Craig v. Florida Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Craig v. Florida Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Florida, 1965. f3b4c78a-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/228fdbef-aac4-4c2f-9a9c-fdc095727511/craig-v-florida-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-florida. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

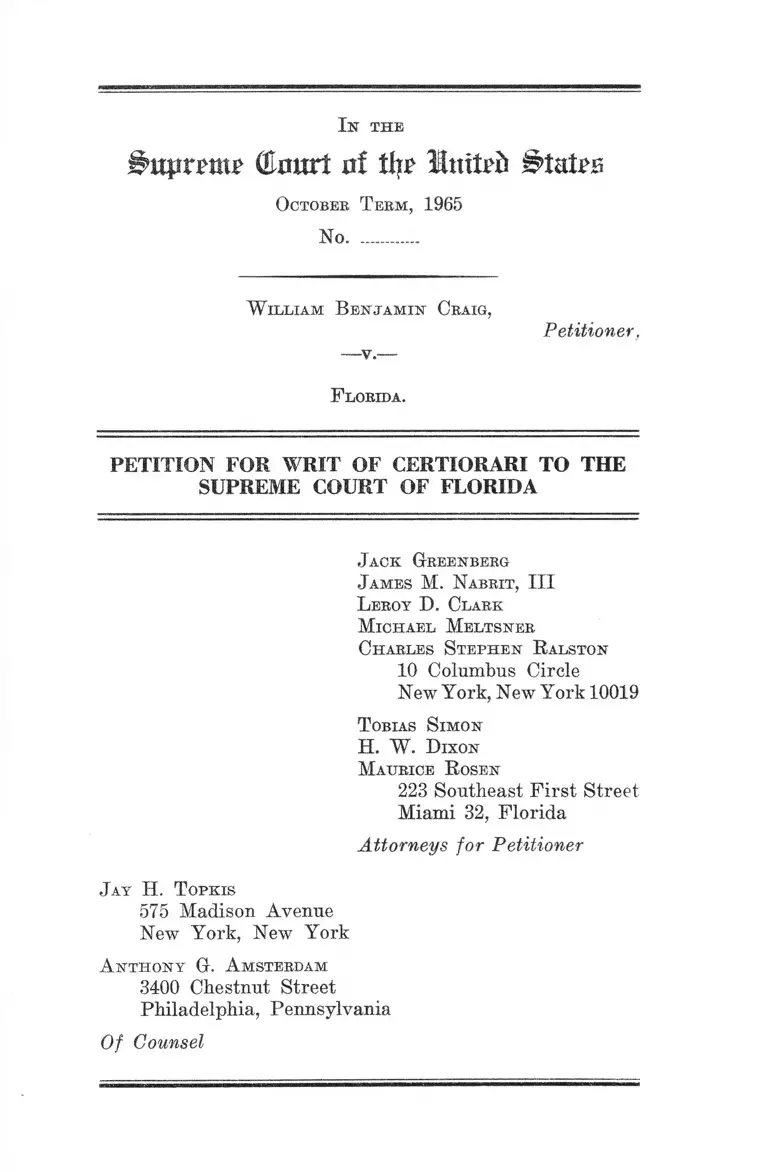

I n t h e

m tu ' (Emtrt n! thp United States

O ctobeb T erm , 1965

No..............

W illiam B e n ja m in C raig,

— v . ----

Petitioner,

F lorida.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

J ack G reenberg

J am es M . N abrit , III

L eroy D . C lark

M ic h ael M eltsneii

C harles S teph en R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T obias S im on

H. W. D ixon

M aurice R osen

223 Southeast First Street

Miami 32, Florida

Attorneys for Petitioner

J ay H . T opkis

575 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Of Counsel

I N D E X

Opinion B elow ....................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction .................................................... -..................... 1

Questions Presented ....... ................................................... 2

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved ..... 2

Statement ................................................-............................. 3

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and De

cided Below ............. 9

Reasons for Granting the Writ ....................................... 10

I. Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine

Whether the Application to Petitioner of

Florida’s Death Penalty for Rape Is Uncon

stitutional Because an Unrebutted Prima

Facie Showing Has Been Made of Its Racial

Application in Violation of the Equal Protec

tion Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment .... 10

II. The Court Should Grant Certiorari to Con

sider Petitioner’s Contention That His Sen

tence Is Unconstitutional Under the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments .................... ...... 19

III. The Court Should Grant Certiorari to Decide

Whether Florida’s Single Verdict Procedure

Allowing the Jury Which Determines Guilt

Simultaneously to Fix Capital Punishment

for Rape Violates the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment ....................... 22

PAGE

Conclusion 27

11

T able of C ases

page

Aaron v. Holman, U.S. Dist. Ct., M.D. Ala., C.A.

No. 2170-N ............... .............. -.... -.......... - ................ .. 13

Alabama v. Billingsley, Cir. Ct. Etowah County,

No. 1159 .................................................. -........................ 13

Bell v. State, 93 So.2.1 575 (1957) .............. ........ ..... - 7, 8

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 ..........- 18

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110 .......... ........................ 14

Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S. 445 ...................... - 18

Formally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385 .... 18

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 ........... .......................... - 18

Craig v. State, 168 So.2d 747 (Fla. 1964) ................ 3

Craig v. State, 179 So.2d 202 (Fla. 1965) ........... ..1,5,10

Davis v. State, 123 So.2d 703 (1960) .................. 7,23,24

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 — ........... ............. - 18

Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67 (1953) .......... . 14

Frady v. United States, 348 F.2d 84 (D.C. Cir. 1965) .... 26

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 ............................... 18

G-iacco v. Pennsylvania, ------ U.S. ------ , 34 U.S.L.W.

4099 .................. ...... ....... ........ ....... -.... -.... - .................. 20

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 .................... ......... 15

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 ...... — ................ - 14

Harris v. State, 162 So.2d 262 (1964) .................. .. 7

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 ........ ................ — 14,15

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242 .............................— 18

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U.S. 368 ....... ...... ....... ............ 24, 26

Ill

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 ..... ...... ........ ......... 17

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 ....................... 18

Louisiana ex rel. Scott v. Hanchey, 20th Jud. Dist. Ct.,

Parish of West Feliciana .............................................. 13

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 ................... ... 15,17

Malloy v. Hogan, 378 U.S. 1 _______ _____ ___ ____ _ 22

Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965)

cert, denied,------ U.S. ------- , 15 L.ed.2d 353 ........... 13,19

Mitchell v. Stephens, 232 F. Supp. 497 (E.D. Ark.

1964) ....... ..... ................. ............................. .................... . 13

Moorer v. MacDougall, U.S. Dist. Ct., E.D.S.C.,

No. AC-1583 ........ .............................................................. 13

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 ............................... 18

Nash v. United States, 54 F.2d 1006 (2d Cir. 1932),

cert, denied, 285 U.S. 556 ........................................... 23

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U.S. 370 (1881) .................. ........ 14

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 ............................... 14

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587 ....................................... 15

Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 ................................... 15

Peterson v. City of Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 ............... 17

Ralph v. Pepersack, 335 F.2d 128 (4th Cir. 1964),

cert, denied, 380 U.S. 925 ......... ............. ................... 19

Raulerson v. State, 102 So.2d 281 (1958) ................... . 7

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153 ................ .............. 17

Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889 ...............................19, 21

Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 50 ....................... .......... 8

Sims v. Georgia, 144 S.E.2d 103 ........ ......... ............. . 13

PAGE

IV

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535 .............................. 21

Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553 ____________ _________ 18

Swain v. Alabama, Ala. Sup. Ct., 7 Div. No. 699,

cert, denied, ------ U.S. ------ , 15 L.ed.2d 353 ........... 13

Tniluck v. State, 108 So.2d 748 (1959) ....................... 7

United States v. Curry, ----- F.2d ------ (2nd Cir.

No. 29000, Dec. 22, 1965) .... ..... ........ .............. ........... . 26

United States ex rel. Rucker v. Myers, 311 F.2d 311

(3rd Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 844 ............... 26

United States ex rel. Scoleri v. Bonmiller, 310 F.2d 720

(3rd Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 828 ................... 26

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964) ....... 25

Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241 ........................... 23, 25

Williams v. Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576 ...... ...... ............. 23

Williams v. State, 110 So.2d 654 (1959) ...................... 23

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 ......................... . 18

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 .............................. 14

F ederal S tatutes

Civil Rights Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §1,

14 Slat, 27 ................ ............ .......................... ........... . 13

Enforcement Act of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16, 18,

16 Stat. 140 ................. ........... ....... ............... .............. . 13

Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, Rule 32(a) ....... 26

Rev. Stat. §1977 (1875) ............ ......... ................................ 13

10 U.S.C. §920 (1964) ........................................................ 11

18 U.S.C. §2031 (1964) ............................ ......................... 11

PAGE

18 U.S.C. §2113(e) ............................................................25,26

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) ........................................................ 1

42 U.S.C. §1981 (1964) ....... 13

S tate S tatutes

Ala, Code §§14-395, 14-397, 14-398 (Recomp. Vol.

1958) .......................................................................... ....... 10

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§41-3403, 41-3405, 41-3411, 43-2153

(1964 Repl. Vols.) ....... .... ............................ ................ . 10

D.C. Code Ann. §22-2801 (1961) ...................................... 11

Fla. Const., Art. 16, §24 .................................................. 17

Fla. Stat. Ann., Chapter 924, Florida Criminal Proce

dure Rule No. 1 ............................... .............................. 9

Fla. Stat. Ann. §§741.11-741.16 ...................................... 17

Fla. Stat. Ann. §794.01 (1964 Cum. Supp.) ....... 3, 5, 9,10,

19, 22

Fla, Stat. Ann. §798.04 ...................................................... 17

Fla. Stat. Ann. §798.05 .. ................................................ 17

Fla. Stat. Ann. §913.11 ................. ..................................... 24

Fla. Stat. Ann. §921.13 ...................................................... 23

Ga, Code Ann. §§26-1302, 26-1304 (1963 Cum. Supp.) .... 10

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.090 (1963) ...... ................. ...... 10

La, Rev. Stat. Ann. §14:42 (1950) ............. ..................... 10

Md. Ann. Code, art. 27, §12, §§461, 462 (1957) ........ . 10

Miss. Code Ann. §2358 (Recomp. Vol. 1956) ............. . 10

Vernon’s Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.260 (1953) .................. 10

Nev. Rev. Stat. §200.360, §200.400 (1963) ................ ..... . 10

N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-21 (Recomp. Vol. 1953) .......... 10

Okla. Stat. Ann., tit, 21, §§1111, 1114, 1115 (1958) ____ 10

PAGE

VI

S.C. Code Ann. §§16-72, 16-80 (1962) .......... .......... ..... 10

Tenn. Code Ann. §§39-3703, 39-3704, 39-3705 (1955) 10

Tex. Pen. Code Ann. arts. 1183, 1189 (1961) ...... ........ 11

Va. Code Ann. §18.1-16, §18.1-44 (Repl. Vol. 1960) ....... 11

O th e r A uthorities

A.L.I., Model Penal Code, Tent. Draft No. 9 (May 8,

1959), Comment to §201.6.......... .......... ........ ................ 23

tenBroek, Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States, 39 Ca l if . L. R ev . 171 (1951) .... 13

Bullock, Significance of the Racial Factor in the

Length of Prison Sentences, 52 J. Ceim. L., Cbim. &

P ol. S ci. 411 (1961) ........... ....... .............. .................... 17

Cong. Globe, 39th Cong. 1st. Sess. 475, 1758, 1759

(1/29/1866, 4/4/1866) .... ....... ............................. ........ 14

Fairman, Does the Fourteenth Amendment Incor

porate the Bill of Rights, 2 S t a n . L. R ev . 5 (1949) .... 13

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment,

284 A nn als 8 (1952) ................... .................. ............ . 17

Letter of Deputy Attorney General Ramsey Clark to

the Honorable John L. McMillan, Chairman, District

of Columbia Committee, House of Representatives,

July 23, 1965, New York Times, July 24, 1965, p. 1,

col. 5 .... ........................ ...... ..... ...... ............. ................... 21

Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great Expectations [1963]

S uprem e C ourt R eview 101 ................ .................... . 18

Note, 109 U.Pa.L.Rev. 67 (1960) ..................................... 18

PAGE

V l l

Packer, Making the Punishment Fit the Crime,

77 Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964) ...................................20, 21

United States Department of Justice, Bureau of

Prisons, National Prisoner Statistics, No. 32; Ex

ecutions, 1962 (April 1963) ......... ......... .................. . 11

Weihofen, The Urge to Punish (1956) ........ .............. 17

Wolfgang, Kelly &Nolde, Comparison of the Executed

and the Commuted among Admissions to Death Row,

53 J. Crim. L., Cbim. & P ol. Sci. 301 (1962) ........ . 17

PAGE

In t h e

(Burnt nf % Irnfrft BM?b

O ctober T erm , 1965

No..............

W illiam B e n ja m in C raig ,

Petitioner,

—v.—

F lorida.

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida entered in

the above-entitled case on October 13, 1965.

Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Florida and the

dissenting opinion of Judge Ervin are reported at 179

So.2d 202. They are set forth in the Appendix, pp. la-16a.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Florida was

entered October 13, 1965. The time for filing this petition

for writ of certiorari was extended by Mr. Justice Fortas

to and including February 11, 1965. The jurisdiction of

this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1257(3),

petitioner having asserted below and asserting here dep

rivation of rights secured by the Constitution of the

United States.

2

Questions Presented

1. Petitioner, a Negro, has been sentenced to death for

the rape of a white woman. He has shown that in the

past twenty-five years only one white man has been exe

cuted for rape, and that for the rape of a white child under

aggravated circumstances. On the other hand, twenty-nine

Negroes have been executed, all for the rape of white

adult women. No white or Negro male has ever been

executed for the rape of a Negro, child or adult. In con

trast, the number of Negroes convicted for rape is only

slightly higher than the number of whites. Under these

circumstances, has petitioner made sufficient showing of a

denial of the equal protection of the laws in violation of

the Fourteenth Amendment to require the State to come

forward with some evidence that the disproportion of

Negroes executed for rape is not accounted for by race?

2. Does the imposition of the death penalty for the

offense of rape by the State of Florida on the basis of

the jury’s unfettered, unreviewable discretion constitute

cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth

and Fourteenth Amendments?

3. Does the assigning to the jury in a capital rape case

under Florida law the function of deciding simultaneously

both the guilt of the defendant and the penalty to be in

flicted constitute a denial of due process of law in viola

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment?

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves the Eighth Amendment and Section 1

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

3

This case also involves the following statute of the

State of Florida:

Section 794.01—Rape and forcible carnal knowledge;

penalty.

Whoever ravishes and carnally knows a female of

the age of ten years or more, by force and against

her will, or unlawfully or carnally knows and abuses

a female child under the age of ten years, shall be

punished by death, unless a majority of the jury in

their verdict recommend mercy, in which event pun

ishment shall be by imprisonment in the state prison

for life, or for any term of years within the discretion

of the judge. It shall not be necessary to prove the

actual emission of seed, but the crime shall be deemed

complete upon proof of penetration only.

Statement

Petitioner William Benjamin Craig was indicted on June

6, 1963, by the Grand Jury of Leon County, Florida for

the crime of rape upon a female person over the age of

ten years. Petitioner Craig is a Negro and the victim is

an adult white female. He was tried before a jury in the

Circuit Court of the Second Judicial Circuit in and for

Leon County. Under provisions of Florida law, the same

jury considered simultaneously the questions of the guilt

of petitioner and the sentence to be imposed. The jury

returned a verdict of guilty without a recommendation

of mercy on June 20, 1963 (R., p. 6).

On June 27, 1963, a judgment and sentence of death was

entered by the Court. An appeal was taken from the ver

dict and sentence, they were affirmed October 21, 1964, by

the Supreme Court of Florida (Craig v. State, 168 So.2d

4

747; R., pp. 32-34), and an order denying a petition for

rehearing was entered December 7, 1964.

On February 10, 1965 petitioner filed a motion for re

duction of sentence from death to life imprisonment or

less in the Circuit Court of Leon County. The bases for

the motion were that:

(1) Imposition of the death penalty on petitioner denied

him the equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the

Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution of the United

States because the death penalty had been used as an

instrument of racial discrimination against Negroes con

victed of the rape of white women.

(2) The procedure under Florida law which allows the

jury which determines the guilt of a person accused of

rape also to determine simultaneously the punishment to

be imposed violated the due process clause of the Four

teenth Amendment.

(3) The imposition of the death sentence for rape sub

jected the petitioner to cruel and unusual punishment and

violated due process of law in violation of the Eighth and

Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution. (See Record,

pp. 8-10.)

In support of this motion the petitioner introduced

statistical data regarding the imposition of the death

penalty for rape. The State did not object to or contra

dict the data and it was accepted as accurate by the trial

court in deciding the motion for reduction of sentence

(R., p. 26).1 The motion for reduction of sentence was

1 The Court said:

The Defendant offered to prove up the statistics therein contained

with the respective files of each of the 285 convictions from the

several Florida counties involved should this Court feel such proof

5

denied in the trial court on February 17, 1965 (R., p. 26).

An appeal was taken to the Supreme Court of Florida,

and on October 13, 1965, the decision of the trial court

was affirmed by the Supreme Court of Florida (179 So.2d

202). (Appendix, pp. la-3a.) Judge Ervin dissented on the

ground that by permitting the same jury to decide both

the guilt and punishment of the petitioner the State had

denied due process of law in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution (179 So.2d

at 204-210). (Appendix, pp. 3a-16a.)

Capital Punishment for Rape

In his motion for reduction of sentence, petitioner main

tained that Section 794.01 of the Florida statutes, which

imposes the death sentence for the crime of rape, was

unconstitutional as applied to him. In support of this

contention, statistics were introduced which revealed the

pattern of discrimination against Negroes in the imposi

tion of the death sentence.2 The statistics, which were ac-

desirable or necessary in addition to the verification o f the memo

randum brief by counsel. This Court does not feel that such proof

is required, desirable or necessary, and for the purposes of this

motion accepts the statistics contained in the memorandum as sub

stantially correct. The State of Florida voiced no objection to this

procedure (R., p. 26).

2 This footnote sets out in tabular form the statistics discussed in the

text infra:

TABLE A

R ape Convictions 1940-1964

T otal : D epen dant V ictim

(Negro) (White) (Indian) (Negro) (White)

285a 152 68b 84c

132 7 125a

1 0 1

(footnote 2 continued on next page)

6

cepted as accurate by the trial court, may be summarized

as follows:

During the 25-year period between January 1, 1940 to

December 31, 1964, there have been a total of 285 convic

tions for the crime of rape for which information con

cerning the race of the victims and the defendants is avail

able.3 (R., p. 18) One hundred and thirty-two white men,

or 46% of the total, have been convicted for the rape of

125 white and 7 Negro women (Ibid.). One hundred and

fifty-two Negro men, or 54% of the total, have been con

victed for the rape of 84 white and 68 Negro women (Ibid.).

The remaining conviction was that of an Indian who raped

2 ( continued) TABLE B

D isposition of 54 R ape D efen dants Sentenced to D e a th ,

b y R ace of D efen dant and R ace of V ictim —1940-1964

Defendant Victim

Negro White Negro White

30 Electrocutions 29 0 29

1 1®

5 Commutations 2 0 2

3 0 3e

12 Awaiting Execution 12 2e 10

1 Killed 1 0 1

6 Death Judgment

Reversed 4 1 3

2 0 2

Totals 54 48 6 3 51

a— Excluding 13 eases from Brevard and Hillsborough Counties because

race information is unavailable,

b— Includes 26 children under 14.

c—Includes 3 children under 14.

d—Includes 34 children under 14.

e— Children under 14.

(R., pp. 21-22)

3 There were 13 other cases in two counties for which no information

as to race was available (R., p. 18).

7

a white woman. Fifty-four men have been sentenced to

death for rape; 48 Negroes and six whites (R., p. 14).

There have been 125 cases of white females being raped

by white men; 34 of the victims were children under 14

(R., p. 19). Six white men have been sentenced to death

for these offenses but only one has been electrocuted (R.,

p. 19). The single white man actually electrocuted, Robert

Wesley Davis, was convicted of raping an eleven-year old

white child under extraordinarily aggravated circumstances

(see, Davis v. State, 123 So.2d 703 (Fla., I960)).

Of the other five whites originally condemned to die,

three raped white children ranging in age from 9 to 13,

and in all three cases the State Pardon Board commuted

their sentence to life imprisonment (R., p. 15). The final

two were co-defendants convicted of raping a single white

adult (R., p. 15). The jury verdicts finding them guilty

without recommendation of mercy were reversed by the

Supreme Court of Florida which found that the judgment

of death had been the result of prejudicial comments made

by the trial judge. Raulerson v. State, 102 So.2d 281 (1958).

No white man has been electrocuted for the rape of a white

adult or even sentenced to death for the rape of a Negro

adult or child.

The remaining 48 men who received sentences of death

were all Negroes (R., p. 16). Of these, 29 have already

been electrocuted, and 12 others are presently awaiting

execution on death row at the Florida State Prison (R.,

pp. 16-17). The death sentences of four other Negroes wrere

reversed by the Supreme Court of Florida (R., p. 17)

(.Harris v. State, 162 So.2d 262 (1964); Bell v. State, 93

So.2d 575 (1957); Truluck v. State, 108 So.2d 748 (1959));

they thereafter received lesser sentences. A sheriff killed

one Negro en route to a new trial after his conviction was

8

reversed by Shepherd v. Florida, 341 U.S. 50. The Pardon

Board commuted the death sentences of the remaining two

Negroes who wrnre given the death penalty for rape (R.,

p. 17).

Of 84 convictions of Negro men for the rape of white

women, 45 resulted in sentences of death (53%) (R., p. 19).

Only one of these cases involved the rape of a white child.

Thus, 44 Negro defendants have been sentenced to death

for the rape of white adult women; 29 of them have been

executed and ten await execution (Ibid.).

On the other hand, in the 68 cases in which Negro males

have been convicted of raping Negro women (26 cases in

volving children under 14), only three have been sentenced

to death. All three of these convictions were for attacks

on children; two defendants are presently awaiting exe

cution (Ibid.). The third conviction was reversed by the

Supreme Court of Florida. (Bell v. State, 93 So.2d 575

(1957).) Therefore, to date no Negro has been electrocuted

for the rape of another Negro adult or child.

Statistics introduced with regard to the actions of the

Florida State Board of Pardons also show a disparity in

the treatment of white and Negro defendants. The Board

has heard 38 appeals for clemency from convicted rapists

out of the 54 death sentences for rape, and commuted three

of the four white death sentences. On the other hand, it

denied relief to 32 of the 34 Negro applicants (R., p. 20).

These results contrast sharply with treatment afforded

those convicted of murder. Since January 1, 1924, the

Pardon Board heard pleas from 216 convicted murderers,

of which 129 were Negroes and 85 white, and two of un

known race. Thirty-three, or 25.6%, of the Negroes and

21, or 24.7%, of the whites secured commutation of sen

9

tence (R., p. 20). In other words, for murder, no racial

factor seems to operate in deciding clemency applications.

To summarize, between January 1, 1940 and December

31, 1964, fifty-four men were sentenced to death in Florida

following convictions for the crime of rape. Six of the 54

men who received the death sentence were white, the bal

ance, 48, were Negroes. However, only one white was

actually executed (for the aggravated rape of a white

child), while ,29 Negroes have been electrocuted, (all of

whom were convicted of raping white adult women) and

twelve others (ten of whom raped white women) are pres

ently awaiting execution.

These statements of fact are not disputed. No inference

other than one of racial discrimination in application of

the death penalty has been offered.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

After the affirmance of his conviction and sentence by

the Supreme Court of Florida on June 27, 1963, petitioner

filed a motion for reduction of sentence from death to a

term of years in the Circuit Court of Leon County (R.,

pp. 8-10). The ground for the motion was that the sentence

of death was a denial of the equal protection of the laws

and of due process of law in violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Therefore, See. 794.01, Fla. Stat. Ann., was unconstitu

tional on its face and as applied to him. The motion was

denied, and petitioner appealed to the Supreme Court of

Florida. That court accepted jurisdiction, considering the

motion as a collateral, post-conviction assault on a judg

ment of conviction within the scope of the Florida Criminal

Procedure Rule No. 1, Fla, Stat. Ann., Chapter 924, Ap

10

pendix. The denial of the motion by the lower court, up

holding the statute as valid under the federal Constitution,

was affirmed on the merits. (179 So.2d at 204.)

Reasons for Granting the Writ.

I.

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Determine Whether

the Application to Petitioner o f Florida’ s Death Pen

alty for Rape Is Unconstitutional Because an Unre

butted Prima Facie Showing Has Been Made o f Its

Racial Application in Violation o f the Equal Protec

tion Clause o f the Fourteenth Amendment.

Seventeen American States retain capital punishment for

rape. Nevada permits imposition of the penalty only if

the offense is committed with extreme violence and great

bodily injury to the victim;4 5 the remaining sixteen juris

dictions—which allow their juries absolute discretion to

punish any rape with death—are all southern or border

states.6 The federal jurisdiction and the District of Colum

4 Nev. Rev. Stat. §200.360 (1963). See also §200.400 (aggravated

assault with intent to rape).

5 The following sections punish rape or carnal knowledge unless other

wise specified. Ala. Code §§14-395, 14-397, 14-398 (Recomp. Yol. 1958);

Ark. Stat. Ann. §§41-3403, 43-2153 (1964 Repl. V ols .); see also §41-3405

(administering potion with intent to rape); §41-3411 (forcing marriage);

Fla. Stat. Ann. §794.01 (1964 Cum. Supp.) ; Ga. Code Ann. §§26-1302,

26-1304 (1963 Cum. Supp.) ; Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. §435.090 (1963); La.

Rev. Stat. Ann. §14:42 (1950) (called aggravated rape but slight force

is sufficient to constitute offense; also includes carnal knowledge); Md.

Ann. Code, art. 27, §§461, 462 (1957) ; see also art. 27, §12 (assault with

intent to rape); Miss. Code Ann. §2358 (recomp. Vol. 1956); Vernon’s

Mo. Stat. Ann. §559.260 (1953); N.C. Gen. Stat. §14-21 (Recomp. Yol.

1953); Okla. Stat. Ann., tit. 21, §§1111, 1114, 1115 (1958); S.C. Code

Ann, §§16-72, 16-80 (1962) (includes assault with attempt to rape as

well as rape and carnal knowledge); Tenn. Code Ann. §§39-3702, 39-3703,

11

bia, with its own strong southern traditions, also allow

the death penalty for rape.* * * * 6

Between 1930 and 1962, two years before petitioner was

sentenced to die, 446 persons were executed for rape in

the United States. Of these, 399 were Negroes, 45 were

whites, and 2 were Indians. All were executed in southern

or border States or the District. The percentages—89.5%

Negro, 10.1% white— are revealing when compared to

similar racial percentages of persons executed during the

same years for murder and other capital offenses. Of

the total number of persons executed in the United States,

1930-1962, for murder, 49.1% were Negro; 49.7% were

white. For other capital offenses, 45,6% were Negro;

54.4% were white. Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Vir

ginia, West Virginia and the District of Columbia never

executed a white man for rape during these years. Together

they executed 66 Negroes. Arkansas, Delaware, Florida,

Kentucky and Missouri each executed one white man for

rape between 1930 and 1962. Together they executed 71

Negroes. Putting aside Texas (which executed 13 whites

and 66 Negroes), sixteen Southern and border States and

the District of Columbia between 1930 and 1962 executed

30 whites and 333 Negroes for rape: a ratio of better than

one to eleven. Clearly, unless the incidence of rape by

Negroes is many times that of rape by whites, capital

punishment for rape survives in the twentieth century

principally as an instrument of racial discrimination.7

39-3704, 39-3705 (1955); Tex. Pen. Code Ann., arts. 1183, 1189 (1961);

Va. Code Ann. §18.1-44 (Repl. Vol. 1960); see also §18.1-16 (attempted

rape).

s 18 U.S.C. §2031 (1964); 10 U.S.C. §920 (1964); D.C. Code Ann.

§§22-2801 (1961).

7 The figures in this paragraph are taken from U nited States D epart

m e n t of J ustice , B ureau of P rison s , Natio n al P risoner Statistics ,

No. 32; Executions, 1962 (April 1963). Table 1 thereof shows the follow-

12

If this be so—if the racially unequal results in these

States derive from any cause which takes account of race

ing executions under civil authority in the United States between 1930

and 1962:

MURDER

Total White Negro Other

Number 3298 1640 1619 39

Per Cent 100.0 49.7 49.1 1.2

RAPE

Total White Negro Other

Number 446 45 399 2

Per Cent 100.0 10.1 89.5 .04

OTHER OFFENSES

Total White Negro Other

Number 68 37 31 0

Per Cent 100.0 54.4 45.6 0.0

Table 2 thereof shows the following executions under civil authority in the

United States between 1930 and 1962, for the offense of rape, by State:

White Negro Other

Federal 2 0 0

Alabama 2 20 0

Arkansas 1 17 0

Delaware 1 3 0

District o f Columbia 0 2 0

Florida 1 35 0

Georgia 3 58 0

Kentucky 1 9 0

Louisiana 0 17 0

Maryland 6 18 0

Mississippi 0 21 0

Missouri 1 7 0

North Carolina 4 41 2

Oklahoma 0 4 0

South Carolina 5 37 0

Tennessee 5 22 0

Texas 13 66 0

Virginia 0 21 0

West Virginia 0 1 0

45 399 2

1 3

as a factor in meting out punishment—a Negro punished

by death is denied, in the most radical sense, the equal

protection of the laws.8 One of the cardinal purposes of

the Fourteenth Amendment was the elimination of racially

discriminatory criminal sentencing. The First Civil Eights

Act of April 9, 1866, ch. 31, §1, 14 Stat. 27, declared the

Negroes citizens of the United States and guaranteed that

“ such citizens, of every race and color, . . . shall be subject

to like punishment, pains, and penalties [as white citi

zens], and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.”

The Fourteenth Amendment was designed to elevate the

Civil Rights Act of 1866 to constitutional stature. See, e.g.,

tenBroek, Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution of

the United States, 39 Ca lif . L. E ev . 171 (1951); Fairman,

Does the Fourteenth Amendment Incorporate the Bill of

Rights, 2 S t a n . L. R ev . 5 (1949). The Enforcement Act

of May 31, 1870, ch. 114, §§16, 18, 16 Stat. 140, 144, im

plemented the Amendment by re-enacting the 1866 act and

extending its protection to all persons. This explicit stat

utory prohibition of racially discriminatory sentencing sur

vives today as R ev . S tat . §1977 (1875), 42 U.S.C. §1981

(1964). * 7

8 The contention that racially discriminatory application of the death

penalty in rape cases denies equal protection has been raised in a number

o f cases now pending in state and federal courts. See, e.g., Mitchell v.

Stephens, 232 F. Supp. 497, 507 (E.D. Ark. 1964), appeal pending;

Moorer y. MacDougall, U.S. Dist. Ct., E.D.S.C., No. AC-1583, appeal

pending; Aaron v. Holman, U.S. Dist. Ct., M.D. Ala., C.A. No. 2170-N,

proceedings on petition for writ of habeas corpus stayed pending ex

haustion of state remedies July 2, 1965; Swain v. Alabama, Ala. Sup. Ct.,

7 Div. No. 699, petition for leave to file petition for writ of error

coram nobis denied June 25, 1965, cert, denied, —— U.S. ------ , 15

L.ed.2d 353; Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F.2d 325 (8th Cir. 1965), cert.

denied, ------ U.S. ------ , 15 L.ed.2d 353; Alabama v. Billingsley, Cir. Ct.

Etowah County, No. 1159, motion for new trial and motion for reduction

o f sentence pending; Sims v. Georgia, 144 S.E.2d 103, petition for cert,

pending, Misc. 918; Louisiana ex rel. Scott v. Hanchey, 20th Jud. Dist.

Ct., Parish of West Feliciana, petition for habeas corpus pending.

1 4

For purposes of the prohibition, it is of course im

material whether a State writes on the face of its statute

books: “Rape shall be punishable by imprisonment . .

except that rape by a Negro of a white woman, or any other

aggravated and atrocious rape, shall be punishable by death

by electrocution,” or whether the State’s juries read a

facially color-blind statute to draw the same racial line.

Discriminatory application of a statute fair upon its face

is more difficult to prove, but no less violates the State’s

obligation to afford all persons within its jurisdiction the

equal protection of the laws. See, e.g., Yick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356; Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S. 268 (alter

nate ground); Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67; Hamil

ton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 (per curiam). And it does not

matter that the discrimination is worked by a number of

separate juries functioning independently of each other

rather than by a single state official. However it may divide

responsibility internally, the State is federally obligated to

assure the equal application of its laws. This Court has

long sustained claims of discriminatory jury exclusion upon

a showing of exclusion continuing during an extended

period of years, without inquiry whether the same jury

commissioners served throughout the period. E.g., Neal v.

Delaware, 103 U.S. 370; Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U.S. 110;

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475. Congress, when it en

acted the 1866 Civil Rights Act knowing that “In some com

munities in the South a custom prevails by which different

punishment is inflicted upon the blacks from that meted

out to whites for the same offense,” 9 intended precisely by

the Act, and subsequently by the Fourteenth Amendment,

to disallow such “ custom” as it operated through the sen

tences imposed by particular judges and juries.

3 Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 1758 (4/4/1866) (remarks of

Senator Trumbull, who introduced, reported and managed the bill which

became the act.) See also, Id., at 475 (1/29/1866) and 1759 (4/4/1866).

15

The petitioner asks this court to consider whether he has

not made a showing of racially discriminatory capital sen

tencing under Florida’s rape statute sufficient to throw some

burden of explanation on the state. Because of the Four

teenth Amendment’s overriding purpose to secure racial

equality, “ racial classifications [are] ‘constitutionally sus

pect,’ . . . and subject to the ‘most rigid scrutiny’ .”

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184, 192. This principle

has as its corollary that a sufficient initial showing of un

equal treatment of the races is made whenever it appears

that the races are substantially disproportionately repre

sented in groups of persons differently disposed of under

those procedures: such a showing compels the inference

that a State is drawing the racial line unless the State

offers some justification in non-racial factors for the dis

proportion. See, e.g., Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587;

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475; Gomillion v. Lightfoot,

364 U.S. 339; cf. Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633.

Here the demonstrated disproportion is extreme. Over

a twenty-five year period, between January 1, 1940 and

December 31, 1964, 48 of the men sentenced to die for rape

were Negroes and only 6 were white—a ratio of eight to

one. The evidence also shows that this disparity cannot be

accounted for by a greater number of Negroes being con

victed for rape, since in the same period 152 Negroes, 132

Whites, and 1 Indian were so convicted.

The Florida statistics take on added significance when the

race of the rape victim is considered. In the twenty-five

year period only one white man was actually executed and

that was for the rape of an eleven year old white child

under extremely aggravated circumstances. Of the five

other whites sentenced to death (but whose sentences were

either reversed or commuted) three had raped white chil

16

dren ranging in age from nine to five, and the other two

had raped a single white adult.

All twenty-nine of the Negroes who have been executed,

and ten of the twelve presently awaiting execution, were

convicted of raping white women. (The other seven Ne

groes sentenced to die have had their sentences of death

reversed by a higher court, or have had their death sen

tences commuted by the Pardon Board.) A total of forty-

four of the forty-eight Negro defendants have been sen

tenced to death or electrocuted for the rape of white adult

women. No Negro or white, to date, has been electrocuted

for the rape of a Negro adult or child. Three other Negroes

have been sentenced to death for raping Negro children,

with one having his conviction reversed by the Supreme

Court of Florida. (See Statement, supra.)

This is at least sufficient evidence to make an initial

showing of racial discrimination and to transfer the burden

of explanation to the State. While determination of the

relative influence of the racial factor, as opposed to factors

arising from the circumstances of the individual cases,

would be aided by data detailing the facts of each prosecu

tion for rape, the burden should be on the state to demon

strate the countervailing influence of such factors since it

should have the responsibility of rebutting the inference

raised by the above statistics, and since if such a showing

can be made, the state has the resources available to do so.

The trial court, and the Supreme Court of Florida, al

though accepting the correctness of petitioner’s statistical

showing, held that the Florida statute was constitutional

both on its face and as applied to petitioner without dis

cussion. No attempt was made by the state at any part of

the proceeding to explain or justify the discrepancy in the

application of the death penalty clearly demonstrated by

the statistics summarized above.

17

This Court should hold that the State may not thus re

main silent in the face of such a record. Several considera

tions support the holding.

First, the hypothesis of racial discrimination is particu

larly likely in view of the coincidence between the Florida

figures and those of the other jurisdictions—all southern—

which have executed persons for rape during the past thirty

years. For all jurisdictions, the Negro-white ratio is nine

to one—although for other crimes than rape it is about one

to one. Studies and observations by students of the crimi

nal process tend to support the hypothesis of discrimina

tion. E.g., Bullock, Significance of the Racial Factor in the

Length of Prison Sentences, 52 J. G r im . L., Cr im . & P ol.

S ci. 411 (1961); Wolfgang, Kelly & Nolde,. Comparison of

the Executed and the Commuted among Admissions to

Death Row, 53 J. Cr im . L., Cr im . & P ol. S ci. 301 (1962);

Hartung, Trends in the Use of Capital Punishment, 284

A nn als 8, 14-17 (1952); W eih o een , T h e U rge to P u n ish

164-165 (1956).

Second, put in the context of the broader picture of

Florida life and law, the inference that these death penalties

were racially motivated becomes overwhelming. Florida

still by statute forbids the intermarriage of whites with

Negroes, (Fla. Const., Art. 16, §24; Fla. Stat. Ann. §§741.11-

741-16), and only recently was its statute prohibiting inter

racial cohabitation struck down by this Court. McLaughlin

v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184. (Fla. Stat. Ann. §798.05. See also,

§798.04.) The lesson the State thus officially teaches its citi

zens respecting the abhorrence in which even voluntary

interracial sexual relations should be held cannot help but

have an impact on the views which a criminal jury will hold

of an interracial rape. Cf. Peterson v. City of Greenville,

373 U.S. 244; Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267; Robin

son v. Florida, 378 U.S. 153.

18

Finally, in this context, the absolute discretion which

Florida law gives jurors to decide between life and death,

undirected by any rational standards for making that deci

sion (see part II infra), invites the influence of arbitrary

and discriminatory considerations. This Court has long

been concerned with a vagueness of criminal statutes which

“ licenses the jury to create its own standard in each case.”

Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S. 242, 263. See, e.g., Smith v.

Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553; Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274 U.S.

445; Connolly v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385;

Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507. The vice of such

statutes is not alone their failure to give fair warning of

prohibited conduct, but the breadth of room they leave for

jury caprice and suasion by impermissible considerations,

N.A.A.C.P. v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 432-433; Freedman v.

Maryland, 380 U.S. 51, 56; Lewis, The Sit-In Cases: Great

Expectations, [1963] S uprem e C ourt R eview 101, 110;

Note, 109 U.Pa.L.Rev. 67, 90 (1960), including racial con

siderations, see Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145;

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479; Cox v. Louisiana, 379

U.S. 536. Unlimited sentencing discretion in a capital jury

presents this vice in the extreme. To paraphrase Joseph

Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495, 505: “Under such a

standard the most careful and tolerant [lay juror] . . .

would find it virtually impossible to avoid favoring one

[race] . . . over another.”

Petitioner requests the Court to grant certiorari to re

view" and reverse the judgment of the Supreme Court of

Florida, which left the sentence of death standing after

petitioner had made an unrebutted prima facie showing that

he had been denied equal treatment in the most grievous

penalty known to law.

19

II.

The Court Should Grant Certiorari to Consider

Petitioner’ s Contention That His Sentence Is Uncon

stitutional Under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amend

ments.

Petitioner alleged that he was unconstitutionally sen

tenced without consideration of aggravating or mitigating

circumstances, pursuant to §794.01 of the Florida Statutes

Annotated, which statute on its face and as applied pre

scribes the imposition of cruel and unusual punishment in

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. This question,

which three Justices of the Court thought deserving of

certiorari in Rudolph v. Alabama, 375 U.S. 889, has been

deemed by both the Fourth and Eighth circuits as one

which “must be for the Supreme Court in the first instance.”

Maxwell v. Stephens, 348 F.2d 325, 332 (8th Cir. 1965)

cert, denied, .... . U.S.........., 15 L.Ed. 2d 353. The Fourth

Circuit has taken the same view. Ralph v. Pepersaclc, 335

F.2d 128, 141 (4th Cir. 1964), cert, denied, 380 U.S. 925.

Petitioner respectfully requests the judgment of the Court

on the issue.

The question posed is not whether on any rational view

which one might take of the purpose of criminal punish

ment, the defendant’s conduct as the jury might have found

it at its worst on this record could support a death sen

tence consistent with civilized standards for the adminis

tration of criminal law. As the issue of penalty was sub

mitted to the jury in their unlimited discretion under

Florida procedure, their attention was directed to none

of the purposes of criminal punishment, nor to any aspect

or aspects of the defendant’s conduct. They were not in

vited to consider the extent of physical harm to the prose

20

cutrix, the moral heinousness of the defendant’s acts, his

susceptibility or lack of susceptibility to reformation, the

extent of the deterrent effect of killing the defendant “pour

decourager les autres.” Cf. Packer, Making the Punish

ment Fit the Crime, 77 Harv. L. Rev. 1071 (1964).

The absence of these or any other standards to guide a

Florida jury in determining whether a defendant should

live or die render the procedure violative of due process

under the rationale of Giacco v. Pennsylvania, —-— U.S.

------ , 34 U.S.L.W. 4099. There this Court struck down the

Pennsylvania statute allowing a jury to assess the costs

of a criminal proceeding on an acquitted defendant, be

cause of an absence of any standards on which the jury

could rationally base its decision. The Court said:

Certainly one of the basic purposes of the Due

Process Clause has always been to protect a person

against having the Government impose burdens upon

him except in accordance with the valid laws of the

land. Implicit in this constitutional safeguard is the

premise that the law must be one that carries an un

derstandable meaning with legal standards that courts

must enforce. 34 U.S.L.W. 4100.10

Under the Florida procedure the jurors were permitted

to choose between life and death upon conviction for any

reason, rational or irrational, or for no reason at all: at

a whim, a vague caprice or because of the color of peti

tioner’s skin if that did not please them. In making the

determination to impose the death sentence, they acted

10 Petitioner recognizes that the Court disclaimed any implications as

to the validity of established sentencing procedures. However, he submits

that the combination o f the evident intrusion of race as a factor in the

decision, the imposition of the extreme penalty, and the simultaneous

decision as to verdict and sentence (see Part III, infra) involved here

make the rational of Giacco particularly applicable.

21

wilfully and unreviewably, without standards and without

direction. Nothing assured that there would be the slight

est thread of connection between the sentence they exacted

and any reasonable justification for exacting it. Of. Skinner

v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535. A judgment so unconfined, so

essentially erratic, is per se cruel and unusual because it

is purposeless, lacking in any relationship by which its fit

ness to the offense, or to the offender or to any legitimate

social purpose may be tested. It is cruel not only because

it is extreme but because it is wanton; and unusual not

only because it is rare, but because the decision to remove

the defendant from the ordinary penological regime is ar

bitrary. To concede the complexity and interrelation of

sentencing goals, see Packer, supra, is no reason to sustain

a statute which ignores them all. It is futile to put for

ward justifications for a death so inflicted; there is no as

surance that the infliction responds to the justification or

will conform to it in operation. Inevitably under such a

sentencing regime, capital punishment in those few, arbi

trarily selected cases where it is applied both is “ ‘dispro-

portioned to the offenses charged’ ” and constitutes “ ‘un

necessary cruelty.’ ” Rudolph v. Alabama, supra, 375 U.S.

at 891.11

11 The United States Department of Justice has taken the following

position on continued imposition of the death penalty: “We favor the

abolition of the death penalty. Modern penology with its correctional and

rehabilitation skills affords greater protection to society than the death

penalty which is inconsistent with its goals. This Nation is too great in

its resources and too good in its purposes to engage in the light of present

understanding in the deliberate taking of human life as either a punish

ment or a deterrent to domestic crime.” Letter o f Deputy Attorney Gen

eral Ramsey Clark to the Honorable John L. McMillan, Chairman, Dis

trict of Columbia Committee, House of Representatives, July 23, 1965,

reported in New York Times, July 24, 1965, p. 1, col. 5.

22

III.

The Court Should Grant Certiorari to Decide Whether

Florida’ s Single Verdict Procedure Allowing the Jury

Which Determines Guilt Simultaneously to Fix Capital

Punishment fo r Rape Violates the Due Process Clause

o f the Fourteenth Amendment.

Under the procedure here employed by the State of

Florida, the jury which found petitioner guilty of rape was

required simultaneously to determine by its vote whether

he should be electrocuted or suffer imprisonment. Section

794.01, Florida Statutes, provides:

Whoever ravishes and carnally knows a female of the

age of ten years or more . . . shall be punished by

death, unless a majority of the jury in their verdict

recommend mercy, in which event punishment shall be

by imprisonment in the state prison for life, or for

any term of years within the discretion of the

judge. . . .

The Florida courts read this statute as requiring a single

verdict: a jury which finds guilt determines sentence with

out receiving further evidence or instruction, indeed, with

out even returning to the courtroom.

This procedure thrust upon petitioner, at the outset of

the trial, an intolerable choice: On the one hand, he could

decide not to testify, relying on his privilege under the

Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments. Malloy v. Hogan, 378

U.S. 1. But were he convicted, the jury would determine

his sentence with no knowledge whatsoever of his back

ground or personality or of any mitigating circumstances;

the jury would know none of the information which settled

views of penology consider indispensable to a rational sen

2 3

tencing decision. See Williams v. New York, 337 U.S. 241,

247-8. Indeed, the full consideration of the circumstances

of a crime may be necessary for “ the exercise of a sound

discretion” as required by due process. See, Williams v.

Oklahoma, 358 U.S. 576, 585.

On the other hand, the petitioner could at the outset of

the trial decide to take the stand, so that, in the event of

a guilty verdict, his jury could impose sentence based on

some quantum of information. But petitioner could thus

purchase a rational sentence only by surrender of his privi

lege against self-incrimination. The surrender could be

costly: the prosecution would be permitted to counter with

otherwise inadmissible evidence, e.g., evidence of bad char

acter, including unrelated crimes, Section 921.13, Florida

Statutes; Williams v. State, 110 So.2d 654, 661 (1959);

Davis v. State, 123 So.2d 703 (1960). Even were a jury

given cautionary instructions that such evidence should be

considered on the issue of sentence alone, the determina

tion of guilt would inevitably be prejudiced. As Judge

Learned Hand remarked, such cautionary instructions are

only “ the recommendation to the jury of a mental gym

nastic which is beyond, not only their powers, but any

body’s else.” See Nash v. United States, 54 F.2d 1006, 1007

(2d Cir. 1932), cert, denied, 285 U.S. 556.

In sum, the Florida single-verdict procedure here em

ployed requires a defendant to choose between a procedure

that threatens a fair trial on the issue of guilt and one

that detracts from a rational determination of the sentence.

See, A.L.I., M odel P en al C ode, Tent. Draft No. 9 (M a y

8, 1959), Comment to $201.6, at 74-76.

Other procedures employed by Florida in rape prosecu

tions exacerbate, rather than mitigate, the harshness of

the choice which a defendant is required to make. The jury

24

is given no instruction by the court on the manner in which

it should proceed in imposing sentence; it is left completely

without guidance. The juror’s oath offers no help: on the

subject of sentence, it is silent.12 Thus deterred by neither

instruction nor oath, the jury is free to vote its prejudices.

(The comparative record of death sentences imposed on

Negro and white defendants in rape cases suggests that

Florida juries make full use of this freedom.) Moreover,

if the jury is unable to decide by majority vote whether a

defendant shall live or die, the statute requires that he

die—only the vote of a “ majority” for mercy permits the

court to impose a jail sentence rather than death. Finally,

the sentence resulting from these procedures may not be

reviewed or modified on appeal; as long as it is within the

statute, review of the sentence is outside the jurisdiction

of any appellate court, Davis v. State, 123 So.2d 703 (1960).

Florida’s simultaneous submission of guilt and sentence

to a jury is much akin to New York’s former practice of

simultaneously submitting to a jury the two issues of the

voluntary nature of a confession and the guilt of the ac

cused. The former New York practice was, of course, struck

down by this Court in Jackson v. Denno, 378 IT.S. 368,

where the Court recognized the prejudice inevitable when

guilt and another issue are determined simultaneously:

. . . an accused may well be deterred from testifying

on the voluntariness issue when the jury is present

because of his vulnerability to impeachment by proof

of prior convictions and broad cross-examination. . . .

12 The oath administered to jurors in Florida reads, Section 913.11,

Florida Statutes Annotated:

“ You do solemnly swear (or affirm) that you will well and truly

try the issues between the State of Florida and the defendant whom

you shall have in charge and a true verdict render according to the

law and evidence, so help you God.”

2 5

Where this occurs the determination of voluntariness

is made upon less than all of the relevant evidence.

(378 U.S. 368, 389, n. 16.)

And see also, Whitus v. Balhcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir.

1964), holding that a Negro defendant may not constitu

tionally be required to choose between trial to a jury from

which Negroes are excluded and trial to a jury prejudiced

by defendant’s demand for Negro participation.

The single-verdict procedure not only thrusts upon the

defendant an intolerable choice between unfairnesses, but

it operates also to insure that, if found guilty, he will be

sentenced upon less than all pertinent information. For as

this Court recognized in Williams v. New York, 337 U.S.

241, 247-8, the exclusionary rules customary and appro

priate to trial of the issue of guilt will bar receipt of much

evidence properly to be considered on sentence.

As pointed out in the dissent below, a simple alternative

to the single-verdict procedure is available under the Flor

ida statutes: the issue of innocence or guilt could be tried

first, with all appropriate evidentiary safeguards observed.

Should the jury return a guilty verdict, it could then hear

all material pertinent to sentence, and then render a just,

informed determination.

For Florida to insist upon the single verdict under these

circumstances constitutes, petitioner submits, a denial to

petitioner of due process of law.

The procedure employed by Florida is used by many

states, and 18 U.S.C. §2113(e) permits federal juries to

impose the death penalty.13 The question of whether this

1318 U.S.C. §2113(e) : “Whoever, in committing any offense defined

in this section, or in avoiding or attempting to avoid apprehension for

the commission of such offense, or in freeing himself or attempting to

2 6

procedure violates the requirements of due process of law

has been raised often in the Third and Second Circuits

and in the District of Columbia Circuit. See, United

States ex rel. Rucker v. Myers, 311 F.2d 311 (3rd

Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 374 U.S. 844; United States

ex rel. Scoleri v. Bonmiller, 310 F.2d 720 (3rd Cir. 1962),

cert, denied, 374 U.S. 828; United States v. Curry, ------

F.2d ------ (2nd Cir. No. 29000, Dec. 22, 1965); Frady

v. United States, 348 F.2d 84 (D.C. Cir. 1965). Although

the procedure has been upheld, its validity was seriously

questioned in Frady and Curry, supra, and one jus

tice of the Supreme Court of Florida urged in the present

case that it violates constitutional standards; in all in

stances the case of Jackson v. Denno, supra, was cited.

Therefore, the issue of due process here presented is of

general importance and interest and warrants the grant of

certiorari. Moreover, in the present case the vice of the

Xrrocedure is demonstrated in its starkest form. Florida

allows the jury, unguided by any standards or instructions

and exercising a discretion not reviewable by any court, to

send a defendant to his death; it permits the jury to exer

cise freely the prejudices called up by the race of the de

fendant and the victim; and it does not even give the defen

dant an opportunity freely to present evidence to mitigate

the penalty.

free himself from arrest or confinement for such offense, kills any person,

or forces any person to accompany him without the consent of such per

son, shall be imprisoned not less than ten years, or punished by death if

the verdict of the jury shall so direct.”

However, federal courts have pointed out that having the jury decide

the sentence after rendering the verdict is fully consistent with §2113(e)

and is more compatible with Rule 32(a) of the Federal Rules of Criminal

Procedure. ( “ Before imposing sentence the court shall afford the defen

dant an opportunity to make a statement in his own behalf and to present

any information in mitigation of punishment.” ) United States v. Gurry

(2nd Cir. No. 29000, Dec. 22, 1965, Slip Opinion at 3560).

27

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons the petition for writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

L eroy D . Clark

M ic h ael M eltsner

C harles S teph en R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

T obias S im o n

H . W . D ixon

M aurice R osen

223 Southeast First Street

Miami 32, Florida

Attorneys for Petitioner

J ay H . T opkis

575 Madison Avenue

New York, New York

A n t h o n y G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Of Counsel

A P P E N D I X

O pinion o f the Suprem e Court o f Florida

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA

J u l y T erm , A. D. 1965

Case N o. 34,101

W illiam B e n ja m in Craig,

— vs.—

Appellant,

S tate of F lorida,

Appellee.

Opinion filed October 13, 1965

An Appeal from the Circuit Court for Leon County,

Ben C. Willis, Judge.

Howard W. Dixon, Tobias Simon, Maurice

Rosen, Jack Greenberg and Leroy D. Clark,

for Appellant.

Earl Faircloth, Attorney General, and George

R. Georgieff, Assistant Attorney General,

for Appellee.

P er C u ria m .

The appellant Craig was convicted of the crime of rape

and sentenced to pay the supreme penalty. The conviction

was affirmed on direct appeal. Craig v. State, 168 So. 2d

747.

Craig filed in the trial court a “Motion for reduction of

sentence from death to life.” Allegedly, he moved under

Section 921.24, Florida Statutes, which authorizes the cor

2a

rection of an illegal sentence in a criminal case. By his

motion, the appellant contended that:

(a) Sec. 794.01, Fla, Stat. which imposes the death sen

tence for the crime of rape, is violative of the

constitutional prohibition of cruel and unusual pun

ishment prescribed by the Eighth Amendment, Con

stitution of the United States.

(b) Sec. 794.01, supra, is patently unconstitutional be

cause it requires the trial jury simultaneously to

determine both guilt or innocence and the penalty.

(c) Sec. 794.01 is unconstitutional as applied to appel

lant. It is alleged that statistics reveal a pattern of

discrimination against negroes in the imposition of

the death sentence. Craig is a negro.

The Circuit Judge denied the Motion and expressly up

held the validity of Section 794.01, supra, against all

attacks leveled at it. Craig appeals.

We have considered the Motion as a collateral, post

conviction assault on a judgment of conviction within the

scope of our Criminal Procedure Rule No. 1. Regardless

of the title of the document, its purpose is to attack the

judgment on constitutional grounds. We, therefore, treat

appellant’s Motion as if it were filed under Rule 1, supra.

We take jurisdiction because the trial judge passed

directly on the validity of Section 794.01, supra, Article V,

Section 4(2), Florida Constitution. We do not construe

the instant judgment as one imposing the death penalty.

That was done by the original judgment of conviction

which was assaulted by the post conviction Motion. The

judgment here was final because the Circuit Judge had

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

3a

fully completed his judicial labor. We regard it as appeal-

able just as any other Rule 1 order is appealable. We have

held that such orders will be reviewed by this Court, or an

appropriate District Court, depending upon the content of

the order. Roy v. Wainwright, 151 So. 2d 825. Where, as

here, such an order passes directly on the validity of a

state statute it comes directly to the Supreme Court from

the trial court. We have said that the procedure is the

same as in habeas corpus. Mitchell v. Wainwright, 155

So. 2d 868. When the order does not bring the case within

our appellate jurisdiction, it should go to the proper Dis

trict Court.

On the merits we find that the Circuit Judge ruled cor

rectly in sustaining the validity of the statute against the

attack made upon it.

The judgment is affirmed.

T h o rn al , C.J., R oberts, D rew , O ’C onnell and Caldw ell ,

JJ., concur.

T h om as , J dissents.

E r v in , J dissents w ith op in ion .

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

E rvin , J., dissenting.

Appellant was convicted in the Circuit Court of Leon

County, Florida, of rape of a female over the age of ten

years and sentenced to death pursuant to §794.01, F.S.,

such sentence being mandatory there being no recommenda

tion of mercy by the jury.

He appealed his conviction to this Court and the judg

ment of conviction was affirmed. See Craig v. State, 168

So.2d 747.

4a

This is a second appeal to this Court. In this appeal it

appears the Appellant, as defendant, filed motion for re

duction of sentence from death to life imprisonment or

less with the Circuit Court of Leon County, pursuant to

§921.24, F.S., which provides a trial court at any time may

correct an illegal sentence. The motion was denied by the

Circuit Court. In its denial the Circuit Court upheld the

constitutionality of §794.01, F.S. It follows our jurisdic

tion is properly invoked by the Appeal under Section 4(2),

Article Y, State Constitution.

Appellant, a member of the Negro race, urges reversal

and assigns four reasons as follows:

No. 1. Imposition of the death penalty on Craig pursu

ant to Florida’s practice of racial discrimination in capital

punishment for rape denies him the equal protection of

the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

No. 2. Florida’s grant to juries and the Pardon Board

of unlimited, undirected and unreviewable discretion in

the imposition of the death penalty for rape violates the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

No. 3. Florida’s single verdict procedure allowing the

jury which determines guilt to fix capital punishment for

rape violates the due process clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

No. 4. Florida’s imposition of the death sentence for

rape where no life was taken and without consideration of

the aggravating or mitigating circumstances of the par

ticular offense subjects Appellant to cruel and unusual

punishment in violation of the Eighth Amendment as in

corporated in the Fourteenth Amendment.

By motion supported by affidavit, Appellant brought to

the attention of the trial court the following statistical

data which was not contradicted by the State:

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

5a

“ 6. In the 25-year period between January 1, 1940, and

December 31, 1964, inclusive of the case at bar, 285

persons have been convicted of the crime of rape in

the State of Florida. Of these, 152 have been Negroes,

132 have been White, and one was an Indian. Never

theless, only 6 Whites and 48 Negroes have been

sentenced to death; of these, only 1 White man has

died, while 29 Negroes have been electrocuted and 12

more await execution in Death Row at Florida State

Penitentiary at Raiford. . . . ”

Based on this data, Appellant contends under Reason

No. 1 that §794.01, F.S., which reads as follows:

“Rape and forcible carnal knowledge; penalty.—Who

ever ravishes and carnally knows a female of the age

of ten years or more, by force and against her will,

or unlawfully or carnally knows and abuses a female

child under the age of ten years, shall be punished

by death, unless a majority of the jury in their verdict

recommend mercy, in which event punishment shall

be by imprisonment in the state prison for life, or

for any term of years within the discretion of the

judge. It shall not be necessary to prove the actual

emission of seed, but the crime shall be deemed com

plete upon proof of penetration only.” ,

is unconstitutional because juries in the State of Florida

have systematically applied this statute mainly against

members of the Negro race. He argues the statute vio

lates the equal protection clause of the Federal Constitu

tion because the history and statistics of its application

by juries in the state disclose the infliction of death sen

tences in rape eases has been much greater upon Negroes

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

6a

than upon white persons. He cites in support of this con

tention Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954);

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963); Yick Wo

v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886); Tigner v. Texas, 310 U.S.

141 (1940); Fowler v. Rhode Island, 345 U.S. 67 (1953);

Hamilton v. Alabama, 376 U.S. 650 (1964); Oyler v. Boles,

368 U.S. 448 (1962); Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1

(1944); Arnold v. North Carolina, 376 U.S. 773 (1964) •

People v. Harris, 182 Cal.App.2d Supp. 837, 5 Cal. Reptr.

852; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1 (1948); Lombard v.

Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267 (1963); Strauder v. West Virginia,

100 U.S. 303 (1880); Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U.S. 584

(1958); Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475 (1954); McLaugh

lin v. Florida, 84 S.Ct. 1693 (1964); Swain v. Alabama,

33 U.S. L. Week 4231 (1965); Omaya v. California, 332

U.S. 633 (1948); Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).

In support of reason No. 2, Appellant contends that the

authority given to juries to make recommendations of

mercy as to death sentences for rape, amounts to an un

limited, undirected and unreviewable discretion violation

of due process of law. The Appellant contends no stand

ards are prescribed for the exercise of this authority and

that the same is exercised arbitrarily and irrationally by

juries. He cites in support Herndon v. Lowry, 301 U.S.

242, 263 (1937); Smith v. Cahoon, 283 U.S. 553 (1931);

Lovell v. Griffin, 303 U.S. 444 (1938); Joseph Burstyn,

Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495, 505 (1952).

As to reason No. 3, Appellant contends the single ver

dict phase procedure now followed in our state authorizing

juries which determine guilt simultaneously to fix capital

punishment for rape violates due process of law in that

this procedure tends to deny a defendant a fair trial. Ap

pellant calls attention that pursuant to Florida procedure

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

a jury ordinarily makes its life-death choice simply on the

evidence presented on the issue of guilt, while modern

concepts individualizing punishment have made it all the

more essential that a sentencing judge or jury not be

denied a separate opportunity to receive pertinent infor

mation, including reports from probation and parole au

thorities relative the degree of punishment, unrestrained

by rigid adherence to restrictive rules of evidence prop

erly applicable to the trial of the issue of guilt; and that

it is an imperative condition of rational sentencing- choice

that the sentencer consider more information about the

individual defendant than is likely to be forthcoming on

the trial of the guilt issue. In Davis v. State (Fla.), 123

So.2d 703, in headnotes 9-11 this Court apparently agrees

to the modern concept of individualized punishment.

Appellant also points out that if a defendant seeks to

present to the jury pertinent background evidence to in

form its sentencing choice, Florida procedure permits the

prosecution to counter with evidence of defendant’s bad

character, including evidence of unrelated crimes, citing

§921.13, F .S .; Williams v. State, 110 So.2d. 654, 661 (Fla.

1959); Davis v. State, 123 So.2d 703 (Fla. 1960); Whitney

v. Cochran, 152 So.2d 727 (Fla. 1963); Nations v. State,

145 So.2d 259 (DCA2nd 1962). Appellant contends that

the possibility that background information may be strong

ly prejudicial as to issue of his guilt forces a defendant

to a “ choice between a method which threatens the fair

ness of the trial of guilt or innocence and one which de

tracts from the rationality of the determination of the

sentence.”

Appellant contends the two stage procedure now em

ployed in a number of states and in military courts martial

8 a

should be judicially adopted in Florida to insure due

process and avoid effects prejudicial to a fair trial.

Appellant refers to the fact that a defendant usually

has the right of allocution; that is, the right to express

without restraint to his sentencer why judgment or sen

tence should not be meted out to him but he contends this

right under present Florida procedure in rape cases is

not freely given to him without possible jeopardy, to be

heard by the jury on the question of punishment. Appel

lant also points out that under existing procedure if the

defendant in a rape case takes the stand he is subject to

incriminating cross examination even though he limits his

statement to the issue of a mercy recommendation.

Concerning reason No. 4 Appellant contends that a death

sentence in a rape case without due consideration of ag

gravating or mitigating circumstances subjects a defend

ant to cruel and unusual punishment, and such a sentence

is inherently cruel and unusual under modern concepts,

citing dissenting opinion in Rudolph v. Alabama, 84 S.Ct.

155 (1963); he also cites Weems v. United States, 217 U.S.

349 (1910), and Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958). In

this portion of his argument Appellant recurs to the

statistical disproportion of death sentences meted Negro

males compared to those imposed upon white males in

rape cases, contending this disparity amounts to cruel and

unusual punishment for one class of citizens not visited

upon other citizens.

The constitutionality vel non of §794.01, F.S., is sus

tained by the overwhelming weight of authority.

Sentence within statutory limits, no matter how harsh

and severe, is not cruel and unusual punishment within

the constitutional provision; 9 Fla. Jur., Criminal Law,

Opinion o f the Suprem e Court o f F lorida

9a

§269, p. 302, citing Brown v. State (1943), 152 Fla. 853,

23 So.2d 458.

“Punishment of death is not in violation of the consti

tutional prohibition of cruel and unusual punishment un

less it is so inflicted that it involves lingering death, tor

ture, or such practices as disgraced the civilization of

former ages.” 9 Fla. Jur., Criminal Law, §271, p. 304.

See also, 30 A.L.R. 1452; Ferguson v. State (1925), 90

Fla. 105, 105 So. 840, cert, denied 273 U.S. 663, 71 L.Ed.

828, 47 S.Ct. 454.

“ The punishment for both forcible and statutory rape

is death, unless a majority of the jury in their verdict

recommend mercy, in which event the punishment is