Engle v. Isaac Case Syllabus Certiorari

Working File

April 5, 1982

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Engle v. Isaac Case Syllabus Certiorari, 1982. 82a22449-f092-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/22dc5602-f69b-455f-8611-744796babc2b/engle-v-isaac-case-syllabus-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

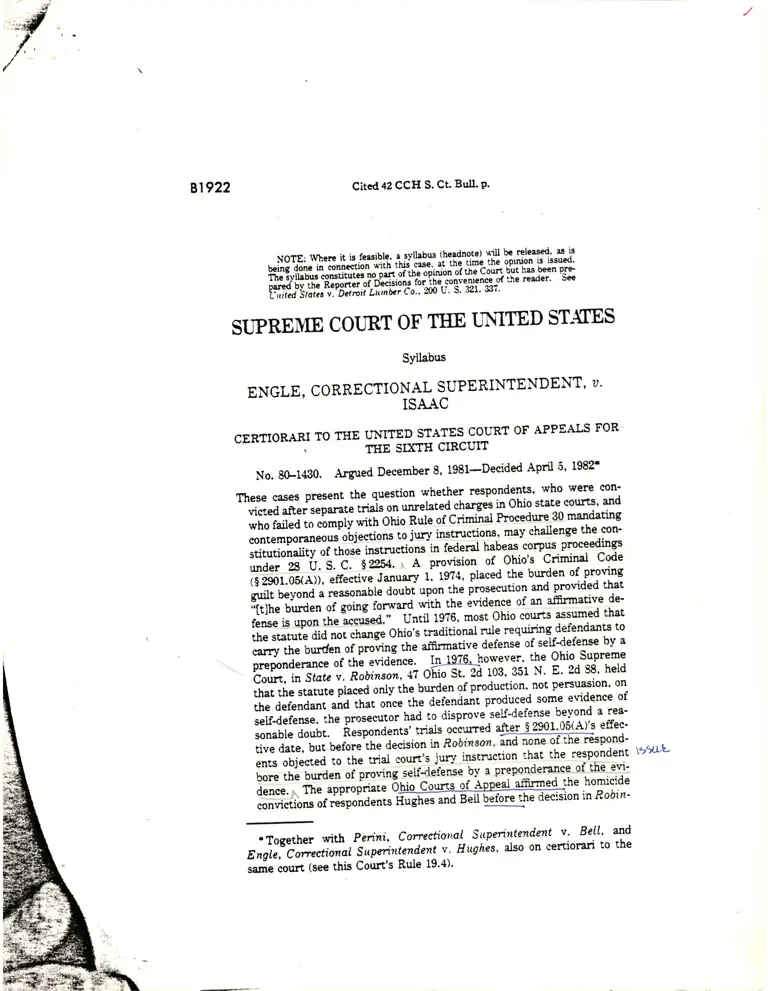

81922 Citcd42 CCH S. CL BulLP.

Hfr lifrt'+l"*:.,ixt:n"'q*l***.lttrt#'':*

SIJPREMEC0I.]RToFTIIEI]NITEDSTIf,ES

SYllabus

ENGLE, CORRECTIONAL SUPERINTENDENT' U.

ISAAC

CERTIoRART ro fIrE

H;r"r&H^;ixu3ff*t

oF APPEALS FoR

No. 8f14i10. &gued December 8' 1981-Decided April i' 1982'

These cases present tlte question whether respondents' who weli con'

victed after..p*,t ii'ion unretatea charges T Ohig state courts' and

who faited tn **pty*iil-Od" nG of Crimiiral Procedure 30 mandating

contemporaneous oUjeciions to jtrry instmctions' may chdlenge the con'

stitutionalityortirosi.*rinr.tiJ*"inr"dgdhabeascorpusproceedings

under 28 U. S. C' $;A:-'-'l' p*-1"ion of Ohio's Crimind Code

($ 2901.05(A)1, effe"U'eTanua y l' tSll' placed the burden of proving

grriit beyond

" ""r"oitUf"

aooUf opon the irosecution and provided that

"ttlhe burden or goi,['io;-J *t-n^:lt toid"ntt of an affirmative de'

fense is upon the *GJ'" Until 1976' most Ohio courts assumed that

t,e ststute did not;;; ohio;s tmdiuonal nrle requiring defendants to

carry the burden ,iil";;'ile affirmative defense of self<lefense by a

;;;;;" or tr'i'."1a-tl"*, p:+q however' the ohio Supreme

court, in stotc r. ;il;;;:-4? o-h6-sL-2i tog'.351 N' !: '1-T'

n"to

,h;th" statute pucJ onty the burden of production' not persuaslon' on

the defendant

"na

iiiioi." ti," a"r"naant produced some evidence of

selfdefense.trrep,osecutorhadtoclisproveseif.defensebeyondarea.

sonable doubt. nt'poia"ntt' rrials occrr:red after S 2901'05(A)'s effec'

dve date, b"r bef.;"ffi;;;i.ion in ioatrron. ild noneiltfre Esoond-

ents objected to tr," uiJ toun't jory i*t*ttion that the

"'pond"nt

\''NtL

bore the br.rden .ip"i"i"g '"if*r"ft*"

by a prepo-nd"qt: of the evi-

dence. r I'he approJ#'6i"' i""t 9f iP'9"1-'m{ jhe 'homicide

Hir*..\,i. if ['.,ffi;;=

-r@!s.ion in R o bi n'

'Together with Panni, Coneetiotr'al-Syprintend'mt v' Bell' znd

Enole. Cotectional s,-ini"i'iaiii v' Hughes' also on certiorzri lo the

."-" *ort (see this Court's Rule 19'4)'

citcd 42 CCII s. ct. BuII. p.

81923

ENGLE ?r. ISAAC

Syllabns

p,rTe co,,n au*'#e or-c-ril,ii $"ffilffi# lf*3.ir,*

#t"ffi sr#ffi#Hffi H#"frrffi:#ffiI

1. Iasofar eq F.tu-r-_- ,

-.'gt

' h) Tta

.ro'"tr*l*"grJfit:ffi,ffiig*ffi ii'E-

[J*: th" p-.*,rtion to prove

"

r^g-o', '1iliffi?on

to pttee

I sonable doubt

[-elernent*,n"*11o'o,d---''"iitf31T-d"'ffiTi:fj"'f

;x#iIffi,:*

t'-rz - --

::"

ror ,ne purpoee, it must a;J'i",

"il'J,rH:r::{i

,""d1Lif;:"rJf#t'IT3;#":HI"x:Ttry,*"*"rs,arju.

agairrst thea ol

n*-,ri,,r"*xfl*"ffi *;_ry#t"[:t*=n*l

ffi2. Respondent"; h:-T'l

Ptoeedinss, *"1T ?Fs &om asse

ffiFtrm*r*H,(a) Mrile the-crrit rllur" clrput is a bujwark"*_r;;;J

{

\

::.!:=ij

@

81921 Cited 42 ccH S. Ct. ButL P.

ENGLE U. ISAAC

Syllabus

that violate *fundamental ftrir1ess," it undermines the rxual principles of

erraitv of litiEation Liberal allowance of the writ also degrades the

p-iio"n." oittr" tri"t and costs society the right to punish admitted of-

i"oa"r.. Moreover, the writ inposes specid costs on the federal sys-

t"-, tort =tirrg

both tlre states' sover.eign power to purish ofrenders

;d th"jr gooalfaittr attempts to honor constitutional rights. These

costs are p-articularly higtr when a trial default has barred a prisoner

from obtaininS adju the stste eourts,

and tlrus, as triU @Av. Sykes, S E f-3}state prisoner,

hared hv nroced nd claim on SI9S. nr<{ barrcd bY Pr

Q?w"' ,ffii,Hl

ciAim in z lDil habeas cor?us proceeding

. ffit .r,o#c d." for and accual preiu!1i99-.lEp4$eighgLt' Ttre

, I oritt"ioi"s of SuirSE tG limitttrIo6tin which che constiiutiornl

aJ-ilV \ lr-r Aa not aifect ttre ffitmnaing tunction of the trial Pp. 1?-21.

o- ' ' -- -

O) C",rse for respondents' defaults cannot be based on the T::"ttd

ground that any objeition to 0hio's selfdefense instnrction wouid have

6een futile sincl Ohio had long required criminal defendants to bear ttre

burden of proving such affrmative deferue. If a defendant perceives a

viable eonstitutiona .uirn and believes it mey ffnd favor in the federal

.o,r"t , he rnay not blaass-the st:te corrrts simply becar:se he thinks they

*lu u". *"r*pettretic to the claim- Nor can cause for respondents' de-

fauits L based on the asserted ground that they coqld not have koown at

the time of their trials that the DuqPlocerglQlarryglddr$se$he burden

.i p-tinJ .mtt*.ir. a.a.*".. @99:9d

four-andinebalf yean beforne tEEE[-oI respondents' trials, laid lhe

basis for their constitutional claim. Dr:ring the ffve years following tlat

a""irion, nurlerous defendants relied upon whxhip to argue that the

Due Process Clause requires the proseortion to bear the burden of dis.

p-"i"S certain afrrmative defenses, and several lower courts sustained

thi, d;-. In light of this activity, it cannot be said that respondents

lacked the tools to constnrct their constihrtional claim. Pp. 21-25.

(c)Thereisnomerittorespondents,contentiontharthec?us-e.-*d.1.

prejudice standard of Sy&es should be replaced bu a pl{I={H* " PUAUn' 2,RR0f<

l\Itrile fedeiil cor6s aflfilIa plain-eror nrle for ciirect review of

convictions, federal hablas chailenges to state convictions entail greater

fln8ury problems and special comity concerrul. )Ioreover. a plain'eror

standard is rrnnecessary to corTect miscariages ot' justice- Victims of a

fundanenal miscarriage of jr:stice will meet the cause-and'prejudice

--st:ndard. W.zf-ln.

\ em f. 2d 1129 (f:st case);$5 f. 2d575 (second caseX and elz F. 2d

'151

\ tttrira case), rcversed and remandeo-

I

cited 42 ccH s. cL BulL p.

ENGLE a. ISAAC

Syllabu

OtComlo& J., delivcnd the opiuioa of the Court, in which Buncca, C.

J., snd nrryr" PourEu{ rnd Rpmnust, .LI., joined. Bl.rcwtnr, J.,

concortrd ia the result" StrE\rENs, J., filed aa opinioo conorring in p8rt

aad di$enting iD part. BBEI.otAlt, J., f,led e dissenting opinion, in which

Mersrru, J., joined.

81925

81926 Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

SI]PREME COT]RT OF THE T]NITED STdf,ES

No.8L14il0

fED ENGLE, SUPERINTENDENT, CHILLICOTHE

CORRECTIONAL INSTITUTE, PETITIONER, U.

LINCOLN iSAAC

ON WRTT OF CEBTIORARI TO TIIE UNITED STATES COUBT OT

APPEALS FOB TIIE SDffII qIRCUIT

lApril S, 19821

Jusncp O'corNon derivered the opinion of the co,rt.

lnWairunightv. Sykes, 4gB U. S. T2 (lgTI), we heid that a

state prisoner,

-barred by pege$dJefad! from raising a

6onsii-tuuonar ciaim on dir;cmor iirigace ciac

n,,*lW T . $ ?.2-fu1hab.eas corpus, proceeding withouishowing

Y F^"Jor. and agtual prejudice from the default. Applyurg- the principle o at riiponal

ents, who failed.to comply with an 0hio nrie mandatinf con-

temporaneous objections to jr:ry instmctioru, may nqt chal-

lenge the constitutionaiity of those instmctions in .T.a.or

habeas proceeding.

I

Respondents'claims rest in part on recent changes in Ohio

siminal law. For over a century, the Ohio courtls required

criminai defendants to carry the br:rden of proving r.lf-d.-

'Tltle 28 u. s. c. $ 225a(a) empowe!'s "[t]he supreme court, a Justice

thereof,

-a-cqcuit

judge, or a district court" to "entenain an appiication for

a writ of habeas cor?us in behalf of a person in custody.pursuant to thejudgment of a state court only on the ground that he is in custoay in viola-

tion of the constitution or laws or triaties of the united state;.,' ThiE

statutory rcmedy may not be idendcal in all respects to the eomrnon-law

writ of habeas corpus. SeeWainutrightv. gyl62j, {Sg U. S. 72, Zg (19m.

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

fense by a preponderance of the evidence. See Sfate v.

Seliskar, SS Ohio St. 2d 95, 298 N. E. 2d582 (1973); Szalkai

v. State,96 Ohio St.36, 117 N. E. 12 (1917); Siltrusv. State,

22 Ohio St. 90 (1872). A new criminal code, effective Janu-

ary 1, 19?4, subjected ail affirmative defenses to the follow-

ing rule:

"Every pet'son accused of an offense is presumed inno-

cent until proven guiity beyond a reasonable doubt, and

the burden of proof is upon the prosecution. The br:r-

den of going fornnrard with the evidence of an afrrmative

defense is upon the accused." Ohio Bev. Code Ann.

s2e01.05(A) (1975).

For more than two years after its enactment, most Ohio

courts assumed that this section worked no change in Ohio's

baditional burden-of-proof nrles.z in 1976, however, the*

Ohio Supreme Court constnred the statute to place only the

burden of production, not the br:rden of persuasion, on the

defendant. Once the defendant produces some evidence of

selfdeferse, the state court nrled, the prosecutor must dis-

prove seifdefense beyond a reasonable doubt. State v. Rob-

inson,47 Ohio St. 2d 103, 351 N. E. 2d 88 (1976) (syllabus by

the conrt).r The present actions arose because Ohio tried

'|See, !. 9., State v. Rogen,4i! Ohio St. 2d 28, 30, 330 N. E. 2d 874, 616

(1975) (noting that "selfdefense is an affrrnative defense, which must be

established by a preponderance of the evidencd), cert. denied, 42i, U. S.

1061 (1976). But see Stote v. Matthc,ps. No. 7,LAP-128, p. 9 (Ct. App.

Franklin County, Ohio, Dee. 24, 1W4) ($ 2901.05(A) "evinces a legislative

intent to change the burden of the defendant with respeet to affirmative

defenses'); I O. Schroeder & L. IGtz, Ohio Criminal Law and Practice

$ 2901.05, p. 14 (1914 ed.) ('The provisions of 801.05(A) follow the modera

stahrtory trend in this area. requiring the accused to raise the affirmgcive

defense, but leaving the brlrden ot'persuasion upon the prosecution.'); Sfu-

dent S:rmposium: The Proposed Ohio Crimind Code-Reform and Regrer

sion,33 Ohio St. L. J. 351, 120 (1912) (suggesting that legislators intended

to change hraditional rule).

'Iu Ohio, the eorfi's syllabus contains tlte controlling law. See Ifaas

81927

B1 928 circd 42 ccH S. Ct. B|JL p'

ENGLE u. ISAAC

ard convicted respondents tfttl the effective date of

;frl.G(A), uot u"Iot the Ohio Supreme Cotrt's interpre-

;6; of that statute in RoAinson''

0n December t6,- Lii:an Ohig grand jury indict* t*

soondent llughes'it;-;&;;atea iuraer'' At trid the

3ffi;=ilr;;-Gt, io i[" pr.."nce of seven witnesses,

ffi;.; ;;;;d Hii.J; trl- *ho *" keeping companv with

his foruer gi"ffi."J' Prosecution witnesses testified that

the victim *.. *tiuti-*a U"a just attempted-to. shake

hands with llugh;'

--H'ghts'

ho'wever' claimed that he

acted in setfdefeile'

-Efi

testinony suggested that he

feared the victim,;Lg; *-' becauie trJtraa huched his

pocket while "ppiili"g -tt'qU*' The trial court in-

structed tUe :ury'tlat ffigfrttio"t the br:rden of proving

v. Stntz,103 Ohio SL 1, ?-8, 132 N'

-P..

lfl' f59-160 (1921)'

'Two years .no f'att-L' tf'" Ohio legislature once again amended

Ohio's butdeo'of'p"oor ii*]- ift" n"* $ 29O1-'05(A)' efrective November 1'

19?8, Provides:

'Every Person accus€d of an offense is presuned innocent until proven

nrilty beyona

"

r.r"o*Ui" a"tUt' *a tne Uuraen of proof for all elements

of tJre offense is upon;;;-#d"* The burden or going forward wittr

the evidence of * .rntrn"f,* atft*"'- o'a Uu htd'€rl of poof' W o W'

oonlcr*cc of ttn o'tiil',-f* - "h"*"tite

defense' is upon t,'e ac-

fi#."-'-o#"

-i;;. ;;;' e""- Ezsor'06(A) (supp' 1s80) (emphasis

added.

lhisamendmenthasnoefiectonthelitigationbeforerrs.Thaughoutthis

ooinion. citations to $&;diAir.ro to-rhe statute in effect betweenJan-

** eil"n'#f. 3ff"%11' u'ffii. o, ( 1nE):

"(A) No person ,h"lj;fi;iy, *a *itt prior caiculation and design'

cause the deeth of another'

"(B) No pen on *n uiilo."ly eause the death of another while commit'

ting or attempting r" .;fr*i.r while fleeing immediately after commit-

ting or attempting to *ti*ii kidnapping' rape' aggravated arson or arson'

aggrzvated robbery ot-'UU""y''agglavated burghrT or burglary' or

*f,6'*"-"1*,"i"1::.*:ffi

;1#'r;t."rtff fi*St5::,,-o

.f"if-U" p*:hed as provided in section 292!

Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. Bult. p. 81929

ENGLE u. ISAAC

this defense by a preponderance of the evidence. coursel

for Hughes did not specifically object to this instnrction.6

On January Zl, 1975, the jury convicted Ilughes of volun-

tary-manslagghter, a lesser included offense of aggrzvated

murder.T On September Zl, 1g?8, the Sumrnii County

Cg"t of Appeals affimed the conviction, and on March 1g,

197-6, the Supreme Cor:rt of Ohio dismissed Hughes, appeal,

finding no substantial constitutional question.r- Neither of

these appeals cballenged the jnry instruction on serfdefense.

_ ^otrio

tried respondent Bell for aggravated mtuder in Aprii

1975. Evidence at trial showed that Bell w:ui one of a group

of bartenders who had agreed to help one another if tr-oubll

developed at any of their bars. On the evening of the mnr-

der, one of the bartenderp called Bell and told him that he

feared trouble from five'men who had entered his bar.

'[Vhen Beil arrived at the bar, the bartender informed him

that the men had left. 'Bell pursued them and g:unned one of

t}le men down in the street.

Bell defended on the ground that he had acted in selfde-

'Hugires' connsel did reg,ister a genenl objection "to t}e entire charge

in its entirety'because "fw]e are operating now under a new code in which

nany things ane uncettei[" App. 4E. esrrnsst's subsequent remarks,

however, demonstrated thst his objeetion concerned only the pr.oposed def-

initions of "Aggravated Murder, Murder and vohurtary Mansiaughter.',

App.4l,50.

'voh:atary manslaughter is "howingly car:s[ing] the death of anothe/,

while under'exttreme emotional stress brougirt on by serious provocation

rcasonably srrffcient to iDcit€ [the Defendant] into using deadly force.,'

Ohio Rev. Code tuin. $ 290S.0B (A) 09ZE).

Hughes was sentenced to 6-25 yeas in prison. The state's petition for

ceniorari indicated that [Iughes has been "granted final releas[e] as a mat-

ter of parole." Pet. for cert. 6. This release does not moot the conrro

1grsl_between Hughes and the State. See Humptvq v. Cady,405 U. S.

504, 5O&Sryz n Z (J;972); Co;rufas v. LoVallee, Bgr U. S. 234, g7_z4}

(1968).

_

I See- Stnta v. Huglus, C. .L No. nfi (Ct. App. Surnmit Counuy, Ohio,

Sept. 24, f975); Stats v. Hughes, No. 2L1026 (bhio, March tg, tgZ'Ol.

Bl 930 cited 42 ccH S. Ct. BuiI. p.

ENGLE 0. ISAAC

fense. He testified that as he approached two of the men,

the bartender shouted: "He's got a gun" or "\Match out, he's

got a gur." At this warning, Bell started shooting. As in

Hughes' case, the trial corrrt instnrcted the jr:ry that Bell had

the.burden of proving selfdefense by a preponderance of the

evidence. Bell did not object to this instnrction and the jury

convicted him of murder, a lesser inciuded offense of the

charged crime.e

Bell appealed to the Cuyahoga Corurty Court of Appeais,

but failed to chailenge the instnrction assigning him the bnr-

den of proving seifdefense. The Court of Appeals affirmed

Bell's conviction on April 8, 1976.'0 Beil appealed further to

the Ohio Supreme Corrrt, again neglecting to challenge the

selfdefense instnrction. That court overnrled his motion for

leave to appeal on September 17, 1976,'r two months after it

constnred $2901.05(A) to place the br.uden of proving ab-

sence of selfdeferu,e on the prosecution. See Sfate v. Robin-

gtn, $/,pta,.

Respondent Isaac was tried in September 1975 for feioni-

ous assault.tr The State showed that Isaac had severely

beaten his former wife's boyfriend. Isaac claimed that the

boytiend punched him first and that he acted solely in self-

defense. Without objeetion fi&n Isaac, the corrrt instnrcted

'Ohio defnes mnrder as 'lurposeiy caus[ingJ the death of another."

Ohio Rev. Code tum. $ 2903.02(A) (1975). Beil received a sentence of 15

years to life imprisonment.

'ostll;te v. Bell, No. 347?7 (Ct. App. Cuyahoga County, Ohio, April 8,

1yro.

" Stata v. Bell, No. 76-573 (Ohio, Sept. 17, 1976).

uSee Ohio Bev. Code Ann. $2903.11 (1975):

"(A) No person shdl knowingiy:

"(1) Cause serious physical harm to another;

"(2) Cause or attempt to cause physical harm to another by means of a

deadly weapon or dangerous ordnance as defined in section 2923.11 of the

Revised Code.

"(B) Whoever violates this section is Cuilty of felonious assault, a felony

of t}te second degree."

cited 42 ccH S. Ct Bull. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

the jury that Isaac erried the burden of proving this defense

by a preponderance of the evidence. The jury acquitted

Isaac of felonious assault, but convicted him of the lesser in-

cluded offense of aggravated assault.E

Ten months after Isaac's trial, the Ohio Supreme Court de-

cided State v. Robin^son, supru^ In his appeai to the

Pickaway County Court of Appeals,t' fsaac relied upon.Rob-

irxott to chdlenge the burden-of-proof instnrctions given at

his trial The court rejected this challenge because Isaac

had failed to object to the jnry instntctions during trial, as

required by Ohio Ruie Crim. Proc. 30." This default waived

o Ohio Rev. Code Ann. $ 403.U (19?O describes aggravated assault:

'(A) No person, while under extreme emocional stress brought on by se-

rious provocation reasonabiy su.fEcient to incite him into using deadly foree

shdl loowingly:

"(1) Cause serious physrcal harm to another;

"(2) Cause or attempt to cause physical harm to anotier by means of a

deadly weapon or dangerous ordnence as defined in section 823.11 of the

Revised Code.

"(B) Whoever vioiates this section is Suilty of aggravated assault, a fel-

ony ot'the for:rth degree."

The judge sentenced Isaac to a term of six months to five years imprison-

ment. According to the State's petition for certiorzri, Isaac has been re

leased from jail. This controvesy is not moot, however. See n 7, supro^

"Stat2 v. Isou, No. 346 (Ct. App. Pickaway Counry, Ohio, Feb. 11,

LWO.

'' At the time llughes and Beil were lried, this ruie stated in rrelevant

part:

"No party may assign aa ern)r any portion of the charge or omission

therefrom unless he objects thereto before the jury retires to consider its

verdict, stating specificdly the matter to which he objects and the grounds

ofhis objection. Opportunity shall be given to make the objection out of

the hearing of t}re jury."

Shortly before IsasCs trial, Ohio amended the language of the nrle in minor

respects:

"A party may not assiga as enor the gling or the failure to give any

instrrrctions unless he objects thereto before the jury retires to consider its

verdist, steting specifically the matter to whidr he objects and the grcunds

B1 931

(

Bl 932 cited 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

ENGLE U. ISAAC

Isaac's claim. State v. Glaros,l?0 Ohio St. 471, 166 N. E.

2d379 it960); State v. Slone,45 Ohio App. 2d 24, U0 N. E.

2d Atg (1975).

Ttre Supreme Corrrt of Ohio dismissed Isaac's appeal for

lack of a substantial constihrtional question.'6 On the same

day, that cor:rt decided State v. Humphries, 5L Ohio St. 2d

95, 364 N. E. 2d 1354 (1977), and, State v.'Williams, 51 Ohio

St. 2d L12,3U N. E. 2d 13&1 Qgm, vacated in part and re-

manded, 438 U. S. 911 (1978). ln Humplwies the court

ruied that every criminal trial held on or after January 1,

19?4, 'ts required to be conducted in accordance with the pro-

visions of [Ohio Rev. Code Ann. $2901.05]." Id., at 95' 364

N. E. 2d, at 1355 (syitabus by the court). The cor:rt, how-

ever, r€fused to extend this nriing to a defendant who faiied

to comply with Ohio Rule Crim. hoc. 30. Id., at 102-103,

364 N. E. 2d, at 1359. In Williams, the cotrrt declined to

consider a corstitutional challenge to Ohio's traditional seif-

defense insh'trction, again bgcgus-e tle lgf-endant had not

plgp_elly objected to the instmction at trial.' Atl afu"e- respondeirts unsuccessfully l6-ught writs of ha-

beas corpus from federal district courts. Ilughes' petition

alleged that the State had violated the Fifth and For:rteenth

Amendments by failing to prove guilt "as to each and every

essential element of the offense charged" and by failing to "so

instnrct" the jury. The District Judge rejected this claim,

finding that Ohio law does not consider absence of selfde-

fense an element of aggravated murder or vohutary man-

slaughter. AJthough the self-defense instnrctions at

Ilughes'trial might have violated $2901.05(A), they did noc

violite the federal Constitution. Alternatively, the District

ofhis objection. Opportunity shall be given to make the objection out of

the hearing of the jury."

Both veniorx of the Ohio ruie ciosely parallel Rule 30 of the Federai Ruies

of Crimind Procedure.

" Stntc v. Isorc, No. 77-112 (Ohio, July 20, LWl).

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. BulI. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

Judge heid that Hughes had waived his constitutional claim

by failing to compiy with Ohio's contemporaneous objection

rule. Since Ilughes offered no explanation for his failure to

objeet, and showed no actual prejudice, Wairuni4ht v.

Sgkes,433 U. S. 72 Qgm, barred him from asserting the

claim. Hu4hes v. En4le, Civ. Action No. C77-156A (N. D.

Ohio, June 26, 1979).

Bell's petition for habeas relief similarly aileged that the

trial judge had violated due process by instnrcting "the jr:ry

that the accused muiit prove an af0rmative defense by a pre-

ponderance of the evidence." The District Court acircnowl-

edged that Beil had never raised this ciaim in the state

conrts. Observing, however, that the State addressed Bell's

argument on the merits, the District Court nried that Beil's

defauit was not a "deliberate b1ryass." See Fay v. Noia,372

U. S. 391 (1963). AJthough the court cited our opinion in

Wain night v. Sykes, supra, it did not inquire whether Bell

had shown cause for or prejudice from his procedural waiver.

The cotrrt then nried that Ohio could constitutionally br:rden

Bell with proving selfdefense since it had not defined ab-

sence of selfdefeffle as an element of murder. Bell v.

Perini, No. C 7&34i1 (l-i-D. Ohio, Dec. 26, 1978).

Bell moved for recorEideration, urgrng that $2901.05(A)

had in fact defined absence of selfdeferuie asi an element of

murder. The District Cor:rt rejected this argurnent and

then declared that the'teal issue" was whether Bell was en-

titled to retroactive application of State v. Robinsan, supra.

Bell faiied on this claim as well since 0hio's decision to limit

retroactive application of R o bin s oza "substantially furth er[ ed]

the State's legitimate interest in the finality of its decisions."

App. to Pet. for Cert. A59. Indeed, the District Court

noted that this Court had sanctioned just this sort of limit on

retroactivity. See Hankerson v. Nqrth Carolina, 432 U. S.

?-33,244 n. 8 (1977). Bell v. Psrini, No. C 7&343 (N.D.

Ohio, Jan.8,1979).

Br 933

/

./

Br 934 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. BulI. p.

ENGLE U. ISAAC

Isaac's habeas petition was more complex than those sub-

*iii.O UV Hughes and BelI. He r:rged that the.Ohio Su-

|,."il Corrt f,ad ,failed to give ryli9f [to him], despite its

own pronouncement,'that state v. Robinsqn would apply_ret-

*".fir.ty. In addition, he declared broadly that the Ohio

court's tifing was "conttrary to the Sgn1e-me 9:'l of the

united State-s in regard to proving selfdefense." Ttre Dis-

trist court detemrined that Isaac had waived any constitu-

tiona chims by failing to present them to the ohio trial

corrrt. since iri n:rttrei faiied to show either cause for or ac'

i"J p".l"dice from the waiver, see wairutrright u. sykes,

,upi, hL couid not present his 9laim in a federai habeas pro-

..iiai"g. Isaacv. En4le, Civ. Action No' C-2-7*n8 (S' D'

Ohio, Jr:ne 26, 1978).- -Tlr.

Court of Appeals for the llxth Cireuit reversed ail

th-r; District Couii orders. ln Isaac v' En4le,649 I'' 2d

rugtceo1980),amajorif,yoftheenbanccorrrtnrledthat

Wil"r*igntv. Sykes did not preclude consideration of Isaac's

constitutlonal ctaims. At the time of Isaac's trial, the court

noted, Ohio had consistently required defendants to prove af-

flrmative defenses by a prepondirance ofthe evidence. The

tudlttt of objeeting [o this Lstablistred practice supplied ade-

qo"t"".ro.e for Isaac's waiver. Pfstlqtg' the.second pqe-

r-e.qqi9ile for excusing a procq{g1{. default, was "cleay'' since

iiiJ'U-ora"n of proofis a critia;a elemeni of factfinding, and

since Isaac had made a substantial issue of self-defense. Id.,

at 1134.

A majority of the court aiso believed that the rgglp1c-tigqs

grven ,i I.L.'t trial S-olated due-. process. -Fog

judges

[hought that $ 2901.05(A) defined the absence of selfdefense

"t "i element of felonious and aggravated assault' lYhile

the state did not have to define its crimes in this manner,

,,due process require[dl it to meet the burden that it chose to

....,-"." &16 F. 2d, at 1135. A fifth judge believed that'

even absent $ 2901.05(A), the Due Process Clause wouid com-

l

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct' Bull' P'

ENGLE U. ISAAC

pei the prosecution to prove."Pttnt: of seUdefense because

that defens" n"grttt-&'i"al intent^' an essential element of

##j1#['.:'lSHertl;-L'xl,rtl:ffi*.^;l;:

concentrzted 6n ttt-t Sttt"'t oUit""y tin'""t to extend the

retroactive uenents"ofIiiti i' nourllt*' slt'Pra' to lsaac''?

Betying on the ;;;ffitisit" i" Isaac' two Sixth Circuit

oanels ordered the District Cor:rt to release Bell and l{ughes

iti".. the State ;;;1; itttl-gt* within a reasonable

time. BetL v. P;;, tr;; r' zq 5?5 (ca6 tg80);E Hu4hes v'

Ensle,judgrnent #;t *p;ned a1.&rz F' 2d 451 (CA6 1980)'

We eranted certio#;;;; a1l t]rree Sixth Circuit opin-

ionsl 4S1 U. S. 906 (1981).

II

Br 935

i"r.Yr?":r',T"lilffi ilii*tion"r.r"i*..Respondentsrepeat

both of those claims here'

A state prisoner is entitied to- ro]ief under A U' S' C'

lnl|only- if he is #d "i";"ttdy -in

violation of the Con-

stitution or laws o"'tiiiG tr *t Ut'it{ ::1'"t"t:, .ly:iil

f'l$:.la'.;il:#r', It"['ng' t!3 lnectness

of the se]f-

defense instmctio# ffi;Offi h*'.Iffi

f,:TH:rffiffiffiilJi'v'ot obtfr-habeas rerier' rhe

lowercourts,ho*.;;;'r.;re.sno1d{t:h^1113:::'ilt#"l:

A

First, respondents argue that.$2901'05' which governs the

br:rden of proof i"

'11

;"*i"d t"iult' implicitly designated ab-

sence of self-defe;; ; element of'the

-crimes

charged

"The latter anaiysis paralleled the reasonrnl

decided rhe case. s"""fio]r ,.- i'iii, ua rlza trz (cA6 1980)'

Four memben or ti'e tllt iitt"ittta from the en banc opinion' Two

judges wouid have rt*i 'il

i""tii*lonal vioiation and two wouid have

bared coffiideratlon ti[;';J-"; undet.wainunight v' Sykes' suqra'

uone iudqe ai"r"ntJil'iii,i, a."i"ion, indicating th*wainutight v'

Satcis,;W, barred Bell's ciairns'

B1 936 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. P'

ENGLE u. ISATIC

against them- Since Ohio deflned its. crimes in this manner'

resDondents conte;;,".-* o6o-* it In re Winslvip' 39?

u.'S. 358 (1e?0); ii""iti''w i'- Y:W,' a!

-U.;^s:6s4

(-1e7il'

znd, PatteraCIn v. iti'i'itt, 432v' s' rgz (19'm' required

the prosecution to'pio"'"it"ntt of selfdefense beyond a

reasonable doubt. "A;i*iit oi-trtt en banc Sixth Circuit

;ffiffi....ni tr*

"Ig'1ttnl

it' lt""t's appeal' frnding that

due proces. ,.q*&it'? st'tt "to.meet thl btrtdet' that it

J#;;;"m;-" 646 F' 2d, at 1135'

A careful review;i; 0"t". decisions reveals ttrat this

.t"i. i. without *ttii'; Orii opinions.tmff:tffr3#;;

ecudorfs constitutional duty to nega

may depena, .t rll"Ii'i p-in o"^[ne manner in which the

State defines rrr.."iil"gJa ;ti-;' C-ompare Mullaney v' Wil'

w, sttyra. with ;'fr;;;;n'ii*i*L' tup'o" These deci-

sions, however, aJ-lgl toggest that whenever a State re-

quires the prosecuti6f, to prove a oarticular circumstance

beyond

"

r.r"o*[it;;d''ii rt'" in''oi"biv defined that cir-

cumstance asl an.ft"t"'i-Jthe crime' A State may want to

assume the burd;oi ai'p"o"ing.^" 3f6mative

defense with-

out aiso aesigna#;il;t; ;f-the defense an element of the

crime.P rrr. poJ il;I.e.JJ cr"*" does not mandate that

,'TheSteteSugg€ststhatt}reineffectivenessoft}risclairndemonstrates

that respond"nt" ,uff"r"f,;;l,cil; p*Judice from iheir procedural de'

fauit. We agree t}at ttt" tf*" L intt'ingt"1t io support habeas relief' but

do not czt'egoize*,i" i*G--e-.l"tc * t l1k ol prejudice' If a state pns-

oner alleges oo a"p;'"tioi ti" it"*r "ght'

$ bs+ is simply inapplicable'

It is unnecessary in t"ii i titl-uti to iiquire whether the prisoner pre

r"*.a his claim before the state courts'

'Definition or "

oit"iJtr"*"iit'*v-have consequences under state

law other than allocatio;;il;"den of^persuasion'- For example' the

ohio Supreme court;;;;;il $2901'0'5(A) to require defendants to

come for.rard with *rrH;ffi;oi'm"*tlut defenses' Slote r" Robin'

son. 47 ohio St. 2d l0; ;;ii' i'

'z;

as trsro)' Defendants do not bear

#'.1;;il;;;;'h;t;;ect to the elements of a crime; the state must

orove tlose elements b:;"tffi;";;t1; do'bt

"u"n

when the detlendans

inaoduces no evidence'

'i*'

''

g" Statev' Isau'{4 Ohio Misc' 87' 33? N'

50 LW 43BO The llnited Srares LAW WEEK 4-6-82

when a State treats absence of an afflrmative defense as an

"element" of the crime for one pur?ose, it must do so for all

pur?oses. The stmcture of Ohio,s Code suggests simply

that the State deeided to assist defendants by requiring ifrl

prosecution to disprove certain affirmative defenses.

-Ab_

sent concrete cvidence that the Ohio Iegislature or courts un-

derstood $2901.05(A) to go further than this, we decline to

accept respondents' constmction of state law. While they

attempt to cast their first claim in constitutional terms, wL

believe that this clairn does no more than suggest that the in-

structions at respondents' trials may have violated state

law.rr

B

, Respondents also allege that, even without considering

$2901.05, Ohio could not constitutionally shift the burden oT

proving self-defense to them. All of the crimes charged

against them require a showing of purposeful or knowing-be-

havior.- These terms, according to reipondents, imply I de-

gree of culpability that is absent when a person acti in self_

defense. See Committee Comment to Ohio Rev. Code Ann.

$2901.21 (1975) ("generally, an offense is not committed un_

less a person . . . has a certain guilty state of mind at the

titae+t@t-€.IfuBZ.Ohio

App 2d ?&, ?flf-2f,7, 290 N. E. Zd g2L, gn O}TZ) (i onodho

kilh in seff-defense does so without the mens rea ti6tnei-

sions- adopt respondents, reasoning that due proeess com-

mands-t\e prosecution to prove absence of selfdefense if that

d.efenge ntgaqes an element, such as prr"aq"fui.-;rd;i;';i

the charged cibmq While other courts )rirfejected lhis

type of claim,a thti'co4roversy sugg!.6.that respondents,

second argument stateb.at leatr{- plausible constitutional

claim. We proceed, thgrd?6.r.e. to determine whether re-

spondents preserve&tfifs' claim the state courts and, if

not, to inquirp-rdiether the principlN.articulated n Wain-

y\ght yfrkes, supra, bar consideratiN.qf the claim in ar?W*t_t:"q_l9ile." :\

fynn u. U ononry, An F, Zdg f Cffi

CommonweaLth v. Hilberl,4?6 pa. 2gg, g8Z A. 2d 724 (1978). 'See

also

Comment, l1 A.lnon L. Rev., supta n. 22; Note, ?g Colum. L. Rev., supra

[',

i

,'- ,.

\ f.

, r\, ,'

Simon, No. 6262, p. 13 (Ct. App.

Jan. 16, 1980), modified on recc

_" !.,, C artet v. J ago, 687 F. 2d Ug (CA6 1980); Bak* v. Muncy, 6t9

F. 2d 32? (CA4 1980). See also Lelond, v. Oregon, ilLl U. S. 290 fi952)(rule requiring accused to prove insanity beyond a reasonable doubt does

not violate due process).

5 JusTrcE Bnnxxuv accuses the Court of misreading Isaac,s habeas pe-

tition inorder to create a procedural default and ,.expatiate

upon,, the prin-

ciples of Syires. Post, at l, 6-?, It is immediateiy apparent that these

charges of "judicial activism,, and ,tevisionism,, .ary *0"" rhetorical force

than substance. Our decision addresses the claimjof three respondents,

and Jusr:cs BRENNAN does not dispute our characterization of the peti-

tions filed by respondents Bell and Hughes. Ifthe Court were motivated

by a desire to expound the law, rather than to adjudicate the individual

claims before it, the cases of Bell and Hughes wouli provide ample oppor-

tunity for that task. Instead, we have attempted io decide eacl of tne

controversies presented to us.

- JusrIcE BRENNAN, moreover, clearly errs when he suggests that

Isaac's habeas petition ,lresented exactly one claim,,, that the ,.selective

retroactive application of the Robineon mre denied him due process ofIaw." Post, at 1,3. Isaac,s memorandum in support ofhis habeas peti-

tion did not adopt such a miserly view. Instead, ijaac relied heavily upon

MuLlaney v. Wilbur,42l U. S. 684 (1925); pottenon v. New york,'482

U. S. l9? (1977); and Hankenon v. Norlh Carolina,4l]2 U. S. Ug (.9.n),

cases explaining that, at least in certain circulultances, the Due process

Clause requires the prosecution to disprove affirmative defenses. See

App. to Brief in No. 28-8488 (CA6), pp. 26, 28_31. Nor did the District

Judge construe Isaac's petition in the manner suggested by Jusrrcr Bnnx-

NAN.. Rather, he believed-that Isaac raised "the federal constitutionar

question of whether, under Ohio law, placing the buden oip;,rn;th;;

firmetive defense of self{efenEe upon thelefendant viohles the defen-

dant's due process right to have the State prove each essentiel element of

the crime beyond a reasonable doubt.,, App. to pet. for Cert. A4f. Simi-

larly, ail but one of the sixth circuit JudgeJwho onsidered Isaac,g case en

banc thought that Isaac raised morc claims thrn the one isolated by Jus-

TIcE BRENNAN. Even the panel opinion invoked byJusrrcr BBENNAN,

p-ost, at 6, n. 10, r€jected the notion that Isesc pr.eaented only one claim.

646 F. 2d, at 1127. Isaac,s own.brief to this Court, flnally, recites a long

list of claims. A.lthough he alludes to the argumeni feetured by Jusrrci

BRENNAN, he dso maintains that his jury was misingtructed ,,[a]i a metter

of federal constitutional law,,' Brief for Respondent Isaac lE, and that

Mullaney v. wilbur urd Hankerson v. North corolina conurr his claims.

Id., at2,3, f3-15. Under these circumstrnces, it is incomprehensible that

JUSTToE BRENNAN construes Isaac,s habeas petition to raise but a single

claim.

It appears to 'J8, moreover, that the claim touted by JusTIcE BRENNAN

formed no part of Isaac's original habeas petition. While Isaac,s petition

and supporting memorandum referred toihe Ohio Supreme Court,s deci-

sion inStote v. Humphries, Sl Ohio St.2d 95,864 tt. p. Za 1354 (fgZZ),

Isaac did not discuss that decision,s distinction between bench and jury tri_

als, the distinction that JUsTrcE BRENNAN ffnds so interesting. poit,

"t2. Instead, the focus of his argument wa! thst ,.tilf a state dlchres dis-

proving an affirmative defense (once reised) is an element of the state,s

case, then to require a defendant to prove that aflrmative defense violates

due process and fu.ll retroactive effect must be accorded to defendants tried

under rhe erroneous former law.,, App. to Brief in No. Zg-34gg (CA6), p.

30. Thus, Isaac reasoned that once Robiwon interpreted absence ofself-

defense as an "element of the state,s case,,, Mullaney imposed a constitu-

tional obligation upon the State to calry that burden. Iiohio did not ap

ply Robinson retroactively to all defendants "tried under the enoneous

frrrmer law," Isaac concluded, it would violate Multoney. Ohio,s failure to

app.ly Robinson rerroactively to him violated due process, not because Ohio

had applied that decision retroactively to other defendsnts, but because

"[t]he instruction at his trial denied him due process under Muilaney.,,

, ohio

(Jan. 22, 1980).

Self-defense, respondcnts urge, these elements of

criminal behavior. Ther.efore, the defendant raises the

ts contend that the

as part of its task of estab-

lishing gtilty mens voluntariness, and unlawfulness.

Devera.rirouns have applied ow Mullaney arfr lqtterson

opipidn! to charge the prosecution with tire consiiiuqional

ryf ryvrlflEgg9of selfdefense.ts Most of these"duci-

E. 2d 818 (Munic. Ct. 19?5). Ilorrover, while Ohio requires the triai court

t-9 charge the jury on all elemints of a crime, e. g., Staie v, Bridgrmnn, bl

Ohio App. 2d 105, 366 N. E. 2d lg?8 (I9??), vacated in part, SS titrio St. Za

261, Stll N. E. 2d 184 (19?8), it does not require e.xpliciiinstructions on the

prosecution's duty to negate selfdefense beyond a reasonable doubt.

Shte v. Abnr,55 Ohio St. 2d ZSt, 879 N. E. 2d 228 (19?8).

" We have long recognized that a ,,mere enor of state lau/, is not a de-

nial of due process. Gryger v. Burke, lM U. S. ?ZB, ?91 (194i]). If the

contranr were tme, then ,,every erroneous decision by a state cou.rt on

state law would come [to this Court] as a federal constiiutional question.,,

/bid. See also Beck v. Washington, g69 U. S. E4l, btt-SSE Qg6i); Bishop

v. Mazurkiewicz, 634 F. Zd 724,726 (CAB 1980); United States ex rel. Bui-

nett v. Illinois,619 F. 2d 668, 6?0{?l (CA? 1980).' E In further support of the claim that, $ 2901.05 aside, due process re-

quires the prosecution to prove absence of self-defense, respondent Bell

maintains that the States may never constitutionally punish actions takenin relf.defcnre. If fundements.l notion! of dui process prohibit

criminrllaation ofactiong taken in self-defense, Bell suggeits, then absence

of self-defense is a vital elemert of every crime. See"ftffoies .fr Sieptran,

pefgnsgs-, Presumptions, and Burden of Proof in the Criminal t aw, Sg yae

. L. J. 1825, 1366-tA?9 (19?9); Comment, Shifting the Buriien of'proving

!g^tf-_O_9f9111W]th Analysis of Retated Ohio Lai, lt Al<ron L. Rev. ?t?]

75&759 (19?8); Note, The Constitutionality of Affirmative Defenses After

lattersytv. NaoYork, ?8 Colum. L. Rev. 655, 672-4?8 (19?8); Note, Bur-

dens of Persuasion in criminal proceedingr: The Reasonable Doubt Stand-

ard Lfter Patterson v. Nqw ymk, ll U. Fta. L. Rev. BgE, 415_416 09?9).AE. 9., Tennon v, Ricketts, U2 F. Zd t6t (CAE Lg8t); HoLlowaA v.

McElroy,632 F. 2d 605 (CA5 1980), cert. denied, 4Er U. S. 1028 (1981):

awftrl, Stole v.

County, Ohio,

Bl 938 Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. Bult. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

time of his act or failure [to act]"); State v. Clifion, 82 Ohio

App. 2d ?&, W?f.7, n0 N. E. Zd lLt, 9A O97Z) (,.one who

kills in selfdeferue does so without the maw rea that other-

wise would render him culpable of the homicide,'). In addi-

tion, Ohio punishes only actions that are voluntary, Ohio

Rev. Code Ann. $2901.21(A)(1) (19?5), and r:nlawfu], Sta,tev.

Simmr, No. 6262, p. 13 (Ct. App. Montgomery County, Ohio,

Jan. 16, 1980), modified on reconsideration (Jan. 2' 1980).

Selfdefense, respondents urge, negates these elements of

criminal behavior. Therefore, once the defendant raises the

possibility of selfdefense, rbspondents contend that the

S?1. must.{i:prove that defense as part of its task of estab-

lishrng guilty mens rea, voluntariness, and unlawfulness.

The Due Process Clause, according to respondents, interpre-

tation of Winship, Mullaney, md Patterson, forbids the

States from disavowing any portion of this burden.z

_ this argument states a colorable constituti-qud _elel-r_q:

Several courts have applied our Mullaney and PaAerson

opinions to charge the prosecution with the constitutionai

duty of proving absence of selfdefense.ts Most oFIteS6TeA-

EIn fi:rther support of the claim that, $2901.05 aside, due process re

quircs the pr.osecution to pmve absence of selfdefense, respondent Bell

nraintains that the States rnay never constitutionaily pr:nish ictions takenin selfdefense. If fundamental notioru of dui process prohibit

crimindization of actjons taken in seif-defense, Beil suggelts, tien ibsence

of selfdefense is a vitd element of every crime. See Jefties & Stephan,

Defenses, hesumptions, and Br:rden of Proof in the Criminal Law, gg' yale

L. J. 1325, 1366-1379 (1979); Comment, Shifting the Burden of hoving

Self-Defense-With Andysis of Related Ohio Law, 11 .ilaon L. Rev. ?1?]

75u759 (1978); Note, The constitutionality of Afrrnrarive Defenses After

Pattrtonv. NantYork,iS Colum. L. Rev. 6i5,6?2-6?8 09?g);Note, Bur-

dens of Persuasion in criminal Proceedings: The Reasonable Doubt stand-

ard After Patterson v. Nat York, Sl U. Fla. L. Rev. 985, 415-fl6 (19?g).

'8. 9., Tmtwn, v. Ricketts, el2 F. 2d 161 (CAi l98t); Holloutdy v.

McElroy, 632 F. 2d 605 (CAE 1980), cen. denied, 4S1 U. S. lOZg (19g1);

Wynnv. Moltonzy,600 F. 2d 44tl (CA4), cert. denied, tU'r.1. S. 980 (ISl9);

Commonwealth v. Hilbefi, 476 Pa- 288, 882 A. 2d 721(19?8). See also

Cornraent, 11 Ahon L. Rev., su,prd n.22; Note, 78 Colum. L. Rev., tupro

cited 42 ccH s. cr. Buil. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

sions adopt respondents' reasoning that due process com-

mands the prosecution to prove absence of selfdefense if that

defense negates an element, such as prJryoseful conduct, of

the charged crime. Whiie other courts have rejected this

tlpe of claim,a the controversy suggests that respondents'

second argument states at least a plausible constitutional

ciraim. We proceed, therefore, to determine whether re.

spondents preserved this claim before the state corrrts and, if

not, to inquire whether the principles articulated in Wain-

ulright v. Sgkes, supra, bar consideration of the claim in a

federal habeas proceeding.s

*2.

u E. 9., Corter v. Ja7o,637 F. 2d dAg (CA6 1980); Bakq v. Muney, 6lg

F. 2d 3?7 (CA4 1980). See dso Lelanl. v. Orugon,343 U. S. 790 (1952)

(nrle requiring accused to prcve insanity beyond a reasonable doubt does

not violate due ptocess)

6 Jus'ncs BnSNNAN zrccuses the Court of misreading Isaac's habeas pe-

tition in order to create a procedr:ral default and "expatiate upon" the prin-

ciples of Sykes. Post, at l, {7. It is immediately apparent that t}rese

durges of ludicid activism" and tevisionism" carry more rhetoricd force

than substance. Our decision addresses the claims of three respondents,

and Jusrrcu BneNNAi.I does not dispute our characterization of the peti-

tions filed by respondents Bell and llughes. If the Court were motivated

by a desire to e:rpound the law, rather than to adjudicate the individr:al

claims before it, the cases of Bell and Hughes would provide ample oppor-

tunity for that task Instead, we have attempted to decide each of the

controversies presented to rx.

Jusrrcp BnENNIN, mor€over, clearly er:: when he suggests that

Isaac's habeas petition *presented exactly one claim," that the "selective

retroactive application of the .&obrn^roa rtrle denied him due process of

law." Post, at 1, 3. Isaac's memorzndum in support of his habeas peti-

tion did not adopt such a miserly view. Instead, Isaac relied heavily upon

Mullanry v. Wilbur,42l U. S. 684 (19?5); Pattqson v. New York, 132

U. S. 197 (1977"); and Hankerson v. North Carolina,432 U. S. 233 (19m,

cases erplaining that, at least in certain circumstances, the Due Process

Clause requires the prosecution to disprove affirnrative defenses. See

App. to Brief in No. 7&3488 (CA6), pp. 26, 28-31. Nor did the District

Judge consaue IsaaCs petition in the manner suggested byJus:rco Bnsx-

NAII. Ratier, he believed ttrat Isaac raised *the federal constitutional

B1 939

B1 940 cited 42 ccH s. cL Bull. p.

ENGLE U. ISAAC

III

Noneof theresDondentslha[gngedl,hesgel-tilu$sEiilLof

tfr"-*mm*"Gtnrction gL They thus violated

oE6:rilt uiffi :ffi ilJo; wFich requires c ont emporzneous

questionofwhetjrer'rrnderohiolaw,placingthebr:rdenofproving.l'"d.

i*tir" defense of selfdefense upon the defendant vioiates the defen-

dantls due proc$s right to have the state prove each essential element of

thecrimebeyondare_asonabledoubt."App.toPet.forCert.A4l.Simi.

lariy, att Uut one of the Sixth Cirsuit Judges who considered Isaac's case en

U"ri.'*,"rgirlthat Isaec raised more claims than the one isoiated by Jus

ucr gB3}n*r. Even the purel opinion invoked by Jus:rcu BBEuxeN'

poi, x 6, n. 10, rejected the notion tlat Isaec presented oniy one eleivn'

[G it. Za, zt Llhl. Isaac's own brief to this Cor:rt, finaily, recite_s a long

list of claims. Although he alludes to the argp.urent featured by Jusrtcs

gnsNNA.},, he also

'aint.in"

that his jury was misinstn:cted ,.[a]s a matter

of federal constitutional law," Brief for Respondent Isaac 15, and that

i"iir,.t v. Wilbu,r std Honketzonv. North Comlina control his claims.

ti., itz,i, 13_15. under these circumstsnces, it is incomprehensible that

JUSf,ICE BREITNAN corultrues Isaac's habeas petition to raise but a single

elqim

It appeas to us, morcover, that the claim toutd by Jus:cn BnSMIAN

fo'ru.6'no part of IsaaCs original habeas petition. While Isaac's petition

and supporting memoranduil referred to the Ohio Supryme Co-r5t': d*i-

,ion io'Stot, i. Humpt,rtes, 51 Ohio St. 2d 95, 364 N' E' 2d 1354 (19m'

i.""" Oa not discuss that decision's distinction between bench and jr:ry tri-

"r.,

tr," distinction that Jusmcr BRENNAN finds so interesting. Post, at

2. Instead, the focus of his argument wes that "tilf a state declares dis'

,*"ing an

'affirmative

defense (once raised) is an element of the state's

;as", tf,"n to require a defendant to prove that afrrmative defense violates

;;;;;"* and'tull retroactive effecl must be accorded to defendants ried

unaer *re erroneous former law." App. to Brief in No. 7&3488 (cA6)' p.

80. Thus, Isaac reasoned that once nibAsrn intera'eted absence of se6-

defense as an "element of the state's ese," Mullaneg impgsed a-constitu-

tionalobligationupontheStatetocar:?thatbrrrden.IfOhiodidnotap

ply Robinlson r€troactively to all de{endants "tried under the etToneousi

ior.", Iaw,, Isaac conclud-ed, it would violate Mullancy. Ohio's failure to

applyrBobinson,remactiveiytohimvioiateddueprocess,notbecauseohio

iraa appriea that decision retroactively to other defendants, but because

"ttlhe instnrction at his trisl denied him due Process undet Mulloney,"

.q,pp. to Brief in No. ?8-3488 (CA6), pp' 2*27' This argument parzlleis

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

ENGLE u. iSAAC

objections to jury instructions. Failure to comply with Rule

30 is adequate, under Ohio law, to bar appeilate corsideration

of an objection. See, e. 9., State v. Humph,ries, 51Ohio St.

2d 95,364 N. E. 2d 13il Qgm; Stute v. M,on,28 Ohio Sr.

2d45,276 N. E. 2d %i! (1971). The Ohio Supreme Court has

enforced this bar against the very due process argument

raised here. State v. Williams, Sl Ohio St. 2d 112, 364 N.

E.2d l}64 (L97n, vacated in part and remanded, 438 U. S.

911 (19?8).st We must determine, therefore, whether re.

tlte ones we discuss in te:rL

It is, of coullle, possible to constnre Isaac's confirsed petition and sup

porting memorandum to raise the claim described by Jusncr BnoNNAN.

Many prisoners allege general deprivations of their constitutional rights

and raise vague objectioru to various state nrlings. A creative appellate

judge could almost always distill from these ailegatiorc an rurexhausted

due prrcess clqir. U such 3 clqinl were present, Rose v. Lwrdy,

-u. s.

-

(1982), would mandate dismissal of the entire petition In this

caEe, however, the District Judge did not identify lhg .laia that JusttcE

BnSNNAN proffers. Under these cirrcumstances, we are reluctent to inter-

polate an rurexhausted claim not directly presented by the petition Rose

v. Lunl,y does not compel such harsh treatment of habeas petitiors.

t While r.espondent Bell does not deny his procedr.r:zl default, he argues

tjrat we should overlook it because the State did not raise the issue in its

fllings witn the District Conrt. In some caBes a State's plea of default may

come too late to ber consideration of ttre prisone/s constitutional cisim-

E. 9., Estclla v. Smith,451 U. S. 4tl, 468, n 12 [981); Jtnkbu v. And.er-

son, 447 U. S. 231, fu|, * 1 (1980). In this case, however, both the Dis-

trict Cout and Court of Appeds evaluated Beil's default. Bell, mor€over,

did not make his '\raiver of waiver/ claim until he submitted his brief on

tlte merits to this Court. Accordingiy, we dedine to consider hjs

aryurnent.

t In Isaec's own case, the Ohio Court of Appeds refi:sed to entertain his

chdlenge to the selfdefense instruction because of his failure to compiy

witi Buie 30. The Ohio Supreme Court subsequently dismissed Isaac,s

appeal for lack of a srrbstantial constitutional question. It is unclear

@etgg-t$l&glgrmersly-stelu;"y,@,

on the seif-defense instnrction used at Isaac's trial. If Isaac presenied his

c Affis.ffi-fhey determined, on the

81 941

it*rt:i

81942 cited 42 ccH s. ct. Bull. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

spondents may litigate, in a federal habeas proceeding, a con-

stitutional clain that they forfeited before the state courts.6

A

The qrrit of habeas cor?us indisputably holds an honored

position in or:r jurispnrdence. Tracing its roots deep into

English eommon laur,p it claims a place in Article I of or:r

Constitution.o Today, as in prior centuries, the writ is a

very facts before trs, tltat the claim was waived.

Relyins upon Stale v. Lon4,53 Ohio St. 2d 91, 972 N. E. 2d 804 (tylg),

respondents argue that the Ohio Supr.eme Cout has recogdzd its power,

uaden Ohio's phin-eror nrle, to excuse RuIe B0 defaults. Lon4, howev*,

does not persuade us that the ohio corrrts wouid have excused respondents'

defaults. First, lhe Lorq covx, stressed that the plain-error n:.le applies

only in 'exceptional gilarrrnqtanggs," such as where, ,tut for the error, the

outcome of the Eiel cleariy would have been otherwise." 1d,., et S, ffi,

3?2 N. E. 2d, ar 8(f, 808. Second, the Long decision itself refused to in-

voke t}te plain-error ruie for a defendant who presented a constitutional

claiu identical to tlte one pressed by respondents.

tAs we recognized n Sykea,433 U. S., at ?&?9, theoroblem of,.waivgf

eggPflalf; {tm{Le qleslieLwhether s state prisoner t ae,effiteds!*"-

renedigl./ Section a-54(b) requires habeas applicants to exhaust thoie

remedies "available in t}te courts of the State.,, This requirement, how-

ever, rcfers only to remedies still available at the time of the federai peti-

tion. S* Hunplwey v. Col,y,40S U. S. 504, 816 (19?2); Foy v. yao, nZ

U. S. 391, 435 (1963). Bespondents, of coune, Iong ago completed their

dircct appeds. ohio, moneover, provides oniy limited coilaterar review of

convictions; prisoners may not raise cleims that could have been litigated

before judgment or on dir€ct appeal. See Ohio Rev. Code Ann.

$ 2953.21(A) (1975); Collhu v. Perini,594 F. Zd S9Z (CA6 L979); Keener v.

Ri.d,enou,r,594 F. 2d 581 (CA6 lg?g). Since respondents could have chal-

lenged the corstitutionaiity of ohio's raditional sel.fdefense instnrction at

Eid or on direct appeal, we agree with the lower courts that state collat-

eral reliefis unavrilable to respondents and, therefore, that they have ex-

hausted their state remedies with respect to this claim.

lSee 3 W. Blackstone, Commenraries *129-*188; Secretary of Sto,te for

Hona.$airt v. O'Brian, [1923] A. C. 608 (H. L.).

"Art. I, $9. cl. 2.

cited 42 CCH s. ct. BulI. p.

,"lff"t.IH*l#*::$1,il,r'*':fii"1-fi'absenceornrur-

opoo,r,"

,, ^?:f|.re".?

depends

fi;-.;;;,;.;';ffi:dH,:,,,,1H,ft tr#'Hil rtlff H

Juszrcs PowEr'L. elucidating a position that uitimately commanded a ma-io?g ofjhe

.Cou:r, sinitarlyiu;;;;; *-'

i\o eEective judicial system .an aforU to concede the concinuing theo-reticat possibiritv tt.t tt

"r"

ir i# ;:;;iriai and that everT in&""o-tion is nnfor.rnded. At some point the f". mu.t convey to thosi in custoOythat a wrong has been. committed, ,t", .o*!oent punishment has beenuposed' that one should no rong;iro;i.ii.fi r, ,rr" "i.-i. "..,rfi.tingevery imaginabre basis.fort

"ri,ziriiig"rffi* rarher should rook forwardto rehabilitation and b^b-e-eoming. .;;;;.;;e cirizen.,, Schnecktoth v.Bustamonte, ttz U. S. zl8, zoz?r-grii?prriL", J., concuning) (footnote'Till*

"-1T-*: l,r '.

p*,,itl,-ci;u. i. nuu (1e?6).

81943

ENGLE u. ISAAC

buiwark against.convictioru that violate,,fundamentar fair-

l"T:ilii?tttlrbht "' suiri, i,rer, at g7 (smGis, .r.,

we have aiwavs reeognized, however, that the Great writentails significani.cols." dx";"; review of a convictionextends the ordeai of trial f;; b"il;rciety and the accused.As Justice Harlanonce obser:rred,;iUtoti, the individual crim_inai defendant and .o.i.iy rr"r" *Lt"rest in insr:ring thattiere will at some point 6" il.;;ainty that comes wiiir anend to litigation, anh tharat;;; *ix uitimatery be focusednot on whether a conviction *ot."from enor but rather onwhether the prisoner can be r.rtoi.a to a usefur piace in thecomnrunity." Sanlers v. Unltei iiates, BTB U. S. l, Zn.Z,.(Harlan, J., dissenting. S"" ;;iffon*nrott, v. North Caro-li??a, 4BZ U. S. 213, ZEz <6mFo;ilrr, J., concunring in thejudgment). By B.ilring iG" irl."ests, the writ under-mines the usuai principles ;f firfity;f Htigation-ra

,-,i"1til.:tE&EquiLffi #x;",x,:trJil".fff; ,,Hsyste' of criminal justice rerribry b"d if; ;i. wiling to rorerare sucir ef-

ff ;.T*s3ilfl

Ttr?*%m*uirtr;:Hft:",tr

81914 Citcd 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull' P'

ENGLE U. ISAAC

Uberal ailowance of the writ' moreover' degrades the

prominence of the UJitt"n A criminal trid concent':ates

societt's r.ro*t'lii#"&t *d place in order to decide'

within the limits of-tuil f^fiiUiUtv' the question of guilt or

innocence.' Wo;inifrht v' Sykes' -wtrt"' at90' Our Con-

stihrtion and laws ;ffiffi;l uia *tt' a multitude of pro-

tections for the ".;;;'

-n"1U9r.tUan

enhancing these safe'

guards, ready "';il;ii'y

or uaugas corpusi may diminish

their sanctitv ov ffi;;ti".F i" iftt- triat panicipants that

therne may be no n..i'to "df,"".

to those safeguards during

the trial itself.

We must also acknowledge that writs of habeas corpus fre-

ouently cost sociJ]'if"

'lS,nt

to prurish admitted offenders'

Pasrage of time, tiotion o1*t*ory' and dispersion of wit-

nesses may rende";;"id aimtott' even impossitie' Wtrile a

habeas writ may,';;;'Tt'ntiii9 the defendant only to re-

trial, in practice i;';;;;t;;d the accused with compiete

freedom

-from

Prosecution'

Finaily, the Great Writ impose.s sFciat costs on our federal

svstem. lhe States possess pnqarr authority for defining

and enforcins th;';;;;-;J'

-h *iti""i trials thev also

holdtheinitiairesponsibilityrqvinaicatingconstitutional

rights. reaerar liitilsio* irrto state criminal trials ft'ustrate

both the States' sovereign -power

io punish offenders and

their good faith attemptsio [onor constitutional rights' See

sctmecktoth ,.';;;;;*':;;u u' s' 218' 26e-i266 (1e73)

,t"r** r., concuring)'B

mandsttrattheconvicteddefendarrt.realize"thatheisjustlysubjectto

sancrion, that he sili-J ;-;;; renaiititatlon." Bator, Finali* in

crininar Law and rI.liE"u"". co"p* i* st"te prisoner:, 76 Ha.r' L'

il;. A' .52 (196s; Friendlv' szpro nt 1' at tn6'

! During the last iwo decaies, o,:r corstitutionai jrrrispnrdence has rec'

ognized numenorur ":;"it!;;;

oi,,'i'a a"i"ta*t!' Although some ha'

beas writs cortect .,iotati.ons of long.estabtisired constitutiond rights, ot}t.

ers vindicat" *"""-il"I &-": state cotrrts are under:tandabiy

frtstrated o,t"n ,flv"iifin jil"pprv

",or,ing

constitutional rarr onlv to

Cited.42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p. 81945

)

ENGLE u. ISAAC

In Wa.intyigh! .v, Svkes, we recognized that these costsare parricularry high when'a tdar deauitil;ill.ia pris-' oner from obtaining adjudicauon ori* constitutionar craim inthe state courts.

_L Ui"tlit

"ti.n,

,fr. trial court has had noopportunity to correet the defect and avoid problematic retri-als. The defendanq,s.guns"l, fr, *ir"tever reasolut, has de-tracted from the triai,s .is,idd.. Uy n"si..l;;;; *."

"claim in that foruu.s Th-";t"t" appellate courtl have nothad a chance to mend their own-i.n.". and avoid federar in-hrusion' Issuance of a habeas-il, fina,y, exacts an exhzcharge bv r:nderttting the slatet'auiutyii, .J.i.Ji, p*-ced,rai ruIes' These-.o^ia-.otr]ons supported orrr sykesruling that, when a proced,rzl aerauit u-d'.'t"tluiiluon ora constitutional craim, a.state p"i.on." may not obtain federalhabeas reiief absent..i,o*ini;;;" and actual prejudice.Respondents urge tt"t *.ir,r;d liri, s}}f,1.1i.". inwhich the constitut-ion"t .o* Jii ,rt g..t iir"1*tr,t a'stunction of the triat. I" ir;;;;o, ,o" exampte, the pris-

H;".jffifrut discover, during a g2p&4pnoceedi!& new constitu-

. Ia aa individual case, the significance oftluiltx, H#'}hTlfiudges. As one scholar hes'ou."*"airi#L t otirlng,ore subversive ofa judge's serue of resooruibiiity, ,iti;;;; subjeetive eonscienriousnesawhidr is so ess€nuiar a part oritre airn"rtt'*a subt,re art of judging welr,thaa aa indiscriminate acceptance of the noaon that all the shots wiu al-waln be calted by *,"T1-":lr".r. t-"* ';fu"

82, at 45t. Indiscrimi-rute federal inorusions may simply dirrdiroot out constit,tronarerror:, on ir,"i, oor. i#ir:"ffit.:f:I".*ffiltract from a federal court,s aury io *rr"*rrfa;U,j*Itcorrnsers .ir" o," i,-J,nffr.ffise or jusrice,,'

riei. we no"l-" i#1, UI,LT ;Trji:ffffi:i ::X"mXferatellr choose to witiilora

"

.,i,,; fr"Jrl=;r*dbag/,-to gamble on ac-

SHE Hi:;'r:Jrff'*'iti"" 'r"i'" ir,'#" tr," gamble do-esn,t pay of,

Br 946 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. BuJl. P.

ENGLE U. ISAAC

oner allegd that the State had violated the rights ryIan-

ffi by.t/irnnnn v. Arizma. 3&t u. s. 4il6 (1966). while

inis aereet was serious, it did not affect the determination of

guilt at trid.' W" do not beiieve, however, that the principles of- Sykes

lend themselves to this limitation- The costs outiined above

a; ;"4 depend upon the t1rye of claim.raised by the prisoner'

While the nat,re of a conshtutional claim may affect the cal-

culation of cause and actual prejudice, it does not alter the

need to make that threshold'showing. we reaf6rm, there-{

ior., tt

"t

any prisoner bringing a constitutional claim to, tirc

|

federal courtLouse after a state procedural default must dem- \

"*tr"t. cause and actual prejudice before obtaining reiief' -l

B

Respondents seek cause for their defaults in two circum-

.;4. First, they urge that they could not have known at

th;Urrr" of their triais that the Due Process C}ause addresses

tf," U*4." of proving affirmative defenses' Second' they

contend that any obje-ction to ohio's self-defense instnrction

;;di have been futiie since ohio had long required-criminal

J"f."a*t" to bear the.b,rden of proving this af6rmative

defense..Wenoteattheoutsetthatthefutiiityofpresentinganl

objection to the .t"t. .ou*s cannot alone constitute cause for J

"

i"if*" to object at Eial. If a defendant perceives

-a .con-

stitutionat claim and believes it may find favor in the federal

courts, he may not blpass the state courts simply because he

tlrirrkt'tft.V 'iiU be

-urnsympathetic

to the ciaim's Even a

'SeeEs&IIev.Willioms,4z5:tJ.S.i01,515(19?6)(Powrr.r.,J.,con.

"n

i;; (th" policy disfavoring inferred.waivers of constitutiond rights

"n-Jiot Ue .;-iA to itre tenjm of allowing counsei for a defendant delib-

;;Jy i, forgo objection to a .,r""ute triai defect, even though he is. aware

"i-ti*

fr"n A-andiegat lasis for an objection, simply !"""59-h"^!hought

il:*i*.-"rfa be fr;tile-tyueft v.woshtnston,646 F. 2d 355, 364 (CAg

iiilii tp*f", J., disseffiilg ifntitity qrnnot constitute cause if it means

91947

cited 42 ccH s. cu ButL p.

ENGLE U. ISAAC

statecowtthathaspreviouslyrejectedaconstihrtionalargu.

ment may decide, "opo" ttfi"ttion', t'hat the contention is

valid. Allowing otiiiod defendants to deprive the state

courts of this opplrtGty *ooia contradict the principles

supporting SYkes.i--'R6;ae-rits'

claim, however, is. not simply one of futility'

Th;y f,;h;" ar.g. tiot, { th:- time thev were tried' thev

couid not know #i Ohi.k selfdeferse instnrctions raised

.o*tit tion t qo..iio*' A criminal defendant' they urge'

may not waive .o*iit tional objections unknown at the time

of trial.

Weneednotdecidewhetherthenoveityofaconstitutiorral

clain ever establiJ;" ;;; for a faihrre to object'' We

might hesitate t. ;;t "

*ft that would require trial counsei

either to exercrse exiraordinary vision or to object to every

aspect of the pto."Ialgt

"

tl'i hope that some aspect might

rnask a latent .o*titoti-ona chim. on the other hand, later

discovery oi

"

.o*iit"tion* aetect.unlsrown at the time of

trial does not in;;;;ly render the original Sd funda-

mentally unfair.o Tt";;t;ems' howevei' need not detain

r:s here since respo"dents'claims were far from unLgrown at

the time of their trials'

simpty tbgt a clain was'tnaccepable -t9-that

partiorlar court at t}tat par-

doriar timel, cert. pending, Not !1;,1f6'

r In fact, fte aecisioi-to'withhold a known constihrtiond clain rcsem'

bles tlre rype of delibe#G;;;ondemned jn Fwv'Noio'372 U' S' 391

(1963). Since the ."*" "ia'p*Gce

standard is more demanding than

F'afs deliberat" urpr* "itiiltlii

see Sg&es' c't'pttu at 8?' we are conf'

il,;il;eivea' nrtiiity alone cannot constitute caus€'

r,he State .t"".."a?'ooi""g,r-"n, before this Cor:rt that it does not

seeh such a nrling. tnstead, Ohio r:rges mernely that qrhen the tools are

available to construct the argument'- ' - you can charge counsel with the

"iil*u"*.r raising thac arfrrment"' Transcipt at 8-j'-

" "lB;?; ;; ;'." d;ii ri i tot" r, 40 1 u. s._66?, 67 *7 02 ( lsrl)- ( sepa.nte

opinion of IIarIan, l.lr"iltiAi v'- tlnited Stn'tes' 401 U' S' 646' 66e466

(1911) (Mensreu J.: ;;.t -i"g T ^q* and dissenting in part);

Hor*enonv. No',h ii*ili,-ts2it. s. *s, 24*248 (19m (PowEI& J.,

eoncuring in ttre judgoent)'

B1 948

"':'+,-l

cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

a

ENGLE u. ISAAC

In re Wiwhip, 397 U. S. 358 (1970), deeided for:r-and-one.

haif years before the first of respondents'trials, laid the basis

for their constitutional ciaim. lnWinship we held that ,,the

Due hocess Clause protects the accused against conviction

except upon proof beyond a reasonabie doubt of every fact

necessary to constitute the crime with which he is charged."

Id., at 3M. Drrring the five years following this decision,p

dozens of defendants reled upon this language to challenge

the constitutionaiity of nrles requiring them to bear a br:rden

of proof.o In most of these cases, the defendants, ciaims

lEven before Winship, criminal defendants and cor:rts perceived that

placing a burden of proof on the defendant may 'riolate due pr.ocess. For

exarrple, in Stum.p v. Bentutt,3g8 F. 2d 111 (CA 8), cert. denied, 398

U. S. 1001 (1968), the Eighth Circuit nrled en banc that an Iowa n:le re

quiring ddendants to prcye alibis by a preponderance of the evidence vio-

lated due pnocess. The court, moreover, obsened: '"Ihat an oppressive

shifting of the br:rden of proof to a criminai defendant violates due process

is not a new doctrine within constitutional law." Id., zt 1p. See also

Johtuon v. Bennett,3g8 U. S. 25S 0968) (vacating and remanding lower

court decision for reconsiderarion in light of Stump); Stnte v. Nales, I

Conn. Supp. ?3, 248 A. 2d 2A (1968) (holding that due process forbids re-

quiring defendant to prove "lawfuI excule" for possession of housebrealcing

tools).

'S€e, €. 9., State v. Cotnmsnos, 461 S. W. 2d g (Mo. l9?0) (en banc)

(intent to retum allegedly stoien item); Phillips v. St,c;te,86 Nev. 720,475

P. 2d 671 (1970) (insanity), cefi. denied, 403 U. S. 940 (19?1); Common-

weolth v. O'Neal,441 Pa- L7, nl .4. 2d 4yI (19?0) (absence of malice);

Cotnrnonwealth v. Vqel, 440 Pa. l, 268 A. 2d 89 (1920) (insanity), over-

ruled,, Cornmonwealthv. Rose,457 P2.380, B21A.2d 880 (19?4); Smithv.

Smith, 4 l F. 20,572 (CA5 1971) (aiibi), cen. denied, 109 U. S. 88S (19?2);

United, Sloles v. Bmaer, {50 F.2d 799 (C-.1.219?1) (inducement), cen. de-

nied, {05 U. S. 10il Q972); Witbur v. Robbins, B.l9 F. Supp. 149 (}Ie.

1972) (heat of passion), aff'd sub nom.lYiiAurv. Mu,llaney. {?B F.2d g€

(CAl 1973), vacated, .114 U. S. 1139 (19?4), on remand, 196 F. 2d 1B0g

(CA1 19?4), affd,421 U. S.684 (19?5); Statev. Cueuas,53 Haw. 110, {88

P. 2d 3?€' (19?1) (lack of mdice aforethought or presence of legal justifica-

tion); Stala v. Brwnr,,163 Conn. 52, 301 A. 2d tl? (19?2) (possession of Ii-

cense to deal in dmgs), overnrled on other grounds, State v. Whistnant,

1?9 Conn 5i6, 4tT A- 2d 414 (1980); In re Foss, l0 Cai. Bd 910, 519 p. 2d

1Y73, 112 CaL Rptr. 649 (1974) (en banc) (enrrapment); Woods v. State, Z33

r*;!. . i:J--'-ri=.

ae;,:'? i

I$rg

:.1-i

;1'*i

jl*,. ., _

r".I

Cited 42 CCH S. CL BuIL p. 81949

ENGLE u. ISAAC

countered well-established principres of law. Nevertheress,

numerousr a0urts agreed that the Due proce.s cl"usu ,eglo.rjhe proseeuti-on to bear tt" U,,"a.n of ai.prioiil .."-tain atrrrrative defenses.'r In right of this

".udiv, *E .*-not say that respondents lacked the tools to consinrcthet

corutitutional claim. c

Gs. W|,211 S. E. 2d.B^g

!l{_a]. ta3*ority

_to

selt narcoric druSp), appeatdismissed, 42,V. S. 1002 (LlTl); Statc i. Auzyrrstct, Bg0 A Za ln (Ue.

1974) (mentat disease); lropt, v. Jordan,;imit. app. n,i, zid f.I w. zan Qg74) (absence

"{1n!:ir], 9ilapprovJ -01

other grourds, people v.Johtuon,4ffi Mich. rrl284 x. w. ii zrgirgzg); co*iiiri'tti-r. nor",457 Pz. g80, g2l A Zd gg0 0974) (intoxication); Retail Credit Co. v. DadzCounty, BgB F. Supp. S,, (SO n rgzil(nLt"n*." oir"r"oiiif" p*.*dr:res); Fuattes v. Statc, g4g A. ga f Oef" fylS) (octeme emotional dis-tress), ovem:led, S.,,t9 u. Mtyer, Bg? A. Zd, Lg4 <Del. fgiEj;

-E-il)",rn

r.sbt,, g4 Ge- g?,7,219 S-. E.

-2d

6a 0rrsl 1."11a"rer,"r;Sat

'f,.''o,ray,

276 Md. lz8, a45 A- zd 436 (rfr5) (alibi); Cro* v. stote,z8 Md. App. 640,

Yg A 2d 800 (19t5) (absence or maiice;-tu d;r;;;fil'r"0, al[], ,r,",due prccess requires p::"a!9l to negate most afrrmative deferues, in-

$udins ry{{efense), {!:TBUa. rsz, s6i.q" ea o29iie7ol, iarr-rl. nra-iruur, 4g ohio Aoo- 2d \n ,356 N. E . 2:d-72i (1g?5) (serfdefense), affd, 4?

9-T, S!. Zd 1oB, #, \ E. 2d 88 frszb.

-SI

atlrc Trimbte v. State. D Ga.gw, 4or+tz rgt s. E. ry $7, e6&€sg tigzl rair."ou'g'opui*i"riuil,ovemrted, pattereon v, S-ta!e_,_B Ga- 724, Zre S. E. id 6i iitiili'e*r,

y...Sbbt 23t Ga- ltg, 11g, 12.*W, ZOO S. A. U Z4,, %Z, ZSf-iW egn)(dissenting opinions) (iruanity).

severzl cor,menteto* arso pereeived thzt wiwtvip might arter tradi-tiond b_ude,ns of pmof for afrrmative defenses. E. g., W. LaFave & .4"Scott, Ilandbook on 9"rnT3 _L"* E8-,-;plaeSr lrfiZ); The SupremeCout 1969 Term,84 Harr,. L. Rev. t, t'56?i9?or;Sd;;'S;;"iit, ,,Ohio St. L. J., suyra n. .2, ztgf; Commeni, .O* hocess and Supremacyas Foundatjons for the-Ade=quacy nue: ttre'nemains of Federarism A-fterwi:Yrv. (uila1tey,26 U. ire. L. n.r.l7rigzal.{ Even those decisions rejecting tre ae&nJant,s craim, of cou:se, showthat the issue had been perciiv"a 6y.rrr"i J"r"ndants and that it was a riveone in the courts at the time.

€Respondent Isaac even had the benefit of orrr opinion n Muilanzy v.wi.!.Y', EW, decided three montjrs u"r.* irL oiri. rn Muilaneu we in-validated a Maine oractice- yegrins ;;;ilJ;*;; ;;ffJ,l*."by proving that they acted in ,r,"G"i ri prri,r". we thus explicitry ac-

Br 950 Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bult. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

We do not suggest that every astute couurel would have

relied upon trizs hzp to assert the unconstitutionatity of a nrie

saddling criminal defendants with the burden of proving an

affirsrative defense. Every trial presents a mpriad of possi-

ble claims. Counsei might have overlooked or chosen to

omit respondents' due process argument while prJrsuing

other avenues of deferue. We have long recognized, how-

ever, that the Constitution guarantees criminal defendants

only a fair trial and a competent attoraey. It does not insure

that deferue couruel will recognize and raise every conceiv-

able constitutionai claim. Where the basis of a constitutional

claim is syeilaHg, and other defense counsel have perceived

and litigated that claim, the demands of comity ana enaUty

counsel against labelling alleged unawareness of the objeetion

as cause for a procedural defauit.€

lcnowiedged the link between whuhip and constihrtional limits on assign-

ment of the br:rden of proof. Cf. Lee v. Missouri,4ilg U. S. 461, 462

(1979) (per curiam) (suggesting that defendants who failed, afi,er To.ylor v.

Louisiana,419 U. S. 5U (1928), to object to t}te exclusion of women from

juries must show catue for the failure).

Respondents ar3ue at length that, before the Ohio Supreme Court,s de-

cision in State v. Robiz.son, stpro, they did not k:ow that Ohio Rev. Code

Aan. $290f.05(A) changed the traditional br:rden of proof. Ohio,s inter-

pretation of $ 2901.05(A), however, is relevant only to claims that we reject

independently of respondents' procedurai default. See szpro, at lL,l2;

* ?5, sugro.

sRespondents resist tiis conclusion by noting lhzt Hankerson v, North

Camlbu,,4il2 U. S. 2&3, 243 09m, gzve Mullonzy v. Wilbur, tlre opinion

expiisitly recognizing Winship's efect on afrrmative defenses, "complete

retroactive effecl" Hankersonitself, however, acloowledged the distinc-

tion between the retroactive aveita[iffgy of a constitutional decision and the

right to claim that availability after a procedr:ral default. Justlcp WHrrE,s

majority opinion forthrighrly suggested that the States ,tnay be abie to in-

srrlrte past conyictions [from the effect of Multonqy)by enforeing the nor-

mal and valid nrle that failure to objeet to a jr:ry instnrction is a waiver of

any ciaim of eror." 4ii2 U. S., at 244 n. 8. In this case we accept the

force of that language as applied to defendants rried aft,et Winsbip.

since we conclude that these respondents lacked cause for their default,

Cited 42 CCH S. Ct. Bull. p.

ENGLE u. ISAAC

C

Respondents, findly, urge that we shouid replace or suF

piement the cause-and-prejudice standard with a plain-eror

inquiry. We rejected this argument when pressed by a fed-

erai prisoner, see United, Sta,tes v. Frady, ante, p.

-,

and

Fed.

state convictions, however, entail greater finaiity problems

and speeial comity concerns. We renrain convinced that the

burden of justifying federal habeas relief for state prisoners

is "greater than the showing required to establish plain error

on dhect appeal." Hmderson v. Ki,bbe,4il1 U. S. 145, 154

(l9TI); Uruited States v. Frady, ante, at

-.{'Cbntrary to respondents' assertion, moreoyer, a plain-

error standard is unnecessary to corect miscarriages of jus-

tice. The terms "cause" and "actual prejudice" are not rigid

concepts; they take their meaning from the principles of com-

ity and finality discussed above. In appropriate cases those

principles must yield to the imperative of a fundamentally

unjust incareeration. Since we are confident that victims

we do not consider whether tiey also suffered acaral prejudice. Respond-

ents trr3e that their prejudice was so great that it shouid permit relief even

in tlre absence of cause. Sykes, howeve!, stated these criteria in the con-

junctive and the facts of this case do not persuade us to depart from that

approach.

'Respondents bolster their plain+rror contention by obserwing that

Ohio will overlook a procedural defauit if the triai defect constitured plain

error. Ohio, however, has declined to exercise this discretion to reyiew

the type ofclaim pressed here. See n. ?I, suynt. IfOhio had exercised

its discretion to consider respondenrs' claim, then their initial defauit

would no longer block federal review. Sx Mullancy v. WilAur, su?ra, at

688, n. 7; Cou.nty Coufi of Ulster Cou.nty v. Allen, 442lJ. S. 140, L47-L:vl

(19?9). 0lr opinions, however, make clear that the States have the pri-

mary resporu;ibility to interpret and appiy their plain-enror ruies. Cer-

tainiy we shouid not r€ly upon a state plain-eror n:le when the State has

refused to apply thar nrle to the very sort of claira at issue.

Br 951

I

fud it no more compeiling here. the feaeratgurts apply a

per!€rror nue rbi drrelt renewffi

81952 Citcd42 CCH S. Ct. Bull' P'

ENGLE U. ISAAC

of a fundamental miscarriage--of.iutt':" wiil meet the cause'

and-prejudice starraara,

'"6

Woi"*;gtrt v' Sykes' ttt'pra' at

91; ,,;.;';twgl titsGNs, J', concurring)'-we decline to

adopt the more **" i"tiW suggested by the words

'Uain erTor.'

rv

Closeanalysisofrespondents,habeasoetitionsrevealsonly

one colorabi. .o*titiiio*f .irry- 8..,*t respondents

failedtocomply*iti'Ottio'sproceduresforraisingthatcon-

tention, ana Uecause they have not demonst'rated cause for

the default, they are baned from asserting lhat claim trnder

23 U. S. C. $ %4:

-

fn" judgments of thJCor:rt of Appeals