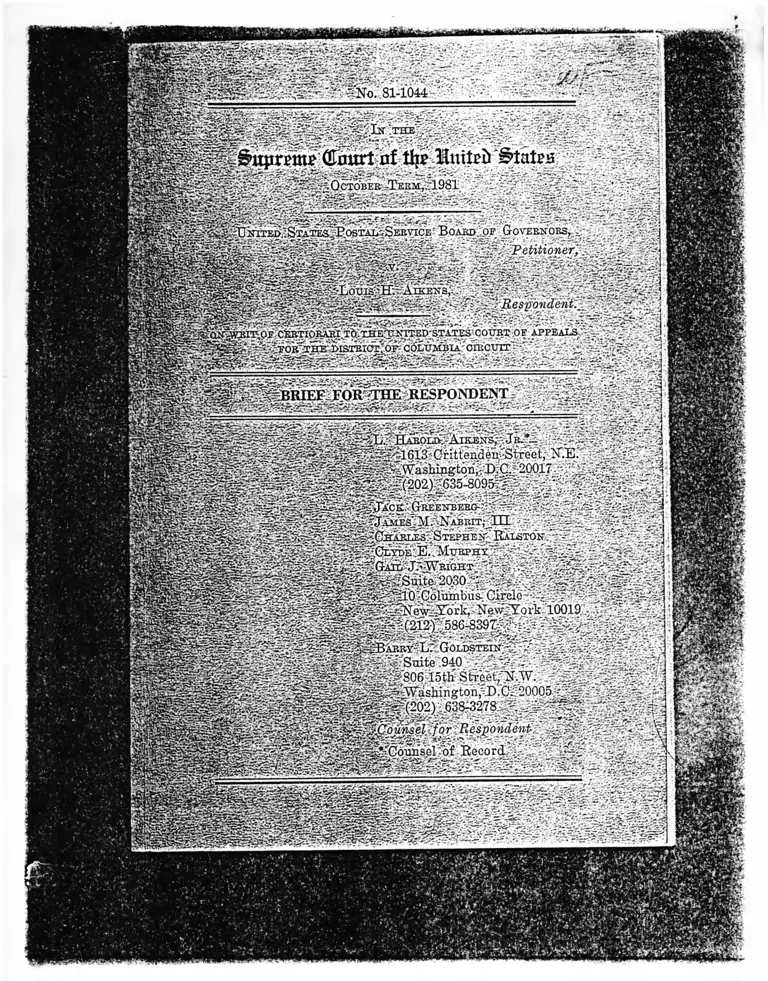

United States Postal Service Board of Governors v. Aikens Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1981

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States Postal Service Board of Governors v. Aikens Brief for Respondent, 1981. 68412d33-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/226ab4a2-4b4b-4112-805e-14e8e6094345/united-states-postal-service-board-of-governors-v-aikens-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

* f c i l

question presented

Was the court of appeals' holding that

respondent, plaintiff below, had made out a

Hlma ggcie case of discrimination, consis

tent with decisions of this Court, with the

legislative history of Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act, as amended, and with the

polices and purpose underlying Title VII?

- 1 -

Table of Contents

Opinion Below ..................

Jurisdiction ...................

Statute Involved ...............

Statement of the Case ..........

A. Background .............

B. Selection procedures for

details to higher level

positions .............

C. The treatment of whitesand blacks ............

D. Comparison of Aikens

and his white col

leagues ...............

E. Experience as a factor

in selection for higher level jobs ............

F. Anecdotal evidence re

marks that betray prejudice or sterotyped thinking ..............

Nummary of Argument .......‘....

ARGUMENT; .....................

I. Introduction .........

/- ii -

Page

1

2

2

3

3

20

27

32

34

36

36

W -

m v Page

II. The Legislative History of

the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 Supports the

Continuing Vitality of McDonnell Douglas and the Decision ofthe Court Below ...........

III. the Prima Facie Case

Rule of McDonnell Douglas Is

A Reasonable and Effective

Approach for Individual Title VII Cases ...........

IV. The Decision Below Is

Fully Consistent With

McDonnell Douglas v. Green

Conclusion .......

Statutory Appendix

- Ill -

55

70

and Its Progeny ........ 88

The Prima Facie Case . . . 88

B_̂ Addition Facts Demon-

stirating Discrimina-tion .............. 92

Petitioner's Arguments

Are Inconsistent With

McDonnell Douglas and Burdine ............. 95

1 10

Table of Authorities 1̂ '

Cases Page

Alexander v. Louisiana, 405 U.S.

, 625 (1972) ................ 75

Barrett v. U.S. Civil Service

Commission, 69 F.R.D. 544

(D.D.C. 1975) ............. 45̂

Blake V. Califano, 626 F.2d 891

(D.C. 1980) ............... 47

Board of Trustees of Keene State

College v. Sweeney, 439 U.S.

24 (1978) ................ 38,79,109

Brown v. G.S.A., 425

U.S. 820 (1976) ............ 56,64

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482

(1977) .................... 73I

Chandler v. Roudebush,

425 U.S. 840 (1976 ) ....... 45,51

Chisholm v. United States Postal

Service, 516 F. Supp. 810

(M.D.N.C. 1980), aff'd,655 F.2d 482 (4th Cir.

1981) ................... 65, 92,93,96

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S.

55 (1980) ................. 69

Clark V. Alexander, 489 F. Supp.

1236 (D.D.C. 1980) . . ."r. . . . . 64

Page

Clark V. Chasen, 619 F.2d 1330 (9th

Cir. 1980 ) ............... 64

Connecticut v. Teal, ___U.S. ___,

U.S.L.W. 4716 (June 4,1982) ..................... 99

Copeland v. Marshall, 641 F.2d 880

D.C. Cir. 1980) ............. 4 6

Davis V. Califano, 613 F.2d 957

(D.C. Cir. 1979) ......... 96,99, 108

Davis V. Weidner, 596 F.2d 726 (7th

Cir. 1979) ................ 81,82,85

Day V. Mathews, 530 F.2d 1083 (D.C.

Cir. 1976) ................ 45

deLesstine v. Ft. Wayne State

Hosp., 29 FEP Cases 195(7th C ir. 1981) ........... 84

- Eastland v. T.V.A., 553 F.2d 364

(5th Cir. 1977) ........... 46

Evans v. Baldridge, 27 FEP Cases,

1479 (D.D.C. 1982 ) ........ 83

Flowers V. Crouch-Walker Corp., 552

F..2d 1277 (7th Cir. 1977) ... 78,81

Franklin v. Trokel Mfg. Co.,

501 F.2d 1013 (6th Cir.

1974) ..................... 78

Fullilove V. Klutznick, 448 U.S.

448 (1980) ................. 67

- V -

- IV -

Page

I- Page

Furnco Construction Corp. v.

Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978) ....................

Gates V. Georgia-Pacific Corp., 492

F.2d 292 (9th Cir. 1974) ___

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S.

424 (1971) ................

Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d 108

(D.C. Cir. 1975) ..........

Harrell v. Northern Electric Co.,

672 F.2d 444 (5th Cir.

1982) .....................

Harrison v. Lewis (D.D.C., Civ.Act. 79-1816, June 17,

1982) .....................

Houseton v. Nimmo, 670 F.2d 1375

(9th Cir. 1982) ...........

Johnson v. Bunny Bread Co., 646

F.2d 1250 (8th Cir.

1981) .....................

Kaufman v. Sidereal Corp., 677

F.2d 767 (9th Cir. 1982) ...

Kenyatta v. Bookey Packing Co.,

649 F.2d 552 (8th Cir.1981) .....................

King V. New Hampshire Dept, of

Resources, 562 F.2d 80-(lst

Cir. 1977) ......< ........

38,79,99

79

56

51

98,108

64

47

84

84

84

; \

I '

' N

78,80

Kunda v. Muhlenberg College,

621 F.2d 532 (3rd Cir.1980) .....................

Loeb V. Textron, Inc., 600 F.2d

1003 (1st Cir. 1979) ......

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792 (1973) .......

McKenzie v. McCormick^ 425 F. Supp.

137 (D.D.C. 1977) .........

Meyer v. Brown and Root Constr.

Co., 661 F.2d 369 (5th

Cir. 1981) ................

Mitchell V. M.D. Anderson Hosp.,

29 FEP Cases 263 (5th Cir. 1982) .....................

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535(1974) ....................

New York Gaslight Co. v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54 (1980) ............

Parker v. Califano, 561 F.2d 320

(D.C. Cir. 1977) ..........

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, 673

F.2d 798 (5th Cir. 1982 ) ...

Peters v. Jefferson Chemical Co.,

516 F.2d 447 (5th Cir.

1975) .....................

Pointer v. Sampson, 62 F.R.D. 689

(D.D.C. 1974) ............

107

80,81,87

passim

64

83

84

64

45

49

108

81,82,83

44

- VI - - Vll

Page

nr.sv-,; Page

Powell V. Syracuse University, 580F.2d 1150 (2nd Cir. 1978) .. 78,85

Rodriguez v. Taylor, 569 F.2d 1231

(3rd Cir. 1977) ............ 84

Sabol V. Snyder, 525 F.2d 1009

(10th Cir. 1975) .......... 79

Saunders v. Claytor, 629 F.2d 596

(9th Cir. 1980) ........... 47

Segar v. Civiletti, 508 F. Supp.

609 (D.D.C. 1981) ......... 64

Smith V. Califano, 446 F. Supp. 530

(D.D.C. 1978) ............. 45

Taylor v. Louisiana, 419 U.S. 522

(1975) .................... 73

Texas Department of Community

Affairs V. Burdine, 450 U.S.

248 (1981) ................ passim

Thompson v. Sawyer, 28 F.E.P. Cases

1614 (D.C. Cir. 1982 ) ..... 64

Trout V. Hidalgo, 517 F. Supp. 873

(D.D.C. 1981) ............. 64

Turner v. Fouche, 396 U.S. 346

(1970) ............... 73

Turner v. Texas Instruments, Inc., 555 F.2d 1251 (5th Cir.

1977) .....................

Valentino v. United States Postal

Service, 674 F.2d 56 (D.C.Cir. 1982) ................

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ....................

Wells V. Harris, 1 Merit Systems

Protection Board Decisions 199 (1979) ................

Williams v. T.V.A., 552 F.2d 691

,(6th Cir. 1977) ...........

Womack v. Munson, 619 F.2d 1292(8th Cir. 1980) ...........

Wright v. National Archives Records

Service, 609 F.2d 702 (4th Cir. 1979) ......................

Statutes

Civil’Service Reform Act of 1978;

P..L. 95-454; 92 Stat. 1111 ...

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Section 717 ..........

80

65

72

68

48

81,82

80,83

41,50

passim

- IX -

- Vlll -

5 U.S.C. §§ 1206 ...............

5 U.S.C. §§ 2302(b)(1)(A) ......

5 U.S.C. §§ 2302(d) ............

5 U.S.C. § 4302(b)(1) ..........

5 U.S.C. §§ 4313(5) ............

5 U.S.C. §§ 7121(d) ............

5 U.S.C. §§ 7201 ...............

5 U.S.C. §§ 7702 ...............

5 U.S.C. § 7702(e)(1) ...........

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16 ............

P.L. 97-205; 96 Stat. 135 .......

Other Authorities

Bartholet, Application of Title VII

to Jobs in High Places, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 947 (1982) ..........

C.C.H. Employment Practices

Guide II 5046 (1977) . .’.....

C.C.H. Employment Practices

Guide II 5327 (1975) .......

Executive Order 11478

Federal Personnel Manual, Chap.300.......................

Page

65

65

66

66

66

65

66

65

50

passim

69

•If;, ̂

107

46

44

56

93

Page

Hearings before the General Subcom

mittee on Labor of the Committee on Education and Labor - House

of Representatives, Washington,D.C., December 2, 1969 ... S2

Hearings before the Labor Subcom

mittee of the House Committee on

Education and Labor, March 3,1971 ...................... 63

Hearings Before the Subcommittee on

Labor of the Senate Committee

on Labor and Public Welfare,

Oct. 4, 1971 .............. 43,63

Hill, "The AFL-CIO and the Black

Worker: Twenty-five Years After the Merger", 10

Journal of Intergroup Relations 5 ( 1982) ............ 47

H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92d Cong., 1st

Sess. 1971) ............... 57,60,61

117 Cong. Rec. 32 (1971 ) ........ 61

1978 U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News,

P. 9795 ................... 41

President's Reorganization Plan No.

1' 1978 ................. 41,65

Ralston, "The Federal.Government as

Employer: Problems and Issues

in Enforcing the Anti-Dis

crimination Laws," 10 Ga.L. Rev. 717 (1976) ......... 51

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92d Cong., 1st

Sess. 1971) ............... 54,56,57,

58,60,61

I

No. 81-1044

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1981

UNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE BOARD OF GOVERNORS,

Petitioner,

V.

LOUIS H. AIKENS,

On Writ of Certiorari to The United

States Court of Appeals For The

District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the district court

(Pet. App. 49a-59a) is not reported. The

initial opinion of the court of appeals

(Pet. App. 17a-40a) is reported at 642 F.2d

W ■

- 2 -

514. The opinion of the court of appeals

on petitions for rehearing (Pet. App.

43a-48a) is not reported. The order of

this Court vacating the initial judgment of

the court of appeals and remanding for

reconsideration (Pet. App. 10a-14a) is

reported at 453 U.S. 902. The opinion of

the court of appeals on remand (Pet. App.

2a-9a) is reported at 665 F.2d 1057.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals

(Pet. App. la) was entered on September 8,

1981. The petition for a writ of certi

orari was filed on December 4, 1981, and

granted on March 22, 1 982 (J.A. 12). The

jurisdiction of this Court rests on 28

U.S.C. 1254(1).

STATUTE INVOr.VKn

This action involves 42 U.S.C. §2000e-

16, the full text of which is set out in

the appendix to this brief.

- 3 -

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Respondent generally agrees with

petitioners' statement of the procedural

history of this case. In order to put the

legal questions raised by this case in

their proper context, however, a full

statement of the facts herein is necessary.

A. Bac)cqround

Respondent, Louis H. AiJcens, is a

Black man who began his employment with the

Post Office in Washington, D.C. in 1937.

He was promoted to his first supervisory

position in 1952; until 1960, he held

variogs jobs at the level of foreman. From

1960 to 1966, he received six promotions

that raised him from the foreman level

to the level of Assistant Director, Opera

tions Division for Transit Mails. He was

the first Black to be at that level; until

1973, only whites were above him. Between

- 4 -

1966 and 1 973, there were four positions

in the Washington, D.C. Post Office that

were ranked above PFS-15, During that

period, several white employees, all with

less seniority and experience than Aikens,

were promoted and/or detailed above him.

After the Job Evaluation Program (JEP)

in 1 973 ,“^ Aikens' job was rated at

grade PES-20; however, following the

implementation of the Job Evaluation

Program, several additional positions were

rated above Aikens' job and several junior

white employees received details or promo

tions above Aikens. In 1974, Aikens was

upgraded twice, once by virtue of a

2/ The Postal Service's Job Evaluation Program resulted in a revision of the

agency's grade structureWhereas before 1973 the grades ranged from 7 to 18,

afterwards they ranged from 15 to 29 in the

professional and supervisory positions

in the Washington, D.C., post office.

i m

M.r-i-1 Vs ■

- 5 -

promotion and once pursuant to a "detail"

(temporary assignment). Between 1966 and

1974, however, Aikens was neither detailed

nor promoted above his Assistant Director

position. His failure to be promoted or

detailed during this latter period formed

the basis of this Title VII suit. (App. E,

18a-19a).-/

Aikens filed an Equal Employment

Opportunity complaint with the Postal

Service on January 4, 1974, alleging, inter

alj^, that the Postal Service's failure to

promote and/or detail him to higher level

positions during the entire eight year

period, from 1966 until 1974, constituted

racial discrimination of a continuing

nature. (]M. , 19a, 19a, n.1.) However,

because of the time limitations in the EEO

2/ "App. E" refers to the appendix filed in the court of appeals below.

- 6 -

3/regulations, administrative and judicial

review was focused only on Aikens' failure

to be promoted to four positions for which

promotions or details had occurred within

thirty days of the complaint. The four

positions in question were Mail Processing

Officer; Acting Mail Processing Representa

tive; Director, Operations Division; and

Customer Services Representative. (id.

19a-20a.)

B. Selection procedures for details to

higher level positions

The procedure for supervisory promo-

3/ 5 C.F.R. §713-214 (1974) (now, 29

C.F.R. §1613.214) provided that only

matters occuring within 30 days of the

time an EEO Counselor was contacted would

be considered as part of the EEO complaint.

Matters outside that time could, however,

be considered as background. Evidence

concerning earlier matters was introduced at trial on that limated basis. The

correctness of the .lower courts' holding

that the judicial complaint should be limited to the four latest positions is not at issue here.

I

m;: - 7 -

tions required that the employee state on a

Postal Service form 1717 any job in the

Washington, D.C. Post Office for which

4/he wanted to be considered (Tr. 167).~

The plaintiff had form 1717s on file for

all jobs above his position of Assistant

Director, Operations Division, and he was

interested in being promoted or detailed to

any position above his level 15 prior to

JEP, and to any job above level 22 subse

quent to JEP in March, 1973 (Tr., 67, 86,

90, 91, 132).

The Washington, D.C. Post Office did

not post or solicit interested personnel to

I

fill details; individuals were selectedt

by higher level supervisors (Stip. 32;

J.A.10) 5/ The administrative procedure

4/ 'Tr" refers to the trial transcript.

5/ "Stip" refers to the stipulation of

facts entered into evidence as plaintiff's

Exhibit 4 (Joint Appendix, 6-11)

- 8 -

to assign a management official to a detail

involved only the preparation of POD Form

1723, "Assignment Order", signed by an

official with authority over the vacant

position; the normal procedure was to

detail an employee for period not to exceed

89 days, but the detail could be extended

by another Form 1723 (Stip. 18; J.A. 8).

Details were to be renewed only one time

after the initial 89 day period, but the

Postal Service had people who stayed on

detail for years (Tr. 69, 108).

The managment officials responsible

for selecting employees to be promoted

and/or detailed into positions higher than

that which the plaintiff held from 1966

until 1974 were the Postmaster (or Officer

In Charge) and the District Postal Manager.

During the relevant ̂ ime frame, these

positions were held by Carlton Beall and

- 9 -

Ellsworth Rapee, both of whom were white.

Details were made either by Beall or by

Rapee with the concurrence of Beall. (Tr.

38, 216-217, 241, 314) 6/

C • The Treatment of Whites and Blacks.

It had long been a practice of the

officials of the Washington, D.C. Post

Office to select white employees for

promotion or detail to higher level posi

tions, even though they were not more quali

fied than Black employees. While there

had been an improvement in the makeup of

the supervisory workforce, especially in

I

the period between the filing of the

complaint in 1974 and the trial in 1979,

The position of District Postal

Manager was superior to that of Postmaster.

Beall held the position of postmaster until

1971, when he became District manager.

Rapee then was acting postmaster until the

selection of a black male into the position on a permanent basis in early 1974 after

respondent filed his EEO complaint.

^ - 10 -

the statistics ^ of February, 1974, showed

that the percentage of white employees

occupying higher level positions was much

greater than the percentage of white

employees in the employee complement

of the Washington, D.C. Post Office. Thus,

when the complaint herein was filed, less

than 14% of employees were white.

Nevertheless, more than 48% of the super~

visors (including the postmaster) were

white. (Stip. 3-4; J.A. 6.)-'' one of the

7/ As of February 7, 1974, the employee

complement of the Washington, D.C. Post

Office totaled 8,634 employees, 7,403

of whom, or 85.7%, where of a minority

group background (Stip. 3). As of the above

date, 84.3% of Category I employees

(covered by the 1973 Natdonal Agreement)

were of a minority group background; 64.9%

of Category II employees (not covered

by the Agreement and in pay levels 1-14,

except Postmasters and Supervisors) were of

a minority group background, whereas

only 51.6% of Category IIX._ employees (not

covered by Agreement and' in pay levels 15

and above, including ' all Supervisors and

Postmasters) were of a minority group

- 11 -

reasons that the percentage of black

supervisory employees has Increased over

the years was due to a decrease in the pool

of white employees, which left managment

with fewer opportunities to promote them.

(Tr. 20-21, 247). Although the situation

at the Washington Post office had Improved

considerably and a Black appointed Post

master in early 1974, these developments

all took place after Aikens filed his

initial EEO complaint in January 1974.

On August 27, 1966, Aikens was pro

moted to the position of Assistant Direc

tor, Operations Division for Transit Mails.

He was.not detailed or promoted above that

V continued

“ should be noted

the appointment of ” bllck JSstmletf

pr^^-^Brfev’ r ^ TpPS^f a n a l a g e r s ^ o ^ "

- 12 -

position until January 9, 1974, a period of

more than seven years. (Stip. 6; J.A. 7).

Upon his appointment to the position of

Assistant Director in 1966, Aikens was the

highest ranking black supervisor in the

Washington, D.C., Post Office and remained

so until January 8, 1972, a period of more

than five years (Stip. 5; J.A. 7). No

other black employee advanced above the

level of the plaintiff until March, 1973,

when William Gordon's position of Assistant

Director, Operations Division for Local

Services, was reclassified from PFS-15 to

PES-23 (Tr. 128-129).

This upgrading occurred only nine

months prior to Aikens' initial complaint

and was due solely to the JEP reclassifica

tion of job levels, not to a promotion

action. During the ^same period, while

respondent did not advance, the following

whites, inter alia, all of whom were junior

- 13 -

to Aikens in supervisory seniority, contin

ually progressed in their careers, being

detailed or promoted to higher levels:

Dominic M. Barranca, Francis A. Miller,

Ellsworth H. Rapee, and Marvin G. Thomas

(Stip. 7; J.A. 7). These same individuals

ultimately occupied the four positions at

issue in this case.

From August 1966 to JEP in March 1973,

there were only four positions higher than

Aikens' position in the Washington, D.C.

Post Office: Director, Installation

Services (PFS-17); Assistant Director,

Operations Division for Distribution

(PFS-16); Director, Operations Division

(PFS-17); and Postmaster or Officer In

Charge (PFS-18). (Stip. 19; J.A. 8).

During the same period, six white persons

were detailed and/or promoted into one or

more of the above positions a total

- 14 -

of 29 times (Stip. 20-22; J.A. 8-9).-^

From July 1971, when C.G. Beall vacat

ed the Postmaster's position, until JEP

in 1973 there was only one board for the

8/ The positions, persons detailed, and

date of details were as follows (see, Stip 28 and 29; J.A. 9-10.

(a) Director, Installation Services;L.M. Lieb (07-26-71), (10-26-71),

(09-09-72 until retirement in December 1973).

(b) Assistant Director, Operations

Division for Distribution: L.M.

Lieb,* (05-04-7 1 ), ( 1 1-14~'71); E.C.

Ray,* (07-26-71), (10-22-71); F.A.

Miller, (05-26-73), (08-24-73),

(11-21-73); M.G. Thomas, (02-17-73),

(05-17-73); D.M. Barranca,* (11-06-

71), (09-08-72), 12-06-72); L.V.Bateman, Jr., (02-21-71).

(̂ ) Director, Operations Division; E.H. Rapee * (detailed 05-04-71 until

promotion on 03-04-72), (03-04-72 to

06-23-72); E.C. Ray,* (06-24-72),

(09-24-72), (12-23-72); D.M. Bar

ranca,* (02-17-73), (05-17-73),(08-15-73), (11-12-73J. -

II * n indicates those persons eventually promoted over respondent.

■Vi;*-.

'K- ■

- 15 -

positions of Director, Operations Division

and Assistant Director Operation Division

for Distribution (Stip. 25; J.A. 9).

Respondent Aikens (PFS-15) was the second

choice of the Promotion Advisory Board for

each of these positions, with the selec

tions being forwarded to the Officer In

Charge on February 25, 1972. (Stip. 26;

J.A. 9). This resulted in E.H. Rapee's

promotion to Director, Operations Division

(PFS-17) and in L.M. Lieb's promotion to

Assistant Director, Operations Division for

Distribution (PFS-16) on March 4, 1972

(Stip. 25; J.A. 9). That same Board ranked

t

D.M. Barranca (PFS-14) third behind Aikens,

even though Barranca had been detailed to

the position of Acting Assistant Director,

Operations Division, for Distribution on

November 6, 1971. (Stip. 27; J.A. 9).

Nevertheless, on September 8, 1972, only

six months after he had been selected below

- 16 -

A ikens for the above position by the

Promotion Advisory Board, Barranca was

detailed to the position of Assistant

Director, Operations Division for Distribu

tion. (Stip. 31; J.A. 10).-"̂

During the same period, subsequent to

the promotion board in February 1972 which

resulted in the promotions of Lieb and

Rapee to the positions of Assistant Direc

tor, Operations Division for Distribution

and Director, Operations Division, respec

tively, both were detailed to other jobs,

which left the above positions open for

details by others. Under the circum—

Both Lieb and Rapee subsequently were

detailed to new jobs within a short period

of time after their promotions of March 4,

1972; Lieb was again detailed on September

9, 1972, to Acting Director, Installation

Services, where he remS^ined until his ^stirement in December 1973, and Rapee was

detailed to the position of Officer In

Charge on June 24, 1972, where he remained

until January 1974. (Stip. 30; J.A. 10).

- 17 -

stances, the evidence shows that, at those

times, Aikens would have been the individ

ual most qualified to be detailed and/or

promoted to the Director, Operations

Division position, or at the very least, to

the position of Assistant Director, Opera

tions Division for Distribution. Yet once

again, his white colleagues were detailed

c

while Aikens remained frozen in the same

position he had occupied since 1966 (see,

Stip. 21-24; J.A. 8-9).

On March 3, 1973, Aikens' position.

Assistant Director, Operations Division for

Transit Mails was reclassified to PES-20

under JEP (Stip. 37; J.A. 10). As a result

of the position being ranked at PES-20, he

was no longer eligible for the position of

Postmaster, Washington, D.C. (Stip, 38;

J.A. 11). In the nine months between JEP

and Aikens' promotion on January 9, 1974 to

- 18 -

PES-21, he appealed the PES-20 rating.— '̂

The testimony showed that Aikens

wanted to be promoted to a level PES-23 or

above, since this would keep him in conten

tion for the Postmaster's job, but not to a

level below PES-23, since he felt this

would jeopardize his reclassification

appeal. (Tr. 74, 81-82). Subsequent to

JEP, Aikens was not detailed or promoted to

one of several unfilled higher level

positions for which he was qualified and

which would have placed him at a level

which was within the area of consideration

for Postmaster, even though junior white

10/ The higher job classification, which

Aikens sought when his position was rated

PES-20 instead of PES-23, was delayed

during that period even though a position

as head of a facility over which Aikens had

supervisory responsibility "was rated at a level higher than that" of Aikens'. (Tr. 69, 70, 249; PI. Ex. 2. )

.** ■

- 19 -

males were placed in such pos it ions.

Daniel J. Thomas, white, who was

Aikens' Administrative Assistant from 1969

until approximately 1974 (Tr. 195), indi

cated that Aikens was a capable manager and

that the "operations that [Aikens] con

trolled were very efficient" (Tr, 202).

Thomas observed that all the individuals

being detailed or promoted above Aikens

were white and he questioned why Aikens was

not promoted. He considered the possibil-

11/ The following white persons were

detailed and/or promoted to positions at

the following levels higher than Aikens' level .(PES-20); F.A. Miller (PES-22); C.

Errico (PES-26); M.G. Thomas (PES-26); D.J.

Robertson (PES-24); A.J. Eckerl (PES-21);

J.J. Spelta (PES-23),- W.E. Hahn (PES-22)

(Stip. 24; J.A. 9). F.A. Miller was also

detailed three times to the position of

Assistant Director, Operations, and D.M.

Barranca was detailed three times to the

position of Director, Operations Division.

(Stip. 21-22; J.A. 8-9) Another example

was the position of Manager of Personnel

(PES-23) on September 29, 1973, in which

A.J. Eckerl replaced D.J. Robertson, who

, - 20 -

ity that race was a factor in Aikens not

receiving promotions or details to higher

. . 12/level positions.

D. Co mparison of Aikens and his— wh i te

coD-eaques.

In The Findings and Recommended

Decision (November 12, 1975) in this case

at the administrative level the EEO Com

plaints Examiner stated at page 6: "In a

1 1/ continued

was promoted to Employee and Labor Rela

tions Specialist (PES-24), for which Aikens

also was qualified. Management was willing

to laterally transfer Aikens to the Manager

of Personnel position sometime in 1971,

when it was rated PFS-15, but not promote

him to that position in September 1973 when

it was rated PES-23. (PL. Ex. 3d, 31; Tr.

319-322).

12/ Thomas stated that "these were people

^ o had worked for Mr. Aikens, the knowlege

they had acquired in the Postal Service

certainly came about as a result of their

contact with him, and it was from my pointof view a strange coincidence that_thesê

people were promoted and he was in a slo_t

at_a_^and_still" (Tr. 203) (Emphasis

supplied).

I:

- 21 -

discrimination complaint case the crucial

consideration in analyzing issues is

comparative information of the treatment

afforded complainant and members of his

group (other similarly-situated Black

employees) and the treatment afforded

similarly-situated non-members of his

group. Consequently, I will not review

on the merits complainant's and the selec-

tees' comparative qualifications...

(Emphasis supplied) Similarly, during the

trial before Judge Hart, the court ruled

that plaintiff's witnesses could not

compare the plaintiff's capabilities with

those of his white colleagues unless that

1witness had been a superior of the individ

ual being compared. The only supervisors

were Beall, Rapee, and whites they had

promoted over respondent. The Court, in

denying Counsel the opportunity to examine

witnesses about }:heir opinions of their

- 22 -✓

supervisors, stated, "You have records here

that show his qualifications, and appar

ently he was well qualified. The question

is not whether he was well qualified, the

question is whether he was not promoted

because of discrimination, not because he

was qualified." (Tr. 173-176)

The record shows that Aikens partici

pated in the first National Conference on

Equal Employment Opportunity in the

Postal Service in September 1967; subse

quently he was Chairman of the Post

master's E.E.O. Committee for a period of

three years. At the time of filing his

E.E.O. complaint he had been the E.E.O.

Administrative Officer for the City Post

Office for approximately two years (Stip.

15; J.A. 8). It was during that period of

time that Aikens did not advance beyond his

position of Assistant'"Director, Operations

Division for Transit Mails.

Ny-v-

■M-i

.-.rv;

- 23 -

There was no derogatory or negative

information found in plaintiff's official

personnel folder to indicate that he had

not fulfilled the requirements of his

position (Stip. 11; J.A. 7). in 1968

plaintiff was rated as "an outstanding

supervisor whose management abilities were

far above average" (Stip, 16; J.A. 8).

Of the four white supervisors who were

placed into the positions at issue here,

Miller completed 10th grade, Rapee completed

11th grade, Thomas completed high school,

and Barranca completed 8 months of college

(Stip. 12; J.A. 7). Moreover, Carlton

Beall, who was the Postmaster and later

District Postal Manager during the relevant

time period, had only completed the 10th

grade (Stip. 12; J.A. 7). Aikens has a

Master's Degree and had completed 3 years

residence on his Ph.D. (Stip. 14; J.A. 7).

Aikens had as many, or more, training and

- 24 -

development courses and seminars as did the

four white supervisors (stip. 17; J.A. 8),

and the four white supervisors were junior

to plaintiff in supervisory seniority

(Stip. 7; J.A. 7).

A comparison of the POD Form,7's which

contain transactions concerning promotions,

details, and other pertinent information

about the four white supervisors and Aikens

<«• EX. 3A, 3B, 3F, 3G, and 31) i„ oon-

junctlon with Aikens' form 6802x (PI. e x .

n shows that the majority of the four

white supervisors had no more experience in

various positions than Aikens prior to

their being promoted or detailed to posi

tions above that of Aikens. m fact, most

had less. 11/

No one, other than Aikens.

— A i k e n s hac3 occuDi ef ^ f~ho i •

et hods and F o r e m a n ;

c

Me

Tour Superinte?de'’„‘l"c^ Analyst; Assistant ^superintendent; Superintendent of Main

- 25 -

had any experience in the position of

Assistant Director, Operations Division

for Transit Mails, since that position was

13/ continued

Window Service; Tour Superintendent;

and Assistant Director, Operations Division for Transit Mails (PI. Ex. 3A).

Dominic Barranca, who was appointed to the

position of Director, Operations Division

had formerly occupied the following positions; Foreman; Survey Officer;

General Foreman; Assistant Tour Superintendent; Tour Superintendent; and Assistant

Director, Operations Division for Distribution (PI. Ex. 3B)

Francis Miller, who was appointed to the

position of Acting Mail Processing Represen

tative had formerly occupied the positions

of Foreman; Survey Officer; General Fore

man; Assistant Superintendent, AMF (under

Aikens' jurisdiction); Tour Superintendent; Assistant Director, Operations Division for Distribution (PI. Ex. 3F).

Ellsworth Rapee, who was appointed to

position of Customer Services Representa-

tive, had formerly occupied the following

positions: Foreman; Superintendent.Special Delivery Services; General Foreman;

Assistant Tour Superintendent; Tour Super

intendent; Director of Finance; Director,

Operations Division; and Officer In Charge (PI. Ex. 3G).

t

- 26 -

continually occupied by him during the

period in question.

In July 1972, Carlton Beall nominated

three persons for the Postmaster position,

none of whom was Aikens. Beall's first

choice was E.H. Rapee, who had been de

tailed to the position on June 24, 1972

(where he remained through January 4,

1974). The Regional Office added Aikens'

name as a candidate for Postmaster in

1 972, feeling he was qualified for the

position. (Stips. 23, 34, 35, 40; J.A. 7-

m — / After Aikens' name was added in

13/ continued

Marvin Thomas, who was appointed to the

position of Mail Processing Officer, formerly occupied the following positions:

Foreman; Survey Officer; General Foreman;

Assistant Superintendent, Registry; Assis-

tant Director, Operations Division for

Manager, Quality Control

14/ No other names were^^^d^d, even though

SIX or seven individuals were eligible.

-li.’ yr

V.'r‘; ..

- 27 -

1972 as a candidate, the list of four names

was never submitted to the selection board

during the nine month period when Aikens

was eligible for consideration (Stip. 36;

J.A. 10).

°̂ Experience as a factor in selection for higher level jobs. ~ ’

Although postal experience purported

to be the predominate qualification factor

considered for detail or promotion (Stip.

33; J.A. 1-9), Aikens, who had as much or

more varied experience than his white

colleagues, was never detailed and/or

promoted to a higher level position. The

testimony of both Aikens and Postmaster

Beall indicated that during the period from

r’'‘-

14/ continued

March 1972, in order to be eligible for the position of Postmaster, an

employee was required to be in a level 15

position and to have had six years of

ex^te^nsive management experience (Tr.

- 28 -

1966 through JEP in March 1973, only two

positions were discussed with Aikens, that

of Director of Finance and Director of

Personnel, both of which would have been

moves and thus not promotions for

Aikens. Thus, Aikens was never offered a

promotion or detail above the PFS-1-5 rating

of his position as Assistant Director,

Operations Division for Transit Mails prior

to JEP (Tr. 78-80, 311, 315-316).--^

In discussing the importance of the

two positions, Beall stated that "anyone

who understands the personnel procedures

and helps to direct them is quite an asset

because 80 percent of our problems were

%

with people, ' and that the Work Measurement

Postmaster Beall, testifying about his

discussion of the Finance position with

Rapee, stated that "Mr. Rapee_said he would

prefer not to take it, jDu't if I wanted him he would." (Tr. 319.) Although phrased

^ l y , this was the same position Aikens took regarding the Personnel position.

xf-

'V'"-Y..

J-'' ■

-n-

I

:?v

- 29 -

System under the Director of Finance "...

really was the crux of the total management

responsibility" (Tr. 312). However, Beall

also testified that those jobs (i. e. Per

sonnel and Finance), while they would

broaden someone's experience in the Postal

Service, were not absolutely necessary (Tr.

318). In fact, most of the white indivi

duals promoted or detailed above the

plaintiff did not have any experience in

either one of those areas.— ^

J_6/ Of the four white supervisors, Rapee,

Miller, Thomas and Barranca, who were placed into the positions at issue,

none w’as ever Director of Personnel, and

Ellsworth Rapee was the only one to occupy

the position of Director of Finance.

Beall, when testifying as to why he "of

fered" those positions to Aikens, stated that Aikens had "a good formal education

... good knowledge of the Postal Service,

and I though he could effectively handle

this...." Beall, however, did not think Dominic Barranca "was equipped to handle

that particular type of assignment...."

Beall also stated that he didn't discuss

the positions with Francis Miller or Marvin

- 30 -

Even though former Postmaster and

District Manager Beall testified, he never

gave any reasons as to why plaintiff

was not promoted or detailed above the

position of Assistant Director, Operations

Division for Transit Mails. The entire

record clearly shows that the plaintiff was

qualified for any position in the Washing

ton, D.C. Post Office, up to the Post

master s position, and that he was inter

ested in being promoted and/or detailed to

higher level positions. Although few

comparisons were made by witnesses as to

the relative capabilities of the plaintiff

and his white colleagues, what little there

was, in conjunction with the personnel

J_6/ continued

Thomas either because "it was a very

important assignment ... and I was inter

ested in the people that were best quali

fied for the job.... Naturally, you would

use what you consider the best equipped." (Tr. 318-319, 321-322.)

'v;

'i ■ ■

- 31 -

records, shows that the plaintiff was at

least as qualified, if not more so, than

the whites who were continually being

promoted and/or detailed to higher level

17/positions.—

The promotions that Aikens received in

1974 also attest to his qualifications to

perform work at higher levels of employ

ment. Only a few days after Aikens had

filed his employment discrimination com

plaint in January 1974, he received a

promotion to Area Logistics Manager, ranked

at job grade PES-21, Shortly thereafter,

he was detailed to the position of Assis-

y

tant Manager of Distribution, PES-24.

(App. E, p. 23a).

J_7/ For example, Louis Thompson indicated that Francis Miller was deficient in

communication because it was necessary for

him (Thompson) to "write all [Miller's]

letters for him because he couldn't write a decent report." (Tr. 228).

- 32 -✓

F• Anecdotal Evidence - Remarks That Be

tray Prejudice or Stereotyped Thinirinq

Petitioner has suggested that "anec

dotal" evidence has often been used to show

that supervisors have betrayed a predispo

sition towards discrimination (Brief, p.

25)o Respondent introduced such evidence,

which the trial court did not mention when

it held that plaintiff had failed to make

out a prima facie case. All the testimony

concerned Carlton Beall, who as Postmaster

and District Manager, essentially

controlled all selections to higher level

management positions.

Mr. Louis Thompson, a Black super

visor, testified that Mr. Beall once made«

the following statement to him about

blacks: "All they want to do is to lay

around and breed like yard dogs and collect

_1_8/ See n.6, supra,

■

'P

W'-

■ -< ■■■

JV-

A*:-'-

i

- 33 -

relief checks" (Tr. 220). His perception

of Beall, was that he "was operating on an

1865 concept .... would only want black

janitors. He very reluctantly gave any

ground as far as I could see.... I dealt

with him quite frequently and while we

didn't always agree I think he had a

contempt for black people. I still think

he has." (Tr. 219-220).

Mr. William F. Moore, Jr., a white

supervisor, testified that Mr. Beall was

always making remarks about Blacks. In

particular he remembered Mr. Beall remark

ing to an all white group at a meeting.

"Yoil know, they don't have to set (sic) in

the back of the bus anymore" (Tr. 250-251).

Mr. Malcom Christian, a black supervisor

testified that Mr. Beall referred to black

people as "'that crowd' practically all the

time ...," and that he frequently made

sarcastic comments about Mr. Aikens educa-

- 34 -

tion. (Tr. 252-254.)

Despite all of this evidence, most

of which was based on stipulated, and

therefore undisputable, facts or official

personnel records, the district court

held that plaintiff had not even made out a

£r _i m a facie case of discrimination.

It is the holding of the court of appeals

that this constituted error that is the

issue presented here.

Summary of Argument

I.

The positions advanced by petitioner

are founded upon a lack of appreciation of

the nature and extent of employment

discrimination. If adopted, they would

result in the effective overruling of

McDonnell Douglas v.,Gteen, 411 U.S. 792

(1975), and a substantial weakening of

Title VII as a remedial statute.

- 35 -

II.

The legislative history of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972 demon

strates Congress' concern with the perva

siveness of discrimination in employment in

American society. The protections of Title

VII were extended to federal employees

because of findings that minorities and

women continued to be excluded from high

level positions throughout the government.

Effective enforcement of the Act's provi

sions are necessary to root out this

entrenched discrimination.

III.

McDonnell Douglas v. Green and its

progeny have proved to be effective tools

to address claims of employment discrimina

tion. The lower courts have applied the

prima facie analysis in a flexible manner

to address the facts in particular cases.

- 36 - 37 -

Therefore, its continued vitality and use

are essential to the vigorous enforcement

of Title VII„

IV,

The decision of the court below was a

correct application of McDonnell Douglas v.

Green to the facts in this case. Plaintiff

clearly established a prima facie case, and

the decision should be affirmed.

ARGUMENT

'I.

Introduction

Although ordinarily the brief for

respondent would focus on the arguments

made by the petitioner, we feel it incum

bent to discuss a number of issues raised

by the present case not touched upon in the

Government's Brief to any substantial

degree. As will be^^,veloped in detail

below, there is a fundamental disagreement

between the views of the respondent and the

Congress of the United States, on the one

hand, and the Government and its supporting

amici on the other, with regard to the

extent and seriousness of racial discrimi

nation in employment in the United States.

The general thrust of the briefs of

the Government and amici is that Title VII

is something of a nuisance to employers.

Discrimination based on race, sex and other

prohibited categories is not, in their

view, a-serious problem. Nevertheless, em

ployers and labor unions are unduly besieg

ed by lawsuits that misuse Title VII to

attack non-discriminatory, race-neutral,

and fair employment practices. Thus, they

arfe seeking from this Court rules which

would make it difficult, to the point of

near impossibility, for plaintiffs to bring

or maintain actions under Title VII.

Although they do not explicitly so

state, they in reality are seeking the

■

- 38 -

✓

overruling of McDonnell Douglas Corp. v

G r ^ , 411 u.S. 792 (1975) and its prog-

Jl/eny, at least insofar as those decisions

provide a straight-forward and expeditious

way for a plaintiff to establish a prima

faci^ case of discrimination, and thus to

permit a court to move to an investigation

of the employment practices which have

given rise to the complaint. They seek

insulation from having to defend employment

practices by requiring the plaintiff,

as a condition of simply going forward with

his or her case, practically to prove the

entire case. in essence, they wish to

avoid having even to start mounting a

defense to a charge of discrimination

unless they already know that they have

iP^nco Construction Coro, v. Waters. 38 U.S. 567 (1978); Board of Trustees of

College v. Sweeney. 439 U.S. 24

j. . Texas Department of Community Af-fairs V. Burdine, 4T 6 u.S. 2T 8 0 9 8 1 7 .

Bi:

■/i"'

’i'Au I

&

- 39 -

virtually no defense at all.

Respondent suggests that the adoption

of these views, which are typical of

defendants in Title VII cases, will turn

the statute on its head. The rules urged

by petitioner essentially presuppose that

there is no discrimination in employment

and that the plaintiff has a heavy burden

to prove otherwise. Of course, as McDon

nell Douglas and its progeny fully recog

nize, the .ultimate burden of proof in a

particular employment discrimination case,

as with any other type of civil litigation,

rests with the plaintiff and we do not seek

to escape that burden. However, the rules

by whi-ch a prima facie case can be estab

lished in these cases stem from the Court's

sensitivity to and awareness of the so

cietal concerns that led to the passage of

Title VII in 1964 and its expansion in

1972.

- 40 -

The Acts reflect a national consensus

that discrimination based on race and sex

has been a pervasive problem in American

society. Moreover, one of the main foci of

that problem was employment, in which

Blacks, other minorities, and women were

consistently relegated to lower paying

positions regardless of their qualifica

tions or merit, and where, conversely,

white males enjoyed special privileges and

benefits. Given the pervasive and all

encompassing nature of the problem. Con

gress not only enacted Title VII in 1964,

but strengthened it and broadened its scope

by the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of

1972. Section 717, which extended Title

VII's provisions to federal government

agencies, was enacted because of findings

by Congress that the federal government had

failed in its constitutional duty to

correct discrimination in its own ranks.

- 41 -

Even subsequent to 1972, when it

enacted the Civil Service Reform Act of

20/19/8 and approved reorganization measures

dealing with the enforcement of federal

2 1/sector EEO, Congress found that dis

crimination and the lack of equal employ

ment opportunity was still a serious

2 2/problem in the federal government.—

Of course. Congress has done nothing

to date to indicate it has changed its view

as to the seriousness of discrimination in

the federal sector; nor has it done any

thing to indicate that discrimination among

I

private employers and state and local

2^/ P.L. 95-454; 92 Stat. 1111.

2^/ President's Reorganization Plan No. 1, 1978 (1978 U.S. Code Cong. & Adm. News, p. 9795).

2^/ See, Part II, infra, for a discussion of the 1978 Act.

- 42 -

government agencies has ceased to be a

serious problem. If, however, the views of

the government and its amici are adopted,

there will be a judicial weakening of a

statute enacted and reenacted by Congress

as a matter of considered judgment. We,

therefore, respectfully suggest that the

approach taken by petitioner must be re

jected. As we will show, the decision be

low is fully consistent with the decisions

of this Court and with the purpose of Title

VII. Therefore, it must be affirmed and

the case remanded to the district court for

further proceedings.

Before proceeding with the discussion

of the pertinent legislative history and

its relevance to the issues presented

herein, however, we believe it is necessary

to put the position taken by the government

in the present case in its historical

context. The government opposed the

- 43 -

K

'4“ .

iv*-'

I

:

f-■f;'

V:.fi/;'

M:

p

I

passage of § 717 in 1 9 7 2 oiiowing its

enactment the government, primarily through

the Civil Division of the Department of

Justice and the offices of the United

States Attorneys acting as defense counsel,

vigorously sought to restrict the enforce

ment of Title VII against it by taking a

series of positions which would have

limited the judicial remedies available to

f

The Civil Service Commission testified against the passage of Section 11 of

S.2515, the original version of § 717.

See, Statement of Irving Kator, Assistant

Executive Director, U.S. Civil Service

Commission, in Hearings Before the Subcom-

^ittee on Labor of the Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, U.S. Senate, Oct. 4, 6

and 7, 1971, pp. 297-304. The CSC's

opposition focused on two points: (1) thetransfer of authority over federal EEO to

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

(later deleted from the statute); and (2)

the need for establishing the right of

federal employees to obtain judicial relief for discrimination. At the same time the

CSC opposed Section 11, of S.2515, it

expressed support for H.R. 1746 which, as

it passed the House, had iio provis ion

similar to § 717 covering federal employees.

- 44 -

federal government employees and which

would have placed the government in a

favored position with regard to both the

procedural and substantive rules governing

such actions.

The sequence of cases and strategy

employed by the government to limit the

scope and effectiveness of Title VII is a

long one and can only be summarized here.

The keystone of the government's assault on

Section 717 was its argument that federal

employees, unlike all others, were not

entitled to a trial de novo when they

got in court. From this argument flowed

arguments that federal employees were not

' 24/entitled to maintain class actions, re-

, ̂ 25/ceive counsel fees,— or obtain other

24/ See, Pointer v. Sampson, 62 F.R.D. 689

(D.D.C. 1974).

25/ See, Letter from Irving Jaffee, Acting

Asst. Attorney General to Senator John

Tunney, May 6, 1975 (reprinted in C.C.H.,

Employment Practices Guide II 5327 (1975)),

t ’

I

I

i:'VA'

i'

$'t-

I

'•Jv'

- 45 -

types of relief except under narrow

26/circumstances.

The government lost the trial ^ novo

battle as a result of this Court's decision

in Chandler v. Roudebush, 425 U.S. 840

27/(1976).— Following Chandler the govern

ment took, for the first time, an enlight

ened view of Section 717, and announced

that as a general policy it would not argue

26/ See, Day v. Mathews, 530

(D.C. Cir. 1976).

F.2d 1083

27/ In other litigation the government was

forced to change a number of its rules

relating to the administrative enforcement

of Ti’tle VII. Thus, the government was

ordered to permit the filing of class

action complaints administratively.

Barrett v. U.S.C.S.C., 69 F.R.D. 544 (D.D.C.

1975). Court action was similarly required

to bring about the reform of practices such

as the refusal to grant attorneys' fees for

work done during the administrative process( S miJt _C a 1_ j. f̂ ̂n o , 446 F. Supp. 530

(D.D.C. 1978); see. New York Gaslight Co.

V. Carey, 447 U.S. 54, 61, n.2 (1980)), and

to impose proper rules for granting relief once there had been an administrative

finding of discrimination.

- 46 -

✓

that it was subject to special rules. It

abandoned its position with regard to class

actions and stated that it would no longer

argue that different types of relief were

28/available to nongovernment employees.—

This approach was, unfortunately,

short lived. More recently the government

has argued, for example, that the rules for

calculating attorneys' fees in Title VII

cases should be different when the govern-

2 9/ment is defendant, that a federal court

28/ The change in policy was announced

after Chandler and a series of appellate

court decisions holding that federal

employees had the same right to maintain

class actions in Title VII cases as did all other employees (Eastland v. T.V.A.,

553 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1977); Williams v.

T.V.A. , 552 F.2d 691 (6th Cir. 1977 )).

See, Memorandum for United States Attorneys

and Agency General Counsels Re; Title VII

Litigation, from Attorney General Griffin

B. Bell (Aug. 31, 1977) (reprinted in CCH

Employment Practices, 5046 ( 1977 )).

2 9/ See, Copeland v. ̂ a^hall, 641

880 (D.C. Cir. 1980). F.2d

- 47 -

should not enforce a final administrative

decision in a complainant's favor,— “̂and,

successfully to date, that federal employ

ees, unlike all others covered by Title

VII, cannot receive adjustments in back pay

awards to account for the factor of infla-

̂ o , • 31/tion or other delays in payment.—

The point to be made in recounting

this history is that the government as a

defendant in Title VII actions has been

less than 'enthusiastic about the statute,

and the positions it takes in its Brief

32/here reflect that attitude. Indeed, it

30/ See, Houseton v. Nimmo, 670 F.2d 1375 (9th Cir. 1982)..

31/ See, Saunders v. Claytor, 629 F.2d 596

(9th Cir. 1980); Blake v. Califano, 626 F.2d 891 (D.C. 1980).

32/ The government's lack of enthusiasm

has generally been shared by its amici.

See, e.g., Hill, "The AFL-CIO and The Black

Worker: Twenty-five Years After the Mer

ger", 10 Journal of Intergroup Relations 5, 36-44, 53-58 (1982).

- 48 -

is noteworthy that the brief contains

virtually iio discussion of the legislative

33/history of either the 1964 or 1972 Acts,—

nor any discussion of Congress' findings,

purposes, and concerns in enacting them.

Rather, it to a large extent consists of a

discursive account of alleged difficulties

employers have in selecting employees and

in defending Title VII cases.

V7e suggest that the picture painted by

the government and its amici is simply

inaccurate. Employers are not overburdened

by defending Title VII cases. Indeed, if

anything, the volume of cases is too small

given the extent and nature of employment

«

discrimination in our society. The rela

tively low number of cases is a reflection

of the inequality of burdens in these

33/ Petitioner's entire discussion of the

history of the 1972 Act is found in note 19, p. 24, of its Brief.

■M-i

h.',5C--

¥

t

■T.k’

I

■

w

%

I

- 49 -

cases. Bringing a Title VII action against

an employer, particularly when that

employer is an agency of the government of

the United States, is an intimidating

proposition beyond the resources of most

employees. In an individual case of

discrimination, a federal employee is

faced with overwhelming counter-resources,

including attorneys from the United States

Attorney's office, agency counsel, and, in

many instances, lawyers from the Department

34/of Justice itself. Ordinarily, vir

tually all of the relevant information

is in the hands of the agency, which is

I

defended by attorneys expert in the use of

the federal rules to their advantage.

34/ Unlike private and state and local

government employes, the federal employee

stands alone. There is no public attorney

general to aid in prosecuting his lawsuit. See, Parker v. Califano. 561 F.2d 320, 331

(D.D.Cir. 1977).

- 50 -

Contrary to the government's unsup

ported assertions, a typical federal

employee case goes into court either after

there has been virtually no processing of

his EEO complaint, or after a decision

of the agency charged that it has not been

guilty of discrimination. Thus, the

government, at pages 26-27 of its Brief,

makes a number of claims concerning the

administrative processing of federal EEO

complaints. Any suggestion that this

administrative process has proved generally

successful as a means for rooting out

employment discrimination in the federal

3_5/ Section 717 permits a -federal employee

to file in court 180 days after filing the

administrative complaint if there has been

no final agency decision. Although this

provision was enacted because of Congress' concern over delays in processing federal

EEO complaints (see the parallel provisions

in the Civil Service Refo'rm Act of 1978, 5

U.S.C. § 7702(e)(1)), most agencies take

substantially longer on the average to

process complaints. Therefore, many court

complaints are filed prior to hearings or final decisions.

- 51 -

sector is supported neither by fact nor in

36/counsel's experience.

In any event, this Court held similar

assertions by the government irrelevant in

Chandler v. Roudebush, supra, given Con

gress' intent to provide federal employ

ees with the same broad rights in court as

those enjoyed by all other employees. Any

argument that more stringent burdens should

be imposed on federal employees for them to

establish a prima facie case because of the

purported, but illusory, benefits of the

administrative process should similarly be

rejected.

36/ See, Hackley v. Roudebush, 520 F.2d T08, 137-141 (D.C. Cir. 1975); Ralston,

"The Federal Government as Employer:

Problems and Issues in Enforcing the Anti-Discrimination Laws," 10 Ga. L.

Rev. 717 (1976); Brief of the NAACP LegalDefense and Educational Fund, Inc., as

amicus curiae, in Chandler v. Roudebush,

425 U.S. 840 (1976).

- 52 -

If the employee has had resources to

hire counsel, or has been fortunate enough

to find an attorney willing to take the

case without fee contingent upon eventually

prevailing, there may have been developed

during the administrative process some

reasonably decent record. This is often,

however, not the case and extensive dis

covery, expenditure of funds, and legal

resources are necessary to flush out the

information necessary to proceed with the

case.

A substantial number of litigated

cases are resolved in favor of the govern

ment; a large number more are never brought

or. If they are, are settled early be

cause of problems in the case or lack

of resources on the part of the plaintiff.

By and large those cases that get to trial

are ones in which th^e-rip loy ee has a

substantial case, and not ones where he or

I:

IV'-'

I

f

ft

r..

» ■

- 53 -

she can do no more than simply make

out a prima facie case of discrimination.

Thus, the alarms raised by the government

as to why the rights of plaintiffs need to

be further cut back are simply false

ones.

Finally, we suggest that it is even

somewhat unseemly for the federal govern

ment to be seriously arguing that it is an

unnecessary burden to it that its employees

be permitted to challenge decisions made by

it on the ground that they may be the

result of discrimination. We believe

rather, with Congress, that the govern

ment'^ proper role is to serve as a model

for the rest of society and all other

employers in its diligence and concern to

root out unlawful discrimination in every

respect as it relates to its own employ-

- 54 -

37/ees. Without such an example by those

charged with enforcement of the laws, it

can hardly be expected that private

employers will take seriously their own

responsibilities.

22/ As the Senate Report on the 1972 Act noted;

The Federal government, with 2.6

million employees, is the single

largest employer in the Nation.

It also comprises th|e central policy

making and administrative network for

the Nation. Consequently, its poli

cies, actions, and programs strongly

influence the activities of all other

enterprises, organizations and groups.

In no area is government action more

important than in-^'he area of civil rights. X

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92d Cong., 1st Sess.), p. I z .

- 55 -

II.

The Legislative History of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Act of 1972

Supports the Continuing Vitality of

McDonnell Douglas v. Green and The

Decision of the Court Below. ____

It is clear from the legislative

history of the Equal Employment Opportunity

Act of 1972 that when Congress decided to

make Title VII fully applicable to federal

agencies it was concerned not only with the

exclusion of minorities from the federal

service,’ but specifically with their

exclusion from high level positions.

Congress addressed these problems in three

main 'ways. First, it expanded the powers

of the United States Civil Service Commis

sion and mandated that it provide effective

administrative enforcement of the EEO

38/complaint process At the same time.

38/ 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-16(b).

- 56 -

It provided federal employees for the first

time, the clear right to go to court to

enforce not only their rights under Title

VII, but also their pre-existing rights

under Executive Order 11 478 .— ^ Finally

Congress mandated that all federal agencies

institute effective affirmative .action

programs, including training to permit all

employees to reach their full potential, in

order to upgrade the positions of minori

ties and women in the federal service.— /

STs .a !? 425'S.'sf 820°u 976k ''

£2./ 42 U.s.c. s 2000p-lfî ĥ Athe effort to orovi^o ^employment oddot -̂ equality of

servlc/e CongrllraJso " a*'" f^'^^alService Commission with the*̂ r̂ the civil Of examining all of its Pmol ^responsibility

cations and criteria to qualifi-

t c t t h e s t a n d a r d i s e r b r i : “h7s

concerned wi^h °"tre'“ ar’'rlwL"sr Commission's belief thi? « intent" on the oart ̂ malicious

supervisor needed to particularNo. 92-415 (92d ron^ ^ Ptoven. s . Rep.

14-1 5. ' Sess. 19 71), pp.

- 57 -

Congress' concern with the concentra

tion of minorities and women in lower

levels in the federal service was part of

an overall concern with their exclusion

from the better, more profitable, and more

prestigious positions and occupations in

American society as a whole. Thus, both

the Senate and House Reports referred

specifically to data demonstrating that

minorities and women were concentrated in

certain types of jobs and excluded from

4- V, 11/otners. ^t the same time Congress

recognized that the problems of racial

discrimination originally addressed in the

1964 Civil Rights Act had proven more

41 / S. Rep. No. 92-415 (92d Cong., 1st

Sess. 1971), p. 6; H. Rep. No. 92-238 (92d Cong., 1st Sess. 1971), p. 4. Both reports

cited the exclusion of Blacks from profes

sional and managerial positions as evidence that they were "still far from reaching

their rightful place in society." S. Rep.

No. 92-415, p. 6.

- 58 -

complex, deep rooted, and intractable

than believed in 1964. Thus, the Senate

Report acknowledged that:

In 1964, employment discrimina

tion tended to be viewed as a series

of isolated and distinguishable events, for the most part due to ill-

will on the part of some identifiable

individual or organization. It was

thought that a scheme that stressed

conciliation rather than compulsory

processes would be most appropriate

for the resolution of this essentially human" problem, and that litigation

wcpuld be necessary only on an occa

sional basis. Experience has shown this view to be false.

Employment discrimination as viewed today is a far more complex and pervasive phenomenon. 42/

Thus, contrary to the belief of

petitioner, it was Congress' judgment when

it decided to strengthen and broaden the

scope of Title VII that discrimination in

employment was indeed pervasive in American

society and needed to j^e'^ooted out relent-

42/ S. Rep. No. 92-415, p. 5.

f

- 59 -

lessly. With regard to federal government

agencies specifically, both the Congres

sional reports and testimony before both

houses explored and attested to the

existence of discriminatory practices

inherent in the federal system and also

suggested changes to address the problem.

Congress found in the concentration of

blacks and women in lower grade levels

throughout the government evidence both of

employment discrimination and of the

failure of existing programs to bring about

equal employment opportunity. Thus, the

House Report stated:

Statistical evidence shows that

minorities and women continue to be

excluded from large numbers of govern

ment jobs, particularly at the higher grade levels . . . .

This disproportionate distribu

tion of minorities and women through

out the Federal bureaucracy and their

exclusion from higher level policy

making and supervisory positions

- 60 -

indicates the government's failure to pursue its policy of equal oppor

tunity. 43/

The Senate report similarly concluded from

statistics showing the concentration of

minorities and females in the lower grade

levels that "their ability to advance to

44/the higher levels has been restricted."—

Thus, the facts of this case present

a prime example of what Congress was most

concerned with. As noted supra, at n.7,

as of February, 1974, immediately following

the filing of respondent's administrative

complaint, while Blacks were 85% of the

work force at the Washington, D.C. work

force, they held only 50% of supervisory

and management positions. The top posi

tions had been held by whites pr'ior to

43/ H. Rep. No. 92-238, p. 23.

4j4/ S. Rep. No. 92-415, pp. 13-14,

- 61 -

January, 1974, and the respondent had been

repeatedly passed over in favor of whites

for details and promotions.

Of course. Congress was deeply con

cerned that the federal government should

serve as an example to' others in avoiding

discriminatory practices. The House report

states:

The Federal service is an area

where equal employment opportunity is

of paramount significance. Americans

rely upon the maxim "government of the

people", and traditionally measure the quality of their democracy by the

opportunity they have to participate

in government processes. It is

therefore imperative that equal

opportunity be the touchstone of

the Federal system. 45/

45/ House Report No. 92-238, p. 22. See,

also, the Senate Report quoted at n.37,

infra, and the remarks of Rep. Badillo, 117

Cong. Rec. 32, 101 (1971) to the effect that the government needed to "put its own

house in order in terms of ending its own

discriminatory employment practices."

- 62 -

✓

The legitimacy of Congress' concern is

demonstrated by testimony before both

Houses. Witnesses testified during

both House and Senate Hearings that there

was a general lack of confidence in the

effectiveness of the existing EEO complaint

Process on the part of Federal employees.

Richard Williams, Chairman of the Equal

Employment Opportunity Committee of Mary

land, an organization of employees of the

Federal Government in Maryland, stated,

"Racially discriminatory practices in Fed

eral employment continue to be so rampant

and widespread that the administration of

the equal employment opportunity program by

the Civil Service Commission has proved to

be a failure." Rep. Fauntroy, of the

£6/ Hearings before the General Subcommit

tee on Labor of the Committee on Education and Labor — House o f epresentat ives ,

Washington, D.C., December 2, 1969, p. 146.

- 63 -

District *of Columbia, testified to the

thousands of complaints he had received

from Black federal employees in the Dis

trict. His own father had experienced

discrimination strikingly similar to that

4 7/suffered by respondent here.—

In sum, as this Court has noted.

Section 717 was enacted because the "long

standing Executive Orders forbidding

discrimination had proved ineffective for

£7/ My father ... trained two generations

of white employees who were then

passed up and over the shoulder to

higher level and higher paying jobs.

From all the evidence I have seen,

even today in this supposedly enlight

ened time, these practices continue

daily with little substantive change.

Senate Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Labor of the Senate Committee on Labor and

Public Welfare, Oct. 4, 6, and 7, 1971, p.

202.

See also,testimony of Clarence Mitchell, Director, Washington Bureau of the NAACP

and Legislative Chairman of the Leadership

Conference on Civil Rights before the Labor

Subcommittee of the House Committee on

Education and Labor, March 3, 1971, pp.153-59.

- 64 -

the most part" and to correct [the]

entrenched discrimination in the Federal

service . . . . Morton v. Mancari, 417

U.S. 535, 546-547 (1974); Brown v. General

Services Administration. 425 U.S. 820,

825-28 (1976). See also, Clark v. Chasen.

619 F.2d 1330 , 1332 ( 9th Cir. 1980 ).— ^

Thompson v. Sawyer. ___ F.2d ___, 28 F.E.P.

Cases 1614, 1640 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 8 2 ).--'^

48/ ("Congress was deeply concerned with

the Government's abysmal record in minority employment

19/ The accuracy of Congress' judgment is

attested to by the series of decisions

finding class-wide systemic discrimination

in various federal agencies, including the

postal service. See, McKenzie v. McCormick.

425 F. Supp. 137 (D.D.TT 1977) (Government

-rinting Office); Thompson v. Sawver. 28 F.E.P. Cases 1614 (D.C. Cir; 1982) (Govern-

ment Printing Office); Segar v. Civilehhi.

508 F. Supp. 690 (D.D.c7 1981) (Drug En-

forcement Administration); Clark v. Alex-

aMer, 489 F. Supp. 1236 (D.D.C. 1980 ),

(Department of the Army); Trout v. Hidaloo,

517 F. Supp. 873 (D.D.C. 1581) (Department

Of the Navy); Harrison v. Lewis (D.D.C.,

v-iv. Act. 79-1816, June 7, 1982 ) (Maritime

1.

- 65 -

Subsequent to the 1972 Act Congress

took further measures to correct discrimi

nation in employment in both the federal

and private sectors. Thus, the Civil Ser

vice Reform Act of 1978 reaffirms and in

corporates by reference section 717 of the

1972 Act and provides new provisions for

50/its enforcement.— Congress approved

shifting the responsibility for administra-

tj-ve enforcement to the Equal Eijployment

Opportunity Commission because of continu

ing dissatisfaction with the adequacy of

the role of the Civil Service Commis-

5 1/sion. The 1978 Act also reaffirms

4 9/ continued

Administration). Chisholm v. United States

Postal Service, 655 F.2d 482 ( 4th Cir.1981) . But see, Valentino v. United States

Postal Service, 674 F.2d 56 (D.C. Cir.

1982) .

50/ See 5 U.S.C. §§ 2302(b )(1)(A ),(d );

1206; 7121(d); 7702.

51/ President's Reorganization Plan No. 1,

1978.

- 66 -

the affirmative action obligations of

federal agencies in a variety of ways,

including the strengthening of provisions

requiring minority recruitment and mandat

ing that high level federal officials be

rated on their EEO and affirmative action

performances.— ^

With regard to promotions specific-

ally, Congress enacted a new system for

appraising the performance of federal

employees. The key substantive provision,

which requires that performance appraisals

be based on objective criteria related to

the job in question was enacted spe

cifically with Title VII concerns in mind

because of the recognition that reliance on

subjective criteria could form the basis

52/ See, 5 U.S.C. §§ 2302(d); 7201;4313(5).

^ / 5 U.S.C. § 4302(b) (1).

- 67 -

54/for discrimination.