Ephraim v. Safeway Trails, Inc. Plaintiff-Appellee's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Ephraim v. Safeway Trails, Inc. Plaintiff-Appellee's Brief, 1964. 4a1f63ed-b09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/24eae618-d267-48de-acf9-72fb0c5c01c2/ephraim-v-safeway-trails-inc-plaintiff-appellees-brief. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

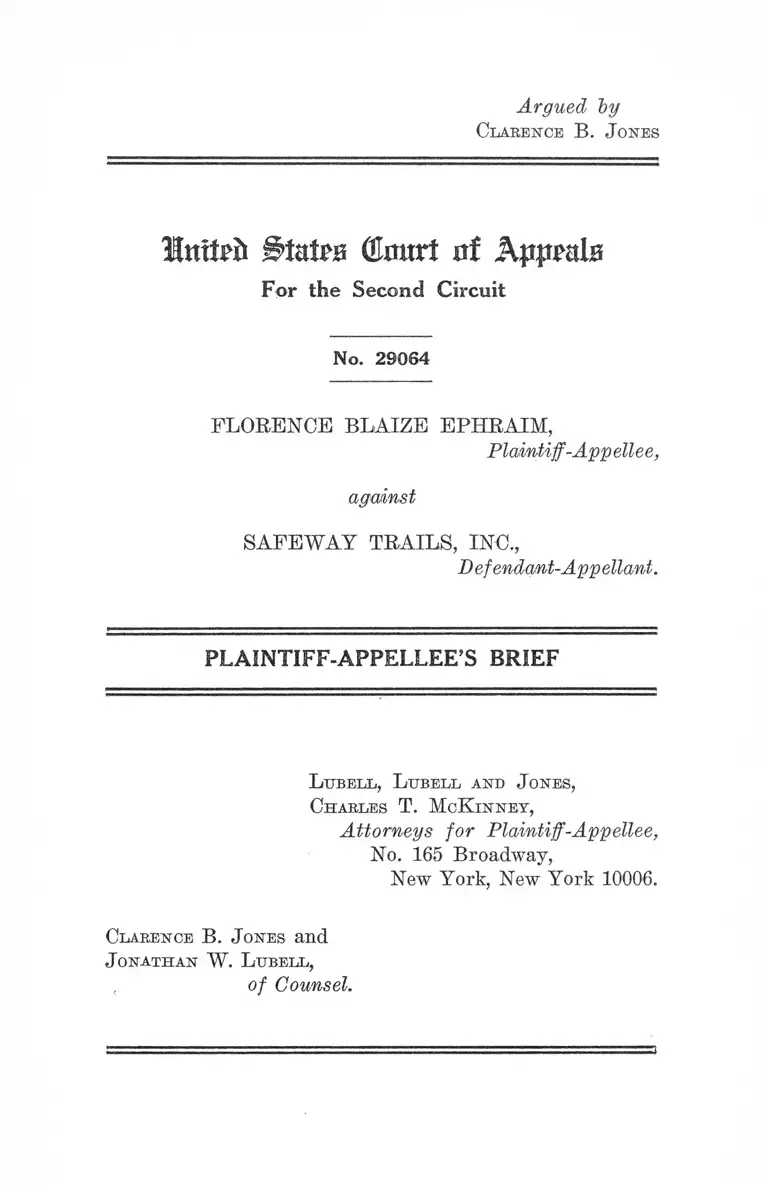

Argued by

Clarence B. J ones

ImM BtuUB Olmtrt nf

For the Second Circuit

No. 29064

FLORENCE BLAIZE EPHRAIM,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

against

SAFEW AY TRAILS, INC.,

Defendant-Appellant.

PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE’S BRIEF

L ttbell, L ijbell and J ones,

Charles T. M cK in n e y ,

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee,

No. 165 Broadway,

New York, New York 10006.

Clarence B. J ones and

J on athan W. L ubell ,

, of Counsel.

I N D E X

Preliminary Statement ................................................. 1

P oint I—Amendments to the Interstate Commerce

Act pursuant to which Congress assumed control

of the transportation of passengers by motor car

riers engaged in interstate commerce and the regu

lation of such transportation do not deprive motor

carriers thereunder of the power to enter into spe

cial contracts for the transportation of passengers

over connecting carriers ........................................... 2

P oint II— The limitation of liability included in

tariffs filed by appellant and on back of the ticket

issued by it to appellee does not preclude appellant

PAGE

from incurring liability to appellee ...................... 4

P oint III—Appellant is liable for the injuries sus

tained by appellee while travelling on the line of

Southern Stages ......................................................... 8

A. Where A Special Contract Arises Between A

Passenger and Initial Carrier, Subsequent

Connecting Carriers Operate as Agents of

The Initial Carrier in Carrying Out Its En

gagement to Transport Passenger to The

Ticketed Destination ....................................... 8

B. The Undisputed Record Facts Below Estab

lish the Existence of a Special Contract

Whereby Appellant Undertook to Trans

port Appellee by Motor Bus Over its Own

Lines and Those of Connecting Carriers From

New York to Montgomery, Alabama .......... 9

C. Where Special Contract Is Established, Ap

pellant, As Principal, is Liable for Failure of

Connecting Carrier to Exercise Required

Care in Transporting Appellee Pursuant to

said C ontract..................................................... H

P oint IV— Contrary to appellant’s contention, the

Court below did not err in holding that the rule

laid dowTn in Louisville & Nashville E.E. Co. v.

Chatters is inapplicable to the circumstances of this

case .............................................................................. 12

A. None of the Cases Eecited by Appellant in

“ Point I I I ” of its Argument Exempt Ap

pellant From Eesponsibility For the In

juries and Damages Sustained by Appellee 12

B. Appellant Was the Eecipient of Economic or

Financial Benefits From Proceeds Derived

From the Transportation of Appellee Over

the Lines of Connecting C arriers................ 17

P oint V—Appellant is liable for the acts of the police

officer and for the act of the driver in calling the

police officer and identifying appellee ................ 20

A. Motor Carriers of Passengers Must Exercise

Extraordinary Care and Diligence for Safety

of Their Passengers ....................................... 20

B. That the Injuries Sustained by Appellee Be-

sulted Partially From Acts Committed by an

Officer of the Law Does Not Absolve Appel

lant From L iab ility ......................................... 22

Conclusion........................................................................ 25

Cases Cited

Battle v. Central Greyhound Lines, Inc. of New York,

Buffalo, 171 Misc. 517,13 N. Y. S. 2d 357, 358 (Sup.

Ct.) ................................................................................ 11

Boynton v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 364 U. S. 454,

460-461 ........................................................................ 16

Brunswick v. Western E. E. Co. v. Ponder, 117 Ga. 63 24

Buffett v. Troy and Boston Eailroad Co., 40 N. Y.

168, 172-173 ................................................................. 11

i i

PAGE

Ill

Bullock v. Tamiami Trail Tours, Inc., 266 F. 2d 326

(5th Cir.) ..................................................................... 22

Condict v. Grand Truck Railway Co., 54 N. Y. 500,

502-503 .......................................................................... 5,11

Conklin v. Canadian-Colonial Airways, Inc., 266 N. Y.

244, 247 ................................................................. g

Cray v. Greyhound Lines, 110 A. 2d 892, 177 Pa.

Super. 275 at p. 895 ........................ 2,5

Glaser v. Penn R. R., 196 A. 2d 539, 82 N. J. Super.

16 ................................................................................... 2,13

Green Bus Lines, Inc. v. Ocean Acc. and Guarantee

Corp., 287 N. Y. 309, 312 ............................................. 21

Gregory v. Elmira Water Light & R. Co., 190 N. Y.

363 ................................................................................. 20

Greyhound Corporation v. Ault, 238 F. 2d 198, 201

(5th Cir.) ..................................................................... 20

Griffen v. Manice, 166 N. Y. 188 .................................... 20

Kinchlow v. People’s Rapid Transit Co., et al., 88

Fed. 2d 764 (C. C. A. D.) c. d. 57 Sup. Ct. 726 .. 23

Louisville & Nashville R. R. Co. v. Chatters, 279

u ; S. 320 ......................................................................2,4,12

Louisville Railroad Company v. Webb, 248 S. W.

2d 429 (Ct. of App. Ky.) ......................................... 13

Matthews v. Southern Ry. System, 157 F. 2d 609, 610-

11 (D. C. Cir.) ............................................................. 22

Mitchell v. L. E. & W. R. Co., 146 U. S. 5 1 3 .............. 20

Morrison v. Pennsylvania Railroad Company, Vol. 6

C. C. H. Fed. Carriers Cases Par. 80370, p. 2013

(U. S. D. C., S. D. N. Y.) ......................................... 13

New York Central R. R. Co. v. Lockwood, 17 Wall.

(84 U. S.) 357 ............................................................. g

Northern Pacific Railway Co. v. American Trading

Company, 195 U. S. 439, 459 ................................. 11

Penn. R. R. Co. v. Jones, 155 U. S. 333 ...................... 5

PAGE

IV

Quimby v. Vanderbilt, 17 N. Y. 306 ......................... 5,11

Railroad Company v. Pratt, 82 U. S. (22 Wall.) 123,

1 3 2 -1 3 3 ........... ............. ............................................... 11

Schmidt v. Randall, 160 F. Supp. 288, 230 (D. C.

Minn.) .......................................................................... 19

Scholwin case, 70 S. E. 2d 292, 86 Ga. App. 99 . . . . 24

Solomon v. Pennsylvania Railroad Company, 96 P.

Supp. 709 (S. D. N. Y.) ............................... ‘ ............ 13

Spears v. Transcontinental Bus System, 226 F. 2d

94 (9th Cir.) cert den., 350 U. S. 950, reh. den. 350

U. S. 977 ....................................................................... 13

Talcott v. Wabash R. Co., 159 N. Y. 461, 472-473 . . . 5

Tompkins v. Missouri K & T Ry. Co., 211 Fed. 391

(C. C. A. 8th Cir.) ....................................................... 23

Wooten v. Pennsylvania Railroad Co., 288 P. 2d 220,

224 (7th Cir.) cert, den., 368 U. S. 819 .............. 7,14

Statutes Cited

Pair Labor Standards Act (29 U. S. C. Sec. 213(a)

(2)) .............................................................................. 19

Georgia Code, Section 105-202 ..................................... 21

Sec. 1(18) of 49 IT. S. C................................................... 3

PAGE

Ittitpft §tat£H (Emtrl nf Appals

For the Second Circuit

No. 29064

---------------------- o-----------------------

F lorence B laize E p h r a im ,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

against

S afew ay T rails, I n c .,

Defendant-Appellant.

-----------------------o-----------------------

PLAINTIFF-APPELLEE’S BRIEF

Preliminary Statement

The ease presented to the court by the facts of the

present controversy involve the simple question of whether

or not defendant-appellant (hereinafter referred to as

“ appellant” ), an initial carrier, having entered into a

special contract to transport plaintiff-appellee (herein

after referred to as “ appellee” ), over its own lines and

those of connecting carriers, on a round-trip journey from

New York to Montgomery, Alabama, is exempt from lia

bility for injuries sustained by appellee, by reason of

affirmative negligence and wrongful acts of appellant’s

agents, Southern Stages, Inc., a connecting carrier. Con

trary to the specious assertions of appellant, the correct

decision of the court below, on the basis of the evidence

adduced at the trial and the controlling principles of law

relating thereto, does not contravene the national policy

of the Interstate Commerce Act or challenge the pro

cedures, practices and regulations of the Interstate Com

merce Commission.

2

P O I N T I

Amendments to the Interstate Commerce A ct pur

suant to which Congress assumed control o f the trans

portation o f passengers by m otor carriers engaged in

interstate com merce and the regulation o f such trans

portation do not deprive motor carriers thereunder of

the power to enter into special contracts for the trans

portation o f passengers over connecting carriers.

Appellee does not challenge any of the provisions of

the Interstate Commerce Act cited on pages iii to xvi of

appellant’s brief, nor does appellee challenge the deci

sions in the cases cited on pages 11 and 12 of appellant’s

brief. Appellee respectfully submits, however, that

neither the statutory provisions of the Interstate Com

merce Commission Act, cited by appellant, nor the cases

of Glaser v. Perm R.R., 196 A. 2d 539, 82 N. J. Super. 16,

and other cases cited by it, or Cray v. Greyhound Line, 110

A. 2d 892, 177 Pa. Super. 275 at p. 895, are applicable,

controlling or determinative of the simple question pre

sented to this court on appeal.

'The Glaser case, supra, insofar as it relates to the lia

bility of an initial carrier to a passenger for injuries

sustained on a connecting carrier, adds nothing new to

this question different from Louisville & Nashville R. R.

Co. v. Chatters, 279 U. S. 320. While the Glaser decision,

supra, discussed the underlying purposes of the ICC in

the promotion of a uniform system of transportation,

nothing in the court’s opinion (or in the Chatters case,

supra, upon which the opinion was based) prohibited or

deprived an initial carrier of the power to incur liability

by reason of a special contract with a passenger under

taking or assuming responsibility for such passengers

through transportation over connecting lines.

3

On page 11 of its brief, appellant cites excerpts from

the decision in the Glaser case, supra, on page 542 of the

court’s opinion therein. The excerpt quoted said:

“ Under the Interstate Commerce Act (I. C. A.)

no carrier by railroad may either extend or aban

don its line or any part thereof except on the basis

of a permissive order of the I.C.C. after notice and

hearing. 49 U. S. C. Sec. 1(18). There are severe

penalties for violation. 49 U. S. C. Sec. 1(20).”

(Emphasis added.)

Appellant would like this court to believe that the

quoted excerpt from the opinion of the court in Glaser,

supra, and the reference to the statutory provisions of the

I. C. A. therein prohibited appellant as an initial carrier

from engaging to transport appellee beyond the physical

extent of its own franchised lines. However, Sec. 1(18)

of 49 U. S. C. refers to the physical extension of a carrier’s

line by construction of a new line or physical facility or

means of transportation without obtaining a “ permissive

order” of the I. 0. C. Sec. 1 of Title 49 U. S. C. provides:

“ 1. par. (18). Extension or abandonment of

lines; certificate required; contracts for joint use

of spurs, switches, etc. No carrier by railroad

subject to this chapter shall undertake the exten

sion of its line of railroad, or the construction of a

new line of railroad, or shall acquire or operate

any line_ of railroad, or extension thereof, or shall

engage in transportation under this chapter over

or by means of such additional or extended line of

railroad, unless and until there shall first have been

obtained from the Commission a certificate that the

present or future public convenience and necessity

require or will require the construction, or opera

tion, or construction and operation, of such addi

tional or extended line of railroad, and no carrier

by railroad subject to this chapter shall abandon all

or any portion of a line of railroad, or the operation

thereof, unless and until there shall first have been

4

obtained from the Commission a certificate that the

present or future public convenience and necessity

permit of such abandonment * *

The underlying purpose of the above quoted section

is to prevent improvident and unnecessary expenditures

for the construction and operation of lines needed to in

sure adequate service and to protect interstate carriers

from weakening themselves in the physical construction

and operation of superfluous lines. The national trans

portation policy of the United States and the Interstate

Commerce Act, do not preclude or prohibit an initial car

rier from entering into a special contract with a passenger

for transportation over the lines of a connecting carrier.

Such a contract does not, as appellant apparently sug’-

gests, amount to an extension of the lines of transporta

tion of appellant as the initial carrier.

P O I N T I I

The limitation o f liability included in tariffs filed

by appellant and on back o f the ticket issued by it to

appellee does not preclude appellant from incurring

liability to appellee.

Appellant’s contention that the “ Limitation Printed

on the Ticket Would Alone Constitute a Contract Binding-

on Both Carrier and Passenger” (App. Br., p. 13 *) is a

distorted application of legal principles set forth in other

cases controlled by facts which are wholly inapposite to

the case at bar. Accordingly, the citation of the Louisville

* “ App. Br.” refers to appellant’s brief and page numbers thereto.

Numbers in parentheses followed by the letter “a” refer to pages

of the Appendix to Brief of Defendant-Appellant.

5

& Nashville Ry. Co. v. Chatters, 279 U. S. 320; Cray v.

Penn Greyhound Lines, 110 A. 2d 892, 177 Pa. Super. 275;

Penn. RR Co. v. Jones, 155 U. S. 333 (App. Br., p. 13)

cases in support of appellant’s “ Point I I ” are not au

thority for exempting appellant from liability to appellee.

Where a special contract arises between a passenger

and an initial carrier (see Point III, infra), the “ limita

tion of liability” included in tariffs filed by it with the

Interstate Commerce Commission and appearing on the

back of a ticket does not absolve the carrier from lia

bility for injuries to a passenger sustained while traveling

over the lines of a connecting carrier. Talcott v. Wabash

R. Co., 159 1ST. Y. 461, 472-473; Condict v. Grand, Truck

Railway Co., 54 N. Y. 500, 502-503; Quimby v. Vanderbilt,

17 N. Y. 306.

Neither the “ limitation of liability” on appellant’s

tickets nor the provisions of subparagraph (4), Rule 6 in

Section A3 of appellant’s Exhibit C (167a) placed it

under a legal disability to enter into a special contract of

transportation with appellee. Condict v. Grand Truck

Railway Co., supra; Quimby v. Vanderbilt, supra, at page

313 of 17 N. Y. Appellant had the power to contract with

appellee for through transportation to Montgomery, Ala

bama. “ An owner of one of several lines for transporta

tion of passengers running in connection over different

portions of a route of travel may contract as principal for

the conveyance of a passenger over the whole route. Such

contract may he established by the circumstances notwith

standing the passenger received tickets for different lines

signed by their separate agents.” Talcott v. Wabash R.

Co., supra, at 472-473 of 159 N. Y. (Emphasis added.)

The Court in the Wabash case, supra, said at p. 474:

“ Upon all the evidence we think it became a

question of fact whether the contract was for

through transportation or not * * (emphasis

added)

6

The statements appearing on the back of the ticket

and contained in the tariff are not determinative of the

relationship arising between appellant, appellee and sub

sequent connecting carriers. Such statements are merely

some evidence, susceptible to rebuttal by appellee’s proof ad

duced at the trial below of facts unequivocally establishing

that appellant in issuing its ticket acted as principal and,

as such, did in fact, pursuant to its special contract (see

Points III, IY, infra) with appellee, assume responsibility

for her transportation over the connecting lines of its

agents.

Both the statement on the back of the ticket and the

provision in the tariff limit the responsibility of the selling

carrier where the circumstances involve only the selling

of the ticket and the checking of the baggage. Where fur

ther facts are found which show that the initial carrier

was acting as principal in the transportation of the pas

senger to her destination, then, the limitation of respon

sibility to its own line arising from the initial carrier’s

mere sale of the ticket and checking baggage plainly does

not apply. This is precisely the situation found by the

Trial Court below.

Each stub of the ticket issued by appellant expressly

stated that it was for the account of appellant. Appellant

received 10% of the proceeds derived from the transpor

tation of appellee over connecting lines of other carriers

(132a-140a, 143a-146a). In addition to these factors, the

evidence adduced at the trial established that appellant

made representations to appellee, express and implied,

at the time the ticket was issued to her (159a, 25a); that it

had undertaken the responsibility of transporting appellee

to her ticketed destination (24a, 28a) ; and that under the

then prevailing circumstances appellee reasonably relied

upon said representation. In short, it is the totality of

7-

these additional facts, not the mere issuance or sale of the

ticket by appellant which results in appellant’s becoming

the principal in the engagement to transport appellee to

Montgomery, Alabama, These factors, arising from all the

surrounding circumstances, rendered inapplicable the lim

itation of liability on the back of appellant’s ticket and in

the tariff regulations filed with the Interstate Commerce

Commission.

After weighing all the facts and surrounding circum

stances the Trial Court found:

“ Under the circumstances of the present ease,

however, it is the opinion of this court that although

the exculpatory declarations on the back of the

tickets, as well as Rule 6(4) of the tariff, would apply

where there is a mere sale of the ticket, there are

other factors present here, in addition to a mere sale

of a ticket, which render this defendant liable.

“ # '* * [T]he totality of these additional factors

result in the defendant in this case becoming the

principal in the engagement to transport plaintiff

to Montgomery, Alabama, and render the disclaimers

inoperative to exempt defendant from liability.”

(p. 15a)

Similarly, in Wooten v. Pennsylvania Railroad Co., 288

F. 2d 220, 224 (7th Cir.) cert, den., 368 U. S. 819, where the

ticket stated “ not responsible beyond its line * * *” and

defendant’s tariffs provided that “ * * * the issuing carriers

act only as agents and are not responsible beyond their own

lines * * * ” , the Court held:

“ I f the jury was convinced that the alleged negli

gence existed and could be imputed to defendant,

then defendant’s disclaimer of liability printed on the

ticket and in the tariff could not absolve it from lia

bility occurring beyond its own line #

The decision of the trial court is in accord with the

principle that limitations of liability must be strictly con

8

strued. The public policy and law of the State of New York

is against the legality of common carriers absolutely ex

empting themselves from liability for negligence in the

carriage of goods or persons. New York Central R. R. Co.

v. Lockwood, 17 Wall. (84 U. S.) 357; Conklin v. Canadian-

Colonial Airways, Inc., 266 N. Y. 244, 247.

Furthermore, the disclaimer contained in subparagraph

(4) of Rule 6 in Section A3 of the tariff regulations herein

before described merely states that in issuing tickets and

checking baggage the “ issuing carrier” acts only as agent

and does not have responsibility for transportation over the

lines of other carriers. The self-serving declination or dis

claimer of responsibility ‘ ‘ for transportation over the lines

of other carriers” (emphasis added) does not on its face

immunize appellant from liability for personal injuries

sustained by a passenger by reason of affirmative wrongful

acts by a connecting carrier from whom appellant receives

10% of the cost (see Point IV infra) charged to appellee for

transportation of such connecting carrier.

P O I N T I I I

Appellant is liable for the injuries sustained by

appellee while travelling on the line o f Southern Stages.

A . W here A Special Contract Arises Between A

Passenger and Initial Carrier, Subsequent Con

necting Carriers Operate as Agents o f The

Initial Carrier in Carrying Out Its Engagement

to Transport Passenger to The Ticketed Des

tination.

Appellant’s assertion that it acted merely as “ agent”

for the sale of tickets over the lines of connecting carriers

which appellee was required to travel, in order to reach her

destination, is contrary to the undisputed record now

before this court. That “ it did not own, lease, operate”

(see p. 15 App. Br.) or directly control the physical opera

9

tion of the bus in -which appellee was travelling, when'

affirmative wrongful acts were committed against her per

son, does not insulate appellant from liability. Similarly,

although appellant may have been required, under the Rules

and Regulations of the Interstate Commerce Commission,

to sell tickets for travel over connecting lines, the existence

of such Rules and Regulations neither deprive appellant of

the potver to incur liability for through transportation by

way of special contract, nor does it exempt appellant from

responsibility for wrongful acts against appellee occurring

on connecting lines.

B. The Undisputed Record Facts Below Establish

the Existence o f a Special Contract W hereby

Appellant Undertook to Transport A ppellee

by Motor Bus Over its Own Lines and Those o f

Connecting Carriers From New Y ork to Mont

gomery, Alabam a.

On July 31, 1959, appellee purchased from appellant at

its ticket booth in the Port Authority Building Bus Ter

minal, in New York City, a round trip ticket for transporta

tion by motor bus (24a and 25a). Appellee paid appellant

the full fare for the entire round trip journey (26a).

The argument of appellant set forth in support of its

“ Point I I I ” and the cases recited thereunder, as authority

for appellant’s argument are, at best, relevant to facts

other than those adduced by appellee in support of her case

below. The record facts show that appellant did more

than merely issue tickets to appellee. The sale of tickets

and appellee’s payment therefor is merely one factor out of

a totality of factors creating a special contract between

appellant and appellee.

Appellant made express and implied representations to

appellee that it had undertaken her round trip bus trans

portation from New York City to Montgomery, Alabama.

Printed upon each of the thirteen segments of the round

trip ticket issued to appellee by appellant was a legend

10

denoting that the origin of the trip was ‘ ‘ New York, New

York” and the destination “ Montgomery, Alabama”

(159a). Upon the face of each stub was printed the nota

tion that the ticket was issued “ for the account of (S .)” ;

on the reverse side of each ticket “ (S .)” was defined as

“ Safeway Trails, Inc.” , the appellant herein (159a).

Appellee, who came to the United States for the first

time in December of 1951 (23a) had never travelled or been

to the southern part of our United States prior to August

of 1959. As a West Indian Negro, she was concerned that

the purchase of her round trip ticket from appellant and the

reservation made concurrent therewith entitled her to a seat

throughout the entire course of her round trip journey. This

court may take judicial notice of the existence, in August

1959, of racially discriminatory practices in the Southern

States through which appellee was required to travel. Ap

pellee wanted assurances of her reservation while travel

ling pursuant, to the ticket issued to her and, consequently,

specifically asked appellant’s employee whether or not she

could be assured of a seat during the course of her journey

(25a). The fact that the reservation slip (Def. Ex. 163a,

159a) reserved to appellee a seat only as far as Raleigh,

North Carolina, where a change of bus was scheduled, does

not lessen the legal weight to be accorded the representa

tions of appellant’s employee at the ticket window, and

appellee’s reliance thereupon. The undisputed record fact

is that appellee reasonably relied upon the express and

implied representations of appellant that it had undertaken

to transport her to her desired destination (27a, 28a).

Contrary to appellant’s assertion, appellee did not as

sert at the trial below nor does she do so herein that such

representations constituted appellant an insurer or guaran

tor of safe passage for appellee throughout the entire trip.

It is respectfully submitted, however, that these representa

tions, appellee’s reliance thereon, the notations and legend

on the ticket and the receipt of monies by appellant in the

11

form of a commission (132a-140a, 143a-146a and Point IV

infra) created a special contract between appellee and ap

pellant.

Railroad Company v. Pratt, 82 U. S'. (22 Wall.)

123, 132-133;

Quimby v. Vanderbilt, 17 N. Y. 306;

Condict v. Grand Trunk Railway Co., 54 N. Y. 500,

502-503;

Northern Pacific Railway Co. v. American Trading

Company, 195 U. S. 439, 459;

Battle v. Central Greyhound Lines, Inc. of New

York, Buffalo, 171 Misc. 517, 13 N. Y. 8, 2d 357,

358 (Sup. Ct.).

C. W here Special Contract Is Established, A p

pellant, As Principal, is Liable for Failure o f

Connecting Carrier to Exercise Required Care

in Transporting A ppellee Pursuant to said Con

tract.

Under well established principles of respondeat su

perior, appellant, where a special contract arises between

it and appellee, is liable for breaches of duty, wrongful acts

and failure of its agent, a subsequent connecting carrier,

to exercise the standard of care required under the cir

cumstances in carrying out appellant’s contract with appel

lee to transport her to her destination of Montgomery,

Alabama. Buffett v. Troy and Boston Railroad Co., 40

N. Y. 168, 172-173.

12

P O I N T I V

Contrary to appellant’s contention, the Court be

low did not err in holding that the rule laid down in

Louisville & Nashville R.R. Co. v. Chatters is inappli

cable to the circumstances o f this case.

A. None o f the Cases Recited by Appellant in

“ POINT III” o f its Argument Exempt A ppel

lant From Responsibility For the Injuries and

Damages Sustained by Appellee.

The principles of law of the cases set forth in appel

lant’s brief on pages 15 through 20 are neither controlling

nor determinative on the question of whether or not appel

lant incurred any liability to appellee for injuries she sus

tained while travelling on the connecting line of Southern

Stages Inc. None of the cases involved affirmative acts of

negligence or intentional wrongs to the plaintiffs therein.

None precluded an initial carrier from having the power

of incurring liability by way of special contract for

personal injuries sustained by a passenger travelling, pur

suant to a ticket issued by the initial carrier, on lines of

a connecting carrier. None involved a ticket issued by an

initial carrier hearing a legend indicating that each stub

for every part of the trip was issued for its “ own account” .

None of the cases involved the existence of affirmative

proof at the trials thereof of any tangible financial and/or

economic benefit accruing to the initial carrier from the

sale of tickets for travel over the lines of other connecting

carriers.

Appellant, in its brief, says that the case of Louisville

& Nashville Railroad Company v. Chatters, supra, is “ on

all fours with the case before this court except that the

nature of the tort is different” (App. Br., p. 16). Appellee

has no quarrel with appellant’s recitation of the facts of

the Chatters case. Nor does appellee challeng-e the holding

13

of that case as applied to the facts therein. The Chatters

case, however is not “ on all fours” with the facts and

circumstances of the case at bar. Chatters involved the

question of whether or not liability was incurred by an

initial carrier for injuries sustained by a passenger while

traveling over the lines of a connecting carrier, pursuant

to the mere purchase of a round trip ticket from the

initial carrier. The only similarity between the Chatters

case and the facts and circumstances adduced at the trial

herein are: (1) the sale of a round trip ticket by the initial

carrier; (2) the limitation of liability appearing on the

ticket, and (3) the injuries sustained by the plaintiff

therein occurred on the lines of a connecting carrier.

Neither the reported record facts in the Chatters case nor

the court’s opinion is controlling’ where a special contract

arises between a passeng’er and the initial carrier.

Neither in Chatters, supra, nor Glaser v. Pennsylvania

Railroad Company, 196 A. 2d 539, 82 N. J. Super. 16;

Spears v. Transcontinental Bus System, 226 F. 2d 94

(9th Cir.), cert. den. 350' U. S. 950, reh. den. 350 U. S'.

977); Morrison v. Pennsylvania Railroad Company, Yol.

6 C. C. H. Fed. Carriers Cases Par. 80370, p. 2013 (U. S.

D. C., S. D. N. Y .) ; Solomon v. Pennsylvania Railroad Com-

pany, 96 F. Supp. 709 (S. I). N. Y.) nor in Louisville Rail

road Company v. Webb, 248 S. W. 2d 429 (Ct. of App. K y.)

was there any clear and convincing proof, by a fair pre

ponderance of the evidence, at the trials below that:

(1) The round trip ticket issued for travel was “ for

the account” of the defendant initial carrier therein.

Indeed, in Chatters, supra, as indicated from the excerpt

of the court’s opinion recited on page 17 of appellant’s

brief, the ticket issued by the initial carrier under the

joint tariff then prevailing was expressly “ for the account

of Southern” , a connecting carrier. Similarly, in Morrison

v. The Pennsylvania Railroad Company, supra, the ticket

was issued for the account of a connecting carrier. Each

14

of the stubs of the ticket issued by appellant to appellee here

in, however, recited expressly on its face, that it was issued

“ for the account” of appellant, the initial carrier, and not

the connecting carrier as in the Morrison and Chatters

cases. The decisions in the other cases cited by appellant

and cited hereinabove were either silent on this fact or

involved the issuance of tickets by the initial carrier for

the account of a connecting carrier.

(2) The defendant was a direct recipient and bene

ficiary of an economically advantageous relationship with

the connecting carrier, upon whose lines plaintiff-passenger

sustained her injuries, and of a significant percentage of

the proceeds derived from the sale to plaintiff of transpor

tation over the lines of a connecting carrier.

(3) The defendant had held itself out to plaintiff

passenger that it had undertaken, as principal by special

contract, the transportation of plaintiff to her ticketed

destination.

(4) Plaintiff had affirmatively relied upon said repre

sentations and undertaking by defendant.

(5) The connecting carrier had engaged in wanton and

willful acts of misconduct directly resulting in physical

abuses and injuries to the plaintiff therein.

Moreover, the court, in Chatters, supra, at pages 330-331

(see App. Br., p. 17) said:

“ But there was no basis, either in pleading or

proof, for a joint liability of both petitioners for the

negligence of one * * There was, therefore, no

evidence of joint liability of petitioners in the ease

* * V ’ (Emphasis added.)

The court, in Wooten v. Pennsylvania Railroad Co.,

supra, in distinguishing the facts of that case from those

in Chatters, supra, said of the Chatters case at p. 224:

“ There a directed verdict in favor of an issuing

carrier was proper in a tort suit against it and the

15

connecting carrier where there were no allegations

or proof of negligence by its employees or of such

relationship that negligence could he imputed to the

issuing c a r r i e r (Emphasis added.)

The court then went on to say that, in contrast to

Chatters:

“ These very issues were in dispute in the case

before us.” (Emphasis added.)

In the case at bar, however, there was “ proof * * # of

such relationship, that negligence could be imputed to the

issuing carrier” . At the trial herein these issues were in

dispute and were resolved by the court below, the trier of

the facts, in its findings that the totality o f circumstances

established “ such relationship” (a special contract) be

tween appellant and appellee. Accordingly, under the

principle of respondeat superior the negligence of Southern

Stages, Inc. can be imputed to appellant, initial carrier.

The Spears case, supra, is inapposite to the facts herein

and is not applicable authority for absolving appellant from

injuries sustained by appellee on the line of Southern

Stages. 'The very excerpt from the court’s opinion in

Spears, quoted at page 19 of appellant’s brief, that:

“ Generally, however, a carrier is only responsible

for acts over its own lines, acts over which it has

control (citing Chatters) * * * ”

impliedly recognized that, under facts other than those in

Spears, supra, and Chatters, supra, an initial carrier may

incur liability for injuries sustained by a passenger over

the lines of the connecting carrier.

Similarly, in the Morrison case, supra, the very portion

of the court’s decision quoted by appellant (App. Br., p. 20)

shows that the “ initial carrier’s liability would depend

upon the terms of its contract with the passenger” . While,

as the court noted, these terms may be evidenced by the

16

provisions of the tariffs, the court clearly did not intend to

exclude the consideration of other circumstances as shown

by the court’s citation of the Talcott v. Wabash R.R. Co.,

supra, case which squarely held that it is a question of fact

to be determined by all the circumstances whether the

initial carrier had contracted as principal for the convey

ance of a passenger over the whole route.

It is respectfully submitted that, by reason of the special

contractual relationship that arose between appellant and

appellee under the particular facts of this case, appellant,

as an initial carrier, cannot by contractual relationships

with other instrumentalities or entities avoid its own obli

gation and duty to its passengers for the entire length of

the contractual journey. This principle was strongly re

affirmed by the U. S. Supreme Court in Roynton v. Common

wealth of Virginia, 364 U. S. 454, 460-461. In this case, while

the civil liability of a carrier to its passenger was not in

issue, it was nevertheless necessary to decide whether an

interstate carrier ’s obligation to provide unsegregated serv

ice to its passenger extended to the facilities of a terminal

restaurant. The restaurant in question was not owned by

the carrier and was not supervised by any employees of

the carrier. Nevertheless, the court held that the obligation

of the carrier under the Interstate Commerce Act to pro

vide non-discriminatory accommodations to its passengers

extended to the facilities of the terminal restaurant. Justice

Black in so holding made the following statement:

“ Respondent correctly points out, however, that,

whatever may be the facts, the evidence in this rec

ord does not show that the bus company owns or

actively operates or directly controls the bus ter

minal or the restaurant in it. But the fact that

Sec. 203(a) (19) says that the protections of the

motor carrier provisions of the Act extend to ‘ in

clude’ facilities so operated or controlled by no

means should be interpreted to exempt motor car

riers from their statutory duty under Sec. 216(d)

not to discriminate should they choose to provide

17

their interstate passengers with services that are

an integral part of transportation through the use

of facilities they neither own, control nor operate.

The protections afforded by the Act against dis

criminatory transportation services are not so nar

rowly limited. We have held that a railroad cannot

escape its statutory duty to treat its shippers alike

either by use of facilities it does not own or by con

tractual arrangement with the owner of those facil

ities. United States v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co.,

supra. And so here, without regard to contracts,

if the bus carrier has volunteered to make terminal

and restaurant facilities and services available to

its interstate passengers as a regular part of their

transportation, and the terminal and restaurant have

acquiesced and cooperated in this undertaking, the

terminal and restaurant must perform those services

without discriminations prohibited by the Act. In

the performance of those services under such con

ditions the terminal and restaurant stand in the

place of the bus company in the performance of its

transportation obligations. Cf. Derrington v. Plum

mer, 240 F. 2d 922, 925-926, cert, denied, 353

U. 8. 924, 77 S. Ct. 680, 1 L. Ed. 2d 719. Although

the courts below made no findings of fact, we think

the evidence in this case shows such a relationship

and situation here.”

B. Appellant W as the Recipient o f Economic or

Financial Benefits From Proceeds Derived

From the Transportation o f A ppellee Over the

Lines o f Connecting Carriers.

Appellant seeks to construct a principle of law from

the absence of evidence before the court in Chatters, supra,

on the question of whether the initial carrier received any

of the proceeds derived from the sale of a coupon ticket for

transportation beyond its own line. That the Chatters case

and the other cases which allegedly follow “ the rule laid

down in Chatters” made no mention of money inuring

to the initial carrier did not preclude the trial court

or any other subsequent court, from taking cognizance of

18

this fact which was established by affirmative proof at

the trial. Appellant, dissatisfied with the record facts

in this case, seeks to avoid the factual finding of the

trial court that it received 10% of the proceeds derived

from the transportation of appellee over the lines of

connecting carriers (15a). Not having record facts satis

factory to its liking, appellant would have this court de

termine the question of its liability to appellee not on the

record facts present in this case, but on record facts pres

ent in other cases, distinctive and different than the factual

circumstances in the case at bar.

Appellant contends that it received nothing he., no

economic gain or benefit, from the sale of the coupon ticket

beyond its own line (App. Br. 22) because the Port Au

thority charges appellant for use of its terminal at a

rental of 10% of all money taken in by appellant at the

terminal. It is respectfully submitted that appellant has

misconstrued the record evidence and assumed relation

ships which do not exist in this record. The record is bar

ren of any fact which would indicate, in any way, that

the commission (132a) received by appellant was ear

marked or designated to be turned over to the Port Au

thority for the rental cost in the terminal.

The testimony of appellant’s own witness, Thomas B.

Stevens (129a-146a) makes it amply clear that the ap

pellant has incurred costs in its operations at the Port

Authority Terminal, and that one of these costs is the

rental charge which is equal to 10% of all monies taken in

by appellant at the terminal. Whether appellant received

a commission of 10% from the connecting carriers who

are transporting its passengers to their destinations or

receives 5%, or even no commission, appellant would be

liable to the Port Authority for the rental charge of 10%.

By receiving 10% of the proceeds derived from the trans

portation of the passenger over the lines of connecting

carriers, appellant has clearly received an economic benefit

19

— a monetary amount which it could use to pay the terminal

rent, or use for other purposes as it saw fit. If appellant

mistakenly paid over to the connecting carrier 100% of the

proceeds derived from transportation of the passenger

over that carrier’s lines, appellant would have a contract

right to recover its commission from that carrier. Ob

viously, during the time that it was not in possession of

this commission, it could not avoid its unrelated rental

obligation to the Port Authority.

Essentially, appellant’s position is that, since it has

a rental obligation of 10% of all monies received from the

sale of tickets, its commission of 10% from the proceeds

derived from the transportation of the passenger over the

lines of the connecting carriers is never received by it

and is of no benefit to it. As indicated above, the funda

mental error in this analysis is revealed by the fact that,

regardless of whether or not any commission is received

by appellant, it must pay the rental charge of 10% of

the income from, the sale of the tickets. As long as the

tickets are sold and money received for their sale, ap

pellant is obligated for the rental charge. The 10% com

mission is of no less a benefit to appellant because it ap

plies this money to the payment of rent than it would be if

it applied it to the payment of salaries to its employees

or for other expenditures. Cf. Schmidt v. Randall, 160 F.

Supp. 228, 230 (D. C. Minn.!), wherein the court held that

the 10% commission received by a hotel from the sale

of bus tickets was to be included in the hotel’s annual dollar

volume to determine whether it was exempt under the

Fair Labor Standards Act (29 U. S. C. Sec. 213(a)(2)),

and the court noted that from this commission the hotel

must pay operating expenses and a portion of an em

ployee’s salary.

I f appellant is correct, then the contention that noth

ing was received and no benefit was realized from the sale

of an article could be made by any seller in regard to any

20

commission so long as he was able to match an item of

cost in his operations which was substantially equal to

the amount of commissions. Clearly, such a result runs

contrary to basic legal and business sense. Nevertheless,

the record herein demonstrates that this is precisely what

appellant has done, since appellant’s witness admits that

its total costs of operations in New York are 20% (143a)

and that it has only been able to obtain commissions equiva

lent to 10%.

P O I N T V

Appellant is liable for the acts of the police officer

and for the act of the driver in calling the police

officer and identifying appellee.

A. Motor Carriers of Passengers Must Exercise

Extraordinary Care and Diligence for Safety

of Their Passengers.

Appellant was required to exercise the highest degree

of care, diligence and precaution for the safety of appellee

who, by special contract, it had undertaken to transport.

Mitchell v. L. E. W. R. Co., 146 U. S. 513; Greyhound

Corporation v. Ault, 238 F. 2d 198, 201 (5th Cir.) See also

Gregory v. Elmira Water Light & R. Co., 190 N. Y. 363;

Griffen v. Manice, 166 N. Y. 188.

As stated in Greyhound Corporation v. Ault, supra, the

rule in Georgia, the situs of the breaches of duty and wrong

ful acts proven herein, is that:

“ * * * all carriers of passengers, though not in

surers, must exercise extraordinary care and dili

gence for the safety of their passengers, and * # *

the Georgia statutes provide that proof of injury is

‘ prima facie evidence of want of reasonable skill and

care’ on the part of motor carriers. Sec. 68-710,

Georgia Code Annotated.”

21

The Georgia Code, Section 105-202, defines extraor

dinary diligence as follows:

“ In general, extraordinary diligence is that ex

treme care and caution which very prudent and

thoughtful persons exercise under the same or similar

circumstances. * * * The absence of such diligence is

termed slight negligence.1’ ’

Proof of the injuries sustained by appellee while travel

ling on the line of Southern Stages is prima facie evidence

of want of reasonable skill and care on the part of the agents

of appellant. The undisputed record facts of the injuries

sustained by appellee, as described by her own testimony and

that of the witness, Rosa Lee Benjamin (93a-100a, 110a-

112a) demonstrated the absence of due care and regard for

the safety and welfare of appellee. See Green Bus Lines,

Inc. v. Ocean Acc. and Guarantee Corp., 287 N. Y. 309, 312.

Appellant grossly violated the standard of care required

of it in the transportation of appellee pursuant to its special

contract therewith. The trial court, as the trier of fact,

found on the basis of the evidence adduced at the trial that

the injuries sustained by appellee occurred by reason of

affirmative acts of negligence and misconduct committed

against the person of appellee, while travelling on the bus

line of Southern Stages.

The Court below found that:

“ In the instant case, the evidence is abundantly

dear that the entire occurrence was instigated by the

bus driver. Plaintiff was not causing a disturbance

and had not violated any regulation of laiu. Notwith

standing this fact, the "driver left the bus and made

a telephone call to the police and deliberately brought

about the unlawful ejection of plaintiff from the bus.

He himself directed the officer to plaintiff without

any prior request, and further prevented anyone

from coming to plaintiff’s assistance. This is a clear

case in which the driver maliciously initiated, in

stigated and brought about the unlawful ejection of

plaintiff and thereby proximately caused the damages

22

and injuries sustained by her. Under these circum

stances, it is no defense that the physical assault

itself was not committed by the driver.” (17a) (Em

phasis added.)

Contrary to the assertions of appellant (App. Br., 29

and 30) the conduct of the employee of Southern Stages

and of the police officer to whom he identified appellee was

within the foreseeable zone of risk, specifically to be per

ceived and anticipated from appellant’s breach of its duty

of care to appellee as a passenger. See Bulloch v. Tamiami

Trail Tours, Inc., 266 F. 2d 326 (5th Cir.).

B. That the Injuries Sustained by A ppellee Re

sulted Partially From Acts Committed by an

Officer o f the Law Does Not Absolve Appellant

From Liability.

As was said in the opinion of the court below, the ap

plicable law governing these particular circumstances of

this case was enunciated in the case of Matthews v. Southern

By. System, 157 F. 2d 609, 610-11 (D. C. Cir.) wherein it

was said:

“ This case is governed by the rules of law ap

plicable to the obligations of a common carrier to its

passengers and its liabilities for breach of those

obligations. A common carrier is required to protect

its passengers against assault or interference with

the peaceful completion of their journey. But an

exception to the general rule is that an agent of the

carrier is not required to interfere with a known

officer of the law apparently engaged in the perform

ance of his duty. This exception covers the action

of an agent of a carrier in pointing out to a known

officer of the law persons as to whom the officer in

quires * * * Under the exception, the railroad is not

liable for action of its agents in notifying police

officers of violations of law or suspected violations.

This latter is so because of the basic public policy

which protects such notification generally and also

because of the primary duty of the conductor of a

train to protect passengers from injury by others;

23

e.g., assault, robbery, insult, disturbance, etc., in

which cases the conductor must call the police. But

the exception goes no further. It does not cover the

action of the agent in otherwise causing, procuring,

assisting in, or participating in the arrest or ejection,

or where the arrest is at the instance of the agent.

In other words, there is a clear line between the action

of an agent of a carrier in merely notifying the police

of a violation of law or identifying persons at the

request of a police officer, and his action in going

beyond mere notification or identification and by some

additional act procuring, causing, directing, or par

ticipating in an arrest or ejection.”

The Kinchlow v. People’s Rapid Transit Co., et ad.

case, 88 Fed. 2d 764 (C. C. A. D. C.) c. d. 57 Sup. Ct.

726, cited on page 30 of appellant’s brief, is distinguish

able from the case at bar because in Kinchlow, the trial

court found, as a question of fact, that the ejection of

plaintiff-passenger therein from a connecting carrier motor

bus, resulted solely from the disorderly conduct of plain

tiff when ordered by a police officer to change her seat.

Contrary to the action of appellant’s agent Southern Stages,

Inc., in Kinchlow “ the driver took no part in the actual

ejection of the passenger(s) from the car, nor did he

order or request the policeman to eject plaintiff ” (at p.

767). (Emphasis added.)

Appellant’s assertion on page 30 (App. Br.) that “ There

is no proof that the driver requested the sheriff to remove

plaintiff from the bus” , in the present case is not sup

ported by the record below or by the finding of the trial

court (17A).

Tompkins v. Missouri K <$> T Ry. Co., 211 Fed. 391

(C. C. A. 8th Cir.), also cited on page 30 of appellant’s

brief, is distinguishable from the facts before this court

because there, in the language of the court: “ The record

* * * contain (ed) no evidence that the Pullman Company,

or any of its officers or employees, ever requested, or in

any way caused or instigated the removal of the plaintiff

24

from the Pullman car in which he was riding * * * ” (at

394). (Emphasis added.)

In the Scholwin case, 70 S. E. 2d 792, 86 Ga. App. 99,

cited on page 31 of appellant’s brief, the court said in a

sentence immediately preceding the excerpt from the court’s

opinion, quoted in appellant’s brief, that “ while a carrier

owes to his passenger the duty of protecting him from

insult, injury, and mortification, the carrier is not liable

where a passenger is arrested by a sheriff under a valid

process” (at 795). (Emphasis added.)

Surely appellant cannot contend that the evidence pre

sented at the trial below disclosed any valid and lawful

process under which appellee was arrested. The undis

puted record fact is that the plaintiff was not committing

any act in violation of law at the time the wrongful acts

were committed against her, while travelling pursuant to

her special contract with appellant on the connecting line

of Southern Stages, Inc.

The Brunswick v. Western R. R. Co. v. Ponder, 117 Ga.

63, also cited on page 31 of appellant’s brief, is distinguish

able from the present controversy, as is the Tompkins case,

supra, in that in Brunswick three men boarded the train

to arrest the plaintiff therein, wholly and completely inde

pendent of any act on the part of any officer or employee

of the connecting carrier in which the plaintiff was riding.

The court said that “ the company was under no duty to

inquire into the legality of the arrest” because “ the arrest

was apparently regular, and in the absence of any knowl

edge or notice to the contrary, the officers and agents of

the company could assume that it was lawful” (at p. 63,

App. Br.).

The arrest of appellee, however, while travelling on

Southern Stages, Inc., was not “ apparently regular” and

there was no absence of any knowledge or notice to the

contrary on the part of appellee’s agents. Accordingly,

25

there is no basis on the record facts herein for asserting

that Southern Stages, Inc., agent of appellant in carrying

out its special contract with appellee, could assume that

the arrest of appellee was lawful (17a).

Finally, appellee has never contended “ that appellant

should not sell tickets to colored people because of the

possibility of conflict with a local bigot, be he a passenger,

a bus driver or a police officer” (App. Br., p. 32). Appellee

does contend, and the lower court has found, that when

appellant enters into an engagement to transport a pas

senger to her destination, which involves travel over the

lines of connecting carriers to carry out the engagement,

then appellant itself and through its agents, connecting

carriers, has a responsibility to exercise due care for the

passenger’s safety and to refrain from wrongful acts which

are the proximate cause of injury to the passenger.

CONCLUSION

For the above stated reasons, the judgment below

should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

L u bell , L ubell and J ones,

Charles T. M cK in n e y ,

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Appellee.

Clarence B. J ones and

J on athan W . L hbell ,

of Counsel.

T he H ecla P ress, 54 L afayette Street, N ew Y ork City , BE ekm an 3-2320

«̂ §iP»39