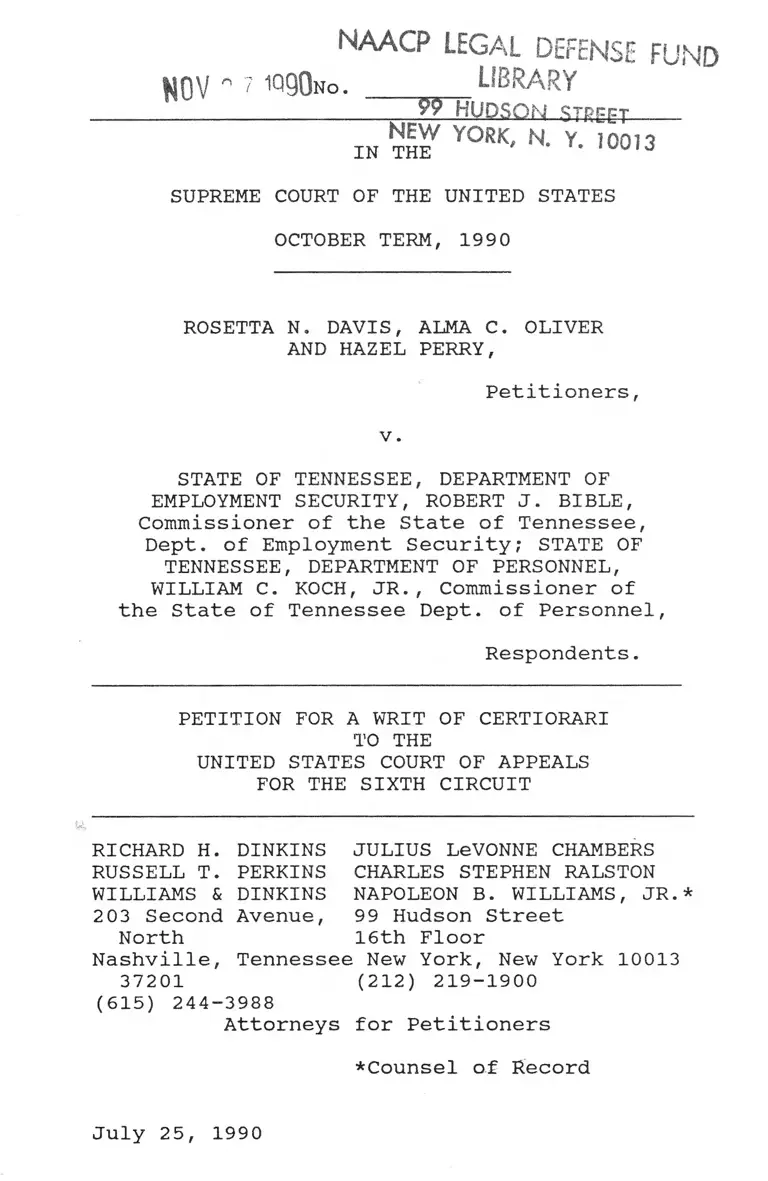

Davis v. Tennessee Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

July 25, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Davis v. Tennessee Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1990. 15ccd858-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/23384758-e967-41fc-97a1-e4846646303c/davis-v-tennessee-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

NOV n 7 1090no. LIBRARY

99 HUDSON STREET

NEW YORK, N. Y. 10013IN THE *

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1990

ROSETTA N. DAVIS, ALMA C. OLIVER

AND HAZEL PERRY,

Petitioners,

v .

STATE OF TENNESSEE, DEPARTMENT OF

EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, ROBERT J. BIBLE,

Commissioner of the State of Tennessee,

Dept, of Employment Security; STATE OF

TENNESSEE, DEPARTMENT OF PERSONNEL,

WILLIAM C. KOCH, JR., Commissioner of

the State of Tennessee Dept, of Personnel,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

RICHARD H. DINKINS

RUSSELL T. PERKINS

WILLIAMS & DINKINS

203 Second Avenue,

North

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.*

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

Nashville, Tennessee New York, New York 10013

37201 (212) 219-1900

(615) 244-3988

Attorneys for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

July 25, 1990

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Whether the court of appeals

below erred in holding that the use of the

term "plaintiffs in the above action" in

the notice of appeal failed to meet the

specificity requirement of Rule 3(c) of the

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure?

II. Whether the court of appeals

erred in denying petitioners’ motion to

amend the notice of appeal, pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1653?

l -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..............

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............

OPINIONS BELOW ...................

JURISDICTION OF THE COURT ........

STATUTES ..........................

RULES .............................

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ............

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD

BE GRANTED ......................

I. THE COURT OF APPEALS DECIDED

AN IMPORTANT QUESTION OF

FEDERAL APPELLATE LAW WHICH

HAS NOT BEEN, BUT SHOULD BE,

SETTLED BY THIS COURT ......

II. IN HOLDING THAT PARTIES MUST

BE INDIVIDUALLY NAMED IN A

NOTICE OF APPEAL AND THAT

"ET AL." CANNOT BE USED TO

ASSIST IN IDENTIFYING PARTIES

TAKING AN APPEAL, THE DECISION

1

iii

1

2

3

3

3

13

13

Page

OF THE COURT

FLICT WITH TH

COURT'S DECIS _____ • • • 19

Page

III. THE COURT OF APPEALS SO FAR

DEPARTED FROM THE ACCEPTED

AND USUAL COURSE JUDICIAL

INTERPRETATION OF RULES AS

TO REQUIRE THIS COURT'S

SUPERVISION................. 24

IV. THE COURT OF APPEALS DECIDED

AN IMPORTANT QUESTION OF

FEDERAL LAW IN HOLDING THAT

THE DEFECT IN THE NOTICE OF

APPEAL COULD NOT BE CURED

UNDER 28 U.S.C. §1653 OR A

SUSPENSION OF RULE 3(C)

UNDER RULE 2, FED.R.APP.P. .. 27

CONCLUSION ........................ 3 0

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S. 178 (1962)

Houston v. Lack, U.S. 108

S.Ct. __, 101 L.Ed.2d 245 (1988)

National Center for Immigrants'

Rights, Inc. v. INS, 892 F.2d

814 (9th Cir. 1989) ............

23

24

18

27

18

Roschen v. Ward, 279 U.S. 722 ....

Santos-Martinez v. Soto Santiago,

863 F.2s 174 (1st Cir. 1988) ...

Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co.,

U.S. ___, 108 S.Ct. 2405,

101 L.Ed. 2d 285 (1988) ......... 6,7,11,13,14,15,16,17,18,20,

21,22,23,24,26,28

Statutes

28 U.S.C. §1653 8,28,29

Rules

Rule 2, Fed.R.App.P............... 29

Rule 3, Fed.R.App.P.............. 9,15,16,22,23,24,27

Rule 15(c), Fed.R.App.P........... 29

iv

OPINIONS BELOW

The order of the district court, filed

March 11, 1988 dismissing with prejudice

petitioners' claims under 42 U.S.C. §§

1981, 1983, and 1985, and under the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments, and

dismissing petitioners' pendent state

claims without prejudice. See, Appendix p.

9a.

The September 3, 1988 order of the

district court dismissing petitioners'

claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights

Statute, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seg. See,

Appendix p. 7a.

The October 7, 1988 order of the Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit dismissing

the appeal of petitioners. See Appendix p.

4a.

The February 28, 1989 order of the

court of appeals denying petitioners'

1

motion to amend and to suspend the rules.

See, Appendix p. la.

The April 26, 1990 opinion of the

court of appeals, on petition for rehearing

en banc, affirming the judgment of the

district court concerning the corporate

plaintiff Minority Employees, and

dismissing the appeal of the individual

appellants- plaintiffs Davis, Oliver, and

Perry for want of jurisdiction over the

appeal. See Appendix p. 13a.

JURISDICTION OF THE COURT

The judgment of the court of appeals

sought to be reviewed was entered on April

26, 1990. This Court has jurisdiction of

the petition for a writ of certiorari

pursuant to the terms of 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

Jurisdiction existed in the district court

under 28 U.S.C. § 1331.

2

STATUTES

28 U.S.C. § 1653: Defective

allegations of jurisdiction may be amended

upon terms, in the trial or appellate

courts.

RULES

Rule 3(c), Fed. R. App. P.

The notice of appeal shall specify the

party or parties taking the appeal.... An

appeal shall not be dismissed for

informality of form or title of the notice

of appeal.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On March 6, 1981, individual

petitioners Rosetta N. Davis, Alma C.

Oliver, and Hazel Perry, and plaintiff

corporation Minority Employees of the

Tennessee Department of Employment

Security, Inc., commenced this employment

discrimination action under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

3

42 U.S.C. § 2000e, and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983, 1985, and 1988, against respondents

State of Tennessee Department of Employment

Security, et al.

Petitioners Davis, Oliver, and Perry

alleged in the complaint that petitioners

failed to receive job promotions in the

respondent Tennessee Department of

Employment Security as a result of

respondents' unlawful, racially

discriminatory promotional policies and

procedures.

Plaintiff Minority Employees of the

Tennessee Department of Employment

Security, Inc. was formed to assist

minorities in being hired and promoted in

the Tennessee Department of Employment

Security.

Petitioners brought this action to

prevent respondents from implementing

employment practices that unlawfully

4

discriminate against plaintiffs and other

African-Americans.

On April 28, 1982, the district court

denied class certification. On September

3, 1986, it dismissed plaintiffs1 claims

under Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

On March 9, 1988, the District Court

dismissed, with prejudice, plaintiffs'

constitutional and other federal claims

and dismissed, without prejudice,

plaintiffs' pendent state claims.

On April 11, 1988, petitioners filed

a notice of appeal from the three orders of

the District Court. The caption of the

notice of appeal read as follows:

MINORITY EMPLOYEES OF THE

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF

EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

VS.

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF

EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et al.,

Defendants.

5

The body of the notice contained the

following recital:

Now come plaintiffs in the

above case and appeal to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit from the

orders of the Court entered on 28

April 1982 denying the

plaintiffs' motion for class

certification, 3 September 1986,

dismissing plaintiffs' claims

under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, and 11 March

1988, dismissing plaintiffs'

claims under 42 U.S.C. Sections

1981, 1983, and 1985 and the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth

Amendments to the Constitution of

the United States. The Order of

11 March finalized the Orders of

28 April 1982 and 3 September

1986. See. Appendix p. 58a-59a.

While the appeal was pending, this

Court, on June 24, 1988, decided Torres v.

Oakland Scavenger Co. . ___ U.S. ___, 108 S.

Ct. 2405, 101 L.Ed.2d 285 (1988).

Thereafter, defendant-appellees moved to

dismiss the individual petitioners Davis,

Oliver, and Perry from the appeal on the

ground that none of the individual

6

petitioners was designated by name in the

notice of appeal as required by the holding

in Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co,, supra.

On October 7, 1988, the Court of

Appeals dismissed the individual

petitioners from the appeal in an order

which recited that:

Rule 3(c), Fed. R. App. P.

provides that the notice of

appeal shall specify the party

or parties taking the appeal.

The use of the phrase "et al."

utterly fails to provide the

requisite notice. Failure to

individually name a party in

a notice of appeal constitutes

failure of that party to

appeal . . . (citations

omitted). The notice of

appeal filed in the present

case states that "plaintiffs

in the above case ... appeal

..." and lists only as

plaintiffs "Minority Employees

of the Tennessee Department of

Employment Security, et al."

Because plaintiffs Davis,

Oliver, and Perry are not

designated in the notice of

appeal as required by Torres,

It is Ordered that the

motion to dismiss is granted.

See. Appendix p.4a.

7

On October 21, 1988, petitioners

moved, pursuant to Rule 2, Fed. R. Civ. P.,

and 28 U.S.C. §§ 1653, and 2071, for leave

to amend the notice of appeal by typing the

names of the individual petitioners,

Rosetta Davis, Alma Oliver, and Hazel

Perry, on the notice of appeal, and to

suspend the requirements of Rule 3(c), Fed.

R. App. P., as well as filed an amended

notice of appeal.

The Clerk's office, responded by

letter stating that:

This letter is to advise you that

the order October 7, 1988 is not a

final order that disposes of this

appeal.

The intent of the order was to grant

the appellees' motion to dismiss

certain parties, only.

We are sorry for any confusion this

may have caused...

Thereafter, petitioners, on October

21, 1988, renewed the above motion and, on

8

October 26, 1988, requested rehearing en

banc.

By order dated February 28, 1989, the

Court of Appeals denied the motion to

suspend the requirements of Rule 3(c) and

to amend the notice of appeal.

Oral argument on the remainder of the

appeal by plaintiff Minority Employees of

the Tennessee Department of Employment

Security, Inc., was held in the Court of

Appeals on May 23, 1989.

The individual petitioners filed in

this Court a petition for a writ of

certiorari to the Court of Appeals.

Thereafter, the Court of Appeals voted to

rehear the appeal en banc. Petitioners

duly notified this Court of the rehearing

whereupon this Court issued an order

denying the pending petition for a writ of

certiorari.

9

By a vote of eight to six, the Court

of Appeals, on April 26, 1990, affirmed the

judgment of the district court.

Circuit judge Guy, in a concurring

opinion, wrote that:

"Although I believe the

dissent sets forth a more

reasonable approach to the

interpretation of Fed. R. App.

P. 3(c), I nonetheless join

the conclusion reached by the

majority in this case for two

reasons.* First, the majority

opinion provides clearer,

albeit more rigid guidance for

the bench and bar in the

future. The dissent allows-

even invites- the same type

of ad hoc determinations which

caused us to hold this en banc

hearing in the first place.

Appendix p. 63a.

♦There is really a third and

perhaps even more compelling

reason. Were I to join the

dissent, it would result in an

equally divided court and no

opinion would issue from the

en banc court. The district

court would be affirmed on the

substantive issue, and our

earlier panel decision would

be affirmed on the procedural

issue.

10

Judge Nelson delivered an opinion

concurring in part and dissenting in part

in which judges Merritt, C.J., Jones,

Norris, and Keith joined. Judge Martin

dissented in an opinion joined by judge

Jones.

The majority opinion purported to base

its decision upon Torres. supra. It

construed the opinion in Torres. supra. as

follows:

The Supreme Court in Torres

held that a notice of appeal

using the phrase 'et al.1

failed to designate an

appealing party and,

therefore, did not confer

jurisdiction over the party

whose name was not expressly

included in the notice. 108

S. Ct. at 2407___

It is evident to us that

Torres spoke to factual

circumstances concerning the

adequacy of a notice of appeal

which were broader than those

immediately before it. It has

to be concluded that faced

with a hard choice, the

Supreme Court decided that the

need at this stage of the

proceedings for precision and

11

for fidelity to the language

of the court rule overrode

traditional notions of equity.

A failure to fulfill the plain

command of the rule by failing

to name the party, therefore,

was fatal to the appellants'

rights to seek further relief.

Appendix pp. 18a.

The majority opinion stated that

"(a)lthough the 'some designation' or

'otherwise designated' language in Torres

appears to contemplate something less than

naming, 108 S.Ct. at 2409," Appendix, p.

33a, the court said it was "in accord with

the interpretation of Torres as requiring

naming," Appendix, p. 45a, except (1) where

the name of the purported appellant

otherwise appeared on "the face of the

document" such as in the caption, Appendix,

p. 49a, or (2) where, in class actions, the

"naming of the class representative (is)

sufficient to indicate that entire class

appealed." Appendix, p. 51a.

12

Finally, the majority opinion rejected

the possibility of an amendment to the

notice of appeal on the ground that Fed. R.

App. P. 26(b) prohibits a court from

enlarging the time for filing a notice of

appeal. Appendix, p. 54a.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

THE COURT OF APPEALS BELOW DECIDED AN

IMPORTANT QUESTION OF FEDERAL APPELLATE LAW

WHICH HAS NOT BEEN, BUT WHICH SHOULD BE,

SETTLED BY THIS COURT.

The April 26, 1990 opinion of the

Court of Appeals below decided a question

of law which will result in wide-spread

forfeiture of the right to appeal by

plaintiffs who have expressed, in their

notice of appeal, an unequivocal intent to

appeal and who have complied with the

stated requirements of this Court's

decision in Torres. supra. The opinion and

13

decision below threaten the validity of

countless pending and future appeals on an

important issue of law which has not been,

but which should be, settled by this Court.

The Court of Appeals held that its

ruling was required by the holding of this

Court in Torres, supra. It construed the

decision in that case as imposing a strict

rule, to be applied with possibly only two

exceptions, that a party's failure to be

named individually in a notice of appeal

constitutes failure of that party to

appeal.

Since the individual petitioners'

names were not individually listed either

in the notice of appeal or in the caption

of the notice of appeal, the majority of

the en banc Court of Appeals concluded that

Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co. . supra,

required dismissal of their appeal.

14

Whether the failure to list purported

appellants by names in a notice of appeal

constitutes a failure by those parties to

appeal, however, is an issue which this

Court neither addressed nor decided in

Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co., supra.

This Court granted certiorari in

Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co.. supra. to

determine "whether a federal appellate

court has jurisdiction over a party who was

not specified in the notice of appeal...."

Id. 101 L.Ed.2d at 289. This terminology,

"party who was not specified in the notice

of appeal," was similar to the phrase

"(t)he notice of appeal shall specify the

party or parties taking the appeal," used

in Rule 3(c).

The court of appeals, however,

believed that this Court's use of the term

"party who was not specified in the notice

of appeal" represented a stricter

15

interpretation of Rule 3(c) which required

the listing in the notice of appeal of the

individual name of any party purporting to

appeal.

It ignored suggestions to the contrary

in the opinion in Torres. supra, such as

the Court's explicit statement in Torres,

supra, that the plaintiff therein could not

be deemed to be specified in the notice of

appeal, as required by Rule 3(c), because

he "was never named or otherwise

designated, however, inartfully, in the

notice of appeal." Id. 101 L.Ed.2d at

292.

Clearly, this Court's use of the

phrase "otherwise designated," meant that

an appellant could be designated in a

notice of appeal without being specifically

listed by name. This Court was not

attempting in Torres. supra. to spell out,

in precise terms, the myriad ways in which

16

the identity of a party might be designated

in a notice of appeal other than by being

specifically named in the notice of appeal.

The court below closed the door to

this possibility by holding that a party's

failure to be listed by name in the notice

of appeal was fatal for the appeal except

for members of a class in a class action

and for parties whose names were

individually listed in the caption.

Nothing in the opinion in Torres. supra.

however, limits the designations in the

manner indicated by the court of appeals.

In Torres v Oakland Scavenger Co. .

supra, this Court only held that a notice

of appeal which included the names of 15

plaintiff-intervenors as appellants could

not sensibly also be construed as a notice

of appeal on behalf of a plaintiff-

intervenor, i.e. , Torres, whose name did

not appear at all in the notice of appeal.

17

The court of appeals has construed

Torres. supra. to have a more far-reaching

effect than ever contemplated by this

Court. For all intents and purposes, it

has interpreted Torres. supra. to require

the names of all appellants to be listed in

a notice of appeal, thus effectively

rewriting Rule 3(c) and undermining the

decision in Torres. supra.

The ruling below is thus a decision on

an important issue never before decided by

this Court. Because some courts of appeals

are reaching similar results, see. Samos-

Martinez v. Soto-Santiaqo. 863 F.2d 174

(1st Cir. 1988), and cases cited in the en

banc opinion below in Appendix pp. 2la-

223, 45a, while other courts are reaching

conflicting results, see. National Center

for Immigrants1 Rights, Inc, v. INS, 892

F.2d 814 (9th Cir. 1989), this Court should

grant the writ of certiorari.

18

The importance of the questions

presented and the need for a decision by

this Court are furthered evidenced by the

almost even split on the issues in the

court of appeals below.

II.

IN HOLDING THAT PARTIES MUST BE

INDIVIDUALLY NAMED IN A NOTICE OF

APPEAL AND THAT "ET AL." CAN NOT

BE USED TO ASSIST IN IDENTIFYING

PARTIES TAKING AN APPEAL, THE

DECISION OF THE COURT BELOW IS IN

CONFLICT WITH THIS COURT'S

DECISION IN TORRES.

This Court's decision in Torres.

supra. conflicts in important ways with the

decision below.

First, this Court held in Torres.

supra. that a party could satisfy Rule

3(c)'s requirement by "fil(ing) the

functional equivalent of a notice of

appeal". Id., 101 L.Ed.2d at 292. Second,

the Court held that a party filed "the

19

functional equivalent of a notice of

appeal” if the party was "named or

otherwise designated, however, inartfully,

in the notice of appeal." Id.

Third, the Court held that the

specificity requirements of Rule 3(c) were

met if the notice of appeal contained "some

designation that gives fair notice of the

specific individual or entity seeking to

appeal". Id. The decision of the court of

appeals below was m conflict with each of

the Court's three holdings in Torres,

supra.

The court of appeals rejected this

Court's test of functionality altogether.

No inquiry was undertaken by the court of

appeals to ascertain whether the

petitioners here had, in fact, filed the

functional equivalent of a notice of

appeal, and, in fact, the court of appeals

rejected such an inquiry.

20

The court of appeals further gave

short shrift to this Court's ruling that

the notice of appeal should be examined to

see if the party attempting to appeal was

"named or otherwise designated, however

inartfully, in the notice of appeal filed."

The court made no such examination other

than to determine if the individual

petitioners were named in either the body

or the caption of the notice of appeal.

Instead of making the searching

inquiry required by this Court's decision

in Torres, supra. the court of appeals

adopted a harsh, inflexible rule to decide

the issue. It held that the individual

petitioners had to be individually named in

the notice of appeal for the appeal with

respect to them to be good.

Since they were not so named, or, in

what the court of appeals took to be the

same thing, were not individually listed by

21

names in the notice of appeal, the court of

appeals held that the requirements of Rule

3(c) were not met.

Furthermore, the court of appeals

failed to follow, or even mention, the

holding of this Court in Torres, supra.

that a party can satisfy the "specificity

requirements of Rule 3(c)" by providing in

the notice of appeal a "designation that

gives fair notice of the specific

individual or entity seeking to appeal."

Id. 101 L.Ed.2d at 292.

The court of appeals rejected any such

inquiry of this sort.

Rather, the court adopted the rule

that it had no jurisdiction over a notice

of appeal on behalf of a party who was not

individually named in the notice of appeal.

As a result, this Court's statement in

Torres, supra. that the "specificity

requirement of Rule 3(c) can be met by a

22

"designation that gives fair notice of the

specific individual or entity seeking to

appeal," was rendered meaningless.

Overall, the court of appeals' ruling

amounts to a repudiation of this Court's

admonition that courts of appeals, in

resolving issues of compliance under Rule

3(c), should determine whether "in light of

all the circumstances, the rule had been

complied with". Torres. supra. 101 L.Ed.2d

at 291, citing Foman v. Davis, 371 U.S.

178, 181 (1962). See. Houston v. Lack. ___

U.S. ___ , 108 S. Ct. ___ , 101 L.Ed. 2d 245

(1988) .

Thus, the court of appeals' ruling was

a refusal to determine if the individual

petitioners herein had, in fact, filed the

functional equivalent of a notice of

appeal, a refusal to determine if the

individual petitioners had been "otherwise

designated" in the notice of appeal through

23

use of the term "plaintiffs in the above

case", and a refusal to determine if the

designation "plaintiffs in the above case"

gave fair notice of the specific

individuals or entities seeking to appeal.

III.

THE COURT OF APPEALS SO FAR

DEPARTED FROM THE ACCEPTED AND

USUAL COURSE OF JUDICIAL INTER

PRETATION OR RULES AS TO REQUIRE

THIS COURT'S SUPERVISION

Despite the statement in the notice of

appeal that plainly says "Now come

plaintiffs in the above case and appeal,"

the court of appeals held that only one

plaintiff, namely, the Minority Employees

of the Tennessee Department of Employment

Security, Inc., had effectively appealed.

It reached this odd conclusion despite the

fact that the term "plaintiffs" occurring

in the body of the notice of appeal was

plural, and did not specifically mention

24

the Minority Employees of the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security, Inc.

It was sufficient, the court of

appeals held, that the name of the Minority

Employees appellant was listed in the

caption of the notice of appeal. The Court

of Appeals believed that this Court's

opinion in Torres. supra, required it to

disregard the use of "et al." in the

caption, thereby leaving the Minority

Employees appellant as the sole party

individually named in the notice of appeal

even though it was not mentioned in the

body of the notice of appeal, and the term

which was used, i.e., "plaintiffs in the

above case" was plural.

This tortuous interpretation of the

notice of appeal was thought to be required

by Torres. supra.

Such a construction of the notice of

appeal is so far a departure from the

25

accepted and usual way of interpreting

legal documents that this Court should

exercise its power of supervision by

granting the writ of certiorari.

In interpreting the notice of appeal,

the Court of Appeals should have heeded the

admonition of Justice Holmes in Roschen v.

Ward. 279 U.S. 722 (1929), concerning the

strict construction rule. Justice Holmes

said: "We agree to all the generalities

about not supplying criminal laws with what

they omit, but there is no canon against

using common sense in construing laws as

saying what they obviously mean." Id. at

728.

26

IV

THE COURT OF APPEALS DECIDED AN

IMPORTANT QUESTION OF FEDERAL LAW

IN HOLDING THAT THE DEFECT IN THE

NOTICE OF APPEAL COULD NOT BE

CURED PURSUANT TO AN AMENDMENT

UNDER 28 U.S.C.§ 1653 OR A

SUSPENSION OF RULE 3(C) UNDER

RULE 2, FED. R. APP. P.

The court of appeals held that because

the time requirement of Rule 3(c) was

jurisdictional, it lacked authority to

amend a notice of appeal. Petitioners

submit that such authority exists under 28

U.S.C. §1653, to cure defective allegations

of the designations of purported appellants

after the time for taking an appeal has

expired.

Whether a notice of appeal can be

amended in this way, is an important issue

of federal law which has not been, but

should be, settled by this Court.

In its decision in Torres, supra, this

Court did not address the applicability of

27

28 U.S.C. § 1653. But 28 U.S.C. § 1653 is

a Congressional statute which specifically

provides that "Defective allegations of

jurisdiction may be amended, upon terms, in

the trial or appellate courts."

A defective allegation in a notice of

appeal, such as a failure to name

individually all plaintiffs appealing or to

refer only to "plaintiffs in the above

case", can be cured under 28 U.S.C. § 1653

by simply amending the notice of appeal to

supply the missing allegation.

Such an amendment should be effective

for all purported appellants, at least

where the amendment satisfies a reguirement

analogous to the requirement under Rule

15(c), Fed. R. Civ. P., for relating back

to the time of the original filing, i.e.,

the respondent in the appeal has received

such notice of an appeal that he or she

will not be prejudiced in defending on the

28

merits, and knew, or should have known,

that, but for a mistake concerning the

identify of the proper party, the appeal

would have included the purported

appellant.

This important issue should be settled

by this Court. This Court can additionally

consider whether Rule 2 can appropriately

be used in conjunction with 28 U.S.C. §

1653 to effectuate proper amendments to

notices of appeal under Rule 3(c).

29

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, this court

should grant a writ of certiorari to review

the judgments below.

Respectfully submitted,

RICHARD H. DINKINS

RUSSELL T. PERKINS

WILLIAMS & DINKINS

203 Second Ave. N.

Nashville, TN

37201

(615) 244-3988

JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

NAPOLEON B.WILLIAMS,JR*

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

♦Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

July 25, 1990

30

APPENDIX

la

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-5429

Minority Employees of the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security,

Incorporated; c/o Leon Wilson,

President,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

Rosetta N. Davis;

Alma C. Oliver;

Hazel Perry, M.S.

Plaintiffs,

v.

State of Tennessee, Department of

Employment Security; Robert J. Bible,

Commissioner of the State of Tennessee,

Department of Employment Security; State of

Tennessee, Department of Personnel; William

C. Koch, Jr., Commissioner of the State of

Tennessee Department of Personnel,

Defendants-Appellees.

FILED

FEB 28 1989

LEONARD GREEN, Clerk

2 a

ORDER

Before: MARTIN and RYAN, Circuit Judges;

and POTTER, District Judge.*

Appeal is taken from dismissal of this

civil rights action. By order of October

7, 1988, this court dismissed as appellants

the individual plaintiffs Davis, Oliver and

Perry. Plaintiff now moves 1) to suspend

the requirements of Rule 3(c), Fed. R. App.

P. , and 2) to amend the notice of appeal.

Defendants oppose both motions.

The requirement of Rule 3(c), Fed. R.

App. P. , that a notice of appeal shall

specify the party or parties taking the

appeal is jurisdictional in nature. Torres

v. Oakland Scavenger Co. . 108 S.Ct. 2405

(1988). Jurisdictional requirements may

not be waived. Id. at 2409; see also

The Honorable John W. Potter,

U.S. District Judge for the Northern

District of Ohio, sitting by designation.

3 a

Hinsdale v. Farmers Nat'l Bank & Trust Co..

823 F.2d 993 (6th Cir. 1987).

Further, we have no authority to amend

a notice of appeal to add additional

parties after the time for taking the

appeal has expired. Rule 26(b), Fed. R.

Civ. P.; see also Trinidad Coro, v. Marv.

781 F.2d 136 (9th Cir. 1986) (per curiam);

Cook and Sons Equipment. Inc, v. Killen.

277 F.2d 607 (9th Cir. 1960).

It is ORDERED that plaintiff's motion

to suspend the requirements of Rule 3(c),

Fed. R. Civ. P. , and motion to amend the

notice of appeal are denied.

ENTERED BY ORDER OF THE COURT

/s/ Leonard Green____________

Clerk

4 a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

No. 88-5429

Minority Employees of the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security,

Incorporated; et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellants,

Hazel Perry, MS.

Plaintiff,

vs.

State of Tennessee, Department of

Employment Security; et al.

Defendants-Appellees.

FILED

OCT 7 1988

LEONARD GREEN, Clerk

ORDER

Before: KENNEDY and KRUPANSKY, Circuit

Judges; and EDWARDS, Senior Circuit Judge.

This appeal is taken from the

dismissal of this civil rights action. The

defendants now move to dismiss plaintiffs

5 a

Davis, Oliver and Perry from this appeal

pursuant to Torres v. Oakland Scavenger

Co., __ U.S. __ , 108 S.Ct. 2405 (June 24,

1988), on grounds that those plaintiffs

were not designated in the notice of

appeal. The plaintiffs oppose the motion

to dismiss.

Rule 3(c), Fed. R. App. P. , provides

that the notice of appeal shall specify the

party or parties taking the appeal. The

use of the phrase "et al" utterly fails to

provide the requisite notice. Failure to

individually name a party in a notice of

appeal constitutes failure of that party to

appeal. Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co..

__ U.S. ___ , 108 S.Ct. at 2 4 09; see also

Van Hoose v. Eidson. 450 U.S. 746 (6th Cir.

1971) (per curiam order) . The notice of

appeal filed in the present case states

that "plaintiffs in the above case . . .

appeal...." and lists only as plaintiffs

6 a

"Minority Employees of the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security, et al."

Because plaintiffs Davis, Oliver and Perry

are not designated in the notice of appeal

as required by Torres.

It is ORDERED that the motion to

dismiss is granted.

ENTERED BY ORDER OF THE COURT

/s/ Leonard Green____________

Clerk

7 a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

NASHVILLE DIVISION

No. 81-3114

Judge Higgins

MINORITY EMPLOYEES OF THE TENNESSEE

DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

INC., et al.

v.

STATE OF TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF

EMPLOYMENT SECURITY, et al.

ORDER

In accordance with the memorandum

contemporaneously filed, the objections

(filed February 14, 1986) of the plaintiffs

to the Magistrate's Report and

Recommendation (filed January 31, 1986) are

overruled. The objections (filed March 6,

1986) of the defendants to the Magistrate's

finding of disparate treatment as to the

plaintiff Davis and disparate impact as to

the plaintiffs Davis and Oliver are

8 a

sustained. The plaintiffs' claims under

Title VII are hereby dismissed.

It is so ORDERED.

/s/ Thomas A. Higgins______

Thomas A. Higgins

United States District Judge

9-3-86

9 a

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF TENNESSEE

NASHVILLE DIVISION

No. 81-3114

Judge Higgins

MINORITY EMPLOYEES OF THE TENNESSEE

DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

et al.

v.

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECU

RITY, et al.

ORDER

Before the Court are the objections of

the plaintiffs1 to the Magistrate's Report

and Recommendation filed January 20, 1988.

1 The objecting plaintiffs are

Rosetta Davis, Alma Oliver, Hazel Perry and

Minority Employees of the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security, Inc.

The objections were filed timely on

February 22, 1988, pursuant to an extension

of time granted by order entered February

11, 1988.

1 0 a

The Magistrate recommended that the

defendants'2 joint motion for summary

judgment (filed December 24, 1986) be

granted.

In their first objection, the

plaintiffs do not assail the Magistrate's

application of the doctrines of res

judicata and collateral estoppel to the

facts at issue. Rather, the plaintiffs

challenge the correctness of the underlying

judgments. The Court finds this objection

to be without merit, since it attempts to

attack matters previously considered and

decided.

Secondly, the plaintiff, Hazel Perry,

objects to the Magistrate's recommendation

The defendants are the Tennessee

Department of Employment Security; its

former Commissioner, Robert J. Bible, in

his official and individual capacities; the

Tennessee Department of Personnel; and its

former Commissioner, William C. Koch, in

his official and individual capacities.

11a

as to the disposition of her claims on the

ground that she has been deprived of "an

opportunity to be heard in this Court on

her claims." The Court finds this

objection to be without merit, since the

plaintiff Perry failed to present any

evidentiary material in response to the

defendants' properly supported motion for

summary judgment on the issue of an alleged

discriminatory delay in rehiring her.

After considering the Report and

Recommendation, the objections and related

pleadings, the Court finds that the

findings and conclusions of the Magistrate

are correct. The Report and Recommendation

is adopted and approved.

The defendants' joint motion for

summary judgment is granted. The

plaintiffs' claims under 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981,

1983 and 1985, and the Thirteenth and

Fourteen Amendments are dismissed with

1 2 a

prejudice. The plaintiffs' pendent state

law claims are dismissed without prejudice.

Accordingly, this action is dismissed

in its entirety, and the Clerk is directed

to enter judgment accordingly.

It is so ORDERED.

/s/ Thomas A. Higgins

Thomas A. Higgins

United States District Judge

3-9-88

1 3 a

No. 88-5429

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

MINORITY EMPLOYEES OF THE

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF

EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

INCORPORATED,

Plaintiff-Appellant,

ROSETTA N. DAVIS, ALMA C.

OLIVER, HAZEL PERRY,

Plaintiffs,

v. ) ON PETITION

) for Rehear-

STATE OF TENNESSEE, DEPARTMENT )ing En Banc

OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY; ROBERT )

J. BIBLE, COMMISSIONER OF THE )

STATE OF TENNESSEE, DEPARTMENT )

OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY; STATE )

OF TENNESSEE, DEPARTMENT )

OF PERSONNEL; WILLIAM C. KOCH, )

JR., COMMISSIONER OF THE STATE )

OF TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF

PERSONNEL,

)

)

)

Defendants-Appellees. )

Decided and Filed April 26, 1990

Before: MERRITT, Chief Judge; KEITH,

KENNEDY, MARTIN, JONES, KRUPANSKY,

WELLFORD, MILBURN, GUY, NELSON, RYAN,

BOGGS, NORRIS, Circuit Judges; and ENGEL,

Senior Circuit Judge.

1 4 a

ENGEL, S.J., delivered the opinion of

the court in which KENNEDY, KRUPANSKY,

WELLFORD, MILBURN, RYAN and BOGGS, JJ. ,

joined. GUY, J. , (pp. 25-26) delivered a

separate concurring opinion. NELSON, J.,

(pp. 27-43) delivered a separate opinion

concurring in part and dissenting in part,

in which MERRITT, C.J., KEITH, JONES and

NORRIS, JJ., joined. MARTIN, J., (pp. 44-

50) delivered a separate dissenting opinion

in which JONES, J., joined.

ENGEL, Senior Circuit Judge. Our

court voted for rehearing en banc in this

appeal in an effort to resolve the

uncertainties which have arisen within our

circuit in the interpretation of Fed. R.

App. P. 3(c) following the decision of the

United States Supreme Court in Torres v.

Oakland Scavenger Co. . 487 U.S. ___ , 108

S.Ct. 2405 (1988). As with most decisions

1 5 a

interpreting procedural rules, our most

important task, after fidelity to any

Supreme Court decisions bearing upon the

question, is to provide an understandable

and practical guide to the application of

the federal rules so that litigants do not

innocently frustrate their access to our

courts. In certain areas of the law, it is

altogether evident that the Supreme Court

has demanded clarity and strict adherence

to promulgated rules, even though notions

of equity in a given case may argue to the

contrary. See. e.q., Schiavone v. Fortune.

477 U.S. 21, 29-31 (1985) (strictly

construing Fed. R. Civ. P. 15(c) to bar a

suit by a plaintiff who served the

defendant with a correctly captioned

complaint only after the statute of

limitations had run); Griggs v. Provident

Consumer Discount Co.. 459 U.S. 56, 60-61

(1982) (per curiam) (strictly construing

1 6 a

Fed. R. App. P. 4(A)(4) to bar a premature

notice of appeal, even where there is no

prejudice to the responding party); Browder

v. Director. 111. Dept, of Corrections, 434

U.S. 257, 264 (1978) (unanimous opinion

holding that even though the defendant's

untimely motion for rehearing and

reconsideration was considered by the

district court, the motion did not toll the

"mandatory and jurisdictional" time limit

for filing a notice of appeal under Fed. R.

App. P. 4(a)). Rather plainly, certain

rules are deemed sufficiently critical in

avoiding inconsistency, vagueness and an

unnecessary multiplication of litigation to

warrant strict obedience even though

application of the rules may have harsh

results in certain circumstances. Under

Torres. Rule 3(c) is such a rule.

The Supreme Court in Torres held that

a notice of appeal using the phrase "et

1 7 a

al." failed to designate an appealing party

and, therefore, did not confer jurisdiction

over the party whose name was not expressly

included in the notice. 108 S.Ct. at 2407.

The jurisdictional principle adopted by

Torres should have come as no legal

surprise in our circuit. Faced with a

conflict within the circuits in Torres. the

Supreme Court chose the construction of

Rule 3(c) adopted by the Sixth Circuit in

Life Time Doors. Inc, v. Walled Lake Door

Co. . 505 F. 2d 1165 (6th Cir. 1974), which

held that the failure to name was a

jurisdictional bar. Torres. 108 S.Ct. at

2407 n.l (citing Life Time Doors) .

Remarkably, even before Life Time Doors, a

panel of our court had been faced with a

notice containing the phrase "et al." and

concluded, as in Torres, that the phrase

failed to inform other parties or any court

as to which parties intended to appeal.

1 8 a

Van Hoose v. Edison. 450 F.2d 746 (6th Cir.

1971).

It is evident to us that Torres spoke

to factual circumstances concerning the

adequacy of a notice of appeal which were

broader than those immediately before it.

It has to be concluded that faced with a

hard choice, the Supreme Court decided that

the need at this stage of the proceedings

for precision and for fidelity to the

language of the court rule overrode

traditional notions of equity. A failure

to fulfill the plain command of the rule by

failing to name the party, therefore, was

fatal to the appellants' rights to seek

further relief. The conclusion that no

appeal was intended by the parties whose

name was so omitted could not be cured by

subsequent allegations of subjective

intent. That the failure to name the party

indisputably was the result of clerical

1 9 a

error in Torres did not deter the Supreme

Court from concluding that the rule was not

satisfied.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, our

circuit, not unlike others faced with

similar hard choices, appears to have

sought to soften the blow of such an

arbitrary rule as it developed in the

context of specific appeals. Despite the

broader language in Torres. in Ford v.

Nicks. 866 F. 2d 865 (6th Cir. 1989), a

panel of our court endeavored to draw a

rather fine line and accepted jurisdiction

over unnamed parties based upon the

etymology of the phrase 11 et al." and the

use of the word "the" in the body of the

notice of appeal. Accordingly, faced with

a number of decisions in our court which

turn upon a resolution of the conflict that

seems to exist between Ford v. Nicks and

2 0 a

Torres. we voted to grant a rehearing en

banc.

I.

Our immediate appeal involves a notice

of appeal using the term "et al." to

designate appealing parties. A motions

panel of this court, in an unpublished

order, concluded that the notice of appeal

designated as an "appellant" only the named

corporate plaintiff, Minority Employees of

the Tennessee Department of Employment

Security, Inc. (Minority Employees) .

(Order of October 7, 1988). The panel

determined that jurisdiction was lacking

over the purported appeals of the

individual plaintiffs because that notice

failed to name them. A second motions

panel, in an unpublished order, denied

plaintiffs' motion to amend the notice of

appeal and to suspend the requirements of

Rule 3(c). (Order of February 3, 1989).

2 1 a

A third panel of this court upheld the

dismissal of the individual plaintiffs and

affirmed the district court's dismissal of

Minority Employees, the only appellant.

Minority Employees v. State of Tennessee.

No. 88-5429 (Decided July 10, 1989)

(unpublished per curiam).

We noted that the panel decisions

dismissing the individual plaintiffs and

our opinion in Van Hoose v. Eidson. 450

F.2d 746 (6th Cir. 1971), appeared to

conflict with our opinion in Ford v. Nicks.

866 F.2d 865 (6th Cir. 1989). In light of

the holding and spirit of the Supreme

Court's opinion in Torres v. Oakland

Scavenger Co. . 487 U.S. __ , 108 S.Ct. 2405

(1988), we affirm the decisions of the

panels in all respects. In affirming the

dismissal of the individual plaintiffs, we

rule that Van Hoose v. Eidson. supra,

remains good law in this circuit and that

2 2 a

Ford v. Nicks, supra. on this particular

question, is expressly rejected as the law

of this circuit. We hold that the term "et

al•11 is insufficient to designate appealing

parties in a notice of appeal and that

appellants must include in the notice of

appeal the name of each and every party

taking the appeal. The dismissal of

Minority Employees' appeal on the merits is

unanimously affirmed.

II.

On March 6, 1981, corporate plaintiff

Minority Employees and individual

plaintiffs Rosetta Davis, Alma Oliver and

Hazel Perry filed this action for alleged

violations of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e

et seq., and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985,

and 1988. Plaintiffs named as defendants

the State of Tennessee Department of

Employment Security (TDES) and Department

2 3 a

of Personnel. Plaintiffs also named the

commissioners of these respective

departments, Robert J. Bible and William C.

Koch, Jr., in their individual and official

capacities. On March 11, 1988, the United

States District Court for the Middle

District of Tennessee, Nashville Division,

granted the defendants' joint motion for

summary judgment and dismissed plaintiffs'

action in its entirety.

On April 11, 1988, a notice of appeal

was filed in this case.1 The relevant

portion of the notice is entitled:

The notice of appeal has been

appended to this opinion as "Attachment 1."

2 4 a

MINORITY EMPLOYEES OF THE TENNESSEE

DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT SECURITY,

et al.

Plaintiffs

VS.

TENNESSEE DEPARTMENT OF EMPLOYMENT

SECURITY, et al.

Defendants

The body of the notice provides:

NOTICE OF APPEAL

Now come plaintiffs in the above

case and appeal to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

from the orders of the Court entered

on 28 April 1982 denying the

plaintiffs' motion for class

certification, 3 September 1986,

dismissing plaintiffs' claims under

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, and 11 March 1988, dismissing

plaintiffs' claims under 42 U.S.C.

Sections 1981, 1983 and 1985 and the

Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments

to the Constitution of the United

States. The Order of 11 March 1988

finalized the Orders of 28 April 1982

and 3 September 1986.

[Signature]

In their initial brief in this court,

plaintiffs purported to raise three issues

2 5 a

on appeal: (1) whether the district court

erred in refusing to extend the time in

which to apply for class certification; (2)

whether the district court erred in

dismissing plaintiffs' Title VII claims;

and (3) whether the district court erred in

granting defendants' motion for summary

judgment.

On defendants' motion, a panel of this

court, on October 7, 1988, dismissed the

individual plaintiffs from the appeal. The

panel stated:

Rule 3(c), Fed. R. App. P.,

provides that the notice of

appeal shall specify the party or

parties taking the appeal. The

use of the phrase 11 et al" [sic]

utterly fails to provide the

requisite notice. Failure to

individually name a party in a

notice of appeal constitutes

failure of that party to appeal.

Torres v. Oakland Scavenger Co..

__ U.S. ___ , 108 S.Ct. at 2409;

see also Van Hoose v. Eidson. 450

F. 2d 746 (6th Cir. 1971) (per

curiam order). The notice of

appeal filed in the present case

states that "plaintiffs in the

2 6 a

above case ... appeal . . . . " and

lists only as plaintiffs

"Minority Employees of the

Tennessee Department of

Employment Security, et al."

The panel, therefore, dismissed the

individual plaintiffs Davis, Oliver and

Perry because they were not designated in

the notice of appeal as required by Torres.

Plaintiffs subsequently moved to

suspend the requirements of Fed. R. App. P.

3(c) and to amend the notice of appeal. On

February 28, 1989, a second panel of this

court denied plaintiffs7 motion. Citing

Torres. the panel held that the court could

not "suspend" the requirement of Rule 3(c)

since the requirement was jurisdictional

and could not be waived. The panel, citing

Fed. R. App. P. 26(b), also concluded that

"we have no authority to amend a notice of

appeal to add additional parties after the

time for taking the appeal has expired."

On July 10, 1989, a third panel of

2 7 a

this court upheld the dismissal of the

individual plaintiffs and affirmed the

district court's dismissal of Minority

Employees, the sole appellant. Rehearing

en banc was granted on September 13, 1989.

In their supplemental brief on

rehearing, plaintiffs raise three ultimate

issues: (1) whether the decision to dismiss

the individual plaintiffs was error; (2)

whether the decision to refuse to allow the

amendment to the notice of appeal was

error; and (3) whether the district court's

disposition of the merits of the claims of

the individual and corporate plaintiffs was

error. The prior panels did not err in

their disposition of the first two issues.

We therefore do not address the merits of

the claims of the individual plaintiffs

because jurisdiction over them is lacking.

2 8 a

III.

Without further clarification by the

Supreme Court beyond its language in

Torres, we are left quite specifically with

the question of what a party must do to

"specify the party or parties taking the

appeal." Federal Rule of Appellate

Procedure 3(c) provides:

(c) Content of the Notice of Appeal.

The notice of appeal shall

specify the party or parties

taking the appeal; shall

designate the judgment, order or

part thereof appealed from; and

shall name the court to which the

appeal is taken. Form 1 in the

Appendix of Forms is a suggested

form of a notice of appeal. An

appeal shall not be dismissed for

informality of form or title of

the notice of appeal.

As with interpretations of every technical

rule, interpreting this rule to provide

sufficient certainty inevitably leads to

harsh results in some cases. As Justice

Scalia stated in his concurrence in Torres,

29a

"[b]y definition all rules of procedure are

technicalities; sanction for failure to

comply with them always prevents the court

from deciding where justice lies in the

particular case, on the theory that

securing a fair and orderly process enables

more justice to be done in the totality of

cases." 108 S.Ct. at 2410 (Scalia, J. ,

concurring). In the interest of creating

certainty in this area, educating potential

appellants as to the requirement and

fostering consistency within our circuit,

this circuit must state as clearly as

possible what constitutes a notice that

complies with the rule.

The Supreme Court recently held in

Torres that a failure to comply with Rule

3(c)'s requirement of specifying the party

or parties taking the appeal is a

jurisdictional bar, stating that "[t]he

failure to name a party in a notice of

30a

appeal is more than excusable

'informality;' it constitutes a failure of

that party to appeal." 108 S.Ct. at 2407.

Justice Marshall recognized that the

"purpose of the specificity requirement of

Rule 3(c) is to provide notice both to the

opposition and to the court of the identity

of the appellant or appellants." Torres,

108 S.Ct. at 2409. Torres unequivocally

held that the term "et al." fails to

fulfill this purpose and is not sufficient

to comply with the specificity requirement

of Rule 3(c). 108 S.Ct. at 2409.

In Torres, Jose Torres was one of

sixteen plaintiffs who intervened in an

employment discrimination suit against

Oakland Scavenger Company. Although the

district court dismissed the complaint for

failure to state a claim warranting relief,

the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

reversed. On remand, Oakland moved for

31a

partial summary judgment against Torres,

arguing that the prior district court's

judgment must stand since Torres failed to

effectuate an appeal. 108 S.Ct. at 2407.

The notice of appeal at issue in

Torres was captioned, in relevant part,

"JOAQUIN MORELES BONILLA, et al.,

Plaintiffs in Intervention,..." The body

of the notice, however, listed fifteen of

the sixteen intervening plaintiffs,

omitting Torres' name.2 The Supreme Court

noted that it was "undisputed that the

omission in the notice of appeal was due to

a clerical error on the part of a secretary

employed by petitioner's attorney." 108

S.Ct. at 2407. The Court, however, rejected

Torres argument that the use of the phrase

"et al." was sufficient to designate:

The notice of appeal in Torres

has been appended to this opinion as

"Attachment 2."

32a

The purpose of the specificity

requirement of Rule 3 (c) is to

provide notice both to the

opposition and to the court of

the identity of the appellant or

appellants. The use of the

phrase "et al.," which literally

means "and others," utterly fails

to provide such notice to either

intended recipient. Permitting

such vague designation would

leave the appellee and the court

unable to determine with

certitude whether a losing party

not named in the notice of appeal

should be bound by an adverse

judgment or held liable for costs

or sanctions. The specificity

requirement of Rule 3(c) is met

only by some designation that

gives fair notice of the specific

individual or entity seeking to

appeal. r Torres. 108 S.Ct. at

2409] .

The use of the phrase "et al." in the

present notice of appeal, which was

specifically rejected in Torres. is

contrary to the language and spirit of

Torres and precludes a conferment of

jurisdiction over the appeal of the

individual plaintiffs. Further, the use of

the term "plaintiffs" in the body of the

33a

notice failed to designate the individual

plaintiffs in light of the failure

specifically to name them.

Plaintiffs' counsel essentially argues

that the notice should be given a common-

sense reading, arguing that respondents

were not misled or prejudiced by the notice

of appeal. Although the "some designation"

or "otherwise designated" language in

Torres appears to contemplate something

less than naming, 108 S.Ct. at 2409, we do

not read Torres to permit the type of

inquiry suggested. See 108 S.Ct. at 2409

n.3. Such an approach was rejected by

Torres. fails to provide fair notice to the

intended recipients, and has the potential

for promoting indefensible semantic

distinctions.

In Ford v. Nicks, supra, for example,

a panel of this court distinguished Torres

and accepted a notice containing "et al."

34a

The court was persuaded that the use of the

definite article in "the defendants" in the

body of the notice of appeal sufficiently

designated the appealing parties, even

though the notice of appeal was captioned,

in relevant part, "Chancellor Roy S. Nicks,

et al. Defendants." 866 F.2d at 869. The

court reasoned that the lack of articles in

the Latin language indicates that "et al."

may mean either "and others" or "and the

others," depending upon the context. The

court concluded that the definite article

in the body clarified ambiguities inherent

in the caption and that the notice gave

fair notice that all eighteen defendants

appealed. In doing so, the Ford court

distinguished Torres:

The Torres Court translated the

phrase "et al." as meaning "and

others," rather than "and the

others." In the context of the

particular notice that was before

the Court in Torres. this

translation was impeccable. The

35a

best translation of the caption

in the case at bar, however,

would be "Chancellor Roy S. Nicks

and the others, Defendants,"

because the context shows that

"et al.11 was intended to refer to

all the others.

Ford, however, is inconsistent with Torres.

A court may not look to the intent of the

parties to cure the ambiguities inherent in

the use of the phrase "et al.11 The inquiry

would not serve Rule 3(c) 's purpose of

effectuating notice to the intended

recipients, the court and the responding

parties. Further, Torres indicates that a

court may not undertake an inquiry as to

whether the responding party was misled or

prejudiced by the omission to cure a

failure to "clear a jurisdictional hurdle."

See 108 S.Ct. at 2409 n.3.

Not only does the Ford inquiry

conflict with Torres. but it is at variance

with our opinion in Van Hoose v. Eidson.

supra. In Van Hoose. the court considered

3 6a

a notice of appeal partially captioned

"Floyd Van Hoose, et al. [sic] Plaintiffs-

Appellants." The court held that Van Hoose

was the only appellant, stating: "The only

party specified in the notice of appeal

filed in this case was Floyd Van Hoose.

The term 'et al' does not inform any other

party or any court as to which of the

plaintiffs desire to appeal in this case."

450 F.2d at 747. Although one could argue

that the Ford opinion is consistent with

Van Hoose. since the notice of appeal in

the latter case did not contain the

definite article, the attempt to

distinguish would be disingenuous and ill-

advised. Even if we thought that this

approach was consistent with Torres. we

cannot permit our jurisdiction to turn on

the presence or absence of the definite

article.

Our reading of Torres is informed by

37a

a scrutiny of the conflict in the circuits

identified by the Supreme Court. The

Supreme Court in Torres began its analysis

by indicating that the Court

granted certiorari to resolve a

conflict in the Circuits over

whether a failure to file a

notice of appeal in accordance

with the specificity requirement

of Federal Rule of Appellate

Procedure 3(c) presents a

jurisdictional bar to the

appeal.1

Torres. 108 S.Ct. at 2407 & n.l. A review

of the cases cited by the Supreme Court

reveals that the conflict between the *

Compare Farley Transportation Co.

v. Santa Fe Trail Transportation Co.. 778

F. 2d 1365, 1368-1370 (CA9 1985) (failure to

specify party to appeal is jurisdictional

bar); Covington v. Allsbrook. 636 F.2d 63,

64 (CA4 1980) (same); Life Time Doors. Inc,

v. Walled Lake Door Co.. 505 F.2d 1165,

1168 (CA6 1974) (same); with Ayres v.

Sears. Roebuck & Co..789 F.2d 1173, 1177

(CA5 1986) (appeal by party not named in

notice of appeal is permitted in limited

instances); Harrison v. United States. 715

F.2d 1311, 1312-1313 (CA8 1983) (same);

Williams v. Frev. 551 F.2d 932, 934, n.l

(CA3 1977) (same).

38a

circuits at that time was whether or not

something less than naming would be

acceptable. The courts that held that the

requirement was jurisdictional required

naming, whereas those courts that did not

were willing to permit something less than

naming.

Our opinion in Life Time Doors, 505

F. 2d at 1168, cited by the Supreme Court,

specifically required that parties be named

to confer jurisdiction. As we stated in

Life Time Doors, since the party "was not

named in the notice of appeal, he simply

did not appeal and we have no jurisdiction

over him." 505 F.2d at 1168. The other

two cases cited by the Supreme Court also

support this conclusion. The Ninth Circuit

in Farley. 788 F.2d at 1369, partially

relying upon our opinion in Van Hoose,

supra, also held that the parties must be

named to confer jurisdiction. As the

39a

Farley court noted, a "literal

interpretation of rule 3(c) creates a

bright-line distinction and avoids the need

to determine which parties are actually

before the court long after the notice of

appeal has been filed." 778 F.2d at 1369.

Similarly, the Fourth Circuit in Covington,

supra. extended our decision in Van Hoose,

supra, to require "actual signing by pro se

parties desiring to join in an appeal" as

the only "practical way" of specifying the

party or parties taking the appeal.

Covington, 636 F.2d at 64. This latter

case perhaps partially explains the "some

designation" language in Torres.

The three contrary cases cited by the

Supreme Court, however, permitted appeals

where the parties were not named. In all

three cases the courts determined that the

responding parties were not prejudiced or

misled. See Ayres, 789 F.2d at 1177 ("et

40a

al.11 in notice sufficient to designate

appealing parties where the "record

reflects that throughout the course of the

litigation, all parties utilized this oft-

used legal abbreviation when referring to

the plaintiffs") ; Harrison, 715 F. 2d at

1312-13 (notice of appeal amended to

include mistakenly omitted name where

responding party did not rely on omission);

Williams, 551 F.2d at 934 n.l (notice of

appeal effective as to two unnamed

individuals where responding parties

suffered no prejudice).

The Fifth Circuit's opinion in Ayres,

supra, highlights the divergence between

the circuits prior to Torres:

Three of our sister circuits

require strict compliance with

[Rule 3(c)], rejecting an

embracive designation such as "et

al." [cites to Farley. Life Time

Doors. and Covington omitted]. .

. . We have joined other

circuits in a less strict

application of the rule,

41a

permitting, in limited instances,

appeals by parties not named in

the notice of appeal. [cites to

Harrison. Williams, and others

omitted]. . . . Those circuits

giving a broader application to

Rule 3(c) have done so when

satisfied that there was no

surprise, detrimental reliance,

or prejudice to appellees because

one or more parties had not been

listed by name in the notice of

appeal. Typically, the cases

involved an identity of issues in

the appeals of the named and

unnamed appellants.

Ayres, 789 F.2d at 1177. The Supreme

Court's rejection of the Ayres approach in

favor of requiring the naming of parties is

emphasized by the disposition of the

difficult case before the Court. In

Torres. there was no dispute that it was a

clerical error. Further, Torres

specifically rejected a "harmless error"

analysis, 108 S.Ct. at 2409 n.3, which is

essentially what plaintiffs ask us to

adopt.

42a

If the Supreme Court wished to accept

an inquiry into intent or prejudice, it is

unclear what the real conflict between the

circuits would have been following Torres.

Justice Brennan, in dissent, also did not

believe that the majority permitted such an

approach. Justice Brennan characterizes

the majority opinion as requiring naming,

stating that the Court "[e]schew[s] any

inquiry into whether this omission was

excusable or whether respondent suffered

any prejudice . . . . the Court simply

announces by fiat that the omission of a

party's name from a notice of appeal can

never serve the function of notice, thereby

converting what is in essence a factual

question into an inflexible rule of

convenience." 108 S.Ct. at 2410, 2413

(Brennan, J., dissenting).

We need not rely upon a dissenter's

reading of the majority opinion, however,

43a

since the explicit language of Torres

supports a reading that naming is required:

"The failure to name a party in a notice of

appeal is more than excusable

'informality;7 it constitutes a failure of

that party to appeal." 108 S.Ct. at 2407.

Further, in so holding, the Supreme Court

affirmed the Ninth Circuit's holding that

[ujnless a party is named in the notice of

appeal, the appellate court does not have

jurisdiction over him." (Order reported at

807 F.2d 178 (1986), cited by Torres, 108

S.Ct. at 2407.)

Plaintiffs rely upon language in Rule

3(c) to support their argument. Rule 3(c)

states, in part, that "[a]n appeal shall

not be dismissed for informality of form or

title of the notice of appeal." Torres

indicate that this language, added to Rule

3(c) by a 1979 amendment, does not apply to

cure a failure to specify the party. See

44a

108 S.Ct. at 2407. The Court specifically

relies upon the Advisory Committee Note

following Rule 3 in concluding that the

"informality of form or title" language

would excuse informalities such as a letter

from a prisoner to a judge, thereby

effectuating an appeal. 108 S.Ct. at 2408

n .2, citing Riffle v. United States, 299

F.2d 802 (5th Cir. 1962). Torres and this

opinion do not detract from the important

principle that "the requirements of the

rules of procedure should be liberally

construed and that 'mere technicalities'

should not stand in the way of

consideration of a case on its merits."

Torres. 108 S.Ct. at 2408, citing Forman v.

Davis. 371 U.S. 178 (1962). The failure to

specify here, however, does not amount to

an "informal" departure from the suggested

"Form 1" found in the Appendix of Forms to

4 5 a

the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure.3

Other courts are in accord with the

interpretation of Torres as requiring

naming. See. e.g.. Rosario-Torres v.

Hernandez-Colon. 889 F.2d 314, 317 (1st

Cir. 1989) (en banc) f"et al." is

insufficient to designate; unnamed

plaintiffs failed to appeal); Shatah v.

Shearson/American Exp. . Inc. , 873 F.2d 550,

552 (2nd Cir. 1989) (per curiam) ("et al."

is insufficient to designate; notice of

appeal sufficient only with respect to two

parties specifically named); Marin-Piazza

v. Aponte-Rogue. 873 F.2d 432, 433 (1st

Cir. 1989) (only the party named in the

notice of appeal effectuated an appeal) ;

Akins v, Bd. of Governors of State Colleges

& Univ.. 867 F.2d 972, 973 (7th Cir. 1988)

(appeal dismissed with respect to all

"Form 1" is appended to this

opinion as "Attachment 3."

46a

individuals except the plaintiff actually

named in the notice); Gonzalez-Vega__

Hernandez-CoIon, 866 F. 2d 519 (1st Cir.

1989) (per curiam) (dismissal of 143

purported appellants not named); Santos-

Martinez v. Soto-Santiago, 863 F.2d 174,

175-76 (1st Cir. 1988) (purported

appellants dismissed where they were not

specifically designated); Cotton v. U.S.

Pipe & Foundry Co. , 856 F.2d 158, 161-62

(11th Cir. 1988) (appeal effective only as

to named parties); Meehan v. County of Los

Anaeles. 856 F.2d 102, 105 (9th Cir. 1988)

("et al. " insufficient to designate parties

to the appeal; only named plaintiff invoked

jurisdiction); Appeal of District__ of

Columbia Nurses' Ass'n, 854 F.2d 1448,

1450-51 (D.C. Cir. 1988) (per curiam) ("et

al.11 insufficient to designate unnamed

parties), cert, denied sub nom., District

47a

of Columbia Nurses' Ass'n v. District of

Columbia. 109 S.Ct. 3189 (1989).

Plainly, after Torres. the safest way

of securing an appeal is for the party or

parties seeking to appeal to state in the

body of the notice of appeal the name of

each and every party taking the appeal. A

certain element of risk must always attend

anything less than literal compliance,

particularly in light of the variety of

outcomes in this circuit and among the

circuits. The careful litigant is put on

notice to take particular care to avoid a

danger we cannot protect against.4

* Under 28 U.S.C. § 2072, it is the

special domain of the Supreme Court

assisted by input from the Judicial

Conference of the United States, see 28

U.S.C. § 2073, to promulgate Federal Rules

of Appellate Procedure for uniform

application throughout all of the circuits.

From our own disagreement, sitting en banc.

and from the opinions which have

proliferated elsewhere following Torres. it

is evident that the bench and bar continue

to be plagued by confusion in the

48a

Subject to that admonition, it would

appear to us that there may be some

departures from naming in the body of the

notice that will not be found to be fatal.

In the instant appeal, for example, where

the corporate plaintiff was stated in the

caption we conclude that the party was

properly before the court although the body

only referred to "plaintiffs." We,

therefore, disapprove of the blanket

statement in Allen Archery, Inc.-- v_;_

Precision Shooting Equip.. 857 F.2d 1176,

1177 (7th Cir. 1988) (per curiam), that

"naming [the appellant] in the caption

. . . will not do."

As long as the name appears on the

face of the document, the designation may

interpretation of the language of Fed. R.

App. P. 3(c). Both the majority and the

minority in this case believe that a

revision in the rule might be beneficial,

and we respectfully urge that consideration

be given to a change.

49a

fall within the language of Rule 3(c) that

"[a]n appeal shall not be dismissed for

informality of form or title of the notice

of appeal." Even though the use of the

term 11 et al." failed to designate other

parties to the appeal, we cannot say that

Minority Employees "was never named or

otherwise designated, however inartfully,

in the notice of appeal." Torres. 108

S.Ct. at 2409. This approach is consistent

with our previous holding that we have

jurisdiction over a named party, even

though the term "et al.11 was used. Cf. Van

Hoose. 450 F.2d at 747. Further, at least

two other circuits have adopted this

approach. See Rosario-Torres v. Hernandez-

Colon. 889 F.2d 314, 317 (1st Cir. 1989)

(en banc) (party named only in the caption

effectuated an appeal); Mariani-Giron v.

Acevedo-Ruiz. 877 F.2d 1114, 1116 (1st Cir.

1989) (same); Cotton v. U.S. Pipe & Foundry

50a

Co. , 856 F. 2d 158, 162 (11th Cir. 1988)

(two parties "named on the face" of the

notice of appeal complied with Rule 3(c)

even though they were only named in the

caption); but see Biqbv v. City of Chicago,

871 F.2d 54, 57 (7th Cir. 1989) (party must

be named in the body of the notice) . We

reluctantly accept this designation,

however, only where the caption is not

. 5inconsistent with the body of the notice.

Any ambiguity will defeat the notice.

Although this opinion should discourage the

Although the Allen Archery

statement on captions is rejected as a

blanket rule, we note that there is great

danger in naming a party in the caption and

failing to name that party in the body of

the notice. In Allen Archery, for example,

two parties purporting to appeal were named

in the caption, but only one of these

parties was named in the body of the

notice. The body of the notice stated that

"Notice is hereby given that Precision

Shooting Equipment, Inc., defendant, hereby

appeals...." Allen Archery. 857 F.2d at

1176. In such a case, we could not

disagree with the Allen Archery court that

the second party failed to appeal.

51a

practice of naming only in the caption, we

cannot say that this departure is

necessarily fatal.

Our reading does not ignore the "some

designation" or "otherwise designated"

language in Torres. 108 S.Ct. at 2409. We

consider this language as possibly