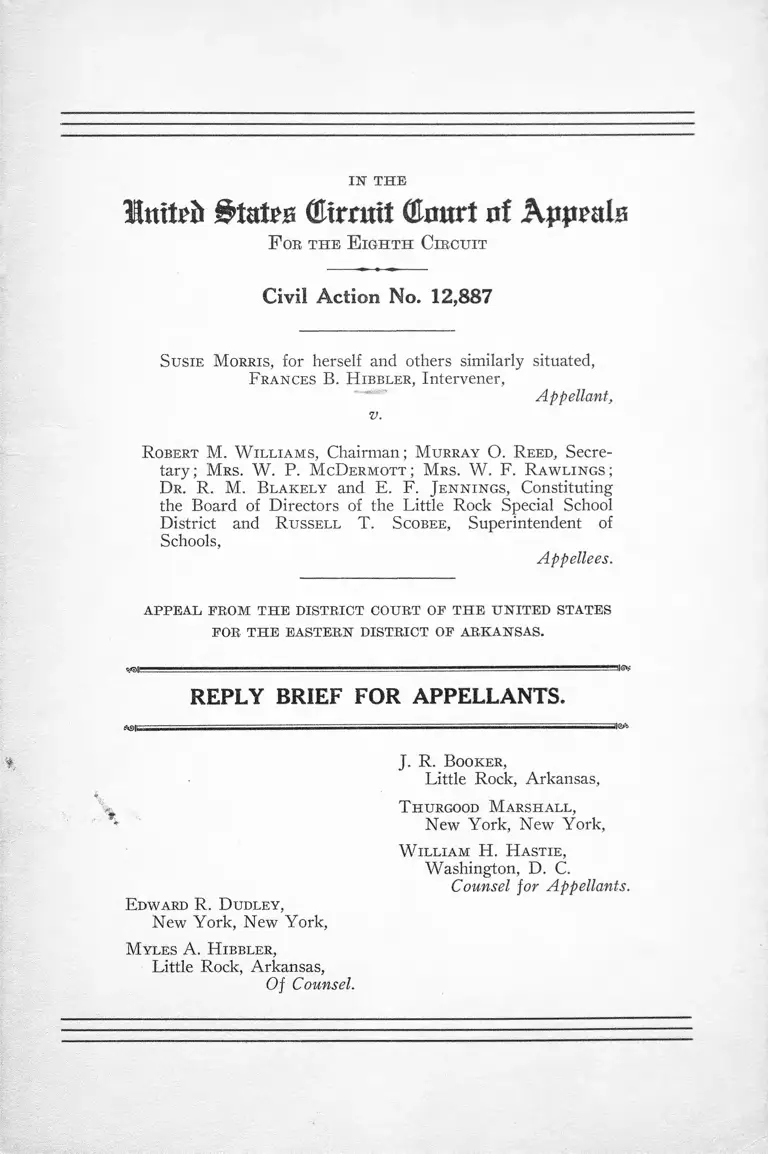

Morris v. Williams Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1945

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Morris v. Williams Reply Brief for Appellants, 1945. d0eba6c6-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2471455a-7993-4d1b-9755-ad2a5024fd46/morris-v-williams-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 14, 2026.

Copied!

IN' THE

lintUb BUtm (ftfmrit (tart of Kppmlz

F oe the E ighth Cibcuit

Civil Action No. 12,887

Susie Morris, for herself and others similarly situated,

Frances B, K ibbler, Intervener,

Appellant,

Robert M. W illiams, Chairman; Murray O. Reed, Secre

tary; Mrs. W . P. McDermott; Mrs. W . F. Rawlings;

Dr. R. M. Blakely and E. F. Jennings, Constituting

the Board of Directors of the Little Rock Special School

District and Russell T. Scobee, Superintendent of

Schools,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e d is t r ic t c o u r t o f t h e u n it e d s t a t e s

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF ARKANSAS.

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS.

♦

Edward R. Dudley,

New York, New York,

Myles A. K ibbler,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

Of Counsel.

J. R. Booker,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

T hurgoqd Marshall,

New York, New York,

W illiam H. Hastie,

Washington, D. C.

Counsel for Appellants.

I N D E X

PAGE

Preliminary Statement _____________________________ 1

I. Proof Required in the Case____________________ 2

II. The District Court Erred in Its Finding That No

Discriminatory Salary Schedule Existed_________ 3

III. The Trial Court Erred in Finding That No Dis

criminatory Policy Was Followed in the Fixing

of Salaries ______________________________ 8

Differences in Salaries____________________ 10

General Salary Adjustment in 1940__________ 11

Bonus Payment _________________________ 12

IV. Appellees’ Tables and Matter De Hors the Record 13

Conclusion _______________________________________ 15

CITATIONS.

Cases:

Mills v. Board of Education, 30 F. Supp. 245 (1940) .. 4

Roles v. School Board of City of Newport News, Civil

Action No. 6 (1943), U. S. District Court for Eastern

District of Virginia, unreported_________________ 4

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649, 88 L. Ed. 987 (1944) 12

Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U. S. 1, 88 L. Ed. 497 (1944).___ 12

11

PAGE

Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. Interstate Commerce

Commission, 219 U. S. 298, 31 S. Ct. 279, 55 L. Ed.

310 (1910) ______________________________ ■________ 14

Thomas v. Hibbitts, 46 F. Supp. 368 (1942)__________ 4

United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Assoc., 166

U. S. 290, 17 S. Ct. 540, 41 L. Ed. 1007 (1896) 14

Yarnell v. Hillsborough Packing Co., 70 F. (2d) 435

(1934)_____________________ _____________________ 14

\

Miscellaneous:

Educational Directory (U. S. Office of Education

[1942])______________________ 10

IN THE

Imtefc States (Eirntit GJmirt at Appeals

F oe the E ighth Circuit

Civil Action No. 12,887

Susie Morris, for herself and others similarly situated,

F rances B. K ibbler, Intervener,

Appellants,

v.

R obert M. W illiams, Chairman; Murray O. R eed, Secre

tary; Mrs. W. P. M cD ermott; Mrs. W. F. R awlings;

D r. R. M. B lakely and E. F. J ennings, Constituting

the Board of Directors of the Little Rock Special School

District and R ussell T. S cobee, Superintendent of

Schools,

Appellees.

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS.

Preliminary Statement.

Much of the material in the brief for appellees is irrele

vant and there is a sharp dispute as to interpretation of

evidence produced at the trial. No effort is made herein to

answer all of the material set forth in brief for appellees.

Most of the argument in the original brief for appellants

remains unanswered. This reply brief is directed solely at

material in appellees’ brief which was not raised in appel

lants’ original brief.

2

I.

Proof Required in the Case.

The appellees deny any visible connection between ap

pellants’ claim of discrimination and those cases involving

exclusion of Negroes from jury service. The analogy here

is a simple one. There is no statute setting up one minimum

salary scale for white teachers in the system and one mini

mum salary scale for colored teachers in the system, nor

do appellees admit that they have adopted such a schedule.

If these were the facts the question as to the constitution

ality of such state action would present no difficulties. In

the jury cases few statutes excluding Negroes from jury

service were enacted subsequent to the passage of the

Fourteenth Amendment and practically all of the cases of

discrimination on this point revolved around the action of

judicial or administrative officials who denied that they

intentionally discriminated against Negroes in the selection

of jurors. The difficulty of proving discrimination became

apparent. It was here that the United States Supreme

Court recognized the difficulty of proof and adopted rules

which created the presumption of exclusion of Negroes from

jury service.

In both instances the Courts were faced with the propo

sition that state officials denied having violated the United

States Constitution. In the jury cases a showing that over

a period of years there were no Negroes accepted for jury

service was considered proof of a policy of discrimination

on the basis of race. In the present case the record clearly

shows that over a period of years all Negro teachers have

received less salary than white teachers of equivalent quali

fications and experience and performing the same duties.

Appellees’ contention that there was no written salary

schedule is no answer to the presumption created that dis

crimination did exist by virtue of all Negro teachers being

paid less salary than white teachers for performing substan

3

tially the same duties. Nor is the answer of Superintendent

Scobee that in his opinion no Negro teachers were worth

more than they were being paid a sufficient rebuttal to the

appellants’ case. It is this type of grouping by race which

is prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment. In fact, it is

no more nor less than an example of arbitrary treatment

designed to classify one group in a category wholly unequal

to another solely on account of race. The Fourteenth

Amendment forbids such discrimination.

II.

The District Court Erred in Its Finding That

No Discriminatory Salary Schedule Existed.

None of the appellees were able to satisfactorily explain

the provision of the minutes of the Board for January 31,

1938, that the “ schedule for new teachers shall be: ele

mentary $810, junior high $910, senior high $945” (R. 576).

Although this provision was adopted prior to the appoint

ment of Superintendent Scobee, and although he denied that

he was directed by anyone to follow the recommendations,

he nevertheless admitted that all of the white teachers ap

pointed by him were paid salaries in excess of the $810

minimum, while at the same time all Negro teachers new

to the system were employed at either $615 or 630.

The testimony by the appellees is that: (1) there is no

written salary schedule, and (2) that all Negro teachers

new to the system are paid a salary below the minimum

salary paid to all white teachers new to the system. It is

also the testimony of each of the appellees that this has been

true as long as they have been in their present positions

as Superintendent or members of the Board of Directors of

the Little Rock Special School District.

The theory of appellees is that there can be no racial

discrimination in the absence of a written salary schedule.

4

In doing this appellees ignore the true basis of the decisions

in the cases cited as well as their own testimony at the hear

ing of this case. In the cases of Mills v. Board of Education/

Thomas v. Hibbitts,1 2 3 and Roles v. School Board3 relief was

granted upon a showing that in the actual payment of sal

aries the Superintendent and School Board fixed salaries

for Negroes at a lower amount than for white teachers. In

the case of Mills v. Board of Education, supra, there was

a statutory minimum salary schedule providing less salary

for Negroes than for white teachers. However, the county

board had a salary schedule higher than the state schedule

and did not follow either of these schedules, but paid all of

its teachers salaries higher than provided in either of the

schedules. Judge Chesnut considered all of the testimony

and reached the conclusion that in the payment of salaries

to teachers the defendants had made a distinction because of

race or color and their action was therefore unconstitutional.

In the Roles case, supra, the salary schedule made no men

tion of race or color. The theory of appellees that dis-

criminiation because of race in the payment of teachers’

salaries can be shown only by the production of a written

salary schedule is fallacious.

In adopting this theory appellees at pages 34-46 of their

brief cite testimony of many witnesses directed to the

proposition that there was no written schedule for white

and colored teachers in this case. Appellees, however, fail

to point out that these same witnesses, although denying

the existence of a written schedule as such do testify that in

fact the policy of the Superintendent was to pay all colored

teachers new to the system the minimum of $615-$630., while

paying all white teachers new to the system the minimum

of $810. Whether or not a written schedule as such was

adopted and physically present is totally unimportant in

view of the actual salaries tendered these teachers.

1 30 F. Supp. 245 (1940).

2 46 F. Supp. 368 (1942).

3 Brief for appellants, pp. 74-77.

5

Appellees on page 32 of their brief in discussing other

cases involving the payment of less salary to Negro teach

ers because of race or color make the following admission:

“ One salary range was applied to white teachers and an

other and lower range was applied to Negro teachers. It

would be difficult to imagine a situation which would furnish

a more clear cut example of racial discrimination than a

case in which such a schedule was used.”

Each of the appellees admitted that in the actual pay

ment of salaries to public school teachers in Little Rock,

Arkansas,

“ one salary range was applied to white teachers,

and another and lower range was applied to Negro

teachers’ ’ :

Mr. Scobee:

“ Q. And isn’t it a fact Negro teachers you have

hired for the elementary schools have all been hired

at the figure of $615.00. A. Practically all. Q.

Practically all? A. Yes. Q. And you remember

yesterday the minutes of the School Board of 1937,

the statement that the minimum salary shall be

$810.00. Do you remember reading that yesterday?

A. I remember reading the minutes. I am not able

to identify the exact date. Q. And is it not true that

since you have been here that all white teachers who

are new to the system in the elementary schools have

been paid not less than $810.00? A. That’s true” (R.

316).

Mrs. McDermott:

“ Q. And isn’t it true, Mrs. McDermott, that since

May, 1938, or rather June, 1938, it has been the policy

to pay white teachers a minimum of $810.00? A. I

think so. Q. And it has been the policy to pay Negro

teachers less than that minimum? A. Yes, sir. Q.

And that has been the policy since 1938? A. I think

so. Q. That is the policy as late as that last Board

meeting? A. I think so” (R. 68-69).

6

Mrs. Rawlings:

“ Q. And during that time on the Board, is it not

true that as to new teachers to the system you paid

white teachers new to the system more than Negro

teachers new to the system! A. No, not in all cases.

It depended on the individual. Q. Well, since 1938,

is it not true that all of the Negro teachers employed

have ranged between $615.00 and $630.00? A. Yes,

sir. Q. And is it not true that during that same time

no white teachers have been employed at less than

$810.00? A. I could not say, but I think you are

correct. Q. Somewhere from $800.00 up, at least?

A. Yes, sir” (R. 84).

Robert M. Willimns:

“ Q. Well, in passing upon the recommendations

of the Superintendent, you have had occasion to

notice the Negro teachers began at the salary, in the

elementary schools, of $615.00 and $630.00, haven’t

you? A. I don’t know as I ever noticed it before

I got here in this courtroom. Q. You have noticed it

since you come into the courtroom? A. Oh, yes.

Q. And you also noticed that the salary of teachers

in the Negro High School began at $630.00? A. Yes,

from the testimony here. Q. You also noticed the

white teachers in the white schools began at a salary

of $810.00? A. Yes. Q. And in the Little Rock

Senior High School at $900? A. I haven’t got that

in mind. Q. That has been the policy of the Board

ever since you have been a member of the Board?

A. I would say so, yes” (R. 359).

Murray O. Reed:

“ Q. Do you know that all the Negro teachers are

paid between $615.00 and $630.00, with one exception

$675.00? Do you remember that? A. All between

$615.00 and $630.00 you say? Q. Yes, sir. A. No, I

didn’t know that. Q. Is it clear in your mind that

Negro teachers new to the system are paid less than

white teachers new to the system? A. I think most

of them are” (R. 99). “ Q. And yet practically all

of the white teachers get over $810.00 to $900.00 a

7

year. How can and how is it that they all fall in

the same category! A. I think I can explain that

this way: the best explanation of that, however, is

the Superintendent of the Schools is experienced in

dealing and working wtih teachers, white teachers

and colored. He finds that we have a certain amount

of money, and the budget is so much, and in his deal

ing with teachers he finds he has to pay a certain

minimum to some white teachers qualified to teach,

a teacher that would suit in the school, and he also

finds that he has to pay around a certain minimum

amount in order to get that teacher, the best he can

do about it is around (fol. 208) $800.00 to $810.00 to

$830.00, whatever it may be he has to pay that in

order to pay that white teacher the minimum amount,

qualified to do that work. Now, in his experience

with colored teachers, he finds he has to pay a cer

tain minimum amount to get a colored teacher quali

fied to do the work. He finds that about $630.00,

whatever it may be” (R. 120).

Dr. R. M. Blakely:

“ Q. Ho they not run in the average between

$615.00 and $630.00 for Negro teachers that have

been appointed since you were on the Board? A.

Yes. Q. And the white teachers run above $810? A.

Run from $810.00 up? Q. Yes, sir. A. Yes. Q. Can

you give the reason for that? A. I thought that was

their qualifications, and we decided to pay that salary.

Q. Did you ever check their qualifications, of any of

these teachers? A. No, that wasn’t one of my func

tions. I would not put myself as being in a position

of knowing the qualifications of a teacher. Q. As

a matter of fact, you don’t know how it happens ? A.

No, except qualifications, that is my understanding

about the salary schedule, the salary— ” (R. 75).

E. F. Jennings:

“ Q. You do not know of any, do you, of any Negro

teacher (fol. 47) new to the system that has been

given as much as the least paid white teacher? A.

No, I don’t ” (R. 27).

8

It is therefore clear that “ one salary range was applied

to white teachers and another and lower range was applied

to Negro teachers” .4

III.

The Trial Court Erred in Finding That No Dis

criminatory Policy W as Followed in the

Fixing of Salaries.

The appellees in their brief at page 43 in referring to

sections of appellants’ original brief quoting- excerpts from

the minutes of the Board of Education from 1926 to 1929,

add that “ It is difficult to see how the Board’s actions at

a time when only one of these defendants had a voice in its

affairs and nine years before the plaintiff was employed can

have much bearing even on policy” . The point is that many

of the teachers employed by the appellees at the time this

case was tried had been employed since 1926 and some

prior thereto. Superintendent Scobee testified that although

there had been a few adjustments since he had been Superin

tendent, in the main salaries of older teachers remained the

same as when he was employed (R. 183). He did not know

what basis was used for the fixing of salaries prior to his

employment. He testified further:

“ Q. I will ask you if it is not a fact if prior to

your coming into the system, the difference was based

solely on the grounds of race the same difference

would be carried on today? A. It would be so in

many cases” (R. 183).

Later in his testimony on being questioned concerning

individual teachers, Mr. Scobee testified:

“ Q. Can you deny that these salaries are set up

on race? A. So far as I am concerned they are not

set up on race. Q. You don’t know how these figures

were arrived at? A. I do not. Q. All you’re doing

4 This quotation appears in appellees’ brief in commenting upon

similar cases in other jurisdictions (appellees’ brief, p. 32).

9

is carrying on as you found it? A. So far as the total

of money spent, I am trying to do that. Q. You made

none or very few changes? A. Very few. Q. You

don’t know any place where you raised one up to the

white level? A. I don’t recall any” (R, 189).

One of the Negro teachers mentioned by the appellees

in the group who were employed at $90 per month in 1926

is Miss Gwendolyn McConico (R. 515). The interesting

thing about Miss McConico is that at the present time, after

fifteen years of service in the Little Rock School System,

she is only receiving $842.25 per year (R. 777). It should

also be pointed out that after sixteen years of service she

is receiving less salary than white teachers new to the

system with no experience whatsoever. Although she re

ceived a fating of “ 3” (R. 777) she receives less salary

than any white teacher in similar circumstances, such as

Dixie D. Speer, who while employed in the white high school

and rated as “ 3” , was paid $900 with no experience in Little

Rock or any place else and Mrs. Guy Irby with an AR de

gree and no experience teaching in the junior high school

as a substitute teacher was paid $900 a year, yet rated

as “ 3” .

The example of Miss McConico is typical of the type of

discrimination being practiced against Negro teachers in

Little Rock, Arkansas, as a result of a combination of

circumstances pointed out in appellants’ original brief.

Appellees in their brief commenting upon the salary

cuts 1932-1933, reached the conclusion that Negro teachers

were not discriminated against because it was provided that

white and colored janitors received the same salary.

Although the salary cuts immediately after 1929 were

made on a percentage basis as pointed out by appellees in

their brief, the discrimination against Negroes is apparent

by the fact that the so-called salary restorations were made

on a basis of race or color. All white teachers were placed

in one group and given increases in salary larger than were

10

given Negro teachers all of whom were placed in another

group. The provisions of the minutes of the appellees on

the question of salary cuts and restorations are fully set

out in appellants’ original brief (pp. 8-11).

Differences in Salaries.

There is a sharp conflict in the testimony as to the teach

ing ability of Susie Morris, original plaintiff in the case.

The person best qualified to judge the teaching ability of

Mrs. Morris was her principal who testified in detail as

to his opinion as to Mrs. Morris’ ability as a teacher (R.

164-165). Mr. Scobee’s appraisal of Mrs. Morris’ ability

was based on but one ten-minute visit to her class (R. 133).

Her other rating was by Mr. Hamilton, who was a part-time

supervisor of the Dunbar High School. It is obvious from

the record that Mr. Lewis is better qualified to rate his

teachers than Mr. Hamilton. In the first place, Mr. Lewis

has several degrees from accredited colleges and many

years of experience as an administrator of both high schools

and colleges (R. 162). Mr. Hamilton, on the other hand,

is a graduate of Wilmington College in Ohio, which is only

accredited by the American Association of Teachers’ Col

leges.5

If there were any doubt as to Mrs. Morris’ ability as a

teacher, it is immediately dispelled by the undisputed testi

mony that during the summer prior to the trial of this case,

she attended the University of Chicago as a graduate

student and one of the subjects involved the use of methods

of teaching English exactly as taught by her in the Little

Rock School System. Her methods and outlines were given

for the purposes of criticism by other students and faculty.

At the conclusion of this course Mrs. Morris attained the

grade of “ A ” (the highest possible grade which could have

been obtained) (R. 506).

5 Educational Directory, published by the United States Office of

Education (1942).

11

Appellees throughout the brief repeatedly emphasize the

statement that a majority of the Negro teachers are gradu

ates of unaccredited colleges. In doing this they ignore the

fact that of the 38 teachers, including the principal in Dun

bar High School 23 have Bachelor degrees from accredited

colleges and 5 have Master degrees from accredited colleges

(R. 653).6 No college appears beside the name of Bernice

Bass, who has a Bachelor degree and her name was not

counted in the figures above.7

General Salary Adjustment in 1940.

In the salary adjustment of 1940 appellees make much

of the fact that in the adjustment of salaries of two white

teachers, Mr. Axtell and Miss Litzke, no accurate basis was

used. Without going through the entire list of salaries,

certain facts should be pointed out. In the first place there

is apparently no evidence of rating being used as a basis

for the adjustment. The only items appearing on the list

with the exception of the salaries are training and experi

ence. With the exception of the isolated case mentioned in

appellees’ brief the adjustment for white teachers goes

along the line of experience and training and the Negro

salary adjustments go along the line of training and ex

perience with the additional factor that despite the factors

of training and experience all of the Negro salaries are

lower in each bracket. For example, the highest salary of

any Negro teacher in the Dunbar High and Junior College,

after the adjustment was $756.75 for a teacher with an AB

degree and 30 years of experience as compared with the

lowest salary of any teacher in the white senior or junior

high schools which was $924.75 for a teacher with one

year’s experience in Little Rock and none elsewhere. As

6 The list of accredited colleges appears in Educational Directory

published by United States Office of Education (1942).

7 In addition there is one teacher with four years, one with three,

one with two and one with two and a half years’ training in accredited

colleges.

12

a matter of fact the so-called salary adjustment shows that

the highest paid Negro teacher received before and after

the adjustment less salary than the lowest paid white

teacher (R. 590-594).

Bonus Payment.

The only defense appellees have to the question of the

discriminatory bonus payments of 1941 and 1942 is that

“ the testimony clearly shows, however, that this feature of

the plan devised by these teachers was not understood by

the board members, who thought that proportionate equality

was being achieved” (appellees’ brief, p. 59). It should be

pointed out that the committee that worked out the plan

was composed solely of white teachers (R. 89) and that

Superintendent Scobee testified he did not even consider the

question of putting some Negro teachers on the committee

(R. 197). The plea of innocence of any deliberate discrim

ination is nullified by the testimony of Superintendent

Scobee, who testified that after the 1941 distribution of the

bonus Negro teachers protested to him against the inequal

ity in the method of distribution, yet, despite this plea the

1942 payment was subsequently made on the same basis as

the 1941 payment (R. 197). Appellees relying upon the

case of Snowden v. Hughes, 321 U. S. 1, take the position

that a scheme prepared by a group of teachers and adopted

by the board “ under a mistake of fact” is not state action

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment. This

argument completely ignores, not only the factual material

in the record, but likewise ignores many Supreme Court

decisions as to state action. There can no longer be any

doubt as to what constitutes “ state action” since the case of

Smith v. Allwright, 321 U. S. 649 (1944).

13

IV.

Appellees’ Tables and Matter De Hors

the Record.

The appellees in their brief set out tables of salaries

purporting to be the salaries of some of the teachers in the

public school system of Little Rock showing changes in the

salaries since the trial of this case. This material de hors

the record is not properly before this Court and should not

be considered. This matter is presented without an oppor

tunity of confrontation of witnesses or cross examination

by appellants. The evil inherent in such a practice is

apparent when we consider a portion of the salaries are

produced without explaining, for example, the reasons why

many of the Negro teachers are out of the system and

without explaining that the reason appellant, Susie Morris,

is no longer employed is because of the fact that ap

pellees refused to renew her contract after the trial of

this case. No explanation is given for the other Negro

teachers who are no longer teaching so that appellees can

now make the statement in their brief that “ tables 3, 4 and

5 are omitted because the only Negroes included are no

longer employed by the District” . Nor does the informa

tion de hors the record presented by appellees show that

Mr. Hamilton is no longer employed as a “ supervisor” but

is now relegated to the position “ Census, Attendance and

Health Officer” .

The substantial increase in the salary of Mrs. Hibbler,

appellant-intervener, and other Negro teachers, according

to the tables in appellees’ brief, merely substantiate the

position taken by appellants that there has been a policy

of discrimination because of race in the fixing of salaries of

teachers in Little Rock.

The issues in this case are not moot. Even if appellees

had produced admissible evidence of a change of circum

stances since the trial of the case, the issues would not be

moot.

14

In the United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Associ

ation, 166 U. S. 290, 308,17 8. Ct. 540, 41 L. Ed. 1007 (1896),

there was an action by the United States to enjoin the

operation of an agreement among certain railroads as in

violation of the Sherman Act. The lower Court dismissed

the complaint and the government appealed. The defen

dants filed a motion in the Supreme Court for dismissal on

the ground that the Association had been dissolved. The

motion was denied by Mr. Justice P eckham in an opinion

for the Supreme Court.

In Southern Pacific Terminal Company v. Interstate

Commerce Commission, 219 U. S. 498; 31 S. Ct. 279, 55 L.

Ed. 310 (1910), the Southern Pacific Terminal brought an

action to enjoin the enforcement of an I. C. C. order. The

order was limited to two years and the time expired while

the case was being appealed. On the question as to whether

or not the ease was moot, Mr. Justice McK enna, speaking

for the U. S. Supreme Court, stated:

“ In the ease at bar the order of the Commission may

to some extent (the exact extent it is unnecessary

to define) be the basis of further proceedings. But

there is a broader consideration. The question in

volved in the orders of the Interstate Commerce

Commission are usually continuing (as are mani

festly those in the case at bar), and these considera

tions ought not to be, as they might be, defeated, by

short-term orders, capable of repetition, yet evading

review, and at one time the government, and at an

other time the carriers, have their rights determined

by the Commission without a chance of redress”

(219 U. S. at p. 515).

In both of the above cases the question arose after trial

and pending appeal. There is, however, another case direct

ly in point on this question.

In Yarnelly. Hillsborough Packing Company, 70 P. (2d)

435 (1934), appellees were two Florida citrus fruit corpora

tions.. Appellants composed the Florida Control Committee

selected pursuant to AAA. Appellants, having been served

15

with notice of the application for a temporary injunction,

on the day before the hill was filed revoked the prorate

orders of which complaint was made. The injunction was

issued. The Circuit Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

held that:

“ # * # As the control committee did not admit the

illegality of the orders they revoked on the eve of the

hearing, nor disclaim an intention to issue similar

orders in the immediate future, the ease is not moot# # * ??

The law in the federal courts on this matter seems clear.

The instant case is even weaker than the Tarnell case

(supra) because in the instant case there is no actual proof

of the discontinuance of the discriminatory policy.

Conclusion.

This case marks an important step in the line of cases

which have had for their purpose the removal of the prac

tice, custom and usage of paying Negro teachers less salary

than white teachers because of their race.

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that the judg

ment of the District Court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

, J. R. B ooker,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

T hurgood M arshall,

New York, New York,

W illiam H. H astie,

Washington, D. C.,

Counsel for Appellants.

E dward R. D udley,

New York, New York,

M yles A. H ibbler,

Little Rock, Arkansas,

Of Counsel.

I

/

-

\

Lawyers Press, I nc., 165 William St., N. Y. C.; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300