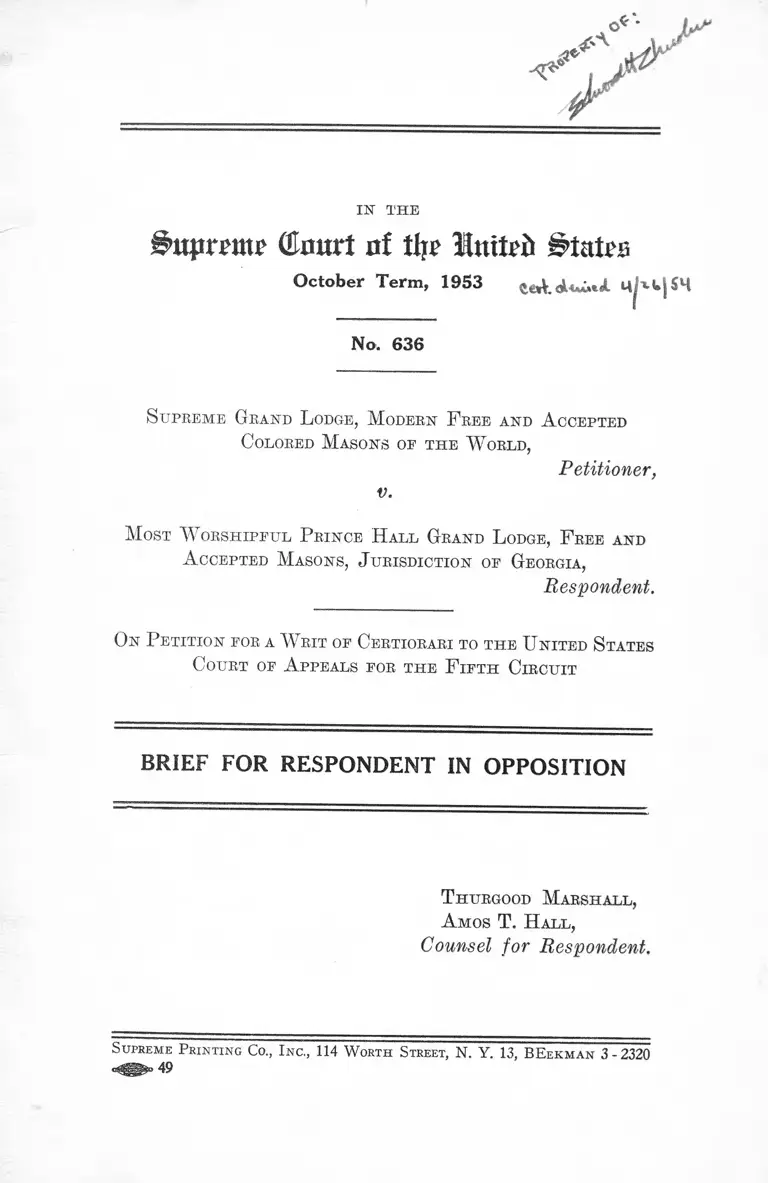

Supreme Grand Lodge, Modern Free and Accepted Colored Masons of the World v. Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons, Jurisdiction of Georgia Brief for Respondent in Opposition

Public Court Documents

April 15, 1954

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Supreme Grand Lodge, Modern Free and Accepted Colored Masons of the World v. Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons, Jurisdiction of Georgia Brief for Respondent in Opposition, 1954. ae4c2e7f-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/24e55ff6-4724-4e1f-943b-52a1abc37979/supreme-grand-lodge-modern-free-and-accepted-colored-masons-of-the-world-v-most-worshipful-prince-hall-grand-lodge-free-and-accepted-masons-jurisdiction-of-georgia-brief-for-respondent-in-opposition. Accessed December 13, 2025.

Copied!

IN THE

^uprrmr (tart of % luitrii Btutes

October Term, 1953 <*e»V.<A w»A q|x«.|S4

No. 636

Supreme Grand L odge, Modern F ree and A ccepted

Colored Masons oe the W orld,

Petitioner,

v .

Most W orshipful Prince Hall Grand L odge, F ree and

A ccepted Masons, J urisdiction of Georgia,

Respondent.

On Petition for a W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of A ppeals for the F ifth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

T hurgood Marshall,

A mos T. H all,

Counsel for Respondent.

Supreme Printing Co., I nc,, 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BE ekm an 3 - 2320

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B e low ............................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ..................................................................... 1

Questions Presented....................................................... 2

Statement ......................................................................... 2

Argument ......................................................................... 8

I—The petition fails to comply with Rule 38(2)

of this C o u rt ................................................... 8

II—The petition neither presents a federal ques-

nor does it raise any important question of

local law decided in a way probably in con

flict with applicable local decisions............ 8

Table of Cases

Ancient Egyptian Arbic Order N. M. S. v. Michaux,

279 U. S. 737 ............................................................. 8 fn.

Atlantic Paper Co. v. Jacksonville Paper Co., 184 Ga.

205, 190 S.’ E. 777 (1937) .......................................... 8,9,10

Creswill v. Grand Lodge, Knights of Pythias of

Georgia, 225 IT. S. 246 ............................................... 8 fn.

Creswill v. Grand Lodge Knights of Pythias of

Georgia, 133 Ga. 837, 67 S. E. 188 (1910), rev. ot.

gnds., 225 U. S. 246 ................................................... 10

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 6 4 .......... 8, 9

United States v. Rimer, 220 U. S. 547 .......................... 8

Other Authority

United States Supreme Court, Rule 38(2) 8

IN THE

ĵ itjnrpmp Court of thr Unitrib Btutw

October Term, 1953

No. 636

Supreme Grand L odge, Modern F ree and A ccepted

Colored Masons of the W orld,

Petitioner,

v.

Most W orshipful Prince H all Grand L odge, F ree and

A ccepted Masons, J urisdiction of Georgia,

Respondent.

On P etition for a W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of A ppeals for the F ifth Circuit

-------------------------------------- o------------------------------------- -

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION

Opinions Below

The opinion of the District Court (R. 1170-1185) is

reported at 105 F. Supp. 315. The opinion of the Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the dissenting opinion

(R. 1226-1231) are reported at 209 F. 2d 156.

Jurisdiction

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set forth

in the petition.

2

Question Presented

No question is presented in the petition.

Statement

Respondent, a Georgia corporation, instituted this

action on February 13, 1951, in the United States District

Court for the Middle District of Georgia against petitioner,

an Alabama corporation doing business in the State of

Georgia. Federal jurisdiction is based upon diversity of

citizenship and the requisite jurisdictional amount. The

complaint alleged that petitioner was engaged in unfair

competition with respondent (R. 2-11).

History of Petitioner and Respondent

Respondent’s evidence demonstrated that on March 6,

1775, Prince Hall, a free Negro, and fourteen other free

Negroes were initiated into the Masonic fraternity by

British Army Lodge No. 441 (R. 53, 249). A year later,

just prior to the evacuation of Boston by the British, this

Army Lodge gave to Prince Hall and his group of followers

a license or permit to meet as a lodge of Masons in accord

ance with the Masonic practice and custom of the day

(R. 53-54). Under that license African Lodge No. 1 was

organized in 1776 in the City of Boston with Prince Hall

as its first master (R. 54). The intent of the Army Lodge

was apparently that this permit should serve as temporary

authority until a more formal warrant could be secured

from the Grand Lodge of England (R. 56). After the

Revolutionary War, Prince Hall requested the Grand

Lodge of England to issue a warrant for this lodge. On

September 29, 1784, the Grand Lodge of England war

ranted this group as African Lodge No. 459 under the

authority of the Grand Master of England (R. 57, 1075).

Prince Hall was named the master of this lodge (R. 58).

3

In 1791 Prince Hall called an assembly of all the Negroes

in the craft and, in accordance with Masonic law and author

ity of that time, the African Grand Lodge was formed.

This method of forming a new grand lodge is known in

Masonic language as an “ assembly of the craft” (R. 58,

1024). The African Grand Lodge then proceeded to war

rant local lodges under its authority (R. 58-59). Soon

after Prince Hall died in 1807, a delegate convention con

sisting of representatives of three lodges met in Boston

and changed the name of African Grand Lodge to Prince

Hall Grand Lodge (R. 61).

Respondent traces its origin directly to Prince Hall and

African Lodge No. 459. Three lodges of Negro Masons

were established in the State of Georgia immediately fol

lowing the Civil War. Two of these lodges had been

chartered by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of Massachu

setts and the other by the Prince Hall Grand Lodge of

Pennsylvania (R. 165). These three lodges met in conven

tion in 1870 and, in accordance with Masonic jurisprudence,

respondent was formed under the name “ Most Worshipful

Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State

of Georgia” (R. 62, 165-167).

Respondent has had a continuous existence in the State

of Georgia since 1870 (R. 166-167, 177). Respondent was

incorporated in the State of Georgia in 1890, receiving a

charter from the Superior Court of Chatham County under

the name “ Most Worshipful Union Grand Lodge of the

Most Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Ancient Free

and Accepted Masons for the State of Georgia” (R. 166-

167). In 1936 this charter was renewed and amended by

proper order of the court and respondent’s name was

changed to “ Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge

A. F. and A. M. of Georgia” . The letters “ A. F. and

A. M.” are generally understood to mean Ancient Free and

Accepted Masons (R. 169). The charter was again prop-

4

erly amended in 1950 and the name changed slightly to its

present form: “ Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand

Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons, Jurisdiction of

Georgia” (E. 167).

Considerable expert evidence was introduced which

demonstrated that respondent is a regular and legitimate

body of Masons, organized in conformance with Masonic

law practice and tracing its origin to Prince Hall, the first

Negro Mason in America (E. 53-62).

Petitioner was first organized about the year 1917 at

or near Opelika, Alabama, when a group of about six to

eight persons, said to he Master Masons, met and organ

ized (E. 617, 1177). In 1921, petitioner was incorporated

in the State of Alabama, receiving a charter from a court

of competent jurisdiction for the County of Jefferson

under the name “ Free and Accepted Colored Masons of

America” (E. 642-643, 1177). In 1924 delegates from a

few subordinate lodges in Alabama and Georgia formed a

Supreme Grand Lodge and J. B. Baldwin was elected

Supreme Grand Master (E. 615-616, 1178). In 1945, by

amendment to its charter, the name of petitioner was

changed to “ Supreme Grand Lodge, Modern Free and

Accepted Colored Masons of the W orld” (E. 649).

Petitioner made no attempt to prove that it had received

any warrant or authority from any duly constituted

Masonic group. In fact, the Grand Master of petitioner

admitted lack of any such authority (E. 743). Eather,

petitioner sought to cast a cloud upon respondent’s legit

imacy.

An expert witness offered by petitioner testified that

certain grand lodges of Negro Masons participated in or

acquiesced in the formation of a National Compact about

the year 1847 (E. 490-494). This Compact formed by rep

resentatives of those grand lodges as a national supreme

body asserted supremacy over the state grand lodges. It

5

is admitted by all experts testifying that such a compact

was formed (R. 490-494, 848). Respondent’s expert wit

ness testified that said National Compact was found to be

contrary to Masonic law and practice and was formally

dissolved in 1877 (R. 247-248, 279, 256). Petitioner’s ex

pert, on the other hand, claimed that said National Com

pact was legitimate and persisted after 1877 (R. 494-495,

590-591). This expert also claimed that respondent can

trace its origin only to certain rebellious lodges which were

expelled from the National Compact about 1877 and that

respondent is therefore not a regular Masonic body

(R. 811). These claims, however, are refuted by respond

ent’s expert witness, Masonic treatises and historical

materials which demonstrate that respondent is the regu

lar and legitimate body of Negro Masons organized in con

formance with Masonic law (R. 247-248, 279, 587-592).

There was also evidence that the activities of petitioner

were not conducted in accordance with Masonic law and

tradition (R. 84, 683-689, 721-731, 743-744, 747-750, 795-

831). The fraternal aspects of petitioner were subor

dinated to the business of providing insurance and burial

aid, activities highly remunerative to petitioner’s officers.

The evidence also showed that petitioner is a one-man

enterprise, controlled by J. R. Baldwin, its Supreme Grand

Master, who has utilized the organization to enhance his

undertaking and casket business (R. 655, 659-665, 674, 683-

689, 710, 721-731, 747-748, 757, 795-806, 828-831).

The Unfair Competition

Both petitioner and respondent use as the distinctive

part of their names (R. 285) the words “ Free and Ac

cepted” and the word “ Masons” . Further, respondent’s

evidence, not denied by petitioner, indicates that both par

ties use the same signs, grips, password, emblems, badges

etc. (R. 340, 362, 378). There is abundant evidence to the

6

effect that officers and agents of petitioner actively soli

cited new member who were invariably told that petitioner

was an order of “ Free and Accepted Masons” , that all

Masonic lodges were the same, except that petitioner did

more for its members, and that petitioner was world-wide

(E. 339, 359, 384-385, 405, 419, 422, 422-443). Petitioner’s

officers, in addition, assured prospective members that peti

tioner used the same grips, signs, etc. used by every other

Masonic lodge (R. 419, 711-712, 751). In fact, one of peti

tioner’s subordinate lodges actually uses the term “ Prince

Hall” as a part of its name (R. 715).

There is also considerable evidence that the similarity

in name and ritual resulted in injury to respondent and

confusion to the public. Several witnesses testified that

they thought that petitioner and respondent were one and

the same body (R. 371-375, 385-386, 401-402, 418-419, 419-

422, 446). A number of persons were thereby misled into

joining petitioner. There was like testimony indicating

that the similarity in names resulted in confusion in the

receipt of mail (R. 469, 980-982). Furthermore, there was

evidence that petitioner had even usurped respondent’s

physical premises. For example, one of petitioner’s sub

ordinate lodges assumed control over the furniture and

Masonic tools belonging to respondent, and members of

petitioner’s lodge drove respondent’s members out of their

own meeting place (R. 355-357).

Findings and Judgment of the District Court

After a trial without a jury, the District Court found

as a fact that respondent and its legitimate predecessors

have had a favorable and continuous existence in America

since about 1776, and a continuous existence in the State

of Georgia since a date immediately following the end of

the Civil War (R. 1175). The trial court further found

that petitioner came into existence in the State of Alabama

in 1917 and that according to Masonic jurisprudence peti-

7

tioner is not regularly and lawfully organized (ft. 1177,

1181). The court described petitioner as “ almost if not

completely dominated and controlled by J. B. Baldwin,

its Supreme Grand Master of its Supreme Grand Lodge” ,

and concluded that the interest of petitioner was largely in

insurance and burial aid which it furnishes its members

at considerable profit to its officers (ft, 1179-1180). On

the basis of its history, the fact that it is largely a one-

man institution and the fact that the insurance and burial

aspects predominated, the District Court concluded that

petitioner is not an authenic Masonic organization, but is

spurious and illegitimate (R. 1181-1182). Finally, the

court concluded that the adoption by petitioner of the

words “ Free and Accepted” , which are the distinctive

features of respondent, was done by petitioner with the

intent to deceive and defraud the public and reap the benefit

of respondent’s good will to the injury of respondent and

to the confusion of the public (R. 1181). Accordingly, on

January 2, 1952, judgment was entered enjoining peti

tioner from using the words “ Free and Accepted” and

from using the ritual and ceremonies of respondent

(R. 1184-1185). Subsequently, the District Court denied

petitioner’s motion for a new trial and at the same time

amended its judgment so as to restrain petitioner from

using the words “ Free and Accepted Masons” or

“ Masons” (R. 1190-1191). The Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit affirmed on January 6, 1954, Chief Judge

Hutcheson concurring in part and dissenting in part

(R. 1226-1232).

8

ARGUM ENT

I. The petition fails to comply with Rule 38 (2)

of this Court.

The petition fails to state any question conforming with

the requirement of Rule 38 (2) of this Court. The peti

tion should accordingly be denied. See United States v.

Rimer, 220 U. S. 547, and other cases cited in Rule 38(2).

II. The petition neither presents a federal question

nor does it raise any important question of local law

decided in a way probably in conflict with applicable

local decisions.

This is an unfair competition action in which federal

jurisdiction is based solely on diversity of jurisdiction.

No federal question is presented1 nor does this case in

volve any conflict between decisions of Courts of Appeal.

No important question of local law is involved. Further

more, the questions of local law decided below are clearly

in accord with Georgia decisions.

There is no merit in petitioner’s assertion that the deci

sion of the Court of Appeals is in conflict with the rule of

Erie Railroad Co. v. Tompkins, 304 U. S. 64. Petitioner

has indeed strained very hard to find a federal question

in this record. Respondent agrees that the Georgia law of

unfair competition is applicable and that under that law

it is necessary to prove an intent to deceive or mislead the

public. Atlanta Paper Co. v. Jacksonville Paper Co.,

184 Ga. 205, 190 S. E. 777 (1937). But it is clear that both

the District Court and the Court of Appeals properly

1 Unlike Ancient Egyptian Arabic Order N. M. S. v. Michaux,

279 U. S. 737, and Creswill v. Grand Lodge, Knights of Pythias of

Georgia, 225 U. S. 246, petitioner here is not incorporated pursuant

to Act of Congress.

9

applied Georgia law. In its finding of fact No. 31, the

trial court found as follows:

“ 31. I find that the adoption by the defendant of

the words ‘ Free and Accepted’, which are the dis

tinctive features of the plaintiff, was done by the

defendant with the intent to deceive and defraud the

public and reap the benefit of plaintiff’s good will,

to the injury and damage of the plaintiff, and to the

confusion of the public” (R. 1181).

In affirming, the Court of Appeals declared:

“ The finding of the trial court that appellant’s

adoption of the infringing words as a part of its

name was done with intent to deceive and defraud

the public is well supported by the evidence *’ * * ”

(R. 1228).

Thus, the real thrust of petitioner’s argument is not

that the court below violated the rule of Erie Railroad Co.

v. Tompkins by refusing to apply state law, but merely

that the court below applied Georgia law badly in the sense

that the finding that petitioner intended to mislead is not

supported by the evidence. Thus rephrased, petitioner’s

contention raises no federal question at all, unless every

challenge to the sufficiency of the evidence in support of

the application of proper state law in diversity cases can

be denominated a federal question.

Petitioner’s reliance upon the decision in Atlanta

Paper Co. v. Jacksonville Paper Co., supra, as repudiating

prior Georgia decisions and changing the Georgia unfair

competition law is plainly misplaced. In fact, the Georgia

Supreme Court in Atlanta Paper cites with approval most

of the cases which petitioner states were overruled. 184

Ga. at 211, 190 S. E. at 782. The opinion in the Atlanta

Paper case sums up the applicable Georgia law in these

10

words at pages 212-213 and 782-783 of the official and

regional reports, respectively:

“ It [unfair competition] consists in passing off, or

attempting to pass off, on the public, the goods or

business of one person as and for the goods and

business of another. It consists essentially in the

conduct of a trade or business in such a manner that

there is either an express or implied representation

to that effect. In fact, it may be stated broadly that

any conduct, the nature and 'probably tendency and

effect of which is to deceive the public so as to pass

off the goods or business of one person as and for

the goods and business of another, constitutes action

able unfair competition.” (Emphasis added.)

Thus, while Georgia law requires proof of an intent to

deceive, this can be proved by circumstantial evidence.

Conduct, the natural and probable tendency of which is

to deceive the public, is strong circumstantial evidence

tending to prove the requisite intent.

There is in fact abundant evidence in the record in

support of the District Court’s finding that petitioner in

tended to deceive and mislead the public. Under the rule

of Creswill v. Grand Lodge Knights of Pythias of Georgia,

133 Ga. 837, 67 S. E. 188 (1910), rev. ot. gnds., 225 U. S.

246, the mere appropriation and use by petitioner of

respondent’s name where respondent has a clear right to

its use is presumed fraudulent and alone can supply the

necessary intent. But the evidence here is much more

damaging. The evidence (as already set forth in the state

ment of the case) shows repeated attempts on the part of

petitioner’s officer to solicit members by representing that

petitioner, like respondent, was a body of “ Free and

Accepted Masons” and that it used the same ritual as

respondent and other authentic Masonic groups. There is

likewise abundant evidence of resulting confusion. On all

1 1

the evidence, the conclusion is inescapable that petitioner,

a group not formed in accordance with Masonic law and

practice, appropriated the distinctive words which identify

all legitimate Masonic orders, and conducted its activities

with a clear intent to deceive and mislead the public.

The other points raised in the petition likewise present

a challenge to the sufficiency of the evidence. For reasons

already indicated, they do not raise any question meriting

the grant of certiorari. Moreover, respondent submits

that the evidence, as summarized earlier, clearly supports

the findings of fact, conclusions of law and the full sweep

of the injunctive relief granted by the courts below.

W herefore, it is respectfully submitted that this peti

tion for a writ of certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

T hurgood Marshall,

A mos T. Hall,

Counsel for Respondent.

April 15th, 1954.