Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Appendix Vol. 1

Public Court Documents

July 16, 1969 - July 22, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Appendix Vol. 1, 1969. 5cf839ff-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/229ae690-39df-4c7a-8b0f-59a6631613d9/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-appendix-vol-1. Accessed February 01, 2026.

Copied!

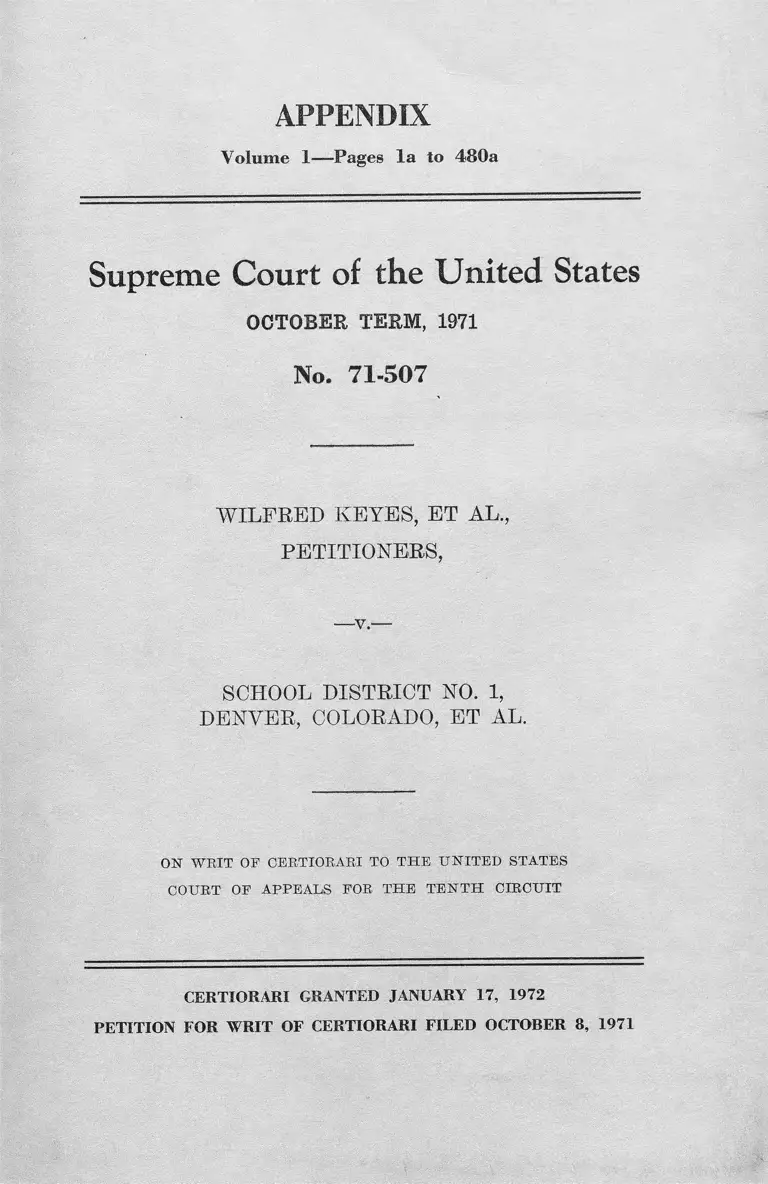

APPENDIX

Volume 1— Pages l a to 480a

Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

No. 71-507

WILFRED KEYES, ET AL.,

PETITIONERS,

—v.—

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1,

DENVER, COLORADO, ET AL.

ON W R IT OF C ERTIO RA RI TO T H E U N IT E D STA TES

CO U RT OF A PPE A L S FO R T H E T E N T H C IR C U IT

CERTIORARI GRANTED JANUARY 17, 1972

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED OCTOBER 8, 1971

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Volume I

PA G E

Docket Entries —....... ................................................. la

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and Declara

tory Judgment........... ..... ..................................... . 2a

Exhibits annexed to Complaint:

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 3—Resolution 1520 ....... 42a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 4—Resolution 1524 ............. 49a

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 5-—Resolution 1531 ............. 60a

Motion for Preliminary Injunction.............. 71a

Answer of Defendants Amesse, Noel and Voorhees,

J r ............................................................................. 73a

Hearing on Preliminary Injunction July 16-22, 1969 85a

T estim ony

(M in u t e s oe H earing on P relim inary I n ju n c t io n

J uly 16-22, 1969)

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

Rachel B. Noel—

Direct ............................................... 85a

Redirect .......... 104a

A. Edgar Benton—

Direct .................. 108a

Cross ................ 121a

Redirect .............. 123a

11

Paul 0. Klite—

Direct ....... ................

Yoir Dire ...................

Cross ...... ...................

Redirect ...... .............

James D. Voorhees, Jr.—

Direct ........................

George E. Bardwell—

Direct ........................

Voir Dire ......... .........

Cross ..........................

Robert D. Gilberts—

Direct ........................

Cross ..........................

Redirect .....................

Defendants’ Witnesses:

Gilbert Cruter—

Direct ........................

Voir Dire ..................

Cross ..........................

Howard L. Jolm son-

Direct ...... .................

Cross .........................

Recross ......................

Robert Gilberts—

Direct ........................

Cross .........................

Redirect ....................

Recross ......................

PAGE

126a, 133a

..... 132a

..... 139a

..... 142a

143a

151a,191a

..... 185a

..... 193a

227a

252a

255a

208a, 214a

..... 213a

..... 216a

256a

302a

369a

376a

393a

408a

414a

Richard Koeppe—

Direct ......... ........... ............... ........... .....419a, 437a

Voir Dire ________ ____ ____ _____ ___ 436a

Cross ........................................ ..................... 438a

Preliminary Injunction ............. ................................. 452a

Memorandum Opinion and Order of District Court 454a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated August 5, 1969 .... 455a

Supplemental Findings, Conclusions and Temporary

Injunction by District Court ....... .......................... 458a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated August 27, 1969 459a

Order ...... ........... ................ .......................... ............... 463a

Opinion by Brennan, J. on Application for Vacating

of Stay .......... ................................. .................... 464a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated September 15,

1969 ........... ..........- .................................................. 467a

Answer ................ ....................................................... 470a

Memorandum Opinion and O rder....... .................. 475a

I l l

PAGE

Volume 2

(M in u tes oe T rial on M erits ,

F ebruary 2-20, 1970)

PAGE

Minutes of Trial on Merits, February 2-20, 1970 .... 481a

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

Paul Klite—

Direct ..................................481a, 493a, 502a, 523a,

530a, 533a, 537a

Voir Dire ..................................... 491a, 502a, 522a,

528a, 532a, 536a

Cross ............................................................. 564a

Redirect ....................................................... 621a

Lorenzo Traylor—

Direct ........................................................... 579a

Cross ............................................................. 607a

Redirect ........................................................ 621a

Gerald P. Cavanaugh—

Direct ...................................... 626a

Cross ....................................................... ...... 646a

Redirect ........................................................ 652a

Recross .................................................. 655a

Mary Morton—

Direct ........................................................... 656a

Cross .............................. ............................... 660a

Marlene Chambers—

Direct ..................................................... 665a, 671a

Voir Dire ...................................................... 670a

Cross ............................................................. 676a

Redirect ........................................................ 681a

Recross ......................................................... 682a

V

Palicia L ew is-

Direct ................................. 684a

Cross .................................... 693a

Redirect ................................ 696a

Recross ................ 696a

Mildred Biddick—

Direct ........................................................... 697a

PA G E

George E. Bardwell-

Direct .......................... 700a, 703a, 707a, 716a, 727a,

757a, 769a, 790a, 798a

Voir Dire .................... ........702a, 707a, 715a, 726a,

755a,767a, 786a,791a

Cross .......................................................... 800a

Redirect ........................................................ 818a

George L. Brown, J r . -

Direct ........................................... 857a

Dr. Dan Dodson—

Direct ...................................................... 1469a

Cross ............................................................. 1493a

Defendants’ Witnesses:

Robert L. Hedley—

Direct .................

Voir Dire ............

Lois Heath Johnson—

Direct .................

Cross ...................

Redirect ..............

Recross ............

,820a, 834a

...... 833a

..... 893a

...... 922a

..... 955a

..... 956a

YX

Palmer L. Burch—

Direct ........................................................... 963a

Cross ............................................................. 978a

Redirect ...... ........................................1023a, 1030a

Recross .......................................................... 1025a

PA G E

Volume 3

William Berge-—

Direct ..................... 1033a

Cross .................................................... -....... 1051a

James C. Perrill—

Direct ..........................................................- 1076a

Cross ............................................................. 1083a

Redirect ........................................................ 1100a

Recross .................................................. 1101a

John E. Temple—

Direct ....................................... 1101a, 1115a, 1129a

Voir Dire .............................................1112a, 1128a

Cross - ....................................... ..............-.... 1131a

Jean McLaughlin—

Direct .............................................- -.......- 1131a

Cross ........... -............................ -..................- 1146a

Redirect ....................................................... - 1150a

Dr. Harold A. Stetzler—-

Direct .................................................. - - 1150a

Cross ............................................................. 1189a

Redirect ........................................................ 1210a

Lidell M. Thomas—

Direct .......................................................— 1214a

Cross ............................................................. 1239a

Redirect .........................................- -....... 1252a

Recross ......................................................... 1253a

Charles Armstrong—

Direct ........................................................... 1254a

Cross ............................................................. 1289a

Kenneth Oberholtzer—

Direct ........................................................... 1299a

Cross ............................................................. 1393a

Redirect ........................................................ 1463a

Memorandum Opinion and Order of District Court .. 1514a

V ll

PA G E

Volume 4

(M in u t e s of H eaeing on R e l ie f , M ay 11-14, 1970)

H e a r in g on R elie f, M ay 11-19, 1970 ...... 1515a

Plaintiffs’ Witnesses:

James Coleman—

Direct ........ ......................................... 1516a, 1526a

Voir Dire ...................................................... 1520a

Cross ....... 1552a

Redirect - ..... 1561a

Neal Sullivan—

Direct ........................................................... 1562a

Cross ...... 1588a

Redirect .............. 1598a

George Bar dwell—

Direct .......................... 1602a

Cross .................................................. 1664a

Redirect ........................................................ 1683a

William Smith—

Direct ........................................................... 1688a

Cross ..................................................... 1698a

vm

Robert O’R eilly-

Direct .................................................. 1910a,1925a

Yoir Dire ...................................................... 1920a

Cross .......... -................................................. 1942a

Redirect ............ 1968a

Defendants’ Witnesses:

Robert D. Gilberts—

Direct ............................ 1706a

Cross ................................................ -......... - 1763a

Redirect ...................................................... 1834a

Recross .............................. 1842a

James D. Ward—

Direct .......... 1844a

Cross .....- ...................................................... 1868a

George Morrison, Jr.—

Direct ........................................................... 1874a

Cross .................. 1892a

Redirect ........................................................ 1896a

Albert C. Reamer—

Direct .......... 1897a

Cross ............................................................ 1905a

Decision Re Plan or Remedy by District Court ......... 1969a

Final Decree and Judgment.................. 1970a

Defendants’ Notice of Appeal .................................... 1978a

Plaintiffs’ Notice of Appeal......... .............. 1979a

PA G E

Decision by Court of Appeals on Motion for Stay,

etc............................................................................... 1981a

IX

Decision by U. S. Supreme Court on Stay, etc.......... 1984a

Opinion of Court of Appeals dated June 11, 1971 ..... 1985a

Judgment of Court of Appeals dated June 11, 1971 .. 1985a

Decision by Court of Appeals for “Clarification of

Opinion” ............ ............ .............................. ..... ..... 1986a

Order Granting Certiorari............................... .......... 1988a

I ndex to E x h ib its A ppears i n E x h ib it V olume

PAGE

c f v n , H o c K i iT * " f\€PJS/\ L - 7 , ;

UNITED STATES I ' I S T aICT ■CO-’l t l ' ̂ ‘" v " f

Jury demand date:

i \ C. Form No. 105 Rev. f . 0

* i

TITL‘D OF CASE

t c n: t c A , /

ATTORNEYS ' * *•’ ‘ W /

6 - 1 9 - 6 9 6 / 8 / 7 0

UII.FKFD KEiF.S, i n d i v i d u a l l _ x ?>rtd o n :b e h a l f o f CHRISTI For plaintiff:

KEYJSSj a m in o r ; CHRISTINE A. COLLEY, i n d i v i d u a l l y and ■BARNES & JENSEN

on b e h a l f o f KRIS M. COLLEY and MARX A. WILLIAMS, C r a i g S . B a r n e s 7

m i n o r s ; IRMA J . JENNINGS, i n d i v i d u a l l y and on b e h a l f 2 4 3-0--Soufch-Un-i v-er-s-i-ty—B-l-vd. , / f j f ' J :.

o f ’RHONDA 0. JENNINGS, a m i n o r , ROBERTA R. WADE, i n - D e n v e r , C o l o r a d o 89-2-1-0 S y / ' J ' La-.

d i v i d u a l l v and on b e h a l f o f GREGORY L, UA.DE.a m in o r ; T e l : - 7 -4 4 - 6 4 5 5 - ,??J> •‘Z Y Y Z / .

EDWARD J . STARKS, J R . , i n d i v i d u a l l y and on b e h a l f o f

DENISE MICHELLE STARKSJ a m i n o r ; JOSEPHINE PEREZ, i n - G o r d o n G. G r e i n e r 7 \

d i v i d u a l l v and on b e h a l f o f CARLOS A. PEREZ, SHEILA R 5 0 0 E c f u i t a b l e B u i l d i n g

PEREZ and TERRY J . PEREZ, . m i n o r s ; MAXINE M. BECKER D e n v e r , C o l o r a d o 8 0 2 0 2 ________ ______

i n d i v i d u a l l y and on b e h a l f o f DINAH L. BECKER, a mine: ; T e l : 2 9 2 - 9 2 0 0

EUGENE R. WEINER, i n d i v i d u a l l y and on b e h a l f o f

SARAH S. WEINER, a m in o r . J a c k G r e e n b e r g Sc J a m e s M. N a f c r i t t . __J T1

\ C o n r a d K. H a r p e r ..... ........ . ....

1 0 Co l u m b u s _ C i r c l e . , ________________ 1_________

vs New York , . . . . .New..York._. l0 0 1 9_._A__ 1__________ _

. SCHOOL DISTRICT NUMBER ONE, DENVER, COLORADO; ( c o n t . o n n e x t p a g e )

. THE BOARD O? EDUCATION, SCHOOL DISTRICT NUMBER ONE,

DENVER, COLORADO; 3. WILLIAM C. BERGE, i n d i v i d u a l l y For defendant: - t

and a s P r e s i d e n t , Board o f E d u c a t i o n , Schoo l D i s t r i < •t /Vf'b / A ' - K . - ' A\

Number One, Denver , C o lo r a d o ; 4 . STEPHEN J , KNIGHT, y i / / ST” ■ S r fV-v-’ >'v / /» ," i /- •

- ' JR . , i n d i v i d u a l l y and a s Vice P r e s i d e n t , Board o f . >)i: -uy-- v-v,-.. .

E d u c a t i o n , School D i s t r i c t Number One, D e n v e r ,C o l o - f p , p - {jc j ->

r a d o ; 5 . JAMES C. PERRILL, 6. FRANK K . -S0UTHW0RTH,

. JOHN It. AMESSE, 8. JAMES D. V00RHEES, J R , , and b x ALL DENIS. EXCEPT V onrhnes , Amesae & Kps

RACHEL B. NOEL, i n d i v i d u a l l y and a s members , Board ft • Mm. K. b i s __ _____

o f E d u c a t i o n , School D i s t r i c t Number One, Denver , ______ Dvr-Club Bldg-.-...... ......

C o l o r a d o ; 1C. ROBERT D. GILBERTS, i n d i v i d u a l l y and ' Denver P 'Coloy: ;244r5475 . .on.a>_./.o<q>__________

a s S u p e r i n t e n d e n t o f S c h o o l s , School D i s t r i c t

Number One, Denver , C o lo r a d o , A ttys.. . f o r 1 ater_vexii u g.. H e f t s . .Y T L iA ts jx c _

_A 1 lec[ed violation of civil rights. Action

for dec1aratorv judgments on whether the

school board_ is donying s'orne children____

equal educational opportunities.

Charlfts_E ._Brega _and_Rober £-4SU-- Sfi;

2301 F irst National Dank Building

Denver, Colorado 30202 292-9000^

NAME OK

. RECEIPT NO. REG. DISD.

J .£ „ 7 0

0 .0

_____ ^ ~ v -- .y

?}■ d 7 : '7 .~ ,0 . . . jY '7 7

> o

/* _____

A ; -A / m - h b l /

Y f / y - ' L Y Z

.... . 7 O L —

....... / :

...;___ B r A t . /xJ> . 4 ,

____Z .. ,» ««

‘. — 6 .

J f

F

r-

Wilfred "eyes, et al

vs

School District Number One, et a1

DATE

9 6 9

•19

5/27 _v/_

7/3 MOTION o f P l t f s . f o r Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g Ord e r

7/1.

7/11

7/14

/ jo -kici-rk-k

P R O C E E D IN G S

COMPLAINT

Summons issued

Motion for Prelininary Injunction

H e a r in g s Pre 1 rm ina ry I n j u n c t i o n . , . O r . d c re d : B o t h S i d es to_._s.ubmit 1 i s.t o f .

Exh i b i t s & ■wi t n 2 s,ses w l t h i n 10 d ays from t h i s d a t 1 fegk—tO_J&&t_Jlear ing_

d a t e In J u l y , e od 6 / 3 0 / 6 9

innrine; fUTDl he Tempor a r y Re s t r a i n in g Orde r . . .Arguments: oLJlQ.urifieJL.

M a t t e r c o n t i n u ed t o l a t c -r t im e . Re c g a s . eod..7/8./_69------------------------

P r e l i n i n a r y L i s t o f E x h i b i t s .

. .Ordered t_

PI t f £

R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n gs h e l d on 6 / 27 /69

Date Order or

Judgment Noted

-H .

M a rsh a l* s r e tu r n on S e r v ic e by s e r v in g W. C. Se rg e .Pr e.sidc.nt..._BQar.cL o f —E ducation .,

Sch o o l D is t #1 & P e rso n a l l y S t _ep.li en_ J . Kn i c j i t.,.. J r _ J arm s_iL—P e e r i l l »_Er ank. X .

____Southw or t h , Jo h n H. / m a sse . J a n e s D. Vo o rh e e s , J r . . Rac.he.l_R—No e l a n , L R o b art...-

D, G i l b e r t s , Duka W. D u n b a r , A t t y ._Genciral^Q.r_&tr,t2L_.Qf_CQla..on_j6/20/.69------------

MOTION o f Ra f t s , f o r E n l a rg e m e n t—QlLTisie__ _ _____________________________________________

.Bearii^i„(vTD0_0xdMrM^.D2l:ts^Juo.ti.csx..lo^XnLargBTfiant_o.hXim-e_w±thin_^whiclrTQ-Tile

___a n s w e r s i s Grani.e.cL_^_____________________

7 /15

7 / 16

S igne d (BED) 0 r der.JEor_Enlarg&g:an£-Of-

___a n sw e r s or.. o_tharKls .a_plead—-e.o.d_ZVl4/63_

P l t f s , P r e l i m i n a r y L i s t o f Wit n e s s es______

_D a f t s _h a_v.e_nn.til_7V.23-/ 6S._tO- T i l e_

P l t f s . P r e l i m i n a r y Memo, o f Law.

C e r t , o f S e r v i c e . _________________________ _______________________________________

ANSWER OR nSPTS. .TORN H. AMKSSF., RAfSLFJ^^, JjQEX&-J^.lSS__D —JVOOMEEX—JR .

o f S e r v i c e . ___ _ _____________ _____________________________

,Cert

P l t f s . P roposed F i n d i n g s o f F a c t

7-1.7

7 / 18

7 / 21

7/22

T r i a l n t o C our t 1 s t D a y . . , Wi t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . r e c e s s , eod 7 / l 7 ./6i3_

D efe n d a n t s ' P r e l i r a in a r y Li s t o f Ex h i b i t s

D e f e n d a n ts ' Pr e l im in a r y Li s t ..o f W itne; ; e s

S i g n ed (VIED) Order f o r Pro d u c t i o n o f D ocuT ';.en t^ .._ead ,llZ lB /.6 j_________________

T r i a l t o Co u r t fWED ) . . . 2 n d D a y . W i t n e s s e s . J_JEx.h.ibit.S^-r&C.es.S--t.Q V / l ft/JaiL

7 /2 l*'<v*

7 / 2 2

7 /28_

7/29

Tr i a l t o C ou r t (NED). . . 3 rd Day. . .Wi t n e s s e s . . .Exhlh.it.s.^jcec.e.5.s._tQ—7 - / 2 l / M __________

T r i a l t o Cou r t fWBDl. . . 4 t h D ay . . .Wit n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s si^ntls_sllbm i.tJ:fc.d-£t

t a k e n u n d e r a d v i s e m e n t . eod 7 /23 /69 .

D e f t s . P r e l i r a i n a r y Me-mo . o f Law ___

De f t s ._P r o p o s ed Conc lu s io n " , o f Law

D e f ts - Amendments t o P r e l i m i n a r y Findings_oJ:.-Pa,-Cl_&L_S-naplercjaiit a l_ P r o p o s e d _ E lu d in g

o f F a c t ____________________ _______________________________ ___________ _____________ ______ ____

S t i p u l a t i o n o f F a c t s as. t o P a r t i e s .to„..the_Cfl.s.e.__________ —---------------------------------------

TrLy._To...CoAi.rt^X795D) „̂.„.3.Lh-DayJ_._,Tindlngs_ o..f.T.cact_A.TOjicliislonr.„O.X.La.v;,"5_P.l.tfs

M otion f o r Pi:.elirdng,ry_Iti.iunc_tj.p.n—shQ.uld.Jb.e_&-hexfib-y_ia_GRAKTEIl— -Or.derod.

P . l t f . s c o u n s e l t o p r e p a r e an o r d e r ___Order& d.t-JD a£ts^-H Q t.ion._fo.c_a_stay.„is_

JSRANIE0_( 10...Ray ..S.t.6tyX—.. Recs s. s —.aod..7123/.6 2 -

Copy o f O f f i c i a l ' T r a n s c r i p t Volume V o f p r o c e e d ings h e l d o n , 7 / 2 2 / 6 9 _____ _____ ___

O b j e c t l o n s t o Form__o f P r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i on______________ ________________ __________

S t i p u l a t i o n f o r e x t e n s i o n of t ime f o r d e f t s ._t o f i l e p l e a d ings. , to. ..& . i n c l u d i n g ,

8 / 1 4 / 6 9 . ....... ........ __ ~ ~ ____~_______ J__________________ _____ - _______ _____

Signcd (WEI)) Ordor f o r En l a r g e m e n t o f T ime , g r a n t i ne, n e x t above , s t i puj._afci.Qn_.

. , ~ -f f~2S/(>9. ______ ____________________________ _______ ____ — .------—

P l t f s . Su p p le m e n ta ly L i s t o f E x h i b i t s . _ a nd Wi t n e s s e ;

Defts..,_S.up.p_l.eiBenfhry— L i s t ..of E xh ih i t s

S i g n ed (WED) p r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n , t h a t . temporary. , i n j u n c t i o n . .i:L.Rr.nnfeel £t_.tp. .

__ _ c o n t i n u e d u r i n g t h e pendency o f t l . i s su i t &, u n t i l . a c t i o n j.s._tric.d ..oft. i t s „ t n n r i .s_

- J n e f t Z ^ r a n t e d 10' days - from. I Z £ t e r - 7 '23 fb 9 -f o r • n^ e a l « r e view, , .pod. .? / 2 9 / 6 9

NOTICE OF APPEAL

8 9 5 0 .DO (com

KT AL" WILFRED KEE.8%

VS.

SCHOOL DISTRICT NUMBER ONE, ET AL

v c n o Rev. Civil p o c k e t C on tinuation ' ‘ - @

date

1969

..... ' PROCEEDINGS D ate Order or

Judgment Notei

7/31 A p p l i c a t i o n f o r S ta y o f P r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n f i l e d by a l l D e f t s . except . James

D. Voorhees , J r . , John H. Amesse, and P,achel B. N o e l ,

.H ea r ing (WED) A p p l i c a t i o n f o r S t a y . , .O r d e re d : Aon l i c e t i o n i s DENTED. . . Tcrnoorarv

s t a y i s GRANTED.. . W r i t t e n o r d e r t o f o l l o w , eod 7 / 3 1 / 6 9

871, - Si.ened (WED) Memorandum O p i n i o n &. O r d e r , t h a t t h e M ot ion f o r p r e l i m i n a r y i n i u n c -

t i o n i.s G r a n te d , eod 8 / 4 / 6 9

8 /6 P l a i n t i f f s MOTION f o r H e a r i n g on Remand and R e q u e s t f o r Immedia te H e a r in g and

-Jp f o r Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g O r d e r .

'T IT MANDATE. . . 10 th C i r c u i t . . .Remanding c a s e t o Judge D o v l e .

876 H e a r in g WED on M ot ion f o r H e a r i n g on Remand and f o r ’ Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g o r d e r .

M a t t e r c o n t i n u e d to 8 /7

8/7 H e a r i n g (WED) M ot ion on Remand f o r Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g O rd e r GRANTED u n t i l

8 :0 0 a .in. 8 / 1 5 / 6 9 o r f u r t h e r o r d e r o f C o u r t . M a t t e r on Remand t a k e n u nde r

a d v i s e m e n t .

S inned (WED) Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g O r d e r . S igned 1 2 : 2 0 p . n .

!1

7T;t

| 03 Mo t ion o f d e f t s t o d i s m i s s . . . C e r t o f M a i l i n g

- i i D e f e n d a n t s ' B r i e f on Remand

8-14 Copy r e p o r t e r ' s t r a n s c r i p t . . . p r o c e e d i n g s on 8 - 7 - 5 9

Signed (WED) S u p p le m e n ta l F i n d i n g s , C o n c l u s i o n s and Temporary I n j u n c t i o n and

O p in ion as t o A p p l i c a b i l i t y o f S e c t i o n 4 0 7 ( a ) o f fie. C i v i l R i g h t s Act o f 1964

eod 8 -1 4 -6 9

-18 NOTICE OF APPEAL ■

Appearance Bond on Appeal

A p p l i c a t i o n o f d e f t s . f o r S t a y o f P r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n

.Hearing; .(TfSD) 1 - I o i i n n f o r S t a y . . . O r d e r e d M o t i o n . f o r S t a y i s d e n i e d

3 - 1 9 R e c e i p t f r o m U . S . C o u r t o f A p p e a l s f o r r e c o r d o n a p p e a l

8/25 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s h e l d on 8 / 7 / 6 9

Memo, i n S u p p o r t o f M otion to D i sm is s f i l e d by D e f t s .

3 /26 Deposit ion o f R o b e r t Dubois G i l b e r t s .

E x h i b i t s on n e x t above d e p o s i t i o n A ,7}

9/5 P l t f s . Memo. Oppos ing D e f t s . M otion t o D i s m i s s . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

9 /10 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s h e l d on 8 / 6 / 6 9

Reply Memo, i n S u p p o r t o f Motion to D i s m i s s . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

9/11 H e a r in g (WED) M ot ion t o D i s m i s s . . . O r d e r e d : M ot ion i s Denied , P l t f c o u n s e l to p rep : r c

an O r d e r . . . O r d e r e d : D i s c o v e r y to be co m p le te d i n 60 d a y s , eod 9 / 1 5 /6 9 /-•

9/2 6 Order L e t t i n g P r e T r i a l C o n f e re n c e f o r 1 1 / 4 /6 9

9-29 S t i p u l a t i o n f o r e x t e n s i o n o f t i m e .

S ig n e d (USD) O rde re d t h a t d e f e n d a n t s h a v e u n t i l 1 0 -6 -69 t o f i l e an answer h e r e i n

E n t r y o f A ppe a ranc e o f K e nne th H. Wonraood f o r d e f e n d a n t s . T

. 1 0 / 3 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t , D e f t s Motion, t o D i s m i s s , o f p r o c e e d i n g s h e l d on fl 9 / 1 1 /6 9

10/6

_JBp:pne:At;xd,.s:<72x2KS$$SOTi:x?5%X52;:s’;'ar.i4i;n^3xh<2fchnn55x-872v(f;.9

ANSWER o f a l l d e f t s . e x c e p t D e f t s . 7 , 8 & 9 . . . C e r t , o f M a i l i n g

*9/15 C e r t , copy from C o u r t o f A n n e a l s t h a t t h e M ot ion i s Denied & f u r t h e r p r o c e e d i n g s

on t h e a p p e a l a r e h e l d i n ab e y an c e u n t i l f u r t h e r o r d e r o f C o u r t . u s d

10/17

—JL0/JL7

W r i t t e n I n t e r r o g s . by C e r t a i n D e f t s t o be Answered by P l t f s . y

Signed (WED) Memorandum O p i n i o n and O rde r t h a t m o t i o n s t o d i s m i s s f o r f a i l u r e to.

______D e n i e d . . . D e f t . h ave 15 Days from 9 / 1 1 / 6 9 "to f i l e Answer.

....10/1.7.

Signed 1 0 / 1 6 / 6 9 . eod 1 0 /2 0 /6 9

P l t f s . F i r s t SAt o f I n t e r r o g a . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

__ 1.07 .JFJLtfs ^_Eixst_H.y.t.iop f o r P r o d u c t i o n o f Documents . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e ,

MOTION t o I n t e r v e n e a s D e f t s .

.TENDEREDANSWER AN D.j - R O S S CLAIM CF TNTHRVENORS

_10/21... —C o n f e s s i o n .o f _ A1 l _ l j a f t o . e x c e p t D e f t s . 7, 8 6 9 o f Motion t o I n t e r v e n e . . .C e r t .M a i r r

-1.0724__ C o p t ._o f K a i l ! e g Mot ion t o I n t e r v e n e & T ende red Answ er . HJ2L. f '

......... . ... 'V 1 r '?

SCHOOL DISTRICT NUMBER ONE,

DENVER, • COLORADO, KT A L . ,

v s .

PA T H

1969

PR O C EE D IN G S

10/29

10/30

MOTIONS o f Al l D e f t s . E xc e p t . 7 , 8 & 9.. .f .Qr_Or:ders_Pr.otGCting_De£tS- ,- . iP- the.JEro.duct ion

_____ o f Dogtmants t . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e . ____________________________________ ________________

D e f t s . o f a l l L e f t s . Exc e p t 7 , 8 & 9 t o I n t e r r o g a t o r i e s . . . C e r t . _Ql_SexvJ.ee.,________

P l t f s . P r e l i m i n a r.y_Lis_t_ o JLJ:tilxn.e_s.£.es_ft_Exhibits_________________________________ ________

P l t f s . Ob j e c t i o n s t o "W r i t t e n In te rm gs^_by_C ex ta in_ . .D a i : t s__ta_b.e_A.nawered.by_Pl t£ .

__ . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e . ________________ ________ _________ :___________________ ;____________

11/3

P l t f s . Second MOTON f o r P r o d u c t io n o f Do cumen t s ,

Pltfs.,_5_e.c<md_Sxt_o.f_lntexxQg.ai:oxiea._to._D.afi:s.^.-....C.e.xtu_QLf_S.e.rvjj£fe.

MOTION o f D e f t s . e x c e p t 7, 8 & 9 t o Vac a t e P re T r i a l & T r i a l S e t t i ngs . . Cer t . _o f

______ Serv.i c e .____________________________________________________________ ______ :______________

P l t f s . Th i rd Mo t i o n f o r P r o d u c t i on o f Documents

P_Ltfs^_Anawsr^_t.Q_lTitexx<iifS^_^JTexf^.o.f_S2Xvlce.

P i t fs_,_ I n t e r r o g s . , t o l n t e r v e n o x Ce;c

P l t f s . R e v i s e d L i s t o f E x h i b i t s

■Ce r t , o f Se r v i c e .

of Servi

C e r t , o f S e r v i c e

ce,_

1 1 / 4 __ i S t i p u l a t i o n t h a t P I t f s . w i l l r.ot o b j e c t t o I n t e r v e n t i o n

Jl 1 / 3 * * * .Me.rao . i n . .Si iD.o.ox. .Obj-.eot loxr ,_t£>_J[atexx£g8_._________ _—

11/4

11/3

Date Order .

Judgment Kf

11 /5 .

11713

11/13

11/14

1.1 / 1 7__

11/18

11/20

11/2 J

11/25

11/28

D e f t s _cxc e p t Voor h e e s , J r . Ain e s s e & N o e l , Answers t o I n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t Mai l i n g

MOTION o f De f t s . e x c e p t Am e s s e , Noe l & Voorhe.es, J r . f o r Co s t Bond . . C e r t ._Ser v i c e

P l t f s . P r e T r i a l Memo ____

J o i n t R e p o r t _ o n _ S t a t u s o f O b j e c t i o n s t o D i s c o v e r y

Pr e T r i a l C o n f e re n c e (HEP) . . . O r d e r e d : Mo t io n o f De f t .^.tLQ__in.tarv£na..is. G r a n te d

O r d e re d : C o u n s e l t o p r e p a r e an or d e r . . . D e f t s . Mo t i o n f o r a co s t bond Ordered

t o be h e a r d a t a l a t e r t i m e . . .Or d e r e d : D e f t s . M ot ion f o r c o n t i n u a n c e o f p r e -

t r i a l c o n f e r e n c e i s GRANTED & w i l l b e. h e l d on 1 1 / 2 5 /6 9 . . .O rde re d : F u r t h e r ____

h e a r i n g t o be h e a r d 1 1 / 1 3 / 6 9 . ’cod 1 1 / 0 /

D e f t . Memo. B r i e f i n Suppo r t of- M o t ion f o r C os t Bond, a l l de f t s . ex c e p t Am esse ,

Noel & V o r h e e s , J r .

Supp le m e n ta l J o i n t Rep o r t on S t a t u s o f D i s c o v e r y _________ ______________________

H e a r in g (WED’) D i s c o v e r y St a t u s . . . D i s c o v e r y p±Ghleas_.r.aso.lvftd_A. *.u-f t t e n o ^ d e r wi l l

_______ be p r e p a r e d by c oun s e l . . .O rde r e d : Mot i o n f o r Cost bnnd h e l d i n ___ __

_______ o r d e r e d: Poe Tr i a l t o be_h£ld_l i /25u/ .69._&_£at—f o r T r i a l t o Cour t at- 1 / 3 /JO.

_______ ef ld_ . i l /14 /o2____________________________________________________________________________

Signed (TrgDl Or d e r Mot i on t o I n t e r v e ne a s D e f t s . i s G r a n t e d , eod 1 1 / 1 4 / 6 9________

R e p o r t e r s Tr a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n gs h e l d on 11 / 5 / 6 9_________ r_________________________

ANSWER OF DEFTS . EXCEPT Noel., Arr.esse & V o orhe e s , Jr. to Cr o s s C laim o f I n t e r v e n e r

____. . .Cert, o f M a i l i n g ____________ ___________________ __________ :____________________

Memo. o f Dc .f ts . i n R e p ly t o P l t f s . Pr e l i m i n a ry Memo, o f Law

P l t f s . Cone f u s i o n s o f L a w ___________________________ ____________

I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . 1 s t S e t o f I n t e r r o g s .

MOTION o f I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . t o D i s s o l v e P e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n__ - ~ ‘ ' .. Y" " “** ... ...... .

MOTION o f I n t e r v e n i n g D ef t , f o r P r o d u c t io n o f Documents . . . C e r t . o f M a i l i n g_

_I n t e ry e n i n e D e f t s . I n t e r r o g s - t o t h e Def t _____ ;___ __________ :_________ .__ _______

S u p p le m e n ta l Ansviers t o P l t f s . 1s t Se t o f I n t e r r o g s , ______ _______ ________________

Supp lem ent a l Answer s t o P l t f s . Second s e t o f I n t e r r o g s . _____________ __________

Pre T r i a l Con f >. cr.ce (WED) . . . T r i a l t o Co u r t . . . .10 t o 15 Day s . . . F i l e d I n s t a n t e r

________1 . S i g n ed ..TED Orde r Auth o r i s i ng P r o d u c t o n &. c opy ing__________________ _______

________ 2 t Deffs_._ p r e t r i a l Memo.__ _______ __________ ____ __________ ■ ______ ________

______ 3 . I n t e r v e n i ng Def t s __ Pre T r i a l Memo_:______ ______ ___________________________ ____

_______ 4 . P l t f s . Second Re v i s ed___l i s t o f E x h i b i t s . . . . O r d e r e d : A t t y s have 1.5 days t o

____ f i l e r e s u mes o f t h e f r . w i t n e s s e s . Orde r e d : P l t f s . t o p r e p a r e a n o t i c e t o b

_ f>ub 1 ished_ r e j _ a d d i t i o n e l i n t e r v e g o r r . . . .O rde re d :_Add i t l o n a l v?i t n e s n e s & HxO

____ ___h l b j t s __t.o_ b e . s.ubiai t t e d _ by _ 1 2/2 4 / 6 9 . . . / P e r t h c r_ he a r l n .. s e t f o r 1 2 / 1 / 69 ■ 31 /26

C e r t • o f Mail i n g f o r I n t e r v e n i n g, L e f t s . Pr e T r i a l Memo, f i l ed 11 7 2 5 / 6 9 ___

Def t s ♦ O b j e c t i o n s t o JSvidrjace _ & . . .Exhibi ts _ I n t ro d t t c o d a t t h e F r e l i mlpa ry ; l^-Um c t l c n

H e a r i n g . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

rr

j _ i _ _

'69

W . U-: r t K ; ..... - ;

VS.

SCHOOL DISTRICT NUMBER ONE, ET AL

D. C. 110 R ev. Civil D ocket C on tinuation

DATS

1969

PROCEEDINGS r t u .

Ju.;

7/31 A p p l i c a t i o n f o r S t a y o f P r e l i m i n a r y I n - j u n c t i o n f i l e d by a l l D e f t s . exceot . .lament

D. V o o rh e e s , J r . , J ohn H. Amessa, and Rache l B. N oe l .

^ H e a r in g (NED) A p p l i c a t i o n f o r S t a y . . .O r d e r e d : A p p l i c a t i o n i s DENTED. , Tr. ; : - , n r v , .

s t a y i s GRANTED.. . W r i t t e n o r d e r t o f o l l o w , eod 7 / 3 1 / 6 9 —

8 / l* _ S igned (WED) Memorandum O p in io n 6 O r d e r , t h a t t h e Motion f o r p r e l i m i n a r y i n i i m e - ■

t i o n i s G r a n t e d , cod 8 / 4 / 6 9 --*----

8 / 6 P l a i n t i f f s MOTION f o r H e a r i n g on Remand and R e q u e s t f o r Imm edia te H e a r in g and

irk-k'k f o r Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g O r d e r .

8 /7 MANDATE.. . 10 th C i r c u i t . . .Remanding c a s e t o Judge Dov1«

----

(*** 8 / 6 H e a r i n g WED on M o t io n f o r H e a r i n g on Remand and f o r Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g orHerT

M a t t e r c o n t i n u e d to 8 /7

8 /7 H e a r i n g (WED) M ot ion on Remand f o r Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g Orde r CSAFtfEu u n t i l

8 : 0 0 a .m . 8 / 1 5 / 6 9 o r f u r t h e r o r d e r o f C o u r t . M a t t e r on Remand t a k e n unde r

a d v i s e m e n t .

S igned (WED) Temporary R e s t r a i n i n g O r d e r . S igned 1 2 :2 0 p. ia .

8-13 M otion o f d e f t s t o d i s m i s s . . . C e r t o f M a i l i n g ........

*8-11 D e f e n d a n t s ' B r i e f on Remand

8-14 Copy r e p o r t e r ' s t r a n s c r i p t . . p r o c e e d i n g s on 8 - 7 - 6 9

S igne d (WED) S u p p l e m e n ta l F i n d i n g s , C o n c l u s io n s and Temporary I n j u n c t i o n and

O p i n i o n a s t o A p p l i c a b i l i t y o f S e c t i o n 4 0 7 ( a ) o f t ie C i v i l R i g h t s Act o f 1.964

eod 8 - 1 4 -6 9

8-18 NOTICE OF APPEAL ' ~

Appea rance Bond on Appeal

A p o l i c a t i o n o f d e f t s . f o r S t a y o f P r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n

H e a r i n g : CM.EIL)l U a t i a n . f o r S t a y . . . O r d e r e d M o t i o n , f o r S t a y i s d e n t d

8 - 1 9 R e c e i p t f r o m U . S . C o u r - t o f A p p e a l s f o r r e c o r d o n a p p e a l

8 /25 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s h e l d on 3 / 7 / 6 9

Memo, i n S u p p o r t o f M otion to D ism is s f i l e d by D e f t s .

8 /2 6 Deposi to r) o f R o b e r t Duboi s G i l b e r t s .

E x h i b i t s on n e x t above d e p o s i t i o n / -" -

9 /5 P l t f s . Memo. O ppos ing D e f t s . M ot ion t o D i s m i s s . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e

9 / 1 0 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t ' o f p r o c e e d i n g s h e l d on 8 / 6 / 6 9 .

Reply Memo, i n S u p p o r t o f Motion to D i s m i s s . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

9/11 H e a r in g (WED) M o t io n t o D i s m i s s . . . O r d e r e d : M otion i s Denied , P l t f c o u n s e l to prep..-. r e

an O r d e r . . . O r d e r e d : D i s c o v e r y to be com ple ted in 60 d a y s , eod 5715769

\ 9 / 2 6 O rde r S e t t i n g P r e T r i a l C o n f e r e n c e f o r 1 1 / 4 /6 9

9-29 S t i p u l a t i o n f o r e x t e n s i o n o f t i m e . .

S i g n e d (WED) O r d e re d t h a t d e f e n d a n t s h a v e u n t i l 10’-6 -6 5 t o f i l e atk 'o h s v a r ”l i e f e i n ~

E n t r y o f A p p e a r a n c e o f K e nne th M. Worsucod f o r d e f e n d a n t s . "7;/ "

_ 1 0 / 2 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t , D e f t s M ot ion to D i s m i s s , o f proceedings}”T e l t r t c r f f T s / r t / f S

10 /6 ANSWER c f a l l d e f t s , e x c e p t D e f t s . 7, 8 & 9 . . .C o v t , o f M a i l i n g

****9 /15 C e r t , copy from C o u r t o f A p p e a l s t h a t t h e M ot ion i s Denied & f u r t h e r p ro ce e d in g ' s

_on t h e a p p e a l a r e h e l d i n a be yanc e u n t i l f u r t h e r o r d e r o f C o u r t . ' l u r F "

10/17 W r i t t e n I n t e r r o g s . by C e r t a i n D e f t s t o be Answered by P l t f s .

_ I Q / 17 . S igned ..(WED/ Memorandum O p i n i o n and O rd e r t h a t m o t i o n s t o d i s m i s s f o r f a i l u r e t o

. . S t a t e a ..Claim. Ora D e n i e d . . . D e f t . h ave 15 Days from 9 / 1 1 / 6 9 t o f i l e Answer.

_ _ .....S igne d 1 0 / 1 6 / 6 9 . eod 1 0 /2 0 /6 9

10/17 P l t f s . F i r s t S b t o f J n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

_____10 /2 'L. __P . i t f i r s . t . I ' . o . t . i o n . _ f o r . . P r o d u c t ion o f Documents . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

MOTIONto I n t e r v e n e a s D e f t s .

__________ __ _TENBERElL.AlTSV2iR._AND CLAIM OF INTERVFN0R3

_____1 0/2.1.. _ .Confess ion . _Q.f__A.ll. . D a r t s , e x c e p t D e f t s . 7, 8 6 9 o f Mot inn t o i n t e r v e n e . . .C e r t .M a i 1.

____ l.Q/24__ _CiO.Lt_*__Qf_Maj l i n g Mot ion to I n t e r v e n e L Tende red Answer. T Z

vs .

SCHOOL DISTRICT NUMBER ONE e t a l

D ;C . 110 Rev. Civil P o ck e t Contfixu&lJon

DATK

1969

PROCj TIDING 3 I>ate Or* :

JuvlRtnfn' j

_ 1 1 / 2 8 — P l t f s . Response to M o t io n t o D i s s o l v e P r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n f i l e d by I n t e r v e n o r s

C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

C e r t , o f M a i l i n g S'. inolem.ental Anse.rs to P l t f s . F i s t s e t o f I n t e r r o g s ■ .

12/1 H e a r in g (WED) O r d e re d : Upon o r a l moton o f I n t e r v e n e r , t h i s m a t t e r i s c o n t i n u e d

eod 1 2 / 2 / 6 9 . . .

12/2 I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . Answers t o I n t e r r o g s P ropounded by P l t f . . . . C e r t o f ' M a i l i n g

12/3 P l t f s . P a r t i a l Answers A O b j e c t i o n s t o I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . F i r s t S e t o f I n t e r r o g s , T

to t h e P l t f s . . . . C e r t o f S e r v i c e . —

1W/4 F u r t h e r P re T r i a l C o n f e re n c e (WED). . . I n t e r v e n e r s E x h i b i t s A.B .C .D & E marked

--:

F i l e d I n s t s n t e r . “ — -

S igne d (WED) O rd e r Re C l a s s A c t i o n and N o t i c e o f P e n d in g o f C l a s s A c t i o n

eod 1 2 / 4 / 6 9

12/5 Answers o f a l l Daft;,'-.,.. .except Vobrhess . , . . J r^-Aivasae & M o e t t o . c e r t a i n I n t e r v e n o r s

- -------

I n t e r r o g s .

12 /8 9b l e c t i o n s t o I n t e r r o g s . by I n t e r v e n o r s t o B a f t s . . . - .C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

12 /8 P l t f s _ . . A d d i t i o n a l . t o Tjfi.tcrvgnnxs. J n f e r r . o g f . , :R e s v o e ■ oJLErcnacted Tes t imony

....... o f . . . P l t f s • W i t n e s s e s . , . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

. _ 12/10 Si g w 1 (WEB) Qr.dgx Ba_..Clays A c t i o n , t h a t p l t f s . may m a i n t a i n t h i s a c t i o n as a c I ju

_ .. . . a c t i o n . . . . a _ . N o . f i . c e i n t h e fo rm a t t a c h e d be p u b l i s h e d i n The Rocky Mt.Kews

A. in_thc_JD-3nver P o s t , f o r 3 c o n s e c u t i v e d a y s , eod A / t 1 2 /1 1 /6 9

12/11 P l t f s . R e q u e s t s f o r A d m iss io n s o f O r i g i n a l D e f t s . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

12/12 . R e p o r t e r s P a r t i a l TrrvasQxi.pt. c f p m a e M i n g s h e l d o n l 2 / l / 6 9

R e p o r t e r s . T r a n s c r i p t (P ro T r i a l ..Conff iraxca.) J i e i d on 1 1 / 2 5 /6 9

12/15 I n t e r r o g s . t o D e f t . Rac.haal B. M e a l . . . C e r t , o f M a i l i n g

I n t e r r o g s . t o D e f t . J o h n H. A r a e s s e . . . . C e r t , o f M a i l i n o

I n t e r r o g s . t o D e f t . James D. V o o r h e e s . J r . . . . C e r t , o f M a i l i n g

12/17 Resume o f E x p e c te d T es t im o n y o f P o s s i b l e I n t e r v e n o r s ’ s W i t n e s s e s . . C e r t , o f M a i l .

12/23 ( A l l D e f t s . E x e e o t V o o r h e a s . J r . j Arnaese &. Noel A d d i t c n a l Answers t o P l t f s . 2nd

s e t o f I n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

A l l D e f t s . E x c e p t V o o r h e a s , J r . , Amesse & K e e l A d d i t i o n a l Answers t o I n t e r v e n o r s ’

I n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

Vll D e f t s . e x c e p t V o o r h e a s . J r . . Amesse A Kos l Answers t o P l t f s . 1 s t s e t o f in te r ro - .

. . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

A l l D e f t s . E x c e p t V o o r h e a s . J r . . Amesse A Noel Response t o P l t f s . R e q u e s t s f o r

A dm iss ions o f D e f t s . . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

D e p o s i t i o n o f George E. B a r d v a l l

___ 12/30 . MOTION o f I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . f o r Leave' t o Check o u t A copy P l t f s . E x h i b i t #83

_Sig.nfi.d_ (WEDl...Granting M o t i o n . n e x t a bove .

S igned R e c e i p t f o r P l t f s . E x h i b i t 83

.....___1 2 /30 ...E.rii„JN:.LaL.Co;nf.crfei\c£v.TWXD) O r d e r e d : T r i a l d a t e o f 1 / 5 / 6 9 i s v a c a t e d A r e s e t t o

- .........1 /12 /2 .0___.wri t. ton. . .order t o f o l l o w , eod 1 2 /3 0 /6 9

P l t f s . Complete Pre T r i a l L i s t o f E x h i b i t s A W i t n e s s e s . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

D e f t s . MOTION f o r O rd e r P o s t p o n i n g Date o f Commencement o f T r i a l

.. . 1 2 / 3 1 D e p o s i t i o n o f Theodore R. W h i t e , J r . • '

JDeft.s.._Se.cond_._Se.t .of A d d i t i o n a l Answers t o P l t f s 2nd s e t o f I n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t .

o f S e r v i c e .

__ l./2.Z.Z.0._

-Dcf.t.s ,...Acld.ltion-i 1 _ A n s w e rs ._ to . . I n te rve no rs I n t e r r o g s .

Answer o f D a f t . John H. Amesse t o I n t e r r o g s . t o I n t e r v e n i n g Deft:?. C e r t , o f S e r v i r e

_____1 /6 ____

_Aa3iy5X.._oJL.Te.ft^J.ames._D. V o o r h e a s , J r . t o I n t e r r o g s . o f i n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . C e r t .Se :vi ce

Ans.V7.ers c£. De£t*_R.i£hcl B, Noel t o I n t e r r o g s . o f I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . C e r t . S e r v i c e

J l e a r ip.pg_..(WED)._Pl tTs_..Motioi^ f o r C o n t in u a n c e o f T r i a l Date .. . . O r d e r e d ; W i l l i a m Ris

----- -------

— --------- GrantecL.1 cay. i_to_.en t a t:_h i&_ c ppe ax. e.tic.e_n $. .De f t_s. . C o u n s e l . . . O r d e r e d : T r i a l Data

______ of . .1 /12 /7 0 ..is . .vacated A w i l l be s e t a a l a t e r t im e , eod 1 / 7 / 7 0

l

1/9

1/12

S ig n e d ■■'(W3D) O rd e r t h a t T r i a l s h o u l d coKwence on 2 / 2 7 / 6 ~ e c t f 'T / T 2 7 7 0 "

D e f t s . Suimnaries o f E x pe c te d Tes t im ony o f l i e f t s . W i t n e s s e s V77Cer t . o f S< i v i c o — --------

(OVER)

* - SCHOOL DISTRICT LUMBER ONE,

DENVER, COLORADO, ET A L . ,

v s .

PATH

1970

1/15

PROCEEDINGS Date Order or

Judgment Noted

D e p o s i t i o n o f Paul. D. E l i t e •

1 / I 5 D e f t s , A d d i t i o n a l Answers . 'to. Jntery.e.tLQ£s.'„Inl;.Grxc?fts^ ^Csr.t_,..„Qf S e r v i c e ^ _ . -----

D e f t s . A d d i t i o n a l Answers t o I n t e r v e n e r s I n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

1/22 D e f t s . A d d i t i o n a l Answers t o P l t f s . I n t e r r o g s . . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

1/26 S t i p u l a t i o n R e l a t i n g t o A u t h e n t i c i t y o f P l t f s . E x h i b i t s . . . . , X*'

1/28 I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . L i s t o f W i t n e s s e s & L i s t o f E x h i b i t s . . . C e r t . o f M a i l i n g -

1 /BO D e f t s . Complete P r e t r i a l L i s t o f E x h i b i t s A W i t n e s s e s . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

7 /? I n t e r v e n e r s . Q b j e c i i m x i n to_Empf iS£d Q r d e r _ P l _ 1 2 / l / , 6 9 .h e a r i n g . ^ . ,-Cs.rtJ o.f H a i l i n g :

2/2 D e p o s i t i o n s o f Kenne th E. O b e r h o l t z e r , A l b e r t a jM, J e s s e r A Mary U, Morton .

q / o n c i ('WED') P re T r i a l O r d e r . . . T r i a l t o C o u r t . . . 20 t o 25 Days . eod 2 / 3 / 7 0

S ig n e d /WED) S u p p l e m e n ta l P r e t r i a l O r d e r , eod 2 / 3 / 7 0

P l t f s . T r i a l B r i e f

T r i a l t o C o u r t /WED). . . 1 s t Day. . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . R e c e s s . eod 2 / 3 / 7 0

2/3 D e p o s i t i o n o f A.,_Edgar Renton .......... .......... _.................. ......... .............. -......... N. ...................

T r i a l f-o Court- fw r » \ . . . 2nd Day. . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s . cod 2 / 4 / 7 0

2 / 4 T r i a l t o C o u r t /W E D ) . . , 3 rd D a y . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s . eod 2 / 5 / 7 0

2 /5 T r i a l at. O' C o u r t /WED) . . . 4 t h Day. . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s . eod 2 / 6 / 7 0

2 /3 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s h e l d on 1 2 / 3 0 /6 9

2 /6 S ig n e d (WED) O rde r A u t h o r i z i n g P r o d u c t i o n A Copying o f C e r t a i n R e c o r d s . . . s i g n e d

2 / 3 / 7 0 . eod 2 / 6 / 7 0

T r i a l t o C o u r t /WED). . .S t h u D a v i . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s , eod 2 / 9 / 7 0

2/11 M a r s h a l ' s r e t u r n on C i v i l Subpoena t o P ro d u c e Document o r O b j e c t (12)

2 /9*** T r i a l t o C o u r t / W E D ) . . . 6 th B a v . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s , cod 2 / 1 1 / 7 0

2 /1 0 T r i a l t o C o u r t /W E D } . , .7 th Day . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s eod 2 / 1 2 / 7 0

2 /11 T r i a l t o O.cmrt /WED) , . .8 t h Bay . . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s ..cod 2 / 1 2 / 7 0

2 /13 M a r s h a l ' s r e t u r n on C i v i l S u b p o e n a . t o P roduce Document o r O b j e c t

2 /1 6 T r i a l t o C o u r t (W E D ) . . . 9 th d a y . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . . r e c e s s eod 2 / 1 7 / 7 0

2 /2 4 D e f t s . Memorandum B r i e f

2 /17*** T r i a l t o C ou r t /WED). . . 10 th D a v . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s , cod 2 / 2 5 / 7 0

2 /18 T r i a l t o C our t (W E D ) . . . 1 1 th D a y . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s , eod 2 / 2 5 / 7 0

2 /1 9 T r i a l t o C our t / W ED) . .12 th Day . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . r e c e s s . cod 2 / 2 5 / 7 0

2 /2 0 T r i a l t o C our t (WED). . . 13 th Day. . . W i t n e s s . . . r e c e s s eod 2 / 2 5 / 7 0

2 /2 4 R e t u r n on C i v i l Subpoena

2 /2 4 T r i a l t o C o u r t (WED) . . . 1.4th Day. . . C l o s i n g A rg u m en t s . . . O rde re d rCounsa l have 10 day; '

t o f i l e a d d i t i o n a l B r i e f s . , . M a t t e r s t a n d s s u b m i t t e d A i s t a k e n u n d e r a d v i s e -

r i a n t . eod 2 / 2 5 / 7 0 /inZiS r-\

3/5 S igned (WED) Order t h a t D e f t s . be g r a n t e d an e x t e n s i o n o f t ime t o 3 / 9 / 7 0 t o f i l e

w i t h C our t t h e i r Rep ly B r i e f A a l s o t h e i r P ro p o s ed F i n d i n g s o f F a c t A Con-

e l u s i o n s o f Law. eod 3 / 6 / 7 0 Z

3 /6 I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . P r oposed F i n d i n g s o f F a c t . . . C e r t , o f M a i l i n g

3 /1 0 ANSWER to P l t f s , S u p p le m e n ta l B r i e f

D e f t s . P r o p o s e d F i n d i n g s o f F a c t . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

3/11 C e r t , o f S e r v i c e o f n e x t above .

3/21...... _ S igned (WED) Memorandum O p in ion A O r d e r . . . F i n a l Judgment w i l l be e n t e r e d a f t e r a . / . _

TOeatin^-i iAh-COuaaeL. ' id.Jthin t h e n e x t 30 d a v s . eod 3 / 2 4 / 7 0

4 /1 6 M e e t in g o f Counse l Re : I n j u n c t i o n . , , F i l o d I n s t a n t e r : D e f t s , P roposed J u d g m e n t . . .

O r d e re d : F u r t h e r h e a r i n g on 5 / 1 1 / 7 0 . a l lov ; 2 d a y s , eod 4 / 1 7 / 7 0 v/

4 /27 H e a r in g (WED) I n fo rm a l H e a r in g Re: P ro p o s ed R e s o l u t i o n s . eod 4 / 2 8 / 7 0

Copy o f R e s o l u t i o n

5 7 1 P t f s , Reply B r i e f and S u p p le m e n ta l B r i e f

I n t e r v e n i n g D e f t s . Memorandum B r i e f .

5 /5 MOTION o f I n t e r v e n i n g a t t o r n e y ' s t o w i t h d r a w . . . C e r t o f S e r v i c e ,

j {\ 1 D a f t s . P roposed p l a n . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

■--- ------- _ P t f s . Memo f o r the. H e a r in g on R e l i e f . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

WI2,i. ...X' » Lu O j C- C. X

V S .

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. 1 , e t c . e t n l 'V.. .

D. C. 110 R ev. Civil D ocket C on tinuation

{* - / • i v

.. f ■ '

*' DATE

1970

; PROCEEDINGS Date o

Judgrt^j

5 /11 TRIAL TO COUItT (WED) 15 th d a y . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s .

5/12 TRIAL TO COURT (WED),16th D a y . . . W i t n e s s e s , . . E x h i b i t s . eod 5 / 1 4 / 7 0 .... -

5 /13 TRIAL TO COURT (WED) 17 th d a y . . .W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s ___ eod 5 / 1 4 / 7 0

5 /1 4 J? i£ned (WED) Orde r a l l o w i n g C h a r l e s F. Brega a n d R o b e r t E. Temper t o w/draw as

c o u n s e l f o r I n t e r v e i n i n g D e f t s . . . e o d 5 / 1 4 / 7 0

TMAL TO COURT (llED^ 18 th Day. . . W i t n e s s e s . . . E x h i b i t s . . .O r d e r e d : M a t t e r t a k e n —

u n d e r a d v i s e m e n t . . . eod 5 / 1 5 / 7 0 ---—..

P l a i n t i f f ' s C o n f e re n c e Memorandum.. . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e . —

5/15 MOTION o f The B u i l d i n g Commit tee o f t h e F a c u l t y o f Manual High S choo l f o r l e a v - —

t o F i l e Amicus C u r i a e B r i e f . -—___.

S ig n e d (WED) O rde r A l l o w i n g above m o t i o n . . . eod 5 / 1 5 / 7 0 7i m-

5 /21 S igne d (WED) D e c i s i o n P.e Pier, o r Remedy. . . e o d 5 / 2 3 / 7 0 ( 2 5 >o k s )

c* A s / 1 4 .Marsha I d t u r n , .on S.uhp.aanz. - -r-

6 / 4 P l t f s , M o t ion t o Attend t h e C om pla in t f o r Pe rmanen t I n j u n c t i o n 6, D e c l a r a t o r Tvdu "

i n t h i s A c t i o n . . .Co ,r t . o f S e r v i c e 1 ' .. .

6 / a S i c o s d Qmp) F i n a l Dec ree & Ju d g m e n t , w i t h t h i s o r d e r The O r d e r s &. doeiruggy; cenv^ -

t a i n :d i n fch s t p i n i o n o f 5 / 2 1 / 7 0 A 3 / 2 1 / 7 0 art:: i n c o r n o v A t e d l - a r v l n , t h i s ...

.............rh,. 11 . l i a Fi.-anl . R d x y e u t , t h e r e he ir , ; no fm 'tb v .r s u b s t v n t i v < r,.Aimer

t o d e c i d e there- i s n e t j u s t ctMnie f o r d e l a y 6 t h e e n t i r e w e t t e r can re : ; be

e p p a a i o d . eod 6 / 1 1 / 7 0

6 / 1 6 IlOTIOiif o f £ ? . f t § . , jgnce i i t . J a m s D, V c y r h a e s . J r . , J ohn 11. Amoasa A Rachel R.

- - fe r T i B ^ r . « r y . &£ 1‘l m L ttesxfMi & . Jude : A n t tJ5Jl Car tu o f S e r v i c e .

6 /16 NOTICE. OF AEZEA1l_£q t ...all__.def„ts^_..£xcent: d e f t s . 7 . 8 . 9 .

. . 6 /1 7 _ .Cy...,Nat±C.&—mai.ljpd t o Hm. WhltJ-.ukp.r and p H r m m c o l

6 /19 —— —.fej ii / )_hat ioa. . to.— _2l&££&* n a t i o n i s D e n ie d . . „t?ri t t i»n Order

S.Q f o l l o w , cod 6 / 2 2 / 7 0 "

- P l t f r . ^ l ; i a X I i 2 ^ e r _ E e d u c . t i e a . o f Tirea_j&ar T r a n s m i s s i o n o f P e e re d

6 / 2 4 NQ.I.I.CJRQE 4PIAEAL_(.CE.QS8 -APPEAL 1

6 /25 Cy N o t i c e m a i l e d t o Wm. W h i t t a k e r , C l e r k , U.S. C our t o f A pnea ls and opposin' -'

. ____c o u n s e l .

Signed (WED) O rde r G r a n t i n g P t f s Motion f o r R e d u c t io n o f Time f o r T r a n s m i s s i o n

- a£_Be.cor,d..on...App-eal----- Jlejto.rd—t£L_bjw t r a n s m i t t e d J u l v 17, 1970.

S_Lgne.cL_(WEn) o r d e r Denying D e f e n d a n t s ' Motion f o r S t a y .

6/7.6 _ _ELe.ceipt from. Court. o f A ppea ls fox. Record .on Apneal

7/20 Motion f o r E x t e n s i o n o f Time f o r T r a n s m i s s i o n o f Record .

Sigaed_(TJFJl)—0xd.ex-.Gr an t i n s ex tens. i .o.n_ o f - t ime t o J j i ly 2 4 , 1970.

/ 7/7.4 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s h o l d on 6 / 1 9 / 7 0

7 /24 R e p o r t e r ' s Tr/c - c r i p : of p r o c e e d i n g s _held 5711/70 (Vo.l ume Toni v)

V 2 J _ Receipj :—jLrom_-C.oxir.t_ o.f. A p p e a l s ..£ur_Supplemenln. 1 Record on Appea l

Re.pjart.eri s . X r a n a c r i p t x a f _p.r.O-C.eeding,sdield 5 / 1 3 / 7 0 (Volume I I J9/11 . S t i p u l a t i o n .to Amend F i n a l M c r e e A..Judgiaenl: e n t e r e d on 7 7 8 /7 0

.. ._8igned_(WEj3)_..Order.. A'4.e.nding RjjxalJiecxce...Am-.J_utdgaient s e e f i l e d , eod 9 / 1 4 / 7 0

____ 10/22 . .t o AisetKL-Qr-Supp/Lorcon,t_JudgmanIt. C e r t , o f S e r v i c e

M.QXIOjL_£L£— —LQ-S.£riHv.C_I.5l.t,£-S-e_M o t io n to Around o r rf-

- . . ____ o f - H a i l i n g

10 /2 7 J l H M l g a . ° n .Hgt iong , . ( ^ S D ) . O r d e r ed : M otion o f P l t f s , t o be f i l e d i n C i r c u i t c o u r t

___ _____ £ ,L A ppc ,a lp . cod 1 0 / 2 8 / 7 0 ~ ............. ‘

- 1 2 / 2 8 .j?ltf§.«—M0T2QH-fee Si’p.plegientpi O r d e r s . , . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e1971 ~ _

1/4 LOIlO.v o f D e t t s . t o S t r i k e P l t f s . Motion f o r S u p p l e m e n ta l O r d e r s . . . C e r t . o f S a r v i r 0 »

—...------. . .__ co ^ l t f s . M otion f o r S u p p l e m e n ta l O r d e r s . . . Car t . o f S e r v i c e .

____ 1/14 . -ilv.l.Ricci-XvElQ— SrP-P.l<y»cnt.?. 1 _ 0 rde . r c da . . . W i t n e s s . . . O r d e r e d : B e r t s . t o r e p o r t t o t h e

---------------- -- — ...—.... Cour t . . 1 n ...3(Lilay,s...as to . i t s p l a n s . P l t f c o u n s e l t o p r e p a r e an o r d e r , r e c e s s .

----------___ L._______ c o d , 1 /1 4 /7 1

___ 1 /20 AASliefI O r d e r , same a s hea r ing , on 1 / 1 4 / 7 1 . cod ] / ' * l /7 1

/ wvol-)

DATE

1971

PROCEEDINGS Date Order or

Jud^mout Xg,*'.

2/16 I n t e r i m R e p o r t . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

2 /2 4 P l t f s . C o n s o l i d a t e d MOTIONS for. F u r t h e r S u p p l e m e n t a l O rde r & f o r H e a r i n g . . .

C e r t . o f S e r v i c e . / .

3 /4 Response t o P l t f s . C o n s o l i d a t e d M ot ions f o r (1). F u r t h e r A u p p le m e n la l O r d e r s

(2) H e a r in g . . . C e r t . .of S e r v i c e , y /

3 /17 H e a r i n g (WED) Judge Doyle & c o u n s e l d i s c u s s i n g m i s c e l l a n e o u s m a t t e r s p e r t a i n i n g

.j t o t h i s c a s e , eod 3 / 1 7 / 7 1

3/18 1 R e o o r t c o n t a i n i n g . a l t e r n a t i v e /Plans. f .or . I m p l e m e n t a t i o n o3L_C_Qiuit_Dx!ier_._. . . .C e r t . . -of

S e r v i c e . . . . . . . _ . . ___ . __ _____ . .. . __ ___ . -...... ...... ... __ _________

3/22 H e a r in g (WED) E x h i b i t s . . . O r d e r e d ; S e t f o r f u r t h e r h e a r i n g on 5 / 1 4 / 7 1 . . . R e c e s s . . .

eod 3 / 2 4 / 7 1 .

3/29 Hnnv n f O rde r f rom U. S , C o u r t o f A p p e a l s g r a n t i n g d e f t s . m o t i o n f o r a s t a y o f the

f i n a l d e c r e e and "judgment

1/28 H e a r in g (WED) O r d e re d : t h e May 14 h e a r i n g t o s t a n d . . .R e c e s s . . . eod 4 / 2 8 / 7 1 . * .

/14 H e a r i n g (WED) P ro p o s ed P l a n s . . . E x h i b i t s . . . W i t n e s s e s . . . O r d e r e d : M a t t e r c o n t i n u e d to

5 / 1 9 / 7 1 . eod 5 / 1 7 /7 1

3/14 P l t f s . Memo, f o r 5 /1 4 /7 1 H e a r i n g t o S e l e c t the. P l a n s t o be Implemented i n S e p t , 71.

5/19 H e a r in g (WED)Re: P r o p o s e d P l a n s , . . E x h i b i t s . . . W i t n e s s e s . . .R e c e ss t o 5 / 2 4 / 7 1 . . .

eod 5 / 2 0 / 7 1 .

5 / 2 L P i l e d h’’ Norms Mae N o b l e r Ana I t e m s t e S c hoo l I n t r e .g r a t i o n P lan

3/24 H e a r in g (WED) Re; P l a n s . . . W i t n e s s e s , . . E x h i b i t s . . . Judge Dovle c o n c lu d e s A d i r e c t s

t h a t P l a n C be a d o p te d bv t h e Schoo l Board A p u t i n t o a c t i o n as soon as

p o s s i b l e , r e c e s s , eod 5/25/71

5 /25 W ithd raw al o f A ppea rance o f A t t y . C r a i g S. B a rnes f o r P l t f , . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

6 /23 MOTION o f P l t f s . f o r D e s e g r e g a t i o n P l a n . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

6 /29 S t i p u l a t i o n t h a t P r e l i m i n a r y I n j u n c t i o n . . A F i n a l Judgment and Decree be m o d i f i e d

6 /29 Response t o M ot ion f o r D e s e g r e g a t i o n P l a n . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

7/7 Mandate r e c e i v e d from U. S. C our t o f A p p e a l s . . . The T r i a l c o u r t i s d i r e c t e d t o r e -

t a i n i u r i s d i c t i o n o f t h e c a s e f o r t h e p u r p o s e o f s u p e r v i s i n g t h e imp]eme.nta-

t i o n o f t h e p l a n , w i t h f u l l power t o c h a n g e , a l t e r o r amend t h e p l a n in the

i n t e r e s t o f j u s t i c e A to c a r r y o u t t h e o b j e c t i v e o f t h e l i t i g a t i o n as r e f l e c t e .1.1

by t h i s o p i n i o n .

2 / 1 9 P p o o - f p , - 1 s P a r t i a l of: p r o c e e d i n g s —h e l d —o n 5 / 1 4 /7 1 . . . . . _ . . . . A-

7 /28 S igned (WED) O rde r Re M ot ion f o r D e s e g r e g a t i o n P l a n . . . O r d e r e d : M ot ion d e n ie d w i t h o .it

P r e j u d i c e t o p l t f s . r i g h t s t o r e f i l e i t . . . e o d 7 / 2 9 / 7 1 .

3 /1 0 S ig n e d (WED) Orde r on Bottom o f S t i p u l a t i o n f i l e d 6/2.9/71 t h a t t h e S t inn l ar.i on i s

Approved A„ an ..Order i s here)) v n n i e t o d di r .ee t i n g _ t h a t .the..... t e n is... & c o n d i t i o n s o f

th e S t i m u l a t i o n be a r r i e d o u t . eod 8 / 1 0 / 7 1

8 /3 0 R e p o r t e r ' s P a r t i a l T r a n s c r i p t , commencing 3 / 2 2 / 7 1

9 /8 H e a r i n g (WED). . . W i t n e s s e s . , . O r d e r e d : P l a n PA" i s t o be p u t i n t o e f f e c t by 11/1 /71

. . . P l t f s . c o u n s e l t o p r e p a r e an o r d e r , eod 9 /9 /7 1

9/27 Aigned_(WED) Order.. .Re_.DMregregaiirin 0 f_l ial le .t . t_ .A Sf/adman. JE le ta ru ta ry S c h o o l s , f o he

... a c c o m p l i s h e d nfl_J_a£Ls.c .thap__llZgZZ/L___oil, o r bo / o r e 10 /8 /71 d e f t s . s h a l l p r e s e n t

_.t P t h e ..Co:rct..de.hal.l„s o J L l l i e . . p i c a to. _bn._imp_l cmer tod sm 1 1 /8 /7 1 . . . . r a c i a l & .e thn ic

___ C e ns use f__oi.ud.eji t s _ ivt_i a e _ g i 0 ^ap]iic__.ar_e a s ..u n d e r ...plan A, i n c l u d i n g Monfhel lo._A.__

____t o be cornuFeted _p.rlor_.fo p r t e r e i i t a i c i r . o f . thc...p la ir .on.. 10/&/.7.1, .eo<l 9 /28 /71

10/7 MOTION o f D e f t s . f o r S t a y . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e ,

NOTICE OF APPEAL by D e f t s .

10/8 ...Hallo 11 - Si._e.dman D eseg re g a t i o n P l a n . . . C e r t . o f S e r v i c e . . . . .

10/15 S t i p u l a t i o n Re Hal l e f t -S t e e lm a n P l a n

.Signed _(1>|E.D)._Order . t h a t __pr.evj.ons .Order. Re : . . .Pe3.egrati.oii . o f . .H a l l e i h and Steduian

____ E l e m e n ta r y Seliools, . i s . . .modi f ied t h e . . s p e r i f i c_ d e t a i l s . . o f " P l a n A" a s m o d i f i e d

........ ..in....the Ha lle±.t-=R.tedmun_ P l a n s h a l l be-dove. Ion; .-d-no-.l ;U;or_ than 12/1 / ' / 1 end

1 0 / 1 9 / 7 1 .

11/8 S t i p y l a t i o n _2.or...Di stars s a l of.. Appeal . , p u r s u a n t l o - P u l e 4 2 ( a ) ______________________ ___

__________________________________________CONTimiKP_______________________________________________

V S •

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO. L, e t c . , e t a l

D. C. 110 K>jv . Civii D ocket C on tinuation

DATE

1?21

PROCEEDINGS I>utj ("

Judxuv

11 /8 S igne d (WED) O rde r D i s m i s s i n g A p p e a l , eod 1 1 /1 0 /7 1 —11/10 MOTION o f A p p l i c a n t s f o r I n t e r v e n t i o n f o r L i m i t e d I n t e r v e n t i o n

Memo. Ln S u p p o r t o f n e x t above M otion

^ l e a d i n g i n I n t e r v e n t i o n

Request f o r Im m ed ia te C o n f e r e n c e or H e a r in g

10TI0N o f A p p l i c a t n s f o r I n t e r v e n t i o n f o r L i m i t e d A d m iss ion

l e r t . o f S e r v i c e .

11/18 dopy o f l e t t e r on f i l e t h a t t h i s c a s e has been r e a s s ig n e d , t o Judge. F i n e s i l v e r .

11/23 Signed (SGF) O r d e r R e g a r d in g M ot ion t o I n t e r v e n e . . . O r d e r e d : t h a t c o u n s e l of r e c o r d

are. d i r e c t e d t o f i l e any s t a t e m e n t s o f p o s i t i o n and memo, i n o p p o s i t i o n o r

s u p p o r t o f m o t i o n to i n t e r v e n e on o r b e f o r e 1 2 / 8 / 7 1 . . . I n t e r v e n o r a p p l i c a t n s

a r e d i r e c t e d t o r e s p o n d t o a l l memoranda on or b e f o r e 1 2 / 1 3 / 7 1 . . . t h e m a t t e r w i 1i

be s e t f o r h e a r i n g a f t e r r e c e i p t o f a l l memoranda i f i t i s deemed n e c e s s a r y . . . ~

eod 1 1 / 2 6 / 7 1 .

S igne d (SGF) O rd e r D i r e c t i n g F i l i n g o f S t a t u s R e p o r t . . . O r d e r e d : t h a t c o u n s e l a r e

d i r e c t e d to subm i t w i t h i n 20 days a s t a t u s r e p o r t on t h i s c a s e . . . e o d 1 1 / 2 6 /7 1 . /

1276 _ P l c f s . Memo, i n O p p o s i t i o n t o T N te r .ven t ion . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .

12 /8 AsueaneOt fQiL.Es. tsa3i 0.tl_of T i n a . that ._ . . r .pp l ican ts f o r T r i t e r v e n t i n n may have t h r u

1 2 / 1 7 /7 1 t o f i l e r e p l y . _ _ . , _ . . _ ..... _ .

'.Signed_XS.GI0- O rd e r on bo t to m of.. n e x t .e.boAte. .̂ g r a n t i n g . . e o d 12 /8 /7 1

D a f t s . Memo, i n O p p o s i t i o n t o M otion t o I n t e r v e n e . . . C e r t , o f S e r v i c e .I -cs

I r” R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s commehcingS/14 /71 .

12 /14 MOTTON-.of.n.ef on... K x.tensi.an xxf.Time f o r r f i l i a c .Us,-. S,tai.us.JRep,OXitM:o A i n c lu.cl.int

1 2 / 2 1 / 7 1 .

S igne d (SGF) O rd e r t h a t t h e t im e f o r f i l i n g t h e s t a t u s r e p o r t i s e x t e n d e d t o £,

i n c l u d i n g 1 2 / 2 1 / 7 1 . eod 1 2 /1 6 /7 1 — .....

12 /16 Re.p.LY_JB.ris£_of AupJo'caiiLs . f o r I n t e r v e n t i o n . „__ Cent.. m£ S e r v i c e ,

12/21 S t a t u s R e p o r t I

S ig n e d (SGF) O rde r t h a t m o t i o n t o i n t e r v e n e i s d e n i e d . . . e o d 1 2 / 2 2 / 7 1 . 1

12/22 R e p o r t e r ' s T r a n s c r i p t o f p r o c e e d i n g s commencing 5 / 1 4 / 7 1 / ' I

1

1/27. . . , P l t f s . MOTION f o r o r d e r R e l e a s i n g t h e Record

S ig n e d (SGF) O rde r t h e C le rk o f Cour t i s a u t h o r i z e d to r e l e a s e t h e r e c o r d in t h e I

a c t i o n t o Gordon G. G r e i n e r f o r a p e r i o d o f 10 davs s t a r t i n g 1 / 2 7 / 7 2 . eod 1/3' U 2 ....

R e c e i o p t f o r A c t i o n

N 2/1 L e t t e r on f i l e f rom U, S. C o u r t o f a p p e a l s t h a t Supreme Court ' g r a n t e d c e r t i o r a r i

; 2 /9 JOINT CONSOLIDATED'MOTIONS R e l a t i n g t o t h e Record

S ig n e d (SGF) O rd e r R e g a r d in g Record

2 /18 c o p i e s o f e x h i b i t s o f L e f t s . Numbered 1 t h r o u g h 12

____ •

v,__

_______

__ __ ___

*-..-__ ,

*-• *__ ____

----

la

Docket Entries

2a

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and D e c la ra to ry

Judgment

(Filed June 19, 1969)

1st th e

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F ob t h e D istrict of Colorado

Civil Action No. C-1499

W ilfred K eyes , in d iv id u a lly a n d on b e h a lf o f C h r ist i

K eyes, a m in o r ; Ch r ist in e A. C olley, in d iv id u a lly an d

on b e h a lf o f K ris M. C olley a n d M ark A. W illia m s ,

m in o rs ; I rma J. J e n n in g s , in d iv id u a lly a n d on b e h a lf

o f R honda 0 . J e n n in g s , a m in o r ; R oberta R. W ade,

in d iv id u a lly a n d on b e h a lf o f Gregory L. W ade, a m in o r ;

E dward J. S tarks, J r ., in d iv id u a lly an d on b e h a lf o f

D e n ise M ic h e ll e S tarks, a m in o r ; J o se ph in e P erez,

in d iv id u a lly a n d on b e h a lf o f Carlos A. P erez, S h eila

R. P erez a n d T erry J. P erez, m in o r s ; M axine N.

B ecker , in d iv id u a lly a n d on b e h a lf o f D in a h L. B ecker ,

a m in o r ; E u g en e R. W e in e r , in d iv id u a lly and on b eh a lf

o f S arah S. W e in e r , a m in o r,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

S chool D istrict N um ber O n e , D enver , Colorado; T h e

B oard of E ducation , S chool D istrict N um ber O n e ,

D enver , C olorado ; W illia m C. B erge, individually and

as President, Board of Education, School District Num

ber One, Denver, Colorado; S t e p h e n J . K n ig h t , J r .,

individually and as Vice President, Board of Educa

tion, School District Number One, Denver, Colorado;

J ames C. P err ill , F rank K. S o u th w o r th , J o h n H.

3a

A m esse , J ames D. V oorhees, J b., and R a ch el B. N oel,

individually and as members, Board of Education,

School District Number One, Denver, Colorado; R obert

D. G ilberts, individually and as Superintendent of

Schools, School District Number One, Denver, Colorado,

Defendants.

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and

Declaratory Judgment

I. JURISDICTION

A. Plaintiffs seek to enjoin the defendants from, main

taining, requiring, continuing, encouraging, and facilitat

ing separation of children and faculty, on the basis of race,

and further, from unequal allocation of resources, services,

facilities, equipment, and plant on the basis of race. Plain

tiffs also request specific injunctive relief pertaining to

certain resolutions passed and enacted by defendant Board

of Education, especially Resolutions No. 1520, 1524, and

1531. Copies of said Resolutions are attached to this com

plaint.

B. Plaintiffs also seek a declaratory judgment under

Title 28, Section 2201 for the purpose of determining ques

tions of actual controversy between the parties, to w it:

1. The question of whether the rules, regulations, reso

lutions, policies, directives, customs, practices, and usages

of the defendants and each of them in denying, on account

of race, color, or ethnicity, to the minor Negro and Hispano

plaintiffs and other Negro and Hispano children residing

in the school district, educational opportunities, advan

tages, and facilities afforded and available to Anglo chil

dren of public school age similarly situated in the school

district, are unconstitutional and void, as depriving said

4a

plaintiffs of equal protection of the law in contravention

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

2. The question of whether the rules, regulations, reso

lutions, policies, directives, customs, practices, and usages

of the defendants and each of them in denying to the plain

tiffs who attend schools substantially segregated on the

basis of race or ethnicity and other children residing in the

school district the advantages, educational benefits, intel

lectual stimulation and practical preparation for a multi

racial world afforded by providing an integrated education

to other children of public school age similarly situated in

the school district are unconstitutional and void as depriv

ing said plaintiffs of equal protection of the laws in con

travention of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitu

tion of the United States.

C. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under

Title 28 U.S.C. Sections 1343(3) and (4). This is a civil

action authorized by law and arising under Title 42,

Section 1983 and the Fourteenth Amendment of the Con

stitution of the United States.

D. All individual defendants reside within the District

of Colorado; defendant School District is a body corporate

organized and existing under the laws of the State of

Colorado, CBS §123-30-1 (1964). Venue is therefore

proper in this District under Title 28 U.S.C. Section

1391(b) and (c).

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and

Declaratory Judgment

II. PAETIES

Complaint for Permanent- Injunction and

Declaratory Judgment

A. Plaintiffs:

1. Plaintiffs Wilfred Keyes, Christine A. Colley, Irma

J. Jennings, Roberta E. Wade, Edward J. Starks, Jr.,

Josephine Perez, Maxine N. Becker, and Eugene E.

Weiner, are adults, citizens of the United States and the

State of Colorado, and residents within School District

Number One, Denver, Colorado.

2. Plaintiff children who sue by their parents and next

friends, are minor children, citizens of the United States

and the State of Colorado, and residents within School

District Number One, Denver, Colorado.

a. Plaintiff Christi Keyes, a minor, sues by her parent

and next friend, Wilfred Keyes; she will attend Hallett

Elementary School (10.1% Anglo, 84.4% Negro, 3.7%

Hispano) beginning in September, 1969. They are Negro.

b. Plaintiff Kris M. Colley, a minor, sues by his parent

and next friend, Christine A. Colley, and is a resident

of an attendance area detached from the attendance area

of East High School by provision of Resolution No. 1520

described hereinafter. If action is taken to implement the

recision of said resolution, he will attend East High School

(53.7% Anglo, 39.6% Negro, 5.8% Hispano) in September,

1969. They are Negro.

c. Plaintiff Mark A. Williams, a minor, sues by his

guardian and next friend, Christine A. Colley, and is a

resident of an attendance area detached from the atten

dance area of Smiley Junior High School by Resolutions

No. 1520 and 1524 described hereinafter. If action is taken

to implement the recision of said resolutions, he will attend

Smiley Junior High School (23.6% Anglo, 71.6% Negro,

3.7% Hispano) in September, 1969. They are Negro.

d. Plaintiff Rhonda 0. Jennings, a minor, sues by her

parent and next friend, Irma J. Jennings, and is a resident

of an attendance area detached from the attendance area

of Cole Junior High School by Resolution No. 1524. If

the recision of said resolution is implemented, she will

attend Cole Junior High School (3.8% Anglo, 72.5%

Negro, 22.2% Hispano) beginning in September, 1969.

They are Negro.

e. Plaintiff Gregory L. Wade, a minor, sues by his

parent and next friend, Roberta R. WTade, and is a resident

of an attendance area detached from Barrett Elementary

School by Resolution No. 1531 described hereinafter. If

action is taken to implement the recision of said resolu

tion, he will attend Barrett Elementary School (0.3%

Anglo, 96.9% Negro, 1.9% Hispano) in September, 1969.

They are Negro.

f. Plaintiff Denise Michelle Starks, a minor, sues by

her parent and next friend, Edward J. Starks, Jr., and

is a resident of an attendance area detached from Philips

Elementary School by Resolution No. 1531. If action is

taken to implement the recision of said resolution she will

attend Philips Elementary School (55.3% Anglo, 36.6%

Negro, 5.2% Hispano) in September, 1969. They are

Negro.

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and

Declaratory Judgment

7a

g. Plaintiff Carlos A. Perez, a minor, snes by Ms parent

and next friend, Josephine Perez, and will attend West

High School (54.7% Anglo, 4.6% Negro, 39.8% Hispano)

beginning in September, 1969. They are Hispano.

h. Plaintiff Sheila R. Perez, a minor, snes by her parent

and next friend, Josephine Perez, and will attend Baker

Junior High School (15.4% Anglo, 10.0% Negro, 73.1%

Hispano) beginning in September, 1969. They are Hispano.

i. Plaintiff Terry J. Perez, a minor, snes by his parent

and next friend, Josephine Perez, and is a student at

Greenlee Elementary School (19.1% Anglo, 25.0% Negro,

54.5% Hispano). They are Hispano.

j. Plaintiff Dinah L. Becker, a minor, sues by her

parent and next friend, Maxine N. Becker, and is a student

at Merrill Junior High School (98.2% Anglo, 0.3% Negro,

0.8% Hispano). They are Anglo.

k. Plaintiff Sarah S. Weiner, a minor, sues by her

parent and next friend, Eugene R. Weiner. Prom January

through June, 1969, she was a participant in a voluntary

enrollment plan and was a student at Hallett Elementary

School (10.1% Anglo, 84.4% Negro, 3.7% Hispano). She

has been informed by defendants that there may or may

not be space available at said school in September, 1969,

and therefore does not know what school she can attend.

They are Anglo.

3. Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and

in behalf of others pursuant to Rule 23(b) (1) (B), 23(b) (2)

and 23(b)(3), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and

Declaratory Judgment

8a

(a) The class which the plaintiffs represent is so

numerous that joinder of all members thereof is

impractical; said class consists of:

(i) All those school children, who by virtue of

the actions of the Board complained of in

the First Cause of Action will be attending

segregated or substantially segregated schools

and who will be forced to receive an unequal

educational opportunity beginning in Sep

tember, 1969;

(ii) All those school children, who by virtue of

the actions or omissions of the Board com

plained of in the Second Cause of Action will

be and have been attending segregated schools

or substantially segregated schools, and who

will be and have been receiving an unequal

educational opportunity.

(b) There are questions of fact and law common to

all members of the class represented by plaintiffs,

namely:

(i) Whether in fact the members of said class,

by virtue of the actions of the Board com

plained of in the First Cause of Action will

be attending segregated or substantially

segregated schools, and will be forced to

receive an unequal educational opportunity,

and, further, whether in law such actions of

the Board are unconstitutional and void;

(ii) Whether in fact the members of said class,

by virtue of the actions or omissions of the

Complaint for Permanent Injunction and

Declaratory Judgment

9a

Board complained of in the Second Canse of

Action will be and have been attending

segregated or substantially segregated schools

and will be and have been receiving an un

equal educational opportunity, and further,

whether in law such actions and omissions

of the Board are unconstitutional and void.

(c) The claims of the individual minor plaintiffs are

representative and typical of the class, in that

each such plaintiff reflects and illustrates either

or both of the types of deprivation complained