Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents

Public Court Documents

March 6, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. Federal Communications Commission Brief Amicus Curiae in Support of Respondents, 1990. d422198e-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/25072dec-17c3-4b0a-9fbb-b050ca057f1d/metro-broadcasting-inc-v-federal-communications-commission-brief-amicus-curiae-in-support-of-respondents. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

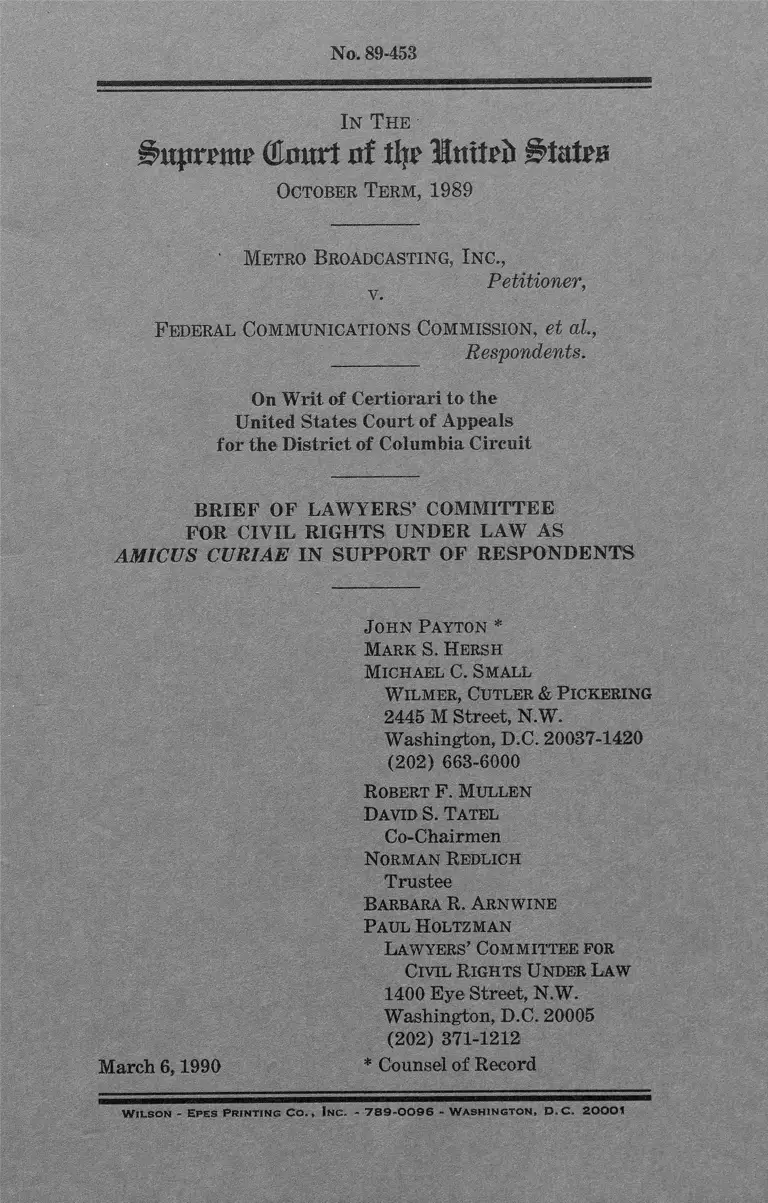

No. 89-453

In The -

(ta rt nf % TUmtib l̂ taira

October Term, 1989

■ Metro Broadcasting, Inc.,

Petitioner,

v. ■

Federal Communications Commission, et al,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF OF LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

John Payton *

Mark S. H ersh

M ichael C. Small

W ilmer , Cutler & P ickering

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037-1420

(202) 663-6000

R obert F. Mullen

David S. Tatel

Co-Chairmen

Norman R edlich

Trustee

Barbara R. A rn w in e

Paul H oltzman

Law yers ’ Committee for

Civil R ights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

March 6,1990 * Counsel of Record

W il s o n - Epes Pr in tin g Co . , In c . - 789-0096 - W a s h in g t o n , D.C, 20001

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE .................................. 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ........................................... 2

ARGUM ENT................... ..................... .................................... 3

I. CONGRESS M AY USE MINORITY PREF

ERENCES TO REMEDY THE PRESENT

EFFECTS OF SOCIETY-WIDE DISCRIMI

NATION ON BROADCASTING.......................... 5

A. Congress Must Be Allowed to Remedy the

Consequences of Society-Wide Discrimina

tion Through Race-Conscious Measures........ 5

1. Past society-wide discrimination has con

crete effects today that Congress must

have latitude to address .............................. 6

2. The Constitution gives Congress the

unique power to address the consequences

of society-wide discrimination__________ 9

B. Congress Had Sufficient Factual Support for

the Minority Preference Policy ------ ------ ---- - 13

II. THE INTEREST IN PROMOTING DIVER

SITY OF PERSPECTIVES IN BROADCAST

ING FURTHER SUPPORTS THE USE OF

MINORITY PREFERENCES IN LICENSING.. 16

A. Forward-Looking Interests May Support

the Use of Racial Preferences .......................... 17

B. The Promotion of Diversity of Perspectives

in Broadcasting Is a Substantial Interest.... 18

C. Congress Had Sufficient Basis to Link Diver

sity of Ownership With Diversity of Per

spectives in Broadcasting .................................. 19

III. THE MINORITY PREFERENCE POLICY

SATISFIES AN Y REASONABLE APPLICA

TION OF THE “NARROWLY TAILORED”

TEST................... 21

CONCLUSION.......................................................................... 26

Page

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

CASES: Page

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954).............................................................................. 8

Brown v. Hartlage, 456 U.S. 45 (1982).................. 12

CBS v. Democratic National Committee, 412 U.S.

94 (1973) ........... ....................... - _____ ____ ________ 4,13

City of Richmond v. J. A. Croson Co., 109 S. Ct.

706 (1989) ............ ............................... ....... ................passim

City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156

(1980) _________ 10

Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339 (1879)................. 9

FCC v. League of Women Voters, 468 U.S. 364

(1984)_____ 4

FCC v. National Citizens Committee for Broad

casting, 436 U.S. 775 (1978) ............ ....... ............. 18

Fullilove v. Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980) ...........passim

Hampton v. Mow Sun Wong, 426 U.S. 88 (1976).. 13

Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, 379

U.S. 241 (1964) ________ _________ _________ ____ 3

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 480 U.S. 616

(1987)......... - ................ - ..... - ___________ ___ _______ 24

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968) _________ 3

Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S. 294 (1964)____ 3

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641 (1966)___ 3,10 ,16

Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ International

Association v. EEOC, 478 U.S. 421 (1986)....... 24

Main Line Paving Co. v. Philadelphia Board of

Education, 725 F. Supp. 1349 (E.D. Pa. 1989).. 24

Morrison v. Olson, 108 S. Ct. 2597 (1988).......... 13

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973) .............. 10

Oregon v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112 (1970) .............. 3 ,14

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367

(1969) ............. .......... .............................. ....... ... 24

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978)______________ _______15,18,19, 21

Sable Communications of California, Inc. v. FCC,

109 S. Ct. 2829 (1989)............... ........ ..................... 19

Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 Howard) 393

(1857) ...................................................................... 8

iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Shurberg Broadcasting of Hartford, Inc. v. FCC,

876 F,2d 902 (D.C. Cir. 1989), cert, granted

sub nom. Astroline Communications Co. v.

Shurberg Broadcasting of Hartford, Inc., 110

S. Ct. 715 (1990)------ --------------------- ---- -----------22, 23, 24

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966) .............. ...... ...................... -.......... ............. -..... 3

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh,

Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) .... ....— ...............- 9,11

United States v. Guest, 363 U.S. 745 (1966)------- 10

United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149 (1987)-.- 18

Winter Park Communications, Inc. v. FCC, 873

F.2d 347 (D.C. Cir. 1989), cert, granted sub

nom. Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 110

S. Ct. 715 (1990) ......... ..................... .......... .......... 20, 23, 24

Wygant v. Jackson Board of Education, 476 U.S.

267 (1986) ________________ _______________17,18,23,24

LEGISLATIVE, STATUTORY AND REGULATORY

M ATERIALS:

42 U.S.C. § 1981......... - .................................................... 12:

42U.S.C. § 1982— ............... -....... -......... -......... -...... ----- 12

42 U.S.C. § 1983------------------------- - -------------------------- 12

Civil Rights Act of 1957, Pub. L. No. 85-315, 71

Stat. 634 ........ .......... ....... - ............................................ 12

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78

Stat. 241 -.....-....... -....-.....-............................................ 12

Civil Rights Act of 1968, Pub. L. No. 90-284, 82

Stat. 8 1 ________________ _________ ----------- ------- ----- 12

Civil Rights Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976,

Pub. L. No. 94-559, 90 Stat. 2641 ---------------------- 12

Emergency School Aid Act of 1978, Pub. L. No.

95-561, 92 Stat. 2252 _______ ___-.............-----.......... 12

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub.

L. No. 92-261, 86 Stat. 103 ------------ ----- -...... ......... 12,14

Fair Housing Act Amendments of 1988, Pub L.

No. 100-430, 102 Stat. 1619 ...............................- - - 12,14

H.R. Conf. Rep. No. 765, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

(1982)-.....................- ....................................................

Pub. L. No. 97-259, 96 Stat. 1087 (1982).................... 16

Pub. L. No. 100-202,101 Stat. 1329 (1987)............. 4

Pub. L. No. 100-459,102 Stat. 2186 (1988) ............. 4

Pub. L. No. 101-162,103 Stat. 1020 (1989).............. 4

Statement on Policy on Minority Ownership of

Broadcasting Facilities, 68 F.C.C.2d 979 (1978).. 26

Surface Transportation and Uniform Relocation

Assistance Act of 1987, Pub. L. No. 100-17,

101 Stat. 132 ........................ .................................. ... - 12

Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79

Stat. 43 7 ........ ......... ....... .......................... ............... ..... 12

Voting Rights Act Amendments of 1982, Pub. L.

No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 131 ..... ...................................... 12,14

MISCELLANEOUS AUTHORITIES:

Ackerman, Constitutional Politics/Constitutional

Law, 99 Yale L.J. 453 (1989) .........................H

American Council on Education and the Education

Commission of the States, One-Third of a Na

tion: A Report of the Commission on Minority

Participation in Education and American Life

(1988) ----------------- -------------- ------------------------- ------- 5

B. Blauner, Black Lives, White Lives: Three Dec

ades of Race Relations in America (1989)____ 5

Committee on the Status of Black Americans, A

Common Destiny: Blacks in American Society

(1989) _______________ ___________________________ 5, 6

R. Dahl, Democracy and Its Critics (1989) — ....... 11

The Federalist No. 10 (J. Madison)......... ................... 11,12

The Federalist No. 51 (J. Madison) ................... 11,12

K. Karst, Belonging to America: Equal Citizen

ship and the Constitution (1989) ............ ......... . 6

The Mexican American Experience: An Interdis

ciplinary Anthology (R. de la Garza ed. 1985).... 5

G. Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro

Problem and Modern American Democracy

(1944)----------- ---------------------- --------------- --------------- 6

Report of the National Advisory Commission on

Civil Disorders (1968)..................—......................... 6, 21

iv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

V

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

T. Sowell, The Economics and Politics of Race

(1983)............................... 20

Sunstein, Interest Groups in American Public

Law, 38 Stan. L. Rev. 29 (1985) ........................... 11

L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law (2d ed.

1988) ....... 11

United States Department of Commerce, Statisti

cal Abstract of the United States (1989) .......... 5

United States Commission on Civil Rights, Win

dow Dressing on the Set: Women and Minori

ties in Television (1977)______________ ____ ____ 21

C. Wilkinson, American Indians, Time and the

Law: Native Societies in a Modern Constitu

tional Democracy (1987) ......................................... 5

W. Wilson, The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner

City, the Underclass and Public Policy (1987) 5

In The

Bnpxmvx GJmirt itf % Untteft BMxb

October Term, 1989

No. 89-453

Metro Broadcasting, Inc.,

Petitioner,v.

Federal Communications Commission, et al.,

__________ Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia Circuit

BRIEF OF LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW AS

AMICUS CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

is a nonprofit organization established in 1963 at the re

quest of the President of the United States to involve

leading members of the bar throughout the country in a

national effort to insure civil rights to all Americans.

Through its national office in Washington, D.C., and its

several affiliate Lawyers’ Committees, such as the Wash

ington, D.C., Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law, the organization has over the past 27 years en

listed the services of thousands of members of the private

bar in addressing the legal problems of minorities and

the poor in voting, education, employment, housing, mu

2

nicipal services, the administration of justice, and law

enforcement.1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Racial and ethnic discrimination continues to impose

significant barriers to the opportunities of minorities

throughout our society. Congress has unique power and

competence to identify and remedy the effects of this soci

ety-wide discrimination, and should be given latitude to

utilize racial preferences where it concludes they are ap

propriate. This congressional power stems in large meas

ure from the Reconstruction era amendments, which gave

Congress preeminent authority over matters of race and

entrusted Congress to enforce the constitutional guaran

tees of equality.

In this case, Congress has confronted the tangible

present-day effects of society-wide discrimination on the

vitally important broadcast industry. It has concluded

that this discrimination has resulted in the virtual absence

of minorities from the ranks of owners of broadcast li

censes, which in turn has practically excluded minority

viewpoints from the airwaves. In addition to the interest

in remedying discrimination for its own sake, Congress

has a substantial interest in promoting a diversity of

perspectives in broadcasting. And, Congress has good

reason to believe that a minority preference policy in

awarding broadcast licenses will in fact enhance diversity

in broadcasting. This diversity interest further supports

Congress’ use of racial preferences.

Congress’ action is entitled to substantial deference by

this Court. Although there must be judicial review of the

factual support underlying any race-based measure, here

that review must take into account Congress’ wealth of

experience in addressing the problems of discrimination

and its familiarity with the realities and complexities of

1 The parties have consented to the filing- of this brief. Letters

of consent are on file with the Clerk of the Court.

3

the broadcasting industry. Similarly, while the minority

preference should be narrowly tailored to its objectives,

Congress must have leeway in its choice of means. It

should be permitted to employ group remedies that do not

require its beneficiaries to prove they are “victims” of

discrimination, and that place some burden on nonminori

ties without upsetting firmly rooted expectations.

ARGUMENT

This case concerns the power of Congress to respond to

problems caused by racial and ethnic discrimination in

our society. The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

Under Law believes that Congress has unique competence

to identify these problems and must be given the neces

sary latitude to address them. This principle was at the

core of a series of landmark decisions more than two

decades ago in which this Court upheld sweeping federal

legislation designed to combat society-wide discrimination

against racial and ethnic minorities.2 It was also this

principle that guided this Court’s decision in Fullilove v.

Klutznick, 448 U.S. 448 (1980), upholding Congress’ de

2 See Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 442-43 (1968)

(42 U.S.C. § 1982 intended to address society-wide racial discrimi

nation that was “ herd[ing] men into ghettos and mak[ing] their

ability to buy property turn on the color of their skin” ) ; Katzen-

bach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. 641, 652-53 (1966) (section 4(e) of

Voting Rights Act designed to guarantee equal rights to all Ameri

cans) ; South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 309 (1966)

(Voting Rights Act deemed appropriate response to the “ insidious

and pervasive evil” of racism) ; Katzenbach v. McClung, 379 U.S.

294, 301 (1964) (characterizing the racial discrimination pro

hibited by Title III of 1964 Civil Rights Act as a problem of “na

tionwide scope” ) ; Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States,

379 U.S. 241, 257 (1964) (describing society-wide discrimination

as “ a moral problem” with “ disruptive effects” ) ; see also Oregon

v. Mitchell, 400 U.S. 112, 133 (1970) (opinion of Black, J.) (since

racial and ethnic discrimination is “a serious national dilemma that

touches every corner of our land,” Congress has power to “ deal

with [this problem] with nationwide legislation” ).

4

termination that in order to redress the lingering effects

of past racial and ethnic discrimination on public con

tracting, it was necessary to take the race and ethnicity

of contractors into account.

This principle of congressional competence carries even

greater force in this case, because here Congress is ad

dressing the consequences of past racial and ethnic dis

crimination in an area of vital national concern— broad

casting-over which it traditionally has exercised broad

oversight.3 Congress has concluded that the virtual ab

sence of minorities from the ranks of owners of broadcast

licenses is a result of past society-wide discrimination,

and has limited the diversity of perspectives conveyed

over the nation’s airwaves.4 The preference granted to

minorities in comparative licensing proceedings reflects a

considered response on the part of Congress to this deeply

vexing problem.5 We urge the Court to uphold it.

3 See FCC v. League of Women Voters, 468 U.S. 364, 376-77

(1984) (Court has “ long- recognized” that Congress must have

ability to regulate “ scarce and valuable resource” of broadcast

licenses and “ seek to assure that the public receives . . . a balanced

presentation of information on issues of public importance” ) ; CBS

v. Democratic Nat’l Comm., 412 U.S. 94, 103 (1973) (Court must

review challenges to broadcast regulation mindful of Congress’ ex

tensive role in “ the development of our broadcast system [for]

over [a] half century” ).

4 Some defenders of the minority preference policy have argued

that its objective is not to remedy the effects of past discrimination,

but rather to serve the “ non-remedial” objective of promoting a

diversity of perspectives in broadcasting. While the policy does

have this diversity objective, see infra Part II, its “non-remedial”

elements cannot be divorced from the remedial elements. For if not

for past discrimination, there would be no need to take affirmative

steps to increase minority ownership of broadcast licenses as a

means of increasing the diversity of perspectives to which the tele

vision and radio audience is exposed.

5 Congress clearly has acted here. After holding a series of hear

ings between 1982 and 1987 on minority ownership of broadcast

licenses, Congress ordered the FCC to continue granting a minority

5

I. CONGRESS M AY USE MINORITY PREFERENCES

TO REMEDY THE PRESENT EFFECTS OF SOCI

ETY-WIDE DISCRIMINATION ON BROADCAST

ING

A. Congress Must Be Allowed to Remedy the Conse

quences of Society-Wide Discrimination Through

Race-Conscious Measures

Our nation still suffers from the legacy of racial dis

crimination. In many sectors of our society, the gaps be

tween minorities and nonminorities are enormous.6 While

other factors also may be at work, society-wide discrimi

nation is responsible, in large part, for our failure to re

solve what in 1944 Gunnar Myrdal labeled the “ American

preference in comparative proceedings. That directive, which came

in the 1987 appropriations bill, passed both the House of Repre

sentatives and the Senate, and was signed into law by the Presi

dent. See Pub. L. No. 100-202, 101 Stat. 1329-31 (1987). Congress

issued similar directives to the FCC in the 1988 and 1989 appro

priations bills. See Pub. L. No. 100-459, 102 Stat. 2186, 2216-17

(1988) ; Pub. L. No. 101-162, 103 Stat. 1020 (1989). Together, the

three measures demonstrate that the minority preference policy is

one that is mandated by Congress.

6 The evidence of continuing discrimination-related disparities be

tween the races is by now disturbingly familiar: Minorities are

disproportionately trapped in the cycle of poverty and crime that

grips our inner cities; their educational achievements lag far behind

those of nonminorities; and they are far more likely to feel

alienated from, and disillusioned with, our nation’s political and

social institutions. See, e.g., B. Blauner, Black Lives, White Lives:

Three Decades of Race Relations in America (1989); C. Wilkinson,

American Indians, Time and the Law: Native Societies in a Modern

Constitutional Democracy (1987); W. Wilson, The Truly Disadvan

taged: The Inner City, the Underclass and Public Policy (1987);

The Mexican American Experience: An Interdisciplinary Anthology

(R. de la Garza ed. 1985); Committee on the Status of Black

Americans, A Common Destiny: Blacks in American Society

(1989) ; American Council on Education and the Education Com

mission of the States, One-Third of a Nation: A Report of the

Commission on Minority Participation in Education and American

Life (1988); U.S. Dept, of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the

United States, Tables 634, 747 (1989).

6

Dilemma.” 7 Congress must be permitted to address the

present-day consequences of past society-wide discrimina

tion, through race-conscious measures if appropriate.

1. Past society-wide discrimination has concrete

effects today that Congress must have latitude

to address

Where society-wide discrimination has resulted in spe

cific identifiable problems— in this case, a virtual absence

of minority broadcasters and an accompanying lack of

diversity in broadcasting— it is not an “ amorphous” con

cept that is “ ageless in its reach into the past.” 8 Rather,

it is a concrete, tangible phenomenon that continues to

haunt us. In view of the formidable barriers that society

wide discrimination still poses to the opportunities of

minorities, “ Congress properly may— and indeed must—

address directly the problems of discrimination in our

society,” and in some situations must be able to do so

through race-conscious means.9

7 G. Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and

Modern American Democracy (1944). As a report released by the

National Research Council only last year conclusively demonstrates,

Myrdal’s label is, unfortunately, still an apt one. See A Common

Destiny, supra note 6, at 5 ( “ legacy of discrimination and segrega

tion” continues to hinder attempts by black Americans to “remov[e]

barriers” to full participation in society). That report also reveals

the persistence of the problems that were described in the seminal

1968 Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Dis

orders [hereinafter “Kerner Commission Report” ]. See also K.

Karst, Belonging to America: Equal Citizenship and the Constitu

tion ch. 9 (1989) (past discrimination is contributing factor to the

condition of minorities who constitute a disproportionate percentage

of the marginalized poor in America).

s City of Richmond v. J.A. Croson Co., 109 S. Ct. 706, 723 (1989)

(quoting Regents of Univ. of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 307

(1978) (opinion of Powell, J .)).

9 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 499 (Powell, J., concurring). See id. at

482 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) ( “ [w]e reject the contention that in

the remedial context Congress must act in a wholly ‘color-blind’

fashion” ).

7

Like this case, Fullilove involved congressional action

to remedy a problem in an important industry, public con

tracting, caused by the continuing effects of past discrimi

nation. In adopting the race-conscious measure at issue

there, Congress concluded that existing race-neutral pro

curement practices were resulting in the ‘ ‘'perpetuation

of the effects of prior discrimination which had impaired

or foreclosed access by minority businesses to public con

tracting opportunities.” 448 U.S. at 473 (opinion of

Burger, C.J.).10 Notably, these were “ barriers to com

petitive access which had their roots in racial and ethnic

discrimination, and which continue today, even absent

any intentional discrimination or other unlawful con

duct.” Id. at 478 (opinion of Burger, C.J.). Because

race-neutral action only reinforced a racially skewed

system of contracting, Congress decided that race

conscious action was appropriate to overcome the legacy

of discrimination.

Last term’s decision in Croson reaffirmed that Congress

may predicate race-conscious action on the need to cure

the identified present-day consequences of past society-

wide discrimination. The plurality declared that while

state and local governments may use race-conscious meas

ures only to remedy identified discrimination in particular

sectors and industries within their jurisdictions, Congress

may do so to “ redress the effects of society-wide discrimi

nation.” 11

10 See Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 505-06 (Powell, J., concurring) (past

discrimination, which was not “ identified with . . . exactitude,” had

effects that were being perpetuated by present procurement prac

tices) ; id. at 520 (Marshall, J., concurring) (“ present effects of

past racial discrimination” continued to impair access of minority

businesses to public contracting opportunities); see also Croson,

109 S. Ct. at 718 (plurality opinion) (Congress’ action in Fullilove

was predicated on belief that the “ effects of past discrimination

had impaired the competitive position of minority businesses” ).

11 Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 719. This reaffirmation of Fullilove is

not acknowledged by the Department of Justice. Nowhere does it

come to grips with the fact that, unlike the City of Richmond,

8

While it may be true that in the short run the use of

racial and ethnic preferences to remedy the effects of past

society-wide discrimination “carries a danger of stigmatic

harm,” 12 13 in the long run minority preferences are de

signed in part to overcome stigma. Stigma is, after all,

an intended product of discrimination: “ [I]t is hardly

consistent with the respect due to these States, to suppose

that they regarded . . . as fellow-citizens and members of

the sovereignty, a class of beings whom they had thus

stigmatized; whom, as we are bound, out of respect to the

State sovereignties, to assume they had deemed it just

and necessary thus to stigmatize, and upon whom they

had impressed such deep and enduring marks of inferior

ity and degradation.” Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S.

(19 Howard) 393, 416 (1857).13 Stigma continues to this

day. In employing minority preferences, Congress has

concluded that ultimately, stigma can only be overcome

by more minorities performing in positions of consequence

and thereby breaking down stereotypes and dispelling

prejudices that were formed by stigma in the first place.

Congress may tackle society-wide discrimination through race-based

measures. Instead, the Department of Justice injects the Croson

limitations on state and local government action into this case and

condemns Congress for failing to have identified discrimination

with the degree of particularity that this Court required of the

City of Richmond. The questions that the Department of Justice

poses—whether there was any evidence of prior discrimination

against minorities by the FCC or in the broadcasting industry—

are the wrong ones to be asking here. See Brief of the United

States as Amicus Curiae Supporting Petitioner at 20-21 [herein

after “ Brief of U.S.” ] .

1:2 Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 721. Here, though, there is very little

danger of stigmatic harm, since minorities must meet basic financial

qualifications and the other qualifications for a broadcast license

are unrelated to “ merit.”

13 See also Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483, 494 (1954)

(“ To separate them from others of similar age and qualifications

solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority as to

their status in the community that may affect their hearts and

minds in a way unlikely ever to be undone” ) .

9

2. The Constitution gives Congress the unique

power to address the consequences of society

wide discrimination

Congress has unique power to remedy the consequences

of society-wide discrimination, and its judgments about

how to exercise that power are entitled to deference. Con

gress’ special authority in matters of race derives, in large

part, from the positive grant of legislative power that it

enjoys pursuant to the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fif

teenth Amendments, all of which were adopted during the

post-Civil War Reconstruction era.14

As this Court stated in Croson, the Reconstruction era

amendments “worked a dramatic change in the balance

between congressional and state power over matters of

race.” 15 The amendments firmly established that Con

gress is the political institution uniquely competent to

address society-wide problems related to racial discrimina

tion, problems of national dimension. Having lived

through the discord of the Civil War, the architects of the

amendments were suspicious of local government when it

came to race, and thus “ limit [ed] the power of the states

and enlarged] the powers of Congress” so as to unify

the nation again. Ex parte Virginia, 100 U.S. 339, 345

(1879).

Consequently, as this Court has recognized, “ in no

organ of government, state or federal, does there repose

a more comprehensive remedial power than in the Con

gress, expressly charged by the Constitution with com

petence and authority to enforce equal protection guaran

14 As Chief Justice Burger pointed out in Fullilove, Congress may

also address the effects of society-wide discrimination under its

Commerce and Spending Powers. Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 475-76.

15 Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 719. See id. at 736 (Scalia, J., concur

ring) (Congress’ powers “concerning matters of race were ex

plicitly enhanced by the Fourteenth Amendment” ) ; see also United

Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

(1977) (under Fifteenth Amendment Congress can compel states to

take action to ensure guarantees of full citizenship).

10

tees.” Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 483 (opinion of Burger,

C.J.). Congress’ remedial power is not restricted to situa

tions where state action has violated the Constitution.

The enforcement provisions of the Reconstruction era

amendments not only authorize Congress to ensure that

states comply with the principles of equality, but also to

“ define situations . . . that threaten [those] principles

. . . and to adopt prophylatic rules to deal with those

situations.” 16

These prophylactic rules may be race-based. In Fulli

love, Congress had determined that the existing govern

ment contract procurement system perpetuated the ef

fects of past discrimination and denied minorities equality

under the law. This Court held that Congress could pre

16 Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 719. See Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S.

at 648-50; see also City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 177

(1980) (Congress could adopt rule barring certain state conduct

with respect to voting as a means of promoting purposes of Fif

teenth Amendment, even where state arguably had not violated the

Amendment).

Nevertheless, the Department of Justice insists that “ unlawful”

state action must be implicated before Congress can legislate under

section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, and from there argues

that there is no such action here since broadcast licensing only

involves the federal government, not the states. Brief of U.S. at 18

n.10. But even assuming that unlawful state action is required,

the Department of Justice’s argument is wrong, for it was states

that perpetrated and tolerated much of the society-wide discrimina

tion that is to be remedied here. In any event, the question of the

existence of state action—lawful or unlawful— is academic. Con

gress clearly can address problems of race relations under the

Thirteenth Amendment and the Commerce Clause, both of which

apply to purely private as well as state action. See Fullilove, 448

U.S. at 475 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) (approving remedial legisla

tion that affected private conduct under Congress’ Commerce

Power) ; Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455, 470 (1973) (private

discrimination subject to remedial legislation under section 2 of

Thirteenth Amendment). Furthermore, Congress may be able to

remedy private discrimination under section 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment. See United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966);

Katzenbach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. at 652-53.

11

scribe a race-conscious remedy even absent proof of un

lawful discrimination by the states.17 In this case, as we

will show in Part IB, the existing broadcast licensing

system also perpetuates the effects of past society-wide

discrimination. Here too, Congress has the power to use

racial preferences to address the problem.

The shifting of power from the states to the national

government after the Civil War embodied in part the

republican political theory expounded by James Madison

and others.18 Madison feared that parochial interests and

factionalism, particularly at the local level, would subvert

the democratic process and the proper operation of govern

ment.19 His solution was a national legislature that would

rise above the fray of local factions and deliberate matters

of national dimension. It would, of course, operate with

checks and balances so as to limit the power of its own

factions and even of its majority.20 The House of Repre

17 See Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 478 (opinion of Burger, C .J.); see

also UJO v. Carey, 430 U.S. at 155 (Congress could require states

to act on the basis of race to secure Fifteenth Amendment guaran

tees).

18 See L. Tribe, American Constitutional Law 2-7 (2d ed. 1988)

(Reconstruction era amendments reflected Madison’s theory that

national government would he more likely to protect individual

liberties than local government); Ackerman, Constitutional Poli

tics /Constitutional Law, 99 Yale L.J. 453, 508-09 (1989) (Recon

struction era amendments, which “gave a new primacy to our na

tional institutions” at the expense of local ones, carried out inten

tion of republican political theorists); see also Croson, 109 S. Ct.

at 736 (Scalia, J., concurring) (“ [a] sound distinction between

federal and state (or local) action based on race rests not only on

the substance of the Civil War Amendments, but upon social reality

and governmental theory” ) .

19 The Federalist No. 10, at 77-78 (J. Madison) (C. Rossiter ed.

1961). See also R. Dahl, Democracy and Its Critics 218 (1989);

Sunstein, Interest Groups In American Public Law, 38 Stan. L. Rev.

29, 39-45 (1985).

20 See The Federalist No. 10, at 82-83; The Federalist No. 51,

at 322-23 (J. Madison) (C. Rossiter ed. 1961).

12

sentatives and the Senate would act as checks on each

other; together, they would “ discern the true interests of

the [] country,” and promulgate legislation expressing the

national will without sacrificing justice to “ temporary or

partial considerations.” 21

Over the past three decades, Congress has identified a

national interest— indeed a commitment— in eradicating

discrimination and its effects. Through a wide array of

legislation, it has acted to fulfill that commitment.22 The

21 The Federalist No. 10, at 82. See also Brown v. Hartlage, 456

U.S. 45, 56 n.7 (1982) ( “ [i]n the extended republic of the United

States, and among the great variety of interests, parties and sects

which it embraces, a coalition of a majority of the whole society

could seldom take place on any other principles than those of justice

and the general good” ) (quoting The Federalist No. 51, at 325).

In Croson, Justice Scalia stressed that it is consistent with the

republican vision of government to trust Congress on matters of

race. He explained:

[Rjaeial discrimination against any group finds more ready

expression at the state and local level than at the federal level.

To the children of the Founding Fathers, this should come as

no surprise. An acute awareness of the heightened danger of

oppression from political factions in small, rather than large,

political units dates to the very begining of our national his

tory.

109 S. Ct. at 737 (Scalia, J., concurring).

22 See, e.g., Civil Rights of 1957, Pub. L. No. 85-315, 71 Stat.

634 (codified at 5 U.S.C. § 535(19) et seq.) ; Civil Rights Act of

1964, Pub. L. No. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241 (codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000a

et seq.) ; Voting Rights Act of 1965, Pub. L. No. 89-110, 79 Stat.

437 (codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 1971 et seq. ) ; Civil Rights Act of 1968,

Pub. L. No. 90-284, 82 Stat. 81 (codified at 18 U.S.C. §§ 231 et seq. ) ;

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L. No. 92-261,

86 Stat. 103 (codified at 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000 et seq. ) ; Civil Rights

Attorney’s Fees Awards Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-559, 90 Stat.

2641; Emergency School Aid Act of 1978, Pub. L. No. 95-561, 92

Stat. 2252 (codified at 20 U.S.C. § 3191-3207); Voting Rights Act

Amendments of 1982, Pub. L. No. 97-205, 96 Stat. 131 (codified at

42 U.S.C. §§ 1971 et seq.) ; Surface Transportation and Uniform

Relocation Assistance Act of 1987, Pub. L. No. 100-17, 101 Stat. 132;

Fair Housing Act Amendments of 1988, Pub. L. No. 100-430, 102

minority preference policy at issue in this case is part of

this overall effort.

B. Congress Had Sufficient Factual Support for the

Minority Preference Policy

This Court has made it clear that race-based remedial

action must have sufficient factual support. In this case

that requirement is satisfied, as Congress had ample basis

to believe that historical patterns of discrimination have

resulted in an almost complete absence of minorities as

owners of broadcast licenses.

Although judicial review of the factual support for race-

based action must always be searching, where Congress

has acted appropriate deference is in order,23 even when

fundamental rights are at stake.24 While Congress may

not simply presume that society-wide discrimination has

had effects that need to be remedied, the facts on which

Congress predicates its action need not be found with the

same specificity and precision that this Court demands of

states and cities, and need not be compiled in formal find

ings.25 26 Moreover, when considering the record underly

Stat. 1619; see also 42 U.S.C. § 1981; 42 U.S.C. § 1982; 42 U.S.C.

§ 1983.

23 Mindful that an act of Congress was at issue in Fullilove,

Chief Justice Burger acknowledged that this Court was assuming

“the gravest and most delicate duty that [it] is called on to per

form,” Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 472 (quoting Blodgett v. Holden, 275

U.S. 142, 148 (1927) (Holmes, J .)), and he called for “appropriate

deference.” 7d. at 472. See also Morrison v. Olson, 108 S. Ct. 2597,

2626 (1988) (Scalia, J., dissenting) (the “ harmonious functioning

of the [political] system demands that [this Court] ordinarily give

some deference, or a presumption of validity” to federal legislation).

24 See CBS v. Democratic Nat’l Comm., 412 U.S. at 102 (Court

must approach its review of First Amendment challenge to con

gressional action with “ great delicacy” ). Cf. Hampton v. Mow Sun

Wong, 426 U.S. 88, 103 (1976) (Court generally presumes that

overriding national interest will justify discriminatory rule that is

“expressly mandated by the Congress or the President” ).

26 See Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 502 (Powell, J., concurring) (Con

gress’ role as promulgator of “national rules for the governance of

13

14

ing any federal statute, this Court looks beyond the formal

legislative history, taking into account all relevant infor

mation that was at Congress’ disposal when it acted.26

This approach is particularly appropriate here, since

Congress was not operating on a blank slate. It has legis

lated repeatedly in the area of race relations and “made

national findings that there has been societal discrimina

tion in a host of fields.” Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 727. Be

ginning with the Civil Rights Act of 1957, which created

both the United States Civil Rights Commission and the

Civil Rights Division of the Department of Justice, and

continuing to the present, Congress has passed significant

legislation addressing the problems of racial discrimina

tion that have affected the country.* 26 27 This legislation is

routinely the subject of oversight hearings and is regu

larly amended better to achieve its purposes.28 This long,

difficult, and frustrating process has made Congress

aware of what has worked, what has not worked, and

what needs to be tried. It has acquainted Congress with

those areas of our society that are especially unaffected

by mere antidiscrimination measures. It should be un

our society simply does not entail the same concept of record-making

that is appropriate to a judicial or administrative proceeding” ) ; id.

at 478 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) (“ Congress, of course, may legislate

without compiling the kind of ‘record’ appropriate with respect to

judicial or administrative proceedings” ) ; cf. Oregon v. Mitchell,

400 U.S. at 284 (Stewart, J., concurring in part and dissenting in

part) (compared to local legislatures, “ Congress may paint with

a much broader brush” ) .

26 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 503 (Powell, J., concurring) (Congress’

“ special attribute lies in its broader mission to investigate and

consider all facts and opinions that may be relevant to the resolu

tion of an issue” ).

27 See supra note 22.

28 See, ,e.g., Equal Opportunity Act of 1972, supra note 22 (ex

tending reach of Title VII of 1964 Civil Rights A c t ) ; Voting Rights

Act Amendments of 1982, supra note 22 (extending reach of Voting

Rights Act of 1965); Fair Housing Act Amendments of 1988,

supra note 22 (extending reach of Fair Housing Act of 1968).

15

necessary for Congress to redocument the fact and his

tory of discrimination every time it contemplates enacting

another law.29

Congress’ experience in addressing the problems of

racial discrimination was complemented in this case by its

familiarity with the workings of the broadcasting indus

try. When it directed the FCC to continue implementing

the minority preference policy in comparative proceedings,

Congress already knew that most of the licenses were

initially awarded— at bargain basement rates— at a time

when minorities were effectively excluded from the

bidders’ table by discrimination that was pervasive and

officially sanctioned in many parts of the country.30

It already knew that today the central barrier to enter

broadcasting is an economic one, the need for sub

stantial risk capital. It already knew that this barrier

has had a disproportionate impact on minorities largely

attributable to society-wide discrimination. And, Congress

also knew that because the broadcasting industry is a

mature one, and the frequency spectrum already well

saturated, the most inexpensive way to acquire a license

is through the comparative hearing process.31

29 See Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 503 (Powell, J., concurring-) (in

light of the “ information and expertise that [it has] acquirefd]

in the consideration and enactment of earlier legislation,” Congress

should not be required “to make specific factual findings with

respect to each legislative action” it takes in the area).

30 See Bakke, 438 U.S. at 393-94 (opinion of Marshall, J.) (in all

walks of life, “ [t]he enforced segregation of the races continued

into the middle of the 20th century” and was not “ limited solely

to the Southern States” ).

S:1 The Department of Justice asserts that approximately 9% of

all existing broadcast licenses change hands in any given year.

Brief of U.S. at 21 n.12. But unlike at the outset of FCC licensing,

radio and television stations today are not being given away for

almost nothing; they are sold at significant premiums that derive

from the increased value of broadcast stations over time. Having

been excluded from the market when licenses were virtually free,

16

Viewed against that backdrop, the minority preference

in comparative proceedings has sufficient factual support.

To ignore Congress’ substantial experience in confronting

the consequences of racial discrimination and in deciding

how best to allocate broadcast licenses is to “blind [one

self] to the realities familiar to the legislators.” Katzen-

bach v. Morgan, 384 U.S. at 653.32

II. THE INTEREST IN PROMOTING DIVERSITY OF

PERSPECTIVES IN BROADCASTING FURTHER

SUPPORTS THE USE OF MINORITY PREFER

ENCES IN LICENSING

While Congress has a strong interest in remedying soci

ety-wide discrimination for its own sake, there is even a

stronger public interest in remedial action that simultane

ously serves other important goals. In this case, Congress

determined that society-wide discrimination not only has

resulted in the virtual absence of minority license owners

in the broadcast industry, but that this in turn has had

a significant deleterious effect on the diversity of perspec

tives reflected in broadcasting. The minority preference

policy thus serves both the purely “backward-looking” in-

and stations were built at cost, minorities are now being shut out

because price tags are prohibitive. The minority preference policy

applies only to the allocation of new licenses for new stations, not

the licenses for existing stations that are being transferred at

exorbitant rates each year. As such, the policy enables minorities

to break into the industry on terms comparable to those on which

nonminorities entered when broadcast licensing first began.

82 The Department of Justice contends that the 1982 amendments

to the Communications Act, which authorized the FCC to grant a

preference to minorities in the random award of licenses through

lotteries, have no bearing on the similar preference granted in com

parative proceedings. Brief of U.S. at 19 n.U. Yet the very legisla

tive history of the 1982 amendments that the Department of Jus

tice cites refers back to the reports and studies on which the FCC

initially predicated the comparative proceeding preference. See

Pub. L. No. 97-259, 96 Stat. 1087, 1094 (1982) (codified at 47 U.S.C.

§ 309(1) (3 ) (A ) ) ; H.R, Conf. Rep. No. 765, 97th Cong., 2d Sess.

43-45 (1982).

17

terest of remedying past wrongs and the “ forward-

looking” interest of promoting diversity in broadcasting.

This diversity interest is substantial and further supports

the policy.

A. Forward-Looking Interests May Support the Use

of Racial Preferences

This Court repeatedly has stated that the use of racial

preferences may be justified only by a weighty govern

mental interest.33 34 As the Court’s previous decisions indi

cate, in most cases that interest will be a purely remedial

one. However, there is no reason that a forward-looking

interest cannot suffice, and the Court has never so held.84

33 Although that interest must be “compelling” in the case of a

state or local government program, see Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 721,

the precise standard applicable to a congressional program is not

clear. In Fullilove, Justice Marshall (joined by Justices Brennan

and Blackmun) stated that this interest must be “ important,” 448

U.S. at 519, Justice Powell used “ compelling,” id. at 496, and Chief

Justice Burger’s plurality opinion stated that the objective served

by the program need only be “within the powers of Congress.” Id.

at 473.

34 There is language in Croson that could be interpreted as limit

ing the use of racial preferences to remedial contexts. See Croson,

109 S. Ct. at 721 (“ [ujnless [racial classifications] are strictly

reserved for remedial settings, they may in fact promote notions of

racial inferiority and lead to politics of racial hostility” ). However,

because the racial preference at issue in Croson was defended only

on remedial grounds, the Court had no occasion to and did not

decide whether forward-looking justifications might have sufficed.

Moreover, construing Croson to preclude forward-looking justifica

tions is at odds with Justice O’Connor’s acknowledgement that

interests other than remedying past discrimination might be suffi

ciently important to support race-conscious action. Wygant v. Jack-

son Bd. of Educ., 476 U.S. 267, 286 (1986) (O’Connor, J., con

curring) ( “And certainly nothing the Court has said today neces

sarily forecloses the possibility that the Court will find other gov

ernmental interests which have been relied upon in the lower courts

but which have not been passed on here to be sufficiently ‘important’

or ‘compelling’ to sustain the use of affirmative action policies” ).

18

To the contrary, several Justices have acknowledged

that the use of racial preferences might be supported by

an important governmental interest other than remedying

discrimination.35 These Justices recognized that in some

contexts race-conscious action fosters values other than

compensating minorities for past discrimination, and can

“produce tangible . . . future benefits.” Croson, 109 S. Ct.

at 731 n.l (Stevens, J., concurring).

This case involves another context in which race is rele

vant for reasons above and beyond remedying past dis

crimination. As explained in the following sections, the

minority preference at issue serves the important for

ward-looking interest of promoting the diversity of per

spectives reflected in broadcasting.

B. The Promotion of Diversity of Perspectives in

Broad casing Is a Substantial Interest

The promotion of diversity of viewpoints in broadcast

ing is a substantial governmental interest. It is central

to the values embodied in the First Amendment, and has

always guided the allocation of broadcast licenses.36

The goal of diversity in broadcasting is at least as im

portant as the goal of diversity in higher education, which

Justice Powell, writing in Bakke, found sufficiently

35 See Bakke, 438 U.S. at 311-15 (opinion of Powell), J . ) ; Wygant,

476 U.S. at 286 (O’Connor, J., concurring); id. at 313-14 (Stevens,

J., dissenting); Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 730 & n.l (Stevens, J., con

curring) ; cf. United States v. Paradise, 480 U.S. 149, 167-68 n.18

(1987) (plurality opinion).

36 The “ public interest” standard that guides FCC decision

making “necessarily invites reference to First Amendment prin

ciples . . . and, in particular, to the First Amendment goal of

achieving ‘the widest possible dissemination of information from

diverse and antagonistic sources.’ ” FCC v. National Citizens Comm,

for Broadcasting, 436 U.S. 775, 795 (1978) (quoting CBS v. Demo

cratic Nat’l Comm., 412 U.S. at 122 and Associated Press v. United

States, 326 U.S. 1, 20 (1945)).

19

weighty to support race-conscious admissions policies in

public universities. There, Justice Powell concluded that

such action would further the strong First Amendment

interest in promoting a diverse student body, which he

reasoned would enhance a “ robust exchange of ideas.”

438 U.S. at 313. As important as this interest is, it has

direct ramifications only for that portion of our popula

tion that attends college. In contrast, the mass media

reach almost the entire population. For better or worse,

radio and television have a “uniquely pervasive” influence

on American life,37 and play a critical role in educating

the public and promoting the exchange of ideas. There

fore, Congress has good reasons for attempting to ensure

that perspectives reflected through the broadcast media

are not limited or distorted by the continuing effects of

discrimination.

To the extent that there is any doubt about the impor

tance of diversity in broadcasting, that doubt should be

resolved in favor of the choice that Congress has made.

While the Constitution may demand that courts conduct

a searching inquiry to ensure that a racial preference is

supported by a weighty goal, it does not authorize courts

to substitute their own judgments for the considered and

reasonable judgment of Congress. This is particularly

true where, as here, Congress has acted in an area in

which it has substantial power and expertise.

C. Congress Had Sufficient Basis to Link Diversity of

Ownership With Diversity of Perspectives in Broad

casting

The dissent below argued that the minority preference

policy does not support the goal of enhanced diversity in

broadcast programming, because there was no “basis for

believing that minority ownership would lead to ‘minority

programming’ in some sense that is both intelligible and

37 Sable Communications of California, Inc. v. FCC, 109 S. Ct.

2829, 2837 (1989).

20

permissible.” 88 This is incorrect and misses the point

of the policy. Congress had every reason to believe that

the minority preference policy would, in fact, expand the

diversity of perspectives reflected in broadcasting, and not

just in programming. For it is not only programming

but also perspective—which includes considerations other

than simply what show to run or song to play—that is at

the crux of the policy.

When the minority preference policy was begun, broad

casting was basically an all-white industry, as it still is

to a large extent today. This simple fact has had pro

found consequences for the diversity of perspectives re

flected in broadcasting. The inclusion of minority owners

clearly would enhance that diversity. It is not “ stereo

typing” to acknowledge that different racial and ethnic

groups have unique perspectives that may be reflected in

programming choices, selection of station managers, pre

sentation of news, solicitation of advertisers, and commu

nity relations.38 39 It is unrealistic to pretend otherwise.

While in any particular case the proposition may prove

false, in the aggregate the inclusion of minority owners

has to make a difference.

The link between diversity in ownership and diversity

in perspectives may not lend itself easily to empirical

proof, but the Constitution requires only a close relation

ship between means and ends, not a guarantee.40 This is

38 Winter Park Communications, Inc. v. FCC, 873 F.2d 347, 358

(D.C. Cir. 1989) (Williams, J., dissenting), cert, granted sub nom.

Metro Broadcasting, Inc. v. FCC, 110 S. Ct. 715 (1990).

39 Cf. T. Sowell, The Economics and Politics of Race 244 (1983)

( “ [t]he most obvious fact about the history of racial and ethnic

groups is how different they have been— and still are . . .” ).

40 In Bakke, Justice Powell did not require empirical proof that

the admission of minority students to a medical school would in

fact enhance the exchange of ideas or enrich the educational ex

perience of the student body. For him, that common sense proposi

21

particularly true when what is being reviewed is an act

of Congress, which must make predictive judgments of

the type at issue here all the time. The judicial task,

therefore, should be to ensure that Congress had sufficient

reason to believe that the racial preference would serve

its purpose so that “ there is little or no possibility that

the motive for the classification was illegitimate racial

prejudice or stereotype.” Croson, 109 S. Ct. at 721. Here,

Congress had ample reason to believe that including

minority owners in the previously all-white broadcast in

dustry would augment the diversity of viewpoints con

veyed in broadcasting.41

HI. THE m i n o r i t y p r e f e r e n c e p o l i c y s a t i s

f i e s A N Y REASONABLE APPLICATION OF THE

NARROWLY TAILORED TEST

Just as there should be deference to a determination by

Congress that an important interest justifies the use of

race-conscious measures, there should be deference to the

means that Congress selects to serve that interest. For

in both cases, Congress has special competence to act to

tion was enough. He explained that “ [a]n otherwise qualified

medical student with a particular background—whether it be ethnic,

geographic, culturally advantaged or disadvantaged—may bring to

a professional school of medicine experiences, outlooks, and ideas

that enrich the training of its student body and better equip its

graduates to render with understanding their vital service to

humanity.” Bakke, 438 U.S. at 314 (opinion of Powell, J.).

41 Congress did not rely on common sense alone. It had before it

federal government findings on the consequences of having a mass

media dominated by white ownership. See United States Commis

sion on Civil Rights, Window Dressing on the Set: Women and

Minorities in Television 2 (1977) ( “a mass medium dominated by

whites will ultimately fail in its attempts to communicate with an

audience that includes blacks” ) ; Kerner Commission Report, supra

note 7, at 203 ( “ The media report and write from the standpoint

of a white man’s world. . . . This may be understandable, but it is

not excusable in an institution that has the mission to inform and

educate the whole of our society” ).

22

remedy the consequences of discrimination in our society.

Moreover, the choice of means is a peculiarly legislative

function; while a court must review a race-conscious

measure to ensure that it is narrowly tailored to meet its

objective, the court should not substitute its judgment for

the considered judgment of Congress. Indeed, this Court

has stated: “ We are mindful that ‘ [i]n no matter should

we pay more deference to the opinion of Congress than

in its choice of instrumentalities to perform a function

that is within its power.’ ” 42

In this case, Congress’ choice of means satisfies any

reasonable application of the narrowly tailored test. Three

general principles governing the narrowly tailored in

quiry here deserve mention.

First, some burden on nonminorities is permissible. The

dissent below, however, appears to endorse the “ unique

opportunity” approach taken by Judge Silberman in the

Shurberg case, which also is currently before this Court.43

Under that approach, it is unacceptable for a nonminority

to be denied a particular license—a “ unique opportunity

42 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 480 (opinion of Burger, C.J.) (quoting

National Mutual Ins. Co. v. Tidewater Transfer Co., 337 U.S. 582,

603 (1949)). See also Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 480 (opinion of Burger,

C.J.) ( “stress[ing] the limited scope of the Court’s [narrowly

tailored] inquiry” in cases involving “the legislative authority of

Congress” ) ; id. at 515 n.14 (Powell, J., concurring) (narrowly

tailored analysis “vari[es] with the nature and authority of [the]

governmental body” ). Notwithstanding these basic tenets, which

figure prominently in the opinions of Chief Justice Burger and

Justice Powell in Fullilove, the Department of Justice makes the

bold assertion that “ deference is not appropriate in deciding whether

the particular remedy chosen by Congress is ‘narrowly tailored’

. . . .” Brief of U.S. at 15. What is most startling is that the

Department of Justice claims that the opinions of Chief Justice

Burger and Justice Powell support this proposition.

43 Shurberg Broadcasting of Hartford, Inc. v. FCC, 876 F.2d 902,

943 (D.C. Cir. 1989), cert, granted sub nom. Astroline Communica

tions Co. v. Shurberg Broadcasting of Hartford, Inc., 110 S. Ct.

715 (1990).

23

to own a broadcasting station”— because of a minority

preference given to a competitor. Shurberg, 876 F.2d at

917. Judge Silberman claimed that the minority prefer

ence at issue in Shurberg was unconstitutional because

“ [i]t is a Hartford station Shurberg wants and, after all

is said and done, he has been absolutely denied an op

portunity to compete for one merely because of his race.”

Id. at 918. Similarly, the dissent below complained that

“ [h] ere, as in Shurberg, Metro was denied a comparative

hearing on the only new license currently being offered

in the Orlando area.” Winter Park, 873 F.2d at 368

(Williams, J., dissenting).

This approach goes overboard in its attempt to protect

the interests of nonminorities. In any case involving a

minority preference, the plaintiff will always be able to

claim that he did not get a particular thing that he

wanted because of the preference. For example, some non

minority contractors undoubtedly lost out on contracts as

a result of the minority preference program approved in

Fullilove. But, as the Court declared in Fullilove: “ It is

not a constitutional defect in this program that it may

disappoint the expectations of nonminority firms. When

effectuating a limited and properly tailored remedy to

cure the effects of prior discrimination, such a ‘sharing

of the burden’ by innocent parties is not impermissible.” 44

Here, the burden shared by nonminorities is acceptable.

The minority preference is only one consideration in the

comparative hearing process, and does not automatically

preclude nonminorities from acquiring broadcast licenses.

Moreover, a broadcast license does not have the sort of

personal value that demands utmost protection. Unlike

the layoffs of individual teachers at issue in Wygant, no

one’s likelihood is at stake. Nor does the minority pref

44 Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 484 (opinion of Burger, C.J.). See also

Wygant, 476 U.S. at 280-81 (plurality opinion) ( “ [a]s part of this

Nation’s dedication to eradicating racial discrimination, innocent

persons may be called upon to bear -some of the Burden of the

remedy” ).

24

erence policy upset anybody’s “ firmly rooted expecta

tion [s],” 45 since it affects only those who are competing

for broadcast licenses, not those who already own them.

Finally, ownership of a broadcast license has always been

considered a privilege; Congress and the FCC may deny

licenses or place restrictions on license owners as required

by the public interest.46 The failure to obtain such a

privilege could hardly be deemed a substantial burden.

Second, the narrowly tailored test should not require

that minority preferences benefit only minorities who are

shown to be actual “ victims” of discrimination.47 Such a

requirement would be illogical in a case such as this,

where the minority preference serves a goal beyond rem

edying discrimination. But even where a minority pref

erence is purely remedial, the “victims only” requirement

conflicts with this Court’s recognition that minority pref

erences need not be designed to remedy individual cases

of discrimination. Justice O’Connor observed in Wygant:

[T]he Court has forged a degree of unanimity; it is

agreed that a plan need not be limited to the remedy

ing of specific instances of identified discrimination

for it to be deemed sufficiently ‘narrowly tailored,’ or

‘substantially related,’ to the correction of prior dis

crimination . . . .48

As this statement acknowledges, and as Congress has

recognized, group remedies can be appropriate because

45 Johnson v. Transportation Agency, 480 U.S. 616, 638 (1987).

46 See generally Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395 U.S. 367,

386-92 (1969).

47 Some courts have imposed such a requirement. See, e.g.,

Shurberg, 876 F.2d at 912 (opinion of Silberman, J .) ; Main Line

Paving Co. v. Philadelphia Bd. of Educ., 725 F. Supp. 1349, 1361

(E.D. Pa. 1989); see also Winter Park, 873 F.2d at 368 (Williams,

J., dissenting).

48 Wygant, 476 U.S. at 287. Cf. Local 28 of Sheet Metal Workers’

Int’l Ass’n v. EEOC, 478 U.S. 421, 482 (1986) (under Title VII,

court-ordered race-conscious relief need not be limited to actual

victims of discrimination).

25

racial and ethnic discrimination is designed to and has in

fact oppressed and stigmatized groups. Decades of egre

gious discrimination against black people, for example,

has affected all black people. When a black person bene

fits from a minority preference, black people as a group

move one step closer to overcoming the effects of that dis

crimination. Requiring beneficiaries of minority prefer

ences to prove that they personally have been victims of

discrimination simply misses the point of what minority

preferences are trying to remedy.

The argument that minority applicants for broadcast

licenses are well-off and do not need preferences misses

the mark for the same reason. As a group, minorities are

still underrepresented in the pool of qualified applicants

for broadcast licenses, as a result of discrimination. Con

gress determined that without preferences, some minority

applicants will win licenses, but minorities as a group will

still be greatly underrepresented among broadcast owners,

and diversity will suffer. Only the extra push that a pref

erence provides will make up the ground lost by past

discrimination.

Third, Congress must have some discretion in its con

sideration of race-neutral alternatives. As we have ar

gued, Congress has unique power and competence to rem

edy the consequences of society-wide discrimination, and

to decide that race-conscious measures are appropriate.

Of course, where the goals of a race-conscious measure

clearly may be adequately served by race-neutral means,

the race-conscious measure should not be preferred. But

when the efficacy of race-neutral alternatives is not so

clear, Congress should not be stripped of its discretion to

choose how best to implement its remedial policies.49 In

such situations, Congress certainly should not be required

to exhaust race-neutral alternatives before proceeding

with race-conscious action; indeed, such a requirement

49 See Fullilove, 448 U.S. at 508 (Powell, J., concurring) (Con

gress should not be required to choose the least restrictive means

of implementing its goals).

26

was not even imposed on state and local governments in

Croson. See 109 S. Ct. at 728.

In this case, Congress reasonably determined that the

minority preference in comparative proceedings was nec

essary. The policy was adopted only after ten years of

unsuccessful regulatory efforts to rectify the acute under

representation of minority owners in broadcasting.50 This

informed judgment of Congress was reasonable. It is

entitled to deference by this Court.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated herein, the decision of the court

of appeals should be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

John Payton *

Mark S. H ersh

M ichael C. Small

W ilmer, Cutler & P ickering

2445 M Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20037-1420

(202) 663-6000

R obert F. Mullen

David S. Tatel

Co-Chairmen

Norman R edlich

Trustee

Barbara R. A rn w in e

Paul H oltzman

Law yers ’ Committee for

Civil R ights U nder Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

March 6,1990 * Counsel of Record

50 See Statement of Policy on Minority Ownership of Broadcast

ing Facilities, 68 F.C.C.2d 979, 979-80 (1978). Because of First

Amendment restrictions, direct regulation of programming content

would be unconstitutional.

£4 .;^

̂ 1 * ^ * a * *■ Wf HI V£

^ilSst WimmMm^rn..... - ... $mlsmm...Ill iHil Jfr*.. m