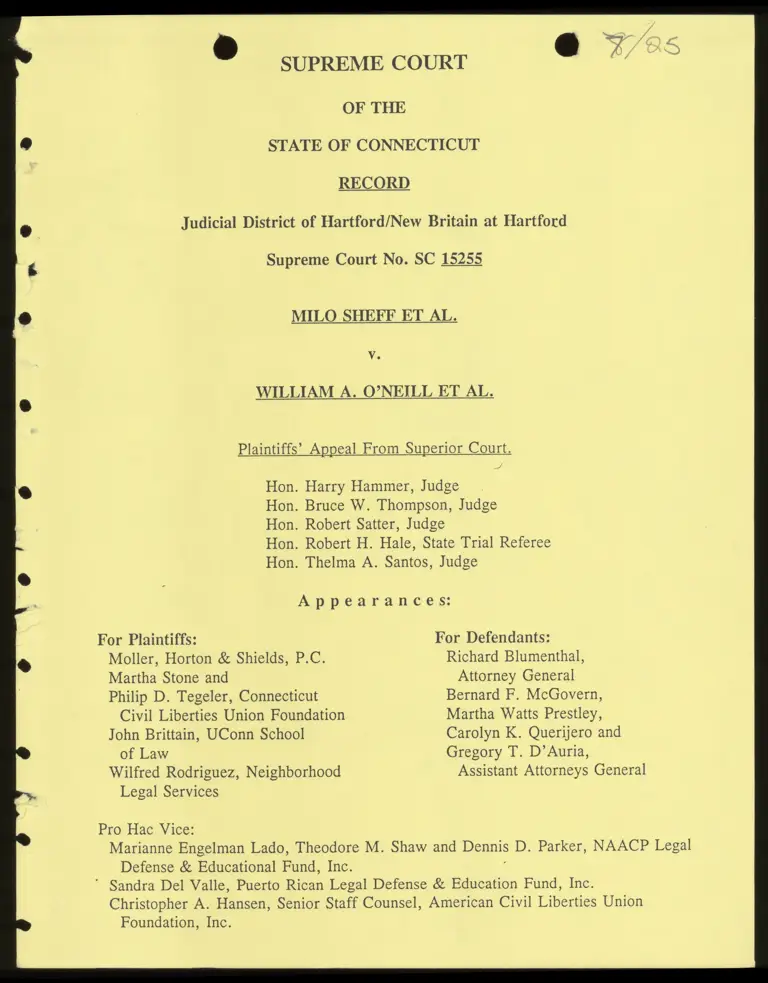

Record: Supreme Court of the State of Connecticut No. SC 15255

Public Court Documents

July 25, 1995

380 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Record: Supreme Court of the State of Connecticut No. SC 15255, 1995. a5b2009b-a146-f011-8779-7c1e5267c7b6. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/23db6b46-b218-4869-8cdb-5a254f6370ef/record-supreme-court-of-the-state-of-connecticut-no-sc-15255. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

A

SUPREME COURT

OF THE

STATE OF CONNECTICUT

RECORD

Judicial District of Hartford/New Britain at Hartford

Supreme Court No. SC 15255

MILO SHEFF ET AL.

Y.

WILLIAM A. O’NEILL ET AL.

Plaintiffs’ Appeal From Superior Court.

4

Hon. Harry Hammer, Judge

Hon. Bruce W. Thompson, Judge

Hon. Robert Satter, Judge

Hon. Robert H. Hale, State Trial Referee

Hon. Thelma A. Santos, Judge

Appearances:

For Plaintiffs: For Defendants:

Moller, Horton & Shields, P.C. Richard Blumenthal,

Martha Stone and Attorney General

Philip D. Tegeler, Connecticut Bernard F. McGovern,

Civil Liberties Union Foundation Martha Watts Prestley,

John Brittain, UConn School Carolyn K. Querijero and

of Law Gregory T. D’Auria,

Wilfred Rodriguez, Neighborhood Assistant Attorneys General

Legal Services

Pro Hac Vice:

Marianne Engelman Lado, Theodore M. Shaw and Deans D. Parker, NAACP Legal

Defense & Educational Fund, Inc.

" Sandra Del Valle, Puerto Rican Legal Defense & Education Fund, Inc.

Christopher A. Hansen, Senior Staff Counsel, American Civil Liberties Union

Foundation, Inc.

Cc Bass oo :

ABLE OF CONTENTS

No. Item

Page

i. Docket Entries 1

2. Revised Complaint 16

3. Revised Answer 48

4. Reply to Special Defenses 70

5, Motion to Strike 72

6. Memorandum of Decision on Motion to Strike 76

1. Motion for Summary Judgment 93

8. Memorandum of Decision on the Defendants’ 96

Motion for Summary Judgment

9. Memorandum of Decision 108

10. Plaintiffs’ & Defendants’ Revised Stipulations 180

of Fact

11. Plaintiffs’ Revised Proposed Findings of Fact 219

12 Defendants’ Revised Proposed Findings of Fact 291

13. Finding 233

14 Judgment File 361

15. Appeal Form 366

16. Docketing Statement 368

17. Transfer Letter 372

18 Preliminary Statement of Issues (Plaintiffs’) 373

19. Preliminary Statement of Issues (Defendants’) 375

036091¢7 S i MISC DECLARATORY JUDGMENT K:

Cv 89

SHEFF CHNRTEARD | 04-28-89

vs. SUPPL NOT ON TRLST

O'NEILL AEPL NON PRIV,

PRO SE PARTIES If 0 TT TPR Ei PARTIES

MARIANNE LADO PRO HAC VICE 18 ALFRED A. LINDSETH PRO HAC V 61

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND . 0 to ICE

99 HUDSON STREET Hhnto 02 999 PEACHTREE STREET NE «01

MEW YORK, NY 10013 .03 ATLANTA, GA +02

HELEN HERSHXOFF QUT OF STATE 19 30309 «03

ATTORNEY

AMERICAN CIVIL LIB. UN. «01 | AAG PERNEREWSKI 085078

132 WEST 43 ST. «02 WILLIAM A. O'NEILL GOVERNOR 50

NEW YORK, NY 10036 «03 91-11-26

RONALD ELLIS PRO HAC VICE 20 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION 51

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE FUND «D1 91-11-26

99 HUDSON STREET «02 ABRAHAM GLASSMAN BOE MEMBER 52

NEW YORK, NY 10013 .03 91-11-26

SANDRA DEL VALLE PRO HAC VIC 21 WALTER A. ESDAILE BOE MEMBER 53

E 91-11-26

PUERTO RICAN LEGAL FUND +01 WARREN J. FOLEY B80E MEMBER 54

99 HUDSON STREET «02 91-11-26

NEW YORK, NY 10013 «03 RITA HENDEL BOE MEMBER 55

JA-0002A 05/01/95 1

MOLLER H E S PC 038478 | 91-11-26

MILO SHEFF PPA 01 JOHN MANNIX B80FE MEMBER 56 89-04-28 91-11-26

WILDALIZ BERMUDEZ PPA 02 JULTA RANKIN BOE MEMBER 57 89-04-28 91-11-26

PEDRO BERMUDEZ PPA 03 GERALD N. TIRDZZI COMMISSION 58 89-04-23 ER & MEMBER OF BOE

EVA BERMUDEZ PPA 04 91-11-26

89-04-28 FRANCISCO L. BORGES TREASURE 59 OSKAR M, MELENDEZ PPA 05 R STATE OF CT.

89-04-28 91-11-26

WALESKA MELENDEZ PPA 06 EOWARD J. CALDWELL COMPTROLL 60 89-04-28 ER STATE OF CT.

MARTIN HAMILTON PPA 07 91-11-26

89-04-28

DARRYL HUGHLEY PPA 08 1 AAG JR WHELAN 085112 89-04-28 WILLIAM A. O'NEILL GOVERNCR 50 JEWELL HUGHLEY PPA 09 89-06-01

89-04-28 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION 51

JA-0002A 05/01/95 2

DAVID We HARRINGTON PPA 10 | 89-06-01

89-04-28 ABRAHAM GLASSMAN BOE MEMBER 52

MICHAEL J. HARRINGTON PPA 11 89-06-01

89-04-28 WALTER A, ESDAILE BOE MEMBER 53

JOSEPH LEACH PPA 12 89-06-01

89-04-28 WARREN J. FOLEY BOE MEMBER 54

RACHEL LEACH PPA 13 89-06-01

£9-04-28 RITA HENDEL BOE MEMBER 55

ERICA CONNOLLY PPA 14 89-06-01

89-04-28 JOHN MANNIX BOE MEMBER 56

TASHA CONNOLLY PPA 15 89-06-01

89-04-28 JULTA RANKIN BOE MEMBER 57

16 89-06-01

bl hal pea GERALD N. TIROZZI COMMISSION 58

NEIIMA BEST PPA 17 ER £& MEMBER OF BOE

89-04-28 89-06-01

JANELLE HUGHLEY 22 FRANCISCO L. BORGES TREASURE 59

93-01-29 R STATE OF CT.

89-06-01

JA-0002A 05/01/95 3

0360974)

MISC DECLARATORY JUDGMENT @ 05-30-89

Me. SYDNE 061506 EDWARD Je. CALDWELL COMPTROLL 60

MILD SHEFF PPA 01 ER STAYE OF CTY,

89-04-28 B9=-06=01

WHILDALIZ B8ERMUDEZ PPA 02

89-04-28 AAG BF MCGOVERN 085230

PEDRO BERMUDEZ PPA 03 WILLIAM A. O'NEILL GOVERNOR 50

89-04-28 91-11-20

EVA BERMUDEZ PPA 04 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION 51

89-04-28 91-11-20

OSKAR M, MELENDEZ PPA 05 ABRAHAM GLASSMAN BOE MEMBER 52

B9-04-28 91-11-20

WALESKA MELENDEZ PPA 06 WALTER A, ESDAILE BOE MEMBER 53

89-04-28 91-11-20 i

MARTIN HAMILTON PPA 07 WARREN J. FOLEY BOE MEMBER 54%

89-04-28 91-11~20

DARRYL HUGHLEY PPA 08 RITA HENDEL BOE MEMBER 55

89-04-28 91-11-20

JEHELL HUGHLEY PPA 09 JOHN MANNIX BOE MEMBER 56

89-04-28 91-11-20

JA-0002A 05/01/95 4

DAVID W. HARRINGTON PPA 19 JULIA RANKIN BOE MEMBER 57

89-04-28 91-11-20

MICHAEL J. HARRINGTON PPA 11 GERALD N., TIR0ZZI COMMISSION 58

89-04-28 ER & MEMBER OF B(QE

JOSEPH LEACH PPA 1:2 91-11-20

89-04-28 FRANCISCO L. BORGES TREASURE 59

RACHEL LEACH PPA 13 2 STATE DF CT,

B9-04-28 91-11-20

ERICA CONNOLLY PPA 14 EOWARD J. CALDWELL COMPTROLL 60

89-04-28 ER STAYE OF CT,

TASHA CONNOLLY PPA 15 91-11-20

89-04-28

LISA LABQOY PPA 16! ReA. HEGHMANM 100091

89-04-28 VICTORIA A HEGHMANN 52

NETIIMA BEST PPA 17 93-04-30

89-04-28 BEATRICE M HEGHMANN 63

93-04-30

J.CeBRITTAIN 101153

MILO SHEFF PPA 01 | AAG MW PRESTLEY 406172

JA-0002A 05/01/95 5

89-04-28 WILLIAM A. O'NEILL GOVERNOR 50

WILDALIZ BERMUDEZ PPA 02 92-07-10

89-04-28 STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION 51

PEDRO BERMUDEZ PPA 03 92-07-10

89-04-28 ABRAHAM GLASSMAN BOE MEMBER 52

EVA BERMUDEZ PPA 04 92-07-10

89-04-28 WALTER A. ESDAILE BOE MEMBER 53

OSKAR M., MELEMDEZ PPA 05 92-07-10

89-04-28 WARREN Je. FOLEY BOE MEMBER 54

WALESKA MELENDEZ PPA 06 92-07-10

89-04-28 RITA HENDEL BOE MEMBER 55

MARTIN HAMILTON PPA 07 92-07-10

89-04-28 JOHN MANNIX BOE MEMBER 56

DARRYL HUGHLEY PPA 08 92-07-10

89-04-28 JULIA RANKIN BOE MEMBER 57

JEWELL HUGHLEY PPA 09 92-07-10

89-04-28 GERALD N. TIR0DZZI COMMISSION 58

DAVID He. HARRINGTON PPA 10 ER & MEMBER OF BOE

89-04-28 92-07-10

JA-0002A 05/01/95 6

0360977 S & MISC DECLARATORY JUDGMENT % 05-30-89

MICHAEL J. HARRINGTON PPA 11; FRANCISCO L. BORGES TREASURE 59

89-04-28 R STATE OF CT.

JOSEPH LEACH PPA 121 92-07-10

» 89-04-28 | EDWARD J. CALDWELL COMPTROLL 60

RACHEL LEACH PPA 13 | ER STATE OF CT.

89-04-28 92-07-10

ERICA CONNOLLY PPA 14

89-04-28

TASHA CONNOLLY PPA 15 |

89-04-28 -

LISA LABOY PPA 16

[ 89-04-28

NETIMA BEST PPA 17

89-04-28

M.B.ALISBERG 102157

MILO SHEFF PPA 01

89-04-28

WILDALIZ BERMUDEZ PPA 02

*®

JA-0002A 05/01/95 7

89-04-28

PEDRO BERMUDEZ PPA 03

89-04-28

EVA BERMUDEZ PPA 04 i

® 89-04-28 |

OSKAR M. MELENDEZ PPA 05

89-04-28

WALESKA MELENDEZ PPA 06

89-04-28

MARTIN HAMILTON PPA 07

A9-04-28

DARRYL HUGHLEY PPA 08 |

» 89-04-28

JEHELL HUGHLEY PPA 09 |

89-04-28 :

DAVID We. HARRINGTON PPA 10

89-04-28

MICHAEL J. HARRINGTON PPA 11

89-04-28 i

®

JA-0002A 05/01/95 8

JOSEPH LEACH PPA 12

89-04-28

RACHEL LEACH PPA 13

89-04-28

ERICA CONNOLLY PPA 14

® 89-04-28

TASHA CONNOLLY PPA 15

89-04-28

LISA LABOY PPA 16

89-04-28

NETIMA BEST PPA 17

89-04-28

: ) P.D.TEGELER 102537

MILO SHEFF PPA 01

89-04-28

WILDALIZ BERMUDEZ PPA 02

89-04-28

PEDRO BERMUDEZ PPA 03

\ JA-0002A 05/01/95 9

020097 ily MISC DECLARATORY JUDGMENT 3 05-30-89

89-04-28 1 _—

EVA BERMUDEZ PPA 04

89-04-28

OSKAR M. MELENDEZ PPA 05

89-04-28

WALBSKA MELENDEZ PPA 06

89-04-28

MARTIN HAMILTON PPA 07

89-04-28

DARRYL HUGHLEY PPA 08

89-04-28

JEWELL HUGHLEY PPA 09 |

89-04-28 i

DAVID HW. HARRINGTON PPA 10

89-04-28

MICHAEL J. HARRINGTON PPA 11

89-04-28

JOSEPH LEACH PPA 12

89-04-28

JA-0002A 05/01/95 10

RACHEL LEACH PPA 137 SES

89-04-28

ERICA CONNOLLY PPA 14

89-04-28

TASHA CONNOLLY PPA 15

89-04-28

LISA LABOY PPA 16

89-04-28

NETIMA BEST PPA 17

89-04-28

We RODRIGUEZ 302827

MILO SHEFF PPA 01 |

89-04-28

WILDALIZ BERMUDEZ PPA 02

89-04-28

PEDRO B8ERMUDEZ PPA 03

89-04-28

EVA BERMUDEZ PPA 04

JA-0002A 05/01/95 11

89-04-28

OSKAR M. MELENDEZ PPA 05

89-04-28

WALESKA MELENDEZ PPA 06

89-04-28

MARTIN HAMILTON PPA 07

89-04-28

DARRYL HUGHLEY PPA 08

89-04-28

JEWELL HUGHLEY PPA 09

89-04-28

DAVID W. HARRINGTON PPA 10

89-04-28

MICHAEL J. HARRINGTON PPA 11

89-04-28

JOSEPH LEACH PPA 12

89-04-28

RACHEL LEACH PPA 13

89-04-28

JA-0002A 05/01/95 12

ERICA CONNDLLY PPA 14

89-04-28

TASHA CONNOLLY PPA 15

89-04-28

LISA LABOY PPA 16

B9-04=-28

NETIMA BEST PPA 17

89-04-28

EN

EN

|

E

o

3

D

I

|

[9 o

To

¢)

0

0

h

e

r

e

(©

)

C

I

I

C

I

N

h

o

O

N

G

N

N

D

O

D

104-0

03-21-89

113-00

2-14-30

114-00

02-14-99

119-09

NI=23~3)

PTE

PTF

GRNTD 07-31-89

DFD

ine] -

Le LL. TQ APDEAR

1D~ 31=89

NADER 11=21=29

Lay

GINYID 12-07-39

CRY

ORDER 12-94-89

NSEL ADDE AR

NTD 02-14-90

.

SHE

AFFIDAVIT

MOTINDN FOR (ORDER

THOMPSON,

MOTION TO STRIKE

MEMORANDUM

MOTINN FOR PERMISSION FOR DUTY

HAMMER, J.

D8JELTION TO MOTION TD

ION TO MOTION

STATEMENT

MOTION FOR ORDER

HAMMER, J.

MOTION FOR DRDER

FILE WITH

LAW CLERKS

HAMMER, J,

REPLY

MOTION

HALE, R.

AFFIDAVIT

MEMNR AND

L,

/01795

V NINETLL

iA-00073A

J

DF STAYE

STRIKE AND

FOR PERMISSION FOR QUT OF STATE

120-00

“o7- 9% 9)

125-00

07-05-90

126-00

07=17~90

CRY

PTE NOTICE OF FILING OF DISCOVERY REQUEST

PTE MOTION FOR PERMISSION TO WITHDRAW

APPEARANCE

DED MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

AITH MOTION FR D1SCLOSURE/PRODUE TION

LAW CLERKS

ORNER 03-1930 HAMMER, J.

PTF NOTICE OF FILING OF DISCOVERY REQUEST

DED DISCLOSURE AND PRODUCTION

DED MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

DFO ANSWER AND SPECIAL DEFENSE

DF) NOTICE

DED DISCLOSURE AND PRJODUCTIDCNM

DED NOTICE OF FILING OF INTERROGAYORIES

PYF REPLY TO. SPECIAL DEFENSE

CLAIM FOR TRIAL L157

PYF MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTION

PTF NOTICE

STATUS INTERMED APPEAL

SUPERIDR 05/01/95

SHEFF V DINEILYL

A OMOEA

uRA-uUuuvoAm

131-00 PYF OBJECTION TN INTERROGATORIES

09-24-90

132-00 DED MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

10-15-99

* 10-22-99) ~

133-00 OFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

10-26-90 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTION

GRNTD 10-26-90 HAMMER, J.

134-00 PYLE MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME YO COMPLY

10-31-99 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRCDUCTION

%.:11~07=90

135-00 PTF NOTICE DOF RESPONSES TO INTERRBNGATNRIES

10~31=90

135- OFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME RE

11-28-90 DISCOVERY MOTION OR REQUEST P3 (HB

137-C0 PYF NOTICE OF FILING OF DISCOVERY REQUEST

11-30-99

138-00 PIE MOYION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

12-10-90 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLNSURE/PRODUCTION

139~ PYF O8JECTION TO INTERROGATORIES

12-10-30

140-09 DFD REQUEST FDR ADMISSION PB-238

12-03-90

141-00 OFD OBJECTION TO INTERROGATORIES

12-0399

142-00 DFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

12-03-30 x

143-00 DFD NOTICE OF FILING OF DISCOVERY REQUEST

12=03~33

143-50 DFD MOYION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME RE

12-21-90 DISCOVERY MOTION OR REQUEST P83 CHB

144-00 PYF NOTICE

01=15+9}

LV KEY POINT STATUS INTEOMED ADPCAL

29... HAIEQRD SUPERIOR 05/01/95

DN D35° 09 77S SHEFF Y O'NEILL

IA-GO03A

Le MOTION FOR PROTECTIVE ORDER

GRNTD 01-23-91 HAMMER, J.

145-10 CRY ORDER ENTERED

01-23-91 ORDER 01-23-91 HAMMER, J. -

146-00 PTE MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME RE

01-30-91 DISCOVERY MOTION OR REQUEST P8 CHB

« 02-06-91

147-00 PTF NOTICE

02-19-91

148-00 DFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

04-29-91 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTION

x 05-06-91

153-00 DAD MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

% 07-23-91 DEND 02-24-92 HAMMER, J.

150-00 DEN MEMORANDUM

07-08-91

151-00 DED MEMORANDUM

07-93-91

152-00 PTE MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

07-26-91 GRNTD 07-26-91 HAMMER, J.

153-09 PTF MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

09-03-91.

% 09-10-91

154-00 oTE AMENDED COMPLAINT

09-20-91

155-00 PTE MOTION TO CITE ADDITIONAL PARTY

09-20-91 :

x 09-27-91

156-00 PTF AFFIDAVIT

09-20-91.

157-09 PTF AFFIDAVIT

09-20-91

153-00 PTE AFFIDAVIT

09-20-91

CY KEY POINT STATUS INTERMED APPEAL

89 HARTFORD SUPERIOR 05701795

0 035 09 77 S SHEFF V DYNEILL

~~ AEE

VAP REA F

A

A

159-00 PTF MEMORANCUM

07-20-31

160-00 DFD MEMORANDUM

11-05-91

161-00 DYF MOTION FOR (ORDER

21-10-92

* 01-11-92

152-00 PTF MEMORANDUM

01-10-91

1 3 Oa 33 CRY MEMORANDUM OF DECISION ON MOTION

ORDER 02-24-92 HAMMER, J.

164-00 OFD WITHDRAWAL OF APPEARANCE

2-23-62

165-00 PTE MOTION FOR PERMISSION FOR JUTY OF STATE

03-10-92 COUNSEL TO APDCAR

GRNTD 03-05-92 HAMMER, J.

165-00 DED MOTION FOR ORDER

D3=24~32

i 0D3-31~92

1567-00 PYF MOTION FCR ORDER

Q4-01=92

x 04-08-92

163-00 PTF MEMORANDUM

04-01-92

163-590 LRT ORDER

04~103=92

ORDER 04-19-92 HAMMER, J.

169-900 DFD MOTION FOR ORDER OF COMPLIANCE -

NS~18-92 PR SEL:231 -

170-00 PIF MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

04-30-92 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRCDUCTION

17100 PTF MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

05-29-92 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTION

1712-00 CRT ORDER ENTERED

0p-10-92

DRDER 06-10-92 HAMMER, J.

KEY POINT STATUS INTERMED APPEAL 3

HARTFORD SUPERIOR 05/01/95

35.0977 5 SHEFF V OINEILL

-3002A

173-00 WIT STIPULATIDN »

06-10-92

174-00 CRT ORDER

N6E=-10-92

ORDER 06-10-92 HAMMER, J.

175-00 PTF MEMORANDUM »

06-12-92

176-00 CRT FILE WITH

N7-08-92

GRNTD 07-08-92 HAMMER, J.

177-00 DFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME ®

07-14-92

* 07-21-92

178-00 PTF REQUEST FOR LEAVE TO FILE AMENDMENT

07-27-92 AND AMENDMENT

179-00 DFD MATION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

07-31-92 “

% 08-07-92

179-50 DED AMENDMENT

N8=12=-92

182-00 PTF MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TD COMPLY

18-14-92 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTIODN he

% 08-21-92

131-00 DFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

08-17-92 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRIODUCTION

% 0R=24-92

182-00 PTF CBJECTION TO EXTENSION OF TIME MOTION

08-20-02 ®

183-00 DFD MOTION FOR ORDER (OF COMPLIANCE -

N8=-26-92 PB SEC 231 i

184-00 DFD MEMORANDUM

0B=26-G2 @

185-00 OFD MOTION FOR ORDER

08-27-92

* 09-03-92

186-00 CRY ORDER

N9-02-92 »

NRDER 09-02-92 HAMMER, J.

CY KFY POINT STATUS INTERMED APPEAL 6

89 HARTFORD SUPERIOR 05/01/95

ON 036 09 77 S SHEFF Vv O'NEILL

IR=OOnaA »

» 127-09 OFD MOTION FOR ORDER

09-93-92

x 09-10-92

188-00 DFD MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

09-30-92

x 10-07-92

® 189-09 TE MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

10-01-92

% 10-08-92

190-00 DFO MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME

10-01-92 * 10-08-92

° 191-00 PTF MOTION TO COMPEL

10-05-92

% 10-12-92

192-00 DED MOTION FOR PERMISSION FOR OUT NF STATE

10-05-92 COUNSEL TO APPEAR

% 10-12-92

193-00 PTE MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

® 10-16-92 WITH ¥OTION £0? DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTION

194-00 ED MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME TO COMPLY

10-15-92 WITH MOTION FOR DISCLOSURE/PRODUCTION

© 10-22-92

195-09 OFD IBJECTION TO MOTION

® 19-24-92

« {1-62-93

195-00 DFD 0SJECTION TO INTERROGATORIES

10-26-92

197-00 PTE MOTION FOR EXTENSION OF TIME RE

» 10-29-92 DISCOVERY MOTION OR REQUEST PB CHB

11-04-92

198-00 DFD REPLY

11-23-92

199-00 PTF MOTION FOR PERMISSION FOR OUT OF STATE

» 11-19-92 CQUNSEL TD APPEAR

GRNTD 11-19-92 HAMMER, Jo

200-00 DEN MEMORANDUM

11-16-92

200-10 PTF MEMORANDUM

® 11-16-92

CY KEY ONOTINT STATUS INTERMED APPEAL 7

89 HARTFOR0 SUPER [OR 05/01/95

DN 036 09 77 S SHEFF V O'NEILL

NC PIVENTY A

2850-20

11-16~92

20030

N1=213=93

200-490

01-13-93)

200-50

01-20-93

200= 930

01-27-33

201-09

31-27-93

231-15

Dl=27-93

201-20

31-37-93

201-390

D1-28-93

201-40

D1~-23=-93%

NT STATUS

PIF

DFD

NRNER 01-13-93

DFD

PTF

PTF

DFD

NFD

DFD

DED

PTF

GRNTD 01-28-93

PTF

PTE

GRNTD 01-23-93

PTF

PTF

5

SHE

STIPULATION

D3JECYION TO MOTIDN

HAMMER, J.

DISCLOSURE GF EXPERT WITNESS

REQUEST TO AMEND COMPLAINT/AMENDMENT

AMENDMENT

AMENDMENT

ANSWER TO AMENDED COMPLAINT

NAJ=CT INN

Q8JECT ION

N3JECT ION

REQUEST TO AMEND COMPLAINT/AMENDMENT

HAMMER, J.

AMENDMENT TO COMPLAINT

MOTION TO SUBSTITUTE PARTY

HAMMER, J.

AMENDMENT

REQUEST TO AMEND COMPLAINT/AMENDMENT

V.OINETLL

Fn: tm pn pe a

JArUUL OMA

291-19

N2-25-933

202-00

N4-03

203-00

04-01

204-00

4-19-33

205-00

04-19

-93

-933

-93

PTF

PTF

D¥D

PYF

AREF

PTF

DEN

DFD

DFD

PTF

CRMYD 07-09-33

PIF

DFD

DED

COUNSEL TO APPAR

IER

RINR

YMED APP

AMENDED COMPLAINT

REPLY TO SPECIAL OEFENSE

ANSWER TO AMENDED COMPLAINT

MOTION FOR

BRIEF

EXTENSION OF TIME TO FILE

MOTION TO INTERVENE

MEMORANDUM

MEMORANDUM

MOTION FOR

MOTION FOR

ARIEF

MOTION FOR

ARYIEF

BRIEF

MOTION FOR

EAL

05/01/95

EXTENSION OF YO: FILE

EXTENSION OF

EXTENSION OF TIME

HAMMER, Je.

PERMISSION FOR OUT OF STATE

VY -O'NEILL

AE

HET PAVE

212-75 OFD WITHDRAWAL OF MOTION

12-14-93

212-80 PTF BRIEF

31-31-94

212-85 PTF BRIEF

01-31-94

212- DFD BRIEF

01-31-94

213-00 DFD MEMORANDUM

05-26-94

214-00, or PTE REQUEST TO AMEND COMOLAINT/AMENDMENT

215-00 DFD OBJECTION TO REQUEST TOD REVISE

10-14-94

% 10-21-94

216-00 DED N8JECTICN TO REQUEST TO AMEND

10-17-94

x 10-24-94

216-50 PTF AMENDED COMPLAINT

11-23-94

217-00 PTF REPLY TO SPECIAL DEFENSE

11-28-94

218-00 DEN AMSWER TO AMENDED COMPLAINT

11-28-94

219-09 TRIAL COMPLETED-DECISION RESERVED

11-30-94

11-30-94 - HAMMER, Je

220-00 WIT AFFIDAVIT

12-27-94

221-09 DTF WAIVER-GENERAL

03-27-95

221-10 PTF STIPULATION

03-27-95

CV KEY POINT STATUS [INTERMED AOPEAL 10

89 HARTFORD SUPERIOR 05/01/95

DN 036 09 77 S SHEFF V DUNEILL

222-99 CRT MEMORANDUM OF DECISION

04-12-95

ORDER 04-12-95 HAMMER, J.

223-0 JUDGMENT AFTER COMPLETED TRIAL TN THE

04-12-95 COURT FOR THE DEFENDANT (S)

04-12-95 HAMMER, J, _

224-00 DFO MOTION FOR ORDER

04-25-95

* 05-02-95

225-00 PTF APPEAL TO APPELLATE COURT

04-27-95

224-00 PTF MOTION FOR PERMISSION FOR QUT OF STATE 74-27-95 COUNSEL TN APPEAR

GRNTD 04-27-95 SANTOS, J.

K=Y POINT STATUS INTERMED APPEAL

HARTFORD SUDERTOR 05701795

35 n9 77 S SHEFF V J'NEILL

11

NO. CV 89-0360977S

MILO SHEFF, ET AL. SUPERIOR COURT

VS. JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF HARTFORD/

NEW BRITAIN AT HARTFORD

WILLIAM A. O’NEILL, ET AL. NOVEMBER 23, 1994

REVISED COMPLAINT

1. This complaint is brought on behalf of school children in the

Hartford school district, a great majority of whom -- 91 percent -- are

black or Hispanic, and nearly half of whom -- 47.6 percent -- live in

families that are poor. These children attend public schools in a

district that is all but overwhelmed by the demand to educate a student

population drawn so exclusively from the poorest families in the

Hartford metropolitan region. The Hartford school district is also

racially and ethnically isolated: on every side are contiguous or

adjacent school districts that, with one exception are virtually

all-white, and without exception, are middle- or upper-class in

socioeconomic composition.

2. This complaint is also brought on behalf of children in

ar % —-— i

suburban school districts that surround Hartford. Because of the

racial, ethnic, and economic isolation of Hartford metropolitan school

_

districts, these plaintiffs are deprived of the opportunity to

associate with, and learn from, the minority children attending school

®

ith the Eartford school district.

3. The educational achievement of school children educated in

lene Hartford school district is not, as a2 whole, nearly as great as

®

that of students educated in the surrounding communities. These

disparities in achievement are not the result of native inability: |

lpoor and minority children have the potential to become well-educated,

H

e

cut, by tolerating

las do any other children. Yet the State of Connect Y

|

Ischool districts sharply separated along racial, ethnic, and econcmic

|lines, has deprived the plaintiffs and other Eartford children of thelr’

. rights to an eguzl educational cppeortunity, and to a minimally adequate

education -- rights to which they are entitled under the Connecticut

Constitution and Connecticut statutes.

® 4. The defendants and their predecessors have long been aware of

the educational necessity for racial, ethnic, and economic integration

in the public schools. The defendants have reccgnized the lasting harm

® inflicted on poor and minority students by the maintenance of isolated

urban school districts. Yet, despite their knowledge, despite treln:

: Constitutional and statutory obligations, despite sufficient legal

® tools to remedy the problem, the defendants have failed to act

effectively to provide equal educational opportunity to plaintiffs and

other Eartford schoolchildren.

®

- -

J

|

Legislative or the Executive branch. Under Connecticut’s constitut

|

5. Equal educational opportunity, however, is not a matter of

|

sovereign grace, to be given or withheld at the discretion of the

| on,

it is a solemn pledge, 2 covenant renewed in every generation between

the people of the State and their children. The Connecticut

Constitution assures to every Connecticut child, in every city and

ortunity to education as the surest means by which to

| y : ‘ d >

phage his or her own future. This lawsuit is brought to secure this

basic constitutional right for plaintiffs and all Connecticut

|

i

Ibrings this action as his next friend... Ee

schoolchildren.

A. PLAINTIFFS

6. Plaintiff ¥ilo Sheff is = fourteen-vear-old black child. Ee

resides in the city of Eartford with his mother, Elizabeth Sheff, who

is enrolled in the eighth

grade at Quirk Middle School.

2. ©Plaintiff wildaliz Bermudez is a ten-year-old Puerto Rican

-

child. She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Pedro and

-~ A

—

Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this section 2s. her next friend. She

is enrolled in the fifth grade at Kennelly School.

I

8. Plaintiff Pedro Bermudez is an eight-year-old Puerto Rican

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his parents, Pedro and

Carmen Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the third grade at Kennelly School.

9. Plaintiff Eva Bermudez is a six-year-old Puerto Rican child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Pedro and Carmen

Wilda Bermudez, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in Kindergarten at Kennelly School.

10. Plaintiff Oskar M. Melendez is a ten-year-old Puerto Rican

child. He resides in the Town of Glastonbury with his parents, Oscar

and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the fifth grade at Naubuc School.

11. Plaintiff Waleska Melendez is a fourteen-year-old Puerto

Rican child. She resides in the Town of Glastonbury with her parents,

Oscar and Wanda Melendez, who bring this action as her next friend.

She is a freshman at Glastonbury High School.

12. Plaintiff Martin Hamilton is a thirteen-year-old black

child. He resides in the City of Hartford with his mother, virginia

i ~Pertillary who brings this action as his next friend. He is enrolled

in the seventh grade at Quick Middle School.

13. [Withdrawn.]

14. Plaintiff Janelle Hughley is a 22-year-old black child. She

resides in the city of Hartford with her mother, Jewell Hughley, who

brings this action as her next friend.

® ) @ .

*

15. Plaintiff Neiima Best is a fifteen-year-old black child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Denise Best, who

brings this action’ as her next friend. She is enrolled as a sophomore »

at Northwest Catholic High School in West Hartford.

16. Plaintiff Lisa Laboy is an eleven-year-old Puerto Rican

ichild. She resides in the City of Hartford with her mother, Adria »

Laboy, who brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in |

lene £ifth crads. at Burr School. |

|

|

17. ©Plaintiff David William Harrington is a thirteen-year-old | “-

White child. He resides in the City of Eartford with his parents, |

Karen and Leo Harrington, who bring this action as his next frieand. He |

lis enrolled in the seventh grade at Quirk Middle School. | »

;

]

18. Plaintiff Michael Joseph Earrington is a ten-year-old white

lenila. Ee resides in the City of Eartford with his parents, Xaren and

Iteo Earrington, who bring this action as his next friend. Ee is -

enrolled in the fifth grade at Noah Webster Elementary School.

19. ©Dlaintiff Rachel Leach is a ten-year-old white child. She

resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents, Eugene Leach anc

Xathleen Frederick, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

I Ar waa -

enrolled in the fifth grade at the Whiting Lane School.

®

*

-5-

*

20. ©Plaintiff Joseph Leach is a nine-year-old white child. Ee

resides in the Town of West Hartford with her parents, Eugene Leach and

Kathleen Frederick, who bring this action as his next friend. He is

enrolled in the third grade at the Whiting Lane School.

51. Plaintiff Erica Connolly is a nine-year-old white child.

She resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Carcl Vinick and

Tom Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is

enrolled in the fourth grade at Dwight School.

52. Plaintiff Tasha Connolly is a six-year-old white child. She

resides in the City of Hartford with her parents, Carol Vinick and Tom

Connolly, who bring this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in

the first grade at Dwight School.

22a. Michael Perez is a fifteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. ie

resides in the City of Hartford with his father, Danny Perez, Who

brings this action as his next friend. Ee is enrolled as a sophomore

at Hartford Public High School.

22b. Dawn Perez is a thirteen-year-old Puerto Rican child. She

resides in the city of Hartford with her father, Danny Perez, Who

brings this action as her next friend. She is enrolled in the eighth

rade at-Qmirk Middle School.

23. Among tne plaintiffs are five black children, seven Puerto

fl . .

° hd Nd

Rican children and six white children. At least one of the children

|

lives in families whose income falls below the officizl poverty line;

five have limited proficiency in English; six live in single-parent

|

|

families.

B. DEFENDANTS

24. Defendant William O0’Neill or his successor is the Governor

's€ the State of Connecticut. sursuant to C.G.S. §10-1 and 10-2, with

the advice and consent of the General Assembly, he is responsible for

appointing the members of the State Board of Education and, pursuant to

lc.G.s. §10-4(p), is responsible for receiving a detailed stztement of

the activities of the board and an account of the condition of the

public schools and such other information as will assess the true

lcondition, progress and needs of public education.

25. Defendant State Board of Education of the State of

|

IConnecticut (hereafter nthe State Board!" or 'the State Board of

| rt

Education’) is charged with the overall supervision and control ©

educational interest of the State, including elementary and secondary

education, pursuant to C.G.S. §10-4.

56. “Defendants Ebraham Glassman, A. Walter Esdaile, wWarrel J.

Foley, Rita Eendel, John Mannix, and Julia Rankin, oT their successors

‘are members of the State Board of Education of the State of

Connecticut. Pursuant to C.G.S. §10-4, they have general supervision

and control of the educational interest of the State.

-] —-

Tirozzi or his successor is the

l

|

|

|

f

i

°*

all monies by the State.

27 Defendant Gerald N.

Commissioner of the Education of the State of Connecticut and az member

~f tha State Board of Education. Pursuant to C.G.S. §§l0-2 and 10-32,

he is responsible for carrying cut the mandates of the Board, and is

lsc director of the Department of Education {(hersafiexr "the state

Department of Education! or ''the State Department").

28. Defendant Francisco L. Borges or his successor is Treasurer

the State of Connecticut. Pursuant to £22 o2 the

Connecticut Constitution, he is

Ee is also the custodian of certain

educational funds of the Connecticut State Board of Education, pursuant

to C.G.5. 5810-11.

29. Defendant J. Edward Caldwell or his successor is the

Comptroller of the State of Connecticut.

§24 of the Connecticut Constitution and C.G.S. §3-112, he

responsible for adjusting and settling all public accounts and

II

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. A SEPARATE EDUCATION

30. School children in public schools throughout the State of

Connecticut, including the city of Hartford and its adjacent suburban

‘communities, are largely segregated by race and ethnic origin.

31. Although blacks comprise only 12.1% of Connecticut’s

'school-age population, Hispanics only 8.5%, and children in families

below the United states Department of Agriculture's official 'Ypoverty

ine only 9.7% in 1986, these groups comprised, as of 1987-88, 44.9%,

44.9%, and 51.4% respectively of the school-age population of the

Hartford school district. The percentage of black and Hispanic

(nereatter "minority") students enrolled in the Hartford City schools

has been increasing since 1981 at an average annual rate of 1.5%.

32. The only other school district in the Hartford metropolitan

area with a significant proportion of minority students is Bloomfield,

|

which has a minority student population of 69.9%.

»

33. The school-age populations in all other suburban school

districts immediately adjacent and contiguous to the Hartford school

®

district, (hereafter "the suburban districts), by contrast, are

overwhelmingly white. An analysis of the 1987-88 figures for Hartford,

Bloomfield, and each of the suburban districts (excluding Burlington,

a : eh :

jvaich has a joint school program with districts outside the Hartford

|

| metropolitan area) (reveals the following comparisons by race and ethnic |

| |

|origin: |

bd Total School Pop. %¥ Minority |

| |

|Hartford 25,058 90.5 |

|Bloomfield 2,555 69.9 |

RAEELEELEEEEEELES

| Avon 2,068 3.8 |

® | Canton 1,189 2.2 |

|East Granby 666 2.3

| Bast Hartford 5,905 20.8

East Windsor 1,267 8.5 |

Ellington 1,855 2.3

| Farmington 2,608 Tn’

® |Glastonbury 4,463 5.4

Granby 1,528 3.5

Manchester 7,084 31.1

Newington 3,801 6.4

Rocky Hill 1,807 5.9

Simsbury 4,039 5.5

\ South Windsor 3,648 9.3

suffield 1,772 4.0

Yernon 4,457 6.4

- | gest Hartford - 7,424 15.7

Wethersfield 2,997 3.3

Windsor 4,235 30.8

» Windsor Locks 1,642 4.0

®

-10-

.

34. Similar significant racial and ethnic disparities

~haracterize the professional teaching and aéninistrative staffs of

Hartford and the suburban districts, as the following 1986-87

comparisons reveal:

|

|

|

Staff % Minority

FEartford 2,044 33.2%

Bloomfield 264 13.8%

he ve Je Jk Je Je Je Je dk Je Je Jk dk Jk kk

Avon 379 3.1%

Canton 108 0.0%

mast Granby 57 1.8%

Fast Eartford 517 0.6%

East Windsor 102 4.9%

'Fllington 164 0.6%

Farmington 202 1.0%

Glastonbury 344 2.0%

Granby 131 0.8%

Manchester 537 "7

Newington 310 1.0%

Rocky Eill 154 0.8%

Simsbury 317 1.9%

South Windsor 294 1.4%

Suffield 143 0.7%

Vernon 366 03%

West Hartford 605 3.5%

Wethersfield 263 2.1%

Windsor 331 5.4%

Windsor Locks : 140 0.0%

B. AN UNEQUAL EDUCATION

35. Hartford schools contain a far greater proportion of

- a = - Th i es

students, at all levels, from backgrounds that put them 'at risx' ok

lower educational achievement. The cumulative responsibility fer

educating this high proportion of at-risk students places the Eartford

public schools at a severe educational disadvantage in comparison with

the suburban schools.

-11-

36. All children, including those deemed at risk of lower

edueation achievement, have the capacity to learn if given a suitable

® education. Yet because the Hartford public schools have an

extraordinary proportion of at-risk students among their student Er they operate at a severe educational disadvantage in

a addressing the educational needs of all students -- not only those who

are at risk, but those who are not. The sheer proportion of at-risk

students imposes enormous educational burdens on the individual

students, teachers, classrooms, and on the schools within the City of

Eartford. These burdens have deprived both the at-risk children and

all other Hartford schoolchildren of their right to an equal

® educational opportunity.

37. An analysis of 1987-88 data from the Eartford and suburban

ldistricts, employing widely accepted indices for jdentifying at-risk |

students -- including: (i) whether a child’s family receives benefits

under the Federal Aid to Families with Dependent children program, (a i

measure closely correlated with family poverty): (ii) whether a child

has limited english proficiency (hereafter np"); or (iii) whether a

child is from a single-parent family, reveals the following overall

bid ° —- ee. >

comparisons:

% on AFDC % LEP % Sql. Par. Fam.*

|IEartford 47

Avon 0

Bloomfield 4

Canton l.

East Granby 1

7 ® East Eartford

% on AFDC % LEP X% Sql. Par, Fam.*

Fast Windsor 3.56 25 8.3

Ellington 0.5 0.3 Ze?

Farmington 0.7 4+7 14.0

Glastonbury 1.5 1.4 10.0

Granby 0.6 0.0 5.5

Manchester 3.4 2+5 7.9

Newington 1.2 8.2 5.5

Rocky Eill 0.6 7 +5 13.4

Simsbury 02 1.4 7-6

South Windsor 0.4 4.4 8.4

suffield 0.8 2.31 8.4

Vernon 6.2 0... 9 13.5

west Rartford 2.0 7:3 10.9

Wethersfield 3.2 0.8 9.6

windsor vo 12.5 34.2

windsor Locks 3.3 2.3 13.4

* (Community-wide Data)

38. raced with these severe education burdens, schools in

Fartford school district have been unable to provide educational

opportunities that are substantially equal to those received by

schoolchildren in the suburban districts.

3g. As a result, the overall achievement of schoolchildren

the Eartford school district -- assessed by virtually any measures

educational performance -- is substantially below that of

schoolchildren in the suburban districts.

ar * Le 25 —

-13-

the

:

21

40. One principal measure of student achievement in Connecticut

is the Statewide Mastery Test program. Mastery tests, administered to

every fourth, sixth, and eighth grade student, are devised by the State

Department of Education to measure whether children have learned those

skills deemed essential by connecticut educators at each grade level.

41. The State Department of Education has designated both a

"mastery benchmark! -- which indicates a level of performance

reflecting mastery of all grade-level skills -- and a "remedizl

benchmark! —- which indicates mastery of "essential grade-level

skills." See C.G.S. §10-l4n {b}~-{C).

42. Eartford schoolchildren, on average, perform at levels

significantly below suburban schoolchildren on statewide Mastery

Tests. For example, in 1988, 34% (or 1-in-3) of all suburban sixth

graders scored at or above the "mastery benchmark" for reading, yet

only 4% {or l1-in~-235) of Eartford schoolchildren met that standard.

While 74% of all suburban sixth graders exceed the remedial benchmark

on the test of reading skill, no more than 41% of Eartford

in

schoolchildren meet this test of nessential grade-level skills.”

other words, fifty-nine percent of Eartford sixth graders ars reading

- i WE -—

below the State remedial level.

®- '®

*

*®

43. An analysis of student reading scores on the 1988 Mastery

| Test reveal the following comparisons:

% Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial Bnchmk. Remedial Bnchmk. Remedial Bnchmk. “

Eartford 70 59 57 |

\ de de J de Je Je de de Kk

| Avon 9 6 3

| Bloomfield 25 24 16

| Canton 8 10 2 SE

| East Granby 12 4 9 |

| East Hartford 38 30 36 |

| East Windsor 17 10 15

| Ellington 25 14 13

|' Farmington 12 3 10

| Glastonbury 15 3 13

| Granby is 14 17

| Manchester 22 1s 317

| Newington 8 15 12

Rocky Hill 13 10 24

| Simsbury 9 5 3

| South Windsor 9 13 16 @

| Suffield 20 10 15

Vernon 15 : 18 20

| West Hartford is 15 1x

| Wethersfield 18 12 14

| Windsor 26 i7 23

| Windsor Locks 25 16 17 ¢

®

we ei i a

i *

®

-15-

[

® @®

®

44. An analysis of student mathematics scores on the 1988 Mastery

Test reveals the following comparisons:

gi % Below 4th Gr. % Below 6th Gr. % Below 8th Gr.

Remedial BnchmX. Remedial BnchmX. Remedial Bnchmk.

Hartford 41 42 57

|| J J J Je Je Jk dk Jk Jk %k

PY avon 4 2 3

IBloomfield 6 23 18 :

Canton 3 8 .

[East Granby 10 7 6 |

iEast Eartford 14 19 19 |

lEast Windsor 2 9 19

® [Ellington 10 8 4 !

{Farmington 3 5 3 |

tGlastonbury 6 8 2

lGranby 3 12 31

IManchester 8 315 11

Newington 3 6 ¥

Rocky Hill 5 4 14

[J |simsbury 5 5 3

south Windsor 8 10 8

Ilsuffield 31 13 8

vernon 8 9 12

west Eartford 8 9 7

{Wethersfield 6 i! 6

® Windsor 32 13 26

Windsor Locks 2 7 14 :

45. Measured by the State’s own educational standards, tien, 2

majority of Hartford schoolchildren are not currently receiving even a |

®

nminimally adequate education.”

Jl. - 46. _Qther measures of education achievement reveal the same

pattern of disparities. The suburban schools rank far ahead of the

| Sos

"

Eartford schools when measured by: the percentage of students wko

remain in school to receive a high school diploma versus the percentage

»

-16-—

/

3

:

® xe

/

»

“

of students who drop out; the percentage of high school graduates who

enter four-year colleges; the percentage of graduates who enter any

program of higher education; or the percentage of graduates who obtain

Ld

° ° °

(3 ° ° °®

full-time employment within nine months of completing thelr schooling.

47. These disparities in educational achievement between the

Hartford and suburban school districts are the result of the

education-related policies pursued and/or accepted by the defendants,

:

Ld a

°

.

°

id . .

|

including the racial, ethnic, and socloeconomlc isolation of the

|

|

Hartford and suburban school districts. These factors have already

oe

adversely affected many of the plaintiffs in this action, and will, in

|

the future, inevitably and adversely zffact the education of others.

|

|

I

48. The racial, ethnic, and economic segregation of the Eartford

: ; vo |

and suburban districts necessarily limits, not only the equal @

educational opportunities of the plaintiffs, but their potential |

; : |

employment contacts as well, since a large percentage Ox all emplcyment

growth in the Eartford metropolitan region is occurring in the suburban ®

districts, and suburban students have a statistically higher rake of

success in obtaining employment with many Eartford-area businesses.

19. Public school integration of children in the Eartford »

“re gen : = on i + x]

metropolitan region by race, ethnicity, and econcmic status would

significantly improve the educational achievement of poor and minority

*»

J

-17-

children, without diminution of the education afforded their majority

lsencoinates. Indeed, white students would be provided thereby with the

positive benefits of close associations during their formative years

with blacks, Hispanics and poor children who will make up over 30% of

Connecticut’s population by the year 2000.

C. THE STATE’S LONGSTANDING KNOWLEDGE OF THESE INEQUITIES

50. For well over two decades, the state of Connecticut, through

lits defendant O’Neill, defendant State Board of Education, defendant

Tirozzi, and their predecessors and successors, have been aware of:

(1) the separate and unequal pattern of public school districts in the

state of Connecticut and the greater Hartford metropolitan region; (ii)

the strong governmental forces that have created and maintained

racially and economically isolated residential communities in the

Hartford region and (iii) the consequent need for substantial

educational changes, within and across school district lines, to end

this pattern of isolation and inequality.

51. In 1965, the United states Civil Rights Commission presented

a report to Connecticut’s Commissioner of Education which documented

the widespread existence of racially segregated schools, both between .

- - — Rr.

—

urban and suburban districts and within jpndividual urban school

districts. The report urged the defendant State Board to take corrective acticn. None of the defendants or their predecessors took

appropriate action to implement the full recommendations of the report.

-

—

\

52. In 1965, the Hartford Board of Education and the City Council

hired educational consultants from the Harvard School of Education who

concluded: (i) that low educational achievement in the Hartford

schools was closely correlated with a high level of poverty among the

student population; (ii) that racial and ethnic segregation caused

educational damages to minority children; and (iii) that = plan should

Ibe adopted, with substantial redistricting and interdistrict transfers

funded by the State, to place poor and minority children in suburban

schools.

53, In 1966, the Civil Rights Commission presented a formal

request to the governor, seeking legislation that would invest the

rate Board of Education with the authority to direct full integration

of local schools. Neither the defendants nor their predecessors acted

lto implement the request.

54. In 1966, the Committee of Greater Hartford Superintendents

proposed to seek a federal grant to fund a regional educational

advisory board and various regional programs, one of whose chief aims

would be the elimination of school segregation within the metropolitan

| region.

VE

55. In 1968, legislation supported by the civil Rights Commission

was introduced in the Connecticut Legislature which would have

authorized the use of state bonds to fund the construction of racially

integrated, urban/suburban neducational parks,' which would have been

-19~-

® Hy) @ ( / )

located at the edge of metropolitan school districts, have had superior

PY acadenic facilities, have employed the resources of local universities,

and have been designed to attract school children from urban and

suburban districts. The Legislature did not enact the legislation.

PS 56. In 1968, the defendant State Board of Education proposed

legislation that would have authorized the board to cut off States :

funéing for school districts that failed to develope acceptable plans

|

for correcting racial imbalance in local schools. The proposal offered |

»

|

State funding for assistance in the preparation of the local plans. |

|

|The Legislature &id not enact the legislation.

! 57. Xn 1969, the Superintendent of the Hartford School District

® |

jsalisd for a massive expansion of "project Concern," 2 pilot program |

|

i begun in 1967 which bused several hundred black and Hispanic children

from Eartford to adjacent suburban schools. The Superintendent argued |

® : : :

3 v-

that without a program involving some 5000 students —--— one quarter of

: ‘ 3 :

Zartford’s minority student population == the city of Hartford could

neither stop white citizens from fleeing Hartford to suburban schools |

nor provide quality education for those students Who remained. Project

| concern was never expanded beyond an enrollment of approximately 1,300

s Wm bs

students. In 1988-89, the total enrollment in Project Concern was no

od

1 12 din

more than 747 students, less than 3 percent of the total enrollment 1

the Hartford school system.

®

®

\

:

*

\

.

™

a

r

”

58. In 1969, the State Legislature passed a Racial Imbalance Law,

requiring racial balance within, but not between, school districts.

C.G.S. §10-226a et seg. The Legislature authorized the State

Department of Education to promulgate implementing regulations. C.G.S.

§10-226e. For over ten years, however, from 1969 until 1980, the

Legislature failed to approve any regulations to implement the statute.

59. From 1970 to 1982, no effective efforts were made by

defendants fully to remedy the racial jsolation and educational

inequities already previously jdentified by the defendants, which were

growing in severity during this period.

60. In 1983, the State Department of Education established a

committee to address the problem of "equal educational opportunity" in

the State of Connecticut. The defendant board adopted draft guidelines

in December of 1984, which culminated in the adoption in May of 1986,

of a formal Education Policy Statement and Guidelines Dby the State

Board. The Guidelines called for a state system of public schools

under which "no group of students will demonstrate systematically

different achievement based upon the differences -- such as residence

or race or sex -- that its members brought with them when they entered

an > eer. TL —

school." The Guidelines explicitly recognized ''the benefits of

residential and economic integration in [Connecticut] as important to

the quality of education and personal growth for all students in

Connecticut."

-21-

gl. In 1985, the state Department of Edcuation established an

Advisory Committee to Study Connecticut’s Racial Imbalance Law. In an

interim report completed in February of 1986, the Committee noted the

"strong inverse relationship between racial imbalance and quality

education in Connecticut’s public schools." The Committee concluded

that this was true "because racial imbalance is coincident with

poverty, limited resources, low academic achievement and a high

incidence of students with special needs." The report recommended that

the State Board consider voluntary interdistrict collaboration,

| expansion of magnet school programs, metropolitan districting, or other

| "programs that ensure students the highest quality instruction

I possible.

€2. In January, 1588, a report prepared by the Department of

Education’s Committee on Racial Equity, under the supervision oZ

® defendant Tirozzi, was presented to the state Board. Entitled 13

J eport on Racial/Ethnic Equity and Desegregation in Connecticut’s

-

Public Schools," the report informed the defendant Board that |

® Many minority children are forced by factors related to economic

development, housing, zoning and transportation to live in poor

urban communities where resources are limited. They often have

-i« - available to them fewer educational opportunities. Of equal

significance is the fact that separation means that neither they

nor their counterparts in the more affluent suburban school

® districts have the chance to learn to interact with each other, as !

they will inevitably have to do as adults living and working in 2

multi-cultural society. Such interaction is a most important

element of quality education.

Report at 7.

63. In 1988, after an extensive analysis of Connecticut’s Mastery

Test results, the State Department of Education reported that "poverty,

as assessed by one indicator, participation in the free and reduced

lunch program .- - » [is an] important correlate[] of low achievement,

and the low achievement outcomes associated with these factors are

intensified by geographic concentration." Many other documents

available to, or prepared by, defendant State Board of Education and

the State Department of Education reflect full awareness both of these

6 4 In April of 1989, the State Department of Education issued a

report, "Quality and Integrated Education: Options for Connecticut,"

in which it concluded that

[r]acial and economic isolation have profound academic and

affective consequences. Children who live in poverty -- a burden

which impacts disproportionately on minorities -- are more likely

to be educationally at risk of school failure and dropping out

before graduation than children from less impoverished homes.

Poverty is the most important correlate of low achievement.

belief was borne out by an analysis of the 1983 Connecticut

Mastery Test data that focused on POVEILY « + + The analysis

also revealed that the low achievement outcomes associated with

poverty are intensified by geographic and racial concentrationss

This

feport, at“1.

65. Turning to the issue of racial and ethnic integration, the report put forward the findings of an educational expert who had been

commissioned by the Department to study the effects of integration:

[T]he majority of studies indicate improved achievement for

minority students in integrated settings and at the same time

offer no substantiation to the fear that integrated classrooms

-23=

® »

®

impede the progress of more advantaged white students.

Furthermore, integrated education has long-term positive effects

* on interracial attitudes and behavior . . . .

Id.

66. Despite recognition of the "alarming degree of isolation” of

® poor and minority schoolchildren in the City of Hartford and other |

| urban school systems, Report at 3, and the gravely adverse impact this |

| isolation has on the educational opportunities afforded to plaintiffs

® | and other urban schoolchildren, the Report recommended, and the |

| defendants have announced, that they intend to pursue an approach that

| would be "voluntary and incremental." Report, at 34.

° | 66a. In January of 1993, in response to this lawsuit, defendant |

Governor Lowell Weicker, in his annual state of the state address, |

called on the legislature to address '"[t]lhe racial and economic |

|

jsolation in Connecticut’s school system,' and the related educational |

. inequities in Connecticut’s schools.

|

66b. As in the past, the legislature failed to act effectively |

in response to the Governor’s call for school desegregation |

$ initiatives. Instead, a voluntary desegregation planning bill was

wu GAO CR i

J

“3A

®

[

® ®

*

»

passed, P.A. 93-263, which contains no racial or poverty concentration

goals, no guaranteed funding, no provisions for educational

enhancements for city schools, and no mandates for local compliance. 9

E. THE STATE’S FAILURE TO TAKE EFFECTIVE ACTION

67. The duty of providing for the education of Connecticut

school children, through the support and maintenance of public schools, | 9

has always been deemed a governmental duty resting upon the sovereign |

} “State.

| oe

68. The defendants, who have knowledge that Hartford

schoolchildren face educational inequities, have the legal obligation

| under Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, §1 of the

| Connecticut Constitution to correct those inequities. ®

69. Moreover, the defendants have full power under Connecticut

statutes and the Connecticut censtitution to carry out their

constitutional obligations and to provide the relief to which @

plaintiffs are entitled. C.G.S. §10-4, which addresses the powers and |

duties of the State Board of Education and the State Department of

Education, continues with §10-4a, which expresses "the concern of the @

-l ~state (1y-that each child shall have . . . equal opportunity to receive

J

|

|

»

-0 Bu

*

ar

a suitable program of educational experiences.'" Other provisions of

state law give the Board the power to order local or regional remedial

planning, to order local or regional boards to take reasonable steps to

comply with state directives, and even to seek judicial enforcement of

its orders. See §10-4b. The Advisory Committee on Educational Equity,

established by §10-4d, is also expressly empowered to make appropriate

recommendations to the Connecticut State Board of Education in order

"to ensure equal educational opportunity in the public schools.”

70. Despite these clear mandates, defendants have failed to take

corrective measures to insure that its Hartford public schoolchildren

receive an equal educational opportunity. Neither the Hartford school

district, which is burdened both with severe educational disadvantages

and with racial and ethnic isolation, nor the nearby suburban

districts, which are also racially isolated but do not share the

educational burdens of a large, poverty-level school population, have

been directed by defendants to address these inequities jointly, to

reconfigure district lines, or to take other steps sufficient to

eliminate these educational inequities.

= Ne IY

-2 6m

71. [Withdrawn.]

72. Deprived of more effective remedies, the Hartford school

district has likewise not been given sufficient money and other

resources by the defendants, pursuant to §10-140 or other statutory and

constitutional provisions, adequately to address many of the worst

impacts of the educational deprivations set forth in 9923-27 supra.

The reform of the State’s school finance law, ordered in 1977 pursuant

to litigation in the Horton Vv. Meskill case, has not worked in practice;

adequately to redress these inequities. Many compensatory

services that might have mitigated the full adverse effect of the

constitutional violations set forth above either have been denied to |

|

the Hartford school district or have been funded by the State at levels!

that are insufficient to ensure their effectiveness to plaintiffs and |

other Hartford schoolchildren.

IV. LEGAL CLAIMS

|

FIRST COUNT

|

73. Paragraphs 1 through 34 are incorporated herein DY reference.

ority and non-minority

74. Separate educational systems for min

students are inherently unequal.

ar

= 4 .-

—

75. Because of the de facto racial and ethnic segregation between

‘Eartford and the suburban districts, the defendants have failed to

provide the plaintiffs with an equal opportunity to 2 free public

a Xo

| aefendants and resulting in serious harm to the plaintiffs, the

Jeducation as required by Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth,

§1, of the Connecticut Constitution, to the grave injury of the

plaintiffs.

SECOND COUNT

76. Paragraphs 1 through 72 are incorporated herein by reference.

77. Separate educational systems for minority and non-minority

students in fact provide to all students, and have provided to

plaintiffs, unequal educational cpportunities.

2-8. Because of the racial and ethnic segregation that exists

Hh

fu }

4

| (D

(0

)

ct

(9)

defendants have discriminated against the plaintiffs and have

provide them with an equal opportunity to a free public education as

po I =

required by Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, SI of -

re ah (D

Connecticut Constitution.

|

COUNT TEIRI gu

incorporated herein by reference.

( fu x 79, Paragrapk 1 through. .72

son

80. The maintenance by the defendants of 2a public school district

in the city of Eartford: (i) that is severely educationally

~

disadvantaged in comparison to nearby suburban school districts; (i1)

that fails to provide Eartford schoolchildren with educational

oppertunities equal to those in suburban districts; and (iii) that

DD

falls to provide a majority of Eartford schoolchildren with a minimally

adequate education measured by the State of Connecticut’s own standards

all to the great detriment of the plaintiffs and other Eartford

schoolchildren -- violates Article First, §§1 and 20, and ‘Article

Eighth, §1 of the connecticut Constitution.

FOURTH COUNT PY

8l. Paragraphs 1 +hrough 72 are incorporated herein by

82. The failure of the defendants to provide to plaintiffs =n

other Hartford schoolchildren the equal educational ©

which they are entitled under Connecticut law, including §10-42,

which the defendants are obligated to ensure have been provided,

violates the Due Process Clause, Article First,

Connecticut Constitution.

RELIET

WEEREFORE, for the foregoing reasons, plaintiffs res)

request this Court to:

] Enter a declaratory judgment

a. that public schools in the grester Eartford metropclitan

region, which are segregated de facto by race and ethnicity,

jo X

inherently unequal, to the injury of the plaintiffs,

ars

in violaticn cf

Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, §1 of +he Connecticut

Constitution;

-29-

b. +hat the public schools in the greater Hartford

metropolitan region, which are segregated by race and ethnicity, do not

provide plaintiffs with an equal educational opportunity, in violation

of Article First, §§1 and 20, and Article Eighth, 81, of the

Connecticut Constitution;

c. that the maintenance of public schools in the greatsr

Tartford metropolitan region that are segregated by economic statutes

severely disadvantages plaintiffs, deprives plaintiffs of an egual

educational opportunit and fails to provide plaintiffs with a

; di od -

w

n

w

n

}=

|

minimally adequate education =-- all in violation of Article First,

land 20 and Article Eighth §1, and C.G.S. §10-42; and

@. that the failure of the defendants to provide the

|schoolchildren plaintiffs with the equal educational opportunities to

which they arc entitled under Connecticut law, including §l0-12,

violates the Due Process Clause, Article First, §§8 and 10, of the

Connecticut Constitutien.

2. Issue a temporary, preliminary and permanent injunction,

enjoining defendants, their agents, employees, and SUCCeSSOIS in office

-

from failing to provide, and ordering them to provide:

-r Se vi bc. Viger —

a. plaintiffs and those similarly situated with an

integrated education;

~-30-

® »

| »

*

b. plaintiffs and those similarly situated with equal

educational opportunities;

cz. plaintiffs and those similary situated with a minimally *

adeguate education;

3. Assume and maintain jurisdiction over this action until such

time as full relief has been afforded plaintiffs; ®

4. Award plaintiffs reasonable costs and attorneys’ fees; and

5. Award such other and further relief as this Court deems |

| oe

necessary and proper.

PLAINTIFFS, MILO SHEFF, ET AL.

wb f MI —

| WesleY [W 7. Hortdn

|

MOLLER, HORTON & SHIELDS, P.C.

| 90 Gillett Street |

| Hartford, CT 06105

fi 22-8338

| oe

/ :

RE sop |

/ schoo ot OF CONNECTICUT

School of Law : »

65 Elizabeth Street

r ge : — Hartford, CT 06103

Moa tho hres

Martha Stone ®

CCLU

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

»

TL ERA

RA A bi ET To

oy AT FS

: ’ ” Le ~-

~

Philip D. Tegeler

CCLU

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CT 06106

/

!

ES "ae

Helen Hershkoff

Adam S. Cohen

ACLU

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

Ls WE a

PEE, fo

Marianne Engelman Lado

Theodore Shaw

Dennis D. Parker

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

4

I ITT

; te rd

/ 7 ol 7 ?

< { JF f A " Fi Lod An Wi

‘Sandra Del Valle

Puerto Rican Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

: ; 7

Wilfred Rodriguez( [

NEIGHBORHOOD LEGAL SERVICES

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06102

\

i

ii

te

Vv. : AT HARTFORD

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, ET Al. :

CV 89-03609775

SUPERIOR COURT MILO SHEFF, ET AL.,

Plaintiffs : JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF |

: HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

Defendants : NOVEMBER 25, 1994

REVISED ANSWER TO PLAINTIFFS’

CONSOLIDATED AMENDED COMPLAINT

For their answer to plaintiffs’ Consolidated Amended

Complaint dated February 26, 1993 the defendants offer the 1

|

following:

1: With respect to paragraph 1 the defendants have no

knowledge regarding the first sentence since this reflects the

intention of the plaintiffs. The remainder of the paragraph is

admitted only insofar as it alleges that there is a relatively

© high concentration of children from poor families and black and

+ Latino students in Hartford public school as opposed to the

‘public schools in most of the contiguous or adjacent school

‘districts. Otherwise the paragraph is denied.

A

}

2. With respect to paragraph 2 the defendants have no

LJ knowledge regarding the first sentence since this reflects the

intention of the plaintiffs. The remainder of the paragraph is |

denied.

|

®

4 3. With respect to paragraph 3 the defendants admit only

| that Hartford students as a whole do not perform as well on the

state Mastery Test as do the students as a whole in some

[J ; Cs :

surrounding communities and that poor and minority children have

' the potential to become well-educated. Otherwise the paragraph

is denied.

® |

: 4. Paragraph 4 is admitted only insofar as it alleges that

| the defendants have recognized that society benefits from racial,

° ethnic, and economic integration and that racial, ethnic and

| economic isolation may have some harmful effects, but the

paragraph is otherwise denied.

® k 5. Paragraph 5 is denied except insofar as it encompasses

‘recognized principles of constitutional law.

am } i. no

® £

|

| -2-

|

|

.

hl

II. PARTIES |

A.» PLAINTIFFS ae

6-12. Paragraphs 6 through 12 are admitted.

!

| 13. Paragraph 13 has been withdrawn and requires no »

| answer.

i 14-23. Paragraphs 14 through 23 are admitted.

.

1 B. DEFENDANTS

: 24. Paragraph 24 is admitted insofar as it alleges that

{William O'Neill or his successor is the Governor and insofar as ®

Hit correctly describes the legal responsibilities of the Governor

under the mentioned statutes, but is otherwise denied.

’

x 55, Paragraph 25 is admitted.

| 26. Paragraph 26 is admitted insofar as it alleges that Che

named individuals were, at one time, the members of the State *

Sian Board of Education and insofar as it alleges that these

i ¥

|

*

| -3 =

@

® »

»

individuals have been succeeded by others as members of the State |

® Board of Education. The paragraph is also admitted insofar as it |

alleges that the State Board of Education as a whole has

responsibilities as defined by law. |

® l

} 27. Paragraph 27 is admitted insofar as it alleges that

|cerald N. Tirozzi or his successor is the Commissioner of

| Eaucation and insofar as it correctly describes the legal

. i responsibilities of the Commissioner under the mentioned

statutes, but is otherwise denied.

PY i 28. Paragraph 28 is admitted insofar as it alleges that

Francisco I.. Borges or his successor is the Treasurer and insofar

is it correctly describes the legal responsibilities of the

® Treasurer under the law, but is otherwise denied.

| 29. Paragraph 29 is admitted insofar as it alleges that J.

‘Eaward Caldwell or his successor is the Comptroller and insofar

» las it correctly describes the legal responsibilities of the

conproliel under the law, but is otherwise denied.

gE] | Sea -

®

|

| -4-

.

*

III. STATEMENT OF FACTS

|

A. A SEPARATE EDUCATION | ®

|

| 30. Paragraph 30 is denied insofar as it alleges that

|

H

: i]

\lschool districts in the state are “segregated by race and ethnic

i.

origin.” It is admitted only insofar as it alleges that some

school districts, including Hartford, serve higher percentages of

African American and Latino students than others, but is

? : ®

‘otherwise denied.

31. Defendants admit that in 1986 12.1% of the school

‘population was black and 8.5% was Hispanic. Since the defendants ®

are not aware of the sources of the other figures presented in

‘paragraph 31 or the methods used by the plaintiffs to develop

‘those figures the defendants lack sufficient knowledge Or ®

‘information to form an opinion as to the truth of the other

‘matters contained in this paragraph and leave plaintiffs to their

proof. The defendants note that the court has received into 3

evidence the Minority Students and Staff Report for 1986-87 and

| ®

| Se

|

!

|

oe

»

®

the defendants admit that the numbers contained in that report

» are accurate. Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 119. |

32. Paragraph 32 is denied. |

® | 33. Paragraph 33 is denied except that the figures for |

total school population and percent minority for the towns which

are listed are admitted.

» :

34, Paragraph 34 is denied except that the number of staff

lin the listed towns for the 1986-87 school year is admitted.

| Furthermore the minority percentages are admitted, except for the

® percentages given for West Hartford and Wethersfield. The

"correct percentage for West Hartford is 1.8% and the correct

pevcentage for Wethersfield fe 1.9%) The defendants wish to note

* that the Minority Student and Staff Report for 1986-87 has been

admitted into evidence as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 119 and the

defendants admit that the numbers contained in that report are

» | accurate.

I

i -%-

H ;

* ]

B. AN UNEQUAL EDUCATION

35. Paragraph 35 is denied except insofar as it alleges

that the Hartford schools serve a greater proportion of students from backgrounds that put them “at risk” of lover educational

|

lachievement than the identified suburban towns and that, as a

result, Hartford has a comparatively larger burden to bear in

{ : :

addressing the needs of ”at risk” children.

} 36. Paragraph 36 is denied insofar as it alleges that

Hartford school children are being denied the right to equal

ieducational opportunity. The paragraph is admitted insofar as it

alleges that ”at risk” children have the capacity to learn and

{insofar as it alleges that “at risk” children may impose some

‘special challenges to whatever school system is responsible for

providing these children with an education. Otherwise the

paragraph is denied.

! 1

37. Paragraph 37 is admitted insofar as it identifies some

indicia of ”at risk” students and insofar as the figures listed

TT

{

ii

|

{

i

|

|

i

|

| |

|

| !

]

i

®

in this paragraph are consistent with the figures reported in

eo Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 120. Otherwise the paragraph is denied.

38. Paragraph 38 is denied.

| |

* l 39. Paragraph 30 is admitted only insofar as it alleges

! that Hartford students as a whole do not perform as well on |

measures of achievement like the State Mastery Test as do the

» ‘students as a whole in some surrounding communities. Otherwise

the paragraph is denied.

40. Paragraph 40 is admitted except insofar as it attempts

” to characterize the purpose of the Mastery Test. The purposes of

the Mastery Test are accurately described in the Mastery Test

reports found in Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 290-308 and, to the extent

® tehat the plaintiffs’ description of the Mastery Test differs, it

‘is denied.

° 41. Paragraph 41 is admitted only insofar as it is

consistent with the description of the levels of performance on:

a - y — a

|

» |

I

| =

o |

» .

1.

|

. . . . . . |

the Mastery Test described in Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 290-308.

Otherwise the paragraph is denied.

ey

42. Paragraph 42 is admitted insofar as it alleges that i

ll Hartford students as a whole do not perform as well on the State

Mastery Test as do the students as a whole in some surrounding *

| communities. The particular performance levels of Hartford and

| suburban children as alleged in this paragraph are admitted only

insofar as the figures appear in Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 297, 2938 °

‘and 299. Otherwise the paragraph is denied.

43. Paragraph 43 is admitted insofar as the figures which

| appear in this paragraph are identical to figures found in »

i Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 297, 298 and 299. Otherwise the paragraph

ig. denied.

: ; : : »

44. Paragraph 44 is admitted insofar as the flgures which

appear in this paragraph are identical to figures found in

Plaintiffs’ Exhibits 297, 298 and 299. Otherwise the paragraph

ih LJ

1s denied.

SARI i; % Ling 00 —

|

*

| =2=

|

|

1

®

45. Paragraph 45 is denied insofar as it alleges that

Hartford children are not receiving an education which satisfies

the requirements of the constitution. The paragraph is admitted insofar as it alleges that the defendants are not satisfied with

the performance of Hartford school children as a whole or of any

|

|

|

i

i

i

iichildren who perform below the mastery level.

{|

46. Paragraph 46 is admitted only insofar as it alleges

1]

1

‘that there are some differences between Hartford students taken

ias a whole and students as a whole in some of the surrounding

| communities in terms of the number who drop out before

graduation, the number who enter four year colleges and other

programs of higher education, and the number of others who obtain

|

full time employment within nine months of graduation. Otherwise

the paragraph is denied.

+

1s

id

47. Paragraph 47 1s denied.

| 48. The defendants lack the knowledge and information

necessary to form a conclusion as to the truth of the allegation

§ — —

' contained in paragraph 48 and leave plaintiffs to their proof,

-10-

except insofar as the paragraph alleges or implies that the