Reno v Bossier Parish School Board Reply Brief Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1996

25 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Reno v Bossier Parish School Board Reply Brief Appellants, 1996. e106310d-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2394bf9f-cf44-4542-932e-7f6b889519b8/reno-v-bossier-parish-school-board-reply-brief-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

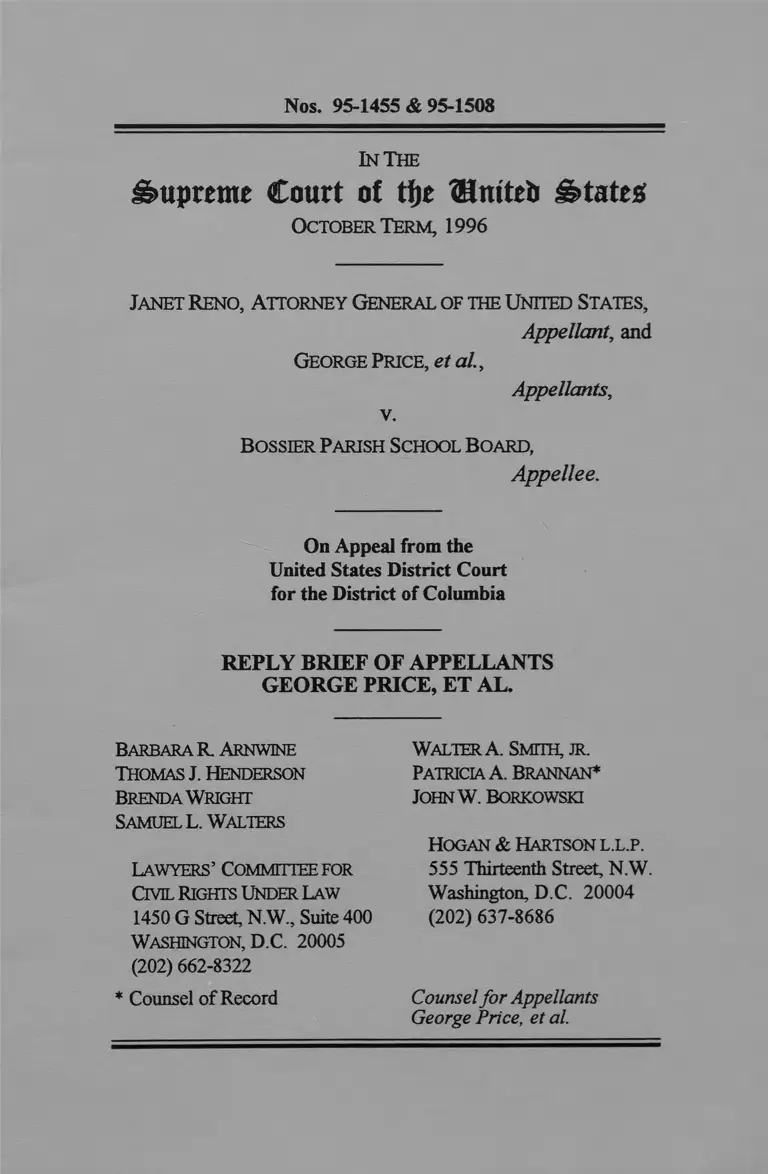

Nos. 95-1455 & 95-1508

In The

Supreme Court of tfje United states

October Term, 1996

Janet Ren o , Attorney General of the United States,

Appellant, and

George Price, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

B o ssier Parish School B oard ,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the

United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

REPLY BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

GEORGE PRICE, ET AL.

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Brenda Wright

Samuel L. Walters

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights under Law

1450 G Street, N.W , Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8322

* Counsel of Record

Walter A. Smith, jr.

Patricia A. Brannan*

John W. Borkowsh

Hogan & Hartson l.l.p .

555 Thirteenth Street, NW .

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 637-8686

Counsel fo r Appellants

George Price, et al.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

INTRODUCTION.................................................................. 1

ARGUMENT.......................................................................... 3

l. THE PURPOSE PRONG OF

SECTION 5 IS DETERMINATIVE IN

THIS CASE .............................................................. 3

n . BOSSIER HAS CONCEDED THE

LEGAL STANDARDS THAT

GOVERN THE SECTION 5 PURPOSE

PRONG...................................................................... 4

m. THE MAJORITY BELOW PLAINLY

DID NOT APPLY THE GOVERNING

STANDARDS........................................................... 5

IV. BECAUSE UNDER THE

GOVERNING STANDARDS THE

RECORD LEAVES NO DOUBT

THAT DISCRIMINATORY PURPOSE

MOTIVATED THE BOARD’S

ACTION, THIS COURT SHOULD

REVERSE.................................................................. 8

A. The Board Presented No Evidence of

Any Non-Racial Reason to Reverse

Itself and Adopt the Police Jury Plan................. 8

B. Board Members Admitted Bossier’s

Discriminatory Purpose...................................... 11

l

11

C. The Board’s Otherwise Unexplained

Retreat to the Police Jury Plan

Dilutes Minority Voting Strength...................... 12

D. The School Board’s Ongoing

History of Discrimination Shows

How and Why It Sought to Dilute

Minority Voting Strength Through

the Police Jury Plan........... ................................ 13

E. The Board’s Plan Fails to Satisfy Its

Own Redistricting Criteria................................. 15

F. The Board’s Alleged Concerns

About the Illustrative Plans Are

Purely Pretextual and Underscore Its

Actual Discriminatory Purpose................ 17

TABLE OF CONTENTS— Continued

Page

CONCLUSION 20

Ill

CASES:

Bush v. Vera, 116 S. Ct. 1941 (1996).......................... 15

City o f Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808

(1985)............... .......................................................... 6

Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467 (1992)........................ 14

Levin v. M ississippi River Fuel Corp., 386 U S

162 (1967)................................................................... g

Lucas v. South Carolina Coastal Council, 112

S. Ct. 2886 (1992)...................................................... 6

M iller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct. 2475 (1995)..................5,10,15

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)........................ 15

Shaw v. Hunt, 116 S. Ct. 1894 (1996)......................... 10,15

United States v. El Paso Natural Gas Co., 376 U S

651 (1964)............ g

Village o f Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Dev. Corp., 426 U.S. 252 (1977) ............. passim

STATUTES:

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act,

42 U.S.C. § 1973..........................................................passim

Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act,

42 U.S.C. § 1973c

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

passim

In The

Supreme Court of tfje ©niteb States

October Term, 1996

Nos. 95-1455 & 95-1508

Janet Reno, Attorney General of the United States,

Appellant, and

George Price, et al.,

v.

Appellants,

Bossier Parish School Board,

Appellee.

On Appeal from the

United States District Court

for the District of Columbia

REPLY BRIEF OF APPELLANTS

GEORGE PRICE, ET AL.

INTRODUCTION

In its brief to this Court, the Bossier Parish School

Board now concedes that: (1) Village o f Arlington

Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Development Corp.,

426 U.S. 252 (1977), sets the legal standard for

determining whether the Board adopted the Police Jury

plan in part for a discriminatory purpose, B.P. Br. 29,

33, 36, 49;1 (2) if the plan was adopted in part for a

1 In this brief, record citations conform to the abbreviations set

forth in the Brief of Appellants George Price, et al., at 1 n.l (filed

2

discriminatory purpose, it violates Section 5 even though

it may be nonretrogressive, id. at 10; and (3) in

determining whether die plan was adopted in part for a

discriminatory purpose, it would be “indefensible” for a

court to ignore relevant evidence merely because that

evidence would also be relevant to a Section 2 claim, id.

at 31. Even though Bossier thereby acknowledges that

appellants are right on the law with respect to the

standards governing the “purpose” prong of Section 5, it

does not and cannot show that it meets those standards.

Instead, in its effort to defend the lower court’s

judgment, Bossier mischaracterizes the central issues

before this Court, misstates the ruling of the majority

below, and misrepresents the stipulated and unrebutted

facts in the record.

For example, Bossier repeatedly mischaracterizes this

case as one raising the question whether a governmental

body unlawfully discriminates solely because it fails to

maximize the number of majority-minority election dis

tricts. See, e.g., B.P. Br. 6. In fact, the question is whe

ther the Board adopted its plan in part to minimize the

number of majority-minority districts and keep it at zero.

Likewise, this case does not ask this Court to choose

between Bossier’s plan and what it calls an “objectively

inferior” maximizing alternative. Id. Instead, this case

concerns the Board’s refusal to consider any possible

plan with even a single majority-minority district and its

sudden adoption of a previously rejected and seriously

flawed m inim izing plan only when it was publicly

confronted with the fact that majority-minority districts

were a viable option.

August 1, 1996). Additional abbreviations are as follows: Brief of

Appellee Bossier Parish (“B.P. Br.”); Brief of Appellants George

Price, et al. (“D-I Br.”); and Jurisdictional Statement of Appellants

George Price, et al. (“D-I J.S.”).

3

In the end, the central question in this case is whether

the Board met its burden to prove that its hasty reversal

about the Police Jury plan was not motivated even in

part by a discriminatory purpose. Applying the

Arlington Heights standard—which all parties now

acknowledge as controlling—to the stipulated and

unrebutted facts, Section 5 preclearance should be

denied because this “evidence demonstrates conclusively

that the Bossier School Board acted with discriminatory

purpose.” App. 39a (Kessler, J., dissenting). Therefore,

this Court should correct the majority’s legal errors and

reverse the decision below.

ARGUMENT

I. THE PURPOSE PRONG OF SECTION 5 IS

DETERMINATIVE IN THIS CASE

Notwithstanding that Bossier spends the bulk of its

brief arguing that a Section 2 violation should not be

grounds for denying Section 5 preclearance, B.P. Br. 8-

27, this Court need not reach that issue. This case has

always been primarily a Section 5 discriminatory pur

pose case. The analysis of discriminatory purpose under

Arlington Heights was the primary focus of all the

briefing below. Indeed, the purpose evidence was so

overwhelming that it was the only issue addressed in the

Defendant-Intervenors’ Post-Triad Brief.

All the parties agreed below, moreover, both that the

court need not address Section 2 if Bossier “failed to

meet its burden of proof on the issue of purpose” and, on

the other hand, that it would make no sense to preclear a

redistricting plan that violates Section 2. App. 144a

(Stip. 257). We continue to support this position. See

D-I Br. 43-45.

This Court, however, need not reach the Section 2

incorporation issue because the majority below failed to

apply the proper legal standard to the evidence that

4

“demonstrates overwhelmingly” the Board’s discrimina

tory purpose. App. 63a (Kessler, J., dissenting). Thus,

if the Court agrees with us on the Section 5 purpose

issue, the subsidiary Section 2 issue need not be decided.

On the other hand, even if the Court decided the

Section 2 incorporation issue against us, the discrimin

atory purpose issue would still have to be reached.

Furthermore, and contrary to Bossier’s repeated con

tentions, addressing the purpose issue under Arlington

Heights will not require this Court “indirectly” to decide

the incorporation issue. B.P. Br. 6-7, 30-31. The

overwhelming evidence of discriminatory purpose in this

case does not hinge on the presence of a Section 2

violation or the Board’s “failure to maximize.” Id. at 7.

Instead, the evidence here—including direct admis

sions of discriminatory purpose, a discriminatory impact

on minority voters, an ongoing history of discrimination,

a failure to comply with stated redistricting criteria, and

plainly pretextual post hoc rationalizations—unequivo

cally reveals that the Board adopted a previously

debunking of its earlier claim that a majority-black

district was impossible. Since Bossier adopted its plan

in part for a discriminatory purpose, it should be denied

preclearance, and the Board should be directed to

develop a new plan free of such influences.

n . BOSSIER HAS CONCEDED THE LEGAL

STANDARDS THAT GOVERN THE SECTION 5

PURPOSE PRONG

In its motion to dismiss this appeal, Bossier admitted

that the majority below failed to apply Arlington Heights

to the stipulated and unrebutted facts; Bossier argued

then drat a different legal standard should apply. Motion

to Dismiss or Affirm at 11-12. Now, Bossier agrees that

Arlington Heights applies. B.P. Br. 29, 33, 36, 49.

5

Indeed, our Jurisdictional Statement raised four

questions regarding the legal standards applicable to the

purpose prong of Section 5, D-I J.S. i., and Bossier now

appears to agree with our position on all four. First,

Bossier now expressly “agree[s] that courts - in Section

5 proceedings . . . should not exclude evidence probative

of the legal question being resolved simply because it is

also relevant to another legal issue.” B.P. Br. 28. In

fact, Bossier concedes that it is an “indefensible ruling

that otherwise material evidence of purpose somehow

should be excluded because it was also relevant to

Section 2.” Id at 31. Second, Bossier acknowledges

that this Court’s decisions “in just the past two Terms”

have confirmed that Section 5 preclearance must be

denied even to an ameliorative plan, and certainly to a

minimizing plan, if it is adopted with “an invidious

purpose.” Id. at 10 (citing Miller v. Johnson, 115 S. Ct.

2475 (1995)). Third, Bossier agrees that it bears the

burden of proof under Section 5, id. at 8-9, implicitly

acknowledging that the court itself should not provide its

own arguments to meet that burden. Finally, in

accepting Arlington Heights as the governing legal

standard, Bossier also apparently acknowledges that if a

discriminatory purpose was “a motivating factor” in its

decision, preclearance should be denied. Id. at 29, 33,

36, 49; Arlington Heights, 465 U.S. at 265-66.

MI. THE M AJORITY BELOW PLAINLY DID NOT

APPLY THE GOVERNING STANDARDS

At the outset, we urge the Court to consider that in its

motion to dismiss the Board agreed that the majority

both refused to apply Arlington Heights and excluded

from consideration all evidence relevant to Section 2.

Motion to Dismiss or Affirm at i, 11-12. Now, however,

Bossier has reversed course completely and contends

that the majority did apply Arlington Heights and did

consider certain Section 2 evidence, excluding only

Section 2 evidence that would not be relevant to discrim

inatory purpose under Section 5. B.P. Br. 8, 27-39. A

6

party is not permitted to contradict itself in this fashion

and raise for the first time in its responsive brief on the

merits an argument it could have made in opposition to

certiorari or in a motion to dismiss. See Lucas v. South

Carolina Coastal Council, 112 S. Ct. 2886, 2897 n.9

(1992); City o f Oklahoma City v. Tuttle, 471 U.S. 808,

815-16 (1985). Accordingly, the Court should not

consider Bossier’s new argument.

In any case, the argument is plainly without merit. To

sustain its new view that the majority correctly applied

Arlington Heights and considered all the relevant evi

dence, Bossier ignores both what the majority says it did

as well as what it actually did. Relying now on a soli

tary footnote, Bossier claims that the majority’s failure

to apply Arlington Heights and its exclusion of “Section

2 evidence” were harmless, because it excluded from

consideration solely that “evidence relevant only to the

section 2 inquiry.” B.P. Br. 27 (quoting App. 9a n.6)

(emphasis added). Bossier, however, can cite no

evidence introduced by appellants that is irrelevant to

discriminatory purpose under Arlington Heights. There

fore, this footnote cannot save the majority’s decision.

The text of the majority’s opinion also makes clear that

the majority considered any evidence that was relevant

to Section 2 to be irrelevant to Section 5. In each of the

three references in the text of the majority’s opinion to

its refusal to consider “section 2 evidence,” the majority

does not limit its discussion to evidence relevant “only”

to Section 2. See D-I Br. 29 n.6 (quoting App. 23a-24a).

Rather, the majority plainly and repeatedly explains that

this evidence’s relevance to Section 2 is the reason that

it should not be considered in a Section 5 proceeding.

App. 23a-24a. That is why the footnote relied on by

Bossier must be read to mean that such evidence would

not be considered under Section 5 because, in the

majority’s view, by definition it was “relevant only to

the section 2 inquiry.” Id. at 9a n.6. Moreover, when

7

Judge Kessler in dissent pointed out both the proper

legal standard and the majority’s refusal to apply it,

App. 39a n.2, 42a n.4, the majority did not profess that it

really was weighing all the evidence.

This reading of the majority’s opinion is confirmed by

what the majority actually did in excluding certain

relevant evidence. It is also confirmed by Bossier’s own

laborious effort to demonstrate that the impact on minor

ity voters of the Board’s plan and Bossier’s ongoing

history of discrimination are insignificant in this case.

B.P. Br. 3-5, 27-39. The majority’s opinion, of course,

says none of this, because the majority never considered

such evidence.

For example, without citation to the majority’s actual

opinion, Bossier claims that “[t]he court assumed” that

its plan negatively affected black voters’ electoral

opportunities but found that the Board adopted the plan

‘in spite o f’ that impact. Id. at 33. The majority did not

say this and made no such assumption; not a sentence of

the majority’s opinion addresses the discriminatory

impact of the Board’s plan.

Bossier also suggests that the majority considered the

Board’s ongoing history of discrimination, but con

cluded that it was not particularly probative. B.P. Br.

36-38. Bossier again rests its claim principally on a sin

gle footnote taken out of context. Id. at 37 (citing App.

34a n.18). Even in this footnote, however, the majority

stated that it did not “see how [Bossier’s continu ing

willful failure to comply with school desegregation or

ders] can be in any way related to the School Board’s

purpose in adopting the Police Jury plan.” App. 34a

n.18. In contrast, Bossier itself now concedes that “‘a

series of official actions taken for invidious purposes’”

is relevant to the question “whether this specific voting

change was motivated by the same invidious purposes.”

B.P. Br. 36 (quoting Arlington Heights, 429 U.S. at

267). Moreover, the rest of the voluminous evidence of

8

discrimination in Bossier Parish and by the Board itself

is never even mentioned by the majority. App. 42a n.4.

(Kessler, J., dissenting).

In sum, it is implausible to conclude, as Bossier urges,

that the majority silently applied Arlington Heights and

actually considered the crucial “Section 2” evidence that

it said it did not. Accordingly, the majority’s resulting

judgment is erroneous as a matter of law and should be

set aside.

IV. BECAUSE UNDER THE GOVERNING

STANDARDS THE RECORD LEAVES NO

DOUBT THAT DISCRIMINATORY PURPOSE

MOTIVATED THE BOARD’S ACTION, THIS

COURT SHOULD REVERSE

Bossier’s contention that this appeal is actually a

“straightforward ‘clearly erroneous’ case,” B.P. Br. 28,

39, is itself erroneous. The principal facts relevant to

determining discriminatory purpose are not in dispute;

they are stipulated and unrebutted. App. 66a-153a (Stip.

1-285); D-I Br. 5-23. The actual dispute here centers on

the majority’s legal errors in analyzing, and refusing to

consider, the stipulated facts. Moreover, when analyzed

under the governing legal standards, the actual facts of

record permit only one conclusion: “racial purpose

fueled the School Board’s decision.” App. 39a (Kessler,

J., dissenting). For that reason, this Court should not

merely vacate the majority’s opinion; it should reverse

and direct that preclearance be denied. See United

States v. El Paso Natural Gas Co., 376 U.S. 651, 657

(1964); Levin v. Mississippi River Fuel Corp., 386 U.S.

162, 169-70 (1967).

A. The Board Presented No Evidence of Any Non-

Racial Reason to Reverse Itself and Adopt the

Police Jury Plan

Throughout its brief, Bossier mischaracterizes the

issue in this case as whether the Board had any legiti

9

mate reason for rejecting the NAACP plan; the real

issue, however, is whether the Board had any

discriminatory purpose in adopting the plan it did adopt

See D-I Br. 38-40.

The Board initially rejected the Police Jury plan on

September 5, 1991. App. 47a (Kessler, J., dissenting).

As the majority found:

The School Board did not like the Police Jury

plan when it was first presented to them [after it

already had been precleared on July 29, 1991, App.

58a], and there were certainly reasons not to. The

Police Jury plan wreaked havoc with the incumben

cies of four of the School Board members and was

not drawn with school locations in mind. [App. 28a.]

The ultimate question, therefore, is why did the Board

reverse its decision, and more specifically, did a

discriminatory purpose contribute to that reversal?

Bossier asks this Court to assume that the two reasons

it adopted the Police Jury plan were those relied on by

the majority: “guaranteed preclearance” and “precinct

splitting.” B.P. Br. 6 (quoting App. 27a-28a). But

Bossier offered no evidence that those reasons actually

motivated its reversal of position on the plan. Nor is this

surprising. Preclearance certainly was no more likely in

1992 than it had been in 1991 when the Board rejected

the Police Jury plan. And, concerns about precinct-

splitting are not a reason to adopt the Police Jury plan at

all but, at most, a reason—albeit pretextual (see infra

pp. 18-20)— to reject the NAACP plan.

Turning to the actual evidence of record, the Board

offered no real explanation for its adoption of the Police

Jury plan. The Board’s minutes reveal no discussion at

all of the merits of the plan or the reasons for adopting

it, App. 55a n .l l (Kessler, J., dissenting); U.S. Exh. 7-

36, and the majority found that at the Board’s public

hearing “[n]o one spoke in support of the plan.” App.

10

8a. It also is undisputed that although the Board

considered a number of different redistricting options,

id. at 5a, it did not present a scintilla of evidence about

its admittedly closed-door efforts to develop another

plan. App. 47a (Kessler, J., dissenting); App. 97a (Stip.

96). Instead, the Board claimed that all of the other

alternatives were inadvertently destroyed in a series of

computer mishaps. J.A. 165-66.

This case, therefore, is unlike either Miller, in which

“Georgia’s Attorney General provided a detailed explan

ation for the State’s initial decision” to adopt an ameli

orative plan, 115 S. Ct. at 2492, or Shaw v. Hunt, 116

S. Ct. 1894 (1996) (“Shaw I I ”), in which North Carolina

initially adopted an ameliorative plan after rejecting a

number of other options for legitimate reasons. Id. at

1904. In contrast, Bossier presented no evidence of any

race-neutral reason why its efforts to develop alternative

plans were abruptly abandoned in favor of a previously

rejected minimizing plan. Here, the record shows only

that the Board resurrected the Police Jury plan in direct

response to the public demonstration that it was possible

to draw majority-black districts. App. 28a, 6a; App.

46a-50a (Kessler, J., dissenting); D-I Br. 14-21.

Bossier now tries to deflect attention from its

unexplained reversal by contending that the issue is

whether the Board was required to adopt the NAACP

plan. B.P. Br. 40. No one has ever so claimed. App.

60a (Kessler, J., dissenting). Instead, as the majority

found, the Board was asked to “consider alternative

redistricting plans” App. 8a (emphasis added). Black

voters specifically asked the Board only to use the

NAACP plan “as a foundation” to develop a redistricting

plan. App. 101a (Stip. 108). Indeed, George Price

initially submitted to the Board only the basic

demographic information showing that two majority-

black districts could be drawn. App. 6a. The Board

itself demanded that Price develop a full plan. Id. In the

11

end, therefore, the Board presented no evidence demon

strating a non-discriminatoiy explanation for its reversal.

B. Board Members Admitted Bossier’s

Discriminatory Purpose

On the other hand, several Board members actually

admitted that the Board’s sudden turnabout with respect

to the Police Jury plan resulted from the fact that “school

board members oppose [the] idea” of “black

representation on the board.” J.A. 93; App. 31a. The

majority below improperly attempted to explain this

evidence away, see D-I Br. 36-38, and Bossier now asks

this Court to accept those explanations. B.P. Br. 50

n.35. The Court should not do so.

The Board member who made the admission quoted

above, Henry Bums, did not testify, and as the majority

noted, the Board did not “cross-examine . . . on this

point.” App. 31a. Thus, the statement stands undis

puted. Another Board member, Barry Musgrove, also

admitted that “other Board members were hostile to

drawing majority-black districts.” Id. at 32a.

Mr. Musgrove did testify, and he did not deny “making

this statement,” as the majority suggests, id , but said

only that he did not “recall” it. Tr. I at 56. Finally,

Board member Thomas Myrick, whose denial of his

involvement in the Police Jury redistricting process the

majority rejected as false, see D-I J.S. 28 n.9; D-I Br.

11-12 n.3, told the Board’s redistricting consultant that

he wanted to avoid the creation of a majority-black

district, J.A. 163-64, and told black voters that he would

not “let [them] take his seat.” App. 6a n.4.

Because these statements are direct evidence of the

Board’s intent, and because Bossier cannot refute them,

it attempts instead to avoid them. Although it made no

objection below, Bossier now implies that all of these

statements are hearsay, B.P. Br. 50 n.35, but, as ad

missions of a party, they are not. Bossier also now

12

claims that the statements were only “allegedly” made,

id., but it presented no evidence below to raise doubt

that they were said. Finally, Bossier claims that these

statements are not probative of discriminatory purpose

without “the most nefarious possible spin,” id , but this

clearly is not so. We ask only that the Court accept

these statements at face value and view them in the

context of the stipulated facts ignored by the majority

below.

C. The Board’s Otherwise Unexplained Retreat to the

Police Jury Plan Dilutes Minority Voting Strength

The majority below erred in refusing to consider the

undisputed evidence that the effect of maintaining

twelve-of-twelve majority-white districts would be to

dilute the ability of minority voters to elect candidates of

their choice. D-I Br. 29-33. Bossier now attempts to

defend this refusal by falsely contending that the Police

Jury plan “enhanced minority voting strength,”

B.P. Br. 40, and that Bossier Parish is not characterized

by racially polarized voting, id. at 3-5. However, the

record unequivocally shows that: (1) when compared to

the Board’s 1980s plan the Police Jury plan actually

reduces the minority voting-age percentage in the three

districts with the highest minority concentrations,

compare J.A. 47 with J.A. 44; and (2) voting in Bossier

Parish plainly is racially polarized.

First, no black candidate had ever been elected to the

Board. App. 67a (Stip. 4). Second, in the four Board

elections since 1980 that involved a contest between a

black and white candidate, the black candidate lost every

time. Id. at 115a (Stip. 153). Third, the only expert

analysis of election statistics for Bossier Parish

concluded that “African American voters are likely to

have a realistic opportunity to elect candidates of their

choice to the . . . Board only in districts in which they

constitute a majority of the voting age population.” J.A.

121. The elections in which Bossier now claims that

13

Dr. Engstrom did not find racial polarization using

regression analysis and extreme-case analysis, B.P. Br.

3-4, are simply elections in which the underlying data

are insufficient to permit a full application of these

statistical techniques. J.A. 111-21. The partial analyses

of these elections that Engstrom was able to perform,

moreover, support the above-quoted conclusion of

racially polarized voting. Id.

Moreover, the majority found that the area surrounding

Barksdale Air Force Base in which a few black candi

dates for other offices in recent times have been success-

fill in elections with white opponents is “unique.” App.

2a n. 1; App. 117a-18a (Stip. 162-63). All but two of the

six elections cited by the Board in which a black candi

date was successful against a white opponent involved

this “unique” community. The other two involved an

at-large election system in Haughton, and because these

elections allowed for single-shot voting the election of

black candidates shows nothing about racial polariza

tion. App. 120a (Stip. 174). Moreover, while Bossier

refers to only 14 black-white contests, 17 actually meet

its arbitrary limiting criteria; the parties stipulated to

facts concerning more than 20 such elections, id. at

115a-27a (Stip. 153-96); and the record includes undis

puted results from more than 30. J.A. 55-60. In all of

these other contests, black candidates lost to whites. Id.

Accordingly, Bossier is wrong to say that Board

elections are not racially polarized, and the majority was

wrong in refusing to consider that polarization in

assessing the Board’s motivation.

D. The School Board’s Ongoing History of

Discrimination Shows How and Why It Sought to

Dilute Minority Voting Strength Through the

Police Jury Plan

With respect to the Board’s history of discrimination,

the “facts” Bossier relies upon again simply cannot be

14

found in this record. While the Board now claims with

out support that unidentified “demographic factors” have

caused increasing segregation in its schools, B.P. Br. 38-

39 n.27, the evidence shows that the Board’s own

actions have contributed to it. Bossier itself submitted

evidence showing that its transfer policy may have con

tributed to the growing racial imbalance in its schools.

PL Exh. 14 at 4. The superintendent also admitted that

the Board intentionally assigned a widely disproportion

ate number of minority teachers to predominantly black

schools. J.A. 179. This is indisputably contrary to the

Board’s court-ordered obligations, App. 45a (Kessler, J.,

dissenting), and is a recognized method of unconstitu

tionally designating some schools as “black” schools and

others as “white.” See Freeman v. Pitts, 503 U.S. 467,

497 (1992). Finally, not only has the Board failed to

achieve a unitary school system, but Board members ad

mittedly were completely ignorant of their court-ordered

desegregation obligations. See, e.g., J.A. 74, 148.

In addition, while Bossier now blames its failure to

maintain the court-mandated bi-racial committee on the

waning “interest of volunteer citizens,” B.P. Br. 38

n.27, there is no evidence to support this; instead, the

record shows that for more than 20 years the Board

reported to the federal court that the actually nonexistent

bi-racial committee was “available.” U.S. Exh. 84YY;

J.A. 134. When the Board finally established a

committee in 1993, Board members quickly terminated

it for the same reason they adopted the Police Jury plan:

they did not want blacks involved in “policy” questions.

D-I Br. 9; App. 104a-06a (Stip. 114-17).

As noted, the majority below failed even to address the

rest of the voluminous stipulated evidence of discrimin

ation in Bossier Parish, and Bossier now seeks to defend

this error by claiming incorrectly that this evidence “says

nothing about why a black majority district was not

created.” B.P. Br. 35. Plainly it does. We do not

15

argue, however, as Bossier suggests, that evidence of

non-Board discrimination in Bossier Parish is relevant

because the Board is responsible for “private citizens’

voting patterns” and all “historical discrimination,” id. at

39. Rather, such evidence is probative because the

Board’s knowledge of the preferences of private citizens

and the patterns of local history—like its awareness of

racially polarized voting—made clear to the Board that

the way to keep black voters out of “policy” questions

was to adopt an election plan with all majority-white

districts. App. 42a-46a (Kessler, J., dissenting). See

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 618, 625 (1982).

E. The Board’s Plan Fails to Satisfy Its Own

Redistricting Criteria

To counter the foregoing showing of discriminatory

purpose, Bossier now relies most heavily on the

proposition that the Police Jury plan could not be

discriminatory because it complies with the Board’s

traditional redistricting principles. See B.P. Br. 6-8, 40-

41, 47-50. Not only is this assertion contradicted by the

stipulated and unrebutted facts, but it also ignores the

governing legal standard.

Bossier argues that this Court has accepted adherence to

a “traditional redistricting principle as a refutation o f any

discriminatory purpose finding.” B.P. Br. 47 (emphasis

added). To the contrary, the Court carefully scrutinized

legislative motives in Miller, Shaw II and Bush v. Vera,

116 S. Ct. 1941 (1996), and, in Vera, explicitly refused to

accept adherence to a traditional redistricting criterion as a

defense even to the allegation that race was the predomi

nant factor in a decision, let alone a contributing factor, id.

at 1951-52. While a showing that traditional redistricting

principles were not subordinated to race may defeat the

“analytically distincf’ claim of racial gerrymandering,

Miller, 115 S. C t at 2488, 2485, this Court has never

suggested that a political body may intentionally dilute

minority voting strength so long as its plan for doing so is

16

compact, contiguous or respects political subdivisions.

Such a perverse rule would subordinate the Constitution to

“traditional redistricting principles.”

Of course, if the Board had shown that the reason it

reversed course and adopted the Police Jury plan was to

comply with traditional districting principles, this would

be a different case. But here the record shows that

Bossier’s plan does not comply with its own criteria.

Indeed, while the majority understandably made no

finding at all on this subject, Judge Kessler found that

the plan “plainly violates a whole number of redistricting

principles.” App. 51a.

For example, Bossier claims without support that the

Police Jury plan “clearly complied with state law,” B.P.

Br. 40, but the undisputed evidence shows that the

Police Jury plan violated state law in at least two

respects: by including a district that is not contiguous

and by exceeding the maximum allowable deviation

from one person, one vote. App. 84a (Stip. 58): D-I

Exh.Gffl[31, 32.

The Board also claims without support that the Police

Jury plan was compact. B.P. Br. 40. To the contrary,

the stipulated facts demonstrate: (1) that the Board’s

cartographer, Gary Joiner, admitted that one-third of its

districts were not compact, App. llla-12a (Stip. 139);

and (2) that one district “contained almost half of the

geographic area of the Parish.” App. 50a (Kessler, J.,

dissenting); App. 112a (Stip. 140).

Likewise, Joiner’s own testimony defeats Bossier’s

claim that there is no showing that the Police Jury plan

“‘fragments’ any concentration of minority voters.” B.P.

Br. 41. In fact, Joiner admitted that the plan appears to

“fracture” the predominately black neighborhood

surrounding two predominantly black elementary

schools. App. 11 la-13a (Stip. 137, 138,. 142).

17

Bossier also claims without support that the Police

Jury plan maintained the “integrity of municipal”

boundaries “like all prior redistricting plans,” B.P. Br. at

40, 2, but the record shows: (1) no information about

any plan prior to 1980; (2) no indication that the Board

ever considered municipal boundaries in redistricting;

and (3) several stipulations that the Board was

concerned instead about the location of schools in its

districts, App. 72a-73a (Stip. 24), and the protection of

incumbencies, App. 28a; App. 50a, and that the Police

Jury plan violates these criteria. App. 112a (Stip. 141);

App. 28a; App. 50a (Kessler, J., dissenting).

Finally, Bossier claims that its plan “respect[s]. . . the

Police Jury districts,” B.P. Br. 2, but the pertinent evi

dence in the record is the stipulated fact that “[through

out the 1980s, the Police Jury and School Board

maintained different electoral districts.” App. 4a n.3.

F. The Board’s Alleged Concerns About the

Illustrative Plans Are Purely Pretextual and

Underscore Its Actual Discriminatory Purpose

Just as the majority below found that “the School

Board .. . offered several reasons for its adoption of the

Police Jury plan that clearly were not real reasons,”

App. 27a n.15 (emphasis added), Bossier’s current

assertions questioning plans with majority-black districts

are clearly pretextual.

The Board claims that the “black majority districts . . .

were plainly not compact,” B.P. Br. 40, but the record

shows (1) stipulations that the Bossier City district was

“an acceptable configuration from the standpoint of

district shape,” App. 115a (Stip. 150), and that it was

“obvious that a reasonably compact black-majority

district could be drawn within Bossier City,” id. at 76a

(Stip. 36), where “more than 50 percent of the black

population of Bossier Parish is concentrated,” id. at 68a

(Stip. 10); and (2) an illustrative majority-black district

18

in the northern part of Bossier Parish that is no more

irregularly shaped than any number of districts in the

Board’s 1980s plan and the current Police Jury plan.

See J.A. 42-43, 45-46, 51-52.

Bossier also now claims that the NAACP plan “split

every municipal boundary in the Parish,” but the record

contains a stipulation that “[o]verall, in the use of

logical, traditional features . . . the NAACP Plan is not

significantly different from the School Board plan.”

App. 113a (Stip. 144).

The Board claims as well that William Cooper drew

the NAACP plan “for the exclusive purpose of

‘creating] two majority-black districts.’” B.P. Br. 2

(quoting J.A. 260). But the intent of the drawers of the

various illustrative plans is irrelevant to the Board’s

intent in adopting the Police Jury plan. Moreover, the

record shows that (1) the NAACP plan (which Cooper

actually did not draw, App. 98a (Stip. 98)) was meant

only as an illustration for the Board’s information and

was not intended to “create” any districts at all, see D-I

Br. 16-17; and (2) as Cooper explained in the very testi

mony relied on by Bossier, his own subsequent illustra

tive plan was drawn to “assess whether or not it was

possible to create two majority black districts using

traditional redistricting criteria.” J.A. 260 (emphasis

added).

Bossier rests the bulk of its argument on the claim that

the NAACP plan “facially violated” state law because it

split precincts. B.P. Br. 43, 44. The record, however,

shows that (1) no one suggested that the Board split pre

cincts but that it consider working with the Police Jury

to establish new ones, App. 156a-57a; J.A. 136-43; (2)

the Board was well aware that it could work with die

Police Jury to have precincts modified, App. 6a-7a, 29a;

App. 99a-100a (Stip. 102); and (3) this procedure is

commonplace in Louisiana, App. 72a (Stip. 22-23); J.A.

137-38.

19

The Board’s elevation of precincts to the essential

“building blocks” of Louisiana election districts is

simply false. B.P. Br. 43. While Bossier claims that the

precincts were “used by the Police Jury for its districts,”

id., the record is clear that the Police Jury first drew its

new election districts and then had to create a new

system of precincts, with at least 13 new ones. App

85a, 88a, 82a-88a (Stip. 60 70, 52-68). The parties also

stipulated that “Bossier Parish has made a number o f .

precinct realignments in the last ten years,” id. at 77a

(Stip. 38), and Bossier’s own evidence confirms that the

Police Jury changed precincts in 1987, 1989 and 1991,

PI. Exh. 1, and intended to consolidate precincts again in

1993. App. 85a-86a (Stip. 61).

White Bossier claims, with no record support, that it

has a longstanding, uniform practice of preserving

Police Jury precincts,” B.P. Br. 47, the state statute

requiring die use of whole precincts by school boards

did not even apply to any prior redistricting. J.A. 265-

66. After the 1980 census, for example, Louisiana law

provided that “school board election districts . . . need

n o t . . . have any relation to, the . . . precincts that may

be created by die police jury.” Id. at 263 (emphasis

added). Bossier also claims that it was “required to use

[the] existing 1991 precincts,” B.P. Br. 2, but, even

under the new statute, the whole-precinct requirement

did not apply where “the number of members of the

school board is not equal to the number o f’ police

jurors, J.A. 266, and a plan with five, seven or nine

members, rather than 12, was one of the options that the

Board originally considered but then abandoned without

explanation. Tr. I at 44.

u Most importandy, white Bossier now implies it was

powerless” to develop a plan that did not employ all of

the Police Jury’s precincts, B.P. Br. 43, the majority

below found that the Board was “free to request precinct

changes from the Police Jury,” App. 7a, and it is undis

20

puted that the Board knew it could “work with the Police

Jury to alter the precinct lines.” App. 95a (Stip. 89). It

also is undisputed that through such cooperation the

Police Jury could reduce its total precincts from 56 to 46

without changing its own election districts at all and still

accommodate a School Board plan with two majority-

black districts. D-I Exh. G f 36. Nevertheless, the

Board never even approached the Police Jury about

modifying precincts. App. 7a. As a result, its alleged

concern over precinct-splitting must be treated as pre-

textual, particularly in the face of the overwhelming evi

dence showing that the abrupt, belated adoption of the

Police Jury plan was at least in part racially motivated.

When all the stipulated and unrebutted evidence is

fairly considered under the governing standards, it is

“far from being equally convincing on either side. Not

only does the evidence fail to prove absence of dis

criminatory purpose, it shows that racial purpose fueled

the School Board’s decision.” App. 38a-39a (Kessler,

J., dissenting). This Court, therefore, should reverse.

CONCLUSION

Respectfully submitted,

Barbara R. Arnwine

Thomas J. Henderson

Brenda Wright

Samuel L. Walters

Walter A. Smith, jr.

Patricia A. Brannan*

JohnW. Borkowski

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

1450 G Street, N.W., Suite 400

Hogan & Hartson l .l .p .

555 Thirteenth Street, N W .

Washington, D.C. 20004

(202) 637-8686

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 662-8322

* Counsel of Record Counsel fo r Appellants

George Price, etal.