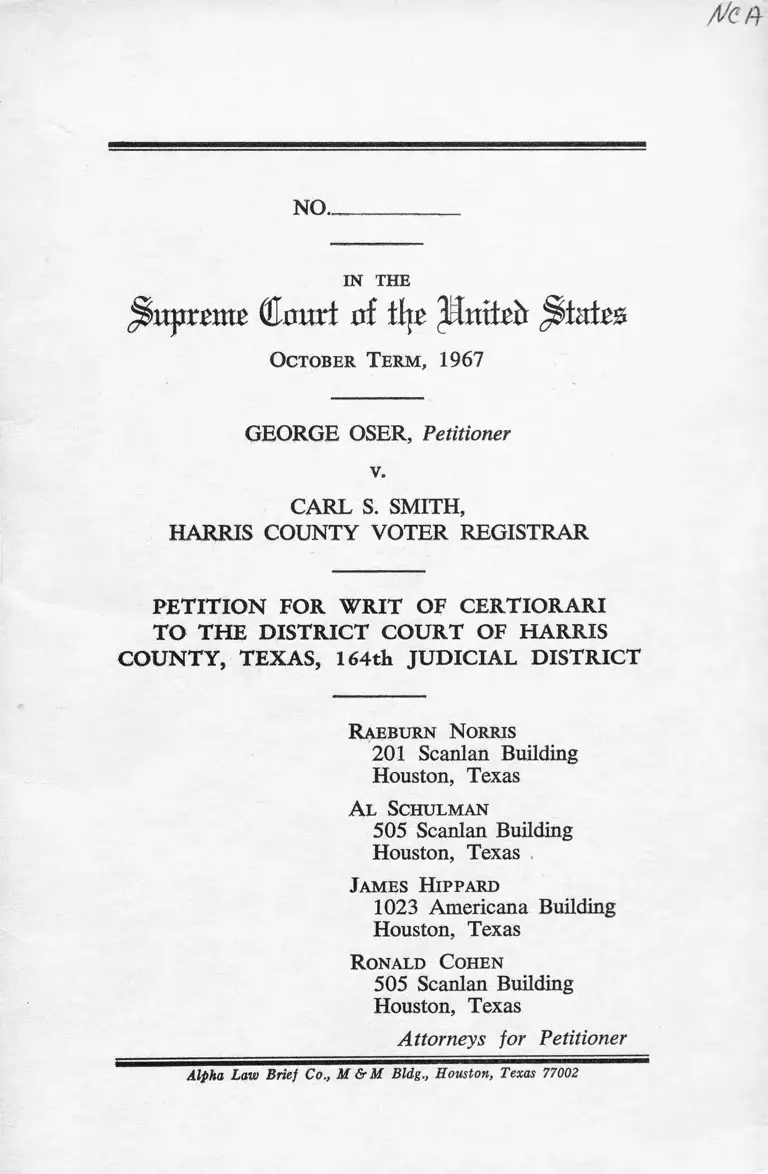

Oser v. Smith Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Distr. Court of Harris County, TX

Public Court Documents

February 28, 1968

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Oser v. Smith Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Distr. Court of Harris County, TX, 1968. fbd1f175-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/23fba4f1-8122-421c-80b5-1789416dddfa/oser-v-smith-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-distr-court-of-harris-county-tx. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

/t/e#

NO.

IN THE

hxptrnt (Efluri erf % 3iXrttfeb JState

O c to b er T e r m , 1967

GEORGE OSER, Petitioner

v.

CARL S. SMITH,

HARRIS COUNTY VOTER REGISTRAR

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE DISTRICT COURT OF HARRIS

COUNTY, TEXAS, 164th JUDICIAL DISTRICT

R a eb u rn N orris

201 Scanlan Building

Houston, Texas

Al Sc h u l m a n

505 Scanlan Building

Houston, Texas

J a m es H ippa r d

1023 Americana Building

Houston, Texas

R onald C o h en

505 Scanlan Building

Houston, Texas

Attorneys for Petitioner

Alpha Law Brief Co., M & M Bldg., Houston, Texas 77002

INDEX

T a ble o f C o n t e n t s Page

OPINION BELOW 2

JURISDICTION 2

QUESTION PRESENTED 2

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY PRO

VISIONS INVOLVED 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 3

A. Pertinent Pleadings and How the Federal

Questions were Raised ............................. 3

B. The Facts .................................................. 4

C. Why the Case is Not M o o t....................... 8

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT 9

CONCLUSION 14

T able o f C ases

Page

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) .............. 9

Bartkus v. Illinois, 359 U.S. 121, 155 (1959) 13

Hague v. C.I.O., 92 U.S. 531 ........................... 10

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 519 (1939) 10

Harper v. Virgina State Board of Elections, 383

U.S. 663, 670 (1966) ................................... 9

Katz v. United S tates,___ U.S____, 88 S.Ct.

507, 511 (1967) ............................................ 9

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 643, 647

(1966) ............................................................ 10

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167 (1961) 13

Parker v. Busby, 170 S.W. 1042 (Tex. Civ. App.

1949) ............................................................... 11

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 554 (1964) 9, 12, 14

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U.S. 1, 8 (1944) . . . 13, 14

United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 543, 552,

553 (1876) ...................................................... 10

Walker v. Thetford, 418 S.W.2d 276, 287, 288

(June 1967), writ ref. n.r.e.............................. 12

Wesberry v. Sanders, 376 U.S. 1, 17 (1964) 10

II

m isc e l la n eo u s Page

Edmond Cahn, The Predicament of Democratic

Man, 1961, Dell Pub. Co............................. 14

“Education and Politics in Boomtown,” Mosko-

witz, Saturday Review, Feb. 17, 1968, p. 52 8

CONSTITUTION AND STATUTES

U. S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment 2, 3, 9, 13

U. S. Constitution, Due Process Clause ............ 2, 9, 11

28 U.S.C., Sec. 1 2 5 7 (3 ) ................................... 2

42 U.S.C., Sec. 1983 14

Texas Revised Civil Statutes:

Art. 5. iOa ........................................................ 4

Art. 5.11a 6

Art. 5 .1 2 a ........................................................ 6, 11

Art. 5.17 4

Art. 5 .17a ........................................................ 2, 6

I ndex to A ppe n d ix in P e t it io n

Appendix A:

Instrument Cancelling Petitioner’s Voter Regis

tration for 1967, Executed by Carl Smith,

Harris County Voter Registrar, November 22,

1967 ................................................................. la

Judgment of the 164th Judicial District Court,

January 3, 1968 ............................................ 3a

Appendix B:

U. S. Constitution, Amendment XIV 6a

Texas Revised Civil Statutes ................ 6a

Article 5.10a 6a

Article 5 .1 1 a ................................................ 7a

Article 5 .1 2 a ................................................ 7a

Article 5 .1 7 .................................................. 8a

Article 5 .1 7 a ................................................ 9a

NO

IN THE

mprtmt ffluitri of \ \ \ t pmtefr States

O c to b er T e r m , 1967

GEORGE OSER, Petitioner

v.

CARL S. SMITH,

HARRIS COUNTY VOTER REGISTRAR

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE DISTRICT COURT OF HARRIS

COUNTY, TEXAS, 164th JUDICIAL DISTRICT

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice and the Associate

Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States:

Petitioner, George Oser, prays that a writ of certiorari

issue to review the judgment of the District Court of

Harris County, Texas, 164th Judicial District, entered

January 3, 1968 (A. 3a; Tr. 8) in Case No. 750,608,

styled George Oser v. Carl S. Smith, Harris County Voter

Registrar, Defendant, and George Polk and Sam Lucario,

Challengers, wherein the 164th Judicial District Court of

Harris County affirmed by judgment (A. 3a; Tr. 8, 9)

2

the Order of the Harris County Voter Registrar (A. la;

Tr. 42) cancelling the Voter Registration of petitioner,

despite petitioner’s claim that such judgment constitutes

an unlawful deprivation of his right to vote.

OPINION BELOW

No opinion was rendered by the court. An order stating

the court’s Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law was

entered December 20, 1967, and is unpublished. It ap

pears in the olhcial transcript filed with the papers in this

Petition (Tr. 60, 61).

JURISDICTION

Judgment of the 164th District Court of Harris County,

Texas was entered, nunc pro tunc, on January 3, 1968

(A. 3a; Tr. 8, 9). In petitioner’s action, according to

Texas Revised Civil Statutes, Art. 5.17a (A. 9a) “the

decision of the district court shall be final.” Because no

case has interpreted the finality of the above language,

petitioner, out of an abundance of caution, has perfected

an appeal in this case to the Court of Civil Appeals of

Texas. However, the challenger of Petitioner’s registration,

by judicial admission in the Court below, took the position

that no further appeal could be had from the District

Court’s decision. (Tr. p. 50). This Court’s jurisdiction

is invoked under 28 U.S.C., Section 1257(3).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the Due Process Clause, as well as the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects

the right to vote in a state election of a citizen who has

all the necessary qualifications for voting save a voter-

3

registration certificate, where the citizen made repeated

timely applications to the voter registrar but the registrar

failed and refused to issue the citizen a certificate?

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The constitutional provision involved is the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

In addition, five sections of the Texas Election Code are

involved. These provisions, in pertinent part, are set forth

in Appendix B to the instant Petition (A. 6a).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. P e r t in e n t P leadings A nd H o w T h e F ederal

Q u estio n W as R aised .

Petitioner, George Oser, filed an appeal in the District

Court to re-establish his right to vote, after the Harris

County Voter Registrar entered an order cancelling his

registration. Petitioner pled that he had made repeated

timely applications for registration which were ignored by

the voting officials. The registration finally issued him was

held to be not timely and, therefore, cancelled at a hearing

of the Registrar called to consider the status of petitioner’s

registration. Petitioner asserted that because of the im

portance of the constitutionally-protected right to vote, his

continued good-faith efforts to register should be deemed

to be a compliance with the state registration laws (Tr.

14-17). The court holding against petitioner, petitioner

gave notice in open court before final judgment that he

would press the issue of denial of due process and of

equal protection of the laws (Tr. 56), and he asserted

that an interpretation of the Texas voter registration law

4

to deny petitioner’s right to vote necessarily brought such

voter registration law into conflict with the requirements

of due process (Tr. 56). After such notice the court

concluded that the statutes were applicable to the case,

found that petitioner had not been issued a timely certifi

cate, and upheld the cancellation of the certificate (Tr.

61).

B. T h e F acts

The facts, which are not in dispute, are established by

admissions in the pleadings contained in the Transcript

(Tr.), by uncontroverted testimony admitted in evidence

by the court and contained in the Statement of Facts

(S.F.) and by Exhibits (E.).

Petitioner, George Oser, is a citizen of the United

States and of Harris County, Texas. On October 15, 1966,

petitioner, acting through his wife as agent, as permitted

by Texas law, called the Office of the Tax Assessor, Carl

S. Smith, the chief voter registrar for Harris County, and

requested applications for voter registration certificates

for the both of them. Petitioner’s wife telephoned on the

assumption that having established six-month residence

in the county, they would be entitled to register during

the registration period that had begun October 1 (S.F.

51). In fact, Articles 5.10a and 5.17, the provisions of

the election code providing for the issuance of registrations

and exemption from the poll tax for new residents, did

direct that applications for registration be issued them at

the time of the call (A. 6a, 8a). Article 5.17, providing

poll tax exemptions, was applicable until its repeal, ef

fective February 1, 1967. The overlapping statute, Article

5.10a, which had been passed effective October 1, 1966

5

to establish new registration procedures in light of the

demise of the poll tax, also directed that petitioner be

registered at the time of their call (A. 6a). Although

petitioner would not have been entitled to vote at the

polls until he had been a county resident for six months

and a state resident for twelve, he was entitled to register

to vote under either of the two pertinent registration

statutes, and because he was a citizen who met every

necessary qualification in the election code, the statutes

charged the tax assessor’s office with the duty to accept

his application. Despite this, petitioner’s wife was told

that they could not be registered and she was told to call

back in January, 1967 (S.F. 21). Petitioner’s wife, as

agent, called back in January, twice. In the first of those

calls, petitioner’s request for a registration form was

denied, and petitioner was told by the deputy registrar

that petitioner and his wife would have to be residents

of the state for twelve months before they could register.

No law, old or new, contained a requirement such as this

one. Petitioner’s wife called again in January to clarify

her understanding and requested she be sent application

forms to register. This time the deputy to whom she was

referred told her that she was “wasting her time,” and

no forms were sent to her (S.F. 67).

In July, 1967, following the publication of sample voter

registration applications in local newspapers because of

“the effect of new laws,” petitioners applied for voter

registration certificates, armed with the knowledge that

their one year of state residence had been established.

This time their applications were accepted and certificates

issued them (S.F. 59-61; E. 2). Petitioner’s certificate

recited that he had become a resident on April 15, 1966

(.before the beginning of the previous registration period,

6

October 1, 1966) and that he was entitled to vote at any

election after April 15, 1967 (E. 2).

On or about October 26, 1967, a short while after

petitioner filed as a candidate for the Houston School

Board, he was contacted by the tax assessor’s office and

told that something was amiss with his registration (S.F.

22). The basis for a challenge to the certificate in his

possession was Article 5.11a, which set an exclusive

period for registration, and Article 5.12a, which held that

new residents of the state who had established their resi

dency after the beginning of the previous registration

period could register for that voting year after the close

of the registration period, which in petitioner’s case was

January 31, 1967. Article 5.12a became law on June 12,

1967, less than one month before petitioner applied for

and received his registration certificate. The morning after

petitioner received this message, he was contacted again

by the registrar’s office, who told him this time that it

was a mistake on their part and that petitioner’s name

would not be taken off the voter rolls (S.F. 64).

Petitioner received over 53,000 votes in the school

board election held on November 18, 1967, thereby

qualifying for the run-off to be held shortly thereafter.

On November 22, 1967, at a hearing called by Carl S.

Smith, County Tax Assessor, petitioner’s registration cer

tificate was held to be untimely issued, and his name was

ordered stricken from the voter rolls (A. la ). Appeal

was perfected by petitioner to the 164th Judicial District

Court pursuant to Article 5.17a (A. 4a, 9a).

At the trial court petitioner asserted the liberal pro

tections in Texas law protecting the right to vote (Tr.

14-16, 43-45). He relied largely upon an Opinion of the

7

State Attorney General, to be accorded the highest weight

in the absence of controlling case law, which held that

a person who has made timely application for a voting

certificate but who has failed to obtain one because of

the failure of the county authorities to provide and issue

one, may not be deprived of his right to vote (Tr. 21-29).

Despite this the Court upheld the action of the county

voter registrar and executed an order which recited:

“Plaintiff did not properly register and did not diligently

comply with the means available to him to register in

accordance with the law prior to the 1967 election held

by the School Board of the Houston Independent School

District” (Tr. 33, 34). Final judgment, nunc pro tunc,

was entered on the above order on January 3, 1968

(A. 3a; Tr. 8, 9).

At the trial court the chief voting registrar testified

repeatedly about mistakes in his office procedures and

confusion about the election laws as the reason for the

refusal of any timely applications by petitioner. His office

operated under the belief, even months after Article 5.17’s

repeal, that petitioner could register at any time up to

thirty days before an election and vote after he had com

pleted one year of residence (S.F. 42, 43). This partly

explains why petitioner was not registered when he applied

during the registration period. The registrar admitted con

fusion regarding the changes in the election laws at the

time when petitioner first applied (S.F. 48). He testified

that his deputies would have been violating the procedure

of their own office in not referring petitioner to someone

higher in authority before making a refusal (S.F. 45).

Moreover, when petitioner was finally issued a certificate

in July, 1967, such issuance, according to the registrar

was “for lack of being up on the law” (S.F. 42). The

registrar testified that he had issued at least forty regis

trations in addition to petitioner’s to persons in a similar

situation (S.F. 37).

It was undisputed that prior to the time of petitioner’s

repeated applications, the state had exercised its power

to make classifications and establish requirements to quali

fy for the franchise, that there was no issue of bona fide

residence involved or determined against petitioner, that

petitioner was not contained in any category of persons

disqualified to vote, and that there was no administrative

benefit to the state in refusing his applications. Each time

petitioner applied, there remained only for the registrar

to issue an application, receive and process it.

C. W hy T h e C ase I s N ot M oot

Restoring petitioner’s 1967 right to vote would not be

an empty gesture. The outcome of an election turned on

his disputed qualifications as a voter, and decision in this

case would alter the merits of an election contest filed in

petitioner’s behalf. After petitioner forced an encumbent

member of the Houston School Board into a run-off, the

County Voting Registrar cancelled petitioner’s registra

tion certificate. While petitioner was appearing before the

Texas Supreme Court in an attempt to establish his quali

fications as a voter by extraordinary proceeding, the

School Board simply removed Oser’s name from the bal

lot and the Court informally ruled that the question was

moot because the election was already in progress. Peti

tioner’s suit now pending calls for a new election for the

four-year position.1

1. The events above were included in a longer report concerning

the Houston School Board, “Education and Politics in Boomtown,”

Moskowitz, Saturday Review, February 17. 1968, p. 52.

9

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

This Court has stated, “Undeniably the Constitution of

the United States protects the right of all qualified citizens

to vote, in state as well as in federal elections.” Reynolds

v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 554 (1964). Though the Court,

in applying the Fourteenth Amendment to protect the

franchise, has relied on “a searching re-examination of

the Equal Protection Clause,” Harper v. Virginia State

Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663, 670 (1966), since the

decision in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), it must

inescapably follow and this case is ripe for decision that

State election practices also cannot conflict with the re

quirements of the Due Process Clause. The traditional

treatment of the franchise is similar to that of a person’s

general right to privacy as this Court described it: “like

the protection of his property and of his very life, left

largely to the law of the individual States.” Katz v, United

States, ___ U.S____, 88 S.Ct. 507, 511 (1967). But

despite distinction between “federal rights” and “federally-

protected rights” this Court has held, “Once the franchise

is granted to the electorate, lines may not be drawn which

are inconsistent with the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment.” Harper v. Virginia State Board

of Elections, above, 383 U.S. at 665. Such continued

avowals as this one by the Court compel the conclusion

that a citizen may not be disenfranchised by the unlawful

application of state registration laws without suffering

deprivation of the fundamental fairness that our people

are taught to expect automatically.

Petitioner asserts that the Due Process Clause preserves

the integrity of the franchise and does so without enlarging

the category of privileges and immunities of United States

10

citizenship that has been established previously. Having

met the qualifications defined by the State, petitioner must

be able to exercise his right to vote free from capricious

abridgment; this is essential to “the very idea of a gov

ernment, republican in form,” the same way in which the

Court described the right of citizens “to meet peaceably

for consultation in respect to public affairs and to petition

for a redress of grievances.” United States v. Cruikshank, 92

U.S. 542, 552, 553 (1876). Yet as to these just-mentioned

freedoms of speech and of assembly, according to Mr.

Justice Stone, “it has never been held that either is a

privilege or immunity peculiar to citizenship of the United

States, to which alone the privileges and immunities clause

refers.” Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496, 519 (1939)

(plurality opinion). The Due Process Clause must protect

them and the clause is to be applied “whenever the right

or immunity is one of personal liberty, not dependent for

its existence upon the infringement of property rights.”

Hague v. C.I.O., above, 92 U.S. at 531 (by Mr. Justice

Stone).

This Court has begun to surround the franchise with

protections afforded only the most fundamental personal

rights. The issue of personal liberty involved in protecting

the franchise is expressed by the Court when it says, “No

right is more precious in a free country than that of

having a voice in the election of those who make the

laws under which, as good citizens, we must live.” Wes-

berry v. Sanders, 316 U.S. 1, 17 (1964). Therefore, the

states by law or practice “have no power to grant or

withhold the franchise on conditions that are forbidden

by the Fourteenth Amendment or any other provision of

the Constitution.” Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 643

647 (1966).

11

Petitioner’s attempts to register were thwarted, as the

record shows, because of a profusion of procedural in

adequacies violative of the requirements of due process.

It was only natural for a citizen inquiring on three sep

arate occasions whether he would be permitted to register

to rely on the advice of the officials to whom his inquiries

were directed. The Court’s Findings of Fact (Tr. 61),

that petitioner “did not apply for registration as a voter

during [the prescribed] period,” is in glaring discrepancy

with the uncontradicted testimony that petitioner not only

made continued attempts to register at the times when

he should have been registered, but demonstrated his per

sistence by applying again and being issued a registration,

this time, however, after the effective date of Article 5.12a,

which retrospectively closed the registrar’s doors to all

those who had become residents before the beginning of

the previous registration period, according to the inter

pretation placed thereon by the District Court. Moreover,

the findings in the court’s opinion and judgment (A. 3a;

Tr. 8, 9, 61) that petitioner did not exercise reason

able diligence or take reasonable advantage of the means

available to enforce his right cannot stand before the

evidence that petitioner, as a qualified voter, had done

all that the law required at his own hands. The statutes

which established the exclusive period for registration did

not anticipate a case of an election official’s refusal to

act.2 It would have been unnatural for petitioner to have

pursued the matter with the election officials who told

him he was “wasting his time.” (S.F. 67) Legal action,

2. Under Texas law the failure of an election official to issue a

registration blank though resulting from an innocent misapprehension

of the legal requirements is tantamount to an outright refusal to issue

the blank. Parker v. Busby, 170 S.W. 1042 (Tex. Civ. App. 1949).

12

by mandamus or other extraordinary remedy, would not

only have been unnatural, but would have been to add

onerous conditions not required by the election laws.

In addition, that one of petitioner’s most fundamental

rights was so casually abridged, because of the misappli

cation of the election laws on the part of the state voting

officials specifically charged with administering them, de

prived petitioner of “the opportunity for equal participa

tion by all voters in the election of [state officials] that

is required [by the Equal Protection Clause].” Reynolds

v. Sims, above, 377 U.S. at 566.

The registrar corrected his mistake by cancelling the

registration of this petitioner, alone among the forty-five

registrations which had been similarly issued. The Court’s

affirmance of this action was, at the least, an unusual

application of Texas law. A Court of Civil Appeals had

recently concluded that the Texas case law unequivocably

demanded an interpretation of registration laws and all

other statutes regulating the right to vote which would

avoid, within reasonable interpretation, depriving indi

viduals of their franchises. The court found Texas within

the general rule that “a vote is not rendered invalid by

an irregularity in registration due to the act or default

of registration officers.” (Quoting American Jurispru

dence) Walker v. Thetford, 418 S.W.2d 276, 287, 288

(June, 1967) (writ refused, no reversible error found by

the State Supreme Court). The statement most directly

in point, the Attorney General’s Opinion (Tr. 21-29),

held that the vote should not be deprived when attempts

to register had foundered on the voting officials’ ignorance

of the laws. Such was the unequal treatment afforded

petitioner.

13

In Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U.S, 1, 8 (1944), the

Court indicated a need to allege deliberate discrimination

to invoke the Equal Protection Clause, where the right

to hold state office and the right to vote in state elections

was held not to be a privilege of a citizen of the United

States, as the Constitution defines such privileges. The

Court put it as follows:

“The unlawful administration by state officers of a

state statute fair on its face, resulting in its unequal

application to those who are entitled to be treated

alike, is not a denial of equal protection unless there

is shown to be present in it an element of intentional

or purposeful discrimination.” Snowden v. Hughes,

above, 321 U.S. at p. 8.

The reapportionment decisions of this Court dealt with

dilutions of the state franchise by striking down uncon

stitutional statutes. To the extent therein that the Court

held that the Equal Protection Clause assures an equal

voice to all who hold the right to vote, the basis was laid

for protecting the right from arbitrary abridgement in

fact, without having to trace such abridgement to inten

tional discrimination. Regardless of the intent of the offi

cials in refusing to register petitioner, when taking Mr.

Justice Black’s direction to examine the application of the

laws “from the standpoint of the individual who is being

prosecuted,” Bartkus v. Illinois, 359 U.S. 121, 155 (1959)

(dissent), the franchise was withheld from petitioner when

he was qualified to become a registered voter, and the

disenfranchisement was not occasioned by his own fault

or neglect. The decision in Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167

(1961), effectively overruled the provisions of Snowden v.

Hughes, above, concerning the Equal Protection Clause

14

insofar as it was no longer necessary to allege specific

intent in a Section 1983 action. Title 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983.

If the remaining language of Snowden would direct that

the legal voter who has properly applied for registration

in a state election, but who has been deprived of the right

by the failure of the registrar to act can, by reason of

such failure, also be deprived by the state of the Con

stitutionally-protected right to vote at the polls, then such

language was overruled, sub silentio, by Reynolds v. Sims,

above.

Due process of the laws requires not a search for the

intention behind official conduct, but an analysis of its

necessary consequence. A renowned observer of our demo

cratic institutions has stated: “Due process is at once our

acknowledgment of ignorance and our device to mitigate

the damage that ignorance inflicts.” Edmond Cahn, The

Predicament of Democratic Man, 1961, Dell Publishing

Co., N.Y., p. 149. The conduct of the registrar would

raise the doctrine of estoppel in pais in common law. Due

process requires that the doctrine be converted here into

a barrier surrounding petitioner’s Constitutionally-protect

ed right, keeping it from capricious encroachment.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons assigned, petitioner prays that the Pe

tition for Writ of Certiorari should be granted and that

the writ issue to review the decision and judgment of the

15

164th Judicial District Court of Harris County, Texas,

entered in Cause No. 750,608 on January 3, 1968.

Respectfully submitted,

R a eb u r n N orris

201 Scanlan Building

Houston, Texas

A l Sc h u lm a n

505 Scanlan Building

Houston, Texas

J a m es H ippa r d

1023 Americana Building

Houston, Texas

R onald C o hen

505 Scanlan Building

Houston, Texas

Attorneys for Petitioner

D a t e d : February 28, 1968

la

APPENDIX A

INSTRUMENT CANCELLING DR. GEORGE OSER’S

VOTER REGISTRATION FOR 1967, EXECUTED BY

CARL SMITH, HARRIS COUNTY VOTER REGIS

TRAR, DATED NOVEMBER 22, 1967. FILED

AMONG THE PAPERS.

Since the Court of Civil Appeals has refused the writ

of mandamus and apparently does not have jurisdiction;

And further since the Election Code puts the responsi

bility squarely upon the shoulders of the Voter Registrar

to make a decision;

And since time is of the essence that I make a decision

so that any or all parties to the controversy may appeal

to the District Court, as provided for in Article 5.17a,

Section 2, of the Election Code;

And since there is adequate relief through such an

appeal, I have decided to make a determination as to the

legality of the registration of Dr. George T. Oser.

After listening to all of the evidence presented by all

parties concerned;

And the further fact that Dr. Oser was advised several

days prior to the printing of the ballots in the first election

of the fact that his voter registration was in question and

would probably be challenged;

I find that I have no alternative except to rule as

follows:

The registration of Dr. George T. Oser is hereby

canceled.

2a

Since Article 5.17a, Section 2, provides that either

party to the controversy may appeal from my decision

within 30 days, I would assume that Dr. Oser through

his Attorney will do so.

Article 5.17a, Section 2, provides that the District

Court is to hear any appeals from my decision. I am

making my decision today in order that sufficient time

will be provided the parties for an appeal prior to the

printing of the ballots.

I am informed that ballots will not be printed until

Monday, and I am also informed that the District Courts

will be available all day Friday.

Chief Election Officer John Hill has ruled that any

registrations after midnight, January 31, 1967, of persons

who were residents of the State of Texas on the first day

of the registration period are erroneous and that the Voter

Registrar had no authority to register such persons.

Therefore Dr. George Oser’s Registration for 1967 is

Cancelled,

CARL S. SMITH,

Harris County Voter Registrar

November 22, 1967

3a

JUDGMENT NUNC PRO TUNC OF THE 164th

JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT, DATED JANUARY 3,

1968. ENTERED: Volume 519, Page 553, General

Minutes District & Domestic Relations Courts, in and for

Harris County, Texas. ALSO NOTICE OF APPEAL

GIVEN.

NO. 750,608

IN THE

DISTRICT COURT OF HARRIS COUNTY, TEXAS

164th JUDICIAL DISTRICT

GEORGE OSER, Plaintiff

v.

CARL S. SMITH,

HARRIS COUNTY VOTER REGISTRAR, Defendant

GEORGE POLK and SAM LUCARIO, Challengers

On this the 24th day of November, 1967, came on to

be heard the above entitled and numbered cause, and

came Plaintiff, George Oser, in person and by his counsel

of record, Raeburn Norris, A1 Schulman and James L.

Hippard, and announced ready with reference to plaintiff’s

appeal from the decision of the Harris County Voter

Registrar, Carl Smith, cancelling Plaintiff’s 1967 Voter

Registration Certificate, the said Registrar also appearing

in person and announced ready, and came said Chal

lenger, George Polk, in person and by his counsel of

record, Fred W. Moore, and stated in open court that

he was not ready and that he had not had an opportunity

4a

to prepare the pleadings he desired and asked for a con

tinuance, whereupon the Court directed said Challenger

Polk to apply to the presiding district judge, the Honorable

Lewis Dickson, for such continuance which was done,

but Challengers’ request for continuance was denied, to

which denial the Challenger excepted in open court,

whereupon the Judge of this Court announced that he

would proceed to trial inasmuch as an election was im

minent, being called for December 5, 1967, and this

Court directed all parties proceed to trial which was done

and all said parties participated therein, except Sam

Lucario who appeared only as a witness; and

After duly considering the pleadings, that is Plaintiffs

appeal, the challenge filed by the said George Polk before

the said Carl Smith, his decision and the evidence offered

by all parties and the argument of counsel, this Court

finds that George Oser, Plaintiff, did not properly register

and did not diligently comply with the means available

to him to register in accordance with the law prior to

the 1967 election held by the School Board of the Houston

Independent School District and that the decision of said

Registrar, Carl Smith, was correct and that said appeal

should be denied.

It is THEREFORE, ORDERED, ADJUDGED AND

DECREED that the appeal of George Oser, Plaintiff, is

hereby denied and the decision of Carl Smith, Harris

County Voter Registrar, Defendant, is hereby affirmed

and Plaintiff’s 1967 Voter Registration Certificate is here

by cancelled to which ruling of this Court plaintiff ex

cepted and gave notice of appeal.

5a

Signed and entered nunc pro tunc this 3rd day of

January, 1968.

JOHN R. COMPTON

Judge

APPROVED:

Attorney for Challenger

George Polk

APPROVED AS TO FORM ONLY:

Raeburn Norris

A1 Schulman

James L. Hippard

By AL SCHULMAN

Attorneys for Plaintiff

6a

APPENDIX B

U. S. Constitution, Amendment XIV, Section I:

“Ail persons born or naturalized in the United States,

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens

of the United States and of the State wherein they

reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which

shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens

of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any

person of life, liberty, or property, without due

process of law; nor deny to any person within its

jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Texas Revised Civil Statutes, art. 5.10a (effective Oct. 1,

1966)

Persons entitled to register

Every person who at the time of applying for

registration is in other respects a qualified elector,

or who will become a qualified elector within one

year from the first day of March following the date

of his application for registration, shall be entitled to

register as a voter of the precinct in which he resides;

provided, however, that no person shall be entitled

to vote at any election unless he is a qualified elector

on the date of the election. The registration certificate

of a person who registers before he becomes a quali

fied elector shall have stamped or written thereon the

following: “Not entitled to vote before_______

(date on which he will become a qualified elector

to be inserted in the blank), and this notation shall

also be placed opposite his name on the list of reg

istered voters.

Texas Revised Civil Statutes, art. 5.11a (effective Oct. 1,

1966)

Annual registration; period for registration; period

for which registration is effective

Voters shall register annually. The first period for

registration under this law shall begin in each county

immediately upon the effective date of this Section

and shall end on the thirty-first day of January fol

lowing; provided, however, that if this Section takes

effect after January 1, 1967, as the result of a court

decision, the registration period shall continue

through the thirtieth day following the effective date.

In each year thereafter, the period for registration

shall be from the first day of October through the

thirty-first day of January following. The first regis

tration hereunder shall entitle the registrant, if other

wise qualified, to vote at elections held between the

first day of February following the registration period

and the last day of February of the following year.

Each annual registration thereafter shall entitle the

registrant, if otherwise qualified, to vote at elections

held during the period of one year beginning on the

first day of March following the registration period.

Texas Revised Civil Statutes, art. 5.12a (effective June

12, 1967)

Registration by . . . new residents

Subdivision 2. New Residents. Any person who

was not a resident of the state on the first day of

the regular registration period but who becomes a

resident before the beginning date of a voting year

may register for that voting year at any time after

he becomes a resident and up to thirty days before

the end of the voting year, if at the time of applying

for registration he is a qualified elector or will be

come a qualified elector before the end of the voting

year.

8 a

Texas Revised Civil Statutes, art. 5.17 (repealed effective

Feb. 1, 1967)

Certificates of exemption based on nonage and non

residence

As a condition to voting, any person who is in

other respects a qualified voter and who is exempt

from the payment of a poll tax by reason of the fact

that he had not yet reached the age of twenty-one

(21) years or was not a resident of this State on

the first day of January preceding its levy, must have

obtained from the tax collector of the county of his

residence a certificate of exemption from the pay

ment of a poll tax not later than thirty (30) days

before any election at which he wishes to vote; pro

vided, however, that a person who obtains an exemp

tion certificate at any time before the first day of

February for use during the ensuing voting year may

vote at any election held after the beginning of the

voting year if he is otherwise eligible to vote at the

time of the election. No such person who has failed

or refused to obtain such certificate of exemption

shall be allowed to vote.

An exempt person who applies for a certificate as

prescribed by this Section between the dates of Octo

ber 1st and January 1st following shall be issued a

certificate for use during the remainder of the current

voting year (the voting year being from February 1st

through January 31st) if he is then a qualified elector

or will become a qualified elector before the expira

tion of that voting year, and shall also be issued a

certificate for use during the ensuing voting year if

he will be entitled to vote without payment of a poll

tax during the ensuing year. On applications received

between the dates of January 2nd and January 31st

following, the tax collector shall issue the applicant

9a

an exemption certificate for use during the ensuing

voting year if he will be a qualified elector entitled

to vote without payment of a poll tax at any time

during the ensuing year. On applications received

between the dates of February 1st and September

30th following, the tax collector shall issue the appli

cant an exemption certificate for use during the

current voting year if he is then a qualified elector

or will become a qualified elector before the end

of that voting year.

Texas Revised Civil Statutes, art. 5.17a (effective Oct. 1,

1966)

Subdivision 2. Challenge of registered voter. Any

registered voter shall have the right to challenge the

registration of any other registered voter in his county

by filing with the registrar of voters a sworn state

ment setting out the grounds for such challenge.

The registrar shall give notice to the person whose

registration has been challenged, and a hearing shall

be held and a ruling made thereon. Either party

to the controversy may appeal from the decision of

the registrar to a district court of the county of

registration within thirty days after the registrar’s

decision, and the decision of the district court shall

be final. A challenged voter may continue to vote

until a final decision is made canceling his registra

tion.