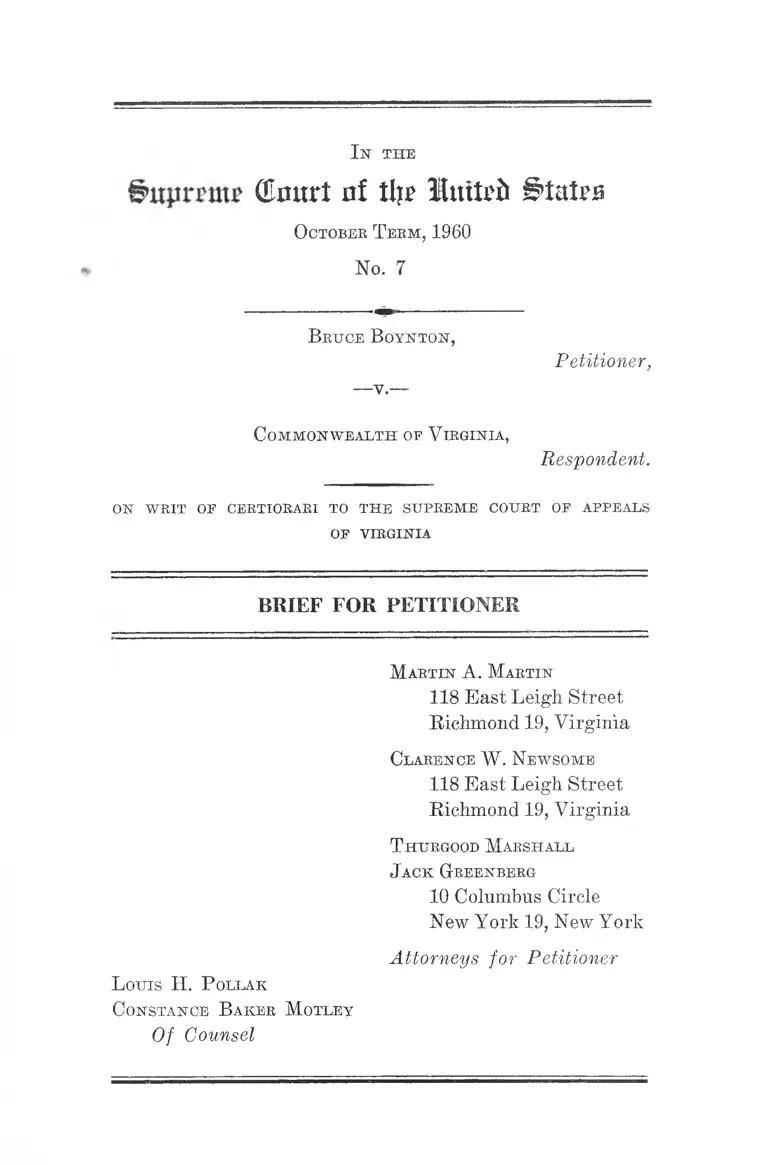

Boynton v. Virginia Brief for Petitioner

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1960

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Boynton v. Virginia Brief for Petitioner, 1960. 0e57a4a2-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2221f8a5-2431-4deb-a17f-4e24f5444675/boynton-v-virginia-brief-for-petitioner. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

(Eourt nf tl|p luttTfc S ta irs

October T erm, 1960

No. 7

Bruce Boynton,

Petitioner,

—v.—

Commonwealth op Virginia,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OP APPEALS

OP VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Martin A. Martin

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

Clarence W. Newsome

118 East Leigh Street

Richmond 19, Virginia

T hurgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Petitioner

Louis H. P ollak

Constance B aker Motley

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below ......-.................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................... - 1

Questions Presented ......... ........................................ 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved .... 2

Statement ...................................................... —.......... 3

Summary of Argument........ ...................................... 5

Argument ................................................— ........ 6

Introductory ............................................. -......... 6

The statute involved .................................- .... 6

Issues presented by the statute as applied .... 8

I. The decisions below conflict with principles estab

lished by decisions of this Court by denying peti

tioner, a Negro, a meal in the course of a regu

larly scheduled stop at the restaurant terminal

of an interstate motor carrier and by convicting

him of trespass for seeking nonsegregated dining

facilities within the terminal .................... .... ..... 14

II. Petitioner’s criminal conviction which served

only to enforce the racial regulation of the bus

terminal restaurant conflicts with principles

established by decisions of this Court, and there

by violates the Fourteenth Amendment ............ 22

Conclusion ............................................ -.................. - 26

ii

T able oe Cases

page

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249 .............................. 11

Bibb v. Navajo Freight Lines, 359 U.S. 520 .... ......... 15

Bob~Lo Excursion Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28 ...... 21

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 ................................ 21

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. 18187, July

12, 1960, Fifth Circuit ......................................... 12,18, 24

Boykin v. State, 40 Fla. 484, 24 So. 141 (1898) .......... 8

Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U.S. 622 .......................... 10, 25

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F.2d 879 (4th Cir. 1951),

cert, den., 341 U.S. 941 ....... ............... ................ . 12,17

Commonwealth v. Israel, 31 Va. (4 Leigh) 675 (Va.

Gen. Ct., 1833) ...... ................................................... 7

Commonwealth v. Richardson, 313 Mass. 632, 48 N.E.

2d 678 (1943) ........................................................... 8

Re Debs, 158 U.S. 564 ................................................ 16

Dye v. Commonwealth, 48 Va. (7 Grat.) 662 (Va.

Gen. Ct., 1851) .......................................................... 7

Falkingham v. Fregon, 25 V.L.R. 211, 21 A.L.T. 123

(1899) ...... 9

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Union, Washington Su

perior Court, 45 Lab. Rel. Ref. Man. 2334 (1959) .... 12

Greenaway v. Hunt and Weggery [1922] N.Z.L.R.

53 [1921], G.L.R. 673 .............................................. 9

Gripps v. Gripps, 20 Tas. L.R. 47 (1924) .................. . 9

Hall v. Commonwealth, 188 Va. 72, 49 S.E.2d 369

(1948), app. dism. 335 U.S. 875 ............................ 6

Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U.S. 485 ......................................... 16

Henderson v. Commonwealth, 49 Va. (8 Grat.) 708

(Va. Gen. Ct., 1852) ................................................ 7

Ill

PAGE

Henderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816 - ............15,19, 20

James v. Butler, 25 N.Z.L.R.C.A. 653 (1906) .......... 9

Jones v. United States,-----U.S.------ (1960) .......... 13

Keys v. Carolina Coacli Co., 64 M.C.C. 769 (1955) .... 20

Kirsehenbaum v. Walling, 316 U.S. 517..................... 16

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501............................10,12, 24

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141.............................. 10

Maryland v. Williams, 44 Lab. Eel. Kef. Man. 2357

(1959) .............. .......-..................-......-...... ....-......... 11

Miller v. Harless, 153 Va. 228, 149 S.E. 619 (1929) .... 7

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U.S. 8 0 .............. 19

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373 ............... 14,15,19, 20, 21

Murphey v. State, 115 Ga. 201, 41 S.E. 685 (1902) .... 8

Myers v. State, 190 Ind. 269, 130 N.E. 116 (1921) ..... 8, 9

N.L.R.B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F.2d

258 (8th Cir. 1945) ....... .................... -.................... H

N.L.R.B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U.S. 240 (1948) 12, 25

N.Y. N.H. & H. R. Co. v. Nothnagle, 346 U.S. 128...... 16

People v. Barisi, 193 Mise. 934, 86 N.Y.S.2d 277

(1948) .........................-........... • ...............-.......... 12

People v. Miller, 344 111. App. 574, 101 N.E.2d 874

(1951) ...... ............. .............. .......... -........................ 9

People v. Stevens, 109 N.Y. 159, 16 N.E. 53 (1888) .... 8

R. v. Blake, et al., 3 Burr. 1731, 47 E.R. 1070 (1765) 9

R. v. Phiri (4) S.A. 708 (T) (1954) ........................... 9

R. v. Storr, 3 Burr. 1698, 97 E.R. 1053 (1765) .......... 7, 9

R. v. Wilson, 8 Term Rep. 357, 101 E.R. 1432 (King

ston Assizes, 1799) .................................................. 9

Republic Aviation, Inc. v. N.L.R.B., 324 U.S. 793 ..... 11, 25

IV

PAGE

Rex v. Storr, 3 Burr. R. 1698 ..................................... 7

Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 TJ.S. 218 ...... 16

Ryan v. Stanford, 15 N.Z.L.R.C.A. 390 (1897) ........ 9

Secretary of Agriculture v. Central Roig Refining

Co., 338 U.S. 604 ..................................................... 21

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 .................................. 11, 22

Southern Pacific Co. v. Arizona, 325 U.S. 761.......... 14,19

Sprout v. South Bend, 277 U.S. 163............................ 16

Stafford v. Wallace, 258 U.S. 495 .............................. 15

State v. Clyburn, 247 N.C. 455, 101 S.E.2d 295 (1958) 9

State v. Cockfield, 15 Rich. (49 S.C.L.) 53 (1867) ..... 9

State v. Larason, 72 Ohio L. Abs. 211, 143 N.E.2d 502

(1956) ...................................................................... 9

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U.S. 218, 228 16

United Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F.2d 593 (D.C.

Cir. 1956) (reversed on other grounds) 357 U.S.

357 ........................................................................... 11,25

Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F.2d 949 (6th

Cir. 1949) ................................................................ 12,17

Wiggins v. State, 119 Ga. 216, 46 S.E. 86 (1903) ...... 8

Williams v. Howard Johnson Restaurant, 268 F.2d

845 (4th Cir., 1959) ............................................ 23

Wise v. Commonwealth, 98 Va. 837, 36 S.E. 479

(1900) ...................................................................... 7

United States Statutes and Constitutional P kovisions

United States Constitution, Article I, Sec. 8, cl. 3 ..... 2, 8,

12,13

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment 2

28 U.S.C. Sec. 1257(3) ................................................ 2

V

PAGE

49 U.S.C. See. 3(1) ...................................................... 19

49 U.S.C. See. 303(19) ................................................ 20

49 U.S.C. Sec. 316(d) ......... ...................................... 5,19

State Statutes

Alabama Code 1940, Title 14, See. 426 ..................... 9

Alaska Laws Annot., 1958, Sec. 65-5-112................... 9

Arkansas Rev. Stats., 1959, Secs. 71-1801, 1802, 1803 9

California, West’s Code Annot., 1958, Tit. 14, Sec. 602 8

Connecticut, Gen. Stats. Rev., 1958, Sec. 53-103 ........ 9

Delaware Code Annot., 1953, Tit. 11, Sec. 871.......... 9

District of Columbia Code Annot., 1956, Sec. 22-3102 9

Florida, West’s Stats. Annot., 1948, Tit. 44, See.

821.01 .......................... ....................................'......... 8

Georgia Annot. Code, 1959, Sec. 26-3002 ................... 8

Hawaii Rev. Laws, 1955, Sec. 312-1................ 9

Illinois Rev. Stats., 1959, Tit. 38, Sec. 565 ................. 8

Indiana, Burns Stats. Annot., 1956, Tit. 10, Sec. 4506 8

Kentucky Rev. Stats., 1959, Sec. 433-380 ................. 8

Maine Rev. Stats., 1959, c. 131, Sec. 39....................... 8

Maryland Annot. Code, 1957, Art. 27, Sec. 577 .......... 8

Massachusetts, Michie’s Annot. Laws, C. 266, Sec. 120 8

Michigan Stats. Annot., 1954, Sec. 28-820(1) .......... 9

Minnesota Stats. Annot., 1947, Sec. 621.57 ............... 9

Mississippi Annot. Code, 1942, Tit. 11, Sec. 2411...... 8

VI

PAGE

Nebraska Rev. Stats., 1957, Tit. 28, Sec. 589 .............. 8

Nevada Rev. Stats., 1957, Sec. 207.200 ...................... 9

New Hampshire Rev. Stats. Annot., 1955, Sec. 572:50 9

New Jersey Annot. Stats., 1957, Tit. 2A, Sec. 170-31 8

New York, McKinney Laws, Art. 182, Sec. 2036 ....... 8

North Carolina Gen. Stats., Tit. 14, Sec. 134.............. 9

Ohio, Page’s Rev. Code Annot., Sec. 2902.21 .............. 8

Oklahoma, West’s Stats. Annot., 1958, Tit. 21, Sec.

1353 .................... ..................................................... 8

Oregon Rev. Stats., Sec. 164.460 ................................ 9

South Carolina Code of Laws, 1959, See. 16-386 ...... 9

Virginia Code Sec. 18-225 ............................. ..... ......1, 2,4, 8

Washington Rev. Code, 1957, Sec. 8.83.060 ............... 9

West Virginia Code, 1955, Sec. 5974 .......................... 8

Wyoming, Michie’s Stats. Annot,, 1957, Sec. 6-226 .... 9

Statutes oe Commonwealth Countries

Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act of 1945,

Sec. 9, para. 9, as provided by Sec. 29, para, e of

Native Laws Amendment Act No. 36 of 1957

(South Africa) ........................................................ 9

New Zealand, Police Offences Amendment Act (No.

2) No. 43 of 1952, Sec. 3 ........................................... 9

Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act, No. 52 of 1951,

Sec. 1 (South Africa) ............................................ 9

72 South Af. L.J. 125 (1955)....................................... 9

V ll

PAGE

Tasmania, Trespass to Lands Act, 1862 — ............... 9

Victoria, Australia, Police Offences Act, No. 6337 of

1958, Sec. 20 ...................... 9

Otheb A uthorities

63 C.J.S. 1075 ............................................................ 7

72 South Af. L.J. 125 (1955) ................................... 9

H.B. 1112, Act No. 497, 1960 General Assembly of

Georgia .................................................................... 8

Hitchcock’s Mass Transportation Directory (1959-60

ed.) 205, 242 ............................................................. 22

Op. Atty. Gen. of Florida 649, 1953-54 ..................... 8

I n the

Cfkmrt nt tip IniPit States

October T erm, 1960

No. 7

Bruce B oynton,

Petitioner,

—y.—

Commonwealth of Virginia,

Respondent.

on writ of certiorari to the supreme court of appeals

OF VIRGINIA

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER

Opinions Below

No opinion was rendered in this case by the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia when it denied the petitioner

a writ of error to the judgment of the Hustings Court of the

City of Richmond on the 19th day of June, 1959. No opinion

was rendered by the Hustings Court of the City of Rich

mond on the 20th day of February, 1959, when it found

petitioner guilty of a violation of §18-225 of the Code of

Virginia, 1950, as amended.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Appeals of

Virginia was rendered on the 19th day of June, 1959 and

2

stay of execution and enforcement of the judgment of said

Court was granted on the 24th day of July, 1959 staying

the execution and enforcement of same until the 17th day of

September, 1959, unless the case would before that time be

docketed in this Court in which event enforcement of said

judgment should be stayed until the final determination of

this case by this Court. On February 23, 1960, this Court

granted a petition for writ of certiorari from the Supreme

Court of Appeals of the Commonwealth of Virginia. The

jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28 U.S.C. §1257(3).

Questions Presented

1.

Whether the criminal conviction of plaintiff, an inter

state traveler, for refusing to leave an interstate bus ter

minal restaurant where he sought refreshment at a regu

larly scheduled stop in the course of his interstate journey

and was barred solely because of his race, is invalid as a

burden on interestate commerce in violation of Article I,

§8, Clause 3 of the United States Constitution.

2 .

Whether said conviction violates the due process and

equal protection clauses of the 14th Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States.

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves:

Article I, §8, and the due process and equal protection

clauses of the XIV Amendment of the Constitution of the

United States.

§18-225 of the Code of Virginia of 1950. This statutory

provision is set forth in the Statement, infra, p. 4.

3

Statement

At 10:40 P. M. on December 20th, 1958, Bruce Boynton,

petitioner, stepped off a Trailways bus from Washington,

D. C., at the Trailways Bus Terminal in Richmond, Va., for

a forty minute layover. Petitioner, a Negro student at the

Howard University School of Law in Washington, was hun

gry and anxious to get something to eat before reboarding

the bus to continue on to his home in Selma, Alabama, by

way of Montgomery (R. 27-28).

He first looked into a small restaurant and noticed that

it was crowded with colored patrons. Since his time was

limited, he went on to another restaurant within the ter

minal, which was practically empty, adjacent to the 'wait

ing room (R. 28). He entered and sat on a vacant stool

at the counter. A white waitress immediately approached

and informed him that she had orders not to serve people of

his race. She advised him to use the colored facilities.

Petitioner explained that he would like to be served before

his bus, which was scheduled to leave shortly, departed. To

insure quick service he ordered a prepared sandwich and a

cup of tea. But the waitress disregarded his order, de

parted for a while and returned to repeat that it was cus

tomary not to serve Negroes in that particular restaurant

(R. 29).

Petitioner asked to speak to someone who could wait on

him, pointing out that he was an interstate passenger with

a cross-country ticket purchased in Washington, D. C. (R.

29). At this point the assistant manager intervened “to

explain to him the situation” (R. 21) and to demand that

petitioner leave. Petitioner refused to move. The assistant

manager’s response was to have petitioner arrested (R. 21,

29). Petitioner’s baggage was removed from the bus on

which he had expected to continue his journey, and peti-

4

tioner himself was taken away in a patrol wagon, charged

with a violation of §18-225 of the Code of Virginia of 1950

as amended, which provides:

“If any person shall without authority of law go

upon or remain upon the lands or premises of another

after having been forbidden to do so by the owners,

lessee, custodian or other person lawfully in charge

of such land, or after having been forbidden to do so

by sign, or signs posted on the premises at a place

or places where they may be reasonably seen, he shall

be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon convic

tion thereof shall be punished by a fine of not more

than $100.00 or by confinement in jail not exceeding

thirty days, or by both such fine and imprisonment.”

The bus terminal was owned and operated by Trailways

Bus Terminal, Inc. (R. 9-17). The restaurants therein were

built into the terminal upon its construction and leased

by Trailways to Bus Terminal Restaurant of Richmond,

Inc. (R. 9-17). The lease gave exclusive authority to the

lessee to operate restaurants in the terminal, required that

they be conducted in a sanitary manner, that sufficient food

and personnel be provided to take care of the patrons, that

prices be just and reasonable, that equipment be installed

and maintained to meet the approval of Trailways, that

lessee’s employees be neat and clean and furnish service

in keeping with service furnished in an up-to-date, modern

bus terminal; prohibited the sale of alcoholic beverages on

the premises; and permitted cancellation of the lease upon

the violation of any of its conditions (R. 9-17).

Petitioner was convicted in the Police Court of the City

of Richmond and fined $10.00, which conviction was ap

pealed to the Hustings Court of the City of Richmond

5

which affirmed (E. 31).1 Petition for writ of error to the

Supreme Court of Appeals was rejected, the effect of which

was to affirm the judgment of the Hustings Court (E. 32).

The affirmance by the Supreme Court of Appeals of Vir

ginia, appears in the Eecord at p. 32. In the Elustings Court

of the City of Eichmond petitioner objected to the criminal

prosecution on the grounds that it contravened his rights

under the Commerce Clause of the United States Constitu

tion (Article 1, Section 8) and the Interstate Commerce Act

(Title 49 U.S.C., Section 316(d)) and that he was thereby

denied due process and equal protection of the laws secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Con

stitution (E. 6-7). Said objections were renewed by notice of

appeal and assignment of error to the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia (E. 5). These defenses, however, as

aforesaid, were rejected at all stages of the litigation with

out opinion. On February 23, 1960 this Court granted

petitioner’s petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme

Court of Appeals of Virginia.

Summary of Argument

The arrest and conviction of petitioner burdened inter

state commerce. That the terminal in question is stationary

does not exempt the burden there effected from the gen

eral rule. Even if petitioner’s arrest and conviction for

insisting upon nonsegregated dining service might some

how be viewed as “private action,” the Commerce Clause

also forbids privately imposed burdens on interstate com-

1 Petitioner, at the time of arrest, was a law student at Howard Uni

versity. Since then he has been graduated, and on February 16, 1960, took

the Alabama bar examination. While others wdio took the examination with

him already have been admitted to the bar, petitioner’s status has not yet

been declared. He is under an investigation, he has been informed, which

concerns this conviction.

6

merce. But the arrest and conviction here supply requisite

state action should that be required. Congress has ex

pressed no specific intent concerning an arrest and con

viction like petitioner’s, but should congressional intent

be found in the Motor Carriers Act, that Act, read in a

context of relevant constitutional law, indicates intent that

this burden not be permitted.

Judicial enforcement of private racial discrimination

violates the 14th Amendment. This has been made clear,

among other places, in cases of arrest for exercise of con

stitutional rights in public places although possessory in

terest to these places actually may lie with private indi

viduals, or corporations. Petitioner’s conviction is not a

reasonable exercise of police power necessary to maintain

law and order. In fact, petitioner’s act would not have been

criminal at common law, in almost all of the other states of

the Union, in England, or in the Commonwealth countries,

except South Africa where similar law is directed solely at

Natives.

Argument

Introductory

The statute involved

Virginia’s police, in the circumstances related above, by

application of a trespass statute, have halted petitioner’s

interstate journey, forced him to disembark and remove his

baggage from the interstate bus which carried him from

Washington, D. C. en route to his home in Alabama, and

have brought him before the Virginia courts which have

adjudged him guilty of crime. The statute is set forth

supra, p. 4.

This statute apparently has been interpreted by the

Virginia courts but once. Hall v. Commonwealth, 188 Va.

7

72, 49 S.E. 2d 369 (1948), app. dism. 335 U.S. 875, upheld

its applicability to Jehovah’s Witnesses who persisted in go

ing past the receptionist of a private apartment house into

its corridors to solicit tenants, contrary to regulations, con

curred in by tenants and management, which required in

vitation of a tenant for permission to enter the hallways.

The Supreme Court of Virginia, holding the regulation

“valid and reasonable,” 188 Va. at 90, 49 S,E.2d at 378,

ruled that state and federal constitutional rights of free

speech, press, and assembly had not been denied.

There are other Virginia trespass cases, involving similar,

earlier statutory law, and statements of the common law of

Virginia, which help further place this statute in a con

text of the State’s law. The general rule seems to be, as at

English common law, that an intrusion made under claim

of right, which may give rise to civil suit, is not a misde

meanor. Wise v. Commonwealth, 98 Va. 837, 36 S.E. 479

(1900); Dye v. Commonwealth, 48 Va. (7 Grat.) 662 (Va.

Gen. Ct., 1851); and that before criminal liability attaches

there must be a breach of the peace, Henderson v. Common

wealth, 49 Va. (8 Grat.) 708 (Va. Gen. Ct., 1852) ;2 Com

monwealth v. Israel, 31 Va. (4 Leigh) 675 (Va. Gen. Ct.,

1833); Miller v. Harless, 153 Va. 228, 149 S. E. 619 (1929).3

2 See Henderson v. Commonwealth, 49 Va. (8 Grat.) 708, 710 (Va. Gen.

Ct., 1852) : “I t is abundantly clear that the mere breaking and entering the

close of another, though in contemplation of law a trespass committed vi et

armis, is only a civil injury to be redressed by action; and cannot be treated as

a misdemeanor to be vindicated by indictment or public prosecution. But when

it is attended by circumstances constituting a breach of the peace, such as

entering the dwelling house with offensive weapons, in a manner to cause

terror and alarm to the family and inmates of the house, the trespass is

heightened into a public offense, and becomes the subject of a criminal prose

cution.” Citing Hex v. Storr, 3 Burr. 1698. See statement of the general

rule in 63 C.J.S. 1075, to the same effect.

3 In many states there apparently are no statutes under which Boynton

would have been convicted for trespass: See Arizona, Colorado, Idaho, Iowa,

Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, Pennsyl-

8

But, as indicated above, such holdings have not been em

ployed by Virginia in its sole interpretation of §18-225.

Issues Presented by the Statute as Applied

Petitioner raises two principal constitutional defenses,

the Commerce Clause (Article I, §8, cl. 3), and the Equal

Protection and Due Process Clauses (Fourteenth Amend

ment), against the asserted power of Virginia to convict

him under this statute in the circumstances of his interstate

vania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Vermont, and

Wisconsin. Cf. the following states where statutes probably would not be

applicable to Boynton’s acts: California, West’s Code Annot., 1955, Tit. 14,

Sec. 602, para. 1 (entering and occupying structures) ; Kentucky, Rev. Stats.,

1959, Sec. 433.380 (trespass hindering conduct of commerce) ; Maine, Rev.

Stats., 1959, c. 131, Sec. 39 (willful entry on land commercially used, but

referring to land without buildings); Maryland, Annot. Code, 1957, Art. 27,

Sec. 577 (wanton entry after warning involving high degree of criminal

in ten t); Mississippi, Annot. Code, 1942, Tit. 11, Sec. 2411 (remaining on

inclosed land of another after warning) ; Nebraska Rev. Stats., 1956, Tit. 28,

Sec. 589 (refusal to depart from enclosure after request) ; New Jersey, Annot.

Stats., 1951, Tit. 2A, Sec. 170-31 (trespass on lands; totally rural context);

Oklahoma, West’s Stats. Annot., 1958, Tit. 21, Sec. 1353 (intrusion on lot

or piece of land; not in sense of buildings) ; and West Virginia, Code, 1955,

See. 5974 (entry upon inclosed lands after being forbidden).

In other states where perhaps applicable trespass laws do exist, it is ques

tionable whether under existing interpretations he would have been convicted,

for clearly he was in the Trailways Terminal under a elaim of right, which

ordinarily exempts the intrusion from the category of criminal trespass. There

are no reported eases in these states which would differentiate between a claim

of constitutional or other federal right and one of traditional “property”

right. Such differentiation would, of course, raise constitutional questions of

equal protection. See Florida, West’s Stats. Annot., 1944, Tit. 44, Sec. 821.01

as interpreted in Boykin v. State, 40 Fla. 484, 24 So. 141 (1898) and 1953-54

Op. Atty. Gen. 649. In Georgia, until recently the law was stated by: Georgia,

Annot. Code, 1959, Sec. 26-3002 as interpreted in Murphey v. State, 115 Ga.

201, 41 S.E. 685 (1902) and Wiggins v. State, 119 Ga. 216, 46 S.E. 86 (1903);

this now has been superseded by H.B. 1112, Act No. 497, 1960 General As

sembly (trespass after refusal to leave) ; Indiana, Burns Stats. Annot., 1956,

Tit. 10, Sec. 4506 as interpreted in Myers v. State, 190 Ind. 269, 130 N.E.

116 (1921) ; Massachusetts, Michie’s Annot. Laws, C. 266, Sec. 120 as inter

preted in Commonwealth v. Richardson, 313 Mass. 632, 48 N.E.2d 678 (1943) ;

New York, McKinney Laws, Art. 182, Sec. 2036 as interpreted in People v.

Stevens, 109 N.Y. 159, 16 N.E. 53 (1888); Ohio, Page’s Rev. Code Annot.,

9

journey related above. This conflict manifests once more

the recurring theme which juxtaposes in the courts claims

of federally protected personal liberty against state en-

See. 2902.21 as interpreted in State v. Larason, 72 Ohio L. Abs. 211, 143

N.E.2d 502 (1956); and Wyoming, Michie’s Stats. Annot., 1957, Sec. 6-226

applying Indiana cases, see Myers v. State, supra, sinee derived from Indiana

statute.

Cf. Alabama, Code, 1940, Title 14, Sec. 426 and “legal eause or good excuse”

and Illinois Rev. Stats., 1959, Tit. 38, Sec. 565 as interpreted in People v.

Miller, 344 111. App. 574, 101 N.E.2d 874 (1951). In several states the prob

lem of the defense of claim of right has not received judicial consideration; as

to these states it may be argued that the common law defense of bona fide,

reasonable claim of right would be upheld if asserted. See Alaska, Laws

Annot., 1958, Sec. 65-5-112; Connecticut, Gen. Stats. Rev., 1958, See. 53-103;

District of Columbia, Code Annot., 1956, Sec. 22-3102; Hawaii, Rev. Laws,

1955, See. 312-1; Michigan, Stats. Annot., 1954, See. 28.820(1); Minnesota,

Stats. Annot., 1947, See. 621.57; Nevada, Rev. Stats., 1957, Sec. 207.200;

New Hampshire, Rev. Stats. Annot., 1955, Sec. 572:50; Oregon, Rev. Stats.,

Sec. 164.460; and Washington, Rev. Code, 1957, Sec. 9.83.060.

In the following states Boynton would probably have been found guilty:

Arkansas, Rev. Stats., 1959, Secs. 71-1801, 1802, 1803 (emergency acts designed

specifically to counteract sit-in situations) ; Delaware, Code Annot., 1953, Tit.

11, Sec. 871 (elaim of ownership only defense) ; North Carolina, Gen. Stats.,

Tit. 14, Sec. 134 as interpreted in State v. Clyburn, 247 N.C. 455, 101 S.E.2d

295 (1958); and South Carolina, Code of Laws, 1959, Sec. 16-386 (originally

directed at Negroes after Civil War, see State v. Cochfield, 15 Rich. (49

S.C.L.) 53 (1867)).

In England and the Common-wealth countries, Boynton’s deed would not

have been a crime; see cases requiring breach of peace or use of actual force

to make trespass indictable, B. v. Storr, 3 Burr. 1698, 97 E.R. 1053 (1765);

B. v. Blake et al., 3 Burr. 1731, 47 E.R. 1070 (1765) ; and B. v. Wilson, 8

Term Rep. 357, 101 E.R. 1432 (Kingston Assizes, 1799); except in South

Africa where the relevant statute specifically is directed at the Natives. See

Natives (Urban Areas) Consolidation Act of 1945, See. 9, para. 9, as pro

vided by Sec. 29, para, e of Native Laws Amendment Act, No. 36 of 1957.

Cf. also Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act, No. 52 of 1951, Sec. 1 with

interpretation thereof in B. v. Phiri (4) S.A. 708 (T) (1954) and commentary

thereon in 72 South Af. L.J. 125 (1955). The only other Commonwealth

countries in which Boynton might have been tried probably would have

acquitted him on the basis of his defense of entry under a bona fide claim

of right. See New Zealand, Police Offences Amendment Act (No. 2) No. 43

of 1952, Sec. 3 as interpreted in By an v. Stanford, 15 N.Z.L.R.C.A. 390 (1897),

James v. Butler, 25 N.Z.L.R.C.A. 653 (1906) and Greenaway v. Hunt and

Weggery [1922] N.Z.L.R. 53 [1921], G.L.R. 673; Victoria, Australia, Police

Offences Act, No. 6337 of 1958, Sec. 20 as interpreted in Falkingham v.

Fregon, 25 V.L.R. 211, 21 A.L.T. 123 (1899) ; and Tasmania, Trespass to

Lands Act, 1862, as interpreted in Gripps v. Gripps, 20 Tas. L.R. 47 (1924).

10

foreement of alleged private property right, by criminal

law or otherwise. Or, to rephrase the matter, the problem

is one of how far certain claimed private property rights

extend. Such controversy, in recent years, has arisen in

various forms.

Where Jehovah’s Witnesses were convicted of trespass

for having distributed literature on the premises of a

company-owned town contrary to the wishes of the town’s

management, Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, Mr. Justice

Black, for the Court, wrote that “ [t]he more an owner, for

his advantage, opens up his property for use by the public

in general, the more do his rights become circumscribed

by the statutory and constitutional right of those who use it.

. . . ” at p. 506 and “ [wjhen we balance the Constitutional

rights of owners of property against those of the people

to enjoy freedom of press and religion, as we must here, we

remain mindful of the fact that the latter occupy a pre

ferred position,” at p. 509. Conviction was reversed. In

Martin v. Struthers, 319 U.S. 141, this Court held uncon

stitutional an ordinance which made unlawful ringing

doorbells of residences for the purpose of distributing hand

bills, upon considering the free speech values involved—-

“ [d]oor to door distribution of circulars is essential to the

poorly financed causes of little people,” at p. 146—and that

the ordinance precluded individual private householders

from deciding whether they desired to receive the message.

But in effecting “an adjustment of constitutional rights in

the light of the particular living conditions of the time and

place”, Breard v. Alexandria, 341 U.S. 622, 626, the Court,

assessing a conviction for door-to-door commercial solicita

tion involving various popular magazines, contrary to a

“Green Biver” ordinance, concluded that the community

“speak[ing] for the citizens,” 341 U.S. 644, might convict

for crime in the nature of trespass. The decision turned

11

upon balance of the “conveniences between some house

holders’ desire for privacy and the publisher’s right to dis

tribute publications in the precise way that those soliciting

for him think brings the best results.” 341 U.S. at 644. Be

cause, among other things, “ [subscription may be made by

anyone interested in receiving the magazines without the

annoyances of house to house canvassing,” ibid., the judg

ment was affirmed.

The ordinarily unchallenged right of real property

owners to fasten covenants on their land has been circum

scribed to the extent that the Fourteenth Amendment pro

hibits enforcing of racial restrictive covenants by injunc

tion, Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, or damages, Barroivs

v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249.

A like collision between federal rights, this time conferred

by the National Labor Relations Act, and rights in real

property defined by state law, also has called for reconcilia

tion in this Court. Republic Aviation, Inc. v. N. L. R. R.,

324 U.S. 793, upheld the validity of National Labor Re

lations Board rulings that, lacking special circumstances

that might make such rules necessary, employer regulations

forbidding all union solicitation on company property re

gardless of whether the workers were on their own or com

pany time, constituted unfair labor practices. In assessing

the regulations, Justice Reed balanced the employer’s right

to maintain discipline wTith the employees’ right to organize;

no weight was given to the employer’s property right, men

tioned solely at 324 U.S. 802, note 8.4 Similarly a Baltimore

City Court, State of Maryland v. Williams, 44 Lab. Rel. Ref.

4 See also N.L.B.B. v. American Pearl Button Co., 149 F.2d 258 (8th

Cir., 1945) ; United Steelworkers v. N.L.B.B., 243 F.2d 593, 598 (D.C. Cir.,

1956) (reversed on other grounds) 357 U.S. 357. (“Our attention has not

been called to any case under the Wagner Act or its successor in which it

has been held that an employer can prohibit either solicitation or distribution

of literature by employees simply because the premises are company property.

12

Man. 2357, 2361 (1959) has on Fourteenth Amendment and

Labor Management Relations Act grounds, decided that

pickets may patrol property within a privately owned shop

ping center.5

The Commerce Clause too has been interposed by the

courts between private proprietors of interstate carriers

and passengers who resisted racial segregation on those

carriers by rule of the management. Whiteside v. Southern

Bus Lines, 177 F.2d 949 (6th Cir., 1949); Chance v. Lam

beth, 186 F.2d 879 (4th Cir., 1951), cert, den., 341 U.S.

941. And the Fourteenth Amendment forbids police to ar

rest those who violate an intrastate carrier’s private racial

seating regulation, where to violate management’s seating

rule is a crime. The statute did not mention race. Boman

v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. 18187, July 12, 1960, Fifth

Circuit.

In such eases the approach of the courts has been infused

with an awareness, as Mr. Justice Frankfurter wrote, con

curring in Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 510, that “when

decisions by State courts involving local matters are so

interwoven with the decision of the question of Constitu

tional rights that the one necessarily involves the other,

Employees are lawfully within the plant, and nonworking time is their own

time. I f Section 7 activities are to be prohibited, something more than mere

ownership and control must be shown.”)

Compare N.L.B.B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U.S. 240, 252 (employees

seized plant; discharge held valid: “high-handed proceeding without shadow

of legal right”) .

5 See also People v. Barisi, 193 Misc. 934, 86 N.Y.S.2d 277, 279 (1948)

(picketing within Pennsylvania Station not trespass; owners have opened it

to public and their property rights are 'circumscribed, by the constitutional

rights of those who use it.’ ”) ; Freeman v. Retail Clerics Union, Washington

Superior Court, 45 Lab. Eel. Eef. Man. 2334 (1959) (shopping center owner

denied relief against picketers on his property; relying on Fourteenth Amend

ment).

13

State determination of local questions cannot control the

Federal Constitutional right.” 6

Therefore, here, the essential right of the management of

the Trailways Terminal restaurant to enforce segregation

of interstate passengers by means of the full force of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, asserted through its police and

courts, must be weighed against the claim of petitioner, an

interstate traveler, to freedom of movement without being

hobbled by racial distinction in the course of an interstate

journey (Article 1, §8), and his further claim to be free of

arrest and conviction in the Virginia courts in the enforce

ment of such racial rules (Fourteenth Amendment). Peti

tioner submits that under our Constitution this conflict can

be resolved only in the interest of freedom of movement

among the states and freedom from criminal conviction

in the state courts to enforce racial discrimination.

6 For a related conclusion in a different constitutional context see, Jones

v. United States, U.S. ------, ------ (1960) (“ . . . it is unnecessary and

ill-advised to impart into the law surrounding the constitutional right to be

free from unreasonable searches and seizures subtle distinctions, developed

and refined by the common law in evolving the body of private property law

which, more than almost any other branch of law, has been shaped by dis

tinctions whose validity is largely historical. . . . Distinctions such as those

between ‘lessee,’ ‘licensee,’ ‘invitee’ and ‘guest,’ often only of gossamer strength,

ought not to be determinative in fashioning procedures ultimately referable

to constitutional safeguards.” 4 D.ed.2d 697 at 705.

14

I.

The decisions below conflict with principles estab

lished by decisions of this Court by denying petitioner,

a Negro, a meal in the course of a regularly scheduled

stop at the restaurant terminal of an interstate motor

carrier and by convicting him of trespass for seeking

nonsegregated dining facilities within the terminal.

In this context we approach petitioner’s first contention

that his arrest and conviction disrupted his interstate jour

ney in a manner violative of Article I, §8, cl. 3:

[“E]ver since Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. (US) 1, 6

L.ed. 23, the states have not been deemed to have au

thority to impede substantially the free flow of com

merce from state to state, or to regulate those phases

of the national commerce which, because of the need

of national uniformity, demand that their regulation,

if any, be prescribed by a single authority . . . ”

wrote Chief Justice Stone in Southern Pacific Co. v.

Arizona, 325 U.S. 761, 767.

In that case the Arizona Train Limit Law, which limited

the size of trains to fourteen passenger or seventy freight

ears was held violative of the Commerce Clause. The law

required that interstate rail transport be disrupted in

Arizona to adjust the length of trains to that state’s de

mand. The “state interest [was] outweighed by the in

terest of the nation in an adequate economical and efficient

railway transportation service, which must prevail.” 325

U.S. at 783-84. Of a piece with the Southern Pacific de

cision, and more intimately related to the suit at bar, was

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U.S. 373, which held unconstitu

tional, under the Commerce Clause, Virginia’s segregated

seating statute as applied to an interstate bus passenger.

15

“On such interstate journeys, the enforcement of the re

quirements for reseating would be disturbing.” 328 U.S.

at 381. “ . . . [S]eating arrangements for the different

races in interstate motor travel require a single, uniform

rule to promote and protect national travel.” Id. at 386.

And the disturbing effect of segregated seating in dining

service was recognized by this Court in Henderson v. United

States, 339 U.S. 816, 825, which, while dealing with the

Interstate Commerce Act, condemned racial segregation in

railroad dining cars as “emphasiz[ing] the artificiality of

the difference in treatment which serves only to call at

tention to a racial classification of passengers holding

identical tickets and using the same public dining facility.”

Only last year, the vigor of the Morgan and Southern

Pacific cases was reaffirmed in Bibb v. Navajo Freight

Lines, 359 U.S. 520, which cited both with approval at pp.

526 and 528, and concluded that Illinois’s mud-flap regula

tion was a burden on interstate commerce: “state regula

tions that run afoul of the policy of free trade reflected in

the Commerce Clause must . . . bow.” 359 U.S. at 529.

The Richmond Trailways Terminal is, of course, itself,

a stationary accommodation. But clearly it is now settled

that a facility need not be in motion to come under the

Commerce Clause. An interstate bus terminal restaurant,

built as an integral part of the terminal structure, is as

much a part of interstate commerce, as, for example, a stock-

yard for the care and feeding of cattle during a pause in

their interstate movement. See Stafford v. Wallace, 258

U.S. 495, 519, in which Chief Justice Taft wrote that

“this court declined to defeat this purpose [of the Com

merce Clause] in respect of such a stream, and take it

out of complete national regulation by a nice and

technical inquiry into the non-interstate character of

some of its necessary incidents and facilities when

16

considered alone and without reference to their associa

tion with the movement of which they were an essen

tial but subordinate part.”

Indeed, Hall v. DeCuir, 95 U.S. 485, struck down a stat

ute forbidding racial distinctions on a steamboat even

though the situation at bar involved an intrastate trip.

The law, it was held, interfered with interstate voyages.

Pursuant to this view the Court has held that “ . . .

warehouses engaged in the storage of grain for interstate

or foreign commerce are in the federal domain . . . ,”

Rice v. Santa Fe Elevator Corp., 331 U.S. 218, 229; and

that a transaction with a redcap during a stop at a railroad

station is within the same jurisdiction, N.Y. N.H. & H. R.

Co. v. Nothnagle, 346 U.S. 128, 130.7 Petitioner submits,

therefore, that in determining the standards which the ter

minal and the restaurant, which was an integral part of it,

must meet under the Commerce Clause, the same rules must

apply, for purposes of this case, as would be applied to a

moving bus.

It has been argued that the Commerce Clause does not

reach rules of carriers which have no origin in state law.

A like argument was made in Re Debs, 158 U.S. 564, 581.

To this, the opinion of the Court replied:

“It is curious to note the fact that in a large propor

tion of the cases in respect to interstate commerce

brought to this court the question presented was of

the validity of state legislation in its bearings upon

interstate commerce, and the uniform course of decision

7 See also United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U.S. 218, 228. Sprout v.

South Bend, 277 U.S. 163, 168. And see also Kirschenbaum v. Walling, 316

U.S. 517 (commerce power, expressed in the Fair Labor Standards Act, as

interpreted in that case, reached employees of a loft building whose tenants

were principally engaged in interstate commerce). All of these are oases

which hold that the commerce power extends sufficiently far to uphold federal

regulation of activities, which themselves, actually do not move among the

States.

17

has been to declare that it is not within the competency

of a state to legislate in such a manner as to obstruct

interstate commerce. If a state with its recognized

powers of sovereignty is impotent to obstruct inter

state commerce, can it be that any mere voluntary as

sociation of individuals within the limits of that state

has a power which the state itself does not possess!”

Here, however, we have, in addition, police arrest and

•court conviction. Concerning such circumstances, in a

background of racial discrimination in interstate travel,

two Courts of Appeals have held the racial restriction un

constitutional. The Fourth Circuit has written:

“Under the company’s regulations, the three coaches first

in line were designed for Negro passengers and the

next two for white passengers . . . ” (Emphasis sup

plied. )

“At Richmond, the trainmen segregated the passengers

. . . The regulations of the company upon which the

decision of the case turns were issued to the train

men . . . ” (Emphasis supplied.)

“It is true that the regulation of the carrier was not

enacted by state authority, although the power of the

state is customarily involved to enforce it, but we

know of no principle of law which requires the courts

to strike down a state statute which interferes with in

terstate commerce but to uphold a railroad regulation

which is infected with the same vice.”

Chance v. Lambeth, 186 F.2d 879, 880, 883 (4th Cir., 1951),

cert, denied 341 U.S. 941, Parker, Soper, Dobie, JJ.

And, in Whiteside v. Southern Bus Lines, 177 F.2d 949,

953 (6th Cir., 1949), the Sixth Circuit held, per Hicks,

Simons and McAllister, JJ., that

18

“appellant here boarded an interstate conveyance in Il

linois which has neither statute, decision or custom

sanctioning or requiring segregation based upon race

or color. The requirement [of the carrier] that she

change her seat with all her accompanying impedi

menta the moment she crossed the Kentucky line, was

a breach of the uniformity which under the Morgan

case, is a test of the burden placed upon interstate

commerce.

“It must also be observed that acts burdening inter

state commerce are not, like those inhibited in the

Fourteenth Amendment, limited to state action. Bur

dens may result from the activities of private persons

as the great mass of federal criminal legislation vali

dated under the authority of the Commerce Clause,

discloses. But, if state action is a prerequisite to

the invalidity of the regulation here considered as it

was applied to the appellant, state action is clearly

to be perceived in the ejection of the appellant by a

state police officer.” 8

Here we have similar elements which compel a con

clusion that halting Boynton’s journey violated the Com

merce Clause: A racial impediment to reasonably secur-

8 To the extent that requisite state involvement is supplied by police

enforcement of an intrastate carrier segregation regulation, the F ifth Circuit,

in passing on a Fourteenth Amendment contention recently has arrived at a

similar result. Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., No. 18187, July 12, 1960,

F ifth Circuit, Tuttle and Wisdom, JJ. (Cameron, J., dissenting), held that “so

long as such an ordinance [committing seating arrangements to the driver]

was in force, the acts of the Bus Company in requiring racially segregated

seating were state acts and were thus violative of the appellant’s constitutional

rights. . . . ” (Emphasis supplied.)

“Of course, the simple company rule that Negro passengers must sit in back

and white passengers must sit in front, while an unnecessary affront to a large

group of its patrons would not effect a denial of [Fourteenth Amendment]

constitutional rights if not enforced by force or by threat of arrest and

criminal action.”

19

ing meal service in the manner of white passengers in the

course of an interstate journey, in an interstate terminal

restaurant constructed and maintained for the purpose

of facilitating interstate commerce; an interruption of the

interstate journey, complete and decisive; and, should state

involvement be required for application of the Commerce

Clause, invocation of state statute to enforce the racial

rule and the full intervention of Virginia police and courts

to uphold it.

In Southern Pacific v. Arizona, 325 U.S. 761, 768, Chief

Justice Stone, writing of the limitations which the Com

merce Clause places upon activities which burden inter

state commerce, stated—“fwjhether or not this long recog

nized distribution of powers between the national and the

state governments is predicated upon the implication of

the commerce clause itself [citations omitted]; or upon the

presumed intention of Congress, where Congress has not

spoken [citations omitted], the result is the same.”

Congress certainly has not spoken explicitly on the ques

tion of whether racial segregation in an interstate bus ter

minal, enforced by state arrest and conviction in the courts,

burdens interstate commerce. Morgan v. Virginia, supra,

has held that Congress has not spoken on the closely re

lated issue of racial segregation on interstate buses, 328

U.S. 373, at p. 386 (“ . . . there is no federal act dealing

with the separation of races in interstate transportation.

. . .). While certain provisions of the Motor Carriers Act

(49 U.S.C. §316(d)) are analogous to the Interstate Com

merce Act provision (49 U.S.C. §3(1)) by which this Court

struck down dining car, Henderson v. United States, 339

U.S. 816 and Pullman car segregation, Mitchell v. United

States, 313 U.S. 80, Morgan may be taken as a determina

tion that congressional intent on the precise question of

race discrimination in interstate bus travel is at least not

20

sufficiently express to conclude this case by itself. As in

Morgan, this Court here, petitioner submits, should strike

down the burden on commerce in the absence of contrary

indications of intent from Congress.

The Court, however, by letter to counsel for Respondent

has inquired concerning “the intercorporate relationship

between the Trailways Bus Company and the Trailways

Bus Terminal, Inc., set forth in any documents of which

the Virginia courts can take judicial notice.” Appendix

A to Respondents’ Brief in Opposition, p. 12. To Peti

tioner, this perhaps indicates interest by the Court in the

question of congressional intention as it may have been

expressed in the Motor Carriers Act. Title 49, §303(19) of

that Act provides that its terms apply to services and trans

portation, which includes “facilities and property operated

or controlled by any such carrier,” and §316 (d) of the Act

contains an “undue preferences” and “prejudices” provi

sion like that which this Court treated in Henderson, supra,

when dealing with rail travel. These Motor Carriers Act

provisions have been construed in Keys v. Carolina Coach

Co., 64 M.C.C. 769 (1955), as imposing upon bus carriers

requirements concerning race like those the Interstate Com

merce Act places on railroads. Under these circumstances

it might be argued that the Motor Carriers Act expresses

congressional intention concerning the discrimination in

volved in this case. That Act, so interpreted, might apply

here, specifically, if the Richmond Trailways Terminal

were “operated” or “controlled” by a carrier.

Petitioner submits that, if Morgan does not conclude the

issue, whether the Trailways Bus Company and the Trail-

ways Bus Terminal are sufficiently related to place the

Terminal explicitly under the Motor Carriers Act, or not,

the result is the same, for the intention of Congress, as it

21

treats the problem of this ease, mast be regarded as the

same for either situation.

Should the first condition obtain (he., the Terminal is

“operated or controlled” by a carrier), obviously the ex

pressed intention of Congress is that such racial impedi

ment is impermissible if there is to be an unburdened flow

of commerce among the states. Should the second condition

obtain (he., the terminal is not operated or controlled by

a carrier), it cannot be assumed that Congress meant to

remit all of the interstate terminal’s multifarious acts, as

regulated by the myriad provisions of the Motor Carriers

Act, no matter how burdensome to interstate commerce,

to the unfettered discretion of the terminal management

or state law enforcing that discretion. Bob-Lo Excursion

Co. v. Michigan, 333 U.S. 28, which sustained a state anti-

discrimination law as applied to foreign commerce, when

contrasted to Morgan, supra, demonstrates the importance

attached to keeping the channels of movement among the

states free from racial impediments. Therefore, validation

of segregation in these channels is not merely to be as

sumed. Surely, if Congress intended to commit to state

law the matter of racial segregation, enforced by state laws

in the midst of an interstate bus journey, this intention

would have been pronounced quite explicitly. But such a

pronouncement would raise serious Fifth Amendment ques

tions (see Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IT.S. 373, 380—“Con

gress, within the limits of the Fifth Amendment has au

thority to burden commerce” ; Secretary of Agriculture v.

Central Roig Refining Company, 338 U.S. 604, 616—“not

even resort to the Commerce Clause can defy the standards

of due process” ; and see Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497).

However, there is no evidence of such intention and none

should be imputed to Congress, especially in the light of

the constitutional questions this would raise. Therefore,

even in the case of an interstate terminal not “operated

22

or controlled” by a carrier, a racial burden like that in

flicted on Boynton by the Commonwealth of Virginia, un

constitutionally burdens commerce.

In any event, the terminal in question is owned by Trail-

ways Bus Terminal, Inc., whose officers and directors, in

1959, with one exception, were all also officers or directors

of either Carolina Coach Company or Virginia Stage Lines,

both interstate carriers.9 Petitioner is depositing certified

copies of the relevant corporate charters and annual reports

with this Court.

While the Virginia Attorney General has concluded that

the Virginia courts would not take judicial notice of these

charters (Brief in Opposition, p. 4), petitioner assumes

that the Attorney General would not deny the validity of

these documents. In either event, the result, petitioner

submits, is the same.

II.

Petitioner’s criminal conviction which served only to

enforce the racial regulation of the bus terminal restau

rant conflicts with principles established by decisions

of this Court, and thereby violates the Fourteenth

Amendment.

Beyond question, petitioner was arrested by the police

and convicted by the courts, pursuant to state statute, to

enforce the racial segregation demanded by the Trailways

Terminal restaurant. Petitioner contends that this pun

ishment violates Fourteenth Amendment rights in that

it amounts to governmental enforcement of racial segrega

tion. See, e.g., Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, 18, in which

the issue was whether judicial enforcement of privately

9 Hitchcock's Mass Transportation Directory (1959-60 ed.), 205 (Carolina

Coach Co.) ; 242 (Virginia Stage Lines) indicates clearly the interstate

character of these carriers.

23

arrived at racial restrictive covenants violated the Four

teenth Amendment. There the Court held that judicial

enforcement of racial discrimination violates the Four

teenth Amendment:

The short of the matter is that from the time of

the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment until the

present, it has been the consistent ruling of this Court

that the action of the States to which the Amendment

has reference, includes action of state courts and

state judicial officials. Although, in construing the

terms of the Fourteenth Amendment, differences have

from time to time been expressed as to whether par

ticular types of state action may be said to offend the

Amendment’s prohibitory provisions, it has never been

suggested that state court action is immunized from

the operation of those provisions simply because the

act is that of the judicial branch of the state govern

ment.

The only contention advanced by respondents in response

to this aspect of the petition for writ of certiorari seems to

argue that because the discrimination originated in a

“private” directive, i.e., that of the restaurant management,

Bruce Boynton’s criminal conviction is not that sort of

state action which the Fourteenth Amendment interdicts.

Respondent relies on the theory expressed in Williams v.

Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F.2d 845 (4th Cir.,

1959). Apart from the fact that that restaurant was hardly

so integral a part of commerce as the one involved in this

case, and that petitioner here had no reasonable alternative,

but had to finish a meal quickly in the terminal and resume

his bus trip, petitioner, here, seeks not relief against the

restaurant, but immunity from conviction by the State and

its attendant consequences, especially for one who is a

law student.

24

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 TJ.S. 501, 505-06, stated a funda

mental rule that:

. . . the corporation’s property interests [do not]

settle the question. The State urges in effect that

the corporation’s right to control the inhabitants of

Chickasaw is coextensive with the right of a home-

owner to regulate the conduct of his guests. We can

not accept that contention. Ownership does not always

mean absolute dominion. The more an owner, for

his advantage, opens up his property for use by the

public in general, the more do his rights become cir

cumscribed by the statutory and constitutional rights

of those who use it.

The terminal restaurant was open to that portion of

the interstate traveling public of which petitioner was a

part. Indeed, it exists principally, and was built into the

terminal, to serve bus riders who travel on interstate buses

that make stops in Richmond. It fairly may be stated that

petitioner and other travelers did not seek out the terminal;

rather, they were carried into it by interstate buses for re

freshment without which interstate bus travel would be

impossible or highly inconvenient. Reasoning like that

employed in Marsh has struck down trespass prosecutions

for picketing in Pennsylvania Station, New York; for

picketing in a Maryland shopping center, and for similar

conduct in a Washington State shopping center.10 These

decisions, for similar reasons, should apply here.

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., supra, p. 12, also

interdicts, under the Fourteenth Amendment, state criminal

prosecution in support of privately declared racial regula

tion on local buses, even though the statute in question it-

10 See n. 5, supra.

25

self made no mention of race. While some reliance there is

placed on the fact that the buses were franchised, it is not

so much the documents of franchise but the exclusivity

which they evidenced that controls, petitioner submits. Un

der the circumstances of this case we have similar exclu

sivity.

Any weighing of reasonable alternative action that might

have been taken by petitioner, cf. Breard v. Alexandria, 341

U.S. 622, 644 (magazines may sell subscriptions without

door-to-door solicitation); Republic Aviation v. N.L.R.B.,

324 U.S. 793, 801, note 6 (employees denied full freedom of

association in “the very time and place uniquely appropri

ate”), shows that his only choice was to remain hungry or

submit to racial segregation, inconvenience, and humilia

tion.

The inquiry in a case such as this, therefore, does not

begin and end with a determination of where the legal title

or possessory interest lies. As in the National Labor Rela

tions Act cases, discussed supra, pp. 10-11, the question is

one involving other factors as well. Here, as in United

Steelworkers v. N.L.R.B., 243 F.2d 593, 598, petitioner was

“lawfully within” the terminal. He behaved himself well.

There was no disorder, nor was there any breach of the

peace. He believed, with reason, that he had a right to the

service he sought. There was no reasonable alternative

action for him to take.

It cannot be argued seriously that to uphold petitioner’s

conviction is necessary and reasonable for the maintenance

of law and order, and that, therefore, the statute in question,

as applied to petitioner in these circumstances, does not

violate the Constitution.11 The common law never pro-

11 Compare N.L.B.B. v. Fansteel Metal Corp., 306 U.S. at 253. (“To jus

tify such conduct because of the existence of a labor dispute or of an unfair

labor practice would be to put a premium on resort to force instead of legal

remedies and to subvert the principles of law and order which lie at the

foundations of society.”)

26

scribed as trespass conduct such as petitioner’s—i.e., con

duct which did not cause breach of the peace and which was

taken under a claim of right. Most other states, as footnote

3, indicates, would not have punished petitioner’s conduct,

either because those states have no statute covering “tres

pass” after refusal to depart from premises such as the

terminal, or because they recognize “claim of right” as a

defense, or because, in view of common law and general in

terpretations of this type of statute, it reasonably may be

assumed that they would recognize a peacefully asserted

bona fide claim of right. Neither does England or the

Commonwealth countries punish conduct such as Boynton’s,

except, instructively, South Africa, where a statute, directed

against Natives makes criminal deeds like petitioner’s.

This Court, petitioner submits, should not uphold as a

crime, petitioner’s peacefully asserted, reasonable claim to

equality in the course of a journey in interstate commerce.

Virginia’s action has no foundation in reason, other than

to uphold race discrimination. The judgment below denies

equal protection of the laws.

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, the judgment

below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Martin A. Martin

Clarence W. Newsome

T httrgood Marshall

J ack Greenberg

Attorneys for Petitioner

Louis H. P ollak

Constance Baker Motley

Of Counsel