Letter from Chachkin to Supreme Court

Public Court Documents

September 20, 1972

1 page

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Letter from Chachkin to Supreme Court, 1972. 8186b693-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/22265738-5b09-4ad5-b923-49b6c9b2a48f/letter-from-chachkin-to-supreme-court. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

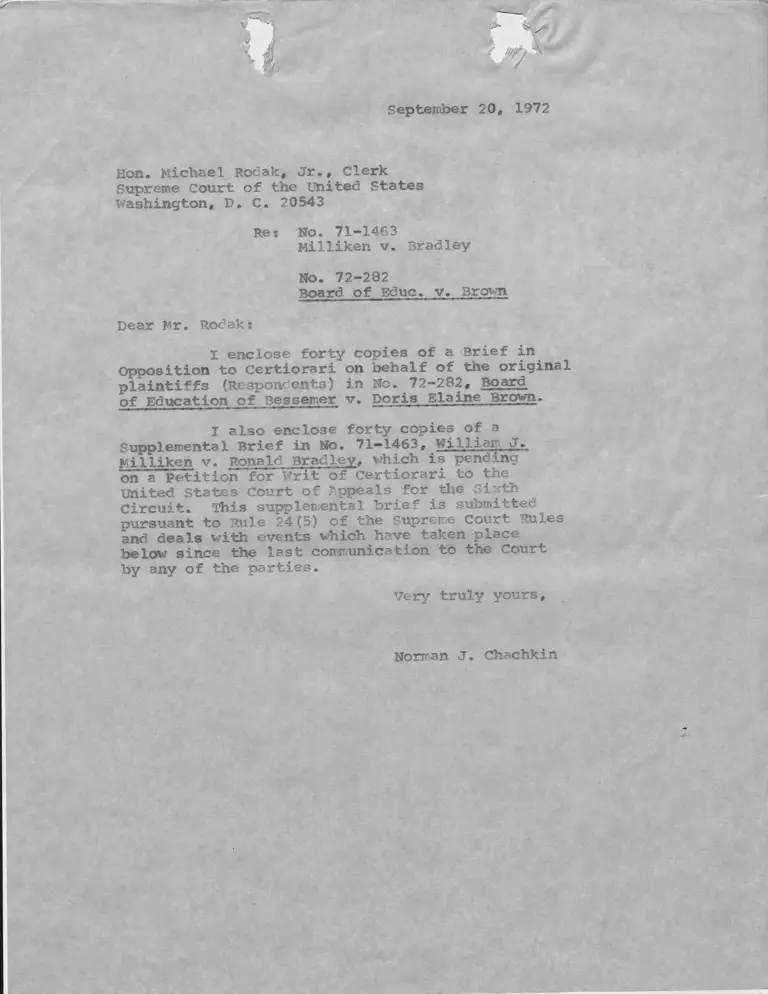

September 20P 1972

Kon. Michael Rocak, Jr., Clerk

Supreme Court of the United States

Washington* D. C» 20543

Re: No. 71-1463

Milliken v. Bradley

No. 72-282

Board of Educ. v. Brown

Dear Mr. Rodak:

I enclose forty copies of a Brief in

Opposition to certiorari on behalf of the original

plaintiffs (Respondents) in No. 72-282, Board

of Education of Bessemer v. Doris Blaine Brown.

I also enclose forty copies of a

Supplemental Brief in No. 71-1463, Williajr__iU.

Milliken v. Ronald Bradley, which is pending

on a Petition for Frit of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeal# for the Sixth

Circuit. This supplemental brief is submitted

pursuant to Rule 24(5) of the Supreme Court Rules

and deals with events which have taken place

below since the last communication to the Court

by any of the parties.

Very truly yours*

Norman J. Chachkin