Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. Little Rock Board of Education Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1971. e71fc692-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21e70841-0663-440f-a9ef-bff933cbac9f/clark-v-little-rock-board-of-education-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

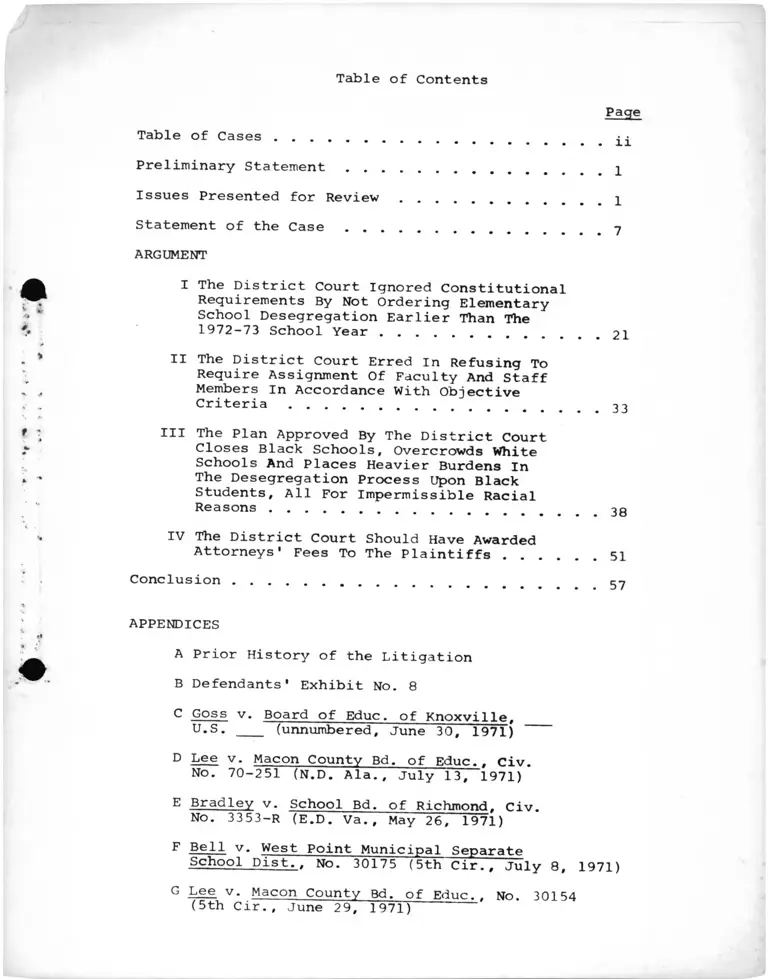

Table of Cases

Table of Contents

Page

. ii

Preliminary Statement ....................

Issues Presented for Review ............

Statement of the Case ....................

ARGUMENT

I The District Court Ignored Constitutional

Requirements By Not Ordering Elementary

School Desegregation Earlier Than The 1972-73 School Year ......................

II The District Court Erred in Refusing To

Require Assignment Of Faculty And Staff

Members In Accordance With Objective Criteria ........................

Ill The Plan Approved By The District Court

Closes Black Schools, Overcrowds White

Schools And Places Heavier Burdens In

The Desegregation Process Upon Black

Students, All For Impermissible Racial Reasons ......................

IV The District Court Should Have Awarded

Attorneys’ Fees To The Plaintiffs ..........

Conclusion ..........

1

1

7

21

33

38

51

57

APPENDICES

A Prior History of the Litigation

B Defendants' Exhibit No. 8

C Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville,

U.S. (unnumbered. June 30f 1971)

D Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ.. Civ.

No. 70-251 (N.D. Ala., July 13, 1971)

E Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond. Civ.

No. 3353-R (E.D. Va., May 26, 1971)

F Be3-1 v. West Point Municipal Separate

School Dist., No. 30175 (5th Cir., July 8, 1971)

G Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ.. No. 30154 (5th Cir., June 29, 1971)

Table of Cases

Page

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D.Ark. 1956) .......................... . 21, 56

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957) . . 21

Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220 (E.D.

Ark. 1957), aff'd sub nom. Faubus

v. United States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Cir.), aff'd sub nom. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ........................ . 21

Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13 (E.D. Ark.),

cert, denied, 357 U.S. 566, rev'd 257

F.2d 33 (8th Cir.), aff'd 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ...................... . 21

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958) . 22

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D.

Ark.), aff'd sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959) ................ . 22

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913 (E.D. Ark.

1960), rev'd sub nom. Norwood v. Tucker,

287 F.2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) .......... . 22

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ.,

396 U.S. 19 (1969) ................ . 23, 25, 27,

30, 31

Arkansas Educ. Ass'n v. Board of Educ. of

Portland, No. 20,412 (8th Cir., July 26, 1971) ........................ . 36

Bell v. West Point Municipal Separate School

Dist., No. 30175 (5th Cir., July 8, 1971) . 46

Board of Educ. of Little Rock v. Clark, 401 U.S. 971 (1971) .................. . 10, 34, 53

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 456 (E.D. Va. 1971) .............. . 49

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, Civ. No.

3353-R (E.D. Va., May 26, 1971) ........ . 54, 55

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) . . 21

Brown v. County School Bd. of Frederick

County, 327 F.2d 655 (4th Cir. 1964) . . . . 56

11

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

Byrd v. Board of Directors of Little Rock

school Dist.f Civ. No. LR-65-C-142 (E DArk. 1965).......................... * 22

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396

U.S. 226 (1969), 396 U.S. 290 (1970)........ 25

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ.

364 F. 2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966)........*! . . 34

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709

(E-D. La. 1970), aff'd 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971) ..............

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F 2d 661 (8th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ..........[ / #

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 426 F.2d

1035 (8th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, u S___ (1971)....................... — *

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, Civ.

No. LR-64-C-155 (E.D. Ark., August 17, 1970)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 316 FSupp. 1209 (E.D. Ark. 1 9 7 0 ) ..........*.

54

51

7, 8, 23, 51

23

24

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, No.

20485 (8th Cir., Feb. 2, 1971)(dissenting opinion) ..................

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, No.

20485 (8th Cir., May 4, 1971) . 24

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, Civ. No.

LR-64-C-155 (E.D. Ark., July 16, 1971) .

Dyer v.

Gordon v

No.

Love, 307 F. Supp. 974 (N.D. Miss.

. Jefferson Davis Parish School Bd.

30075 (5th Cir., June 28, 1971)

1968)

. 24, 33

. 56

. 46

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, U.S.

___ (unnumbered, June 30, 1971) "T~.

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent Countv 391 U.S. 430 ( 1968)................ /

Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke, Civ. No. 1093

(W.D. Va., August 11, 1970), aff'd sub nom.

Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, No. 14,695

(4th Cir., June 10, 1971) . \

27-28, 31

56

44

i l l

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970) ........

Jackson v. Wheatley School Dist., 430 F 2d 1359 (8th Cir. 1970) . . .

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ. of

Nashville, 436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970) . 27

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ. of

Nashville, Civ. No. 2094 (M.D. Tenn., June 28, 1971) ........

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir 1971) .......... . 54

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., Civ. No.

70-251 (N.D. Ala., July 13, 1971)

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 30154 (5th Cir., June 29, 1971)

Lee v. Southern Horne Sites, Inc., 429 F 2d 290 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . . 54

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga, Civ. No. 3564 (E.D. Tenn., July 26, 1971) . 32

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, 426 F 2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . 54

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968) . . . . 54

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 397 u S 232 (1970) . . . . . 23, 25

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Tel. Co.. 433 F 2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970) . 54

Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1151 (5th Cir. 1970) . . . 32

Quarles v. Oxford Municipal Separate School

Dist., civ. No. WC6962-K (N.D. Miss., January 7, 1970) (oral opinion) . . 45

IV

Table of Cases (continued)

Page

Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ., 282 F. Supp.

192 (E.D. Tenn. 1966), aff'd 391 F.2d 77(6th Cir. 1968) 37

Safferstone v. Tucker, 235 Ark. 70, 357 S.W.2d

3 (1962)....................................... 22

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F.2d770 (8th Cir. 1966) .......................... ..

Smith v. St. Tammany Parish School 3d., 302 F.Supp. 106 (E.D. La. 1969) 44

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Bd. of Educ., No.

71-2380 (5th Cir., August 2, 1971) ............ 28-29

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

U.S. ___, 28 L.Ed.2d 588 (1971) . . . .“7“. . . 10, 24, 27, 32

38, 46, 52̂ 56

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C., June 22, 1971) . . . . 46

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C., June 29, 1971) . . . . 32

United States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County423 F. 2d 1013 (5th Cir. 1970) ............ 31

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, 416 F.2d123 (8th Cir. 1969) .......................... ..

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 431F. 2d 1313 (5th Cir. 1970) .................... 32

Walton v. Nashville Special School Dist., 401 F.2d137 (8th Cir. 1968) .......................... 34

v

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

NO. 71-1415

DELORES CLARK, et al..

Appellants,

vs.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE LITTLE ROCK SCHOOL DISTRICT, et al..

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Preliminary Statement

This is an appeal from the July 16, 1971 decree

of the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Arkansas, Hon. j. Smith Henley, Chief Judge.

Issues Presented for Review

1* Did the district court commit constitutional

error in failing to order elementary school desegregation

until 1972-73?

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D. Ark. 1956)

Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361 (8th Cir. 1957)

Aaron v. Cooper, 156 F. Supp. 220

(E.D. Ark. 1957), aff'd sub nom.

Faubus v. United States, 254 F 2d (8th Cir.), aff'd sub nom.

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1(1958)

Aaron v. Cooper, 163 F. Supp. 13 (E.D.

Ark.), cert, denied, 357 U.S.

566, rev'd 257 F.2d 33 (8th Cir.). aff'd 358 U.S. 1 (1958)

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir 1958)

Aaron v. McKinley, 173 F. Supp. 944

(E.D. Ark.), aff'd sub nom.

Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197(1959)

Aaron v. Tucker, 186 F. Supp. 913

(E.D. Ark. 1960), rev'd sub

nom. Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961)

ALEXANDER v. HOLMES COUNTY BD OF EDUC 396 U.S. 19 (1969)

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 u S 294 (1955)

Byrd v. Board of Directors of Little

Rock School Dist., civ. No. LR-

65-C-142 (E.D. Ark. 1965)

CARTER v. WEST FELICIANA PARISH SCHOOL

BD., 396 U.S. 226 (1969), 396 U.S 290 (1970)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock

426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970),

cert, denied, ___ U.S. ___ (1971)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock

Civ. No. LR-64-C-155 (E.D. Ark., August 17, 1970)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock,

316 F. Supp. 1209 (E.D. Ark. 1970)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock

No. 20485 (8th Cir., May 4, 1971)#

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock

Civ. No. LR-64-C-155 (E.D. Ark July 16, 1971)

-2-

GOSS v. BOARD OF EDUC. OF KNOXVILLE,U.s. ___ (unnumbered, June 30,’1971)

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of

Educ. of Nashville, 436 F.2d 856 (6th Cir. 1970)

Mapp v. Board of Educ. of Chattanooga,

Civ. No. 3564 (E.D. Tenn., July 26, 1971)

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis 397 U.S. 232 (1970)

Pate v. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1151 (5th Cir. 1970)

Safferstone v. Tucker, 235 Ark. 70, 357 S.W.2d 3 (1962)

STELL v. SAVANNAH-CHATHAM BD. OF EDUC.

No. 71-2380 (5th Cir., August 2,1971)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd of

Educw __^ U.s. , 28 L.Ed. 2d588 (1971J

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of

Educ., Civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C.,June 29, 1971)

United States v. Board of Educ. of

Baldwin County, 423 F.2d 1013 (5th Cir 1970)

United States v. Texas Education Agency 431 F.2d 1313 (5th Cir. 1970)

2. Should the district court have required defen

dants to assign faculty and staff members according to

objective criteria?

ARKANSAS EDUC. ASS'N v. BOARD OF EDUC OF

PORTLAND, No. 20,412 (8th Cir., July 26, 1971) *

Board of Educ. of Little Rock v. Clark 401 U.S. 971 (1971)

-3-

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of

Educ., 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock,

No. 20485 (8th Cir., Feb. 2, 1971)

(dissenting opinion)

HANEY v. COUNTY BD. OF EDUC., 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970)

Jackson v. Wheatley School Dist., 430 F.2d 1359 (8th Cir. 1970)

LEE v. MACON COUNTY BD. OF EDUC., Civ. No.

70-251 (N.D. Ala., July 13, 1971)

Rolfe v. County Bd. of Educ., 282 F. Supp.

192 (E.D. Tenn. 1966), aff'd 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968)

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966)

UNITED STATES v. SHEET METAL WORKERS, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969)

3. Should the district court have disapproved the

school district's desegregation plan and its renewal of

construction at Henderson Junior High School because they

placed the burden of desegregation upon black students?

BELL v. WEST POINT MUNICIPAL SEPARATE SCHOOL

DIST., No. 30175 (5th Cir., July 8, 1971)

Bradley v. School Bd. of Richmond, 324 F.Supp. 456 (E.D. Va. 1971)

Gordon v. Jefferson Davis Parish School Bd.,

No. 30075 (5th Cir., June 28, 1971)

Green v. School Bd. of Roanoke, civ. No. 1093

(W.D. Va., August 11, 1970), aff'd sub

nom. Adams v. School Dist. No. 5, No.

14,694 (4th Cir., June 10, 1971)

HANEY v. COUNTY BD. OF EDUC., 429 F.2d 364 (8th Cir. 1970)

-4-

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of

Educ. of Nashville, Civ. No. 2094 (M.D. Tenn., June 28, 1971)

LEE v. MACON COUNTY BD. OF EDUC.,

No. 30154 (5th Cir., June 29,1971)

QUARLES v. OXFORD MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DIST., Civ. No. WC6962-K (N.D. Miss., January 7, 1970)(oral opinion)

Smith v. St. Tammany Parish School Bd.,

302 F. Supp. 106 (E.D. La. 1969)

4. Should the district court have awarded

attorneys' fees to plaintiffs?

Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855 (E.D Ark. 1956)

Board of Educ. of Little Rock v Clark 401 U.S. 971 (1971)

BRADLEY V . SCHOOL BD. OF RICHMOND, Civ. No. 3353-R (E.D. Va., May 26,1971) r

Brown v. County School Bd. of Frederick

County, 327 F.2d 655 (4th Cir. 1964)

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709 (E.D. La. 1970),

aff'd 437 F.2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971)

CLARK v. BOARD OF EDUC. OF LITTLE ROCK 369 F.2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock

426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970)

DYER v. LOVE, 307 F. Supp. 974 (N.D.Miss. 1968)

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., 438 F.2d 86 (4th Cir. 1971)

-5-

429Lee v. Southern Home Sites, Inc.,

F.2d 290 (5th Cir. 1970)

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, 426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir. 1970)

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968)

PARHAM v. SOUTHWESTERN BELL TEL. CO., 433 F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970)

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. ofEduc., ___ U.S. ___, 28 L. Ed. 2d588 (1971)

-6-

Statement of the Case

-̂s the second appeal from proceedings on

remand from this Court's decision in Clark v. Board of

Educ. of Little Rock. 426 F.2d 1035 (8th Cir. 1970). The

history of this litigation prior to that time is reprinted

as Appendix "A" infra for the convenience of the Court.

Further description may be found in the Brief filed by the

plaintiffs in the 1970 appeal, No. 20485, and that Brief

is, for the purpose of brevity, hereby adopted by reference.

The Little Rock School District encompasses most

of the city of Little Rock and some western portions of

Pulaski County. The pupil population projected for the

district for 1971-72 is 23,208; by race, 13,695 pupils are

white and 9,513 are black. By grade levels, 34.1% of the

pupils in the upper three grades are black, 39.2% of the

pupils in grades 8 and 9 are black; 40.5% of the pupils in

grades 6 and 7 are black; and 44.8% of the elementary pupils

are black (DX 1001, 1020-1024).

the 1970—71 school term, the district

operated five senior high schools, seven junior high schools,

?nd thirty-one elementary schools. The racial compositions

of the schools generally reflected the racial constituencies

of the neighborhoods in which they were located, and were

thus essentially the same as the 1969-70 assignment pattern

condemned by this Court in Clark, supra. The exceptions

were those instances where black pupils in grade 10 were

-7-

assigned by court decree to either Hall or Parkview schools

as part of the proposed phasing out of Mann High School.-^

The segregated character of the neighborhoods in

i'̂ -ttle Rock is the result of State, as well as private,

action. The Little Rock Housing Authority and the Little

Rock urban renewal agency, as well as the Model Cities

agency (all federal programs) have fostered segregated housing

1/ Despite this Court's opinion of May 13, 1970, Clark v.

Board of Educ. of Little Rock, supra, the Little Rock

schools' operations have remained relatively unchanged

except at the senior high school level. The most notable

and alarming change affected Horace Mann Senior High School.

In a plan submitted to the District Court on August 10, 1970,

the Board proposed the complete phasing out of Horace Mann

High in two stages by September, 1971. This plan, opposed

by the patrons and by the defendants themselves, was first

suggested by the district court (see Transcript of Proceedings, August 6, 1970, pp. 120-23).

On August 6, 1970, the Superintendent of Schools stated:

" . . . we have no plans whatsoever to propose the closing

of Mann High School, due to the fact that we fully recognize that the Mann High School community wants the Mann High

School" (Transcript of Proceedings, August 6, 1970, p. 122). The District Court then asked counsel for plaintiffs if

counsel would oppose such a closing if the Court did it.

Just three days after this colloquy, the school district did

propose the closing of Mann High School, and in justification of this abrupt and dramatic reversal, we find the same

Superintendent testifying just one week later concerning the closing of Mann, as opposed to Parkview High School:

I think there is a practical aspect to this, and that is, that we will have less diffi

culty, perhaps, in getting black students

enrolled in Hall, in Parkview, than we would

expect or experience — being totally practical

about this — than we would experience in

getting white students transported across the

city and enrolled in the Mann High School building.

(Transcript of proceedings, August 13, 1970, p. 20). Under

the plan proposed for the school year 1971-72, Mann will be

operated as an 8th and 9th grade school while Central, Hall

and Parkview will serve the 10th, 11th and 12th grades. Dur

ing the school year 1970-71, Mann housed the 11th and 12th grades only.

-8-

conditions. Clifton Giles, the Director of the Little Rock

Housing Authority and urban renewal agency, testified that

public housing projects in Little Rock were created on a

racially identifiable basis (Tr. 5 1 6 - 2 0 ) , and were located

near schools. Urban renewal relocated blacks from the

midtown West Rock area to east side black areas and rede

veloped West Rock into a white area consistent with its

surrounding neighborhoods (Tr. 515-20). The Housing Auth

ority has no present plans to locate any projects west of

University Avenue (Tr. 531). There exists no policy of

promoting integrated housing patterns by any of these

agencies (Tr. 543-44).

Nathaniel Hill, Director of the Model Cities

program, testified that the Model Cities area in eastern

Little Rock is 85% black and that there are no plans to

increase the white residency (Tr. 546). He does not expect

the racial constituency to change at all in the foreseeable

future (Tr. 548) except to become increasingly black (Tr.

549) .

During the school year 1970-71, the school

district entered into a program of construction to enlarge

the white Henderson Junior High School located in western

Little Rock. Injunctive relief against the construction

was sought pending decision by this Court of the appeal in

^ Cit?oi?nS in the foritl "Tr* ___" are to the Transcriptof 1971 proceedings, copies of which have previously been furnished to the Court.

-9-

this case then under submission, but was denied by the

district court (Order of December 18, 1970). Relief was

unanimously granted by this Court but, by an equally divided

vote, conditioned upon a penal bond in the amount of $25,000

(Order of December 28, 1970). Later the same Court required

that the bond be posted by February 1, 1971 (Order of Jan

uary 20, 1971). The Supreme Court reversed and eliminated

the bond requirement pending decision of the case in chief

on its merits by this Court. Board of Educ. of Little PopV

v. Clark, 401 U.S. 971 (1971).

On April 20, 1971, the Supreme Court rendered its

decisions in the "busing" cases. See Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., ___ U.S. ___, 28 L.Ed.2d 588 (1971).

Pursuant thereto, on May 4, 1971, this Court remanded this

case to the district court with instructions regarding timing

for preparation and presentation of appropriate plans, and

for decision. This Court indicated that appeals would be

expedited and decided prior to the opening of the 1971-72

school term (presently scheduled to commence August 31, 1971).

The District's Proposed Plan

The school district's initial plan submitted for

approval to the District Court on June 8, 1971, may be

summarized as follows:

(a) It proposed to continue grades 1 through 5

substantially unchanged, with pupil assignments e mg based primarily on a zoning system. Ac

cordingly, the racial composition of the elementary schools would continue to reflect the

racial composition of the neighborhoods in which

-10-

the schools were located except for the

dispersal of black students from Gibbs to seven western schools, see below.

(b) It proposed to desegregate the upper seven

grades by restructuring the grade levels. Grades

6, 7, and 8 would form one unit, grades 9 and 10 another, and grades 11 and 12 yet another.

There would be two eleventh and twelfth grade

schools, Hall and Parkview, both of which would

be located in the western (white) part of the

city, to accommodate the estimated 2900 pupils in those grades (DX 1009). Central and Mann,

located in the largely black central and eastern

areas of Little Rock, would house the estimated

3400 9th and 10th grade pupils (DX 1010). The

sixth, seventh and eighth grade pupils would be

placed in Dunbar-Gibbs, Pulaski Heights Junior- Elementary, Forest Heights, Henderson, and Southwest-Bale schools (DX 1011).

(c) it proposed to achieve substantial racial

balance in all of the secondary schools except

Gibbs-Dunbar, which would house approximately 50% of the black school population in grades

6, 7, and 8 (the middle school grade levels) in an identifiably black school.

(d) It proposed to assign the almost all-black student body of Gibbs elementary school, now

without a school, to seven western white

elementaries, while assigning the almost all-

white student bodies of Bale Elementary School

and Pulaski Heights Elementary School, now also

without school buildings, to other elementary

schools in zones contiguous to those of their former facilities.

(e) it proposed to afford transportation only to those pupils in the middle school grades (Tr. 229-30).

(f) It proposed to use black Booker Junior High School as an adjunct to Metropolitan High

School, a vocational-technical school, and to utilize a "choice" method of pupil assignment

tor that complex, with a shuttle bus service

between the Booker and Metropolitan building for academic classes (Tr. 218).

The stated approach of the school district in

drawing this plan was as follows: first, the district

-11-

established the goal of racial balance for every school

(Tr. 285). Then the board established criteria for meeting

that goal which included (a) cost to the district,mini

mizing disruption of grade structure, faculty, program and

activities; (c) minimizing inconvenience, transportation,

and the use of satellite zones (Tr. 211-12); (d) equalizing

of burdens of transportation; and (e) maximizing the use

of school buildings (Tr. 281-83).

_3/ The projected budget of the school district for the 1970-

71 school year was $14,413,905.00 (DX 103)[1970 trial]; the operating income of the district for the 1970-71 year

was $14,601,945.00. The budget projected for 1971-72 is $15,773,783.00 (Tr. 138).

The district does not have a school transportation system but does own one small bus it uses to transport physically

handicapped children (Tr. 171). other than this one bus,

it has not projected expenditure of any money for pupil

transportation (Tr. 143). The district has the power to

issue postdated school district warrants for the purchase of school buses (Tr. 501) and may borrow money from the

State Education Department revolving loan fund for the

purpose of purchasing buses and operating a transportation system (Tr. 486-87).

The district has approximately $3,500,000 in unspent

construction funds which are drawing interest (Tr. 157).

Such interest, as well as the interest on monies on deposit

in activity accounts, may be used in the board's discretion for general operating purposes (Tr. 154, 491).

During the trial, the district vigorously projected the

average annual cost of transportation per pupil to be $90, despite the fact that the Arkansas average is less than

$50 (Tr. 129) and that the Pulaski County School District

which surrounds the Little Rock and North Little Rock

districts, averaged less than $30 per pupil to transport

14,000 pupils an average of 25 miles each way each

day (Tr. 114, 498, 502). The district court found the

board's $90 projection to be too high (July 10, 1971 opinion, p. 16).

-12-

The defendants were advised by their counsel

that desegregation had to extend to every grade level and

that transportation would probably be required (Tr. 284-85).

In applying the criteria, the school district

created satellite zones in the black sections and assigned

pupils residing in those sections to distant white schools

(Tr. 212). The district also assigned all of the east

side black sixth grade pupils not included in the Gibbs-

Dunbar complex to distant white schools (Tr. 337-38).

Moreover, the district proposed to close Gibbs, most of

whose pupils are black, and transport these pupils to seven

distant white elementary schools (Tr. 264, 369). The

district did not use satellite zones to assign white pupils

to formerly black schools; nor did the district by any

method propose to assign white students below the ninth

grade level to formerly black schools, except for those

whites who lived in immediate proximity to. those black schools.

Pupils from Bale and Pulaski Heights Elementary Schools,

which were being combined with adjacent junior high schools,

were reassigned to other formerly white elementary schools

next to the closed facilities on a proximity basis (Tr. 257,

330-32, 428).

The rationale for the Board's apparently differ

ent treatment of black and white pupils was the desire to

maintain neighborhood schools (Tr. 295, 334, 412) in white

areas and the desire to prevent white flight (Tr. 212, 332)

-13-

or the anticipated creation of private schools (Tr. 333-34).

The rationale for continuing Dunbar-Gibbs as a black school,

as well as the present racially identifiable elementary

school arrangement, was the cost of transportation, estimated

to be approximately $150,000 for the Gibbs-Dunbar complex

students (Tr. 223) and between $383,850 and $461,790 for the

elementary students (Tr. 270-71, 322-23).

ffs 1 Proposed Alternative

Plaintiffs presented an alternative plan which

at the secondary level used the basic criteria and struc

ture established by defendants (Tr. 648-81). At the secon

dary level, the proposal was as follows:

(a) Three-year high schools would be continued.

School buildings used at this grade level would be the Central High School, and Hall High -

Forest Heights Junior High. The latter two

buildings, physically only two blocks apart,

would be combined to form one high school of

comparable capacity to Central. East-west

zoning generally along major transportation arteries would produce geographic zones of

comparable size and similar racial and socioeconomic proportions.

(b) At the junior high school level, there would

be a feeder school for each high school within

the identical geographic zone, rather than the

satellite zones proposed by the Board which it

has itself found objectionable in the past.

The proposed use of Henderson Junior High

under this alternative would not require further construction. r

(c) There would be three 6th and 7th grade

feeder schools into the 8th and 9th grade

schools, using contiguous east-west zones

basically parallel to those established for the

eight- to twelve-grade schools. Dunbar under

this alternative would be totally desegregated.

-14-

(d) Transportation would be provided for

homes^P±1S aSSigned two miles or more from their

Plaintiffs' elementary alternative was to pair

schools and to provide transportation to facilitate the

pairing. The proposed pairings closely followed those

submitted to the District Court during the August, 1970

hearings with the exception of those schools which were

eliminated as a result of being combined with junior high

schools. The defendants (Tr. 251, 274-75) and the District

Court (July 16, 1971 opinion, p. 13) conceded there was no

other effective way to desegregate the elementary schools.

The district did not devise an elementary plan because for

its plan to be successful, white majorities were required

in every school (Tr. 433) and "there was already in the

record a plan to do - the Walker plan - which did the only

thing that I could do, if you had finances and everything

to go that far" (Tr. 434). Although there were a number

of schools Within walking distance of each other in the

center of the city, which could be desegregated through a

pairing plan (the Beta complex), without transportation,

the district declined to offer it. The rationale offered

by the defendants was that such pairing would somehow promote

white flight (Tr. 335, 435).

The District's Proposed Alternative

On June 21, 1971, the district court orally ad

vised the school district that its plan would be rejected

primarily because it left Dunbar Junior High School

-15-

racially identifiable (Opinion of July 16, 1971, p. 5).

The court required the submission of an alternative plan,

and on June 28, 1971, the Board submitted, without endorse

ment, an alternative plan in a "Supplementary Report of

Defendants," which may be described as follows (see DX 1022)

(a) There would be three desegregated high

schools. The total enrollment in each would be as follows:

1* if that plan which allows seniors to

elect to remain in their present schools

were adopted, and dependent upon the drop

out factor and enrollment at Metropolitan:

Central between 1701 and 2204Hall » 1502 " 1701

Parkview •• i285 " 1466

2. If that plan which did not permit

seniors to elect to remain in their

present schools were adopted, and dependent upon the dropout factor and

enrollment at Metropolitan:

Central between 1931 and 2251Hall •• 1362 •• 1550

Parkview •' 1195 " 1370

Neither plan would fill Central to capacity

whereas under either plan, the use of portables

or some extraordinary alternative arrangement such as lengthening the school day would be

necessary at Parkview, and peril aps at Hall,

because of overcrowding (Tr. 772).

(b) There would be four desegregated junior high schools (8th and 9th grades), all of which would

be located in central or eastern Little Rock.

The ratios would range from 36.7% black at Booker

to 41.0% black at Mann. Permanent capacities of

schools, as taken from DX 8 [1965 trial](reproduced herein as Appendix "B") and projected enrollments are as follows:

School Capacity Enrollment

Booker goo 852

Dunbar 1000 837

-16-

School Enrollment

Mann ,

Pulaski Heights—

Capacity

1400 12951538 931

Total 4638 3945

There is thus capacity for 693 more pupils than are assigned at this level.

(c) There would be three desegregated middle

(6th and 7th grade) schools, all of which would

be in western Little Rock. The ratios would

range from 39.2% black at Forest Heights to

41.5% black at Henderson. The plan requires the

continuation of the enjoined Henderson Junior

High School construction. Capacity (from DX 8) and projected enrollments are:

Forest Heights

Henderson

Bale-Southwest

Total

1000s/ 1148

750^ 1353

1532 1402

3282 3903

Under this alternative, Gibbs would not be

combined with Dunbar, but would remain a black elementary

school; Centennial, a predominantly black school, would be

closed and its pupils distributed among the western white

elementaries which would have received the Gibbs pupils

(Tr. 787, 822).

This alternative contemplates contiguous north-

south zones for Central High School; "neighborhood schools"

4/ Since DX 8 was prepared, the permanent capacity of Pulaski

Heights Junior High School was enlarged from 750 to approx

imately 950 by construction permitted by the dis trict court

Iear ^ r‘ 345^* The Superintendent first testified that it had not been decided whether Pulaski Heights Elementary

for junior high grades under this alternative (Tr. 788), then that it would not be (Tr. 792) and finally

that it was considered a "swing" building available for uue in those grades (Tr. 822).

—/ The temporary capacity of the Henderson facility is pres-

ently 1000 students, having been enlarged by the addition of four portable classrooms to the site (Tr. 302-03).

-17-

for students living near Hall and Parkview, with east side

students transported from satellite zones; "neighborhood"

schools for junior high school students in central and

eastern Little Rock with satellite zones from the western

areas; and "neighborhood" middle schools in the west with

eastern pupils being transported to them. As proposed and

approved by the district court, students entering their

senior year in 1971-72 who attended Hall, Parkview or Central

last year and would be required to attend a different high

school under the board's zoning, will be permitted to elect

to remain at the school they attended last year. There

will be no such opportunity for Horace Mann students (Tr.

766) .

Plaintiffs retained their preference for their

alternative plan but established other approaches to the

school district's second proposal which would be preferable.

Besides using Hall, Mann (essentially equal schools, Tr. 463)

and Central and the senior high level, and Parkview at the

8th and 9th grade level (eliminating the need to lengthen

the school day), it was also noted that if Gibbs were

combined with Dunbar as originally proposed and that complex

used instead of Henderson for 6th and 7th grades, using

Henderson then for 8th and 9th grades, no construction at

Henderson would be necessary (Tr. 793-94).

-18-

Faculty Desegregation

The school district's 6-3-3 desegregation plan

requires certain administrative and faculty changes

involving, inter alia, principals,—^ vice principals, deans,

coaches, band and choral directors, and subject matter

department chairmen. The school district, pursuant to the

Arkansas Continuing Contract Law, is obliged to retain all

personnel for 1971-72. At the time of the hearing, however,

assignments had not been made nor had criteria for

making such arrangements been devised. The defendants

refused to use objective criteria in reassigning school

personnel (Tr. 808-12) and the District Court did not impose

such a requirement, holding that the adequacy of the district's

staff desegregation could be deferred until pupil desegregation

had been satisfactorily completed (July 10, 1971 Opinion,

p. 7). Under this approach, with the court's approval, all

black secondary principals, coaches, band directors, etc.

had been removed from the adjacent North Little Rock School

District (Tr. 809; see Transcript of Proceedings in the

companion appeal, Davis v. Board of Educ. of North Little Rock).

Plaintiffs showed apparent racial discrimination in thesenior high school principals' salary schedules. See

P X 2 0 0 0 -

Certifi- ExperienceName cation Dist. Total Deqree Salary Rai

Harry Carter Admin. 20 20 M.S. 14,887 WWeldon Faulk Admin. 18 18 M.E. 15,087 WEdwin Hawkins Sr.Prin. 19 30 M.S.E. 13,787 BAl Thalmueller Sr.Prin. 13 13 M.S.E. 14,289 WLeonard Spitzer Sr.Prin. 18 19 M.E. 14,487 W

-19-

The District Court's Ruling

On July 16, 1971, the district court issued a

Memorandum Opinion and Decree. The court ordered the

school district to implement its three-year high school

alternative plan for the 1971-72 school year, and to

furnish transportation to students assigned more than two

miles from their homes. The district court permitted the

continued operation of essentially segregated elementary

schools for yet another year, indicating that it would

require submission of a new plan for 1972-73 because it

reluctantly felt -that the federal appellate courts will

sooner or later require busing in districts like Little Rock

and North Little Rock where full integration cannot be

achieved by any other method" (July 16, 1971 opinion, pp.

14-15). The court did not, however, require the school

district to acquire additional transportation facilities

during the next school year in preparation for elementary

school integration at some subsequent date.

The district court declined to require the assign

ment of faculty and other staff according to objective

criteria and also denied plaintiffs' prayer for attorneys'

fees so as not to "burden the Board additionally at this

time beyond the financial strains which would be imposed

by compliance with its decree (July 16, 1971 opinion, p. 21).

-20-

ARGUMENT

I

The District Court Ignored Con

stitutional Requirements By Not Ordering Elementary School

Desegregation Earlier Than The 1972-73 School Year

The sad history of events relating to the deseg

regation of the Little Rock, Arkansas public schools bears

witness to unfortunate exploitation of the patience and

temperateness which have traditionally characterized courts

of equity. Since Brown v. Board of Educ.. 349 u.S. 294

(1955), the federal courts have at every juncture allowed

the greatest possible discretion to the Board of Education

of Little Rock to resolve "educational" and "administrative"

difficulties as a means of facilitating the desegregation

of the public schools. in every instance, the courts' tol

erance has been rewarded only by further entrenchment of

the very ill sought to be corrected, or further delay in

application of the remedy.^ it is with no small feeling of

5 V h? ^ery outset of this litigation, the Little Rock School Board adopted a gradual integration plan because t claimed financial inability to otherwise meet the cost

of aen^2 r̂ a£10nv,anc? that Lt needed to complete construction of a new high school in western Little Rock. See Aaron v

Cooper, 143 F. Supp. 855, 859 (E.D. Ark. 1956). The district

- L V f thlS Court declined to enjoin more rapid progress toward^a unitary system because of the district's "good

. i t 1 at 864~65; 243 F.2d at 364 (8th Cir. 1957). Although the federal court restrained state officials from

l ^ epfe5ing ^he execution of the plan, Aaron v. Cooper,r1Tf6^F; ^upp. 220 <E*D* Ark. 1957), aff'd sub nom. Faubusv. jJnited States, 254 F.2d 797 (8th Ci7Tr~affrd_iTIb S ^ o o o e r

I; 358 U,S* 1 (1958)' the school board subsequent!^® ! susPend desegregation because it was not popular ith the community. See Aaron v. Cooper. 163 F. Supp. 13 (e d r .), cert. denied, 357 U.S. 566, rev'd 257 F 2d 33 fRfh

Cir.), affld 358 U.S. 1 (1958). T h ^ o o l bo^d also

-21-

deja vu, therefore, that plaintiffs again ask this Court

to direct the integration of the Little Rock school system.

(cont'd)

attempted to frustrate integration by leasing public school

buildings to segregated private schools, see Aaron v. Cooper

261 F.2d 97 (8th Cir. 1958). While this action was declared

illegal, the courts did not require that it be undone by

opening the schools on an integrated basis since it was

presumed that the board would comply with the law. The re

sult was to delay any integration in Little Rock for another

year. See Aaron v. McKinley. 173 F. Supp. 944 (E.D. Ark.),

aff'd sub nom. Faubus v. Aaron, 361 U.S. 197 (1959).

Similarly, the district court approved the school board's use of the Pupil Placement Law in reliance upon the educa

tional and administrative problems the board said it encoun

tered m the desegregation process, although this Court found that Little Rock had applied the law so as to limit

desegregation. Aaron v. Tucker. 186 F. Supp. 913, 932-33

(E.D. Ark. 1960), rev1d sub nom. Norwood v. Tucker. 287 F 2d 798 (8th cir. 1961). Thus for six years Little Rock used

every opportunity afforded it by the courts to delay or

avoid integration. At the same time, the school district

undertook other actions which intensified segregation within

the school system. For example, in 1961 an all-white school

was made a "Negro" school. See Safferstone v. Tucker 235

Ark. 70, 357 S.W.2d 3 (1962). In 1963 the white East Side Junior High School was closed as nearby Booker Jr. High was

first opened. The former East Side students were not

however, assigned to the new building in order to integrate it, but to West Side (See Appendix A). in 1965 initial

assignments of all black students and an all-black faculty

were made to a new facility, although the district was

supposed to be operating on a free choice basis at that time

SZrd v- Board of Directors of Little Rock School Dist

C^* No-.lr-657C-142 (E.D. Ark. 1965). Thus, nearly a'decade after this litigation began. Little Rock had managed to

delay integration and reinforce the racially distinctive

operation of its schools. it also took advantage of the

delays gained to implement a construction program which is

at the root of the "educational" and "administrative"

difficulties it now claims impede integration of its schools (see below).

-22-

More than a year ago, following exhaustive

briefing, extended oral argument en banc, and "deliberate

consideration," this Court directed that a plan be adopted

for Little Rock so that "no person is to be effectively

excluded from any school because of race or color," with

such plan to "be fully implemented and become effective

no later than the beginning of the 1970-71 school year."

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock. 426 F.2d 1035,

1046 (8th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, ___ U.S. (1971)

(emphases supplied). The school district's response in the

summer of 1970 was to file plans for junior high and

elementary schools "which will not disestablish those

schools as racially identifiable units." Clark v. Board

of Educ. of Little Rock. Civ. No. LR-64-C-155 (E.D. Ark.,

August 17, 1970)(Memorandum Opinion at p. 3).

The school district sought to justify its foot-

dragging in its last Brief to this Court (Brief for Appellees

and Cross-Appellants, Nos. 20485, 20568) by an oblique

reference to "the appropriate construction of the mandate

of Alexander v. Holmes County, supra, in a metropolitan

school district . . . " (P. 20); the notion that Alexander

meant one thing in rural school systems and another in city

systems had been decisively rejected in March, 1970,

Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis. 397 U.S. 232 (1970).

In 1971, following remand from this Court for

submiss:on of a plan of desegregation "effective at the

-23-

beginning of the 1971-72 school term" and appropriate action

by the district court "in order that all of the schools in

the Little Rock School District shall be desegregated"

consistent with the Swann decisions, Clark v. Board of

Educ. of Little Rock. No. 20485 (8th Cir., May 4, 1971)

(emphasis supplied), the school district again submitted

plans which called for virtually no change, and continued

racially identifiable schools, at the elementary level.

V* B£ard of Educ. of Little Rock, civ. No. LR-64-C-155

(E.D. Ark., July 16, 1971)(Memorandum Opinion, pp. 4-6).

And at the junior high school level, despite the district

court s warning in 1970 that "[h]owever progressive or

enriched the District's program for students living east

of the Broadway-Arch Street line may be . . . a program for

black students in a largely black school complex" could be

approved only for 1970-71, Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little

Rock, 316 F. Supp. 1209, 1214 (E.D. Ark. 1970). the school

district's preferred submission did "not comply with the

[District] Court's 1970 decree relating to the secondary

schools because it leaves Dunbar with a black enrollment of

more than 90 percent which would quickly become 100 percent."

Clark, Memorandum Opinion of July 16, 1971, p. n.

Time after time the federal courts have abstained

from ordering or requiring; they have acquiesced in pleas

for additional time — additional years of segregated

schooling for black children — for this school district to

-24-

Yet inwork out the wrinkles of its desegregation plans,

the final analysis, the district has done nothing to earn

the encomiums of "good faith" heaped upon those who, by

subtle appeal to moderation, manage to achieve as much and

more than those who choose the path of outright resistance.

Unfortunately, the rulings of the district court

since this Court's 1970 decision have sanctioned every

delay in desegregation. On August 17, 1970, despite the

language of Alexander, Carter^ and Northcross. and the

clear direction of this Court in its 1970 opinion, the

district court required no desegregation of Little Rock

elementary schools which "are and will be essentially as

racially identifiable as they have been" because the district

court somehow concluded that, while it was the only remedy

that would work, the law did not require "the massive trans

portation of elementary school students for the sole purpose

of disestablishing a unitary elementary school system or

subsystem." Though effectuation of constitutional rights

hung in the balance, the district court merely noted that

if it had erred, "it will learn of its error in due course.-^

8/ Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd.. 396 Ti s (1969), 396 U.S. 290 (1970).

9/ We are compelled to add that the appellate judicial process

m 1970 defaulted on what we consider its duty to afford effective access to appellate review of evidently lawless

decisions. While this Court's May 4, 1971 remand in light of

Swann attempted to avoid a repetition of last year's events

by requiring action below in time for review here prior to

school opening, the district advantaged itself of the delay

creating continuing practical problems. For example, although

it was clear more than a year ago that a pairing-transportation

-25-

Again this year, the district court has pointedly

ignored both this Court's directive and the school district's

wilful failure to propose an acceptable elementary plan.

Rather than putting the district under an effective mandate,

the district court has repeated "its opposition to busing

["particularly at the elementary grade levels and involving

young children"] for that purpose" [desegregation] and has

approved racially identifiable elementary schools for the

1971-72 school year. The district court has indicated that

" [a]s of the opening of school for the 1972-73 session, the

elementary grades must be integrated satisfactorily" but

has not yet established any date by which the school district

must take advantage of this latest opportunity to submit a

new elementary plan.

The foregoing establishes, we believe, that the

fact that Little Rock's elementary schools remain segregated

today is not caused solely by physical, educational or

administrative problems beyond the control of either school

district or federal court. Rather, there has been a pattern

of refusals to act by the school authorities which has been

explicitly or implicitly sanctioned by the district court,

(cont 'd)

plan would be necessary to desegregate the elementary schools,

yet during 1970-71 the school district neither prepared its

own plan for that purpose nor sought to acquire the vital transportation capability.

-26-

culminating in the order from which appeal is taken, which

postpones elementary school desegregation yet another year

In Kelley v. Metropolitan County Bd. of Educ. of

Nashville, 436 F.2d 856, 862 (6th Cir. 1970), the Court said

It is clear to us that the rights of

school children to schooling under nondis-

criminatory and constitutional conditions cannot be recaptured for any school

semester lived under discriminatory practices.Nor can any court thereafter devise an effective remedial measure.

r̂’or that reason, the Court of Appeals in Kelley reversed

a district court decision suspending further proceedings

to effectuate desegregation in Nashville pending the Supreme

Court's decision in Swann because

[w]e believe that "the danger of denying

justice by delay" in this case is as

clear as it was in Alexander, supra; Green

v* County Board, supra, and Carter. supra.

The continuing vitality of Alexander v. Holmes County Bd,

of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969) has recently been reemphasized

by the Supreme Court. in a June 30, 1971 per curiam order

in Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville (unnumbered)(see

Appendix "C"), the Court said:

The United States District Court for the

Eastern District of Tennessee has not had

an opportunity since the June 22, 1971

remand of the case by the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit to inquire whether respondents have failed

to maintain a unitary school system as

in Swann v. Char lot te— Mecklenburg

Board of Education. ___ U.S. ___ (1971),

and prior cases. of course, the District

Court must conduct forthwith such proceedings as may be required for the prompt

determination of this question, and,

-27-

should it find that respondents have not maintained a unitary school system

respondents must terminate dual school

once. . . . » Alexander v. golmes^County^Board of Education. 396

(emphasis supplied). Yet the order of the district court

entered herein July 16. 1971 proposes the assignment of

elementary school students for this chool year according

to the geographic attendance zones which this Court has

held were unconstitutional from their inception in 1969.

The Fifth Circuit has very recently passed upon

a situation identical to that presented here: the district

court in savannah had ordered high school integration only

for the current school year and delayed elementary deseg

regation until 1972. in a per curiam order, the entire

text of which follows, the Fifth circuit rejected any

further delay:

U i* ukuered that Appellants' Motion for Summary Reversal of the District Court's order of June 30, 1971, is to be held in

abeyance pending a report to this Court

Dlstrict Court of its action on the case following the Board's progress report of August 5, 1971. P

The District Court in its June 30, 1971 order approved the Board's plan for zoning

student assignment, and transportation on

snbmf^°?dary sch°o1 level* This plan was submitted as a modification of a prior plan

ig?n°VJd £y .the Disfcrict Court on July 18, ' 19/0, to bring the Savannah-chatham school

mS ? " int° colt,Pliance with Swann vs Charlotte-

1267 r?9 7 ?? BSard,°f Education, 91 Sup ct TuW 7 ? decided APril 20, 1971. The

foiYo7197° £lan Waf' however* left standing or elementary school because the District

Court questioned the feasibility of preparing

-28-

and implementing a new plan for the 1971-

72 school year. The Board was directed

to present the District Court with a plan

by April, 1972, and possibly sooner. A

progress report is due August 5, 1971.

h. delay of this nature in implementing a_ unitary school system at any level is not

permissible under the precedents of this

Court or the United States Supreme Court.

Nevertheless, this Court is reluctant to

order a summary reversal when such an order

may be rendered unnecessary by action of

the District Court following the August 5th report of the Board. The District Court

should report to this Court on its action as soon as possible, but not later than August 10, 1971.

ste11 v- Savannah-Chatham Bd. of Educ.. No. 71-2380 (5th

Cir. , August 2, 1971) (Thomberry, Morgan, Clark, JJ. ) (emphasis

supplied).

We do not suggest disagreement with the district

court's finding that Little Rock cannot, at this moment,

completely implement an elementary school desegregation plan

on the presently scheduled first day of the 1971-72 school

term in September, 1971. We do insist, however, that that

fact is the result of the school district's refusal to act

and in no way justifies the approach adopted by the dist

rict court; certainly, more than nothing at all can be done.

Last year plaintiffs were in much the same

posture. The district had no money and no buses for

integration, it said, and the capacity of Twin City Transit

was limited. it proposed no desegregation at the elementary

level. Plaintiffs, with the assistance of an educational

expert, developed a plan to totally desegregate all Little

-29-

Rock schools and presented it to the district court. We

suggested to the Court at that time that it should approve

plaintiffs' plan (the only plan before the district court

which met the constitutional requirements) and order its

implementation as soon as feasible, while at the same time

enjoining the school district to take the necessary steps

forthwith to be able to implement the plan.-^^

This year, plaintiffs modified the proposals put

forth in 1970 so as to better conform to the basic proposals

of the school district at the secondary l e v e l . A g a i n

the school district proposed only a partial plan, without

any significant elementary school desegregation at all.

Again the district court ignored plaintiffs' proposals.^/

W c*a^cteriZed this approach, in their Briefo this court last year, as some sort of concession

distrf^ a: n apP 1Xtd dl£ferently in metropolitan and rural ^ * ,Tt 1S not such* but rather an attempt to

The wi S L ~ o>Xand^r rUle rec5uirin<? integration pendente lite. The wisdom of such a course is demonstrated by the failur^—f the school district, absent a specific injunction to

t?ansno^S^ePS whats?ever in 1970-71 to acquire additional transportation capacity — thus virtually assuring that

complete integration in 1971-72 would bean impossibility.

— ^ ®Pecific objections to the school districtssecondary plan are treated below.

12/ "The court has considered the alternative plan sub-

mitted by plaintiffs and the original intervenors

Assuming that their plan would effectively integrate the

District C°Urt is not 9°ing to impose it on the

-30-

Again the district court has tolerated the school dis

trict's outright refusal to take any steps toward elementary

desegregation; and again the district court has set no

meaningful time limits to guard against a repetition next

year of this year's and last year's events. Meanwhile,

the class of black plaintiffs continues in segregated

elementary schools.

We earnestly plead for remedial action from this

Court. The law is clear. The violation of the law

sanctioned below is clear. This Court must now act as

the district court should have acted. We respectfully

suggest the following:

(1) Plaintiffs' plan for elementary schools

and secondary schools should be approved and ordered

implemented as the only plan in the record, at the elem

entary level, which meets constitutional standards, united

States v. Board of Educ. of Baldwin County. 423 F.2d 1013

(5th Cir. 1970). Those parts of the plan which are capable

of immediate implementation should be so implemented (e.g..

the Beta complex contiguous pairing). The entire present

transportation capability of the district should be strained

to the utmost to permit immediate implementation of as much

desegregation as possible. Alexander v. Holmes County Rd

oOduc^, supra; Goss v. Board of Educ. . supra.

-31-

(2) The school district should be mandatorily

enjoined to acquire at the earliest possible moment

sufficient transportation capability to entirely imple

ment the plan, and in light of its repeated past failures

to act, it should be placed under frequent progress reporting

provisions. E ^ , Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenhnrg ad. of

Educ^, civ. No. 1974 (W.D.N.C., June 29, 1971)(monthly

reports to district court required).

(3) The district court should be directed to

consider delaying the opening of school for a short period

of time should it appear that with such a delay substantially

greater desegregation could be achieved. See United States

V* - -Xas Education Agency, 431 F.2d 1313 (5th cir. 1970).

(4) The school district should be required to

utilize such additional buses as it acquires immediately

upon their acquisition so as to further increase desegre

gation of the schools. see Mapp v. Board of Educ.

Chattanooga, civ. No. 3564 (E.D. Tenn., July 26, 1971)

(full desegregation plan approved but complete implementation

delayed until transportation facilities available).

(5) None of the foregoing should be construed

to prevent the school district from proposing new alterna

tives to the district court which achieve "the greatest

possible amount of actual desegregation," Swann, provided

that the order should not be modified by the acceptance

of any plan which does not achieve at least as much deseg

regation as is projected under plaintiffs' plan. Pate v.

Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1151 (5th Cir. 1970).

-32-

II

The District Court Erred In

Refusing To Require Assignment

Of Faculty And Staff Members

In Accordance With Objective

Criteria

Plaintiffs sought, in the district court, to

require the Little Rock School District to assign faculty

and staff members on the basis of objective criteria. The

district court lectured the school authorities for several

pages of its opinion on their duty to avoid discrimination

against black faculty and staff members during the deseg

regation process but refused to require any protective

steps to avoid such discrimination. Rather than requiring

the selection of personnel on some reviewable, objective,

nondiscriminatory basis, the district court merely "commented"

that "the Board should make every effort to incorporate into

the unitary system specialized Negro personnel such as

athletic coaches, band directors, and similar categories of

employees" but "the Little Rock's principal integration

problem relates to student assignments, and until that

problem is solved satisfactorily the Court is not inclined

at this ̂ age to interfere with individual assignments of

staff members and teachers or to impose on the Board objec

tive criteria in such assignments to the exclusion of

everything else" (Opinion of July 16, 1971, pp. 7-8) ^

13/ The last time the district court "suggested" something

to this school district, its warning was of no avail

and further constitutional difficulties were created. in

its September 24, 1970 opinion, the district court declined

to enjoin further school construction at Henderson Junior

High School but added "that the Board would be well advised not to commence work without the prior approval of this

Court or of the Court of Appeals." 316 F. Supp. at 1216.

-33-

else, 11 of course, means wholly subjective

cr *̂'er^a with their vast potential for arbitrary action.H/

For example, despite plans to phase out Mann High School

and a vacant principalship at Hall last year, the school

district assigned a white to that position who had less

experience than the black principal of Mann, Edwin Hawkins,

and who subsequently was paid at a higher rate than Mr.

Hawkins. See note 6 supra. This was justified on the

grounds that Mr. Hawkins was "better suited" to deal with

the problems at Mann; in other words, a black principal

should be assigned to a black school.

The factual setting of this claim is by now a

familiar one to this Court. in the process of desegrega

tion in Arkansas, school districts often realize operating

efficiencies which result in staff reduction or the elimin

ation of some positions. Walton v. Nashville Special School

Dist^, 401 F.2d 137 (8th Cir. 1968). in the past two years,

for example. Little Rock has variously proposed the closing

(cont *d)

Nevertheless, "the Board without taking the matter up with

the United States District Court, or the Court of Appeals,

or with counsel for the plaintiff, advertised for bids and

awarded a construction contract" (Clark v. Board of Educ

— yLltt?-f Ro<:k' No- 20485 (8th Cir., Feb. 27"l97l) (dissenting opinion)) and the matter was eventually resolved by the

Supreme Court of the United States, which halted construction. Board of Educ. of Little Rock v. Clark. 401 U.S. 971 (1971)

It should have been apparent to the district court that

this school district can only be given guidance in the form of mandatory orders.

11/ Cf,» Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ 364 F-2d 189, 192 (4th Cir. 1966).

-34-

of the Mann, Booker, West Side, Gibbs, Centennial, Bale,

Pulaski Heights Elementary, and Lee schools. Under the

plan approved by the district court, Mann will no longer

operate as a high school; Centennial and Lee will be closed.

Coincident with such school closings has often

occurred the wholesale dismissal of black teachers and

E-9* > Smith v. Board of Educ, of Morrilton. 365 F. 2d

770 (8th Cir. 1966); Jackson v. Wheatley School Dist.. 430

F.2d 1359 (8th Cir. 1970). Mr. Patterson testified that

where there were 134 black secondary school principals in

Arkansas in 1967, only 15 remained throughout the State in

1971 (Tr. 577). Anticipation of similar occurrences in

this district is not just fanciful thinking. The record

in the summer of 1970 established in considerable detail

the difficulties faced by black educators in Little Rock and

North Little Rock as a result of the phasing out of various

black schools. Particular stress last year was laid upon

treatment of black athletic personnel.

This year, under the school district's proposed

plan, there will be significant grade restructuring and

considerable shifting of personnel. Plaintiffs sought to

have the school district apply objective criteria to such

reassignments. in Haney v. County Bd. of Educ.. 429 F.2d

364, 371 (8th Cir. 1970), this Court directed that the

school board should be ordered to set up

definite objective standards for the

employment, retention, transfer and

assignment of teachers on a non-racial,

-35-

nondiscriminatory basis and to apply

these standards to all teachers impartially

in a manner compatible with the requirements of the Equal Protection clause of the United

States Constitution. . (emphasis supplied)

Thus, the law requires much more than the precatory language

of the district court.

Plaintiffs sought to bind the district to a

nondiscriminatory, objective assignment policy now so as to

avoid the necessity of further litigation after the fact —

not just for reasons of judicial economy but because, as

this Court has recognized, class relief is appropriate

because staff members who are discriminated against but

retained in some capacity may be reluctant to initiate

remedial litigation for fear of further jeopardizing their

positions. Arkansas Educ. Ass'n v. Board of Educ. of

Portland, No. 20,412 (8th Cir., July 26, 1971)(slip op. at

P- 5) .

Despite the school district's contentions, in

the context of a desegregating school system, the decision

who shall be assigned to principalships and other faculty

and staff positions is not purely an administrative task

left to the unfettered discretion of the board. See, e.g.,

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ.. Civ. No. 70-251 (N.D.

Ala., July 13, 1971) (reprinted as Appendix "D").

Given the right to nondiscriminatory assignment

of teachers and staff, Haney, supra, the school board should

-36-

be required to adopt reviewable objective standards in

advance of their application. Lee v. Macon County ah

— ' S-Upra; Bo,lfe v. County Bd. of Educ. . 282 F. Supp.

192, 200 (E.D. Tenn. 1966), affd 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir.

1968); cf. United States v. Sheet Metal Workers. 416 F. 2d

123, 136 (8th Cir. 1969).

-37-

Ill

The Plan Approved By The District

Court Closes Black Schools, Overcrowds White Schools And Places

Heavier Burdens in The Desegregation

Process Upon Black Students, All For

Impermissible Racial Reasons

Last year, the Little Rock School District proposed

a senior high school plan which called for the closing of

the black Horace Mann High School and assignment of its

black students to Central, Hall and Parkview, each of which

was initially built and operated as a white school. The

district court approved the plan over plaintiffs' objec

tions that the burden of desegregation was being unfairly

cast upon the black community, and also permitted the school

district to undertake construction of a substantial addition

to the almost all-white Henderson Junior High School, the

westernmost Little Rock junior high. Plaintiffs appealed

on both issues to this Court, which considered the questions

raised serious enough to unanimously authorize the halting

of construction at Henderson pending a decision on the

merits of the claim that the plan discriminated against

black students.

None of the issues were decided, however, in this

Court's brief remand order issued May 4, 1971 in light of

the Swann decision. Instead, the case was returned to the

district court for reconsideration of all issues, including

the propriety of the Henderson construction. Again this

year, plaintiffs return to this Court raising the same issues

in the context of the new plans.

-38-

The questions are separable and yet related. As

to the Henderson construction, it may be viewed as follows:

(1) should the construction be permitted in light of the

location of the school, the demographic patterns in Little

Rock, and the history of the school district; (2) should

it be permitted considering the above factors and also the

existence of as much capacity in existing facilities as is

to be added at Henderson; and (3) should it be permitted

where it is an essential ingredient of a desegregation plan

which deliberately maximizes the assignment of black students

to white schools and minimizes the assignment of white

students to black schools? As to the desegregation plan

itself, the questions are (1) whether it is preferable to

the other alternatives available to desegregate the secon

dary schools which do not result in closing black schools

or underfilling them while overcrowding white schools; and

(2) whether the district justified its selection where the

record shows the reasons advanced were inconsistently applied

at best, and the choice was admittedly made on racial grounds.

The plan approved this year does not close Mann

High School outright, as had been contemplated in 1970.

However, it does reduce Mann to the status of a lower grade

school while retaining as graduating high schools the

three traditionally white Little Rock high schools: Central,

Hall and Parkview. Last year, black tenth, eleventh and

twelfth graders who would in the past have attended Mann

were to be assigned to central and western schools, thus

-39-

bearing the entire burden of desegregating the upper grades,

and the district proposed to furnish no transportation to

students who were not eligible for Title I assistance.

This year the situation remains the same except that the

district court required students more than two miles from

their assigned schools to be given transportation; but now

having presented a plan for additional lower grades, however,

the school district contends that the burden is equalized

by the requirement that 8th and 9th grade white students in

western Little Rock must come east to attend Booker, Mann,

Dunbar and Pulaski Heights. (However, 6th and 7th grade

blacks again shift west to attend Forest Heights, Southwest

and Henderson).

The acceptability of this proposal cannot be

determined by simple mathematical calculation; it must be

examined in light of the rationale for its selection and the

comparative impact of available alternatives.

It seems fairly obvious from the chronology of

school district proposals in this case that the objective

has been to avoid the assignment of white students to black

schools. Last year the Board proposed to close Mann en

tirely; this year it will not be a senior high. The district's

first junior high scheme this year was to close Booker as

a separate facility and make it an annex to the "racially

neutral" Metropolitan High, to continue Dunbar as a heavily

black school but assign other black junior high students

(from Booker) to white western schools. Elementary black

-40-

students displaced if Gibbs were combined with Dunbar

would be assigned west (as the predominantly black students

of Centennial are under the final plan) but similarly

situated whites from Bale and Pulaski Heights Elementary

Schools would remain close to their western "neighborhoods."

When the plan was revised because the district

court refused to permit operation of Dunbar as a black

school, the idea of closing Booker was abandoned and the

drastic imbalance of transportation favoring white students

lessened, but black students still must bear a dispropor

tionate share of the burden because the district selected

a plan which underutilizes the formerly black schools near

them and overcrowds the white schools, thus forcing the

additional construction at Henderson and the use of portables

or a longer school day at Parkview.

There are alternatives to accomplish desegregation

which do not present these problems. The district's reasons

for not choosing them are inconsistently applied. For

example, one justification for not assigning more students

to Central High (which might have reduced the transporta

tion burdens on blacks) was that Central would be much

larger in enrollment than Hall or Parkview. That has cer

tainly never bothered the school district in the past. m

1956 Central had 2475 students, Mann 582; in 1960 it had

1693, Hall 889 and Mann 821. In 1964 it had 2286 students.

Hall 1558 and Mann 1239. See Brief of Appellant. in No.

-41-

19795, p. 34. Besides, plaintiffs' alternative plan

proposed central and Hall-Forest Heights as two senior

highs of comparable size.

The Superintendent's criticisms of plaintiffs'

Plan were unfounded. He did not like clustering Hall and

Forest Heights, he said (Tr. 715) because it was dangerous

to cross University Avenue, but he acknowledged that

children presently do so (Tr. 727). m any event, a shuttle

bus between the buildings was originally proposed by the

school district for Booker-Metropolitan, so why not for

Hall-Forest Heights? He also pointed out that Forest

Heights was designed as a junior high school (Tr. 718)fas

was Booker] but admitted that related problems could be

worked out by appropriate scheduling (Tr. 729). He criti

cized certain parts of the plaintiffs' plan but discovered

that the Board's proposal operated in exactly the same

fashion (Tr. 724, 732-33, 742).

The district's plan, utilizing Parkview as a

senior high school, overcrowds it and necessitates the use

of portables or a lengthened day but substitution of Mann

as the senior high school would obviate this since its

capacity is greater. Similarly, the Superintendent admitted

that if the Dunbar-Gibbs complex were established and used

to house the 6th and 7th graders the school district pro

posed to send to Henderson (and Henderson used for 8th and

9th grades) there would be no need for the construction there.

(Tr. 793-94).

-42-

selected.The real reason why the school district

first, alternatives which underutilized or closed black

schools, overcrowded white ones, and necessitated expensive

additional construction, and second, selected Parkview over

Mann as the third high school, ^ 7 were racial reasons. This

was admitted by the Superintendent, who testified that:

white elementary students from closed Bale and Pulaski

Heights Elementary Schools were not assigned to desegre

gate schools in eastern Little Rock because of fears that

they would not attend, or would start private schools (Tr.

332, 334); the recommendation last year to phase out Mann

was based on the supposition that if whites were assigned

to the school, they would not attend (Tr. 391); Parkview

was selected as a high school over Mann for the same reason

(Tr. 763-64).

Under these circumstances, it has repeatedly been

held that the plan must be rejected as discriminatory.

~aney v‘ .County Bd. of Educ.. 429 F.2d 364, 372 (8th Cir.

1970), in this Circuit, establishes that black schools may

— 7 do not contend that Mann must necessarily be oper-

a*ed af.a sen3-or hl9h school. For example, we proposed an alternative which does not so use it, but instead desia- nates Central and Forest Heights-Hall as high schools in a

L5ever1Cweado1thi^kethiSPr°P?rti0nate burdens of defendants' ' do think the question of discrimination is

lastvear V ” Ught °f the dlstricfs proposald i e t e d totally phase out Mann -- when the schoolistnct proposes three senior high schools and chooses to overcrowd Parkview rather than utilize Mann's capacity?

-43-

not be closed for racial reasons. Accord. Smith v. St.

Tammany Parish School Bd.. 302 F. Supp. 106 (E.D. La. 1969).

Recent decisions of other courts have dealt with factual