Peterson v. City of Greenville, South Carolina Brief of Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 2, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Peterson v. City of Greenville, South Carolina Brief of Respondent, 1961. ddfa321a-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/21f7059f-d772-4517-b576-e92b0da2fe24/peterson-v-city-of-greenville-south-carolina-brief-of-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

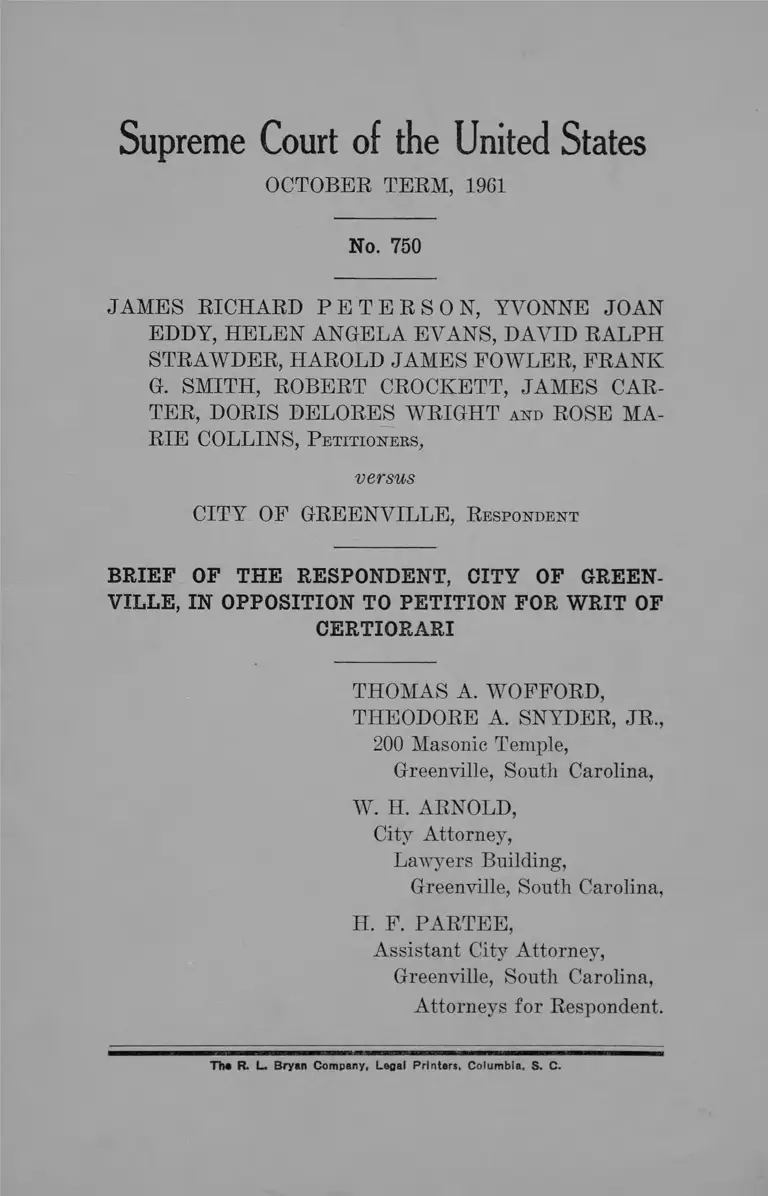

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1961

No. 750

JAMES RICHARD P E T E R S O N , YVONNE JOAN

EDDY, HELEN ANGELA EVANS, DAVID RALPH

STRAWDER, HAROLD JAMES FOWLER, FRANK

G. SMITH, ROBERT CROCKETT, JAMES CAR

TER, DORIS DELORES WRIGHT and ROSE MA

RIE COLLINS, P etitioners,

versus

CITY OF GREENVILLE, R espondent

BRIEF OF THE RESPONDENT, CITY OF GREEN

VILLE, IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI

THOMAS A. WOFFORD,

THEODORE A. SNYDER, JR.,

200 Masonic Temple,

Greenville, South Carolina,

W. H. ARNOLD,

City Attorney,

Lawyers Building,

Greenville, South Carolina,

H. F. PARTEE,

Assistant City Attorney,

Greenville, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Respondent.

The R. L. Bryan Company, Legal Printers, Columbia, S. C-

INDEX

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ 1

Questions Presented ......................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved . . . . 2

Respondent’s Statement of the Case ............................... 3

Argument:

I. The petitioners were not deprived of the due

process of law and equal protection of the laws se

cured to them by the Fourteenth Amendment in

their trial and conviction for trespass........................ 4

II. The decision of the Supreme Court of South

Carolina is in accord with the decisions of this

Court securing the right of freedom of speech under

the Fourteenth Amendment...................................... 14

A. The conviction of petitioners of tres

pass after their refusal to move from a lunch

counter in a private store did not interfere with

their right of freedom of speech..................... 14

B. The petitioners were not denied free

dom of speech in being convicted under a tres

pass statute which does not expressly require

proof that the person ordering them to leave

establish his authority at the time of making

the request ........................................................... 17

Conclusion .......................................................................... 20

P age

( i )

i f . . . . . . . . . .

.

: tm t

.

■

)• . „ . ............ .. - ■

■

s f ‘ , i V ; f f f ' t " i l i i l

.

'

.

.

0:' ..............................................................

Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 U. S. 250 ............................. 15

Brookside-Pratt Mining Co. v. Booth, 211 Ala. 268, 100

So. 240 ............................................................................ 12

Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454 ................................ 9

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622 ............................... 16

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U. S. 3 ........................................ 8

Commonwealth v. Richardson, 313 Mass. 632, 48 N. E.

(2d) 678 .......................................................................... 16

Fiske v. Kansas, 274 U. S. 380 ........................................ 14

Garner v. Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 164 and Footnote 11 4

Giboney v. Empire Storage & Ice Co., 336 IT. S. 490 .. 17

Gitlow v. New York, 268 U. S. 652 .................................. 14

Griffin v. Collins, 187 F. Snpp. 149 (Md.) ..................... 13

Grimke v. Brandon, 1 Nott & McCord 356 (10 S. C. Law) 9

Gross v. Rice, 71 Maine 2 4 1 .............................................. 8

Hague v. C. I. O., 307 IT. S. 496 ...................................... 15

Hall v. Commonwealth, 188 Va. 72, 49 S. E. (2d) 369,

App. Dismissed, 335 U. S. 875, Reh. Den., 335 U. S.

912 .............................................................................. 13, 15

Henderson v. Trail ways Bus Company, 194 F. Supp.

423 (E. D. Va.) ............................................................... 13

Lyles v. Fellers, 138 S. C. 31, 136 S. E. 1 8 ..................... 9

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 IT. S. 501 .................................... 15

Martin v. City of Struthers, 319 IT. S. 1 4 1 ..........13, 14, 16

Meyers v. Anderson, 238 IT. S. 368 ................................ 8

Saia v. New York, 334 U. S. 558 .................................... 15

Schneider v. State, 308 IT. S. 1 4 7 .................................... 15

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 .................................... 8

Shramek v. Walker, 152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331 ............. 10

Slack v. Atlantic White Tower System, Inc., 181 F.

Supp. 124 (Md.) ............................ .......... ............ 7

State v. Bodie, 33 S. C. 117, 11 S. E. 624 ....................... 10

State v. Bradley, 126 S. C. 528, 120 S. E. 248 .. .10, 11, 12

State v. Brooks, 79 S. C. 144, 60 S. E. 518 ..................... 10

TABLE OF CASES

P age

( i i i )

TABLE OF CASES—Continued

P age

State v. Clyburn, 247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. (2d) 295 . . . . 6

State v. Hallback, 40 S. C. 298, 18 S. E. 9 1 9 ................. 18

State v. Lightsey, 43 S. C. 114, 20 S. E. 975 ........10, 11, 12

State v. Tenney, 58 S. C. 215, 36 S. E. 555 ..................... 18

State v. Williams, 76 S. C. 135, 56 S. E. 783 ................. 10

Sumner v. Beeler, 50 Ind. 341 ......................................... 8

Teamsters Union v. Hanke, 339 U. S. 470 ..................... 17

Terminal Taxicab Co. v. Kutz, 241 U. S. 252, 256 .......... 7

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U. S. 8 8 ........................ 15, 16

Tucker v. Texas, 326 U. S. 5 1 7 ........................................ 15

Watchtower Bible & Tract Society v. Metropolitan Life

Insurance Co., 279 N. Y. 339, 79 N. E. (2d) 433 .......... 15

Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. (2d)

845 (4th Cir.) .................................................................. 7

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

Act No. 743, 1960 South Carolina General Assembly,

R 896, H 2135................................................................3, 11

Civil Rights Act of 1875 .................................................... 8

Code of City of Greenville, 1953, as Amended, Section

31-8 ................................................................................... 8

Constitution of the United States, Amendment I ..............2

14, 17, 20

South Carolina Code of Laws, 1952, Section 16-382 . . . . 11

South Carolina Code of Laws, 1952, Section 16-386 . . . . 11

South Carolina Code of Laws, 1952, Section 16-388 . . . . 20

United States Code, Title 28, Section 1257(3) .............. 1

United States Code, Title 42, Section 1983 .................... 7

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Annotation, 1 A. L. R. 1165 ............................. ............... 6

Annotation, 9 A. L. R. 379 ................. ............................. 12

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1961

No. 750

JAMES RICHARD P E T E R S O N , YVONNE JOAN

EDDY, HELEN ANGELA EVANS, DAVID RALPH

STRAWDER, HAROLD JAMES FOWLER, FRANK

G. SMITH, ROBERT CROCKETT, JAMES CAR

TER, DORIS DELORES WRIGHT and ROSE MA

RIE COLLINS, P etitioners,

versus

CITY OF GREENVILLE, R espondent

BRIEF OF THE RESPONDENT, CITY OF GREEN

VILLE, IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI

JURISDICTION

The petitioners invoke the jurisdiction of the Supreme

Court of the United States pursuant to Title 28 U. S. Code,

Section 1257 (3), upon the ground of deprivation of rights,

privileges and immunities claimed by them under the Con

stitution of the United States. The respondent, City of

Greenville, objects to the jurisdiction of this Court on the

ground that no substantial Federal question was presented

at any stage of the proceedings below and upon the ground

that the issues below involved property rights only and

the petitioners were not deprived of any rights, privileges

or immunities secured by the Constitution of the United

States.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The respondent, City of Greenville, denies that the

petitioners have been deprived of any rights secured to

them by the United States Constitution. However, for the

purpose of argument, the respondent will assume that the

questions to be considered are those presented by the peti

tioners as modified below.

The respondent, subject to its reservations, submits

that the questions presented are as follows:

Whether Negro petitioners were denied due process of

law and equal protection of the laws as secured by the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States:

1. When arrested and convicted of trespass for refus

ing to leave a department store lunch counter after demand

was made for them to depart by the manager of the store.

2. Whether petitioners, as “ sit-in” demonstrators, were

denied their First Amendment freedom of speech right as

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment when (a) convicted

of trespass upon refusal to move from a lunch counter

which was reserved for the use of white persons and (b)

when the convictions rest on a statute which does not spe

cifically require proof that petitioners were requested to

leave by a person who had established his authority to issue

such request at the time of making the request.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PROVISIONS

INVOLVED

In addition to the Constitutional and statutory pro

visions cited by the petitioners on page 3 of the Petition

this case involves the First Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States.

2 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent

Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent 3

RESPONDENT’S STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The petitioners were each tried and convicted in the

Recorder’s Court of the City of Greenville, South Carolina.

They were charged with violating Act No. 743 of the 1960

South Carolina General Assembly, R 896, H 2135, now

Section 16-388, Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952. The

statute, in pertinent part, provides that: “Any person:

* * * (2) who, having entered into the dwelling house,

place of business or on the premises of another person

without having been warned within six months not to do

so, and fails and refuses without good cause or excuse, to

leave immediately upon being ordered or requested to do

so by the person in possession or his agent or represen

tative, shall, on conviction, be fined not more than one

hundred dollars, or be imprisoned for not more than thirty

days.” This Act was approved by the Governor on the 16th

day of May, 1960 and took effect 30 days later, or the 15th

day of June, 1960. On August 9, 1960 at approximately

11:00 A. M. the petitioners entered the S. H. Kress & Com

pany department store in the City of Greenville and took

seats at the lunch counter in that store (R. 5). Only one

of the petitioners testified as to placing any order for serv

ice (R. 41). Four of the petitioners had no money at all

in their possession (R. 7, 8) and the one who did place

an order refused to state that any of the others had placed

an order (R. 46). It is apparent that the real purpose of

the petitioners in being in the Kress store was to put pres

sure on the manager by way of a demonstration (R. 43).

One of the Petitioners testified that this was only one of

several demonstrations in the same store and lunch counter

(R. 44). There is no evidence that any of the petitioners

had previously been served at this particular lunch counter

on any occasion. The only reasonable inference is that on

the occasion of the prior demonstrations service had been

refused them.

On the date of the commission of the offenses herein

complained of the petitioners seated themselves at a lunch

counter which had space for fifty-nine persons. The peti

tioners were advised that Negroes were not served at that

counter (R. 41). The lights were extinguished and G. W.

West, the manager of the store, requested that everyone

leave (R. 19). All the white people who had been present

left pursuant to this request, leaving behind the petitioners

herein (R. 20). The petitioners did not leave and after a

wait of approximately five minutes (R. 20), they were ar

rested and charged with violation of the trespass after

notice statute which has been referred to. Their convictions

subsequently were reviewed by the Supreme Court of South

Carolina and from the decision of that Court sustaining

the convictions, they petition this Court for a Writ of

Certiorari.

ARGUMENT

I

The Petitioners were not deprived of the due process

of law and equal protection of the laws secured to them by

the Fourteenth Amendment in their trial and conviction

for trespass.

The real issue in this case is whether or not a land-

owner has a right by virtue of his property ownership to

say who may and who may not come upon or remain upon

his premises. We reach the question left open in Garner v.

Louisiana, 368 U. S. 157, 164 and footnote 11, the question

“whether or not a private property owner and proprietor

of a private establishment has the right to serve only those

whom he chooses and to refuse to serve those whom he

desires not to serve for whatever reason he may deter

mine.”

The S. H. Kress & Company operates a variety or

junior department store in the City of Greenville. In the

4 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent

building housing the store there have been set up some fif

teen to twenty departments, including a lunch counter.

In these departments are sold approximately ten thousand

items (K. 21, 22). The decision as to what items are to be

offered for sale is the result of a business judgment, made

by a trained and experienced management. These decisions

are made with the calculated business purpose in view of

earning a profit. Some items sold are offered because there

is an existing demand for them. As to other items the man

agement seeks to create a demand by display and advertis

ing. It has no monopoly and no one is required to buy any

thing from it. Nor is S. H. Kress & Company a public util

ity. It was not required to obtain a certificate of public

convenience before opening the doors of its store in Green

ville. It requires the consent of no one if it desires to close

its doors and move away. The only license it is dependent

upon is the continued good will of the buying public. No

one can complain if its clerks are obnoxious, or if it refuses

to sell certain items or insists on selling certain others.

Likewise, a private business such as the S. H. Kress

& Company may regulate its opening and closing hours for

daily business. Whether as lessee or as owner in fee simple,

the private proprietor has the right to exclude everyone

when the store is closed. His dominion over the premises

is absolute.

Thus it will be seen that the proprietor has two rights

in the situation presented in the case at bar. He has the

right to do business with whom he pleases, and he has the

right to control and possession of the premises whereon he

conducts his business.

The right to select business clients.

The necessary parties to any private business selling

transaction are a willing buyer and a willing seller. If one

of the parties is unwilling, no measure of willingness on

Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent 5

6 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent

the other side can make up the deficiency and force the

sale. No law compels either party to go through with the

transaction. The general rule of the common law, which is

in effect in South Carolina, is that properietors of private

enterprises are under no obligation to serve without dis

crimination all who seek service, but on the contrary enjoy

an absolute power to serve whom they please. This was

expressly held below to be the law of South Carolina, there

being no statute to the contrary. (Petitioners’ appendix,

9a.) The right of a proprietor, other than an innkeeper or

common carrier, to do business with whom he pleases, and

to refuse to do business with others, for any reason, or

for no reason at all, has been consistently and uniformly

held by the courts of this country, in the absence of legisla

tion to the contrary. Annotation, 1 A. L. R. (2d) 1165.

The refusal of a proprietor to do business with any prospec

tive customer can be based on the rankest of discrimination,

either of race, color or creed, or on some whim unreason

able or even fanciful. As was said in State v. Clyburn,

247 N. C. 455, 101 S. E. (2d) 295:

“ The right of an operator of a private enterprise

to select the clientile he will serve and to make such

selection based on color, if he so desires, has been re

peatedly recognized by the appellate courts of this na

tion. Madden v. Queens County Jockey Club, 269 N. Y.

249, 72 N. E. (2d) 697, 1 A. L. R. (2d) 1160; Terrell

Wells Swimming Pool v. Rodriguez, Tex. Civ. App.

182 S. W. (2d) 824; Booker v. Grand Rapids Medical

College, 156 Mich. 95, 120 N. W. 589, 24 L. R. A., NS

447: Younger v. Judah, 111 Mo. 303, 19 S. W. 1109,

16 L. R. A. 558; Goff v. Savage, 122 Wash 194, 210

P. 374; DeLaYsla v. Publix Theatres Corporation, 82

Utah 598, 26 P. (2d) 818; Brown v. Meyer Sanitary

Milk Co., 150 Kan. 931, 96 P. (2d) 651; Horn v. Illinois

Cent. R. Co., 327 111. App. 498, 64 N. E. (2d) 574; Cole

man v. Middlestaff, 147 Cal. App. (2d) Supp. 833, 305

P. (2d) 1020; Fletcher v. Coney Island, 100 Ohio App.

Peterson et at, Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent 7

259, 136 N. E. (2d) 344; Alpcmgh v. Wolverton, 184

Va. 943, 36 S. E. (2d) 906.”

Mr. Justice Holmes recognized the principle in Ter

minal Taxicab Co. v. Kutz, 241 TJ. S. 252, 256, where he

said:

“ It is true that all business, and for the matter of

that, every life in all its details, has a public aspect,

some bearing on the welfare of the community in which

it is passed. But, however it may have been in earlier

days as to the common callings, it is assumed in our

time that an invitation to the public'to buy does not

necessarily entail an obligation to sell. It is assumed

that an ordinary shopkeeper may refuse his wares arbi

trarily to a customer whom he dislikes * *

The refusal of a restaurateur to serve a prospective

patron because of his color has been held in several recent

decisions to deprive a Negro of none of the rights, privi

leges or immunities secured to a citizen by the Constitution

of the United States, and protected from the infringement

by the Civil Bights Act, Title 42, United States Code, Sec

tion 1983. Williams v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268

F. (2d) 845 (4th Cir.) ; Slack v. Atlantic White Tower

System, Inc., 181 F. Supp. 124 (D. C. Md.), affd., 284 F.

(2d) 746 (4th Cir.). In the Williams v. Howard Johnson’s

case the Fourth Circuit Court held there was a distinction

between activities that are required by the state and those

which are carried out by voluntary choice and without com

pulsion by the people of a state in accordance with their

own desires and social practices. The latter, it was held,

deprived no one of any civil rights. That permissible area

of voluntary selection of customers is what is presented by

the facts of the instant case. The manager of the store tes

tified that the practice of serving only white persons was

in conformity with a policy of the company to follow local

customs. The policy was made at the company’s head

quarters, and was obviously dictated by business reasons.

(R. 22, 23, 25.) 1

Since the manager of Kress’ store was acting for it

enforcing its voluntarily imposed policy, he had an absolute

right to refuse to serve the petitioners herein.

Indeed, in the Civil Rights Cases, 109 TJ. S. 3, this

Court held unconstitutional the section of the Civil Rights

Act of 1875 providing that all persons within the jurisdic

tion of the United States should be entitled to the full and

equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, fa

cilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances, theaters

and other places of public amusement, with penalty for one

who denied same to a citizen. One of the vices in the statute

was that it laid down rules for the conduct of individuals

in society towards each other, and imposed sanctions for

the enforcement of those rules, without referring in any

manner to any supposed action of the state or its author

ities. The person supposedly injured, it was said, would

be left to his state remedy. And in the instant case, as we

have stated, the common law is in effect and gives no right

to the petitioners or anyone else to be served without the

consent of the restaurateur or proprietor of a business.

The Court has continued to recognize that individuals

have the right in their purely private day to day dealings

to associate and discriminate as they see fit, for whatever

reason is to their own minds satisfactory. The court spe

cifically stated in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1:

‘ It is equally clear that the ordinance of the City of Greenville

requiring segregation in eating places (R. 56, 57) had no bearing on

the instant case. The validity of this ordinance has never been tested.

It is clear, however, that if it is unconstitutional, any action taken

pursuant to its mandate would be personal, and taken at the risk of

personal liability on the part of the person so acting. Gross v. Rice,

71 Maine 241; Sumner v. Beeler, 50 Ind. 341; Meyers v. Anderson,

238 U. S. 368. The police captain who made the arrests testified he did

not have the ordinance in mind (R. 10) ; in fact he was of the opinion

it had been superseded (R. 17), and was not then in effect.

8 Peterson et a l, Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent

“ Since the decision of this Court in the Civil Rights

cases, . . . the principle has become embedded in

our constitutional law that the action inhibited by the

first section of the Fourteenth amendment is only such

action as may fairly be said to be that of the States.

That Amendment erects no shield against merely pri

vate conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful.”

Similarly, in Boynton v. Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, this

Court held that a bus station restaurant was required to

serve all who sought service without discrimination, under

the Interstate Commerce Act, where the restaurant was an

integral part of a bus company’s interstate transportation

service. The Court made this reservation:

“We are not holding that every time a bus stops

at a wholly independent roadside restaurant the Inter

state Commerce Act requires that restaurant service

be supplied in harmony with the provisions of that act.”

The instant case falls squarely within the reservation.

The S. H. Kress & Company in Greenville, South Carolina,

provides only a local restaurant service. Its facilities are

not connected to or with any business affected with a public

interest. As a purely private business venture, it is and

was legally entitled to refuse service to the petitioners

herein.

The right to exclusive possession of business premises.

Ownership of real estate, whether a fee simple, a life

estate, or a term for years is basically a right to its posses

sion. From the right of possession follows the right of the

owner to make whatever use of the premises that suits his

fancy. Anyone who enters without his permission is a tres

passer. The civil action for damages for trespass quare

clausum fregit is founded on plaintiff’s possession, and it

is for injury to that possession that damages are awarded.

Grimhe v. Brandon, 1 Nott & McCord 356 (10 S. C. Law );

Lyles v. Fellers, 138 S. C. 31, 136 S. E. 18.

Peterson et a l, Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent 9

10 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent

It has always been the law that a person in possession

is entitled to maintain that possession, even by force if

necessary.

“ A man who attempts to force himself into an

other’s dwelling, or who, being in the dwelling by in

vitation or license refuses to leave when the owner

makes that demand, is a trespasser, and the law per

mits the owner to use as much force, even to the taking

of his life, as may be reasonably necessary to prevent

the obtrusion or to accomplish the explusion.” State

v. Bradley, 126 S. C. 528, 120 S. E. 248.

Of course, away from the dwelling, the right to kill

in ejecting a trespasser does not exist. Still, it is the law

of South Carolina that any person in the rightful pos

session of land may approach any person wrongfully there

on, and order him to leave or quit the land, and in the event

of a refusal to do so, may use such force as may be neces

sary to eject such trespasser. State v. Bodie, 33 S. C. 117,

11 S. E. 624; State v. Williams, 76 S. C. 135, 56 S. E. 783;

Shramek v. Walker, 152 S. C. 88, 149 S. E. 331. In ejecting

such trespassers gentle force must be used, State v. Brooks,

79 S. C. 144, 60 S. E. 518.

The policy of the law does not favor the use of force

and firearms by persons in possession of land who seek

to remove trespassers. The charge in State v. Lightsey, 43

S. C. 114, 20 S. E. 975 expresses it thus:

“But I charge you a man has no right to take his

gun and run a man off his place. That is simply taking

the law into his own hands.”

As a substitute for the strong armed ejectment by the

person in possession, the law of this state has for many

years provided a calm judicial mode of ejectment, employ

ing the more even temperaments of impartial law enforce

ment officers and judges. Thus the law has provided for

many years that malicious injury to real property should

be a misdemeanor. Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952,

Section 16-382. Since 1S66 our State has made entry on

lands of another after notice prohibiting such entry a mis

demeanor. Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952, Section

16-386. It has never been suggested that these laws were

intended other than for the protection and preservation of

property rights. The opinions of our Court in South Caro

lina have strongly intimated that a person in possession

of property should not take the law in his own hands in

removing trespassers, but on the contrary they are exhorted

to seek the aid and protection of the courts, by prosecuting

the trespasser for these misdemeanors. State v. Lightsey,

supra.

It may be objected that the statutory law of South

Carolina until 1960 provided only for prosecutions for entry

after notice. But the court in State v. Bradley, supra, indi

cated otherwise. There, quoting State v. Lightsey, supra,

the court said that if a man warns another off his place,

and that man comes on it, or refuses to leave, he is guilty

of a crime, a misdemeanor, and for that misdemeanor he

may be tried in court. The 1960 Act, under which petitioners

were tried and convicted, adds nothing to the substance

of the existing law. It merely clarifies and provides ex

pressly for the misdemeanor of trespass by one who refuses

to leave on being requested to do so. 1+ made positive what

the court had held in State v. Bradley, supra, was impliedly

a part of the law prohibiting entry after notice.

With respect to country and farm lands, no one may

enter them without permission. With respect to a store

building, or business premises, the proprietor or operator

expects and invites prospective customers to enter. This

is a sort of permission which renders the original entry

rightful and not a trespass. Business invitees are often

spoken of as licensees, license being nothing more than a

mere grant of permission. Ordinarily it is implied from

Peterson et a l, Petitioners, v. City oe Greenville, Respondent 11

the opening of the doors of a business establishment. Such

a license is always revocable, and when revoked the licensee

becomes a trespasser if he does not immediately depart.

In the annotation, 9 A. L. R. 379, it is put as follows:

“ It seems to be well settled that although the gen

eral public have an implied license to enter a retail

store, the proprietor is at liberty to revoke this license

at any time as to any individual, and to eject such in

dividual from the store if he refuses to leave when

requested to do so.”

In BrooJcside-Pratt Mining Co. v. Booth, 211 Ala. 268,

100 So. 240, the Court held that the proprietor of a

store would not be liable for damages for assault and bat

tery in ejecting a prospective patron from his store, when

he did not desire to transact business with the person, and

he had notified him to leave but was met with a refusal to

do so, after giving him a reasonable time in which to depart.

The petitioners in this ease found themselves in the

identical situation. The manager of the store revoked their

license or privilege to be there, and directed them to leave.

(R. 19, 20.) After five minutes had passed, the petitioners

still had not moved, although other persons originally

present had departed when requested to leave. (R. 20.)

At the end of that interval, the S. H. Kress & Company

had a right to remove the petitioners by force. It is not

contended that the petitioners were not given a reasonable

time in which to depart, and the finding of the courts below

on that element of the offense is conclusive. But our law

does not favor persons in possession of property taking

the law into their hands to eject trespassers. State v. Brad

ley, supra; State v. Lightsey, supra. The law made the

conduct of the petitioners a misdemeanor. The law favors

their removal by the forces of law and trial by the orderly

processes of a court of justice.

12 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent

The only purpose of the law in this case is to protect

the rights of the owners or those in lawful control of private

property. It protects the right of the person in possession

to forbid entrance to those he is unwilling to receive and

to exclude them if, having entered, he sees fit to command

them to leave. Hall v. Commonwealth, 188 Va. 72, 49 S.

E. (2d) 369, app. dismissed, 335 U. S. 875, Reh. den. 335

U. S. 912. As Mr. Justice Black said in Martin v. City of

Strothers, 319 U. S. 141:

“ Traditionally the American law punishes persons

who enter onto the property of another after having

been warned by the owner to keep off.”

Of course, the police officers had a right and a duty to ar

rest for the misdemeanor committed in their presence.

The petitioners contend that their arrest and trial by

the city police and in the city court was state action which

deprived them of Fourteenth Amendment rights. There is

no inference that the law involved or the other trespass

laws have been applied to Negroes as a class or to these

petitioners to the exclusion of other offenders. Certainly

they were not deprived of any rights in being removed

from the Kress store, a place where they had no right to

remain under the law, after being requested to leave.

Granted the right of a proprietor to choose his customers

and to eject trespassers, it can hardly be the law, as peti

tioners contend, that the proprietor may use such force

as he and his employees possess, but may not call on a

peace officer to protect his rights. Griffin v. Collins, 187 F.

Supp. 149 (D. C. M d.); Henderson v. Trailways Bus Com

pany, 194 F. Supp. 423 (E. D. Va.). A right which cannot

be protected and enforced through the judicial machinery

is a non-existent right.

In this there is no conflict with any prior decisions of

this Court. The cases cited by petitioners all involve state

Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent 13

action on state owned or operated premises, state-furnished

services, and common carriers. None of them involve purely

private action taken in respect of property rights to private

property. We submit that the only constitutional right in

volved in this case is the right of a property owner to the

free and untrammelled use of his premises in whatever

manner he sees fit.

II

The decision of Supreme Court of South Carolina is in

accord with the decision of this Court securing the right of

freedom of speech under the Fourteenth Amendment.

A. The conviction of petitioners of trespass after their

refusal to move from a lunch counter in a private store did

not interfere with their freedom of speech.

When the petitioners use the term “ freedom of ex

pression” we assume they have in mind freedom of speech,

which is protected from abridgment by Congress by the

First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Since 1925, the First Amendment freedom of speech has

been regarded as an aspect of “ liberty” which under the

Fourteenth Amendment the States are prohibited from tak

ing away without due process of law. Gitlow v. New York,

268 U. S. 652; Fiske v. Kmsas, 274 U. S. 380.

Freedom to expound one’s views and distribute infor

mation to every citizen wherever he desires to receive it

is clearly vital to the preservation of a free society. Martin

v. Struthers, 319 U. S. 141. This freedom gives the right to

the person who would speak to try and convince others of

the correctness of his ideas and opinions. The title to streets

and parks has immemorially been held in trust for the use

of the public, and time out of mind have been used for

purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between,

citizens, and discussing public questions. The streets are

natural and proper places for the dissemination of infor

14 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent

mation and opinion. Schneider v. State, 308 U. S. 147;

Hague v. C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496; Thornhill v. Alabama, 310

IT. S. 88. Even where the streets and parks are privately

owned, as in company towns, citizens have a right to go

upon them to communicate information, unimpeded by tres

pass statutes. Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501; Tucker

v. Texas, 326 U. S. 517. Even freedom of speech on the

public streets is subject to some control. Saia v. New York,

334 IT. S. 558. In Beauharnais v. Illinois, 343 IT. S. 250, this

Court held that a person expressing his honest convictions

on the streets could be prosecuted under a state group libel

statute.

When we leave the streets, and consider the right to

freedom of speech on private property, we find that the

courts have unanimously held that the right of freedom

of speech must yield to the property right of the landowner

to eject trespassers. In Hall v. Commonwealth, 118 Va.

72, 49 S. E. (2d) 369; app. dism. 335 U. S. 875; reh. den.

335 U. S. 912, the conviction of a member of a religious

sect for trespass under a statute similar to the one here

was upheld. The right of the individual to freedom of speech

had to yield, it was held, to the property rights of the owner

of an apartment building and its tenants. There was no

right for anyone, over their objection, to insist on using

the inner hallways to distribute their views and informa

tion. The refusal of those persons to depart after being

requested to do so, was held to justify their conviction for

trespass. The court stated that inner hallways of apart

ment houses were not to be regarded in the same light as

public roads; they emphatically do not constitute places of

public assembly, or for communicating thoughts one to

another, or for the discussion of public questions. The First

Amendment has never been held to inhibit action by indi

viduals in respect to their property. Watchtower Bible &

Tract Society v. Metropolitan Life Insurance Compaivy,

Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent 15

279 N. Y. 339, 79 N. E. (2d) 433; Commonwealth v. Richard

son, 313 Mass. 632, 48 N. E. (2d) 678. The petitioners in

this case had the right to express their opinions on the

streets. They had the privilege to enter the Kress store in

Greenville. But, when they refused to leave on being re

quested to do so, they no longer had a right to give vent

to their thoughts on the premises of the Kress store. They

cannot complaint of their conviction for trespass where

they insisted on remaining in a place they had no right to

be. They cannot be permitted to arm themselves with an

acceptable principle, such as freedom of speech, and pro

ceed to use it as an iron standard to smooth their path

by crushing the rights of others to the possession of their

property. Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U. S. 622.

The petitioners cite a number of labor relations and

particularly picketing cases. Undoubtedly peaceful picket

ing may be carried out on the public streets and sidewalks.

Picketers have the right to publicize their dispute under

the First Amendment. What is protected in picketing is

the liberty to discuss publicly and truthfully all matters of

public concern. Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 TJ. S. 88. The

important thing about picketing is that it is used to inform

members of the public of the existing state of affairs. Its

purpose is not to inform the employer; assumedly he knows

of the dispute, and at least one side of the argument. In

the instant case the petitioners were not attempting to pass

on information to the public. They were attempting by

demonstration and coercion to force a private person to

make a use of his property not in accord with his desires.

Here there was no gentle persuasion. Nor was the S. H.

Kress & Company the proper object of their instruction.

A private person cannot be forced, on his own property,

to listen to the arguments of anyone, whether he agrees

with the sentiments expressed or not. Martin v. Struthers,

supra. Even the listener on the street can turn away. A

16 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Eespondent

listener on his own land should not be required to retreat,

he should be able to require the speaker to turn away, and

prosecute him for trespass if he does not.

Peaceful picketing, even when conducted on the streets,

is not absolutely protected by the First Amendment. Picket

ing cannot be used in connection with a conspiracy to re

strain trade, to prevent union drivers from crossing picket

lines. Giboney v. Empire Storage d Ice Co., 336 U. S. 490.

Nor is picketing lawful where it interferes with the free

ingress and egress of customers into a place of business.

Teamsters Union v. Hamke, 339 U. S. 470. The conduct of

the petitioners in this case, if it can be analogized to picket

ing, was unlawful. They sought not to appeal to the reason

of the public. They sought rather to obstruct the business

of S. H. Kress & Company by squatting on its property and

refusing to move. They sought to prevent its doing business

with others unless it did business with them, by taking

steps to effectively prevent the entrance of others. Their

conduct clearly exceeded the bounds of freedom of speech

and of peaceful picketing. They were properly arrested

and convicted of trespassing.

B. The petitioners were not denied freedom of speech

in being convicted under a trespass statute which does not

expressly require proof that the person ordering them to

leave establish his authority at the time of making the

request.

The petitioners moved in the trial court for dismissal

of the warrants on the ground they were indefinite and un

certain. The facts of the case show otherwise. They were

arrested in the act of committing the offense charged, they

refused the manager’s request to leave after the lunch coun

ter had been closed and the lights extinguished. There could

have been no doubt in their minds as to what they were

charged with. Warrants drawn such as the ones in the in

Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent 17

stant case have been passed on before and held sufficient.

In State v. Hallback, 40 S. C. 28, 18 S. E. 919, the warrant

was held sufficiently certain which alleged “that Jerry Hall-

back did commit a trespass after notice.” Of like effect is

State v. Tenney, 58 S. C. 215, 36 S. E. 555. The petitioners’

attorneys realized they were being charged with trespass.

(E. 2.) And from the warrant they had a citation to the

law, with particulars as to the date, time and place of the

arrest. And it is noteworthy of comment that the petitioners

did not make a motion to make the charge more definite

and certain, which they had a right to do.

The petitioners claim that the statute is unconstitu

tional because it does not expressly require the landowner

or person in possession to identify himself. The statute

necessarily means that the person forbidding a person to

remain in the premises of another shall be the person in

possession, or his agent or representative, and that is an

essential element of the offense to be proved by the State

beyond a reasonable doubt. The manager of the store tes

tified positively that he was the manager and that he re

quested the petitioners to leave. (E. 19.) The only one of

the petitioners to testify at the trial knew Mr. West was

the manager as she had spoken to him over the telephone

before (E. 43), and she recognized him at the store at

the time of the demonstration (E. 42, 47).

If the person ordering them out had no such authority,

that would be a defense, to be proved in Court. But here

the evidence supports the inference that the petitioners

knew that the person who ordered them to leave had au

thority to do so. They did not question his authority. They

did not so much as ask his name, so they could later inves

tigate the extent of his authority. The petitioners knew

they were not authorized and they could presume that any

one who undertook to exercise control over the premises

was lawfully in control.

18 Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City of Greenville, Respondent

The cases cited by petitioners are not relevant here at

all. They require scienter in cases involving matters of

opinion based on value judgments. The authority of the

person ordering them to leave the S. H. Kress Company

store does not involve such a judgment. It cannot be con

tended that petitioners should be entitled to spar with the

person in possession requiring proof of authority to their

satisfaction. Could they require a landowner to produce

his deed, or a lessee his lease? Can they argue with him

over the extent of his implied authority and all the nice

technicalities of the law of agency? We submit that the

authority of the person in possession is apparent from his

direction to another to leave the premises, that he cannot

be required to prove his authority to the satisfaction of

the trespasser there or anywhere, except in a court when

he is tried for the trespass. The petitioners never ques

tioned the authority of the manager and his authority hav

ing been proved in court beyond a reasonable doubt, they

should not now be heard to complain.

Peterson et al., Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent 19

20 Peterson et a l, Petitioners, v. City op Greenville, Respondent

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the respondent submits that

Section 16-388 of the Code of Laws of South Carolina, 1952,

as applied to the petitioners, presents no question what

ever in conflict with the Fourteenth and First Amendments

to the Constitution of the United States, or the decisions

of this Court, and that the petition for Writ of Certiorari

in this case should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

THOMAS A. WOFFORD,

THEODORE A. SNYDER, JR.,

200 Masonic Temple,

Greenville, South Carolina,

W. H. ARNOLD,

City Attorney,

Lawyers Building,

Greenville, South Carolina,

H. F. PARTEE,

Assistant City Attorney,

Greenville, South Carolina,

Attorneys for Respondent.