Maryland Committee for Fair Representation Et Al v Tawes Et Al Brief on Behalf of Appellees

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

60 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Maryland Committee for Fair Representation Et Al v Tawes Et Al Brief on Behalf of Appellees, 1963. 885c6e20-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/22154128-a4e3-4f4b-8a60-4eada25dac9b/maryland-committee-for-fair-representation-et-al-v-tawes-et-al-brief-on-behalf-of-appellees. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

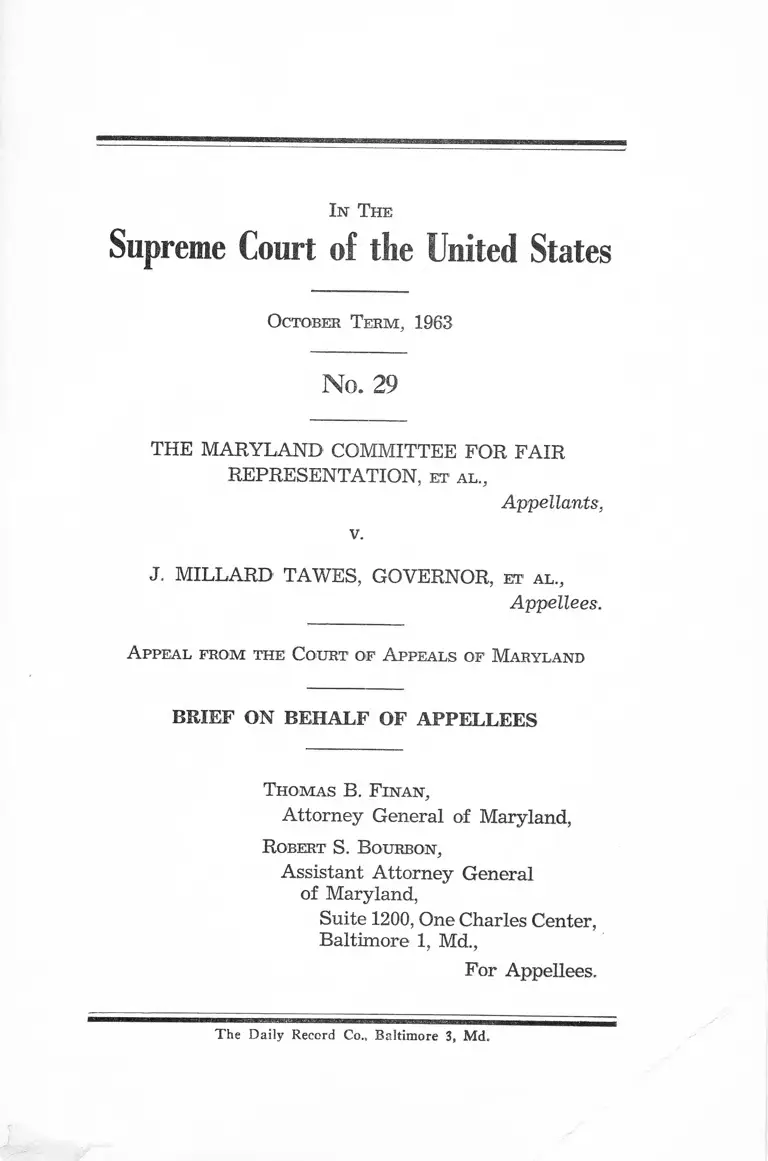

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1963

No. 29

THE MARYLAND COMMITTEE FOR FAIR

REPRESENTATION, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

J. MILLARD TAWES, GOVERNOR, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the: Court of A ppeals of Maryland

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

Thomas B. Finan,

Attorney General of Maryland,

Robert S. Bourbon,

Assistant Attorney General

of Maryland,

Suite 1200, One Charles Center,

Baltimore 1, Md.,

For Appellees,

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore 3, Md.

IN D E X

Table of Contents

page

Opinions of the Court Below......................................

Jurisdiction ......................................................................

Statutes and Constitutional Provisions Involved

Question Presented

Statement of the Case....................................................

Summary of A rgument..................................................

Argument :

I. Maryland Senate apportionment does not in

vidiously discriminate against Appellants and

others similarly situated

II. The Federal Plan analogy is applicable to the

Maryland Senate ................................................

III. The General Assembly as a whole

Conclusion

1

1

2

2

2

7

12

38

46

53

Table of Citations

Cases

BakS ^ arr: 36^ D:s : 186^ M M S ^ , 4 6 . 4 9

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L.

Ed. 884 .................................................................... 1U’ ^“

Caesar v. Williams, 84 Ida. 254, 371 P. 2d 241 8,15,18, 34

Clark v. Carter, 218 F. Supp. 448 15

Daniel v. Davis, .... F. Supp.......................................... 8’ 22

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368, 83 S. Ct. 801, 9 L Ed.

g21 ................................................. 8,15,16,17, 28

11

Jackman v. Bodine, 78 N.J. Super. 414, 188 A. 2d

642 ...........................................................................8,22,23

Levitt v. Maynard, 104 N.H. 243, 182 A. 2d 897........ 8,17, 34

Lindsley v. National Carbonic Gas Co., 220 U.S. 61,

55 L. Ed. 369............................................................. 36

Lisco v. McNichols, 208 F. Supp. 471........................ 8,34

MacDougall v. Green, 335 U.S. 281, 69 S. Ct. 1,

93 L. Ed. 3......................................................... 8,16,17, 40

Mann v. Davis, 213 F. Supp. 577.................................8, 28, 29

Maryland Committee for Fair Representation, et al.

v. Tawes, Governor, et al., 229 Md. 406, 184 A.

2d 715 ...................................................................... 3, 8, 17

McGowan v. State of Maryland, 366 U.S. 420, 81 S.

Ct. 1101, 6 L. Ed. 2d 393.......................................... 9, 36

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell, 294

U.S. 580, 79 L. Ed. 1070......................................... 36

Moss v. Burkhart, 207 F. Supp. 885............................. 27

Nolan v. Rhodes, 218 F. Supp. 953............8,10,11, 22, 42, 49

Ocampo v. United States, 234 U.S. 91, 58 L. Ed. 1231 44

Pressman v. D’Alesandro, 211 Md. 50, 125 A. 2d 35 6

Salsburg v. Maryland, 346 U.S. 545, 74 S. Ct. 280,

98 L. Ed. 281............................................................. 44

PAGE

Scholle v. Hare, 367 Mich. 176, 116 N.W. 2d 350, 369

U.S. 429, 82 S. Ct. 910, 8 L. Ed. 2d 1....................... 14, 26

Sincock v. Duffy, 215 F. Supp. 169 8,10, 27, 37, 42

Sobel v. Adams, 208 F. Supp. 316......................... 8,15, 20, 34

South v. Peters, 339 U.S. 276, 70 S. Ct. 641, 94 L. Ed.

834 ............................................................................ 17

State v. Dashiell. 6 H. & J. 268 6

State v. Shillinger, 6 Md. 449 ....................................... 6

Sweeney v. Notte,.... R .I ......., 183 A. 2d 296.............. 26

Toombs v. Fortson, 205 F. Supp. 248........................... 25

W.M.C.A., Inc., et al. v. Simon, Secretary of State of

New York, et al., 208 F. Supp. 368, 370 U.S. 190,

82 S. Ct. 1234, 8 L. Ed. 2d 430..........8, 9,14,15,19, 34, 40

Wright v. Hammer, 5 Md. 370.................................... 6

Statutes

Annotated Code of Maryland:

Article 25A (1957 Edition, 1962 Supplement).... 31

Article 40, Section 42 (1962 Supplement).......... 2

Constitution of Idaho:

Article III, Section 2 19

Constitution of Maryland:

1776, Articles II, IV, V .......................................... 4

Articles XIV, XV, XVI............................... 5, 49

1851, Article III, Section 2 ............................. 5

Section 3 ................................... 4

1864, Article III, Section 3 ............................ 6

Section 4 ................................... 5

1867, Article III, Section 2 ................................... 5, 6

Section 3 ................................... 5

Section 4 ................................... 5

Section 5 ................................... 5

Section 6 .................................. 5

Article XI, .................................................... 6

1867, as amended, Article III, Section 2 .......... 2

Section 9 ........... 37

Article IV, Section 14 ........ 37

Article XI-A ......................... 31

Constitution of Tennessee:

Article II, Section 6................................................ 23

Constitution of the United States:

Fifth Amendment .................................................. 10, 42

Fourteenth Amendment ..................... 2, 3,12,17,18, 23,

35, 36, 38, 42

Laws of Maryland:

1796, Chapter 68 6

1918, Chapter 82 ................................................... 6

1963, Chapter 617 ................................................. 52

I ll

PAGE

IV

28 U.S.C.:

1257(2) ..................................................................... 1

2101(c) .................................................................... 1

PAGE

Miscellaneous

Baltimore Morning Sun:

July 28, 1962, page 5.................................................... 14

January 3, 1963........................................................... 52

Bell, The Legislative Process in Maryland...................... 10

Bickel, Reapportionment and Liberal Myths, Com

mentary, June, 1963...................................... 31, 32, 41, 44

Book of the States, 1962-63, Council of State Govern

ments .......................................................................... 49

Federalist, The, Wesleyan University Press (1961) 48

Federalist Papers, The, No. 63...................................... 10, 42

Hall, History of Baltimore, Volume 1......................... 6

38 Indiana L. J. 252, The Significance of Baker v. Carr

for Indiana ................................................................. 27

Journal of the Constitutional Convention, G. P. Put

man Sons, 1903................................................... 10, 34,42

61 Michigan L. Rev. 107, Jerold Israel, On Charting a

Course through the Mathematical Quagmire:

The Future of Baker v. Carr...............................14, 34,40

61 Michigan L. Rev. 645, Robert B. McKay, Political

Thickets and Crazy Quilts: Reapportionment

and Equal Protection 14

61 Michigan L. Rev. 711, Jo Desha Lucas, Legislative

Apportionment and Representative Govern

ment: The Meaning of Baker v. Carr 14, 33

Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law........................... 4, 5, 6

16 Oklahoma L. Rev. 59, Maurice H. Merrill, Blazes

through the Thicket of Reapportionment 14

V

Report of Committee on More Equitable Representa

tion in the General Assembly of Maryland, Feb

ruary 14, 1947 ........................................................... 45

Scharf, History of Baltimore City and County (1881) 6

Tyler, Court Versus Legislature (27 Law and Con

temporary Problems 390)..................................... 9,34

Walsh, Final Report of The Commission on More

Equitable Representation in the General As

sembly of Maryland.............................................. 43

Washington Evening Star, July 28, 1962.................... 14

Washington Post and Times Herald, September 25,

1963 .......................................................................... 29

65 West Virginia L. Rev. 129, James Edmundson, Jr.,

Legislative Reapportionment, Baker v. Carr........ 33

72 Yale L. J. 968, Baker v. Carr and Legislative Ap

portionments: A Problem of Standards............. 26, 51

PAGE

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1963

No. 29

THE MARYLAND COMMITTEE FOR FAIR

REPRESENTATION, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

J. MILLARD TAWES, GOVERNOR, et al.,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the Court of Appeals of Maryland

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF APPELLEES

OPINIONS OF THE COURT BELOW

Appellees accept Appellants’ statement outlining the

Opinions of the Court below.

JURISDICTION

Appellants allege that the Supreme Court of the United

States has jurisdiction pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 1257(2) and

28 U.S.C. 2101 (c).

2

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves:

(1) Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States, containing the equal

protection and due process clauses, printed in Appendix

A, Appellants’ Brief, page 76; and

(2) Section 2 of Article III of the Maryland Constitu

tion, printed in Appendix A, Appellants’ Brief, page 76.

QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States require that the membership of the

Senate of the State of Maryland “be based on, or reason

ably related to, the present population” of the various

political subdivisions of the State?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The sole question properly presented by this appeal

is the validity, consistent with the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States, of the

present apportionment plan of the State Senate of Mary

land, as embodied in Article III, Section 2, of the Mary

land Constitution. Appellants in the trial court con

ceded that, at least for the present, the somewhat re

cently enacted stopgap legislation regarding the com

position of the Maryland House of Delegates (Chapter 1,

Acts of the 1962 Special Session of the General Assembly

of Maryland, also known as Article 40, Section 42, Anno

tated Code of Maryland, 1962 Supplement, printed in Ap

pendix A, Appellants’ Brief, page 77) satisfied the de

mands of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. In the Court of Appeals of Maryland, Ap

3

pellants revised their position and alternatively prayed

that the General Assembly be treated as a “whole” . In

their Brief in this Court, Appellants allege as their second

“Question Presented” the question of “total representa

tion” as falling short of the demands of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

In its Opinion of September 25, 1962, reported at 229

Md. 406, 184 A. 2d 715, printed at R. 162, 164, the court

stated:

“No question is presented as to the validity of the

‘stopgap’ legislation or the reapportionment of the

House of Delegates.”

And in his dissent to the above-quoted majority opinion,

Chief Judge Brune confirmed this when he said, for the

minority (R. 176):

“It is true that the apportionment of the House is

not under attack on this appeal and no question with

regard thereto is now before us.”

And the above is further confirmed by the language of

the trial court’s opinion (R. 114), where Judge Duckett

states:

“ .. . Petitioners have conceded that the Lower House

has been legally reapportioned according to popula

tion.”

Consequently, it is clear that Appellants attempt here

to raise obliquely what they cannot raise directly; the

question of proper apportionment in the Maryland House

of Delegates or of “ total representation” in the General

Assembly is not now before this Court.

Insofar as this appeal is concerned, the gravamen of

Appellants’ claim is set forth in Paragraph 22 of the Bill

of Complaint (R. 8), to wit:

4

“ Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment requires

that representation in the State Senate of Maryland

be based on, or reasonably related to, the present

population of the counties and the City of Baltimore,

and that the total number of members in that body

to' which the counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore,

Montgomery, Prince George’s and the City of Balti

more are entitled is 22, instead of the 10 Senators

through whom they are now represented in that body

(assuming no increase in its present membership of

29 Senators).”

Paragraph 14 of Appellees’ Answer (R. 91, 92) denied

the above allegations and affirmatively stated, inter alia,

that representation in the Maryland Senate need not be

based on or reasonably related to the present population of

the counties and Baltimore City.

Historically and theoretically, the two houses of the

Maryland General Assembly were designed to represent

different segments or ideologies present in the State. The

House of Delegates, according to the Constitution of 1776,1

was comprised of four delegates from each county, plus

two from Annapolis and Baltimore Town (then a part

of Baltimore County). The Constitution of 1851 and each

succeeding Constitution provided for membership in the

House of Delegates to be based generally on a population

ratio.

The Constitution of 18512 provided that each county

should be allotted representation generally based on popu

lation, as determined by the census of 1860, subject, how

ever, to the provision that no county should have less than

two delegates.

1 Articles II, IV and V (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

360).

2 Article III, Sec. 3 (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

406).

5

Similarly, the Constitution of 18643 apportioned the

House on the basis of population, with one delegate for

the first 5,000 persons, and thereafter each delegate to

represent a graduated scale of the population.

The Constitution of 18674 originally allotted seats in

the House based upon a graduated scale of population,

permitting, however, each county or legislative district of

Baltimore City, regardless of population, to have a mini

mum of two delegates.5 6

By contrast, the Senate of Maryland under the Consti

tution of 1776® was composed of 15 Senators, six from the

Eastern Shore and nine from the Western Shore, chosen

by an electoral college of 40 members. Each county sup

plied two electors and Annapolis and Baltimore Town

were allotted one each.

Starting with the Constitution of 1851,7 each county was

allotted one Senator, as was Baltimore City (Baltimore

City for the first time having been made a separate and

independent political subdivision).

3 Article III, Sec. 4 (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

442).

4 Article III, Sec. 3 (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

485).

5 It is interesting to note that in Article III, Sections 3, 4 and 5

of the Constitution of 1867, prior to amendment, in establishing and

providing for the members in the House of Delegates, the word

“ population” itself is used on at least ten occasions. This clearly in

dicates that the framers of the Constitution intended that the House

be based upon, or reasonably related to, population. Also of interest

is the fact that by Section 6 of Article III of the Constitution of 1867,

before amendment, members of the House were elected for a term

of two years. (This was changed by the quadrennial election amend

ment of Article X V II of the Maryland Constitution in 1922.) By

contrast, in Article III, Section 2 of the Constitution of 1867, before

amendments, the word “ population” is not used.

6 Articles X IV , X V and X V I of the Maryland Constitution (Niles,

Maryland Constitutional Law, Pages 362, 363).

7 Article III, Section 2 (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

406).

6

The Constitution of 18648 continued to allot one Senator

to each county, but also permitted one each from the three

legislative districts of Baltimore City. This provision was

re-adopted in the Constitution of 18679 and has remained

in force, with the exception of Baltimore City, which re

ceived an additional legislative district in 1900 and two

additional legislative districts in 1922, subsequent to the

annexation of portions of Baltimore County and Anne

Arundel County in 1918 (Chapter 82, Laws of 1918).10

There seems to be some confusion regarding the status

of the City of Baltimore and it is therefore deemed

desirable to discuss briefly its history. Although it was

chartered in 1796 (Acts of 1796, Chapter 68), it was by

virtue of the provisions of the Constitution of 1851, that

the City of Baltimore was recognized to be a separate,

distinct and independent political subdivision of the

State.11 * By virtue of the provisions of Article XI of the

Constitution of 1867, Baltimore City was granted the con

stitutional right to maintain its own local government,

subject, however, to control by the General Assembly.13

In this respect the governmental functions of Baltimore

8 Article III, Section 3 (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

442).

9 Article III, Section 2 (Niles, Maryland Constitutional Law, Page

485).

10 On Page 51 of the Appellants’ Brief there is quoted portions of

Governor Ritchie’s statement relative to increased representation in

the Legislature for Baltimore City. Unfortunately, the Appellants

have quoted out of context and the full sentence of the statement of

Governor Ritchie to the General Assembly is as follow s:

. . The growth of population in Baltimore by reason of exten

sions of its territory and many other considerations, entitles the

city to increased representation in both houses of the General

Assembly. . . .” . (Emphasis supplied.)

11 Scharf, History of Baltimore City & County (1881), pp. 62-63,

Hall, History of Baltimore, Vol. 1, p. 151, Wright v. Hammer, 5 Md.

370; State v. Shillinger, 6 Md. 449; cf. State v. Dashiell, 6 H. & J.

268.

13 See Pressman v. D’Alesandro, 211 Md. 50, 57, 125 A. 2d 35.

7

City were placed in a unique position comparable in the

United States only to that of the City of St. Louis.

The Appellees also' wish to emphasize that the use of

a combination of certain counties and Baltimore City for

purposes of comparison is an artificial attempt to justify

the Appellants’ position. It must be remembered that the

said political sub-divisions, with the exception, perhaps,

of Baltimore City and County, in many respects have

no common economic, social or other basis for com

parison. While it is conceded that each of the four counties

and Baltimore City are rapidly growing urban areas,

nevertheless, large portions of each of those counties are

devoted to farming and other rural pursuits. Therefore,

the urban-rural cleavage stressed by the Appellants exists

within the very counties which the Appellants claim are

adversely affected by the urban-rural conflict. Likewise,

for example, the people of Baltimore City, because of its

industrial concentration, do not share the problems of

the tobacco farmers of Prince George’s and Anne Arundel

Counties or those of the dairy farmers in the northern

part of Baltimore County or western part of Montgomery

County. It is therefore urged that these combinations are

artificial and may at times create an illusory impression.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I. Maryland Senate apportionment does not invidiously

discriminate against Appellants and others similarly sit

uated.

While Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186, 82 S. Ct. 691, 7 L. Ed.

2d 663, determined jurisdiction, justiciability and stand

ing to sue, it decided those various questions and nothing

more. Neither did it decide nor indicate what constitutes

unconstitutional apportionment, nor whether population

is the sole permissible basis for legislative apportionment

under the equal protection clause.

8

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368, 83 S. Ct. 801, 9 L. Ed.

2d 821, does not decide questions relating to composition

of the state or federal legislatures, nor does it lay down

“basic ground rules implementing Baker v. Carr” . See

Opinion of Mr. Justice Douglas, speaking for the Court,

83 S. Ct. at 807, and concurring opinion of Mr. Justice

Stewart, at 809. Further, it does nothing to limit the ap

plication of MacDougall v. Green, 335 U.S. 281, 69 S. Ct.

1, 93 L. Ed. 3, wherein this Court spoke of not denying

a state “the power to assure a proper diffusion of political

initiative as between its thinly populated counties and

those having concentrated masses” .

The ruling of the Court of Appeals of Maryland below

(229 Md. 406, 184 A. 2d 715), wherein it held that his

torical precedent furnishes justification and constitutes

a rational basis for the present apportionment of the

Maryland Senate, is supported in Caesar v. Williams, 84

Ida. 254, 371 P. 2d 241; Sobel v. Adams, 208 F. Supp. 316;

W.M.C.A., Inc. v. Simon, 208 F. Supp. 368; Nolan v.

Rhodes, decided June 12, 1963, 218 F. Supp. 953; Daniel

v. Davis, decided June 28, 1963,.... F. Supp........ ; and Jack-

man v. Bodine, 78 N.J. Super. 414, 188 A. 2d 642. See also

the dissenting opinions in Sincock v. Duffy, 215 F. Supp.

169 and Mann v. Davis, 213 F. Supp. 577.

Interests other than population must be taken into ac

count in the apportionment of the Maryland Senate, where

as in this case, the apportionment of the House of Dele

gates is not under attack, nor in question. See Lisco v.

McNichols, 208 F. Supp. 471, recognizing as a relevant

factor representation of industrial interests; Sobel v.

Adams, supra, representation of general regional in

terests; Caesar v. Williams, supra, protection of sparsely

settled areas; Levitt V. Maynard, 104 N.H. 243, 182 A. 2d

897, recognizing as “rational,” wealth and the proposition

9

of total taxes paid by a district; W.M.C.A., Inc. v. Simon,

supra, a state apportionment plan “of historic origin”

and “not irrational” , which “clearly gives weight to

population within the state’s counties which forms a basis

for the ingredient of area, accessibility and character of

interest” , and Tyler, Court Versus Legislature, 27 Law and

Contemporary Problems, 390, 391, 393, economic interests.

Under the Maryland plan, history and tradition may be

found to be a rational exercise of state policy in connection

with the apportionment here under attack. The state is to

be allowed every reasonable latitude and the Maryland

Constitution will not “ . . . be set aside if any state of facts

reasonably may be concerned to justify it . . .” . McGowan

v. State of Maryland, 366 U.S. 420, 81 S. Ct. 1101, 6 L. Ed.

2d 393.

II. The Federal Plan analogy is applicable to the Mary

land Senate.

The evolution of the Maryland Senate finds analogy

and precedent in the Federal Plan, insofar as the United

States Senate is concerned. Based upon compromise, as

was the continued expansion of the Federal Union, Bal

timore City’s periodic apportionment of additional Sena

tors, because of that city’s unique position, geographically,

as a great port city, industrially and otherwise, represents

a rational exercise of State policy.

The allocation to each county of a single Senator, on

a nonpopulation basis, is rational where, as found by the

court below, the counties in Maryland “have always pos

sessed and retained distinct individualities” (R. 166). See

W.M.C.A., Inc. v. Simon, supra.

The counties, in relation to the states, may be compared

to the states in relation to the Federal Government. Only

the original 13 states may have possessed sovereignty and,

10

in reality, none of them possess now many, if any, true

attributes of such sovereignty.

Appellees question how a defense may be made of a

federal Senate system which results in a gross dilution of

individual voting power up to a ratio of 75 to 1, over

twice the maximum complained of here. Is the rationale

of Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497, 74 S. Ct. 693, 98 L. Ed.

884, applicable to the present apportionment of the United

States Senate, under Amendment V of the Bill of Rights’.

The Federal analogy finds support in Nolan v. Rhodes,

supra. And see the dissenting opinion of Judge Layton in

Sincock v. Duffy, supra.

The Maryland Senate system served as a model in many

respects for the Federal Senate. The Journal of the Con

stitutional Convention, G. P. Putnam Sons, 1903, page 202;

No. 63, The Federalist Papers.

Recognition of Baltimore City in additional Senate rep

resentation constituted an exception to the so-called Fed

eral Plan rather than an abandonment of it.

The recognition of the many factors surrounding Balti

more City’s unique position in Maryland is a reasonable

and rational State policy. Its Senate apportionment was

increased because of its size. Bell, The Legislative Process

in Maryland.

The compromise so evident in the evolution of the Mary

land Senate system, which gave representation to the

State’s varied and diverse interests, reflected the State’s

collective judgment, from time to time, as to what best

served and suited those interests, is rational and should

be upheld.

11

III. The General Assembly as a whole.

The alleged malapportionment of the General Assembly

“as a whole” is not now before the Court. (See R. 114, 162,

164, 176.)

Representative government, whether upon the State or

Federal level, has clearly recognized the lesser unit of

government as a basis for political representation.

The so-called “principle of majority rule” , as advanced

by Appellants, has never been a part of either the Federal

or state systems; the foundation stone of democratic gov

ernment is the protection of minorities from the “tyranny

of the majority” . See the dissenting opinion of Mr. Justice

Frankfurter, in Baker v. Carr (369 U.S. at 301); Nolan v.

Rhodes, supra, 218 F. Supp. at 958.

Baltimore City, together with Baltimore County, or the

four populous counties of Baltimore, Anne Arundel, Prince

George’s and Montgomery together, might, if given the

representation urged by Appellants, create a new mal

apportionment far worse than that here complained of.

Can such reorientation assure any “proper diffusion of

political initiative” ?

If this Court should inquire into the question of whether

the Maryland governmental structure as presently consti

tuted actually possesses “responsiveness” , it should be

noted that the role of a strong Governor, as Maryland has

had in recent years, with his base of popular support, tends

to offset some discrepancy in Senate representation.

12

ARGUMENT

I.

M ARYLAND SE N A T E APPO RTIO N M EN T D O ES NOT IN V ID IO U SLY

D ISC RIM IN A TE A G A IN ST A PPE LLA N T S AND

O TH E R S SIM ILA R LY SIT U A T E D ,

Unquestionably, the immediate point of beginning of

this and other current reapportionment suits in the land

mark decision of this Court in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186,

82 S. Ct. 691, 7 L. Ed. 2d 663. There, appellants, qualified

voters of the State of Tennessee, sued in the United States

District Court for the Middle District of Tennessee, alleg

ing deprivation of federal constitutional rights, in that the

state apportionment statute governing members of the

General Assembly of Tennessee among the state’s 95 coun

ties denied them the “equal protection of the laws accorded

them by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States by virtue of the debasement of their

votes . . .” . This Court, speaking through Mr. Justice

Brennan (at 369 U.S. 197), stated:

“ In light of the District Court’s treatment of the

case, we hold today only (a ) that the court possessed

jurisdiction of the subject matter; (b) that a justiciable

cause of action is stated upon which appellants would

be entitled to appropriate relief; and (c) because ap

pellees raise the issue before this Court, that the appel

lants have standing to challenge the Tennessee appor

tionment statutes.”

Mr. Justice Stewart, concurring (369 U.S. at 265-266),

stated:

“The Court today decides three things and no more:

‘ (a) that the Court possessed jurisdiction of the sub

ject matter; (b) that a justiciable cause of action is

stated upon which appellants would be entitled to ap

propriate relief; and (c) . . . that the appellants have

standing to challenge the Tennessee apportionment

statutes’.

13

“ The complaint in this case asserts that Tennessee’s

system of apportionment is utterly arbitrary — with

out any possible justification in rationality. The Dis

trict Court did not reach the merits of that claim, and

this Court quite properly expresses no view on the

subject. Contrary to the suggestion of my Brother

Harlan, the Court does not say or imply that ‘state

legislatures must be so structured as to reflect with

approximate equality the voice of every voter’. Post.,

p. 332. The Court does not say or imply that there is

anything in the Federal Constitution ‘to prevent a

State, acting not irrationally, from choosing any elec

toral legislative structure it thinks best suited to the

interests, temper and customs of its people’. Post., p.

334. And contrary to the suggestion of my Brother

Douglas, the Court most assuredly does not decide the

question, ‘may a State weight the vote of one county

or one district more heavily than it weights the vote

in another?’. Ante, p. 244.

“In MacDougall v. Green, 335 U.S. 281, the Court

held that the Equal Protection Clause does not ‘deny

a State the power to assure a proper diffusion of politi

cal initiative as between its thinly populated counties

and those having concentrated masses, in view of the

fact that the latter have practical opportunities for

exerting their political weight at the polls not avail

able to the former’. 335 U.S. at 284. In case after case

arising under the Equal Protection Clause the Court

has said what it said only last Term — that ‘the Four

teenth Amendment permits the States a wide scope of

discretion in enacting laws which affect some groups

of citizens differently than others’. McGowan v. Mary

land, 366 U.S. 420, 425. In case after case arising under

that Clause we have also said that ‘the burden of

establishing the unconstitutionality of a statute rests

on him who assails it’. Metropolitan Casualty Ins. Co.

v. Brownell, 294 U.S. 580, 584.

“Today’s decision does not turn its back on these

settled precedents. I repeat, the Court today decides

only: (1) that the District Court possessed jurisdic-

14

tion of the subject matter; (2) that the complaint pre

sents a justiciable controversy; (3) that the appellants

have standing.”

Neither Scholle v. Hare, 369 U.S. 429, 82 S. Ct. 910, 8

L. Ed. 2d 1, “remanded to the Supreme Court of Michigan

for further consideration in the light of Baker v. Carr . . ”

or W.M.C.A., Inc., et al. v. Simon, Secretary of State of

New York, et al., 370 U.S. 190, 919, 82 S. Ct. 1234, 8 L. Ed.

2d 430, remanded on the same basis, can be said to do other

than confirm the narrowness of the holding in Baker v.

Carr, supra, notwithstanding Appellants’ protestations to

the contrary (Brief, pages 15, 29).

Certainly Mr. Justice Stewart was of the opinion, in

staying the order for apportionment in Scholle, that “ . . .

the issues decided by the Michigan Supreme Court are new

issues; ones that were not decided in Baker v. Carr.” See

Baltimore Morning Sun, July 28, 1962, page 5; Washington

Evening Star, July 28, 1962, page 5 (R. 170). Baker neither

decided nor indicated what constitutes unconstitutional

apportionment. Jerold Israel, On Charting a Course

through the Mathematical Quagmire: The Future of Baker

v. Carr, 61 Mich. L. Rev. 107, 112. Nor does Baker answer

the question of whether population is the sole permissible

basis for legislative apportionment under the equal pro

tection clause. Maurice H. Merrill, Blazes through the

Thicket of Reapportionment, 16 Oklahoma L. Rev. 59, 63.

Even Robert B. McKay’s Political Thickets and Crazy

Quilts: Reapportionment and Equal Protection, 61 Mich.

L. Rev. 645, and Jo Desha Lucas’ Legislative Apportion

ment and Representative Government: The Meaning of

Baker v. Carr, 61 Mich. L. Rev. 711, admit the narrowness of

Baker v. Carr while asserting, as do Appellants here, that

it must have meant much more.

15

As the Court stated in W.M.C.A., Inc, v. Simon, 208 F.

Supp. 368, 372, 373 (on remand):

. . we are unable to premise an invalidity of the

provisions of the State of New York upon the Baker

v. Carr determination by reason of the absence of

applicable indicia. . . . Counsel for plaintiffs has con

ceded that ‘there is nothing in the explicit opinion of

Baker against Carr which would indicate how ulti

mately the cases were to be resolved on the merits’ ,

although counsel contended that there was ‘much in

Baker against Carr which is implicit’ . . . This Court

is unable to discern this result for which plaintiffs

here argue.”

See Clark v. Carter, 218 F. Supp. 448, 452 (Kentucky Con

gressional redistricting statute); Caesar v. Williams, 84

Ida. 254, 371 P. 2d 241, 244; Sobel v. Adams, 208 F. Supp.

316.

Gray v. Sanders, 372 U.S. 368, 83 S. Ct. 801, 9 L. Ed. 2d

821, decided on March 18, 1963, cited by Appellants as in

volving a principle “equally applicable here” (Brief, page

42), struck down the Georgia Unit Vote System as used

by that state for counting votes in primary elections for

state-wide offices. Mr. Justice Douglas, speaking for the

Court, set forth in unmistakably clear language (83 S. Ct.

at 807):

“Nor does the question here have anything to do

with the composition of the state or federal legislature.

And we intimate no opinion on the constitutional

phases of that problem beyond what we said in Baker

v. Carr, supra. The present case is only a voting case.”

(Emphasis supplied.)

Mr. Justice Stewart, whom Mr. Justice Clark joined,

concurring, said (83 S. Ct. at 809):

“This case does not involve the validity of a State’s

apportionment of geographic constituencies from

16

which representatives to the State’s legislature as

sembly are chosen, nor any of the problems under

the Equal Protection Clause which such litigation

would present. We do not deal here with ‘the basic

ground rules implementing Baker v. Carr’. This case,

on the contrary, involves statewide elections of a

United States Senator and of state executive and

judicial officers responsible to a statewide constituency.

Within a given constituency, there can be room for

but a single constitutional rule — one voter, one vote.

United States v. Classic, 313 U.S. 299, 61 S. Ct. 1031,

85 L. Ed. 1368.”

The county unit system, of course, no longer prevails

in Maryland, as of the judgment of the United States Dis

trict Court for the District of Maryland entered May 10,

1963, in Maryland Committee for Fair Representation,

et al. v. J. Millard Tawes, et al., Civil Action No. 14452

(consent decree in which Maryland’s Attorney General

participated, on behalf of Defendants).

Presumably, for the reverse has nowhere been shown

nor has it even been suggested by Appellants, Gray v.

Sanders, supra, does nothing to overrule or limit the appli

cation of MacDougall v. Green, 335 U.S. 281, 69 S. Ct. 1,

93 L. Ed. 3, where this Court said:

“To assume that political power is a function ex

clusively of numbers is to disregard the practicalities

of government. Thus, the Constitution protects the in

terests of the smaller against the greater by giving

in the Senate entirely unequal representation to popu

lations. It would be strange indeed, and doctrinaire,

for this Court, applying such broad constitutional con

cepts as due process and equal protection of the laws,

to deny a State the power to assure a proper diffusion

of political initiative as between its thinly populated

counties and those having concentrated masses, in

view of the fact that the latter have practical oppor

tunities for exerting their political weight at the polls

17

not available to the former. The Constitution — a

practical instrument of government — makes no such

demands on the States.” (Quoted from approvingly

in Mr. Justice Stewart’s concurring opinion in Baker

v. Carr, supra, 369 U.S. at 265, 266.)

And see South v. Peters, 339 U.S. 276, 70 S. Ct. 641, 94

L. Ed. 834, affirming the principle of MacDougall, but per

haps in turn silently overruled by Gray on other grounds.

See Dissenting Opinion of Mr. Justice Harlan in Gray v.

Sanders, supra (83 S. Ct. at 809).

While it may be true, as stated by Chief Judge Brune in

his dissent to the latest opinion below (R. 173), that Baker

v. Carr could not well have determined the exact point at

which protection against the debasement or dilution of

voting rights through state legislative apportionment of

representation will be afforded in any specific case; none

theless, it certainly can be said that an absence to date of

any “guidelines for formulating specific, definite, wholly

unprecedented remedies” has resulted in a wide diverg

ence of opinion and action among the various state and

federal courts and among the judges of those courts, not

only as to right but as to remedy. See Mr. Justice Frank

furter’s dissenting opinion in Baker (369 U.S. at 267).

Because of a lack of guiding judicial principles upon which

to rely, perhaps too many courts may find it considerably

more difficult to determine what type of discrimination,

in legislative apportionment matters, invidiously violates

the commands of the Fourteenth Amendment than to de

termine what does not. Surely any attack such as the

present one, striking as it does at the very taproots of the

Maryland political and governmental system, ought not

to be sustained on such a basis.

The nub of the Court of Appeals’ ruling here appealed

from (229 Md. 406, 184 A. 2d 715) (R. 162) is that popula

18

tion considerations need not be taken into account in

determining whether the Maryland Senate apportionment

plan invidiously discriminates in violation of the Four

teenth Amendment and that historical precedent furnishes

justification and constitutes a rational basis for the present

apportionment of the Senate. Appellants’ position, earlier,

apparently was that the Senate should be based strictly on

population. They now seem to have retreated somewhat

to a basis “partly on population and partly on area” (R.

122, Brief, page 72). However, population should remain

the “strongly dominant factor” , in their view (Brief,

page 72).

The Maryland ruling finds support in the following

cases:

Caesar v. Williams, supra, decided on April 3, 1962, (re

hearing denied on May 8, 1962). In that case two Idaho ap

portionment statutes were attacked by persons claiming

that neither provided substantial equal representation for

the residents of the more populous counties in the House of

Representatives. The trial court upheld the claim of un

constitutionality, but the appellate court reversed and

stated as follows (371 P. 2d at 247):

“It is clear that the constitutional requirement of

one representative for each county, superimposed on

the population requirement of the statute, will lead

to discrepancies between the number of people who

will be represented by each individual representa

tive constituting the house of representatives, on a

purely numerical basis. Respondent has forcefully

pointed out such discrepancies, particularly by the

exhibit in his complaint. Clark County, with a 1960

population of 915 persons, and Camas County with a

1960 population of 917, each is entitled to one repre

sentative under both the 1951 act and the 1933 act;

Elmore County, with a 1960 population of 16,719, and

Cassia County, with a 1960 population of 16,121, each

19

likewise is entitled to only one representative under

the 1951 act; whereas under the 1933 act each would

be entitled to two representatives. These examples

illustrate the extremes of the discrepancies in popula

tion representation. But, is such gross disparity so

arbitrary and capricious that the 1951 act and the

1941 act must be stricken down as unconstitutional,

in favor of the previous 1933 act? Also, is this dis

parity created by the act itself, or created by the con

stitution? Another question is whether the disparity

is the result of application of a set of facts and cir

cumstances for which the legislation was not de

signed? Also, in such disparity violative of the equal

protection clauses of Idaho’s Constitution, Art. I, sec.

2 and of the United States Constitution, Fourteenth

Amendment?

“The constitutional limitations of one representa

tive per county and a maximum of not to exceed

three times the number of senators immediately de

stroys any possibility of representation based solely

on a per-capita or per-voter basis. Attempting to com

pare the representation afforded by the constitutional

requirement of one representative per county to the

representation to be afforded on a per capita basis is

impossible. . . .

“The members of the Idaho Constitutional Con

vention were fully cognizant of the impossibility of

mathematical equality in election of representatives

by reason of this constitutional requirement of one

representative per county, . . .”

This decision is of extreme importance because of the

fact that Idaho, like Maryland, constitutionally elects one

senator for each county, based upon a geographical distri

bution of political strength. Article III, Section 2, Idaho

Constitution.

In W.M.C.A., Inc. v. Simon, supra, on remand, the court

upheld a New York apportionment plan which, inter alia,

2 0

allows each county in the state, with one exception, at

least one assemblyman in the State Assembly. Depending

upon population and on a “ratio” basis, representation is

increased. See 208 F. Supp. at 371, 383. The Senate is

based substantially on population. Schuyler County, with

a population of 15,044, is entitled to one representative,

while Suffolk County, with a population of 666,784, is en

titled to three, a variation of almost 15 to 1 between them.

See 208 F. Supp. at 383, 384. The court held there (208 F.

Supp. at 376) that the apportionment provisions were “of

historic origin” and “not irrational” ; the plan “clearly gives

weight to population within the state’s counties which

forms a basis for the ingredients of area, accessibility and

character of interest” .

The court further said that the apportionment scheme

had “factors adapted to the needs of the State of New York

constituted as it is of urban, suburban and rural areas,

with congestion of population in one spot, with areas of

lesser intensity in other locations and with sparsely settled

spaces more remote from the centers of population. All

ingredients are present, there is no arbitrariness in formu

lae or in the result thereof.”

In Sobel v. Adams, supra, a proposed Florida apportion

ment plan was approved which resulted in Dade County

with 19% of the state population (or 935,047) obtaining

but one of 46 state senators. The State House of Repre

sentatives is apportioned substantially on a population

basis.

The court was of the opinion (at 321) that:

“It is not required that, in all events, either or both

houses of a bicameral legislature must be apportioned

upon a population basis of either exact or approxi

mate equality of representation. . . . It is our con

sidered view that the rationality of a legislative ap

21

portionment may include a number of factors in addi

tion to population.”

In dealing with the House representation question, the

court said (at 322, 323):

“The zeal of the advocates of strict apportionment

by a rigid population allocation fails to convince us

that the results so achieved would be rational. The

plan proposed by the legislature of a representative

from each county with additional representatives dis

tributed on a basis of a population ratio seems to us

to provide a formula which secures the desirable

county representation and a reckoning, to the extent

required, of the population factor.”

Apropos of the State Senate, the court stated (at 323):

“Because such a large portion of the legislative

function deals with special acts applicable only to a

single county or municipality, we think it would be

unwise and illogical to provide for more than one

Senator from any county, except perhaps from Dade

which enacts its own local legislation. Under the plan

before us the House of Representatives would be ap

portioned by a formula in which population is heavily

weighted. Because of this we think that population

need not be a major factor in the apportionment of

the other House. Such apportionment must, however,

be made upon a rational basis.”

In analyzing the Senate districting scheme in respect

of any possible “crazy quilt” attributes, it might possess,

the court indicated (at 323, 324):

“ It is possible, but we refrain from saying prob

able, that some of the county alignments or absence

of alignments were the result of the political neces

sity of concessions in order to procure the passage

of the measures we have before us. Disparities and

departures from the plan may be pointed out but

these are mainly of a de minimis nature and are not

2 2

such as, in our judgment, render the plan invidiously

discriminatory or rob it of its rationality. . . . What

is urban and what is rural, so far as a county is con

cerned, may depend upon a point of view.”

In Nolan v. Rhodes, decided June 12, 1963, 218 F. Supp.

953, the court sustained an Ohio constitutional apportion

ment plan involving the state House of Representatives,

established on a basis partly of area and partly on popula

tion. The state Senate was not involved.

Commenting upon a system guaranteeing to each county

one representative in the House and upholding it against

an attack on equal protection grounds, notwithstanding a

ratio maximum of almost 15 to 1, the court said (at 957):

“There does not seem to be much reason for a bicam

eral legislature if both houses are required to be ap

portioned on the same basis.”

Daniel v. Davis, decided June 28, 1963, by a statutory

District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, upheld

a Louisiana apportionment plan for the House of Repre

sentatives (which reaches an 8 to 1 disproportion ratio)

where each parish in Louisiana, with one exception, re

ceived a representative, as does each of the 17 wards in

New Orleans. The remaining seats in the House are dis

tributed according to the Method of Equal Proportions.

In Jackman v. Bodine, 78 N.J. Super. 414, 188 A. 2d 642,

the New Jersey apportionment system, which allows one

Senator to each county regardless of its population (re

sulting in a maximum disproportion ratio of 19 to 1) and

allocates House members on a population basis, was sus

tained, the court saying (188 A. 2d at 650):

“The fact that the present system of representation

in our State Senate does not attempt to equalize dis

proportionate population differences between the vari

23

ous counties . . . is not conclusive on the ultimate ques

tion of whether or not the system discriminates in

vidiously. To be sure, where the make up of one

branch of state government completely disregards

population as a factor in representation, some dis

crimination must result. But it is only when the dis

crimination is invidious or when the discrimination

reflects no policy that the State legislative branch must

reorganize itself or be reorganized.”

In Jackman, the plaintiffs had argued as Appellants

here have below that the “Fourteenth Amendment does

require consideration of population differentials re sena

torial districts . . .” (at 645).

On June 22, 1962, a three-judge Federal District Court

reconsidered Baker v. Carr, supra, in light of the Supreme

Court action remanding the case for further proceedings.

See 206 F. Supp. 341. At the time of the reconsideration,

Tennessee had recently enacted legislation reapportioning

the Tennessee Legislature. The Tennessee Constitution,

Article II, Section 6, requires that the “ . . . number of sena

tors which, at the several periods of making the enumera

tion, be apportioned among the several counties or dis

tricts according to the number of qualified electors in

each . . .” . The court found that the apportionment of the

house resulted in the termination of the “most glaring in

equities” , but there still remained some inequities in that

the urban voters were still under-represented. The court

stated (at 345):

“ . . . One reason for the rule embodies in the Con

stitution of the state is to afford a measure of pro

tection to governmental units or subdivisions of the

state not having a sufficient number of voters to equal

the full ratio but yet having a substantial population

and possessing significant and substantial interests in

state legislative policy. Such a state plan for distri

bution of legislative strength, at least in one house of

24

a bicameral legislature, cannot, in our opinion, be

characterized as per se irrational or arbitrary. And

we think the same conclusion follows if this principle

is extended in the same legislative house of a bicam

eral legislature so as to afford substantial representa

tion to smaller counties by classifying or arranging

them in floterial districts. We find no basis for hold

ing that the Fourteenth Amendment precludes a state

from enforcing a policy which would give a measure

of protection and recognition to its less populous gov

ernmental units. . . .”

The court, however, found that the redistricting of the

state senate required by the constitutional mandate was

“devoid of any standard or rational plan of classification” .

The court went on to state (at 346):

“ . . . It creates thirty-three senatorial districts for

election of the constitutionally prescribed number of

thirty-three senators, making no pretense to equality

or substantial equality in numbers of qualified voters.

Nor are the districts created by the Act equal or even

remotely equal in area. There are also wide variations

in the numbers of counties lumped together in the re

spective districts. The conclusion is irrestible that

the apportionment wrought by the 1962 Act with

respect to the Senate can only be described, to use the

apt phrase of Mr. Justice Clark in his concurring opin

ion in this case, as a ‘crazy quilt’. It is inexplicable

either in terms of geography or demography. Neither

can it be explained upon the theory that it seeks to

give equal or substantially equal representation to

governmental subdivisions or units. . . .” (Emphasis

supplied.)

The court, by its reasoning, clearly laid down the rule

that the equal protection of the laws is gratified if at least

one house of the Tennessee Legislature is based upon or

reasonably related to qualified voters without regard to

other factors, when it said (at 349):

25

. . We find in the context of this case that equal

protection requires that such condition be eliminated

and that apportionment in at least one house shall be

based, fully and in good faith, on numbers of qualified

voters without regard to any other factor.”

And, in respect of the proposition stated in Baker v.

Carr, on remand, see Toombs v. Fortson, 205 F. Supp. 248,

257, where the court said:

“Granting the plaintiffs’ petition for declaratory

judgment, we determine and hold that so long as the

Legislature of the State of Georgia does not have at

least one house elected by the people of the State ap

portioned to population, it fails to meet constitutional

requirements.”

As indicated in our Statement of the Case, (infra,

pp. 2-3), not only is the makeup and proper apportion

ment of the Maryland House of Delegates not in question

here nor before this Court, but it has been conceded by

Appellants below to be properly apportioned according to

population, on the basis of the so-called stopgap legisla

tion of 1962. Thus, if this Court is to hold that at least

one house of a state assembly must be elected on a purely

population basis, as have Baker and Toombs, and others,

the present apportionment of the Maryland Senate must,

we submit, be considered in conjunction with a House of

Delegates which, for purposes of this case is properly ap

portioned according to population.

And apropos of Appellants’ position herein, which, de

spite some considerable backing and filling, must be said

to be that the Senate of Maryland should be held to a tight

or strict population standard, only slightly different from

that of the House of Delegates, at the most, and if at all,

the court in Toombs v. Fortson, said (at 257):

26

“It is urged by the plaintiffs here that in its decision

in the case of Scholle v. Hare, supra, 82 S. Ct. 910, the

court in effect decided that constitutional standards

required that not only one House but both Houses of

a bi-cameral legislature be related to population. . . .

“There is some basis for plaintiffs’ argument in this

direction, especially when we consider that in Mr.

Justice Douglas’ dissenting opinion in the United

States Supreme Court’s decision in MacDougall v.

Green, he and his colleagues, Justices Black and

Murphy, seem to have said that the mere fact that

the Federal Constitution itself sanctions inequalities

because of the structure of the United States Senate,

is no justification for a state also to create inequalities

by having similar differences. See dissenting opinion,

Mr. Justice Douglas, MacDougall v. Green, 335 U.S.

281, at page 287, 289. However, that may be, we do not

find any authoritative decision by the Supreme Court

that causes us to require that in order to give the plain

tiff his constitutional rights the state legislature must

be constituted of two Houses, both of which are

elected according to population.”

Scholle v. Hare, 367 Mich. 176, 116 N.W. 2d 350, on re

mand, decided by a badly split court, struck down a

Michigan Senatorial apportionment scheme. As indicated

(Appellees’ Brief, page 14), Mr. Justice Stewart stayed

the judgment on the ground that issues in that case were

“ones that were not decided in Baker v. Carr” .14

In Sweeney v. Notte, .... R.I....... , 183 A. 2d 296, the

Rhode Island Supreme Court struck down a state appor

tionment plan which limited the House of Representatives

to 100 but which secured representation to each munic-

14 Quite correctly, Baker v. Carr, Legislative Reapportionment, at

72 Yale L. J. 968, 1003, footnote 167, concludes that Scholle was

reached by the Michigan Court, on remand, solely on the basis of

State precedent, upon which is superimposed the federal requirement

of equal protection of the laws.

27

ipality, the court holding that such “taken together” re

sults in a denial of equal protection.15

In Moss v. Burkhart, 207 F. Supp. 885, a three-judge

statutory court struck down the Oklahoma apportionment

system, which permitted, inter alia, a disproportionate

ratio of 12 to 1 in the State Senate. The court felt there

that a disparity of ten to one in the voting strength between

electoral districts made out a prim,a facie case for invidious

discrimination and called for strict justification (at 891).16

In Sincock v. Duffy, 215 F. Supp. 169, a statutory three-

judge District Court (by a vote of 2 to 1) struck down a

Delaware apportionment system, which, after a 1963 Con

stitutional amendment, still contained a disproportion of

15 to 1 in respect of the State Senate. The court concluded,

inter alia, that insofar as the State House of Representa

tives, which struck a ratio of 12 to 1 was concerned, the

15 In The Significance of Baker v. Carr for Indiana, at 38 Indiana

L. J. 240, comments that the court in Sweeney, as in Scholle on

remand, assume that constitutionality is solely a question of per

centages and ratios, rather than a broader question of rationality.

16 In respect of Moss, it is not clear from whence comes the au

thority to strike such a positive ratio, as, e.g., 10 to 1. And Moss

further seems to fall into the error of Scholle in superimposing a

federally protected right upon a state requirement. (See footnotes 14

and 15.) All of this lends credence to the comment in The Signifi

cance of Baker v. Carr for Indiana, 38 Indiana L. J. 252, 254, that

of the courts that have decided apportionment controversies since the

historic Baker v. Carr decision, only five have determined them ac

cording to the traditional standards of the equal protection clause,

namely, Sobel v. Adams, supra; Caesar v. Williams, supra; Maryland

Committee for Fair Representation v. Tawes, supra; Baker v. Carr,

on remand, supra; and Lisco v. McNichols, 206 F. Supp. 471 (striking

down Colorado’s apportionment system). All others “ . . . have gone

beyond the traditional standards of the equal protection clause sug

gested by the Baker decision, some in an apparent effort to read into

that clause the court’s own notion of what is and what is not a demo

cratic system of legislative apportionment. The Baker decision does

not require courts to choose between competing theories of rep

resentation and hold that apportionment systems need be based upon

the population standard.” (Emphasis supplied.)

28

apportionment basis must be one of population, citing Gray

v. Sanders, supra. The court further concluded that none

of the “area” and other considerations discussed by it

should permit any wide deviation from the principle of

population representation in the apportionment of the

Delaware State Senate. Judge Wright, in concurring, ob

serves that the Senate must be based substantially on

population. Judge Layton, dissenting on the substantial

question of apportionment of the Senate, stated that he

could “find nothing constitutionally wrong in the makeup

of a State legislature composed of a Lower House whose

members are elected upon a strict population basis and an

Upper House whose members are elected in equal num

bers from each county . . .” .

“Since the so-called federal system has withstood

175 years of stress and strain in the national political

arena. I can see no valid reason for interfering with the

composition of a State Legislature modeled exactly on

it.” (at 196, 197)

In Mann v. Davis, 213 F. Supp. 577, a split three-judge

District Court struck down, inter alia, the Virginia Senate

apportionment system, which results in a disproportion

in ratio of considerably less than Maryland’s, the consid

eration being, it appears, almost solely of population.

Judge Hoffman, dissenting (at 586, 591, 592), states:

“In my judgment the decision of the majority places

too much emphasis upon the weighted vote of one

county, city, or district as contrasted with the

weighted vote in another county, city or district. . . .

When we consider other states, such as New York,

Maryland and Hawaii, where the concentration of

population is in one major city, it may be inappro

priate to rely so heavily on population.”17

17 In this connection, Scholle v. Hare, on remand; Mann v. Davis,

together with Moss v. Burkhart, supra; Sweeney v. Notte, supra;

and Levitt v. Maynard, 104 N.H. 243, 182 A. 2d 897, would seem

29

Apparently, however, Judge Edmund W. Hening, Jr.

of the Richmond Circuit Court, in upholding Virginia’s

legislative redistricting acts by his order of September 24,

1963, differs radically in his conclusions from the majority

in Mann v. Davis, supra. (See Washington Post and Times

Herald, September 25, 1963.)

The consensus of judicial thinking, to date, as illustrated

by the foregoing cases would certainly demonstrate, we

think, that the rationality of any state apportionment is

not determined solely by applying the “one man — one

vote” , purely populative theory. On the contrary, it recog

nizes the applicability of other substantial factors which,

when applied to the Maryland Senate scheme, supports

its constitutionality.

Maryland, appropriately given the cognomen of “America

in Miniature” , is unusually diverse, geographically and

economically. Stretching from the Atlantic Ocean to its

western mountains bordering West Virginia, it contains

vast climatic differences. The Eastern Shore of Maryland,

which is physically set apart from the rest of the State,

is economically geared to agriculture, sea-food producing

pursuits and to coastal recreation. Its climate is more

temperate than the western regions of the State. Southern

Maryland’s economy is also agricultural with a strong de

pendence upon tobacco raising. The two principal popu

lation centers are found within the central portion of the

State. One of these centers, composed of Prince George’s

and Montgomery Counties, partially circumscribes and is

contiguous to the District of Columbia. The portions of

these two counties nearest the District are suburban in

to have departed from traditional equal protection standards by

holding that reapportionment systems must be based upon popu

lation. See The Sianificance of Baker v. Carr for Indiana, 38 Indiana

L. J. 240, 250.

30

nature. The southern portion of Prince George’s and the

western part of Montgomery are rural. The other popula

tion center includes Baltimore City and the surrounding

contiguous portions of Baltimore and Anne Arundel

Counties.

Whereas Baltimore City is urban in character, its two

neighboring counties are not; like Prince George’s and

Montgomery Counties, they possess both suburban and

rural attributes. The economy of mountainous western

Maryland is largely devoted to agriculture, mining and

timber. Numerous of its sections are sparsely populated.

While Appellants bemoan the ways in which the four

most populous counties of the State and Baltimore City

allegedly have languished and suffered under malappor

tionment, common experience points to the contrary. At

the outset, even on Appellants’ theory, Baltimore City in

sofar as the State Senate is concerned, is said to be over-

represented. (See Appellants’ Brief, page 30.) Despite

overrepresentation, still, presumably, it suffers. If Balti

more and other large cities suffer from decay, it must be

laid to a great many factors other than malapportionment:

migration to suburbs of both population and to an extent

industry, loss of tax base and source of public finance, etc.

Certainly, Baltimore and the populous counties have had

no difficulty in obtaining urban renewal authority, although

the latter hardly need it (with a few isolated exceptions in

certain municipalities in those counties).

It must be said, despite the “cancer” of malapportion

ment of which the Appellants speak, that Montgomery,

Baltimore, Prince George’s and Anne Arundel Counties

are the most wealthy, prosperous and progressive counties

in the State. Partly, this may be laid to home rule, under

which Baltimore and Montgomery Counties operate and

31

which Prince George’s and Anne Arundel Counties are cur

rently seeking to achieve. Both Baltimore and Mont

gomery Counties have wide taxing and other powers, with

in their express powers. The latter county, within very

recent memory, enacted its own public accommodations

ordinance and is also included under the Statewide public

accommodations act.18

Appellants here seem to make much of the rights of

people vis-a-vis people, but what they argue, in essence,

is mathematics, formulae, proportions and figures. As Pro

fessor Bickel puts it, in Reapportionment & Liberal Myths,

Commentary, June, 1963 (pages 490-491):

“All we have been given are plays on words, plays

on statistics, and meaningless figures arbitrarily picked

out of thin air.

* ❖ * * * *

“What does it mean to juggle ratios or to bewail the

fact that 20 per cent of a state’s population can elect

a majority of its legislature, X percent of the popu

lation of the United States can elect the President, and

X — 10 per cent can elect the Senate? These are not

facts; such things never happen.”

Appellants complain of gross deprivation while at the

same time the counties most said to be suffering under

malapportionment of the State Senate have prospered as

have no others in the State. They lump together Baltimore

City with the populous counties because the figures look

18 Indeed, it is the very existence of broad home rule powers made

available to the counties under Article X I-A of the Maryland Con

stitution and implemented by Article 25A of the Annotated Code

of Maryland which mitigate whatever disadvantage these counties

may incur in the Maryland Senate. Experience has shown that it

is the suburban counties that are most likely to avail themselves of

the home rule option, as indicated above. Home rule counties need

not return to the legislature for many of those legislative authorizations

which non home rule counties can obtain only biennally at Annapolis.

32

better; actually, the city and those counties (excepting

Baltimore) have little in common. The four counties in

volved here have both heavily populated and suburban-

type areas and sparsely settled agricultural regions. The

city dwellers of Baltimore, with their port authority and

steel production are confronted with problems of a charac

ter completely different from those facing the four subur

ban counties. These urban problems, which involve large

expenditures of funds, concern themselves with adequate

standards of health, employment and housing for the city

residents, many of whom are of the lower economic and

cultural class. The suburban counties, however, are faced

with problems of prosperity, which, fortunately, do not in

volve the same expenditure of public funds. Planning,

zoning, water and sewer, subdivision control and ade

quate park and new school facilities command the atten

tion of the more prosperous suburban dweller. Thus, it

may fairly be said that the suburbs are peopled by the

“haves” and Baltimore City by the “have nots” . Yet all

are combined together for purposes of Appellants’ com

parisons.

If population, in the apportionment of the Maryland

State Senate, is to be the sole or “strongly dominant”

criterion, as Appellants insist, then it becomes very prob

able that not only the rural counties of the State, but

rural areas of the populous counties, in their turn, will be

come, in effect, malapportioned, with the specialized in

terests of those rural areas subordinated to the interests of

the more densely industrialized and urbanized areas of

those same counties. The State has a legitimate concern in

those interests and the State through apportionment should

be permitted to strike a balance, we submit, to protect them

both. As Professor Bickel further states it, in Reapportion

ment & Liberal Myths, Commentary, June, 1963 (page

486):

33

. . most, if not all, malapportionments favor rural

interests over urban, allocate more strength propor

tionately to sparsely populated areas than to densely

populated ones, and other smaller discriminations

within these large ones. This may be undesirable, but

who can say it is irrational? Is it more irrational

than a farm policy that favors farmers or an anti

trust policy that favors small enterprise?”

And, as stated by James Kilgore Edmundson, Jr., Legis

lative Reapportionment, Baker v. Carr, 65 West Virginia

L. Rev. 129, 141, 142:

. . equal representation does not necessarily mean

good government___For ‘local prejudices’ are spawned

not only in rural areas . . .”

Jo Desha Lucas, in his Legislative Apportionment and

Representative Government: The Meaning of Baker v. Carr,

61 Mich. L. Rev. 711, 804, states:

“It is to be hoped that . . . the advantages of sim

plicity will not prompt adoption of a standard of

mathematical equality based solely upon population,

thus ending centuries of experimentation with the

design of democratic institutions which will accom

modate within the same unit of government a wide

variety of interest groups without subjecting all to

absolute domination by a close majority which is geo

graphically concentrated and highly organized.”

Clearly, interests other than population must be taken

into account in the apportionment of the Maryland Senate,

where, as in this case, the apportionment of the House of

Delegates is not under attack, nor in question, and is, in

fact, insofar as the record in this case is concerned, prop

erly and constitutionally, though not perfectly, appor

tioned.19

19 One wonders whether population is a proper criterion in any

event; should voter registration be considered ?

34

Lisco v. McNichols, supra, recognizes as a relevant fac

tor representation of industrial interests; Sobel v. Adams,

supra, recognizes representation of general regional in

terests; Caesar v. Williams, supra, recognizes protection of

sparsely settled areas; Levitt v. Maynard, 104 N.H. 243, 182

A. 2d 897, recognizes as “rational” wealth and the propor

tion of total taxes paid by a district; WM.C.A., Inc. v.

Simon, supra, recognizes a state apportionment plan “of

historic origin” as “not irrational” , which “clearly gives

weight to population within the state’s counties and which

forms a basis for the ingredient of area, accessibility and

character of interest” , and Tyler, Court versus Legislature,

27 Law and Contemporary Problems, 390, 391, 393, recog

nizes economic interests.

The court below (R. 167, 168), in upholding the Mary

land Senate apportionment plan on historical grounds,

quite irrespective of population, did so on the rationale

that representation on a county basis, with some modifica

tion in respect of Baltimore City, was deeply rooted in

Maryland traditions and history, predating, even, the ex

istence of the Federal Union. In fact, the court found that

the United States Senate was modeled upon the Maryland

plan (See R. 166). See Journal of the Constitutional Con

vention, G. P. Putnam Sons, 1903, page 202.

Starting from Appellants’ beginning point, namely, that

population must be the sole or dominant criterion in ap

portionment of the Senate, no other consideration or stand

ard can then be accepted (see Appellants’ Brief, page 72).

However, Appellees submit that, on the authority cited

hereinbefore, under the Maryland plan, history and tra

dition may be found, by this Court, to be a rational basis

for the apportionment now under attack. Jerold Israel,

On Charting a Course through the Mathematical Quag

mire: The Future of Baker v. Carr, 61 Mich. L. Rev. 107,

143, comments that a court:

35

“should not, as in the Scholle decision (on remand)

reject all bases for apportionment schemes other than

population as arbitrary and therefore insist upon ‘prac

tical equality’ of representation. Neither should it,

although most lower courts have done so, permit the

use of factors other than population only insofar as

population is still retained as the predominant factor.

Both of these approaches can be justified only on the

basis of a fundamental political value in our society

which demands total equality of representation, and

. . . sustaining the presence of such a fundamental

concept necessarily involves the interpretation of the

‘republican form of government’ guaranteed to the

states under Article IV, Section 4.”

As the Solicitor General of the United States said, in

his address before the Tennessee Bar Association on June

8, 1962 (see Current Constitutional Issues, page 3):

. . History is a powerful influence in constitu

tional law . . . it would not surprise me greatly if the

Supreme Court were ultimately to hold that if seats

in one branch of the legislature are apportioned in

direct ratio to population, the allocation of seats in

the upper branch may recognize historical, political

and geographical subdivisions provided that the de