Bozeman/Wilder News Clippings; Memo; Testimony of Bozeman; Recollections of the Interview with Judge Junkin, Fayette; Correspondence from Braden to SOC Executive Committee; Selma March Articles (Redacted)

Press

October 30, 1982

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Bozeman/Wilder News Clippings; Memo; Testimony of Bozeman; Recollections of the Interview with Judge Junkin, Fayette; Correspondence from Braden to SOC Executive Committee; Selma March Articles (Redacted), 1982. 05d00509-03c2-ee11-9079-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/220936d3-22a3-457f-b65b-53211b96dc3d/bozemanwilder-news-clippings-memo-testimony-of-bozeman-recollections-of-the-interview-with-judge-junkin-fayette-correspondence-from-braden-to-soc-executive-committee-selma-march-articles-redacted. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

tl' Vifiiffion Clarence B' Hanson Jr'

puOtiiffitO-tcls Chairman oI the Board

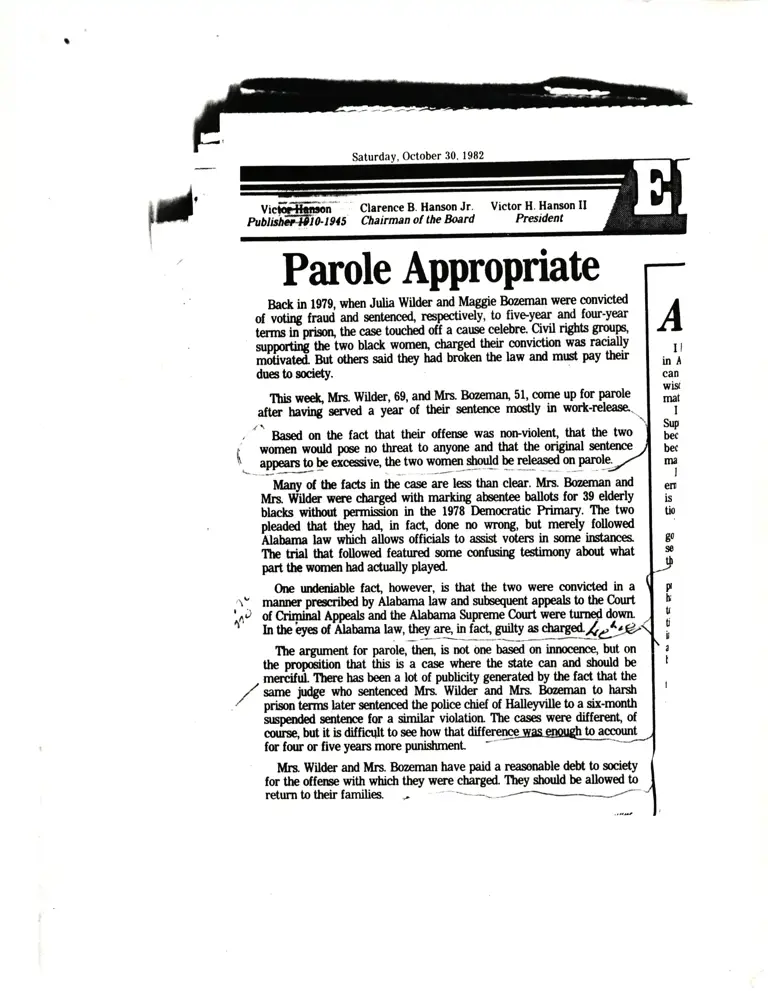

Parole ApproPriate

Back in 19?9, when Julia wilder and Maggie Bozeman were convicted

of vCing trarni u,O sentcnce4 respectively' to- fiveycar.4.f*-Vot

t;rmsd,,,'\ the case touctred ofl a carce celebre Civil riSbts 8ryPps'

;;i;rtir[ th.-t*o Uta* wonrcr\ charged their convic{ion was racially

,n&rtnfl g|It ottrcrs said ttEy naA Urofen the law ard mrd pay tlreir

dues to smiety.

ltis weel, I\lrs. Wilder, 69, and lrlrs Bnzernaq 5l,.come up for pamle

Victor H. Hanson lI

President

A

II

int

can

wig

rnat

I

srry

bec

bec

ma

I

en

is

q

g0

s0

v!

a

t,

i

a

t

I

|\

,{"

.fG" h"tir,ti g,veO a yiar of their senterrce modly in wort'rcleasa....

Based on the fact that tlEir offerse was mnviolent, that tle two

wonlen world poee no t}reat to anyone and tttat the original sent€nct

appears to be eicessive the two wunen stroulS be released onprcle,-t

Irlany o( tb facts in the cas are less than clear. lrlrs Bo€man and

Mrs. Wild€r were drarged wittr marking absentce ballots fo 39 eldenly

blacks without pernrision in the 1978 Democratic Primary. firc two

pleaded Utat thi,y haq in fact, done m wmng, but merely followed

Alabema law rryhidr allows officials tro assi$ voters in some fudanes.

Tte trial that followed featured sme oonfwirU tdirnony abod what

part t.h womeo had actually played

One undelriable fact however, is that the two were convicted in a

mailrer prmibed by Alabama law and subsequent appeals to Ury trnt

d Crirpiiral Appeals and tbe Alabama Suprenre Cuut wcre turrd dourn

h t ;6,es ;'ftaba*a ili ggpmrlgg@

Ilre argument for parole, theq is not one based on ittttc€nce, but on

the profrtion that [his is a case u,here the s:tate can ard shottld be

m€dffd" ltere has been a lot of nrblici$ genenated by the fact that the

same judge rryho sentmctd Mrs. Wilder and lt'Irs. Bmernan !o ttarstt

primnierrns lahn sentcnced the police drief of Halleyville to a.six-nnnth

luspended sttse for a similar vigla6gl fire cases were differenl of

course, but it is dilfioilt t,o see how that

for four or five yeam Inore punishment

Il{rs. Wilder and Mrs. Bozernan have paid a rea$nable debt tro siety

for ttrc offerce with whidl ttrey were cbarged l}ey shmld be allowed to

return to their families.

to acoount

MONDAY, NOVEMBER 1, 1982

I

l1

ll

u

OI

D

8B

DJ

13

,mu

ureu

Bozemaftt Vi ld,er

want to get back

to'glrry land,,

48cl

deq

fiuo

|DFe

{aldt

! ellql

lapl9

t,uaru

uapF

il ral

ES

-O) af.,.! I

lq..t Y.

l.o i{ .a

.t t$s

l*qtft

i0 *at'

C q.t ril

.* oal

ror qlp qr

b*t{'f

.a! s.ttt

trll.1.1

-ror'rt

r.a.t tq-,.

t"

t

,F ?.i 13

rmrr{.

ct r.l I

ir-.|

lrr.f .l'

ror"6

-. ,ri

roee !

-

:,n

g'

/

rt

ql

rt uol

, pltotr

qtcl

pollll

Jo'

utc I

0Bl

uq

BlillTilll'rXl", H:rr"_[,JI#TrTft ?,e iljffi I

TU-SKEGEE - Maggie Bozeman

Right Act was approved.

and JuUa Wlldc,

il#ifti$t"ry":ffi ftli,;.;"l::.:l} .=* : Ithey hope it,n#iir"iffo"'lij,,Xtj;: Mondav

/ ;IilJ,'.l,,',* nf #nfthfl Iheilinsr*,,,"-,r,"*J,"tfli"3dfiTl:)ll*t:ir*-"dil-d;;H;Jli'o:, jr,

f#::;*d&5^:r,T"1*hfl ,,fr lr:il1,'*";?fir,lTil:",;ff (;,

LHJ-,, ll,,lfffi: countv

-

sr,J'iir

l r#:n"':" :i *:^l^":T'' J' "llii" \

. The two ,roni"n w_ere convicr"6

,"r;^'llXill:ili,:r":flffi,,,tJd,x: grast year in picrens.c;i,tilii',"il eyi;f ;Fi;!!?HTSe tried to infrqud, and botb receivea il;; 3ii: in,

They served ll .deys in Jutia --Tlr:t** sheand Mrs. Wilder I]|fi,:l["ft B:;;:J.

roi' *#"i'li have- sond-tr,'e-.!r,'Jr,,ridn,t dis-

,;

#t'JffTjt tfetl.:,""i_] ;fJ[ii,,::liT:J:it :i:;[iFdil il

( il:'*';J"';, ';ili:',,,xil

":::i1]! I -rX'3#:'";lijlTHaboul a, those\-3

ir*H;,n'**ir,ll'*f 1;5.1$3i,,g,.ip*ffi*tfitrlf

$ffi:*:*,urTffilhrtrq*r'ffifi

l'iltii.i,TffiX,*-,#,nr),'f S*i'.#*}*+1-Ilif;[if Xtr

"

#',#*l .w,n**i \;ff#frfff+;;;:

/$

-,*d[;r11ffir?:';rfftr ;i*;i:,fl"itf*"m*X

16

ffiri*t-N}id#m'#$*ffffi/ff

ffidf,-::I';','"'d"t f $f,,$:.n1$tlii*,'ffi I ff

I

I

Itlrrr Wmare$ aa4.Ies' WW u vu*-relus h nskqp

lVomenserving terms on vote

fraud charges are up for parole

ByffiSllct

t{fl,sstaftwlls

TUSI(EGEE - ho Ptcheu ComtY womeo

who were sentsrced in Jamrry to tedrB d fou

and five years oo vote fratd'charges cottld be

goitry home Nov. 8 if Uey rn 3rlnted pamlc

Mmday.

Ms& Bmaq 51, rd JuIr mb, 70, mre

s€nterd ln January to t€lu d fon and fiVe

y€ars, nspectively, hrt tE JDd oly tl d8y8 u!

ixrm bdae bdng s€d to lQr o a sPecial

wctr&eprogrut.

While Uacoo Comty has bm a "$oqy"' for

them t[e pagt l0 montls, tbey rey, both look

.forrard !o returning h@ U tlcy ale peroled

Mday.

"I've eniryed being here ln lblegee," Mrs.

Wilder saf, ':hil yqt hr, [eldr m place [fe

honm. sby, I was bom rod nhd ia Pideas

Conty. yo tnor if I get prLi f! rm to go

hone"

The txo have bst in n*jn & Jan 22,

when they were released frut l\tMlcr Prison

fa Wqm ad s€lt to n$4e h tb ctCody

of Maccr Conty Sh€ri$ Ltdu Arm.

Ib two etrn€n had be.n cwictld of ma*fug

aheote ballob for 39 elderly Urcf! rithCIrt thir

p€rrnirxim in tlr 19?8 Demmrlc trhry.

IIrc two have deoied guilt

The convictions were appralcd aod upbeld by

the Alabama Suptme Colrt tb US $preme

Cort r€fused to hear theilt

Mrs. Wild€r lus spent E Utr at tb Soiurr

Ccrter wcting with s€oh dtirttu" Illrr. Bernan,

a t€rcher, is a$igrd to the Mu Oqdy Mcntal

Ilealth 0entcr, whesb tach(rafiIB wi[r learr

ing disabilities.

'Tuh4ee has b6 a ghy fc rtr,'safi IUrs.

Bmnan, sitting Lr her snall dswn in a white

frann hiHing m Chaffi Jam tltn, o the ott-

sldrts of this mdly black city of Um0.

"Itank God fm fri€n& and tnank God fr my

pareaE, who had seven cbihea," & said. "ltly

family has helped me thrug[ this. And when

tlry wercat h€re, tlre hrrc beca hi.n& frur

tlre dludg"

She put lrr hands on ber fre, erclainhg, "And

th mail Yot woHn't beliern it h day I thi*

we gd rnae than S00letters I havtnt bad titrE to

r€ad thn all l@re frun allowrtbwcH"P

On the wdl is a flctre d Jdtr f. K.onsdy

tlrere arc pders with the narm d h shdeG

- Jams, Rob€rt Ifeuv - ad a Hadboard.

MR.S. WnDER, a spry waoaD *b wears rhe

rimrred glases, is tlrc life d tb sia citiua'

grup that meeb my day at tb SoJonm Oenter,

said San&a Cathorq a shtdedatllntego Idihrt€'

wb is int€ilritr8 asa scial rqt€r.

"If yor'tt feeling dmu," the sald, "5tou'don't

stay that ray for lm& lft& With tep erery-Hyr+-*tsrtebhF*-

brightsts their day."

TlEn sh aslrcd, "Does $e have to go back to

Mrny have vbwod ttrreir $ft iD llaoo Gdy

a8 an "erilC'fiun Pi*ens

They bave traveled to different placts in the

stab,but mt totheir harncunty.

Almd lrom the Inflneitt they were whisked

frorn Pllclu Conty to the ftMl€r PrbfrL offi-

ciab bqan wcting o a special rese program

fr thern

Cror. Fob Janp and him Canmissiomn Jo

Hopper m€t with blaA lead€rs sri as Je Ree(.

ctairnan d th Alabama Dansatic Cmfetqrce

and Jobnny Ford. tlE rna!,or of l\degee As a

r€srlt, he wtrma wem barely poo€ssd hto tbe'

prison syslem before being turood oyer to the

Macqr Conty str6iff.

SorrE civil rryhts and wcrm's grup havr pro

clainred tlrc two heminec their sattming in Jan

ury toucned df a 160-mih marchrnotorcade fmm

Canolltoo to ttlmtgourry and lahr lrcn nskege

toWashlngte.

UJRII{G TIIE SUIIIME& Dntch natimal televi-

sln aircd a lGminute segnmt m the twq and Up

Arrriean Enbassy in Arderdam was smamped

witn pde$ lefi€rs ad caUsr said a ryhcunan fc

tb$atc@rtrmr

Tte di$rict atforry for Pidem Coutty, P.It[.

Johrdm, maintaLrcd that the two areguilty.

"I sspect that they'll be parde(" he sald. "And

it won't do any good for me to ralse hell abort

ssnething l can't do anythLg abo[

'&rt I already have god infonnatio that Mrs.

Bwnan played a role in tbe reuil primary ekc.

tktrs, by payrng poll watdrers.

'To me that's a little lurd to uffistard. Ihm's a

penon uppced to be a stale prism and sading

mcry to pay people her€. I fut srppoee it's a

violatiorl but it seerns strange."

Pk*€iB Connty Sih€riff Lode C. Ohman said

he wu mt surprised at the paflle Itearing.

"I figured they'd be getting out before long,"

he said 'Violat€rs haw all th ri$ts. Gmd people

dan't have any."

Cirqrit Judge Clatu Junkin, who presided at

the tdals' said he had m cururrent m tln psi-

bb pamles

WHm{ fiIEY lint arrived in Ttskqee in Jarr

ury, the w(xlEn lrygp essigned tro live h a hailer

m the edge of town, hrt latcr.tEy woe perrnified

to liwin a private horn

'"lVe can't say anotgh abort tle people here,"

said Mrs. Bmrnan- "Im grateful ttat there are

elected dfrciah who arc aware of he problens of

blad folts Tte shgitr and his $aff have been m

gmd to trs

i'They don't flout their power and authority.

fud the mayor o[ T\skege, hb staff, th couits

cil, how good 0rirw been to us lte}/rn Ueated

me lile a little.schml girl."

She smiled- "Ald when you get feling doryDr

dy ftrn tb rH, c th urr*y r

the East€rn Star calls to ctnen yor up. Ycr haie to

srnile sometime llrereirasn't bst tinp to hate If

I

)

I

I

I

l

!

uDeca-

rd 0E

ufb

v

qpdty

Ill Nov.

[IlE 6e'qL

l-*

t'ffi

ffi

'.vq

tt

dd

r tbe

ilin

oulc

nate

r tb.

hui-r-

r fcr

C

o

v,

in

!co

lt

o

o

otc\

Ea

T

-

luaplsald alHAr pli)tlE

,'Parole corfbrol lrom pr3c I

AltltoA In. Bccurea rtf tf(

: l}*ggJ!-q,t'.*qe"|ru ttutlrl fc thc borr{,r rcto

rnd tq ticr rho rcfaO-fc Orlimno'r lTxdgg, to *turd Olt,

!tt," $e added.

_ F.l- melnteiocd that rhe wrt

S*#t' ' tho Youo&-ir;;

- "A pcrson who has becn erey

1lT. Fmc thir emqut of , Urni

rlG.Drd. ! Dd uG trut O.fr oitlolr figb.

_ .lt - thratrul, but ;o err tll

?I!1T:gr rltit utr lnomd,,, irrep. .'r lp t0U r covlct, ,iUr f

fll,rlp.ioaoeent fnom rhc dey tr

! ltrtttcFd. oo me 8Dd I ln-dn;

rould.hrvc to F heppy,,,ril dt:

._IIID3. ttre Mondey percle hcrr-

ff'"f;f,ffiHil,i#i*.H

F"il'#;ql*Higd,.,Iffi

._Sh.:"{ l.tGr thst she. rer ..yery

filfiffitr#ilHHtr

'(EGO. - .

zl-flataen,^-. --r q,r

thc dey lttlr

Glot Dtr,,':hc aetd.'--Il!. Wttggr rerA tne nerr of hcr

lU tF_qq. r!.p-!, th" ,rat ,aiy,",l?Hfi#j*ir;n;'Ei

_ "fteal lr i tot of ruhlcthr lc

_ ry. W[der reid the nerr of hcr

1tj* r.g:rU_.,m.tc me rpl e UtUc

|;H:H,111.-"*r1hjrii;E;rt tio urtrtlior "d6:

p.tlc. D rt.nt lot -r-'ifiI; :{qfrtHly;,H,ilH**lat b mc,', thc ldd.

n)

Board paroles

Pickens pair

By DANNY LEWts

Advcr{rer Stoft Wriler

Two Pickens County women con-

victed of voting fraud and briefly

imprirooed in January could return

to tbelr homes next week following

the state parole board's unanimoui

vote Monday to parole them.

Ite thrce,member Board of par-

99* "rnl

Paroles voted to parole

Meggle Bozeman, Sl, and Julia Wil-

$cr, ?0, lolloring a brief public hear-

uu.

Slr people attended the hearing to

asl the boerd to grant paroles to-the

txo- tomon, who have been on a

r.orl-release program in Tuskegee

rince they were released Jan. 22

Irom Julia Tutwiler prison for Wtrnr-

en in tVetumpka.

. Tbc tro were arrested rn Novem_

bcr- lt?t rrd charged with fraudulentatl illegal voting in connec,tion with

tIe. msrllng of 19 absentee votes

wtutout- -gaining the approval of

elderly blacks whonr they assisterl

.

Thq two black w<lmen were con-

yicld 9f voring fraud Uy a[-wtriie

June3 in separate pickens Countv

trials.

fire case was the subject of a

lrTH of appeats, inctuOing an eitrl io have the U.S. Supremt Court

review it.

- Following the Supreme Court,s re-Iusat to consider the case, Mrs.

uozeman and Mrs. Wilder were sen_

tenr:ed Jan. ll to lour-year and five-

year terms, respectively.

They served ll days in Tutwrler

Prison before being placed on the

work release programs after blaek

legislators met with Gov. Fob James

to ask him to help the two women.

...Pickens . County Circuit Judge(llatus Junkin, who tried the case"s.

and Distriet Attorney p.M. John-

ston, who prosecuted them, have

previou.sly said they would not object

to paroling the two women.

. While in T\skegee, Mrs Witder

has served as an aide at a senior

citizens' nutrition site and Mrs

Bozeman as a teaeher at a mental

retardation r:enter.

The convictions anrl rurprisonmenl

ot the two sparked a natronal outcry

1nd qrgmnte{ a t?{a1. r.ivit righti

march from Carrollton to Vontgim_

ery last winter

Followrng the parole boarrl.s ac-tron board members sard lrlrs Wil-

dt.r wrll be lree to return to l)ickens

Oounty on Mondal, and that Mri-

liozeman also can ieturn by Munar.v

rl a suitable job is located iu, f,". Uj,

then.

Mrs. Bozeman is required to have

a J()b as une of the conditions of herpatole. Mrs. Wilder wilt not be :e-r;uired to work because she is re_

rrred, according to Board Chairman

r.aron [ambert.

JULIA WILDER

MAGGIE BOZEMAN

See PAROI.E, page l

,l

- f @' -+ a r'$. F6r\ [.'- e F, I ..* I 'i

IL. q.rjs -./'.!J t "a"*.lry'.*r'G-*-,.,i

Trrr'r '\l.rir,rrn.l \\r\nrcn nr.l\'!o to []:ison ir:.i .rrtu.rrr [,r'f.li,rs,)

of thtir \\()rk t() hclp [3l.rck citi,,r'rts rt'gistcr.tnd voir. in rtrrll

Pisl.cns CL)ur'ltv.

Tht'y' .rrc Juli.r \\'iltlc'r, 69, prcsicicrrt of thc Picl.t'rts Counn'

Votcrs Lcague and ,n rillicer of thc local SCLC, and i\laggie

Bozcnrarr, 5 l, presidr'rrt of tlrc locai N"\ACP.

l\ls. \\'ildtr and i\ls. Bozcmln, rrho livc in Alicr'lille, Ala.,

were arrr"'str'd in Novr-'nrber,'l 978. Thr'technical ch.rrge agJinst

tlrcnr is "rotr' [rrud." \!'hlt. thc\'\r!'rc actuall\,doirtg rvas help-

in,: cldcrlr \'()tL'rs un!j!rstand thc' blllot and vote.

AN ALL.WHTTE

'URY

CONVTCTS

Tl..e)'w.-rc convictcd by an all-rvhite jury in 1979. i\1s.

Wildr'r rvJS se-ntc'nccd to five vcars, ,rnd l!ls. Bozernan to four

yr'ars. Nls. Bozernan u'as also fircd from the teaching job she

had hcld 27 years.

Thc convictions \!ei'c appealcd to the Alabama Cou!'t of

Criminrl Appclls, uhich uphcid ihenr, and to the Alabama

Suprenrc' Court, rvhich rJfuled to review. ln November of this

ye:ir, thc U.S. Suprcme Court rclusrd to hear the cases. Their

lawl'er, Soicmon Seay of Nlontgomcry. moved ftlr suspension

of sentences, anci a hcaring was set for Dccember 'l

.

FRIENDS FILL THE COURTROOI\I

lVhen the day for the hearing came, the courtroom in Car-

rollton, Ala., the Pickens County sca!, was packed rvith sup-

porters of the wornen. Circuit Judge Clatus Junkin postponed

the hearing until January I l. l-lowever, local observers dcubt

that he is planning to suspend the sentcnces.

pickens county, *n,.; lr.r";,1*.r, o, Birmingham near

the Mississippi line, is 40 pcrcent Black. lt has no Black elected

officials except mayors of tirr1, all-Black towns. lvls.

"Vilder

ano

Ms. Bozcmans arc life-long residcnts of the area and have iong

been active against injusiicc.

.MY WAKING.UP PERIOD'

"1968 was my waking-up period," i\ls. Wilder has said. "We

were trying to get Black cashiers hircd at Piggly-Wiggly. We

had a march, rnd l3 oi us wcnt to iail. I was thc oldost."

Ms. Bozcman dcscribcs what was happening in 1978: "We

had a big rc,{istration urivc. and Black candicl.rtc', running for

officc. The pr>litie i.rns wcrc cspcci.rill, afrlid of the young wo-

man wc ran lor Schut-rl Bolrtl .tg.tinst a white bankcr. As it

tunrL'd out, shc only lost ol l06 votc5, too."

As p.rrt ot' the carnp.rigrr, Votcrs Lc.rguc mcrnl:crs went to

thc humcs of housc-tround cldcrly citizcns, took abrentcc

..! L. ".-.. ' -'- *

l\laggie Bozeman and Julia Wilder

ballots, and if necessan' helped those who could not read or

write iill them out - all perfectly legal, according to Atlorner'

Seay, if the voters wishes were follorved.

ARRESTED ON ELECTION.EVE

lvls. Wilder and N1s. Bozeman rvere charged with "fraud" in

connection rvith 39 of those ballots. The oifenscs wcrc aileged

to have occurred in the primary run-off. Officials waited until

the day before the general election to make the arrests.

'They picked me uD at school -- lust as lwas coming in

from the playground with my kids," says l\1s. Bozcnran.

"There were fir.e police cars - like I was r criminal."

At the trials, the state subpoenaed many rrf the elderly

voters. According to Attorney Seay, all but one of them testi-

fied on cross-examination that thev knew exactly what they

were doing and that the ballots were rnarked as they wished.

ELDERLY VOTERS WITHSTAND PRESSURE

"One womon testified that she didn't know what the voting

was all about," Seay reported. "The State Court of Appeals

said the evidence was'confusing'irut the tcstin'lony of that

one woman was sufficient for the .jury to convict."

Courtroom pressure on the elderly voters was intense. One

of them, Lou Sommerville, 95, reccntly dcscribcd it:

'The lawyer said to me, didn't Ms. Bozernan comc to mv

housc and try to make me lct her fix up my bailot. lt w.rsn't

ll-n, I f,sf..*. A,.r.'Li-,!jr.+ ?

Utz,r t..tt-J Jo.tJlrr r.r ol-'

, ,.j t

"d

:

t:

S

e

(continucd on othcr !rdc)

fil:h:fi'la t','."J;;'i :: ;t [::r : :

F.^- !, !-,r-l.-- ls!*r-. -.^

[-r.lr \;.li iJ-ii'o..; i r-r)

(corrtinucd I'rorrr otlrr'r siclc)

true. So I told him l'rn the Lord'schild,and tht-'Lord doc'sn't

wirnt a lie'. I r;rid I h,trr'to tcll thc trulll. Nrr nllltLlr itou'ntltry

tinrc's thcy' ask mc, I'll kccp tcllirlg, thr' truih."

A PATTERN OF HARASSI\IENT

Thc ch.rrgcs ag.iinst 11s. \\'ilclcr lnd [1:. B(rrt'nlin ,lre not en

isolated incident. Just last year, a young BIac[: man in Pickcns

County, !Villic Davis, was chargcd with disordcrly conduct for

explaining the ballot to votcrs.

When l\1s. Bozeman picked up abscntec ballots that year,

she said the sheriff said to her: "You'rc gctting some more of

them. Maggie Bozeman will gct them to vote if she has to vote

them herself. Wc're going to 8et you this timc'."

ADDING INSULT TO lN'URY

At the time of the wontcn's Decembcr hcaring, local district

attorney P.M. Johnston told the news media in Birmingham :

"They could have been arrestcd on othcr chlrgcs sincc their

conviction. Their efforts at the polls havc corrtinu,-'d. Thcl'

aren't satisfied with voting themselves. They have been bring'

ing people into the polling placcs, watching them vote, insist-

ing that they be allowed to assist people."

lmmediately after December l,local officials added insult

to iniury. They sent Ms. Wilder and !ls. Bozeman lettcrs ielling

them their owl, names had bcen removed from the voting rolls

because the conviction was upheld.

BUT THEY WON'T GIVE UP

But the two women aren't giving up. "No matter how

rough it gets, l'm going to be here," lvls. Wilder said recently.

Ms. Bozeman, in addition to continuing voter registration and

cducation work, constantly app('ars beforc locrl qo\('rr'rlrl{

bodic's -- Citv Cttuncil, Crtuht\/Cotrtnrissirln. Bo.tr.l tlt [-.ilri.i'

tiJn - to protcst r'.trious torms of discrinrinatitlrr.

Anrong thosr' sho cJmr' to Pic[r'ns CounN' to :upp-'er1 ;1,.'

wonrcn at the tinlc of the Deccnrber I hc.rring wcrr.' Si.rcl.

elr"'cIr'ri otliciais t'rom l0 surrounding count.i!'s, Alabarn.t Dr'-

mocratic Conference Chairman .f oe Reed, NAACP southeast-

ern dirc'ctor Earl T. Shinhoster, SCLC leaders President .f ost'ph

Lowery, Rev. John Nettles, Rev. R.B. Cottonreader; repre-

sL'ntatives of the Federation of Southern Co-ops, Alrb.rma

Hungc'r Coalition, the Equal Rights Congress, the SouthL'rn

Organizing Committee, and other groups.

SCLC CALLS FOR NEW REGISTRAT]ON DRIVE

Thcre is a legend that the face of a Black man lynchcd in

Pickens County after the Civil War can be seen in the w'indou'

of the courthouse in Carrollton. After the Dec'

.1

court st'ssion,

Dr. Lowerv told those who had g.lthered:

'These two women were politically lynched. We came here

to be on their side. We are going to launch the biggest votc'r-

registration drive ever seen in Pickens County. "

You can express your opinion of this situation by wriling

Judge Ciatus Junkin, Pickens County Courthous':, Carrolltoir,

AL35447. JudY Hond & Anne Brcden

ir:!

,'l::"::"t;ty

HOW YOU CAN HELP STOP THIS INJUSTICE

Obviously, Judge Clatus Junkin needs to hear from many, many people, telling him that

the cases of Ms. Bozeman and Ms. Wilder are a disgrace to Alabama and the nation and that

he should set aside the convictions. Write your own letter, and urge organizations to write.

You can help financially too. Victims in cases like this are too often crushed economical'

ly even if they escape jail. Ms. Wilder's financial situation has not changed greatly since the

arrests, because she is an elderly widow living on a small pension. But Ms. Bozeman has had

no regutar income since she was fired from her teaching job of 27 years. The National Edu-

cation Association helped for a while, but that has run out. You can help her survive while

she fights by sending her a contribution at Box T, Aliceville, AL35/,42.

And this case points up dramaticalty the need to get the Voting Rights Act renewal

through the U.S. Senate, unamended. lf Deep South officials are harassing voting'rigltts

workers with the Act in effect, one can imagine the consequences if it is not renewed or is

weakened. Contact your senators and build support for the Act in your community.

Thlr rrticlc epPorr.d originally, in condenred form, in Sottth(rn l:lqhthuck,

nawtlctter ol rhc Sourhern Organiring Committo. lor Economic & Socirl Ju(icr (SOCI

copior ol thit llier mry be ordered lrom soc, P.o. Bor 811, Birmingham, AL 352O1,

or P,O. Box 11308. Louisvillc, KY 40211.

Tot!- ,

:'',

,lrii'

t

U,is4

...i

"Ther raised rhose iss':ls in ihe Ccuit of

Crimtr:il A::eals. the Alabarna Su;:e:::e

Courr and tii U.S. Suorerne Court arci aur

ooirticn was upheltl"'sard the Clstric"

Ittorn.t. "So I m satisfied the case ts

sound."

Seav. a )lonrgomeri' a'-torne:r, acnilted

11igsg !rere 'tt'chntcal errors" tn lhe '*av

ii" Urtto,. xere hancled. but said tire

wo:'nei hrd no criminal tntent'

::ii at.* out of thcrr \r()rliinq wtli aqed

anC in:irm Persons and asststi:( :nen l'o

cast ti'terr absentee baiiot:s." he s'aid'

"There were some technical errors rn

the wav rhel' handled the appllcaiiolls'

which ih rn1,' ;udgmcnt drd not a:'11'iu0t to

frauC.' tre

-sa:0. "ln rnv .ludgrncnt, there

$'as nu crtnlt:ral lnten!."

St'a1' said be belie"es the pr'.rs(cu.tl')n'

,r,i, li.t of ln cf f url to '* caktn

"Ic

blick..

vuttng bl(x tn the cuuntv'

.l, rn [i<i t-r i * ,i- *-

li \a' LV/' H Li qp'\=/ il .'

!

''TL.,:r' se€l:1s to re in c{f rr: io :'c::rr'

\ c,i lia. he saio.

ScJ;.' satd lhe '.rorntr do not btl' :

itl p:u.on.

'I

to

Con vicfed of vof e fre ad

Two \A/osmem Hil

['l:l'-'{ l'rr':: lr';

C.\RIIOLLT(l\ - T*'o blaci: wor:ren

mav go to prison todas for rote fraud,

but'their atlornc!'saic thel' bad no cil:ri-

nal intent - just a Cesire to resls'.er

blacks to vote.

Julia \tilCer. ?0. and }laggie Bozeman.

in her late i0s. both oi Alicevrile, ser€

convicted last 1'ear of vote fiaud !n the

casting of 39 abscntee votes aliegedly cast

illegally.

T'he iwo have been sentenced to fcur'

vear srison ierms. but Picse;s Coun"v

Cireuii Judae Cle:-tus Junkin is expetted

tc rule toda-v cn a motion the)' be granted

oroba tton.' District Attornev P.\1. "Pep" Jchr.stcn

seid there urs nothing unusuai about t::e

case. despite charges the prosc"cu''ion of

the women was ao altempl to kecp blacks

from the ballot box.

"They rlere eonvieted of marking, the

Uallots, having them noiorized fraudu'

i;it 6]' sonneine rvho did not kno*' rhe

,ot"it, ind rhen returnlng the bailo"s"' he

said.

Johnston said there is no attempt tn

Pi"kont County to kecp black voters lrr:m

F.t\J

"lt '.rould eerurnlv be a:: injus:ict

put :itL'!'n in prison," he said. "Lt:

assu:le thit rqhal ihe:; Cld qls'*rc:q i

u-.e f act ts ',iie!' cio wlia! lheS trrlugr," ::

had :he riglit to do."

Johostoo said he opposes Proba:

bc<ause he trieC unsuccessfulil' for :

:,'ears to reach an agrternent "that *'

La','e pt.t'ented'.heir golsg to prlsoll ''

akb. he said. their efforls at thrl rr

have conttnued since thelr conviction'

, "Thev aren't satisiled $ith ''"otinq l::

.'seives.': he said. aCCing that tht"' c''

have been ;rrrested on other charqcs st:

LLe convtctton.

''"Th..,

have bc'en brinqinA people r:

tte p,:i'lrr:; plaees. $atc;il;lB thcrn r'

insist:ng tiev be ;riloxc"d to assi:t p''"'l:'

he said. "\\'e've avoiled r:taktl{:'

arres:s. just so !he rmclicatrrrn oI r:"

iii.rf ..tn"" won't bc rntcndcd.''

Piciiens Cbuntr Adr.erriser . fhursdal. December 3. tgEl

(jrt'cnc ('r'trnlics lrrrrl hr tliqlritancs

ol'thc N..\A('p and SCLC. Orcr lu()

[t(r,l)lc h;rtl {.ltllr,ri.(l ill l,]t,etrtlrlr,'(',ll trf tht, ('.rr t,,llf,,n

(','rr111,,,,,r" trv lhc trrnc tht. hcurirrrl

h('tiut. neilfl\. an lt,,rrr Lrtt..

.(.'irt.uit .lutlqc ('latur .lunLrn mct

rr ith [)isrrirr An,,1n1,1. p. l\1.

.L'lrn s t on a nd t hc tlcl c n rll nt s.

GremQff, Wilder sppeols de n6d

h_v l)oug Snnders Jr.

_

-l

ht. [.'.S. Srrpr,,nre (i,un ,,n 11,ru.l6 rl,:r:rr-.ri rlre appcal of Mrs.

1l.a1.ri,.J. fl,r(nrar and Julia R.

Wilrl, r. Iury ,lliccville women

convirtr.tl ll volr. frau<l in pickcns

(i'unrv ( ir,.rrit ( ou6 in 1979. Aprr,Ix1i,,n l:t.arinr firr the pair was

begun Monday and continued until

Jan. I l.

.llt,zs61np anrl Wildcr u,crc indict-

c<l bv lhc I)ick,..ns (i,un11.6r.,,,,1

Jurv in l97tt. Wildr.,r

"r, ,ri"J i,,

J;rnulrri-, I979. and Ihrzcnran u,ts

[rit'tl in Novcrnhcr. 1979. Ilr,tf; p.,,r..

cltarqerl wilh lhrt,t. coulrts ol. volirrrl

frarrrl in crrnnectiln with .1,)

fraurlulcnl brllrt,,1ln1 rverc votcri in

a-

.

Sr:ptcnrbcr. lg78 Dcnrocratic

Printarv runolf irr Pickcns Gruntv.

Wildcr u as \t,trtcnce(l Io lj1.a ,,a.r..

in prisln: [},zcrnun n,,.; tir,",i li,ur

l',Cllrs.

^.lI'zt'ntrn is pt.esitlt.rrt of tht

Aliecvillc.( ur.rr'lllorr Ilrurrt.h ol. lhc

ry41('1,. lrrtl Wil<lcr is a lctrlcr ,rf

lltt' Pickcns (',,urrtv Brarrch ol. thc

5('LC. 'l ht'ir l)ti,h1111111 ircarinq uas

:tllcttrlt'tl [rr'. lt l;rrqc qrrrur ()f

\tlpJrorlcr\ lnr111 t,ir.ki,ns and

his ruline un(il a latcr dare. Further

lestimonr u.orrld not bc offered bv

eithcr Br,zcntan or \Vildcr.

ln lhe counr,rt,nt, Seav frrrmallv

prcscnted his rcqucst to Judg'

Junkin. Junkin said he u.r,uld rule

on lhe two's requcst for probation

on Jan. ll.

Appeols denied

(Continred frou page t\

all()rn('vs. Solonrtrn Scav Jr. and .1.

L. ('hcstnuft. in a pre.rrial

confar,'r',aa for ahortt .15 minutes

Mondlv nrorning. Ae cording t,r

.lo[1s1q111. the two altorncvs asked

thc judec for tintc to prescnt other

alternatives to the court and to defer

. PICKENS COUNTY HERALD, Thure., December 3, lgEl

f. I

In Bo z enr an, Vil d er cose

4h-

(*t*:::Tx",:,'i:.I*

J.rdge dclirys rulingtilJan. tl

A date ofJanuary ll, 1982

has been set by pickens

County Circuit Judge Clatus

Junkin to rule on an

application for probation in

the cases of the State of

Alabama versus Maggie

Bozeman and the State of

Alabama versus Julia

Wilder.

ton, Mrs. Bozeman's and

Mrs. Wilder's attorney,

Solomon Seay of Montgo-

mery, told Judge Junkin he

would like to have more time

to present other alternatives

to the court and asked the

court to defer the rulings. He

also said he declined to offer

testimony.

On November t6, the

United States Supreme Court

denied the appeal of Mrs.

Bozeman and Mrs. Wilder.

who have both been

convicted of casting 39

fradulent ballots in the

election of 1978.

In Circuit Court in 1979,

both ladies were ried and

Mrs. Bozeman was sentenc-

ed to four years and Mrs.

Wilder to five years, with

their sentence appeated.

Nearly 200 spectators were

on hand in the courtroom

Tuesday morning when the

ruling date was delayed.

.|,.

-ij-.-.*'

.,1*rr.a_

6604

Camp

Temp'le Hi l'l Road

Springs, Maryland 20748

December 4' l98l

Mr. Pau'l Hancock

Deputy Section Chief

Voting Rights Section

Civil Rights Division

United Slates Department of Justice

Washingtor, D. C.20530

Dear Mr. Hancock:

This letter is being sent to you on behalf of Maggie-Bozemal., ryil1ie Davis, and

Julia l|Iilder ot nt.ideville, Aiabami. It is my uiiier that their civ'i1 rights

have been violated OV otfliials of Pickens County,.Alabamar , in addition' my

lnformation inaicitei potentiai;'iotations of tnl voting Rights Act'in eiections

held in IgTg and iggo in pickens county and probable harrassment of these three

inaiviauals and

-otfrer

Black c'it'izens attempting to regi ster and vote'

Pickens county, acccrding to my information, has never had a Black e'lected

official and, I believe, had no Black deputy registrars 'in 'its, 1978 and

.|980

elections despite repeated requeiti frorn'th; loaai branch of the NAACP' In

assisting elderiy, illiterate_c'itizens to vote 'in a runoff election in 1978

U,;;-nii nave Utin'p.oi.Outii violations in carrying completed absentee

ballots to a Bli.[ n6ti.v pubi'ic in Tuscaloosa, outside Pickens countv, for

notarization, uui.-t i* conrtnceci from reao'ing-the transcripts in the Bozeman

and Wilder cases that any errors l'rere those 6t iuagment rather.than intent'

and cornmitted in tn. fac! of continuing noncoop-raiion by local election of-

ficials, and tfrit'any Jirect viotation was that of the notary pubiic' who

n6taiii"a the balloti in the absence of the signers.

In l,lrs. Bozeman,s case, the transcrint i1d]cates her presence in a group of

four or tfve peopl.,-Uut no inaiiit:on that she vras a spokesperson or carried

the ballots for !ig"uiri.. It'is my understanding that Mrs' Bozeman was not

ln fact at that iigning, because-sni was teaching and in schoo'l that day'

Unfortunate)y, no diosi-examinuiion chajlenged the notary's statements nor

were any witnesses presented for the defense. In addition, my reading of the

i"intiiipi inai.ate! no dtrect connection and no presenc-e by Mrs' Bozeman

,i.ii-ir,.'uailoti-weie signed in the testirnony ot each of the nine witnesses

(of 39 challenged ballots) in the case'

Desplte thiS, Mrs. Bozeman was sentenced to four years on a felony conviction

by the a1_whitl-jriv.- ttis. iriiaer and Mr. Davis rvere sentenced to five years

cach, and charg.r"*"i" dropped ;;;i";l-".fourth defendant. 0n appeal, we had

understood the Alabama Supreme C6r"i would overturn Mrs' Bozeman's conviction'

but certiorari was oenied and no-opportunity for further presentation was

aval I abl e.

2.

As you know, the united States supreme court also denied cert' in the last two

ueeks. At a hearing on Tuesday,-61rl""u."-r,.,:uage claytus Junkin postponed

l,lrs. Bozeman's

jlilriti." untt l-: ;;;;lng .oura ue-nerd" on Januarv '11

' I982' In

the meantime, d.oniid".uble nurnber of itat..nd national organizations have

become involr.A ii"i.;ki;g'io aeiend the three individuals'

The civir Rights Division has.-received compraints about erection violations in

prckens county in rhe past. r,r"il-gii"min ino lirs. I,rirder are orominent civil

rlghts leaders in the county'q;; iiiiu*tntt nu'"'aiieg-e-qlv been made bv prin-

crpars in the.ir"-iiui-th;ii inient is to get them "oif'the streets" in re-

taliation ro" tnui.-i"ia.iinip ii'giuaiuiiv=rdring tn" countv into compiiance

;iih-;Gte and ieaetui nondiscriminat'ion laws'

t have also enclosed copies of.three documents for your consideration' The

frrst is the testimony of Haggi"'boi."un before in.-House Judiciary Subcomnittee

on civir and coriiiirtionar nighti.--Tl" second'is an article bv Representatlve

Henry Hyde of iii;;;;; iiiine her testimony. The third is a notarized state-

rEnt by a proteiio"-oi Law a[ th; U;iversiiy of Aiabama reoortino on attempts

to serve a warrant on a deout-r'ri..iii-oi iicr.ens corntv *ho becine v'iolent

after another pioi.iio" took a;;;il;; it-!ir.tak'ins pictures of Black voters'

rt is my beiief ihat the eventr-"upo.tud ployia"-jritification for intervention

by the civ.ii Rights Division ,uitn-."r0".t'both to"ine aileged violations of *'he

ybttns Rishrs eli"ini'ippi"unt ,ioi;ii;;a or tne-civii Risnts Act in preventins

the exerclre oi"ionri.iiliionui ;i;hG bi citizens of Pickens countv'

SlncerelY'

"{hA"/*.-

Boyd Bosma

enclosures

cc: Haggie Bozeman

Joe Reed

Eeverly Cole

BoYd Lewis

JosePh LowerY

Anne Braden

' BobbY Doctor

Howaid Carroll

Solomon SeaY

Reo. HenrY HYde

Reb. John conYers

Jlm tlilliams

George Hairston

Earl Shinhoster

Tyrone Pi tts

Thomas Reed

Martlyn C'lement

..ry--a. r "a'

I

ai! t

\^

.

TESI'D0IIY ol"

MAGGII' BOZtr.lN

PICXENS COU}TI"i, AIAP,IT'!\

EEIDRE TIIE IIOUSE JI.IDICIAN SUKJ:i'1ITi.EE

OT

CIWL AIS g}\S].TIUTIO\AL RIGTTS

JUNE 12, 1981

I.OTIGCT.IIIRY, NA}IA"YA

t

,&3;l

:'?!: -'--n

-T

Jrn ZZ 'Bl

a'a

a.

a

a

+.-- ri#

t

I

M(. cllAllulul AI'ID r'{l}1t}tilis oilnui sul"c$sflftlili:

. r{y N,1}rE rs t*\cfifli noz-E}Iu{, AND L /$t A IllESIDllil'oi: PrcKl"l'ls q)u:{IY' AIABI}L''

I A},I PPJiS].D.1,rr Or TII' PICN,:N:S COIN,Y R]VU{T:II .V',\CP' ru{D I SrI:'J'.i AS CMRDI}IATOR Oi:

ttrt,icxrisrj corJi{n rr*oLli\Irrr a,Ni*r..iicri. r LIVri L\'.fiiri'r'i;]r orr Alrclivru'E, I!PU-

IAII.ON,3,2110.

trm IT C*lis ,i'o ilL\'K tEOI'Ui Rt(::is;I't1i':,l,rG r';'il) v.'L'll{(:, J''l'i

.trlAf AIJC[\, rrri fS A Ir]lC t+\YS lT.(-[1 iiEliVJ A 1"()]tr01''ilr^'J{)' tiili'l:Ss

T0 llEAll TllE I,IIOLE oF PILlQ'n*s (]t)tNfY II'l A Nt'lt.Af l\q'', sliNSE'

P$*SED oN T'E 19S0 ci\'US, PIcjlx}:S C,IiNrV iu\.S E,97E l]I,\Cl(S, .\]'ID 12,451 tiltT.,itrS.

BLqc,KS Ar{E 41.g% 0r riri }os,Ut,r\IlCI'r. llo.\rrwlill, 't'inl-:'rl F IiiLY li\tPlillSst\'1i NIJI'fiERS IDIi'T

uEAt{ r1}rr,r1lrr\G EEG\Lrs[ I.nt t!\in BH-:;t,] i$tABt-[, To ,,Licl' A t]L\G( 'IIl /r coljfiY\frDtr .t.'Fic]i

rN prcK^.S cotiNly. ri\oiivr'

'\lR

'rhe itori /rr-I--tlt,\ch'- t'urlis iN PrcvJil'ls couNTY (oI-D

ttna*ls./u\D II"^\tu,JJN), l{E }L\\"E t;0 R,ACK liL'Ecll:D .F':ICTTiLS TC SPI/rK OF' LI}€1f,ISI:l'

lr' lri*E FFl.r BL\*.S I,J'o Ai\n Appo*{rlti) Trf sEiRvl:r r)itr vA*.lous cilY AND coLJi{TY Bo'\Pos '

ErERy Gi/,i\cL r LL-r- *) sAy rr, r Tut-t- pLui't,i'i'tL\I'l']IcKiil{s ml}rtY tlAs No

E.AL l.jtt]i 1T CctE,, T0 Dn\YlNc BI;\CKS I.\SY AC.,Es!i To IuC].'RirIoN

^iiD

\'TI].IG.

FEGISTRATI,N.I},.\RR'I.:'LS:

rv:C!:SS1.P,]]-IrY

,In..tl* RtrC;ISll'Iu\T'I.oll SIli, i.,,oo NrrIlL)Is

oFTrs Bo,\RIrs oir REGisTRVLs Frr,:L\.Li ouri Bic(:i;s:f j'r(()Burr !i{ t'lcttiis c/)Lli[IY' rN l97E'

!E REQLTL.IED TIL\T OtiR f,o.\riD rri: Ir;cTS'r1i1.RS Ap].'orllf iy;r.il"i Ftxlr:'>-r'Il"\i''s ' THEr nAlL]'

. frzusm Al-lliolrclt 'flni [.o.uiD ',r'r)t.D l.'s o:{ s:ta.1iitu r-x:c\sioNs lll^r rliry I.DLII-D BE \'IllJ'rr]c

e II,LD

'.TER

Rricrs'*..,'i'ro)i rt'rttt't P*tcl*Las, l'Jt': lL'Ji lln:{ [:I\g['u'm clir rllll't ro

Itr[t-DiB\i. TIUS. l.tllilti iil|sIc l.JCUSli Ir)R i'iYr 161'.lrr] At': N:tl''iii vuTitll' outlljl\Cll Pllfi:i',*\l'l

IS rttr,fir' I-ricrsrA,llp€ lt\s suf ottnnTN t0i(;Ls[lu(rro]: D\Yll R)P''l1l1i\1 'lo rolu)t'l' Al"'D -

,rr\T Tlutf r.mJ, t{,o'' cfir l'..\m rutt 'tttti r}\\s liliT(:ll lL\\'ii ,.l'lu':\DY l}EE: D[srcNnTIiD ]lY IAl'l

'0

Ifl,:iu,: 1\) 'Ji,l.T. YoU

'iOU 't KE '}.l)i'iDliRl-\iiD"

a.baa

I

I' \ RAIILLY ILNI' l'IIi CO:'IIXJCTIiD A VOIL'R IiI|GLSI]U\TION IXIIVE IN PICiILNS COLNTY

!illlotltA'sNr,i.l.ul.lttntSo^\IlilulslsTl0iuilll(}lI(XnI,o[rT.CLus.otxiorTIIEl'f}sT

Al.,DyrNG I*TNGS BIA(:'( \DTriru; r cxi rN I,LCI{N' cotnlly nt rlytNc To Rr.lsr[R rs riiii

sIEADy pruisn{cE O. r][i I-AI.I L].itolrcr,'i*{1' OrrirTCIitLs. YOtl I'DULD 11lr{( TII f 'nlE DEX',U-

')

TrES ANt oN rlrE, t^yruu. olf .rl[i tiOttu oI riiiclslli'\ils 'ri{l'] I"l\Y fllliY (rx'[l AROL]ND

IO SN(u' m slji] 1'[L^1'l.,-'E'l{i rniNc'

\Jl]EsP}ODlrry:IItrPTCKLI::]Coli[IY,\UuNGl,t{oljlj.].x]^RIil..ARI.DI.ESI]/E118

. IIlA,il PI6BU:]s ol.. I].ldlI:;fli\Itoi'1. ]N l.-ALl., ll\ql:]) tll'\)}: Ntli.tili0.L:l] (i)r.ii,I.A1i{ls Ifli FIl.Ei)

l.ErIIlHIiJUsrrcEL):lxNlnrii\il'1''\-ST\L\tt'I]t\TA(ll'Jlcistlill'liDltttlJ'orsiti\trRsro

.PICKE\SCorn\iItTo}.CINi']\.)iiT}IiiELiicI'To}:S

IN I.{Y olTNlolr, PICI']I:S C,LJN,Y II\S o}n 0l: ,t.IE IDST oIJ'l.D\mI) Sf,S.]tr\E or V.IL\G

r HA\E sEL\ Iuoii{ilt'. hE srrL,, tist p.afEi{ i}\Lu.vi's. ,"DRE.'.ER, }.,R LA'cY'.or A DrrrER

,B!.i, .{E l{t'VE.,ol.,E{ I]CL]S[ VC[.IN(;,, Ii\: P].CN:]!.I:] COUNIY. I}I i.ilST rotLIt{G PIACES,

IHERE.ISNoPRI,/T\Cfliiti$CE\njlr.r0:1ti\^}.trLE,lFIWlEATT}ILAF:'r)RY,IMjStGo

,HERE AND Go To TLf;] TAIII^E

'*lICLl

llqs .nIE ,,ti.,. I.AND A]I 1]*: oIl*ir' VcIER.s

',.tl.SE

NqI.ES r.}ID IN,,I3,,}llisT l.i,\liK olni Ii\iJfItS rl ,n[:' t.lii.:sul'icli or (,I][itls, USING TIE SN.ii

TABIJ,. tOR TtlOSli IOU( 11'10 C'\'\'T lifi'rl)' Il' Til \EiiY DISCOLRTGING BECAUSE TfiESE l--\]tx

oTTEqAP..EEASILYTLFITEDCI..I:BY},.Tl]Sou.i:.SToiI.|Jt,sSDL\Cti\,oERs.

DURI\G.nE l9S0 t.LI.i;i1()NS L\Sf Fi\IJ,, I,,I.^.(;}s StrE}:I.:l).n; L{i l:u, olui o}E,S tfiio

.'FRE qtUEst.Io\ED ABotIT l,jilo I.I)I.I,D BIi 1'ii0\,TI)I}i(l

^Sslsr,\\CIj'In

\,oml,s. IN ADDITIoi:,

'IIiEstAliD\r"DsI'rJR'LsslsfrNG\o'J1it(St'i'LsGL\i\r';l:l)iiYIJ')CALotrlrcr'\ui-PE0PLE''rlic

.ERE 10 Pil,\[DIi ,r'srsr.ucE \.]tiiili RliQtl]Iu.]l)

,[I) :il,j\.:l)

^

l$.\S()}I\t{,!i. DIS].ANCT A10\Y l.RCIl

rHE rolrrG{ r,L\(L. .Ir0,i* \il.:l{li crFfrN s;rF[.Oii!it) 'l\) A.ss]sl' BY A DEPUIY SIU:lutrF Oi'l D'Jf i

n'rTlrE rou-L\(r nruri. ut l'tY clsli IN t'ru{flctll-,'Jl,.l]lE l)lfulY sllEItI'l,T'Iu3K PrflL']x's

. oE}18 IND ALL TIIIi t\,,1.1,( I- ASSlS,ii.D ]N \,{lj.lll(:. lt\};1.llIS o)i}i1'nui f*,Iit,' IIU'I,.D o.Il

sttrll?

a

a

-2-

|.a

i&.1

I

a

ABsDrfliF, r\u4rt, I}l pl${'t!s (;otNn 1l'l ll)s}t), 'lllti slu':liJ't:t:'s D[I'l''trES l'Iiilui

INSTRUC]'ED 1'o \[sIT',llili llc\flls c)F AIJ' Iil'^cl( IrAI'l]i'Tns 1'Ilo lll':QLlilslED ni]slNTlili &\LI'uls'

TI.IEl']Ilolllll,rti\I}DltND.Illl.S}[)Mi\trli,l()t)lil.l.:lii,l1tr:1iItJlIfl.:tl'i.:lr'lilU.]PiioPLIil.itloCoT

ABSENim]],\]l.tJISl.lliot,LlijlIN,I0i.]i{UNl]{IjI)\Yot:ilEII.uCfl(,'|N.

IN ADD,T,()N.l'.0't.llls, LL](,\I, l[\l!\.]SI1J.}tI.(:,ul lU:SLUt ltr04 VoITR I,,Al{tICu,iflT0}:

rN prcrGNS c.Ll*,. r c,'N Ttlst'rt'T'r'o lttir, tilic'\''l:;l': r snu;lrt'ID liDtli\lr BIACK

pEopLE REG\RDD{. l1*,r Tlniy c/N'oiTj. AN.''Jls,,:{lt'T:,.11\ufrt' BY tI],nG sc' r l*\s lr\uuli)

rNro coifi{r AID AccusriD olf I..],\L\UD, /[.fn'i(; t.Irfil i'ir$. -ItjLrA I'tT-lJ)I':ii' TItu ly]\RD o]'

EDIEATI*\ ]uLuLsED }ti o}:Cl] i!\ 1i.]I,It]Ii'.JrIi 1,-\.: }a,i.irl:l r\I}JLII (:l',\tiUls REC}'I1DING AIrSU]II',[

B'\Ur15 DIStRIllLirl 0N .

JtsT BEING A \\II.,,l{ N ,,].CiJ,,NS (loiNTY IS l. \r'i.}\]iYn.i!; I:}:I,iillliiic[. Sow-TI}cS

r rEE Lrr€ Gnr[,rc up, Btr r lsff acrri{(]. ri{DR:D, 'lllr lltrNc 111A1'KEEE'' }E G.ING rs

-ro roqol TIL\T r cA^r crLL oi{ T}pl .ltistTc{i Di:ll'Altll'i-l{1 t'Dli PJr'rnr' iI'' }LlD EE' rr

iln. t.ryr"rr\r,- I.''rr:tl:'q Ai:l"l'li(lfiicllilll tnCx'i US' \"E \{yfES. IN RLTU\L /rl"Jj-ij'r

..o.qcfiEss TN{,S T1IE \.0T1}:G lilc:llis

^i;i,t'li()fiiClli]ll

tncx.i us. \tE \{yr$LS..IN RUiu\L Alr..l-\rl

../tct

) t".,'. ''.'' i :t

I.AYASidr'fl Si RT\fiIISiLTNG.L\Ii" ' ' 'i i "l ;i

(: 't"tt' ''"'r'

,!.";;'r':",.""),.nrA?rt\r.\'\r ' t r " t 'i I t't' ,'

t"

't /

(..,,. l, ii,'' /)',-' (uri u s e ('lti /,'

l ,;. '1' 'lt/: , rrz t-i {: lt rtto t';'.. -

\

O

.,ru

t'

vASltlNCTON POST. SUND.TY. JUT,Y 26. I98T

TITE

I

I

a

llrnry t. Ilrle

Why tr Changed

rl rltll'llt

I\{y h'find on the

trtr'l .{ (foltrl:rlti;r. 'l l"' (slltll:r!

lhlrll,ill;1 ll:.ltt,' I h'lt'llitllr llt Irr' (

.,f .[.firt l,gt rtt.ttttt' w:rr ltrhl

Irrl.rl ltt tlt. :rrr1l' t,tr ('r{lr! irr il

h'.1

tottri.rtr ultrt llly lrtclcleslcc li;r rlrlxtitrttitrg

,,..r=. t, ,^,r it'il.ritl cottt! rt''iem ;rr llrt'

trrr,t$f (t)tt(l I isf l('r trrtllll riXhl' 'rllu'r t'' ,1,1,,.,, ..,,,,,,, tlp ltr"rrtrr:*. \\rtrr..r :rlkY

siltrtrr trslilit,l i.i ((trrlllltl.tr;I :rtrl 1tt'rvilttrc

,1,.s1i;1[r ul tt.t(l\' ,trr'..s l'r llru t'hr ]r'r:ll lrtr''

.\ l;,

"r'il;ff;i- tlrt .l""

11111. rvlttt h ll' rt,lr. Slrtlt t?rnl{''r u"G llli'

thrtl rlr nr:rny (tl tlr(' I'rcrl"nllrt'ttttl: lll;rrk

d,unlr(.t,rl ,il ,1t.,,ti.,. lh(r(' i: lxt lr lr lltitrl:

,. , '*" rt't ' t'lik't: vol' rr i';c ["rctrl to lrll

riltI llx'ir llrll,'ls rrtt .t l.rtrlt'. i:t lhc t'(tir'llr(:

,4 ul:rlc lr'll'$ rttl:' r" 'l lr' r(' 'r(c rl'r

lx*rtlrr, ttr r',rll.rrtr"' ll'r tlt(ltls to lrrtlrt te

lrrni(\:. Sl,(',rl',:rti.l th:ri ;r lirtt'lt'rt l:tl'c

t!lh,f.r::rir:tllr . l !\'t'rrll{ ttll(, :ltrl'rr:llt l(l'la'

l.r rllir, i,rte l'ljr( k tt'tr tt. .r:rd th tt' llls lr't-

a r rrrr-irl.'r;tlrh' tlrriritl( . lletl.

l.rr r,llr,c l',rrr.. ltr \1.,:thsr' ('r'urrt\"

,lc rr:'i-tr;ttirrr f:rtrlltv i: irl 'l ttlftll'tlrc

rl.rv.r r,ri" it:ttl trlr''t 'rl llt'ttt "'trc

l.{

rl )l

r 0's

llLll r|lnr tirrlttrtlll: (

"Il;:rrir

lr tlrls

I l,*r:.' .lrrtri.trr' ( irrrllrtli'r r": \rtlh I rrllltit(lIi'

.rr.irtl;.trl rrl,.tilrtlrrtl.tl rt::lrl'. I "tttt' l'r

lir.. r..rr. rrttlt lln' r'\lr.i\r<.rl .rillr lr'llrlr lh'll.

irrl.r.l. ll lr':lt\ ri rt' rln{!l:lt. irtl'l lh rl rl \irl'

r!. rir:i:li altrnr 1*trt'lrrl tn tlrl"trr"f'

!lr.rt rrr,fl 1., (rrltlt iu'l;rtrt lvJ" lr 'rlllrl(tr'

tr':tk'.tl trll(l('t llr':ut lt ti.tr lll\ slrr{!': trlrlr'

r,.r ll: rl lnI r'llitrltttr't' itr :tlr ;ulrtttttt'lt 'ltvf

,t,..-. aa.,. .lll llll\r.lfiallllr\l illlltrihrll ' ll tll"

i,.L'r.,; ...t.nt .l rr'lrttr ltl'rl tr|rlx'l'l' '{ rir'

-i,".,,.,u. .rrrl ttr'r'i: llr'rt 'l'rtr'' 'url l'r'rl

1r.1,r..,i qtlrltrirult' rtrrlllt rx{ t'r li'lrr"rh'rl

]- l.,.,ttr'tt rtiit.rr rtr ;ll:l'ltrxi rrl tlw lrrh'riil

!ra. r rulx'lll itr ll'.t'lrtrt(l'lt'

llikr rlttrrlirl:r tr'rrlrlrrl 1111' 6 sIl[

rlltirr lli,'r'rrl:.'l lrl':h!''nl sihll lrl llrr'

t{t.rll lslh. .ll(' lft,li *frrrl lrs lr;*"irrg

it.. t,r!.r,,1 r.rlrr..rrxl lri{lrrr1'1 l.r tlk' r'\lr"

tlttf cr. .,rrl .'l'r'll ultlrllt'tt l' lrt'r'\\ r{'h llrrrll'

-,..r,a. lrlr'r'l'.itr.ltx"' ll lrrt 'rlrrrl lrrltlrr'

tr.r,'l 11r,.1..$rl rrt lltr lurrl"i r'tI!'lrtr'

r, lll JrtJit'l\'ll.!rtrltr'llt hrtrl tt''ll t'r 1rr'

llr lr.llts,ll''

.{ll rrl lttrx' .lllrr.l.'t.lltrlrr lx'llrrl th'rtx'

t.s llritlrl lrrrltlrty l.r olx{lx' ll!'\'"u i't'

Itr. ar.trtr.r. ts .! ,i..lrr.r{ll.lrl ,.'rt7.a

r..ral.r rart' rLtr,t llltrtou.

'l still'bclic've in thc fcrlt'ral

srstent. I rt'Xre. rrtr(l resist tllc

sccr('liotr.J oi PtJ\vcr to thc

l'ederol gol't'rnnlcnt in rr-'cent

veors. Attd l't't, untl 1ct-rvhnt

good is nll thc Politir:nl

rhctoric if l'otr cn n't r'xprtliis

)-our id('ns rtrr(l vtltlca

at thc Polls?"

.r,.11,. jrrli: t'ittrrlttt.t. lt t. .t llH 1x'rrr trt lrl'rck

r,,rrttl,,tr,rr !rrl tF lrl.r L \l'r?" t'tlutot'

Il:,' ..'trtt:l.rrttt'

"t,,,i "l llli' tt llllh'ny

;'r.r'l r riil' t,'l[rrl tttl tI {'r'r't'rl crtt;r ltt'i'tttr:

. I tl ,, lt. lt nt ttr,trt" '

rrtt'ul' t'rl'[c Prr''

t:rr.-r lorv;lrl rignilt<rtlrl lr,rrlr( rl[.llilO llr lll!'

5ir:Jh'r lx,lrrre,rl 1:r,'r"' altl't l'itrr"(' 'il

Itx. Vrrtii'g l(r;1lrt' .\rt :il l:'(r:' ljr't tr'tttl'

t,lr'. .\l.rlrrt,t.t'. lrl.r.k rr'gt'rr.rtt'lt ttt llrrl

L.,. -:.t.1 ltsr(tlrl. hrrt l,\ l't"t' tt \"ts'ri'l

grrcrrtt {ln'.rtr'\t pr'r.:r'-' lr'r' lr ' rr rrl }lir'

.,..r1r1ri. ulterr rltlv lih Inrr''rrl r'l lrl'Ihr

rvrre fcgi.l,'rtrl 1., l\rlr' rrl l'x' I lnrl t'7 I 1rf'

.i.:tt $.tr. trgr'.lfrfrl lll l'r.l' lll lhe ';tttlt

lr.[il rlt.rt.. :\.nllll l';l,"ll'Lr" lr'{ l{'rrlrlt

[rt. ,rrlr*.1gl to rlt ri 1r tr r trl "'rrl "'rtr.r]

t,r..Fra r llx. lt.rtt th ' r"l i'1 " l' rrr'r't'r!' llr'

rlrtrllrt( r\ll:rttltr' l{t.l'trt"rrt l{"'tu'h' :rtul

llttttrrt':1,.'trt ltt ll,r''rl rxr'h rr: rl'tllr rl'rrv

.,..,.161 llv tlrl ilrl. llrr''r'r:r'rr l:li li'rl

lrrl.lr' ..llrrrl.: l,, l.l llr'r! 'rr'' I Ylt lrr'

rl.. rl. rr. .rrr h.rll'r.l\' rltt ll.( lll.i.lll..lal -

lrlt ttr lurtr' ntalli' t lllrlll'll' l" 'L''

. ( .atrl lrr.r1\rllr;r rL''ll.rlrL'is llrt"urt

Itrx.6l. .\lrr.l,l . l.rtttr,"l llrlh sltr' rxr rr'

l.,n l,, ,.n.rrr.' llr.rt lrl.r, I r"11',' strt' 'rlrk'

l.r ;tnr(atl rth'lr io tltr 1r'll' Nlr''rtlr'ft'"'

11,..1.. *.t. llllllllhl.lt&rlr. l lt'il'll'llllv lx''ilxl'

Irl.t k u,ttlrr u,'le ltlrtrrl 'lrr'lt 'rt tlt"trtt'

.r;rrl Ir,rtt p.ltll( llt'tllrl:: lt'. rr lrtll ln'lllrl:: "!'

li.r.rl.. (trt..-rtlt l{'tr,u. r\rrr'i'l rr'' rlL'1.

st.l. "(rl,l Lrlt. tl r.<r t.r.l'l s '. l' r'{l l l:l I

lt,.,r. r.r,, rlrrthl Ir.rrr' 'r'trrrl 'rl l:'r'rlr"'

llrlrx--r l,tl,l r.l -rc rL'trlt""'tlr'rr lrll.'

lh-r;.1rnl lo "tlrr l lrtr (l"lrrlrl''l'l lr lrl i l'

artttrltr'r qltrl( .l,ttlrt* rlttlc vt'lrrt llt' ttr'

(.xri..1Ir'1h .'.

llrlt,r'l llr.'rrtt. lrr l'l r'r'*rlrturl'r ftrr llr'

Yrr(u,r., Nr\.\l'l'..{rtllhr.l llr lr"r't "r:r!'

Itllirt l.t,xrrl,rtrr ilt rttal orurr rll Vtrgtl'

Voting Riglits Act

' IJrr l.1rh Amrtttltrrcnt. ratrtitrl in l"l?(l'

,a.rai,ir. lh.lf ''llro rt,llrtr rrl ctllrt'ttr of lltc

f,*r,..1 S,,,r,t t,, u,,t,' .lr.rll uol lt rlttturl ru

'rti,,tl.a hv 1i1g (lnitrJ Stttltr 'rr by ittty

litittc ,xt ftr;rtrtt:lt ol rih'c' c('Lr( rrr llrtrl(ltll

tlrli :lrhl 1rr"r ['.lr.'t:rr' rilltlir s 'l

-r.Lrttrl' Jr(ril\ rr: !:x (r{rlllr.. iltrl

ttl:tl xfil :rr:tirt ilr l''?.i li'tt(rrr* eh' lrrrr.

', rltr-lrt,' rte ttlrtrtl;rlt l,r t'ri.tltrtt( 'l Ylrtrl'll

lrlrrl J|:.ulht i'.{.llI lft'lll lltr' 't'1 r ,F(

1,4 -tr.nl-.*tt") rtttlrl ,\rry ti. l:N.1. lll('ltrrt Sht'rtll I'rirr' t ,\ru"!'1. rrl $rL,r (irttrl i, ",,r,,. rr.ari. ri ;rl. tttttr';tli lr rtf s'{('fr

..rr rrlll l.rkr' rl,rt' lt l\\rirr tlr' lrrtrrrrl 1l

.rrn. ,:'tl I ptrr. ('tly t'' irl'rtlrlr('ll'on '''

..,rr iu.r,r, Lx;rtt,'lr' iln l ."rllltv rc'rlrttti'

[i1.11 irar rn :tr,r'l ltct. v rlltc rlr-l ilrx c .rrs:rv:-'-ii,t,,.

Ilr't'r' r,',1 t,trrtrrtlk'. trli'-' n'a"l

rlr,rt t1,,. itr--r-.r1,t,, rh lr.r lt.t. lllc ltr[h(-l

1,.il..r.lr.rli,,rl r,l l,l.rk- 'xrt"t'lI I'l \lIr';r

.rt!l ll,:rl tir'i"rr,trlttrtrr tr'r'Ilil l "' h''rt r\lt

1.r:,ir .rr th'lrtrl ,it ltl.trtr trlti?r- tlr:rt:'r ltlv

..1 ,t.. ,,.,r1 r.ltltrrl ro rruttty ltlrt kr'" Otte

t

t

.*d

t?

frllrt,nrE

IrC grr ltrrlt ancl un dthlh lo prrtltfi tlE

ita,,| 61'3nlrr r 0l ;'trr|lt-ttxnl rvlllrrll atlu'

.r,nrl* l,*rrtra,.- lrhr -till llftd l"'rl(a lt'rll'

o Atlttrttristr.rtirc 1,r.''rlr.trltttr' lr.r'rt t'tl'

lrlr rr.ttkrxl' !rrrt rt h.t' itttltr"rt rl lt irt(\ tlr

rnini'ale,r.. lt rr,tr:.1 rrurl c\c:l l(lllr li lii{'

l..ttiltt t*tu',t t:r.c. l'.,1t of lllr' 'r( t rrt'r('

crrrrrh,r r.d.

. 'lin n, t rhe,*l\ . itl tlt,rttt tr''lra ls. lr r'' r l'

l'rr{irt. tutlrlt$ith' iqtltllr'ittn'tt lj"r 0t'tttrlrL"

rnrL'r ir'. :itr'). (\^rrt ir('trrll t'rlr lI lrrrrrllrI

:u6lrr.tr. irt tlu. c,rrtrtn. rttttl tl t'rtrr- ri'l't'

,rtitrx riu, h' sh,rqn. lll' trrtrl ('iu' trr(ilr l)rc'

cl'8tull(ll ;L{ t{r' t rl ilr rcnxrltitl ;tr'l I ll"-'-. ;llr.r"n j,rri*li(ttrrlL{ I'rt*rrll\ 11'\r'rr rl' ttl

Itt irslir.. rrirglrl t.r 1t,,.,' .11;11Ltlrh t'r ll:r'rrt :t

i*...t|"r,' rr ltr't,'ltr' l ltt't' r'itt: q tk 't ttrr L tt rcttt

iaa,,r,,q1"'1"i;rlt lr'k'ri'l'r{lrt tli{rrr Irrr^'

irugth.rr r,'i tlri'Ir:r. \r\" lrr \('rt' llt r lutr"

.rirrltlirl hrllt sill: th' L'tt.r 'ttr:l 'ltrttl .l

tlr. irrt,rrr,l ltt'tlrt' tlu hrtri:"r rir'rll lt lrrrttrrrl

Lr'l*r'.t'L',,t Ilrr'il cL'. tpn l'rs cll'lrtl:'\"l'lrlr

r.n[l nrrtglrile 11{tll'll'llltt rrltr'rr' ll lt;r' rr'

rtatnrl rlllll l't.'\hh llll rltr1'ltlllt lI rrllrl'h

rh.a. itllttr't\cttlt'rtt is sllil trrrLrl'

I rfill ir'li'v" in th,'hrlt'rrtl rr'lcrtt' I rr'

l:n't allxt trsi't llrt .lr('rl'l r 'll\ ril lr'rrr r lrt t hr:

f.ak't,,1 g,,*.tntttr'lrt lh'rt l:;lvo tlrrtrt'<i rtl

fntlrt fe,rrr I wJllt i,r tlrl'lre llll llu* ul

rrrlt', arlxl nslrrt',lttlttt lr'h k lr' lr'''rl l "r'

i..,uu ur.. :t. I lr lIt'rl' tllt tc tr 't l'"rl rl rlr:r'r

i, ,,a.r.,.ir,r. tlx' .rrtlx'rrtt ril tlle lr<L'r'rl

Grtr.t.ttnx'all .nl'r .'1.'t\''1'1rr't ol uttr ltrtr'

firhl'llt?.rli(ntr I'l l{'t.t! Ir'trt' 'tl''r'rr' lrr rr

.tl.rtr1er.rt.. rthttlr'r ttl llir'ttt-'' l'rlrr "r

I.r;rnn'lll 'llrn rtr irrrlrrtll lrl! ttlttrl:'rt'

It (.4(tlllll( llt' rli lrr'l'tt\ hrt'l\ lrlc lrlr:L th

irf.l f,'t. Jltrl lcl trlr'r l.trl rllrtl ll t'

ff:i,t t,r'ar't, l"rrlh rl'rf la'r tr lrr tla r rllrt "l

ii.'.|...lt'' \\'lurl ;"'"1 r' rll llr' p'['t''rl

iir.l,tii^' .l rr{l r'irrr'l r'\ltro(t Yrilt rlt''n 'rlul

. .'ia[b.t tl,( lxtlh"t

"

''ii5

Lrrx rF ilr(, 1r.,trrtx' pl,<lgr.r,t n.rltrt

a O-lC Uf ld?tt lrV rulrlrrtrl tllt' lilh ,\rtr',rl'

ltrllt lrtrt.rttt' ttrtrrtltlttrll' tlltrl rt^ lr''

dmrlxirt ntrr't t.oow h'\l'

4r.&-- .;!.+

IE@LLECTIONS OF THE

(Present : mYself.

atrd several other

INTERVIEI.' WITII IUDGE C1AYTUS

Judge Junkin , t'r';''8Y Dobb ins 'ladies from AIiceviIl'e)

JUNKIN. FAYETTE

Maggie 6oE^r(n. Jul"{ aAi't'at

.lle trrlved at Fayette early ln the afcernoon. havlng drlven from

Gerrollton because the circuit clerk there lnformed us Chat, on orders of

JUdge Junkin (the Clrcuit Judge), gLven him thaC very oorning' no'qtarra:l'

could lssue for the arrest of an officer of the peace in that circuit

rnless lt caoe from the clrcuit Judge.hiuself. lJe expected eicher a

ehllly recePtioo' or no recePtion at all, -but' to my surprlse Judge Junkln

took.qsintohisofficeiuoediacelyuPonourarrival.Werreretherefc:

rt least an hour, causing Judge Jtmkin to fail to. begin on tiEe soEe so:i

ofprocee.dingwhichhadbeensetfor3:00.IwouldestiEEteourEiaeo:

lncenrlew aE betrreen an hour and an hour and Ewenty minutes' l'le left

. etor.nrd 3:15 P.o.

Pe.tgy-beg1n the inEerview by aski-ng the Judge to issue a warrant

for.the FayeEte f1-eutV'" -"4""".,-tellinq .h-tra :h":-we -trad

been.directed :o

blr office by the people ln carrolton. My recollection is that Jucge j":t-

klnaskedreggyEoexplaintohimjustg'hatshewastalkingabouc,and

?egIybegantorecountthedecailsaElensth.JudgeJrrrrkinconEinually

lnterrsptedher,andiEsoonbecameclearthatJudgeJunkinhadbeenve:;r

fully lnformed of the faccs from the point of view of the deputy' AE cr'e

-voluntarily

^rr^^--itr^ r!^>i^'

eorr,t'iliiiiiiiila us'EhaE the coornandanc of the Aliceville Nacional Gua:c

Aruory (the place where the incident in question took place) uas going :o '

back up the deputy's version' and that Ehe deputy's version uas thaE Peiay

uls causlng a disturbance and refused to leave.' At no tiEe did Judge J'::t-

' L1o ever appear co recognize that the version of the faccs shich had thus

Dccn senE to hiu throuSh the normal pipeline urighc be incorrect' Hc reiuse

to lccepE or cotrnrenance any fact alleged by Peggy which might contradicc

orcalllnEoquestionthestoryorcheconduccoftheAlicevilledcpucy.

---.lle repeatedry-nored rhe hotheaded.irascibility uhichPpggy had encountered'

.--.rpokcto.aomeleng,chaboutghac.r,eknerrofE,hedepuEy,spast-.offered.che

.... tffldavlts of vltnesses, and.recounted a qulte dl-fferenc. sec- of facts'

Judge.Junklnreaainedrelativelycalo.actelEPcedtododgesooefactsby

lrrryerty wordplay, and fa11e8 to ovGlly reJect et least sooe points of Pegg

.tot7tbut.heessentiallydidnotbudgefiomthedeputy.estorynor.dldhe

. Gall ua uhy thlc partlcular cvldence ualt ao perauaalve to hlo' ;1.

:

,-

f gl".. - ..t I iv.q F *r.r Jr-a.'.

I I

.\ > 1.-.1-*)a'-ti€F.i:. : !'.,'e. a i;) o tl'o 2-.{''data'';r "'' -''

t.,

' Judge Junkin dld. however. dlsplay some raEher remarkable atCltudes

and attcmpted. rlght there before our very eyes. to Place before us the

- type of whlte-folks' conununal exptanaCton ("we're really doln'the besC

r .---.16 Can. and wetre advanctn Just flne, we'll Cake CCfo Of ouf O$I , ond

I

.. - rlders IFayecte is further from Alicevllle than ls Tuscaloosa] Cellin us

. bou t,Q run Ehings") which seems typical. of the present-day rural uhite

- .ilcls.t- sentiment. in thts area. - At one-poinc-Peggy, absolutely incredulous,

utro had not lost her temper through all of Judge Junkin's antl-black'

antl-t omen '

.. antl-ltaggf;,;;;;i:oucsider, anti-integrationist. anci-college professor

low-key tirades, who had not even lost.her temper when- she.objected to

-.__Jrdqu-.Junkin's

constant i.nterrupti?1" "! lrer 1nd.JYde:-Junkin E instantl:-

_ (ln a_.louder "?i::l i.:t::=_YPt:9 l.l ::- T"]":i that- Jre -did 3oc make a habic

of lnterrupting people--Peggy said "You really believe all that, don'E youl"

. Judge Junkin did everything possible short of threaEening overt vio-

lence (and we had expected, I guess, Eore of thac sort of display chan the

] rubtle and-complex'battery o'f-socLai--a.f.n"""-tr. ""t.r"rry u.""gtt ion"'"rd)-

-.--

jf-.todeflectorcauseustoscoPPursuingourlegalremedy.Heusedthelau,

be used social argrments, he used political tacEics, he bullied us'

Ttre Judge on the one hand noted that he had been elected wich a large

"' eircrrnt of black support, and attempted to present himself as one of Ehe more

'-'forrrard-looking people in an emerging inEerracial community in the area'

'---- trytng earnestly to convince us that haroony ulas at long lasC belng esEab-

-"llehed beEween the races of Pickens county on a muEually agreeable, progres-

. ' - tlve basls. ending with the age-o1d line thaE'such progress would ineviCab-

---ly continue unless it was disturbed by nosy outsiders; uy interjection Char

-..the Fifteenth Amendment's guarantee of the vote had failed to.BeE much en-

---.forcement localIy unEil agltation began and contlnued--remaining unen-

--.forced and violated on a total basis for 90 years--drew from him not ghe

-rltghresc

in<iicagion of remorse-or-recogntEion EbaE. such lllegal cacEtcs ' -

--.produce a-lot of itt-ritl amongst-Ehe. deprlved, but only- a rePeat' of 'his --

-.Deslc

Etory EhaE things were now S,eCCtng better' He dld not think Chey were

..-. . tcttlnS better throug,h the act,.otrs of people.like Mrs Bozeoan and Mrs Wtlder,

.. .. horever. onty through che actlons of people llke Judge Junkln and che ocher

tut on the other hand the. Judge revealed na" atr"'"orot" often enough'

. Hc called l,trs Bozeman "Maggie" and Hrs lJllder "Ju118" throughout our lltay

ln hte offlce. even uhen recowrtlng his sevcral electioneerin8 cups of

. coffee at llrs Bozemanfs. house,.and'even directly after speaking to or cf

]-.frofussor Dobbins." [Hrs Bozeoan and Hrs Wilder returned the fsvor by

--referrlng to hir di=."tly or indirectly as "claytua".J lle trled to

drlve a wedge beiween us otl racist lines by informin8 us of the felony

"-"cqrvlctions of the two black ladies, convictions rrhich had occurred in hls

eourd and which (as Mrs Bozeoan instantly reminded him) were on appeal

-end'thus were neither final nor sooething fit for such judicial, biasei --'

. -'couoencary at such a ti-me: the Judge's rnessage uas clear, that good fo-kS

-- dld not believ. or "orriort

with or even atteEPt Co help convicted felor's'

.- ..f,e brought this matter uP very edrly in our inter.rriew, accordinS to Ey

.- --Dtoory, and brought it uP a couple Dore tiEes despite Mrs Bozeoan's ob;eC-

._.tlonstoitsrelevancyandtoltspropriety(asjustuentioned)..Heccr..

' -'jtantly used the tone. in talking wich PegBy' of asconi'shment that an

., '

rtl

....educatedsouthernwhiteladywouldspendsoouchtimenandplaceso=.uc3

-- trust-ln this sort of black.folks. -.After disaissing us, at 'the inEerv:=w'S

--*".-cnd,-he-caughE-and-asko.t

me t6-stay 2fgcr thp ladr'es--hadjeia-in-a-filal--'

Ittempt to discredit such folks as ltaggie Bozeman and Julia wilder' whc

.(hesaid)hadbadrePutationsasliarsandtroubleoakersinchePickens

co@unlty. (This was a clear acceEPE to drive one wedge beEween the scie

.. -by giving.the appearance irf coopting their larryer through the usual in::a-

' professional cameraderie').TheJudgewasabitnonplussedbynyPresence.IuastreaEedwiE:1

8 great deal more deference and some resPect' and was addressed (al:hou;h

.ta

roocBimes rd-.h a querulous tone of voiCe) as "lltister" or "Professor Hol:'"

^ - trthe

ftre Judge made a lengthy actemPt to pick lawyerly nits with tne ove

lcgal definition of,.assault and battery,.'3E one poinc rising unexpec:edly

(butnotthreatening}y)fromhischair.stridinglnag:reatcirclea=e.=d

Lls office, and pinching ure lightly on Ey lefc shoulder.

-i\'Ias that a

-bettery?..

he queried, as Ehou8h ge were in Crioinal

.Lau class back ag lau

-- ichool. I Ealnrained chac police officers could be guilty of battery ;ust

llkeanyoneelseiftheyactedoutsideorbeyondthescopeoftheirdut;r.

.' thrt the example he ralsed sas trtvial and obscurantistic' and that at'

'' lcest "battery" wag a ouch better &flned criminal action than uas "ouE-

I

?

I

t

. rtdb agltatlon." which the Judge had Just serlously accused Peggy of.

. Jucr 8s though 1r were a crlme on the O".n:o:j.11abama. IAC one poinc

. - the.Judge ceased talking, became visibly l6i:llEx-iix and shouted "Is t].ere

a tape recorder here? Do any of you have a taPe recorder golng?" ani upon

- .l our chorus of pegative, surprised responses conclnued "Then why is sle

.- (referrlng to Peggy, who had, not surprisingly, been interruPted in her

- . teaponse to one of his questions by this outbursC) Calking so loud?" I

....responded "Probably because she's so agitatedf', but only Mrs Bozenrn

.- .thought my Pun tas very humorous. Judge jUnkln paid.it no notice.l

...The Judge ceased playing legal word-games and returned to the aEtack.

- .. Later.he asked me whether I thought deputy sheriffs should be 1ia51e in

._..3uch uncertain and dangerous circumstances as.these. I replied that l

.....gh"ygtq that the worst 9r_iqg of_ a!1 -"a:._t!g gis.u_s.9 o_f force-and the Law.

. . by officers of the law. I referred to- the terrible exauple seE .srhen offi-

_. c:r" .srrorn to uphold the law. o.penlY a1d-hgtheadedly.v_iolate. the law, =an-

. _ .

hanfllng tl. ci-tizenry in Ehe process..

_f,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,

reeelt.ea

1n1se

sencinenEs 1:rile

the short time at the end of the session when Judge Junkin corralled =e

elone wlth him. So far as I could tell, he refused Eo accePE even the

d.,*tt

possibility thaE the^sheriff had done anything wrong, or could have tr-d,er

the "circumstances,; Judge JUnkin's only resPonse of substance thai I can

recalt Lras something like "WeIl if that's right, professor, then we'11' have

every policeman being hauled inEo court all the time for tire mosE cri'.'ial

of actlvities." It seemed to me that Judge Junkin had jusE adoiCted i.cw

llttle JusEice one might expect aE the hands of the law in his area, b:rt

I dtd not say so to his face. It rras not so ouch that Judge Junkin could

Dot recog,nize this danger to the body politic: his social posicion ltas so

precarious, in Pickens County, that he was unable to imagine anY actic:l of

e deputy's. being extisxxh}'r illegal. "La! and order" meant order.

:fhe main thrust, however. of Judge Junlcin's remarks eras aE Peggv. I

hrvc elready allucied co his conEinuous incerrupcion of.her narracive a:rd . -

.fcsponses. Judge Junkin was clearly.upset aE the appearance on che Pickens

tAil<-

tccne of a^female coll.ege professor outside agltaCor, and in oany rays he

repeatcd this message to Peggy a:rd to the resc of us.-.It was clear thar

the Judge had no ldea rhat local condltions mlght have contribuced to the

Gvent ln qucstion. Hc lald heavy blame on outelders who come lnto backvard

arcrr and dlsturb or agltate (a trord he used- over -and over) -the locals. He

. -L-

i

ti

'3u'--, €-tt:}!r:.-?.fi'.j.:.-:!f.--..-.a'.-,-i.-r:r-r-t,-oit1.*>>,?.?ln*Jf-o.ar..-t/ ' ...-r'..ear+'-

I

' lntiurated that Peggy's car and ll.censc plaEe were well known to che plckens

.uthorltles, hlntlng (although not, to ury meoory,, saying oucnlght) that

i -''Pe8gy wae carefully uatched when she vlsited Plckens county. He tteraced

i ' the polnt that college professors should scay at hooe and ceach (making thls

. pl.aces and fomenE discord. lPeggy attempted to explaln that she was.a

.trained professional sociologist, and that much of her work in pickens

County,.including the events direccly preceding the.assault upon her by

-.-. the sherlff's deputy, ttas field work and the gachering of informacion and

. -.9b.9qryations.

So far as I recall, this link becween Peggy's profession

-._-:td her- presence in Pickens County aade absolutely no impression on Ehe

Jydg": J He made it clear thac Peggy was unwelcome in Pi.ckens

-and had best

. _::I:l _her s1e9 when there,

_lh?re-h -*h"1 ].:s-ql ::I:q htr.,L.:ler. he was

\ threatening her or outright celling her not to cone back Eo pickens County

.- . l.Ot. Junkin refused to accept such an undersranaing of iis (I choughr)

. rather blunt and direct remarks. At one poinE he at.Eempted to make out '

that "agitation" lras a crime in Alabama. or atat least that is what I, a, y_ se wraqL !, d

-

latryer, goc the clear impression he was saying. rt was my impres"ion itrlt

. Judge Junkin was as uPset over Peggy's being a souEhern white woman as he

u8a over her "agitative" acci.vities, especially since peggy iteraEed her

theme that she did not want persons (white young males, specifically) like

"".thls Pickens deputy performing the function of role model for children such

-'ae Peggy's two boys, giving them the noci.on Ehat. violence and confrontation

-'$as the best way to solve difficult social dilemmas. AE another point.Judge

"'-Jtrnkln attenPted to use che old Wallacite identificacion of all college -

''- professors with godlessness, asking the deeply religious Mrs Bozeman and

-'llre lJllder whether they knew anything about Peggy's religion or belief in

--.-God.

.'Judge Junkin was clearly not a dispassionate. neucral Jurisc. He was

---(an.t oade no bones abouc it) an.-iaportant figure in.the..polici-cs of the.area,

havlng-clear ties to.and power over the officials of.Plckens Councy.-.He-was

. --.qulte.clearly a functioning, imporcant part of the local poeer sEructure.

. .r-.f,e.uas.a Part of those rrho "ran" Pickens (and perhaps ocher counties), and

-hc nade lt qutte .ru.. that things uere going to stay thac way, no Eacter

,.r-:.:""": _:':'::

"t::"""*': in r;ci'ar matcerq mlghr be currenElv evrdent' '

"1I(*..'frY'a-*76+g::p"\zirr5>{}=lp-tr.-..r=e-t4.?t>.r.}.r.-rr.!}:.1.<,-1g,4rr(!i.r-?.*.r-r-..I

I

I

I

aIr

.-t have glven this summary of the events of that afcernoon froo

-.- -rcEoryr unrefreshed by anything whatsoever.. In Particular, I have not

-.talked

over the evengs of that day with any of Ey cotrPantons of Ehe day.

-r' clPecially and explicltly including Peggy Dobbins. These decails have

--- _ been.as I remeober theo, with ury memory's having been completely unaided.

'Professor of Law, University of Alabama

t

I

t

' (oosition siven for identification pur-

"- 'dl"us onlvl r do noc mean Eo implv thac

the Unireisity was in any ruav officrallr'

" '.- 'lnvolved in or rePresenced ll q"y ot.the

actlvities of the day described herein)

Su.bscribed and suorn-to -before. ne

la(.1 rl,t l' 'lI ti' .'l 1!. ,.-'j\i:t _'

' !r coMir(s:ora u, uits 0urljlri :..( ,!':t

n

.sa,s1,1,rsr'1i.i.:r-}rr.sl.' :-'r-i...:\:2,^.'ad?, :}:d,ijrr:-? i1!:!'tae.)r) o/51'ittrF+F+'a.r<t-},|,'a*'. J\e.'r .

.n

rlr

!;

(-

o-

d3

.+

N

dC

-r

-.

-<

^-

l

--

tr

=

-n

=

31

1

,-

o

3r

7:

',=

':-

\

A

a

'::

:

-Y

--

}

-

=

-

:

:-

l_

E

?r

-

*

lt[

=

r

f

=

3

=

3

i i

t

f)

+

i3

i=

+

O

I=

3

=

-=

i

-'

i-o

r

c

i

=

*e

;

r=

=

(D

"'-

-

=

-

-

=

-

-

i1

iI=

;

r

O

-

=

.=

t

1=

,

F

i:T

;

:1

(.

)

jE

:

=

..7

=

E

i:;

r=

=

,;

Q

-

r

r.

:

=

=

j

5.

.c

r

1

.=

"\

6

-:

-

7-

=

=

{:

i

-.

=

=

lrf

l

q-

-.

-

-

s7

1'

-=

i

=

-iU

3

q

it

i =

'1

g;

;1

:'z

E

0

'n (.

!

r5

:o

-

?7

i1

'

a'

;-

<

=

:1

.

I r

#-

=

! = o I o I E 5 a o o -l o-

z! r

D

) al 4

--

--

-_

--

--

--

\d

-

6^

o

^

a=

.i

--

=

.

T

-\

?l

:=

=

3i

,'=

;"

'.'

"1

a

sa

!

!

^

;

--

.1

-a

-

^

=

;.-

;4

:-

2=

-

=

'a

E

;_

:

7

i

?;

1

:-

>

_=

-

2'

i-

-

=

-r

.

a

t

i

;

a7

a

i

?

=

J

;r

j--

=

a;

+

=

'z

=

..,

=

=

:=

=

=

=

.:

_-

-:

-l

-

4

i

|

=

'r.

.

i

=

I

;A

)

ir

;;.

22

:.

t

O

i'^

i1

ii

=

?i

',

7

i5

.;i

t.q

r?

i7

-.

,

=

.-

ln

a

;1

=

2_

?

i 2

r1

=

i:

:-

6

p

:i

-=

=

X

=

=

.^

--

-

-U

=

-7

63

=

.;-

il.

;..

{

H

O

-

,+

=

ro

,o

C

)

!_

.

l=

.-

@

\-

\

-.

Ir

O f= \

= n._

-/

I

O

--

;

?

C

-+

Li

l

=

l:'

<

s,

;

J-

1

4

-

a'

?.

I

t*

'z

{

_.

x

{

!9

rr

rP

.o (! g) 'o r o ?

v a .l

\q -,

t

rP,r1..',.)r-? r1c--7 ,ry n ftTL'Lulu J U *l*)t*Jrgr r-7

gu\

. Publirhcd by

Southcm Orgeniring Conrnincc lor Economic & Sociel Jurticc (SOCI

P.O. Bor 8ll.8irminghem. AL 36201; P.O. Box 113O8, Louisvittc, Ky {O2t1

voL. 7, NO. I

JANUARY, 1982

IN THIS ISSUE

Anti-war activity in North Carolina, page 2

Freedom training session in Louisiana, page 4

Unions conle to a moutrtain town, page 5

The new curriculum on the Klan and racism, page 8 I '!-:

..;

I

I

I

I

I

I

rt r

al F L

:'1t j

:l

!.:,:'

. r. 't.:

o

==!

I

d

C

6

Eo

o

@

.9

Bo

E

!

S

!'

Alabama Women Face Jail

For Voting-Rights Activity

?

\

"_-_..__ __-..{

Two Alabama women may go to prison in .f anuary bccause of their

work to help Black citizens register and vore in rural Pickens County.

They are Julia Wilder,69, president of the Pickens Counry Voters,

League, and Maggie Bozeman, 51, president of rhe local NAACP.

Ms. Wilder and Ms. Bozeman, who live in Aliceville, Ala., were

arrested in November, 1978. The technical charge against them is,,r.ore

fraud." What they were actually doing was helping elderly vorers

understand the ballot and vote. (See previous newsletters)

They were convicted by all-white juries in .t979.

Ms. Wilder was sen-

tenced to five years, and Ms. Bozeman to four years. Ms. Bozeman was

also removed from the teaching .job she had held 27 years.

The convictions were appealed to the Alabama Court of Criminal

Appeals, which upheld them, and to the Alabama Supreme Courr,

which refused to review. ln Novcmber, the u.s. supreme court refuscd

to hear the cascs. Their lawyer, Solomon Seay of Montgomcry, moved

for suspension of sentences, and a hcaring was set for December l.

When the day for the hearing came, the courtroom in Carrollton,

(continucd r.ln pagc 3)

MAJOR ACTION PLANNED FOR JANUARY 9

Protest about the situation in Pickens County is building. ln mid-

December long-time civil-ripirts leader Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth came

to Birmingham to spr:!( .rn behalf of Ms. Boreman and Ms. Wilder at

a rally called by SCLC and SOC. And on Saturday, f anuary 9, rwo

days before their next court appearance, there will be a major action

in Pickens County, sponsorcd by the NAACP, SCLC, the Alabama

Hunger Coalition, NOW, and many orher groups inclu<.ling SOC.

People will mcet at the Salem Baptist Church in Carrollton, Ala, at I

p.m. and march to the courthousc for a prayer meeting. We urge our

readers to take part. Contact SOC for dctails.

Wornen Face Jail for Vote

lTrr,rH.l,:l""T.r:::]1, .^ri ..-- ^-^,_^r ...:^L -.._

,,Ore woman testified that she didn,t know what the votingAla', the Pickens County seat, was packed with supporters of was all aboirt,', Seay reported. ,.The t"r. lJr'r, .i;;;::i:the women. Circuit Judge Clatus.f unkin postponed the hearing said the evidence was ,confusing, but the testimony of thatuntil .f anuary l1' However, local observers doubt that he is one woman *"t rurti.i.nt for the jury to convict.,,planning to suspend the sentences'

corrtroo, pressure on the erderry voters was intense. one

'My wAKING-up pERtoD f them, Lou Sommerville, 95, recently described it.

Pickens County, which is southwest of Birmingham near "The lawyer said to me, didn't Ms. Bozeman come to my

the Mississippi line, is 40 percent Black. lt has no Black elected house and try to make me let her fix up my ballot. lt wasn,r

officials except mayorsof tiny all-Black towns. Ms. Wilderand true. So I told him l'm the Lord's child and I have to tell the

Ms. Bozeman are life-long residents, long active for justice. truth. No matter how much they ask me, I'll tell the truth.,,

"1968 was my waking-up period," Ms. Wilder has said. ,.We 'WE'RE GOING TO GET yOU'

were trying to get Black cashiers hired at Piggly-wiggly. we The charges against Ms. wirder and Ms. Bozeman are not anhad a march and 13 of us went to jail' I was the oldest." isolated incidenl Just last year a young Black man in pickens

Ms. Bozeman describes what was happening in 1978: "We County, IVillie Davis, was charged with disorderly conduct for