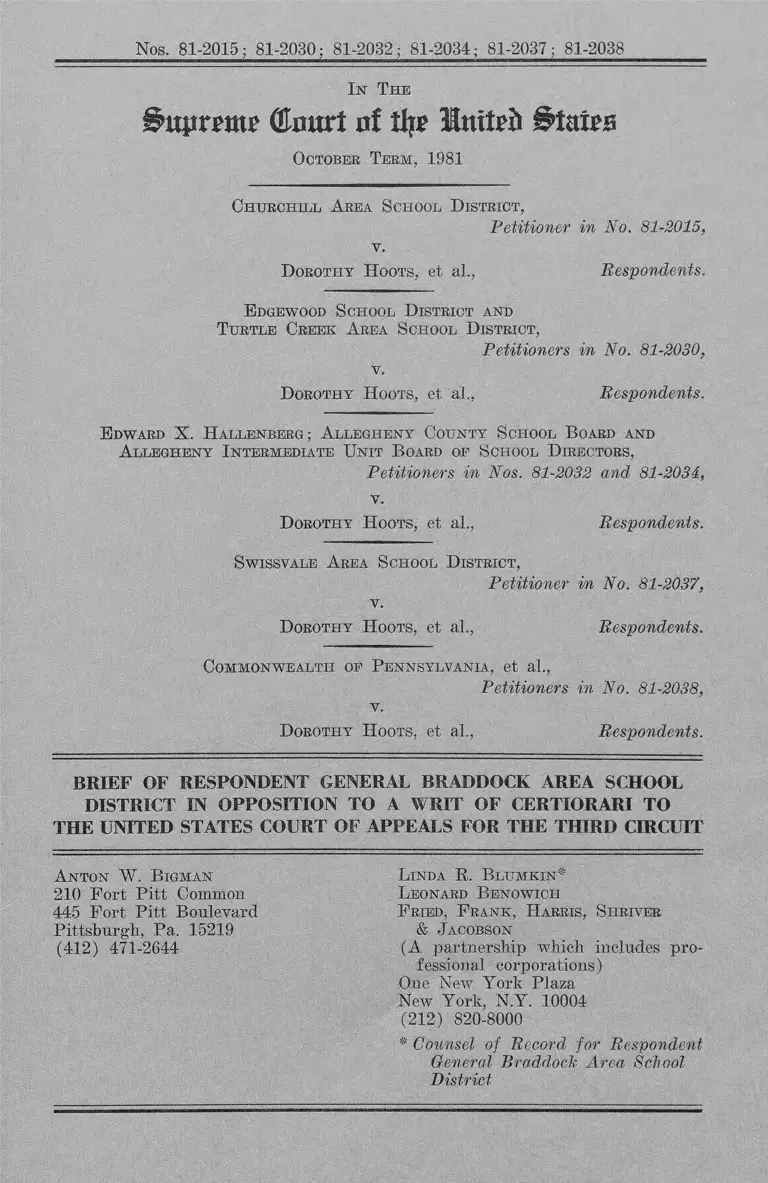

Churchill Area School District v. Hoots Brief of Respondent in Opposition to a Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Churchill Area School District v. Hoots Brief of Respondent in Opposition to a Writ of Certiorari, 1981. 9fde955b-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21c7ace0-1e31-44f1-8ee6-3dd0d085d2ad/churchill-area-school-district-v-hoots-brief-of-respondent-in-opposition-to-a-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Copied!

Nos. 81-2015; 81-2030; 81-2032; 81-2034; 81-2087; 81-2038

I n T h e

^uprirntr GJnurt of te IM tth States

October T e e m , 1981

C h u r c h il l A rea S chool D istr ic t ,

Petitioner in No. 81-2015,

v.

D orothy H oots, et al., Respondents.

E dgewood S chool D istr ict and

T u r t le Cr e e k A rea S chool D istr ict ,

Petitioners in No. 81-2030,

v.

D orothy H oots, et al.. Respondents.

E dward X . H a l l e n b e r g ; A ll e g h e n y Co un ty S chool B oard and

A ll e g h e n y I n term ed iate U n it B oard op S chool D irectors,

Petitioners in Nos. 81-2032 and 81-2034,

v.

D orothy H oots, et al., Respondents.

S w issv ale A rea S chool D istr ic t ,

Petitioner in No. 81-2037,

v.

D orothy H oots, et al., Respondents.

C om m onw ealth op P e n n sy lv a n ia , et al.,

Petitioners in No. 81-2038,

v.

D orothy H oots, et al., Respondents.

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT GENERAL BRADDOCK AREA SCHOOL

DISTRICT IN OPPOSITION TO A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO

THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

A nto n W . B igm an

210 Fort Pitt Common

445 Fort Pitt Boulevard

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15219

(412) 471-2644

L inda R. B l u m k in *

L eonard B enow ich

F ried , F r a n k , H arris, S iiriver

& J acobson

(A partnership which includes pro

fessional corporations)

One New York Plaza

New York, N.Y. 10004

(212) 820-8000

# Counsel of Record for Respondent

General Braddock Area School

District

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Did the court of appeals cor

rectly affirm the district court's finding

that the school authorities' establishment

of a black school district surrounded by

white districts constituted de jure segrega

tion in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment?

2. Did the court of appeals cor

rectly affirm the district court's order

consolidating the black school district

with four surrounding white districts to

remedy the constitutional violation?

PARTIES BELOW

Dorothy Hoots, individually and as mother

of her children Janelle Hoots and Jamie

Hoots; Mrs. Addrallace Knight, individually

and as mother and natural guardian of her

children Ronald Knight, Loretta Knight,

Terrance Knight, Marc Knight and Byron

1

Knight; Barbara Smith, individually and as

mother and natural guardian of her children

Tawanda Smith, Tevela Smith, Joseph Smith,

Wesley Smith and Eric Smith; General Braddock

Area School District;

Appellees;

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania; Pennsylvania

State Board of Education and its Chairman,

W. Deming Lewis; Allegheny Intermediate

Board of School Directors, and its Presi

dent, Edward X. Hallenberg; Churchill Area

School District; Edgewood School District,

Swissvale Area School District; Turtle

Creek Area School District;

Appellants.

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Questions Presented ................. i

Parties Below ........................ i

Table of C o n t e n t s .............. .. . iii

Table of A u t h o r i t i e s .......... v

Opinions Below ....................... viii

Jurisdiction ........................ ix

Constitutional and Statutory

Provisions I n v o l v e d ......... .. . ix

Statement of the Case . . ......... 1

A. The Consolidation Process . . 3

B. The L i t i g a t i o n .......... 1 3

Summary of A r g u m e n t ............ 22

Reasons for Denying the Writ . . . 26

I. THE DISTRICT COURT AND

THE COURT OF APPEALS

PROPERLY APPLIED THIS

COURT'S WELL ESTABLISHED

STANDARDS REQUIRING PROOF

OF INTENTIONAL DISCRIMI

NATION ........................ 26

II. HAVING FOUND A CONSTITU

TIONAL VIOLATION, THE DIS

TRICT COURT APPLIED THE

iii

Page

APPROPRIATE STANDARDS

ESTABLISHED BY THIS COURT

IN FASHIONING AN INTER

DISTRICT REMEDY INVOLVING

ONLY THOSE DISTRICTS FOUND

TO HAVE BEEN INVOLVED IN OR

AFFECTED BY THE VIOLATION. . . 40

Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES PAGE

Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979)..... 26-27,33

Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406 (1977)..... 47

Evans v. Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750

(3d Cir. 1978) (en banc), cert.

denied, 446 U.S. 923 (1980)....... 49

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

334 F. Supp. 820 (W.D. Pa. 1971).. passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

359 F. Supp. 807 (W.D. Pa. 1973).. passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

495 F .2d 1095 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

419 U.S. 884 (1974)............. ... 1,16-17

Hoots v. Commmonwealth of Pennsylvania,

587 F .2d 1340 (3d Cir. 1978)....... 1,19

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

639 F . 2d 972 (3d Cir. 1981)....... 1,19

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

510 F. Supp. 615 (W.D. Pa. 1981).. passim

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

No. 71-258 (W.D. Pa. April 16,

1981)................................. 2

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

No. 71-258 (W.D. Pa. April 28,

1981)................................. passim

v

CASES (continued) PAGE

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

672 F .2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982).,.... passim

Hoots v. Weber, No. 79-1474 (3d Cir.

May 2, 1979)................. 19

Hoots v. Weber, No. 80-2124 (3d

Cir. September 9, 1980)........... 19

Keyes v. School District No, 1 , 413

U.S. 189 (1973)........... passim

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717

(1974) ........................ passim

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267

(1977) ....................... 45

Morgan Guaranty Trust Co. v. Martin,

466 F .2d 593 (7th Cir. 1972)...... 17

Morrilton v. United States, 606 F.2d

222 (8th Cir. 1979), cert, denied,

444 U.S. 1071 (1980).............. 43,46

Mt. Healthy City Board of Education

v. Doyle, 429 U.S. 274 (1977)..... 37

Provident Tradesmens Bank and

Trust Co. v. Patterson, 390 U.S.

102 (1968)___ .................... 17

Swann v. Charlotte - Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971)..................... ......... 40,45

vi

CASES (continued) PAGE

United States v. Board o f School

Commisioners, 573 F.2d 400 (7th

Cir .) , cert. denied, sub nom.,

Bowen v. United States , 439 U .S .

824 (1978)........................... 43

United States v. State of Missouri ,

515 F .2d 1365 (8th Cir. 1975)..... 44

Village of Arlington Heights v .

Metropolitan Housing Development

Corporation, 429 U.S. 252

(1977)........................... passim

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229

(1976)................................ 26

STATUTES

42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983................ 13

Public School Code of 1949, Act

of March 10, 1949, P.L. 30, Art.

2, 201, 24 P.S. §2-201.............. 3-4

Act of September 12, 1961, P.L.

1283, No. 561, 24 P.S. §2-281

et seq. [Act 561]................... 3,5-7

Act of August 8, 1963, P.L. 564,

No. 299, 24 P.S. §2-290 et seq.

[Act 299]........................... 3,6,7,9

Act of July 8, 1968, P.L. 299,

No. 150, 24 P.S. §2400.1 et seq.

[Act 150]......................... 3,9,10,15

v n

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Third Circuit

affirming the district court in all re

spects is reported at Hoots v. Commonwealth

of Pennsylvania, 672 F.2d 1107 (1982) . The

district court's opinion finding a constitu

tional violation is reported at Hoots v.

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 359 F. Supp.

807 (W.D. Pa. 1973). One of the district

court's two opinions on the remedy ordered

in this case is reported at Hoots v. Com

monwealth of Pennsylvania, 510 F. Supp. 615

(W.D. Pa. 1981). The other decision is

unpublished, but has been reprinted as Ap

pendix E to the Joint Appendix filed by

Swissvale Area School District, Bdgewood

School District and Turtle Creek Area

School District.

v i i i

JURISDICTION

This Court has jurisdiction to re

view the final judgment of the Third Cir

cuit, entered on February 1, 1982, pursuant

to 28 U.S.C. §1254 (1) .

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

United States Constitution, Four

teenth Amendment, Section 1:

"All persons born or

naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction

thereof, are citizens of the

United States and of the State

wherein they reside. No State

shall make or enforce any law

which shall abridge the privi

leges or immunities of citizens

of the United States; nor shall

any State deprive any person of

life, liberty or property without

due process of law; nor deny to

any person within its jurisdic

tion the equal protection of the

law."

Rule 19(a), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure.

IX

24 P.S. §2-281, et seq. (Act 561)

24 P.S. §2-290, et seq. (Act 299)

24 P.S. §2-2400.1, et seq.

(Act 150).

Standards for Reorganization

under Act 299.

Standards for Reorganization

under Act 150.

The texts of Rule 1 9 (a) , Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure, relevant Pennsyl

vania statutes, and the Standards of Reorga

nization of school districts are set forth

in Appendix D to the Churchill Area School

District's Petition for Certiorari.

x

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This lawsuit was commenced in

1971 to correct a condition of intentional

de jure segregation brought about as a re

sult of the statutorily mandated consolida

tion of school districts in the central

eastern area of Allegheny County, east of

Pittsburgh.^ This brief is submitted by

This case has been extensively re

ported. The principal decisions to

which reference will be made are:

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

334 F. Supp. 820 (W.D. Pa. 1971)

(Hoots I)

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

359 F. Supp. 807 (W.D. Pa. 1973)

(Hoots II)

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

495 F.2d 1095 (3d Cir.), cert, denied,

419 U.S. 884 (1974) (Hoots III)

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

587 F .2d 1340 (3d Cir. 1980)

(Hoots IV)

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

639 F .2d 972 (3d Cir. 1981) (Hoots V )

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

510 F. Supp. 615 (W.D. Pa. 1981)

(Hoots V I )

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

(Footnote Continued)

1

respondent General Braddock Area School

District ("General Braddock") whose

"intentional creation as a racially identi

fiable black school district constituted

the constitutional violation found in this

case." Hoots VIII, (892a).1 2

The complaint in this case did

not allege, and respondents have never as

serted that there was de jure school segre

gation in Pennsylvania prior to the statu

tory program of mandatory school district

1 (Footnote Continued)

No. 71-258 (W.D. Pa. April 16, 1981)

(Hoots VII)

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

No. 71-258 (W.D. Pa. April 28, 1981)

(Hoots VIII)

Hoots v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania,

672 F .2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982)

(Hoots IX) .

2 All citations in the form "(___ a)"

refer to the page in the record on ap

peal to the Third Circuit.

2

consolidation which began in 1961. Rather,

the complaint alleged, and the district

court and court of appeals found, that it

was the entire process by which the

boundaries of the school districts in this

portion of central eastern Allegheny County

were redrawn that constituted the constitu

tional violation and gave rise to the condi

tion of de jure segregation found, and

remedied, by the district court.

A . The Consolidation Process

The consolidation program was

mandated by a series of related statutes:

the Act of September 12, 1961, P.L. 1283,

No. 561, 24 P.S. §2-281 et seg. (Act 561);

the Act of August 8, 1963, P.L. 564, No.

299, 24 P.S. §2-290 et seq. (Act 299); and

the Act of July 8, 1968, P.L. 299, No. 150,

24 P.S. §2400.1 et seq. (Act 150). Prior

to Act 561, the Public School Code of 1949,

3

Act of March 10, 1949, P.L. 30, Art. 2,

§201, 24 P.S. §2-201 (as amended) provided

that each city, incorporated town, borough

or township shall constitute a separate

school district. Thus, school districts

generally were coterminous with municipalities.

Over the period of consolidation,

the relevant state and county boards combined

white districts with one another -- or left

them independent — rather than join them

with one or more of General Braddock's

three predecessor districts. As part of

the constitutional violation alleged and

proven in this case, the white districts lo

cated near General Braddock's predecessor

districts of Braddock, North Braddock and

Rankin, were removed seriatim from consider

ation as possible merger candidates.

On December 18, 1962 the Allegheny

County Board of School Directors ("County

4

Board") adopted a school reorganization

plan pursuant to Act 561. This proposal

recommended the consolidation of the following

school districts: Braddock (36.16% black);3

North Braddock (11.02% black); Rankin (35.39%

black); East Pittsburgh (3.85% black); and

Braddock Hills (11.75% black).4 Despite

The figures set out in parentheses

reflect the percentage of non-white

population in the identified school

district as of 1970. See, Hoots I I ,

359 F. Supp. at 816. The non-white

enrollments as of 1964 for each district,

to the extent they are available are

as follows: Braddock - 57%; Churchill-

0.16%; East Pittsburgh - 14%; Edgewood-

0.00%; North Braddock - 14%; Rankin-

46%; Swissvale - 5.5%; Turtle Creek-

0.00%. See, exhibit 17 (331a-337a).

The admissibility of this exhibit was

stipulated to. (703a).

By the end of the reorganization pro

cess, after all the other neighboring

districts had been consolidated with

one another or allowed to remain inde

pendent, Rankin, Braddock and North

Braddock were consolidated to form

General Braddock. 359 F. Supp. at

819.

5

its adoption by the County Board, this plan

was not reviewed by the State Board of Educa

tion (the "State Board") and could not be

effectuated because Act 561 was superseded

by Act 299. (696a). Had this proposal been

adopted, the population of the new district

would have been less than 30% black. S e e ,

Hoots I I , 359 F . Supp. at 816, finding of

fact 35.5

On May 11, 1964, pursuant to Act

General Braddock does not suggest that

this particular consolidation of dis

tricts would have been free of consti

tutional imped intent. Rather, the ra

cial statistics that would have result

ed from various formally proposed (but

ultimately abandoned or rejected) com

binations are cited merely to under

line, as the district court found, 359

F. Supp. at 819, that the creation of

General Braddock resulted in the highest

possible percentage of minority popula

tion and that specific proposals which

would have resulted in less segregation

were killed during the consolidation

process.

6

299, the County Board proposed the consoli

dation of Braddock, North Braddock, Rankin,

Turtle Creek (0.18% black) and East Pittsburgh.

(696a). Although the Braddock and Rankin

districts supported this proposal, it was

opposed by Turtle Creek and East Pittsburgh

— both of which immediately appealed to

the State Board seeking a modification of

the proposal — and by North Braddock. The

East Pittsburgh-Turtle Creek appeal was

heard on October 23, 1964; the hearing on

North Braddock's opposition to the Plan was

held on March 24, 1965. Even without the

inclusion of Braddock Hills — which had

been suggested in the County Board's proposal

under Act 561 -- the student population in

this district, in 1967, would have been in

excess of 73% white. Hoots I I , 359 F. Supp.

at 817, finding of fact 42.

At the March 24, 1965 hearing,

7

James Rowland, a member of the State Board,

inquired as to the racial composition of

the schools involved in the County Board's

proposal. There was testimony at that

hearing showing that in Braddock, one

elementary school was 55% black, while a

second was 95% black; the junior high school

was 80% black, while the high school was 40%

black. In Rankin the high school was 40%,

and the elementary school 51% black. In

North Braddock the schools were approxi

mately 8 or 9% black, with Braddock Hills

approximating 10% black. (697a~698a). In

East Pittsburgh the black school population

approximated 6% as of 1967 (332a), while

Turtle Creek at that time had no blacks

attending its schools. I d . Turtle Creek

and East Pittsburgh suggested that they

be merged to form their own district, or,

in the alternative, that they be

8

included in another district, such as

Churchill (0.11% black).6

On November 25, 1965 the State

Board granted the Turtle Creek-East

Pittsburgh request and merged them into a

separate district. This district was con

solidated under Act 150 which superseded,

with few substantive changes, Act 299.

(699a).7

Churchill was formed on July 1, 1966

through consolidation of Forest Hills

(0.27% black), Wilkins Township (0.56%

black) and Chalfont (0.88% black) under

Act 299. As a matter of state law, as

it concedes, Churchill Petition at

4, it was, under Act 299, as it had been

under Act 561, available for additional

consolidation. Churchill's formation

as an essentially all-white district,

and its subsequent nonjoinder with neighboring

districts during the subsequent stages

of the reorganization process were pursuant

to the constitutional violation found

here.

Both Act 299 and Act 150 provided that

the County Board's proposals and the

State Board's review and consideration

(Footnote Continued)

9

On October 7, 1968, pursuant to

Act 150, the County Board adopted a reorga

nization plan proposing the consolidation

of Braddock, North Braddock and Rankin into

a single district; the consolidation of

East Pittsburgh and Turtle Creek into a sin

gle district; the consolidation of

Swissvale and Braddock Hills into another

district; and that Edgewood district (1.29%

black) should remain as a separate school

district. (700a) .

On September 14, 1968, however,

prior to the adoption of this proposal, the

County Board conducted hearings at which 7

7 (Footnote Continued)

of such proposals were to be in confor

mity with certain statutory and admin

istrative standards and guidelines re

lating to the ability of any newly con

solidated district to provide a compre

hensive education. Hoots I I , 359 F.

Supp. at 812, finding of fact 11.

10

Braddock, North Braddock and Rankin opposed

the proposal consolidating them into a sin

gle district. The testimony at that hear

ing showed that: (1) the creation of a

larger district was necessary given the un

sound financial position of the three

districts; (2) there would be an extreme ec

onomic burden placed on North Braddock and

upon Rankin, especially in light of

Rankin's substantial indebtedness; and (3)

the resulting district would be racially

imbalanced because it would consist of a

pupil population in excess of 45% black,

while the adjacent school district result

ing from the East Pittsburgh-Turtle Creek

consolidation would have a pupil population

less than 5% black. (700a-701a). After

the County Board adopted the proposal not

withstanding the testimony presented at the

September hearings, Braddock, North

11

Braddock and Rankin appealed to the State

Board for a modification of the proposal.

A hearing before the State Board was held

on February 25, 1969, at which time the State

Board admitted into its record enrollment

statistics prepared by the Human Relations

Commission of Pennsylvania, broken down by

race, for each school district of Allegheny

County. On May 9, 1969 the State Board upheld

the consolidation of Braddock, North Braddock

and Rankin into one district -- General Brad

dock, the present respondent. (702a).

General Braddock was created as

of July 1, 1971. Before the end of the

first school year following the consolida

tion, the school district was found to be

distressed — bankrupt — by the Allegheny

County Court of Common Pleas, in April of

1972. In Hoots VIII, almost a full decade

after General Braddock had been established,

12

the district court, in its decision

imposing the remedy, found that the student

population of General Braddock in April of

1981 was 63% black. (892a).

B . The Litigation

Plaintiffs commenced this action

on June 9, 1971 alleging that their rights

under the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment and under the Federal

Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983

had been violated. In December of 1971 the

district court denied the defendants' mo

tion to dismiss stating there was "no doubt

that the allegations of deliberate creation

of a racially segregated school district

state a cause of action". Hoots I , 334 F.

Supp. 820, 822. In addition, although the

district court denied the defendants' mo

tion for the compulsory joinder of the indi

vidual school districts as indispensable

13

parties, it noted that the districts would

be permitted to intervene if they so chose

and "insisted [the Commonwealth] give them

notice" of the suit. Id. at 821, 823. De

spite a written request by the Attorney

General of Pennsylvania urging them to

"intervene in this action immediately,'’ the

districts chose not to intervene and in

formed the court that they had "no interest

in being" in the lawsuit, and were "delib

erately not intervening." ^d. at 821.v

The trial of this action began on

December 5, 1972. On May 15, 1973 the dis

trict court held that General Braddock,

"racially identifiable as a black school

district," Hoots I I , 359 F. Supp. at 817,

finding of fact 40, was created as the re

sult of intentional racial segregation. The

district court held that the State and

County Boards "knew or should have known

14

they were creating a racially segregated

school district as of the dates they pro

posed and approved" of General Braddock.

Id. at 818, finding of fact 50. Indeed,

while noting that the "natural foreseeable

and actual effect of combining Braddock,

North Braddock and Rankin into one school

district was to perpetuate, exacerbate and

maximize racial segregation" within the

area, id. at 821, finding of fact 57, the

district court specifically found that as

of the time the Boards proposed and ap

proved the consolidation plans, "no other

combination of school districts within this

portion of Allegheny County would have cre

ated a school district (of at least 4,000

pupils as required by Act 150) with as

large a percentage of nonwhite enrollment."

Id. at 819, finding of fact 51. The court

ordered the Commonwealth defendants to

15

prepare a comprehensive plan of desegregation

which plan would "alter the boundary lines

of the General Braddock Area School Dis

trict and, as appropriate, of adjacent

and/or nearby school districts." I d . at

824.

It was not until June 1973, some

six months after the trial had ended, that

Turtle Creek and Churchill sought to inter

vene and be heard on the question of the

constitutional violation, already ruled

upon by the district court. The district

court denied the motions as untimely, and

the Third Circuit affirmed their denial.

Hoots III, 495 F .2d 1095 (3d C i r .), cert.

denied, 419 U.S. 884 (1 9 7 4 ).8 while the ap-

Petitioners are still trying to

relitigate the law of the case with re

spect to their untimely intervention

attempt. Although the school dis

tricts had "clear warning" early on

(Footnote Continued)

16

peal was pending, Turtle Creek and

(Footnote Continued)

from the Commonwealth’s Attorney-

General of the "likely necessity for

intervention," they made a deliberate

choice not to appear. Hoots III, 495

F.2d at 1097. Even if the peti

tioner districts met the standards for

necessary or indispensable parties,

which General Braddock denies and the

district court correctly refused to

find, Hoots I , 334 F. Supp. 820, their

nonjoinder was harmless error because

of their deliberate choice to reject

the court's contemporaneous offer of

intervenor status. Moreover, the courts

have refused to countenance such dilatory

conduct. S e e , e.g., Provident Tradesmens

Bank and Trust Co. v. Patterson, 390

U . S . 102 (1968); Morgan Guaranty Trust

Co. v. Martin, 466 F.2d 593 (7th Cir.

1972) (holding that one who knows of

the pendency of an action which may affect

his interests and specifically disclaims

an interest in the action will not be

regarded as an indispensable party).

In any event, the districts had the op

portunity — ■ of which they availed them

selves — to submit evidence with re

spect to liability during the remedy

hearings. That evidence — notably the

testimony of Dr. Paul Christman, Chairman

of the State Board (2701a-2705a, 2737a,

2761a- 2762a), — strongly supported,

(Footnote Continued)

17

Churchill were joined by the other school

districts, who sought to intervene and be

heard on the desegregation plan submitted

by the Commonwealth in compliance with the

court's order. The district court permit

ted intervention on the question of remedy.

Over the course of seven years,

from 1973 to 1980, the district court held

extensive hearings on various consolidation

and other types of plans proposed by the

Commonwealth. Throughout this remedial pe-

riod, plaintiffs attempted to appeal to the

Third Circuit in order to obtain relief.

The first appeal, from an order denying ap

proval of one of the Commonwealth's consoli-

(Footnote Continued)

rather than negated, the District Court's

liability holding in Hoots II and was

before the court when it explicitly reaffirmed

its liability decision in Hoots I I ,

in light of Keyes. (2739a, 2761a).

18

dation plans, was dismissed for lack of ap

pellate jurisdiction. Hoots I V , 587 f .2d

1340 (3d Cir. 1978). Subsequently, on two

occasions, plaintiffs sought an order of

mandamus from the court of appeals direct

ing the imposition of a remedy. Hoots v.

Weber, No. 79-1474 (3d Cir. May 2, 1979);

Hoots v. Weber, No. 80-2124 (3d Cir. September

9, 1980). In a second appeal, the Third

Circuit directed the district court to expe

dite its consideration of the remedial ques

tions before it so as to issue a remedy

within 90 days, in order to implement that

plan for the 1981-1982 school year. Hoots V,

639 F.2d 972 (3d Cir. 1981) .

In an opinion issued on March 5,

1981, the district court reaffirmed its

findings and conclusions issued in 1973,

and stated that an interdistrict remedy

could properly include those school

19

districts adjacent or near to General

Braddock. Rejecting the districts' argu

ments that they were not involved in the vi

olation and therefore could not be implicat

ed in such a remedy, the district court

held that H [a] multidistrict remedy can be

applied to surrounding districts that have

not been found to have committed a constitu

tional violation themselves where their

boundaries were drawn or redrawn during the

course of the same violation which created

the segregated school districts." Hoots V I ,

510 F. Supp. 615, 619. On April 28, 1981,

after additional hearings, the district

court ordered that certain districts

neighboring General Braddock — petitioners

— be consolidated and merged into a single

school district, known as the Woodland

Hills School District.

Petitioners appealed from the

20

district court's order directing the imposi

tion of this remedy. Petitioners also ap

pealed the court's findings of segregative

intent on the part of the State and County

Boards in the creation of General Braddock.

On February 1, 1982, the Third Circuit af

firmed the district court in all respects.

Hoots I X , 672 F .2d 1107 (3d Cir. 1982).

With respect to the issue of the standard

applied by the district court to determine

whether a constitutional violation oc

curred, the court of appeals held that

"there is no question that the district

court utilized the correct legal standard

— [the requirement of proof of] inten

tional or purposeful segregation," 3h3. at

1116. With respect to the propriety of the

remedy, the court of appeals held that the

district court "tailored the relief granted

to fit the actual showing of de jure

21

discrimination by all of the districts in

volved. Indeed, the remedy fashioned by the

district court here was narrowly drawn."

I d . at 1120. And, the court held that "the

district court did not abuse its discretion

in fashioning its multidistrict remedy. in

deed, the district court's action fully complied;

with all applicable standards and was support

ed by more than enough evidence." Id. at 1124.

It is from the judgment of the

Third Circuit that petitioners seek a writ

of certiorari.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Certiorari is inappropriate in

this case because the lower courts have cor

rectly applied well-established Supreme

Court precedent. There are no novel issues

of law nor conflicting circuit court deci

sions requiring this Court's resolution.

Certiorari has consistently been denied in

22

recent cases raising the same arguments on

similar facts.

The lower courts properly applied

the standard of segregative intent set

forth in Keyes v. School District No._1,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) and succeeding cases

and the remedial rule of Milliken v.

Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) and its

progeny. Petitioners' efforts to frame

eyecatching issues notwithstanding, the

lower courts did not hold: that intent can

be based solely on foreseeability of dispar

ate impact,^ that a difference in racial

mix alone violates the Equal Protection

Clause,10 or that a failure to maximize de-

Commonwealth Petition at i.

Churchill Petition at i; Hallenberg

and County School Board Petitions at

i .

23

segregation alone is unlawful.H Nor did

the lower courts impose a remedy on school

districts not "involved" in the constitu

tional violation.12

Rather, on the basis of all the

evidence, the district court found -- and

the circuit court affirmed -- that the

plaintiff's established a legally sufficient

case of intentional discrimination that the

school authorities failed to rebut. More

over, the district court properly fashioned

— and the circuit court affirmed -- an

interdistrict remedy including only those

districts the establishment of which derived

from the unlawful line-drawing process and

which were thus irrefutably "involved" in 11 12

11 Edgewood-Turtie Creek Petition at i.

12 See Churchill Petition at i; Swissvale

Petition at i; Hallenberg and County

School Board Petitions at i.

2 4

the violation.

Prior to the consolidations at

issue, there were fifteen rather than five

school districts in the relevant part of

central eastern Allegheny County. The Com

monwealth of Pennsylvania, not this case,

abolished those traditional boundaries.

Once the Commonwealth undertook redis

tricting, it assumed the burden of act

ing without racial bias. Because the Com

monwealth failed to meet that responsibil

ity, the remedial powers of the federal

courts were properly brought to bear.

25

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT AND THE COURT OF

APPEALS PROPERLY APPLIED THIS COURT'S

WELL ESTABLISHED STANDARDS REQUIRING

PROOF OF INTENTIONAL DISCRIMINATION

The applicable standard for prov

ing segregative intent in Northern school

desegregation cases is clearly set forth,

for present purposes, in the decisions of

this Court, including Keyes v. School Dis

trict No. 1 , 413 U.S. 189 (1973);

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976);

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropoli

tan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977); and Columbus Board of Education

v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449 (1979). These

cases teach that discriminatory intent may

be established through the use of presump

tions and inferences as well as direct and

circumstantial evidence. See, e.g,,

Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 242

26

("an invidious discriminatory purpose may

often be inferred from the totality of the

relevant facts.").; Arlington Heights,

supra, 429 U.S. at 266 ("Determining

whether invidious discriminatory purpose

was a motivating factor demands a sensitive

inquiry into such circumstantial and direct

evidence of intent as may be available.");

Columbus Bd. of E d . , supra, 443 U.S. at

464 ("actions having foreseeable and antici

pated disparate impact are relevant evi

dence to prove the ultimate fact, forbidden

purpose."). They require that plaintiffs

establish merely that race was "a" factor,

and not the "sole" or "predominant" factor,

in order to make out a prima facie case of

a constitutional violation. Arlington

Heights, supra, 429 U.S. at 265 ("Davis

does not require a plaintiff to prove that

the challenged action rests solely on

27

racially discriminatory purposes.").

Despite the fact that the dis

trict court's May 15, 1973 decision, Hoots

I I , 359 F. Supp. 807, setting forth its

findings of fact and conclusions of law was

banded down prior to this Court's decision

in Keyes, it is clear that the district

court nevertheless applied the appropriate

standard. At the outset of this case, for

example, the district court denied the de-

V-

fondants' motion to dismiss because it

recognized that the complaint alleged that

" [i] n preparing and adopting the school re

organization plans defendants intentionally

and knowingly created racially segregated

school districts." Hoots I , 334 F. Supp.

at 821-822. And, in Hoots I I , its first

decision on the merits, the district court

concluded that:

A violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment has occurred when public

28

school authorities have made educa

tional policy decisions which were

based wholly or in part on considera

tions of the race of students and

which contributed to increasing

racial segregation in the public

schools.

359 F. Supp. at 822. As the Third Circuit

noted, "This is the language of intention

and purpose." 672 F.2d at 1115. Addition

ally, on October 24, 1975, after Keyes was

handed down, the district court permitted

additional testimony and argument on the

violation issue. In the course of these

hearings, counsel for Churchill asserted

that the district court "would have come to

a different conclusion if [it] were making

[its] Order on those facts after Keyes".

The district court flatly disagreed, noting

that "this is one place where you can say

[you are] 100 percent wrong." (2739a). In

deed, the court that day, after a review of

the issue, reaffirmed its earlier finding

29

of a "purposefully" segregated school dis

trict. (2761a).

In addition to applying the appro

priate legal standard, the district court

found ample evidence in the record to sup

port its finding of purposeful segregation.

The court of appeals reviewed no fewer than

nine facts or inferences found by the dis

trict court. These included the following:

(1) testimony from a local school official

that he and others had pressured the State

and County Boards to insulate the white dis

tricts from the others because of "the

black issue"; (2) evidence of a State Board

staff report that racial considerations in

fluenced and motivated the opposition of

certain districts to a merger with Braddock

Rankin and North Braddock; (3) a statement

tending to indicate that the County Board

did not consider Churchill for any merger

30

because Churchill opposed such moves on the

basis of racial concerns; (4) a statement

by the president of the County Board that

the Board was "painfully aware of [the fact]

that . . . over the years the surrounding

school districts had sought to avoid a school

merger which would include Braddock and Rankin

in their school district and that it looked

like [North] Braddock was going to be 'left

holding the bag'." 672 F.2d at 1115-1118.

Based on these and other findings,

the district court found that the State and

County Boards were influenced by the mani

fest desires of the surrounding communities

"to avoid being placed in a school district

with Braddock and Rankin because of the high

concentration of blacks within these two

municipalities." 359 F. Supp. at 821. Con

sequently, the district court concluded

that "race was a factor" in the formation

31

of General Braddock. 359 F. Supp. at 821,

reaffirmed, 510 F. Supp. at 619.; Hoots I X ,

672 F.2d at 1116. In addition, it found

"no evidence" that the consolidation plans

or the configuration of the school dis

tricts were "rationally related to any le

gitimate purpose and [that] . . . those

boundaries did not promote any valid state

interest." 510 F. Supp. at 619, reaffirming

359 F. Supp. at 821, 822.

The district court found it sig

nificant that the State and County Boards

disregarded many of the statutory and admin

istrative guidelines established in order

to facilitate the creation of school dis

tricts capable of providing abusive educa

tion. 359 F. Supp. at 819-20, finding of

fact 52. Perhaps the most telling example

of this point is that except for Churchill

and General Braddock, each of the other

32

districts was created with less than the

minimum number of students required by the

guidelines. Id.

Thus, in addition to the direct

and circumstantial evidence and the permis

sible findings of foreseeable effect, see,

Columbus Bd, of Ed., supra, the conscious,

systematic departures from the established

guidelines, see, Arlington Heights, supra,

provide ample evidence that the district

court properly required proof of purposeful

intent and that such proof, both direct and

inferential, was and continues to be permis

sible evidence under the decisions of this

Court. _Id. There is no serious question

that the district court properly considered

and weighed the direct and circumstantial

evidence presented to it. As the court of

appeals found, after conducting its own ex

haustive review of the record:

33

The district court properly

weighed evidence such as [1] the

Board members' admitted knowledge

that their redistricting deci

sions would cause and perpetuate

segregation, [2] the fore

seeability of the segregative re

sult, [3] the Boards' formulation

of boundaries that promoted no in

terest other than racial segrega

tion, [4] the Boards' rejection

of alternative school district

configurations in favor of a

segregation-maximizing alterna

tive, and [5] the State Board's

blatantly improper interpretation

of its own "race regulation" to

endorse the very evil the regula

tion was designed to prevent.

672 F.2d at 1118 (footnote omitted).

Petitioners seek to avoid both

the district court's application of Keyes

and its well-supported findings of segrega

tive intent. Their arguments mischaracterize

both the holdings of this Court and the find

ings of the district court. Churchill, for

example, argues that there simply was no vi

olation, that the district court merely at

tempted to correct a condition which

34

Churchill perceives as de facto racial im

balance, a condition it asserts was not

brought about by the actions of the school

authorities. Churchill Petition at 17.

While General Braddock concedes that the

district court would not have been permit

ted to impose such a remedy for the sole

purpose of redressing a de facto racial im

balance, as has been demonstrated, there is

ample support in the record to support the

district court's findings of purposeful and

intentional de jure segregation, as the

court of appeals determined. See

generally, Hoots IX, 672 F.2d at 1115-1118.

In a similar vein, Edgewood

School District, Turtle Creek Area School

District, and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania

seriously misstate both the findings of the

district court and its application of this

Court's standards regarding the use of

35

foreseeable consequences as some proof from

which the court may infer segregative in

tent. Contrary to Edgewood's and Turtle

Creek's assertions, the district court's de

cision was not based solely upon a finding

that the State and County Boards' failure

to take proper account of the foreseea

bility of the discriminatory impact of

their actions and policies was sufficient

to constitute de jure segregation.

Edgewood-Turtle Creek Petition at 19; Com

monwealth Petition at i. Indeed, as has

been set out, supra, the Third Circuit iden

tified this factor as only one of the dis

trict court's many major factual conclu

sions, see, 672 F.2d at 1115-1116, in addi

tion to its review of nine examples of

direct and circumstantial evidence relied

upon to find a violation. S e e , id. at

1117-1119.

36

Petitioner Swissvale, for its

part, suggests that this Court's decision

in Arlington Heights precludes a finding of

a constitutional violation unless the dis

trict court determines that the action or

conduct complained of "would not have been

taken but for the racial motive." Swissvale

Petition at 13. Swissvale relies on foot

note 21 of that decision and Mt. Healthy

City Board of Education v. Doyle, 429 U.S.

274 (1977), cited therein. Neither of

these authorities is support for the appli

cation of such a standard in this case. In

Mt. Healthy this Court did no more than

hold that where constitutionally protected

conduct is found to be a motivating factor

in the state's decision, the burden of proof

shifts to the decisionmaker — here the

school authorities — to demonstrate that

the same decision would have been reached

37

even absent this constitutional aspect.

Similarly, in footnote 21 in Ar1 ington

Heights, the Court indicated that the estab

lishment that governmental action was moti

vated in part by a racially discriminatory

purpose shifts to the government entity the

"burden of establishing that the same deci

sion would have resulted even had the imper

missible purpose not been considered." 429

U.S. 270-71 n.21. Petitioners have failed

to meet their burden of disproving causation.

As early as 1973, the district court held

that once segregative intent is demonstrated,

"the school authorities bear the burden of

showing that [their] policies are based on

educationally required, non-racial considera

tions." 359 F. Supp. at 823, conclusion of

law 4. The district court correctly placed

this burden on the school authorities —

petitioners -- and found that they completely

38

failed to carry their burden of proof: "The

Record contains absolutely no evidence showing

that the school district boundaries established

in the County and State Boards' Plan of organiza

tion of administrative units are rationally

related to any legitimate purpose and this

Court finds that such boundaries do not pro

mote any valid state interest." I_d. at 821.

Here, proof of segregative intent permeates

each step of the reorganization process, and

such proof is dispositive where, as here,

there was an absence of any rebuttal evidence.

39

II. HAVING FOUND A CONSTITUTIONAL VIOLATION,

THE DISTRICT COURT APPLIED THE APPRO

PRIATE STANDARDS ESTABLISHED BY THIS

COURT IN FASHIONING AN INTERDISTRICT

REMEDY INVOLVING ONLY THOSE DISTRICTS

FOUND TO HAVE BEEN INVOLVED IN OR

AFFECTED BY THE VIOLATION

The applicable standard for apply

ing multidistrict remedies in school desegre

gation cases is clearly set forth for redis

tricting cases in Milliken v . Bradley, 418

U.S. 717 (1974) (Milliken I ) . Milliken I

built upon the basic equitable principle

enunciated in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971), that

"the scope of the remedy is determined by the

nature and extent of the constitutional vio

lation." Thus, after citing Swann, Milliken I

held:

Before the boundaries of separate

and autonomous school districts

may be set aside by consolidating

the separate units for remedial

purposes or by imposing a cross

district remedy, it must first be

shown that there has been a consti-

40

tutional violation within one

district that produces a significant

segregative effect in another dis

trict. Specifically, it must

be shown that racially discrimi

natory acts of the state or local

school districts, or of a single

school district have been a sub

stantial cause of interdistrict

segregation. Thus an interdistrict

remedy might be in order where the

racially discriminatory acts of

one or more school districts caused

racial segregation in an adjacent

district, or where the district

TTnes~lTavi~~^e¥n~~delTbe7iTe3ry

drawn on the basis of race. In

such circumstances an interdis

trict remedy would be appropriate

to eliminate the interdistrict

segregation directly caused by

the constitutional violation.

Conversely, without an interdis

trict violation and interdistrict

effect, there is no constitutional

wrong calling for an interdistrict

remedy.

418 U.S. at 744-745 (emphasis added).

The district court properly found

that an interdistrict remedy can be imposed

against all those school districts whose

"boundaries were drawn or redrawn during

the course of the same violation which created

41

510 F.the segregated school districts."

Supp. at 619. The district court correct

ly interpreted Milliken I as holding that

an interdistrict remedy may be imposed

where the condition of segregation in one

district can be shown to result either from

the segregative acts in an adjoining dis

trict or from the line-drawing process it

self. The district court properly applied

the Milliken I standard by requiring that

each district affected by its order be im

plicated or involved in the violative con

duct. Here, as both courts below have

found, this conduct was the consolidation

process itself, the line-drawing undertaken

by the State and County Boards. Where, as

here, state officials have contributed to

the separation of the races by redrawing

district lines, Milliken I recognizes the

compelling need for interdistrict relief.

42

Petitioners' argument that an

interdistrict remedy is inappropriate be

cause the surrounding districts are "inno

cent" of any wrongdoing replicates similar

arguments already rejected in numerous

post-M i H i ken appellate decisions. The

flaw in this argument was elegantly and

concisely exposed in United States v. Board

of School Commissioners, 573 F.2d 400, 410

(7th Cir.), cert, denied, sub nom., Bowen

v. United States. 439 U.S, 824 (1978):

The commands of the Fourteenth

Amendment are directed at the

state and cannot be avoided by a

fragmentation of responsibility

among various agents. Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 15-17 (1958).

If the state has contributed to

the separation of the races, it

has the obligation to remedy the

constitutional violations. That

remedy may include school dis

tricts which are its instrumental

ities and which were the product

of the violation.

See ? e.g., Morrilton v. United States, 606

F.2d 222 (8th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 444

43

U.S. 1071 (1980); United States v. State of

Missouri y 515 F.2d 1365 (8th Cir. 1975) .13

The district court, as the court

of appeals found, did not exceed the proper

limits on its remedial authority by includ

ing petitioners in its remedial district.

Contrary to the assertions of Churchill,

Edgewood and Turtle Creek, the district

court's remedial authority was not limited

to a consideration of those consolidation

plans which the State and County Boards

would have implemented. Churchill Petition

at 19; Edgewood-Turtle Creek Petition at

18. This Court early on stated that

" [o]nce a right and a violation have been

Contrary to the assertion of the

Borough of Edgewood, Amicus Curiae, at

15-19, the courts of appeals have consis

tently and properly applied Milliken with

out any conflict. Differences in result

among the cases cited by Edgewood Bo

rough are explained by the different

facts of the cases and not by their

failure properly to apply Milliken.

44

shown, the scope of a district court's equi

table powers to remedy past wrongs is

broad, for breadth and flexibility are in

herent in equitable remedies." Swann,

supra, 402 U.S. at 15 (1971). See also,

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 288 (1977)

(Milliken II) .

The statement in Milliken I that

the remedy should be broad enough to re

store the plaintiffs "to the position they

would have occupied in the absence of such

[unconstitutional] conduct", 418 U.S. at

746, has not been construed to require the

district court to second-guess what the dis

criminatory state authorities would have

done but for their wrongful intent. Rather

the remedial plan devised and adopted by a

district court must simply be broad enough

to completely eradicate the de jure discrim-

nation. See, Milliken II, supra, 433 U.S.

45

at 282; Morrilton , supra, 606 F.2d at 229-

30.

Churchill1s argument that it was

unavailable for merger with what later became

General Braddock ignores the Milliken I rule.

Churchill asserts that the district court

must determine "what the conditions would

have been but for the alleged constitu

tional violation." Churchill Petition at

19. Where, as here, there were more than

fifteen school districts affected by the

State and County Boards' redistricting

plans, and where numerous consolidation

plans were proposed in the course of the

decade-long consolidation process, it would

be both impossible and impractical to at

tempt to recreate that exact set of condi

tions which would have been "but for" the

violation. This is especially so where the

consolidation process itself is the essence

46

of the violation. Indeed, absent the con

stitutional violation, any number of consol

idation plans could or would have been ap

propriate. Although any number of other

combinations were possible, the only

question on appeal is whether the remedy

constituted an abuse of discretion. Dayton

Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406,

417-418 (1977). And, as the court of appeals

noted, rather than having abused its discretion,

the district court "very ably dealt with all

of the intricate, complex and hotly contested

issues in this case since 1971." 672 F .2d

at 1120, n.12.

Swissvale asserts that a "school

district may not be ordered out of exis

tence as part of a multidistrict desegrega

tion remedy unless there has been an affir

mative showing -— not merely an unrebutted

presumption — that the inclusion of that

47

district is necessary to eliminate the

segregative effects 'directly caused by the

constitutional violation'." Swissvale Peti

tion at 21. This suggestion has no support

in precedent. In any event, this argument

is irrelevant in the present case given

that the district court's decision as to

the propriety of the interdistrict remedy

was based on a full, factual record rather

than on bare unrebutted presumptions, as

Swissvale misleadingly suggests. This

record was compiled over the ten-year

duration of the district court proceedings

and took full account of the evidence of

fered by all parties. See generally, Hoots

V III, (884a-895a); see also (1750a-1756a;

1760a-1765a; 1800a-1804a) .

While, as Swissvale notes, the

court of appeals invoked the burden-

shifting presumption of Keyes (as applied

48

in a multidistrict context in Evans v.

Buchanan, 582 F.2d 750, 764-66 (3d Cir.

1978) (en banc) , cert. denied, 446 U.S. 923

(1980)), with respect to the propriety of

the remedy, 672 F.2d 1121, the court of ap

peals did not rely solely on this presump

tion. Moreover, a thorough review of both

remedy decisions, Hoots VI and Hoots v m , re

veals that the district court did not even

consider, let alone employ, this shift.

Thus, Swissvale's assignment of error to the

court of appeals on this point — note that

Swissvale does not attribute the alleged error

to the district court, Swissvale Petition

at 20-22 — is irrelevant, unsupported

by the district court's record and need not

be addressed by this Court.

In Hoots V I , the district court

dealt with the question of "which, if any,

of the surrounding school districts can be

49

included in any remedy within the guide

lines of" Milliken I . 510 F. Supp. at 616.

After a review of the Milliken I standard,

the district court found that "[t]his case

clearly falls within Milliken I guidelines

for an interdistrict remedy, since racially

discriminating acts of the state have been

a substantial cause of interdistrict segre

gation." id. at 619. In order to comply

with Milliken I , the district court employed

a two-step analysis. The first step was to

identify the geographical area involved in

the violation. The second step was to de

termine which of those districts involved

in the violation must be included in order

for the remedy to be meaningful. The dis

trict court, in its determination of the ge

ographic area of the violation, determined,

for example, that Steel Valley and West

Mifflin school districts were not involved.

50

Hoots VIII, (891a). In April 1981, the

district court conducted the second step of

its analysis. At that time it considered

the inclusion of the six school districts

which were found to have been involved in the

violation in addition to General Braddock.

Only four of these districts — petitioners

— were included in the remedy. The dis

trict court determined that the inclusion

of Gateway and East Allegheny was not called

for because it would not have alleviated the

segregative effect of the violation. Id.

As the court of appeals recognized, the remedy

imposed was narrower than the geographic scope

of the violation. 672 F.2d at 1120. Thus,

rather than being overbroad, as petitioners

allege, the remedy was in fact fashioned

to cause minimum disruption to existing dis

trict boundaries while simultaneously accom

plishing its necessary remedial functions.

51

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth

the Petitions for Certiorari should

above,

be denied.

Respectfully Submitted,

Linda R. Blumkin*

Leonard Benowich

FRIED, FRANK, HARRIS,

SHRIVER & JACOBSON

(A partnership which

includes professional

corporations)

One New York Plaza

New York, New York 10004

(212) 820-8000

* Counsel of Record for

Respondent General

Braddock Area

School District

Of Counsel:

Anton W. Bigman

210 Fort Pitt Common

445 Fort Pitt Boulevard

Pittsburgh, Pa. 15219

(412) 471-2644

52

M E I L E N P R E S S INC. — N. Y . C 219