Walker v. City of Birmingham Objections to Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Walker v. City of Birmingham Objections to Motion for Leave to File Brief Amicus Curiae, 1966. e119b153-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/24c8e705-d9e1-4f02-aee0-28a47e662d9d/walker-v-city-of-birmingham-objections-to-motion-for-leave-to-file-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

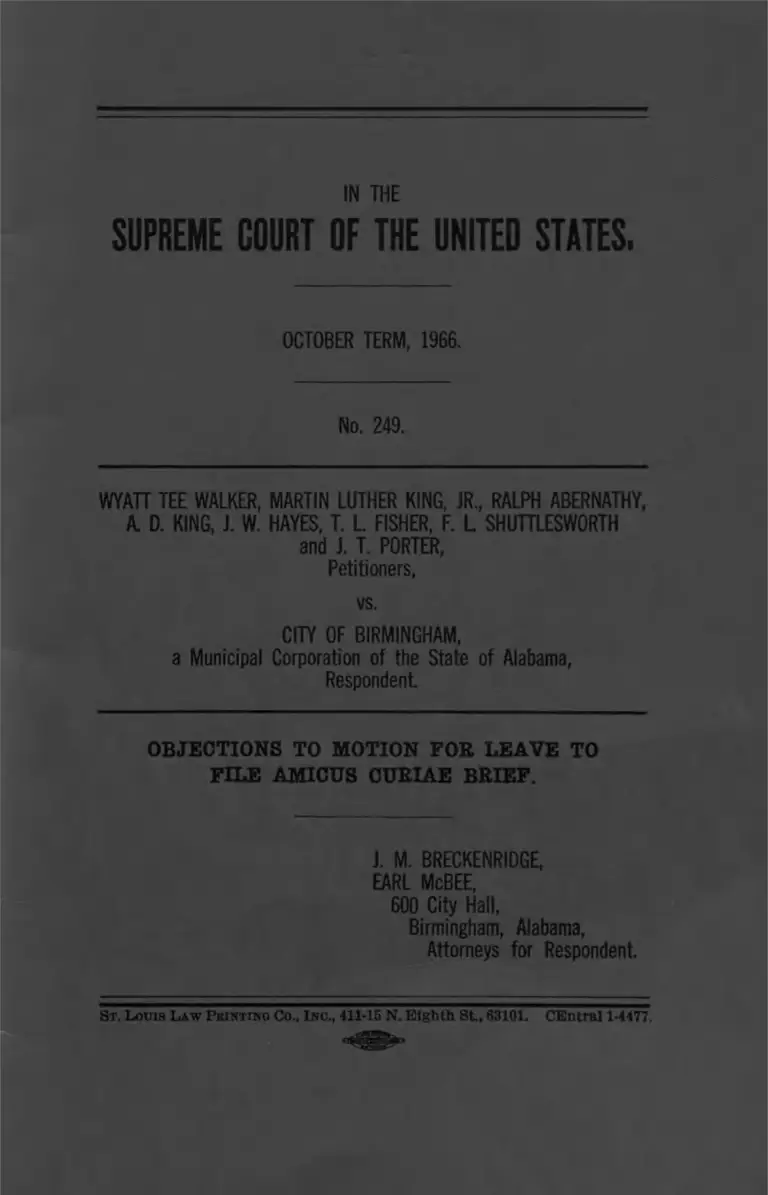

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TERM , 1966.

No. 249.

WYATT T E E WALKER, MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR ., RALPH ABERNATHY,

A. D. KING, J. W. HAYES, T. L . FISHER, F. L SHUTTLESWORTH

and J. T. PORTER,

Petitioners,

us.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

a Municipal Corporation of the State of Alabama,

Respondent

OBJECTIONS TO MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF.

J. M. BRECKENRIDGE,

EARL McBEE,

600 City Hall,

Birmingham, Alabama,

Attorneys for Respondent.

St . L ouis La w P rinting Co., Inc., 411-15 N. Eighth St., 63101. CEntral 1-4477.

AUTHORITIES CITED.

Pages

Cases.

Alabama Cartage Co. v. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen, etc. (1948),

250 Ala. 372, 34 So. 2d 576 ......................................... 6

Alabama State Federation of Labor v. McAdory

(1944), 246 Ala. 14, 18 So. 2d 8 1 0 .............................. 6

Hardie-Tynes Mfg. Co. v. Cruse (1914), 189 Ala. 66,

66 So. 657, 666 ................................................................. 5

Hotel and Restaurant Employees v. Greenwood (1947),

249 Ala. 265, 30 So. 2d 696, cert. den. 322 U. S. 847,

68 S. Ct. 349 ..................................................................... 6

Howat v. Kansas, 258 U. S. 181 ................................. 4,5,7

In Re Green, 369 U. S. 689 ....................................... 4

Shiland et al. v. Retail Clerks, Local 1657 (1953), 259

Ala. 277, 66 So. 2d 146 ............................................. 6

Staub v. Boxley, 355 U. S. 313 ..................................... 4

Sutter v. Amalgamated Assn, of Street, Railway and

Motor Coach Employees of America (Local 1127 of

Shreveport, Louisiana) et al. (1949), 252 Ala. 463,

41 So. 2d 190 ................................................................. 6

United States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U. S. 258.. 4

Statutes.

Acts of Alabama, 1943, page 252 .................................. 5

City of Birmingham Ordinance 63-17, Section 7 . . . . 6

Code of Alabama, 1940, Title 26, Sections 376 et seq... 5

IN TH E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TERM , 1966.

No. 249.

WYATT T E E WALKER, MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR ., RALPH ABERNATHY,

A. D. KING, J. W. HAYES, T. L . FISHER, F. L SHUTTLESWORTH

and J. T. PORTER,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF BIRMINGHAM,

a Municipal Corporation of the State of Alabama,

Respondent.

OBJECTIONS TO MOTION FOR LEAVE TO

FILE AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF.

Respondent, City of Birmingham, declined to consent to

the filing of brief amicus curiae on behalf of the American

Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organi

zations (AFL-CIO). We respectfully object to and oppose

the motion for leave to file such brief.

We cannot fully develop our reasons for objecting to

such motion within the limits of brevity required by Su

preme Court Rule 42, which provides that when a motion

to file brief amicus curiae is made “ a party served with

such motion may seasonably file an objection concisely

stating the reasons for withholding consent” . We under

stand this to mean that only a very skeletonized presen

tation is permissible.

Briefly stated, these reasons include: (I) The delay to

this point in the proceeding in seeking to file a brief

amicus curiae should bar its filing; (II) The opinion and

decision of this Honorable Court is based upon thorough

consideration and careful determination of fundamental

issues concerning respect for our courts and for law and

order, not in a factual situation related to a labor contro

versy, but one involving the right of a municipality to

protect its citizens in the use of its streets and sidewalks

and from mob violence, but was rendered with an aware

ness of the cases involving organized labor, many of which

were cited and discussed by the parties in lengthy briefs

and argument and some by the Court in its opinion; and,

lastly, (III) It poses no serious threat to the legal and

constitutional rights of the organized labor movement, or

any other group, either minority or majority.

I .

Respondent has declined consent to the filing of the

amicus curiae brief at this stage of the case, coming after

most thorough briefing* 1 and lengthy oral argument of the

1 Briefs filed with this Court and referred to in the letter of

respondent declining to consent include:

1. Petitioners’ Brief and Petition for W rit of Certiorari to

the Supreme Court of Alabama, containing 45 pages and

an Appendix of 35 additional pages.

2. Respondent’s Brief in Opposition to Petition for W rit of

Certiorari, containing 37 pages.

3. Brief for the Petitioners on the Merits, containing 81

pages, with a short Appendix of three additional pages.

4. Memorandum Brief for the United States as Amicus

Curiae filed by the Solicitor-General, containing 25 pages.

5. Brief of Respondent in reply to the Petitioners’ Brief and

the Brief of the Solicitor-General, containing 74 pages,

and an Appendix of eleven additional pages.

6. Petitioners’ Reply Brief, containing four pages.

7. Respondent’s Supplemental Brief, containing five pages.

____2 _____

- 3 —

issues involved and careful determination of them by this

Honorable Court. Movant admits they have never before

attempted to file an amicus curiae brief at such a late

stage of the case. While we find nothing in the Supreme

Court Rules either allowing or disallowing such a belated

motion, the intent of Rule 58, imposing severe restrictions

upon the right of a prevailing party to file a brief on

application for rehearing, would logically justify a re

fusal to consider the motion of a stranger to the case to

file a brief after the rendition of the Court’s decision. We

urge this be done.

II.

Movant admits the briefs by petitioners and by the

Solicitor-General for the United States admirably cover

the issues of freedom of speech and freedom of assembly.

These issues are factually related to the denunciation by

petitioners of courts in the South in general, and in par

ticular their open defiance of the injunction by deliber

ately violating it without making any effort whatever to

dissolve or modify it. Such issues are also related to the

right of a municipality to protect petitioners and its citi

zens from the consequences of lawless commandeering of

its streets and sidewalks in a situation involving an un

ruly, violent mob.

Underlying these important issues is the fundamental

question of whether any group, minority or majority, is

entitled to determine for itself what laws and court decrees

it will choose to obey or what laws and court decrees

it will flout and violate. An affirmative answer to this

question may be considered by some as giving open

encouragement to those who would riot, pillage, burn

and murder. Or else it may well be like a seed that may

be nurtured by one with malice in his heart, or even pos

sibly by one who is well-meaning but misguided to grow

— 4 —

into such incidents as those experienced within the past

year or two by Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, New York

and other cities, and more recently by Newark, New

Jersey and surrounding cities.

These were the vitally important issues briefed by the

parties to the case. These were the issues determined by

the Court in its opinion and decision, which we earnestly

urge is eminently correct.

The major premise upon which the request for consent

and the motion for leave to file is based is the unfounded

inference that this Honorable Court was unaware of or

failed to consider in its opinion the labor movement and

the cases and statutes spelling out its legitimate consti

tutional and statutory rights, and the incorrect notion that

in so doing this Honorable Court fashioned an opinion

that may be the vehicle through which the right of labor

to organize may be destroyed and the destruction of its

other constitutional and statutory rights may be facili

tated.

As we shall later comment on in more detail, the Court’s

opinion is largely rested upon Howat v. Kansas, 258 U. S.

181, a labor injunction case. Other labor injunction cases

cited by it include In Re Green, 369 U. S. 689, and United

States v. United Mine Workers, 330 U. S. 258. A score

or more labor cases are cited in one or more of the various

briefs of the parties filed before decision, including the

three last above mentioned and Staub v. Boxley, 355 U. S.

313. Reference to the table of cases shows that three of

the four are cited by Movant.

III.

We do not find in such opinion and decision any threat,

direct or indirect, to the legitimate interests of organ

5

ized labor. Certainly, the right to organize and to law

fully strike and peacefully picket for legal causes are

rights of organized labor that are no longer open to ques

tion. The decisions of this Honorable Court and the

courts of the several states, including the State of Ala

bama, to say nothing of numerous federal and state

statutes, within the last fifty years have firmly developed

and established these rights.

It is interesting to note that the doctrine of Howat v.

Kansas, 258 U. S. 181, a case involving a labor contro

versy, relied upon by the respondent herein and which

is followed by this Honorable Court in its opinion, was

decided some fifty years ago. It did not spell the doom

of organized labor, then in its infancy, as a factor in the

economic life of this country. To the contrary, it has

grown in size and strength and power to the point that

only recently Congress has been called upon by the Presi

dent to enact emergency legislation to protect our country

in its military and other vital interests from the frighten

ing consequences of a nation-wide tieup of our trans

portation system.

Required brevity will not permit development of the

point made in III. However, we do ask indulgence to be

permitted to comment very briefly at least on some of the

relevant Alabama cases typical of those throughout the

Nation showing the development of legal concepts up

holding the right of labor to organize, to strike, and to

peacefully picket. In Hardie-Tynes Mfg. Co. v. Cruse

(1914), 189 Ala. 66, 66 So. 657, 666, the Alabama Supreme

Court recognized the constitutional rights of labor to

organize and to strike, but denied them the right even

peacefully to picket. These rights received legislative

sanction in 1943 when the Bradford Act was enacted.

Acts of Alabama, 1943, page 252; Code of Alabama of

1940, Title 26, Sections 376 et seq. Its constitutionality

was sustained in Alabama State Federation of Labor v.

McAdory (1944), 246 Ala. 14, 18 So. 2d 810.

In Hotel and Restaurant Employees v. Greenwood

(1947), 249 Ala. 265, 30 So. 2d 696, cert den. 322 U. S.

847, 68 S. Ct. 349, the right of employees to organize and

to strike and peacefully picket to obtain a closed shop

contract with the employer was recognized. A later case,

Alabama Cartage Co. v. International Brotherhood of

Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen, etc. (1948), 250

Ala. 372, 34 So. 2d 576, differs in that the latter case in

volved a “ wild-cat” or unlawful strike in violation of

the contract between the Union and the employer.

Two additional Alabama cases are worthy of mention

because they upheld the right to engage in peaceful pick

eting upon the public sidewalks of the City of Birming

ham.2 Sutter v. Amalgamated Assn, of Street, Railway

and Motor Coach Employees of America (Local 1127 of

Shreveport, Louisiana) et al. (1949), 252 Ala. 463, 41 So.

2d 190, dealt with a situation where a bus terminal was

picketed incident to a labor dispute between the Union

employees and Southern Bus Lines, Inc. for a period of

some two years. The other case is Shiland et al. v. Retail

Clerks, Local 1657 (1953), 259 Ala. 277, 66 So. 2d 146.

In the latter case, false allegations in the verified bill

of complaint procured the issuance of an injunction by a

2 Over a period of many years the City of Birmingham has

observed a policy of non-interference with peaceful picketing

in labor disputes. Since 1963 it has by ordinance recognized

the right to use public sidewalks to engage in demonstrating

or picketing, when properly conducted, for any lawful purpose.

In 1963 the City Commission was succeeded by the Mayor-Coun

cil form of government. Within a few weeks after it took office,

the City Council adopted Ordinance 63-17, which in Section 7

thereof provides: “Those who participate in any demonstra

tion on any sidewalk shall be spaced a distance of not less than

ten feet apart; and not more than six persons shall demon

strate at any one time before the same place of business or

public facility.”

— 6 —

— 7 —

member of the Supreme Court of Alabama on March 23rd,

and on May 1st thereafter the Circuit Judge dissolved the

injunction. The Alabama Supreme Court affirmed on ap

peal.3

IV.

In conclusion, we respectfully submit that neither con

stitutional nor statutory rights of labor organizations, nor

the many decisions delineating them, were overlooked by

this Honorable Court in arriving at its decision in this

case. It is unrealistic to criticize this gravely important

and sound decision because of an imagined threat to the

legitimate rights of organized labor. Past experience

shows the groundless nature of such criticism. Moreover,

the opinion is carefully constructed to uphold the dignity

of our courts and respect for honestly rendered injunction

decrees and to engender respect for law and order, recog

nizing the legitimate interest of state and local govern

ments in regulating the use of their streets and public

places in the preservation of law and order for the pro

tection of petitioners as well as the general public. At

the same time, state and local officers are clearly put on

notice that this Honorable Court will not tolerate a con

tempt conviction “ (w)here the injunction was transpar

ently invalid or had only a frivolous pretense to validity.”

Nor will it apply the rule of Howat v. Kansas if, before

disobeying the injunction, it is properly challenged in the

state courts and in the process the challengers are “ (m)et

with delay or frustration of their constitutional claims.”

This safeguard stands as a bulwark to protect not only

the constitutional rights of organized labor but any other

group, minority or majority.

3 One of the writers of this objection was of counsel repre

senting the respective Union in each of the four last above

cited eases and our comments, because of his familiarity with

them, extend slightly beyond what is shown in the printed

opinions cited.

We respectfully request this Honorable Court to deny

the motion for leave to file amicus curiae brief.

Respectfully submitted,

— 8 —

J. M. BRECKENRIDGE,

EARL McBEE,

Attorneys for Respondent.