitution. (See Complaint

IH 3, 62-63.)

18

Mem. 6-8.) This argument ignores that the Moving Defendants

are not charged with mere advocacy of a position or the

public expression of views on an issue of community importance

By joining together and taking action in pursuit of a seces

sionist plan to create a new village with racially discrimi

natory boundaries as a means to block government assistance

to the homeless, the Moving Defendants have gone beyond

advocacy and expression. Their conduct gives rise to a claim

under the civil rights conspiracy statute, 42 U.S.C. § 1985(3)

We will show first that the secessionist plan is

actionable and that § 1985(3) affords a remedy. After that,

we shall discuss the authorities that the Moving Defendants

rely on, none of which sustains a First Amendment privilege

here.

A. The Secessionist Plan is Actionable

This is not the first time that community residents

have tried to secede in response to local government efforts

to extend the equal protection of the laws to disadvantaged

classes. There were similar attempts in response to school

desegregation — and the courts repeatedly stopped them.

Burleson v. County Board of Election Commissioners

of Jefferson County. 308 F. Supp. 352 (E.D. Ark. 1970), aff 'd

per curiam. 432 F.2d 1356 (8th Cir. 1970), is illustrative.

There, a school district was under a desegregation order.

Residents in a particular geographic area circulated a

19

petition to withdraw from the district under the procedures

authorized by state law. The district court held that the

withdrawal "will frustrate the Court's decrees and will

impede the District in carrying out its [desegregation]

obligations." 308 F. Supp. at 357. Thus, the court

concluded:

[T]he proposed secession cannot be permitted and will be enjoined. 308 F. Supp. at 358.

The Eighth Circuit affirmed.

The Fifth Circuit stopped a similar secession in

v - Macon County Board of Education. 448 F.2d 746 (5th

Cir. 1971). The Supreme Court eventually confirmed that

secession to avoid desegregation would not be tolerated.

Height v. Council of the City of Emporia. 407 U.S. 451

(1972) ; Cotton v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education. 407

U.S. 484 (1972).

The facts here are analogous. The County and the

Town have determined that the West HELP shelter is needed to

extend the equal protection of the laws to homeless families

with children — just as the courts and the Justice

Department determined that school desegregation plans were

needed to extend equal protection to black school children.

As detailed in the complaint, the Homeless Plaintiffs have

protections under federal and state laws, and the West HELP

shelter is the County and Town's chosen means to extend those

20

protections to the homeless under these provisions.

(Complaint m 15-17, 39-50.) The Moving Defendants may no

more secede in response to that decision than could community

residents try to carve out new school districts to avoid

desegregation.

The secessionist proposal to create Mayfair

Knollwood is actionable for a second reason: the Moving

Defendants have used race to gerrymander the proposed village

boundaries, thus violating the Gomillion principle.

In Gomillion v. Liahtfoot. 364 U.S. 339 (1960), the

City of Tuskegee reshaped its borders from a square to a

28-sided figure (roughly comparable to the more than 30-sided

Mayfair Knollwood border). The effect was to form a

virtually all white enclave, leaving the former city's blacks

on the outside looking in. Because the boundary change

deprived blacks of their pre-existing right to vote on city

affairs, the Supreme Court held that there was a Fifteenth

Amendment violation.

The Gomillion Court emphasized that "[a]cts

generally lawful may be unlawful when done to accomplish an

unlawful end . . . ." Id. at 347, quoting Western Union

Telegraph Co. v. Foster. 247 U.S. 105, 114 (1918). Thus, the

case confirms that neutral mechanisms of state law may not be

used to form a segregated local government enclave. As

alleged in the complaint here, however, the Moving Defendants

seek to do just that. The Mayfair Rnollwood proposal

excludes blacks from the proposed village. (Complaint

11 26-28.)

These allegations must be deemed true for purposes

of this motion. Indeed, the Moving Defendants do not even

try to deny them. Moreover, Mr. Veteran reached the same

conclusion — that the boundaries were unlawfully

gerrymandered. (Himes Aff., Ex. A.)

In summary, these authorities demonstrate that the

Moving Defendants' secessionist plan is actionable.

B. The Conspiracy Provisions of § 1985(3)

Reach the Moving Defendants' Conduct

This case differs from Gomillion and the earlier

secession cases in only one respect. Here, Town Supervisor

Veteran stood his constitutional ground. Instead of joining

the secession, or simply submitting the Mayfair Knollwood

proposal to a vote by the proposed village residents,

Mr. Veteran discharged his constitutional duty and rejected

the incorporation petition. In such circumstances, it is

questionable whether a private right of action to challenge

the secessionist scheme exists under either the Fourteenth or

Fifteenth Amendments, or 42 U.S.C. § 1983. All these

provisions require state action. However, the civil rights

conspiracy statute — 42 U.S.C. § 1985 — fills the gap

because no state action is required to plead claims for

22

relief. See. e.g. , Griffin v. Breckenridqe, 403 U.S. 88

(1971); Weise v. Syracuse University, 522 F.2d 397, 408

(2d Cir. 1975); Action v. Gannon. 450 F.2d 1227 (8th Cir.

1971) (en banc); Perry v. Manocherian, 675 F. Supp 1417, 1428

(S.D.N.Y. 1987).

The Moving Defendants do not contend that there has

been a failure to plead the elements of a § 1985(3) claim;

nor could they. That question was decided against them in

People of the State of New York v. 11 Cornwell Co.. 508

F. Supp. 273 (E.D.N.Y. 1981), aff'd. 695 F.2d 34 (2d Cir.

1982), modified. 718 F.2d 22 (2d Cir. 1983) (en banc).

In 11 Cornwell, the State sought to purchase

property for use as a facility for the mentally retarded.

Neighborhood residents banded together and bought the

property to prevent the State from doing so. The State filed

a § 1985(3) action, claiming both "deprivation" and

"preventing or hindering" violations.

Defendants moved to dismiss for failure to state a

claim. The district court denied the motion. The court held

that the complaint adequately alleged a duty on the part of

the State to secure housing, as an alternative to

institutionalization, for the mentally retarded.

508 F. Supp. at 276. The court noted that the crux of the

complaint was the allegation of "a conspiracy to prevent [the

state agency] from purchasing the property at 11 Cornwell

23

Street for the purpose of keeping an 'undesirable' class of

persons from living there." Id. The court concluded that

plaintiffs had stated a claim:

If defendants have prevented or hindered the state from

buying the home for the reasons alleged by plaintiff,

they have therefore violated § 1985(3) and plaintiff is

entitled to relief appropriate to the circumstances,

including compensatory and punitive damages, for the

harm suffered. Id.

The case came before the Second Circuit after a

trial in which the district court entered judgment for

plaintiffs on the basis of a state law claim. The court of

appeals, however, passed on the substantiality of the federal

§ 1985(3) claim (thereby establishing jurisdiction to

adjudicate the state claim). The court had no difficulty

upholding the trial court's decision:

[B]oth the nature of 11 Cornwell's conduct and the class

basis of the discrimination complained of are sufficient

to make out a colorable claim that 11 Cornwell prevented

or hindered the State from providing the mentally

retarded with 'equal protection of the laws' within the

meaning of Section 1985(3). 695 F.2d at 43.—'

The complaint here is analogous to the one

sustained in 11 Cornwell. That case arose from a government

effort to discharge a duty to furnish housing to the mentally

retarded; this case arises from a comparable government duty

5/ Neither the district court nor the Second Circuit

reached the question whether a § 1985(3) "deprivation"

claim was stated.

24

to the homeless, owed under both federal and state law, to

provide housing and shelter on a non-discriminatory basis.

(Complaint ff 38-48.) In 11 Cornwell, in an effort to keep

out an "undesirable class," defendants implemented a scheme

to buy the property intended for the mentally retarded.

Here, the Moving Defendants are more ambitious: they schemed

to form a secessionist government in order to secure legal

control over the development site. (Complaint 21-23.)

The salient point is the same in both cases: defendants

conspired to prevent or hinder state authorities from

discharging their legal obligations. (Id. 21-30.) See

11 Cornwell, supra. 695 F.2d at 39 ("The analogy to racial

discrimination is close indeed").

As in 11 Cornwell, the Moving Defendants' conduct

is actionable. The Homeless Plaintiffs, members of the

intended group of beneficiaries of the government effort to

extend shelter, and the National Coalition, may sue to remove

the obstacle put up to prevent or hinder the West HELP

development. They also may sue because the Moving

Defendants' conspiracy includes the purpose of depriving them

of the equal protection of the laws. Compare Brewer v. Hoxie

School District No. 46. 238 F.2d 91 (8th Cir. 1956) (school

25

officials could bring § 1985(3) claim against persons who

impeded desegregation effort)

Moreover, here, there is not only a claim of

conspiracy directed at the housing/shelter rights of homeless

persons, but also additional § 1985(3) conspiracy claims.

Mayfair Knollwood, if incorporated, would transform

the racially integrated community of the Town of Greenburgh

into a Town and a Village, the latter a white enclave. Town

blacks outside Mayfair Knollwood would be deprived of their

right to vote on matters affecting the Mayfair Knollwood

6/ The Moving Defendants make an inelegant attempt to argue

that § 1985(3) does not apply because their

discriminatory conduct is based on the economic status

of the homeless. (Def. Mem. 15-16.) See United

Brotherhood of Carpenters & Joiners v. Scott, 463

U.S. 825 (1983) (declining to apply § 1985 to a labor

dispute). This argument misses the point. The homeless

are both poor and predominantly racial minority members.

So long as the discrimination alleged has a racial

animus, it is of no consequence that discrimination on

other grounds may also play a role. Cf■ Quinones v.

Szorc. 771 F.2d 289 (7th Cir. 1985) (conspiracy directed

to race and political association was actionable under

§ 1985). Moreover, irrespective of race, a sufficient

class-based animus is pleaded because, as alleged

(Complaint 23, 26-28), both the federal and state

governments recognize that needy persons, such as the

Homeless Plaintiffs, "require and warrant special

federal assistance in protecting their civil rights."

DeSantis v. Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co., 608 F.2d

327, 333 (9th Cir. 1979), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 967

(1981). See also Tvus v. Ohio Dept, of Youth Services,

606 F. Supp. 239, 246 (S.D. Ohio 1985) (§ 1985(3) should

be construed to reach "a wide variety of non-racial

classes").

26

area, as to which they currently do vote. The few blacks

within Mayfair Knollwood, by contrast, would see their votes

diluted.

By collectively seeking to achieve these results,

the Moving Defendants have conspired to deprive the

Greenburgh Plaintiffs of their voting rights. Gomillion.

supra, 364 U.S. 339. See also Means v. Wilson, 522 F.2d 833,

839 (8th cir. 1975) cert, denied. 424 U.S. 958 (1976)

(§ 1985(3) protects the right to vote in tribal election

against private conspiracy). They also have conspired to

prevent or hinder the Town from giving full and undiluted

voting rights to all residents within its current boundaries,

regardless of race.-^

In addition, both federal and state law prohibit

government officials from denying housing on account of race.

See, ê jĝ , 42 U.S.C. § 3604 (1982); N.Y. Exec. L. § 291(2)

(McKinney 1982). Government use of zoning (or other

regulatory) power to promote racial discrimination in housing

therefore is unlawful.

U Aspects of the voting rights and other claims alleged in

the complaint require development of a full factual

record through discovery and trial. At this stage, the

only issue is the sufficiency of the complaint's

allegations as a matter of law.

27

United States v. City of Black Jack, 508 F.2d 1179

(8th Cir. 1974) , cert, denied, 422 U.S. 1042 (1975),

presented a situation strikingly akin to the one at bar.

Community residents formed a new — nearly all-white ■— city

in response to a St. Louis housing plan for low-to-moderate

income families. After formation, the city passed an

ordinance prohibiting new multi-family dwellings. Finding

that the effect of the ordinance was to segregate low-income

blacks from a white area, the court struck down the

ordinance. Id. at 1184. See also Huntington Branch. NAACP

v. Town of Huntington. 844 F.2d 926 (2d Cir.) (town violated

federal law by refusing to rezone to permit construction of

multi-family units outside of specified areas), aff'd. ___

U.S. ___, 109 S. Ct. 276 (1988).

Use of zoning power to discriminate is unlawful.

An agreement so to use that power is a conspiracy to do an

unlawful act, and hence actionable as a § 1985(3) violation.

The complaint alleges that it is part of the Moving

Defendants' purpose to use Mayfair Knollwood's zoning power

to block the West HELP shelter, most of whose intended

beneficiaries are racial minority members, such as two of the

Homeless Plaintiffs. (Complaint 1, 23.) Thus,

28

plaintiffs' complaint states the elements of this claim as

well . ̂

C. The First Amendment Cases That Defendants

Relv On Are Inapplicable________________ _

The Moving Defendants seek to dress up their

secessionist plan in First Amendment trappings, but the suit

will not fit. There is no First Amendment privilege here.

No one has sued the Moving Defendants for

expressing opposition to the West HELP development. They are

free to try to persuade the County and the Town that the

proposal should be rejected for whatever reasons. Forming a

secessionist government, propped up by racially gerrymandered

borders, however, is not a constitutionally protected means

of expressing opposition. Forming a government is action.

8/ The Moving Defendants argue that, in prior state court

litigation, West HELP development proponents claimed

(and the state court agreed) that Mayfair Knollwood

could not, as a matter of law, so use the zoning power.

(Def. Mem. 3; Himes Aff., Ex. C.) DefendantsJ argument

is a strawman. In this action, what matters is the

Moving Defendants' purpose — because that is a central

element of the conspiracy. As alleged (Complaint f 1),

the Moving Defendants have announced their intention to

try to abuse the zoning power. That the law would deny

them a right to do so — were the matter eventually

litigated — is immaterial. Section 1985(3) reaches

their agreement to do the unlawful act, thereby

preventing them from doing it.

29

The mere fact that New York law calls the piece of

paper that initiates the effort to create the new government

a "petition" does not mean that preparing, signing, or cir

culating the document is "petitioning" in the constitutional

sense. See Village Law § 2-202 (McKinney 1973 & Supp. 1988).

The citizens in Burleson, supra. 308 F. Supp. 353, also

signed petitions in order to secede from their school

district. The court did not pause to enjoin the secession.

Accord, Aytch v. Mitchell. 320 F. Supp. 1372, 1375 (E.D. Ark.

1971) (petitions circulated; injunction issued).

Indeed, voting is core First Amendment activity.

Yet, as discussed below, in various contexts, the courts have

issued injunctive relief against ballot measures. (See

pp. 32-35, infra.) These decisions demonstrate that the

First Amendment's protection for speech and petitioning does

not extend to submission to the electorate of proposals

which, if approved, would be unlawful. As the Supreme Court

has held, "the voters may no more violate the Constitution by

enacting a ballot measure than a legislative body may do so

by enacting legislation." Citizens Against Rent Control/Coa-

lition for Fair Housing v. City of Berkeley. 454 U.S. 290,

295 (1981).

Not surprisingly then, the authorities cited by the

Moving Defendants do not support First Amendment immunity.

They rely heavily on Weiss v. Willow Tree Civic Ass'n. 467

30

F. Supp. 803 (S.D.N.Y. 1979). (Def. Mem. 7-8.) In Weiss,

however, the defendants did not go beyond advocacy; they did

not try to form an unlawful, secessionist, government.

There, plaintiffs, a congregation of Jews, sought

to establish a housing development in Ramapo. The

development required local board approval. Defendants

opposed plaintiffs' application to the board, resulting in

eventual abandonment of the development. Plaintiffs filed a

civil rights conspiracy action.

Judge Weinfeld granted defendants' motion to

dismiss. Relying on the First Amendment as an alternative

basis for dismissal of the § 1985(3) claim, the court

explained that the complaint:

[R]eveals, at most, a concerted effort by defendants to

speak out against the proposed B.Y.S. development and to

utilize various legal channels to oppose the application

for a permit. . . . Whatever its subjective impact on

the officials of the Town, such action was nothing more

than peaceable assembly petitioning municipal

authorities for redress of grievances and is thereby

entitled to First Amendment protection. Id. at 816, 817

(footnote omitted; emphasis added).

This case is not Weiss. The Weiss defendants urged

the existing government to act or refrain from acting. That

is the essence of petitioning in the constitutional sense.

Here, on the other hand, the Moving Defendants are being sued

for conspiring to secede. As we have seen, that conduct is

not protected activity. Cf. 11 Cornwall, supra, 695 F.2d

31

at 42. ("11 Cornwell's actions do not implicate any First

, , , , 9 /Amendment interests at stake," citing Weiss.)—■'

The other cases relied on by the Moving Defendants

come no closer to establishing a First Amendment privilege

for the secessionist scheme to form an illegal government

that is alleged here. (Def. Mem. 6-8.) Gorman Towers,

Inc, v. Boqoslavsky, 626 F.2d 607 (8th Cir. 1980), and

Culebras Enterprises Corp. v. Rivera Rios, 813 F.2d 506 (1st

Cir. 1987), are similar to Weiss. Both courts rejected

conspiracy claims based on conduct taken to induce the

government to act. Eastern Railroad Presidents Conference v.

Noerr Motor Freight, Inc.. 365 U.S. 127 (1961), of course,

simply held that the Sherman Act does not extend to collec

tive efforts to secure favorable government action.

Board of County Commissioners of Adams County v.

Shrover. 662 F. Supp. 1542 (D. Colo. 1987), and Collin v.

Smith. 578 F.2d 1197 (7th Cir.), cert, denied. 439 U.S.

9/ By comparison, even before the Veteran decision and the

Article 78 proceeding challenging it, defendant COUP and

others filed a state court action in an effort to block

the West HELP development. (See Def. Mem. 2.)

Plaintiffs have made no claim that the filing of this

earlier suit was improper. That is because filing a

lawsuit usually is analogous to the opposition that

Weiss found protected. But see Mayer v. Wedgewood

Neighborhood Coalition, 707 F.2d 1020, 1022-23 (9th Cir.

1983) (filing of judicial proceeding is, in limited

circumstances, actionable under the civil rights laws).

32

916 (1978), are even further afield. In Shrover, the court

rejected a local government's attempt to silence a citizen-

critic — hardly a surprising result. Collin considered the

constitutionality of several Skokie, Illinois ordinances

passed to prevent Nazi marches. Isolated language from the

two cases, wrenched from their dramatically distinct factual

settings, does not support the Moving Defendants' privilege

argument.

In summary, the Moving Defendants cite no case

holding that a secessionist plan is constitutionally

protected. The relevant cases hold the opposite. There is

no First Amendment privilege to secede.

Ill

THERE IS A JUSTICIABLE CONTROVERSY

The Moving Defendants also mistakenly argue that no

case or controversy exists. They contend, in essence, that

there is no justiciable controversy until: (a) a favorable

vote is obtained, (b) Mayfair Knollwood is formed, and

(c) the new village thereafter either scuttles the West HELP

development or dilutes minority voting rights. (Def. Mem.

10-11.)

That simply is not the law. The secessionist plan

here is comparable to a ballot measure. Many courts have

recognized that the propriety of a ballot proposal presents

an actual case or controversy that may be adjudicated before

the vote.

For example, in Otev v. Common Council of the City

of Milwaukee. 281 F. Supp. 264 (E.D. Wis. 1968), a community

group presented petitions calling for a city council

resolution prohibiting anti-discrimination ordinances. State

law required the city council (called the "Common Council")

either to adopt the resolution or to submit it to the

electorate. The council resolved to put the proposed

resolution on the ballot, but took no position on its

constitutional merit.

Plaintiff, a black, sued for declaratory and

injunctive relief claiming, in substance, that adoption of

the resolution would violate Fourteenth Amendment rights. As

here, defendants argued that there was no case or

controversy. The court rejected the argument:

A controversy undoubtedly exists in this City between

the plaintiff and his class and those who seek to

deprive them of their right to equal protection of laws.

The Common Council is involved in this deprivation, and

it is clear from the record it will continue to be

involved adversely, should the resolution pass, by

refusing to consider action in contravention of its

terms. . . . If, under these circumstances, we have no

justiciable controversy, we have arrived at that

desolate state . . . where "community organization of

racial discrimination can be so featly managed as to

force the Court admiringly to confess that this time it

cannot tell where the pea is hidden." Id. at 274,

quoting Black, Foreword: "State Action," Equal

Protection and California's Proposition 14. 81 Harv. L.

Rev. 69, 95 (1967).

34

The court in Holmes v. Leadbetter, 294 F. Supp. 991

(E.D. Mich. 1968), reached the same holding on similar facts.

Again enjoining an unconstitutional ballot proposal, the

court wrote:

[W]e are satisfied that there is controversy between the

plaintiffs and the defendants. Id. at 993.

As the court in Holmes further explained:

The will of the electorate does not comprehend the will

to curtail or amend constitutional rights save in

constitutional convention or amendment tendered for such

purpose. Id. at 996.

Accordingly, some matters, the court wrote, simply are "no

longer one[s] for a public vote." Id.

The Mayfair Knollwood plan to secede falls into

this category. Indeed, this is an even stronger case for

relief than existed in Otev or Holmes. The mischief likely

to result from the Moving Defendants' plan to create an

outlaw government surely exceeds that likely to flow from

voter approval of an unconstitutional law. Accordingly,

there is a heightened need for judicial intervention. See

also Avtch v. Mitchell, supra, 320 F. Supp. 1372 (injunction

issued against vote to divide school district); Ellis v.

Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 234 F. Supp. 945 (D. Md.

1964) (three-judge court), aff'd on other grounds, 352 F.2d

123 (4th Cir. 1965) (injunction issued against vote on

35

reapportionment plan). Cf. Hamer v. Campbell, 358 F.2d 215,

221 (5th Cir.), cert, denied. 385 U.S. 851 (1966) ("[t]here

can be no question that a District Court has the power to

enjoin the holding of an election," particularly where neces

sary "to wipe out the effects of racial discrimination").

In Otev and Holmes. the defendants were city

officials. Both courts held that the constitutionality of

the ballot measure presented a justiciable controversy. It

necessarily follows that there also is a justiciable con

troversy in an action against both the relevant government

official (Supervisor Veteran) and the proponents who pre

sented the ballot measure (the Moving Defendants). For

instance, in Burleson, supra. 308 F. Supp. at 354 — arising

from an attempt to create a new school district — the court

directed joinder of "known proponents of the seces

sion . . . . See also Avtch v. Mitchell. supra.

320 F. Supp. at 1375 (court ordered joinder of persons

"responsible for circulating the petition" to divide the

school district); Matter of Fossella v. Dinkins, supra, 66

N.Y.2d 162 (1985), aff'q. 110 A.D.2d 227 (2d Dept. 1985)

10/ Before joinder, however, they intervened. Id.

36

(litigation between proponents and opponents of ballot

measure, which the court of appeals invalidated under state

law)

These authorities establish that there is a case or

controversy presented by the attempt to incorporate Mayfair

Knollwood. That Mr. Veteran denied the incorporation

petition is of no moment. The Moving Defendants do not claim

to have abandoned their scheme. Just the opposite: their

confederates filed an Article 78 proceeding in the Supreme

Court of the State of New York seeking to overturn the

Veteran decision, since removed to this court. (Himes Aff.,

Ex. B.)

Accordingly, there is a justiciable controversy

between plaintiffs "and those who seek to deprive them of

their rights to equal protection of laws." Otev. supra,

281 F. Supp. at 274.

11/ As with their First Amendment argument, the Moving

Defendants do little more than present selected "case or

controversy" language from decisions arising in

different fact contexts. (Def. Mem. 9.) Suffice it to

say that none of the cases cited stands for the proposi

tion that the federal court is disabled from ruling on

the validity of a secessionist plan (or other ballot

measure) before the vote.

37

PLAINTIFFS HAVE STANDING TO SUE

The Moving Defendants trifle with the court by

arguing that plaintiffs lack standing. (Def. Mem. 9.) There

is no merit to the Moving Defendants' argument that actual

injury is necessary in order to sue. A concrete threat of

specific injury is all that the law reguires, and that

standard is met here.

The individual plaintiffs — blacks and homeless

persons — are the targets of the conspiracy to secede. No

case holds that such targets lack standing to sue. The NAACP

and the National Coalition also have standing because the

challenged conduct affects their organizational activity.

A. The Threat of Injury

Is Sufficient_______

Cases in which standing is based on threatened —

but not actual — injury are commonplace. For example, in

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development. 429 U.S. 252 (1977), a developer planned to

IV

12/ With respect to standing, we are submitting affidavits

to supplement the complaint, as the cases permit. E.g..

Warth v. Seldin. 422 U.S. 490, 501 (1975). The

affidvits are included in the material entitled

"Plaintiffs' Affidavits in Opposition to Motions to

Dismiss or for Summary Judgment and for Attorneys' Fees

and Sanctions."

38

build racially integrated low and moderate income housing.

Resident protests resulted in the village denying the

necessary rezoning. The developer and three individuals

sued. The Supreme Court held that cne of the individuals,

Ransom, had standing to sue. Ransom lived 20 miles away from

the project site. He had no contract to lease, but he

alleged that he would qualify for the intended housing, and

"probably" would move there. IcL at 264. The Court held

that this was sufficient:

His is not a generalized grievance. Instead . . . , it

focuses on a particular project and is not dependent on

speculation about the possible actions of third parties

not before the Court. Id. (citation omitted).

Ransom plainly did not suffer actual injury from

the conduct challenged in Arlington Heights, a refusal to

rezone. But the refusal threatened to deprive him of an

opportunity to secure housing in the proposed development.

That potential injury was sufficient to confer standing.

Similarly, in United States v. SCRAP, 412 U.S. 669

(1973), an ad hoc group of students alleged that an ICC

railroad rate increase would "cause increased use of non-

recyclable commodities as compared to recyclable goods,"

which eventually would shift more resources into

manufacturing, which eventually would cause more litter in

the Washington, D.C. area parks that the students used. Id.

at 688. To describe the injury as "threatened" is to state

39

the obvious. The Supreme Court upheld standing to sue. See

also, e.g. , Blum v. Yaretsky. 457 U.S. 991, 1000 (1982)

(threat of injury confers standing); Pierce v. Society of

Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 536 (1925) ("[p]revention of impending

injury by unlawful action is a well recognized function of

courts of equity").

All the individual plaintiffs here are threatened

with deprivation of their rights. The Moving Defendants'

conspiracy has taken aim at the voting rights of some of the

plaintiffs and at the housing and shelter rights of the

others. Plaintiffs may sue now; they are not obliged to wait

for the Moving Defendants to pull the trigger. The principle

is a familiar one:

One does not have to await the consummation of

threatened injury to obtain a preventive relief. If the

injury is certainly impending that is enough.

Pennsylvania v. West Virginia. 262 U.S. 553, 593 (1923).

See also Otey, supra, 281 F. Supp. 264, and Holmes. supra.

294 F. Supp. 991 (plaintiffs permitted to sue to invalidate

discriminatory ballot measure before vote).

Section 1985(3) itself also includes an element of

"injury" or "deprivation" of rights. While we have found no

case directly on point, a threat of specific injury or

deprivation also should be sufficient to satisfy the statute.

Recognizing the sufficiency of threatened injury

would be consistent with the principle that, in a civil

40

rights action, where actual injury is not proven, nominal

damages still may be awarded. See, e .q ., Carey v. Piphus,

435 U.S. 247, 266 (1978); Bevah v. Coughlin, 789 F.2d 986,

989 (2d Cir. 1986); McKenna v. Peekskill Housing Authority,

647 F.2d 332, 336 (2d Cir. 1981). The nominal damage rule is

intended to emphasize the importance to society of the right

underlying the action. That purpose is well-served by

finding that threatened injury is sufficient to sustain a

civil rights conspiracy claim.

Indeed, to hold otherwise would enable plotting

conspirators who are caught red-handed to escape civil

liability by the fortuity of their having been discovered

before inflicting actual injury. Congress, we suggest, could

not have intended so bizarre a result. More likely, Congress

intended exactly what the Supreme Court has permitted:

exposure to suit and entry of a nominal damage award to

. 13 /stigmatize the civil rights violator.—

13/ The Moving Defendants cite Hermann v. Moore. 576 F.2d

453 (2d Cir. 1978), cert, denied. 439 U.S. 1003 (1978),

for the proposition that "a failed conspiracy is not

actionable" under various civil rights acts, including

§ 1985(3). (Def. Mem. 9.) The case does not hold that

at all. The Second Circuit found no conspiracy to

violate § 1985(3) — not that the conspiracy failed.

Other aspects of the decision have nothing to do with a

failed conspiracy.

41

In short, threatened injury is all that the

Constitution requires and this applies fully to § 1985(3).

We turn next to the standing of the three groups of

plaintiffs.

B. The Greenburqh Plaintiffs

The landmark case of Baker v. Carr. 369 U.S. 186

(1962), establishes that the Greenburgh Plaintiffs have

standing to challenge the conspiracy to violate their voting

rights. In Baker, one issue was whether voters had standing

to challenge state legislative measures affecting

apportionment. Plaintiffs alleged that the state's

"classification disfavors the voters in the counties in which

they reside, placing them in a position of constitutionally

unjustifiable inequality, vis-a-vis, voters in irrationally

favored counties." Id. at 207-208. Such impairment of a

citizen's right to vote, the Supreme Court held, conferred

standing. Id. Cf. Carey v. Klutznick■ 637 F.2d 834 (2d Cir.

1980) (voters had standing to challenge census count because

it diluted their vote).

Baker and Carey are concrete examples of the basic

proposition that economic injury is not a prerequisite for

standing; "[i]mpairment of rights guaranteed by the

Constitution may also constitute sufficient injury to confer

standing." Authors League v. Ass'n of American Publishers.

42

619 F. Supp. 798, 805 (S.D.N.Y. 1985), aff'd, 790 F.2d 220

(2d Cir. 1986) .

The Greenburgh Plaintiffs are threatened with such

injury here. As Gomillion held, a local government drawn

along lines of race cannot stand. Any government so created

makes an invidious — and constitutionally impermissible —

distinction between minority voters inside and outside of its

boundaries. Those on the outside are deprived of their

pre-existing right to vote on affairs of the local

government. Those few minority members inside are left with

a diluted vote. Both suffer an impairment of voting rights.

The Greenburgh Plaintiffs consist of black

residents inside and outside of the proposed village of

Mayfair Knollwood, who are qualified to vote. (Dixon Aff.

1 3; Jones Aff. f 3.) These individuals have standing to

attack a voting rights conspiracy formed by the Moving

Defendants

14/ Indeed, the threatened injury here is analogous to that

in the voter ballot measure cases, where the courts

enjoined the vote because the measure, if approved,

would be unconstitutional or unlawful. (See pp. 32-35,

supra.) The notion that a ward system might neutralize

the dilutive effect within Mayfair Knollwood is

immaterial. (Def. Mem. 13-14.) Those within the

proposed village, such as plaintiff Dixon, have a

constitutional right not to have their vote diluted to

begin with. A hypothetical remedy down the road to cure

(Continued)

43

That suffices to end any standing question. So

long as one plaintiff has standing to sue, it is immaterial

whether all do. See, e.g.. Village of Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development, supra. 429 U.S. at 264

n.9; Carev v . Population Services International, 431 U .S .

678, 682 (1977); Authors League, supra. 619 F. Supp. at

806. In any event, the Homeless Plaintiffs and the two

organizations also have standing.

C. The Homeless Plaintiffs

The Homeless Plaintiffs challenge the conspiracy to

violate their housing and shelter rights. Arlington Heights.

supra. 429 U.S. 252, discussed above, establishes their

standing to sue.

(Continued)

inevitable dilution is no answer — particularly when

the remedy depends on political will.

15/ In some cases, a claim-by-claim analysis of standing may

be appropriate. Here, however, it would not be because

the case involves a conspiracy with interrelated purposes.

The Supreme Court has cautioned that "the character and

effect of a conspiracy are not to be judged by dismember

ing it and viewing its separate parts but only by

looking at it as a whole." United States v. Patten.

226 U.S. 525, 544 (1913). See also Continental Ore

Co. v. Union Carbide & Carbon Corp.. 370 U.S. 690, 699

(1962). Thus, at trial, any plaintiff could prove the

full scope of the conspiracy. In these circumstances,

any possible need to establish standing on a claim-by-

claim basis dissolves.

44

The Homeless Plaintiffs are comparable to Ransom,

the possible tenant in Arlington Heights. Ransom had stanc

ing to challenge conduct that threatened to deny him the

opportunity for housing. Here, the conspiracy seeks to tor

pedo the West HELP shelter — thus similarly denying homeless

families with children, such as the Homeless Plaintiffs, the

opportunity for improved housing. (See Jordan Decl. 2, 4;

Myers Decl. 2, 4.) Accordingly, these plaintiffs have

standing. See also Bruce v. Department of Defense. Civil

No. 87-0425 (D.D.C. June 16, 1987) (homeless persons had

standing although unable to show entitlement to participate

in program challenged) (copy of decision attached as Himes

Aff., Ex. D); NAACP, Boston Chapter v. Harris, 607 F.2d 514,

525 (1st Cir. 1979) (minority group members had standing to

challenge HUD funding where "it can reasonably be inferred

from their complaint that they would accept such housing if

it were physically safe and financially accessible to them")

As to those Homeless Plaintiffs who are minors, the

Moving Defendants assert, without elaboration, that "there

13J In 11 Cornwell, the Second Circuit, in dicta, questioned

the ability of the individual retarded citizens to

establish standing. 695 F.2d at 40. The court's

remarks also might seem applicable here. With all

respect, the court overstated the difficulties.

Arlington Heights makes clear that the plaintiff must

face only loss of a specific beneficial opportunity;

actual loss of housing, as the Second Circuit seems to

have assumed, is not required.

45

appears a further complication. FRCP 17(c)." (Def.

Mem. 16.) We will not try to divine the undisclosed

"complication." Capacity to sue in federal court is

determined by the law of the party's domicile, and New York

authorizes minors to sue. See Fed. R. Civ. P. 17(b); 67 N.Y.

Jur. 2d "Infants and Others Persons Under Legal Disability"

§ 578 at 254. Moreover, the federal courts have construed

capacity to sue liberally. See. e.g.. Moe v. Dinkins.

533 F. Supp. 623, 627 (S.D.N.Y. 1981), aff'd. 669 F.2d 67 (2d

Cir. 1982), cert, denied. 459 U.S. 827 (1982) (minors

permitted to sue without guardians ad litem where there were

co-parties litigating and where minors' interests were

adequately protected by counsel).

Thus, whatever "complication" the Moving Defendants

are driving at, it is one of their own making that need not

further divert the Court.

D. The Organizational Plaintiffs

As to organizations, the basic inquiry is the same

as with an individual plaintiff; has the organization

claimed "such a personal stake in the outcome of the

controversy as to warrant his invocation of federal court

jurisdiction." Havens Realty Coro, v. Coleman. 455 U.S. 363,

378-79 (1982), emoting Arlington Heights, supra. 429 U.S. at

261 (emphasis omitted). The NAACP and the National Coalition

46

satisfy this standard because the challenged conduct affects

their organizational activity, thereby draining or diverting

their resources.

In Havens. HOME, an organization whose purpose

included assuring equal access to housing, sued under the

federal Fair Housing Act. HOME alleged that defendants'

racially discriminatory steering practices affected its

ability to provide counseling and referral services. The

Supreme Court held that "[s]uch concrete and demonstrable

injury to the organization's activities — with the

consequent drain on the organization's resources" -- was

sufficient for standing. 455 U.S. at 379.

Both the NAACP and the National Coalition have

standing here. Since 1909, the NAACP has spearheaded an

effort to establish and protect the civil rights of

minorities. The resource drain arising from the Moving

Defendants' frontal assault on the civil rights of black

residents of the Town of Greenburgh is plain. (Jones

Aff. tl 4-11.)

The National Coalition "advocate[s] responsible

solutions to end homelessness" and provides various monetary

aid and services to the homeless. (Complaint % 5k.) The

Moving Defendants' resistance to the West HELP development

clearly frustrates the National Coalition's goal to end

homelessness. In addition, their resistance causes the

47

National Coalition to provide a higher level of assistance

and support to homeless persons than would be necessary in

its absence. (Hombs Decl. ff 6-12.) See also 11 Cornwell,

supra, 695 F.2d at 39 n.l ("[sjurely if an association for

the mentally retarded were the party plaintiffs it would have

standing").

Thus, as many courts have found in the past, the

NAACP and the National Coalition have standing to sue. See,

e.g., NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) (statutory

challenge); Huntington Branch. NAACP v. Town of Huntington.

689 F .2d 391 (2d Cir. 1982), cert, denied. 460 U.S. 1069

(1983) (exclusionary zoning case); NAACP v. Harris. 567 F.

Supp. 637 (D. Mass. 1983) (housing discrimination case);

National Coalition for the Homeless v. U.S, Veterans1 Admin

istration . 695 F. Supp. 1226 (D.D.C. 1988) (agency failure to

comply with federal law); Younger v. Turnage. 677 F. Supp. 16

(D.D.C. 1988) (agency failure to issue benefit standards);

Bruce v. Department of Defense. Civil No. 87-0425 (D.D.C.

June 16, 1987) (agency failure to comply with federal law)

(copy of decision attached as Himes Aff. , Ex. D)

11/ As 11_Cornwell suggests, the National Coalition also has

standing to sue in a representational capacity on behalf

of Westchester County homeless families. Cf. Hunt v.

Washington State Apple Advertising Commission. 432 U.S.

(Continued)

48

* * *

Accordingly, all plaintiffs have standing to sue.

The NAACP and the National Coalition presently feel the

draining effect of the Mayfair Knollwood secessionist scheme.

As to the individual plaintiffs, the concrete threat of harm

that they face is all that the law requires.

E. Warth v. Seldin Is Inapplicable

Warth v. Seldin. 422 U.S. 490 (1975), is Moving

Defendants' only authority to support the argument that

plaintiffs lack standing. Warth. however, cannot carry all

the baggage that the Moving Defendants have piled on it.

There, the Supreme Court held that Rochester residents and

various organizations lacked standing to challenge the zoning

practices of a suburb. The decision turned on the abstract

quality of the controversy. No specific housing development

(Continued)

333, 343-45 (1977) (state agency had standing to sue on

behalf of apple growers); Barrows v. Jackson. 346 U.S.

249, 257 (1953) (standing recognized where "it would be

difficult if not impossible for persons whose rights are

asserted to present their grievance before any court");

NAACP v. Harris. 567 F. Supp. 637, 639-40 (D. Mass.

1983) (NAACP had standing to represent a constituency

different from its own membership). The NAACP similarly

has representational standing to assert its members'

voting and housing rights.

was involved. Consequently, tracing an alleged injury from

the exclusionary practices to plaintiffs was an exercise in

speculation. It also was impossible to envision a decree

that could afford plaintiffs specific relief.

Warth has been sharply criticized nonetheless "as

aberrational in the extreme. . . . " Tribe, American

Constitutional Law 134 (1988). In any event, it is not

dispositive here. Plaintiffs in this case challenge specific

conduct, including a concrete plan to secede, arising from

the proposed West HELP shelter. Causation is clear. An

injunction against the secession is one obvious form of

relief. Accordingly, Warth is inapplicable.

V

A CLAIM IS PLEADED AGAINST

DEFENDANT KAUFMAN

In his separate cross-motion, defendant Kaufman

seems to argue, albeit obliquely, that the allegations

against him fail adequately to allege his participation in a

conspiracy. (Kauf. Mem. 8.) But the requisite elements are

pleaded.

A complaint need only set forth facts tending to

show that a defendant was a member of the alleged conspiracy.

See generally Quinones v. Szorc. 771 F.2d 289, 291 (7th Cir.

1985); Hoffman v. Halden, 268 F.2d 280, 294-95 (9th Cir.

1959), overruled in part on other grounds. Cohen v. Norris,

50

300 F .2d 24, 29-30 (9th Cir. 1962). There is no requirement

that the defendant be charged with participating in all, or

even most, of the overt acts. Thus, as Judge Weinfeld once

noted in upholding a conspiracy claim:

That [defendant's] role in this conspiracy may have been

limited or slight is of no consequence. A conspirator

is liable for the acts of other members of the claimed

conspiracy as if they were his own, whether he plays a

minor or major role in the common scheme. Bridge C.A.T.

Scan Associates v. Ohio-Nuclear, Inc,. 608 F. Supp.

1187, 1191 (S.D.N.Y. 1985) (footnote omitted).

See also Kashi v. Gratsos, 790 F.2d 1050, 1054-55 (2d Cir.

1986) (holding member of a conspiracy liable for all damages,

despite allegedly limited role); Lumbard v. Maalia, Inc., 621

F. Supp. 1529, 1536 (S.D.N.Y. 1985) ("those who aid and abet

or conspire in tortious conduct are jointly and severally

liable with other participants in the tortious conduct,

regardless of the degree of their participation or

culpability in the overall scheme").

Here, the conspiracy is alleged. Defendant Kaufman

is charged specifically with agreeing to accept service of