Watson v. City of Memphis Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 27, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. City of Memphis Opinion, 1963. b634fec1-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/243807ef-4683-4afd-a4a8-1924003e3473/watson-v-city-of-memphis-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

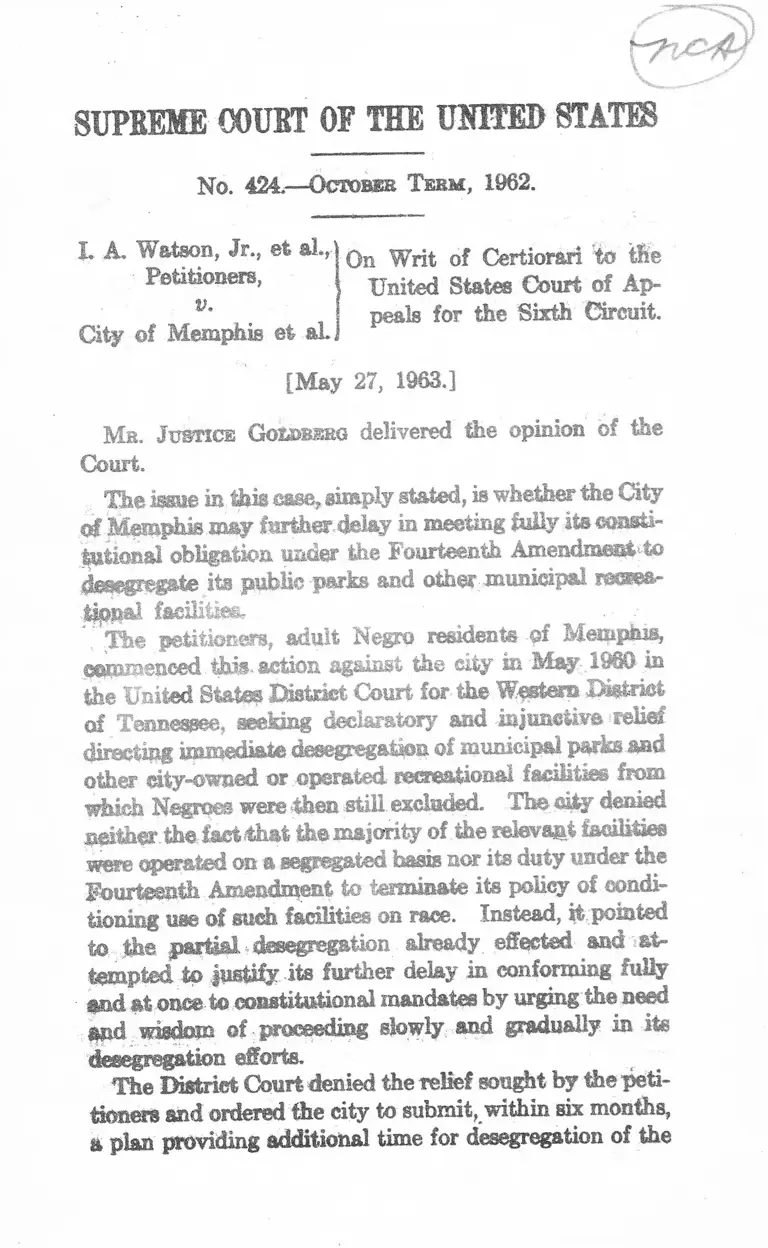

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

No. 424.— October Teem , 1962.

1. A. Watson, Jr., et aL,

Petitioners,

v.

City o f Memphis et aL

On Writ o f Certiorari to the

United States Court o f Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit.

[May 27, 1963.]

Ma. Justice GoMjbkhg delivered the opinion of the

Court.

The in this ewe, simply stated, is whether the City

o f Memphis may further delay in meeting fully its consti

tutional obligation under the Fourteenth Amendment to

desegregate its public -parks and other-municipal recrea

tional fasiEtieSr

' ".The petitionsrs, adult Negro residents o f Memphis,

cesmiBenced this action against the city in M ay 1960 in

the United States District Court for the Western District

o f Tennessee, seeking declaratory and injunctive relief

directing ijamediate desegregation o f municipal paths m d

other city-owned or operated, recreational facilities from

which Negroes were -then still excluded. The city denied

neither the fact that the m ajority o f the relevant facilities

were operated on a basis nor its duty under the

Fourteenth Amendment to terminate its policy of condi

tioning use o f such facilities on race. Instead, it pointed

to the partial desegregation already effected and at

tempted to justify its further delay in conforming fulty

«nd at once to constitutional mandates by urging the need

apd wisdom of proceeding slowly and gradually in its

desegregation efforts.

The District Court denied the relief sought by the peti

tioners and ordered the city to submit, within six months,

a plan providing additional time for desegregation o f the

2 WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS.

relevant facilities.1 The Court o f Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit affirmed. 303 F. 2d 863. We granted certiorari,

371 U. S. 909, to consider the important question pre

sented and the applicability here o f the principles enun

ciated by this Court in the second Brown decision, Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, upon which the

courts below relied in further delaying complete vindica

tion of the petitioners’ constitutional rights.

We find the second Brown decision to be inapplicable

here and accordingly reverse the judgment below.

I.

It is important at the outset to note the chronological

context in which the city makes its claim to entitlement to

additional time within which to work out complete elimi

nation of racial barriers to use o f the public facilities here

involved. It is now more than nine years since this Court

held in the first Brown decision, Brown v. Board o f Edu

cation, 347 U. S. 483, that ra d ii segregation in state pub

lic schools violates the Equal Protection Clause o f the

Fourteenth Amendment. And it was almost eight years

ago— in 1955, the year after the decision on the merits in

Sroaw—that the constitutional proscription o f state en

forced racial segregation was found to apply to public

recreational facilities. See Dawson v. Mayor and City

Council o f Baltimore, 220 F. 2d 386, aff’d, 350 U. S. 877;

see also Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Assn., 347

U. S. 971.

Thus, the applicability here o f the factors and reason

ing relied on in framing the 1955 decree in the second

Brown decision, supra, which contemplated the possible

need o f some limited delay in effecting total desegregation

1 The plan ultimately formulated, though not part of the record

here, was described in oral argument before the Court of Appeals.

It does not provide for complete desegregation o f all facilities until

1971.

WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS. 3

of public schools, must be considered not only in the con

text of factual similarities, if any, between that case and

this one, but also in light of the significant fact that

the governing constitutional principles no longer bear

the imprint of newly enunciated doctrine. In consider

ing the appropriateness o f the equitable decree entered

below inviting a plan calling for an even longer delay in

effecting desegregation, we cannot ignore the passage of

a substantial period o f time since the original declara

tion of the manifest unconstitutionality of racial practices

such as are here challenged, the repeated and numerous

decisions giving notice of such illegality,2 and the many

intervening opportunities heretofore available to attain

the equality of treatment which the Fourteenth Amend

ment commands the States to achieve. These factors

must inevitably and substantially temper the present

import of such broad policy considerations as may have

underlain, even in part, the form of decree ultimately

framed in the Brown case. Given the extended time

which has elapsed, it is far from clear that the mandate

o f the second Brown decision requiring that desegregation

proceed with “ all deliberate speed” would today be fully

satisfied by types of plans or programs for desegregation

o f public educational facilities which eight years ago might

j 2 See, e. g., Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220

F. 2d 386, aff’d, 350 U. S. 877 (beaches and bathhouses); New Or

leans City Park Improvement Asm. v. Detiege, 252 F. 2d 122, aff’d,

358 U. S. 54 (golf courses and other facilities); City of St. Petersburg

v. Almp, 238 F. 2d 830 (beach and swimming pools); Tate v. Depart

ment of Conservation and Development, 133 F. Supp. 53, aff’d, 231

F. 2d 615, cert, denied, 352 U. S. 838 (parks); Moorhead v. City of

Fort Lauderdale, 152 F. Supp. 131, aff’d, 248 F. 2d 544 (golf course);

Fayson v. Beard, 134 F. Supp. 379 (parks); Holley v. City of Ports

mouth, 150 F. Supp. 6 (golf course); Ward v. City of Miami, 151 F.

Supp. 593 (golf course); Willie v. Harris County, 202 F. Supp. 549

(park). It is noteworthy that in none of these cases was the possi

bility of delay in effecting desegregation even considered.

4 WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS.

have been deemed sufficient. Brown never contemplated

that the concept o f “ deliberate speed” would countenance

indefinite delay in elimination o f racial barriers in schools,

let alone other public facilities not involving the same

physical problems or comparable conditions.

II.

When, in 1954, in the first Brown decision, this Court

declared the constitutional impermissibility o f racial

segregation in public schools, it did not immediately frame

a decree, but instead invited and heard further argument

on the question o f relief. In its subsequent opinion, the

Court noted that “ [f]u ll implementation of these [appli

cable] constitutional principles may require solution of

varied and local school problems” and indicated an appro

priate scope for the application of equitable principles

consistent with both public and private need and for

“exercise o f [the] . . . traditional attributes o f equity

power.” 349 U. S., at 299-300. The District Courts to

which the cases there under consideration were remanded

were invested with a discretion appropriate to ultimate

fashioning o f detailed relief consonant with properly cog

nizable local conditions. This did not mean, however,

that the discretion was even then unfettered or exercisable

without restraint. Basic to the remand was the concept

that desegregation must proceed with “all deliberate

speed,” and the problems which might be considered and

which might justify a decree requiring something less than

immediate and total desegregation were severely de

limited. H ostility to the constitutional precepts under

lying the original decision was expressly and firmly

pretermitted as such an operative factor. Id., at 300.

The nature o f the ultimate resolution effected in the

second Brown decision largely reflected no more than a

recognition o f the unusual and particular problems in

hering in desegregating large numbers of schools through

WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS. 5

out the country. The careful specification of factors

relevant to a determination whether any delay in com

plying fully and completely with the constitutional man

date would be warranted demonstrated a concern that

delay not be conditioned upon insufficient reasons or, in

any event, tolerated unless it imperatively and eompel-

lingly appeared unavoidable.

This case presents no obvious occasion for the appli

cation of Brown. We are not here confronted with

attempted desegregation of a local school system with

any or all of the perhaps uniquely attendant problems,

administrative and other, specified in the second Brown

decision as proper considerations in weighing the need

for further delay in vindicating the Fourteenth Amend

ment rights of petitioners.® Desegregation of parks and

other recreational facilities does not present the same

kinds of cognizable difficulties inhering in elimination of

racial classification in schools, at which attendance is com

pulsory, the adequacy of teachers and facilities crucial,

and questions o f geographic assignment often of major

significance.* 4

8 The factors set out by the Court in the second Brown decision

were ‘ ‘problems related to administration, arising from the physical

condition of the school plant, the school transportation system, per

sonnel, revision of school districts and attendance areas into com

pact units to achieve a system of determining admission to the public

schools on a nonracial basis, and revision o f local laws and regulations

which may be necessary in solving the foregoing problems.” 349

U. S., at 300-301.

4 Recognition o f the possible need for delay has not even been

extended to desegregation of state colleges or universities in which

like problems were not presented. See, e. g., Florida ex rel. Hawkins

v. Board of Control, 350 U. S. 413, where, in remanding on the

authority of Brown, this Court said that “ [a]s this case involves the

admission of a Negro to a graduate professional school, there is no

reason for delay. He is entitled to prompt admission under the rules

and regulations applicable to other qualified candidates.” 350 U. S.,

at 414. See also Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1. Similarly, both before

6 WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS.

M ost importantly, o f course, it must be recognized that

even the delay countenanced by Brown was a necessary,

albeit significant, adaptation o f the usual principle that

any deprivation of constitutional rights calls for prompt

rectification. The rights here asserted are, like all such

rights, present rights; they are not merely hopes to

some future enjoyment of some formalistic constitutional

promise. The basic guarantees o f our Constitution are

warrants for the here and now and, unless there is an

overwhelmingly compelling reason, they are to be

promptly fulfilled.8 The second Brown decision is but

a narrowly drawn, and carefully limited, qualification

upon usual precepts o f constitutional adjudication and is

not to be unnecessarily expanded in application.

Solely because o f their race, the petitioners here have

been refused the use o f city-owned or operated parks

and other recreational facilities which the Constitution

mandates be open to their enjoyment on equal terms

with white persons. The city has effected, continues to

effect, and claims the right or need to prolong patently

unconstitutional racial discriminations violative o f now 5 *

and after Brown, delay Isas neither been-siqggeeted nor countenanced

in eliminating operation of racial barriers with respect to trsiMporta-

tion, e. g., Boynton v. Virginia, 864 IT. S. 454; Hendersons. United

States, 339 U. S. 816; Morgan v. Virginia, 328 IT. 8 ; 373; Browder v.

Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, aff’d, 352 U. S. 908, voting, e. g., SchmU

v. Davis, 336 U. S. 933; Smith v, AUwright, 321 TJ, 8, 649, racial

zoning of property, e. g., City of Richmond v . Beans, 281 U S. 704;

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60, or employment rights and union

representation, e. g., Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard,

343 U. 8. 768.

5 This principle was well established even under the now discarded

“separate but equal” doctrine. See, e. g., McLaurm v. Oklahoma

State Regents for Higher Education, 339 U, S. 637, 642; Sweatt v

Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 635; Sipuel v. Board of Regents of University

of Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631, 632-633. See also Florida ex rd.

Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U. S. 413, 414, and notes 2 and 4,

supra.

WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS. 7

long-declared and well-established individual rights. The

claims o f the city to further delay in affording the peti

tioners that to which they are clearly and unquestionably

entitled cannot be upheld except upon the most con

vincing and impressive demonstration by the city that

such delay is manifestly compelled by constitutionally

cognizable circumstances warranting the exercise o f an

appropriate equitable discretion by a court. In short,

the city must sustain an extremely heavy burden of proof.

Examination o f the facts o f this ease in light o f the

foregoing discussion discloses with singular clarity that

this burden has not been sustained; indeed, it is patent

from the record that the principles enunciated in the

second Brown decision have absolutely no application

here.

III.

The findings o f the District Court disclose an unmis

takable and pervasive pattern o f local segregation, which,

in fact, the city makes no attempt to deny, byt merely

to justify as necessary for the time being. Memphis owns

181 paries, all o f which are operated by the Memphis

Park Commission. Of these, only 25 were at the time

o f trial open to use without regard to race; 6 58 were re

stricted to use by whites and 25 to use by Negroes; the

fpjinaining 23 parks were undeveloped raw land. Subject

to exceptions, neighborhood parks were generally segre

gated according to the racial character o f the area in which

located. The City Park Commission also operates a num

ber o f additional recreational facilities, by far the largest

* These figures, and others referred in the text, apparently repre

sent the total extent of progress, as of the time o f trial, toward

desegregation o f recreational facilities since this Court's decision

eight years ago outlawing the practices here in question. So far as

appears, none o f the relevant facilities were open for use without

regard to race prior to 1955, and, hr fact, several new parks have

been opened on a segregated baas since that time.

8 WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS.

share of which were found to be racially segregated.

Though a zoo, an art gallery and certain boating and other

facilities are now desegregated, about two-thirds (40) of

the 61 city-owned playgrounds were at the time o f trial re

served for whites only, and the remainder were set aside

for Negro use. Thirty of the 56 playgrounds and other

facilities operated by the municipal Park Commission on

property owned by churches, private groups, or the School

Board were set aside for the exclusive use of whites, while

26 were reserved for Negroes. All 12 of the municipal

community centers were segregated, eight being available

only to whites and four to Negroes. Only two o f the

seven city golf courses were open to Negroes; play on

the remaining five was limited to whites. While several

o f these properties have been desegregated since the filing

o f suit, the general pattern o f racial segregation in such

public recreational facilities persists.7

The city asserted in the court below, and states here,

that its good faith in attempting to comply with the re

quirements o f the Constitution is not in issue, and con

tends that gradual desegregation on a facility-by-facility

basis is necessary to prevent interracial disturbances, vio

lence, riots, and community confusion and turmoil. The

compelling answer to this contention is that constitu

tional rights may not be denied simply because of hos

tility to their assertion or exercise. See Wright v. State

of Georgia, ----- U. S. -----; Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U. S. 294, 300. Cf. Taylor v. Louisiana, 370

U. S. 154. As declared in Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S.

1, 16, “ law and order are not . . . to be preserved by

depriving the Negro children o f their constitutional

rights.” This is really no more than an application of

a principle enunciated much earlier in Buchanan v. War-

7 It is not entirely clear precisely how many properties have since

trial actually been desegregated and how many were merely changed

from “ white-only” to “ Negro-only” use in line with changes in neigh

borhood racial composition.

WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS. 0

ley, 245 U. S. 60, a case dealing with a somewhat different

form of state-ordained segregation— enforced separation

o f Negroes and whites by neighborhood. An unanimous

Court, in striking down the officially imposed pattern of

racial segregation there in question, declared almost a

half-century ago:

“ It is urged that this proposed segregation will

promote the public peace by preventing race con

flicts. Desirable as this is, and important as is the

preservation o f the public peace, this aim cannot be

accomplished by laws or ordinances which deny

rights created or protected by the Federal Constitu

tion.” 245 U. S., at 81.

Beyond this, however, neither the asserted fears of

violence and tumult nor the asserted inability to preserve

the peace were demonstrated at trial to be anything more

than personal speculations or vague disquietudes of city

officials. There is no indication that there had been any

violence or meaningful disturbances when other recrea

tional facilities had been desegregated. In fact, the only

evidence in the record was that such prior transitions had

been peaceful.8 The Chairman o f the Memphis Park

Commission indicated that the city had “been singularly

blessed by the absence of turmoil up to this time on this

race question” ; notwithstanding the prior desegregation

o f numerous recreational facilities, the same witness

could point as evidence o f the unrest or turmoil which

would assertedly occur upon complete desegregation of

such facilities only to a number of anonymous letters and

phone calls which he had received. The Memphis Chief

o f Police mentioned without further description some

“ troubles” at the time bus service was desegregated and

8 Nor, contrary to predictions, does it appear that violence or dis

ruption of any kind ensued upon elimination of racial barriers to use

of certain additional facilities subsequent to trial.

10 WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS.

referred to threatened violence in connection with a

“ sit-in” demonstration at a local store, but, beyond mak

ing general predictions, gave no concrete indication

of any inability o f authorities to maintain the peace.

The only violence referred to at any park or recrea

tional facility occurred in segregated parks and was not

the product o f attempts at desegregation. Moreover,

there was no factual evidence to support the bare testi

monial speculations that authorities would be unable to

cope successfully with any problems which in fact might

arise or to meet the need for additional protection should

the occasion demand.

The existing and commendable goodwill between the

races in Memphis, to which both the District Court and

some of the witnesses at trial made express and emphatic

reference as in some inexplicable fashion supporting the

need for further delay, can best be preserved and extended

by the observance and protection, not the denial, of the

basic constitutional rights here asserted. The best guar

antee of civil peace is adherence to, and respect for, the

law.

The other justifications for delay urged by the city or

relied upon by the courts below are no more substantial,

either legally or practically. It was, for example, asserted

that immediate desegregation o f playgrounds and parks

would deprive a number of children— both Negro and

white— of recreational facilities; this contention was ap

parently based on the premise that a number o f such

facilities would have to be closed because o f the inade

quacy of the “ present” park budget to provide additional

“ supervision” assumed to be necessary to operate unsegre

gated playgrounds. As already noted, however, there

is no warrant in this record for assuming that such added

supervision would, in fact, be required, much less that

police and recreation personnel would be unavailable to

WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS. 11

meet such needs if they should arise.9 More significantly,

however, it is obvious that vindication o f conceded con

stitutional rights cannot be made dependent upon any

theory that it is less expensive to deny than to afford

them. W e will not assume that the citizens o f Memphis

accept the questionable premise im plicit in this argument

or that either the resources o f the city are inadequate, or

its government unresponsive, to the needs o f all o f its

citizens.

In support o f its judgment, the District Court also

pointed out that the recreational facilities available for

Negroes were roughly proportional to their number and

therefore presumably 'adequate * to meet their needs.10

W hile the record does not clearly support this, no more

need be said than that, even if true, it reflects an imper

missible obeisance to the now thoroughly discredited doc

trine o f “separate but equal” The sufficiency o f Negro

facilities is beside the point; it is the segregation by race

that is unconstitutional.

'Finally, the District Court defewed ruling as to the

propriety o f ordering elimination o f raemibarriera at one

facility, an art museum, pendffiglniti&tkm of, and deci-

rion in, a state court action to construe a racially restric

* Except fo r the mention ©f-sosne -extra poBeeihfen assignee! to duty

at the city zoo, no showing was, made even that additional super

vision was necessary or provided at facilities wbieh had been desegre

gated previously.

' 10 Approximately 3?% ’ o f Memphis’ 500,000 residents are Negroes;

contrary to the apparent assumption o f the trial court, the recrea

tional facilities available to Negroes were not at the time of trial all

quantitatively proportional to their number and their complete or

partial exclusion from certain other facilities evidenced a substantial

qualitative difference. 'Moreover, there was testimony from Negro

witnesses that they were excluded from golf courses and playgrounds

more convenient to their placesbf residence than other like facilities

open to them.

12 WATSON v. CITY OF MEMPHIS,

tive covenant contained in the deed o f the property to

the city. Of course, the outcome of the state suit is

irrelevant to whether the city may constitutionally en

force the segregation, regardless o f the. effect which de

segregation may have on its title. C f. Pennsylvania v.

Board oj Trusts., 353 U. S, 23GL In any event, there is no

reason to believe that the restrictive provision will be

invoked. The museum has already been, opened to

Negroes one day a week without complaint.11

Since the city has completely failed to demonstrate any

compelling or conviwring, .resspn requiring further delay

m implementing the constitutional proscription e£ segre

gation, o f publicly owned or operated recreational facil

ities, there is n ocau se whatsoever - to depart from the

generally operative and here efearly con ti«lfeg ,:| ^ sip l@

that constitutional rights,*®..-to be promptly vindicated.

The continued denM 'to- petitioners o f the u se-'of:eity

facilities solely because o f their race is without war-

m at. Under the facts in this case,tbeJ>istJ3ct Court's

undoubted discretion in the fashioning arad iasa?#' o f

equitable. relief, was- not -cafied'into p k y ; gather, t& am tr

t im judicial action was required to viadie#e, plai|i and

present constitutional rights Today, no less than 50

years ago, the solution to the problems growing out o f

race relations “cannot be promoted by deprivhog eitkens

o f their»eers^itutional right® and privileges,” Buchanan v.

Worley, mpra, 246' U. S., at 80-81.

The judgment below must be and is reverted and the

cause is remanded for further proceedings consistent

herewith.

Revermd.

11 The aty also asserted in the District Court that delay was sup

ported by the fact that desegregation o f the Fairgrounds would result

is & substantial less of revenues therefrom and would be unfair to

contract concessionaires. This claim appears to have bees mooted

by the intervening elimination of racial restrictions at that facility,

seemingly without difficulty.