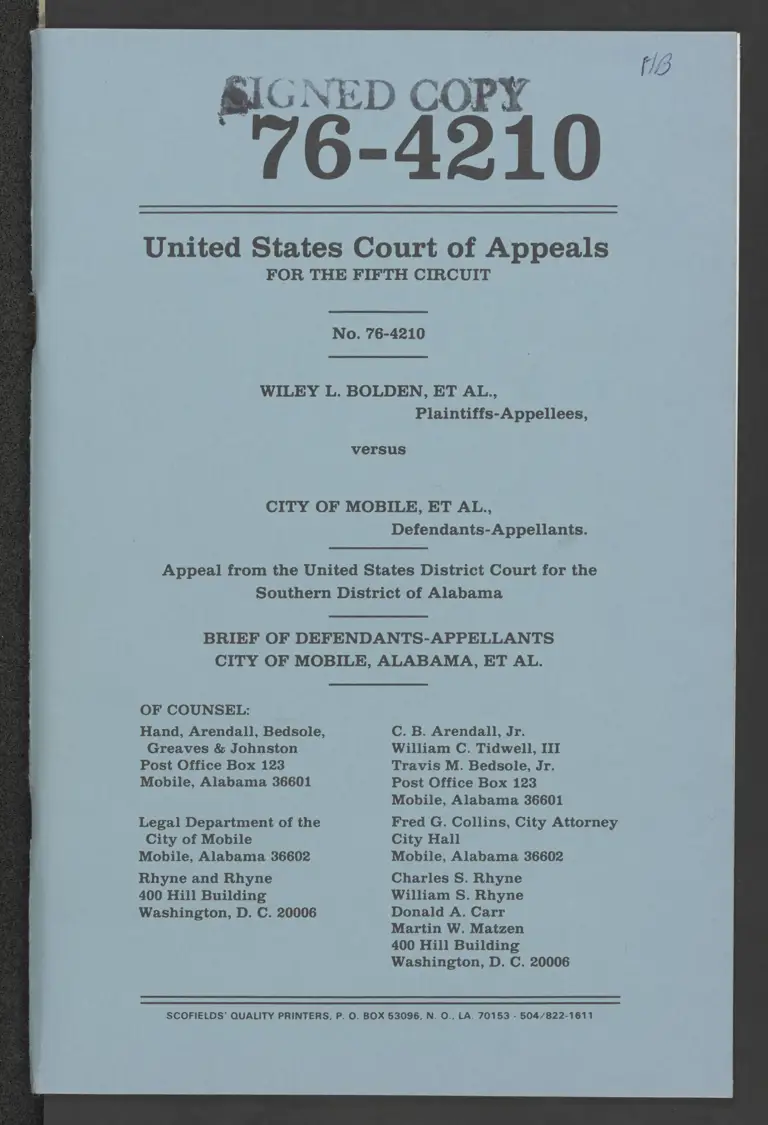

Brief of Defendants-Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 8, 1977

94 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bolden v. Mobile Hardbacks and Appendices. Brief of Defendants-Appellants, 1977. 74c39d86-cdcd-ef11-b8e8-7c1e520b5bae. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/234087d0-8904-4062-8f3e-8b52cf78e6fd/brief-of-defendants-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

81C NED COPY

76-4210

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-4210

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET AL,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

versus

CITY OF MOBILE, ET AL.

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama

BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, ET AL.

OF COUNSEL:

Hand, Arendall, Bedsole, C. B. Arendall, Jr.

Greaves & Johnston William C. Tidwell, III

Post Office Box 123 Travis M. Bedsole, Jr.

Mobile, Alabama 36601 Post Office Box 123

Mobile, Alabama 36601

Legal Department of the Fred G. Collins, City Attorney

City of Mobile City Hall

Mobile, Alabama 36602 Mobile, Alabama 36602

Rhyne and Rhyne Charles S. Rhyne

400 Hill Building William S. Rhyne

Washington, D. C. 20006 Donald A. Carr

Martin W. Matzen

400 Hill Building

Washington, D. C. 20006

SCOFIELDS’ QUALITY PRINTERS, P. 0. BOX 563096, N. O., LA. 70153 - 504/822-1611

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-4210

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET AL.

Plaintiffs- Appellees,

versus

CITY OF MOBILE, ET AL.

Defendants-Appellants.

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY FIFTH CIRCUIT

LOCAL RULE 13(a)

The undersigned, counsel of record for Defendants-

Appellants, certifies that the following listed parties

have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that Judges of this

Court may evaluate possible disqualification or

recusal pursuant to Local Rule 13(a).

The City of Mobile, Alabama

Gary A. Greenough, Commissioner

Robert B. Doyle, Jr., Commissioner

io

2

D0

Lambert C. Mims, Commissioner

C. B. Arendall, Jr. %

Attorney of Record for

Defendants-Appellants

ii

REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT

The District Court ordered the City of Mobile to

change from the Commission government under

which it has operated for 66 years to a mayor-council

government because at-large election of City Com-

missioners allegedly dilutes the voting power of

blacks. The order changing the form of a local govern-

ment goes beyond the issues heretofore presented in

voter dilution cases! and has serious implications for

all governmental units in the United States, including

Council-Manager as well as Commission systems,

which are premised on at-large elections. These im-

portant constitutional issues of voting, Federalism,

and the right of the people to choose the form of their

local government require oral argument for their

proper resolution.

1 To the knowledge of counsel for the City of Mobile, Blacks Unit-

ed for Lasting Leadership, Inc. v. City of Shreveport, No. 76-3619,

now pending before this court, is the only other voter dilution case

to order a city to change its form of government.

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Pa

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL, LOCALRULE F

1302). 530m bode pois Sitios ane Sitio ts SAehie I riaet Bs Btdfll Hits 44 ns win i

REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT .............. ii

BP ABLE OF AUTHORITIES es trirnrriney ix

STATEMENT.OP THRE. ISSURS. ...ci cnicssndses coros 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE =... . 10 (ih. 0. 2

PROCEEDINGS AND DISPOSITION

BELOW i. sa, desi ante ee snes 2

STATEMENT OF PACTS ... cern issss erin 3

A. MOBILE’'SFORMOF GOVERNMENT

WAS ADOPTED IN 1911 WITH A

RACIALLY NEUTRAL, GOOD

GOVERNMENT PURPOSE ne iv: concn 4

B. MOBILE'S ELECTORAL SYSTEM

PROVIDES EQUAL ACCESS FOR

ALL PERSONS TO THE POLITICAL

PROCESS, BLACKS PARTICIPATE

ACTIVELY AND EXERCISE

SIGNIFICANT. VOTING POWER .......... 8

1. There are No Barriers To Black

PartiCIDAION. fh reise io sidobininapcss + nv o's 8

2. All Candidates Seek The Support

Of Black Voters Because Black

Votes Are Clearly Essential To

VICIOTY. ih. os i LS th), ous 8

3. Racial Polarization In Mobile

City Commission Elections Is

Diminishing. .... aad Silas, vos 10

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

The Only Blacks Who Have Run

For The City Commission Have

Failed To Gain Significant Black

SUPP i itt Basa ides 2 bs

C. MOBILE'S COMMISSIONERS ARE

EQUALLY RESPONSIVE TO BLACK

AND WHITE CITIZENS

1 The Undisputed Facts Of The

Accessibility Of Mobile’s Com-

missioners To All Citizens. .......

There Is No Intentional Dis-

crimination In Mobile City Ser-

vices, Employment Or Ap-

POIMINERLS er ios vier reve + norerrsrcr wiisnews

Plaintiffs’ Evidence That Mobile

Commissioners Elected At-Large

Represent All Citizens Fairly. ....

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

ARGUMENT

I. MOBILE'S COMMISSION FORM OF

GOVERNMENT CLEARLY PASSES

CONSTITUTIONAL MUSTER, ............ 18

A. Atlssue Here Is The Validity Of A

Form Of Government And Not

Merely The Manner Of Its Elec-

x Fy + RRR A a Ra A RL ete i BE

1. At-large elections are a

rational and legally indispen-

sable feature of the Commis-

sion form of government. .....

eo © 0 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 oo

© 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

© ® © 6 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 8 0

Page

THR

Mey I

iis 18

wire v0

Vv

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

This Court must decide

whether proper application of

Zimmer principles required

the Court below to dis-

establish a form of govern-

ment adopted without racial

purpose 66 years ago. .........

B. Racially Discriminatory Purpose

Is An Essential Element Of Equal

Protection Violation Which Plain-

tiffs Failed To Prove.

1 In no case has this Court in-

validated an electoral system

of such long standing as

Mobile’s without a showing of

discriminatory purpose — the

Zimmer line of cases is fully

consistent with Supreme

Court decisions requiring that

purposebe sShown.& ...¢..cvu 0.

The District Court erred in

reading the element of racial

purpose out of Zimmer. .......

C. The City Government Of Mobile

In Fact Fully Satisfies The

Zimmer Test — Its Electoral

Process Is Equally Open To

Blacks And Whites.

1. The Constitution neither

creates nor protects any right

to proportional representa-

Page

a]

cise)

vi

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

tion in any racial, ethnic or

other interest group. ...::s:v: ev... 33

2. Therebeingno barrier toblack

participation in Mobile

political life, the District

Court erred in equating black

“discouragement” with denial

Of ACCESS... civvviir mini Pirates vives 35

a. The District Court correct-

ly found ‘‘no formal

prohibitions’ against

blacks in Mobile's slating

process, but erred in

permitting Plaintiffs to

bootstrap a denial of

access from unjustified

black ‘‘discouragement”

over a black candidate’s

Chance of VICIOTY, vo ..co0cv0esa 36

b. Black voters in Mobile

have significant and un-

fettered electoral power.

The Court erred in finding

that racially polarized

voting precludes effective

black participation... .'.......... 40

c. The District Court erred in

allowing Mobile’s share of

the onus of past dis-

crimination to blur its

analysis of the presently

open electoral system. ......... 43

11.

ITI.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

d. Mobile’s city ‘com-

missioners are equally

accessible and responsive

to all citizens. !.2. 5A...

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

DISREGARDING THE STRONG

GOVERNMENTAL INTEREST

BEHIND MOBILE'S CHOICE OF

COMMISSION GOVERNMENT — AN

ERROR THAT WILL IMPACT THE

THOUSANDS OF LOCAL

GOVERNMENTS NATIONWIDE

THAT EMPLOY THE COMMISSION

FORM AND THE COUNCIL-

MANAGER FORM .......-..000n

A. Zimmer Like Other Equal Protec-

tion Cases, Required That Due

Weight Be Given To Substantial

Governmental Interests Not

Rooted In Racial Discrimination.

B. Mobile’s Policy In Favor Of Its At-

Large City Commission Is Not At

All ‘“‘Tenuous.” Indeed, That

Policy Is Shared By Many Local

Governments Throughout The

Nation. © 5 nv Pr ie TP eu

THE DISTRICT COURT’S DECISION

AND ORDER WILL ACTUALLY DIS-

SERVE THE POLICIES OF IN-

TROBATION ....oisivasanivinrsaess

Page

Foe ny 48

Cold o0

viii

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

Page

A. Single Member Districts Will

Only Serve To Foster Balkanized

Enclaves And Racially Polarized

Government Which Will Actually

Reduce Both The Political Effec-

tiveness of Blacks And The Ef-

ficiency Of City Government. ......... 54

B. Single Member Districting To Ac-

complish Representation By Race

Will Serve An Impermissible

Constitutional Purpose By

Perpetuating De Jure Mobile's

Existing De Facto Pattern Of

Residentially Segregated

Enclaves. i... ii imnaihilblb. 59

IV. THE ORDERS APPEALED FROM

ARE JUDICIAL LEGISLATION

VIOLATING THE FEDERALISM

PRINCIPLES AND TENTH AMEND-

MENT OF THE CONSTITUTION OF

THE UNITED, STATES ui. tustc same aves va 61

CONCLUSION: of oi oe tidit ies Fs soda sre vs nese 64

CERTIFICATE OR SERVICE M2 its... 66

APPENDIXCA (50 cicero sain sa is abe nritld o ou 1a

ix

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. 182 (1971) ....crrccscrs si 49

Akins v. Texas, 325. U.S. 398-(1945) ../i...50: 4 duis 26

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U.S. 399 (1965) .......... 56

Avery v. Midland County, 390 U.S. 474 (1968) .23,49,62

Baker v. Carr, 389U.S. 186: (1982) +... 2. 450% NN 63

Beal v. Lindsay, 468 F.2d 287 (2d Cir. 1972) . ...... 61

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976) ....... 4,33

Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc. v.

City of Shreveport, 71 F.R.D. 623 (W.D. La.

1976), appeal pending, No.76-3619 (5th Cir.) ..... 23

Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police Jury, 508

F.2d 1100 (6th Cir. 1973) ...... 1,18,23,28,35,37,44,49

Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1 (1975) ........... 22,55

City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S.

BOR (ITD) esti nn Si Anghtis nine 26,50

Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971) ........ 19,22

Dallas County v. Reese, 421 U.S. 477 (1975) ....... 34

Dove v. Moore, 539 F.2d 1152 (8th Cir. 1976) ...... o8

Dusch v.1)avis, 3871.8. 113 (1967) .« vec s sis ow t+ 3.000 34

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U.S. 433 (19658) ... ec ce. a. 55

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ...... 31

Graves v. Barnes, 343 F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex.

1972), aff'd sub nom. White v. Regester, 412

UL, 80 755 (1973) xv0 0 1000 ete min 00 yao ais whosnguanin #ogoss sisi A BS 34

xX

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th

Cir. 1971), aff'd on rehearing en banc, 461

F.2d 1171: (1972)... 0 an Ne SE 25,46,61

James v. Wallace, 533 F.2d 963 (5th Cir. 1976) ..... 46

Jolly v. United States, 488 F.2d 35 (5th Cir.

R74) ods ireninis AE PE Ph SEY ee ae vin vopanitle 3

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

LAD73Y re iirian ive i sds heh A als ale va ens 26

Lipscomb v. Wise, 399 F. Supp. 782 (N.D. Tex.

105) RE TEX 55,61

McGill v. Gadsden County Commission, 535

¥.24 277 (bth. Cir. 1976) :...... 1,18,19,22.23 28,35,37,

43,44,49

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) .......... 61

National League of Cities v. Usery, 426 U.S.

833, 96'S, CL. 2465'(19768) '.... oN AA 62,64

Nevett v Sides, 533 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir.

1978), trons ahset sod tors ps a i as 1,18,34,38,65

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) ........... 62

Paige v. Gray, 538 F.2d 1108 (5th Cir. 1976) . ...... 31

Perry v. City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639 (5th

Cir: A975). ... AGE, J ELE 0 sd BG Sis ull ov ous 20

San Antonio School District v. Rodriguez, 411

U.S. 1 C1073) p cimgernsrtions dont wht in entes' fot bogies wor oi pst 64

Taylor v. McKeithen, 499 F.2d 893 (5th Cir.

1075) ccviciasionenuniusancnesoinsnes spionahs S00 J) 59

Turner v. McKeithen, 490 F.2d 191 (5th Cir.

1973) .....:.. Ee ee see isi ln ie sie wa hws 20,34,35,36

x1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

United Jewish Organizations of

Williamsburgh, Inc. v.Carey, U.S.

45 U.S.L.W. 4221 (U.S. March 1, 1977) .1,18,24,29,31,

33,34,38,60

United States v. Board of School Com-

missioners of Indianapolis, 541 F.2d 1211

(7th "Cir."1976), vacated ..._ U.S. __._.., 45

U.8i1.W. 3508 (U.S.Jan, 25, 1077).cocensnsvmsnesse 26

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., — U.S. :

07 S..C1.-555 (1977) coins ivinis = sieisiosinonsas 1,18,24,30,31,50

Vollin v. Kimbel, 519 F.2d 790 (4th Cir. 1975) ..... 34

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975),

vacated 425 U.S. 947 (1978)... .s. aise 20,27,34,45

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ..1,18,24,29,

30,31,46,65

Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) .. 4,19,23,24,

28,33,49,53,63

White v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973) ...... 19,23,30,

35,43

Wilson v. Vahue, 403 F. Supp. 58 (N.D. Tex.

1978) ia hams SAGAN BRR Gh sme. 27,58

Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964) ..26,31,55,58

Young v. American Mini Theatres, Inc., ___

U.S. » I0S, C1. 240° (A076) ~.- . . i. see 62

Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir.

1973) (en banc), aff’d sub nom. East Carroll

Parish School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S.

B38 (1978)... 3,17,19,20,23,32,33,34,43

xii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

Constitution and Statutes: 8

Ala. ActS NO, 281 (1011): oc in eivie fon sms ubisishy medete os 6

Housing and Community Development Act of

1974, 42 U.S.C. 859301 ef seq... covdaRed SA 61

U.S. Constitution

ANMCIVUIMNOBN RAV srs 2.0 t.0is50 2.5 oto hes tensiriss 2e 3a 1,23,58

AMENOMENL XV au. co vinci totes Ageless wines + spas 2,58

AMENAMENT X virins vias « susie + mae witne drersasis wir <3 ws das 2

Voting Rights Act, §5, 42 U.S.C. §1973c ........ 24,26

Miscellaneous:

E. Bradford, Commission Government in

American Cities: (3911) J... 5 0. Gali. uu 6,52

A. Bromage, Introduction to Municipal

Government and Administration (1957) ........ 52

D. Cambell, J. Feagin, Black Politics in the

South: A Descriptive Analysis, 37 Journal

Of: POLUICS 1120 (1975) 1 15.000 sie coi o saniie 0 abeasrsss wink 39

Carpeneti, Legislative Apportionment: Mul-

timember Districts and Fair Representa-

tion, 120 U.Pa.L.Rev. 666 (1972) .............. 24,57

S. Carmichael, C. Hamilton, “The Search for

New Forms,” in Power and the Black Com-

munity (S. Fisher.ed. 1070) ...cvnvunvonsnssomnns 52

L. Cole, Electing Blacks To Municipal Office,

Urban Affairs Quarterly 17 (September,

BOTAN oo cine sins sna tans EAE BTR SUT 4 gba 4 48 0 4 40

F. Donnelly, “Securing Efficient Administra-

tion under the Commission Plan,” Annals

of the American Academy of Political and

Social Science 218(1912) ....................... 54

xiii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Page

The 50 States and Their Local Governments

(J. Fesler-ed: 1987) '..c... occas codvvidsd sa dvb, o1

C. Gilbert, Community Power Structure

(1972) a Rea VA SRR 53

International City Management Ass'n, The

Municipal Yearbook (1976, 1972) ...:...cs.r avs 53

Jewell, Local Systems of Representation:

Political Consequences and Judicial

Choices, 36 Geo. Wash. L.. Rev. 790 (1968) ... 56,63

R. Lineberry, E. Fowler, Reformism and

Public Policies in American Cities, 61 Am.

Political Science Rev. 701°(1971) ............ 51,53

C. McCandless, Urban Government and

POLICES (1070) cides isssisesinsmsnnsons is 5,52,57

MacKenzie, Free Elections (1958) ................ 56

Note, 81 Harv. 1... Rev. 1851 (1974) ................ 55

Note, Ghetto Voting and At-Large Elections:

A Subtle Infringement Upon Minority

Rights, 59 Geo. L. Rev. 989 (1970) {wn ull. 56

J. Rehfuss, Are At-Large Elections Best for

Council Manager Cities?, 61 National Civic

Review B86 (1072) oo. ce vr iir iris tine tithes mgr dries 52

B. Rustin, “From Protest to Politics: The

Future of the Civil Rights Movement,”

reprinted in Black Protest Thought in the

Twentieth Century (A. Meier ed. 1971) ......... 43

U.S. Bureau of the Census, Governing Boards

of County Governments: 1973 (1974) ............ 53

Xiv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Continued)

Woodruff, City Government by Commission

KAO11Y ovis «orvims mn nnsitiniv ities io ha ReiDRn ols dh in PEWS + Eo) 51

Wright v. Rockefeller and Legislative Ger-

rymanders: The Desegregation Decisions

Plus a Problem of Proof, 72 Yale L.J. 1041

BLOB DY reisninele srs nccatahin + Aatadotat Sa # EAE S Shh 93S 489 80 2 2 of 56

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-4210

WILEY L. BOLDEN, ET AL,

Plaintiffs- Appellees,

versus

CITY OF MOBILE, ET AL,

Defendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Alabama

BRIEF OF DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

CITY OF MOBILE, ALABAMA, ET AL.

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED ON REVIEW

1. Whether the District Court erred in holding that a

showing of impermissible racial purpose was con-

stitutionally unnecessary to Plaintiffs-Appellees’

claim that Mobile’s 66 year old city Commission

form of government and at-large electoral system

is violative of the Fourteenth Amendment, in light

of the decisions of the United States Supreme

Court in Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976);

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Corp., "U.S. _; 975. Ct 555 (1977);

and United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, ___

U.S. , 45 U.S.L.W. 4221 (1977) and the decisions

of this Court in Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police

Jury, 508 F.2d 1109 (5th Cir. 1975); Nevett v. Sides,

533 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir. 1976); and McGill v. Gadsden

County Commission, 535 F.2d 277 (5th Cir. 1976).

Whether the District Court erred in holding that

racially polarized voting denied blacks access to

the political process, where Plaintiffs-Appellees’

own evidence established that blacks participate

actively and powerfully in Mobile politics, both in

elections and in administration by elected of-

ficials, where the only black candidates to run for

the City Commission have been outpolled by their

opponents even among black voters, and in light of

the decision of the Supreme Court in United Jewish

Organizations, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4227, that racially

polarized voting is not of independent Con-

stitutional significance.

Whether the District Court erred in holding that

the Federal Constitution requires that Mobile’s

2

electoral system be so arranged as to guarantee

blacks the ability to elect black candidates as

members of the City’s governing Board.

4. Whether the District Court had power under our

Federalism system and Tenth Amendment of the

United States Constitution to enter orders

legislating a new form of government for Mobile

which provides blacks a ‘quota’ or proportional

representation in Mobile’s governing board

according to their population in Mobile.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Proceedings And Disposition Below

Plaintiffs on behalf of all black citizens of the City of

Mobile filed suit against the City and its three Com-

missioners alleging that at-large election of City

Commissioners unconstitutionally dilutes their

voting strength in violation of the first, thirteenth,

fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments, the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, 42 U.S.C. §1973 et seq., and the Civil

Rights Act of 1871, 42 U.S.C. §1983. R. 1, 548.2 They

alleged jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1331 and §1343. R.

1. The district court found that a claim upon which

relief could be granted had been stated against the

Commissioners under 42 U.S.C. §1983 and against both

the Commissioners and the City on claims grounded

on the Voting Rights Act with jurisdiction over such

2 Appellants have elected to defer filing of the Appendix. The

original pages of the record on appeal will be citedas R. __. The

first page of the transcript (numbered “1” by the court reporter)

has been numbered page “621” of the record by the district clerk,

but the subsequent pages of the transcript have not been numbered

by the clerk. For clarity, the original pages of the transcript, as

numbered by the court reporter, will be cited as Tr. __.

3

claims existing under 28 U.S.C. §1343(3) and (4). R.

549.

After trial the District Court issued an opinion pur-

portedly relying on the criteria set forth in Zimmer v.

McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973) and holding

that at-large election of City Commissioners un-

constitutionally dilutes black voting strength.¢ Con-

cluding that district residence requirements and dis-

trict election of City Commissioners would be “im-

provident and unsound,” the Court ordered relief

abolishing the Commission government and sub-

stituting a mayor-council government with council

members elected from single-member districts.5

Statement Of Facts

The District Court granted Plaintiffs’ prayer that

Mobile’s Commission form of government be replac-

ed by a Mayor-Council government elected from nine

single-member districts.

This case did not involve any reapportionment or

other voting change® under the Voting Rights Act, 42

U.S.C. §1973, but was a challenge to the status quo of an

at-large Commission form of government in opera-

3 The District Court also saidit had jurisdiction over the asserted

claims under 28 U.S.C. §2201, the declaratory judgment section. R.

549. This statement is erroneous since §2201 is not a jurisdictional

statute. Jolly v. United States, 488 F.2d 35 (5th Cir. 1974) (per

curiam).

4 District Court Opinion and Order entered October 21, 1976. R.

548-603. The District Court opinion is reported at 423 F. Supp. 384

(S.D. Ala. 1976).

5 The District Court’s 59 page remedial order was entered on

March 9, 1977. Defendants, as a matter of caution, filed a notice of

appeal from that order on March 18, 1977.

6 Cf. Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973).

T

i

i

a

tion for 66 years. The evidence showed that the City’s

form of government was adopted for no racial purpose

but to wipe out ward parochialism and corruption,

that there are no barriers to participation by blacks in

the political process and that blacks do in fact par-

ticipate actively and influentially. The District Court

based its order upon a putative constitutional right in

blacks to elect blacks to the City governing body.

Finding that the Mobile electoral system was not so

arranged as to guarantee such a result, the Court

ordered the adoption of a plan embodying propor-

tional representation by race, there being 67,356

blacks and 122,670 whites in the City.

The Supreme Court in Beer v. United States, 425 U.S.

130, 136n.8 (1976) expressed its position on the ques-

tion presented here:

“This Court has, of course, rejected the proposition

that members of a minority group have a federal

right to be represented in legislative bodies in

proportion to their numbers in the general popula-

tion. See Whitcomb v. Chavis, 403 U.S. 125, 149.”

A.

Mobile’s Form Of Government Was Adopted In

1911 With A Racially Neutral, Good Government

Purpose

Mobile’s Commission-type municipal government

was established”in 1911 by Alabama Act No.281 (1911)

7 In 1963 and again in 1973, the people of Mobile rejected

proposals to change from the commission form to a mayor-council

government. (R. 435)

5

p. 330. Under this form of government, three Com-

missioners are elected to specific positions. Each

Commissioner engages in specific administrative

tasks involving certain City Departments (Public

Works and Services, Public Safety, and Finance) plac-

ed under his control. The Mayoralty, a largely

ceremonial post, is rotated among the Com-

missioners. All Commissioners are elected at-large.

The Commission form of government was first

created in Galveston, Texas, in 1900. Within twenty

years it had spread rapidly to approximately 500

Cities and other local governments in the North as

well as the South. It isnow employed by approximate-

ly 540 local governments across the nation.8 Commis-

sion government is founded upon two fundamental

principles. First, its structure is designed to foster

corporate management-type efficiency of operation

through the creation of clear lines of known public

responsibility for specific aspects of the

government's affairs. Woodruff, City Government by

Commission 29 (1911). Second, every voter is to be a

constituent of each Commissioner, thus alleviating

the “ward-heeling” and “logrolling’ that characteriz-

ed the aldermanic or councilmanic systems in the ear-

ly 1900’s. As one political scientist of the time stated:

“...[U]nder the ward system of representation, the

ward receives attention, not in proportion to its

8 Political scientists attribute the relative decline in adoptions

by governments of the Commission form to the rise of Council-

Manager government, which is founded upon the same essential

premises and which also rests upon at-large voting to assure that

officials maintain a City-wide perspective. McCandless, Urban

Government And Politics 168 (1970). Some 2000 local governments

employ Council Manager government.

a

T

S

T

S

I

6

needs, but to the ability of its representatives to

“trade” and arrange ‘““‘deals’” with fellow members.

The pernicious system of logrolling results.

‘To secure one more arc light in my ward, it was

necessary to agree to vote for one more arc in each of

the other seven wards; said a former councilman;

‘the City installed and paid foreight arc lamps when

only one was needed! So with sewer extensions,

street paving and grading and water mains. Nearly

every City under the aldermanic system offers

flagrant examples of the vicious method of ‘part

representation.’ The Commission form changes this

to representation of the City as a whole.” Bradford,

Commission Government in American Cities 165

(1911).

The District Court concluded that at-large elections

are inherently necessary (423 F. Supp. at 387) to the

Commission form of government, and that even the

imposition of ward residence requirements for the

Commissioners would be unconstitutional. The Dis-

trict Court reasoned that the accountability of a City

Commissioner who has command of a particular func-

tion and jurisdiction over the entire city may not be

limited to only a portion of the electorate (423 F. Supp.

at 402 n.19).

At the time Alabama Act No. 281 was passed, blacks

in Alabama did not have effective use of the franchise.

There was no racially discriminatory purpose to Act

No. 281.

Undisputed testimony adduced at trial established

the purpose of instituting the Commission form of

government in Mobile in 1911:

Q Now, I will ask you whether or not a study of the

newspaper articles of that time and the quotations of

the comments made by persons such as Mayor Pat J.

Lyons demonstrates that the change of the City

Commission form was sold on the basis of business

and other considerations completely unrelated to

race?

A Iwouldagreethatthe basic approach inthe cam-

paign to change the form of government of the City

of Mobile would be an appeal to what would be called

progressive economic motivation, the idea of mov-

ing to a more business like form of government.

Q And this movement, in Mobile, had its counter

part all over the United States, at that time, did it

not?

A And before that time.

Q In areas where there were no blacks or substan-

tially none?

Yes. That would be true.

Des Moines, that is one?

Yes.

Dayton, that is another?

Yes.

And it was not, in these other places, either,

motivated by racial considerations, was it?

A No.

(Testimony of Plaintiffs’ expert witness McLaurin,

July 12, 1976, Tr. 36-37).

O

P

O

P

O

»

The District Court held that a finding of “initial dis-

criminatory purpose” (423 F. Supp. at 398) was un-

necessary in the determination of whether Mobile's

form of government and electoral system are un-

constitutional.

a

B.

Mobile’s Electoral System Provides Equal Access

For All Persons To The Political Process, Blacks

Participate Actively And Exercise Significant

Voting Power

1. There are No Barriers To Black Participation.

It is undisputed that every phase of the processes of

registration, voting, qualification and candidacy for

the Mobile City Commission is as open to blacks as to

whites.

This is not a case where, despite the lack of formal

prohibitions on registration or voting, minorities are

effectively excluded by white-dominated slating

organizations. There are no such slating

organizations in Mobile. Nor is this a case where a

political party structure fails to solicit minority par-

ticipation, and where that party’s nomination is tan-

tamount to election. Mobile’s City Commission elec-

tions are conducted on a non-partisan basis.

The District Court found that “blacks register and

vote without hindrance,” and that there are no

“prohibitions against blacks seeking office in

Mobile.” (423 F. Supp. at 387).

2. All Candidates Seek The Support Of Black Voters

Because Black Votes Are Clearly Essential To Vic-

tory.

It is undisputed that this is not a case in which

minority voters are ignored as inconsequential, or in

which a candidate may be elected without minority

support.

The testimony of every witness, Plaintiffs’ as well as

Defendants’, is replete with evidence that every can-

didate for the Mobile City Commission actively seeks

black votes. (Tr. 264, 320-22, 412, 539-40, 752, 824, 927,

1141).

Plaintiffs’ witness Rev. Hope, the leader of the Non-

Partisan Voters League (NPVL) which is the principal

black political organization® in the City of Mobile,

testified as follows (Tr. 413-14):

Q Isn’t it a fact, Reverend Hope, in the course of

your connection with the league, its endorsement

has been actively sought by candidates over the

years that you have been connected with it?

A Yes, sir. Definitely so. I explained that to start

with.

Q And wasn’tthat trueinthelast City Commission

race in 1973?

A Yes, sir.

Q Every candidate in the race sought your

endorsement, didn’t they?

A: Yes, sir.

* * * * *

Q Let me ask you this. Didn’t the black vote in

effect put Gary Greenough [one of three current

Mobile City Commissioners elected in 1973] in of-

fice?

A I wouldn’t say the black vote alone, sir.

9 The NPVL was formed in 1963 as the “underground” local arm

of the NAACP, after the local branch was enjoined from political

activity in Mobile for failure to surrender its membership list. The

NPVL is still a separate branch of the NAACP. (Testimony of

Plaintiff Wiley Bolden, July 12, 1976, Tr. 208).

10

THE COURT:

Was it the difference?

A 1 believe so.

THE COURT:

All right.

The current Mayor, Lambert C. Mims, was re-elected

in 1969 and 1973 to the Commission! with the endorse-

ment of the Non-Partisan Voters League.

It was also undisputed that City Commissioner

Joseph Langan was elected and re-elected from 1953

through 1969 with vital support from black voters. (Tr.

292-295). The testimony further established that Mr.

Langan’s defeat in 1969 was attributable to a loss of

support from black voters. (Tr. 295, 304).

3. Racial Polarization In Mobile City Commission

Elections Is Diminishing.

Expert testimony adduced at trial showed that the

black versus white, schismatic voting trends of the

1960s have been significantly reduced and that the

trend is towards “a situation in which race will not be a

major political issue.” (Tr. 1136). There is presently

more difference in voting patterns between blacks of

different economic levels than between whites and

blacks of similar economic levels. (Tr. 1135).

Plaintiff Wiley Bolden testified (Tr. 214-15) that:

Q In your opinion, it is proper to characterize the

10 The other current City Commissioner, Robert B. Doyle, Jr.,

was unopposed in the 1973 election.

11

black voters of the City of Mobile as now con-

stituting a block vote?

A "No, sir.

THE COURT:

He is not suggesting coercion. What he wants to

know, is do the black voters usually vote for the

same candidate?

A No, sir.

The testimony showed that the political reality in

Mobile now is that “a candidate who would raise the

racial issue in a City Commission election would cost

himself as many votes as he would gain, if not more.”

(Tr 1177).

4. The Only Blacks Who Have Run For The City Com-

mission Have Failed To Gain Significant Black

Support.

Plaintiffs’ expert testified that racially polarized

voting in City Commission contests was not

diminishing, explaining that statistical regression

analysis showed a high degree of correlation between

voters’ race and the votes they cast. Dr. Schlicting

testified that the votes for three black candidates for

City Commissioner in the 1973 election showed a par-

ticularly high correlation with race. (Tr. 173-75).11

11 The only other evidence of recent polarization of voting

patterns (423 F. Supp. at 388) pertained to elections to the Mobile

County Commission and the Mobile County School Board, which

the evidence showed to involve a “different kind of constituency”

(Tr. 312) and different issues. (Tr. 602, 1170-72). The District Court

consolidated final argument in this case with argument in Plain-

tiffs’ action challenging the constitutionality of at-large elections

to the County Commission and County School Board. (Tr. 1414).

12

Other of Plaintiffs’ witnesses (Tr. 246-47, 365, 384,

507, 566) testified that their objection to Mobile’s form

of government was that because of such polarization it

is “futile” for blacks to run in a city-wide election.

It is undisputed that none of the three black can-

didates in 1973 (who were the only blacks ever to run

for the City Commission) carried the black census

wards. (Tr. 175). Black voters supported white can-

didates over those of their own race. (Tr. 1128).

The District Court adopted the view (423 F'. Supp. at

389) that itis impossible for black candidates to win at-

large elections unless there is a black voting popula-

tion majority. The District Court ignored evidence of

the success of black candidates in at-large elections

in, for example, Birmingham, Alabama (Tr. 739-40),

and many other places across the nation.

The District Court found (423 F. Supp. at 399) that the

undisputed evidence of the absence of barriers to black

registration, voting, or candidacy, and the undisputed

evidence of active black participation and electoral

power were irrelevant, because due to polarized

voting prospective black candidates “shy away’ from

running in City at-large elections. The record with

respect to the electoral success in other predominant-

ly white cities of black candidates who have not

“shy[ed] away’ from at-large contests is set forth at

pp. 39-40, infra.

13

C.

Mobile’s Commissioners Are Equally Responsive

To Black And White Citizens

1. The Undisputed Facts Of The Accessibility Of

Mobile’s Commissioners To All Citizens.

Plaintiffs’ witnesses, testifying to alleged

“unresponsiveness” of the Mobile City government,

all testified that on numerous occasions they had

taken problems large and small directly to the highest

level of the City government, where they were af-

forded hearings.

Plaintiffs’ witness Seals, a black, testified that he

had met with all three Commissioners at least four

times, and had no difficulty obtaining a hearing. On

one occasion, he requested additional street lighting

for his area, and got it. On one occasion, he requested

relief in connection with sewers, and got it. On another

occasion, he requested sidewalks, and they were con-

structed (Tr. 433-34).

Plaintiffs’ witnesses Wyatt and Smith, also black,

testified that they had been to City Hall where they had

direct access to and met with all three Commissioners.

(Tr. 572-73, 583).

Plaintiffs’ witness Randolph, a black, testified that

he had known Commissioners Mims and Doyle “for

years” (Tr. 622, 624-25) and also Commissioner

Greenough, and had ready access to them. Randolph

sought street paving for one of Mobile’s black com-

munities, and got it. He asked for better street lighting,

and got it. (Tr. 621-22).

14

2. There Is No Intentional Discrimination In Mobile

City Services, Employment Or Appointments.

It was undisputed at the trial that certain problems

exist regarding city services, but that those problems

affect white as well as black citizens of Mobile. (Tr.

436-37, 875, 893-94). Much of the new paving in the

newer, and predominately white, areas of the city has

been done by private developers without the use of

public funds. Indeed, most of the paving done by the

City of Mobile, as opposed to private developers, is in

black areas. (See Defendants’ Exhibits 60-A, 60-B, 60-

E). It was undisputed that any disparity is not pur-

poseful, based on race, and that the cost of paving non-

thoroughfare streets is assessed to abutting property

owners and such assessments have not been paid by

some black neighborhoods. (Tr. 644-648, 886-88).

The City is spending millions of dollars in a long-

term program to correct tremendous drainage

problems affecting low-lying inexpensive housing

which is principally black-occupied. (Tr. 872-73, 876-

82). The District Court’s opinion stated (423 F'. Supp. at

391) that all emergency drainage projects were in

white areas. The evidence (Tr. 1253-54, 1260, 1278, 1280-

81) showed that in fact many emergency projects

benefitted black areas.

Mobile has made substantial efforts in housing code

enforcement. In one black neighborhood where only

18.5% of the homes were rated standard in 1966, four

times that many were standard by 1975. (Tr. 1357-63).

Public employment statistics showed that 26.8% of

the city work force is black,!? and that many black City

12 Thirty-five percent (35.48%) of Mobile’s population is black.

15

employees are in lower paying jobs. It was undisputed

that no black employee receives less pay than a white

for the same position, and that any disparity is not

purposeful. (Tr. 813-14). Skilled blacks are in such de-

mand in private industry that few seek employment

with the lower-paying City. (Tr. 912-13, 995-96). By

State law Mobile may only hire employees from lists

prepared by the County Personnel Board, which is not

subject to City control. (Tr. 828). A Bill to change this

procedure has been introduced in the State legislature.

(Tr. 938).

Uncontroverted statistics showed that whereas 7 of

179 (3.8%) prior appointments to City boards and com-

mittees were to blacks, total membership has now

been brought to 46 of 366 (12.5%). (Tr. 831). Many of the

positions require both certain qualifications and

nomination by certain non-governmental groups. (Tr.

835, 840-41, 864, 912-14, 918-20). Plaintiffs did not ad-

duce any evidence that qualified, nominated blacks

were purposefully refused appointment by the City.

Plaintiffs asserted and the District Court found (423

F. Supp. at 392) that generally unequal treatment was

exemplified by an inordinately slow City reaction to

an instance of alleged police brutality against a black.

It was undisputed that an investigation was com-

menced the day after notice of the alleged incident, and

the officers allegedly involved were suspended four

days later (Tr. 795, 799, 821). The District Court

thought that unresponsiveness was also indicated by

the fact that the City Commission had not adopted an-

tidiscrimination ordinances duplicating Federal

laws, by the fact that the Commissioners had not

spoken out against cross burnings reported to have

16

occurred outside the City, and by a single purported

exception to a generally evenhanded!? park and

recreation program. 423 F. Supp. at 392.

3. Plaintiffs’ Evidence That Mobile Commissioners

Elected At-Large Represent All Citizens Fairly.

After cross examination elicited the testimony of

Rev. Hope that every City Commission candidate ac-

tively solicited the support of black voters, and that

the NPVL had “notable success” in electing can-

didates that it supported (Tr. 413), the following

questions (Tr. 417-18) were put to Rev. Hope on re-

direct:

Q Reverend Hope, in answering [counsel for

Mobile] questions, did you mean to say that every

candidate that the Non-Partisan Voters League has

endorsed has turned out to represent the interests of

the black community fairly?

A In recent years they have.

Q How recent do you mean when you say recent

years?

A In thislastelection and maybe the election prior.

I think, in my opinion, they have done a very good

job in carrying out their obligations toward trying

to be fair to all people.

Q Is that your opinion or the opinion of the entire

League?

A Yes, thatistheopinion —thatiswhatlamtrying

to speak for. They feel that the candidates they have

elected in recent years have done a very good job

along that line.

13 The evidence showed that black areas receive more than their

share of city-provided recreation services, whether viewed on the

basis of numbers of facilities, personnel employed, or payroll ex-

penditures. (Tr. 1371-80).

17

The District Court held (423 F. Supp. at 400) the per-

formance of the City government with respect to ser-

vices, employment and appointments to be

“unresponsive.” The District Court concluded (423

F. Supp. at 401-402) that Mobile’s long-standing

choice of the Commission form of government merely

indicated that Plaintiffs did not prevail on the “no

tenuous State policy” aspect of the “aggregate of fac-

tors” showing required by Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485

F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973), and that Mobile's policy

choice was outweighed by a requirement to guarantee

blacks ‘“‘a realistic opportunity to elect blacks to the

City governing body.” (423 F. Supp. at 403).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The unprecedented decision of the District Court

completely disestablishes Mobile’s Commission form

of government.That form of government is of sixty-

six years standing, and serves numerous important

and legitimate policy choices. That form of govern-

ment was adopted with no racial purposes whatever.

The District Court erroneously held these factors to be

irrelevant.

The evidence showed that there are no impediments

to participation by blacks in the political processes of

Mobile, and that blacks are actively and powerfully in-

volved. The District Court, however, reached the un-

supportable conclusion that local governments must

"be so arranged as to ensure that blacks can elect

blacks and made a wholly unfounded assumption that

black candidates cannot win in the at-large elections

which are legally indispensable to Commission

government. In many cities in the South as well as in

the North, where blacks are a minority of the voting

18

population, black candidates have won at-large elec-

tions. There is no reason to presume that black can-

didates cannot win such elections in Mobile. The only

black candidates to run for the Mobile City Commis-

sion have been outpolled by their opponents even

among black voters.

The United States Supreme Court has in

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976); Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop-

ment Corp., U.S. ____, 97 S. Ct. 555 (1977); United

Jewish Organizations v. Carey, —___ U.S. , 45

U.S.L.W. 4221 (1977) has made it clear beyond mistake

that the racial purpose absent here is an essential ele-

ment of the Fourteenth Amendment violation the Dis-

trict Court purported to find. The Supreme Court has

also rejected any notion that racial or ethnic groups

have a Federal constitutional right to elect their

members to office. Fifth Circuit decisions in other con-

stitutional voting cases are completely in accord with

these principles. Bradas v. Rapides Parish Police

Jury, 508 F.2d 1109 (5th Cir. 1975); McGill v. Gadsden

County Commission, 535 F.2d 277 (5th Cir. 1976);

Nevett v. Sides, 533 F.2d 1361 (5th Cir. 1976). The Dis-

trict Court’s opinion and orders, which would require

the invalidation of all Commission and Council-

Manager governments similarly premised on at-large

elections, amount to Federal judicial legislation

flagrantly violative of the Federalism principles and

the Tenth Amendment to the Constitution of the Unit-

ed States, and must be reversed by this Court.

ARGUMENT

I. Mobile’s Commission Form Of Government

Clearly Passes Constitutional Muster.

19

In Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc), affirmed sub. nom. East Carroll Parish

School Board v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976), this

Court dealt with an action challenging an at-large

electoral system on the basis that the system denied

blacks access to the political process in violation of

the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend-

ment. Drawing upon the decisions in Whitcomb v.

Chavis, 403 U.S. 124 (1971) and White v. Regester, 412

U.S. 755 (1973), this Court set forth a “panoply of fac-

tors” upon which proof of such an Equal Protection

claim might be founded. 485 F.2d at 1305. Applying

these factors to the facts of Zimmer, this Court con-

cluded that plaintiff-intervenor had met his burden of

proof, and reversed its earlier panel decision. 485 F.2d

at 1307, 1308.

The Supreme Court affirmed “without approval of

the constitutional views’ expressed by the Zimmer

court. East Carroll, supra, 424 U.S. at 638. The

Supreme Court viewed the case as one involving not

the constitutionality vel non of multimember district-

ing allegedly denying minority access to the political

process, but rather the issue of how malapportion-

ment should be corrected by the federal courts under

Connor v. Johnson, 402 U.S. 690 (1971). Yet Zimmer

remains the controlling precedent of this Circuit. E.g.,

McGill v. Gadsden County Commission, 535 F.2d 277,

280 n.6 (5th Cir. 1976).

Appellant City has no quarrel with the holding of

Zimmer, which on its facts was well-grounded upon

the teachings of both Whitcomb and White, supra. But

on any proper application of Zimmer, Mobile’s form of

government and electoral system clearly pass con-

stitutional muster.

20

A. At Issue Here Is The Validity Of A Form Of

Government And Not Merely The Manner Of

Its Election.

Zimmer, as the Supreme Court emphasized in East

Carroll, supra, was in fact a reapportionment case.

The governmental units there involved could func-

tion, and in fact had functioned for years, with elec-

tions by district rather than at-large. 485 F.2d at 1301.

Indeed, there had been a “firmly entrenched state

policy against at-large elections” for such units until

1967. 485 F.2d at 1307. No change in the form or func-

tion of these units was therefore necessitated by re-

quiring their election by single-member wards or dis-

tricts. This is equally true in every other case of this

genre decided by this Court. E.g., Turner v. McKeithen,

490 F.2d 191, 192 (1973) (Parish Police Jury, mixed

multi-member, single-member ward plan);

Wallace v. House, 515 F.2d 619, 622 (5th Cir. 1975),

vacated 425 U.S. 947 (1976) (Board of Aldermen, entire-

ly at-large plan susceptible to districting); Perry v.

City of Opelousas, 515 F.2d 639, 640 (5th Cir. 1975)

(Board of Aldermen, entirely at-large plan with ward

residency requirement).

In contrast to all prior cases before this Court,

Mobile’s at-large electoral system is an integral and

essential part of its Commission form of government.

1. At-large elections are a rational and

legally indispensable feature of the Com-

mission form of government.

Mobile’s Commission Government was adopted in

1911 within the context of the progressive reform

movement which prompted many other

municipalities throughout the Nation to do likewise.

21

(Tr. 24-25). As the testimony of Plaintiffs’ historian

and other witnesses clearly demonstrates, Mobilians,

like citizens of other cities swept by the reform move-

ment, sought a city government both more efficient

and business-like, and less susceptible to ward

parochialism and corruption than the aldermanic or

councilmanic forms. (Tr. 24-25, 36-37).

The very structure of Commission government con-

stitutionally admits of but one form of electoral

system — at-large elections. Because each Com-

missioner administers a separate department with

city-wide functions — here Public Works and Ser-

vices, Public Safety, and Finance (423 F. Supp. at 386)

— each Commissioner must be dependent upon the en-

tire electorate of the City for his election. As the Dis-

trict Court here recognized, election of officials with

specific city-wide responsibilities from geographic

districts would clearly be not only “improvident and

unsound” but unconstitutional. (423 F. Supp. at 387,

402 n. 19).

2. This Court must decide whether proper

application of Zimmer principles re-

quired the Court below to disestablish a

form of government adopted without

racial purpose 66 years ago.

For over 65 years, Mobile has operated under a

“facially neutral” form of government (423 F. Supp. at

398), which was adopted without racial purpose, as

testimony of Plaintiffs’ own historian and others

clearly demonstrates. (Tr. 24-25, 36-37). Indeed, as the

District Court found, the Alabama legislature in 1911

was acting in a ‘“‘race-proof situation” in adopting

22

Mobile’s form of government. (423 F. Supp. at 397). As

in McGQGill v. Gadsden County Commission, 535 F.2d

277, 281 (5th Cir. 1976),

“This policy could not have had racist underpin-

nings because other, less subtle state mechanisms

has already disenfranchised almost all black voters

2

Thus, the policies behind Mobile’s Commission

Government are not rooted in racial discrimination,

but in the reform movement for more effective and

businesslike government. Here, unlike Zimmer and

Turner, the electoral system was clearly not “conceiv-

ed as a tool of racial discrimination.” Wallace v.

House, supra, 515 F.2d at 633. Nor is there the “ap-

parent absence of any rational state or local policy in

support of the all at-large system” present in Zimmer

and Turner. Id., 515 F.2d at 631-32. Indeed, given both

the substantial need for city-wide perspective and the

constitutional necessity for at-large election of the

City Commissioners, this is the case contemplated in

Zimmer where

“significant interests [are] advanced by the use of

[at-large elections] and the use of single member

districts would jeopardize constitutional re-

quirements.” 485 F.2d at 1308.14

14 A district court could therefore employ at-large elections and

be fully justified in departing from the Federal judicial preference

for single-member districting enunciated in Connor v. Johnson,

supra. Id. Because such considerations would support a judicial

choice of at-large elections, they clearly support the legislative

choice made by the citizens of Mobile and the Alabama legislature

in 1911. See Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 18-19, 20 n. 14 (1975).

23

Mobile and Shreveport!5 are the first instances in

which Zimmer has been applied to strike down the

vital legislative choice of a city’s form of government.

Here, the District Court’s wooden application of the

factors enumerated in Zimmer led it to a result untrue

both to the holding of Zimmer and to the teachings of

the Supreme Court in Whitcomb and White. The Con-

stitution, and still less Zimmer,

“does not require that a uniform straitjacket bind

citizens in devising mechanisms of local govern-

ment suitable for local needs and efficient in solv-

ing local problems.” Avery v. Midland County, 390

U.S. 474, 485 (1968).

B. Racially Discriminatory Purpose Is An Es-

sential Element Of Equal Protection Viola-

tion Which Plaintiffs Failed To Prove.

Claims like those of Plaintiffs below that at-large

electoral systems ‘are being used invidiously to

cancel outor minimize the voting strength of minority

groups’ are actions for relief under the Equal Protec-

tion Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. White,

supra, 412 U.S. at 765. Although at-large elections

have the potential for submergence of minority in-

terests, they are not unconstitutional per se. Whit-

comb, supra, 403 U.S. at 159-160. Even where at-large

elections in fact “diminish to some extent” black

voting power, such racially disproportionate impact

does not by itself constitute an unconstitutional denial

of access to the political process. Bradas v. Rapides

Parish Police Jury, supra, 508 F.2d at 1113; McGill v.

Gadsden County Commission, supra, 535 F.2d at 281.

15 Blacks United for Lasting Leadership, Inc. v. City of

Shreveport, 71 F.R.D. 623 (W.D. La. 1976), appeal pending, No. 76-

3619 5th Cir.

24

“Where racial intent is not shown, blacks are not suf-

fering because they are black,” but simply because

they, like many other interest groups, constitute a

minority of voters. Carpeneti, Legislative Apportion-

ment: Multimember Districts and Fair Representa-

tion, 120 U.Pa.L.Rev. 666, 698 (1972); see Whitcomb,

supra, at 154-155.

At-large electoral systems are not, therefore,

rendered unconstitutional simply because they may

make it more difficult for a black minority to elect

black representatives. “Under the Fourteenth Amend-

ment the question is whether the [electoral] plan

represents purposeful discrimination ....” United

Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey,

a ULB a d5 U.S. LW, 4991. 4931 (U.S. 3/1/77)

(Stewart, J., concurring), citing Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229 (1976).16 In Davis, the Supreme Court

“made it clear that official action will not be held un-

constitutional solely because it results in a racially

disproportionate impact. * * * Proof of racially dis-

criminatory intent or purpose is required to show a

violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” Village of

Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing

Development Corp.; ——-U.8S......97 8, Ct. 555, 583

(1977).

16 In United Jewish Organizations, the Court upheld a New York

legislative districting plan in which the State had “deliberately

used race in a purposeful manner” to comply with §5 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973c. 45 U.S.L.W. at 4227. Though the plan

disadvantaged a white community of Hasidic Jews, the Court

found no evidence of invidiously discriminatory intent with

respect to “whites or any other race.” Id., see also 45 U.S.L.W. at

4231 (Stewart, J., concurring).

25

While Davis involved the validity of a test used to

screen applicants for public employment, the decision

clearly demonstrates that proof of invidious intent or

purpose is a universal requirement for success of any

action challenging facially neutral official action. The

Davis Courtexpressly disapproved along list of cases

which had “rested on or expressed the view that proof

of discriminatory racial purpose is unnecessary in

making out an equal protection violation...” 426 U.S.

at 244 n.12. The cases disapproved dealt not only with

public employment, but extended to other contexts in-

cluding urban renewal, zoning, public housing, and

municipal services.”

Following Davis, the Court in Arlington Heights

upheld a local zoning decision which precluded

building of a low-cost housing development despite

the discriminatory “ultimate effect” of the zoning. The

Seventh Circuit had found the Village to be “ex-

ploiting” the existing high degree of residential

segregation, and had ruled that the zoning decision

was unsupported by any compelling interest suf-

ficient to justify its discriminatory effects. 97 S.Ct. at

560. The Supreme Court reversed, because failure to

prove that discriminatory purpose was a motivating

factor in the Village’s decision “ends the con-

stitutional inquiry.” Id. at 566. That the ultimate effect

of the decision was “discriminatory” was “without in-

dependent constitutional significance.” Id.

As the Court noted in Arlington Heights,

“the holding in Davis reaffirmed a principle well es-

17 Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, 437 F.2d 1286 (5th Cir. 1971), af-

firmed on rehearing en banc, 461 F.2d 1171 (1972).

26

tablished in a variety of contexts. E.g., Keyes v.

School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 208 (1973)

(schools); Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52, 56-57

(1964) (election districting); Akins v. Texas, 325 U.S.

398, 403-404 (1945) (jury selection).” 97 S.Ct. at 563.

That this principle is not limited to these contexts is

further emphasized by the action of the Supreme

Court in vacating United States v. Board of School

Commissioners of Indianapolis, 541 F.2d 1211 (7th Cir.

1976), in light of Davis and Arlington Heights. 45

U.S.L.W. 3508 (U.S. Jan. 25, 1977). A consolidated,

county-wide government called Uni-Gov had replaced

the separate municipal government of Indianapolis

and other governmental units in Marion County, In-

diana. 541 F.2d at 1212. The Indianapolis cases in-

volved the effects of Uni-Gov upon segregation in

schools and public housing, and the underlying issue

of black voting rights vis a vis school boards which

had not been consolidated within Uni-Gov.18

The Seventh Circuit found that Uni-Gov was “a

neutral piece of legislation on its face with its main

purpose to efficiently restructure civil government”

but that its failure to consolidate education along with

other public functions produced a substantial

segregative impact. 541 F.2d at 1220. Failing to find the

compelling state interest it thought required in the

face of racially disproportionate impact, the Court

concluded that an interdistrict remedy ignoring Uni-

Gov’s school boundaries was appropriate. The dissent

18 That form of government and electoral issues were present is

clear from the fact that Uni-Gov would have required clearance

under §5 of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973c, if Indiana were

subject to the Act. See City of Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S.

358 (1975) (annexation).

27

noted that discriminatory purpose, an “essential ele-

ment of any equal protection violation,” was missing.

541 F.2d at 1225 (Tone, J.). The recent action of the

Supreme Court proves the dissent correct. 45 U.S.L.W.

at 3508.

1. In no case has this Court invalidated an

electoral system of such long standing as

Mobile’s without a showing of dis-

criminatory purpose — the Zimmer line

of cases is fully consistent with Supreme

Court decisions requiring that purpose

be shown.

The holdings of this Court have uniformly com-

ported with this rule that racially discriminatory pur-

pose is essential to proof that facially neutral state ac-

tion violates the Equal Protection Clause. Zimmer in-

volved a recent change in electoral system which, as

in Turner, appeared to have been “conceived as a tool

of racial discrimination.” Wallace v. House, supra, 515

F.2d at 633. In Zimmer,

“a long-standing policy of single-member district

voting was changed to an at-large system, clearly in

response to increased black voting strength in the

1960’s.” Wilson v. Vahue, 403 F. Supp. 58, 66 (N.D.

Tex., 1975).

Indeed, it is clear in Zimmer that the local governmen-

tal interest was ‘“‘tenuous’ primarily because it was

“rooted in racial discrimination.” 485 F.2d 1305-06.

In Turner, this Court dealt with restructuring an

electoral system which had been stipulated un-

constitutional for one-man, one-vote deviations as

great as 37%. 490 F.2d at 192 n.3. Under that mixed

single, multi-member system, ‘“[n]ot surprisingly,

28

both of the major concentrations of black population

were formerly enveloped in multi-member districts.”

490 F.2d at 195 n.19. Black voters had long been fenced

out of the candidate slating process by the locally

dominant political party, an “old weapon in the

arsenal of [purposeful] voter discrimination . ..” 490

F.2d at 195. The Police Jury offered no “persuasive

justification” whatsoever for its proposed multi-

member plan, which would have clearly perpetuated

the exclusion of blacks already accomplished under

its old electoral scheme. 490 F.2d at 196 n.23.

By way of contrast, in Bradas v. Rapides Parish

Police Jury, this Court vacated a judgment striking

down a mixed single, multi-member districting plan

under which no black officer had ever been elected to

the 18-member police jury despite a 28% black popula-

tion. 508 F.2d at 1110-11. Plaintiffs there had failed to

meet their burden of proof under Zimmer in several

respects, among them failure to show governmental

policy “rooted in racial discrimination.” Id. at 1112.

Although the combination of two key wards into a

multi-member district electing 10 of the 18 officers had

“diminished to some extent” black voting power, this

Court concluded that the evidence failed to

demonstrate that this districting plan was ‘“’conceived

or operated as [a] purposeful device[] to further racial

or economic discrimination.’ ”’ Id. at 1113, citing Whit-

comb, supra, 403 U.S. at 149.

And in McGill v. Gadsden County Commission, this

Court dealt with an all at-large electoral system serv-

ing a Florida county with registered voting popula-

tion almost 50% black. 535 F.2d at 278. Yet no blacks

29

had ever been elected, even though they had “run

regularly since the middle 1960’s.” Id. at 280. Present

there was a strong state policy favoring at-large elec-

tions, in effect since 1900, a policy which

“could not have had racist underpinnings because

other, less subtle state mechanisms had already dis-

enfranchised almost all black voters by the turn of

the century.” Id. at 281.

Nor was the maintenance of this policy apparently

tainted by the “extensive” subsequent history of

racial discrimination in the county. In the absence of

“tenuous” state policy and other Zimmer factors in-

cluding proof that such past discrimination presently

precluded blacks from the political process, this Court

affirmed judgment upholding the at-large electoral

system. Id.

In sum, the recent decisions of this Court clearly

show the necessary sensitivity to racially invidious

purpose as an essential element of its Equal Protec-

tion analysis consistent with the constitutional prin-

ciples recently reaffirmed in Washington v. Davis.

Whether such purpose or intent be found in a

“tenuous” governmental policy rooted in racial dis-

crimination, in a candidate-slating process from

which blacks are fenced out by white-dominated

slating organization, or in one or more of the generic

factors set forth in Arlington Heights,!® this Court

19 The Supreme Court there identified several possible sources

of evidence for the proof of racial purpose: (1) disproportionate im-

pact so “stark” as to be “unexplainable on grounds other than

race’; (2) general historical background of the action; (3) specific

events antecedent to the action; (4) departures from normal

procedures; and (5) contemporary statements of decisionmakers.

97 S.Ct. at 564-565. See United Jewish Organizations, supra, 45

U.S.L.W. at 4231 (Stewart, J. concurring).

30

must continue to treat such “dilution” cases as this

like any Equal Protection challenge to facially neutral

governmental action.

2. The District Court erred in reading the

element of racial purpose out of Zimmer.

The District Court erroneously viewed the Equal

Protection requirement of invidious racial purpose

recently reaffirmed in Washington v. Davis, supra, as

a “threshold question” which would “preclude an

application of the factors determinative of voter dilu-

tion as set forth in White, supra, and Zimmer. . .” (423

F. Supp. at 394). Primarily because of the “factual con-

text” of Davis, the District Court concluded that Davis

“did not overrule” earlier “dilution” cases or establish

a “new” purpose test. (423 F. Supp. at 398). Thus, the

Court thought, Davis simply did not apply in Equal

Protection contexts other than those cited in that deci-

sion.

Indeed, Davis did not establish a “new” test, but

merely ‘reaffirmed a principle well established”

wherever facially neutral government actions are

challenged under Equal Protection for their dis-

proportionate racial impact. Arlington Heights,

supra, 97 S.Ct. at 563. Nor does Davis overrule cases

like White and Zimmer and “preclude” the sensitive

factual analysis these cases require. Quite to the con-

trary, it is precisely such a “sensitive inquiry into

such circumstantial and direct evidence of intent” that

proper application of the Zimmer factors requires. Id.

at 564. But unless a Court’s evaluation of these factors

leads it to the conclusion that invidious racial purpose

31

or intent has been proved, the case remains one sole-

ly of racially disproportionate impact, which under

Davis may not be the “sole touchstone” of an Equal

Protection violation. Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 242.

The District Court erroneously regarded “dilution”

cases like this one as a genus apart from other voting

cases like Wright v. Rockefeller, 376 U.S. 52 (1964) and

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960), both cited

with approval in Arlington Heights, supra, 97 S.Ct. at

563-64. (See 423 F.Supp. at 395). But the principles of

White and Zimmer are equally applicable to such

cases involving alleged racial gerrymandering and

redistricting problems in general. Paige v. Gray, 538

F.2d 1108, 1110 (5th Cir. 1976); see United Jewish

Organizations, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4231 (Stewart, J.,

concurring). Gomaillion, for example, is simply a case

where the “stark” pattern, “unexplainable on grounds

other than race,” makes the evidentiary inquiry into

racial purpose “relatively easy.” Arlington Heights,

supra, 97 S.Ct. at 564.

There can be no meaningful distinction for Equal

Protection purposes between challenges to district-

ing and challenges to at-large electoral systems

which by definition do not district at all. The District

Court erred in holding that the teachings of Davis did

not here require proof of racial purpose, and in

reading this elementout of Zimmer and other holdings

of this Court.

C. The City Government Of Mobile In Fact Fully

Satisfies The Zimmer Test — Its Electoral

Process Is Equally Open To Blacks and

Whites.

32

The ultimate question under Zimmer is whether

Mobile’s Commission Government operates in-

‘vidiously to deny black Mobilians access to the City’s

political process. In White v. Regester, the Supreme

Court sustained such a claim for the first time, upon

findings that Texas’ electoral system “effectively ex-

cluded” Dallas County blacks and “effectively remov-

ed” Bexar County Mexican-Americans from the

political process. Thus, “access to the political

process’ is the “barometer of dilution of minority

voting strength.” Zimmer, supra, 485 F.2d at 1303.

In Zimmer, this Court drew upon the teachings of

Whitcomb and White to set forth a “panoply of factors”

upon which proof of such denial of access may be

founded. Primary factors entail proof of

“[1] a lack of access to the process of slating can-

didates, [2] the unresponsiveness of legislators to

their particularized interests, [3] a tenuous state

policy underlying the preference for multi-member

or at-large districting, or [4] that the existence of

past discrimination in general precludes the effec-

tive participation in the election system ...” 485

F.2d at 1305 (footnote omitted).

Such proof may be “enhanced” by the showing of

“[1] the existence of large districts, [2] majority vote

requirements, [3] anti-single shot voting provisions

and [4] the lack of provision for at-large candidates

running from particular geographical sub-

districts.” Id.

33

Conversely, Whitcomb v. Chavis requires judgment

upholding an electoral system

“[w]here it is apparent that a minority is afforded

the opportunity to participate in the slating of can-

didates to represent its area, that the represen-

tatives slated and elected provide representation

responsive to the minority’s needs, and that the use

of a multi-member districting scheme is rooted in a

strong state policy divorced from the maintenance

of racial discrimination ...” Zimmer, 485 F.2d at

1305.

As the following analysis shows, the District Court

erred in its application of the Zimmer factors to the

particular facts of this case. The form of government

and attendant electoral system under which the City of

Mobile has functioned for over 65 years clearly must

be upheld under this Court’s reading of Whitcomb.

1. The Constitution neither creates nor

protects any right to proportional

representation in any racial, ethnic or

other interest group.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly “rejected the

proposition that members of a minority group have a

federal right to be represented in legislative bodies in

proportion to their number in the general population.”

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130, 136 n.8 (1976), citing

Whitcomb.?0 As a consequence, no minority group is

20 In United Jewish Organizations, supra, three members of the

Court joined in the view that, even absent the statutory mandate of

the Voting Rights Act, a State under certain circumstances might

constitutionally decide to switch from multi-member to single-

34

“entitled to an apportionment structure designed to

maximize its political advantage,” Turner, supra, 490

F.2d at 197, or to an electoral system ‘“‘so arranged that

[minority] voters elect at least some candidates of

their choice. . .” even where voting is racially polariz-

ed. Nevett v. Sides, supra, 533 F.2d at 1365. Accord,

United Jewish Organizations, supra, 45 U.S.L.W. at

4227. The courts have implicitly rejected the proposi-

tion that “a white official represents his race and not

the electorate as a whole and cannot represent black

citizens.” Vollin v. Kimbel, 519 F.2d 790, 791 (4th Cir.

1975) (emphasis original), citing Dallas County v.

Reese, 421 U.S. 477 (1975) and Dusch v. Davis, 387 U.S.

112 (1967).

Thus, it is clearly “not enough to prove a mere dis-

parity between the number of minority residents and

the number of minority representatives.” Zimmer,

supra, 485 F.2d at 1305. As in Graves v. Barnes, 343

F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex. 1972), affirmed sub nom. White

v. Regester, supra, plaintiffs must prove that

“the multi-member districts could not be tolerated,

for they operated to exclude substantial racial

minorities not only from political victory but even

from political consideration.” Wallace v. House,

supra, 515 F.2d at 629.

In its desire to “provide blacks a realistic opportuni-

ty to elect blacks” (423 F. Supp. at 403) the District

member districting in order to afford minorities an opportunity to

achieve roughly proportional representation. 45 U.S.L.W. at 4227.

They do not, however, suggest that such an electoral change would

be required by the Constitution, even where racial bloc voting

makes it “unlikely that any candidate will be elected who is a

member of the race that is in the minority in that district.” Id.

35

Court disestablished Mobile's form of government on

a claim no more substantial than Whitcomb’s “mere

euphemism for defeat at the polls.” 403 U.S. at 153.

2. Therebeing no barrierto black participa-

tion in Mobile political life, the District

Court erred in equating black

“discouragement” with denial of access.

Access to the process of slating candidates, which

may be “the most important stage of the political

process,” is a primary factor for analysis under