Johnson, Jr. v. Railway Express Agency, Inc. Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 19, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson, Jr. v. Railway Express Agency, Inc. Opinion, 1975. fc580641-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/22410dfa-4640-46c3-83a7-ea8b7613ce51/johnson-jr-v-railway-express-agency-inc-opinion. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

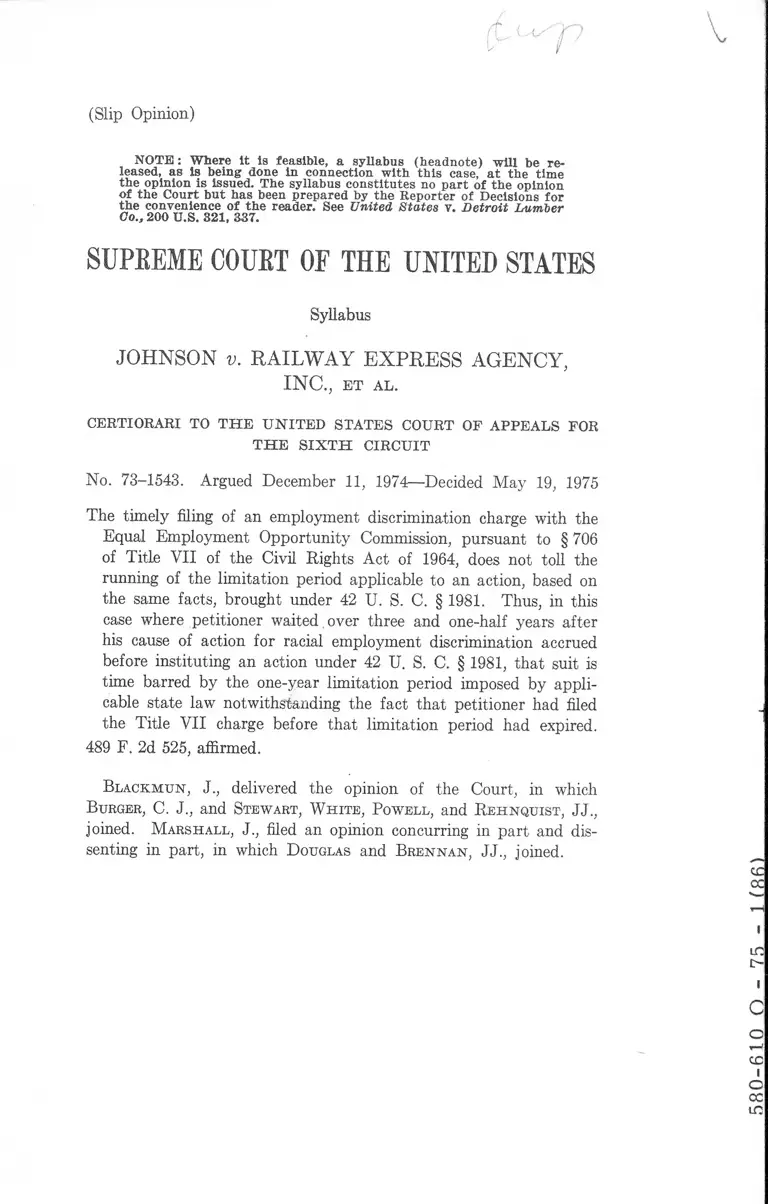

(Slip Opinion)

N O T E : W here i t is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) w ill be re

leased, as is being done in connection w ith th is case, a t the tim e

th e opinion is issued. The syllabus constitu tes no p a r t of th e opinion

of the C ourt b u t has been prepared by th e R eporter of Decisions for

the convenience of th e reader. See United S ta tes v. D etroit Lum ber

Co., 200 U.S. 321, 337.

SUPBEME COUET OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY,

INC., ET AL.

CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS FOR

T H E SIX TH CIRCUIT

No. 73-1543. Argued December 11, 1974—Decided May 19, 1975

The timely filing of an employment discrimination charge with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, pursuant to § 706

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, does not toll the

running of the limitation period applicable to an action, based on

the same facts, brought under 42 U. S. C. § 1981. Thus, in this

case where petitioner waited , over three and one-half years after

his cause of action for racial employment discrimination accrued

before instituting an action under 42 U. S. C. § 1981, that suit is

time barred by the one-year limitation period imposed by appli

cable state law notwithstanding the fact that petitioner had filed

the Title VII charge before that limitation period had expired.

489 F. 2d 525, affirmed.

Blackmun, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which

Burger, C. J., and Stewart, White, Powell, and Rehnquist, JJ.,

joined. Marshall, J., filed an opinion concurring in part and dis

senting in part, in which Douglas and Brennan, JJ., joined.

NOTICE : This opinion is subject to form al revision before publication

m the prelim inary p rin t of the United S tates Reports. Readers are re

quested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the

United S tates, W ashington, D.C. 20543, of any typographical or other

form al errors, in order th a t corrections may be made before the pre

lim inary p rin t goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 73-1543

Willie Johnson, Jr.,

Petitioner,

v.

Railway Express Agency,

Inc., et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[May 19, 1975]

M r. J ustice B lackm un delivered th e opinion of the

Court.

This case presents the issue whether the timely filing

of a charge of employment discrimination with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), pursu

ant to § 706 of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U. S. C. § 2000e-5, tolls the running of the period of

limitation applicable to an action, based on the same

facts, instituted under 42 U. S. C. § 1981.

I

Petitioner, Willie Johnson, Jr., is a Negro. He started

to work for respondent, Railway Express Agency, Inc.,

now, by change of name, REA Express, Inc. (REA), in

Memphis, Tennessee in the spring of 1964 as an express

handler. On May 31, 1967, while still employed by REA,

but now as a driver rather than as a handler, petitioner,

with others, timely filed with the EEOC a charge that

REA was discriminating against its Negro employees

with respect to seniority rules and job assignments. He

also charged the respondent unions, Brotherhood of Rail

way Clerks Tri-State Local and Brotherhood of Railway

Clerks Lily of the Valley Local, with maintaining racially

2 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

segregated memberships (white and Negro respectively).

Three weeks later, on June 20, REA terminated peti

tioner’s employment. Petitioner then amended his

charge to include an allegation that he had been dis

charged because of his race.

The EEOC issued its “Final Investigation Report” on

December 22, 1967. App. 14a. The report generally

supported petitioner’s claims of racial discrimination. It

was not until more than two years later, however, on

March 31, 1970, that the Commission rendered its de

cision finding reasonable cause to believe petitioner’s

charges. And 9% more months went by before the

EEOC, on January 15, 1971, pursuant to 42 U. S. C.

§ 2000e-5 (e), as it then read, gave petitioner notice of

his right to institute a Title VII civil action against the

respondents within 30 days.1

After receiving this notice, petitioner encountered some

difficulty in obtaining counsel. The United States Dis

trict Court for the Western District of Tennessee, on

February 12, 1971, permitted petitioner to file the right-

to-sue letter with the court’s clerk as a complaint, in

satisfaction of the 30-day requirement. The court also

granted petitioner leave to proceed in forma pauperis

and it appointed counsel to represent him. On March

18, counsel filed a “Supplemental Complaint” against

REA and the two unions, alleging racial discrimination

on the part of the defendants, in violation of Title VII

of the 1964 Act and of 42 U. S. C. § 1981. The unions

and REA respectively moved for summary judgment or,

in the alternative, for dismissal of all claims.

The District Court dismissed the § 1981 claims as 1

1 The applicable statute later was amended to allow a period of

90 days, after issuance of the notice, in which to bring the Title YII

action. 42 U. S. C. § 2000e—5 (f) (1), as amended by Pub. L.

92-261, §4 (a), 86 Stat. 104, 106 (1972).

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 3

barred by Tennessee’s one-year statute of limitations.

Tenn. Code § 28-304.2 Petitioner’s remaining claims

were dismissed on other grounds.3

In his appeal to the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit, petitioner, with respect to his § 1981

claims, argued that the running of the one-year period

of limitation was suspended during the pendency of his

timely filed administrative complaint with the EEOC

under Title VII. The Court of Appeals rejected this

argument. 489 F. 2d 525 (1973). See also Jenkins v.

General Motors Corp., 354 F. Supp. 1040, 1045-1046

(Del. 1973). Because of an apparent conflict between

that ruling, and language and holdings in cases from

other circuits,4 we granted certiorari restricted to the

2 “28-304. Personal tort actions—Malpractice of attorneys—

Civil rights actions—Statutory penalties.—Actions for libel, for

injuries to the person, false imprisonment, malicious prosecution,

criminal conversation, seduction, breach of marriage promise, actions

and suits against attorneys for malpractice whether said actions are

grounded or based in contract or tort, civil actions for compensa

tory or punitive damages, or both, brought under the federal civil

rights statutes, and actions for statutory penalties shall be com

menced within one (1) year after cause of action accrued.”

3 The District Court also based its dismissal of petitioner’s § 1981

claim against REA on the alternative ground that he had failed to

exhaust his administrative remedies under the Railway Labor Act,

45 U. S. C. c. 8. App. 102a. The Court of Appeals did not address

the exhaustion argument. Inasmuch as we limited our grant of

certiorari to the limitation issue, 417 U. S. 929 (1974), we have

no occasion here to express a view as to whether a § 1981 claim of

employment discrimination is ever subject to a requirement that

administrative remedies be exhausted.

The claims against the unions were dismissed on res judicata

grounds. App. 101a. The Court of Appeals agreed with that

disposition. 489 F. 2d 525, 530 n. 1 (CA6 1974). This issue, also,

was not included in our grant of certiorari.

4 See, e. g., Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contracting Co.,

437 F. 2d 1011, 1017 n. 16 (CA5 1971); Macklin v. Spector Freight

4 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

limitation issue. We invited the Solicitor General to file

a brief as amicus curiae expressing the views of the

United States. 417 U. S. 929 (1974).

II

A. Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was en

acted “to assure equality of employment opportunities

by eliminating those practices and devices that discrimi

nate on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin.” Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U. S.

36, 44 (1974). It creates statutory rights against invid

ious discrimination in employment and establishes a

comprehensive scheme for the vindication of those rights.

Anyone aggrieved by employment discrimination may

lodge a charge with the EEOC. That Commission is

vested with the “authority to investigate individual

charges of discrimination, to promote voluntary compli

ance with the requirements of Title VII, and to institute

civil actions against employers or unions named in a dis

crimination charge.” Ibid. Thus, the Commission itself

may institute a civil action. 42 U. S. C. (1970 ed.,

Supp. I l l ) § 2000e-5 (f)(1). If, however, the EEOC is

not successful in obtaining “voluntary compliance” and,

for one reason or another, chooses not to sue on the

claimant’s behalf, the claimant, after the passage of 180

days, may demand a right-to-sue letter and institute the

Title VII action himself without waiting for the comple

tion of the conciliation procedures. 42 U. S. C. (1970

ed., Supp. I l l ) §2000e-5 (f)(1). See H. R. Rep. No.

238, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., 12 (1971); McDonnell Douglas

Corp. v. Green, 411 U. S. 792 (1973).

In the claimant’s suit, the Federal District Court is

empowered to appoint counsel for him, to authorize the

Systems, Inc., 156 U. S. App. D. C. 69, 84-85, n. 30, 478 F. 2d 979,

994^995 n. 30 (1973).

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 5

commencement of the action without the payment of

fees, costs, or security, and even to allow an attorney’s

fees. 42 U. S. C. (1970 ed., Supp. I l l ) § 2000e-5 (f)(1)

and 42 U. S. C. § 2000e-5 (k). Where intentional engage

ment in unlawful discrimination is proved, the court

may award backpay and order “such affirmative action

as may be appropriate.” 42 U. S. C. (1970 ed., Supp.

I l l ) § 2000e-5 (g). The backpay, however, may not be

for more than the two-year period prior to the filing of

the charge with the Commission. Ibid. Some district

courts have ruled that neither compensatory nor puni

tive damages may be awarded in the Title VII suit.5 6

Despite Title VIPs range and its design as a compre

hensive solution for the problem of invidious discrimina

tion in employment, the aggrieved individual clearly is

not deprived of other remedies he possesses and is not

limited to Title VII in his search for relief. “ [T]he

legislative history of Title VII manifests a congressional

intent to allow an individual to pursue independently

his rights under both Title VII and other applicable

state and federal statutes.” Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Co., 415 U. S., at 48. In particular, Congress

noted “that the remedies available to the individual

under Title VII are coextensive with the indivdual’s

[sic] right to sue under the provisions of the Civil Rights

Act of 1866, 42 U. S. C. § 1981, and that the two pro

cedures augment each other and are not mutually exclu

sive.” H. R, Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 19

(1971). See also S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.,

24 (1971). Later, in considering the Equal Employ-

5 Loo v. Gerarge, 374 F. Supp. 1338, 1341-1342 (Haw. 1974);

Howard v. Lockheed-Georgia Co., 372 F. Supp. 854, 855-856 (ND

Ga. 1974); Van Hoomissen v. Xerox Corf., 368 F. Supp. 829, 835-

838 (ND Cal. 1973). Cf. Humphrey v. Southwestern Portland

Cement Co., 369 F. Supp. 832, 842-843 (WD Tex. 1973), rev’d on

other grounds, 488 F. 2d 691 (CA5 1974).

6 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

ment Opportunity Act of 1972, the Senate rejected an

amendment that would have deprived a claimant of any

right to sue under § 1981. 118 Cong. Rec. 3371-3373

(1972).

R. Title 42 U. S. C. § 1981, being the present codifica

tion of § 1 of the century-old Civil Rights Act of 1866,

14 Stat. 27, on the other hand, on its face relates pri

marily to racial discrimination in the making and en

forcement of contracts. Although this Court has not spe

cifically so held, it is well settled among the federal

courts of appeals 6—and we now join them—that § 1981

affords a federal remedy against discrimination in private

employment on the basis of race. An individual who

establishes a cause of action under § 1981 is entitled to

both equitable and legal relief, including compensatory

and, under certain circumstances, punitive damages.

See, e. g., Caperci v. Huntoon, 397 F. 2d 799 (CA1), cert,

denied, 393 U. S. 940 (1968); Mansell v. Saunders, 372

F. 2d 573 (CA5 1967). And a backpay award under

§ 1981 is not restricted to the two years specified for

backpay recovery under Title VII.

Section 1981 is not coextensive in its coverage with

Title VII. The latter is made inapplicable to certain

employers. 42 U. S. C. §2000e(b). Also, Title VII

offers assistance in investigation, conciliation, counsel,

waiver of court costs, and attorney’s fees, items that are

unavailable at least under the specific terms of § 1981.

0 Young v. International Tel. & Tel. Co., 438 F. 2d 757 (CA3

1971); Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F. 2d

1377 (CA4), cert, denied, 409 U. S. 982 (1972); Caldwell v. Na

tional Brewing Co., 443 F. 2d 1044 (CA5 1971), cert, denied, 405

U. S. 916 (1972); Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F. 2d 500 (CA6

1974); Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427 F. 2d 476 (CA7), cert,

denied, 400 U. S. 911 (1970); Brady v. Bristol-Meyers, Inc., 459

F. 2d 621 (CA8 1972); Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc.,

supra.

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 7

III

Petitioner, and the United States as amicus curiae,

concede, as they must, the independence of the avenues

of relief respectively available under Title VII and the

older § 1981. See Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392

U. S. 409, 416-417 n. 20 (1968). Further, it has been

noted that the filing of a Title VII charge and resort to

Title VIPs administrative machinery are not prerequi

sites for the institution of a § 1981 action. Long v. Ford

Motor Co., 496 F. 2d 500, 503-504 (CA6 1974); Caldwell

v. National Brewing Co., 443 F. 2d 1044, 1046 (CA5

1971), cert, denied, 405 U. S. 916 (1972); Young v. In

ternational Tel. .& Tel. Co., 438 F. 2d 757, 761-763

(CA3 1971). Cf. Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works, 427

F. 2d 476, 487 (CA7), cert, denied, 400 U. S. 911 (1970).

We are satisfied, also, that Congress did not expect

that a § 1981 court action usually would be resorted to

only upon completion of Title VII procedures and the

Commission’s efforts to obtain voluntary compliance.

Conciliation and persuasion through the administrative

process, to be sure, often constitute a desirable approach

to settlement of disputes based on sensitive and emotional

charges of invidious employment discrimination. We

recognize, too, that the filing of a lawsuit might tend to

deter efforts at conciliation, that lack of success in the

legal action could weaken the Commission’s efforts to

induce voluntary compliance, and that a suit is privately

oriented and narrow, rather than broad, in application, as

successful conciliation tends to be. But these are the

natural effects of the choice Congress has made available

to the claimant by its conferring upon him independent

administrative and judicial remedies. The choice is a

valuable one. Under some circumstances, the admin

istrative route may be highly preferred over the litiga

tory; under others, the reverse may be true. We are

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

disinclined, in the face of congressional emphasis upon

the existence and independence of the two remedies, to

infer any positive preference for one over the other,

without a more definite expression in the legislation Con

gress has enacted, as, for example, a proscription of a

§ 1981 action while an EEOC claim is pending.

We generally conclude, therefore, that the remedies

available under Title VII and under § 1981, although

related, and although directed to most of the same ends,

are separate, distinct, and independent. With this base

established, we turn to the limitation issue.

IV

A. Since there is no specifically stated or otherwise

relevant federal statute of limitations for a cause of

action under § 1981, the controlling period would ordi

narily be the most appropriate one provided by state

law. See O’Sullivan v. Felix, 233 U. S. 318 (1914)

(Civil Rights Act of 1871); Auto Workers v. Hoosier

Corp., 383 U. S. 696, 701-704 (1966) (Labor Manage

ment Relations A ct); Cope v. Anderson, 331 U. S. 461

(1947) (National Bank Act); Chattanooga Foundry v.

Atlanta, 203 U. S. 390 (1906) (Sherman Act); Campbell

v. Haverhill, 155 U. S. 610 (1895) (Patent Act). For

purposes of this case, the one-year limitation period in

Tenn. Code § 28-304 clearly and specifically has appli

cation.7 See Warren v. Norman Realty Co., ----F. 2d

7 In the petition for certiorari it was argued that § 28-304 was

inapplicable to petitioner’s claim because that statute is limited to

claims for damages, whereas petitioner sought injunctive relief as

well as backpay. Our limited grant of certiorari foreclosed our con

sidering whether some other Tennessee statute, such as Tenn. Code

§28-309 (six years for an action on a contract) or §28-310 (10

years on an action not otherwise provided for), might be the appro

priate one. We also have no occasion to consider whether Tennes

see’s express application of the one-year limitation period to federal

---- (CA8 1975). The cause of action asserted by peti

tioner accrued, if at all, not later than June 20, 1967, the

date of his discharge. Therefore, in the absence of some

circumstance that suspended the running of the limita

tion period, petitioner’s cause of action under § 1981 was

time-barred after June 20, 1968, some two and one-half

years before petitioner filed his complaint.

B. Respondents argue that the only circumstances that

would suspend or toll the running of the limitation

period under § 28-304 are those expressly provided under

state law. See Tenn. Code §§ 28-106 to 28-115 and 28-

301. Petitioner concedes, at least implicitly, that no

tolling circumstance described in the State’s statutes was

present to toll the period for his § 1981 claim. He

argues, however, that state law should not be given so

broad a reach. He claims that, although the duration of

the limitation period is bottomed on state law, it is fed

eral law that governs other limitations aspects, such as

tolling, of a § 1981 cause of action. Without launching

into an exegesis on the nice distinctions that have been

drawn in applying state and federal law in this area,8

we think it suffices to say that petitioner has overstated

his case. Indeed, we may assume that he would argue

vigorously in favor of applying state law if any of the

Tennessee tolling provisions could be said to assist his

cause.9

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 9

civil rights actions is an impermissible discrimination against the

federal cause of action, see Republic Pictures Corp. v. Kappler, 151

F. 2d 543, 546-547 (CA8 1945), aff’d, 327 U. S. 757 (1946), or

whether the enactment of the limitation period after the cause of

action accrued, Tenn. Pub. Acts 1969, c. 28, did not touch the

pre-existing federal claim.

8 See generally Hill, State Procedural Law in Federal Nondiversity

Litigation, 69 Harv. L. Rev. 66 (1955).

9 At oral argument petitioner advanced just such a proposition

with respect to the applicability of Tennessee’s saving statute, Tenn.

10 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

Any period of limitation, including the one-year period

specified by § 28-304, is understood fully only in the

context of the various circumstances that suspend it from

running against a particular cause of action. Although

any statute of limitations is necessarily arbitrary, the

length of the period allowed for instituting suit in

evitably reflects a value judgment concerning the point

at which the interests in favor of protecting valid claims*

are outweighed by the interests in prohibiting the prose

cution of stale ones. In virtually all statutes of limita

tions the chronological length of the limitation period is

interrelated with provisions regarding tolling, revival,

and questions of application. In borrowing a state period

of limitation for application to a federal cause of action,

a federal court is relying on the State’s wisdom in setting

a limit, and exceptions thereto, on the prosecution of a

closely analogous claim.

There is nothing anomalous or novel about this. State

law has been followed in a variety of cases that raised

questions concerning the overtones and details of appli

cation of the state limitation period to the federal cause

of action. Auto Workers v. Hoosier Corp., 383 IT. S., at

706 (characterization of the cause of action); Cope v.

Anderson, 331 U. S., at 465-467 (place where cause of

action arose); Barney v. Oelrichs, 138 U. S. 529 (1891)

(absence from State as a tolling circumstance). Nor is

there anything peculiar to a federal civil rights action

that would justify special reluctance in applying state

law. Indeed, the express terms of 42 U. S. C. § 1988 10

suggest that the contrary is true.

Code § 28-106. Tr. of Oral Arg. 14. See also Petition for Cert.

21 n. 27.

10 Title 42, U. S. C. § 1988 provides:

“The jurisdiction in civil and criminal matters conferred on the

district courts by the provisions of this chapter and Title 18, for

the protection of all persons in the United States in their civil

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 11

C. Although state law is our primary guide in this

area, it is not, to be sure, our exclusive guide. As the

Court noted in Auto Workers v. Hoosier Corp., 383 U. S.,

at 706-707, considerations of state law may be displaced

where their application would be inconsistent with the

federal policy underlying the cause of action under

consideration.

Petitioner argues that a failure to toll the limitation

period in this case will conflict seriously with the broad

remedial and humane purposes of Title YU. Specifi

cally, he urges that Title VII embodies a strong federal

policy in support of conciliation and voluntary compli

ance as a means of achieving the statutory mandate of

equal employment opportunity. He suggests that failure

to toll the statute on a § 1981 claim during the pendency

of an administrative complaint in the EEOC would force

a plaintiff into premature and expensive litigation that

would destroy all chances for administrative conciliation

and voluntary compliance.

We have noted this possibility above and, indeed, it

is conceivable, and perhaps almost to be expected, that

failure to toll will have the effect of pressing a civil

rights complainant who values his § 1981 claim into

court before the EEOC has completed its administrative

rights, and for their vindication, shall be exercised and enforced in

conformity with the laws of the United States, so far as such laws

are suitable to carry the same into effect; but in all cases where

they are not adapted to the object, or are deficient in the provisions

necessary to furnish suitable remedies and. punish offenses against

law, the common law, as modified and changed by the constitution

and statutes of the State wherein the court having jurisdiction of

such civil or criminal cause is held, so far as the same is not in

consistent with the Constitution and laws of the United States, shall

be extended to and govern the said courts in the trial and disposi

tion of the cause, and, if it is of a criminal nature, in the infliction

of punishment on the party found guilty.”

12 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

proceeding.11 One answer to this, although perhaps not

a highly satisfactory one, is that the plaintiff in his

§ 1981 suit may ask the court to stay proceedings until

the administrative efforts at conciliation and voluntary

compliance have been completed. But the fundamental

answer to petitioner’s argument lies in the fact—pre

sumably a happy one for the civil rights claimant—that

Congress clearly has retained § 1981 as a remedy against

private employment discrimination separate from and

independent of the more elaborate and time consuming

procedures of Title VII. Petitioner freely concedes that

he could have filed his § 1981 action at any time after

his cause of action accrued; in fact, we understand him

to claim an unfettered right so to do. Thus, in a very

real sense, petitioner has slept on his § 1981 rights. The

fact that his slumber may have been induced by faith

in the adequacy of his Title VII remedy is of little rele

vance inasmuch as the two remedies are truly independ

ent. Moreover, since petitioner’s Title VII court action

now also appears to be time-barred because of the pecu

liar procedural history of this case, petitioner, in effect,

would have us extend the § 1981 cause of action well

beyond the life of even his Title VII cause of action.

We find no policy reason that excuses petitioner’s failure

to take the minimal steps necessary to preserve each

claim independently.

y

Petitioner cites American Pipe & Construction Co. v.

Utah, 414 U. S. 538 (1974), and Burnett v. New York

Central R. Co., 380 U. S. 424 (1965), in support of his 11

11 We are not unmindful of the significant delays that have at

tended administrative proceedings in the EEOC. See, e. g., Chrom-

craft Corp. v. EEOC, 465 F. 2d 745 (CA5 1972); Equal Employ

ment Opportunity Comm. v. E. I. duPont deNemours & Co., 373

F. Supp. 1321, 1329 (Del. 1974).

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 13

position. Neither case is helpful. The respective periods

of limitation in those cases were derived directly from

federal statutes rather than by reference to state law.

Moreover, in each case there was a substantial body of

relevant federal procedural law to guide the decision to

toll the limitation period, and significant underlying fed

eral policy that would have conflicted with a decision

not to suspend the running of the statute.12 In the

present case there is no relevant body of federal proce

dural law to guide our decision, and there is no conflict

ing federal policy to protect.13 Finally, and perhaps

most importantly, the tolling effect given to the timely

prior filings in American Pipe and in Burnett depended

heavily on the fact that those filings involved exactly

12 In Burnett, the Court considered the effect of a prior filing of

an action under the Federal Employers’ Liability Act in state court

on the applicable three-year FELA period of limitation. The action

had been dismissed because under state law the venue was improper.

In view of the express federal policy liberally allowing transfer of

improperly venued cases, see 28 U. S. C. § 1406 (a), and the de

sirability of uniformity in the enforcement of FELA claims, the

Court concluded that the prior filing tolled the statute. In Ameri

can Pipe we considered the effect that a timely filed civil antitrust

purported class action should have on the applicable four-year

federal period of limitation. The District Court found the suit an

inappropriate one for class action status. In the light of the history

of Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 23 and the purposes of litigative efficiency

served by class actions, we concluded that the prior filing had a

tolling effect.

13 We note expressly how little is at stake here. We are not really

concerned with the broad question whether these respondents can

be compelled to conform their practices to the nationally mandated

policy of equal employment opportunity. If the respondents, or

any of them, presently are actually engaged in such conduct, there

necessarily will be claimants who are in a position now either to

file a charge under Title VII or to sue under § 1981. The question

in this case is only whether this particular petitioner has waited so

long that he has forfeited his right to assert his § 1981 claim in

federal court.

14 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

the same cause of action subsequently asserted. This

factor was more than a mere abstract or theoretical con

sideration because the prior filing in each case necessarily

operated to avoid the evil against which the statute of

limitations was designed to protect.14

The judgment of the Court of Appeals is affirmed.

I t is so ordered.

14 Petitioner argues that the timely filing of a charge with the

EEOC has the effect of placing the charged employer on notice that

a claim of discrimination is being asserted. Thus, petitioner argues,

the employer has the opportunity to protect itself against the loss of

evidence, the disappearance and fading memories of witnesses, and

the unfair surprise that could result from a sudden revival of a claim

that long has been allowed to slumber. See Telegraphers v. Ry.

Express Agency, 321 U. S. 342, 348-349 (1944).

Even if we were to ignore the substantial span of time that could

result from tacking the § 1981 limitation period to the frequently

protracted period of EEOC consideration,. we are not a t all certain

that a Title VII charge affords the charged party the protection

that petitioner suggests. See, e. g., Tipler v. E. I. duPont deNe-

mours & Co., 443 F. 2d 125, 131 (CA6 1971). Only where there

is complete identity of the causes of action will the protections sug

gested by petitioner necessarily exist and will the courts have an

opportunity to assess the influence of the policy of repose inherent

in a limitation period. See generally Developments in the Law-—

Statutes of Limitation, 63 Harv. L. Rev. 1177, 1185-1186 (1950).

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 73-1543

Willie Johnson, Jr.,

Petitioner,

v.

Railway Express Agency,

Inc., et al.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[May 19, 1975]

M r. J ustice M arshall, with whom M r. J ustice

D ouglas and M r . J ustice B ren n a n join, concurring in

part and dissenting in part.

In recognizing that Congress intended to supply ag

grieved employees with independent but related avenues

of relief under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

and § 1981 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Court

emphasizes the importance of a full arsenal of weapons

to combat unlawful employment discrimination in the

private as well as the public sector. The majority stands

on firm ground in recognizing that both remedies are

available to victims of discriminatory practices. Accord

ingly, I concur in Parts I - III of the Court’s opinion.

But, the Court stumbles in its analysis of the relation

between the two statutes on the tolling question. The

majority concludes that the filing of a Title VII charge

with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(EEOC) does not toll the applicable statute of limita

tions. It relies exclusively on state law for the period

and effect of the limitation and discounts the importance

of the federal policies of conciliation and avoidance of

unnecessary litigation in this area. The majority recog

nizes these policies but concludes that tolling the statute

of limitations for a § 1981 suit during the pendency of

Title VII proceedings is not an appropriate means of

furthering them. I disagree. The congressional pur

pose of discouraging premature judicial intervention and

the absence of any real risk of reviving stale claims sug

gest the propriety of tolling here. On balance, I view

the failure to apply the tolling principle as undermining

the foundation of Title VII and frustrating the congres

sional policy of providing alternative remedies. I must,

therefore, dissent from Parts IV and V of the opinion.

The Court sets out the circumstances that suspend

a statute of limitations without close examination of the

statute’s equitable underpinnings. According to the ma

jority, the federal court is deprived of authority to toll

the state statute because it borrows both “the State’s

wisdom in setting a limit, [as well as] exceptions thereto,”

ante, at 10, and offers no special reason for reluctance to

apply the “overtones” of the period to a federal civil rights

action. As a general practice, where Congress has created

a federal right without prescribing a period for enforce

ment, the federal courts uniformly borrow the most anal

ogous state statute of limitations. The applicable period

of limitations is derived from that which the State would

apply if the action had been brought in a state court.

See, e. g., United Automobile Workers v. Hoosier Cardi

nal Corp., 383 U. S. 696 (1966); Holmberg v. Armbrecht,

327 U. S. 392 (1946). O’Sullivan v. Felix, 233 U. S. 318

(1914). See also American Pipe Construction Co. v. Utah,

414 U. S. 538, 556 n. 27 (1974). For the purposes of this

case the § 1981 action is governed by the District Court’s

application of the one-year Tennessee provision for

“actions . . . brought under the federal civil rights stat

utes.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 28-304. See ante, at n. 7.

Congress’ failure to include a built-in limitations period

in § 1981 does not automatically warrant “an imprimatur

on state law” and sanction the borrowing of both the

effect as well as the duration from state law. United

2 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 3

Auto Workers v. Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383 U. S., at

709 (W h it e , J., dissenting); Holmberg v. Armbrecht,

327 U. S., at 394-395; Board of County Comm’rs v.

United States, 308 U. S. 343 (1939). It is well settled

that when federal courts sit to enforce federal rights,

they have an obligation to apply federal equity principles:

“When Congress leaves to the federal courts the

formulation of remedial details, it can hardly expect

them to break with historic principles of equity

in the enforcement of federally-created equitable

rights.” Holmberg v. Armbrecht, 327 U. S., at 395.

See also Moviecolor Ltd. v. Eastman Kodak Co., 288

F. 2d 80 (CA2), cert, denied, 368 U. S. 821 (1961).

The effect to be given the borrowed statute is thus

a matter of judicial implication. Simply stated, we

must determine whether the national policy considerations

favoring the continued availability of the § 1981 cause of

action outweigh the interests protected by the State’s stat

ute of limitations. See United Auto Workers v. Hoosier

Cardinal Corp., 383 U. S., at 708; Holmberg v. Armbrecht,

327 U. S., at 395.

I

Title VII and now § 1981 both express the federal

policy against discriminatory employment practices. Em

porium Capwell Co. v. WACO, 420 U. S .----, •— (1975);

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U. S. 36, 44

(1974); McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U. S.

792, 800 (1973); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U. S.

424, 429-430 (1971). As we have recently observed,

“legislative enactments in this area have long evinced a

general intent to accord parallel or overlapping remedies

against discrimination.” Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co., 415 U. S., at 47. It is this general legislative intent

that must guide us in determining whether congressional

4 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

purpose with respect to a particular statute is effectuated

by tolling the statute of limitations.

A full exposition of the statutory origins of § 1981

with respect to prohibition against private acts of dis

crimination is set out in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co.,

392 U. S. 409 (1968). In construing § 1982, a sister

provision to § 1981, we concluded that Congress intended

to prevent private discriminatory deprivations of all the

rights enumerated in Section I of the 1866 Act, including

the right to contract. 392 U. S., at 426. The Court’s

recognition of a proscription in § 1981 against private

acts of employment discrimination, ante, at 6, reaffirms

that the early civil rights acts reflect congressional intent

to “speak to all deprivations . . . whatever their source.”

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U. S. 88 (1971); Sullivan v.

Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U. S. 229 (1969).

The legislative history of Title VII and its 1972

amendments demonstrates that Congress intended to pro

vide a coordinated but comprehensive set of remedies

against employment discrimination. The short statute of

limitations and the procedural prerequisites to Title VII

actions emphasized the need to preserve the remedy of

a suit under the 1866 legislation, which did not suffer

from the same procedural restrictions as the latter enact

ment. See H. R. Rep. No. 238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess.,

19 (1971); S. Rep. No. 415, 92d Cong., 1st Sess., 24

(1971). See also 118 Cong. Rec. 3370. Congressional

sentiment was that “by strengthening the administrative

remedy [it] should not also eliminate preexisting rights

which the Constitution and the Congress had accorded to

aggrieved employees.” Id., at 3371. While encourage

ment of private settlement to avoid unnecessary litiga

tion under Title VII and the preservation of an inde

pendent § 1981 action may appear somewhat at odds,

the two themes are reconciled in the context of their joint

remedial purpose: devising a flexible network of remedies

to guarantee equal employment opportunities. See, e. g.,

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal, 498 F. 2d 641, 650 (CA5

1974); Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Corp., 437

F. 2d 1011, 1017 (CA5 1971); Macklin v. Spector Freight

Systems, In c .,---- U. S. App. D. C. — ---- 478 F. 2d

979, 994-995 (1973). See also Culpepper v. Reynolds

Metal Co., 421 F. 2d 888 (CA5 1970).

In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, supra, we examined

the relationship between compulsory arbitration and liti

gation under Title VII, a relationship analogous to that

between the EEOC factfinding and conciliation process

and litigation under § 1981, and accommodated both ave

nues of redress. The reasoning leading to that result is

equally compelling here. Forced compliance with a short

statute of limitations during the pendency of a charge be

fore the EEOC would discourage and/or frustrate recourse

to the congressionally favored policy of conciliation,

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U. S., at 44, and “the

possibility of voluntary compliance or settlement of Title

VII claims would thus be reduced, and the result could

well be more litigation, not less. Id., at 59. Cf. Ameri

can Pipe Ac Const. Co. v. Utah, 414 U. S. 538, 555-556

(1974).

Congressional effort, with the 1972 amendments, to

strengthen the administrative remedy by increasing

EEOC’s ability to conciliate complaints is frustrated by

the majority’s requirement that an employee file the

§ 1981 action prior to the conclusion of the Title VII

conciliation efforts in order to avoid the bar of the

statute of limitations.1 Legislative pains to avoid un

necessary and costly litigation by making the informal,

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 5

1 Loss of the § 1981 cause of action would deprive the aggrieved

employee of the opportunity to recover punitive damages and more

ample backpay.

6 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

investigatory and conciliatory offices of EEOC readily

available to victims of unlawful discrimination cannot

be squared with the formal mechanistic requirement of

early filing for the technical purpose of tolling a limita

tions statute. In sum the federal policies weigh strongly

in favor of tolling.

Examination of the purposes served by the statute of

limitations indicates that they would not be frustrated

by adoption of the tolling rule. Statutes of limitations

are designed to insure fairness to defendants by prevent

ing the revival of stale claims in which the defense is

hampered by lost evidence, faded memories and dis

appearing witnesses, and to avoid unfair surprise. None

of these factors exist here.

Respondents were informed of the petitioner’s greiv-

ances through the complaint filed with the Commission

and conciliation negotiations. The charge filed with the

EEOC and the § 1981 claim arise out of the same factual

circumstances. The petitioner in this case diligently

pursued the informal procedures before the Commission

and adhered to the congressional preference for concilia

tion prior to litigation. Now, when Johnson asserts his

right to proceed with litigation under § 1981 after his

good faith, albeit unnecessary, compliance with Title VII

procedures, the majority interposes the bar of the Ten

nessee statute of limitations which clearly was not de

signed to include such cases.2

2 Under the Court’s no-tolling principle petitioner’s discharge on

June 20, 1967, activated the statute which subsequently ran on

June 20, 1968—two years prior to his receipt of the right to sue

letter! The majority suggests that even if the statute were tolled

during the consideration of the EEOC charge and the initial court

proceedings, petitioner’s Title VII action may be time-barred be

cause of the unusual procedural history of the case, requiring the

Court to extend his § 1981 claim beyond that arising out of Title

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

In my judgment, following the antitolling position of

the Court to its logical conclusion produces an inequi

table result. Aggrieved employees will be forced into

simultaneously prosecuting premature § 1981 actions in

the federal courts. In essence, the litigant who first ex

plores conciliation prior to resort to litigation must file a

duplicative claim in the District Court on which the

court will either take no action until the Title VII pro

ceedings are concluded or proceed in frustration of the

EEOC attempts to conciliate. No federal policy con

siderations warrant this waste of judicial time and dero

gation of the conciliation process.

Adoption of the tolling principle, however, protects

the federal interest in both preserving multiple remedies

for employment discrimination and in the proper func

tion of the limitations statute. As a normal conse

quence tolling works to suspend the operation of a

statute of limitations during the pendency of an event

or condition. See American Pipe <& Construction Co.

v. Utah, 414 U. S., at 560-561; Burnett v. N. Y. Cen

tral R. Co., 380 U. S. 424, 427 (1965). In American

Pipe we held that the initiation of a timely class action

tolled the running of the limitation period as to indi

vidual members of the class, enabling them to institute

separate actions after the District Court found class action

an inappropriate mechanism for the litigation. In similar

VII. But our limited grant of certiorari forecloses consideration of

the timeliness of the Title VII claim.

In any event this case reflects no departure from the normal rule of

tolling. Consistent with the common understanding that tolling en

tails a suspension rather than an extension of a period of limitations,

petitioner is allowed whatever time remains under the applicable

statute, as well as the benefit of any state savings statute. Under

Tenn. Code Ann. § 28-106 an action dismissed without prejudice may

be reinstituted within a year of dismissal. The filing here falls well

within that time frame.

8 JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY

manner the Burnett court viewed the initiation of a

timely Federal Employers’ Liability Act suit in state

court as tolling the statute of limitations for the later

filing of a federal action following dismissal of the state

proceeding for improper venue. The Court’s analysis in

both cases rested on the conclusion that each plaintiff

had by his prior action given the defendant timely notice

in a manner that “fulfilled policies of repose and cer

tainty inherent in the limitations provisions and tolled

the running of the period.” American Pipe & Construc

tion Co. v. Utah, supra, 414 U. S., at 558.

Although the length of the limitation in these cases

was fixed by federal statute, the tolling rationale is

equally adaptable to protect subsequent litigation when

the duration period is established by state statute. The

federal policy in favor of continuing availability of mul

tiple remedies for persons subject to employment dis

crimination is inconsistent with the majority’s decision

not to suspend the operation of the statute. As long as

the claim arising under § 1981 is essentially limited

to the Title VII claim, staleness' and unfair surprise dis

appear as justification for applying the statute.3 Addi

tionally, the difference in statutory origin for the right

asserted under the EEOC charge and the susequent

§ 1981 suit is of no consequence since the claims are

essentially equivalent in substance. Cf. Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver, supra. Since the EEOC charge gives

notice that petitioner also has a grievance under § 1981,

that filing, like the initial litigation in Burnett and

American Pipe, satisfied the equitable policies under

3 Where there are differences between the § 1981 claim and the

Title VII complaint, the district courts could easily limit the tolling

to those portions of the § 1981 claim that overlapped with the Title

VII allegations. Cf. EEOC v. Louisville & Nashville R. Co., 505

F. 2d 610, 617 (CA5 1974); Sanchez v. Standard Brands, 431 F

2d 455, 466 (CA5 1970).

lying the limitation provision. American Pipe <ft Con

struction Co. v. Utah, 414 U. S., at 558.

Neither the legislative history of these acts nor the

avowed purposes of statutes of limitations foreclose good

faith resort to the administrative procedures of EEOC.

Adoption of the tolling theory avoids the draconian

choice of losing the benefits of conciliation or giving up

the right to sue, yet preserves the independent nature

of the § 1981 action. Accordingly, I would reverse the

court below on this point.

JOHNSON v. RAILWAY EXPRESS AGENCY 9