Gulf Oil Company v. Bernard Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1980

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gulf Oil Company v. Bernard Brief for Respondents, 1980. 66ea55fc-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/230a3556-3006-4e6a-843d-fc14ab2ba82e/gulf-oil-company-v-bernard-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Copied!

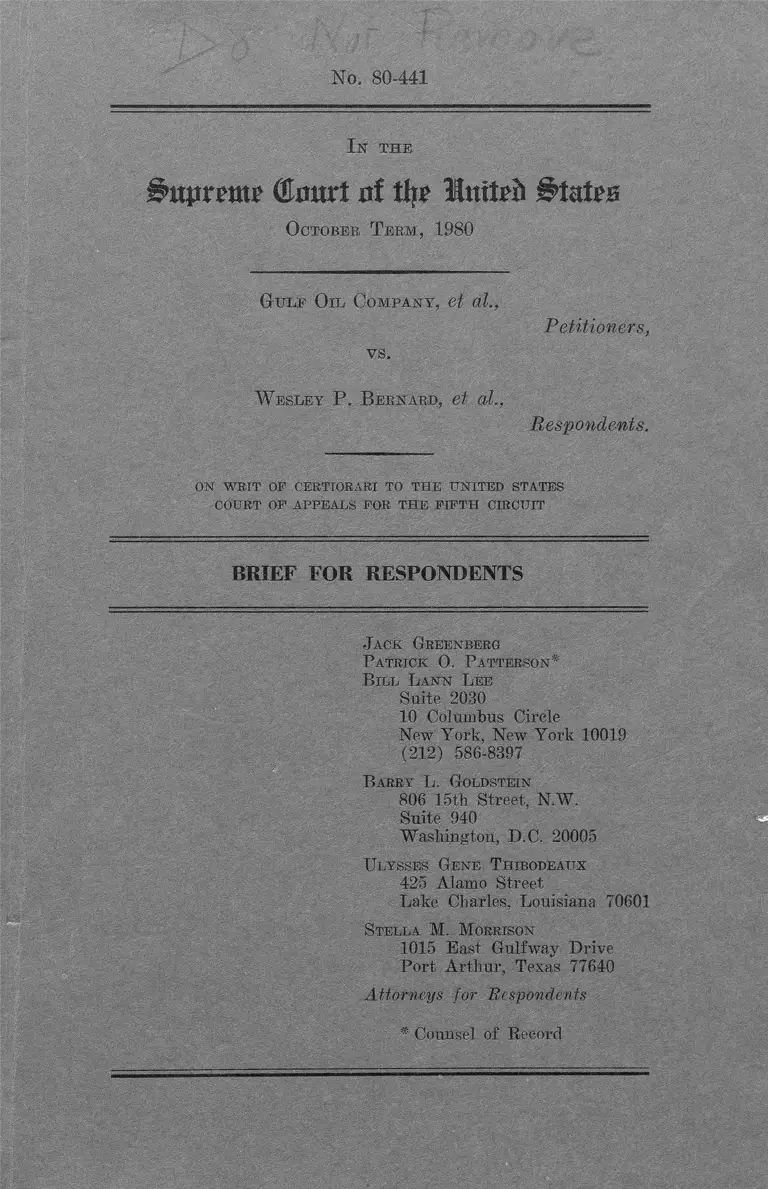

No. 80-441

I k t h e

&ttprrmr Court of % Initrti Butrn

O ctober T erm , 1980

Gulf Oil Company, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

W esley P. B ernard, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OP CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OP APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

J ack Greenberg

P atrick O. P atterson*

B ill Lann Lee

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Barry L. Goldstein

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux

425 Alamo Street

Lake Charles, Louisiana 70601

Stella M. Morrison

1015 East Gulfway Drive

Port Arthur, Texas 77640

Attorneys for Respondents

* Counsel of Record

Question Presented

Whether the district court's several orders

restraining communication by plaintiffs and their

attorneys with members of the potential class in

this civil rights action violated the Constitution

or the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, where

there were no findings of any improper conduct by

plaintiffs or their counsel, the uncontradicted

evidence demonstrates no misconduct by them, and

no evidentiary hearing was ever held. *

*J Respondents do not accept petitioners'

formulation of the question presented. See, Sup.

Ct. Rule 34.2. First, three orders were issued

barring communications, not one. Second, the

district court made no findings of any abuse,

actual or potential, and the Fifth Circuit panel

opinions (JA 195, n.14, 209-210 and n.9) and the

en banc court (JA 241 and n.7) found petitioners'

allegations of specific abuse "irrelevant."

Moreover, petitioners' brief cites no "actual"

abuse, and refers only to unsupported "threats

of abuse" and "threatened abuses." Brief for

Petitioners, pp. 11, 22, 36. Third, although

petitioners' question raises only the issue of the

constitutionality of the several orders, their

brief, pp. 14-26, also considers whether the

orders comply with Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro., as

did the Fifth Circuit. (JA 190-195, 208-216, 268,

269-276).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Question Presented .................. i

Table of Authorities ........ ........

Statement of the Case ........ 1

Administrative Proceedings ..... 2

Plaintiffs' Complaint and

Their Counsel ....... 9

The May 28 Order ................ 13

The June 22 Order .............. 17

The August 10 Order ............. 23

Other Proceedings .............. 24

Summary of Argument ........ 25

Argument .......................... 28

I. The Orders Restraining

Communications Denied Plain

tiffs, Their Counsel and

Potential Class Members

Meaningful Access to the

Courts in Violation of the

First Amendment

Page

34

A. Expression and Assoc

iation to Advance Litigation

Are Rights Protected by the

First Amendment ............ 34

B. The Orders Infringe Upon

First Amendment Rights With

out Requisite Proof of

Misconduct .................. 45

1. Absence of Proof of

Misconduct ............. 45

2. The Manual for Com

plex Litigation ........ 48

C. The Orders Impose Un

constitutional Prior Re

straint On Protected

Expression ................. 59

D. The Orders Are Over

broad ...................... 70

II. The Orders Restraining

Communications Violate the Due

Process Clause of the Fifth

Amendment ...................... 74

A. The Due Process Clause

Guarantees Plaintiffs and

Potential Class Members

Significant Procedural

Rights .............. 74

Page

-iii-

B. Adequate Information

Was Denied..... ....... 78

C. Effective Assistance of

Counsel Was Denied ......... 83

D. An Adequate Hearing and

Procedural Regularity Were

Denied ...................... 93

III. The Orders Are Inconsistent

With The Federal Rules Of Civil

Procedure ................... 97

A. The Orders Are Incon

sistent With Rule 23 ....... . 98

B. Rule 23 Should Be

Construed So As To Avoid

Grave Doubts Of Unconstitu

tionality .................. 105

Conclusion ......................... * 1°7

Addendum A

Addendum B

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Ace Heating and.Plumbing Co. v.

Crane Co., 453 F.2d 30

(3d Cir. 1971) .................. . 58

Cases: Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody,

422 U.S. 405 (1975) ........ 11, 44, 103

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.,

415 U.S. 36 (1974) 75, 77, 102

103

Bantam Books v. Sullivan, 372

U.S. 58 (1973) ......... 64

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S.

516 (1960) ....___ 34

Bates v. State Bar of Arizona,

433 U.S. 350 (1977) .... 53, 54,

55, 73

Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535

(1971) ............................ 75

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S.

371 (1971) ......... . 75, 93

-v-

Page

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S.

497 (1954) .............. .......... 83

Bridges v. California, 314 U.S.

252 (1941) ......... ...........____ 47

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen

v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1 (1964) .... 37, 41, 44,

45, 84, 89

Buckley v. Valeo, 424 U.S. 1

(1976) ................... . 64, 67

CBS, Inc. v. Young, 522 F.2d

234 (6th Cir. 1975) ............ 66

Cafeteria Workers v. McElroy,

367 U.S. 886 (1961) ---------------• 93

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310•

U.S. 296 (1940) ---...----------... 54

Carlisle v. LTV Electrosystems,

Inc., 54 F.R.D. 237 (N.D. Tex.

1972), appeal dism'd No., 72-1605

(5th Cir. June 23, 1972) ........... 59

-vi-

Page

Gaston v. Sears,- Roebuck & Co.

556 F.2d 1305 (5th Cir. 1977) .......... 88

Chicago Council of Lawyers v.

Bauer, 522 F.2d 242 (7th Cir. 1975)

cert, denied, 427 U.S. 912

(1976) ............................. 51, 66, 71

Christiansburg Garment Co. v.

EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978) ......... 44, 75, 88

Coles v. Marsh, 560 F.2d 186

(3d Cir.. 1977)', cert, denied,

434 U.S. 985 (1977) ............... 28, 47, 53,

97, 104

Cooke v. United States, 267

U.S. 517 (1925) ...................

*

85

Coopers & Lybrand v. Livesay,

437 U.S. 463 (1978) ......___...... 100, 101

Copeland v. Marshall, 24 EPD

5 31, 219 (D.C. Cir. 1980)

(en banc) .................. 41

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536

(1965) ............................. 83

-vii-

Page

Cox v. Louisiana 379 U.S.

559 (1965) .................*----- 83

Craiq v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367

(1947) ...................... . 50

Deposit Guaranty Nat'l Bank

v. Roper, 445 U.S. 326 (1980) .... 41, 99, 100,

101

East Texas Motor Freight System,

Inc. v. Rodriguez, 431 U.S. 395 (1977) 102

EEOC v. Red Arrow Corp., 392

F. Supp. 64 (E.D. Mo. 1974) ........ 60

Eisen v. Carlisle & Jaquelin, 417

U.S. 156 (1974) .................... 76, 97,

98, 99

Ex parte Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944) ... 105

First Nat'l Bank of Boston v.

Bellotti, 435 U.S. 765 (1978)..... . 47

Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976) .......... 12, 44, 103

-viii1

Page

Fuentes v. Shevin, 407 U.S. 67

(1972} ............................ . 75, 77, 78,

83, 93, 94

Gannett Co. v. DePasquale, 443

U.S. 368 (1979) ...___.....___ ... 65

General Telephone Co. v. EEOC,

446 U.S. 318 (1980) .............. 103

Gibson v. Florida Legislative

Investigation Comm., 372 U.S.

539 (1963) ....................... 34

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S.

335 (1963) ....................... 84

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254

(1970) .......................... 75, 84

Greenfield v. Villager Industries,

Inc., 483 F .2d 824 (3d Cir. 1973) . 79

Greisler v. Hardee's Food Systems,

Inc., 1973 Trade Cases f 74,455

(E.D. Pa. 1973) ...................

-ix-

55

Page

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401

U.S. 424 (1971) .............. ..... 11,

Hagans v. Lavine, 415 U.S. 528

(1974) ..................

In re Halkin, 598 F.2d 176

(D.C. Cir. 1979) ......

Halverson v. Convenient Food

Mart, Inc., 458 F.2d 927

(7th Cir. 1972) ......... .......... 29

Hansberry v. Lee, 311 U.S. 32

(1940) ......... ..........

Hawkins v. Holiday Inns, Inc.,

[1978-1] Trade Cases II 61,838

(W.D. Tenn. 1978) ...........

Hickman v. Taylor, 329 U.S. 495

(1947) .... ............ 67, 91

Hilliard v. Volcker, 24 FEP

Cases 1516 (D.C. Cir. 1981) ---...

102

97

71

53

76

60

, 92

88

-x-

Page

Hirschkop v. Snead, 594 F.2d

356 (4th Cir. 1979) .............. 66, 71

IBM Corp. v. Edelstein, 526

F.2d 37 (2d Cir. 1975) ............... 92

ICC v. Oregon-Washington R.& Nav.

Co., 288 U.S. 14 (1933) ................. 106

Johnson v. Robison, 415 U.S. 361

(1974) ..................... 83

Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116

(1958) ......................... 105

Kingsley Books v. Brown, 354 U.S.

436 d957) .................... . 52, 63

Korn v. Franchard Corp., 1971

Sec. L. Rep. 5 92,845 (S.D.N.Y.

1971) .................................. 58

Korn v. Franchard Corp., 456

F.2d 1206 (2d Cir. 1972) ___....... 58

-xi-

Page

Landmark Communications, Inc.

v. Virginia, 435 U.S. 829

(1978) .............--- ............ 50, 62

Love v. Pullman Co., 404 U.S.

522 (1972) ...... . 77, 87

Matarazzo v. Friendly Ice Cream

Corp., 62 F.R.D. 65

(E.D.N.Y. 1974) ...... 55

McCargo v. Hedrick, 545 F .2d 393

(4th Cir. 1976) ............... 97

Miami Herald Publishing Co. v.

Tornillo, 418 U.S. 241 (1974) ..... 64, 69

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises,

Inc., 426 F.2d 534 (5th Cir.

1970) ....... 12

Mosley v. St. Louis Southwestern

Ry., 634 F.2d 942 (5th Cir.

1981) ........................... 77

Mullane v. Central Hanover Bank &

Trust Co., 339 U.S. 306 (1950) ..... 78, 82,

84, 93

-xii-

Page

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel.

Patterson, 357 U.S. 449

(1958) ...... ...................... 67, 90

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415

(1963) ............................ Passim

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S.

697 (1931) ................ ........ 61

Nebraska Press Ass'n v. Stuart,

427 U.S. 539 (1976) ............... 71, 74

New York Times Co. v. Sullivan,

376 U.S. 254 (1963) ............... 55, 67

New York Times Co. v. United

States, 403 U.S. 713 (1971) ....... 61, 64

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises,

Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968) .......... 44

Niemotko v. Maryland, 340 U.S.

203 (1351) 83

-xixi-

Page

NLRB v. Hardeman Garment Corp.,

557 F ,2d 559 (6th Cir. 1977) .......

NLRB v. Robbins Tire & Rubber

Co., 437 U.S. 214 (1978) .. .

North American Acceptance v.

Arnall Golden & Gregory, 593

F.2d 642 (5th Cir. 1979) ---

Northcross v. Board of Education,

611 F .2d 624 (6th Cir. 1979),

cert, denied, 100 S. Ct. 2999-

(1980) ..... ..................

Northern Acceptance Trust 1065

v. AMFAC, Inc., 51 F.R.D. 487

(D. Hawaii 1971) ................ 55, 58

NOW v. Minnesota Mining Mfg. Co.,

18 FEP Cases 1176 (D. Minn. 1977) ,

appeal dism'd, 578 F.2d 1384 (8th

Cir. 1978) ....................

Ohralik v. Ohio State Bar Ass'n,

436 U.S. 447 (1978) .....

Oppenheimer Fund, Inc. v. Sanders,

437 U.S. 340 (1978) ................ 100,

91

91

80

41

60

58

72

102

-xiv-

Page

Oscar Mayer & Co. v. Evans,

441 U.S. 750 (1979) .............. 87

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Co., 411 F.2d 998 (5th Cir. 1969)... 91

Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Human

Relations Comm'n, 413 U.S.

376 (1973) ........................ 64, 72

Potashnick v. Port City Construc

tion Co., 609 F .2d 1101 (5th Cir.

1980) ............. 85

Potts v. Flax, 313 F.2d 284

(5th Cir. 1963) ................... 102

Powell v. Alabama, 287 U.S. 45

(1932) ........................... 85

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978) .... Passim

Reed v. Sisters of Charity of the

Incarnate Word of Louisiana, Inc.,

25 Fed. Rules Serv. 2d 331

(W.D. La. 1978) .................... 59

-xv-

Page

Regional Rail Reorganization

Act Cases, 419 U.S. 102 (1974) .... 105

Richmond Newspapers, Inc. v.

Virginia, 65 L.Ed. 2d 973 (1980) ... 30, 47

Rodgers v. United States Steel

Corp., 508 F.2d 52 (3d Cir.),

cert, denied, 423 U.S. 832 (1975) .. 97, 98,

103, 104

Roger J. Au & Son, Inc. v. NLRB,

538 F. 2d 80 (3d Cir. 1976) ........ 90

Romasanta v. United Airlines, Inc.,

537 F .2d 915 (7th Cir. 1976),

aff'd sub nom. United Airlines, Inc.

v. McDonald, 432 U.S. 385 (1977) ... 79

Rothman v. Gould, 52 F.R.D. 494

(S.D.N.Y. 1971) .................... 59

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241

(5th Cir. 1968) .............---... 97

Sargeant v. Sharp, 579 F.2d 645

(1st Cir. 1978) .................... 48, 94

-xvi-

Page

In re Sawyer, 360 U.S. 622 (1959) .... 57

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479

(1960) ....... ..................... 34, 72

Smith v. Daily Mail Publishing Co.,

443 U.S. 97 (1979) ................ 62, 63

Southeastern Promotions, Ltd. v.

Conrad, 420 U.S. 546 (1975) ....... 61, 63, 64

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513

(1958) ............................ 67

Stanley v. Illinois, 405 U.S.

645 (1972) ........ ............. 76, 77

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88

(1940) ..... 83

Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life

Ins. Co., 409 U.S. 205 (1972) ...... 44

United Mine Workers v. Illinois Bar

Ass'n, 389 U.S. 217 (1967) ......... Passim

-xvii-

Page

United States c. Jin Fuey Moy, 241

U.S. 394 (-1916) ..................105

United States v. Standard Brewery,

251 U.S. 210 (1920) .............. . 106

United Transportation Union v. State

Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576

(1971) ................. Passim

Vance v. Universal Amusement Co.,

445 U.S. 308 (1980) ................ 61, 63

Village of Schaumburg v. Citizens

for a Better Environment,

444 U.S. 620 (1980) ................54, 55, 56,

71, 72

Virginia Pharmacy Board v. Virginia,

Consumer Council,.425 U.S.

748 (1976) .......... 54

Walker v. City of Birmingham, 388

U.S. 307 (1967) ................... 70

Weisman v. Darneille, 78 F.R.D.

671 (S.D.N.Y. 1978) ---............ 58

-xviii-

Page

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co.,

508 F.2d 239 (3d Cir.), cert.

denied, 421 U.S. 1011 (1975) ....... 80

Winfield v. St. Joe Paper Co.,

20 FEP Cases 1103 (N.D. Fla.

1979) ............ 78

Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375

(1962) .......................... 47

Yaffe v. Detroit Steel Corp.,

50 F.R.D. 481 (N.D. 111.

1970) ......................... . ... 59

Yates v. United States, 354 U.S.

298 (1957) ........................ 105

Zarate v. Younglove, 86 F.R.D.

80 (C.D. Cal. 1980) ............... 41, 66

-XIX'

Constitutional Provisions and

Statutes;

First Amendment .............

Fifth Amendment, Due Process Clause ..

Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection

Clause ....... ....................

42 U.S.C. § 1981, Civil Rights Act

of 1866 ....... ...............

42 U.S.C. § 1988, Civil Rights

Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976 .

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq., Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as

amended by the Equal Employment

Opportunity Act of 1972 ..........

Rules:

Rule 34.2,

Court ..

Rules of the Supreme

-xx-

Page

Passim

Passim

83

2

44

Passim

Page

Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro............ Passim

Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. Pro............ 15

Rule 83, Fed. R. Civ. Pro.

Other Authorities:

ABA Code of Professional

Responsibility, DR 2-104 (a) (1) .... 53

ABA Code of Professional

Responsibility, DR 7-104 ....... . 60

ABA Code of Professional

Responsibility, EC 2-3 ...........

II ABA Comm, on Professional

Ethics, Informal Ethics

Opinions 537-540. Inform.

Op. No. 1280, Aug. 8, 1973

(ABA 1975) ........................ 55

-xxi-

Page

II ABA Comm, on Ethics and

Professional Responsibility,

Informal Ethics Opinions, Inform.

Op. No. 1283, Nov. 20, 1973

(ABA 1975) ...................... . 55

ABA Comm, on Professional Ethics

and Grievances, Opinions, No. 148,

1935 (1957) ................ 36, 53, 57

Advisory Comm. Notes, Proposed Rules

of Civil Procedure, 39 F.R.D. 69

(1966) ............................. 98

Comment, Judicial Screening of Class

Action Communications, 55 N.Y.U.

L. Rev. 670 (1980) (forthcoming) ... 5 0

Comment, Restrictions on Communica

tion by Class Action Parties and

Attorneys, 1980 Duke L.J. 360 ..... 50

118 Cong. Rec. 940-41 (1972) ......... 87

118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972) ........... 103

88 Harv. L. Rev. 1911 (1975) ......... 50, 66

—X X 1 1 !~

Page

Manual for Complex and Multi-

District Litigation, 49 F.R.D.

217 (1970) ........................ 15

Manual for Complex Litigation, 1 Pt.

2 Moore's Federal Practice (2d ed.

1980) Passim

Note, The Right To Counsel in Civil

Litigation, 66 Colum. L. Rev. 1322

(1966) ......................... 85

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, Civil Rights

Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976,

94th Cong., 2d Sess. (1976) ....... 44

Seymour, The Use of "Proof of Claim"

Forms and Gag Orders in Employment

Discrimination Class Actions, 10

Conn. L. Rev. 920 (1978) .......... 50, 67, 79

U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1970

Census of Population: General

Social and Economic Characteristics,

PC (1)- (45) (Texas) ....___........ 96

-xxiii-

Page

Wilson, Control of Class Action

Abuses Through Regulation of

Communications, 4 Class Action

Rpts. 632 (1975) .............

-xxiv-

No. 80-441

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1980

GULF OIL COMPANY, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

WESLEY P. BERNARD, et al.,

Respondents.

On Writ Of Certiorari To The United States

Court Of Appeals For The Fifth Circuit

»

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

r u „ 1/ Statement of the Case—

This employment discrimination action

was filed by six present or retired black employ-

1/ "Understanding the issues requires a more

complete history than [a] brief statement," as

the Fifth Circuit observed. (JA 199, see 234).

Cf., NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 4 15 , 4 1 9 -4 2 6

TT963)1 Petitioners' cursory statement of the

case, Br, pp. 3-7 , provides an inaccurate account

of the record.

ees of Gulf Oil Company's Port Arthur, Texas

refinery (hereinafter "Gulf") against Gulf and the

Oil Chemical and Atomic Workers International

Union and Local Union No. 4-23 (hereinafter

"unions") for violation of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e et seq.,

and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42 U.S.C. § 1981

2 /(JA 11).— The issue is the validity of, three

orders of the district court restraining communi

cation by plaintiffs and their counsel with

potential class members.

Administrative Proceedings

- 2 -

In June 1967, three of the plaintiffs, Wesley

P. Bernard, Hence Brown, Jr., and Willie Johnson

filed charges of racial discrimination with the

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (herein

after "EEOC") against Gulf and the local union

2/ Citations are to the Joint Appendix (here

inafter "JA"). The Brief For Petitioners will be

referred to hereinafter as "Br."

pursuant to Title VII. (JA 177).— The EEOC

investigated and issued decisions of reasonable

cause sustaining the three charges in August 1968.

(JA 178). On February 26, 1975, the three com

plainants received letters from the EEOC stating

that Gulf and the local union did not wish

to continue conciliation discussions, and that

they could request, at any time, notices of

right to sue pursuant to Title VII. (JA 178,

n.2). See, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(1).

Meanwhile, a separate charge of discrimina

tion on the basis of both race and sex at the Port

Arthur refinery was filed against Gulf by a

Commissioner of the EEOC in 1968. (JA 26). See,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b). Reasonable cause was

found to sustain the charge, and Gulf commenced

conciliation discussions with the EEOC and the

Office of Equal Opportunity of the United States

Department of the Interior. Eventually, a

- 3 -

3 /

3/ Overall, more than 40 charges of employment

discrimination were filed by black employees with

the EEOC against the company in 1967. Brief

for the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission,

Amicus Curiae, On Rehearing En Banc, 5th Cir.,

77-1502, at 2.

- 4 -

conciliation agreement was signed by Gulf, EEOC

and the Department of the Interior on April 14,

1976. (JA 26).

The conciliation agreement provided relief in

4 /three primary areas: "back pay,"- "goals and

5/

timetables" for upgrading certain employees,-

4/ Back pay was provided to black persons

employed by Gulf on July 2, 1965, whose seniority

date anteceded July 1 , 1957, and to hourly

rated women employed in Gulf's Package and Grease

Department on July 2, 1965. (JA 28). The formula

for back pay for black employees was $5.62 for

each month of continuous service prior to January

1, 1957, and $2.81 for each month of continuous

service thereafter until termination or until

January 1, 1971, whichever is earlier. (JA

30). Back pay *for female employees was figured

on the basis of $5.62 for each month of continuous

service until termination or until July 1, 1975,

whichever is earlier. Id.

5/ Black employees who were eligible for back

pay and were presently employed in certain menial

positions (Operator Helper No. 1, Boiler Washing

"X," Brander "X," Operator Helper No. 2, Utility

Helper, and Laborer) and women employees with

seniority anteceding April 5, 1974, were made

eligible for "affirmative action goals and time

tables". (JA 32). The relief involved a goal to

- 5 -

and a general "affirmative action" provision.-

The agreement required that employees accepting

back pay execute releases of all employment

discrimination claims against Gulf, and it estab

lished a procedure for tender and acceptance of

back pay (JA 31). The agreement further provided

5/ continued

fill one of every five vacancies in 43 "target

classifications" (identified as classifications in

which blacks, Spanish-surnamed persons and/or

women were statistically underrepresented), and a

goal to fill one of every seven official and

manager category positions with a black, Spanish-

surnamed or female employee until their respective

representation jointly within such clasification

equalled or exceeded their joint representation in

the company's workforce. (JA 32-35).

6/ "[Gulf] agrees to refine and strengthen on a

continuing basis positive and objective

nondiscriminatory employment standards,

procedures and practices and represents that

in its business operations it exerts continu

ing effort to uniformly apply such standards,

practices, and procedures in a manner which

will assure equal employment opportunites in

all aspects of its total workforce and

operation without regard to race, color,

religion, sex or national origin."

(JA 38).

- 6 -

that failure to respond within thirty days to

notice of the tender and the release agreement was

to be deemed an acceptance of back pay. (Id.)

However, the letter which Gulf sent to eligible

employees did not inform them that silence would

7 /be deemed an acceptance.— Contrary to the

terms of the agreement (JA 31), the letter did not

disclose the formula used in calculating back pay.

The letter admonished employees that, "Because

this offer is personal in nature, Gulf asks that

you not discuss it with others." Gulf represents

that letters offering over $900,000 in back pay

were sent to 614 black employees and former

employees and 29 women employees immediately after

the agreement was signed. (JA 22-23).

Neither the plaintiffs nor any members of the

potential class were parties to the conciliation

7/ This letter is reproduced as Addendum A to

this brief. Although the letter does not appear

in the record as transmitted by the district

court, that court referred to and briefly des

cribed the letter in its order of June 22, 1976.

(JA 128). The letter was also before the court of

appeals. See Brief for the United States as

Amicus Curiae on Rehearing En_ Banc, p.6 and

Exhibit 1. Therefore, the letter may properly be

considered by this Court.

7

agreement, nor was the agreement subject to

any judicial review or approval. The plaintiffs

found the relief provided in the conciliation

8/agreement grossly inadequate.- Under the agree

ment a black employee who, like plaintiff Wesley

8/ In a memorandum filed in the district court,

plaintiffs stated in part as follows:

"... [T]he agreement on its face does not

appear to satisfy the dictates of Title VII.

For instance, the Conciliation Agreement does

not provide for well-established types of

relief such as advance-level entry and job

by-pass; there is a one-shot opportunity to

bid and transfer into a different job class

ification; there are no provisions for a firm

recruitment program; there is no firm commit

ment on goals and timetables; the affirmative

action program is merely a statement of

policy rather than a realistic, programmatic

approach to the underutilization of minori

ties in the defendant's work-force. The

goals provided, one black, Mexican-American,

or woman for each four whites selected for

jobs from which blacks are underutilized (the

goals is one to six for supervisory posi

tions) is inadequate to remedy the practices

of discrimination in an area where over 50%

of the population is black; there is no

relief from unlawful employment testing

programs. These are only some of the ex

amples of how the Agreement does not begin to

- 8 -

Bernard, had worked at Gulf's Port Arthur refinery

since June 1954, was entitled to a total "back

pay" settlement of approximately $640, less

J . 9/deductions for social security and income taxes.™

Therefore, plaintiffs filed this action in the

district court.

8/ cont inued

approach the relief requested by the plain

tiffs. In fact, the settlement agreement

simply does not satisfy the purpose underly

ing fair employment litigation which is to

make whole those persons injured by dis

criminatory employment practices. Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

"Additionally, the notices that were

sent out to back pay eligibles under the

Conciliation Agreement did not explain the

types and extent of relief in the agreement,

and did not explain the method by which

backpay was computed. Further, the affected

employees were not told that acceptance of

the agreement would be assumed if after the

passage of thirty days, the employees had not

responded to Gulf's notice...."

(JA 108, 109). See, infra n.67.

9/ See, supra, p. 4, n .4.

Plaintiffs' Complaint and Their Counsel

1 0 / .On May 18, 1976, plaintiffs-- filed this

suit as a class action in the United States

District Court, Eastern District of Texas, Hon.

Joe J. Fisher, Chief Judge, presiding. (JA 11).

The complaint alleged that "[b]lack employees of

Gulf Oil are, and have in the past, been victims

of systematic racial discrimination" by Gulf and

the unions. (JA 15);— ̂ The relief sought by the

- 9 -

10/ Plaintiff Wesley P. Bernard was hired by the

company in June 1954 as a laborer and at the time

of filing was a truck driver. Plaintiff Elton

Hayes, Sr. was hired in October 1946 as a laborer,

worked in various "helper" positions and at the

time of filing was a brickmaker. Plaintiff Hence

Brown, Jr. was hired as a laborer in 1954 and at

the time of filing was a truck driver. Plaintiff

Willie Whitley was hired as a laborer in 1946 and

retired as a utility man, a classification slight

ly above laborer, in October 1975. Plaintiff

Rodney Tizeno was originally hired as a laborer

and at the time of filing was employed as a

craftsman. Plaintiff Willie Johnson was hired as

a laborer. (JA 13, 14). Plaintiff Whitley died

in 1980.

11/ Among the areas in which discrimination was

alleged were: hiring and initial job assignments;

- 10 -

complaint included recruitment of blacks and the

following measures for incumbent employees: (a)

use of company seniority in bidding for better

paying and more desirable jobs; (b) restructuring

lines of progression, revision of residency

requirements, advanced level entry and job skip

ping; (c) training; (d) back pay; (e) rate protec

tion so black employees will not be deterred from

advancement; (f) prospective "red circling" to

alleviate the residual effects of discrimination;

(g) suspension of all tests and other criteria for

promotion and initial employment until the tests

and criteria are validated; (h) requiring the

local union to process grievances of its black

members; and (i) a declaration that the acts and

11/ continued

use of unvalidated and discriminatory tests and a

high school diploma requirement; exclusion from

craft and journeymen positions; racially separate

lines of progression, job classifications and

departments; denial of promotional training

opportunities; unequal pay for comparable work;

exercise of seniority rights; exclusion from

supervisory, technical, professional and clerical

positions; discipline and discharge; and the

acquiescence in or condoning of unlawful disc

rimination by the unions. (JA 15-18).

11

practices complained of violate federal law. (JA

18-20). The complaint also specifically prayed

for an award of costs, including reasonable

attorneys' fees pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-

5(k). (JA 20).

Plaintiffs and the potential class were

represented by attorneys associated with the NAACP

Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (herein

after "NAACP Legal Defense Fund" or "LDF"), a

non-profit corporation engaged in furnishing legal

assistance in cases involving claims of racial

12 /discrimination. (JA 111):— Three of plaintiffs'

12/ The NAACP Legal Defense Fund, which is

entirely separate and apart from the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People,

has been approved by the Appellate Division of the

State of New York to function as a legal aid

organization. (Id.) This Court has recognized the

LDF as having "a corporate reputation for expert

ness in presenting and arguing the difficult

questions of law that frequently arise in civil

rights litigation" and engaged in "a different

matter from the oppressive, malicious or avarici

ous use of the legal process for purely private

gain." NAACP v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 433.

Employment discrimination cases in which LDF

counsel have appeared in this Court include

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971);

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975);

12

counsel--Jack Greenberg, Barry L. Goldstein and

Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux— were employed by the Fund

as staff attorneys. (JA 81-82 n.l, 111, 115).

Stella M. Morrison of Port Arthur, Texas, and

Charles E. Cotton of New Orleans, Louisiana,

private practitioners with experience in fair

employment litigation, were associated with the

NAACP Legal Defense Fund as local counsel. (JA

13/81-82 n.l, 118).“ None of the attorneys has

accepted or expects to receive any compensa

tion from the named plaintiffs, from any plain

tiffs who may be added, or from any members of the

potential class. (JA 113, 119). Any counsel fees

which they might obtain would come from an award

12/ continued

and Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976). Attorneys employed by the LDF have

represented individuals in hundreds of civil

rights cases in the Fifth Circuit and in the

district courts of that Circuit. Mi 1ler v .

Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 534, 539

n.14 (5th Cir. 1970).

13/ See, NAACP v. Button, supra 371 U.S. at 421,

nT5. Since 1976, Mr. Thibodeaux has gone into

private practice in Lake Charles, Louisiana.

He remains one of plaintiffs' counsel.

13

by the court which, as expressly prayed for in the

complaint (JA 20), would be taxed against defen

dants pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 200Qe-5(k). (JA

113, 119). Any award of fees to staff attorneys

of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund would be paid over

to LDF for support of its programs. (JA 113).

The May 28 Order

On May 22, 1976, four days after the com

plaint was filed, the named plaintiffs held a

meeting in Port Arthur which was attended by

members of the potential class. (JA 115, 118).

Three attorneys for the named plaintiffs and

potential class accepted an invitation to attend

the meeting to discuss issues in the suit, types

of relief requested, and administrative and legal

problems in fair employment litigation, and to

answer questions about the suit and conciliation

agreement. (JA 116).

Five days after the meeting, Gulf filed a

short motion, unverified and unsupported by any

sworn statement, to limit communications with any

potential or actual class member. (JA 21). The

- 14 -

motion was filed in Judge Fisher's absence and

sought entry of an order pending his return. In

its supporting memorandum (JA 22), Gulf's counsel

described the conciliation agreement, set forth

Gulf's efforts to tender back pay awards and

solicit releases, and announced that Gulf had

suspended mailings to employees pending court

action. Counsel also asserted, without identify

ing any informant, that one of plaintiffs' counsel

made allegedly unethical and improper statements

14/at the May 22 meeting.— - The memorandum sought

14/ "... [0]n Saturday, May 22, 1976, four

days after the Complaint was filed in this

action, an attorney for the Plaintiffs, Mr.

Ulysses Gene Thibodeaux, appeared before

approximately 75 actual or potential class

members at a meeting in Port Arthur and

discussed with them the issues involved in

the case and recommended to those employees

that they not sign the receipt and general

release which has been mailed to them pur

suant to the Conciliation Agreement. In

fact, it is reported to Gulf that Mr Thibo

deaux advised this group that they should

mail back to Gulf the checks they had

received since he could recover at least

double the amount which was paid to them

15

entry of a proposed order limiting communication

15/in order to "preserve the status quo."— ■ Gulf's

proposed order was taken verbatim from "Sample

Pretrial Order No. 15: Prevention of Potential

Abuse of Class Action," Manual for Complex and

Multidistrict Litigation (1970) p. 197. (Id.)-i^

Plaintiffs had no opportunity to submit contraven

ing proof or to reply prior to the court's order.

The next day, District Judge William M.

Steger granted the motion and entered Gulf's

14/ continued

under the Conciliation Agreement by prosecut

ing the present lawsuit."

(JA 23, 24).

15/ Although Gulf now characterizes its motion as

an "emergency" motion, Br. p. 5, none of the

requisites for affidavit or verified pleading,

hearing or notice for either a temporary restrain

ing order or preliminary injunction were pleaded

or supplied. Rule 65, Fed. R. Civ. Pro.

16/ Attached to the memorandum were the concilia

tion agreement and a letter from company counsel

suspending further mailing of checks and other

contacts pursuant to the conciliation agree

ment. (JA 26, 43).

- 16 -

proposed order ex parte. (JA 1).-— ■ By its

terms, the order forbade, without exception, all

communications by parties or their counsel with

any class member pending Judge Fisher's return.

The text of the order is set forth in the Joint

Appendix at pages 44-45. The order states that

parties and their counsel "are forbidden directly

or indirectly, orally or in writing, to commu

nicate concerning such action with any potential

or actual class members not a formal party to the

action." Id_. The forbidden communications

included, but were not limited to, (a) solicita

tion of legal representation, (b) solicitation of

fees, expenses and arrangements to pay fees and ex-

17/ Gulf no longer maintains that the May 28

or*der was entered "without formal objection by

Respondents." Compare, Petition for a Writ of

Certiorari, p. 7, with, Br, p 5. Gulf represented

in both courts below that Judge Steger's order was

issued after hearing argument of counsel for

plaintiffs and the company. (See, e.g., JA 48,

202). However, the record shows that the motion

was granted ex parte with no argument or hearing.

(JA 3). Plaintiffs filed a memorandum of law in

opposition to the motion on June 10, 1976, only

after receipt of notice of the court's order

and, indeed, after the filing of Gulf's subsequent

motion to modify the order. (JA 46). See,

JA 4, 80.

17 -

penses, (c) solicitation to opt out of Rule

23(b)(3) actions, and (d) communications "which

may tend to misrepresent the status, purposes and

effects of the class action, and of impressions

tending, without cause, to reflect adversely on

any party, any counsel, the Court, or any adminis

tration of justice." (Id.) No findings of fact

or conclusions of law were made, and the Fifth

Circuit considered Gulf's allegations of abuse

"irrelevant." (JA 195 n.14, 209-210 and n.9, 241

and n .7 0).

The June 22 Order

On June 8, 1976, Gulf filed a motion to

modify the May 28 order'"to allow Gulf to comply

with the terms of the Conciliation Agreement . . .

by resuming under the Court's supervision the

payment of back pay awards to employees covered by

the Conciliation Agreement and obtaining from

those employees receipts and releases all as

provided for by the terms of the Conciliation

Agreement." (JA 46). The supporting memorandum

reiterated statements "reported to Gulf" about

plaintiffs' counsel at the May 22 meeting, and

- 18 -

added that: "In fact, it is reported that Mr.

Thibodeaux stated even if the employee had signed

the receipt and release, he should now return the

check which had been mailed to the employee by

Gulf." (JA 47). Again, Gulf declined to provide

any support for its hearsay allegations. However,

Gulf did again attach the conciliation agreement

and, in addition, the sworn affidavits of offi

cials of the EEOC and Department of the Interior.

(JA 71, 76) . —

On June 11, 1976, the district court heard

argument of counsel, but heard no witnesses and

took no evidence. (See, JA 203, 235). Thereafter,

Gulf submitted a supplemental legal memorandum,

a copy of the Manual for Complex Litigation

(1973), Part II, § 1.41 Sample Pretrial Order No.

15, and a proposed order. (JA 92, 97, 99).

Plaintiffs filed affidavits of counsel, which

18/ The officials, who participated in the

negotiation of the conciliation agreement, stated

that, in their opinion, the agreement was a

thorough and effective solution to charges that

Gulf discriminated at its Port Arthur refinery in

violation of Title VII, and that Gulf should be

allowed to proceed with completing back pay awards

and receiving releases under the conciliation

agreement. (Id.)

19

stated that plaintiffs were represented by counsel

associated with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund,

explained the nature of the Fund's work, and

stated that the only compensation plaintiffs'

counsel expected would be through statutory

taxation of costs and fees. (JA 107, n.l, 111,

115, 118). The affidavit of Mr. Thibodeaux

directly contravened Gulf's account of his state-

19/ments at the May 22 meeting.— The affidavit of

Ms. Morrison, another of plaintiffs' counsel who

attended the meeting, corroborated Mr. Thibo

deaux's affidavit. (JA 118). Counsel also

averred that to date 34 individual members of the

class had signed retainer agreements with plain-

19/

"7l. Contrary to the Company's assertion in

its memoranda filed on May 27 and June 8,

1976, I did not at any time during the course

of the meeting advise actual or potential

class members not to accept the defendant's

offer of settlement, nor did I state to the

assembled group that counsel for the plain

tiffs could obtain twice the amount of

backpay for the class as has been offered to

them under the Conciliation Agreement

of April 14, 1976."

(JA 116).

- 20 -

tiffs' counsel to represent them in the litiga

tion. (JA 119).

The affidavits of plaintiffs' counsel

stated that communication with potential class

members was necessary for effective representation

of claims of class members, defining the scope of

the issues, investigating claims of systematic and

individual discrimination, preparing witnesses,

supplementing available documentary materials and

completing discovery, and generally informing

class members of their rights and answering

20 /questions. (JA 113, 114, 116, 117).—

On June 22, 1976, the district court modified

the May.28 order, and adopted Gulf's proposed

order based on the Manual for Complex Litigation.

The June 22 order restrained communications by

the parties and their counsel with members of the

potential class, while authorizing the clerk of

court to send a notice to class members offering

20/ Plaintiffs also addressed Gulf's claim that

the conciliation agreement was a thorough and

effective resolution of employment discrimination

at the Port Arthur refinery. See, supra, pp. 7-8,

n. 8.

- 21 -

back pay and soliciting releases under the con

ciliation agreement. The complete text of the

order is reprinted in the Joint Appendix at pages

124-127, 189-191, n.9, and 236-238, n.4. The

order reiterated the prohibition in the May 28

order, see, supra, at pp. 16-17, with two excep

tions, viz., communications initiated by a client

or prospective client, and communications by a

public office or agency which do not have the

effect of solicitation of representation or

misrepresenting the action or orders. The order

also provided that:

"If any party or counsel for a party

asserts a constitutional right to communicate

with any members of the class without prior

restraint and does so communicate pursuant

to that asserted right, he shall within five

days after such communication, file with the

Court a copy of such communication, if in

writing, or an accurate and substantially

complete summary of the communication if

oral."

(JA 125).

The court, relying on the Manual for Complex Liti

gation, rejected the contention that the restraint

of communications was unconstitutional. The order

also provided that Gulf be allowed to proceed with

- 22 -

the payment of back pay awards and obtaining of

receipts and releases from those employees covered

by the conciliation agreement and that the clerk

of court mail an attached notice to each covered

employee concerning acceptance of the offer within

45 days, and the order set forth a timetable for

employee acceptances and for Gulf's reporting of

acceptances.

The basis for entry of the order was not

explained and no findings of fact or conclu

sions of law were made. "We can assume that the

district court did not ground its order on a

conclusion that the charges of misconduct made by

Gulf were true. Nothing in its order indicates

that it did, and, if it did, such a conclusion

would have been procedurally improper and without

evidentiary support." (JA 241) (Fifth Circuit en

banc opinion).— —^

21/ Petitioners erroneously refer to certain

""Facts supporting entry of the order." Br. pp.

22-23 and n.18, p. 25.

Judge Godbold noted that "Gulf restates

hearsay as though it were fact proved and found."

(JA 210, n .9). In this Court, Gulf continues

to reiterate the alleged statements of plaintiffs'

counsel. See, Br., pp. 5, 23 and n.18. The

23

The August 10 Order

The broad scope of the June 22 order was soon

confirmed. On July 6, 1976, plaintiffs moved (a)

for permission for themselves and their counsel to

contact and interview members of the proposed

class, and (b) to declare that an attached leaflet

is "within the constitutionally protected rights

of the plaintiffs and their counsel" and to permit

its dissemination within the 45 day period allowed

for members of the class to respond to the con

ciliation agreement tender pursuant to the June

21/ cont inued

unsworn hearsay was rebutted by direct affidavit,

which was the* only evidence before the court.

Gulf could have, but did not, present any counter

vailing proof.

The suggestions that the June 22 order was

issued upon a complete record showing the class

action process was threatened by abuse and after a

hearing, see, Br, p. 22 and n.16, are also

erroneous. Of the five affidavits submitted, the

only affidavits on abuse were those of plaintiffs'

counsel, which demonstrated that no unethical or

improper conduct had occurred or was likely to

occur. See, supra at p. 19. There was no evi

dentiary hearing. The district court merely heard

oral argument by counsel, and Gulf never produced

any evidence to substantiate its unsworn hearsay

allegations. See, supra at p. 18.

- 24

22 order. (JA 130-131). The leaflet, inter alia,

advised Gulf's black employees to consult a lawyer

about the conciliation releases, offered the

names, addresses and telephone numbers of several

of plaintiffs' counsel for free consultation, and

described the lawsuit. The original leaflet is

reproduced in Addendum B to this brief.

Plaintiffs' motion for permission to communi

cate with the proposed class was denied on August

10, 1976, two days after the 45 day period for

acceptance of back pay tenders had expired. (JA

157, see, 208, 236). The district court's order

consisted of one sentence stating "that the Motion

is hereby denied." (JA 157). No findings of fact

or conclusions of law were made.

Other Proceedings

On January 11, 1977, the district court

granted summary judgment for Gulf and the unions,

dismissing the complaint as untimely. (JA 170).

On appeal, a panel of the Fifth Circuit unanimous

ly reversed the dismissal of the complaint but, by

a divided court, affirmed the orders restraining

25

communications. (JA 175). Judge Godbold filed an

extensive dissent on the communications issue.

(JA 199).

On rehearing eii banc, the Fifth Circuit, in

an opinion authored by Judge Godbold, adopted the

panel opinion insofar as it reversed the district

court's dismissal of the complaint. (JA 231,

234). By a vote of twenty-one to one, the en banc

court also reversed the orders restraining commu

nications. (Id.) Thirteen members of the court

held that the orders violated both the First

Amendment and Rule 23, Fed. R. Civ. Pro. (Id.)

Eight judges, agreeing that the orders were not

authorized as "appropriate order[s]" under Rule

23, did not reach the constitutional issue. (JA

269, 276).

On December 8, 1980, the Court granted a writ

of certiorari limited to the question of the

validity of the orders restraining communications.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

1. Communication by plaintiffs and their

counsel with potential class members in a civil

rights action, like other "'collective activity

26

undertaken to obtain meaningful access to the

courts [,] is a fundamental right within the

protection of the First A m e n d m e n t . In re Primus,

436 U.S. 412, 426 (1978). Indeed, the right was

first recognized in NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.

415 (1963), in the context of communication

by NAACP and NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyers

with putative plaintiffs concerning their par

ticipation in potential civil rights class

action lawsuits.

2. The district court's orders restrain

ing communication by plaintiffs and their counsel

with the potential class were entered without any

proof of actual or imminent specific misconduct

or other injury. First Amendment rights cannot

be impaired without such a threshold showing.

The Manual for Complex Litigation simply does not

provide particularized proof of misconduct ade

quate to justify any infringement.

3. The orders barring communication are

unjustified prior restraints of protected ex

pression and association. The provision in

the June 22, 1976, order for assertion of "a

constitutional right to communication" on pain

27

of criminal contempt does not require a different

result because the orders remain a system of

prior restraint which substantially burdens

exercise of protected liberties.

4. The district court’s orders are over

broad restraints in violation of the First Amend

ment rule that ”[p]recision of regulation must be

the touchstone in an area so closely touching our

most precious freedoms." NAACP v. Button, 371

U.S. 415, 438 (1963).

5. In addition, the orders restraining

communication compromised the integrity of the

proceedings, and denied important rights of

plaintiffs and the potential class guaranteed by

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment. In

particular, adequate information, effective

assistance of counsel, and an adequate hearing and

procedural regularity were denied in violation of

the Fifth Amendment.

6. Last, the district court's gag orders

impede the prosecution and processing of class

actions and, therefore, are inconsistent with Rule

23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which

permits only "appropriate order[s],f to be issued.

Rule 23(d). The orders forbade plaintiffs and

their counsel from engaging in activities "direct

- 28 -

ed toward effectuating the purposes of Rule 23 by

encouraging common participation in the litigation

of ... discrimination claim[s]." Coles v. Marsh,

560 F . 2d 186, 189 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 434

U.S. 985 (1977). Moreover, Rule 23 should be

construed to avoid grave doubts of unconstitu-

t ionality.

ARGUMENT

The record below is a virtual catalogue of

the disruption that can be caused in Rule 23

actions by orders and local rules such as those

recommended by §1.41 of the Manual for Complex

Litigation, restraining communication by plain

tiffs and their counsel with members of the

2 2 / . .potential class.— The ability of plaintiffs

22/ The Manual for Complex Litigation (1978),

prepared by a Board of Editors for the Federal

Judicial Center and Judicial Panel on Multidis

trict Litigation, is reprinted in 1 Pt. 2 Moore's

Federal Practice (2d ed. 1980) (hereinafter "Manu

al"). The Manual's Suggested Local Rule No. 7 and

Sample Pretrial Order No. 15 are substantially

identical. See, Manual, Pt. II, 225-228. The

Manual is presently being revised. See Res

- 29

and counsel to prosecute, and proper judicial

management of the action both were grievously

impaired.

The issue is not whether courts are powerless

23/to deal with misconduct by counsel.-— ■ The

record reveals no findings of misconduct, and

petitioners' unsupported allegations, reiterated

here, were properly treated by all the Fifth

Circuit opinions as "irrelevant." Nor is the

Court presented with orders "drawn as narrowly

as possible," Br, p. 8. The plain terms and

operation of the orders simply explode such a

22/ continued

pondents' Brief in Opposition to the Petition, pp.

18-19. Although a local rule is not before the

Court, the same analysis under the Constitution

and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure applies

to both rules and orders. See, JA 241 n.6, 252 n.

22 (Fifth Circuit en banc opinion).

23/ Where there has been misconduct by counsel,

" [t ]he ordinary remedy is disciplinary action

against the lawyer and remedial notice to class

members." Halverson v. Convenient Food Mart,

Inc., 458 F .2d 927, 932 (7th Cir. 19721.

- 30

characterization. The May 28 order prohibited

"all" communication by its terms and effect.

See, supra at 16. The June 22 order prohibit

ed "all" communications with four exceptions, but

only one, the provision for "assert[ing] a

constitutional right to communicate" as peti

tioners recognize, Br, p. 10, is of any conceiv-

24/able significance here.— The scope of the

undefined protection offered by the provision is

uncertain, and any possibility that the June 22

order could be saved by any such "escape hatch"

was ruled out by the order of August 10 flatly

denying any right to communicate with the class

members. See, supra at pp. 23-24.

Nor is the Court presented with restraints

based on "an overriding interest articulated

in findings ..." Richmond Newspapers, Inc, v. Vir

ginia, U.S. , 65 L.Ed. 2d 973, 992 (1980).

Although petitioners attempt to fill the gap by

variously suggesting that the orders were issued

24/ Petitioners advance no reason why the May

T8 order was proper even though its ban on commu

nications was the very kind of formal absolute

prior restraint which they argue the June 22 order

is not. Br, p. 10.

31

to "monitor" communications, to prevent generalized

"threatened abuse" of the class action device or

to forestall unspecified "misrepresentation,"

e.g. , Br, pp. 17-26, the orders stated no purpose

and none of the purposes now attributed to the

district court have record support. Because

plaintiffs and their counsel were completely

gagged, a_ fortiori, no monitoring of their

communication occurred. The district court's

denial of plaintiffs' motion to communicate

about pending back pay tenders and waivers was

denied two days after the termination of the

period for acceptance by the class members. Not

only were no findings made, but no basis exists

for finding any threat of abuse or misrepresenta

tion. See, supra at pp. 14-19.

Petitioners' case boils down to the naked

claim that "the very nature of the unique class

action device creates sufficient justifica

tion for the entry of the order[s]." Br, p. 11.

Plaintiffs' efforts to bring to the court's

attention the adverse impact of its orders on the

processing of the action were necessarily unavail

ing because the orders were not bottomed on

- 32

specific circumstances. They are restraints

derived from §1.41 of the Manual, which recommends

that in all class action suits, whether certified

or not, communications by parties or counsel with

actual and potential class members should be

restricted. Id. at 31-32. The basis for this

recommendation is the Manual's conclusion that

"[t]he class action under Rule 23 is subject to

abuse, intentional and inadvertent, unless proce

dures are devised and employed to anticipate

abuse." Id. at 31. The Manual, however, concedes

that abuse is the "exception rather than the rule"

23 /and "relatively rare."—

Petitioners ' brief invites this Court merely

to sanction the exercise of Rule 23(d) supervisory

25/ "It must be noted, however, that generally the

experience of the courts in class actions

has been favorable. The aforementioned

abuses are the exceptions in class action

litigation rather than the rule. Neverthe

less, they support the idea that it is

appropriate to guard against the occurrence

of these relatively rare abuses by local rule

or order."

Manual at 36-37. As we demonstrate later, this line

of reasoning has no support in the jurisprudence

of this Court. See, part I of the argument.

33

power. Br, p. 14. This characterization ignores

that the communication subject to restraint is

protected by the Constitution. Plainly, govern

ment "cannot foreclose the exercise of constitu

tional rights by mere labels" and "may not

under the guise of prohibiting professional

misconduct, ignore constitutional rights." NAACP

v. Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 429, 439. The Court

has

"repeatedly held that laws which actually

affect the exercise of these vital rights

cannot be sustained merely because they were

enacted for the purpose of dealing with some

evil within [governmental] competence, or

even because the laws do in fact provide a

helpful means of dealing with such an evil

... [B]road rules framed to protect the

public and to preserve respect for the

administration of justice can in their actual

operation significantly impair the value of

associational freedoms."

United Mine Workers v. Illinois Bar Association,

~ — ' , 167389 U.S. 217, 222 (1967).—

26/ First Amendment freedoms are protected "not

only against heavy-handed frontal attack, but also

from being stifled by more subtle governmental

- 34 -

I

THE ORDERS RESTRAINING COMMUNICATION DENIED

PLAINTIFFS, THEIR COUNSEL AND POTENTIAL CLASS

MEMBERS MEANINGFUL ACCESS TO THE COURTS IN

VIOLATION OF THE FIRST AMENDMENT.

A. Expression and Association To Advance

Litigation Are Rights Protected by

the First Amendment.

1. The Principle of NAACP v. Button

The Court has recently reaffirmed the princi

ple, first recognized in NAACP v. Button, supra,

that "'collective activity undertaken to obtain

meaningful access to the courts is a fundamental

right within the protection of the First Amend

ment."' In re Primus, supra, 436 U.S. at 426,

quot ing United Transportation Union v. State Bar

of Michigan, 401 U.S. 576, 585 (1971). "[Ab

stract discussion is not the only species of com

munication which the Constitution protects; the

26/ continued

interference." Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S.

516, 523 (1960); see, Shelton v. Tucker, 364

U.S. 479 (1960); Gibson v. Florida Legislative

Investigation Comm., 372 U.S. 539 (1963).

- 35

First Amendment also protects vigorous advocacy,

certainly of lawful ends, against government

intrusion." Button, supra, 371 U.S. at 429.

The right of association for litigation was

recognized in Button in the context of communica

tion by NAACP and NAACP Legal Defense Fund attor

neys with potential civil rights plaintiffs, both

members and non-members. One purpose of the

communication was to provide information about

participation in class action challenges to public

school segregation. The Court held that these

communications are not unlawful and unethical

solicitation of legal representation. 371 U.S. at

428-29.

"In the context of NAACP objectives, litiga

tion is not a technique for resolving private

differences; it is a means for achieving the

lawful objectives of equality of treatment by

all government, federal, state and local,

for the members of the Negro community in

this country. It is thus a form of political

expression. Groups which find themselves

unable to achieve their objectives through

the ballot frequently turn to the courts.

Just as it was true for the opponents of New

Deal legislation during the 1930's, for

example, no less is it true of the Negro

- 36

minority today. And under the conditions

of modern government, litigation may well be

the sole practicable avenue open to a minor

ity to petition for redress of grievances."

371 U.S. at 429-30.

Traditional rules against solicitation do not

apply to "wholesome and beneficial" public in

terest litigation where legal services are offered

to clients free of charge. See, e.g. , ABA Com

mittee on Professional Ethics and Grievances,

Opinions, No. 148, 1935 (1957), cited by Button,

371 U.S. at 430 n. 13, 440 n. 19, 443 n. 26.--

Button specifically ruled that the "superficial

resemblance in form" between unethical arrange

ments for private gain which served no public

interest, and the activities of NAACP and NAACP

Legal Defense Fund lawyers

27/ Opinion 148 approved the Liberty League's

program of assisting litigation challenging New

Deal legislation through a National Lawyers

Committee which sought to disseminate through

public media communications on the constitu

tionality of state and federal legislation, and to

offer counsel, without fee or charge, to anyone

financially unable to retain counsel who felt that

such legislation violated his constitutional

rights. See other authorities cited in Button,

371 U.S. at 440 n.19.

- 37

"cannot obscure the vital fact that here

the entire arrangement employs constitutionally

privileged means of expression to secure consti

tutionally guaranteed civil rights.

* * *

"Resort to the courts to seek vindication

of constitutional rights is a different matter

from the oppressive, malicious, or avaricious

use of the legal process for purely private

gain."

371 U.S. at 442-43.

Efforts to confine the scope of the Button

doctrine have been uniformly denied. Thus,

it was recognized that "the First Amendment's

guarantees of free speech, petition and assembly

give railroad workers the right to gather together

for the lawful purpose of helping and advising

one another in asserting the rights Congress gave

them in the Safety Appliance Act [45 U.S.C. §1 et

seq.] and the Federal Employers' Liability Act [45

U.S.C. §51 et_ seq.]." Brotherhood of Railroad

Trainmen v. Virginia, 377 U.S. 1, 5 (1964).

Unlike the precise facts in Button, the legal

» 38

rights involved were statutory, and the union

recommended outside counsel whom it did not employ

itself. Nevertheless, the Court held that "the

Constitution protects the associational rights of

the members of the union precisely as it does

those of the NAACP." 377 U.S. at 8.-^^ United

Mine Workers v. Illinois Bar Association, 389 U.S.

217 (1967), declined to limit the Button principle

to prohibit union members from collectively hiring

an attorney to litigate damage claims for personal

injury and death under a state workers compensa

tion act. A state court's order barring, inter

alia, a union's efforts to limit the fee charged

by recommended attorneys in damage suits to a

percentage of recovery under the Federal Employ

ers ' Liability Act, was reversed in United Trans

portation Union v. State Bar of Michigan, 401 U.S.

576 (1971). Again, the Court asserted that "the

principle here involved cannot be limited to the

28/ "The State can no more keep these workers

from using their cooperative plan to advise

one another than it could use more direct

means to bar them from resorting to the

courts to vindicate their rights. The right

to petition the courts cannot be so handi

capped." 377 U.S. at 7.

- 39 -

facts of this case. At issue is the basic right

to group legal action ..." 401 U.S. at 585.

The principle of Button and its progeny was

recently affirmed in In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412

(1978), where the Court reversed the disciplining

of an attorney who advised a lay person of her

legal rights concerning her sterilization.

Counsel had sent a letter offering free legal

assistance on behalf of the American Civil

Liberties Union, a non-profit orginization with

which the lawyer was affiliated, in order to bring

a class action. Primus understood Button and

subsequent decisions as having established the

principle that association and expression on

behalf of litigation are fundamental First Amend

ment rights.

"Without denying the power of the State to

take measures to correct the substantive

evils of undue influence, overreaching,

misrepresentation, invasion of privacy,

conflict of interest, and lay interference

that potentially are present in solicitation

of prospective clients by lawyers, this Court

has required that 'broad rules framed to

protect the public and to preserve respect

for the administration of justice' must not

work a significant impairment of 'the value

of associational freedoms.'"

- 40

436 U.S. at 426, quoting Mine Workers, supra, 389

U.S. at 222. The Court rejected efforts to limit

the group litigation principle, by declining to

distinguish Button because the ACLU might benefit

financially from the litigation by a possible

statutory award of attorneys' fees. 436 U.S. at

427-431.— /

Petitioners, however, do not acknowledge

the "fundamental" nature of the right. Their

characterization of the "generalized first

amendment concerns of parties and their counsel"

(Br, p. 10) deprecates Button and its progeny, and

blinks at reality. The right of association and

expression for litigation is not some abstract

29/ The Court ruled that "the ACLU's policy

of requesting an award of counsel fees does not

take this case outside of the protection of

Button." 436 U.S. at 429. The opinion relied

on the fact that the NAACP and the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund (the organizations involved in

Button) often request fees. The Court noted that

"differences between counsel fees awarded by a

court and traditional fee-paying arrangements ...

militate against a presumption that ACLU sponsor

ship of litigation is motivated by considerations

of pecuniary gain rather than by its widely

recognized goals of vindicating civil liberties."

Id. at 429-430. For LDF lawyers, as well as ACLU

- 41

privilege of no significant moment: its denial

infringes "the right of individuals and the public

to be fairly represented in lawsuits authorized by

Congress to effectuate a basic public interest."

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Virginia,

supra, 377 U.S. at 7. In the instant case,

prohibiting communication by plaintiffs and NAACP

29/ continued

lawyers, "[cjounsel fees are awarded in the

discretion of the court; awards are not drawn from

the plaintiff's recovery, and are usually premised

on a successful outcome." Ld_. at 430. The

provision for statutory awards of attorney's fees

from defendants distinguishes this litigation from

contingency fee litigation in which fees are paid

from the recovery. In the latter case, an incen

tive to enlarge the class may exist because of

"the prospect of reducing [plaintiffs'] costs of

litigation, particularly attorney's fees, by

allocating such costs among all members of the

class who benefit from any recovery." Deposit

Guaranty Nat'l. Bank v. Roper, 445 U.S. 326, 338

n.9 (1980). Moreover, in civil rights cases the

size of the class ordinarily has no bearing on the

amount of fees, see, Zarate v, Younglove, 8 6

F.R.D. 80, 98 (C.D. Cal. 1980), which depends on

statutory criteria. See, e.g., Copeland v.

Marshall, 24 EPD 131,219 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (en

banc); Northcross v. Board of Education, 611 F .2d

624, 632 et seq. (6 th Cir. 1979), cert, denied,

100 S. Ct. 2999, 3000 (1980). ~

- 42 -

Legal Defense Fund counsel with potential class

members impaired the plaintiffs' right to be

"fairly represented," barred LDF attorneys

from effectively prosecuting the action and

from dissemination of critical information about

the lawsuit and conciliation agreement to similar

ly situated black persons, and altogether denied

the potential class "meaningful access to the

courts." Button, 377 U.S. at 426. It is a

"commonsense proposition" that such activity is

protected. United Transportation Union v. State

30 /Bar of Michigan, supra, 401 U.S. at 5 80.— -

Petitioners argue that the Button principle

does not apply because "the order was entered

during ongoing litigation." Br, p. 29 n.29.

This contention, like those rejected in the union

30/ The purported conflict between the "competing

values" of First Amendment command and a court's

authority to impose broad prior restraint to

protect against potential abuse (Br, p. 10) was

resolved in Button and its progeny. "[W]e look at

the [order] like we look at a statute, and if upon

its face it abridges rights guaranteed by the

First Amendment, it should be struck down."

United Transportation Union, supra, 401 U.S. at

581.

- 43

referral cases and In re Primus, seeks to distin

guish Button on its facts. But the constitutional

right, as this Court has repeatedly said, is a

broad protection for "collective activity under

taken to obtain meaningful access to the courts,"

and "the basic right to group legal action."

United Transportation Union, supra, 401 U.S. at

585 (emphasis added). Nothing in the nature of

the right to associate for litigation suggests

that it terminates with the filing of the

action. Indeed, the practical need for communica

tion to prosecute, advance and develop litigation

increases rather than diminishes with the filing

of an action. See part II of the argument.

Moreover, in the instant case the prohibited

communications were with potential class members

who had to make a choice to participate in the

lawsuit or to accept back pay under the concilia

tion agreement. Such persons in substance

are in the same position as the potential plain

tiffs in Button, the union members in the post-

Button^ cases, or the potential plaintiff in In re

Primus. Congress has determined that when a civil

rights plaintiff obtains relief "he does so not

for himself alone but also as a "private attorney-

- 44 -

general,' vindicating a policy that Congress

considered of the highest priority." Newman v .

Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400, 401,

402 (1968); Trafficante v. Metropolitan Life

Insurance Co., 409 U.S. 205, 211 (1972); Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 415 (1975).

Congress has therefore provided the courts with

3 1 /broad remedial powers— ■ and has authorized

awards of counsel fees to encourage private

32/attorney general enforcement of civil rights.——

The Button principle has been applied outside

33/the civil rights and civil liberties areas.——

31/ Section 706(g) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

J2000e-5(g). See, Pranks v. Bowman Transporta

tion Co., 424 U.S. 747, 763-764 (1976).

32/ Section 706(k) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

T2000e-5(k); Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards

Act of 1976, 42 U.S.C. §1988. See, Christiansburg

Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 4X2 (1978); Newman

v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., supra; see

generally, S"I Rep. No. 94-1011, The Civil Rights

Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976, 94th Cong.,

2d Sess. (1976).

33/ See, Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, supra

(Safety Appliance Act and FELA); United Mine

Workers, supra (state workers' compensationlaw);

- 45

The instant litigation therefore is well within

the core of protected activity.

B . The Orders Infringe Upon First Amendment

Rights Without Requisite Proof Of

Misconduct.

1. Absence of Proof of Misconduct

At a minimum, the First Amendment rights at

stake cannot be infringed without proof of

33/ continued

United Transportation Union, supra (FELA).

Although this Court need not decide the question,

the right of associational activity in support of

litigation should apply to any controversy proper

for judicial resolution. Although this is

an action for equitable relief, and not a damage

suit, there is no distinction for purposes of

associational rights since either form of relief

may constitute proper enforcement of public

policy. See, Button, supra (equitable school

desegregation action); Brotherhood of Railroad

Trainmen, supra; United Mine Workers, supra;

United Transportation Union, supra; In re Primus,

supra (damage suits).

- 46

specific misconduct. However, "[n]othing that

this record shows as to the nature and purpose of

NAACP [Legal Defense Fund] activities permits an

inference of any [conduct] injurious" to the

processing of the lawsuit. NAACP v. Button,

34/supra, 371 U.S. at 444.— '

Reciting "potential abuse" cannot cure the

constitutional defect.

"[L]aws which actually affect the exercise of

these vital rights cannot be sustained merely