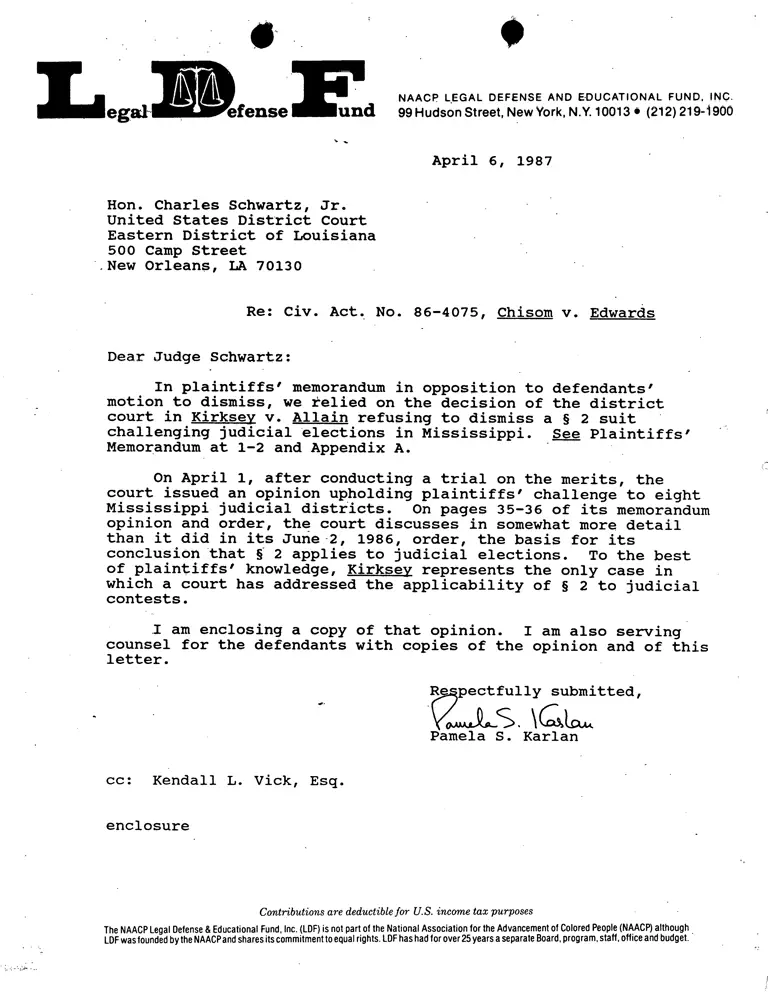

Correspondence from Karlan to Schwartz (Judge); Martin and Kirksey v. Allain Memorandum Opinion and Order; Order

Public Court Documents

April 1, 1987 - May 2, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Correspondence from Karlan to Schwartz (Judge); Martin and Kirksey v. Allain Memorandum Opinion and Order; Order, 1987. f1b74d2b-f211-ef11-9f89-6045bda844fd. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/2483040e-e596-40c9-8260-3a4c22fb109a/correspondence-from-karlan-to-schwartz-judge-martin-and-kirksey-v-allain-memorandum-opinion-and-order-order. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

•

egalZefense und 99 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y. 10013 (212) 219-1900

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

April 6, 1987

Hon. Charles Schwartz, Jr.

United States District Court

Eastern District of Louisiana

500 Camp Street

.New Orleans, LA 70130

Re: Civ. Act. No. 86-4075, Chisom V. Edwards

Dear Judge Schwartz:

In plaintiffs' memorandum in opposition to defendants'

motion to dismiss, we relied on the decision of the district

court in Kirksey V. Allain refusing to dismiss a § 2 suit

challenging judicial elections in Mississippi. See Plaintiffs'

Memorandum at 1-2 and Appendix A.

On April 1, after conducting a trial on the merits, the

court issued an opinion upholding plaintiffs' challenge to eight

Mississippi judicial districts. On pages 35-36 of its memorandum

opinion and order, the court discusses in somewhat more detail

than it did in its June 2, 1986, order, the basis for its

conclusion that § 2 applies to judicial elections. To the best

of plaintiffs' knowledge, Kirksey represents the only case in

which a court has addressed the applicability of § 2 to judicial

contests.

I am enclosing a copy of that opinion. I am also serving

counsel for the defendants with copies of the opinion and of this

letter.

Re pectfully submitted,

1Qta.,

Pamela S. Karlan

cc: Kendall L. Vick, Esq.

enclosure

Contributions are deductible for U.S. income tax purposes

The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc. (LDF) is not part of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) although

LDF was founded by the NAACP and shares its commitment to equal rights. LDF has had for over 25 years a separate Board, program, staff, office and budget.

• ..

•

D1STRiCT OF Mia)111•101

) FILED

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT C

SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSI

JACKSON DIVISION

FLOYDIST JAMES MARTIN, t AL.

URT

iztsIAP 0 1987

ama4a A. PIERCE, CLERK

BY

Purr

PLAINTIFFS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. J84-0708(B)

WILLIAM A. ALLAIN, GOVERNOR

OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.

(CONSOLIDATED WITH)

HENRY KIRKSEY, ET AL, ON BEHALF

OF THEMSELVES AND ALL OTHERS

SIMILARLY SITUATED,

DEFENDANTS

PLAINTIFFS

VS. CIVIL ACTION NO. J85-0960(B)

WILLIAM A. ALLAIN, GOVERNOR

OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL. DEFENDANTS

MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER

Invoking the court's federal question and civil rights sub-

ject matter jurisdiction, the named Martin and Kirksey plain-

tiffs, black citizens and regiStered voters of the State of

Mississippi, bring these two consolidated voting rights actions

individually and on behalf of two Federal Rules of Civil Proce-

dure 23(b)(2) plaintiff classes previously defined by the court

in its order of March 8, 1985, in Martin as "all present and

future black citizens and black qualified electors of Hinds

County and Yazoo County, Mississippi" and in its order of Janu-

ary 23, 1986, in Kirksey as "all present and future black citi-

zens and black qualified electors of the State of Mississippi."

They challenge the at-large, numbered post election methods used

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

to elect the county judges by separate places in Harrison, Hinds,

and Jackson Counties, Mississippi, the multi-member districts

used to elect the chancellors from separate places in all Missis-

sippi Chancery Court Districts and the multi-member districts

used to elect the circuit judges from separate places in all

Mississippi Circuit Court Districts. Although the plaintiffs

also challenge the district lines themselves for the chancery and

circuit court districts in their First Amended Complaint, they

presented no proof on this issue and did not address it in final

arguments.

The plaintiffs allege that the challenged statutes violate

their rights secured by Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, as amended in 1982, 42 U.S.C. § 1973, the

Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Consti-

tution, and 42 U.S.C. § 1983, because they have not been pre-

cleared as allegedly required by Section 5, because they are

allegedly adopted and are allegedly being maintained for the

racially discriminatory purpose of diluting, minimizing, and

cancelling out black voting strength, and because they allegedly

result in a denial or abridgement of the right of plaintiffs and

other black citizens to vote on account of race or color because

black citizens allegedly have less opportunity than white citi-

zens to participate in the political process and to elect repre-

sentatives of their choice.

2

NO 72A

Rev. 8/82)

S

The plaintiffs requested the convening of a three-judge

district court to hear and determine their Section 5 claims,

11

declaratory judgments that the three challenged election systems

violated plaintiffs' rights under the previously mentioned fed-

eral statutes and constitutional provisions, preliminary and

permanent injunctive relief enjoining the defendants from holding

any further primary or general elections under the challenged

statutes, injunctive relief ordering into effect plans for the

election of judges from single-member districts which do not

dilute black voting strength and which remedy the violations

alleged by the plaintiffs, a court-ordered award of court costs,

litigation expenses, and reasonable attorneys' fees pursuant to

42 U.S.C. §§19731(e) & 1988, and such other relief as may be just

and equitable.

By Order filed on April 3, 1986, the three-judge district

court previously convened in the Kirksey aCtion pursuant to Sec-

tion 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as amended, 42 U.S.C.

§1973c, determined that Section 5 applied to the election of

state court judges and enjoined the defendants from implementing

a number of Mississippi statutes involving the circuit, chancery,

and county court sys-tems unless and until they were precleared

under Section 5. Kirksey v. Allain, 635 F. Supp. 347 (S.D.Miss.

1986)(three-judge court). By letter dated July 1, 1986, the

U. S. Attorney General, through his designated representative,

precleared a number of those statutes. However, the Attorney

General did interpose a Section 5 objection to the utilization of

3

AO 72A •

(Rev. 8/82) -

the post feature for the election of judges in certain judicial

districts which became multi-judge for the first time after No-

vember 1, 1964, the effective date of Section 5 coverage for the

State of Mississippi.

Following an evidentiary hearing on May 27, 1986, and

through an order filed on May 28, 1986, the Court in Kirksey

granted the Kirksey plaintiffs' motion for preliminary injunction

and preliminarily enjoined the defendants from conducting elec-

tions for the offices of circuit judge in the State of Missis-

sippi, chancery judge in the State of Mississippi, and county

judge in only Harrison, Hinds, and Jackson Counties, Mississippi.

Joined as defendants in these actions are Governor William

A. Allain, Attorney General Edwin Lloyd Pittman and Secretary of

State Dick Molpus in their official capacities and as members of

the State Board of Election Commissioners; the Hinds County Board

of Election Commissioners; the Yazoo County Board of Election

Commissioners; the Hinds County Democratic Party Executive Com-

mittee; the Hinds County Republican Party Executive Committee;

the Yazoo County Democratic Party Executive Committee; and

the Yazoo County Republican Party Executive Committee. By previ-

ous orders of the Court, the Republican and Democratic Parties

and the party executive committees for Hinds and Yazoo Counties

have been relieved of the duties of any further appearances and

participation in this case. The .remaining .defendants have denied

that the plaintiffs are entitled to the relief which they seek.

4

40 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

(Jk I

Following discovery, the consolidation of the Martin and

Kirksey actions pursuant to Rule 42 of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure by Order dated August 22, 1986, a pretrial conference,

and the entry of a Pre-trial Order, these two consolidated ac-

tions were tried before the United States District Judge, without

a jury, from March 9 to March 13, 1987, in Jackson, Mississippi.

Having considered the oral and documentary proof received at

trial, the parties' pre-trial briefs and proposed findings of

fact and conclusions of law, and their final arguments, the Court

makes the following findings of fact and cotclusions of law as

required by Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

and in accordance with the appropriate district-by-district

analysis mandated by the United States Supreme Court in

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S: , n.28, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 2271

n.28, 92 L.Ed.2d 25, 52 n.28 (1986), and the Fifth Circuit's

requirement of detailed findings of fact in cases alleging vote

dilution, Velasquez v. City of Abilene, 725 F.2d 1017, 1020-21

(5th Cir. 1984).

FINDINGS OF FACT

General

1. The named Kirksey plaintiffs are black, adult, resident

citizens and voters of the State of Mississippi, residing in

various counties and judicial districts. By Order filed on Janu-

ary. 23, 1986, the Kirksey action was certified as a plaintiff

class action pursuant to Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 23(a)

5

AO 72A ' • .

(Rev. 8/82)

1

and (b)(2) on behalf of a plaintiff class defined as "all present

and future black citizens and black qualified electors of the

State of Mississippi,"

2. Named Martin plaintiffs are black, adult, resident citi-

zens and electors of Hinds County, Mississippi, and reside in the

Fifth Chancery Court District and the Seventh Circuit Court Dis-

trict. By Order filed on March 8, 1985-, the Martin action was

certified as a plaintiff class action pursuant to Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure 23(a) and (b)(2) on behalf of a plaintiff

class defined as "all present and future black citizens and black

qualified electors of Hinds County and Yazoo County, Missis-

sippi."

3. The Defendants are the Governor of the State of Missis-

sippi and other state officials and official bodies responsible

for conducting elections in the state. All of the defendants are

sued in their official capacities.

. 4. At all relevant times in this action, the defendants

were and have been acting under the color of the statutes, ordi-

nances, regulations, customs, and usages of the State of Missis-

sippi, Hinds County, Mississippi, and Yazoo County, Mississippi.

5. Mississippi has a tiered court system. The Mississippi

Supreme Court is the appellate court of last resort. It is com-

posed of nine justices, three of whom are elected from each of

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

6

•

the three supreme court districts into which the state is di-

vided. Supreme court elections are district elections rather

than statewide elections. Justices determine cases regardless of

origin throughout the state.

6. Trial courts of unlimited jurisdiction are the chancery

courts, which are courts of equity and probate, and circuit

courts, which are courts of law. The state is divided into

twenty chancery and twenty circuit districts. All districts are

drawn according to county lines. There are two single-county

chancery districts; the rest contain two to six counties each.

There are thirty-nine chancery ludoes. Six chancery districts

are single-iudge districts. There is one single-county circuit

district; the rest contain two to seven counties each. There are

forty circuit judges. Six circuit districts are single-judge

districts. In all multi-judge districts, both chancery and cir-

cuit, judges are elected in district-wide elections and to desig-

nated posts. Each judge is required to be a resident of his or

her district. In some districts there are post residency re-

quirements.

7. County courts are trial courts with the amount in con-

troversy limited to $10,000.00. They are optional with the indi-

vidual counties. Nineteen of the eighty-two counties in the

state have county judges. Sixteen have one county judge each.

Hinds County has three county judges and Jackson and Harrison

. .

Counties have two each. In these three counties the county

judges are elected to specific posts by county-wide vote.

7

0 72A

Rev. 8/82)

•

8. The Mississippi constitution provides that each person

eligible to hold the office of circuit judge and chancery judge

must be a practicing lawyer for five years, at least 26 years of

ace, and a citizen of the state for five years. Miss. Const.

Art. 6, §154. County judges must meet the same qualifications as

circuit judges. Miss. Code Ann. §9-9-5.

9. The small claims and misdemeanor courts in Mississippi

are known as Justice Courts. Each county has at least two jus-

tice court justices elected from districts by district vote.

They serve on a county-wide basis regardless of the locale of the

controversy within the county. There is no requirement that jus-

tice court justices be attorneys.

10. This suit involves the chancery and circuit courts

statewide and the county courts of Hinds, Harrison and Jackson

Counties. It does not involve the Mississippi Supreme Court or

the justice courts.

11. The only district officials connected with the justice

system other than judaes are district attorneys who are elected

from each circuit court district. Court administration and case

filings are handled by chancery clerks and circuit clerks in each

county who are elected in each county of the state. Venue and

jurisdiction are determined by statute and in general are tied to

counties.

12. The following proof was made either by stipulation in

the Pre-trial Order or by Exhibits D-44 or P-16. "Black%" refers

to the percentage of black population as a whole. "Black VAP"

8

‘0 72A

Rev. 8/82)

•

refers to bladk voting age population. "s1 of Black Attorneys

Eligible" refers to the percentage of black attorneys eligible to

stand for election as ludge out of the total number of attorneys

residing in the district. Two figures under this column repre-

sent a disagreement between the parties but with one of the fig-

ures being agreed to by each party.

CHANCERY COURT DISTRICTS

District 1

Alcorn

Itawamba

Lee

Monroe

Pontotoc

Prentiss

Tishomingo

Union

District 2

Jasper

Newton

Scott

District 3

DeSoto

Grenada

montgome y

Panola

Tate

Yalobus

Distric

a

4

- Amite

Frankli

Pike

Walthal 1

Total

Population

33,036

20,518

57,061

36,404

20,918

24,025

18,434

21,741

Black % Black VAP

10.4

6.2

20.4

29.7

15.6

10.8

3.7

13.8

9.3

5.8

18.0

25.7

13.8

9.3

3.4

12.1

No. of

% Black Black

Attorneys Elected

Eligible Officials

232,137

17,265

19.967

24,556

62,788

53,930

21,043

13,366

28,164

20,119

13,183

15.8 13.8

49.2

27.2

35.0

43.9

23.8

31.5

2.47 13

36.5 32.3

17.8

41.8

40.9

48.9

38.4

38.2

33.7 30.1 1.53 39

16.3

37.4

35.3

42.9

34.5

32.8

4.4 15

149,805

• 13,369

8,208

36,173

13,761

•-47.6 '

• 37.2 .• 32.6

• 43.3 38.3

41.0 • 35.2

71,511 43.0 37.8 4.91 24

9

0 72A

3ev. 8/82)

District 5

Hinds

District 6

Attala

Carroll

Choctaw

Kemper

Neshoba

Winston

District 7

Bolivar

Coahoma

Leflore

Quitman

Tallahat

Tunica

250,998 45.1 40.2 3.84-3.39 25

19,865 39.1 34.0

9,776 45.3 40.4

8,996 28.1 24.5

10,148 54.3 48.1

23,789 17.9 15.6

19,474 39.2 33.8

92,048 34.9 30.5 0.0-1.42 23

45,965 62.1 54.7

36,918 64.0 58.3

41,525 59.1 54.2

12,636 56.0 49.8

hie 17,157 57.3 50.3

9,652 73.0 67.1

163,853 61.5 55.2 5.32-5.20 110

District 8

Hancock

Harrison

Stone

District 9

13,931 65.6 59.5

2,513 55.6 51.1

7,964 65.7 58.8

34,844 62.0 56.1

51,627 37.4 34.8

n 72,344 55.6 50.1

183,223 52.9 47.8 6.89 58

Humphrey

Issaquen

Sharkey

Sunflowe

Warren

Washing

District

a

24,496 9.9 8.8

157,665 19.3 16.9

9,716 22.6 19.1

191,877 18.3 16.0 1.16 7

10

Forrest

Lamar

Marion

Pearl River

Perry

District 11

Holmes

Leake

Madison

Yazoo

66,018 26.8 23.3

23,821 10.8 9.6

25,708 29.9 25.8

33,795 14.9 13.3

9,864 21.7 19.1

159,206 22.1 19.4 2.89-2.95 16

22,970 71.1 64.8

18,790 34.9 31.0

41,613 55.9 50.3

27,349 51.4 46.1

110,722 54.4 48.7 4.85-5.94 52

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 10

••

District 12

Clarke 16,945

Lauderdale 77,285

94,230

34.8 31.1

31.4 27.3

32.0 27.9

District 13

Covinato 15,927 34.6 29.7

Jeff Dav s 13,846 53.6 48.2

Lawrence 12,518 30.9 27.2

Simpson 23,441 30.7 26.8

Smith 15,077 21.2 17.6

80,809 33.6 29.2

District 14

Chickasaw 17,851 36.0 31.8

Clay 21,082 50.0 45.1

Lowndes 57,304 34.2 29.6

Noxubee 13,212 64.6 59.1

Oktibbeh4 36,018 34.3 28.8

Webster 10,300 19.6 16.8

155,767 38.2 . 33.1

1.63-1.62 8

0.0 15

4.65-4.41 50

District 15

Copiah 26,503 48.4 43.3

Lincoln 30,174 30.0 26.3

56,677 38.6 34.2 2.0 12

District 16

Georae 15,297 9.5 8.1

Greene 9,827 20.1 17.2

Jackson 118,015 18.7 16.3

143,139 17..8 15,5 3.16 13

District 17

Adams 38,071 48.5 44.9

Claiborne 12,279 74.5 72.5

Jeffersdn 9,181 82.0 77.7

Wilkinson 10.021 66.9 63.7

69,552 60.1 56.7 5.05-5.05 73

Districts 18

Benton

Calhoun •

Lafayette

. Marshall

Tippah

8,153

15,664

31,030

29,296

18,739

37.9

25.5

26.4

53.2

15.9

32.9 28.2

31.7

21.5

21.6

49.0

13.7

102,882 5.38-5.34 21

• District 19

Jones 61,912 23.1 20.6

Wayne 19,135 33.5 29.2

• 81,047 25.6 22. I.as lo

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 11

District

Rankin

20

69,427 18.6 17.4 1.75 3

Total

Population

CIRCUIT COURT DISTRICTS

Black % Black VAP

District 1

Alcorn 33,036 10.4 9.3

Itawamba , 20,518 6.2 5.8

Lee 57,061 20.4 18.0

Monroe 36.404 29.7 25.7

Pontotoc 20,918 15.6 13.8

Prentiss 24,025 10.8 9.3

Tishominao 18,434 3.7 3.4

No. of

% Black Black

Attorneys Elected

Eligible Officials

210.396 16.0 14.0 2.71 12

District 2

Hancock 24,496 9.9 8.8

Harrison 157,665 19.3 16.9

Stone 9,716 22.6 19.1

191,877 18.3 16.0 1.16 7

District, 3

Benton 8,153 37.9 31.7

Calhoun 15,664 25.5 21.5

Chickasaw 17,851 36.0 31.8

Lafayettie 31,030 26.4 21.6

Marshall1 29,296 53.2 49.0

Tippah 18,739 15.9 13.7

Union 21,741 13.8 12.1

142,474 30.4 26.1 4.34-4.32 27

Distric 4

Holmes

Humphre s

Leflore

Sunflow r

Washing on

22,970 71.1 64.8

13,931 65.6 59.5

_ 41,525 59.1 54.2

34,844 62.0 56.1

72,344 55.6 50.1

185,614 60.3 54.7 6.97-7.04 76

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 12

District 5

Attala

Carroll

Choctaw

Grenada

Montqome7

Webster

Winston

District 6

Adams

Amite

Franklin

Jefferso.

Wilkinso

District 7

Hinds

Yazoo

District

Leake

Neshoba

Newton

Scott

District

8

9

Claiborn

Issaquen

Sharkey

Warren

a

District 10

Clarke

Kemper

Lauderda

Wayne

District

Bolivar

Coahoma

Quitman

Tunica

le

11

19,865 39.1 34.0

9,776 45.3 40.4

8,996 28.1 24.5

21,043 41.8 37.4

13,366 40.9 35.3

10,300 19.6 16.8

19,474 39.2 33.8

102,820 37.6 32.8 1.11-2.19 26

38,071 48.5 44.9

13,369 47.6 42.3

8,208 37.2 32.6

9,181 82.0 77.7

10,021 66.9 63.7

78,850 53.4 49.1 4.16-5.10 61

250,998 45.1 40.2

27,349 51.4 46.1

278,347 45.8 40.7 3.85-3.49 30

18,790 34.9 31.0

23,789 17.9 15.6

19,967 27.2 23.8

24,556 35.0 31. 5

87,102 28.5 25.3 3.17 8

12,279 74.5 72.5

2,513 55.6 51.1

7,964 65.7 58.8

51,6 27 37.4 34.8

74,383 47.2 44.2 6.73-5.88 48

16,945

10,148

77,285

19,135

123,513

34.8

54.3

31.4

33.5

34.0

31.1

48.1

27.3

29.2

29.7 1.45-1.44 16

45,965 62.1 54.7

36,918 64.0 58.3

12,636 56.0 49.8

9,652 73.0 67.1

105,171 63.1 56.5 3.84-3.70. 91

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 13

District 12

Forrest

Perry

District 13

Covington

Jasper

Simpson

Smith

District 14

Copiah

Lincoln

Pike

Walthall

66,018

9,864

75,882 26.1

26.8 23.3

21.7 19.1

22.8 4.08-4.19 6

15,927 34.6 29.7

17,265 49.2 43.9

23,441 30.7 26.8

15,077 21.2 17.6

71,710 34.0 29.6 0.0 15

26,503

30,174

36,173

13,761

48.4

30.0

43.3

41.0

43.3

26.3

38.3

35.2

35.7 4.04 23 106,611 40.5

District 15

Jeff Davis 13,846 53.6 48.2

Lamar 23,821 10.8 9.6

Lawrence 12,518 30.9 27.2

Marion 25,708 29.9 25.8

Pearl River 0 33,795 14.9 13.3

109,688 24.2 21.3 0.0 20

District 16

Clay

Lowndes

Noxubee

Oktibbeha

21,082 50.0 45.1

57,304 34.2 29.6

13,212 64.6 59.1

36,018 34.3 28.8

127,616 40.0 34.7 5.55-5.21 44

District 17

Desoto 53,930 17.8 16.3

Panola 28,164 48.9 42.9

Tallahatchie 17,157 57.3 50.3

Tate 20,119 38.4 34.5

Yalobusha 13,183 38.2 32.8

132,553 34.7 30.8 0.93 39

District 18

- Jones Co. 61,912 23.1 20.6 1.19 7

District 19

George 15,297 9.5 8.1

Greene 9,827 20.1 17.2

Jackson 118,015 18.7 16.3

143,139 17.8 15.5 3.16 13

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 14

District

Madison

Rankin

Hinds Cou

Harrison

Jackson C

20

41,613 55.9 50.3

69,427 18.6 17.4

111,040 32.6 29.5 4.76 18

nty 250,998 45.1 40.2 3.84-3.39 25

County 157,665 19.28 16.86 1.32 5

ounty 118,015 18.74 16.26 3.49 9

History of Official Discrimination

13. Mississippi has a long history of official discrimina-

tion touching on the right of black citizens to vote and partici-

pate in the democratic process. This history has been judicially

determined by federal courts at all levels. This Court took

judicial notice of these determinations as set forth in the many

cases listed in Exhibit P-128.

14. This history includes the use of such discriminatory

devices as poll taxes, literacy tests, and intimidation of

blacks. The history also includes the frequent use in municipal

elections of at-large elections and majority-white election dis-

tricts which had the effect of precluding black citizens from

election to public office.

15. This history of discrimination has extended to the bar

and consequently to the judiciary. In 1967 the first black stu-

• dent was graduated from the University of Mississippi School of

Law, the only state supported law school and the only accredited

•.law school in the state in.1967. •. •That first graduate was Reuben

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 15

Anderson, now a justice of the Mississippi Supreme Court. Before

1967 there were only a handful of black attorneys in the state.

At present approximately 5% of the enrollment at each of the two

law schools in the state are black students.

16. The first black judge in Mississippi since Reconstruc-

tion was Reuben Anderson who received a gubernatorial appointment

to fill a vacant Hinds County Court seat in 1977. Thereafter Jus-

tice Anderson was appointed by the governor to a 7th Circuit

Court vacancy. Justice Anderson was unopposed in his election to

a full term in that position in 1982. Subsequently in 1985 he

was appointed by the governor to a vacancy on the Mississippi

Supreme Court and in 1986 was elected to a full term in that

position. In 1978 Cleve McDowell was elected County Judge of

Tunica County in an uncontested election. In 1985 Fred Banks was

appointed by the governor to fill the vacancy on the 7th Circuit

Court created by Justice Anderson's appointment to the Missis-

sippi Supreme Court. These are the only three blacks to have

served on the state bench in Mississiopi, other than justice

court judges. There are 111 state court judgeships: nine supreme

court justices, 39 chancery judges, 40 circuit judges and 23

county court judges.

17. The bar of the State of Mississippi is an integrated

bar (meaning that all practicing attorneys must be members).

Membership of the Mississippi State Bar Association is approxi-

mately 5,900. Willie Rose, immediate past president of the

16

1/40 72A•

Rev. 8/82) -

Magnolia Bar Association, an association primarily of black at-

torneys, testified that there are approximately 220 black lawyers

in the state of whom approximately 150 are statutorily qualified

to run for chancery or circuit judge, or 2.5% of all lawyers.

The Population of the state is approximately 35% black.

Racially Polarized Voting

18. The existence of racially polarized voting in Missis-

sippi has been found by numerous courts. ,Exhibit P-128.

19. Both sides called experts on racial bloc voting who had

performed analyses using the recognized ecological regression and

homogeneous precinct methods. Both experts had studied judicial

elections and other elections. These analyses produced essen-

tially the same results and conclusions as to the particular

elections studied. The primary differences in their testimony

resulted from the fact that Dr. Allan Lichtman, who testified for

the plaintiffs, limited his study of judicial elections to the

judicial elections in which there were races pitting blacks

against whites whereas Dr. Harold Stanley, who testified for the

defendants, included in his study all judicial elections since

1978.

20. Of the eight iudicial elections involving black candi-

dates studied by Dr. Lichtman, only one black candidate won. Of

the unsuccessful black candidates, each carried the black vote by

at least 59% (except for one to be explained later) with the

average percentage of black vote for the black candidate being

68%. No black candidate who lost received more than 12% of the

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

17

white vote with the average percentage of the white vote for the

black candidate being 2%. The only black candidate receiving

less than 59% of the black vote was Melvin Jennings who ran for

Chancery Judge in the 5th Chancery Court District in 1982. He

received only 30% of the black vote. Jennings was under federal

indictment at the time of the election and was later convicted.

If the Jennings election figures are omitted, Dr. Lichtman's

analysis shows that on average 75% of black voters and only 1% of

the white voters voted for the unsuccessful black candidates.

See Exhibit P-10.

21. The only successful black judicial candidate in a con-

tested election was Justice Reuben Anderson in the 1986 Demo-

cratic Primary for the Central District Supreme Court seat.

Justice Anderson ran against' Richard Barrett, an avowed segrega-

tionist. Justice Anderson received 85% of the black votes and

58% of the white votes. Dr. Lichtman and Dr. Stanley both at-

tributed Justice Anderson's success to his qualifications and

experience as compared to that of Barrett.

22. Dr. Lichtman also studied the 1984 and 1986 congres-

sional election for the Second Congressional District. This

district is known as the Delta District and comprises basically

the counties extending along the Mississippi River in the western

segment of the state. It has a slight black majority voting age

population. In 1984 Robert Clark, a black state senator running

as a Democrat, challenged white Republican incumbent Webb

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82) 18

6 •

Franklin. In 1986 Mike Espy, a black lawyer running as a Demo-

crat challenged Franklin. Clark narrowly lost in 1984, receiving

95% of the black vote and 7% of the white vote. Espy narrowly

won in 1986 receiving 97% of the black vote and 12% of the white

vote.

23. Dr. Lichtman concluded that there is great polarization

by both black and white voters throughout Mississippi but that

polarization is particularly striking among whites who refuse to

vote for black candidates. Dr. Lichtman characterizes the

Anderson victory over Barrett as an aberration. He testified

that although cross-over white votes elected Espy, the white vote

was greatly polarized with the white candidate receiving 88% of

the white vote.

24. Dr. Stanley studied 57 judicial elections rather than

lust the nine involving blacks against white. His analysis

showed that in 37 of the 57 elections studied a majority of

blacks voting voted for the winning candidate. From this and

from Justice Anderson's victory he concluded that blacks and

whites are not polarized in most judicial elections. He did

concede that there is strong polarization of both races when

elections involve blacks against whites.

25. Several witnesses who have been actively involved with

politics on various levels in various parts of the state corrobo-

rated the conclusion of Dr. Lichtman that great polarization

exists.

19

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

to •

26. The Court finds that racial polarization of voters

exists throughout the State of Mississippi, and specifically in

those certain districts for which relief is granted hereunder,

and that blacks overwhelmingly tend to vote for blacks and whites

almost unanimously vote for whites in most black versus white

elections.

The Use of Unusually Large Election Districts,

Majority Vote Requirements, Anti-Single Shot

Provisions, and Other Voting Practices Which

May Enhance the Opportunity for Discrimination

27. Plaintiffs have argued that the districts for the chan—

cery and circuit courts are unusually large and hinder the oppor-

tunity for blacks to elect candidates of their choice. Although

black candidacies are generally less well financed than their

white counterparts and black candidates must accordingly rely on

door-to-door campaigning rather than the use of paid television

advertisements, Mississippi is still a largely rural state, the

use of television in judicial races is not widespread and the

voters expect personal solicitation. There is valid policy for

the limitation on the number of chancery and circuit court dis-

tricts into which the state is divided. The size of the present

chancery and circuit court districts does not discriminate

against black candidates and therefore black voters.

28. Most chancery and circuit court districts are multi-

judge districts and in some multi-judge districts judicial candi-

dates run for specific posts. State election laws provide that a

20

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

majority vote is required to win party nomination. In the gen-

eral election the winner is determined by the candidate receiving

a plurality of the votes. Because of this many black candidates

have qualified and run as independents rather than as candidates.

of a particular political party. There are no anti-single-shot

voting laws. Although it is obvious that abolition of the major-

ity ,vote requirements and post system without adoption of anti-

single-shot voting laws would make it easier in some situations

for black candidates to be elected, this Court cannot hold that

these provisions as they now exist discriminate against blacks

per se.

Candidate Slating Process

29. There is no candidate slating process in Mississippi.

Socio-Economic Disparities

30. It is clear that throughout the State of Mississippi

substantial socio-economic disparities exist between blacks and

whites. Blacks trail whites in years of education completed, per

capita income and percentage of population falling below the

poverty line (Exhibit P-16). Dr. Chandler Davidson, a sociolo-

gist presented by the plaintiffs, testified that studies show

that persons having a lower socio-economic standing tend to reg-

ister and vote at lesser rates than those who have a higher

standing. He testified that blacks and whites of the same socio-

economic standing tend to register and vote at approximately the

21

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

same rates. Since blacks comprise only 35% of the population of

the state and since a considerably higher percentage of blacks

than whites are of lower socio-economic status, this socio-

economic status of most blacks in Mississippi does hinder the

ability of blacks to participate effectively in the political

process.

Racial Appeals During Political Campaigns

31. With the large registration of and participation of

black voters in Mississippi elections, racial appeals by candi-

dates are much less frequent than in past years. Plaintiffs,

however, presented proof of racial appeals by white candidates in

two recent elections: by Richard -Barrett in his 1986 challenge of

Mississippi Supreme Court Justice Reuben Anderson and by white

Congressman Webb Franklin in his 1986 race against challenger

Mike Espy. The racial appeals by Barrett were overt and con-

tained no subtlety. The racial appeals by Franklin were more

subtle. In both elections the black candidate won with cross-over

white votes.

Extent to Which Blacks Have Been Elected

•to Public Office

32. Since the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and

other civil rights activities of the 1960's, participation by

blacks throughout Mississippi in the electoral process has greatly

increased resulting in over 500 blacks presently holding elected

22

40 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

office in Mississippi (Exhibit D-52). With few exceptions, how-

ever, all of these black officials are elected from black major-

ity, sinale-member election districts. Justice Reuben Anderson

and Congressman Mike Espy are the only two blacks who have been

elected from districts with large geographical areas. Espy's

district has a majority black population while Anderson's dis-

trict has a majority white population. Testimony indicated only

three blacks other than Anderson have

office from

Prosecuting

County; and

white majority districts:

Attorney for Clay County;

an Alderman from Corinth.

been elected to public

Bennie Turner, County

the County Coroner for Clay

Responsiveness

33. Plaintiffs have offered no evidence on the issue of

lack of responsiveness on the part of elected officials, and

particularly the elected

ticularized needs of the

several of the witnesses

judiciary of Mississippi, to the par-

members of the black community. However,

testified that perception of the justice

system among blacks would be improved if there were more black

judges.

Tenuousness of the State Policy

Underlying At-Large Judicial Districts

34. There is valid policy underlying the division of the

state into a limited number of chancery and circuit court dis-

tricts and in having multi-judge districts for court administra-

tion purposes (as opposed to election purposes) in those

districts where caseloads require more than one judge. Although

23

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

plaintiffs argue that the state has no such policy, the creation

by the legislature of such districts is a direct adoption of such

a policy by the state.

35. Although the state has adopted the policy of the post

system of electing judges in multi-member judicial districts

above the lustice court level, it long ago adopted the policy of

single-member electoral districts for justice court judges. The

state also has the policy of judges deciding cases which may

originate outside their election districts. Supreme Court jus-

tices are elected from one of three districts but hear cases

statewide. Justice court judges are elected from districts but

hear cases countywide. Thus, this Court concludes that the policy

of post system elections in multi-judge chancery, circuit and

county court judicial districts •i tenuous.

Legislative Intent to Adopt or Maintain

Judicial Electoral System

36. Plaintiffs introduced evidence in the form of old news-

paper articles (Exhibits P-44, P-45 and P-122) which indicated a

racial motive underlying the adoption of statutes instituting a

system in the early 1900's for electing judges. Before that time

judges had been appointed. Defendants' expert Dr. Westley

Busbee, a professor of Mississippi history, testified, however,

that the reference to the possible election of blacks, if judges

were to be elected, was an opposition tactic used at the time by

supporters of an appointed judiciary. After Reconstruction when

whites were successful in disenfranchising blacks, the state was

24

AO 72A !..

(Rev. 8/82)

largely controlled by the landed aristocracy, known as the Bour-

bons, from the older, wealthier areas of the state which largely

lay along the fertile lands

the state grew, the poorer,

state became more populous.

bordering the Mississippi River. As

hill lands in the eastern part of the

During the early 1900's the progres-

sive or populist movement became popular in the hill areas. The

adoption of judicial elections was but one of the successful

battles won by the progressives against the Bourbons. Thus, the

issue of race was not a reason for the adoption of an elected

judiciary.

37. Dr. Busbee studied the legislative passage of statute's

adding chancery and circuit judges from 1968 through 1983 when

most multi-member judicial districts were created and during

which time there were blacks in the Mississippi Legislature. This

study examined roll-call votes. The Mississippi Legislature keeps

no formal legislative history of statutes. The study indicated

practically no opposition by black senators or representatives to

the adoption of any of the statutes. In 1985 the Legislature

passed Chapter 502 of the Laws of 1985 recodifying all judicial

districts and judgeships. Only two of sixteen black legislators

voted against it. This Court concludes that neither a post sys-

tem of judicial elections in multi-member judicial districts nor

multi-member judicial districts themselves were adopted for or are

maintained with the intention of depriving blacks of the right to

elect judicial candidates of their choice.

25

>0 72A

Rev. 8/82)

Findings as to Specific Districts

38. The findings above are applicable generally to all

chancery, circuit and county court districts in the state. The

plaintiffs in addition presented specific proof as to certain

districts.

39. Of the twenty chancery court districts four have major-

ity black populations, the 7th, the 9th, the 11th and the 17th.

All are multi-judge districts except the 17th. The 17th Chancery

Court District is a single-judge district.

40. Hinds County constitutes the 5th Chancery Court Dis-

trict which has four judges, Rankin County constitutes the 20th

Chancery.Court District which has one judge. These Are the only

one-county chancery court districts.

41. In regard to the 5th, 7th, 9th and 11th Chancery Court

Districts, plaintiffs have proven by a preponderance of the evi-

dence the following: (1) blacks constitute a sufficiently large

and geographically compact group in each district so that sin-

gle-member judicial districts can be designed which would have

substantial black populations and voting age majorities; (2)

blacks are politically cohesive; and (3) the white voters vote

sufficiently as a bloc to enable them usually to defeat black

candidates who oppose white candidates.

42. Other than counties contained within the 7th, 9th, 11th

and 17th Chancery Court Districts, the only counties containing

black majority populations are Kemper in the 6th Chancery Court

District, Jefferson Davis in the 13th Chancery Court District,

26

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

Clay and Noxubee in the 14th Chancery Court District, and

Marshall in the 18th Chancery Court District. Even though these

particular counties have black majority populations, all lie in

districts which have over-all white majority populations. In

none of these districts do blacks constitute a sufficiently large

and geographically compact group so that the district could be

divided into two, single-member sub-districts of equal population

one of which has a substantial black population and voting age

majority. Plaintiffs presented no proof as to the feasibility of

dividing any of these districts into sub-districts. Plaintiffs'

witnesses Kirksey and Turner both admitted that the 14th Chancery

District could not be divided into single-member sub-districts

having equal populations with one of the sub-districts having a

black majority population.

43. Of the twenty circuit court districts three have major-

ity black populations, the 4th, the 6th and the 11th. The 4th

and 11th Circuit Court Districts are multi-judge districts; the

6th is a single-judge district.

44. Jones County constitutes the 18th Circuit Court Dis-

trict which has one judge. The 18th is the only one-county cir-

cuit court district.

45. In regard to the 4th and 11th Circuit Court Districts,

plaintiffs have proven by a preponderance of the evidence the

following: (1) blacks constitute a sufficiently large and geo-

graphically compact croup in each district so that single-member

judicial districts can be designed which have substantial black

27

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

populations and voting age majorities; (2) blacks are politically

cohesive; and (3) the white voters vote sufficiently as a bloc to

enable them usually to defeat black candidates who oppose white

candidates.

46. Other than counties contained within the 4th, 6th and

11th Circuit Court Districts, the only counties containing black

majority populations are Marshall in the 3rd Circuit Court Dis-

trict, Yazoo in the 7th Circuit Court District, Claiborne, Issa-

quena and Sharkey in the 9th Circuit Court District, Kemper in

the 10th Circuit Court District, Jefferson Davis in the 15th

Circuit Court District, Clay and Noxubee in the 16th Circuit

Court District, Tallahatchie in the 17th Court District and

Madison in the 20th Circuit Court District. Even though these

particular counties have black majority populations, all lie in

districts which have over-all white majority populations. In

none of the 3rd, 10th, 15th, 16th, 17th and 20th Circuit Court

Districts do blacks constitute a sufficiently large and geo-

graphically compact group so that the district could be divided

into two, single-member sub-districts of equal population one of

which has a substantial black population and voting age majority.

47. Hinds and Yazoo Counties constitute the 7th Circuit

Court District which has four judges. Even though the 7th Cir-

cuit Court District has an over-all white majority population,

plaintiffs have proven by a preponderance of the evidence the

following: (1) blacks constitute a sufficiently large and geo-

graphically compact group in the district so that at least one

28

\O 72A

Rev. 8/82)

single-member judicial district can be designed whiCh would have

a substantial black population and voting age majority; (2)

blacks are politically cohesive in the district; and (3) the

white voters vote sufficiently as a bloc to enable them usually

to defeat black candidates who oppose white candidates. The

Court makes these findings in spite of the fact that Justice

Reuben Anderson was elected as a circuit judge in this district.

48. Claiborne, Issaguena, Sharkey and Warren Counties con-

stitute the 9th Circuit Court District which has two judges. Even

though Claiborne, Issaguena and Sharkey Counties all have sub-

stantial black population majorities, the district as a whole has

a white population majority because of the larger population of

Warren County and its smaller percentage of black population. Of

the total population in the 9th Circuit Court District of 74,627,

22,756 of its citizens live in Claiborne, Issaguena and Sharkey

Counties and 51,627 live in Warren County. Kirksey testified

that he could design two single-member sub-districts with sub-

stantially equal populations from the 9th Circuit Court District,

but, in order for one of those to have a substantial black popu-

lation with a black majority voting age population, the black ma-

jority district would have to include all of Claiborne, Issaquena

and Sharkey Counties plus almost all of Warren County, leavino as

the second sub-district a portion of the City of Vicksburg. This

design would be greatly distorted, would

the district strongly along rural versus

require that the candidate of preference

29

divide the two judges of

urban lines and would

for the black voters in

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

•

the black majority sub-district run from a large four county

area, a situation to which plaintiffs have objected by presenta-

tion of much evidence to the effect that geographically large

districts hinder black candidates. Thus, the Court finds in

regard to the 9th Circuit Court District that a single-member

district cannot be designed which will give blacks any greater

potential to elect a judicial candidate of their choice than the

system which is now in effect in the District.

49. As in the case of the 14th Chancery Court District

which also includes Clay and Noxubee Counties, plaintiffs' wit-

nesses Kirksey and Turner both admitted that the 16th Circuit

Court District could not be divided into single-member sub-dis-

tricts having equal populations with one of the sub-districts

having a black majority.

50. Madison and Rankin Counties constitute the 20th Circuit

Court District which has two judges. Madison County has a black

majority population equal to 55.9 percent of its 41,613 citizens.

Rankin County has a total population of 69,427 of whom 18.6 per-

cent. are black. Accordingly, blacks do not constitute a suffi-

.ciently large and geographically compact group in the district so

that two single-member sub-districts with substantially equal

populations can be designed one of which would have a substan-

tial black population and voting age majority.

51. Hinds County has a county court with three county

judges. Although Hinds County has a black minority population of

45.1 percent, plaintiffs have proven by a preponderance ,of the

30

72A

,Rev. 8/82)

evidence the following: (1) blacks constitute a sufficiently

large and geographically compact group in Hinds County so that at

least one single-member iudicial district can be designed which

will have a substantial black population and voting age majority;

(2) blacks are politically cohesive; and (3) the white voters

vote sufficiently as a bloc to enable them usually to defeat

black candidates who oppose white candidates.

52. Harrison and Jackson Counties both have county courts

with two judges. They have minority black populations of 19,28

percent and 18.74 percent respectively. Blacks do not constitute

a sufficiently large and geographically compact group in either

county so that a single-member judicial district can be designed

which would have a substantial black population and voting age

majority.

Other Findings

53. The policy of Mississippi in regard to filling judicial

offices, as expressed by legislative adoption of election stat-

utes, includes a majority vote feature as to a part of the proc-

ess. Although the winner of the general election is the

candidate who receives a plurality, to obtain nomination as a

candidate of the Democratic or Republican Party the candidate

must receive a majority of the vote in the party primary. If no

candidate receives a majority in the first primary, a run-off is

held between the two candidates polling the most votes. Inde-

pendents can qualify to run in the general election without par-

ticipating in the party nominating process. Mississippi also has

31

%0 72A

Rev. 8/82)

a policy of requiring

to stand for election

been expressed by the

offered no proof

This Court finds

Section 2 of the

judges in multi-member judicial districts

as to specific posts. This policy has also

legislative passage of statutes. Plaintiffs

or araument attacking either of these policies.

that neither policy is a per se violation of

Voting Rights Act of 1985.

54. If deemed a proper remedy for any Section 2 violations,

the division of any multi-member judicial districts into sub-

districts for election purposes should be done so that the sub-

districts so created contain substantially equal populations.

This finding is not based on any ruling of this Court that the

one-man, one-vote concept applies to judicial elections, which it

does not, but on general principles of equity.

55. Willie Rose testified as to the number of black lawyers

in various counties

office of chancery,

listing by district

5th

7th

who are statutorily qualified to hold the

circuit or county judge. The following is a

and county of those persons.

Statutorily Qualified Black Lawyers

Chancery Court Districts Circuit Court Districts

Hinds

Bolivar

Coahoma

Leflore

Quitman

Tallahatchie

Tunica

52 4th Humphreys

4 Holmes

0 Leflore

Sunflower

Washington

4

0

0

0

8 7th Hinds

Yazoo

0

2

4

2

14

22

52

0

52

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

32

9th Humphreys 0

Issaquena 0

Sharkey 0 11th Bolivar 4

Sunflower 2 Coahoma 0

Warren 8 Quitman 0

Washington 14 Tunica 0

24

11th Holmes 2

Leake 1

Madison 3

Yazoo 0

4

6

The proof showed that of these statutorily qualified black law-

yers a number are engaged in other public activities, such as

being members of the state legislature, from which they would

have to resign in order to be eligible to hold a judgeship.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. This Court has jurisdiction of the parties and subject

matter of the action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343(3) and

(4), and 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973, 1973a(c), 19731(f).

2. The action has been properly certified as two class

actions under Rule 23(a) and (b)(2) of the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure.

3. Plaintiffs challenge the at-large, numbered post elec-

tion method and use of multi-member districts for judicial elec-

tions under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the

Constitution. Multi-member districts and at-large plans are not

per se illegal under the Equal Protection Clause. Whitcomb V.

Chavis, 403 U.S. 124, 142 (1971); Seastrunk v. Burns, 772 F.2d

143, 150 (5th Cir. 1985). Multi-member districts violate the

Fourteenth Amendment only if "conceived or operated as purposeful

33

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

devices to further racial discrimination." Rogers v. Lodge, 458

U.S. 613, 617, 619 (1982); Whitcomb, 403 U.S. at 149. There was

no purposeful discrimination and no intent to discriminate when

the statutes creating, adding to, and maintaining (recodifying)

the multi-member judicial districts and the post system of judi-

cial elections were enacted. Therefore, plaintiffs' Constitu-

tional challenge fails.

4. All portions of Mississippi are covered under Section

4(a) of the Votina Rights Act for which preclearance is required

under Section 5 of the Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973c. Since the filing

of these cases, Defendants have obtained Section 5 preclearance

from the United States Attorney General of all judicial election

statutes challenged by Plaintiffs, except for the post provisions

in the multi-member judicial districts. Contrary to defendants'

argument, Section 5 preclearance does not preclude plaintiffs

from challenging those statutes under Section 2. Although this

point was raised by the parties in Thornburg v. Ginales, 478 U.S.

, 106 S.Ct. 2752, 92 L.Ed.2d 25 (1986), the issue was not dis-

cussed by the United States Supreme Court. This Court accepts as

proper the reasoning of Judge Phillips in Gingles v. Edmisten,

590 F.Supp. 345, 375-76 (E.D.N.C. 1984), aff'd. in part and

rev'd in part sub nom Thornburo v. Ginales, 478 U.S. 106 •

S.Ct. 2752, 92 L.Ed.2d 25 (1986), which held that Section 5 pre-

clearance does not preclude plaintiffs' Section 2 challenge. The

standards by which the United States Attorney General assesses

voting changes under Section 5 are different from those by which

34

XO 72A

Rev. 8/82)

judicial claims under Section 2 are to be assessed by the judici-

ary. 590 F.Supp. at 376, citing S. Rep. 97-417 No. 10, at 68,

138-39. Also, because the standards for Section 5 preclearance

were applied in a non-adversarial administrative proceeding, the

Attorney General's preclearance determination has no issue pre-

clusive effect to this action and private plaintiffs can chal-

lenge a plan or procedure even after Section 5 preclearance.

590 F.Supp. at 376; see also U. S. v. East Baton Rouge Parish

School Board, 594 F.2d 56, 59-60 & n.9 (5th Cir. 1979); Cook v.

Luckett, 575 F.Supp. 485, 491 n.1 (S.D.Miss. 1983).

5. Defendants assert that Section 2 of the Voting Rights

Act does not apply to the election of state court -judges. Defen-

dants base their argument on the inclusion of the word "represen-

tatives" in the language of the statute. Section 2(b), as

amended in 1982, provides that a violation of Sub-section 2(a) is

established if, based on the totality of the circumstances, it is

shown that members of a minority group "have less opportunity

than other members of the electorate to participate in the po-

litical process and to elect representatives of their choice." 42

U.S.C. §1973(b). There.is no legislative history of the Voting .

Rights Act or any racial vote dilution case law which distin-

guishes state judicial elections from any other types of elec-

tions. Judges do not "represent" those who elect them in the

same context as legislators represent their constituents. The

use of the word "representatives" in Section 2 is not restricted

to legislative representatives but denotes anyone selected or

35

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

chosen by popular election from among a field of candidates to

fill an office, including judges. Mississippi has chosen to hold

elections to fill its state court judicial offices; therefore, it

must abide by the Voting Rights Act in conducting its judicial

elections, including Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. Ac-

cordingly, this Court concludes as a matter of law that Section 2

applies to judicial elections ..

The defendants also argue that since the one-person, one-

vote doctrine does not apply to judicial elet-tions, then by anal-

ogy Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act does not apply. This

argument simply is not persuasive.

6. Congress substantially revised Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act in 1982 to make clear that a violation could be proven

by showing a discriminatory result or effect alone without proof

of a discriminatory purpose. Section 2 as amended provides:

(a) No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting or standard, practice, or procedure shall be

imposed or applied by any State or political.subdivi-

sion in a manner which results in a denial or abridge-

ment of the right of any citizen of the United States

to vote on account of race or color, or in contraven-

tion of the guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2)

of this title, as provided in subsection (b) of this

section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of this section

is established if, based on the totality of circum-

stances, it is shown that the political processes lead-

ing to nomination or election in the State or political

subdivision are not equally open to participation by

members of a class of citizens protected by subsection

(a) of this section in that its members have less

opportunity than other members of the electorate to

participate in the political process and to elect rep-

resentatives of their choice. The extent to which

members of a protected class have been elected to of-

fice‘in the State or political subdivision is one cir-

cumstance which may be considered: Provided, That

36

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

nothing in this section establishes a right to have

members of a protected class elected in numbers equal

to their proportion in the population.

42 U.S.C. §1973.

7. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. , 106 S.Ct. 2752, 92

L.Ed.2d 25 (1986), is the latest case interpreting Section 2 as

amended in 1982, and the Court accepts that case as applying to

the issues before it. The analysis and ruling of Thornburg must

be applied district by district. "The inquiry into the existence

of vote dilution caused by submergence in a multi-member district

is district-specific." Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 52 n.28.

8. The Senate Judiciary Committee Majority Report accompa-

nying the bill that amended Section 2 in 1982 noted typical fac-

tors or circumstances that might be probative of a Section 2

violation. These factors were also set forth in Thornburg.

1. The extent of any history of official dis-

crimination in the state or political subdivision that

touched the right of the members of the minority group

to register, to vote, or otherwise to participate in

the democratic process;

2. The extent to which voting in the elections of

the state or subdivision is racially polarized;

3. The extent to which the state or political

subdivision has used unusually large election dis-

tricts, majority vote requirements, anti-single-shot

provisions, or other voting practices or procedures

that may enhance the opportunity for discrimination

against the minority group;

4. If there is a candidate slating process,

whether the members of the minority group have been

denied access to that process;

5. The extent to which members of a minority

group in a state or political subdivision bear the

effects of discrimination in such areas as education,

employment and health, which hinder their ability to

participate effectively in the political process;

6. Whether political campaigns have been charac-

terized by overt or subtle racial appeals;

37

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

7. The extent to which members of the minority

group have been elected to public office in the juris-

diction.

Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 38, 42; S.Rep. 28-29. The Senate Report

also mentioned additional factors that in some cases would have

probative value to establish a violation. These are:

A. Whether there is a significant lack of respon-

siveness on the part of elected officials to the

particularized needs of the members of the minority

group.

B. Whether the policy underlying the state or

political subdivision's use of such voting qualifica-

tion, prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice or

procedure is tenuous.

Id. at 38; S.Rep. 28-29.

9. The Senate Report stressed that the list of tentative

factors was not comprehensive or exclusive. As the Court in

Thornburg found, "While the enumerated factors will often be

pertinent to certain types of Section 2 violations, particularly'

to vote dilution claims, other factors may also be relevant and

may be considered." 92 L.Ed.2d at 43; S.Rep. 29-30. The Senate

Committee Report also stated that "there is no requirement that

any particular number of factors be proved,.or that a majority of

them point one way or the other." Id. at 43; S.Rep. 29. The

question whether the political processes are "equally open" de-

pends upon a searching practical evaluation of the "past and

present reality" and on a "functional" view of the political

process. 92 L.Ed.2d at 43; S.Rep. 29-30.

10. Sub-section 2(b) establishes that Section 2 of the

Voting Rights Act has been violated where the "totality of the

circumstances" reveal that "the political processes leading to

38

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

nomination or election. .are not equally

by members of a [protected class] . . .and

less opportunity than other members of the

pate in the political process and to elect

open to participation

that its members have

electorate to partici-

representatives of

their choice." 42 U.S.C. §1973(b); Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 42.

This Court has analyzed the totality of the circumstances pre-

sented in this case and concludes that there is a violation of

Section 2 in the 5th, 7th, 9th, and 11th Chancery Court Dis-

tricts, in the 4th, 7th, and 11th Circuit Court Districts and in

the Hinds County Court District (hereinafter referred to as

"specified districts").

11. The Court finds the proof submitted .by plaintiffs is

sufficient to establish a past history of official discrimination

on a statewide basis including the specified districts. This

discrimination has in the past affected the right of blacks to

register, to vote, or otherwise to participate in the democratic

process.

12. Racial bloc voting is a key element of a vote dilution

or vote discrimination claim under Section 2. Section 2 does not

assume the presence of racial bloc voting; plaintiffs must prove

it. Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 44. Plaintiffs have proved a pat-

tern of racial bloc voting statewide but also specifically in -

certain districts, namely the 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, and 14th Chan-

cery Court Districts, the 4th, 7th, 11th and 16th Circuit Court

Districts, and Hinds County Court District.

39

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

Although the Court in Thornburg recognized that the degree

of racial bloc voting that is cognizable as an element of a Sec-

tion 2 vote dilution claim will vary from district to district

according to a variety of factual circumstances, the Court did

announce general principles for legally significant racial bloc

voting. The purpose of examining the existence of racially po-

larized voting is two-fold: to ascertain whether minority group

members constitute a politically cohesive unit and to determine

whether whites vote sufficiently as a bloc usually to defeat the

minority's preferred candidates. Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 50. In

general, a white bloc vote that normally will defeat the combined

strength of minority support plus white "cross-over" votes rises

to the level of legally significant white bloc voting. Id. A

showing that a significant number of minority group members usu-

ally vote for the same candidates also amounts to racial bloc

voting. Id.

Although it varies from district to district, the evidence

in this case establishes legally significant racial bloc voting.

Based on the evidence presented, this Court concludes that the

State of Mississippi, and especially the specified districts,

experience racially polarized voting which rises to the level of

legal significance under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

13. As to the consideration that any "unusually large elec-

tion districts, majority vote requirements, anti-single-shot

provisions, or other voting practices" may enhance the opportu-

nity for discrimination, this Court has found that the judicial

40

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

districts are not unusually large for their purpose of equalizing

case loads and that there is a valid policy for the limitation on

the number of districts into which the State is divided. The

state does not have anti-single-shot voting laws. The majority

vote requirement is not a strongly probative factor since evi-

dence has shown that many black candidates choose to run as inde-

pendents rather than as party candidates and there is no majority

vote requirement in the general election. Furthermore, majority

vote requirements and a post system are not per se discriminatory

provisions.

14. A "slatina process" is not a relative factor in this

case because no proof was presented of any type of candidate

slating process.

15. The proof established that minority members still bear

the effects of past discrimination. There was substantial proof

of socio-economic disparities between black and white citizens of

Mississippi. This disparity at times hinders the minority's

ability to participate effectively in the political process.

16. Although the proof established one or two extreme cases

of racial appeals in political campaians, the Court did not find

this to be-pervasive throughout all districts. Therefore, this

factor is not probative in this action.

17. Members of the minority croup have been elected to many

public offices as shown in the Table under Findings of Fact Para-

graph 12 and Exhibit P-52, yet none have been elected to the

41

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

judgeships in question here in the twentieth century. Those

blacks who have served as state court judges have done so through

appointment and election as incumbents.

18. There is no .significant lack of responsiveness on the

part of the elected judiciary of Mississippi.

19. This Court has determined that the policy of post sys-

tem elections in multi-judge chancery, circuit and county court

judicial districts is tenuous.

20. Though most of these factors apply to all judicial

districts statewide, the Court examines the totality of the cir-

cumstances to find other factors dealing with the "functional"

view of the political process.

a. Blacks constitute 35% of the population of Missis-

sippi, but constitute only 3.7% of the lawyers in Missis-

sippi: 220 of the 5,900 lawyers in Mississippi are black.

Only approximately 150 of the black lawyers in the state

have the statutory requirements to be elected as a judge,

amounting to 2.5% of all lawyers. This is not a controlling

factor, but a factor the Court has noted.

b. Testimony by witnesses established that plaintiffs

would like to see at least 10% to 30% of the judicial posi-

tions filled by blacks. Section 2(b) clearly provides,

"[N]othino in this section establishes a right to have mem-

bers of a protected class elected in numbers equal to their

proportion in the population." 42 U.S.C. §1973(b). Section

2 does not grant a right to proportional representation; it

42

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

merely permits equality of opportunity for participation.

In many districts there are few statutorily qualified black

lawyers who may seek to run for judicial election.

21. A factor concerning the "functional" view of the po-

litical process which this Court finds most relevant is the com-

position of blacks in the challenged districts. The

concentration of the black population in only a few areas by

which the minority group could constitute a sufficiently large

and geographically compact group in each district so that sin-

ale-member districts can be designed which would have substantial

black populations and voting age majorities is an important fac-

tor to this Court. Thornburg established:

Multimember districts and at-large election schemes,

however, are not per se violative of minority voters'

rights. . . . Minority voters who contend that the

multimember form of districting violates §2 must prove

that the use of a multimember electoral structure oper-

ates to minimize or cancel out their ability to elect

their preferred candidates. See, e.a., S.Rep.16.

While many or all of the factors . listed in the

Senate Report may be relevant to a claim of vote dilu-

tion through submetaence in multimember districts,

unless there is a coniunction of the following circum-

stances, the use of multimember districts generally

will not impede the ability of minority voters to elect

representatives of their choice. . . . These circum-

stances are necessary preconditions for multimember

districts to operate to impair minority voters' ability

to elect representatives of their choice for the fol-

lowing reasons. First, the minority group must be able

to demonstrate that it is sufficiently large and geo-

graphically compact.to constitute a majority in a sin-

gle-member district. If it is not, as would be the

case in a substantially integrated district, the multi-

member form of the district cannot be responsible for

minority voters' inability to elect its candidates. . .

Second, the minority group must be able to show that

it is politically cohesive. If the minority group is

not politically cohesive, it cannot be said that the

selection of a multimember electoral structure thwarts

distinctive minority group interests. . . . Third, the

43

AO 72A

(Rev. 8/82)

I

minority must be able to demonstrate that the white

majority votes sufficiently as a bloc to enable it - in

the absence of special circumstances, such as the mi-

nority candidate running unopposed - usually to defeat

the minority's preferred candidate.

Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 45-47 (citations omitted) (emphasis

added).

Although evidence has established that throughout the state

the minority group is politieally cohesive and the white majority

votes sufficiently as a bloc to usually defeat the minority's

preferred candidate, only in a few districts have the plaintiffs

established that the minority group is sufficiently large and

geographically compact in the district to constitute a majority

in a single-member district. Many factors enumerated in the

Senate Judiciary Committee Report are present in all districts,

yet only in the 5th, 7th, 9th and 11th Chancery Court Districts,

in the 4th, 7th, and 11th Circuit Court Districts, and in Hinds

County Court District, are these factors present in conjunction

with the circumstances of a sufficiently large and geographically

compact minority aroup,political cohesiveness of the minority

group, and a white majority which votes as a block to defeat the

minority's preferred candidate. See Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at

46-47. In these specified districts only have the plaintiffs

established by a preponderance of the evidence a violation of

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by which blacks have "less op-

portunity than other members of the electorate to participate in

the political process and to elect representatives of their

44

\O 72A

:Rev. 8/82)

•

choice." In none of the remaining districts do blacks consti-

tute a sufficiently large and geographically compact group so

that the district could be divided into single-member sub-

districts of substantially equal population one of which would

have a substantial black population and black voting age major-

ity. In those remaining districts the plaintiffs have failed to

prove by a preponderance of the evidence that multi-member dis-

tricts and at-large election schemes violate their rights under

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

22. Plaintiffs have argued in regard to those districts in

which black majority single-member sub-districts cannot be drawn

that this Court should design single-member districts to raise

the black voter percentage by concentrating blacks as much as

possible in order to better "influence" the outcome of the elec-

tions. The Supreme Court in Thornburg has announced:

The reason that a minority group making such a

challenge [a Section 2 challenge against the multi-

member form of the district] must show, as a threshold

matter, that it is sufficiently large and geographi-

cally compact to constitute a majority in a single-

member district is this: Unless minority voters possess

the potential to elect representatives in the absence

of the challenged structure or practice, they cannot

claim to have been injured by that structure or prac-

tice.

Thornburg, 92 L.Ed.2d at 46 n.17. The Plaintiffs have presented