Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 10, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Firefighters Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief Amicus Curiae, 1986. bdd141ba-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/222f2ca9-bcb3-4639-81c6-71596062debd/firefighters-local-union-no-1784-v-stotts-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

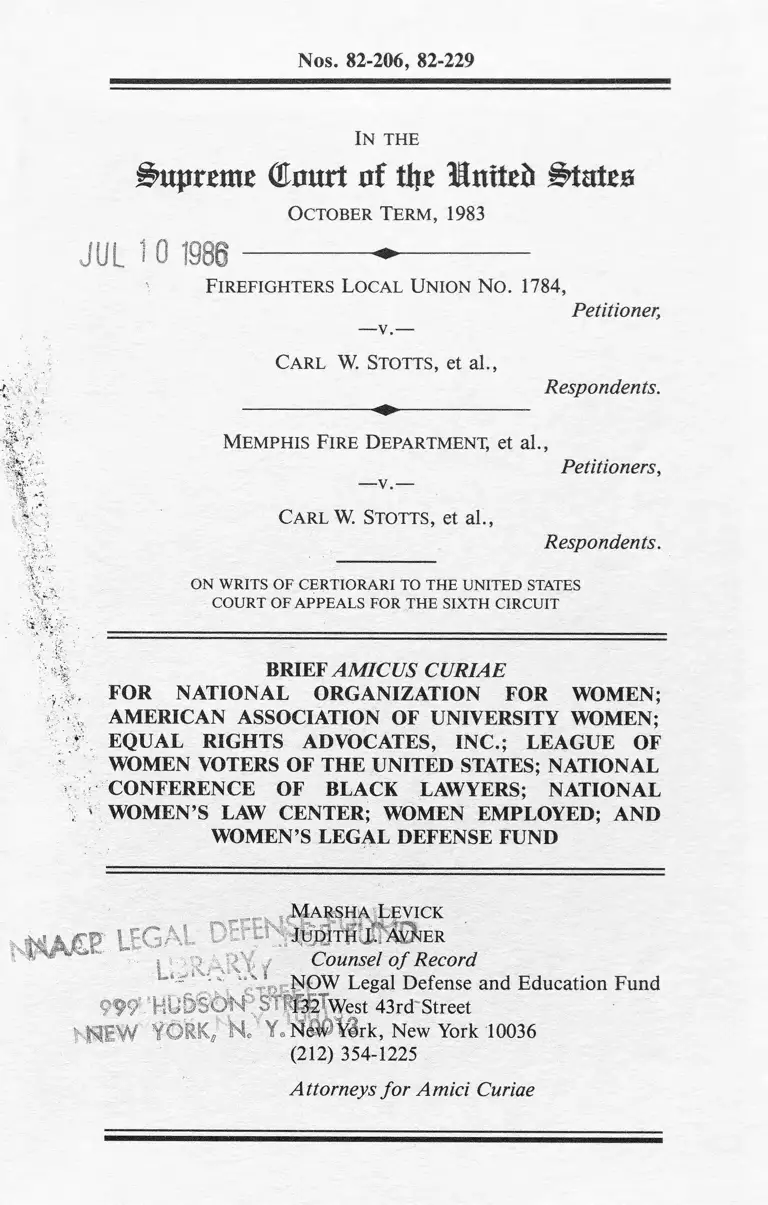

Nos. 82-206, 82-229

In the

Supreme (tart nf tl?e Mnitrti States

October Term , 1983

JU L ! 0 1988

Firefighters Local Union No . 1784,

Petitioner,

■r,-A

I

Carl W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents.

Memphis Fire Department, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

Carl W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

FOR NATIONAL ORGANIZATION FOR WOMEN;

AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF UNIVERSITY WOMEN;

EQUAL RIGHTS ADVOCATES, INC.; LEAGUE OF

WOMEN VOTERS OF THE UNITED STATES; NATIONAL

CONFERENCE OF BLACK LAWYERS; NATIONAL

WOMEN’S LAW CENTER; WOMEN EMPLOYED; AND

WOMEN’S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

Marsha Levick

legal DFrtH' JUPlTiJjl'ABlER

Counsel o f Record

~ N O W Legal Defense and Education Fund

9' l.u":ON S 132 West 43rd Street

HEW YORK, K Y.NM0Wrk, New York 10036

(212) 354-1225

Attorneys fo r Amici Curiae

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.... ....... i

INTEREST AND DESCRIPTION OF

AMICI CURIAE....... 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.......... 7

ARGUMENT..... ................... 10

I. THIS CASE RAISES ISSUES

HAVING A SIGNIFICANT

IMPACT ON WOMEN'S OPPOR

TUNITIES TO BECOME ECO

NOMICALLY SELF-

SUFFICIENT.............. 10

II. FEDERAL ANTI-DISCRIMINA

TION POLICY REQUIRES

EFFECTIVE REMEDIES FOR

EMPLOYMENT DISCRIMINA

TION BY GOVERNMENT

EMPLOYERS..... . 25

A. The 1972 Amendments

to Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of

1964 Were Enacted to

Redress Widespread

Employment Discrim

ination In State and

Local Government

Employment....... . . 25

B. Government Employment

Practices, Such As

Seniority-Based Lay-

Off Plans, Cannot Be

Allowed To Frustrate

Efforts To Remedy

Discrimination..... 29

1. The use of the

"last hired-first

fired" principle

to reduce employ

ment in times of

economic recession

has a dispropor

tionate impact on

minorities and

women.......... 29

2. Courts must be free

to impose affirmative

color-conscious or

gender-conscious rem

edies if they are to

fully effectuate the

broad public policy

against employment

discrimination.... 36

III. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER

WAS NOT AN ABUSE OF DIS

CRETION AND SHOULD BE

UPHELD.......... . 43

A. Equitable Relief Will

Be Disturbed Only If

It Constitutes An

Abuse Of Discretion

By The Lower Court.. 43

B. The District Court's

Order Was Grounded

Upon Sufficient Evi

dence of Discrimina

tion And Therefore

Was Not An Abuse of

Discretion......... 46

c.

CONCLUSION.

The District Court,

Pursuant To Its Duty

To Enforce The Decree

And Its Authority To

Modify It In Light

Of Changed Circum

stances, Did Not

Abuse Its Broad

Equitable Powers.... 50

................. 57

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Rage:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

. S "405 "(19 75)T777777. . . . 25 , 43

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co. ,’ 413_U . 3 . 36.(1'974777.... 26

Bolden v. Pennsylvania State

Police, 73 F.R.D. 370

TETD. Pa. 1976), affd,

578 F .2d 912 (3d Cir. 1978)... 54

Bridgeport Guardians Inc, v.

Members of the Bridgeport"

C .S . Comm' n , 482 17 2 d 1533

T7d~Cir. 1973)................ 55

Brotherhood of Locomotive

Sng in e e rs ' v . Miss bur i-~~

Kansas-Texas R.R. Co.,

163 43

Browder v. Director, 111. Dept.

of Corrections, 434 UTS. 257

-(T977T7. . ....... 45

Brown v. Board of Ed., 349 U.S.

294 (1955). . 7777777. .......... 45

Brown v. Neeb, 644 F.2d 551

(6th Cir. 19 81)............... 53

Columbus Bd. of Ed. v. Penick,

443 U.S. 449 (1979).... ..7... 45

Detroit Police Officers Ass'n

Y; Young, 608 F .2d 671

T6th Cir. 1979), cert. denie_d,

452 U.S. 938 (198TT77........ 55

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Cases: Page:

Franks v. Bowman Transpor-

tation Co., 424 U.S. 747 36, 37.

T1976).... .................... 45, 56,

57

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S.

448 (19 80)777. . .'..'............ 41

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

"U.S. 424 (1971)...... ........ 26

Hecht Co. v. Bowles, 321 U.S,

J2T~TTW0T777777............. 44

International Salt Co. v.

United States, 332 U.S. 392

T O T 7 T ..... .T................. 44

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192

"(19 73)...... .7................ 43, 44,

54

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green ,~~4TT U.S. 792 (1973)___ 25

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S.

267 (1977)..... .............. 55

Perrotte v. Percy, 489 F.Supo.

212 (E.D. WTscT 1980)..../.... 53

Regents of the Univ. of Calif.

v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978). 41

Schaefer v. Tannian, 394 F.Supp. 12, 15,

1128 (E.D. MTcTT 1974) ........ 17, 54

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Depart-

ment, 679 F.2d 541 (6th Cir.

1982).......................... 47, 48,

50

li

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Cases: Rage:

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

■ ~ W r ^ F T d r r “?02~u7sT~T 43 , 44,

(1971)................ 45, 55

System Fed'n Ho. 91, Ky. Emp.

Dept. v. Wright) 364 U.S. 642

(1961)...... .77........... . 44, 53

Teamsters v. United States, 431

— U. S . 324 T T T n J ~ 777777. . . . . . 29,56

United Air Lines, Inc. v. Evans,

431 U.S'..553 (1977)........T7. 56

United States v. Armour Co.,

402 U.S. 673 (1981) 7.777..... 52

United States v. City of

Alexandria, 614 F.2d 1358

(5th Cir. 1980)........... 15, 17,

49

United States v. City of

Buffalo, 633 F.2d 643

(2d Cir. 1980).............. 17

United States v. City of

Chicago, 385 F.Supp. 543

IT. D 111. 1974)......... . 12, 16

United States v. City of Miami,

614 F .2d 1322 (5th Cir.

1980)......................... 49

United States v. City of

Philadelphia’ 499 F.Supp.

1196 (E.D. Pa. 1980)........... 17

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Cases: Page:

United States v. City of

Yonkers, 80 Civ. 7407

(S.D.N.Y. 1979)............... 16

United States v. Nassau County

Police Dept.8 No. 76 C 1869

(E . D .N . Y July 21, 1978)..... 16

United States v. United Shoe

~~CorpTT 391 U.S. J W J I 9 W ) --- 53

United Steelworkers of America

v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

TT979) . ....................... 25, 41

Codes Sc Statutes :

Exec. Order 11246, 30 Fed.

Reg. 12319 (1965) as amended

by Exec. Order 11375, 32

Fed. Reg. 14303 (1976)....-- 30

42 U.S.C.A. §1981 (West 1981)... 30

42 U.S.C.A. §1983 (West 1981)... 30

42 U.S.C.A. §2000d, Title VI,

§601 of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 (West 1981) . .......... 30

42 U.S.C.A. §2000e et seq.,

Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 as amended by the

Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972 (West 1981)...... passim

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Codes & Statutes: Page:

42 U.S.C.A. §6705 (f) (2) Public

Works Employment Act

(West 1983)...... . ........... 30

Studies, Pamphlets and

Periodicals•

Bureau of Labor Statistics,

U.S. Dept, of Labor, "Employ

ment and Earnings" (March

1982)........................

Bureau of Labor Statistics,

U.S. Dept, of Labor, "Employ

ment in Perspective: Working

Women" (ReDort No. 544,

1978) ..../...................

Bureau of Labor Statistics,

U.S. Dept, of Labor, "News:

Trends in Weekly and Hourly

Earnings for Major Labor

Force Groups,” (Nov. 2,

1977)........................

Bureau of Labor Statistics,

U.S. Dept, of Labor, "Per-

spectives on Working Women"

(1980) ............ ...........

Bureau of National Affairs,

"Layoffs, Rifs, and EEC in

the Public Sector: A BNA

Special Report" (Feb.

1982).... ....................

13, 14

21

22

22

13, 20

33, 34

35

v

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Studies, Pamphlets and

Periodicals: Page:

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce,

"Characteristics of Households

and Persons Receiving Selected

Non-Cash Benefits: 1980”

(1982)........................ 19

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce,

"Classified Index of

Industries and Occunations"

(Nov. 1982)....... ‘. . . ....... 13

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce,

"Families Maintained by

Female Householders 1970-79"

(1980)........................ 20

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, "Money

Income of Households, Families,

and Persons in the United

States: 1980" (July, 1982)... 23

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, "Money

Income and Poverty Status of

Families and Persons in the

United States: 1981" (Advance

Data from the March, 1982

Current Population Survey)

(1982)___..................... 19

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Studies, Pamphlets and

Periodicals: Page :

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce,

"Statistical Abstracts of

the United States: 1981"

(1981)........................ 14, 15

Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, "Wage

and Salary Data from the

Income Survey Development

Program: 1979" (1982)...... . 21, 23

Equal Employment Opportunities

Enforcement Act of 1971,

Hearings on S.2515, 2619,

H.R. 1746 Before the Subcomm.

on Labor of Senate Comm, on

Labor & Public Welfare,

92d Cong. (1971).............. 28

Federal Government Task Force,

"Reduction In Force Survey

Third Quarter Fiscal Year

1982"...... ................... 34

Federal Government Service Task

Force, "Summary of Task Force

RIF Survey, Quarter 1 and

Quarter 2 Fiscal Year 1982"... 34

H.R. No. 238, 92d Cong.,

1st Sess. (1971), reprinted

in 1972 U.S. Code Cong.

B~Ad. News 2137............... 27

Nat'1 Advisory Council on

Economic Opportunity,

"Critical Choices for the 80's"

(1980)........................ 18, 19

20

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES--Continued

Studies, Pamphlets and

Periodicals: Page:

N.Y. Times, Nov. 6, 1982,

at 29, col. 3................. 11

N.Y. Times, Nov. 6, 1982,

at 32, col. 5................. 11

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights,

"Affirmative Action in the

1980's: Dismantling the

Process of Discrimination" 35, 38

(1981)......................... 39, 42

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights,

"For All the People . . . By-

All the People" (1969)....... 26

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights,

"Last Hired, First Fired:

Layoffs and Civil Rights"

(1977)..... 31, 32

U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights,

"Women Still in Poverty"

(1979) ........................ 19, 22

Wright, "Color-Blind Theories

and Color Conscious Remedies,"

47 U. Chi. L. Rev. 213

(1980) ............. .. ....... 39, 40

viii

INTEREST AND DESCRIPTION OF

AMICI CURIAE

This brief amicus curiae in support of

respondents is submitted on behalf of the

National Organization for Women; American

Association of University Women; Equal

Rights Advocates, Inc.; League of Women

Voters of the United States; National

Conference of Black Lawyers; National

Women's Law Center; Women Employed; and

Women's Legal Defense Fund.

The National Organization for Women

is the largest feminist organiza

tion in the United States, with a member

ship of over 225,000 women and men in more

than 750 chapters throughout the country.

Since its founding in 1966, a major goal of

NOW has been the eradication of sex dis-

■JU

"Letters from counsel for all parties, con

senting to the filing of this brief, are

being filed with the Clerk.

crimination in employment, and the elimina

tion of barriers that deny women economic

opportunities and the ability to become

economically self-sufficient. NOW believes

that economic equality in the paid workforce

is fundamental to women's ability to achieve

equality in other aspects of society. In

furthering its commitment to that goal, NOW

has participated in numerous cases and com

mented on proposed legislation and regula

tions to secure full enforcement of laws

prohibiting employment discrimination.

The American Association of University

Women is a national organization

of 190,000 college-educated women working

for the advancement of women. Dedicated

for 100 years to promoting the social and

economic well being of all persons, the

AAUW affirms its commitment to equal em

ployment opportunity for women and men.

Equal Rights Advocates, Inc. is a

San Francisco based, public interest le-

2

gal and educational corporation special

izing in the area of sex discrimination.

It has a long history of interest, activ

ism and advocacy in all areas of the law

which affect equality between the sexes.

ERA, Inc. has been particularly concern

ed with gender equality in the workforce

because economic independence is funda

mental to women's ability to gain equal

ity in other aspects of society. This

concern has been expressed through ERA,

Inc.'s participation, both as counsel and

as amicus, in numerous employment dis

crimination cases.

The League of Women Voters of the

United States is a nonpartisan, non

profit membership organization, incorpo

rated under the laws of the District of

Columbia, with a current membership of

113,000 in 1250 state and local Leagues

located in all states, the District of

Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin

3

Islands. Since its inception in 1920, the

League's purpose has been to promote polit

ical responsibility through informed and

active participation of citizens in govern

ment. The League believes that no person

or group should suffer legal, economic, or

administrative discrimination, and is com

mitted to the eradication of discrimination

against minorities and women through af

firmative action.

The National Conference of Black Lawyers

is a membership organization of lawyers,

scholars, legal workers, law students and

other legal activists in the United States

and abroad. The purpose of the organization

is to promote and protect the interests of

Black men and women in all phases of human

life. Among the organization's primary

concerns is the elimination of employment

discrimination and the implementation and

retention of viable affirmative action

programs which serve to promote economic

4

equity for Black men and women in the United

States.

The National Women's Law Center is a

legal organization, located in Washington,

D.C., with the purpose to protect and ad

vance women's rights. The Center repre

sents women's concerns before federal ad

ministrative agencies and courts. The

Center has been involved in issues affect

ing the employment rights of women, and in

particular has handled cases involving em

ployment of women in nontraditional jobs.

Women Employed is a national organi

zation, based in Chicago, with a membership

of 3,000 women workers. Over the past ten

years, the organization has assisted work

ing women with problems of sex discrimina

tion. Women Employed also monitors the

enforcement, actions and policies of the

EEOC and Office of Federal Contract Com-

liance Programs with regard to a broad

range of sex discrimination issues.

5

Women's Legal Defense Fund is a non

profit, tax exempt membership organization,

founded in 1971 to provide pro bono legal

assistance to women who have been discrimi

nated against on the basis of sex. The

Fund devotes a major portion of its resources

to combatting sex discrimination in employ

ment, through litigation of significant

employment discrimination cases, operation

of an employment discrimination counselling

program, public education, and agency ad

vocacy before the EEOC and other federal

agencies that are charged with enforcement

of equal opportunity laws.

These organizations are dedicated to

the principle of equal treatment under the

law and to the elimination of sex and race

discrimination in employment. Amici believe

that the case before the Court is of great

importance to the ability of the federal

courts to provide effective remedies for

employment discrimination.

6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The petitioners in this case ask the

Court to subordinate a judicially-approved

remedial order to a seniority-based layoff

plan which threatened to wipe out the pro

gress made, pursuant to consent decrees

approved by the district court in 1974 and

1980, toward racial and sexual integration

of the Memphis Fire Department. The abil

ity of the federal courts to protect reme

dial decrees, at issue in this case, direct

ly affects the ability of women of all

races and ethnic groups to obtain and main

tain employment in state and local govern

ment services.

Systematic exclusion of women from

employment in the protective services has

been judicially acknowledged, and courts

have acted to remedy the effects of this

* Amici adopt the argument that this case

is moot as contained in the brief for res

pondent .

- 7-

discrimination. Increased availability of

employment in municipal protective ser

vices is a critical factor in the struggle

of many women to be economically self-suf

ficient. One of the most significant cur

rent demographic trends is the dramatic

increase in the poverty of women. Institu

tionalized sex discrimination contributes

to this trend and confines women to low

status, low paying jobs. The serious eco

nomic plight of women underscores the cri

tical importance of removing barriers to

equal employment opportunity.

The national policy to eliminate dis

crimination in both public and private

sectors, through Congressional legislation,

is clear. However, despite enactment of

various statutes prohibiting discrimination,

minorities and women are still struggling

to achieve equality. In addition to hiring

barriers, the "last hired, first fired"

-8-

practice for structuring layoffs dispropor

tionately affects women and minorities in a

way that can eviscerate the modest progress

made to date in integrating the work force.

In order to enforce the broad policies a-

gainst employment discrimination, the courts

must be free to approve affirmative action

plans, taking into consideration the effects

and goals of such plans and the seniority

expectations of the nonminority employees.

District courts are vested with broad

equitable powers. To effectively address

race and sex discrimination, the courts must

retain flexibility and should not be deprived

of the ability to employ practical wisdom in

structuring remedies. In the instant case,

the goals of the 1974 and 1980 consent de

crees had not yet been accomplished when the

layoff proposal was announced. There was

sufficient evidence of discrimination in the

record to support the district court’s order.

-9-

ARGUMENT

POINT I

THIS CASE RAISES ISSUES HAVING

A SIGNIFICANT IMPACT ON WOMEN’S

OPPORTUNITIES TO BECOME ECONOMI-

CALLY SELF-SUFFICIENT________ _

In the instant case, this Court is

presented with some of the consequences

of the pervasive history of race dis

crimination in employment in a uniformed

municipal service. No less severe, how

ever, has been the systematic exclusion

of women of all races from such protec

tive services jobs as firefighting. The

effects of the history of sex discrimi

nation in protective services employ-

-10-

ment are being remedied very slowly.-'

The ability of the federal courts to pro

tect remedial decrees, at issue in

this case, directly affects the ability of

all women to obtain and maintain employ

ment in state and local government services.

Historically, women have been effec

tively barred from state and local uniform

protective services by a variety of practices.

One of the most common policies has been the

complete segregation of women within the

protective services, and their confinement

to a few low-prestige jobs "appropriate” to

their sex.

11

~T7 ----------— *— •— ~—In New York City, for example, the qual

ifying test for firefighters was found to

be sex discriminatory in 1982, N.Y. Times,

Nov. 6, 1982, at 32, col. 5. The first

women recruits for the New York City fire

department entered training on September

22, 1982. N.Y. Times, Nov. 6, 1982, at

29, col. 3, and were sworn in as members

of the force on November 5, 1982. Id.

-11-

[Women] were not permitted to com

pete with men on [police] entrance

examinations. Their eligibility

was limited to a relatively few

positions as 'police women' and

'police matrons'. They were given

limited responsibility, primarily

for processing, searching and care

and custody of women prisoners and

a limited amount of youth work.

They were not used for patrol work.

United States v. City of Chicago,

3H5~Tr“5uppr“543y '548' ‘T^:T)7''TTT7

1974).

Additionally, women have been required to

meet stricter educational criteria than

men, mandating more years of formal educa

tion than men, e.g,, Schaefer v, Tannian,

394 F. Supp. 1128, 1130 (E.D. Mich. 1974)

(police). Moreover, not only have women

been relegated to sex-segregated jobs, some

departments have maintained strict quotas

on the number of women hired. Id. at 1131,

Sex-segregated schedules of entrance ex

aminations have also been maintained, af

fording women substantially fewer opportun

ities than men to apply for the handful

of positions open to them. ' Id, at 1130.

- 12-

As a result of these widespread dis

criminatory practices, the participation

of women in the uniformed state and munic

ipal services has been extremely low. In

I960, women comprised only 4.1% of all

2/workers in protective service occupations,—

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept, of

Labor, Perspectives on Working Women: A

Databook 10, Table 11 (1980), By 1981, the

percentage had risen to 10.17o. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept, of Labor,

Employment and Earnings 141 (March 1982).

Since women now constitute more than 42L

of the paid labor force, these percentages

™_y----- ------ ------- ~

-The Bureau of the Census category of

"protective service" work includes fire

inspection and fire prevention occupations,

firefighting occupations, police and de

tectives, sheriffs, bailiffs and other law

enforcement officers, correctional institu

tion officers, crossing guards, guards and

police. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept,

of Commerce, Classified Index of Industries

and Occupations XlV (Novi 1982).

-13-

reflect a gross underrepresentation of

t7nmpn 3/ women. —

Prior to 1972, when Title VII was

amended to extend coverage to state and

local government employment (Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended

by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972, 42 U.S.C.A. §2000e et se£. (West 1981)),

women were barely employed in the protective

services at all. They constituted less than

3% of police, less than 5% of guards, and

roughly one-half of one percent of all fire

fighters in 1972. Bureau of the Census,

U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Statistical Ab-

------ -----------~—The percentages of women in these occu

pations vary dramatically among occupa

tions, although women are substantially

underrepresented in all. In 1981, women

constituted 0.9% of all firefighters, 5.7%

of all police officers, 7% of all sheriffs

and bailiffs, and 13.7% of all guards.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept, of

Labor, Employment and Earnings 141 (March

1.982).

-14-

stract's of the United States: 1981, 420

(1981). A /

Not surprisingly, since the enactment

of the 1972 amendments, numerous cases al

leging sex discrimination in protective

services employment have been brought in

the federal courts. A sampling of these

cases shows a consistent pattern of denial

of opportunities to women. In 1974, none

of the firefighters in 45 Louisiana munic

ipalities and parishes were women, United

States v. City of Alexandria, 614 F .2d

1358, 1365 n.14 (5th Cir. 1980). In 1974,

women constituted slightly over 2% of the

police officers in Detroit, Schaefer v.

Tannian, 394 F. Supp. at 1130; in 1973,

women comprised less than 17, of the police

A Figures for the category of "sheriffs

and bailiffs" are not available for this

period.

-15-

officers in Chicago, United States v. City

of Chicago, 385 F, Supp. at 548. In 1979,

only 2.37, of the police officers in the

cities of Yonkers and White Plains,. New

York were women, Complaint, United States

v. City of Yonkers, 80 Civ. 7407 (S.D.N.Y.

1979) , although in 1977 more than 207, of

the applicants for officer positions in

White Plains were women. Stipulation, id,

(April 1981). In 1977, only three out of

91 trainees in the Nassau County, New York

police academy were women. Memorandum and

Order, United States v, Nassau County

Police Dept., No, 76 C1869, at 15 (E.D.N.Y.

July 21, 1978)

Women have not been comparably ex

cluded from low-paid, low prestige civilian

clerical and support jobs in the state and

municipal services. In Nassau County, for

example, in 1977 women constituted 0.6%

-------_--------------

—The other 88 trainees were white men.

-16-

of the sworn police department employees,

but 78.9% of the civilian personnel in the

department. Id. at 14.

Faced with clear and dramatic evi

dence of sex discrimination, the federal

courts have found liability and provided

for effective relief, including percentage

hiring goals. See, e.g., United States v.

City of Alexandria, 614 F.2d at 1368 (con

sent decree covering firefighter and police

hiring); Schaefer v. Tannian, 394 F. Supp.

at 1135 (order covering police hiring);

United States v. City of Buffalo, 633 F.2d

643, 647 (2d Cir. 1980) (order covering

firefighter and police hiring); United

States v. City of Philadelphia, 499 F. Supp

1196, 1204 (E.D. Pa. 1980) (injunction cov

ering police hiring). In so doing, the

courts have recognized both the importance

of opening municipal service employment to

women and the necessity of court orders to

-17-

assure the initial and continuing availa

bility to women of these fundamentally im

portant employment opportunities. In

remedying the effects of sex discrimination,

like racial discrimination, rigorous judi

cial scrutiny and remedial action are the

strongest tools to prevent backsliding and

solidifying the progress already made in

the integration of municipal protective

services.

Increased availability of employment

in municipal protective services is

important to the efforts of many women

to become economically self-sufficient.

The desperate economic position of women

in our society--and growing poverty of

women and children generally--is today widely

acknowledged. See, e .g ., Nat'l Advisory

Council on Economic Opportunity. Critical

Choices for the 80's (1980) [hereinafter

cited as Critical Choices]; U.S. Comm'n on

-18-

Civil Rights, Women Still in Poverty

(1979). Nearly one-third of all female

headed households are living below the

poverty line, while only one in 18 male

headed households is in a similar position.

Critical Choices at 17.— In 1980, families

maintained by women alone had the lowest

median annual income of all families. Bur

eau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce,

Characteristics of Households and Persons

Receiving Selected Non-Cash Benefits: 1980

9 (1982) [hereinafter, Characteristics].

The situation is particularly grim for

women with young children. In 1978, the

median income of families headed by women

-^Between 1980 and 1981, the number of poor

families headed by women increased by 231,000,

Bureau of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Com

merce, Money Income and Poverty Status of

Fami 11 e s ^ h Q Wr^Ws^iT~TFie~TIniTeH~~?tate s :

T^ETTAdvance Data'f rom' the'' March, 1982

Current. PopuIatTon Survey) 3, ‘Table B (1982) .

-19-

whose children were under six was only

$4,498, 30% of the median income for all

families with children under six. Bureau

of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce,

Families Maintained by Female Householders

1970-79 36 (1980). The National Advisory

Council on Economic Opportunity has esti

mated that if current demographic trends

continue, this nation's impoverished class

by the year 2,000 will be comprised exclu

sively of women and children. Critical

Choices at 19.

Among the major factors contributing

to the precarious financial position of

women are pervasive sex discrimination and

job segregation in the workforce. Women

comprise 42% of the workforce nationwide.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept, of

Labor, Perspectives on Working Women: A

Databook 3 Table 1 (1980). Yet, they are

-20-

concentrated in a small number of occupa

tions which are marked by low pay and

limited opportunities. In 1981, half of

the 43,000,000 women in the paid labor

force were employed in only 20 occupations.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Dept, of

Labor, Employment and Earnings (March

1982). While 22% of all men were in three

of the major occupation groups (sales,

clerical and service) , 64%, of the women

were employed in these occupations. Bureau

of the Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Wage

and Salary Data from the Income Survey

Development Programs 1979 3 (1982). There

is evidence that the occupational segrega

tion of women is increasing. For example,

in late 1981 almost 75%, of all clerical

workers were women, Bureau of Labor Sta

tistics, U.S. Dept, of Labor, Employment

and Earnings 22 Table A-21 (1982), as com

pared with 62%, in 1950. Bureau of Labor

-21-

Statistics, U.S. Dept, of Labor, Employment

in Perspective: Working Women 1 (Report

No. 544, 1978).

Further, the wages for "women's jobs"

lag behind those categories that are tra

ditionally male jobs. The 1977 weekly wage

for 18 of the "women's jobs" ranged from

$59 for private household workers to $171

for sewers and stitchers. Bureau of Labor

Statistics, U.S. Dept, of Labor, News:

Trends in Weekly and Hourly Earnings for

Major Labor Force Groups, Tables 1-3 (Nov.

2, 1977). In contrast, the 1977 average

weekly wage for male-dominated jobs such as

construction ($297), transportation and

public utilities ($275), and motor vehicle

retailers ($208) was far better. U.S.

Comm'n on Civil Rights, Women Still in

Poverty 19 (1979). But even within pre

dominantly female occupations, women's

wages are significantly below those received

-22-

by men. On average, a female sales worker,

for example, is paid only 52% of x\?ages paid

to a male sales worker, Bureau of the

Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Money Income

of Households, Families, and Persons in the

United States: 1980 Table 55 (July 1982).

Female clerical workers receive only 59%.

of the wages paid to male clerical workers.

Id .

In view of persistent job segregation

and the concomitant wage gap, it is not sur

prising that the median earnings of women

in the paid work force is one half the

median earnings of men. Bureau of the

Census, U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Wage and

Salary Data from the Income Survey Develop

ment Program: 1979 3, Table 1 (1982).

The serious economic plight of women under

scores the critical importance of removing

barriers to equal employment opportunity.

23

It is only through assuring women truly eq

ual access to jobs that we as a society can

reverse these current trends and give women

the real possibility of achieving economic

self-sufficiency for themselves and their

families.

24 -

POINT II

FEDERAL ANTI-DISCRIMINATION

POLICY REQUIRES EFFECTIVE

REMEDIES FOR EMPLOYMENT DIS

CRIMINATION BY GOVERNMENT

EMPLOYERS ______

A. The 1972 Amendments to Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Were

Enacted to Redress Widespread Em

ployment Discrimination In State

and Local Government Employment

This Court has emphatically recog

nized that the intent of Congress, in en

acting Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, was to "assure equality of employ

ment opportunity and to eliminate those

discriminatory practices and devices which

have fostered racially stratified job en

vironments to the disadvantage of minority

citizens." McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Green, 411 U.S. 792, 800 (1973). See also

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193 (1979); Albemarle Paper Co.

v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418-419 (1975);

- 25 ~

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S.

36, 44 (1974); Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424, 429-30 (1971). Just over six

years after the original Act was passed,

Congress in 1972 reaffirmed its commitment

to equal employment opportunity for all

citizens, by amending Title VII to, inter

alia, strengthen the enforcement powers of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion and extend the provisions of the Act

to employees of state and local governments

86 Stat. 103, Sec. 701(f), 42 U.S.C. §2000e

Explaining the need for these amend

ments, the House Report relied on a 1969

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights report— ̂

which found that "widespread discrimina

tion against minorities exist[ed] in state

and local government employment, and that

the existence of this discrimination [was]

— U . S . Cornm’n on Civil Rights, For All The

People ...By All The People, (1969")

26

perpetuated by the presence of both insti

tutional and overt discriminatory prac

tices." H.R. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.

(1971), reprinted in 1972 U.S. Code Cong.

& Ad. News 2137, 2152.

The House Report further noted that

this type of employment discrimination was

"particularly acute and had the most dele

terious effect," id. at 2153, since it was

being practiced in the governmental activ

ities that were "most visible to the minor

ity communities (notably education, law

enforcement, and the administration of

justice)..." Id.

The Chairman of the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission voiced a similar

concern in testimony before the House of

Representatives regarding the proposed

amendments, noting that the "failure of

state and local agencies to accord equal

employment to their employees is particu

larly distressing in light of the impor

27 -

tance that these agencies play in the daily

lives of the local communities...." Equal

Employment Opportunities Enforcement Act

of 1971, Hearings on S.2515, 2619, H.R.

1746 Before the Subcomm. on Labor of Senate

Comm, on Labor & Public Welfare, 92d Cong.

(1971).

Nowhere are these concerns more evi

dent or troublesome than in the continuing

and almost total exclusion of women and

minorities from local protective service

departments--agencies closely identified

with the overall protection of the public,

and therefore perhaps the most visible of

all occupations.

-28-

B. Government Employment Practices,

Such As Seniority-Based Lay-Off

Plans, Cannot Be Allowed To Frus

trate Efforts To Remedy Discrim-

inat ion. ______________

1. The use of the "last hired-

first fired" principle to reduce

employment in times of economic

recession has a disproportionate

impact on minorities and women.

Despite the enactment of federal,

— ^Amici recognize, of course, the im

munity afforded bona fide seniority plans

under §703(h) of Title VII by this Court's

ruling in Teamsters v. United States, 431

U.S. 324 (1977). At issue in this case,

however, is not the lawfulness, under

Title VII, of the seniority system of the

City of Memphis fire department, but

rather the appropriateness, under Title

VII remedial principles, of relief which

implicates a seniority plan. It is in this

context only that amici urge a temporary

restructuring of the "last hired-first

fired" principle.

- 29

state, and local statutes and presidential

orders which prohibit discrimination in

e m p l o y m e n t e q u a l employment opportuni

ty remains an unrealized goal for many of

this country's minority and women paid

workers. For these people, serious barriers

to their entrance into and continued participa

tion in the paid job market continue to

exist. Significant among these is the

"last hired, first fired" practice for

structuring layoffs, which has dispropor

tionately affected minorities and women,

particularly during our nation's most

recent economic troubles. As the

— ■/See, e.g. , 42 U.S.C.A. §1981 (West 1981);

42 UTS.C.A. §1983 (West 1981); Title VI,

§601 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C.A. §2000d (West 1981); Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended by the

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972,

42 U.S.C.A. §2000e et. seq. (West 1981);

Exec. Order 11246, 30 Fed.Reg. 12319 (1965),

as amended by Exec. Order 11375, 32 Fed.

Reg. 14303 (1976); Public Works Employment

Act of 1977, 42 U.S.C.A. §6705(f)(2)(West

1983).

-30-

United States Commission on Civil Rights

pointed out in its 1977 Report Last Hired,

First Fired: Layoffs and Civil Rights 1,

(1977) [hereinafter cited as Last Hired,

First Fired]:

The long and extensive use of this

policy by employers is one reason

why income remains consistently

lower and unemployment rates high

er for these groups than for the

labor force as a whole.

See Point I, supra.

Review of the impact of the 1974-75

recession on the employment status of

minority and women workers highlights the

devastating effects which can result from

such layoffs. Between the end of 1973

and mid-year 1975, the unemployment rate

for adult women rose steadily from 5.9%

to 8.5%. Last Hired. First Fired at 10.

Jobless rates reached 14.3%, for non-whites,

and 12.4%, for Hispanic workers by mid-

1975, as compared to 8.2% for white work

ers generally. Id.

_ 31 _

Unemployment resulting from layoffs

during that time period rose most sharply

in those blue collar occupations where

minority employees were most likely to be

concentrated. Id. While the concentration

of women workers in trade and services in

dustries cushioned the impact of layoffs

for women employees overall,— ̂ nonetheless,

women who had broken into traditionally male

jobs such as the assembly line of automo

bile plants or as patrol officers on police

forces, were heavily affected by job loss.

Id. Moreover, in some industries where

minorities represented only 10-12% of the

workforce, they accounted for 60-707, of

those workers laid off in 1974. Id. at

24-25.

— ^Cyclical changes in employment rates

are generally less dramatic in trade and

services than in goods-producing indus-

tries. Last Hired, First Fired at 11.

- 32

The Impact of layoffs on government

employees has been no less severe. For

example, in mid-1975, the New York City

Police Department laid off 371 of its

680 female police officers, out of a total

force of almost 26,000. Id. Over half of all

Hispanic workers in New York City lost

their jobs between 1974 and 1975. Id.

More recently, minority workers have

accounted for 2335 of the 2944 layoffs of

public sector employees ordered in

Detroit between 1980-82. Bureau of

National Affairs, Layoffs, Rifs, and EEO

in the Public Sector: A BNA Special Report

_ 33

23 (February 1982). — ^

In April 1975, the United States

Department of Labor reported that "recently

hired workers, including many women and minority

1X7-----------------------------------— Federal employees have fared no better.

In 1981, 11,845 employees of the Federal

government were laid off because of budget

cuts. Bureau of National Affairs, Layoffs,

Rifs, and EEO In The Public Sector: A BNA

Special Report 5 (February 1983). These"

layoffs were 50% higher for minority

employees than non-minority employees. Id.

Among administrative employees, women were

laid off at a rate 61%, greater than men;

minority workers in administrative posi

tions experienced layoffs at a rate 3.5

times the average rate. Id. In the first

two quarters of 1982, 5321 federal employ

ees were laid off; nearly 63% of these

laid off employees were women, and women

and minority men together comprised nearly

807, of the layoffs. Summary of Task Force

RIF Survey, Quarter 1 and Quarter 2 Fiscal

Year 1982. (Federal Government Service

Task Force). In the third quarter of 1982,

1393 federal employees were laid off,

50.6% of whom were women. The combined

percentage of women and minorities laid

off was 70.9%. Reduction In Force Survey

Third Quarter Fiscal Year 1982 (Federal

Government Service Task Force).

34 _

group members, have become early casualties

of the economic downturn." Last Hired,

First Fired at 10. Statistics reflecting

the most recent federal layoffs, supra n. 11,

demonstrate that the effects of the current

recessionary cycle on the employment patterns

of women and minorities are similarly

disproportionate and injurious. Clearly,

if affirmative measures designed to counter

act these results are not instituted and

adopted, "the opportunties [for women and

minorities] laboriously created in the 70's

may be destroyed during hard times in the

80's." U.S. Comm'n on Civil Rights,

Affirmative Action In the 1980's: Dis

mantling The Process of Discrimination 36

(1981) [hereinafter cited as Affirmative

Action].

Strict adherence to the last hired,

first fired policy of layoffs "locks in"

the effects of past discrimination by

35

continuing the advantage white males gain

ed in employment as a direct result of

minimal or no competition from women and

minorities in the past.

2. Courts must be free to impose

affirmative color-conscious or

gender-conscious remedies if they

are to fully effectuate the broad

public policy against employment

discrimination.

In deciding that under §706(g) the

provision of retroactive seniority was

"generally appropriate" as a remedy for

hiring discrimination, this Court carefully

considered the effect of an affirmative rem

edy on incumbent employees. Franks v, Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 799 (1976).

It found "untenable the conclusion that

this form of relief may be denied merely

because the interests of other employees

may thereby be affected." 424 U.S. at 755.

The Court recognized that retroactive

seniority could affect the expectations

and prospects of other employees,

- 36

but concluded that the importance of the

remedy was paramount. 424 U.S. at 777-78.

The result of the remedy approved in

Franks is the possibility that some white

male workers who have been on the job for

some time may find themselves, in hard

times, losing economic benefits, or even

being laid off, as a result of seniority-

based relief ordered.

In the instant case, the effect of the

district court's order on the department's

seniority system was minor. No black fire

fighter with less seniority than a white

firefighter retained his job while the

white firefighter was laid off. Brief of

Petitioners Memphis Fire Department at A4.

Approximately 29 white firefighters were

bumped to a lower position where minority

firefighters with the same amount of

seniority were not. Id. at A5-9.

But, the fact that some individual

white males may be disadvantaged by a

37

court-ordered temporary bypass of seniority

in times of layoffs should not preclude a

court from authorizing such affirmative

relief. For this Court to allow its deter

mination of an appropriate remedy to be

governed by the expectations of individual

white male firefighters is to ignore the

overall fairness of the plan, and the fact

that affirmative measures "often produce

changes in our institutions that are bene

ficial to everyone, including white males."

Affirmative Action at 36.

Nor should this Court be troubled by

assertions of "reverse discrimination" by

opponents of such affirmative remedies.

Such charges are mere smokescreens designed

to undermine full and effective enforcement

of congressional intent to end race and sex

discrimination in employment: "[T]he

charge of 'reverse discrimination', in

essence, equates efforts to dismantle the

process of discrimination with that process

38

itself. Such an equation is profoundly and

fundamentally incorrect." Affirmative

Action at 41.

Adherents of color-blind or gender-

neutral solutions to discrimination "[ig

nore] the context in which the problem of

inequality has persisted in this country..

.." Wright, Color-Blind Theories and

Color Conscious Remedies, 47 U. Chi. L. Rev.

213, 214 (1980)(hereinafter Wright) .

Discrimination is "an interlocking process

involving the attitudes and actions of

individuals and the organizations and

social structures that guide individual

behavior.” Affirmative Action at 13.

Discrimination in employment simply cannot

be equated solely with individual prejudice

or expressions of bias, for when the forces

of individual attitudes and actions, in

combination with those of organizations

and relevant social structures "are at work

anti-discrimination remedies that insist

39

on 'color-blindness' and 'gender-neutral

ity' are insufficient." Id. at 2,

Moreover, it is clear that Congress, in

enacting anti-discrimination legislation

has rejected a "color-blind" or "gender-

neutral" theory of government, and directed

government to employ its power to eradicate

it. As Judge Skelly Wright has emphatical

ly remarked, "to call such legislation

'color-blind' is a meaningless abstraction.

Legislation against invidious discrimina

tion helps one race and not the other be

cause one race and not the other needs such

help." Wright at 220-21.

Decisions of this Court demonstrate its

sensitivity to and agreement with the prin

ciples discussed above. As Justice Blackmun

stated in his opinion in Regents of the Univ

of Calif, v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 407 (1978)

"[i]n order to get beyond racism, we must

first take account of race....And in order

to treat persons equally, we must treat

40

them differently. We cannot— we dare not—

let the equal protection clause perpetuate

racial supremacy." Likewise, in United

Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 (1979), Justice Brennan refused to adopt

a literal interpretation of §§703(a) and

(d) of Title VII, which would have neces

sarily prohibited all race-conscious affirm

ative actions plans:

The prohibition against racial

discrimination in §§703(a) and (d)

of Title VII must therefore be read

against the background of the

legislative history of Title VII

and the historical context from

which the Act arose...Examina

tion of those sources makes clear

that an interpretation of the

sections that forbade all race

conscious affirmative action

'would bring about an end com

pletely at variance with the

purpose of the statute' and must

be rejected...(citations omitted)

See also Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S.

448 (1980)(upholding as constitutional a

provision of the Public. Works Employment

Act of 1977 that required state or local

governments to use 107> of federal funds

41

granted for public works contracts to pro

cure services or supplies from minority-

owned or controlled businesses).

In the difficult economic circum

stances we now face, the teachings of thi

Court's cases on the importance of remedy

ing discrimination must not be forgotten.

In this charged atmosphere, there

is a strong temptation to view

affirmative action as pitting the

rights of minorities and women

against white males in a battle

over diminishing resources. The

challenge, however, is to maintain,

indeed, to advance our commitment

to equality without asserting one

equity over another.

Affirmative Action at 6.

42

POINT III

THE DISTRICT COURT'S ORDER

WAS NOT AN ABUSE OF DISCRETION

AND SHOULD BE UPHELD

A. Equitable Pvelief Will Be Disturbed

Only If It Constitutes An Abuse

Of Discretion By the Lower Court

This Court has made clear that appel

late review of the issuance of equitable

relief is limited to determination of whether

the district court abused its discretion,

and will be disturbed only if evidence is

insufficient to support the court's action.

Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers v.

Missouri-Kansas-Texas R.R. Co., 363 U.S.

528, 535 (1960); Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 446 (1975)(Rehnquist,

J. concurring). "In shaping equity decrees,

the trial court is vested with broad discre

tionary power; appellate review is corre

spondingly narrow." Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411

U.S. 192, 200 (1973); accord Swann v.

43

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S.

1, 15 (1971); International Salt Co. v.

United States, 332 U.S. 392, 400-01 (1947).

Basic tenets of equity require a sensi

tive weighing of practicalities and balanc

ing of public and private interests. As

this Court has often noted:

The essence of equity juris

diction has been the power

of the chancellor to do equity

and to mould each decree to

the necessities of the partic

ular case. Flexibility rather

than rigidity has distinguished

it. The qualities of mercy

and practicality have made

equity the instrument for

nice adjustment and reconcili

ation between public and private

needs as well as between

competing private claims.

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Ed.,

402 U.S. at 15, quoting Hecht Co. v. Bowles,

321 U.S. 321, 329-30 (1944). See also Lemon

v, Kurtzman, 411 U.S. at 200.

Subsequent modification of equitable

relief requires broad discretion. System

Fed1n No. 91, Ry. Emp. Dept, v. Wright, 364

44 -

U.S. 642, 647-48 (1961); cf. Browder v. Di

rector, 111. Dept, of Corrections, 434 U.S. 25 7,

263 n.7 (1978) (appellate review under Fed. R.

Civ. P. 60 (b)) .

Because district judges are "uniquely

situated... to appraise the societal forces

at work in the communities where they sit,"

Columbus Bd. of Ed. v. Penick, 443 U.S. 449,

470 (1979)(Stewart, J., concurring),

appellate review of equitable relief also

requires deference to the judgment of the

district court. See,e.g., Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., Inc., 424 U.S. 747, 779-

80 (1976); Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Bd. of Ed., 402 U.S. at 12. In addition,

the district judge has the unique experience

of having managed the litigation in the past.

See, e.g., Brown v. Board of Ed., 349 U.S.

294, 299 (1955).

Consistent with these principles of

equity, the district courts must necessarily

45

retain flexibility to effectively address

the varied situations which they confront.

The rules governing eradication of race and

sex discrimination should not be rigid and

absolute. The district courts must not be

deprived of the capacity to employ practical

wisdom in fashioning remedies. The district

court's order in this case was wholly appro

priate and within the sound discretion of

the court, and therefore should be upheld.

B. The District Court’s Order Was

Grounded Upon Sufficient Evidence

of Discrimination And Therefore

Was Not An Abuse of Discretion

The evidence of discrimination in the

Memphis Fire Department contained in the record be

fore the district court in the instant case was a

sufficient basis for the district court's in

junction. For example, between 1950 and

1976, the fire department hired only 94

black firefighters as compared to 1683 white

firefighters. Between 1969 and 1975 only

46

7 black firefighters received promotions as

compared to 386 white firefighters. In 1979,

blacks constituted only two out of 25 admin

istrative personnel, 6 out of 26 apparatus

maintenance workers, 7 of 89 ambulance

service personnel, 8 of 37 fire prevention

workers and 3 of 50 communications workers.

There were no black employees in the train

ing and water or air mask service categories.

Eight of the thirteen material service work

ers were black. Stotts v. Memphis Fire Depart

ment, 679 F .2d 541, 550-51 n.5 (6th Cir. 1982).

In fact, the evidence was so striking

that both the district court and the court

of appeals commented on it. The district

court, when modifying the 1980 consent decree

observed:

While the agreement does not

admit discrimination, it

would be naive not to realize

47

that the Fire Department of

this City was very discrim

inatory towards black people

for years, and it wasn't

corrected properly until the

Consent Decree was entered

into this case.

It is true that this

Court never had hearings and

made findings, but I could

take judicial notice of that

from the figures that are in

the record of this Court.

Petition For a Writ of Certiorari at A73.

Indeed, the court thought the history of

discrimination so apparent that it was com

pelled to note "that the present situation

resulted from prior discrimination, which

is obvious." Id. at A76.

The Sixth Circuit, reviewing the dis

trict court's ruling found "[t]he statistics

contained in this record represent a very

strong prima facie case of employment dis

crimination." Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept.,

679 F.2d at 550-51 n.5. Examining the

statistics included in the record, the court

noted a revealing sign of purposeful dis

48

crimination in hiring, that "[i]n the spring

of 1981, blacks constituted only 11 percent

of the Memphis Fire Department. Approximate

ly 35 percent of the City of Memphis is

black." Id.

Faced with similar statistical dispar

ities, other courts of appeals have endorsed

similar affirmative relief through consent

decrees to overcome the effects of past dis

crimination. See, e .g ., United States v.

City of Miami, Fla., 614 F.2d 1322 (5th Cir.

1980), mod. in part on other grounds, 644

F.2d 435 (5th Cir, 1 9 8 1 ) (approval of consent

decree affording affirmative relief based

on statistical disparities in racial compo

sition) ; United States v. City of Alexandria,

614 F .2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1980)(approval of

consent decree affording affirmative action

based on statistical disparities in racial

composition).

49

C. The District Court, Pursuant To Its

Duty To Enforce The Decree And Its

Authority To Modify It In Light Of

Changed Circumstances, Did Not Abuse

Its Broad Equitable Powers__________

The lower court was confronted with a

situation, engendered by the Mayor's pro

posed layoffs, that would have significantly

undermined the consent decrees. Both the

goals of the 1974 and 1980 consent decrees,

approved by the court, were explicit:

The City, therefore agrees

to undertake as its long term

goal in this decree, subject

to the availability of quali

fied applicants, the goal of

achieving throughout the work

force proportions of black and

female employees in each job

classification, approximating

their respective proportions

in the civilian labor force.

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Dept., 679 F.2d at

571. The 1980 decree was intended to paral

lel and supplement the 1974 decree. Id. at

548. The 1980 decree underscored and re

affirmed the goal of the 1974 decree

particularly as it applied to representa-

50

tion of black citizens: "the goal shall be

to raise the black representation in each

job classification on the fire department to

levels approximating the black proportion of

civilian labor in Shelby County." Id. at 576.

The goal of the 1974 and 1980 consent

decrees had not been accomplished when the

Mayor issued his order regarding layoffs.

The effect of the Mayor's proposed layoff

policy on the ongoing goal

of increasing the number of minorities in

the department would have been drastic:

"fifty-five percent of all minority Lieuten

ants and 467o of all minority Drivers would

either have been laid off or demoted had the

layoffs occurred. ̂ Id. at 549-50.

The lower court was under an obligation

~Y2j '— In addition to eradicating the progress

made pursuant to the consent decrees, the

City's plan had the potential for perpetu

ating discrimination in other city agencies

by taking into account, in determining sen

iority, an employee's prior service in

another agency.

51

to assure implementation of the goals of

the consent decrees to increase the percent

age of black employees in the fire depart

ment and to alleviate the effect of past

discriminatory policies, and therefore

expressly retained jurisdiction in the

decree. According to Section 17 of the

1980 decree, "The Court retains jurisdic

tion of this action for such further orders

as may be necessary or appropriate to

effectuate the purposes of this decree."

Id. at 578.

As fully discussed above, the Mayor's

proposal not only would have halted progress

towards achieving that goal, but also would

have sanctioned backsliding, thereby elimin

ating much of the progress already made. In

view of this probable result, the district

court's order was necessary to slow any back

ward movement that might occur. See U .S . v.

Armour Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1981).

52

Further, there is no question that the

district court had inherent power to modify

its equitable relief to adapt to new or

changed circumstances. United States v.

United Shoe Corp., 391 U.S. 244, 251 (1968);

System Fed. No. 91, Ry. Emp. Dept, v. Wright,

364 U.S. 642, 647-48 (1961). The sudden

layoffs--indeed, the first in the City's

history--which were to occur in Memphis

within several years after the signing of

the remedial consent decree, posed an unfore

seen threat to the ongoing remedy. As dis

cussed above, had the layoffs been permitted,

substantial eradication of all progress

under the decree easily could have resulted

without a modification of the remedial orders.

In these circumstances, modification

of the prior consent decree was appropriate

and necessary in order to prevent the sub

stantial undoing of the remedy. Brown v.

Neeb, 644 F.2d 551, 560 (6th Cir. 1981);

Perrotte v. Percy, 489 F.Supp. 212, 214

53

(E.D. Wise. 1980); Bolden v. Pennsylvania

State Police, 73 F.R.D. 370, 372 (E.D. Pa.

1976), aff'd, 578 F.2d 912 (3d Cir. 1978).

The district court's decision represents

that "special blend of what is necessary,

what is fair, and what is workable,"

Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192, 200 (1973),

that characterizes equitable remedies.

Thus, the order did not prohibit layoffs of

sworn personnel altogether. Cf. Schaefer v.

Tannian, 538 F„2d 1234 (6th Cir. 1976)(dis

trict court improperly enjoined layoff of

male police officers; injunction against

layoff of female officers was proper). It

did not ban the layoff of all minority fire

fighters. The order did not require any

additional measures of affirmative action,

or require that white firefighters be re

placed by new minority hirees. It merely

sought to preserve the remedial status quo

achieved through the consent decrees in the

face of an unexpected fiscal exigency, accord,

54

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v. Members of the

Bridgeport C.S, Comm'n, 482 F.2d 1333, 1341

(2d Cir. 1973); Detroit Police Officers

Ass1n v. Young, 608 F.2d 671, 696 (6th Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 452 U.S. 938 (1981),

which threatened to frustrate the progress

made under the consent decrees. It did not

overbear "the interests of state and local

authorities in managing their own affairs..."

Milliken v. Bradley, 433 U.S. 267, 281 (1977).

The district court's reasonable mod

ification of the consent decrees is not in

valid simply because it involved suspending

the operation of the city's last-hired,

first-fired layoff proposal. The mere

existence of a seniority-based layoff plan

cannot diminish "the scope of a district

court's equitable powers to remedy past

wrongs.... for breadth and flexibility are

inherent in equitable remedies." Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 15 (1971). Nor is the scope of

55

the remedial power under §706(g) of Title

VII, 42 U.S.C.A §2000e-5(g)(West 1981),

limited or qualified by the Congressional

policy expressed in §703(h) of Title VII,

42 U.S.C.A. §2000e-2(h)(West 1981), of pro

tecting bona fide seniority systems from

attack as discriminatory. Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 758-59

(1976) .

In flanks, this Court made clear that,

in cases dealing with seniority systems,

there is a significant "difference between

a remedy issue and a violation issue,"

United Air Lines, Inc, v. Evans, 431 U.S.

553, 559 (1977). The instant case does not

challenge the Memphis seniority-based plan

as discriminatory, clearly distinguishing

this case from the situation presented in

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977) . Respondents, as well as the lower

courts, focused exclusively on preserving

the effectiveness of the remedy for the

56

initial violation, discriminatory hiring

of minorities and women. See, Franks, 424

U.S. at 758.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated above, amici

respectfully submit that the judgment below

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Marsha Levick

Judith I . Avner

Counsel of Record

NOW Legal Defense and

Education Fund

132 West 43 Street

New York, New York 10036

(212) 354-1225

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

Counsel gratefully acknowledge the assis

tance of Mayo Schreiber, Jr., Marcia Sells,

Anne E. Simon, Noemi Bonilla, John Copoulos

Siobhcin Cronin, and Lee G. Basher in the

preparation of this brief.

57

RECORD PRESS, INC., 157 Chambers St., N.Y. 10007 (212) 243-5775