Milliken v. Bradley Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

June 13, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Milliken v. Bradley Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1972. ab0406c4-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21d8fe9d-2ff6-4d7a-80f7-cc397899183c/milliken-v-bradley-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

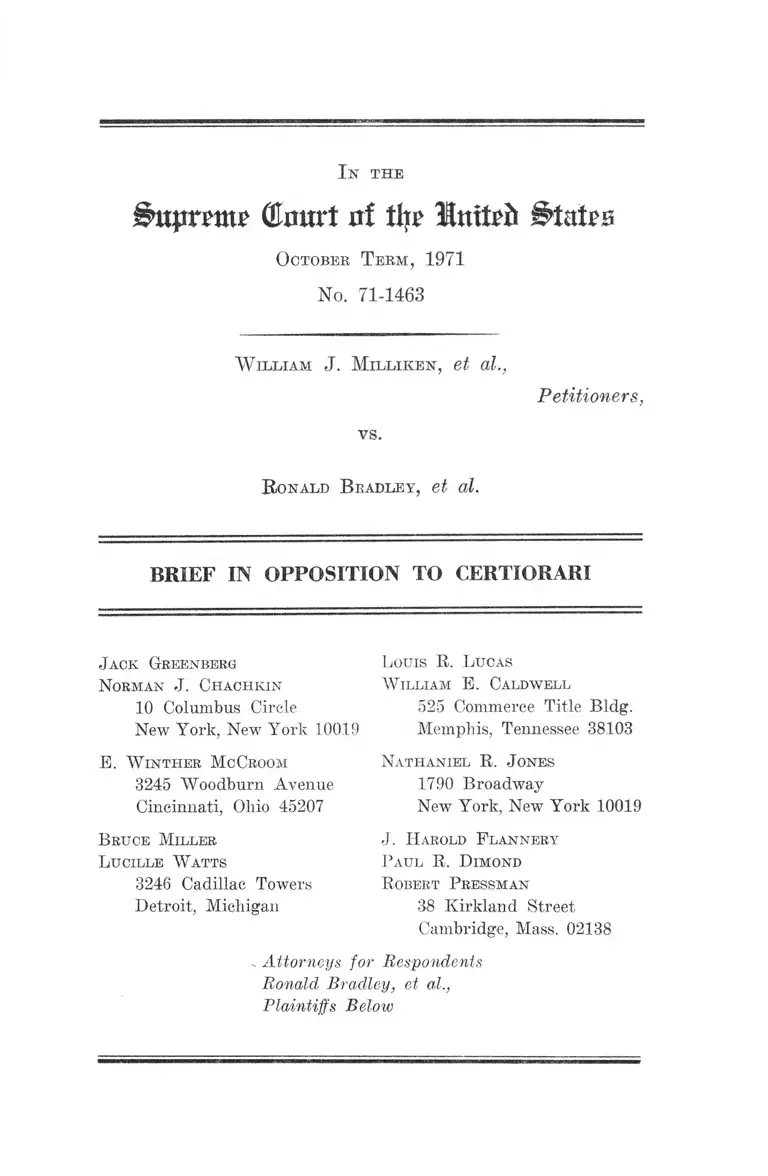

I n t h e

Ctart nf % lutein IHates

O ctobee T eem , 1971

No. 71-1463

W illiam J. M il l ik e n , et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R onald B radley, et al.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Jack Greenberg

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

B . W lN T H E R M c C r OOM

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

Bruce Miller

Lucille W atts

3246 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan

Louis R. Lucas

W illiam E. Caldwell

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Nathaniel R. J ones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J. H arold F lannery

Paul R. D imond

Robert Pressman

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

, Attorneys for Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs Below

I N D E X

Opinions Below ................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................. 1

Question Presented .................................................-......... 2

Statement ...........................................................................- 2

Tlie First Appeal Below ............................ - ........... 2

The Second Appeal - ................................................... 3

The Third Appeal........................................... 4

Subsequent Proceedings in the District Court....... 5

R easons eor D enying th e W rit—

I. Considerations of Practicality and Sound Judicial

Administration as Well as the Strong Federal

Policy Against Piecemeal Appeals Expressed in

28 U.S.C. §1291 Compel Denial of the W rit ........... 6

A. It is Highly Likely That the Question Will be

Mooted Before This Court Reaches the Merits 6

B. Piecemeal Review Is Particularly Inappropri

ate in School Desegregation Cases ................... 7

C. The Ruling Below Correctly Applies the De

cisional Law of This Court in Interpreting 28

U.S.C. §1291 as to the Jurisdiction of the Courts

of Appeals ........................................... 10

PAGE

u

II. Assuming Arguendo That the Court of Appeals

Had Jurisdiction, This Court Should Not Review

the Substantive Issues Before the Court of Ap

peals Has the Opportunity to R u le .......................... 15

Co n c l u s io n ........................................................................... 18

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Edue., 396 U.S. 19

(1969) ...............................................................................7,12

Bohms v. Gardner, 381 F.2d 283 (8th Cir. 1967)........... 11

Borough of Ford City v. United States, 345 F.2d 645

(3d Cir.), cert, denied, 382 U.S. 902 (1965)................. 11

Bradley v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897 (6th Cir. 1970)......... 3

Bradley v. Milliken, 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971)....... 13

Bradley v. Milliken, 338 F. Supp. 582 (E.H. Mich. 1971) 1

Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, 370 U.S. 294 (1962)

11,12n, 16

Calhoun v. Cook, 451 F.2d 583 (5th Cir. 1971)............... 9

Clark v. Kraftco Corp., 447 F.2d 933 (2d Cir. 1971)..... 15

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).................................. 8n

Corpus Christi Independent School Dist. v. Cisneros,

404 U.S. 1211 (1971) ..................................................... 12

Corpus Christi Independent School Dist. v. Cisneros,

Misc. No. 1746 (5th Cir., July 10, 1970)...................... 13

Firestone Tire & Rubber Co. v. General Tire & Rubber

Co., 431 F.2d 1199 (6th Cir. 1970)................................ 15n

PAGE

I ll

Franklin v. Quitman County Bd. of Educ., 443 F.2d 909

(5th Cir. 1971) ................................................... ............. 10

Gillespie v. United States Steel Corp., 370 U.S. 148

(1964) ............................................................. 13,14,14n, 15n

Griffin v. County School Bd., 377 U.S. 218 (1964)......... 8n

Joseph F. Hughes & Co. v. United Plumbing & Heat

ing Co., 390 F.2d 629 (6th Cir. 1968)........ ............ ..... 15n

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ., 436 F.2d

856 (6th Cir. 1970) ............ ......................................... . 15n

Keyes v. School Hist. No. 1, Denver, 445 F.2d 990 (10th

Cir. 1971), cert, granted, 404 U.S. 1036 (1972)........... 13

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, Denver, 313 F. Supp. 61, 90

(D. Colo. 1970) ............................................................... 13

Keyes v. School Dist. No. 1, 303 F. Supp, 279 (D. Colo.

1969) ............................................................. 13

Leonard v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co., 130 F.2d 535 (7th

Cir. 1942) ......... 11

Republic Natural Gas Co. v. Oklahoma, 334 U.S. 62

(1948) ............................................................................... 11

Russell v. Barnes Foundation, 136 F.2d 649 (3d Cir.

1943) ............ 10

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S.

1 (1971) .........................................................................lOn, 12

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 431 F.2d

138 (4th Cir. 1970), rev’d 402 U.S. 1 (1971)............... 13

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 311 F.

Supp. 265 (E.D. N.C. 1970) ......................... 13

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 300 F.

Supp. 1358 (E.D. N.C. 1969)

PAGE

13

IV

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 288 F.2d

600 (2d Cir. 1961) .............................................. 9,13,15,16

The Palmyra, 10 Wheat. (23 U.S.) 502 (1825)............... 10

United States v. Easement and Right-of-Way, 386 P.2d

769 (6th Cir. 1967) .......................................................... 15n

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 431 F.2d

1313 (5th Cir. 1970) ...................................................... 15n

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1254(1) ............................................................. 1

28 U.S.C. §1291 ................................................... 5, 6, 7,10,15

28 U.S.C. §1292(b) ....................................................... 13,14n

PAGE

Rules:

F.R.C.P. 54(b) .................................................................... 6

F.R.C.P. 56(c) .................................................................... 11

F.R.C.P. 56(d) .................................................................... 11

I n the

ghtjjmne (tart ni % Initrii States

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 71-1463

W illiam J. M il lik e n , et al.,

Petitioners,

—vs.—

R onald B radley, et al.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

Since the filing of the Petition for a. Writ of Certiorari,

the September 27, 1971 opinion of the district court, which

was the subject of the appeal dismissed below, has been

reported at 338 F. Supp. 582.

Neither the Court of Appeals’ order of dismissal nor the

ruling's of the district court issued subsequent thereto have

yet been reported; the yirior opinions of the Court of Ap

peals are reported at 433 F.2d 897 and 438 F.2d 945.

Jurisdiction

This Court has jurisdiction of this case pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1254(1).

2

Question Presented

A single question is properly presented by this case:

whether the Court of Appeals erred in dismissing 'Peti

tioners’ appeal from an interlocutory district court order

requiring them to submit a desegregation plan for the

court’s consideration in the further stages of the litiga

tion, when none of the Petitioners nor any other party was

thereby enjoined to take any acts directly affecting the

operation of the schools or the assignment of pupils and

when important issues affecting the scope and content of

any subsequent district court order remained to be resolved.

Statement

This is a school desegregation case which was commenced

August 18, 1970 against the Superintendent of Schools

and Board of Education of the City of Detroit, the Gov

ernor, Attorney General, State Board of Education and the

State Superintendent of Public Instruction of Michigan.

The present Petition for a Writ of Certiorari is filed only

by the State defendants, although a Brief in Support of

the Petition has been submitted by a group of Respondent

school districts located outside Detroit which were per

mitted to intervene as defendants in the district court.

The First Appeal Below

This litigation was filed a month and a half after the

Michigan Legislature enacted a statute, described by the

Court below in an earlier decision as “unconstitutional and

of no effect as violative of the Fourteenth Amendment,”

which “thwarted, or at least delayed,” implementation of

a reassignment plan designed to achieve greater desegrega

tion in Detroit’s high schools which had been adopted by

3

the Detroit Board of Education on April 7, 1970, Bradley

v. Milliken, 433 F.2d 897, 904 (6th Cir. 1970). The com

plaint accordingly prayed that a preliminary injunction

issue against the operation of the statute and that imple

mentation of the April 7, 1970 plan be directed.1

The complaint further alleged that the public schools

of Detroit were being operated on a racially segregated

basis as a result of historic policies, practices and actions

of State authorities. It sought appropriate permanent

relief requiring the dissolution of the segregated system

and elimination of racially identifiable schools.

The district court initially denied the motion for pre

liminary injunction, but its ruling was reversed by the

Court of Appeals, which held the statute unconstitutional.

433 F.2d 897.

The Second Appeal

On remand, the plaintiffs sought again to require the

immediate implementation of the April 7 Plan as a matter

of interim relief to remedy the mischief created by the

enactment of the unconstitutional statute, without deter

mination of the more general issues raised in the complaint.

The district court permitted the Detroit Board of Educa

tion to propose alternative plans and approved one of

them; plaintiffs again appealed, but the Court below re

manded the matter “with instructions that the case be

set forthwith and heard on its merits,” stating:

The issue in this case is not what might be a de

sirable Detroit school plan, but whether or not there

1 Following adoption of the April 7, 1970 desegregation plan, a

majority of the members of the Detroit Board of Education were

recalled by the electorate and their positions filled by subsequent

appointment by the Governor of Michigan.

4

are constitutional violations in the school system, as

presently operated, and if so, what relief is necessary

to avoid further impairment of constitutional rights.

438 F.2d 945, 946 (6th Cir. 1971) (emphasis supplied).

The Third Appeal

An extensive trial consumed most of the spring and

summer of 1971 and on September 27, 1971, the district

court issued Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law,

338 F. Supp. 582, in which it concluded that the racial

segregation in the Detroit public schools was not acci

dental but rather the product of a panoply of racially

discriminatory actions by federal, state and local author

ities, educational and other, combined with acts and results

of private discrimination. The court scheduled a pretrial

conference to discuss further proceedings with counsel,2 3

at which time the Detroit Board of Education and the

Michigan State Board of Education were orally directed

to submit proposed plans of desegregation. At the request

of the State defendants, the district court on November

5, 1971 reduced its oral instructions to the parties to a

written Order (see Appendix to Petition for Writ of

Certiorari, pp. 29a-30a). On December 3, 1971, the Detroit

2 A group of Detroit parents who had intervened in the proceed

ings had filed a motion seeking to join as parties other school dis

tricts surrounding Detroit so that the Court might fashion relief

involving the exchange of pupils in such districts and the Detroit

district. The lower court declined to pass upon this motion in its

September 27 ruling but did later direct the State Board of Edu

cation to submit a metropolitan plan of desegregation for the

court’s consideration, as well as permit intervention by 43 school

districts outside Detroit.

5

Board of Education and the Petitioners filed Notices of

Appeal from the Order of November 5, 1971.3

On January 25, 1972, plaintiffs filed a Motion to Dismiss

Appeals (which had been docketed in the Sixth Circuit

on January 24) on the ground that the Court of Appeals

lacked jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1291 since the

Order of November 5, 1971 could not be construed as a

final order. After response by all parties, the Court of

Appeals entered the order of which review is sought on

February 22, 1972.

Subsequent Proceedings in the District Court

Following issuance of its Order of November 5, 1971

and since dismissal of Petitioners’ appeal, the district

court has pursued further proceedings in this matter look

ing toward the shaping of an appropriate remedial decree

for the constitutional violations it found to exist. The

court has considered desegregation plans limited to the

City of Detroit and not so limited; it has permitted inter

vention in the proceedings by a large number of school

districts outside the City of Detroit; it has held exhaustive

hearings this spring; it has received extensive proposed

findings of fact and conclusions of law on the remedy issue;

and it has issued various interlocutory rulings and opinions

of law (see Appendix to Petition, pp. 31a-43a) but no order,

injunction or judgment. The matter is now awaiting the

court’s decision and the formulation of an equitable

decree—a final order in this litigation.

3 On December 11, 1971, plaintiffs below filed a Notice of Appeal

from the November 5 Order of the district court limited to the

correctness of the district court’s findings in the September 27,

1971 opinion on the subject of faculty segregation. In the Motion

to Dismiss the Detroit Board’s and Petitioners’ appeals filed in the

Court below, plaintiffs questioned the viability of their own appeal

and consented to its dismissal as well if their motion -were granted.

6

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

I.

Considerations of Practicality and Sound Judicial

Administration as Well as the Strong Federal Policy

Against Piecemeal Appeals Expressed in 28 U.S.C. §1291

Compel Denial of the Writ.

A. It is Highly Likely That the Question W ill Be Mooted

Before This Court Reaches the Merits.

Petitioners sought to appeal from an interlocutory order

of the district court which required nothing more than

that they prepare and submit to the court a plan of desegre

gation—an order so clearly considered by the district judge

to be one concerned only with the manner of proceeding-

in the litigation that it was not reduced to writing except

upon the request of counsel for Petitioners. Compare

F.R.C.P. 54(b) (express direction for entry of judgment

is predicate of appealability). Petitioners’ appeals were

dismissed by the Court below on February 22, 1972; the

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari was docketed here May 9,

1972, seeking reversal of the Sixth Circuit’s order dis

missing the appeals because the district court decree was

not final. Thus, should Petitioners prevail in this Court,

the Court of Appeals’ Order of Dismissal will be vacated

and the matter restored to its docket for submission of

briefs by the parties and oral argument.

Such a course of action is clearly unnecessary to protect

Petitioners’ right to review, and, indeed, events are likely

to overtake this Court’s process so as to require the dis

missal of the Writ, if granted. For during the course of

the proceedings in the Court of Appeals and here, the

litigation of this matter before the district court has con-

7

tinned. A set of hearings nearly as lengthy as those of the

summer of 1971, which resulted in the district court’s Memo

randum Opinion finding unlawful segregation in the public

schools, was held this spring on the issue of the appropriate

remedy for such segregation and the entire matter is now

under advisement before the district court, which has indi

cated that it would attempt to render its decision prior to

the 1972-73 school year.

Thus, even if this Court were to grant the Petition, there

is substantial likelihood that the district judge will shortly

have entered a final order into which its prior rulings

would be merged and from which Petitioners could, if

dissatisfied, prosecute an appeal to the Sixth Circuit and

litigate all of the issues they now seek to litigate in this

Court.

In the circumstances of this case, therefore, favorable

consideration of the Petition by this Court is unlikely

to afford Petitioners any greater protection of their rights

than denial.

B. Piecemeal Review Is Particularly Inappropriate

in School Desegregation Cases.

The usual policy against piecemeal review (given ex

pression in 28 U.S.C. §1291) is particularly suited and

essential in school desegregation cases. Not only are the

issues of violation and remedy interrelated, but the im

mediacy requirements of Alexander v. Holmes County

Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969) weigh heavily against

encouraging delay by fragmented appeals. Against the

generalized claim advanced by Petitioners that the public

interest would be served by a determination on the matter

8

of liability4 (Petition, at p. 12) must be placed the interest

of black schoolchildren who are discriminated against and

the public interest in the constitutional operation of the

schools.

The considerations peculiar to school desegregation cases

were enunciated by Chief Judge Friendly of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in 1961;

his words bear quotation here:

There is a natural reluctance to dismiss an appeal in

a case involving issues so important and evocative of

emotion as this, since such action is likely to be re

garded as technical or procrastinating. Although we

do not regard the policy question as to the timing of

appellate review to be fairly open, we think more

informed consideration would show that the balance

of advantage lies in withholding such review until the

proceedings in the District Court are completed. To

stay the hearing in regard to the remedy, as appellants

seek, would produce a delay that would be unfortunate

unless we should find complete absence of basis for

any relief—the only issue that would now be open

to us no matter how many others might be presented,

since we do not know what the District Judge will

order—and if we should so decide, that would hardly

be the end of the matter. On the other hand, to permit

4 This is an intriguing argument: the district court here initially

denied relief sought by the plaintiffs on two occasions without simi

lar public outcry and was only persuaded after an extensive trial.

Yet, whipped by emotional appeals of office-seekers, the public is

said to be so aroused that compliance with the Judicial Code is

characterized as “ profoundly inimical to the public interest.” The

history of school desegregation teaches that even the most carefully

considered rulings of this Court do not escape the same reaction

and manipulation. See Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 13; Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ; Griffin v. County School Bd., ?77 U.S

2?8 (1964).

9

a hearing on relief to go forward in the District Court

at the very time we are entertaining an appeal, with

the likelihood, if not indeed the certainty, of a second

appeal when a final decree is entered by the District

Court, would not be conducive to the informed appel

late deliberation and the conclusion of this controversy

with speed consistent with order, which the Supreme

Court has directed and ought to be the objective of all

concerned. In contrast, prompt dismissal of the appeal

as premature should permit an early conclusion of the

proceedings in the District Court and result in a decree

from which defendants have a clear right of appeal,

and as to which they may seek a stay pending appeal

if so advised. We—and the Supreme Court, if the

case should go there—can then consider the decision

of the District Court, not in pieces but as a whole, not

as an abstract declaration inviting the contest of one

theory against another, but in the concrete. We state

all this, not primarily as the reason for our decision

not to hear an appeal at this stage, but rather to

demonstrate what we consider the wisdom embodied

in the statutes limiting our jurisdiction, which we

would be bound to apply whether we considered them

wise or not.

Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 288 F.2d 600,

605-06 (2d Cir. 1961). See also, Calhoun v. Cook, 451 F.2d

583 (5th Cir. 1971) (retaining jurisdiction of appeal and

remanding to permit plaintiffs to put on evidence as to

feasible plan of desegregation).

Finally, we are confident that we need not emphasize to

this Court the considerations of judicial economy which

support the decision below. These are particularly appro

priate in school desegregation cases, which necessarily ai'e

10

given some priority of treatment {see, e.g., Franklin v.

Quitman County Board of Education, 443 F.2d 909 n. 1 (5th

Cir. 1971)) and which already result in significant litigation

in the Court of Appeals.5

C. The Ruling Below Correctly Applies the Decisional

Law o f This Court in Interpreting 28 U.S.C. §1291

as to the Jurisdiction o f the Courts o f Appeals.

We have made the point above that this is not a particu

larly compelling case for the exercise of this Court’s

certiorari jurisdiction since a decision by this Court is

likely to have little practical impact and since piecemeal

review is especially unsuited to school desegregation cases.

We argue in this section that Petitioners’ legal arguments

are likewise unconvincing; rather, the Court below reached

a correct result after weighing the factors delineated by the

decisions of this Court affecting the issue of finality, and

the two cases cited by Petitioners fail to support their

contentions.

We begin with the fact that the Order of November 5,

1971 required only that the Michigan State Board of Edu

cation and the Board of Education of the City of Detroit

submit desegregation plans for the further consideration

of the district court. No injunction was entered at that time

affecting the daily operation of the schools or the assignment

of pupils. Thus, the order was akin to a grant of partial

judgment on the issue of liability alone, which is not appeal-

able. E.g., The Palmyra, 10 Wheat. (23 U.S.) 502 (1825)

(Marshall, C.J.); Russell v. Barnes Foundation, 136 F.2d

5 In Swann, supra, this Court noted that the Fifth Circuit had

considered 160 appeals in school desegregation cases in less than

one preceding year. 402 IJ.S. at 14. In 1971, the Sixth Circuit

considered and decided cases from Detroit, Kalamazoo, and Pontiac,

Michigan; Nashville, Knoxville, Memphis, Jackson, Shelby County

and Madison County, Tennessee, involving school desegregation.

11

649 (3d Cir. 1943); Borough of Ford City v. United States,

345 F.2d 645, 647 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 382 U.S. 902

(1965); Leonard v. Socony-Vacuum Oil Co., 130 F.2d 535

(7th Cir. 1942); see cases cited by Mr. Justice Frankfurter

in Republic Natural Gas Co. v. Oklahoma, 334 U.S. 62, 68

(1948). And see F.R.C.P. 56(c) (interlocutory summary

judgment on liability); F.R.C.P. 56(d) (partial summary

judgment).

The general principles affecting the determination of

finality were cogently summarized by Mr. Justice Blackmun

in Bohms v. Gardner, 381 F.2d 283, 285 (8th Cir. 1967),

wherein the Eighth Circuit dismissed an appeal from an

order remanding a social security benefit determination to

the Secretary of HEW because the lower court’s order

. . . neither granted nor denied the relief the claimant

seeks .. . Thus, in the words of Catlin v. United States,

supra, [324 U.S. 229 (1945)] the litigation had not

reached its end on the merits and there is more for the

court to do than execute the judgment, or, as Judge

Ridge said, in Smith v. Sherman, supra, p. 551 of 349

F.2d, the district court’s action by no means was “the

last word of the law.”

The instant case is not at all akin to Brown Shoe Co. v.

United States, 370 U.S. 294 (1962), cited by Petitioners.

In that decision, Mr. Chief Justice Warren writing for

the Court held that a direct appeal under the Expediting

Act (15 U.S.C. §29) was properly taken from an order

granting relief in an antitrust case including divestiture,

even though the details of a plan to accomplish this di

vestiture remained to be devised and submitted to the

district court for approval. The Court relied upon three

factors: (1) the order disposed of the entire case, includ

ing every prayed for relief—while ultimate divestiture was

12

ordered, several specific injunctions were also issued (370

U.S. at 308); (2) delay in reviewing the matter could

result in harm to the parties and the public interest be

cause market conditions might change during the pendency

of an appeal in such a fashion as to prevent an already

formulated and approved plan of divestiture from being-

functional (370 U.S. at 309); and (3) the practice in the

past, although not controlling, had been to accept such

appeals, usually without discussion of finality (ibid.).6

Each of these factors, considered in the present case,

militates against treating the district court’s decree of

November 5, 1971 as a final order. In the first place, every

claim for relief was not passed upon. And far more re

mained to be done than just the formulation of a plan to

effectuate a complex commercial transaction; indeed, seri

ous substantive legal issues concerning the nature and

scope of the available remedy remained to be passed upon.

See Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971). Second, there is no danger of irreparable

injury to any party by delay of the appeal; the dismissal

of the appeals below hardly forecloses the issue whether

the “ Court of Appeals, and ultimately this Court should

review this matter before hundreds of thousands of school

children are loaded onto school buses [etc.]” (Petition,

p. 11). See Corpus Christi Independent School Dist. v.

Cisneros, 404 U.S. 1211 (1971) (Mr. Justice Black); comr

pare Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., supra.7

6 So far as counsel for these Respondents are aware, this Court

has never cited Brown Shoe to justify its acceptance of an appeal

from an interlocutory decree in any but antitrust eases.

7 We here express no view on the propriety of staying whatever

remedial order may be entered by the district court, but merely

point out that Petitioners will have an adequate opportunity to

litigate that question when such an order is in fact entered. Since

the order has not yet been entered, the effective date of any relief

is as yet unknown.

13

Finally, the settled course of practice (and with good

reason, see §B, supra) in school desegregation cases has

been for appellate courts to consider rulings on the ques

tions of liability and appropriate remedy together.8 Taylor

v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle, 288 F,2d 600 (2d Cir.

1961) ; Corpus Christi Independent School Dist. v. Cisneros,

Misc. No. 1746 (5th Cir., July 10, 1970) (refusing inter

locutory appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1292 ( b ) ) ; Bradley

v. MilliJcen, 438 F.2d 945 (6th Cir. 1971). Most litigants

have followed this practice; for example, appeals chal

lenging the findings of liability in Swann, v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 300 F. Supp. 1358 (E.D.N.C.

1969) and Keyes v. School Dist, No. 1, Denver, 303 F. Supp.

279 (D. Colo. 1969), 313 F. Supp. 61 (I). Colo. 1970) were

not filed until after remedial decrees had been formulated,

see Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 311

F. Supp. 265 (E.D.N.C. 1970); Keyes v. School District

No. 1, Denver, 313 F. Supp. 90 (D. Colo. 1970). Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 431 F.2d 138 (4th

Cir. 1970), rev’d 402 U.S. 1 (1971); Keyes v. School Dist.

No. 1, Denver, 445 F.2d 990 (10th Cir. 1971), cert, gra/nted,

404 U.S. 1036 (1972).

We recognize with Petitioners that a final order “ ‘does

not necessarily mean the last order possible to be made in

a case,’ Gillespie v. United States Steel Corp., 379 U.S. 148,

at 152 (1964).” (Petition at p. 12). Indeed, the law of

finality was infused with a necessary flexibility by the de

8 While Petitioners represent that double appeals will not require

“ repetitive judicial consideration of the same question,” (Petition

at p. 11), since the constitutional violation and the remedy are

interdependent, see Swann v. Charlotte-Macklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. at 16, the Court of Appeals would of necessity be review

ing the same evidence in passing upon the appropriateness of a.

remedial decree as it had considered in passing upon the correctness

of the liability ruling.

14

cision in Gillespie.9 It does not, however, support Peti

tioners’ claims in this case.

Petitioners fail to observe that the holding in Gillespie,

which affirmed a determination by the court below in

another case to accept, rather than dismiss, an appeal on

its merits, does not remove the requirement of finality.

As the Second Circuit has put it:

. . . All that the Court decided in Gillespie was that a

court of appeals has the power to review an order in

a “marginal” case within the “twilight zone of finality”

where the questions presented on appeal are funda

mental to the further conduct of the case” and “the

inconvenience and costs of piecemeal review” are out

weighed by “the danger of denying justice by delay.”

379 U.S. at 152-154, 85 S.Ct. at 311-312. Difficult ques

tions of appealability may require a court of appeals

to review the entire record in detail. Gillespie recog

nizes the judicial inefficiency inherent in reviewing an

entire appeal and then deciding that the court of

appeals cannot act because it does not have jurisdic

tion. See Green v. W olf Corp., 406 F.2d 291, 302 (2d

Cir. 1968), cert, denied, 395 U.S. 977, 89 S.Ct. 2131,

23 L.Ed.2d 766 (1969); 9 J. Moore, Federal Practice

M110.12 (2d ed. 1970). However, the power recog

nized in Gillespie should be used sparingly, and we do

not believe that this is a proper case for its exercise.

9 Gillespie effectively allows the Court o f Appeals to relieve a

party from the consequences of failing to seek or obtain a certifi

cate pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1292(b) authorizing interlocutory

appeal, where irreparable harm would otherwise result.

15

Clark v. Kraftco Corf., 447 F.2d 933, 935-36 (2d Cir.

1971).10

We think, then, that the Court of Appeals was right in

dismissing the appeal below because even if the lack of

finality of the November 5, 1971 decree is considered open

to question, there is no realistic danger of denying justice

by delay which would compel review under Gillespie.

II.

Assuming Arguendo That the Court of Appeals Had

Jurisdiction, This Court Should Not Review the Sub

stantive Issues Before the Court of Appeals Has the

Opportunity to Rule.

If the court below was correct in dismissing Petitioners’

appeals because the November 5, 1971 order of the District-

court was not final within the meaning of 28 IT.S.C. §1291,

that is the end of the matter. Even if this Court should

accept Petitioners’ contentions as to appealability, however,

the matter should he remanded for consideration on the

merits by the Court of Appeals and the grant of certiorari

limited to the first question presented in the Petition.

Inasmuch as the Court of Appeals has not considered

the second or third questions in the Petition, it has entered

10 A brief review of other decisions of the Sixth Circuit dealing

with this issue will demonstrate convincingly that the Court prop

erly applies the pragmatic tests endorsed in Gillespie. See United

States v. Easement and Right-of-Way, 386 F.2d 769, 770 (6th Cir.

1967); Joseph F. Hughes & Co. v. United Plumbing & Heating,

Inc., 390 F.2d 629, 630 (6th Cir. 1968) ; Firestone Tire & Rubber

Co. v. General Tire & Rubber Co., 431 F.2d 1199, 1200 (6th Cir.

1970) ; Kelley v. Metropolitan County ̂ Bd. of Educ., 436 F.2d 856,

862, (6th Cir. 1970) (citing Gillespie, and holding appealable a

stay order which halted proceedings to devise a remedy for uncon

stitutional school segregation). Accord, United States v. Texas

Education Agency, 431 F.2d 1313 (5th Cir. 1970).

16

no judgment thereon and this Court could review the issues

only directly from the district court, see Rule 20 of the

Supreme Court Rules.

Petitioners do not discuss the reasons which might

justify such an exceptional exercise of this Court’s

certiorari jurisdiction; both logic and precedent argue

against review of these questions at this time.

The same practical considerations outlined by Judge

Friendly in Taylor v. Board of Educ. of New Rochelle,

supra (see pp. 8-9 above) apply with added force to the

determination whether to utilize an extraordinary procedure

which “deprives . . . this Court of the benefit of considera

tion by a Court of Appeals.” Brown Shoe Co. v. United

States, supra, 370 U.S. at 355 (Mr. Justice Clark, con

curring). The vital role which the Court of Appeals could

play in resolving factual disputes and narrowing the issues

is apparent from the nature of this case and of the

primarily factual questions presented in the Petition.

Underlining these points is the fact that the 1971 trial on

the constitutional violation in this case was the longest

such hearing in a school desegregation case insofar as these

Respondents are aware;11 the finding of unlawful segrega

tion made by the district court resulted from the analysis

and sifting of an extraordinary record, and review of its

conclusion will require an equally burdensome and time-

consuming investigation by an appellate court. But this

Court sits primarily to correct legal, not factual errors.

Petitioners assert that if the writ issues “they can

demonstrate through thorough analysis of the testimony

and exhibits, that the findings of fact made below—insofar

as they seem to support a finding of de jure segregation—

11 The trial lasted 41 days, produced 4,710 pages of transcript

and 408 trial exhibits.

17

are clearly erroneous, F.R.C.P. 52(a).” (Petition, pp. 12-13)

(emphasis supplied). Passing upon such claims is the

archetypal function of the Courts of Appeals.12

At most, the district court’s opinion of September 27,

1971—the basis of its November 5, 1971 order—determines

only the accountability of state and local educational

authorities for constitutional violations. It prescribes no

remedy and requires no metropolitan desegregation to be

effectuated. As to the issue of metropolitan desegregation,

the district court’s rulings of March 24 and March 28, 1972

(Appendix to Petition, pp. 31a-43a) are expressions of

opinion, but no orders or judgments have been entered.

All of the considerations discussed above apply with added

force to the desirability of denying review of the third

question. While there may be occasions when the impor

tance of an issue merits dispensing with intermediate ap

pellate review (see cases cited in Rule 20 of the Supreme

Court Rules), it is hardly conceivable that this Court can

render anything but advisory pronouncements if it is to

bypass the district court as well, as Petitioners and other

Respondents suggest.

12 This case bears little resemblance to those cited by the other

Respondents in which review prior to judgment in the Court of

Appeals was granted; each of those involved a substantial legal

issue plainly presented, usually of major importance to the con

tinued operation of a federal statute or other national program,

in a context shorn of significant factual dispute.

18

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the foregoing reasons, these Respondents

respectfully pray that the Petition for a Writ of Certiorari

be denied.

Jack Greenberg

Norman J. Chachkin

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

E. W inther Me Groom

3245 Woodburn Avenue

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

Bruce Miller

Lucille W atts

3246 Cadillac Towers

Detroit, Michigan

Louis R. Lucas

W illiam E. Caldwell

525 Commerce Title Bldg.

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Nathaniel R. Jones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

J. H arold Flannery

Paul R. D imond

Robert Pressman

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Mass. 02138

Attorneys for Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al.,

Plaintiffs Below

19

Certificate of Service

I n the

S upreme C ourt op th e U nited S tates

O ctober T erm , 1971

No. 71-1463

W illiam J. M illik e n , et al.,

-vs.—

Petitioners,

R onald B radley, et al.

This is to certify that a copy of the foregoing Brief in

Opposition to Certiorari was this 13th day of June, 1972,

served upon counsel of record by United States Mail,

postage pre-paid, addressed as follows:

D ouglas H. W est, Esq.

Robert B. W ebster, E sq.

3700' Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

W illiam M. Saxton, E sq.

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Robert J. Lord, Esq.

8388 Dixie Highway

Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

Eugene Krasicky, Esq..

Assistant Attorney General

Seven Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Theodore Sachs, Esq.

1000 Farmer

Detroit, Michigan 48226

A lexander B. R itchie, Esq.

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Richard P. Condit, Esq.

Long Lake Building

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Kenneth B. M cConnell, Esq.

74 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

George T. Roumell, Jr., E sq.

720 Ford Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Norman J. Chachkin

Attorney for Respondents

Ronald Bradley, et al., Plaintiffs Below

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 219