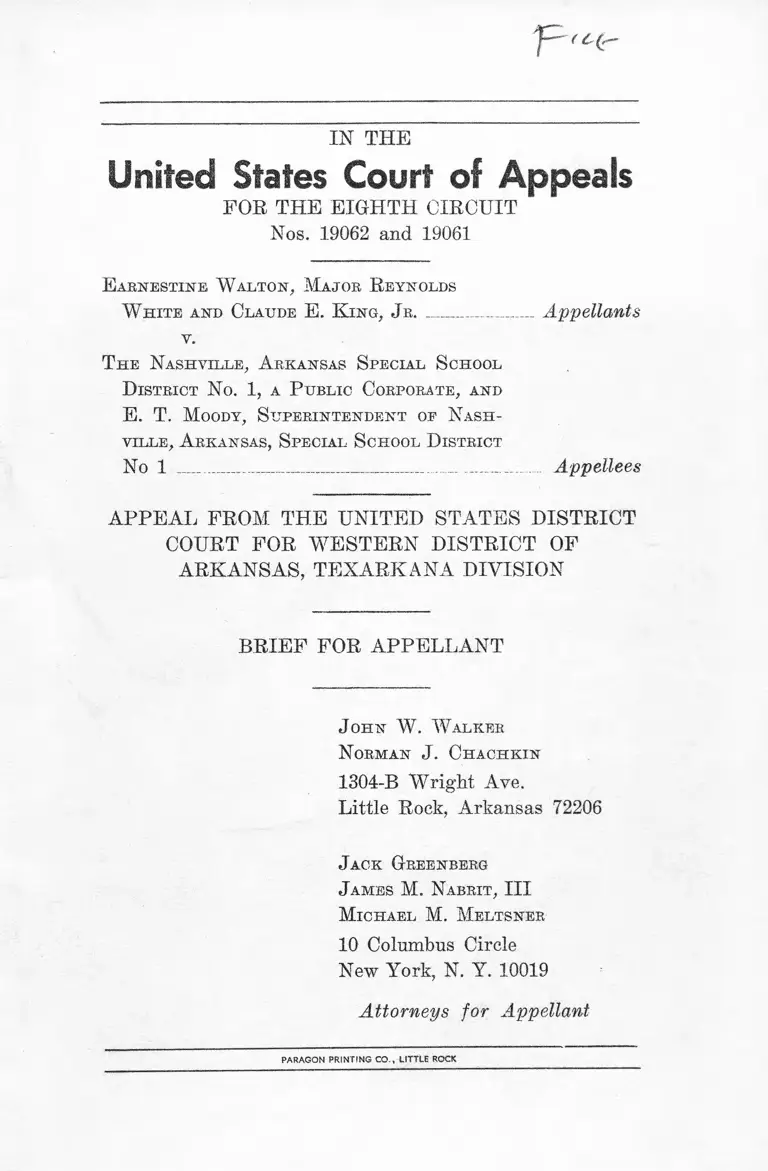

Walton v. Nashville Arkansas Special School District No. 1 Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 23, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walton v. Nashville Arkansas Special School District No. 1 Brief for Appellant, 1968. fc83536c-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/23f416bb-0c50-4265-89c8-31c34b5dd814/walton-v-nashville-arkansas-special-school-district-no-1-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

p ^

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

POE THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 19062 and 19061

E arn estin e "Walton , M ajor R eynolds

W h ite and Claude E . K ing , J r. ___________ Appellants

v.

T h e N ash ville , A rkansas S pecial S chool

D istrict N o. 1, a P ublic C orporate, and

E . T . M oody, S u perintendent oe N ash

ville , A rkansas , S pecial S chool D istrict

No 1 ___________________________ __________ Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR WESTERN DISTRICT OF

ARKANSAS, TEXARKANA DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

J ohn W. W alker

N orman J . C h a c h k in

1304-B Wright Ave.

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

J ack G reenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

M ichael M . M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

PARAGON PR INT IN G CO., LITTLE ROCK

I N D E X

Page

Statement of Case --------------------------------------------------------------------- 1

Statement of Points To Be Argued ------------------------------------------- 13

Argument --------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 16

I. Appellees’ Termination of Major Reynolds White was

basically unfair and racially motivated in violation of

the due process and equal protection of the laws

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment ---------------------------- 16

II. Appellees termination of Appellants without making

the required objective evaluation of their qualifica

tions in comparison with all other teachers in the

system violated Appellees plan of desegregation and

otherwise deprived Appellants of equal protection of

the law s_______________________________________________- 22

III. Because of Appellees unconstitutional treatment of

Appellants and because of Appellees refusel to comply

with their desegregation plan, Appellants are entitled

to the relief of reinstatement, damages, attorneys fees,

costs; or appropriate alternative relief -------------------- ------- 30

Conclusion ------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------ 3^

TABLE OF CASES

Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545 (1965)------------------------------------- 18

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F.2d 862 (5 Cir. 1962) 21

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Va., 321 F.2d 494

(4 Cir. 1963)_______________________ ______ _________________ 30

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (4 Cir. 1965)— 20

Brooks v. School Dist. of City of Moberly, 267 F.2d 733 (8

Cir. 1959) _______________________________________________ 17, 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)------------------------ 20

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Educ., 364 F.2d 189

(4 Cir. 1966)______________________________________________17. 19

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F.2d 661 (8 Cir. 1965) — 21

In Re Gault, _____U.S— _ _ --------S.Ct--------- , 18 L.Ed. 2d

527 (1967) ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 16

INDEX (Continued)

Page

In Re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948)________________________________ 18

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F.2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966) __________________ 24

Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F.2d 483 (8 Cir. 1967) ________________ 31

Rios v. Hackney, Civ. No. CA-3-1852 (N.D. Tex., Nov. 30, 1967)._„ 20

Rogers v. Paul 382 U.S. 198 (1965) ____________________________ 20, 23

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) _________________-_________ 16

Slochower v. Board of Educ. of N.Y., 350 U.S. 551 (1956) --------- 18

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F.2d 770 (8 Cir. 1965) 17, 20

Sperser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958)------------------------------------- 18

Stell «. Savannah-Chatham Board of Educ., 333 F.2d 55 (5

Cir. 1964) ___________________________________ _______________ 21

Wall v. Stanly County Board of Educ.-------F .2 d _ — (4 Cir. 1967) 30

Yarbrough v. Hulbert—West Memphis School Dist. No. 4, 380

F.2d 962 (8 Cir. 1967) — _____________________________ ____— _ 29

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment

28 U.S.C., Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ------------ 26

OTHER AUTHORITY

Note, discrimination in the hiring and assignment of teachers

in the public school systems, 64 Mich. L.R. 692 (1966)------------ 30

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

FOE THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 19062 and 19061

E AR N E S T IN E W A L T O N , M a JO R R E Y N O L D S

W h ite and Claude E. K in g , Jr. ___________Appellants

v.

T h e N ash ville , A rkansas S pecial S chool

D istrict N o. 1, a P ublic C orporate, and

E. T. M oody, S u perin ten den t oe N ash

ville , A rkansas, S pecial S chool D istrict

No 1 _______________________________________ Appellees

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT

COURT FOR WESTERN DISTRICT OF

ARKANSAS, TEXARKANA DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Number 19062 is an appeal from a judgment of the

District Court for the Western District of Arkansas, Tex

arkana Division, denying injunctive relief, reinstatement,

damages and attorney’s fees sought by Negro plaintiffs-

appellants following their discharge as teachers by the

appellees, Nashville, Arkansas Special School District No.

1 and Nashville Superintendent E. T. Moody. Plaintiffs-

Appellants had filed suit challenging the legality of their

dismissals under the due process and equal protection of

the laws clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

United States Constitution. Number 19061 is an appeal

taken on behalf of Negro plaintiffs-appellants against the

same appellees from the order of the district court deny

ing their prayer to have the all-Negro Nashville school

closed because it is inferior and inadequate. These ap

pellants move to dismiss this aspect of their appeal on the

ground that, on information and belief, said school will

be closed at the end of the current school term and the

Negro pupils assigned to the existing and superior pre

dominantly white schools operated by appellee school

district. A summary of previous litigation involving ap

pellees is set out below to place this entire matter in per

spective.

I. histoky :

Through the 1965-66 school term the boundaries of

the Nashville Special School District No. 1 and the

Childress Special School District No. 39 overlapped cover

ing substantially the same geographic territory (R.4).

Nashville’s faculty, staff and student body were all white;

likewise, Childress’ faculty, staff and student body were

all-Negro (R.6).

E. T. Moody, a white person, was superintendent of

Nashville Schools; Tommy Walton, a Negro, was super

intendent of Childress Schools (R.6). Moreover, school

taxes were assessed and assigned to each school district

on a racial basis (R.4). Nashville’s school system had

the North Central Association’s highest accreditation;

Childress, a much smaller and poorer school system, was

unaccredited by North Central and merited only a “ C ”

rating from the Arkansas State Education Department (E.

98).

In 1965, both school districts represented to the De

partment of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW ) 'that

they were in compliance with that body’s regulations on

school desegregation promulgated pursuant to the Civil

Rights’ Act of 1964, in that each district was educating

all pupils within its boundaries without discrimination.

Accordingly both districts continued to receive federal

financial assistance (E.5, 21, 22).

On December 20, 1965, Negro pupils filed suit chal

lenging the legality of overlapping districts established on

the basis of race. They also sought to establish their

right to attend Nashville public schools, on a desegregated

basis; and to have the Nashville district adopt and im

plement a comprehensive plan of desegregation. Their

suit resulted in a stipulation for dismissal, approved by

the district court on March 3, 1966, pursuant to the adop

tion of a desegregation plan (E.4-10, 28) which, among

other things, provided:

(1) That the Childress School District would cease

to exist on June 30, 1966;

(2) That the Nashville School District would assume

responsibility for providing education for all pupils re

siding within the Nashville district beginning on July 1,

1966;

(3) That the Nashville School District would assume

the obligations, assets and liabilities of the Childress

School District as they existed on June 30, 1966;

(4) That the district would move toward the estab

lishment of a unitary school system by implementing a

4

limited, freedom of choice plan at the start of the 1966-67

school term; and

(5) That the district would take steps to insure that

faculty desegregation was achieved and that in the pro

cess,

“ Teachers and other professional staff will

not be dismissed, demoted, or passed over for re

tention, promotion, or rehiring, on the ground of

race or color. If consolidation of the Nashville

and Childress districts and the unification of the

schools result in a surplus of teachers, or if for

any other reason related to desegregation it be

comes necessary to dismiss or pass over teachers

for retention, a teacher will be dismissed or passed

over only upon a determination that his qualifica

tions are inferior as compared with all other teach

ers in the consolidated system” (E.10).

After the Court decree, Appellees made no effort to

communicate their desegregation plans to the Negro teach

ers (E.44).

II. T E R M IN A T IO N OE M A JO R REYN OLDS W H IT E :

During the 1965-66 school term, the Childress School

District offered a full school program for grades one

through twelve. Consequently, appellants and a number

of other Negroes were employed as teachers; Tommy

Walton was the Superintendent of the Childress district.

Appellant Major Eeynolds White taught high school social

studies during 1965-66; appellant Earnestine Walton

taught high school home economics; and appellant Claude

E. King, Jr., taught high school agriculture (E.18).

Near the close of the 1965-66 school term, pursuant to

the Court approved freedom of choice plan, a large num

ber of Negro pupils chose to transfer to the white Nash

ville schools. Consequently, Nashville decided to reduce

the faculty of Childress by at least one teacher. For as

Superintendent Moody stated: “ We knew that we were

going to have to hire some of them [Negro teachers] and

we studied their transcripts of the ones we had available”

(R.116). The teacher eliminated was Major Reynolds

White (R.24).

Although Nashville was not to assume operational

control of the Childress School (later renamed as the

Southside School) until July 1, 1966, the Nashville Board

and Superintendent began to screen the Negro teachers in

May of 1966 by viewing and studying their transcripts

(R.116, 149, 150). Nashville Superintendent Moody

asked the Childress Superintendent Walton to furnish

copies of the transcripts of the Childress-Southside teach

ers. No such request was made of the white Nashville

principal, and Mr. Moody gave Mr. Walton no explanation

for his request (R.115). Later in the year at a Childress-

Southside faculty meeting, Mr. Walton announced that fac

ulty members should provide copies of their transcripts for

“ the office” . He did not advise the teachers that the

transcripts were wanted by Mr. Moody nor of the pos

sible consequence of failure to produce the transcripts:

retention or dismissal (R. 73, 74, 76, 115). Mr. Moody did

not have any direct communication with the Negro teach

ers about the contemplated faculty reduction or the

necessity for Negro faculty members to provide Nashville

with copies of their transcripts (R.74).

Apparently, Major Reynolds White was the only

Negro teacher whose transcript was not on file. How

ever, copies of his transcripts were on file in the County

5

6

Board of Education and the Arkansas State Education

Department.1 Although Mr. White made prompt efforts

to obtain copies of his transcript from Philander Smith

College (where he obtained his B. A. degree) and from

the University of Arkansas graduate school, and explained

to Mr. Walton that May was a very busy month for colleges

and that delay was to be expected, (R.74), he was term

inated by appellees on or about June 2, 1966 for the reason

that he did not provide the district with copies of his

transcripts. It was not until on or about June 12, 1966

that he received the requested copies of his transcript.

After his termination, Mr. White sought unsuccessful

ly to have the Nashville Board reconsider their decision

to terminate his employment (R.75, 103). The Board

did not advise Mr. White of any vacancies which occurred

in the system nor give him an opportunity to return to

Nashville as a teacher if he qualified for any such vacan

cy (R.119). Mr. White obtained employment as a sub

stitute teacher in the nearby Prescott School District dur

ing the 1966-67 school term (R.81).2

During the summer of 1966, a position as social

studies teacher at the Southside School became vacant for

the 1966-67 school year. Although this is the subject

that Major White had taught, neither the Nashville Sup

erintendent nor the Board considered rehiring Mr. White.

Nor did Nashville consider employing or assigning a

white teacher to fill the vacancy (R.117, 118). Conse

1 The District was aware that Mr. White was a college gradu

ate properly licensed and certified by the State of Arkansas. Mr.

White is a graduate of Philander Smith College who had at time

of trial, nine graduate hours of study at the University of Arkansas.

He has teaching experience of ten years, all but two in the Childress

School District (R. 70, 71, 72, 75).

2 At the time of trial, August 17, 1967, Mr. White had not

obtained another teaching position (R.86).

quently, the Negro pupils at Southside were completely

deprived of a social studies teacher for more than a

month (R.30, 31, 67), and then “ kept” by a Negro teach

er, four years retired, for about two months (R.68). The

superintendent “ thought she would be better than noth

ing” (R.117). It was not until December of 1966 that

those Negro pupils were afforded the benefit of a com

petent teacher, Artka Shaw3, who, himself, was terminated

at the close of the school year (R.30, 32, 33, 94).

During the summer of 1966, subsequent to Mr. White’s

termination, a vacancy occurred in the white elementary

school. Mr. Moody did not consider Mr. White for that

vacancy because he “ didn’t think Major would be in

terested in a first grade job ” (R.119).

The district court upheld appellees’ termination of

Mr. White on the grounds that:

1. Mr. White was “ requested [by appellees] to fur

nish certain information” and that he did not do so;

2. the appellees followed “ well adopted and well-

known procedures” in terminating him: and that

3. the appellees did not abuse. their authority (R.

160, 161).

I l l T H E D ISM ISSALS OE A P P E L L A N T S :

During the freedom of choice period held by Nash

ville near the close of the 1966-67 school term, most of the

Negro pupils then attending Southside School in grades

3 However, Mr. Shaw was a beginning teacher without ex

perience and without graduate training (R.107). Compare Mr.

White’s paper qualifications, (R.71-73) and cf. R.20 where Mr. Moody

states that he didn’t know whether Mr. White was more or less

competent than Mr. Shaw.

8

nine through twelve made choices to transfer to the pre

dominantly white Nashville high school. Nashville then

decided to abolish those grades at Southside and to as

sign the Negro pupils therein to the Nashville High School

for the 1967-68 school year (R.33).

After deciding to close the top four grades at South-

side, Nashville decided to reduce Southside’s faculty and

staff. As Mr. Moody stated: “ . . . I talked to them [the

Negro teachers] individually, privately, that we were go

ing to have to abolish some of the positions down there,

and there wouldn’t be as large a faculty as we had . . . ”

(R.127). Consequently, the Negro principal, who had

formerly been superintendent of Childress before the

court decree, was terminated as were his wife, Earnestine

Walton, the home economics teacher; Claude E. King, Jr.,

the agriculture teacher, and Altha Shaw, the social

studies teacher who had filled the vacancy created by the

termination of appellant Major Reynolds White (R.33).

The Secretary of the Nashville Board stated that had a

greater number of Negro pupils chosen to attend South-

side, the dismissed Negro teachers ‘ ‘ would have [been]

retained . . . in the system” (R.39).

The Negro high school coach and physical education

instructor, Prentiss Counts, was reassigned from the high

school to the Southside elementary school. He was not

considered for a coaching position in the white high school

(R.128, 129) although two coaching positions, one of head

coach and the other of assistant coach, became vacant

there during the summer of 1966, (R.37, 129). The former

assistant coach was promoted to the head coaching posi

tion. The assistant coach named, a Mr. Dale, was new

to the Nashville system (R.38). Superintendent Moody

defended Nashville’s action by stating: “ He [Counts]

9

couldn’t fill that position anyway . . . that is a football

position and he is a basketball coach, has no experience in

football” (R.130). Southside never had a football pro

gram.

Shortly after the close of the 1966-67 school year

Superintendent Moody retired. Nashville then created

the position of coordinator of federal projects and named

Mr. Moody to fill it (R.110). Mr. Moody’s successor as

superintendent was the principal of the Nashville High

School, Mr. Jones. Mr. Jones’ successor as principal

was the white agriculture teacher, Mr. Stavely (R.36).

Although at least six vacancies (superintendent, principal,

agriculture teacher, coach, assistant coach, and the vacan

cy created by the assistant coach moving up to coach (R.

32-39) occurred in the Nashville system shortly after the

close of the 1966-67 school term, appellees neither serious

ly considered any of the dismissed Negro teachers for

either vacancy; nor did appellees encourage or even ad

vise the dismissed teachers to reapply, and that if they

did so, that they would be given the first opportunities to

fill those or other vacancies which occurred within the

system (R.38).

A. The Cases of Tommy Walton and Altha Shaw:

Tommy Walton was principal of Southside during

1966-67. Nashville was aware that Mr. Moody would

be retiring at the close of the 1966-67 school year and that

Mr. "Walton had previous experience as a school superin

tendent. However, Nashville’s Board did not consider

Mr. Walton for the position of superintendent. Like

wise, after the decision was made to promote the white

principal to the superintendent’s post, the Nashville Board

did not consider Mr. Walton for the position of principal

of Nashville high school although he had previous ex

10

perience as a high school principal. Moreover, Nash

ville’s school construction plans promise reorganization

of the school system so that at the beginning of the 1968-

69 school year, a junior high school principal will be

needed (R.49, 50). However, Mr. Walton was not ad

vised that he will be considered for the junior high vacancy

when it occurs. Nor that he could apply for it. Nor were

his qualifications compared with those of the white ele

mentary principal (R.123). Despite the fact that Mr.

Walton had a good academic background (R.97), Mr.

Moody testified that, “ we didn’t consider Mr. Walton

for any position” (R.122). (cf. also (R.39). [Discus

sion of the facts surrounding Altha Shaw’s dismissal is

omitted.] Mr. Walton and Mr. Shaw did not appear for

trial and their action was dismissed by counsel.

B. The Case of (M rs.) Earnestine Walton:

Appellant Earnestine Walton taught home economics

in the Southside school during the 1966-67 school term (R.

99). Although Mrs. Marie Stavely, home economics

teacher at the white high school, had considerably more

experience than Mrs. Walton (R.100), neither Mr. Moody

nor the Nashville Board made a careful, detailed com

parison of their qualifications. Nor clid appellees ob

jectively compare Airs. Walton’s qualifications with those

of all other teachers in the system (R.130, 44, 125, 126,

143, 149). Further, although at least one white ele

mentary teacher resigned during the summer of 1967, and

although a number of teachers were teaching outside their

fields of study (R.124, 125, 135) neither Mrs. Walton nor

the other Negro teachers were offered the opportunity to

fill this vacancy. Only white applicants were considered

(R.33, 34). The reason given for not offering this po

sition to either displaced Negro teacher was that an

elementary certificate was required and they held high

11

school certificates (R.34). This reason did not prevent

appellees from assigning Prentiss Counts from the Negro

high school to the Negro elementary school (R.128).

The district court in upholding appellees’ termina

tion of Mrs. Walton stated:

The Court is concerned with this provision

which requires that a termination be made on the

basis of qualifications which are inferior as com

pared with all other teachers . . . The Court is only

concerned as to whether or not there was a com

parison made and a determination upon the basis of

the qualifications of one person as against an

other person. [But see R.130, and discussion,

supra]. The evidence is very clear that the ac

tion by [appellees] . . . was with well-established

procedures on the basis of comparison of quali

fications.

. . . the party who has the position that Mrs.

Walton is interested in had some fifteen years

[experience] . . . (R.160).

C. The Case of Claude E. King, Jr. :

Appellant King taught vocational agriculture during

the 1966-67 school year at the Southside high school (R.

55). At the close of the school year, when he was

terminated by appellees, Mr. King obtained work as a

truck driver. This was not customary summer employ

ment for him, for vocational agriculture teachers were

employed on a twelve month basis (R.55). (Mr. King

was thus not employed by Nashville for a period from

July 1, 1967, through at least the date of the trial, August

17, 1967.)

12

At the time Mr. King was terminated, appellees did

not compare his qualifications with those of all other

teachers in the system (K.36, 103). Mr. Herman Stavely,

the white vocational agriculture teacher who was re

tained through the school year, was made principal of

the Nashville high school during the summer of 1967

(R.58). Although Mr. King had taught in the system

previously he was neither hired nor given the first op

portunity to fill the vacancy created by Mr. Stavely’s

promotion (R.58, 59, 62, 130, 131). Instead, a Mr. Dugan

who was new to the system filled that vacancy (R.131).

In fact, the need for a second agriculture teacher was

occasioned by the large number of Negro pupils who pre

registered during the summer for vocational agriculture

(R.131). It was only after this action was filed and went

to trial that appellees officially offered Mr. King the

opportunity to fill the second vacancy in the agreiulture

department (R.55).

The district court took the position that the appellees’

offer of employment to Mr. King should satisfy his com

plaint. The court did not consider the issue of dam

ages which Mr. King sustained, costs, attorneys’ fees, nor

the legality of Mr. K ing’s termination (R.159).

Judgment was entered on August 23, 1967, by the

Honorable Oren E. Harris, District Judge, dismissing the

complaint on the condition that defendants tender Claude

E. King, Jr., a contract for the 1967-68 school term.

Notice of appeal was filed on September 14, 1967 (R.

167).

POINTS TO BE RELIED ON

Appellees termination of Major Reynold White was bas

ically unfair and racially motivated in violation of the

due process and equal protection of the laws clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770 (8

Cir. 1965)

Brooks v. School Dist. of City of Moberly, 267 F. 2d 733

(8 Cir. 1959) cert, den., 361 U.S. 894 (1959)

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Educ., 364 F.

2d 189 (4 Cir. 1966)

In Re Gault, ______U.S. _______ , ______ S. Ct. ______ , 18

L. Ed. 2d 527 (1967)

Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545 (1965)

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5 Cir. 1962)

Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382 U.S. 103 (4

Cir. 1965)

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955)

Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little Rock, 369 F. 2d 661 (8

Cir. 1965)

In Re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948)

14

Rios v. Hackney, Civ. No., CA-3-1852, (N.D. Tex. Nov. 30,

1967)

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960)

Slochower v. Board, of Educ. of N. J ., 350 U.S. 551

(1956)

Speisef v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 (1958)

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Board of Educ., 333 F. 2d

55 (5 Cir. 1964)

i i

Appellees termination of Appellants Walton and King

without making the required objective evaluation of

their qualifications in comparison with all other

teachers in the system violated Appellees plan of

desegregation and otherwise deprived Appellants of

equal protection of the laws.

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770 (8 Cir.

1965)

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Educ., 364 F.

2d 189 (4 Cir. 1966)

Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly, 267 F. 2d

733 (8 Cir. 1959)

Franklin v. County School of Giles County, 360 F. 2d 325

(4 Cir. 1966)

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F. 2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966)

Rogers v. Paid, 382 U.S. 192 (1965)

TFoM v. Stanly County Board of Educ. - ....-....F. 2 d ----------

(4 Cir. 1967)

Yarbrough v. Hulbert-West Memphis School Dist., No. 4

380 F. 2d 962 (8 Cir. 1967)

28 U.S.C. Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

O TH E R A U T H O R IT Y

Note, Discrimination in the Hiring and Assignment of

Teachers in the Public School Systems 64 Midi. L.R.

692 (1966)

h i

Because of Appellees unconstitutional treatment of A p

pellants and because of Appellees refusal to comply

with . their desegregation plan, Appellants are en

titled to the relief of reinstatement, damages, at

torneys’ fees, costs; or appropriate alternative relief.

Bell v. School Board of Powhatan County, Va., 321 F. 2d

494 (4 Cir. 1963)

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770, (8

Cir. 1966)

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of Educ., 364 F. 2d

189 (4 Cir. 1966)

Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F. 2d 483 (8 Cir. 1967)

Johnson v. Branch, 364 F. 2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966)

16

ARGUMENT

i

Appellees termination of Major Reynold White was bas

ically unfair and racially motivated in violation of the

due process and equal protection of the laws clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Major Reynolds White had been employed by the all-

Negro Childress School District for seven years as a

social studies teacher. His qualifications as a teacher

had never been questioned. He was licensed as a teacher

by the state Department of Education and the County

Board of Education. Both agencies required a tran

script as a condition for licensing a teacher. In antici

pation of the merger of the two districts lying within the

same geographic territory, the all-white Nashville Board

and its superintendent, E. T. Moody, decided in May of

1966 to reduce the Childress faculty by one because of the

large number of Negro pupils who exercised “ freedom of

choice” to attend the white schools (R.29). Mr. Moody

then requested Mr. Tommy Walton, superintendent of

Childress (later principal of Childress when it was ab

sorbed by Nashville and renamed Southside) to provide

him copies of transcripts of all the Negro teachers. Mr.

Moody had copies of transcripts of white teachers from

previous years. Mr. Moody did not advise Mr. Walton

(who -was then Mr. Moody’s equal) of the uses to which

the transcripts would be put nor did he advise him that

faculty reduction was contemplated. In turn, neither did

Mr. Walton so advise his teachers. Thus, Mr. White

did not know what appellees expected him to do to main

tain his position as a teacher, [of. Shelton v. Tucker 364

U.S. 479, 486, 487 81 S. Ct. 247, 5 L. Ed 2d 231 (I960)].

17

Mr. White was apparently the only teacher for whom

there was not a transcript on file with Mr. Walton and

by the time he obtained copies of his transcripts from

his colleges, he had been terminated for the very reason

that he had not produced them before June 2, 1966, prior

to the date appellees were to assume control of the

Childress School. Moreover, the only criterion used by

appellees to make a comparative determination between

the Negro and white teachers of their qualifications was

whether or not, as of May 1966, a teacher’s transcript was

in the hands of Mr. Moody. Clearly this criterion could

only apply to Negro teachers for Mr. Moody knew that

all of the white teachers in Nashville had transcripts on

file. Thus, the criterion was based on the prohibited

basis of race. Smith v. Board of Education of Morrilton,

365 F. 2d 770 (8 Cir. 1965). Further support for this

conclusion is seen in appellees belief that faculty reduc

tion was necessary because of the transfers of the Negro

pupils from the Negro high school to the white high school.

Appellees specific termination of Mr. White was based

and defended solely on the grounds that Mr. Moody had

not been provided with a copy of Mr. White’s transcript.

This is certainly not the ebjective evaluation re

quired, Brooks v. School District of Moberly, 267 F. 2d

733, 736 (8 Cir. 1959), cert, den., 361 IX.S. 894; Chambers

v. Hendersonville City Board of Education, 364 F. 2d 189

(4 Cir. 1966), especially when coupled with the facts that

appellees never gave Mr. White notice that his transcript

was needed, or wanted for the purpose of objectively eval

uating teachers to determine which teachers would be

retained or released; nor gave him an opportunity to ex

plain difficulties experienced in attempting to obtain it

from his colleges. Nashville’s failure to give Mr. White

adequate notice of appellees requirements for continued

18

employment in the district or to grant him a pre-termina

tion hearing under the circumstances constituted depriva

tion of his livelihood1 without due process of law. In

Re Gault, ____ U.S. ____, ____ S. Ct. ____, 18 L. Ed. 2d

527, 549 (1967); Armstrong v. Manzo, 380 U.S. 545, 85 S.

Ct. 1187, 14 L. Ed. 2d 62, (1965), Speiser v. Randall, 357

U.S. 513, 78 S. Ct. 1332, 2 L. Ed. 2d 1460 (1958); Re

Oliver, 333 U.S. 257, 68 S. Ct. 499, 92 L. Ed. 682 (1948);

Slochower v. Roard of Educ. of N. Y., 350 U.S. 551, 76

S. Ct. 637, 100 L. Ed 692 (1956).

The basic unfairness and racial motivation of ap

pellees in their termination of Mr. White is seen in the

events which follow his termination. After appellees

notified Mr. White that his contract would not be renewed,

Mr. White went before them with his transcripts, sought

and received an audience of sorts, but was neither rein

stated nor advised that, in the event of a later vacancy in

the system he would be considered for it. During the

summer of 1966, at least two vacancies occurred in the

system — one in the white elementary school; the other

in the Southside (Negro) school. Only white applicants

were considered for the elementary position. Mr. White

was not considered because Mr. Moody “ didn’t think

Major would be interested in a first grade job ” (R.119).

Ironically, the Southside vacancy was for a social

studies teacher, the position occupied by Mr. White during

the previous years. Instead of contacting Mr. White to

ascertain his availability to fill it, appellees left the po

sition unfilled for more than a month after school began;

and it was more than three months before a competent,

qualified Negro teacher was named to fill the vacancy.

i Ones’ livelihood is just as important, in many circumstances

as his life, liberty or property and indeed involves them all.

19

Appellees did not consider filling the vacancy with a white

teacher (R.117, 118), despite their commitment of March

3, 1966 that “ Race or color will henceforth not be a factor

on the hiring, assignment, reassignment, promotion, de

motion, or dismissal of teachers . . . (R.9).

These factors, coupled with others,2 constitute ‘ ‘ pos

itive evidence” that appellees (1) were influenced by im

proper racial considerations in the matter of employing,

retaining and reassigning teachers, Brooks v. School Dis

trict of Moherly, Missouri, 267 F. 2d 733 (8th Cir., 1959);

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Bd. of Educ., 364 F. 2d

189 (4 Cir., 1966); and (2) flagrantly deprived Mr. White

of fundamental due process rights no less important than

notice to a juvenile of the charges against him, or of his

right to counsel and to a hearing before he could be com

mitted to a juvenile institution, In Re Gault, supra; or

the right to a public trial, In Re Oliver, supra; or the

right not to be denied a liquor license without being

2 Other factors include:

a. The racial pattern of previous school assignments, and the

necessity for litigation to bring about a change in said pattern;

b. The subterfuge of appellees in representing to the U. S.

Department of HEW that Nashville was in compliance with that

office’s guidelines on school desegregation;

c. The fact that but little faculty desegregation was con

templated or achieved during the first year after a commitment was

made by appellees to cease faculty discrimination;

d. The fact that teacher reduction was undertaken because

of Negro pupil transfers;

e. The fact that appellees never formally advised the Negro

teachers of appellees desegregation plan;

f. The fact that no formal notice was given the Negro teachers

in 1966 including Mr. White of the contemplated faculty reduction;

g. The fact that the reduction did not occur; and

h. The fact that no objective comparison of all teachers in

the system per appellees commitment was made.

20

afforded due process, Hornsby v. Allen, 326 F. 2d 605, 608

(5 Cir. 1964); or the right to continue receiving welfare

benefits unless same are withdrawn or denied in accord

ance with due process requirements, Rios v. Hackney, Cir.

No. CA 3-1852, (N D. Tex., Dallas Div., Nov. 30, 1967).

It is now well settled that Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed. 2d 1083, (1955)

extends to faculty as well as pupil desegregation.

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198, 200, 86 S. Ct. 358, 15 L. Ed.

2d 265 (1965) ; Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, 382

U. S. 103, 86 S. Ct. 224, 15 L. Ed. 2d 187 (1965). Thus,

racial discrimination in the employment, assignment,

utiliaztion, retention or dismissal of teachers is clearly

proscribed, Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, Ark.,

supra, as was recognized by the appellees in their stipu

lation for dismissal and approval of the District Court’s

decree (R.5).

Apparently, the District Court did not view the ap

pellees conduct as being racially motivated for the Court

made no finding of facts on the racial issue. Instead, the

Court disposed of Mr. White’s complaint by holding that

Mr. White did not comply and the appellees did comply with

appellees “ well adopted and well-known procedures” (R.

161). The Court did not state what those proeeedures

were but if the Court was referring to the desegregation

plan it approved, certainly the details of the plan were

not well-known and well publicized, for the appellees never

explained it to or discussed it with the Negro teachers.

Moreover, 1966 was the first year that appellees had

undertaken to integrate Negro pupils and teachers into

their system. The process was therefore new to all

concerned. It is for this reason that appellees owed

- an especial duty to widely publicize its plan in a suf

ficient manner to drive home to the affected teachers,

especially Mr. White — no less than it did to pupils —

their rights thereunder and how the district proposed to

pi’otect those rights. Clark v. Board of Educ. of Little

Rock, 369 F. 2d 661, 668 (8 Cir. 1965); 8 tell v. Savannah-

Chatham County Bd. of Educ. 333 F. 2d 55, 65 (5 Cir.

1964); Augustus v. Bd. of Public Instruction of Escambia

County, 306 F. 2d 862 (5 Cir. 1962).

Further, the Court supported its decision against

Mr. White in part by stating:

“ For some reason that has not been explained,

Mr. White did (not) see fit to submit the infor

mation, even though there seems to have been some

question raised even during the summer of 1966.

Regardless of that, it appears that he has not

sought to even provide the information to this

date.”

But testimony is to the contrary for Mr. White testi

fied that he obtained the transcripts during the summer,

appeared before appellees and advised appellees that he

had his transcripts, (R.75), and Mr. Moody corroborated

Mr. Whites’ testimony (R.103, 104).

The Court reasoned further: “ Furthermore, he (Mr.

White) proceeded to go to another place, obtain a job, and

a whole school year has passed . . . ” The Court clearly

overlooks the duty placed upon a displaced teacher to

mitigate his damages. Smith v. Board of Educ. of Mor-

rilton, supra.

In conclusion, appellant White’s termination by ap

pellees is (a) clearly based on race and (b) devoid of

the basic rudiments of fairness. The cited cases dictate

reversal.

21

22

XI

Appellees termination of Appellants Walton and King

without making the required objective evaluation of

their qualifications in comparison with all other

teachers in the system violated Appellees plan of

desegregation and otherwise deprived Appellants of

equal protection of the laws.

Appellees violated their policy, agreed to by consent

stipulation, re dismissal of teachers when they termniated

appellants. That policy read:

“ (b) Dismissals. Teachers and other pro

fessional staff will not be dismissed, demoted, or

passed over for retention, promotion, or rehiring

on the ground of race or color. I f consolidation

. . . and the unification of the schools result in a

surplus of teachers, or if for any reason related to

desegregation, it becomes necessary to dismiss or

pass over teachers for retention, a teacher will

be dismissed only upon a determination that his

qualifications are inferior as compared with all

other teachers in the consolidated system.” [Em

phasis added.]

The facts convincingly establish that the all-white

Nashville school district absorbed th e all-N egro

Childress school district and, that, in the process, at the

close of the 1966-67 school term, a large number of

Negro high school pupils chose to attend the white Nash

ville high school. Appellees then decided to close the

top four grades at Southside, assign all of the Negro

pupils in those grades to Nashville, and terminate or

demote the Negro high school teachers and principal. Mr.

Moody, Nashville Superintendent stated that after the

decision was made to close the top four grades at the

Negro school, “ I talked to them (the Negro teachers) in

dividually, privately, that we were going to have to abolish

some of the positions down there, and there wouldn’t be

as large a faculty as we had . . . ” (R.127). The ap-

pelle secretary corroborated this by stating that appellees

'-would have retained them (the Negro teachers) in the

system” had it not been for the pro-integration choices

of the Negro pupils (R.39). (See Rogers v. Paul, 382

U.S. 192, 86 S. Ct. 358, 15 L. Ed. 2d 265 (1965); Smith v.

Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770 (8 Cir. 1965)

cited for proposition that faculty dismissals brought about

by the exercise o f pro-integration choices of pupils, when,

in whole or in part, based on race may impede further

progress in pupil desegregation).

In face of appellees’ previous patterns, practices and

policies of racial discrimination (see footnote 2, supra),

and their failure to voluntarily initiate desegregation,

appellees’ conduct in terminating appellants must clearly

be characterized as racially motivated.

This Court has indicated that the facts of each case

of this type must be carefully examined Brooks v. School

District of City of Moberly, 267 F. 2d 733 (8 Cir. 1959).

A careful examination of the facts here compels the con

clusion that race was the sole reason for appellants’

termination and the manner in which they were otherwise

treated. Although not presented for decision in this

appeal, the cases of Tommie Walton, Altha Shaw and

Prentiss Counts present convincing evidence that the

pattern and practice of treatment of Southside teachers

by appellee was racial. First, Tommie Walton had

previous experience as both a school superintendent and

principal in this community. He also had a good

academic background (R.97). Moreover, the appellees

23 .

24

knew that one or both positions would soon be vacant by the

retirement of Mr. Moody and the probable promotion of

the Nashville principal to the superintendent’s position.

Appellees also knew that in September, 1968, a junior high

principalship would be vacant. Despite these factors,

Mr. Walton was not considered “ for any position” (R.

39). There is no explanation in the record for appellees

failure to consider Mr. Walton for any position other that

it would not be necessary to have a full time principal at

Southside (R.121). Appellant submits that no conclu

sion is possible other than that Mr. Walton was previously

employed by appellants solely for the Negro school rather

than for the entire school system. Johnson v. Branch,

364 F. 2d 177 (4 Cir. 1966) ; Franklin v. County School

Board of Giles County, 360 F. 2d 325, (4 Cir. 1966). The

Court did not make any finding of fact re appellees’

termination of Mr. Walton.

Second, plaintiff Altha Shaw, a negro social science

teacher who filled the vacancy created by the termination

of appellant Major Reynolds White at the close of the

1965-66 school term had his qualifications compared in

the words of Arkansas Circuit Judge Bobby Steel, a

board member of appellee school district:

“ As I recall, the information provided to the

school hoard by Mr. Moody . . . was that Mr. Shaw

had some seven months experience as a teacher in

comparison with a teacher who had been with our

school system several years, and there was no doubt

in our superintendent’s mind to which one was a

better qualified teacher” (R.144).

There is no explanation on the record as to why the

comparison was limited to just one teacher who had been

in the white system a number of years. Absent any ex

planation for failure to follow their plan, and under the

facts herein, a strong inference is raised that race is

the sole reason for Mr. Shaw’s termination. Chambers

v. Hendersonville City Board of Educ. 364 F. 2d 189, 192

(4 Cir. 1966).

Third, Prentiss Counts had been coach and physical

education teacher at Southside High School in previous

years. He was not dismissed at the close of the 1966-67

school term but neither was he considered for a compar

able position in the white high school. Instead, he was

demoted to the Negro elementary school. During the

summer of 1966, the Nashville coaching position became

vacant, a foreseeable event by appellees, but Mr. Counts

was not considered for it; instead, the white assistant

coach was promoted to coach. Neither was Mr. Counts

considered for the assistant coach vacancy; instead, a

white person from another school district was named to

fill it. The reason given by Mr. Moody was that Mr.

Counts could not “ fill that position anyway . . . that is a

football position and he is a basketball coach, has no ex

perience in football” (R.130). Clearly, Mr. Counts was

employed by appellees, as were appellants, as a Negro

teacher for Negro pupils rather than as teacher for the

system.

The district court did not indicate that it placed any

weight upon the evidence re Mr. Counts.

Moreover, appellees do not plan to advise Mr. Walton

and Mr. Shaw that they will be given any consideration

in the event that future vacancies for which they are qual

ified occur within the system, Smith v. MorriUon, supra.

Nothing demonstrates appellees’ callousness and unfair

ness in their treatment of Negro teachers unless, of course,

it is their treatment of Mr. White, Mr. King and Mrs.

Walton.

25 .

26

The district court found that appellees had made the

required comprehensive comparison of Mrs. Walton’s

qualifications with all other teachers in the system in ac

cordance with “ well established procedures.” (See dis

cussion in argument I, supra). But the testimony con

tradicts the Court’s ruling and finding. When Mr.

Moody was asked: “ Did you say . . . you did not com

pare Mrs. Walton’s qualifications with those other teach

ers?” He answered: “ Not all other teachers,” (R.

130; see also R.154). This was corroborated by Judge

Steel who stated:

“ It was my understanding as a school board

member that when Mrs. Walton’s notification was

written that we were comparing her qualifications

with those of Mrs. Marie Stavely, who has been

a member of our faculty for some several years

to my knowledge and who is highly regarded by

all who know her, not only as a splendid teacher,

but as a lovely lady and a Christian lady, and we

felt that she had better qualifications than did

Mrs. Wlaton. It was our determination that if

it was a matter of one of the two teachers, we pre

ferred Mrs. Stavely” (R.144).

There is no testimony to the contrary on this point.

Moreover, it is corroborated by the treatment appellees

accorded Mr. Walton, Mr. Shaw, (see discussion, supra)

and Mr. King.3 Thus, the Court’s finding and ruling

that appellees made an objective, system wide compar

ison between Mrs. Walton and all other teachers in the

system “ is clearly erroneous.” 28 U.S.C. Rule 52(a),

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure. Although the treat

3 Following the answer to the question re comparison of Mrs.

Walton’s qualifications with all other teachers in the system, the

following colloquy occurred between Mr. Moody and counsel:

“Q. And that is true with regard to Mr. King, isn’t it?

A. That’s right” (R.130).

27

ment accorded Mr. King was similar to that accorded

Mrs. Walton, the trial court made no finding re the

legality of Mr. K ing’s dismissal, damages sustained, costs

or attorney’s fees.

Finally, appellees treatment of Mr. King and Mrs.

Walton subsequent to their termination reflects unequal

treatment between teachers who occupied equal status

during the 1966-67 school term. Assuming arguendo that

Mrs. Walton and Mr. King were less qualified for their

positions than their white counterparts, this is not con

clusive proof that they were less qualified than all other

teachers in the system. Even assuming that they were

also the least qualified teachers in the system, there were

vacancies which occurred in the system which they may

have been able to fill had they been given the opportunity

to do so. Especially is this true when many teachers

in Nashville were teaching outside their field of prepara

tion. For example, the position of agriculture teacher

in the white school was left vacant by that person’s pro

motion to the principalship of Nashville high school.

Appellees did not consider assigning Mr. King to fill it.

Instead, they employed a white person from outside the

system in preference to Mr. King who met necessary

qualifications. Furthermore, Mr. King was not consid

ered for any of the other vacancies which occurred prior

to trial. Had it not been for the large number of Negro

pupils preregistering to take vocational agriculture, Mr.

King would not have been afforded the job offered him

as agriculture teacher on the date of trial. Mrs. Walton

was not so fortunate because apparently home economics

was not as popular with the Negro girls as vocational

agriculture was with the Negro boys. Moreover, ap

pellees gave her no consideration for the vacancy in the

white elementary school.

28

This case is factually somewhere between the two

post -Brown cases in this circuit involving dismissal of

Negro teachers as a result of unification of a dual school

system. Brooks v. School District of City of Moberly,

267 F. 2d 733 (8 Cir. 1959); Smith v. Board of Educ. of

Morrilton, supra. Both cases deny that race is a legiti

mate consideration for the employment, utilization or

termination of teachers. In Brooks where dismissals

were sustained, the appellees had: (a) promptly moved

to desegrated by 1955; (b) found it necessary to terminate

a number of teachers; (c) advised each teacher of its

plans; and (d) made a careful study of the qualifications

of all teachers in the system. Although the eleven

teachers found to be least qualified were Negro, a result

characterized by the Court as “ unusual and somewhat

startling,” 267 F. 2d at 739, the Court found no “ positive

evidence that the Board was influenced by racial consid

erations in the matter of employing its teachers.” The

Court went on to state:

“ There are a number of factors tending to

negative any racial prejudice on the part of the

Board. The integration was completed in a man

ner satisfactory to all concerned. The wishes of

the Negroes as to the integration were fully con

sidered and observed. Before integration the

Negro teachers were paid salaries equal to those

of the white teachers, and the Negro school was

furnished with the same type of equipment and

supplies as the white schools.” id at P. 740.

The standard invoked by the Brooks Court for de

termination of the legality of teacher dismissals in the

present context was whether the Board was motivated by

“ unreasonable, arbitrary or . . . racial consideration.”

id at 740. Smith stands for the proposition that after

desegregation has begun, all teachers have equal footing.

29

Thus, it is required that where a Negro school is closed

due to pupil integration pursuant to a freedom of choice

plan, the displaced personnel must be absorbed at a min

imum into the other schools in the system, Yarbrough v.

Ilulbert-West Memphis Sch. Dist. No. 4, 380 F. 2d 962,

967 (8 Cir. 1967), unless the Brooks type of objective

comparative evaluation of all teachers in the system is

made. In Brooks, the superintendent provided Ms Board

with detailed information about not only the Negro teach

ers but about all teachers. The Board then considered

that information independently along with the recom

mendation of the Superintendent, Here, the Board was

never confronted with detailed information about any of

the teachers, made no independent consideration and re

lied instead solely on the recommendation of the Super

intendent who himself did not compare the qualifications

of all the districts’ teachers. Only with such detailed

information can the required objective comparison be

made, especially in this school system where the white

superintendent has only had brief, limited contact with

the Negro schools. Chambers v. Hendersonville City

Board of Edu,, supra; Franklin v. County School Board

of Giles County, supra; Smith v. Board of Educ. of Mor-

rilton, supra.

Furthermore, appellees procedures in filling vacancies

fall short of constitutional standards. First, Mr. Moody

failed to advise the displaced teachers that to be consid

ered for any future vacancy they must reapply. Second,

appellees were willing to hire Mr. King after this litiga

tion was initiated without his completing a new appli

cation. Third, Mrs. Walton was considered for a posi

tion in the Negro elementary school before her termina

tion but there were no vacancies. These factors strongly

suggest race as the lone motive for appellees conduct and

thus disclose “ an unconstitutional selection process.”

30

Smith v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, supra at Pp. 782,

783; Franklin v. County School Board of Giles Comity,

supra; Wall v. Stanly County Board of Educ., F.

2d ___ , (4 Cir. 1967); Chambers v. Hendersonville City

Board of Educ., 364 F. 2d 189 (4 Cir. 1966). See also,

Note, Discrimination in the Hiring and Assignment of

Teachers in the Public School Systems, 64 Mich. L. R.

692 (1966). Reversal is thus clearly warranted because

of appellees “ invidious,” racially discriminatory and ar

bitrary treatment of appellants.

iii

Because of Appellees unconstitutional treatment of A p

pellants and because of Appellees refusal to comply

with their desegregation plan, Appellants are en

titled to the relief of reinstatement, damages, at

torneys’ fees, costs; or appropriate alternative relief.

The record discloses strong evidence of appellees’

invidious and unfair racial prejudice in their termination

and other actions of and toward appellants. In

deed, in a previous case, appellees agreed to a

faculty desegregation dismissal provision as a con

dition for the entering of a dismissal order by

the district court which, as shown, supra, was flagrant

ly and callously violated. Appellants were thus forced

into this litigation to protect their rights. Thus, appel

lants are entitled to the equitable relief of damages, at

torneys’ fees, and costs. Bell v. School Board of Pow

hatan County, Va., 321 F. 2d 494, 500 (4 Cir. 1963); Smith

v. Board of Educ. of Morrilton, 365 F. 2d 770, 784 (8

Cir. 1966); Chambers v, Hendersonville City Board of

Educ., 364 F. 2d 189, 193 (4 Cir. 1966); Johnson v. Branch,

364 F. 2d 177, 182 (4 Cir. 1966).

31

Moreover, equity requires that Mr. White and Mrs.

Walton also be reinstated; or that relief more appropriate

be fashioned as was done by this Court in Smith. See

also, Kelley v. Altheimer, 378 F. 2d 483 (8 Cir, 1967).

Further, under the circumstances, if this court grants

the requested relief, petitioners are further entitled to a

protective order from this court which enjoins appellees

from punishing or attempting to penalize them because

appellants prosecuted this action.

32

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, appellants respectfully

pray for an order of reversal.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn W . W alker

N orman J . C h a c h k in

1304-B Wright Ave.

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

J ack G reenberg

J am es M . N abrit , III

M ichael M . M eltsner

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

Attorneys for Appellant

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I haim served two copies of this

brief upon Mr. Boyd Tackett, Texarkana, Arkansas, by

depositing same addressed to him in the U. S. Mail, post

age prepaid, this 23rd day of January, 1968.

John W. Walker

Attorney for Appellants

,*•

■