Barton v. Eichelberger Brief for Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Barton v. Eichelberger Brief for Amici Curiae NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent, 1971. 9214899c-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/24e3f75c-6dfa-4a2f-b987-134b374adaf3/barton-v-eichelberger-brief-for-amici-curiae-naacp-legal-defense-educational-fund-and-the-national-office-for-the-rights-of-the-indigent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

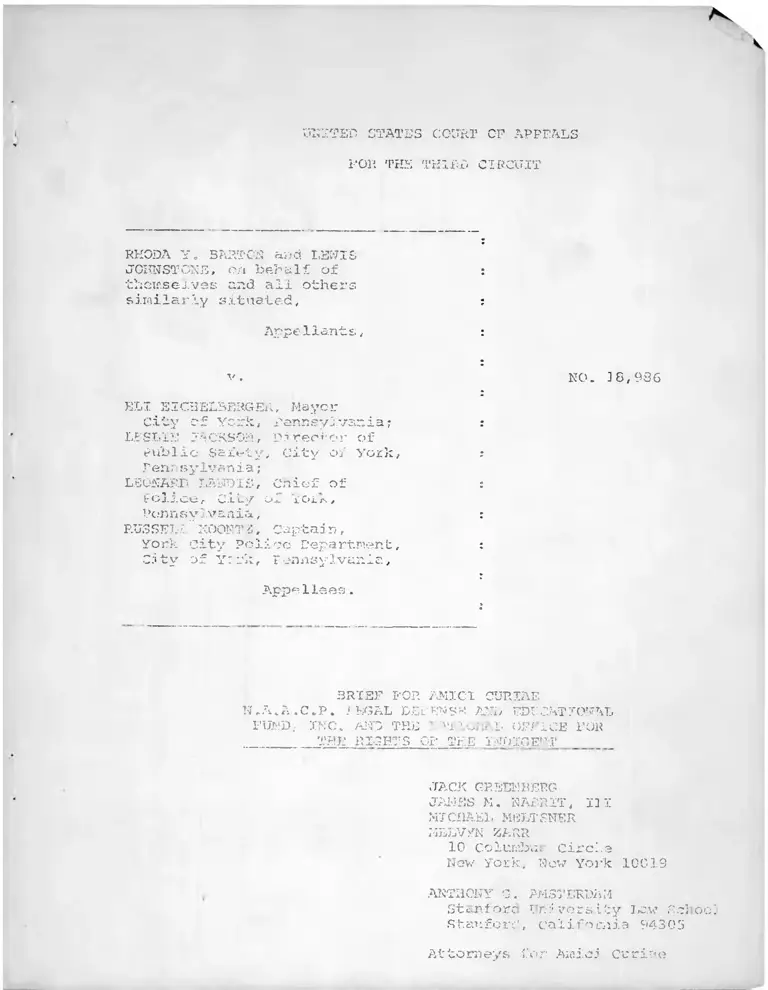

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

POP THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RHODA Y. BARTCH and LEWIS

JOHNSTONE, on behalf of

thoTf.seJ.ves and all others

similarly situated,

Appellants,

v .

ELI EICHEL5ER.GEA, Mayor

City of York, Pennsylvania;

LESLIE JaCKSOM, Director of

Public Safety, City of York,

Pen: syIvan ia;

LEONARD LANDIS, Chief of

tclj.ce, C.Li./ Ox iOi.js,

Pen n s v ji.v an i a,

RUSSELL-" KOOMT 3, Captain,

York City Police Department,

City of York, Pennsylvania,

Appellees.

NO. 3 8,98G

BRIEF POP. AMICI CURIAE

N . A . A . C . P . i L G A L DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND] INC. AND THE k. ' , L OFJ ICE FOR

________ THE RIGHTS OP TEE INDIGENT

J A C K GREENBERG

JAM ES M. N APR IT, 13 I

MJCHALl, MSLTSNER

MELVYN ZARR

10 coiurcbuCircle

New York. New York 10019

ANTHONY 0. AMSTERDAM

Stc nf ore l n:: ver s.i ty 2,aw Scl ool

Stanfork, California 94305

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

I N D E X

Pages

Statement of Interest of the Amici Curiae ......... 1

Argument:

Introduction .............. ................ 4

I. In View Of Its Finding That The Police

Conduct Here Was "Reprehensible" And

"Inexcusable," The District Court Erred

In Declining To Grant Injunctive Relief ... 8

A. Injunctive Relief Is The Only-

Workable Legal Remedy Where There

Is Serious And Widespread Police

Abuse Of Office...................... . 8

B. The Findings Of The District Court

Demonstrate That The Expansive

Equitable Relief, Which The District

Court Had The Power To Grant, Is

Required Here To Protect Appellants!

Constitutional Rights .............. 2C

Conclusion ........ ......................... 24

AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1970) ...................... ........ 20

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F.2d 649

(5th Cir. 1963) ...... '..... ..................... 17

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir.

1963), cert. den., City of Jackson v. Bailey,

376 U.S. 210 (1964) .............................. 16

Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962) ....... ....... 20,^2

Baker v. City of St. Petersburg, 400 F.2d

294 (5th Cir. 1968) .............................. 22

<

Basista v. Weir, 340 F.2d 74 (3d Cir.

1965) .... ....................................... 20

Cases (Continued) Pages

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294

(1955) 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) 11

Butcher v. Rizzo, C.A. No. 69-3000

(E.D. Pa., September 8, 1970) ........... ...... 12

Cottonreader v. Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492

(M.D. Ala. 1965) 12

Cunningham v. Grenada Municipal Separate

School District, 11 Race Rel. L. Rptr. 1776

(N.D. Miss. 1966) 12

Cunningham v. Ingram, N.D. Miss., C.A. No.

WC 6630 ......................... 12,14

Dawkins v. Green, 412 F.2d 644 (5th Gir.

1969) 11

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S. 479 (1965)...... 11

Gomez v. Layton, 394 F.2d 764 (D.C. Cir.

1968) ..................................____... 12

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964) ........... 20

Hague v. C.I.O., 307 U.S. 496 (1939) .......... 11,12

Hicks v. Knight, 10 Race Rel. L. Rptr. 1504

(E.D. La. 1965) 12,13,22

Houser v. Kill, 278 F. Supp. 920 (M.D. Ala.

1968) 12

Hurwitt v. City of Oakland, 247 F. Supp. 995

(N.D. Cal. 1965) ............................... 11

Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197 (4th Cir.

1966) 3,7,12,13,14,15

Lee v. Macon County, 267 F. Supp. 458

(1969) 23

Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1963) ................ 9

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 447 (1966) ......... 5

Monroe v. Pape, 3 65 U.S. 167 (1961) .... . 9

li

Cases (Continued) Pages

N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson, 357 F.2d 831 (5th Cir.

1966) . ...... ......................... ...... 12,13

Pierson v. Ray, 386 U.S. 547 (1967) .......... 9

Powelton Civic Horae Owners Association v.

Department of Housing and Urban Development,

284 F. Supp. 809 (1968) ............. ....... 17

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) ......... 11,20

Schneil v. Chicago, 407 F.2d 1084 (7th Cir.

1968) 12

Sellers v. Johnson, 165 F.2d 877 (8th Cir.

1947) 17

Smith v. Hill, 285 F. Supp. 556 (E.D. N.C.

1968) 11

Strasser v. Doorley, 309 F. Supp. 716

(1970) 18

Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) 5,10

Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga.

1965) ....... '........... ................... 11

United States v. City of Grenada, 11 Race Rel.

L. Rptr. 1782 (N.D. Miss. 1966) ............. 12,22

United States v. Clark, 249 F. Supp. 720

(S.D. Ala. 1965) 12,22

United States v. Edwards, 333 F .2d 575

(5th Cir. 1964) 18

United States v. W. T. Grant Co., 345 U.S.

629 (1953) 16,17

United States v. Jefferson County Board of

Education, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) ..... 23

United States v. McCleod, 385 F.2d 734 (5th

Cir. 1967) 21

United States v. National Lead Co., 332 t.S.

335 (1946) 20

United States v. Oregon State Medical Society,

343 U.S. 326 (1952) 17

United States v. Richberg, 308 F.2d 523 ;’5th

Cir. 1968) .......... ̂. ..................... 16

- iii -

Cases (Continued) Pages

Valle v. Stengel, 176 F.2d 697 (3d Cir. 1949) .. 11,12

Wheeler v. Goodman, 208 F. Supp. 935 (W.C. R.C.

1969) ........................ ............... 13,21

Williams v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D.

Ala. 1965) ................ ................ 3,12,13

Statute:

42 U.S.C. § 1983 ........................... ... 9

Texts:

Chevigny, Police Power (1969) .................. 5

Cray, The Big Blue Line (1967) ........... 5

Rote, The Federal Injunction as a P.emedy for

Police Conduct, 78 Yale Law Journal 143

(1968) ................................. ..... 10

Report of the Rational Advisory Commission on

Civil Disorders (GPO #1968-0-291-729,

March 1, 1968) ...... ...................... 5,7

Report of the President's Commission on Law

Enforcement and Administration of Justice,

"The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society"

(GPO #1967-0-239-122, 1967) ........... ...... 5

/

iv

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE THIRD CIRCUIT

RHODA Y. BARTON and LEWIS

JOHNSTONE, on behalf of

themselves and all others

similarly situated,

Appellants,

v.

ELI EICPIELBERGER, Mayor

City of York, Pennsylvania;

LESLIE JACKSON, Director of

Public Safety, City of York,

Pennsylvania;

LEONARD LANDIS, Chief of

Police, City of York,

Pennsylvania;

RUSSELL KOONTZ, Captain,

York city Police Department,

City of York, Pennsylvania,

NO. 18,986

Appellees.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST OF THE AMICI

Amicus N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. (hereinafter Legal Defense Fund) is a non-profit

corporation, incorporated under the laws of New York and

thereby authorized to function as a legal aid society. For

thirty years, its principal, purpose has been the prosecution

of lawsuits aimed at obtaining and maintaining the constitu

tional rights of minority groups and eradicating conditions

of racism and injustice which afflict black Americans. Amicus

National Office for the Rights of the Indigent (hereinafter

NORI) was established by the Legal Defense Fund as a separate

organization in 1965. Its establishment reflects the recogni

tion that the problems of race and of poverty are inextricably

linked, and that the goal of equal justice demands the defense

of all the poor and powerless against oppression.

Counsel for the amici have sued in federal courts at all

levels and in all areas of the Nation in defense of the con

stitutional rights of minority groups! Specifically, we have

sought through legal process to guarantee the full and equal

access of all citizens to public facilities -- hospitals,

schools, transportation. We have sought to vindicate the

right to vote, the right to equal employment opportunities,

the rights against discrimination in housing, in the adminis

tration of justice, and in every aspect of public life. Amici

have also defended the rights of individuals and minority

group organizations to protest freely against discrimination

and unjust treatment at the hands of the government.

In defending the rights of black and poor people, we

have attempted to be responsive to the needs of our constituency.

As new needs are perceived by the community, if the problems

are capable of judicial solution, we have sought to develop the

legal tools to me.et them. Thus, the "police problem," currently

much discussed both inside and outside the black community, has

become a major area of our concern.

2

Amici1s special concern with the vexing and intractable

problems of police lawlessness and discrimination is the source

of our interest in the present case. This appears to us a

momentous litigation — in many ways, a uniquely important

litigation -- calling into question the capacity of courts

and of lav; to deal creatively and effectively with these

problems. This is so because the broad-scale repression by

the police of the black community of York proved on this

record is a particularly egregious example of the "police

problem" in its most explosive form and also of the critical

need to find workable judicial solutions of that problem if

its most explosive outcomes are to be avoided. Courts and

law can have no more important function, nor any more decisive

test.

Involved in this lawsuit are issues of officially

sanctioned racism, official lawlessness, and government

accountability. Amici have sued in federal courts in the

past to resolve these issues as they presented themselves in

other contexts. E .g „, Lankford v. Gelston, infra; Williams v.

Wallace, infra; Cunningham v. Ingram, infra. Never has their

resolution been more imperative than it is now.

As amici, we submitted a brief and participated in the oral

argument of this matter before the district court. Our brief

there focused on the issue whether the district court had the

legal authority and the practical capacity to grant the injunc

tive remedies required to curb the police abuses shown by the

record in this case.

3

In our brief here, we propose to show that, on the facts

of this case, as the district judge found them, the court below

abused its discretion in refusing to grant equitable relief.

We submit that this case represents an extreme instance in

which federal judicial intervention is required to protect

rights threatened by irresponsible local police. Although we

think the district court erred in its consideration of the

record in that it, inter alia, (1) imposed the wrong burden

of proof to appellants' evidence, (2) discounted appellants'

unrebutted evidence of police abuse, and (3) failed to consider

the record of police abuses and discrimination in its totality

-- amicj- do not in this brief dispute the district court's

findings of fact. Our argument here is limited to the issue

whether, solely on the basis of the abuses which the district

court found to have occurred, an injunction should have issued.

ARGUMENT

INTRODUCTION

As our Statement of Interest implies, the ultimate issue

posed by this case is whether the judiciary can respond effec

tively to abuses of the constitutional rights of black citizens

by the police -- abuses wh: ch threaten the very fabric of our

constitutional system.

l

4

Police abuses are not unknown outside of York, Pennsylvania.

They have occurred in communities all across the Nation. See

cases cited, pp.11-12, infra; and see CHEVIGNY, POLICE POWER

(1969); CRAY, THE BIG BLUE LINE (1967).

The Supreme Court has several times noted that police

illegality is a serious and pervasive problem. E.g., Miranda

v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436, 447 (1966); Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S.

1, 14-15 (1968). That problem has been the subject of concern

of two recent. Presidential Commissions. Report of the National

Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (GPO #1968-0-291-729,

March 1, 1968); Report of the President's Commission on Law

Enforcement and Admiaiistration of Justice, "The Challenge of

Crime in a Free Society" (GPO #1967-0-239-122, 1967). Both

of these; government reports conclude that unjust and unequal

treatment at the hands of the police is one of the primary

causes of citizens' disrespect for law:

" [T]o many Negroes, police have come to

symbolize white power, white racism

and white repression. And the fact is

that many police do reflect and express

these white attitudes. The atmosphere

of hostility and cynicism is reinforced

by a widespread perception among Negroes

of the existence of police brutality and

x corruption and of a 'double standard' of

justice and protection -- one for Negroes

and one for whites." (Report of the

National Advisory Commission on Civil

Disorders (GPO #1968-0-391-729, March 1,

1968) at 93.)

This is not to say -- thankfully — that brutality and

racial discrimination are inevitable, or even ordinary attributes

of the police. Good policemen are neither brutes nor bigots;

and nothing in the nature of their important and difficult work

requires that they be. For this reason, no issue presented

in this case requires that the federal court intrude itself into

conflict with any necessary or legitimate police authority or

function. Rather — again, thankfully — the interest of the

police in law enforcement and public security could only be

enhanced by the proper exercise of the federal courts' processes

to recall York's brutal and biased officers to their legal and

constitutional responsibilities. For the cost to law, to public

order and security, when a community feels itself powerless

against illegal police oppression, is immeasurable.

There is no war, we think, between police efficiency in

the maintenance of order and the preservation of basic decency

and civilization in dealings between police officers and the

community. To the contrary, police efficiency and police

decency are mutually interdependent, although the practices

of considerable numbers of York policemen are at war with both.

That is all the more reason why this case absolutely requires

the exercise of judicial injunctive powers. Public safety,,

as well as the quality of life of countless citizens of York,

imperatively calls for such a remedy.

In extensive findings of fact, the district court discussed

five incidents of what it considered "inexcusable" police conduct.

/

6

We think that the court erred in its findings, and that the

record indicates a greater number and vastly more serious inci

dents of police crime than those enumerated in the opinion below.

However, even assuming the facts as the district court found

them to be, this case presents an almost incredible spectacle

of police abuse: uncontrolled terrorism of the black citizens

of York by the systematic use of oppressive practices ranging

from racial epithets to the unprovoked shooting of children.

In scope and intensity, the police conduct here is similar

to that condemned by the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

in the leading case of Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F.2d 197 (4th

C.ir. 1966) . In Lankford, the court characterized the evidence

of official conduct as a "vast . . . demonstration of disregard

of private rights." Id., at 204. And here, as in Lankford,

"the grave character of the [police] . . . conduct places a

strong obligation on the Court to make sure that similar conduct

will not recur." Id_. , at 203 .

Recent history shows that the sort of police violence

demonstrated in this case and in Lankford, has often been a

direct and immediate cause of the civil disorders which have

plagued our cities. Report of the National Advisory Commission

on Civil Disorders, supra, at 158. Indeed, although it is .

difficult to disentangle cause and effect in tlese matters, there

is some evidence that police violence sparked the disorders in

York in the summer of 1969. (N.T. 695) Fortunately, however,

although the police abuses here have been worse than elsewhere,

/

7

r\

<3 6-

\ l is

d vJ h W

i sjx 101

UJ<L^f<- 3 ^ 3 C c f

0

i“? 7 /

the black community of York brought its appeal to the courts.

In so doing, it has presented the courts with the opportunity

to interpose the rule of law into and against the ever-escalating

cycle of police and community violence. The failure of the

courts to speak out clearly in condemnation of government

lawlessness will serve only to exacerbate an already dangerous

and deteriorating situation.

I.

A. Injunctive Relief Is The Only Workable

Legal Remedy Where There Is Sprious And

Widespread Police Abuse Of Office.

Although the district court found that, on the whole,

the conduct of the York police department was "commendable,"

it characterized five incidents of police excess as "repre

hensible" and "inexcusable." This "reprehensible" conduct,

summarized by the court at 311 F. Snpp„ .1132, 1155, included

indiscriminate and excessive shootings by police officers,

abusive language and racial slurs and insults, manhandling

of black citizens, and the use of the slogan, "white power"

by York police officers. We think, in view of its findings

with regard to these five instances of police wrong-doing, that

the district court erred in refusing to grant the injunctive

relief requested by appellants.

/

8

The injunction is a particularly well-suited remedy

where police misconduct threatens constitutional freedoms.

In recent times, as other judicial remedies have proved

inadequate, it has been used more and more frequently by

federal courts seeking to protect the rights of poor and

minority communities from police lawlessness.

Experience has demonstrated — and courts have noted —

that civil damage actions against police officers are not

effective to curb police abuses. The Supreme court has held

that a tort remedy is provided by 42 y.S.C. § 1983 for

unconstitutional police behavior. Monroe v. Pape, 365 U.S.

167 (1961). However, the scope of the tort remedy is limited

by doctrines thought appropriate to restrict the potential

liability of individual police officers, Pierson v. Ray, 386

U.S. 547 (1967); and several additional factors operate to

render damage actions a fruitless remedy. A federal tort action

is generally a costly and risky affair, and the typical long

delay before final judgment vitiates any value a favorable

decision might have as a deterrent to police misconduct. Those

who do sue subject themselves to further harassment from the

police. Similarly, witnesses who might testify against the

defendant officer are often intimidated and threatened with

recrimination. Because of these severe burdens, damage actions

are rarely pursued by would-be plaintiffs who are poor and black.

It was in part because the suit for damages constituted

a "worthless and futile" remedy, Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643,

652 (1961) that the Supreme Court sought to control police

9

illegality through the exclusionary rule in criminal cases.

The exclusionary rule itself, however, is a device of limited

effectiveness. It is insufficient to meet the situation of

wholesale and egregious police violations of community rights

such as are shown by the record here; and it is of no value

whatsoever when those violations are committed mainly against-

innocent parties, when the police undertake to mete out summary

punishment without criminal charges, or when searches are not

involved. Only recently, in Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968),

the Court had occasion to discuss the* inadequacy of the

exclusionary rule as a means to curb widespread police abuses.

There, Chief Justice Warren, speaking for the Court, wrote:

"The wholesale harassment by certain

elements of the police community, of

which minority groups, particularly

Negroes, frequently complain, will not

be stopped by the exclusion of any

evidence from any criminal trial."

(Id., at 14-15)

However, the Court made it clear that it did not intend

that victims of broad-scale police repression should be left

without a legal remedy:

" . . . [0]ur approval of legitimate and

restrained investigative conduct under

taken on the basis of ample factual justi

fication should in no way discourage the

employment of other remedies than the ex

clusionary rule to curtail abuses for which

that: sanction may be inappropriate." (Id. ,

at 15.)

1/

What remains is the broad equity po\\er of the Court.

1/ The application of injunctive process in suits against the

police is the subject of a recent note published in the Yale Law

journal. Note, The Federal Injunction as a Remedy for Uncon

stitutional Police Conduct, 78 YALE LAW JOURNAL 143 (T968} .

10

Of course, federal courts are not strangers to the use of

injunctive process to remedy constitutional deprivations.

The Supreme Court has often required the use of injunctions

when other avenues of relief were likely to be unavailing.

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), 349 U.S.

294 (1955); Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962); Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964); Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U.S.

479 (1965) .

Specifically, in Hague v. C ,I.0,, 307 U.S. 496 (1939),

the Court upheld the power of a federal district court to

enjoin a mayor and police department from a "deliberate policy"

of constitutional violations. In Hague, supporters of a labor

organization successfully sued to enjoin city officials from

pursuing and threatening to pursue a course of arrests and

prosecutions based upon unconstitutional city ordinances, and

other practices including the illegal use of force and violence

by police officers, aimed at harassing union organizers and

discouraging them from the exercise of their First Amendment

rights.

For thirty years the lower fedora! courts have applied

the Hague injunctive remedy to cases of police abuse of office.

E.g., Valle v. Stengel, 176 F.2d 697 (3d Cir. 1949); Dawkins v.

Green, 412 F.2d 644 (5th Cir. 1969); Smith v. Hill, 285 F. Supp.

556 (E.D. N.C. 1968); Turner v. Goolsby, 255 F. Supp. 721 (S.D.

Ga. 1965)(injunctive order set uut in full in 11 RACE REL. L.

RPTR. 158, 163-164); Hurwitt v. City of Oakland, 247 F. Supp.

995 (N.D. Cal. 1965). In instances of police brutality and

repression of a black community similar to what the facts

show in York, federal injunctive process has invariably been

forthcoming. Lankford v. Gelston, 364 F .2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966);

N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson, 357 F.2d 831 (5th Cir. 1966); Williams

v. Wallace, 240 F. Supp. 100 (M.D. Ala. 1965); United States

v. Clark, 249 F. Supp. 720 (S.D. Ala. 1965); Cottonreader v.

Johnson, 252 F. Supp. 492 (M.D. Ala. 1965); Houser v. Hill,

278 F. Supp. 920 (M.D. Ala. 1968); Hicks v. Knight, 10 RACE

REL. L. RPTR. 1504 (E.D. La., C.A. No. 15727, orders of July

]0 and July 30, 1965, per Christenberpy, J.); Cunningham v.

Grenada Municipal Separate School District and United States

v. City of Grenada, 11 RACE REL„ L. RPTR. 1776, 1782-1783

(N.D. Miss., C.A. Nos. WC 6633, WC 6642, orders of September

13 and September 20, 1966, per Clayton, J.); Cunningham v.

Ingram, N.D. Miss., C.A. No. WC 6630, temporary injunction of

July 22, 1966, per Clayton, J.).

Injunctive relief against police harassment has been the

rule of this Circuit since the decision, 101 F.2d 774 (3d Cir.

1939), which the Supreme Court affirmed in Hague v. C.I.0.,

supra. See also Valle v. Stengel, supra. Butcher v. Rizzo,

C.A. No. 69-3000, (E.D. Pa., September 8, 1970.) It has recently

2/

been exercised in cases in other circuits, as well as in cases

2/ The District, of Columbia Circuit has lately reaffirmed

the power to enjoin police "vagrancy observation" practices

where a constitutional violation was claimed. Gomez v. Layton,

394 F.2d 764 (D.C. Cir. 1968). And the Seventh Circuit has

recognized equitable power to remedy police deprivation of the

rights of news reporters. Schnell v. Chic;ago, 407 F.2d 1084

(7th Ciri 1968).

12

In our

3 /

in which counsel for amici have participated,

experience, federal injunctions restraining widespread

violations of constitutional rights the police have often

proved the only workable instrument for first arresting and

then reversing the destructive cycle of violence that uncon

strained police abuse and repression of a minority-group

community unleashes. Thus Judge Johnson's injunction in

Williams v. Wallace, supra, brought an effective end to most

of the disorders surrounding the Selma-to-Montgornery March in

1965; Judge Christenberry1s injunction and subsequent orders

in Hicks v. Knight, supra, defused a potentially destructive

confrontation situation in Bogalusa, Louisiana, in the same

year; and Judge Clayton's similar use of injunctive process

3/ In Lankford v. Gelston , supra, the Baltimore City Police

Department had engaged in a series of unconstitutional searches.

The Fourth Circuit held that injunctive relief was not only

appropriate but mandatory as the only remedy likely to be

effective, even though the searches had admittedly come to an

end and the challenged police department policy had been

administratively reversed. Following Lankford, the court in

Wheeler v. Goodman, 209 F. Supp. 935 (W.D. N.C. 1969), enjoined

Charlotte police from harassment of a class of persons loosely

described as "hippies." Subsequently, a three-judge district

court declared the North Carolina vagrancy statute that had

been the principal instrument of the harassment unconstitutional,

and ordered plaintiffs' criminal records expunged. Wheeler v.

Goodman, 306 F. Supp. 58 (1969). The Fifth Circuit held in

N.A.A.C.P. v. Thompson, 357 F..2d 831 (5th Cir. 1966), that Jackson,

Mississippi police and other city officials should have been

enjoined from interfering, by the use- of harassing arrests, with

plaintiffs' right to peaceful protest.., Recent injunctive orders

by several district courts in that circuit are mentioned in

text, infra.

i

13

restored both public order and the enjoyment of basic civil

rights by black citizens in Grenada, Mississippi the following

year, Cunningham v. Ingram, supra.

Thus, equitable remedies answer a critical need in cases

of police-community conflict. For this reason, it is especially

significant that the York black community has placed its

reliance on the courts. As the repository of the law, the

judiciary has, in the last analysis, the duty to demonstrate

the efficacy of the law to curb abuses of "legal" authority.

That judicial duty was well put in Lankford:

"It is of the higliest importance to community

morale that the courts shall give firm and

effective reassurance, especially to those

who feel that they have been harassed by

reason of their color or their poverty."

(Lankford v. Gelston, supra, 3G4 F .2d, at

204.)

And it was precisely this judicial role which was not

appreciated by the district court here. In declining to grant

injunctive relief, although it found there to have been

substantial police wrong-doing, the court denied appellants

what Lankford and the Constitution entitled them to: an

unequivocal, firm judicial declaration of their constitutional

right not to be subjected to police abuse. The district court's

mild and unreasoned conclusion that the police acted "repre-

hensibly" is an unsatisfactory disposition of this case because

it leaves unresolved the very issue which the appellants sought

to settle by bringing this lawsuit; namely, whether the police

violated constituuionally-protected rights in their treatment

l

of black York citizens during the days of civil disorder. Although

it may be implicit in its findings, we think the court below

14

erred in failing to specifically hold that the five incidents

of police abuse which it considered to be "transgressions"

were also violations of Due Process. .further, it was error

for the court not to hold that these "transgressions" of

constitutional rights called for equitable relief.

The unique remedies available in equity serve several

purposes in cases of this sort. The injunction is particularly

well-suited where, as here, as a result of hostility and fear

on both sides, communication between the police and the

community has reached a stalemate. A. court mandate would help

restore the balance in a community torn by civil strife by

breaking the tragic sequence of police-community violence.

As Judge Sobeioff aptly put it, where " [T]he sense of impending

crisis .in police-community relations persists, . . . nothing

[can] so directly ameliorate it as a judicial decree forbidding

the practices complained of." Lankford, at 204.

The lower court's factual finding that some of the police

conduct here was "reprehensible," buried deep in a fifty-four

page opinion, will do little to prevent the recurrence of

similar conduct in the future. Indeed, more than once in its

opinion, the court praised the police, and commended them for

their "restraint." We do not doubt that at times during the

period of civil disorder the behavior of some members of the

York police department was irreproachable. Moreover, we agree;

with the court that the riotous conditions which existed in

the City of York were such as to tax the abilities of the most

well-trained, well-intentioned officer. However, even if,

J 5

arguendo, the police conduct during the relevant period was in

some respects praiseworthy, this fact does not detract from

the seriousness of the numerous incidents of misconduct.

Injunctive relief is the only guarantee that the illegal acts

which the court did find the police guilty of do not recur.

The lower court's opinion gives the police -- who have every

reason to believe that they have won a complete victory —

no incentive to change their behavior. It leaves them utterly

"free to return to [their] old ways." United States v . W .T .

Grant Co., 345 U.S. 629, 632 (1953).

In Grant, a case outlining the criteria for the granting

of injunctive relief where the illegal conduct had terminated

at the time of trial, the Supreme Court noted that injunctive

relief should be granted whenever thexe is a "cognizable danger

of recurrent violation." Grant, supra, at 633. And in United

States v. Ricnberg, 308 F.2d 523, 530 (5th Cir. 1968), the

Fifth Circuit found that the district court's refusal to

enjoin defendant's discriminatory practices for the reason

that there was no showing of discrimination at the time of trial

and for mere than seven months prior to trial, was an abuse

of discx*etion in light of the fact that there was no indication

that the defendant intended to change his policy. See also

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F .2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963), cert. den.,

City of Jackson v. Bailey, 376 U.S. 210 (1964) .

Here, every indication from the record and from the opinion

of the court below is that police abuse in York will continue.

/

16

Nothing in that opinion will prevent the strong animosities

and racial prejudices which, according to the court, exist

among some members of the York police force, from giving birth

to new excesses and abuses. Although it might not eliminate

the root cause of these prejudicial feelings, a clear judicial

statement that such overt discriminatory conduct is illegal

and impermissible would undoubtedly affect some change in

day-to-day police practices.

Injunctive relief is necessary here for the additional

reason that it would put to rest "a dispute over the legality

of challenged practices." Grant, supra, 632. Such a judicial

mandate is needed to "firmly and publicly establish the . . .

right(s)" which the appellants claim and which the lower court

has indirectly recognized. Powe.tt.on Civic Home Owners

Association v. Department of Housing and Urban Development,

284 F. Supp. 809, 839 (1968) ( E.D. Pa.). See also United

States v. Oregon State Medical Society, 343 U.S. 326, 333 (1952);

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F.2d 649 (5th Cir. 1963);

Sellers v. Johnson, 165 F.2d 877, 883 (8th Cir. 1947).

Perhaps most important, injunctive relief is here called

for to demonstrate to a community which feels helpless in the

face of a seemingly powerful police force and an unresponsive

local government that the courts will safeguard constitutional

rights. The decision below reaffirms the unfortunate but real

belief of the York black citizen that his rights are not entitled

to judicial protection, but depend on a policeman's whim. The

/

acts of misconduct described by the court below were not

instances of isolated, careless indiscretions, but evidence

an attitude and a policy of widespread disrespect and, indeed,

contempt for the rights of York blacks. It is this attitude

which so intimidates black citizens from the exercise and

enjoyment of their constitutionally guaranteed freedoms, and

which can only be checked by judicial reaffirmance of constitu

tional standards. See United States v . Edwards, 333 F.2d 575,

579 (5th Cir. 1964) (dissenting opinion, Judge Brown.)

Nor is it any answer for the district court to say that

injunctive relief is not required because the police abuses

were few in number. In virtually every case involving police

abuse, where illegal acts have taken place, equitable relief

has been granted. Note, YALE LAW JOURNAL, supra, 146 (n. 17).

It is manifest on the face of the record that the violations

here were both substantial and numerous. Even if, however,

appellants had proved only one serious abuse, equity would

for that single transgression afford a remedy.

A recent opinion by District Court Judge Pettine of Rhode

Island illustrates the necessity for the use of equitable

remedies whenever police abuse is shown. Strasser v. Doorley,

309 F. Supp. 716, 725 (1970)(U.S.D.C. D. R.I.). In that case,

peddlers of an "underground" newspaper charged that they were

being harassed by the police in an effort to prevent them from

selling their paper in downtown Providence. Judge Pettine

found that of the several incidents of alleged police harassment

which the plaintiffs sought to prove, only one had merit. That

18

incident occurred when

arrested while selling

to verbal abuse by the

of the judicial relief

noting:

three of the plaintiffs were illegally

the paper, manhandled, and subjected

police. Judge Pettine's discussion

called for by this incident is worth

"The police of a community are a part of

our system of justice in daily contact with

the public. There is no dramatic contest

between society and law enforcement personnel

whc are charged with enforcing the law which

they do not enact and maintaining order. Of

course, they do not possess unlimited powers

to deter or reduce disobedience and the

exercise of personal discretion is an inescapable

part of their job.

However, deprivation of civil rights demands

immediate ancl unqualified redress. The federal

court has power t;o vindicate such wrongs by

employing mandatory injunctive procedures against

the officials involved. Lankford v. Gelston, 364

F .2d 197 (4th Cir. 1966).'

The Mall arrest incident was a deliberate,

unwarranted police act and as to the same,

the court declares it to have been, at the

very least, a violation of plaintiffs' first

amendment rights, and the court grants declaratory

relief. However, it refrains from injunctive

action believing as it does that the police

officials in the instant case in the light of the

court's declaration do not need the coercion of

injunctive relief. Id_., at 725, 726. (Emphasis

added)

Thus, although Judge Pettine thought that the plaintiffs

had made out their claim of police hc.rassment as to only one

of a number of incidents which they sought to prove, he was cf

the opinion that police illegality o:i the one occasion was,

in itself, enough to warrant judicial redress.

i

19

B. The Findings Of The District Court Demonstrate

That The Expansive Equitable Relief, Which

The District Court Had The Power To Grant, Is

Required Here To Protect Appellants' Constitu

tional Rights.

Needless to say, injunctive relief must be sufficiently

thorough to curb the police misconduct found by the court

below in all of its aspects. That the flexible equity power

of the courts to remedy constitutional violations is ample

to this end cannot be doubted. The courts have wide discretion

to tailor an injunctive decree to the particular factual

situation of the case so as to secure, as expeditiously and

effectively as possible, the vindication of constitutional

rights. The Supreme Court recognized this principle in Brown

v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294 (1955). "[T]raditionally,

equity has been characterized by a practical flexibility in

shaping remedies...." (Id., at 300.) For other exemplifications

of the point, see Griffin v. County School Board of Prince

Edward County, 377 U.S. 218 (1964); Alexander v. Holmes

County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1970)r and the re-

apportionment cases, e.g. Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962);

4/Reynolds v._Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964). In one case in-

4/ In the anti-trust area, it is firmly established that

courts have the power to grant relief appropriate -to the

factual situation. In construing Section 4 of the Sherman .

Act, 15 U.S.C. § 4, which gives the federal courts power to

enjoin anti-trust violations, the Court has held that the

"essential consideration [governing remedial injunctive re

lief] is that the remedy shall be as effective and fair as

possible in preventing continued or future violations. . .

in the light of the facts of the particular case." United

States v. National Lead Co., 332 U.S. 335 (1946). Remedial

power is broader still in civil rights cases, where the federal

courts are under statutory mandate to fashion efficient re

medies fdr violations of vital constitutional rights.

42 U.S.C. § 1988; see Basista v. Weir, 340 F.2d 74 (3d Cir. 1965) .

20

volving, like this one, illegal police conduct, the Fifth

Circuit held that a district court had expansive power to

afford complete relief. United States v. McCleod, 385 F.2d

734 (5th Cir. 1967). There, in a suit brought by the United

States to enjoin harassment arrests and prosecutions of in

dividuals who had sought to exercise the right, to vote, the court

indicated that an order would be appropriate that required

county officials to return fines, expunge arrest records, and

reimburse the aggrieved parties for costs including attorneys'

fees incurred in the defense of unconstitutional state criminal

prosecutions. Accord: Wheeler v. Goodman, note 3, supra.

It remains to consider the elements of appropriate relief

here. We have argued that the facts of this case show such

purposeful, pervasive, uncontrolled wrong-doing by the York

police that the lower court's mere condemnation of particular

instances of misconduct will not sufficiently protect appellants'

rights. Adequate protection requires that the district court go

to the heart of the problem: the organization of the York police

department. Of course, the district court cannot and should not

itself undertake to run the department. But it could well require

the establishment of new structures within the department that

will assure the capacity of responsible police officials them

selves to promulgate and administer a code of internal regulation

adequate to safeguard plaintiffs and the York community against

a recurrence of the intolerable constitutional violations of the/

past.

21

Unquestionably, the extensive relief which we think is

required in this case goes beyond the commonplace, but it

would no*: be unprecedented. Courts have not hesitated to order

a restructuring of police department practices where necessary

to enforce the Constitution. See Baker v. City of St. Peters-

Vburg, 400 F.2d 294 (5th Cir. 1968).

It is manifest from the facts of record that similarly

expansive relif is required in this case. By propsed orders

submitted to the court below, the appellants detailed the ele

ments of the relief they sought. Briefly, they requested,

inter alia, an injunction against each of the specific sorts

of police lawlessness, violence, and encouragement of private

violence established by the record; the appointment of a master

to hear citizens' complaints; the requirement that an effective

code of regulations be promulgated governing police behavior

and providing for the discipline of offending officers; in

vestigation of officers primarily responsible for abuses al

ready proved; and, perhaps most important, the maintenance of

5 / For example, in United States v. Clark, supra, the district

court restrained Sheriff Jim Clark of Selma, Alabama "from any

further use of the Dallas County posse, as that organization

is presently constituted, in connection with any racial matters.

(249 F.Supp., at 730) In the City of Grenada litigation,

supra, Judge Clayton, finding that municipal law enforcement

authorities had wilfully failed to protect black children from

violence by white hooligans in connection with school de

segregation, issued an extensive injunctive order. 11 RAPE

REL. L. RPTR., at 1782-1783. See also the order entered by

Judge Christenberry in the I-Iicks v. Knight litigation, supra,

when certain law enforcement officials of Bogalusa, Louisiana

failed to comply with the court's initial order to provide

police prtection to black civil rights demonstrators in the

city. 10 RACE RET- L. RPTR., at 1507-1508

22 -

continuing jurisdiction by the district court to insure com

pliance with its orders and any supplemental orders that

§ ymight be required.

Counsel for amici are agreed with appellants that those

are essential elements of relief if police-community relations

in York are to see any improvement. The courts should obviously

eschew undue intervention into the internal operations of a

city police department. In the first instance, the department

itself should be responsible for designing and promulgating

its policies and regulations, disciplining its men, and thereby

insuring adherence to constitutional standards. However, our

experience confirms us in the view that, in a situation such as

this one where there has been a vast disregard for constitutional

rights, the internal policies of the police must first be made

specific and visible, second be made constitutionally sound,

and third be made subject to continuing scrutiny by the court.

The relief which appellants requested would not inhibit the

police department in the proper exercise of its duties. On the

contrary, .it is designed to afford the maximum opportunity for

self-regulation consistent with effective review by the court to

assure constitutional guarantees.

6/ School desegregation cases furnish a good example of the

relationship a court may establish with a public agency to

insure compliance with its orders. See Lee v. Kacon County,

267 F.Supp. 458, where a Three-Judge Court ordered Alabama

school districts to file periodic reports for review by the

Court. See also, United States v. Jefferson County Board

of Education, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) (en banc).

23

CONCLUSION

For the reasons described above, the judgment of the

district court should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M NABRIT, III

MICHAEL MELTSNER

MELVYN ZARR

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University Law Schc

Stanford, California 94305

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

i

24