Notice of Hearing; Motion to Dismiss; Memorandum in Support of Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss; Order

Public Court Documents

March 18, 1987

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Notice of Hearing; Motion to Dismiss; Memorandum in Support of Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss; Order, 1987. d2fba731-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/24ffa19e-33e0-416b-9514-3f5c72010e53/notice-of-hearing-motion-to-dismiss-memorandum-in-support-of-defendant-s-motion-to-dismiss-order. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

+4..

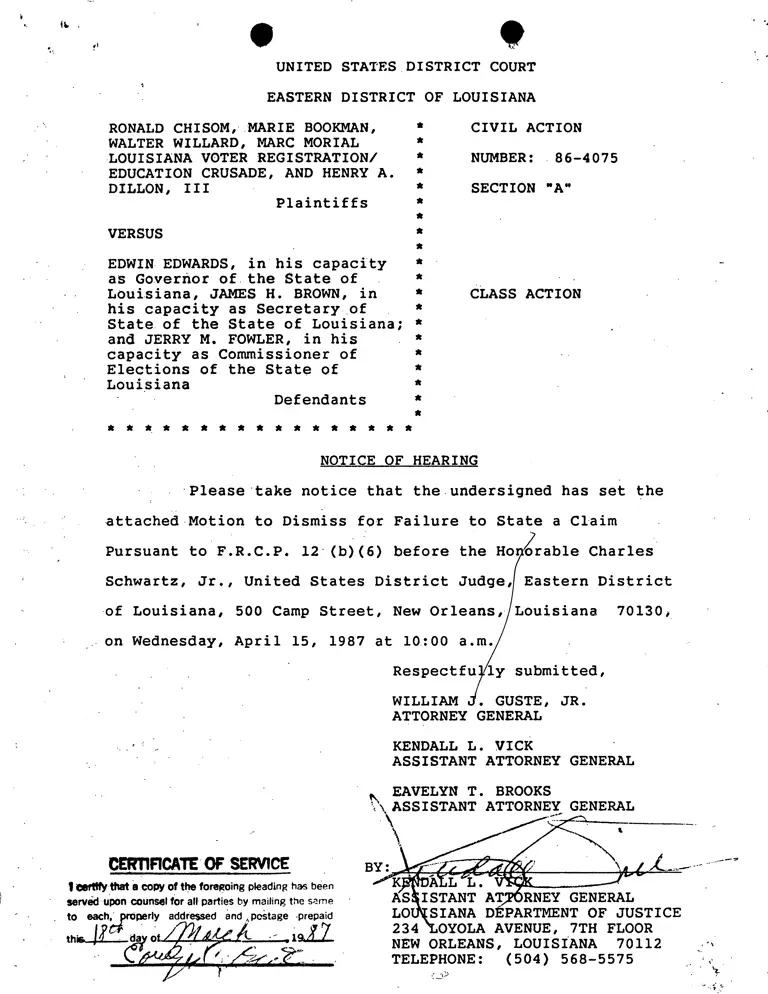

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN,

WALTER WILLARD, MARC MORIAL

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/

EDUCATION CRUSADE, AND HENRY A.

DILLON, III

Plaintiffs

VERSUS

EDWIN EDWARDS, in his capacity

as Governor of the State of

Louisiana, JAMES H. BROWN, in

his capacity as Secretary of

State of the State of Louisiana;

and JERRY M. FOWLER, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

Elections of the State of

Louisiana

Defendants

* * • * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

CIVIL ACTION

NUMBER: 86-4075

SECTION "A"

CLASS ACTION

NOTICE OF HEARING

Please take notice that the undersigned has set the

attached Motion to Dismiss for Failure to State a Claim

Pursuant to F.R.C.P. 12 (b)(6) before the Ho i;rable Charles

Schwartz, Jr., United States District Judge, Eastern District

of Louisiana, 500 Camp Street, New Orleans Louisiana 70130,

on Wednesday, April 15, 1987 at 10:00 a.m.

Respectfu ly submitted,

WILLIAM . GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

, KENDALL L. VICK

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

CER11RCATE OF SERVICE BY:

I Certify .that a copy of the foregoing pleading has been

served upon counsel for all parties by mailing the same

to each, perly addressed and pcitage -prepaid

this. I/ da of/ /A ia

frti

r •

EAVELYN T. BROOKS

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

K A L L.

AS• ISTANT AT IRNEY GENERAL

LO SIANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

234 OYOLA AVENUE, 7TH FLOOR

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA 70112

TELEPHONE: (504) 568-5575

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN, CIVIL ACTION

WALTER WILLARD, MARC MORIAL

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/ NUMBER: 86-4075

EDUCATION CRUSADE, AND HENRY A. *

DILLON, III SECTION "A"

Plaintiffs

VERSUS

EDWIN EDWARDS, in his capacity

as Governor of the State of

Louisiana, JAMES H. BROWN, in CLASS ACTION

his capacity as Secretary of

State of the State of

Louisiana; and JERRY M. FOWLER, *

in his capacity as Commissioner *

of Elections of the State of

Louisiana

• Defendants

* * * * * * * * * * * * * •* * * *

MOTION TO DISMISS FOR FAILURE TO STATE

A CLAIM UPON WHICH RELIEF CAN BE GRANTED PURSUANT

TO FEDERAL RULE OF CIVIL PROCEDURE 12 (b)(6)

Pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12 (b)(6),

defendants, Edwin Edwards in his capacity as Governor of the

State of Louisiana; James H. Brown, in his capacity as

Secretary of State of the State of Louisiana; and Jerry M.

Fowler, in his capacity as Commissioner of Elections of the

State of Louisiana, move the court to dismiss the action

because the complaint fails to state a claim against defendant

upon which relief can be granted.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM J. GUSTE D JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

KENDALL L. VICK

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

EAVELYN T. BROOKS

\ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a copy of the foregoing pleading has been

served upon counsel for all parties by mailing the same

to each, ppparly addreséd and . postage prepaid

/'/ • •

1%12i_

e-day

LL L. VI

A S STANT ATTO EY GENERAL

LOU IANA DE RTMENT OF JUSTICE

234 OYOLA AVENUE, 7TH FLOOR

NEW 0 LEANS, LOUISIANA 70112

TELEPHONE: (504) 568-5575

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERALS:

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Blake G. Arata, .Esq.

na.st. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

A. R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

-2-

• •

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN,

WALTER WILLARD, MARC MORIAL

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/

EDUCATION CRUSADE, AND HENRY A.

DILLON, III

Plaintiffs

VERSUS

EDWIN EDWARDS, in his capacity

as Governor of the State of

Louisiana, JAMES H. BROWN, in

his capacity as Secretary of

State of the State of Louisiana; *

and JERRY M. FOWLER, in his

capacity as Commissioner of

Elections of the State of

Louisiana

Defendants

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

CIVIL ACTION

NUMBER: 86-4075

SECTION "A"

CLASS ACTION

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF DEFENDANT'S

MOTION TO DISMISS FOR FAILURE TO STATE

A CLAIM UPON WHICH RELIEF CAN BE GRANTED. -

The defendants, Edwin Edwards, in his capacity as

Governor of the State of Louisiana; James H. Brown, in his

capacity as Secretary of State of the State of Louisiana; and

Jerry M. Fowler, in his capacity as Commissioner of Elections

of the State of Louisiana, respectfully submit this Memorandum

in Support of their Motion to Dismiss. For the reasons stated

below, the plaintiffs' complaint fails to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 12 (b)(6). Accordingly, the court should dismiss the

plaintiffs' complaint.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On September 22, 1986, Ronald Chisom, four other black

plaintiffs, and a non-profit corporation, filed a class action

suit on behalf of all black registered voters in Orleans Parish

challenging the election of Justices from the First District of

the Louisiana Supreme Court.

Plaintiffs contend that the present system of electing

• judges, whereby the Parishes of Orleans, St. Bernard,

Plaquemines, and Jefferson elect at large, two Justices to the

Louisiana Supreme Court, is in violation of the 1965 Voting

Rights Act, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §1973, the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and

§1983 of Title 42 of the United States Code. Specifically, the

plaintiffs charge (1) that the present method of electing at

large two Justices to the Louisiana Supreme Court from the New

Orleans area impermissibly dilutes minority voting strength in

violation of §2 of the Voting Rights Act, and (2) that

defendants' actions are in violation of the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution and 42

U.S.C. g1983 in that the purpose and effect of their actions is

to dilute, minimize, and cancel the voting strength of

plaintiffs.

Plaintiffs ask the court to convene a three-judge

court to hear the claims, to certify this matter as a class

action and to issue declaratory and injunctive relief against

the defendants as follows:

(1) enjoin defendants from allowing elections of

Justices from the district in question until this

court has made a decision on the merits of this

action; (2) order defendants to reapportion the

district in a way that would remedy the alleged

• dilution of minority voting strength; and (3) declare

that defendants have violated §2 of the Voting Rights

• Act as well as.the-Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

• Finally, plaintiffs seek to recover court costs, litigation

expenses and attorneys' fees.

On November 12, 1986, at • hearing to determine

whether a three-judge court should be convened, the court found

that this action should and will be tried as a one judge case.

The defendants move to dismiss plaintiffs' complaint

for failure to state a claim upon which relief can be granted.

Defendants respectfully submit that the statute upon which

plaintiffs base this action does not support the allegations in

the complaint, and that there is no provision in the

Constitution of the United States of America or in any statute

of the United States authorizing any court to grant the relief

which plaintiffs herein seek.

ARGUMENT

The first sentence of the opinion of the United States

Supreme Court in Thornburg v. Gingles, U.S. , 106

S.Ct. 2572 (1986), reads as follows:

This case requires that we construe for the

first time §2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965, as amended June 29, 1982. 42 U.S.C.

§1973.

It is the contention of the defendants that the case at bar

requires that this court construe for the first time whether

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 applies to state

court judges.

Historically, judges were recognized as unique from

other officials. See Morial v. Judiciary Comm. of State of

Louisiana, 565 F.2d 295 (1977 en banc), cert. denied, 435 U.S.

1013, 98 S.Ct. 1887 (1978). Our federal Constitution placed

the judiciary in an entirely different category from that of

any other elective office. For two hundred years, our

judiciary has been expected to render its decisions based upon

the merits of the claims •of the litigants. This philosophical

precept has prevailed in every free country in the world and

has existed for many centuries in England, whence came our body

of laws.

That was the background at the time that the

Constitution was adopted, and implicity it was incorporated

into the meaning of Article III of the Constitution. Articles

and.II, establishing the Congress and the Presidency

respectively, are lengthy and detailed. By comparison Article

III establishing the judiciary is so brief and free of

direction to the judiciary that by the very absence of any

instructions, it loudly proclaims that the well known and

prevailing concepts of justice were necessarily imperative

mandates only that the Court do. justice.

Bacon, talking of judges, said: "Integrity is their

portion and proper virtue." Livingston said "that their

decisions should behold neither plaintiff, defendant, nor

pleader but only the cause itself." A judge is not supposed to

represent any individual or any group of individuals. See,

Holshouser V. Scott, 335 F.Supp. 928 (M.D.N.C. 1971), aff'd.

409 U.S. 807, 93 S.Ct. 43(1972); New York State Association of

Trial Lawyers v. Rockefeller, 267 F.Supp. 148 (S.D.N.Y. 1967).

No minority is entitled to have a judge committed to it. A

court is obliged only to interpret the Constitution and the

•laws as enacted. It leans neither to the left nor to the

right, to the wealthy nor the impoverished, to the white nor

the black, to the urban nor the rural. By their very nature

and the oath that they take, judges are so obligated. No group

is entitled to be represented on a court. Such a situation

would impair the faith of the litigants and their confidence in

the judicial system. That is a requirement which every court

needs to enforce its edicts, for without that, it does not have

the power to do so.

The guarantee of judicial probity is essential to the

functioning of our system. In this context, any requirement

that a segment of our society should be represented on a court

connotes only that such representation is a ploy not designated

to do justice but to serve political purposes.

Defendants' position, as above stated, is merely

saying again what was so succinctly put in Buchanan v. Rhodes,

249 F.Supp. 860 (N.D. Ohio 1966), app. dismissed, 385 U.S. 3,

87 S.Ct. 33 (1966), and quoted in Wells v. Edwards, 347 F.Supp.

453 (M.D. La. 1972), affirmed, 409 U.S. 1095, 93 S.Ct. 904

(1973): "Judges do not represent people, they serve people."

In Wells, supra, plaintiff sought the reapportionment

of the judicial districts from which the seven justices of the

Supreme Court of Louisiana were elected and the defendants

responded with a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim

upon which relief could be granted. The three-judge court

(panel composed of Judges Ainsworth, Gordon and West) did not

reach the issue urged by plaintiff "simply because we hold that

the concept of one-man, one-vote apportionment does not apply

to the judicial branch of the government". 347 F.Supp. at 454.

It is well to note that Article V of the 1974

Constitution of Louisiana establishes our Supreme Court, its

composition (Art. V, Sec. 3) and the method by which its

Justices are elected (Art. V, Sec. 4). That Constitution was

approved under the Voting Rights Act, §5, by the United States

Department of Justice on November 26, 1974.

Justice White (joined by Justices Douglas and

Marshall) dissented from the affirmance of Wells, supra, in an

opinion written prior to the addition of §2(b) to the Voting

Rights Act. Justice White argued that "Judges are not private

citizens...They are state officials, vested with state •

powers...to carry out...judicial functions." 409 U.S. at

1096. That dissent, however, disregarded the essential

differences between judges, who must interpret the law with a

free, even, unbiased mind, unfettered and untainted by any

constraints or political motives, and legislators, a difference

subsequently recognized by statute. Therefore, defendants

contend Justice White's dissenting opinion equated judicial

S

decisions with mere ministerial functions; it equated the

adjudicatory process with political decision-making.

In Haith v. Martin, 618 F.Supp. 410 (E.D.N.C. 1985),

affm'd., 106 S.Ct. 3268 (1986), the court held that judicial

elections are subject to Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act

Requirements. The defendants, in that case, argued that

Section 5 did not apply ta judicial elections, relying on the

one-man, one-vote cases. The District Court rejected these

cases as inapplicable:

Discounting the interesting jurisprudential

arguments arising from such an attempted

distinction...it is quite clear that no such

distinction can be attributed to (§5 of the

Voting Rights] Act***As can be seen, the Act

applies to all voting without any limitation

to who, or what, is the object of the

vote***We hold that the fact that an

election law deals with the election of

members of the judiciary does not remove it

from the ambit of Section 5. 618 F.Supp. at

413.

In finding that §5 applies to judiciary elections the

court noted that §5 goes to the mechanics of voting, that is

the "standard, practice or procedure" which requires

• preclearance. Id. at 413. Therefore, the court concluded,

"Congress meant 'to reach any state enactment which altered the

election law of a covered state in even a minor way.'" Id.,

quoting Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 344, 89

•S.Ct. 817 (1969).

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, on the other hand,

does not deal with the mechanics of voting but with the

fundamental right to vote for those who govern. Cf: Thornburg

-7-

v. Gingles, zupra. For this reason Congress expressly uses in

the statute the phrase "to elect representatives of their

choice." The one-man, one-vote cases are based upon the

concept of representation. See Reynolds v. Sims, 277 U.S.

533, 84 S.Ct. 1362 (1964) and its progeny.

Thus, prior to 1982, when Congress amended Section 2

of the Voting Rights, the case law had established the

proposition- that the one-man, one-vote doctrine did not apply

to the election of judges since, judges did not represent

people. By using the term "representatives" in Section 2 and

not in Section 5, Congress employed a term of art, the meaning

of which it presumably understood. Courts must presume that

Congress knows the law. Director v. Perine North River

Associates, 459 U.S. 297, 319-20, 103 S.Ct. 634, 648 (1963);

Cannon v. University of Chicago, 441 U.S. 677, 696-97, 99 S.Ct.

1966, 1957-58 (1979).

Defendants respectfully submit that Haith, supra, does

not have the same precedential effect as Wells because a)

Haith was decided under S5 of the Voting Rights Act and b) any

statement vis-a-vis the effect of §2 on elections of judges

were based upon language contained in §2 prior to the 1982

Amendment, which clearly refers only to "representatives."

It is respectfully -urged that this Court is bound by Wells.

The affirmance of the three-judge decision, although not

receiving plenary consideration, is nevertheless precedential.

Ohio ex rel. Eaton v. Price, 360 U.S. 246, 247, 79 S.Ct. 978

(1959); see Sternand Gressman, Supreme Court Practice, 197

(4th Ed. 1969); C. Wright, Law of Federal Courts, 495 (2d Ed.

1970).

-8-

The distinction between the "representatives" of the

people and the judiciary was clearly drawn by Hamilton in The

Federalist, No. 78:

If it be said that the legislative body are

themselves the constitutional judges of

their own powers, and that the construction

they put upon them is conclusive upon the

other departments, it may be answered, that

this cannot be the natural presumption,

where it is not to be collected from any

particular provisions in the constitution.

It is not otherwise to be supposed that the

constitution could intend to enable the

representatives of the people to substitute

their will to that of their constituents.

It is far more rational to suppose that the

courts were designed to be an intermediate

body between the people and the legislature,

in order, among other things, to keep the

latter within the limits assigned to their

authority. The interpretation of the laws

is the proper and peculiar province of the

courts...

In Morial v. Judiciary Comm of State of Louisiana, 565

F.2d 295 (1977 en banc), cert. denied, 435 U.S. 1013, 98 S.Ct.

1887 (1978), the Fifth Circuit held inter alia,

The equal protection clause of the constitution does

not put the states to the choice of foregoing an ,

elective judiciary or treating candidates for judicial

office like candidates for all other elective

offices. The Louisiana constitution, like the federal

constitution, creates a separate judicial branch.

Article V of the Louisiana constitution is devoted

entirely to the functions and duties of that branch.

The structure, powers, duties, and emoluments of the

state's judiciary are treated differently from those

of "Public Officials," who are dealt with in a

separate.article of the constitution, article IX.

Because the judicial office is different in key

respects from other offices, the state may regulate

its judges with the differences in mind. For example

the contours of the function make inappropriate the

same kind of particularized pledges of conduct in

office that are the very stuff of campaigns for most

non-judicial offices. A candidate for the mayoralty

-9-

can and often should announce his determination to

effect some program, to reach a particular result on

some question of city policy, or to advance the

interests of a particular group. It is expected that

his decisions in office may be predetermined by

campaign commitment. He cannot, consistent with the

proper exercise of his judicial powers, bind himself

to decide particular cases in order to achieve a given

programmatic result. 10 Moreover, the judge acts on

individual cases and not broad programs. The judge

legislates but interstitially; the progress through

the law of a particular judges' social and political

performance preferences is, in Mr. Justice Holmes'

words, "confined from molar to molecular motion."

Southern Pacific Co. v. Jensen, 244 U.S. 205, 221, 37

S.Ct. 524, 531 (1916) (Holmes, J., dissenting).

It is with this background that the members of

Congress enacted S2 of the Voting Rights Act. The wording of

the statute evidences no intent to break from that historic

perspective and those words are the starting point of any

statutory analysis. American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson, 456

U.S. 63, 68, 102 S.Ct. 1534, 1537 (1982). Section 2 provides

in full; as follows:

- (a) No voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting or standard,

practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political

subdivision in a manner which results in a

denial or abridgement of the right of any

citizen of the United States to vote on

account of race or color, or in

contravention of the guarantees set forth in

section 1973b(f)(2) of this title, as

provided in subsection (b) of this section.

(b) A violation of subsection (a) of

this section is established if, based on the

totality of circumstances, it is shown that

the political processes leading to

nomination or election in the State or

political subdivision are not equally open

to participation by members of a class of

citizens protected by subsection (a) of this

section in that its members have less

opportunity that other members of the

electorate to participate in the political

-10-

process and to elect representatives of

their choice. The extent to which members

of a protected class have been elected to

office in the State or political subdivision

is one circumstance which may be

considered: Provided, That nothing in this

section establishes a right to have members

of a protected class elected in numbers

equal to their proportion in the population.

42 U.S.C. §1973 (emphasis added).

The question presented here is of the applicability of

^

a statute. When such a question arises, a decision can be

reached only by applying appropriate criterion. "For the

interpretation of statutes, 'intent of the legislature' is the

criterion that is most often recited." Sutherland Statutory

Construction §45.05, p. 21 (4th Ed). The rule for determining

legislative intent was best stated by Lord Blackburn in 1877:

In all cases the object is to see what is

the intention exposed by the words used.

But, from the imperfection of language, it

is impossible to know what that intention is

without inquiring further, and seeking what

the circumstances were with reference to

which the words were used, and what was the

object, appearing from those circumstances,

which the person using them had in view; for

the meaning of the word varies according to_

the circumstances with respect to which they

were used.

River Wear Com'rs v. Adamson, L.R. 2 AC 743

(1877).

See also: Cruver v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, 142 F.2d

363 (4th Cir. 1944); and United States v. Agrillo-Ladlad, 675

F.2d 905 (7th Cir., 1982) cert denied, 459 U.S. 829 (1982).

Determination of legislative intent by examination of

congressional publications is not conclusive. The rationale

and explanation for one legislator's statement may not be the

•

persuasive factor in securing his co-legislator's vote.

However, committee reports and floor debates are the only

information available to determine what Congress had in mind at

the time of a bill's enactment. In search of a statement

concerning the application of the Voting Rights Act to the

elected members of the judiciary, the House and Senate reports,

• the House-Senate Conference Committee reports, and the floor

debate in the two Congressional Chambers were consulted for the

intent for the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and subsequent

amendments in 1970, and 1975 as well as 1982.

Our exhaustive analysis of the legislative history of

Section 2 has discovered no mention of state court judges

whatsoever. However, several statements were made as to what

the bill does encompass.

The conclusions that can be drawn from the conspicuous

absence of mention of the judiciary are: (1) as not all

member's of the judiciary are elected, it is impossible that the

Voting Rights Act encompassed the judiciary in its entirety,

and thus a distinction may be made between the judiciary and

the legislature; (2) the fact that judges are not included in

examples and statistics presented during debate demonstrate the

absence of the speaker's intent that they be covered; and (3)

examination of selected publications on the 1965 bill and each

amendment reveals that at no time was coverage of the judiciary

addressed.

The following statements clearly show that the Voting

• Rights Act was not intended to cover the elected judiciary:

1965 BILL

Senator Kennedy [on May 7, 1965], who voted`with the

majority stated:

• The voting rights bill before us, which the

President of the United States presented to

• us so eloquently, as we all remember at the

• time of the crisis in Selma, Ala., will have

• its greatest effect in State elections. It

• is designed to give Negro citizens the right

• to participate in the choice of their

• sheriffs, •their mayors, their State

• legislators, and their Governor - all the

State and local officeholders whose

• activities have such an impact on their

lives - including the officeholders who have

been so prominent in discriminatory practice

against Negro citizens.

Congressional Record 9913 (1977).

1970 AMENDMENT

During Senate floor debate, 3-2-70 at p. 5520, the

speaker refers to the bill's applicability to "at large"

elections and uses the example of Louisiana police jury

elections.

Congressional Record 5520 (1970).

During Senate floor debate, the speaker mentions

elections to police juries, school boards, annexation tactics.

Id. at 5535.

• During Senate floor debate, Senator Dole at March 5,

1970 quotes the House report Statement of Representative

Richard H. Poff:

A government of the people cannot function

for the people unless it is a government by

the people. There is no such thing as

self-government if those subject to the law

do not participate'in the process by which

those laws are made. Only a few are

privileged to participate directly in the

process by which those laws are made. Only

a few are privileged to participate directly

in the physical mechanics of the lawmaking

process, and these are those chosen as

representatives by their fellows. For all

others, the opportunity for participation,

and therefore the essence of the concept of

self-government, is the right to cast a

ballot to choose those who make the laws.

If this opportunity is denied any qualified

citizen, then is not self-governed...

Senator Dole continued:

I referred to the statement of the

illustrious representative from Virginia,

Mr. Poff, in my statement, to emphasize, as

the Senator from Wyoming has done, that is a

profound statement and one of the best

available concerning the Voting Rights Act.

Representative Poff is recognized nationally

as one of the most able lawyers in Congress

and one of the most effective and fair

minded Members of Congress... Id. at 6160

During Senate floor debate, the speaker stated:

...But there is one basic issue which cannot be

obscured or forgotten, no matter how lengthy or

expressive the debate. •This is the fact that all

citizens have an inalienable right to participate in

the process by which they are governed. Id, at 6644

1975 AMENDMENT

The House Committee Report, No. 94-196 at p. 7 reads:

In much the same manner as improved registration rates

have been documented for blacks in covered southern

jurisdictions, so also has there been improvement in

those areas in terms of an increasing number of black

elected officials...After the November 1974 elections,

those states could boast of one black (sic) member of

the United States Congress, 68 black state

legislators, 429 black county officials, and 497 black

municipal officials (Hearings, 1032).

The Report continued with statistics counting the

number of state,legislative seats over time held by black

citizens.

The Senate Committee Report, No. 94-295, at p. 14

reads:

•

In much the same manner as improved registration rates

have been documented for blacks in covered southern

jurisdictions so also has there been improvement in

those areas in terms of an increasing number of black

elected officials. One estimate suggest that only 72

blacks served as elected officials in 11 states in

1965, including the southern states presently covered

by the Act. (Hearings, 115 by April 1974, the total

of black elected officials in the 7 southern states

covered by the Act had increased to 963. After the

November 1974 elections, those states could boast of

one black member of the United States Congress, 68

black state legislators, 429 black county officials,

and 497 black municipal officers (TYA 49). This rapid

increase in the number of black elected officials

marks the beginning of significant changes in

political life in the covered southern jurisdictions.

(TYA 52)

The Report continued with statistics counting the

number of state legislative seats over time held by black

citizens, just as in the House Report. This shows a consensus

of intent in the two houses.

1982 AMENDMENT

The House Committee Report, No. 97-227 at p. 14 reads:

The observable consequences of exclusion from

government to the minority communities in the covered

jurisdictions has been (1) fewer services from

government agencies, (2) failure to secure a share of

local government employment, (3) disproportionate

allocation of funds, location and type of capital

projects, (4) lack of equal access to health and

safety related services, as well as sports and

recreational facilities, (5) less than equal benefit

from the use of funds for cultural facilities, and (6)

location of undesirable facilities, e.g. garbage

dumps, or dog pounds, in minority areas.

(Note that the consequences listed all refer to

essentially legislative functions.)

The House Committee Report, No. 97-227 at p. 30 refers

to the dangers of at-large elections but concludes that not all

at-large elections are violations of the Act:

Section 2 prohibits any voting qualification,

prerequisite, standard, practice or procedure which is

discriminatory against racial and language minority group

persons or which have been used in a discriminatory manner to

deny such persons an equal opportunity-to participate in the

electoral process. This is intended to include not only voter

registration requirements and procedures, but also methods of

election and electoral structures, practices and procedures

which discriminate...strong link between at-large elections and

lack of minority representation. Not all at-large election

systems would be prohibited under this amendment, however, but

only those which are imposed or applied in a manner which

accomplishes a discriminatory result.

The House Committee Report also contains language

pertinent to the overall issue while not necessarily revealing

anything about legislative intent regarding the judiciary:

At page 30, the report reads:

•The proposed amendment (to Section 2) does not create

a right of proportional representation...This is not a

new standard. In determining the relevancy of

evidence the court should look to the context of the

challenged standard, practice or procedure. The

proposed amendment avoids highly suggestive factors

such as responsiveness of elected officials to the

minority community. Use of this criterion creates

inconsistencies among court decisions on the same or

similar facts and confusion about the law among

government officials and voters. An aggregate of

objective factors should be considered such as a

history of discrimination affecting the right to vote,

racially polarity voting which impedes the election

opportunities of minority group members,

discriminatory elements of the electoral system such

as at-large elections, a majority vote requirement, a

prohibition on single-shot voting, and numbered posts

which enhance the opportunity for discrimination, and

discriminatory slating or the failure of minorities to

win party nomination.'" All of these factors need

not be proved to establish a Section 2 violation.

...It would be illegal for an at-large election scheme

for a particular state or local body to permit a bloc

voting majority over a substantial period of time

consistently to defeat minority candidates or

candidates identified with the interests of a racial

or language minority...

(4) During Senate floor debate, at p. 6502 on 6-9-82,

Senator Hatch, who managed the bill but expressed reservations

about it, stated:

-16-

•

The at-large system of election is the principal

immediate target of proponents of the result test. 4

Despite repeated challenges to the propriety of the

at-large systems, the Supreme Court has consistently

rejected the notion that the at-large system of

election is inherently discriminatory toward

minorities. 5 The Court in Mobile (Mobile v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55) has observed that literally thousands of

municipalities and other local governmental units

throughout the Nation have adopted an at-large

system. 6

To establish a results test in Section 2 would be to

place at-large systems in constitutional jeopardy

throughout the Nation, particularly if jurisdiction

with such electoral systems contained significant

numbers of minorities and lacked proportional

representation on their elected representative

councils or legislatures...

Section 2's explicit use of the word "representative"

together with the historical distinction between the judiciary

and officials who govern and an analysis of Congressional

publications which only speak of representative officials,

clearly indicate Congress's intent that elected state court

judges should not be subjected to the Section 2 dilution

analysis. •

As previously noted, voter dilution cases have their

origin in the one-person, one-vote representation cases. See

e.g., Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 89 S.Ct.

817 (1969). As also previously demonstrated, the courts have

consistently held that judges are not subject to the

one-person, one-vote doctrine. Logically then, judicial

offices are not subject to voter dilution analysis.

The defendants recognize that the Fifth Circuit has

held in Voter Information Proiect, Inc. v. City of Baton Rouge,

612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980), that a Fourteenth and Fifteenth

-17-

Li>

Amendment racial dilution claim was stated as to the at-large,

post election of city and district judges in Louisiana where

the plaintiffs alleged that the statutes were adopted for a

racially discriminatory purpose and operated to dilute black

voting strength. The Fifth Circuit concluded: "If plaintiffs

can prove that the purpose and operative effect of such purpose

of the at-large election schemes in Baton Rouge is to dilute

the voting strength of black citizens, then they are entitled

to some form of relief." Id, at 212. The Fifth Circuit went

on to note that the plaintiffs sought declaratory and

injunctive relief and the implementation of a single-member

district scheme but the court stressed that it initiated "no

view concerning what relief would be appropriate assuming

plaintiffs could prove their allegations." Id. at 212 n.5.

In the present case, no claim is made by petitioners

that the present Louisiana constitutional and statutory

provisions governing the election of justices of the Supreme

Court of this State were intentionally discriminatory. Without

such an allegation, petitioner cannot establish a violation of

the 14th and 15th amendments. City of Mobile. Ala. v. Bolden,

446 U.S. 55, 100 S.Ct. 1490 (1980). Bolden has not been

overruled and is still precedential in this regard, although

•Congress subsequently amended •§2 of the Voting Rights Act to

remove the requirement of proof of an invidious purpose from

cases arising out of all but judicial elections.

Multimember districts are not per se unconstitutional,

nor are they necessarily unconstitutional when used in

combination with single-member districts in other parts of a

state, unless they "are being used invidiously to cancel out or

minimize the voting strength of racial groups." White v.

Register, 412 U.S. 755, 93 S.Ct. 2332, 37 L.Ed. (2d) 314

(1973).. Petitioners have not claimed such invidious use.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reason, defendants respectfully urge

this court to dismiss the complaint at Petitioner's costs.

Respectfully submitted,

WILLIAM J. GUSTE, JR.

ATTORNEY GENERAL

KENDALL L. VICK

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAL

EAVELYN T. BROOKS

ASSISTANT ATTORN7—GENERAT03---__

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I certify that a copy of the foregoing pleading has been

served upon courisel for all parties by mailing the same

to each, prpperly addressed .and ipostage prepaid

tbh. CrdaY. : • ick 67, 4 .

• • /--; • • . •c..)

• • C /

BY:

k

ALL L. VI

A ISTANT,6T- RNEY GENERAL

LO ISIANA DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

234 LOYOLA AVENUE, 7TH FLOOR

NEW •RLEANS, LOUISIANA 70112

PHONE: (504) 568-5575

SPECIAL ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERALS:

M. Truman Woodward, Jr., Esq.

1100 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Blake G. Arata, Esq.

210 St. Charles Avenue

Suite 4000

New Orleans, Louisiana 70170

A. R. Christovich, Esq.

1900 American Bank Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Moise W. Dennery, Esq.

21st Floor Pan American Life Center

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

-RONALD CHISOM, MARIE BOOKMAN, CIVIL ACTION

WALTER WILLARD, MARC MORIAL

LOUISIANA VOTER REGISTRATION/ NUMBER: 86-4075

EDUCATION CRUSADE, AND HENRY A.

DILLON, III SECTION "A"

Plaintiffs

VERSUS

EDWIN EDWARDS, in his capacity

as Governor of the State of

State Louisiana, JAMES H. BROWN, * CLASS ACTION

in his capacity as Secretary of

the State of Louisiana; and

JERRY M. FOWLER, in his capacity *

as Commissioner of Elections of

the State of Louisiana

Defendants

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

ORDER

IT IS ORDERED that the action against the defendants,

Edwin Edwards •in his capacity as Governor of the State of

Louisiana; James H. Brown, in his capacity as Secretary of

State of the State of Louisiana; and Jerry M. Fowler, in his

capacity as Commissioner of Elections of the State of

Louisiana, be dismissed for failure to state a claim upon which

relief can be granted pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil

Procedure 12 (b)(6), at plaintiff's cost.

New Orleans, Louisiana, this day

of , 1987.

UNITED STATES DISTRICT JUDGE