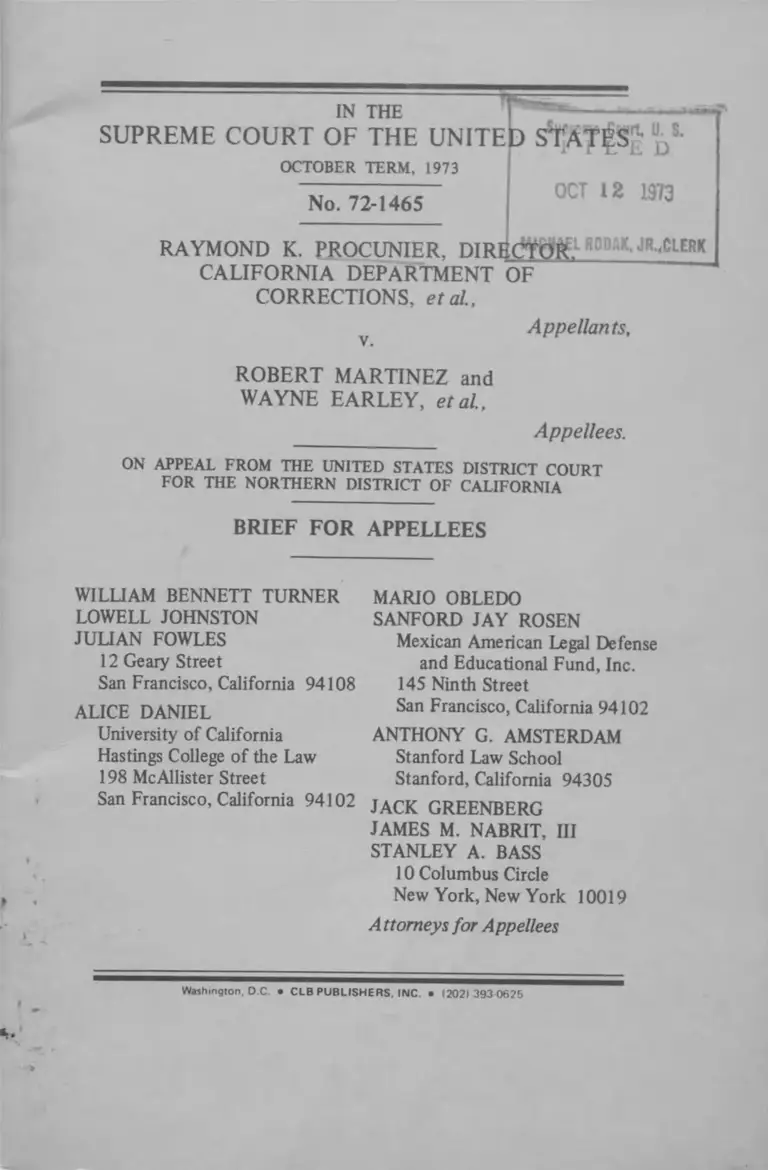

Procunier v. Martinez Brief for Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 12, 1973

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Procunier v. Martinez Brief for Appellees, 1973. 5ce2ac99-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/241b991e-e5e2-49be-ad65-55ebc0f280a5/procunier-v-martinez-brief-for-appellees. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITE

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

No. 72-1465

OST rt, U. S.

E D

OCT 12 1973

RAYMOND K. PROCUNIER, DIRH d f R0DAX- JR«CLERK

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF

CORRECTIONS, e ta l,

v.

ROBERT MARTINEZ and

WAYNE EARLEY, e ta l,

Appellants,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

WILLIAM BENNETT TURNER

LOWELL JOHNSTON

JULIAN FOWLES

12 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

ALICE DANIEL

University of California

Hastings College of the Law

198 McAllister Street

San Francisco, California 94102

MARIO OBLEDO

SANFORD JAY ROSEN

Mexican American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund, Inc.

145 Ninth Street

San Francisco, California 94102

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford Law School

Stanford, California 94305

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

STANLEY A. BASS

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellees

Washington, D C. • C LB P U B L IS H E R S . INC. • (2021 393 0625

(it

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED........................................................... ' 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................................... 2

A. Further Proceedings in the Court Below ................ 2

B. Statement of F a c t s ...................................................... 2

1. Mail Censorship..............................* ..................... 2

2. Law Student and Paraprofessional

Investigators for Attorneys ................................. 7

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT........................................................ 10

ARGUMENT:

I. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR IN

D E C L IN IN G TO ABSTAIN FROM

DECIDING ONE OF THE TWO FEDERAL

CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS PRE

SENTED, AND ABSTENTION SHOULD

NOT BE ORDERED NOW ................................................ 14

A. The District Court Was Not Required

Initially To Abstain ................................................... 14

1. Abstention is not required simply

because regulations are challenged and

invalidated, in part, on the ground of

vagueness .............................................................. 15

2. Penal Code §2600(4) is not fairly

subject to a construction that would

avoid or modify the constitutional

question ................................................................. 18

3. There is no clearly available com

parable state remedy ........................................... 21

B. Abstention Should Not Be Ordered Now .............. 22

( i i )

II. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY IN

VALIDATED APPELLANTS’ FORMER

MAIL CENSORSHIP REGULATIONS, AND

THE NEW REGULATIONS APPROVED BY

THE COURT BELOW FULLY PROTECT

EVERY LEGITIMATE INTEREST OF AP

PELLANTS ......................................................................... 23

III. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY IN

VALIDATED APPELLANTS’ FORMER AB

SOLUTE PROHIBITION AGAINST USE BY

ATTORNEYS OF LAW STUDENT OR

PARALEGAL INVESTIGATORS TO IN

TERVIEW PRISONERS ON THEIR BE

HALF, AND THE NEW REGULATION

APPROVED BY THE COURT BELOW

FULLY PROTECTS EVERY LEGITIMATE

INTEREST OF APPELLANTS ...................................... 44

CONCLUSION ................................................................................. 57

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Adams v. Carlson, ___ F.2d___ , 13 Cr. L. Rptr.

2532 (7th Cir. Aug. 23, 1973) ................................................ 47

Adams v. Carlson, 352 F.Supp 882 (E.D. 111. 1973) . . 25, 30,41

Argersinger v. Hamlin, 407 U.S. 25 (1972) ................................. 52

Arif v. McGrath, No. 71-V-1388 (E.D. N.Y. Dec. 9,

1 9 7 1 ) .............................................................................................. 55

Bachellar v. Maryland, 397 U.S. 564(1970) .............................. 33

Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1 9 6 4 ) ................................... passim

Barnett v. Rodgers, 410 F.2d 995 (D.C. Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) .............. 26, 40

Blount v. Rizzi, 400 U.S. 4 1 0 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ............................... 2 5 ,2 8 ,3 8

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ........................ 47, 48

Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444 ( 1 9 6 9 ) .................... 2 8 ,3 2 ,3 9

Brenneman v. Madigan, 343 F.Supp. 128 (N.D. Cal.

1 9 7 2 ) ........................................................................................... 32

Broadrick v. Oklahoma, ___ U .S .____ , 41 U.S.L.W.

5111 (1973) ................................................................. 17 ,2 8 ,3 5

Brown v. Chote, 411 U.S. 452 (1973) ........................................ 14

Brown v. Peyton, 437 F.2d 1228 (4th Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) ...................... 41

Burnham v. Oswald, 342 F.Supp. 880 (W.D. N.Y.

1 9 7 1 ) ............................................................................................ 38

Carothers v. Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y.

1 9 7 0 ) ................................................................ 2 0 ,2 6 ,3 0 ,3 2 ,4 0

Gutchette v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. 767 (N.D. Cal.

1 9 7 1 ) ................................................................................ 5 ,2 0 ,2 5

Coleman v. Peyton, 362 F.2d 905 (4th Cir.) cert.

denied, 385 U.S. 905(1966) 50

Connally v. General Construction Co., 269 U.S. 385

(1926) ......................................................................................... 37

Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546 ( 1 9 6 4 ) ...................................... 21 ,26

Cox v. Louisiana, 379 U.S. 536 (1 9 6 5 ) ......................................... 35

Cross v. Powers, 328 F.Supp. 899 (W.D. Wis. 1971) ........... 47, 55

Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319 (1 9 7 2 ) ................................................. 26

Damico v. California, 389 U.S. 416 ( 1 9 6 7 ) ................................. 21

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 ( 1 9 6 5 ) .............................. 15

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353 ( 1 9 6 3 ) ................................. 48

Fortune Society v. McGinnis, 319 F.Supp. 901 (S.D.

N.Y. 1970) ............................................................................ 26 ,3 0

Freedman v. Maryland, 380 U.S. 51 (1 9 6 5 ) ................................. 38

Gates v. Collier, 349 F.Supp. 881 (N.D. Miss. 1 9 7 2 ) ................ 43

Gilmore v. Lynch, 319 F.Supp. 105 (N.D. Cal. 1970),

affd sub nom. Younger v. Gilmore, 404 U.S. 15

(1971) ....................................................................... 2 5 ,4 8 ,4 9 ,5 2

Goldberg v. Kelly, 397 U.S. 254 ( 1 9 7 0 ) ................................. 25, 37

Goodwin v. Oswald, 462 F.2d 1237 (2d Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) .............. 32, 40

(Hi )

Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ................ .. 25

Gray v. Creamer, 465 F.2d 179 (3d Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ...................... 25, 26

Grayned v. City of Rockford, 408 U.S. 104 (1 9 7 2 ) ..............passim

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1 9 5 6 ) ........................................... 48

Guajardo v. McAdams, 349 F.Supp. 211 (S.D. Tex.

1 9 7 2 ) .............................................................................. 3 2 ,3 8 ,4 2

Haines v. Kemer, 404 U.S. 519(1972) ...................................... 20

Harman v. Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528 (1 9 6 5 ) ................................. 19

Healy v. James, 408 U.S. 169 ( 1 9 7 2 ) .............................. 27, 39, 40

Hillery v. Procunier,____F.Supp.____ , No. C-71

2150 S.W. (N.D. Cal. Aug. 16, 1973) .............................. 26, 40

Hooks v. Wainwright, 352 F.Supp. 163 (M.D. Fla.

1 9 7 2 ) ............................................................................................ 52

Houghton v. Shafer, 392 U.S. 639 (1968) ................................. 20

Ex parte Hull, 312 U.S. 546(1941) 47

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968) .............. 26, 40

Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969) ................................... passim

Jones v. Metzger, 456 F.2d 854 (6th Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ........................ 20

Jones v. United States, 357 U.S. 493 ( 1 9 5 8 ) .............................. 14

In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930, 500 P.2d 873 ( 1 9 7 2 ) ------ 1 8 ,2 2 ,5 0

Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1 9 5 2 ) ................ 36

Kaufman v. United States, 394 U.S. 217 (1 9 6 9 ) ......................... 47

Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589 (1 9 6 7 ) ............ passim

Laaman v. Hancock, 351 F.Supp. 1265 (D. N.H. 1 9 7 2 ) ........... 38

Lake Carriers’ Association v. MacMullan, 406 U.S.

498(1972) ................................................................................. 19

Lamar v. Kern, 349 F.Supp. 222 (S.D. Tex. 1 9 7 2 ) ................... 42

Lamont v. Postmaster General, 381 U.S. 301 (1 9 6 5 ) ................ 25

Landman v. Peyton, 370 F.2d 135 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ................... 35

( iv)

Landman v. Royster, 333 F.Supp. 621 (E.D. Va. 1971) 25, 37, 47

Lanzetta v. New Jersey, 306 U.S. 451 (1939) ........................... 37

Law Students Civil Rights Research Council v.

Wadmond, 401 U.S. 154(1971) ........................................... 17

LeVier v. Woodson, 443 F.2d 360 (10th Cir. 1971) ................ 50

Lewis v. Kugler, 446 F.2d 1343 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 1 ) ........................ 20

Undsey v. Normet, 405 U.S. 5 6 (1 9 7 3 )........................................ 19

Longv. Parker, 390 F.2d 816 (3d Cir. 1 9 6 8 ) .............................. 32

McDonnell v. Wolff, ___ F .2 d ___ , No. 72-1331

(8th Cir. Aug. 2, 1973) .........................................40, 47, 50, 55

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U.S. 668 (1963) ........... 21

Marsh v. Moore, 325 F.Supp. 392 (D. Mass. 1 9 7 1 ) ................... 50

Mead v. Parker, 464 F.2d 1108 (9th Cir. 1972) ........................ 55

Milwaukee Social Democratic Publishing Co. v.

Burleson, 255 U.S. 407 (1921) .............................................. 25

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S. 167(1961) ......................................... 21

Mooney v. Holohan, 294 U.S. 703 (1 9 3 5 ) ................................... 47

Moore v. Ciccone, 459 F.2d 574 (8th Cir. 1972) ...................... 50

Morales v. Turman, 326 F.Supp. 677 (E.D. Tex. 1 9 7 1 ) ........... 50

Morris v. Affleck, No. 4192 (D. R.I. April 20, 1972) .............. 30

Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471 (1 9 7 2 ) .............................. 25, 37

NAACP v. Alabama ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S. 288

(1964) .................................................................................... 28 ,37

NAACPv. Button, 371 U.S. 4 1 5 ( 1 9 6 3 ) ......................... 2 8 ,3 4 ,3 6

Neal v. State o f Georgia, 469 F.2d 446 (5th Cir.

1 9 7 2 ) ............................................................................................ 25

Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 ( 1 9 3 1 ) ................................. 29, 30

New York Times v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) ................... 29

Nolan v. Fitzpatrick, 451 F.2d 545 (1st Cir. 1971) .2 5 , 26, 30, 32

( V)

Nolan v. Scafati, 430 F.2d 548 (1st Cir. 1 9 7 0 ) ...................... 47, 50

Novak v. Beto, 453 F.2d 661 (5th Cir. 1 9 7 1 )........................ 52, 55

O’Malley v. Brierley, 477 F.2d 785 (3rd Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) .............. 26 ,40

Organization for a Better Austin v. Keefe, 402 U.S.

415(1971) ................................................................................. 38

Palmigiano v. Travisono, 317 F.Supp. 776 (D. R.I.

1 9 7 0 ) .......................................... 2 5 ,2 6 ,3 0 ,3 2 ,4 3

Papachristou v. City o f Jacksonville, 405 U.S. 156

(1972) 36 ,37

Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 353 (1968) . . . . 29, 39

Pierce v. LaVallee, 293 F.2d 233 (2d Cir. 1 9 6 1 ) ........................ 20

Police Department of Chicago v. Mosley, 408 U.S. 92

(1972) ............................................................................ 3 3 ,3 7 ,4 0

Preiser v. Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 475, 93 S.Ct. 1827

(1973) .................................................................................... 20,21

Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266 (1948) ...................................... 26

Remmers v. Brewer, 475 F.2d 52 (8th Cir. 1 9 7 3 ) ...................... 26

Reetz v. Bozanich, 397 U.S. 82 (1 9 7 0 ) ......................................... 19

Rivers v. Royster, 360 F.2d 592 (4th Cir. 1 9 6 6 ) ........................ 20

Rowland v. Sigler, 327 F.Supp. 821 (D. Neb. 1971),

a ff d sub nom. Rowland v. Jones, 452 F.2d 1005

(8th Cir. 1971) 26 ,40

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 ( 1 9 6 0 ) ................................. 37, 40

Shelton v. Union County Board of Commissioners,

___ F.2d___ , No. 71-151 (7th Cir. 1973) .......................... 20

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham, 394 U.S. 147 (1969) ................. 35

Smith v. California, 361 U.$. 147 (1959) ................................... 34

Smith v. Robbins, 454 F.2d 696 (1st Cir. 1 9 7 2 ) ........................ 50

Sostre v. McGinnis, 442 F.2d 178 (2d Cir. 1971),

cert, denied sub nom. Sostre v. Oswald, 404 U.S.

1049 (1971)

(v i )

30, 32, 33

Sostre v. Otis, 330 F.Supp. 941 (S.D. N.Y. 1 9 7 1 ) ...................... 38

Speiser v. Randall, 357 U.S. 513 ( 1 9 5 8 ) ........................ 2 8 ,3 4 ,3 8

Stapleton v. Mitchell, 60 F.Supp. 51 (D. Kan. 1 9 4 5 )................ 21

Stevenson v. Mancusi, 325 F.Supp. 1028 (W.D. N.Y.

1 9 7 1 ) ........................................................................................... 53

Tacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973) ...................................... 14

State ex rel. Thomas v. State of Wisconsin 55 Wis.2d

343, 198 N.W.2d 675 (1972) .............................. 25, 26, 30, 40

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88 (1 9 4 0 ) .............................. 28, 36

Tinker v. Des Moines School District, 393 U.S. 503

(1969) ............................................................................ 2 7 ,3 9 ,4 0

In re Tucker, 5 Cal.3d 171 (1971) .............................................. 52

United Mine Workers v. Illinois State Bar Association,

389 U.S. 217(1967) ................................................................. 56

United States v. Kras, 409 U.S. 434 (1973) .............................. 47

United States v. Livingston, 179 F.Supp. 9 affd, 364

U.S. 281 ( 1 9 6 0 ) ......................................................................... 19

United States v. O’Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968) ........................ 40

United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967) .............. 28, 37 ,40

United States v. Savage, __ F .2d ___ , No. 72-3145

(9th Cir. Aug. 8, 1 9 7 3 ) .............................................................. 40

United States Civil Service Commission v. National

Association of Letter Carriers, ___ U .S .____ , 41

U.S.L.W. 5 1 2 2 ( 1 9 7 3 ) .............................................................. 35

Van Erman v. Schmidt, 343 F.Supp. 337 (W.D. Wis.

1 9 7 2 ) ........................................................................................... 55

Wainwright v. Coonts, 409 F.2d 1337 (5th Cir. 1 9 6 9 ) .............. 55

Wilwording v. Swenson, 404 U.S. 249 (1971) ............................. 20

Worley v. Bounds, 355 F.Supp. 115 (W.D. N.C. 1 9 7 3 )------ 30, 41

Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519 (2d Cir. 1967) ...................... 20

Yarish v. Nelson, 27 Cal. App.3d 893, 104 Cal. Rptr.

205 (1972) 18

Younger v. Gilmore, 404 U.S. 15(1971)

Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241 (1967)

4 8 ,4 9 ,5 2

. . . 15,19

Statutes, Rules and Regulations:

42U.S.C. §1983 .............................................................................. 20

California Department o f Corrections, Director’s Rule

1205(d) ....................................................................................3 ,31

California Department of Corrections, Director’s Rule

1205(f) ...................................................................................... 6

California Department o f Corrections, Director’s Rule

1201 3 ,4

California Department of Corrections, Director’s Rule

D2401 ......................................................................................... 5

California Department of Corrections, Director’s Rule

2402(8) ...................................................................................... 3> 4

California Department of Corrections, Mail and Visit

ing Manual §MV-IV-02 ............................................................ 7

California Evidence Code §952 ...................................................... 46

California Penal Code §2600 ........................................... 18, 19, 21

California State Bar Board of Governors, Rules for

Practical Training of Law Students, Rule VII.C ................. 54

Fed. R. Civ. P. Rule 23 ................................................................... 22

Michigan Department o f Corrections, Department

Directive CC-10 (October 17, 1 9 7 2 ) ...................................... 37

Pennsylvania Bureau o f Corrections, Administrative

Directive No. 3 (effective Dec. 15, 1970) ........................... 37

Washington Office of Adult Corrections, Memoran

dum No. 70-5 (Nov. 6, 1970) ............................................ 37

Other Authorities:

American Bar Association, Code of Professional

Responsibility, Canon 3, Ethical Consideration

3-6 51 ,54

( i x )

Bergesen, California Prisoners: Rights Without

Remedies, 25 Stan. L. Rev. 1 (1973) ................ .................. 22

Brickman, Expansion of the Lawyering Process

Through a New Delivery System: The Emergence

and State o f Legal Paraprofessionalism, 71 Col. L.

Rev. 1153 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ...................................................................... 52

California Board o f Corrections, California Cor

rectional System Study: Institutions (July, 1 9 7 1 )..............42

Center for Criminal Justice, Boston University School

of Law, Model Rules and Regulations on

Prisoners’ Rights and Responsibilities ( 1 9 7 3 ) ...................... 43

Jacob and Sharma, Justice After Trial: Prisoners’

Need for Legal Services in the Criminal-

Correctional Process, 18 Kan. L. Rev. 493 (1 9 7 0 ) .............. 53

Larson, Legal Paraprofessionals: Cultivation of a New

Field, 59 A.B.A.J. 631 (1973) .............................................. 55

National Advisory Commission on Criminal Justice

Standards and Goals, Standards 2.15, 2 . 1 7 ........................... 43

Note, Prison Mail Censorship and the First Amend

ment, 81 Yale L. J. 87 ( 1 9 7 1 ) ..............................25, 37, 38, 42

Note, The Right of Expression in Prison, 40 S. Cal. L.

Rev. 407 ( 1 9 6 7 ) ......................................................................... 42

Singer, Censorship of Prisoners’ Mail and the Con

stitution, 56 A.B.A.J. 1051 (1970) .............................. 25 ,42

State Bar of California, Reports (July, 1973) ........................... 46

State Bar of California, Reports (February, 1970) .............. 9, 54

Stern, Prison Mail Censorship: A Non-Constitutional

Analysis, 23 Hastings L. J. 995 (1972) ........................ 25, 42

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX

Pertinent Excerpts from the Standards o f the

National Advisory Commission on Criminal

Justice Standards and Goals ...................................

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1973

No. 72-1465

RAYMOND K. PROCUNIER, DIRECTOR,

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF

CORRECTIONS, etal.,

Appellants,

v.

ROBERT MARTINEZ and

WAYNE EARLEY, e ta l,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

BRIEF FOR APPELLEES

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the district court should have abstained

from deciding one of the two federal constitutional

questions presented and required appellees to institute

proceedings in state court, and whether abstention should

be ordered in the present posture of the case.

2. Whether the district court properly invalidated the

mail censorship regulations involved in this case, and

2

whether the new regulations approved by the court’s final

order fully protect every legitimate interest of appellants.

3. Whether the district court properly invalidated

appellants’ absolute prohibition against use by attorneys

of law student or paraprofessional investigators to inter

view prisoners on their behalf, and whether the new

regulation approved by the court’s final order, authoriz

ing the use of investigators certified by the State Bar,

fully protects every legitimate interest of appellants.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Further Proceedings in the Court Below

Following the decision from which this appeal was

taken, the district court received proposed regulations

from appellants and further evidence presented by

appellees (A. 98-134). On July 20, 1973, the court gave

final approval to the revised regulations submitted by

appellants. Such regulations are set forth in the Supple

ment to Appendix at pp. 194-203. We submit that the

final regulations, approved over appellees’ objections

(Supp. A. pp. 204-210), fully protect every legitimate

interest of appellants.

B. Statement of Facts

Conspicuously missing from appellants’ Statement is

any mention of the factual record and evidence on which

the decision of the district court was soundly premised.

Accordingly, we here state the pertinent facts.

1. Mail censorship

The California mail censorship rules are expressly

based on the premise that mail is a “privilege”, not a

3

“right”, which may be granted or withheld in the

discretion of prison officials (A. 48, 64).

Prisoners confined in California institutions who desire

to communicate by mail are required to submit letters

to prison officials who censor them to determine whether

they conform to certain rules (A. 19,28—Admission 1).

The rules involved here are the following:

Director’s Rule 2402(8) prohibits prisoners from writ

ing letters that are, inter alia, “defamatory . . . or are

otherwise inappropriate” (A. 19,28; Exhibit C to Appel

lants’ Brief);

Director’s Rule 1201 forbids prisoners from writing

letters in which, inter alia, they “unduly complain” or

“magnify grievances” (Id .); and

Director’s Rule 1205(d) defines “contraband” to include

“any writings . . . expressing inflammatory political, ra

cial, religious, or other views or beliefs when not in the

immediate possession of the originator . . . ” Letters may

constitute contraband writings within this rule (A. 19,

28-Admission 1).

Outgoing letters submitted for mailing by prisoners

and incoming letters addressed to prisoners may be read

by mailroom staff and by other employees of the prison

(A. 19,29-Admission 2; A. 48-50). No criteria or stand

ards, other than those contained in the rules set forth

above, are furnished to the mailroom staff to guide them

in deciding whether a particular letter violates any prison

rule or policy (A. 19-20-Admission 2).

Letters found objectionable by the mailroom staff may

be rejected for a variety of reasons. For example, at

Folsom Prison the checklist used by staff to reject letters

authorizes rejection for, inter alia, “criticizing policy,

rules or officials” and “mentioning inmates by name or

number or relating gossip or incidents” ; and staff may

also reject letters for reasons they deem appropriate

4

(A. 78-79, 50-51, 72-73). The checklist used at San

Quentin also authorizes rejection of letters for a number

of reasons, including “not proper correspondence” and

“prison gossip” (A. 67, 51). The checklist used at the

institution at Vacaville specifies a number of other

reasons for rejecting correspondence, including “offensive

language” (A. 52; exhibit 4 to Procunier dep.; Supp.

A. 190). Appellant Procunier testified that rejecting

letters for these reasons is permissible under the Direc

tor’s Rules set forth above (A. 50-52).

Given the absence of standards for guiding mailroom

staff, and the broad and vague reasons deemed permiss

ible for rejecting letters, it is not surprising that prison

officers frequently reject letters that criticize them or

express opinions they disagree with. Thus, the mailroom

sergeant at Folsom Prison will reject letters as “defa

matory” (within the meaning of Director’s Rule

2402(8)), if they are

“belittling staff or our judicial system or anything

connected with the Department of Corrections”

(A. 75).

Letters will be prohibited for “magnifying grievances”

(within the meaning of Director’s Rule 1201), if they are

“belittling the staff because of their incompetency”

(A. 75). Another official has rejected numerous letters on

the ground that they contain “disrespectful comments,”

or “misrepresenting of facts,” or “derogatory remarks,”

or material that is “discriminatory or derogatory toward

any individuals or races,” or “referring to the different

employees at the institution and making allegations and

stating mistruths and so forth,” or “erroneous informa

tion,” or what the official thinks is “misinformation”

about the prison or “prison gossip” (A. 91,92,81-86, and

5

exhibits 1-8 to Morphis dep.).1 The same criteria govern

censorship of both outgoing and incoming letters (A. 86).

When a prison employee2 decides that a letter con

stitutes improper correspondence, he is authorized to

take the following actions, alone or in combination:

(a) refuse to mail the letter and return it to the

prisoner;

(b) submit a disciplinary report which may lead to

suspension of the prisoner’s mail privileges as

specifically authorized by Director’s Rule

D2401 or to more severe disciplinary punish

ment up to and including confinement in

segregation;3

(c) photocopy the letter and place it or a summary

of its contents in the prisoner’s permanent file

(A. 20,29-Admission 5; A. 59-61 ).4

1 The letters rejected are in evidence and are innocuous by any

standard. They are mostly letters to mothers, fathers or other

relatives complaining of treatment the prisoners have allegedly

received. The official rejected a letter as stating “misinformation”

even though he knew that the statements he objected to were

direct quotations from a published newspaper article, explaining

the prisoner’s reasons for withholding his consent to an “aversion

therapy” program (A. 85 and exhibits 4 and 5 to Morphis dep.).

2Censorship is done by guards assigned to mailroom duty, their

civilian helpers, members of the night watch or the officer in

charge of a lock-up unit (A. 29, 59, 73-74, 81).

3See A. 77; Supp. A. 170; A. 24, 45—Admission 24; Supp. A.

172; A. 24-25, 43-Admission 28. The severity of disciplinary

punishments in California prisons is comprehensively described in

Gutchette v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. 767 (N.D. Cal. 1971).

4Placed in plaintiff Martinez’s file, for unexplained reasons,

were copies of letters to a relative and to a federal judge (A. 59-60;

exhibits 5 and 6 to Procunier dep.).

6

Letters may be placed in a prisoner’s file even if they do

not violate any rule, if mailroom staff believe that the

letters “reveal an inappropriate attitude toward prison

staff or society or express radical political views”

(A. 21,29-Admission 7). Letters placed in a prisoner’s

file are referred to and consulted by prison classification

committees which determine the prisoner’s housing and

work assignments (A. 21,29—Admission 8). Such letters

are also available to the California Adult Authority which

decides whether and when to grant parole (A. 21,

29—Admission 9; A. 60).s

There is no effective procedure by which a prisoner

may challenge a guard’s censorship decision. Although

appellants say that the prisoner can “appeal” (A. 20,

29-Admission 6), there is no Director’s Rule establishing

any such procedure; prisoners are not informed of the

possibility of appeal; there is no hearing of any kind and

there is no provision for review by anyone other than the

censor.5 6 Regarding incoming letters rejected by staff,

there is not even a provision for notice to the prisoner

that the letter had been received at the prison and

rejected.

Despite the obvious deficiencies and invitations for

abuse contained in their rules, appellants offered no

evidence whatever, not even their opinion, to show that

5 Indeed, Director’s Rule 1205(f) specifically authorizes the

retention of “contraband” writings, which may include letters, for

referral to the Adult Authority (A. 21, 30—Admission 10; Supp. A.

172; A. 24-25, 43—Admission 28).

6 Three different officials described three completely different

and inconsistent procedures to use in seeking review of a mail

decision (A. 58-59, 76, 87), but one candidly admitted that there is

“no established policy” (Miranda dep. p. 24). Appellants keep no

records regarding rejected letters (A. 34-35).

7

there is a legitimate need for such rules, that danger to

prison security might result without them or that the

rules were reasonable or necessary to promote the orderly

functioning of the prisons. The court below expressly

found that the rules were not “reasonable and neces

sary” , were “without any apparent justification” or any

“conceivable justification on the grounds of prison

security” and “would not appear necessary to further any

of these functions [of prisons in America].” 354 F.Supp.

at 1096 (emphasis by the court).

In response to the decision of the district court,

appellants developed and submitted new censorship rules.

The rules proposed by appellants and given final approval

by the district court (Supp. A. 211-212) continue to

regulate the content of prisoner mail, but with consider

ably more specificity. The approved rules also include a

simple procedure for administrative appeals of lower-

level censorship decisions (Supp. A. 197-198). Appellants

have suggested no reasons, either here or in the district

court, why the court-approved regulations do not protect

every legitimate state interest.

2. Law student and paraprofessional

investigators for attorneys

The Mail and Visiting Manual Section MV-IV-02,

promulgated by appellant Procunier, authorizes personal

interviews of prisoners by their attorneys of record or the

designated representative of the attorney of record

(A. 22,30-Admission 17). However, the designated rep

resentative of an attorney must be either a member of the

California Bar or an investigator licensed by the State of

California (Id.). Interviews by law students or parapro

fessional assistants to attorneys are prohibited (Id.).

This rule bars interviews regardless of the qualifica

tions or identity of the student or assistant, the attorney

8

or the prisoner to be interviewed, and regardless of the

type of case, the need to use an investigator or any other

possibly relevant factor. Thus, in this very case, counsel

for appellees, who was requested by the district court to

investigate and to consider undertaking an uncom

pensated appointment in this case, requested permission

to have a supervised law student interview plaintiff

Martinez for the purpose of investigating and preparing

the case (Supp. A. 184-186, 177-182). Permission was

denied by prison officials solely on the ground that no

such interviews are permitted under their rule {Id. ).

Appellants’ rule prohibiting interviews by law students

and other supervised paraprofessionals works a substantial

inconvenience to attorneys representing prisoners or

considering whether to represent prisoners (Supp. A.

184-188). Because of the remoteness of most California

institutions, personal visits by attorneys are necessarily

rare and very inconvenient {Id.). Indeed, such visits are so

time-consuming and inconvenient that, as the court

below found, attorneys are generally reluctant to make

such visits, and this may mean that they decide not to

provide any representation. 354 F.Supp. at 1098. This is

especially true where the prisoners are indigent, as most

are, and cannot pay for the attorney’s expenses or time

in making personal visits. Of course, indigent prisoners

are financially unable not only to retain paid counsel but

also to hire licensed investigators, the only paraprofes

sionals appellants permit to interview prisoners. There is a

growing number of highly qualified and academically

trained legal paraprofessionals who are completely barred

by appellants’ rule from acting as investigators for lawyers

representing prisoners (A. 127-130).

Although appellants prohibit law students assisting

attorneys from interviewing prisoners, they permit a large

number of law students in their institutions on a regular

basis. There are law student programs at most if not all

California prisons (A. 61, 113-115, 116). Law students,

9

with only the minimal supervision of a faculty member,

are permitted to interview prisoners and assist them on

legal matters (Id.; Supp. A. 188; A. 35-39). The prison

officials make no inquiry into the qualifications of law

students in these programs, and make no security check

on them (Id.; A. 62).

In response to the decision of the court below,

appellants developed and submitted a new investigator

rule. Under the new rule proposed by appellants and

approved by the court below, law students and legal

paraprofessionals certified by the State Bar of California

may serve as investigators for attorneys (Supp. A. 198-

200). Appellants’ Brief, filed well after the final order of

the district court, inexplicably asserts that the class of

authorized investigators is much broader (pp. 24-27).

This is just untrue. Indeed, since at present there is no

procedure for State Bar certification of paraprofes

sionals,7 the only addition to the former rule consists of

State Bar certified law students. Even these students are

subject to far more stringent precautions than those

applicable to non-certified law student programs already

authorized by appellants (compare Supp. A. 198-200

with A. 113-114). Appellants have not suggested, either

here or in the district court, any reason why allowing

lawyers to utilize the services of State Bar certified law

students would interfere with any legitimate state inter

est.

7As pointed out in n. 35, infra, the State Bar has strongly

recommended legislation authorizing certification, to utilize the

services that can be provided by qualified paralegal personnel. But

since there is no such procedure presently in effect, appellants’ new

rule will not immediately result in any use of paraprofessional

investigators Under the State Bar’s existing Rules Governing the

Practical Training of Law Students, certified students are permitted

to perform a wide range of functions in the investigation,

preparation and presentation of legal matters under the supervision

of attorneys. See State Bar of California Reports (Feb. 1970).

10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I.

The district court did not err in declining to abstain

from deciding one of the two federal constitutional

questions presented-the constitutionality of the mail

censorship regulations. Neither of the arguments that

appellants now urge for abstention was presented to the

court below. In these circumstances, appellants cannot

now claim that the district court abused its equitable

discretion by proceeding to decide the constitutional

question presented.

Moreover, abstention is not required simply because

the regulations were invalidated, in part, on the ground of

vagueness. This Court has repeatedly held that abstention

is not proper in such circumstances. Here, there is no

unsettled issue of state law whose resolution could

eliminate the federal question. Nor have appellants

suggested any construction of the regulations that could

conceivably cure their vagueness. And, in any event, the

challenge here is not limited to vagueness. Further, there

is no state statute that is fairly subject to a construction

that would avoid or modify the constitutional question.

Finally, there is no clearly available and adequate state

remedy in California that could have justified the federal

court’s abstaining and thus forcing appellees to repair to

the state courts. California habeas corpus is the only state

prisoner remedy, and it would not be effective to protect

the rights involved here. Requiring appellees to institute

state proceedings would only have caused delay, expense

and frustration, and the federal constitutional question

would not have been eliminated.

Even if abstention might have been appropriate as an

initial matter in the district court-assuming the proper

11

grounds had been timely raised by appellants-abstention

should not be ordered in the present posture of the case.

Everything the abstention doctrine is designed to post

pone—premature federal proceedings involving state

officials-has already occurred here without specific

objection by appellants. And since appellants have not

contended that the new regulations submitted by them

and given final approval by the court below fail to

protect any of their legitimate interests, it would make

no sense to order the district court to abstain now.

II.

The district court properly invalidated appellants’

former mail censorship regulations. There is no conten

tion in this case that prison officials may not inspect and

read prisoner mail. The issue concerning the constitu

tionality of regulations under which guards censor and

punish prisoners for the content of their letters-the

words they use—was properly resolved by the court

below. The only provisions invalidated prohibited pris

oners from writing letters in which they “unduly com

plain,” or “magnify grievances” or express certain “views

or beliefs” or which are deemed “defamatory” or

“otherwise inappropriate.” These provisions are not

needed to serve any legitimate penal interest. Recognizing

that prisoners’ First Amendment rights may be curtailed

because of their restrictive environment, and keeping in

mind legitimate penal interests, the rules here are

nevertheless invalid because (1) they are overbroad in that

they prohibit lawful and protected expression; (2) they

are unduly vague, with the result that standardless and

discriminatory enforcement is encouraged; (3) they fail

to give fair notice of conduct that may be severely

punished; and (4) thay lack procedural safeguards against

12

suppression of protected speech through error or arbitrar

iness. A principal use of the rules has been to suppress

criticism of prison guards and their policies, regardless of

whether such criticism is valid.

The record is barren of any justification for the rules in

question, and the district court properly found, on the

evidence presented, that no legitimate penal considera

tion supported them. Furthermore, responsible correc

tional authorities throughout the nation now reject mail

censorship of the kind involved here as unsound correc

tional practice. The authorities find such censorship

unnecessary and counterproductive. The only real contro

versy among the authorities today is whether prisoner

mail should be read at all, not what contents should be

censored or punished, and that is not an issue that the

Court must now resolve.

Finally, showing more than ample deference to appel

lants, the district court gave final approval to new

regulations developed and submitted by appellants. These

regulations fully protect every legitimate state interest.

III.

The district court properly invalidated appellants’

former absolute prohibition against use by attorneys of

law student or paralegal investigators to interview pri

soners. Appellants voluntarily began permitting State Bar

certified law students to perform this function. The only

requirement added by the district court was to include

State Bar certified paralegal assistants; but since there is

presently no such paralegal certification, appellants have

not yet been required to do anything they are not already

doing voluntarily.

The decisions of this Court have firmly established the

principle that prisoners have a due process right of

13

effective access to the courts for the purpose of setting

aside invalid convictions or remedying invasions of their

constitutional rights while incarcerated. But appellants’

former rule barred all law student and paralegal assistants

to attorneys regardless of their qualifications and regard

less of the need to use them in order to provide legal

assistance to indigent prisoners. This results in denial of

effective access to the courts for such prisoners. The

California Bar and the American Bar Association have

strongly recommended the use of law students and

paralegals to assist in providing legal services to those

otherwise unable to obtain them. If use of such persons is

merely desirable as a general matter, it is absolutely

essential if indigent prison inmates are to receive vital

assistance in obtaining access to the judicial process.

Appellants here were unable to show any counter

vailing state interest to justify their rule impeding

indigent prisoners’ due process right of effective access to

the judicial process. Yet the burden of justifying the

exclusion of trained and supervised assistants to lawyers

should be greater than the burden of justifying restric

tions on “jailhouse lawyers,” which this Court struck

down in Johnson v. Avery, 393 U.S. 483 (1969). Here,

the district court gave more than adequate deference to

any legitimate interest of appellants. The new regulation

developed and submitted by appellants, which was given

final approval by the court below, fully protects every

legitimate state interest.

14

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ERR IN DECLIN

ING TO ABSTAIN FROM DECIDING ONE OF THE

TWO FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL QUESTIONS

PRESENTED, AND ABSTENTION SHOULD NOT BE

ORDERED NOW.

Appellants contend that the district court should have

abstained from deciding one of the two federal constitu

tional questions—the constitutionality of the mail censor

ship regulations (Appellants’ Brief, p. 5). Appellants do

not suggest that the court should have abstained from

deciding the other half of the case, dealing with denial of

access to investigators for attorneys. Appellants argue

that the court should have required appellees to repair to

the state courts to institute proceedings on the first issue

because (1) the mail regulations were challenged, in part,

on the ground of vagueness, and (2) a construction of

California Penal Code §2600(4) might have avoided or

modified the federal constitutional question. Neither of

these contentions was presented to the court below. We

submit that the court below was not required initially to

abstain and that, in any event, abstention should not be

ordered now.

A. The District Court Was Not Required

Initially To Abstain.

As noted above, neither of the specific arguments now

urged for abstention was made in the district court.

Appellants’ failure to raise these points below ought to

bar them from belatedly claiming that the court should

have abstained. Cf. Brown v. Chote, 411 U.S. 452 (1973);

Tacon v. Arizona, 410 U.S. 351 (1973); Jones v. United

States, 357 U.S. 493, 499-500 (1958), indicating that

15

such tactics are not favored by this Court. Since

abstention “involves a discretionary exercise of a [fed

eral] court’s equity powers,” Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S.

360, 375 (1964), and since appellants did not ask the

court below to exercise its discretion on the grounds now

urged,8 they cannot now claim that the court abused its

equitable discretion by proceeding to decide the federal

constitutional question presented.

Even if appellants did not waive their abstention

arguments by failing to present them seasonably below,

the new arguments are without merit and inconsistent

with recent precedents in this Court.

1. Abstention is not required simply because

regulations are challenged and invalidated, in

part, on the ground o f vagueness.

Appellants leap from the fact that the mail regulations

were found to be defective because they are, inter alia,

unconstitutionally vague, to the conclusion that the

district court was required to abstain until the regulations

had been authoritatively construed by a state court. This

simplistic assertion directly conflicts with this Court’s

decisions in Baggett v. Bullitt, 377 U.S. 360 (1964);

Keyishian v. Board o f Regents, 385 U.S. 589, 601, n.9

(1967); Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479, 489-490

(1965); and Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241, 252

8 In the district court appellants did make one very short and

half-hearted statement that the court should abstain. But the

statement was no more than a generality in the course of argument

on the merits that plaintiffs had not stated a claim. (See

defendants’ Memorandum of Points and Authorities in Support of

Motion to Dismiss, p. 10 (dated Sept. 8, 1972).) Neither of the

specific grounds for abstention urged here was ever presented to

the court.

16

(1967). In all these cases the Court held that abstention

was inappropriate even though the state provisions were

challenged and struck down as impermissibly vague or

overbroad. As Mr. Justice White carefully explained in

Baggett v. Bullitt, supra, a case involving provisions held

“unduly vague, uncertain and broad” (377 U.S. at 366),

the “abstention doctrine is not an automatic rule applied

whenever a federal court is faced with a doubtful issue of

state law . . .” Id. at 375. Abstention may be appropriate

when “the unsettled issue of state law principally

concern [s] the applicability of the challenged statute to a

certain person or a defined course o f conduct, whose

resolution in a particular manner would eliminate the

constitutional issue and terminate the litigation” (Id. at

376- 377) (emphasis added). But when the uncertain issue

is not a “choice between one or several meanings of a

state statute” but among an “indefinite” number of

interpretations, and the question is not coverage of

“certain definable activities” but rather the complaint is

that those affected “cannot understand” the provisions,

“cannot define the range of activities in which they might

engage in the future, and do not want to forswear doing

all that is literally or arguably within the purview of the

.vague terms” , abstention should not be ordered. Id. at

377- 78. Here, as in Baggett, “in light of the vagueness

challenge,” it is highly unlikely that any State interpreta

tion would avoid or significantly alter the constitutional

issue and, with the delay inherent in repairing to the state

courts for perhaps repeated interpretations of the vague

regulations, abstention would be “a result quite costly

where the vagueness. . . may inhibit the exercise of First

Amendment freedoms.” Id. at 379.

In the case at bar there is no unsettled issue' con

cerning the applicability of the regulations to appel

lees or to their communications by mail, “whose resolu

17

tion in a particular manner would eliminate the constitu

tional issue . . Here, as in Baggett, the choice is among

an “indefinite” number of interpretations and the

challenge is that the persons affected “cannot under

stand” what is prohibited by the regulations and “cannot

define the range” of expression which may be “literally

or arguably within the purview of the vague terms.” Thus,

for example, the prisoners cannot know what will be

prohibited as “unduly complaining” or “magnifying

grievances,” or “otherwise inappropriate.”

Appellants have suggested no possible construction of

the regulations that would cure their vagueness. Indeed,

appellant Procunier’s testimony (A. 50-52), approving

completely open-ended interpretations of the rules, ac

tually compounds their vagueness. Since he is the State

official charged with both promulgating and enforcing the

rules and “entrusted with the definitive interpretation of

the language of the Rule,” there is no reason not to

accept his constuction of the meaning. See Law Students

Civil Rights Research Council v. Wadmond, 401 U.S. 154,

161 (1971). As the Court said in Broadrick v. Oklahoma,

___ U .S.____, 41 U.S.L.W. 5111, 5116 (1973), “ Surely

a court cannot be expected to ignore these authoritative

pronouncements in determining the breadth” of the

rules. There is no doubt that the district court in this case

correctly interpreted the rules and their intent as confer

ring completely unchecked censorship power.

Furthermore, the challenge here is not limited to

vagueness. The court below also held that the regulations

were overbroad because they actually outlawed protected

speech (e.g., criticism of correctional policies), and that

they lacked essential procedural safeguards against denial

of valid expression through error or arbitrariness. 354

F.Supp. at 1097. Appellants have suggested no construc

tion of the regulations that could conceivably have

eliminated these defects.

18

2. Penal Code §2600(4) is not fairly subject to a

construction that would avoid or modify the

constitutional question.

Appellants’ contention that some construction of

California Penal Code §2600(4) by a state court might

have avoided or modified the federal constitutional

question is frivolous. Appellants have not suggested any

such construction. The statute cannot conceivably be

interpreted to govern the issues in this case, and no one,

least of all the California Attorney General, has ever

before had the temerity to say that it might provide a

remedy for prisoners in a case like this one. By its own

terms, §2600(4) deals only with the receipt by prisoners

of “newspapers, periodicals, and books” , and a provision

authorizes officials to exclude “publications or writings

and mail containing information concerning where, how,

or from whom such matter may be obtained

(emphasis added). In short, the only mail covered by the

statute concerns solicitations for obscene publications or

writings; no provision purports to regulate general corres

pondence.9

9 In contrast, subsection (2) o f §2600 expressly provides for

confidential attorney mail. While this issue was raised as a

constitutional matter in the prisoners’ complaint, we recognized

that the statute could be construed to govern this issue and

accordingly advised the district court that it should abstain until

the California Supreme Court decided a case then pending before it

(Memorandum filed July 6, 1972, p. 14). In fact, the California

court did decide that this provision of §2600 means what it says.

See In re Jordan, 1 Cal.3d 930, 500 P.2d 873 (1972).

As to general correspondence, the only remotely relevant

California state court decision assumes that prison officials have

unrestricted censorship powers. See Yarish v. Nelson, 27 Cal.

App.3d 893, 898, 104 Cal. Rptr. 205 (1972).

19

That §2600(4) was never intended to deal with general

mail censorship is made clear by recent legislative history.

In 1972, a bill was introduced specifically to amend

§2600 to grant limited freedom from mail censorship

(Senate Bill 1419). The bill passed the Legislature but

was vetoed by Governor Reagan. The bill would have

added an entirely new subsection to §2600, granting

prisoners a right to correspond essentially without limita

tion and subject to inspection only to search for

contraband or to prevent commission of a crime.1 0

Until now, no one has ever suggested that § 2600(4)

had anything whatever to do with general mail censor

ship, and it is absurd to assert that the statute could

dispose of the issues in this case. It is well settled that

because of the duplication of effort and expense and

attendant delay, abstention is appropriate only in nar

rowly limited special circumstances where a state statute

might reasonably be construed to avoid or modify the

federal constitutional question. See Lindsey v. Normet,

405 U.S. 56, 62, n.5 (1972); Lake Carriers’ Association v.

MacMullan, 406 U.S. 498, 510-11 (1972). Such a

construction must be a reasonably possible one, not a

strained and fanciful one. “ [I] f a state statute is not

fairly subject to an interpretation which will avoid or

modify the federal constitutional question, it is the duty

of a federal court to decide the federal question when

presented to it.” Zwickler v. Koota, 389 U.S. 241, 251

(1967), quoting from United States v. Livingston, 179

F.Supp. 9, 12-13, affd , 364 U.S. 281; see also Harman v.

Forssenius, 380 U.S. 528, 534-535 (1965); compare

Reetz v. Bozanich, 397 U.S. 82, 86-87 (1970) (case could 10

10 The bill was attached as an Appendix to our Motion to

Affirm or Dismiss previously filed in this Court.

20

clearly be decided on applicable and specific state

constitutional provisions).

It makes no difference that this case involves a state

correctional agency as opposed to some other state

agency. The courts have uniformly found no basis for

abstaining solely because the defendants were state prison

officials.11 Appellants’ reliance on Preiser v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 475, 93 S.Ct. 1827 (1973), is misplaced. That

case had nothing to do with abstention. The Court in

Rodriguez was faced with reconciling two federal sta

tutes, the federal habeas statute, which required exhaus

tion of state remedies, and 42 U.S.C. §1983, which did

not. The Court held that if a prisoner is challenging “ the

very fact or duration of confinement” and is seeking

“immediate or more speedy release,” habeas corpus is the

exclusive remedy. The Court distinguished prior prisoner

cases that did not require resort to state courts, Wilword-

ing v. Swenson, 404 U.S. 249 (1972), Haines v. Kerner,

404 U.S. 519 (1972), Houghton v. Shafer, 392 U.S. 639

11 See, e.g., Shelton v. Union County Board o f Commissioners,

___ F .2 d ___ , No. 71-151 (7th Cir. Aug. 7, 1973); Jones v.

Metzger, 456 F.2d 854 (6th Cir. 1972); Lewis v. Kugler, 446 F.2d

1343 (3d Cir. 1971); Wright v. McMann, 387 F.2d 519, 524-525

(2d Cir. 1967); Rivers v. Royster, 360 F.2d 592 (4th Cir. 1966);

Pierce v. LaVallee, 293 F.2d 233, 235-236 (2d Cir. 1961) (cited

with approval in Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546 (1964); Clutchette

v. Procunier, 328 F.Supp. 767 (N.D. Cal. 1971); Carothers v.

Follette, 314 F.Supp. 1014 (S.D. N.Y. 1970). Judge Kaufman

remarked in Wright v. McMann, supra, that “cases involving vital

questions of civil rights are the least likely candidates for

abstention.” 387 F.2d at 525. And Judge Mansfield in Carothers v.

Follette, supra, pointed out that since, as here, the only basis for

deciding the case was on federal constitutional grounds, “To

abstain, therefore, would merely be to postpone the inevitable.”

314 F.Supp. at 1019.

21

(1968), and Cooper v. Pate, 378 U.S. 546 (1964), on the

ground that (as in the present case) “none of the state

prisoners in those cases was challenging the fact or

duration of his physical confinement itself, and none was

seeking immediate or more speedy release from that

confinement—the heart of habeas corpus.” 93 S.Ct. at

1840. The Court also recognized that there are many civil

rights cases in which the states have strong interests, yet

initial resort to state courts is not required because no

specific federal statute, like the habeas statute, requires

going first to the state courts. 93 S.Ct. at 1838, n.10. See

McNeese v. Board o f Education, 373 U.S. 668 (1963)

(school segregation);12 Damico v. California, 389 U.S.

416 (1967) (welfare problems); Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S.

167 (1961) (police practices).

3. There is no clearly available

comparable state remedy

Finally, appellants recognize that “the availability of a

readily accessible and meaningful state remedy is a

prerequisite to the application of the doctrine of absten

tion” (Appellants’ Brief, p. 7, n.2). They assert that

California provides such a remedy but, in fact, the

availability of an adequate remedy is not at all clear. The

state has a “civil death” statute (Penal Code § 2600) that

apparently disables prisoners from maintaining actions,

12In McNeese, 373 U.S. at 674, the Court quoted with approval

from Stapleton v. Mitchell, 60 F.Supp. 51, 55 (D. Kan. 1945):

“We yet like to believe that wherever the Federal courts sit,

human rights under the Federal Constitution are always a

proper subject for adjudication, and that we have not the

right to decline the exercise of that jurisdiction simply

because the rights asserted may be adjudicated in some other

forum.”

22

like the present one, for injunctive relief. The only

recognized remedy for California prisoners is habeas

corpus. While habeas can be used to strike down plainly

invalid regulations, see In re Jordan, 7 Cal.3d 930, 500

P.2d 873 (1972), appellants have cited no authority

indicating that the kind of injunctive relief granted by the

district court here—requiring the submission of new

regulations that protect the interests of all parties-would

be available in California habeas. Further, there are real

doubts as to the practical efficacity of the habeas remedy

in California. See generally Bergesen, California Prisoners:

Rights Without Remedies, 25 Stan. L. Rev. 1 (1973).13 In

short, remitting appellees to the state courts would have

caused delay, expense and the probable frustration of

finding that no comparable remedy was available-all

with no likelihood that the vague regulations could be

authoritatively construed to eliminate the constitutional

questions.

B. Abstention Should Not Be Ordered Now

Even if abstention would have been appropriate as an

initial matter in the district court, assuming the proper

13 As one example, there is no clear or adequate provision for

pretrial discovery in California habeas, and in fact discovery of the

most relevant matters has been denied by the California courts. See

Bergesen, supra, at 21-22, n. 159; 27-28. But in the present case

appellees could not have proved their case without the discovery

authorized by the Federal Rules o f Civil Procedure. As another

example, there is no provision for maintaining a class action in

California habeas, but this case was properly brought to obtain

class relief under Rule 23 of the Federal Rules. Finally, there has

apparently never been a reported case in which a prisoner has

prevailed when the facts were in dispute, for the California courts

use procedures that virtually guarantee finding the facts against the

prisoner. See generally Bergesen, supra.

23

grounds had been timely raised by appellants, it would be

pointless to order the court below to “stay its hand”

now. As all this Court’s abstention cases indicate, the

purpose of the doctrine is to avoid the needless confron

tation of the state and federal systems. The doctrine is

designed to avoid premature federal proceedings-with

pleadings, responses by state officials, discovery, hearings

on the merits and federal court orders running against

state officials. But all this has already happened in the

present case. Everything that abstention is designed to

postpone has already occurred here-and it occurred

without appellants’ having urged the grounds for absten

tion they do in this Court. Moreover, appellants have not

complained, either in the district court or in this Court,

that any of the new regulations submitted by appellants

and approved by the court below do not protect any of

their legitimate interests. In these circumstances, when it

is impossible to undo everything that has been done

without appellants’ objection, it would make no sense to

order abstention now.

n.

THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY INVALIDATED

APPELLANTS’ FORMER MAIL CENSORSHIP

REGULATIONS, AND THE NEW REGULATIONS

APPROVED BY THE COURT BELOW FULLY

PROTECT EVERY LEGITIMATE INTEREST OF

APPELLANTS.

There is no contention in this case that prison officials

may not inspect and read prisoner mail; that is not an

issue the Court must here resolve. Nor is there any

contention that officials may not censor the content of

mail to protect prison security. The question is whether

there are any limits to their censorship power. The issue

24

concerns the constitutionality of regulations under which

prison guards censor and punish prisoners for the content

of their communications—the words they use. As will be

seen, infra, however, the only real controversy in correc

tions today is whether officials should inspect and read

mail at all, not what contents should be regulated.

In order to understand precisely what is at issue on

this appeal, it is necessary to compare the regulations

invalidated by the court below with the regulations

given final approval by the court on July 20, 1973

(Supp. A. 194-203). The difference between the

former rules and the approved rules constitutes what the

court below decided. Comparison of the rules shows that

the net effect of the proceedings below was to invalidate

the former rules prohibiting prisoners from writing letters

in which they “unduly complain,” or “magnify griev

ances” or express “inflammatory political, racial, reli

gious or other views or beliefs,” or which are “defama

tory” or “are otherwise inappropriate.” Except for these

provisions, the substance of the former rules survived

scrutiny and is contained in the rules given final approval

by the court below. Therefore, the question for review

here is whether the court below properly invalidated

these provisions.14

14 Appellants’ Brief (pp. 21-22) makes a number of misleading

references to regulations that are not at issue here. Thus, the rules

prohibiting letters concerning “criminal activity,” or “obscene

letters,” were neither challenged by appellees nor struck down by

the court below. The same is true of the ban on “foreign matter”

and “display or circulation” of “contraband” when “used to

subvert prison discipline.” Further, the prohibitions of “escape

plans” or plans for producing “explosives,” or “behavior which

might lead to violence” were neither attacked by appellees nor

invalidated by the district court.

25

The premise of these provisions was that communica

tion by mail is a “privilege,” not a “right,” which may be

granted or withheld in the discretion of prison officials

(A. 48,64). We believe this is a faulty premise, for it is

clear that the right to communicate by mail is not only

guaranteed by the First Amendment, see Blount v. Rizzi,

400 U.S. 410, 416 (1971); Lamont v. Postmaster

General, 381 U.S. 301, 305 (1965),15 but is not lost

simply by virtue of imprisonment.16 In any event, the

“right-privilege” distinction has been definitively rejected

as an analytic tool in deciding questions of important

freedoms.17

15 The unanimous decisions in Blount and Lamont both quoted

with approval Mr. Justice Holmes’ view that “the use of the mails is

almost as much a part o f free speech as the right to use our

tongues.” Milwaukee Social Democratic Publishing Co. v. Burleson,

255 U.S. 407, 437 (1921). See also the opinion of Mr. Justice

Brandeis, rejecting the view that use o f the mails is merely a

privilege and not a right. 255 U.S. at 427.

16 See, e.g., Gray v. Creamer, 465 F.2d 179, 186 (3d Cir. 1972);

Nolan v. Fitzpatrick, 451 F.2d 545 (1st Cir. 1971); Adams v.

Carlson, 352 F.Supp. 882, 896 (E.D. 111. 1973); Palmigiano v.

Travisono, 314 F.Supp. 776 (D. R.I. 1970); Carothers v. Follette,

314 F.Supp. 1014, 1023 (S.D. N.Y. 1970); State ex rel. Thomasv.

State of Wisconsin, 55 Wis.2d 343, 198 N.W.2d 675 (1972); cf

Neal v. State o f Georgia, 469 F.2d 446, 450 (5th Cir. 1972); see

generally Note, Prison Mail Censorship and the First Amendment,

81 Yale L. J. 87 (1971); Stern, Prison Mail Censorship: A

Non-Constitutional Analysis, 23 Hastings L. J. 995 (1972); Singer,

Censorship o f Prisoners’ Mail and the Constitution, 56 A.B.A. J.

1051 (1970). Indeed, even appellants profess to recognize the

value, from a corrections viewpoint, of relatively free prisoner mail

(A. 65—Policy Regarding Mail; Appellants’ Brief, p. 23, n. 7).

17 See, e.g., Morrissey v. Brewer, 408 U.S. 471,481-482 (1972);

Graham v. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365, 374 (1971); Goldberg v.

Kelly, 397 U.S. 254, 262 (1970); Landman v. Royster, 333

F.Supp. 621, 644-645 (E.D. Va. 1971); Clutchette v. Procunier,

328 F.Supp. 767, 779 (N.D. Cal. 1971); Gilmore v. Lynch, 319

F.Supp. 105, 108 (N.D. Cal. 1970), affd sub nom. Younger v.

Gilmore, 404 U.S. 15 (1971).

26

Appellants concede, as they must, that “a prisoner

does not shed all his First Amendment rights at the

prison gates” (Appellants’ Brief, p. 15).18 But instead of

explaining the extent to which prisoners’ First Amend

ment rights must be curtailed because of legitimate penal

interests, appellants simply cite the famous dictum from

Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266, 285 (1948): “ Lawful

incarceration brings about the necessary withdrawal or

limitation of many privileges and rights, a retraction

justified by the considerations underlying our penal

system.” 19 This begs the question, which is what with

drawals or limitations are “necessary” because of what

penal “considerations.” Similarly, the “ test” proposed by

appellants-whether the regulation “lacks support in any

rational and constitutionally acceptable concept of a

18 See Cruz v. Beto, 405 U.S. 319 (1972); Cooper v. Pate, 378

U.S. 546 (1964); O’Malley v. Brierley, A ll F.2d 785 (3d Cir.

1973); Remmers v. Brewer, 475 F.2d 52, 54 (8th Cir. 1973); Gray

v. Creamer, 465 F.2d 179, 186 (3d Cir. 1972); Nolan v.

Fitzpatrick, 451 F.2d 545 (1st Cir. 1971); Barnett v. Rodgers, 410

F.2d 995, 1000 (D.C. Cir. 1969); Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d

529, 541 (5th Cir. 1968); Rowland v. Sigler, 327 F.Supp. 821 (D.

Neb. 1971), aff’d 452 F.2d 1005 (8th Cir. 1971); Fortune Society

v. McGinnis, 319 F.Supp. 901 (S.D. N.Y. 1970); Palmigiano v.

Travisono, 317 F.Supp. 776 (D. R.I. 1970); Carothers v. Follette,

314 F.Supp. 1014, 1023 (S.D. N.Y. 1970); Hillery v. Procunier,

___ F.Supp.___ , No. C-71 2150 SW (N.D. Cal. Aug. 16, 1973)

(3-judge court); State ex rel. Thomas v. State of Wisconsin, 55

Wis.2d 343, 198 N.W.2d 675 (1972).

19Price had absolutely nothing to do with the rights of

prisoners vis-a-vis prison officials. The case actually held that a

federal court o f appeals has power to order a prisoner brought

before the court to argue his own appeal. 334 U.S. at 278, 284.

The decision sheds no light on the appropriate standards o f judicial

review of prison regulations.

27

prison system”—also begs the question of what is

“constitutionally acceptable.”

The district court assumed that prisoners’ First

Amendment rights exist only to the extent that their

exercise is consistent with legitimate penal interests. But

the record here shows that the censorship rules were not

in fact needed to serve any legitimate interest. The court

below found that they are not “reasonable and neces

sary” to serve any such interest, that they are “without

any apparent justification” or any “conceivable justifica

tion on the grounds of prison security” and that they

“would not appear necessary to further any of these

functions [of prisons in America].” 354 F.Supp. at 1096

(emphasis by the court).

We recognize that First Amendment rights may have

legitimate limits in the prison context. As Mr. Justice

Powell has explained, “First Amendment rights must

always be applied ‘in light of the special characteristics of

the . . . environment’ in the particular case.” Healy v.

James, 408 U.S. 169, 180 (1972); see also Tinker v. Des

Moines School District, 393 U.S. 503, 506 (1969).

Keeping the prison environment in mind, and giving due

deference to legitimate penal interests, we submit that

the mail censorship provisions involved here are invalid

under familiar principles: (1) they are overbroad in that

they prohibit lawful and protected expression; (2) they

are unduly vague, with the result that standardless and

selective enforcement against unpopular causes and pris

oners is encouraged; (3) they fail to give fair notice of

punishable conduct; and (4) they lack essential procedur

al safeguards against denial of First Amendment rights

through error or arbitrariness.

28

1. Overbreadth and Prohibition

o f Lawful Expression

The rules invalidated by the district court are not

“narrowly drawn” regulations representing “a considered

legislative judgment” that particular expression “has to

give way to other compelling needs of society.” See

Broadrick v. Oklahoma, ____U.S. ____, 41 U.S.L.W.

51 11, 51 14 (1973). The rules do not provide the

necessary “sensitive tools” to carry out the “separation

of legitimate from illegitimate speech.” See Blount v.

Rizzi, 400 U.S. 410, 417 (1971); Speiser v. Randall, 357

U.S. 513, 525 (1958). They disregard the established

principle that “government may regulate in the [First

Amendment] area only with narrow specificity” and that

“precision of regulation must be the touchstone in an

area so closely touching our most precious freedoms.”

See NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 433, 438 (1963);

Keyishian v. Board o f Regents, 385 U.S. 589, 603-604

(1967); United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 259, 265

(1967); see generally Grayned v. City o f Rockford, 408

U.S. 104 (1972) (summary of overbreadth principles and

precedents of this Court). They are “overbroad” in that

they “sweep unnecessarily broadly and thereby invade

the area of protected freedoms.” See NAACP v. Alabama

ex rel. Flowers, 377 U.S. 288, 307 (1964) (Harlan, J.); see

also Brandenburg v. Ohio, 395 U.S. 444, 448 (1969);

Thornhill v. Alabama, 310 U.S. 88, 97 (1940); Grayned

v. City o f Rockford, supra, 408 U.S. at 114 (“in its reach

it prohibits constitutionally protected conduct” ); United

States v. Robel, supra, 389 U.S. at 266.

In short, the rules do not narrowly proscribe only

expression that falls outside the ambit of the First

Amendment. They prohibit a broad range of expression

that is clearly entitled to First Amendment protection.

29

We are not dealing here with obscenity or libel or

“ fighting words.” We are dealing with thoughts expressed

in prisoner mail to relatives or friends-mainly outgoing

letters, not matters circulated within the walls—that the

prison censor disapproves as “unduly complaining,”

“magnifying grievances” or “otherwise inappropriate.”

As one example of the overbroad sweep of these

provisions, a principal use of the rules has been to

suppress criticism of prison guards and their policies

(regardless of whether such criticism is valid). At Folsom

Prison officials bluntly announce that letters “criticizing

policy, rules or officials” violate the rules, and appellant

Procunier testified that rejecting letters for this reason is

authorized by the rules (A. 50-52). Letters are rejected

for “belittling” staff or “the judicial system” or, indeed,

“anything connected with the Department of Correc

tions” (A. 75). Further, letters “magnify grievances”

within the meaning of the rule if they are “belittling the

staff because of their incompetency” (Id.). Letters may

also be rejected for containing “misinformation” or

“prison gossip,” for being “derogatory to any individ

u a ls” or “ militant” or merely “inappropriate”

(A. 91,92,81-86 and exhibits 1-8 to Morphis dep.). What

the censoring guards consider “prison gossip” or “in

appropriate” could well be a prisoner’s complaint of

mistreatment or his fears thereof. As the court below

found, the rules can be and are used to suppress prisoner

grievances, and this obviously conflicts with the First

Amendment rights of expression and to petition for

redress of grievances.

This Court has frequently recognized that the First

Amendment protects criticism of public officials, even

when untrue. See, e.g., New York Times v. Sullivan, 316

U.S. 254 (1964); Pickering v. Board o f Education, 391

U.S. 353, 570 (1968); Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697,

30

710 (1931 ).20 Here, the rules prohibit such criticism

regardless of its truth. This has unfortunately been

common in prison mail censorship, but now the lower

courts have resoundingly condemned the suppression of

prisoners’ complaints about official conduct or policies.