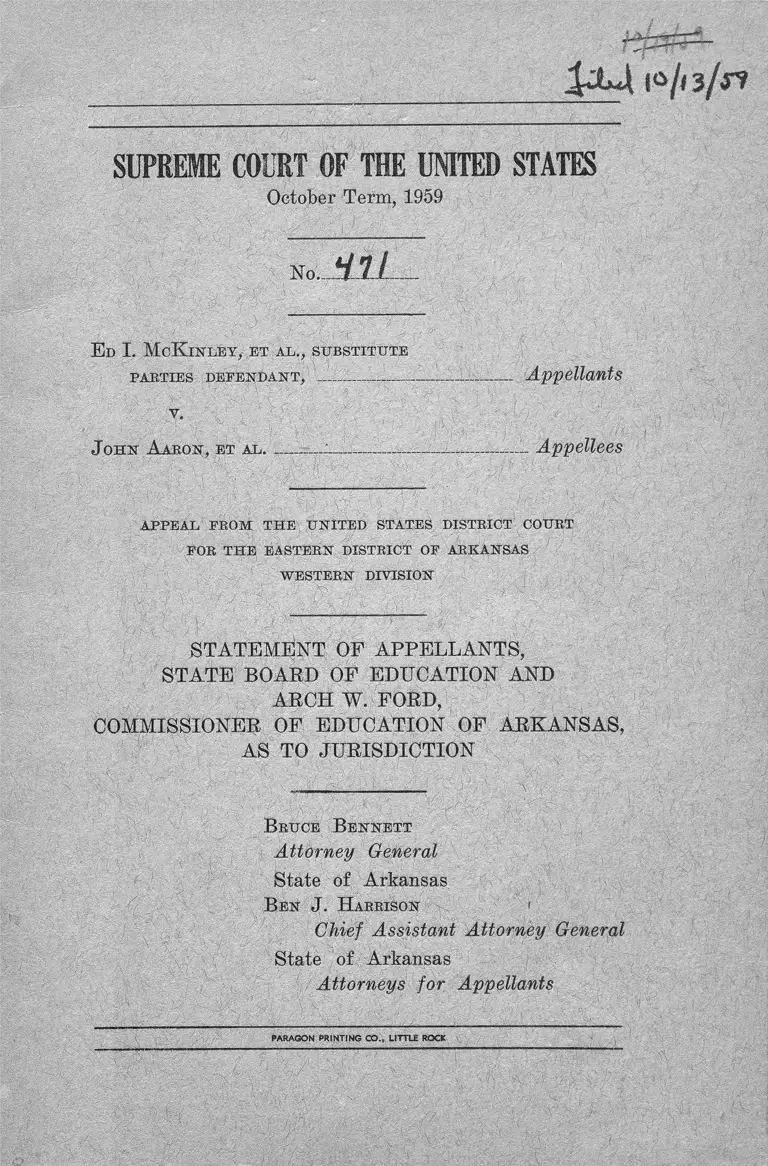

McKinley v. Aaron Statement of Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 13, 1959

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McKinley v. Aaron Statement of Appellants, 1959. 8e7b98a2-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/22b0ab2b-a39b-4a4a-b8fc-62761722d038/mckinley-v-aaron-statement-of-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

i° / i 3 /r?

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1959

No. Mil

E d I. M cK inley, et al., substitute

parties defendant, _1— -— -------——------ Appellants

v.

J ohn A aron, et al. — — --------------------- ------------Appellees

APPEAL PROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

POR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS

WESTERN DIVISION

STATEMENT OF APPELLANTS,

STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION AND

ARCH W. FORD,

COMMISSIONER OF EDUCATION OF ARKANSAS,

AS TO JURISDICTION

B ruce B ennett

Attorney General

State of Arkansas

B en J . H arrison <

Chief Assistant Attorney General

State of Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

PARAGON PR I NT! NG CO. , LITTLE ROCK

I N D E X

Page

Statement as to jurisdiction _______________ _____ _____ ;--------- ---- 1

Opinion below _________________________________________________ 1

Jurisdiction ____________________________________________ 1

Statutes involved ---- --------------------------------------------------------- ---— 2

Questions presented ---------------------------------------------------- 3

Statement of the case __________________________ ______________ 3

Conclusion --------- 7

Cases:

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F. 2d 97 ------------------------------------------------- 1

Radio Corporation of America v. United States, 95 F. Supp. 660,

Affirmed 341 U.S. 412 _____ ----------------------------------------------~ 2

St. John v. Wisconsin Employment Relations Board, 340 U.S. 411_ 2

Texas Company v. Brown, 258 U.S. 466 ------------------------------------- 2

Hines v. Davidowitz, 312 U.S. 331 —------------------------------ 2

Fitzhugh v. Ford, Commissioner, Ark. Law Rep., Vol. 105 --------- 5

Statutes:

Ark. Const., Amend. 7 ---------------------------------- 2

Appendix --------------- --------------------------------------- -— ...-.... .... —* la

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1959

No.

E d I. M cK inley, et al., substitute

parties defendant, ___ __________ _____ Appellants

V .

J ohn A aron, et al____________________________Appellees

STATEMENT AS TO JURISDICTION

This appeal is from the decision of the United States

District Court, Eastern District of Arkansas, Western

Division, entered on June 18, 1959, holding Act 5, Ark.

Acts of 1958 (2nd Ex. Sess.), as amended, unconstitutional

and permanently enjoining these appellants from engaging

in any acts which would directly or indirectly impede,

thwart, delay or frustrate the execution of the approved

plan for the gradual integration of the schools of the

Little Rock School District. This statement is presented

to show that the lower court erred in its decision.

OPINION BELOW

The District Court, on June 18, 1959, delivered its

decision upon the issues raised by the supplemental com

plaint and the answers thereto. The opinion is reported

at 173 F. Supp. 944 and appears in the appendix hereto

at page la.

JURISDICTION

This action, another phase of Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.

2d 97, and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, was begun by

plaintiffs filing a supplemental complaint pursuant to 28

9

U.S.C.A. §§2281, 2284, 2201 and 2202. The supplemental

complaint alleged the unconstitutionality of Act 4, and

Act 5 as amended by Act 151, Ark. Acts of 1959, and

sought declaratory and injunctive relief. The jurisdiction

of this Court to review by direct appeal the action of a

three-judge court rests upon 28 U.S.C.A. §§1253 and 2201

(b). An appeal to the Supreme Court of the United

States from the decision of a three-judge court is a matter

of right. Radio Corporation of America v. United States,

95 F. Supp. 660, Affirmed 341 U.S. 412. Judgments of

three-judge courts are properly appealable directly to the

Supreme Court of the United States. St. John v. Wiscon

sin Employment Relations Boardl, 340 U. S. 411.

STATUTES INVOLVED

Act 5, Ark. Acts of 1958 (2nd Ex. Sess.), as amended

by Acts 151 and 466, Ark. Acts of 1959, is set out in the

appendix hereto at pages 17a through 24a. At the

time of the hearing on May 4, 1959, the provisions of Act

466, supra, were not in effect. Act 466 was approved with

out an emergency clause on March 31, 1959, but did not

become effective until 90 days after the Legislature ad

journed. Hence, the effective date of the Act was June

11, 1959, Ark. Const., Amend. 7. While Act 466 was in

effect shortly before the decision of the lower court, it

apparently was not considered. Thus, the situation pre

sented here is similar to a case where there has been

legislation enacted after the decree of a lower court, and

the effect of Act 466 should be considered by this Court.

See Texas Company v. Brown, 258 U.S. 466; Fines v.

Davidowits, 312 U.S. 331. Hereafter in this brief, a ref

erence to Act 5, as amended, refers to the Act, as amended

by Acts 151 and 466, Ark. Acts of 1959.

Act 5, as amended, authorizes the withholding of

State funds from schools where: (a) such schools have

3

been closed by order of the Governor under the provi

sions of Act 4, Ark. Acts of 1958 (2nd Ex. Sess.); or (b)

whenever a student should be accepted for enrollment in

a school other than the one which he normally would at

tend; and authorizes pro rata payments of State funds to

other districts only under the condition set forth in (a)

above.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The questions presented by this appeal are whether

the lower court was correct in holding Act 5, as amended,

unconstitutional because it was complementary to and

dependent upon Act 4 and that funds withheld from a

school district were allocable to that school district on a

constitutional basis, and whether the court was correct

in permanently enjoining these appellants from applying

the provisions of Act 5, as amended.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The Arkansas State Board of Education and Arch

W. Ford, Commissioner of Education of Arkansas, were

made parties defendant in the supplemental complaint

filed on January 17, 1959. The plaintiffs sought tempo

rary and permanent injunctive relief from the provisions

of Act 5, as amended, and also asked the court to declare

whether Act 5 denied plaintiffs and those similarly

situated of rights guaranteed them by the Due Process

and Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States. These ap

pellants answered alleging that the complaint failed to

state a claim against them for which relief could be granted

and denied the material allegations of the complaint. The

provisions of Act 5, as originally enacted, had been pre

viously put into effect and some funds withheld from the

Little Rock School District and paid to other districts

where former students of Little Rock schools were in at

4

tendance. Act 5, as amended, merely authorizes the State

Board of Education to withhold State funds from schools

which have been closed by the Governor under Act 4,

supra, or where a student has transferred from one school

to another. Before Act 466 amended Act 5, as amended by

Act 151, these withheld funds could be paid to another dis

trict which had accepted a student under either of the

foregoing situations. After Act 466 became effective, the

funds could be withheld as before but could not be paid

to another district except where a school had been closed

by the order of the Governor, and any unexpended surplus

had to be returned to the district at the end of the school

year. The District Court simply held that Act 5, as

amended by Act 151, was invalid because it was dependent

upon Act 4. As stated heretofore, the effect of Act 466

was not considered; and when the effect of the Act is con

sidered, it is clear that the opinion of the District Court

was in error. On the face of the Act as it now stands, it

is obvious that Act 5, as amended, is not completely de

pendent upon the provisions of Act 4.

The substantial questions that arise here thus address

themselves to the Court’s decision. Can a federal court

render wholly unconstitutional an act which, while de

pendent in one phase on an act held unconstitutional, has

an application and operation purely local in its nature?

Aside from the provisions of Act 466, is partial or even

complete dependency of operation on an alleged uncon

stitutional act sufficient grounds to invalidate the de

pendent act? A second and more serious question is

whether a school district has any right to funds gratui

tously paid to it by a state which is protected by the Federal

Constitution. This latter question arises out of the Court’s

holding that Act 5 “ did not, and does not, authorize the

State Board of Education to deprive the Little Rock School

District of State funds allocable to it for the maintenance

5

of its schools on a constitutional basis, or to divert any

part of those funds to other schools or other districts.”

Bearing in mind that the District Court did not say that

the particular application of Act 5 deprived these plain

tiffs and others similarly situated of their share of funds

normally allocable to them by the State, can it be said that

the Little Rock School District is constitutionally entitled

to any State funds ? The State questions on State con

stitutional requirements had been precluded by the hold

ing of the Arkansas Supreme Court in Fitzlmgh, v. Ford,

Commissioner, Ark. Law Rep., Yol. 105, Opinions de

livered May 4, 1959. Therefore, the question posed by

the holding is indeed substantial since it invades an area

heretofore regulated and controlled by the states which

support their schools with state funds.

If this Court should wish to assume for purposes of

this statement that Act 4 is unconstitutional, such assump

tion would not change appellant’s argument nor will it

sustain the District Court’s ruling. It is true a part of

the operation of Act 5, as amended by Act 151, does hinge

on the validity of Act 4, but the most that can be argued

on this point would be the mootness of Act 5. Obviously,

there is an application of Act 5 having no relation to Act

4, and the validity or even the existence of Act 4 is im

material. The application is obvious on the face of the

Act. Simply stated it is this: When a student leaves

the school he would normally attend, his share of State

funds is withheld from the district he leaves. When the

school year is over, the funds are returned to the district.

This procedure deprives no student or school or agency of

anything. The distridt is merely temporarily deprived of

funds for a student or students it is not educating. It

cannot be argued that this result was not the intention of

the Legislature. The Act as it now stands speaks for it

self; and up to tins point, no court has held that the per

6

sonal preference of individual students as to the school

they would not attend could be exercised in such a manner

as to deprive other students of constitutional rights. This

is not a case of an attempt to frustrate or thwart the de

segregation of a public school by State action. The de

cision of one or all of the white or colored students not

to attend an integrated school does not or would not change

its integrated nature in law, nor can it be said that Act

5, as amended, assists these students to attend other

schools since funds may not be paid to other districts under

Section 3 (Act 466, Ark. Acts of 1959) for these transfer

ring students.

It is earnestly insisted by these appellants that the

District Court erred in its holding and abused its discre

tion in granting the injunction prayed since there was

absolutely no showing that appellees would suffer any

injury or be deprived of any right by the operation of Act

5 or either of its amendments, and certainly not by Act

5 in its present form. Appellants recognize that a con

stitutional law may be applied in an unconstitutional man

ner, but this is not the question before the Court. The

action was brought alleging personal deprivations of

rights. The relief was g r a n t e d on the basis of

rights belonging to a school district and a theory of un

constitutionality by association.

If the District Court’s broad holding is allowed to

stand, it will jeopardize a whole segment of school laws,

not only in Arkansas, but in many states that provide

gratuitous aid to schools and which have many laws of

long standing regulating the amount, the manner and other

details of state aid.

7

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, it is respectfully submitted

that the decision of the lower court be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

B ruce B ennett

Attorney General

State of Arkansas

B en J . H arrison

Chief Assistant Attorney General

State of Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

APPENDIX

DECISION

of

THE DISTRICT COURT

Opinion Delivered June 18, 1959

Civil Action No. 3113

J ohn A aron, et al. _________________ _______ Plaintiff

v.

E d I. M cK inley , et al, .... ............................ Defendant

PER CURIAM.

This case was tried and argued to this statutory three-

judge court on May 4, 1959, upon the issues raised by the

supplemental complaint of the plaintiff’s and the answers

of the defendants. The action is a class action brought

by school-age children of the Negro race and their parents

and guardians, all residents of Little Rock, Arkansas.

Declaratory and injunctive relief is sought against the

defendants, State officers of the State of Arkansas, upon

the claim that Act No. 4 of the Second Extraordinary Ses

sion of the Sixty-first General Assembly, 1958, of that

State, pursuant to which the Governor on September 12,

1958, closed the four senior public high schools of Little

Rock, both Negro and white, is unconstitutional under the

due process and. equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, and

that Act No. 5 of the same Session, as later amended, by

vritue of which state funds allocable to the Little Rock

School District for the maintenance and operation of its

public schools have been withheld from the District and

diverted to other schools, is likewise unconstitutional and

void.

The defendants are the Governor of Arkansas, the

State Commissioner of Education, the members of the

State Board of Education, the Superintendent of the

Little Bock Public Schools, the members of the Board of

Directors of the Little Bock School District, and other

State officers asserted to have a relation to the ease.

In their supplemental complaint, the plaintifs

allege:

“ Acts No. 4 and 5, as amended by Act 151 of

the Arkansas Acts of 1959, are part of a studied

plan devised by the Governor and General Assembly

of Arkansas to preserve racial segragation in the

public schools and thus evade or frustrate com

pliance with the decision of the Supreme Court of

the United States in the School Segregation Cases

and, more specifically, the decrees of this Court,

the Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court in the

instant case. Each order of the federal courts to

implement the constitutional rights of plaintiffs

and others similarly situated to an unsegregated

education has been met by action of the legislative

and executive departments of Arkansas designed

to nullify those orders. (Report of the Governor’s

Committee to Make Recommendations for Official

Action, February 24, 1956; Constitutional Amend

ment No. 44 to the Constitution of Arkansas,

adopted Nov. 6, 1956; Arkansas Statutes 1947,

§§6-801 to 6-824; Arkansas Statutes 1947, §§80-

1519 to 80-1525, Acts No. 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14,

15, 16, 17 of the General Assembly of Arkansas,

2nd Extraordinary Session 1958, approved Septem

ber 12, 1958.)

“ The State of Arkansas has undertaken as a

state function to provide a system of free public

schools for the education for all persons between the

ages of six and twenty-one years. Arkansas Con

stitution Article 14, §1.

“ Acts No. 4 and 5 as amended by Act No. 151

of the Arkansas Acts of 1959, in authorizing the

closing of the public high schools of the Little Rock

School District, the withholding of funds from

them because they were in the process of being de

segregated pursuant to Court order, and the pay

ment of said funds to ‘ non-profit private’ schools

which enroll pupils who formerly attended the

schools now closed, is designed to nullify the orders

of this Court and to condition the maintenance of

public schools upon their operation in an unconsti

tutional manner and upon the waiver by plaintiffs

of rights secured to them by the Constitution of the

United States, all in violation of rights, privileges

and immunities guaranteed to plaintiffs by the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States.”

The plaintiffs ask this Court to declare Act No. 4 and

Act No. 5, as amended, unconstitutional; to enjoin the de

fendants and those in concert with them from enforcing or

seeking to enforce the Acts in question; to enter a judg

ment ordering that the public schools in Little Rock be

opened, operated and maintained on a nonsegregated basis

in accordance with the previous orders of the United

States Courts in that regard; and to enjoin the defend

ants from further acts to prevent the carrying out of such

federal court orders.

The complete history of this controversy from its in

ception to September 12, 1958, has been stated by the

Supreme Court of the United States in its opinion in

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 TJ.S. 1, unanimously affirming the

United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit in

reversing an order of the United States District Court

suspending the approved plan of gradual integration for

the period of two and one-half years.

The Supreme Court had on September 12, 1958, in

that case, entered an order reading as follows (page 5 of

358 U .S .):

“ It is accordingly ordered that the judgment

of the Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit,

dated August 18, 1958, 257 F.2d 33, reversing the

judgment of the District Court for the Eastern Dis

trict of Arkansas, dated June 20, 1958, 163 P.Supp.

13, be affirmed, and that the judgments of the Dis

trict Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas,

dated August 28, 1956, see 143 F.Supp. 855, and

September 3, 1957, enforcing the School Board’s

plan for desegregation in compliance with the de

cision of this Court in Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294, be reinstated. It

follows that the order of the Court of Appeals

dated August 21, 1958, staying its own mandate is

of no further effect.

“ The judgment of this Court shall be effective

immediately, and shall be communicated forthwith

to the District Court for the Eastern District of

Arkansas.”

Upon the entry of that order, the Little B.ock School

Board and the Superintendent of Schools were again under

mandate to carry out the approved plan of integration of

the schools of Little Bock.

The further history of this litigation and its factual

background is to be found in the opinion of the Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, of November 10, 1958, in

Aaron v. Cooper, 261 F.2d 97. That court points out that

after its opinion of August 18, 1958 (257 F.2d 33), hold

ing to be legally unwarranted the 21^-year suspension of

the approved plan of integration granted by the District

Court in 163 F.Supp. 13, the Governor of Arkansas called

the General Assembly into extraordinary session; that on

August 26, 1958, it passed, with emergency clauses, the

two Acts in question, which, however, were not signed by

the Governor until September 12, 1958, the day the

Supreme Court of the United States entered its order in

Cooper v. Aaron, affirming the decision of the Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit, 257 F.2d 33; that on the

same day, acting under the authority purported conferred

upon him by Act Mo. 4, the Governor issued a proclama

tion closing all of the senior high schools of Little Rock,

and called for an election in the School District, to vote on

the alternative ballot proposition of “ For Racial Integra

tion of All Schools Within the ____ _______ School Dis

trict” or “ Against Racial Integration of All Schools With

in the _____________ __ School District” ; that Act No. 4

provided that, unless a majority of the qualified electors

of the District vated in favor of integration, “ no school

within the district shall be integrated” , and that a school

closed by executive order authorized by the Act ‘ ‘ shall re

main closed until such executive order is countermanded

by proclamation of the Governor” ; and that the vote at

the election was about 19,000 against, and 7,500 for, racial

integration of all schools in the Little Rock School District

(page 101 of 261 F.2d).

Speaking of Act Mo. 5, the Court of Appeals said on

page 99 of 261 F.2d:

“ Act No. 5 was complementary to Act No. 4,

in its provisions for withholding from a school dis

trict, in which the Governor had ordered a school

closed, a pro rata share of the State funds otherwise

allocable from the County General School Fund, and

making such withheld funds available, on a per

capita basis, to any other public school or any non

profit private school accredited by the State Board

of Education (of which the Governor was a member),

which should be attended by students of a closed

school, with an obligation being imposed upon the

State Board of Education in these circumstances to

make such payments. §§2 and 3.”

While the Court of Appeals expressed no opinion with

respect to the constitutionality of Acts No. 4 and 5, it

ruled that the Little Rock School Board, which was under

mandate of the federal District Court to effectuate the

plan for the gradual integration of the public schools of

Little Rock approved by that Court in Aarno v. Cooper,

143 F.Supp. 855 (a ff’d in Aaron v. Cooper, 243 F.2d 361),

could not lease the high school buildings of the District to

a Private School Corporation for the operation of schools

on a segregated basis, nor could the School Board other

wise disable itself from carrying out the court-approved

plan of integration.

The District Court was directed by the Court of Ap

peals to enjoin the School Board, its members, and their

successors, from transferring the high schools or other

property of the District for the carrying on of any segre

gated school operations of any nature and to provide that

the Board and its members and their successors “ shall

take such affirmative steps as the District Court may here

after direct, to facilitate and accomplish the integration of

the Little Rock School District in accordance with the

Court’s prior orders’ ’ (page 108 of 261 F.2d).

The Supreme Court of Arkansas on April 27, 1959,

by a four-to-three majority, in the case of Garrett v. Fau-

bus, Governor of Arkansas, ..... Ark. ....... ........., 323 S.W.

2d 877, held that Act No. 4 did not conflict with any provi

sion of the Constitution of the State of Arkansas or with

the Constitution of the United States. Justice Ward

wrote the opinion of the Court. Justice Robinson and

Chief Justice Harris each wrote a concurring opinion.

The four justices of that Court who believed

that the Act was valid both under the Constitution

of Arkansas and the C o n s t i t u t i o n of the United

States were of the view that the Act represented

a reasonable and proper exercise of the police power of the

State to meet a temporary emergency , and — to quote *

from the opinion of Justice Ward — “ to protect the peace

and welfare of the people, and to effect a workable solu

tion of this momentous problem [integration of the

schools] — all within the framework of the Brown opinion

\Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IJ.S. 483, 349 TJ.S.

294] . ”

Justice Robinson, in his concurring opinion, had this

to say (page 892 of 323 S.W.2d):

“ * * # In order to prevent violence that would

be brought about by sending the Negro children to

White schools, and to prevent the use of armed

troops in the school buildings and on the school

grounds, the Legislature authorized the Governor

to close the school affected. Rut, undoubtedly, the

General Assembly felt that if a majority of the

voters, including Negro voters (who constitute a

large percentage of the total electors in Little

Rock), felt that the schools should be opened, then

the schools could be conducted without the use of

troops and United States Marshals. Act No. 4,

therefore, provides for an election to determine if

the people wanted the schools opened. Such an

election was held, and the vote was overwhelming

in favor of keeping the schools closed.” [ #]

Chief Justice Harris was also of the viewT that Act No. 4

represented a valid exercise of the police power of the

* It is to be noted that the only choice given voters under

Act No. 4 was to vote either for or against “Racial Integration of All

Schools * * *,” and not upon the question of having the schools open

or closed.

State to meet a situation ‘ ‘ sufficiently inimical to the pub

lic safety and welfare to justify the legislation * #

Justice McFaddin, in his dissenting opinion, expressed

the view that Act No. 4 was violative of Section 1 of Ar

t ic le 14 of the State Constitution providing that “ * * *

the State shall ever maintain a general, suitable and effi

cient system of free public schools whereby all persons in

the State between the ages of six and twenty-one years may

receive gratuitous instruction” , and opposed to decisions

of the Arkansas Supreme Court construing that provision

of the Arkansas Constitution.

Among other things, Justice McFaddin said (page 900

of 323 S.W.2d):

“ * * * If the People of Arkansas want to strike

Art. 14 from the Constitution, then the schools may

be closed under some legislation similar to Act No.

4. But until Art. 14 of the Constitution is repealed,

then it is my solemn and sincere view that Act

No. 4 is violative of the Arkansas Constitution.”

He expressed the view that the police power of a state may

not be used to invade or impair the liberty of citizens

guaranteed by the State Constitution, and said: “ In

short, the Arkansas Legislature cannot under the guise

of the police power, enact legislation contrary to the Ar

kansas Constitution.” He stated that the situation with

which the Court was dealing was not the kind of an emer

gency that permits the use of “ Emergency Police Powers,”

and further said, in that regard: “ Rather, we are dealing

with a condition that has already existed since 1954 and

will continue to exist until either the United States Con

stitution is amended or the United States Supreme Court

overrules Brown v. Board of Education.”

Apparently, all of the State Justices were agreed that

Section 1 of Article 14 of the Constitution of Arkansas

requires the continued maintenance by the State of free

public schools. In Justice Ward’s opinion, in which Jus

tice Eobinson and Chief Justice Harris concurred, it is

said (pages 880-881 of 323 S.W.2d):

“ * * * If Act 4 is viewed as giving the Gover

nor the power to close all public schools permanent

ly, it would, we concede, be in violation not only of

the decree in the Brotvn case [Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294] but also of

the State Constitution, but we do not consider it

that way. * * * we take it as well understood that

the Act was intended to slow down the implementa

tion of integration until it could be accomplished

without great discomfort and danger to the people

affected or until a lawful way could be devised to

escape it entirely.* *

As we read the opinion of the Supreme Court of the

United States in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, it, in effect,

holds that no lawless violation or threat, fear or anticipa

tion of such violence, resulting from hostility to the inte

gration of its schools, can justify any State, under the

guise of the exercise of its police power, in depriving

citizens, either temporarily or permanently, of rights

guaranteed them by the Constitution of the United States.

The Court said (pages 16-17 of 358 U .S .):

“ The constitutional rights of respondents

[Aaron, et ah] are not to be sacrificed or yielded

to the violence and disorder which have followed

upon the actions of the Governor and Legislature.

As this Court said some 41 years ago in a unani

mous opinion in a case involving another aspect of

racial segregation: ‘ It is urged that this proposed

segregation will promote the public peace by pre

venting race conflicts. Desirable as this is, and

important as is the preservation of the public peace,

this aim cannot be accomplished by laws or ordi

nances which deny rights created or protected by

the Federal Constitution.’ Buchanan v. Warley,

245 U.S. 60, 81. Thus law and order are not here

to be preserved by depriving the Negro children

of their constitutional rights. The record before

us clearly establishes that the growth of the Board’s

difficulties to a magnitude beyond its unaided power

to control is the product of state action. Those

difficulties, as counsel for the Board forthrightly

conceded on the oral argument in this Court, can

also be brought under control by state action.

“ The controlling legal principles are plain.

The command of the Fourteenth Amendment is

that no ‘ State’ shall deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. ‘A

State acts by its legislative, its executive, or its

judicial authorities. It can act in no other way.

The constitutional provision, therefore, must mean

that no agency of the State, or of the officers ox-

agents by whom its powers are exerted, shall deny

to any person within its jurisdiction the equal pro

tection of the laws. Whoever, by virtue of public

position under a State government . . . denies or

takes away the equal protection of the laws, vio

lates the constitutional inhibition; and as he acts

in the name and for the State, and is clothed with

the State’s power, his act is that of the State. This

must be so, or the constitutional prohibition has no

meaning.’ Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 347.

Thus the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amend

ment extend to all action of the State denying equal

protection of the laws; whatever the agency of the

State taking the action, see Virginia v. Rives, 100

U.S. 313; Pennsylvania v. Board of Directors of

City Trusts of Philadelphia, 353 U.S. 230; Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1; or whatever the guise in

which it is taken, see Derrington v. Plummer, 240

F.2d 922; Department of Conservation and Devel

opment v. Tate, 231 F.2d 615. In short, the con

stitutional rights of children not to be discriminated

against in school admission on grounds of race or

color declared by this Court in the Brown case can

11 a

neither be nullified openly and directly by state

legislators or state executive or judicial officers,

nor nullified indirectly by them through evasive

schemes for segregation whether attempted ‘ in

geniously or ingenuously.’ Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S.

128, 132.”

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, in his concurring opinion,

said (pages 21-22 of 358 U.S.) :

“ The use of force to further obedience to law

is in any event a last resort and one not congenial

to the spirit of our Nation. But the tragic aspect

of this disruptive tactic was that the power of the

State was used not to sustain law but as an instru

ment for thwarting law. The State of Arkansas is

thus responsible for disabling one of its subordi

nate agencies, the Little Bock School Board, from

peacefully carrying out the Board’s and the State’s

constitutional duty. Accordingly, while Arkansas

is not a formal party in these proceedings and a

decree cannot go against the State, it is legally and

morally before the Court.

“ We are now asked to hold that the illegal,

forcible interference by the State of Arkansas with

the continuance of what the Constitution commands,

and the consequences in disorder that it entrained,

should be recognized as justification for undoing

what the Board of Education had formulated, what

the District Court in 1955 had directed to be car

ried out, and what was in process of obedience. No

explanation that may be offered in support of such

a request can obscure the inescapable meaning that

law should bow to force. To yield to such a claim

would be to enthrone official lawlessness, and law

lessness if not checked is the precursor of anarchy. * # # > >

See, also Fembus v. United States, 8 Cir., 254 F.2d 797,

807.

Tlie deplorable conditions which were found by the

Honorable Harry J. Lemley, United States District Judge,

to have existed at Little Eock Central High School during

the 1957-58 school year, when nine Negro students were

enrolled in the formerly all-white school attended by about

2,000 pupils, and which he honestly and sincerely believed

justified granting a 21^-year moratorium to the School

Board in the carrying out of its plan of integration (163

F.Supp. 13), were held insufficient to support his order

both by the Court of Appeals (257 F.2d 33) and by the

Supreme Court of the United States (358 U.S. 1). If the

factual situation as found by Judge Lemley, whose fact

findings have never been questioned, were insufficient to

sustain his order, we can see no basis whatever for a rul

ing by us that Act No. 4 constitutes a valid and reasonable

exercise of the police power of Arkansas to meet an

emergency.

“ * * * Every exercise of the police power must

be reasonable and extend only to such laws as are

enacted in good faith for the promotion of the public

good, and not for the annoyance or oppression of

a particular class.” Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S.

537, 550. See and compare, Tick Wo v. Hopkins,

118 U.S. 356.

With all due respect to the considered views of those

Justices of the Supreme Court of Arkansas who concluded

that Act No. 4 represented a valid exercise of the police

power of the State and therefore did not violate the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States, we are firmly of the opinion that Act No. 4 can

not be sustained upon that ground, and is clearly uncon

stitutional under the due process and equal protection

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment, and conferred no

authority upon the Governor to close the public high

schools in Little Rock.

The Supreme Court of Arkansas, in the case of Fits-

hugh v. Ford, Commissioner, ______ Ark. ______, 323

S.W.2d 559, in a unanimous opinion filed on May 4, 1959,

held that Act No. 5 violates no part of the Constitution of

the State of Arkansas, but did not consider whether it vio

lated any part of the Constitution of the United States.

The Court said (page 560 of 323 S.W.2d):

“ In essence, Act 5 provides: (a) It requires the

Commissioner of Education to withhold certain

State Funds (otherwise allocable to a school dis

trict wherein a school has been closed under said

Act 4) in an amount calculated on a certain pro rata

basis, the correctness of which is not challenged

It requires the Commissioner of Education to pay

over to other public schools or non-profit private

schools accredited by the State Board of Education

from the funds so withheld an amount calculated on

a pro rata basis according to the number of students

from the closed schools) attending a recipient

school. Simply and briefly stated, Act 5 provides

that the money which normally would be spent on

a student in a closed school would be paid to the

school which he might later attend.”

Since Act No. 5 is complementary to and dependent

upon Act No. 4, and that Act is invalid, it follows that

Act No. 5 is also invalid and completely ineffectual. We

are satisfied that Act No. 5, as amended, cannot stand

alone and did not, and does not, authorize the State Board

of Education to deprive the Little Bock School District of

State funds allocable to it for the maintenance of its schools

on a constitutional basis, or to divert any part of those

funds to other schools or other districts.*

* Sections 2 and 3 of Act No. 5 of the Acts of the 2nd Extra

ordinary Session of the 61st General Assembly of Arkansas, approved

September 12, 1958, as amended by Act No. 151 of the General As

sembly for the year 1959, approved March 3, 1959, read as follows:

“Section 2. Whenever the Governor shall order any school

to be closed, and continuing thereafter until such order shall

There is no dispute as to the facts. The Little Bock

public high schools were closed by the Governor, under

Act No. 4, on September 12, 1958, before they were opened

for the admission of students, and have remained closed

ever since. The School Board has been precluded, by

the closing of the public high schools, from carrying out

its approved plan of gradual integration ordered into ef

fect by the federal courts.

By virtue of Acts No. 4 and No. 5, as amended, $350,-

586.00 in funds allocable to the Little Rock School District

had been withheld up to May 4, 1959. The total amount

which will be withheld by the end of the 1958-59 school

year, if these Acts remain in effect, will be slightly in

excess of $510,000. Of the funds withheld, $187,768.00

has been paid to other schools, public and private, in ac

cordance with Act No. 5. Of this amount, $71,907.50 was

paid to the private Raney High School.

The total number of prospective high school students

registered for the four high schools in Little Rock as of

September, 1958, was 3,665. Of these, after the closing

of the high schools by the Governor, 266 white students

and 376 Negro students did not attend any school; the

remainder transferred to private schools in Little Rock

and to public and private schools within or without the

State. The evidence shows where the white students went

and where the Negro students went, but we find it unneces

sary to go into that detail.

The purpose, effect, and results of the enactment and

have been countermanded by the Governor, or whenever any

person of school age shall be accepted for enrollment in any

school other than the one in which he normally would attend,

the State Board of Education, acting through its Commissioner

of Education, shall cause to be withheld from the State funds

otherwise allocable to the school district having jurisdiction over

any such closed school, or over any such school which any such

enforcement of Acts No. 4 and No. 5 are too obvious to

require further discussion.

It is the judgment and declaration of this Court: that

Act No. 4 of the Second Extraordinary Session of the

General Assembly of Arkansas, 1958, is unconstitutional

and invalid; that the proclamation of the Governor of Ar

kansas closing the public high schools in Little Rock was

and is void; that Act No. 5, as amended, as a device for

depriving the Little Rock School District of State funds

allocable to it for the maintenance of its schools upon a

constitutional basis, is also unconstitutional and invalid;

that the diversion of such funds pursuant to Act No. 4

and Act No. 5 should be and is hereby permanently en

joined; that the Superintendent of the Schools of Little

Rock, and the members of the Board of Directors of the

Little Rock School District, and their successors, are under

the continuing mandate of this District Court to effectuate

the plan of integration for the public schools of Little

Rock approved by this Court in Aaron v. Cooper, 143 F.

Snpp. 855 (a ff’d, 8 Cir., 243 F.2d 361); and that this Court

has heretofore retained jurisdiction to require the Superin

tendent and the School Board to take such affirmative

person of school age normally would attend, an amount equal

to the proportion of the total of such State funds that the total

average daily attendance of students for the next preceding

school year in the closed school, or in the school which any

such person would normally attend, bears to the total average

daily attendance of all students of the district for said next

preceding school year; plus, and also from State funds, an

amount equal to the same foregoing proportion of ad valorem

taxes collected in the calendar year next preceding the date of

any such closing order, or next preceding the date of acceptance

for enrollment of any such student in the school which he

normally would attend, for the benefit of the said school district

for maintenance and operation; plus, also from State funds,

an amount equal to the same foregoing proportion of all funds

allocable to the school district during the then current fiscal

year from the County General School Fund, all as set forth in

the budget of the County Board of Education.

steps as may hereafter be directed by this Court to ac

complish the integration of the schools of Little Rock in

accordance with and as required by the prior orders of

this Court, and the orders and decisions of the Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit and of the Supreme Court

of the United States,

It is further adjudged that the defendants and their

successors in office be and are permanently enjoined from

engaging in any acts which will, directly or indirectly,

impede, thwart, delay or frustrate the execution of the

approved plan for the gradual integration of the schools of

Little Rock, the effectuation of which has been heretofore

commanded by the orders of this Court.

The motions of the defendants to dismiss the supple

mental complaint, which were taken under submission by

the Court, are overruled.

Dated June 18, 1959.

J o h n B . S anborn

United States Circuit Judge

J ohn E . M iller.

United States District Judge

A xel J. B eck

United States District Judge

“Section 3. Should any of the students of any school so

closed by order of the Governor, or any of students eligible to

attend any racially integrated school, determine to attend, and

attend, in this State, any other public school, or any non-profit

private school accredited by the State Board of Education, then

State funds so withheld as hereinbefore provided, shall be paid

over by the State Board of Education to each said other public

school or accredited non-profit private school in an amount

equal to the same proportion of the total said State funds that

the number of transferred students in any such public or private

school bears to the total number of students upon which said

withholding was made as hereinbefore provided. Appropriations

of funds from time to time made available to the State Board

of Education, including but not limited to those contained in

Act 305, approved March 27, 1957, shall be useable for the

purpose herein provided."

ACT 5, ARK. ACTS OF 1958 (2nd Ex. Sess.)

Approved September 12, 1958

AN ACT to Provide for the Withholding of a Portion of

the State Aid Otherwise Allocable to a School District

During the Period of Time Any School in Any Such Dis

trict Shall Be Closed by Order of the Governor of This

State; to Provide for the Payment from Any Funds So

Withheld to Other Public Schools and Accredited Non-

Profit Private Schools During the Period of Enrollment

and Continuance of Study Therein of Any Students of

Said Schools So Ordered to Be Closed by the Governor;

to Authorize the State Board of Education to Adopt, and

Enforce, Such Reasonable Rules and Regulations Not In

consistent with the Provisions Hereof as it Shall Deter

mine to Be Necessary or Desirable to Effectuate the

Purposes and Intent of This A ct; and for Other Purposes.

Be It Enacted by the General Assembly of the State of

Arkansas:

Section 1. Nothing in this Act contained shall be so

construed as to alter, amend, or in any other manner change

the method of determining the amount of State funds al

locable to the public schools of a county, or of any school

district therein, under the Minimum Foundation Program

Law, or other applicable State aid school law, by reason

of the closing of any school therein by order of the Gover

nor of this State.

Section 2. Whenever the Governor shall order any

school to be closed, and continuing thereafter until such

order shall have been countermanded by the Governor, the

State Board of Education, acting through its Commissioner

of Education, shall cause to be withheld from the State

funds otherwise allocable to the school district having

jurisdiction over any such school, an amount equal to the

proportion of the total of such State funds that the total

average daily attendance of students for the next preceding

school year in the closed school bears to the total average

daily attendance of all students of the district for said

next preceding school year; plus, and also from State

funds, an amount equal to the same foregoing proportion

of ad valorem taxes collected in the calendar year next

preceding the date of any such closing order for the bene

fit of the said school district for maintenance and opera

tion; plus, and also from State funds, an amount equal to

the same foregoing proportion of all funds allocable to

the school district during the then current fiscal year from

the County General School Fund, all as set forth in the

budget of the County Board of Education.

Section 3. Should any of the students of any school

so closed by order of the Governor determine to attend,

and attend, in this State, any other public school, or any

non-profit private school accredited by the State Board of

Education, then State funds so withheld as hereinbefore

provided, shall be paid over by the State Board of Educa

tion to each said other public school or accredited non

profit private school in an amount equal to the same

proportion of the total said State funds that the number

of transferred students in any such public or private school

bears to the total number of students upon which said with

holding was made as hereinbefore provided. Appropria

tions of funds contained in Act 305, approved March 27,

1957, shall be usable for the purposes herein provided.

Section 4. For the purpose of determining the amount

of State funds so to be withheld, and thereafter paid out,

after the date of any such continuing closing order, the

State Board of Education, or the Commissioner of Eduea-

tion, may call upon the Legislative Auditor, the State

Comptroller, or other State officer or employee, to assist

whenever auditorial assistance or advice shall be required.

Section 5. The State Board of Education shall have

the power to adopt, and enforce, such reasonable rules and

regulations not inconsistent with the provisions of this Act

as it shall determine to be necessary or desirable to effectu

ate the purposes hereof.

Section 6. If for any reason any section or provision

of this Act shall be held to be unconstitutional, or invalid

for other reason, such holding shall not affect the remain

der of this Act.

Section 7. It has been found and it is hereby declared

by the General Assembly that a large majority of the people

of this State are opposed to the forcible integration of, or

mixing of the races in, the public schools of the State; that

practically all of the people of this State are opposed to

the use of federal troops in aid of such integration; that

the people of this State are opposed to the use of any fed

eral power to enforce the integration of the races in the

public schools; that it is now’ threatened that Negro chil

dren will be forcibly enrolled and permitted to attend some

of the public schools of this State formerly attended only

by white children; that the President of the United States

has indicated that federal troops may be used to enforce

the orders of the District Court respecting enrollment and

attendance of Negro pupils in schools formerly attended

only by white school children, that the forcible operation

of a public school in this State attended by both Negro and

white children will inevitably result in violence in and

about the school and throughout the district involved en

dangering safety of buildings and other property and lives;

that the state of feeling of the great majority of the people

of this State is such that the forcible mixing of the races

in public schools will seriously impair the operation of a

suitable and efficient system of schools, and result in lack

of discipline in the schools; that for said reasons it is

hereby declared necessary for the public peace, health and

safety that this Act shall become effective without delay.

An emergency, therefore, exists and this Act shall take

effect and be in force from and after its passage.

ACT 151 OF 1959

AN ACT to Amend Sections 2 and 3 of Act 5 of the Acts

of the 2nd Extraordinary Session of the 61st General

Assembly, Approved September 12, 1958; and for Other

Purposes.

Whereas, the Supreme Court of the United States

predicated its school integration decision upon the psycho

logical effect of segregated classes upon children of the

Negro race, and, at the same time, ignored the psychologi

cal impact of integrated schools upon certain white chil

dren who observe segregation of the races as a way of life ;

and

Whereas, legislation is necessary in order to protect

the health, welfare, well-being, and educational opportuni

ties of such white children;

Now therefore be it Enacted by the General Assembly

of the State of Arkansas:

Section 1. Section 2 of Act 5 of the Acts of the 2nd

Extraordinary Session of the 61st General Assembly of the

State of Arkansas, approved September 12, 1958, is hereby

amended to read as follows:

“ Section 2. Whenever the Governor shall or

der any school to be closed, and continuing there

after until such order shall have been counter

manded by the Governor, or whenever any person

of school age shall he accepted for enrollment in any

school other than the one in which he normally

would attend, the State Board of Education, acting

through its Commissioner of Education, shall cause

to be withheld from the State funds otherwise al

locable to the school district having jurisdiction

over any such closed school, or over any such school

which any such person of school age normally would

attend, an amount equal to the proportion of the

total of such State funds that the total average

daily attendance of students for the next preceding

school year in the closed school, or in the school

which any such person would normally attend, bears

to the total average daily attendance of all students

of the district for said next preceding school year;

plus, and also from State funds, an amount equal

to the same foregoing proportion of ad valorem

taxes collected in the calendar year next preceding

the date of any such closing order, or next preceding

the date of acceptance for enrollment of any such

student in the school which he normally would at

tend, for the benefit of the said school district for

maintenance and operation; plus, also from State

funds, an amount equal to the same foregoing pro

portion of all funds allocable to the school district

during the then current fiscal year from the County

General School Fund, all as set forth in the budget

of the County Board of Education.”

Section 2. Section 3 of Act 5 of the Acts of the 2nd

Extraordinary Session of the General Assembly of the

State of Arkansas, approved September 12, 1958, is hereby

amended to read as follows:

‘ ‘ Section 3. Should any of the students of any

school so closed by order of the Governor, or any

of the students eligible to attend any racially into

grated school, determine to attend, and attend, in

this State, any other public school, or any non

profit private school accredited by the State Board

of Education, then State funds so withheld as here

inbefore provided, shall be paid over by the State

Board of Education to each said other public school

or accredited non-profit private school in an amount

equal to the same proportion of the total said State

funds that the number of transferred students in

any such public or private school bears to the total

number of students upon which said withholding

was made as hereinbefore provided. Appropria

tions of funds from time to time made available to

the State Board of Education, including but not

limited to those contained in Act 305, approved

March 27, 1957, shall be useable for the purposes

herein provided.”

Section 3. If for any reason any section or provision

of this Act shall be held to be unconstitutional, or invalid

for other reason, it shall not affect the remainder of this

Act.

Section 4. It has been found, and it is hereby declared

by the General Assembly that a large majority of the peo

ple of this State are opposed to the limitation of attend

ance by students of the public schools of the State to the

schools in which they are now enrolled, or may be eligible

for enrollment; that such limitation of attendance results

in dissatisfaction on the part of students, lack of interest

and effort in their school curricula, and a psychological

impairment of the health and welfare of such students;

that private, accredited schools and other public schools

are more s u i t a b l e for such students than their

resident schools; that the state of feeling of the

great majority of the people of this State is such

that inability to transfer freely to accredited private

schools and other public schools will seriously impair the

operation of a suitable and efficient system of schools, the

psychological well-being of the students, and result in lack

of discipline in the schools; that for said reasons, it is

hereby declared necessary for the public peace, health, and

safety that this Act shall become effective without delay.

An emergency, therefore, exists, and this Act shall take

effect and be in force from and after its passage.

ACT 466, ARK. ACTS OF 1959

Approved March 31, 1959

AN ACT to Amend Act 5, Ark. Acts of 1958 (Ex. Sess.)

Section 3, to Provide for a Return to School Dis

tricts of Surplus Withheld Funds.

Be It Enacted by the General Assembly of the State of

Arkansas:

Section 1. Act 5, Ark. Acts of 1958 (Ex. Sess.) Sec

tion 3 is amended to read as follows:

“ Section 3. Should any of the students of any

school so closed by order of the Governor determine

to attend, and attend, in this State, any other pub

lic school, or any non-profit private school ac

credited by the State Board of Education, then

State funds so withheld as hereinbefore provided,

shall be paid over by the State Board of Education

to each said other public school or accredited non

profit private school in an amount equal to the same

proportion of the total said State funds that the

number of students in any such public or private

school bears to the total number of students upon

which said withholding was made as hereinbefore

provided. Appropriations of funds contained in Act

305, approved March 27, 1957, shall be usable for

the purpose herein provided. At the end of the

school year all funds withheld as aforesaid which

have not been paid over to a public or non-profit pri

vate school accredited by the State Board of Edu

cation, as provided herein shall be released and

paid over to the school district involved.”