Brown v. Board of Education Summary of Decision

Unannotated Secondary Research

May 17, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Brown v. Board of Education Summary of Decision, 1954. f93ae9db-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2448795b-2355-4340-bdb5-ee62d01170bf/brown-v-board-of-education-summary-of-decision. Accessed February 19, 2026.

Copied!

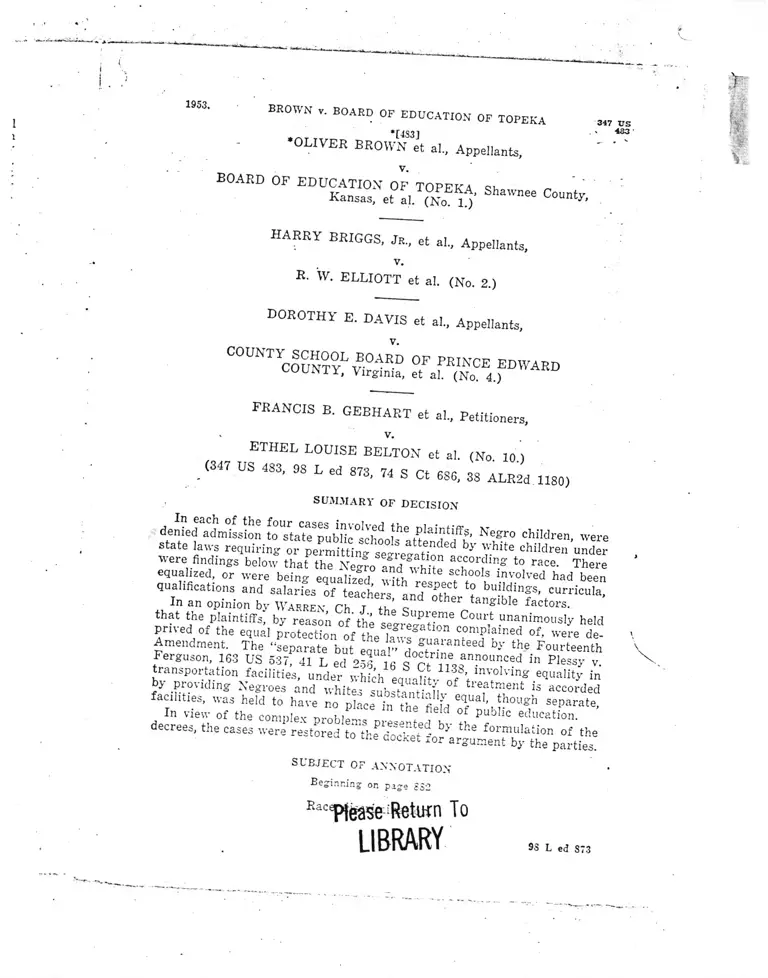

1953.

BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA

*[4S31

‘ OLIVER BROWN et ah, Appellants,

b o a r d o f e d u c a t i o n o f TOPER A fu _ ' '

Kansas, et al ( N o 1) ShaWlee C° Unt^

347 V S

x 433 •

HARRY BRIGGS, Jr ., et al., Appellants,

v.

R. W. ELLIOTT et al. (No. 2.)

DOROTHY E. DAVIS et al., Appellants,

v.

C°U N TY SCHOOL BOARD OP PRINCE EDWARD

UUUISTY, Virginia, et al. (No. 4.)

FRANCIS B. GEBHART et al., Petitioners,

ETHEL LOUISE BELTON et al. (No. 10 )

(347 US 483, 9S L ed 873, 74 S Ct 6S6, 38 ALR2d 1180)

SUMMARY OF DECISION

were

state laws requiring or permitting s p w te.nded by white children under

were findings below that the Negfo and white a<5Jor{lin.ar to race- There

equalized, or were bein- eaualize 1 hlte sf hools involved had been

qualifications and salaries of teachers anTSh* bu.i[din° s> curricula,

In an opinion bv W arr en Ch I tv,' f 6r tan° lble factors,

that the plaintiffs; by reason of the seC T eeS® unanimously held

Pnved of the equal protection of thelaws , cfomJ,I« ned of> were de-

Amendment. The “separate but equal’’ doctr1n y the Fourteenth

Ferguson 163 US 537, 41 L ed 256 16 t e l 1 1 in Pless-V v-

transportation facilities, under which emnliv nf 't ln\olvmS quality in

b> Piouding Negroes and whites substantinflv f tie.at™ent ,13 accorded

acihties, was held to have no place in the f iff eclua ’ tnough separate,

In view of the complex nroble^ ? ° f public education,

decrees, the cases were restored to the d o S t f ^ th® formuIation of the

6 ao^ et -oi- argument by the parties.

SL EJECT OF ANNOTATION

Beginning on page SS2

IHease :Retuf n To

LIBRARY 93 L ed S73

(

i

EEADXOTES

Classified to U.S. Supreme Court Digest, Annotated

247 us SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Oct. Term,

Supreme Court of the X'nited States § 70 —

consolidated opinikm — racial segrega

tion.

1. Even though cases involving the va

lidity of racial segregation laws are prem

ised on different facts and different legal

conditions, the common legal question jus

tifies their consideration together in a con

solidated opinion.

Constitutional Law § 17 — Fourteenth

Amendment — construction — con

temporary history.

2. The legislative history as to the adop

tion of the Fourteenth Amendment by

Congress and its ratification by the states,

the then existing practices in racial seg

regation, and the views of proponents and

opponents of the Amendment, although

casting some light, are not sufficient to re

solve the question whether laws requiring

or permitting segregation according to

race in public schools violate the equal

protection clause of the Amendment.

[See annotation appended, hereto, and

annotation reference 1.]

Constitutional Law § 9 ; Courts § 775 —

construction of Constitution — prece

dents — new conditions.

3. In determining whether segregation

in public schools deprives Negro students

of the equal protection of laws guaranteed

by the Fourteenth Amendment, the court

must consider public education in the light

of its full development and its present

place in American life throughout the na

tion; the clock cannot be turned back to

the time when the Amendment was adopt

ed (1S6S) nor to the time when the Su

preme Court announced the “ separate but

equal” doctrine (1896), under which equal

ity of treatment is accorded by providing

Negroes and whites substantially equal,

though separate, facilities.

[See annotation appended hereto.]

Schools § 1 — equal opportunities.

4. Opportunity of education, where the

state has undertaken to provide it, must be

made available to all on equal terms.

[Sec annotation references 2, 3.]

Civil Rights § 6 — schools — racial segre

gation.

5. The equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the

states from maintaining racially segre

gated public schools, even though the phys

ical facilities and other tangible factors,

such as curricula and qualifications and

salaries of teachers, may be equal.

[See annotation appended hereto, and

annotation references 2-5.] -

Civil Rights § 6 — schools —- separate but

equal.

6. The “ separate but equal” doctrine an

nounced in Plessy v. Ferguson, 162 US 537,

41 L ed 256, 16 S Ct 1138, under which

equality of treatment is accorded by pro

viding Negroes and whites substantially

equal, though separate, facilities, has no

place in the field of public education.

[See annotation appended hereto, and

annotation references 2, 3, 5.]

[Nos. 1, 2, 4, and 10.]

Argued December 8-11, 1952. Restored to the docket for re

argument June 8, 1953. Reargued December 7-9, 1953. Decided

May 17, 1954.

APPEAL by plaintiffs from a judgment of the United States District

Court for the District of Kansas denying an injunction against enforce-

ANNOTATION REFERENCES

1. Resort to details of constitutional

convention, committee reports, rec

ords, etc., as aid in construction of

Constitution, 70 AL<R 5.

2. Constitutional equality of school

privileges as civil right, 44 L ed 262.

3. Equivalence of educational facil

ities extended by public school system

to members of white and members of

colored race, 103 ALR 713.

9S L ed 874

4. Compare 134 ALR 1276 on sepa

ration of pupils in recreational or so

cial activities because of race, color,

or religion.

5. Separate school for colored chil

dren as common or public school with

in contemplation of constitutional or

statutory provision, 113 ALR 713.

\I

1953. BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA 347 trs

(NcT i f ^ o 113113 Statl'te permittin° racial segregation in public schools

r ^ PrEA f^ p,f mtl^ s from a judgment of the United States District

Ccurt fox the Eastern District of South Carolina which denied an injunc-

2) A1 1ShmS segregatl0n in the public schools of South Carolina (No

ConrPtPfn^H1.b F Plf intifS - f/ ^ a judgment of the United States District

enfnrrfm p^ Eastern District of Virginia denying an injunction against

enforcement of provisions in the Virginia Constitution and statutes re

quiring racial segregation in public schools (No. 4 ) . Also

™ WRI T °£ Ce.rti°rari to review a judgment of the Supreme Court

of Delaware affirming a judgment of the Court of Chancery which en-

schnnt ftate ^ icia ls from refusing Negro children admittance to the

schools for whites (No. 10).

Cases restored to docket for argument as to formulation of decrees

i n o r same cases below, 98 F Supp 797 (No. 1) ; 103 F Supp 920 (No 2) •

i°2d 86!UP(No l o r 0' « ': - Del - 81 A2d 137' ~ ™ Ch 87

Robert L. Carter, of New York City,

argued the cause on the original argu

ment and reargument for appellants in

No. 1.

Thurgood Marshall, of New York

City, and Spottswood W. Robinson III,

of Richmond, Virginia, argued the

cause on the original argument and

reargument for appellants in Nos 2

and 4.

' -r-v E °u*s E. Redding, of Wilmington,

Delaware, argued the cause on the

original argument, and Jack Green

berg, of New York City, argued the

cause on the original argument and

reargument, for respondents in No. 10.

Thurgood Marshall, of New York

City, argued the cause on reargument

for respondents in No. 10.

Robert L. Carter, Thurgood Mar

shall, Jack Greenberg, Constance Ba

ker Motley, all of New York City,

Spottswood W. Robinson III and Oliver

W. Hill, both of Richmond, Virginia,

Louis L. Redding, of Wilmington, Del

aware, George E. C. Hayes and Frank

D; Reeves, both of Washington, D. C.,

William R. Ming, Jr., of Chicago, Il

linois, James M. Nabrit, Jr., of Hous

ton, Texas, Charles S. Scott, of Topeka,

Kansas, and Harold R. Boulware, of

Columbia, South Carolina, were on the

brief for appellants in Nos. 1, 2, and

4, and respondent in No. 10.

George M. Johnson, of Sacramento,

California, was on the brief for appel

lants in Nos. 1, 2, and 4.

Loren Miller, of Los Angeles, Cali-

fornia, was on the brief for appellants

in Nos. 2 and 4.

Arthur D. Shores, of Birmingham,

Alabama, and A. T. Walden, of Atlan

ta, Georgia, were on the statement as

to jurisdiction and a brief opposing a

motion to dismiss or affirm in No. 2.

Paul E. Wilson, Assistant Attorney

General of Kansas, argued the cause

on the original argument and reargu

ment, and, with Harold R. Fatzer, At

torney General of Kansas, filed a brief

for appellees in No. 1.

John W. Davis, of New York City,

aad ,T: Justin Moore, of Richmond,

Virginia, argued the cause on the orig

inal argument and reargument, for ap

pellees in Nos. 2 and 4.

T. C. Callison, Attorney General of

South Carolina, Robert McC. Figg, Jr.,

of Charleston, South Carolina, S*. e !

Rogers, of Summerton, South Caro-

Iina, and William R. Meagher and

Taggart Whipple, both of New York

City, were on the briefs for appellees

in No. 2.

J. Lindsay Almond, Jr., Attorney

General of Virginia, argued the cause

on the original argument, and, with

Henry T. Wickham, T. Justin Moore

Archibald G. Robertson, .John W

Riely, and T. Justin Moore, Jr, all of

Richmond. Virginia, filed a brief for

appellees in No. 4,

93 L ed 375

347 V S SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Oct. Term,

H. Albert Young.-Attorney General

of Delaware argued the cause on the

original argument and reargument,

and, with Louis J. Finger, of Wilming

ton, Delaware, filed a 'brief for pe

titioners in No. 10.

Assistant Attorney General J. Lee

Rar.kin, of Washington, D. C., argued

the cause on reargument, and, with

Attorney General Herbert Brownell,

Philip Elman, Leon Ulman, William J.

Lamont, and M. Magdelena Schoch,

also of Washington, D. C-, filed a brief

for the United States, as amicus

curiae, by special leave of Court in

Nos. 2 and 4.

James P. McGranery, former Attor

ney General, and Philip Elman, both

of Washington, D. C., filed a brief for

the United States on the original argu

ment, as amicus curiae.

Shad Polier, of New York City, Will

Maslow, and Joseph B. Robison, filed

a brief for American Jewish Congress,

in No. 1, amici curiae.

Edwin J. Lukas, Arnold Forster, Ar

thur Garfield Hays, Frank E. Karelsen,

and Theodore Leslies, all of New York

City, and Leonard Haas and Saburo

Kido, filed a brief for American Civil

Liberties Union et al.

John Ligtenberg, of Chicago, Il

linois, and Selma M. Borchardt, of

Washington, D. C., filed a brief for

American Federation of Teachers.

Arthur J. Goldberg and Thomas E.

Harris, both of Washington, D. C., for

the Congress of Industrial Organiza

tions, amici curiae.

Phineas Indritz, of Washington, D.

C., filed a brief for American Veterans

Committee, Inc., amici curiae.

Mr. Chief Justice Warren deliv

ered the opinion of the Court.

These cases come to us from the

States of Kansas, South Carolina,

Virginia, and Delaware. They are

premised on different facts and dif

ferent local conditions,

Headnote i but a common legal

question justifies their

consideration together in this con

solidated opinion.1

1. In the Kansas case, Brown v. Board

of Education, the plaintiffs are Negro

children of elementary school age residing

in Topeka. They brought this action in

the United States District Court for the

District of Kansas to enjoin enforcement

of a Kansas statute which permits, but

does not require, cities o f more than

15,000 population to maintain separate

school facilities for Negro and white

students. Kan Gen Stat § 72-1724 (1949).

Pursuant to that authority, the Topeka

Board of Education elected to establish

segregated elementary schools. Other

public schools in the community, however,

are operated on a nonsegregated basis.

The three-judge District Court, convened

under 28 USC §§ 2281 and 2284, found

that segregation in public education has a

detrimental effect upon Negro children,

but denied relief on the ground that the

Negro and white schools were substantially

equal with respect to buildings, transporta

tion, curricula, and educational qualifica

tions of teachers. 98 F Supp 797. The case

is here on direct appeal under 28 USC

§ 1253.

In the South Carolina case, Briggs v.

Elliott, the plaintiffs are Negro children

oTboth elementary and high school age re

siding in Clarendon County. They brought

this action in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of South

Carolina to enjoin enforcement of provi-

9S L ed S75

sions in the state constitution and statu

tory code which require the segregation of

Negroes and whites in public schools. SC

Const, Art 11, § 7; SC Code § 5377 (1942).

Tiie three-judge District Court, convened

under 28 USC §§ 2281 and 2284, denied

the requested relief. The court found that

the Negro schools were inferior to the

white schools and ordered the defendants

to begin immediately to equalize the facili

ties. But the court sustained the validity

of the contested provisions and denied the

plaintiffs admission to the white schools

during the equalization program. 98 F

Supp 529. This Court vacated the District

Court’s judgment and remanded the case

for the purpose of obtaining the court’s

views on a report filed by the defendants

concerning the progress made in the equal

ization program. 342 US 350, 96 L ed

392, 72 S Ct 327. On remand, the Dis

trict Court found that substantial equality

had been achieved except for buildings and

that the defendants were proceeding to

rectify this inequality as well. 103 F

Supp 920 The case is again here on di

rect appeal under'28 USC § 1253.

In the Virginia case, Davis v. County

School Board, the plaintiffs are Negro

children of high school age residing in

Prince Edward County. They brought

this action in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

to enjoin enforcement of provisions in the

the

ret.

cou

pul

on

i

(1

Ii

i

\

i

i

1

r

ins-

mL

chi

per

rac

to (

pro

Fot

the

cas

cou

on •

doc

Pic

L e

doc

acc

vid

eve

stat

reqt

whi

§14

thrc

28 '

que

sell-

and

fen

cqu

-to ‘

and

phi

line

ity

niet

sell

103

dir

I

Bei

of

res

bro

Co;

of

str.

tio:

sc)

Rt

1953. BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA 347 TTS

487—489

*[437]

*In each of the cases, minors of

the Negro race, through their_ legal

representatives, seek the aid of the

courts in obtaining admission to the

public schools of their community

on a nonsegregated basis. In each

*[4S8]

instance, *they had been denied ad

mission to schools attended by white

children under laws requiring or

permitting segregation according to

race. This segregation was alleged

to deprive the plaintiffs of the equal

protection of the laws under the

Fourteenth Amendment. In each of

the cases other than the Delaware

case, a three-judge federal district

court denied relief to the plaintiffs

on the so-called “ separate but equal”

doctrine announced by this Court in

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537, 41

L ed 256, 16 S Ct 1138. Under that

doctrine, equality of treatment is

accorded when the races are pro

vided substantially equal facilities,

even though these facilities be sepa-

state constitution and statutory code which

require the segregation of Negroes and

whites in public schools. Va Const,

§ 140 p Va Code § 22-221 (1950). The

thi’ee-judge District Court, convened under

• 28 USC §§ 2281 and 2284, denied the re

quested relief. The court found the Negro

school inferior in physical plant, curricula,

and transportation, and ordered the de

fendants forthwith to provide substantially

equal curricula and transportation and

to “proceed with all reasonable diligence

and dispatch to remove” the inequality in

physical plant. But, as in the South Caro

lina case, the court sustained the valid

ity of the contested provisions and de

nied the plaintiffs admission to the white

schools during the equalization px-ogram.

103 F Supp 337. The case is here on

direct appeal under 28 USC § 1253.

In the Delaware case, Gebhart v.

Belton, the plaintiffs are Negro children

of both elementary and high school age

residing in New Castle County. They

brought this action in the Delaware

Court of Chancery to enjoin enforcement

of provisions in the state constitution and

statutory code which require the segrega

tion of Negroes and whites in public

schools. Del Const, Art 10, § 2; Del

Rev Code § 2631 (1935). The Chancellor

gave judgment for the plaintiffs ar.d

ordered their immediate admission to

rate. In the Delaware case, the Su

preme Court of Delaware adhered to

that doctrine, but ordered that the

plaintiffs be admitted to the white

schools because of their superiority

to the Negro schools.

The plaintiffs contend that segre

gated public schools are not “equal”

and cannot be made “equal,” and

that hence they are deprived of the

equal protection of the laws. Be

cause of the obvious importance of

the question presented, the Court

took jurisdiction.2 Argument was

heard in the 1952 Term, and reargu

ment was heard this Term on cer

tain questions propounded by the

Court.3

*[489]

*Reargument was largely devoted

to the circumstances surrounding

the adoption of the Fourteenth

Amendment in 1868. It covered ex

haustively consideration of the

Amendment in Congress, ratification

by the states, then existing practices

schools previously attended only by white

children, on the ground that the Negro

schools were inferior with respect to teach

er training, pupil-teacher ratio, extra

curricular activities, physical plant, and

time and distance involved in travel. —

Del Ch —, 87 A2d 862. The Chancellor

also found that segregation itself results

in an inferior education for Negro chil

dren (see note 10, infra), but did not rest

his decision on that ground. Id. 87 A2d

at 865. The Chancellor’s decree was af

firmed by the Supreme Court of Delaware,

which intimated, however, that the defend

ants might be able to obtain a modification

of the decree after equalization of the

Negro and white schools had been accom

plished. — Del —, 91 A2d 137, 152. The

defendants, contending only that the Dela

ware courts had erred in ordering the

immediate admission of the Negro plain

tiffs to the white schools, applied to this

Court for certiorari. The writ was

granted, 344 US 89L, 97 L ed 689, 73 S Ct

213. The plaintiffs,, who were successful

below, did not submit a cross-petition.

2. 344 US 1, 141, 891, 97 L ed 3, 152,

689, 73 S Ct 1, 124, CIS.

3. 345 US 972, 97 L ed 1383. 73 S Ct

1114. The Attorney Genera! of the United

States participated both Terms as amicus

curiae.

93 L ed S77

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES04 7 u s

CCS-491

in racial segregation, and the views

of proponents and opponents of the

Amendment. This discussion and

our own investigation

Headnote 2 convince us that, al

though these sources

cast some light, it is not enough to

resolve the problem with which w e

are faced. A t best, they are incon

clusive. The most avid propo

nents of the post-War Amendments

undoubtedly intended them to re

move all legal distinctions among

“ all persons born or naturalized in

the United States.” Their oppo

nents, just as certainly, were antag

onistic to both the letter and the

spirit of the Amendments and

wished them to have the most lim

ited effect. What others in Congress

and the state legislatures had m

mind cannot be determined with

any degree of certainty.

An additional reason for the in

conclusive nature of the Amend

ment’s history, with respect to

segregated schools, is the status of

public education at that time.4 In

the South, the movement toward

*[490]

free common schools, supported *by

general taxation, had not yet taken

hold. Education of white children

was largely in the hands of private

groups. Education of Negroes was

almost nonexistent, and practically

Oct. Term,

all of the race were illiterate. _ In

fact, any education of Negroes was

forbidden by law in some states. To

day, in contrast, many Negroes have

achieved outstanding success in the

arts and sciences as well as in the

business and professional world. _ It .

is true that public school education

at the time of the Amendment had

advanced further in the North, but

the effect of the Amendment on

Northern States was generally ig

nored in the congressional debates.

Even in the North, the conditions

of public education did not approxi

mate those existing today. _ The cur

riculum was usually rudimentary;

ungraded schools were common in

rural areas; the school term was but

three months a year in many states;

and compulsory school attendance

■was virtually unknown. As a conse

quence, it is not surprising that

there should be so little in the his

tory of the Fourteenth Amendment'

relating to its intended effect on

public education.

In the first cases in this Court

construing the Fourteenth Amend

ment, decided shortly after its adop

tion, the Court interpreted it as pro

scribing all state-imposed discrim

inations against the Negro race.

*[491]

The doctrine of *“separate but

equal” did not make its appearance

4. For a general study of the develop

ment of public education prior to the

Amendment, see Butts and Cremin, A His

tory of Education in American Culture

(1953), Pts. I, II; Cubberley, Public

Education in the United States (1934 ed),

chs II-XII. School practices current at the

time of the adoption of the Fourteenth

Amendment are described in Butts and

Cremin, supra, at 269-275; Cubberley, su

pra, at 288-339, 408-431; Knight, Public

Education in the South (1922), chs \ III,

IX. See also H Ex Doc No. 315, 41st

Cong, 2d Sess (1871). Although the de

mand for free public schools followed sub

stantially the same pattern in both the

North and the South, the development in

the South did not begin to gain momentum

until about 1850, some twenty years after

that in the North. The reasons for the

somewhat slower development in the South

(e. g., the rural character of the South

98 L ed 878

and the different regional attitudestoward

state assistance) are well explained in

Cubberley, supra, at 40S-423. In the coun

try as a whole, but particularly in the

South, the War virtually stopped all

progress in public education. Id., at 427-

42sr The low status of Negro education

in all sections of the country, both before

and immediately after the W ar, is de

scribed in Beale, A History of Freedom of

Teaching in American Schools (1941). 112-

132, 175-195. Compulsory school attend

ance laws were not generally adopted

until after the ratification of the Four

teenth Amendment, and it was not until

1918 that such laws were in force in all

the states. Cubberley, supra, at 563-

565.

/ 5. Slaughter-House Cases (US) 16 Wall

36, 67-72, 21 L ed 394, 405-407 (1873);

/Strauder v. W’est Virginia, 100 US 303,

307, 308, 25 L ed 6C4-C6C (ItSO):

i

1953.

in th;

Plesp

volvi

tatio

labor

half

have

“ pep;

field

mine

175

197.

US 7

valid

not

case:

*levt

spec

stud

dent

ficat

v. C

59 1

“ It

any

with'

perse

proU

deck

be ti

that

shal

Stat

for

prin

shal

of f

men

con‘.

t.ive

the

fror

dist

lege

in

of

oth-

arc

cor.

c

313

par

L <

6

. Ro'

Mo

ag:

sts

1953. BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA

in this Court until 1896 in the case of

Plessy v. Ferguson (US) supra, in

volving not education but transpor

tation.6 American courts have since

labored with the doctrine for over

half a century. In this Court, there

have been six cases involving the

“ separate but equal’’ doctrine in the

field of public education.7 In Cum-

ming v. County Board of Education,

175 US 52S, 44 L ed 262, 20 S Ct

197, and Gong Lum v. Rice, 275

US 78, 72 L ed 172, 48 S Ct 91, the

validity of the doctrine itself was

not challenged.8 In more recent

cases, all on the graduate school

*[492]

*level, inequality was found in that

specific benefits enjoyed by white

students were denied to Negro stu

dents of the same educational quali

fications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 US 337, 83 L ed 208,

59 S Ct 232; Sipuel v. University

347 trs

431 , 492

of Oklahoma, 332 US 631, 92 L

ed 247, 68 S Ct 299; Sweatt v. Paint

er, 339 US 629, 94 L ed 1114, 70

S Ct 848; McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, 339 US 637, 94 L

ed 1149, 70 S Ct 851. In none of

these_ cases was it necessary to re

examine the doctrine to grant relief

to the Negro plaintiff. And in

Sweatt v. Painter (US) supra, the

Court expressly reserved decision on

the question whether Plessy v. Fer

guson should be held inapplicable to

public education.

. the instant cases, that question

is directly presented. Here, unlike

Sweatt v. Painter, there are findings

below that the Negro and white

schools involved have been equalized,

or are being equalized, with respect

to buildings, curricula, qualifications

and salaries of teachers, and other

“ tangible” factors.9 Our decision,

therefore, cannot turn on merely a

It ordains that no State shall deprive

any person of life, liberty, or property,

without due process of law, or deny to any

person within its jurisdiction the equal

protection of the laws. What is this but

declaring that the law in the States shall

be the same for the black as for the white;

that all persons, whether colored or white,

shall stand equal before the laws of the

States, and, in regard to the colored race,

for whose protection the amendment was

primarily designed, that no discrimination

shall be made against them by law because

of their color? The words of the amend

ment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they

contain a necessary implication of a posi

tive immunity, or right, most valuable to

the colored race,—-the right to exemption

from unfriendly legislation against them

distinctively as colored,—exemption from

jegal discriminations, implying inferiority

in civil society, lessening the security

of their enjoyment of the rights which

others enjoy, and discriminations which

are steps towards reducing them to the

condition of a subject race.”

See also Virginia v. Rives, 100 US

313, 318, 25 L ed 667, 669 (1S80); Ex

parte Virginia, 100 US 339, 344, 343 95

L ed 676, 678, 679 (1SS0).

6. The doctrine apparently originated in

Roberts v. Boston, 5 Cush IDS, 206 (1850,

Mass), upholding school segregation

against attack as being violative of a

state constitutional guarantee of equality.

Segregation in Boston public schools was

eliminated in 1855. Blass Acts 1855, ch

256. But elsewhere in the North segrega

tion in public education has persisted in

some communities until recent years. It

is apparent that such segregation has

long been a nationwide problem, not mere

ly one of sectional concern.

7. See also Berea College v. Kentucky,

211 US 45, 53 L ed 81, 29 S Ct 33 (1908).

8. In the Cumming Case, Negro taxpay

ers sought an injunction requiring the de

fendant school board to discontinue the

operation of a high school for white chil

dren until the board resumed operation of

a high school for Negro children. Sim

ilarly, in the Gong Lum Case, the plaintiff,

a child of Chinese descent, contended only

that state authorities had misapplied the

doctrine by classifying him with Negro

children and requiring him to attend a

NegTO school.

9. In the Kansas case, the court below

found substantial eoualitv as to all such

factors. 98 F Supp 797, 793. In the South

Carolina case, the court below found that

the defendants were proceeding “promptly

and in good faith to comply with the

court's decree.” 103 F Supp 920, 921. In

tne \ irginia case, tne court below noted

that the ^equalization program was al

ready ‘‘afoot and progressing” (103 F

Supp oo7, 341); since then, we have b^n

advised, in the Virginia Attorney General's

brief on reargument, that the program has

93 L ed S79

247 CS 492—4&4 SUPE

comparison of these tangible factors

ir. the Negro and white schools in

volved in each of the cases. We

must look instead to the effect of

segregation itself on public educa

tion.

In approaching this problem, v.-e

cannot turn the clock back to 186S

when the Amendment

Keadnote 3 was adopted, or even to

1896 when Plessy v.

Ferguson was written. We must

consider _ public education in the

light of its full development and its

present place in American life

*[493]

throughout *the Nation. Only in

this way can it be determined if seg

regation in public schools deprives

these plaintiffs of the equal protec

tion of the laws.

Today, education is perhaps the

most important function of state

and local governments. Compulsory

school attendance laws and the great

expenditures for education both

demonstrate our recognition of the

importance of education to our

democratic society. It is required in

the performance of our most basic

public responsibilities, even service

in the armed forces. It is the very

foundation of good citizenship. To

day it is a principal instrument in

awakening the child to cultural

values, in preparing him for later

professional training, and in helping

him to adjyst normally to his en

vironment. In these * days, it is

doubtful that any child

Headnoie 4 may reasonably be ex

pected to succeed in life

if he is denied the opportunity of an

education. Such an opportunity,

where the state has undertaken to

provide it, is a right which must be

made available to all on equal terms.

We come then to the question pre

sented: Does segregation of children

in public schools solely

Headnote 5 on the basis of race, even

though the physical

facilities and'other “ tangible’’_fac-

EjJE COURT OF

now been completed. In the Xlelaware case,

the court below similarly noted that the

9S L ed SSO

tors may be equal, deprive the chil

dren oi tne minority group of equal

educational opportunities? We be

lieve that it does.

In Sweatt v. Painter (US) supra,

in finding that a segregated law

school for Negroes could not provide

them equal educational opportuni-'

ties, this Court relied in large part

on “ those qualities which are in

capable of objective measurement

but which make for greatness in a

law school.” In McLaurin v. Okla

homa State Regents, ‘839 US 637, 94

L ed 1149, 70 S Ct 851, supra, the

Court, in requiring that a Negro ad

mitted to a white graduate school

be treated like all other students,

again resorted to intangible con

siderations: “ . . . his ability to

study, to engage in discussions and

exchange views with other students,

and, in general, to learn his profes-

*[494]

sion.” *Such considerations apply'

with added force to children in grade

and high schools. To separate them

from others of similar age and quali

fications solely because of their race

generates a feeling of inferiority as

to their status in the community

that may affect their hearts and

minds in a way unlikely ever to be

undone. The effect of this separa

tion on their educational opportuni

ties was well stated by a finding in

the Kansas case by a court which

nevertheless felt compelled to rule

against the Negro plaintiffs:

“Segregation of white and colored

children in public schools has a det-

rimental effect upon the colored

children. The impact is greater when

it has the sanction of the law; for

the policy of separating the races is

usually interpreted as denoting the

inferiority of the negro group. A

sense of inferiority affects the moti

vation of a child to learn. Segrega

tion with the sanction of law, there

fore, has a tendency to [retard] the

educational and mental development

of Negro children and to deprive

state’s equalization program was well un

der way. — Del —, 91 A2d 137, 149.

TKt. EXITED STATES Oct. Term,

’ i

1 h 6 r

woe

grm

W

tent

the ■

find;

mod

*in .

this

W

pub!

Head.

here

hold

simfi

tions

reast

plair.

proti

the .

dispc

disci:

10.

Delav

timor.

impo.-

suits

receiv

are s

able t

situat

11.

Discri

ment

ence <

mer

JIakir

Chein.

• forced

Sciem

Chein.

of Se:

Facili

Res :

Costs,

AVelfa

Frazil

(1949

Myrd:

.12.

9S L f

eernir.

Fifth

13.

5.

1953. BROWN v. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKA

them of some of the benefits they

would receive in a racial [ly] inte

grated school system.” 10

Whatever may have been the ex

tent of psychological knowledge at

the time of Plessy v. Ferguson, this

finding is amply supported by

modern authority.11 Any language

*[495]

*in Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to

this finding is rejected.

We conclude that in the field of

public education the doctrine of

“ separate but equal” has

Headnote 6 no place. Separate edu

cational facilities are in

herently unequal. Therefore, we

hold that the plaintiffs and others

similarly situated for whom the ac

tions have been brought are, by

reason of the segregation com

plained of, deprived of the equal

protection of the laws guaranteed by

the Fourteenth Amendment. This

disposition makes unnecessary any

discussion whether such segregation

347 U 3

494-495

also violates the Due Process Clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment.12

Because these are class actions,

because of the wide applicability of

this decision, and because of the

great variety of local conditions, the

formulation of decrees in these cases

presents problems of considerable

complexity. On reargument, the

consideration of appropriate relief

was necessarily subordinated to the

primary question— the constitution

ality of segregation in public educa

tion. We have now announced that

such segregation is a denial of the

equal protection of the laws. In

order that we may have the full

assistance of the parties in formu

lating decrees, the cases will be re

stored to the docket, and the parties

are requested to present further

argument on Questions 4 and 5

previously propounded by the Court

for the reargument this Term.13 The

*[49G]

Attorney General *of the United

10. A similar finding was made in the

Delaware case: “ I conclude from the tes

timony that in our Delaware society, State-

imposed segregation in education itself re

sults in the Negro children, as a class,

receiving educational opportunities which

are substantially inferior to those avail

able to white children otherwise similarly

situated.” — Del Ch —, 87 A2d 8G2, 865.

11. K. B. Clark, Effect of Prejudice and

Discrimination on Personality Develop

ment (Midcentury White House Confer

ence on Children and Youth, 1950); Wit-

mer and Kotinsky, Personality in the

Making (1952), ch VI; Deutscher and

Chein. The Psychological Effects of En

forced Segregation: A Survey of Social

Science Opinion, 26 J Psychol 259 (1948);

Chein, What are the Psychological Effects

of Segregation Under Conditions of Equal

Facilities?, 3 Int J Opinion and Attitude

Res 229 (1949); Brameld, Educational

Costs, in Discrimination and National

Welfare (Maclver, ed, 1949), 44-48;

Frazier, The Negro in the United States

(1049), 674-631. And see generally

Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1944).

.12. See Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 US 497,

93 L'ed 334, 74 S Ct 693, post, p 334, con

cerning the Due Process Clause of the

Fifth Amendment.

13. ‘ ‘4. Assuming it is decided that sag-

56

regation in public’ schools violates the

Fourteenth Amendment

“ (a) would a decree necessarily follow

providing that, within the limits set by

normal geographic school districting,

Negro children should forthwith be ad

mitted to schools of their choice, or

“ (6) may this Court, in the exercise of

its equity powers, permit an effective grad

ual adjustment to be brought about from

existing segregated systems to a system

not based on color distinctions?

“ 5. On the assumption on which ques

tions 4 (a) and (6) are based, and as

suming further that this Court will ex

ercise its equity powers to the end de

scribed in question 4 (6),

“ (a) should this Court formulate de

tailed decrees in these cases;

“ (b) if so, what specific issues should

the decrees reach;

“ (c) should this Court appoint a special ,

master to hear evidence with a view to I

recommending specific terms for such de-J

crees;

“ (d) should this Court remand to the

courts of first instance with directions to

frame decrees in these cases, and if so

what general directions should the decrees

of this Court include and what procedures

should the courts of first instance follow

in arriving at the specific terms, of more

detailed decrees?”

93 L ed SSI

S47 US

426

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

States is again invited to participate.

The Attorneys General o f the states

requiring or permitting, segregation

in public education will also_ be per

mitted to appear as amici curiae

upon request to do so by September

15, 1954, and submission of briefs

by October 1, 1954.14

It is so ordered.

14. See Rule 42, Revised Rules of this

Court (effective July 1, 1954).

ANNOTATION

Race discrimination—Supreme Court cases

[See US Digest, Anno: Civil Rights §§ 1-13.]

[a] Generally.

This annotation supplements the

earlier ones in 94 L ed 1121 and 96 L

ed 1291.1

In the past the law touching upon

race discrimination has been greatly

affected by the “separate but equal”

doctrine, first announced in Plessy v.

Ferguson (1896) 163 US 537, 41 L ed

256, 16 S Ct 1138, by which enforced

separation of the races is validated by,

and its validity is dependent upon, the

equality of the separate facilities.

In a decision which is a landmark

in constitutional law, the United States

Supreme Court, in Brown v. Board

of Education (1954) 347 US 483, 98

L ed 873, 74 S Ct 686, 38 ALR2d 1180,

has held that the “separate but equal”

doctrine has no place in the field of

public education. Although the Su

preme Court has not expressly over

ruled Plessy v. Ferguson (US) supra,

the doubt which might be expected to

exist with regard to the continued ap

plicability of the separate but equal

doctrine in fields other than that of

public education has been considera

bly lessened by the Court’s action in

such fields.*

Moreover, in finding in the Brown

Case that segregation of white and

colored children in public schools has

a detrimental psychological^ effect

upon the colored children, the court

expressly rejected any language in

Plessy v. Ferguson contrary to this

finding. Plessy v. Ferguson, dealing

with segregation in trains, contains

no language concerning segregation

of Negroes in public schools. The

only language in the Plessy Case

which may be fairly said to be “con

trary to this finding” is the following:

“Laws permitting, and even requiring

their separation in places where they

are liable to be brought into contact-

do not necessarily imply the inferiori

ty of either race to the other . . . .

We consider the underlying fallacy

of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in

the assumption that the enforced sep

aration of the two races stamps the

colored race with a badge of inferiori

ty. If this be so, it is not by reason

of anything found in the act, but sole

ly because the colored race chooses to

put that construction upon it.” If this

language is rejected, it must be reject

ed in its totality, and not in its con

ceivable application to public educa

tion only.

The decision in the Brown Case vin

dicates Mr. Justice Harlan’s dissent

in Plessy v. Ferguson, where he said:

“ Our Constitution is color-blind, and

neither knows or tolerates classes

among citizens.”

[b] Right to education.

The equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment prohibits the

1. As to racial discrimination in se

lection of grand or petit jury as pro

hibited by Federal Constitution, see

the United States Supreme Court cases

collected in an annotation in 94 L ed

856, supplemented in 97 L ed 1249.

See also Hernandez v. Texas (1954)

347 US 475, 98 L ed 866, 74 S Ct 667,

wThere it was held that exclusion of

persons of Mexican descent from jury

service amounted to a denial of equal

protection.

2. See [d], infra.

/

states :

regatec

ical fa:

tors, si

tions a

equal.

(1954)

6S6, 38

The

Amend

tion in

trict oi

(1954)

693.

The ]

tends :

in f :

of Coni

1112, 7

Supren

the Suj

2d 162

missio;

versity

substai

forded

ported

case w

Court (

the ligl

ticns t'

In 1

Dist. v

F2d 63

was or

other '

forthw

college

admiss

preme

US 974

In B

(1953,

(DC) :

the Di

judge :

admit

citizen

bined

law co

sity v

a thre

pass, o

Supre:

1112, 7

of the

98 L ed 8S2